- School of Education, Faculty of Science, Health, Education and Engineering, University of the Sunshine Coast, Maroochydore, QLD, Australia

Assessment exemplars are a tool to guide students to what is valued by assessors in a specific assessment task, in short, as examples which illustrate, typically, dimensions of quality. Often high-quality exemplars are provided in formative assessment contexts to develop self-regulated learning. We were interested in researching the perceived efficacy and impact of a variety of assessment exemplars, ranging from low to high quality, in teacher education courses at a regional university. More specifically, this research explores student perceptions of how assessment exemplars support the development of phases and signposts for self-regulated learning. We surveyed 72 students and found that students accessed exemplars regularly and found them useful in providing detailed guidance that went beyond the descriptions of assessment tasks found in course outlines and assessment rubrics. They valued various types of exemplars, a range of quality, and the inclusion of annotated and unannotated versions of exemplars. We identified four key themes from the analysis: assessment exemplars as guides, supplements, starting points, and standards for comparison. Our results support the provision of exemplars as a tool to build student self-regulation in three phases and their contribution to the four signposts on the path from social to independent self-regulatory practice (Zimmerman and Kitsantas, 2014).

Introduction

Assessment exemplars are used in a variety of educational contexts (e.g., law, nursing, education) as a formative tool to guide students to what is valued by assessors in a specific assessment task, in short, as examples that illustrate, typically, dimensions of quality. Exemplars are used by students and teachers to develop student self-monitoring and/or self-regulation, to build student self-efficacy and to encourage ownership over learning (Hawe et al., 2017). The aim of the development of these self-regulatory practices is to improve academic performance. Research across several decades suggests a strong link between self-regulated learning and academic achievement (Panadero, 2017). Exemplars can be used as means of experiential learning in which the participants experience exemplars as learners, gaining understanding of the benefits and pitfalls and consequently applying this knowledge in future contexts upon graduation (Dixon and Hawe, 2016). In the context of teacher education, developing, and experiencing the impact of self-regulatory practices on learning provides an important contribution to both preservice and in-service teachers' developing professional practice (Panadero, 2017).

The word exemplar is defined as “key examples chosen so as to be typical of designated levels of quality or competence” (Sadler, 1987, p. 200). Carless and Chan (2017, p. 1) define exemplars “as carefully chosen samples of student work which are used to illustrate dimensions of quality and clarify assessment expectations.” Newlyn (2013) describes them as examples of best or worst practice designed to promote student understanding of particular skills, content, or knowledge in addition to their use in articulating criteria and standards for assessment tasks. In some cases, these exemplars are provided from a pool of assessment work that has been produced by a previous cohort of students. Typically, these are high quality examples of student work. It is also the case, although less commonly practiced, that assessment exemplars illustrating poor quality can also be provided as guides to students.

Sadler (2002) noted that exemplars convey messages about quality or lack of quality that no other mechanism can provide. They act as a performance benchmark for students by which their own performance can be evaluated and honed. Exemplars offer an “embodiment of standards” (Sadler, 2005, p. 190). Similarly, Bell et al. (2013) defined exemplars as “illustrations of assessment standards in practice” (p. 771). Hence, they also serve not only to improve student outcomes on a task, but they also act as a self-evaluation tool that encourages students to make their own informed judgments (Carless, 2015) about the nature of quality. Similarly, Scoles et al. (2013), Hawe et al. (2017), and Carter et al. (2018) refer to the self-regulatory nature of exemplars as a “feedforward” mechanism supporting students when writing academically. These researchers also noted the impact of exemplars on motivation, self-efficacy, and self-monitoring, in addition to their positive impact on understanding task requirements and the structure of academic tasks, support, and advancement of subject knowledge.

To improve student outcomes in assessment tasks, assessors also commonly provide written feedback in the form of annotations on student work. This feedback mechanism has been discussed in the assessment literature at length, a major finding being that student feedback is not well-understood by students, or ignored, and a constant source of frustration for both assessor and student alike (Grainger, 2015). Exemplars provide a clarity (Price et al., 2012) that rubrics are often criticized for not providing, due to fuzziness, or vagueness. In this regard, researchers (Handley and Williams, 2011; Hendry, 2013) report that the use of exemplars complements traditional written feedback mechanisms as students are able to decode the written feedback as a result of their engagement with the exemplars. Recently, To and Liu (2017) researched the impact of peer and teacher-student exemplar dialogues to unpack assessment standards.

The positive use of exemplars is tempered by the possibility that students may feel that the exemplar provided is the only way to a good result, and hence may in fact restrict creativity, and may result in plagiarism (Newlyn, 2013; Thomson, 2013). Some research into exemplars suggests that students might look at the exemplars alone, without linking them to criteria and descriptors, use them as templates, or plagiarize them (Bell et al., 2013). In their study, Bell, Mladenovic and Price reported 11 students who found the resources, particularly the annotated exemplars, to be too detailed and prescriptive.

Against this background, we were interested in exploring the value of assessment exemplars at the tertiary level and from a student perspective. We were interested in knowing if exemplars provided online would be accessed by students, how often they were used, in what manner they were used and if students valued a range of exemplars reflecting various standards of quality. In addition, we were interested to know how students perceived the provision of exemplars that exemplified a FAIL standard and how these were valued in comparison to those that exemplified PASS to HIGH DISTINCTION standards. Additionally, we were interested in student perceptions of the value of exemplars as compared to the value of explicit criteria used in rubrics and whether the exemplars we provided supported the assessment task rubrics. Hence, the research questions were:

• Do students value exemplars?

• How often are they accessed by students?

• How do assessment exemplars assist students in determining quality?

• What kind of exemplars assist? (i.e., annotated exemplars or un-annotated exemplars)

• Do exemplars from all achievement standards support student learning?

Literature Review

As early as 1987, Sadler advocated the use of exemplars to illuminate what he calls “fuzzy standards” (p. 202), and more recently he noted that “[t]he number of exemplars can probably be made fairly small provided they are accompanied by explicit annotations of the properties of individual pieces” (Sadler, 2009, p. 207). Despite this early identification, it is in recent times that the research into the use of exemplars has gained some momentum and largely as a result of the failure of traditional models of feedback in improving student grades (Price et al., 2011). According to Hendry (2013) one-way after-task feedback is not effective. In a similar vein, Scoles et al. (2013) and Wimshurst and Manning (2013) proposed the feedback emphasis be moved to “feedforward” through the provision of exemplars when introducing tasks. This proposal was supported by their quantitative findings which found students who accessed exemplars scored better than those who did not.

Despite this shift toward the use of exemplars, a search of the assessment literature failed to reveal a single study that dealt with the use of online assessment exemplars at the tertiary level in preservice teacher education courses. Hence, we conclude that there is a gap in the assessment literature that is addressed by our current study and the need to address this gap is echoed by Bell et al. (2013, p. 771) who noted “Little is known about how students use these resources although they are regarded as positive.”

Specific to our context of providing online exemplars at tertiary level, we note the work of Handley and Williams (2011) who reported that in a cohort of 400 students most students were receptive to online annotated exemplars which they found to be very useful in terms of providing guidance on structure and layout and clarifying expectations. In fact, some found it motivating, in that they reportedly wanted to match or beat the quality standard. Some students wanted examples of poor assignments, a result which is also investigated as a focus of our study.

Although some studies (Rust et al., 2003) have reported improved student outcomes as a result of using exemplars, other studies (Carter et al., 2018) have found the benefits of exemplars were not reflected in improved student performance, despite their perceived efficacy by students. Other studies (Newlyn et al., 2012) found no significant impact, positive or negative over a 4-year period. We also note, specific to our context, the study by Hendry et al. (2011) on the use of a variety of exemplars in a first-year law course, reflecting different standards (poor, borderline, and excellent). They reported the usefulness of the templates to students in providing direction and ideas, and to assessors to explain standards through exemplars. In their study, they found evidence that when students engage in the task of marking exemplars, accompanied by teacher explanations of the grades awarded to the exemplars, students develop a better understanding of quality and hence assessor expectations (Hendry et al., 2011). This finding was replicated in further studies by Hendry and Anderson (2012) and Hendry and Jukic (2014) which also reported that students valued interactive assessor explanations for grades given to exemplars.

Similarly, Kean (2012) identified peer assessment, not just interaction and marking by an instructor, alongside the provision of exemplars, as a formative strategy for developing student understanding of quality. Formative assessment is a strategy that can be used to empower students as self-regulated learners (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006) reducing a dependency that positions students as passive subjects (Boud, 2007). Panadero et al. (2018, p. 13) suggest that “self-regulated learning should be the primary goal of formative assessment.” Exemplars are not standards but are indicative of standards and when accompanied by marking guides and dialogue and/or student marking of exemplars, they can have a significant impact on learning as students learn to interpret and apply standards to recognize “quality.” In this regard, the literature on self-regulation is lengthy. For example, Perry and Smart (2007) define it as “…an active constructive process whereby learners set goals for their learning and monitor, regulate, and control their cognition, motivation, and behavior, guided, and constrained by their goals and the contextual features of the environment” (p. 64). While most research is focused on the development of specific interventions that support learning in the three common phases evident in self-regulated learning models (preparation, performing, and reflection), it is acknowledged that little research focusses on assessment specifically (Panadero et al., 2018).

In this study we draw upon the socio cognitive work of Zimmerman (2000, 2002) and Zimmerman and Kitsantas (2014). They suggest a three-phase theoretical model of self-regulation, which refers to “self-generated thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that are oriented to attaining goals” (p. 65). The three phases include a forethought phase (processes and beliefs that occur before efforts to learn), a performance phase (processes that occur during implementation), and a self-reflection phase (processes that occur after each learning effort). Zimmerman and Kitsantas (2014) suggest that there are four signposts that support the move toward that attainment of self-regulatory competence. The first sign post is at an observation level where learners explore model performances to support their understanding of the skill or task. The second signpost is emulation where the learner uses the model response to generate their own version of the task. At the third self-controlled signpost the learners apply the ideas to writing beyond the scope of the examples provided, and at the final signpost the self-regulated level allows the learner to practice and make adaptations based on their own experiences.

Assessment exemplars provide opportunities for students and teachers to explore assessment task requirements. Most recently, To and Carless (2015) and To and Liu (2017) reported on studies that focussed on the “dialogic use of exemplars” which they described as student participation in discussion to maximize the potential of analyzing exemplars. They also noted the importance for the teacher that “teacher guidance serves to explicate the characteristics of good quality work and to increase students' critical awareness of the differences between exemplars and their own writing” (p. 1). Similarly, Carless and Chan (2017) investigated the role of dialogue in supporting students to develop their appreciation of quality work through the use of exemplars. The purpose of this work is to further explore the contribution of assessment exemplars in the context of self-regulation.

To summarize, the research into the efficacy of exemplars tells us that students appreciate the provision of exemplars because exemplars reveal tacit knowledge (To and Carless, 2015) and illustrate assessor perceptions about what is valued in student work. Exemplars can complement traditional written feedback processes; they can be annotated; and provide a stimulus for dialogue and discussion. In addition, they support the transmission of tacit knowledge pertinent to a discipline and they assist in transmitting knowledge of criteria and standards (Newlyn and Spencer, 2009). This paper explores student perceptions of how assessment exemplars support the development of phases and signposts for self-regulated learning.

Methods

In this exploratory study we targeted courses at undergraduate and postgraduate level in teacher education programs (undergraduate Bachelor of Education; postgraduate Diploma of Education, postgraduate Master of Education) at a regional university. In total we targeted six courses, with total enrolments of ~300 students. We used the Learning Management System, BlackBoard to upload a variety of assessment exemplars representing a variety of standards of student work from previous iterations of these courses. The exemplars ranged from FAIL to HIGH DISTINCTION. The exemplars were all written essays ranging in length from 2000 to 5000 words. The exemplars were loaded prior to the commencement of the course. We “enabled statistics” on the BlackBoard sites in order to access usage information. To enable us to answer the research questions, we implemented a student survey consisting of Likert scale and open response questions. Participation was voluntary. Seventy-one percent of students were undergraduate students; 26% were Graduate Diploma students and the remaining 3% were from Master of Education courses.

Data were collected over the course of one semester. Ethical consent was received from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the university in which this study was conducted (protocol number A/16/789) and the consent of the participants was obtained by virtue of survey completion after potential participants were provided with all relevant information. After the data were collected, we undertook a process of first-cycle descriptive coding and second-cycle pattern coding in accordance with Miles et al. (2014). Two researchers independently coded the participants' responses to the questions in a cross-case analysis to identify themes, similarities, and differences (Creswell, 2007), and then cross-checked for consistency in theme identification before constructing a descriptive narrative to present, analyze, and discuss the findings.

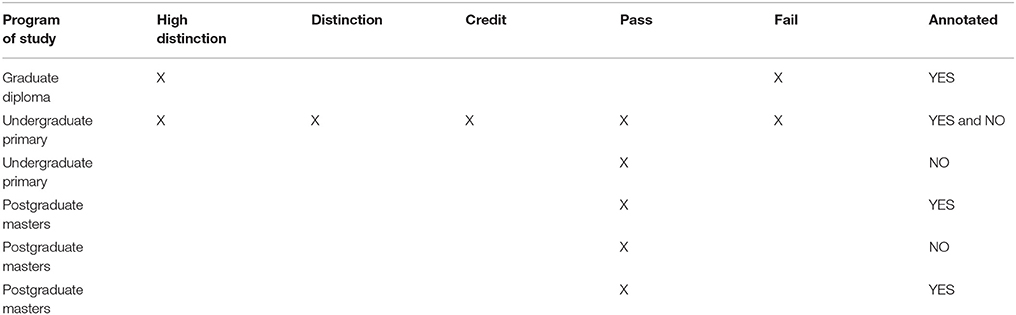

In total we received 72 responses to the survey. As this study was explorative, we focused our study broadly across the teacher education cohort within our education courses, collecting exemplars varying in quality, and with or without annotations (Table 1). Our sampling strategy was therefore convenience sampling, rather than purposive sampling (Rapley, 2014).

We wanted to evaluate the efficacy of a range of exemplars, annotated and unannotated. Our annotations were not annotations in relation to the genre of writing but rather, were explicitly connected to the criteria and standards in the rubric that were used to make judgments about the quality of student work. The mark ups we provided in the form of annotations, identified instances where the evidence (i.e., the student work) exemplified the criteria and standards. If all exemplars were to be annotated, then there would be no way of evaluating if students valued exemplars that were not annotated. Conversely, if all exemplars were to be unannotated, we would not be able to evaluate directly if students also valued annotated exemplars. We would have to be relying on their comments and there would be no way of ensuring their comments. In some courses we provided the full range of exemplars covering all the standards, but in others we provided single exemplars. In the Masters courses the exemplars were discussed with a tutor and the grades allocated scrutinized against the criteria sheets (also referred to as rubrics) to determine the alignment. In the undergraduate courses and the Graduate Diploma courses, the exemplars were not discussed in any way. We had anticipated a larger number of responses but the small number we received (n = 72) meant that we did not have the statistical power to find significance, so our analyses described below, were limited to a narrative based on descriptive statistics. We used a tool known as page skip logic to enable students to progress to relevant sections of the survey, depending upon their context.

Descriptive Statistics

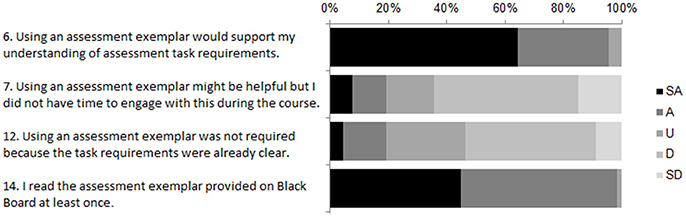

Our first research question was to what degree students valued exemplars; this question was measured by many of the Likert scale questions and a further indication of value was observed through the Blackboard statistics log of frequency with which students accessed the exemplars provided to them. For example, 95% of students surveyed supported our assumption that students would value exemplars due to the support that they would provide students to understand the assessment requirements (Q6). This was confirmed by the statistic that 100% of surveyed students accessed the exemplars provided (Q13) despite 20% of the surveyed students acknowledging the fact that this was not required due to the explicitness of the task requirements (Q12). Surprisingly, one in five students admitted that they did not have time to access the exemplars (Q7) despite the perceived value of doing so. Ninety eight percent of students accessed the exemplars at least once (Q14); 77% accessed the exemplars between two and four times; 17% between five and 10 times and 6% more than 11 times (Q15). The results pertaining to students' perceived value of exemplars are summarized in Figure 1. The abbreviations to the right of each table refer to the Likert Scale. SA equates to Strongly Agree; A equates to Agree; U means Unsure; D means Disagree; and SD means Strongly Disagree.

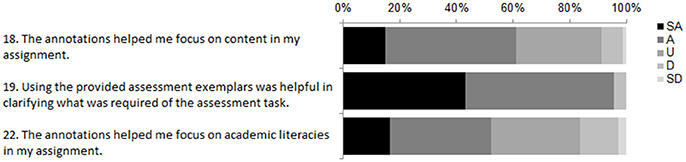

We were especially interested in what kind of explicit support the exemplars provided to students (Figure 2). Ninety-five percent indicated that the exemplars clarified expectations (Q19); 63% of students valued the support in terms of content (Q18); and 54% valued the support in terms of understanding academic literacies (Q22).

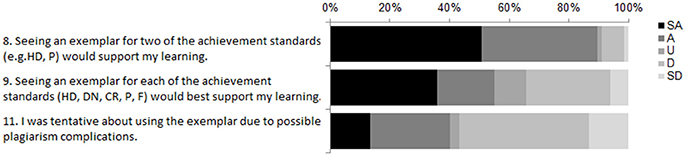

In addition, we were interested to know how many and what kinds of exemplars were most valued by students (Figure 3), that is, would students value the utility of HIGH DISTINCTION exemplars as well as FAIL exemplars. In this regard, 88% of students surveyed (Q8) valued the provision of just two exemplars at both ends of the quality continuum (HIGH DISTINCTION and PASS) but just over half of the students (55%) wanted to see an exemplar for every standard (Q9). As we suspected, based on previous literature that we accessed, 43% of students were tentative about using exemplars due to possible plagiarism complications (Q11).

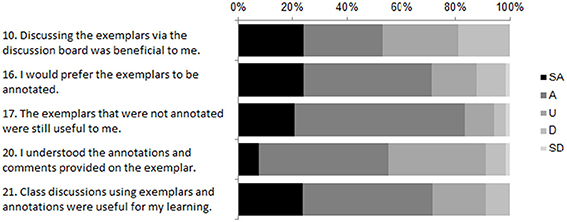

We wanted to know if students wanted in-class discussions of the exemplars—clean, un-annotated copies of exemplars, or annotated exemplars—and how these supported their understanding of the assessment task. To determine students' attitudes regarding the utility of unpacking the exemplars via “discussion,” we provided two questions: (Q21) 72% valued the in class discussions of the exemplars provided, and (Q10) 33% valued these discussions via an online discussion board. Annotated or not, students found the exemplars useful, evidenced by their responses to Q16 (70%) and Q17 (82%) despite the fact that only 58% understood the annotations and comments provided on the exemplar (Q20). These responses are identified in Figure 4.

Finally, some questions (Q7, Q9, Q10, Q12, Q16, Q18, Q20, Q21, Q22) triggered “unsure” responses, identified by us, the researchers, as being at least 10% of the responses, particularly for those questions that involved the use of annotations.

Thematic Analysis

To validate and verify the quantitative responses reported above we also included in our survey an open response section, consisting of three questions.

Q24: What specifically was beneficial about having exemplars?

Q25: Do you think you will get a better grade as a result of having exemplars provided for you?

Q26: Please provide one example of how the exemplar improved your assessment task? Why exactly?

Students valued the exemplars because they provided a clarification of the standards expected by the assessor, both specifically and also as a general guide. The exemplars provided not just a starting point but an end point, a target or even a benchmark to be met, and a way to compare their own scripts with various standards. They were valued not just in their own right, but also as a complement to the marking guides, and criteria sheets provided. More specifically, the exemplars provided a clear expectation of desired structures, sequences, and layout, which were not necessarily included in the task guidelines, due to the limitations of space. In particular, the exemplars provided tangible examples of the expectations of academic literacies, including referencing. The final theme that emerged was unexpected in terms of devaluing the FAIL exemplar as unhelpful, demotivating and even distracting. We believed that this exemplar would be valued by students, but this was not the case. Hence, four key themes form the findings from the analysis: assessment exemplars as guides, supplements, starting points, and standards for comparison.

Our first theme identified the exemplars as useful to students because they provided a guide, both generally and explicitly. One student referred to the distinction level exemplar as a “bible” that would be followed to achieve this particular standard. While others remarked on the usefulness of the exemplar in providing “clear directions as to what the task expectations were” in particular in regard to “each of the standards” illustrating the difference between a pass and a high distinction standard for example. The exemplars also provided specific guidance in terms of layout, content, language to be used, format and structure of the assignment. One student said “The exemplars gave me guidance as to the structural layout of the assignment. I found it very useful to see how the breakdown of paragraphs and sections could be used to add emphasis.” Another commented “Exemplars allowed me to see the way the assessment was set out and being able to see the structure of the writing.”

Our second theme is related to the usefulness of exemplars as “valued supplements to the criteria sheet and task guidelines”. Students commented that criteria sheets/rubrics “were not always clear” and were “quite subjective,” even “confusing.” Exemplars provided a “clarity” that the rubric and the task description alone could not achieve. One student commented “You get an opportunity to see mistakes or what could have been improved to get a higher mark that is not explicit in the criteria, and then adjust your assessment piece accordingly.”

Expectations of academic literacies and referencing requirements were a major theme, typified by comments such as “It made the expected writing quality clear” and it provided “clarity on the topic and on academic literacy.” We were surprised by the fine-grained nature of the engagement of some students, characterized by the following comments: “It assists in understanding of structure, grammar, punctuation.” And “It was helpful to have a reference list.”

Theme three referred to the usefulness of exemplars as a starting point for the students and in one case, even a motivating factor. “They give an initial spark or direction for me. After that I make the assignment my own.” Students also suggested that in the context of their busy workload across a variety of tasks and courses the exemplars provided a way into the task because “Sometimes starting is the hardest.” Getting students to begin the process of thinking about their work is an important way to engage the learner, indicated by comments such as the examples “help me start thinking about the task, see how it can come together.”

Theme four identifies exemplars as being useful in terms of how they exemplified a certain standard of work, or a “source of comparison with their own work” and also with the rubric used to assess the task. In short, after the assignment had been done, students accessed the exemplars to “evaluate their own direction,” perform a “final checklist,” a “benchmark” exercise, which was then used to hone their own work. Connected to this final theme of comparison was the student suggestion that providing a FAIL exemplar was not useful. Typically, students found these “not useful,” because they “did not assist learning,” were “demotivating and distracting.”

Discussion

This study fills a gap in the literature about the perceived efficacy of using online assessment exemplars which according to Handley and Williams (2011), is relatively modest. Our literature review revealed a dearth of literature that discussed the provision of online assessment exemplars at the tertiary level in teacher education courses. It also suggests the importance of teachers engaging in and experiencing self-regulatory learning so that they can develop their own professional practice (Panadero, 2017). Hence, this discussion will explore the contribution of assessment exemplars to Zimmerman's (2002) three phases of self-regulation and the contribution to the four signposts on the path from social to independent self-regulatory practice (Zimmerman and Kitsantas, 2014).

At the forethought phase of self-regulation (Zimmerman, 2002), the assessment exemplars provided students with information that support them in their analysis of the task. Our study reflected the existing literature that students do value exemplars and access them often. The themes of exemplars as guides, supplements and starting points connect with the notion of both task analysis and motivation to get started. In this context the assessment exemplars provided the opportunity to achieve the first signpost in the self-regulation journey, an opportunity to observe an example of the task requirements. However, it must be noted that the provision of the FAIL standard was identified by students as counter-productive and not motivating, a perception not reported before in the literature and contrary to what Handley and Williams (2011) reported as being desired by students. It suggests that students draw upon the exemplar to examine and observe what to do for the purpose of moving toward the stage of emulating the task in accordance with the self-regulatory signposts of Zimmerman and Kitsantas (2014). This suggests that the students are operating with the use of exemplars at the first and second stages, both of which requires social interaction and discussion with their teachers and lecturers to further develop as self-directed learners. Our study supports very strongly, the value of dialogic use of exemplars, in other words, discussions among students and assessors about the standards exemplified in the exemplars. This supports the focus by Hendry et al. (2011), Hendry and Anderson (2012), Hendry and Jukic (2014), and Hendry (2013) who also reported the high value placed on interactive assessor explanations by students.

During the performance phase and the self-reflection phase of self-regulation (Zimmerman, 2002), as students began the work of developing their task, the exemplars provided a standard for comparison. Our study supports previous work by Sadler (2005) in that exemplars provide a benchmark and represent an embodiment of standards or illustrations of standards in practice (Bell et al., 2013). Similarly, our study supports the results by Price et al. (2012) that assessment exemplars provide a clarity that rubrics cannot provide. Hence our study, regardless of the course being studied, reinforces these previous findings. In this regard we note the increasing necessity to provide exemplars for students as support for rubrics that have been typically criticized by students as being unclear and fuzzy. However, despite existing literature (Sadler, 2009) that suggests annotated exemplars are preferred, many of our students reported a perceived efficacy with or without annotations. This suggests that students are moving toward the third (self- control) and fourth (self-regulation) signposts of Zimmerman's and Kitsantas' (2014) capability to self-regulate.

While our study reflected the existing literature that students do value exemplars and access them often, at the same time we report conflicting evidence that despite the perceived value and the fact that 100% of students accessed the exemplars, 20% of the students could not find time to engage with them and 20% did not find them useful. The 20% response of not having time to use the exemplars aligns with the type of degree being studied by many of these teacher education students, the Graduate Diploma of Education course, which is an intensive two-semester course, as opposed to the undergraduate students, who study for 4 years or eight semesters. Hence, we conclude that the intensive nature of the course being studied is a variable that impacts upon the engagement of students with exemplars, a finding we had not seen in previous literature.

In addition to the intensive nature of the course as a reason why 20% of students did not engage with the exemplars, we interpret this result as a direct consequence of the development of autonomy and self-direction that increases with student experience of academia. In short, we conclude that postgraduate Masters degree students do not need as much support as undergraduate students and hence, exemplars become devalued as students gain regulatory and self-monitoring skills as they progress from undergraduate to postgraduate academic studies. In this regard, we found no existing literature that described this trend other than those studies, described earlier, that reported the usefulness of exemplars as being related to the development of regulatory skills.

While the remaining 20% who did not find the exemplars useful may well be students who are already operating in a self-directed manner and do not have the need to engage with these examples to define the task for them, another possibility is concern about breeching academic integrity. Academic integrity is a concern for many students due to a fear of plagiarism as a direct result of using exemplars as templates to copy (Thomson, 2013; To and Carless, 2015) and hence, this may be a deterrent to more widespread take-up of exemplars to assist student understanding of assessment tasks. To avoid the fear of plagiarism, a future research focus might analyse the impact of exemplars on student results after discussion of the alternative of using exemplars on a different question or topic to the one set for students in their current assignment. This could be coupled with a direct focus on the use of text-matching software in order to convince students that the potential use of exemplars resulting in plagiarism can be overcome and the potential benefits outweigh the risks.

Conclusions

Our results support the development of self-regulated learning in students as a result of direct engagement with exemplars. In our study, students' qualitative comments indicated that students were self-assessing their own work, thereby taking ownership, actively monitoring and regulating their products by managing different processes as they engaged with the exemplars (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006). They were setting goals using the exemplars as benchmarks or targets; they were devising strategies to ensure they avoided plagiarism; they were managing resources (i.e., the various exemplars provided) by determining what exactly they were choosing to focus on, whether it was a FAILED exemplar or a quality exemplar or academic literacies. This is in alignment with Zimmerman's three phases and signposts toward self-regulation (Zimmerman, 2002; Zimmerman and Kitsantas, 2014). It also reflects the work of Perry and Smart (2007) who define the construct of self-regulation as the degree to which students can regulate aspects of their thinking, motivation and behavior during learning.

An additional future research focus is to explore the ways in which assessment exemplars can support rubrics and how rubrics can support assessment exemplars and especially the differences in the perceived value of each of these assessment artifacts. There is a danger that one artifact may not support the other and this may lead to different messages regarding the expectations of the assessment task.

Finally, in conclusion, we suggest that research into the provision of assessment exemplars, using greater numbers of students across different courses and contexts, will provide added clarity to the results of the study reported here. In particular, we suggest future research focuses on those issues around the use of annotations, the efficacy of discussing exemplars through dialogue, the fear of plagiarism, and the large numbers of students who are still unsure about the usefulness of exemplars in improving their understanding of assessment requirements. Regarding this, we suggest further research into the provision of exemplars in the online mode, either as a support for student-teacher conversations or as stand-alone artifacts.

We suggest that future work analyses the growing independence of students as they progress from academic year to academic year to determine if assessment exemplars are most useful in the early part of a student's academic career and if reliance on exemplars decreases over time. In addition, future focuses may want to analyse how perceived efficacy changes over time in direct proportion to the time spent in academia. Our study suggests that this may indeed be the case. As our study was exploratory, future studies could employ an experimental design consisting of three test group conditions provided with varying methods of exemplar input: with/without teacher discussion; with/without annotation; with/without fail exemplars and a control group which receives only a rubric and explanation of the assessment task. This would facilitate answers to a key question: do students who have access to a pass and high-quality exemplars with or without classroom/teacher discussion perform better than students who do not.

Author Contributions

PG implemented the survey and completed the first drafts. DH assisted in the writing of the drafts and referencing. MC analyzed and interpreted the quantitative data.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Bell, A., Mladenovic, R., and Price, M. (2013). Students' perceptions of the usefulness of marking guides, grade descriptors and annotated exemplars. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 38, 769–788. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.714738

Boud, D. (2007). “Reframing assessment as if learning were important,” in Rethinking Assessment in Higher Education, eds D. Boud and N. Falchikov (Abingdon: Routledge), 14–26. doi: 10.4324/9780203964309

Carless, D. (2015). Analysing Exemplars to Support Students' Understandings of Assessment. CRADLE seminar, Melbourne, VIC.

Carless, D., and Chan, K. K. H. (2017). Managing dialogic use of exemplars. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 42, 930–941. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2016.1211246

Carter, R., Salamonson, Y., Ramjan, L., and Halcomb, E. (2018). Students use of exemplars to support academic writing in higher education: an integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 65, 87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.02.038

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative Enquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. London: SAGE Publications.

Dixon, H., and Hawe, E. (2016). Utilizing an experiential approach to teacher learning about AfL: a consciousness raising opportunity. Austr. J. Teach. Educ. 41:1. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2016v41n11.1

Grainger, P. (2015). How do pre- service teacher education students respond to assessment feedback? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1096322

Handley, K., and Williams, L. (2011). From Copying to Learning: using exemplars to engage students with assessment criteria and feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 36, 95–108. doi: 10.1080/02602930903201669

Hawe, E., Lightfoot, U., and Dixon, H. (2017). First-year students working with exemplars: promoting self-efficacy, self-monitoring and self-regulation. J. Further High. Educ. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2017.1349894. [Epub ahead of print].

Hendry, G., Bromberger, N., and Armstrong, S. (2011). Constructive guidance and feedback for learning: the usefulness of exemplars, marking sheets and different types of feedback in a first-year law subject. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 36, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/02602930903128904

Hendry, G. D. (2013). “Integrating feedback with classroom teaching: using exemplars to scaffold learning,” in Reconceptualising Feedback in Higher Education: Developing Dialogue with Students, eds M. Merry, D. P. Carless, and M. Taras (Abingdon: Routledge), 133–141.

Hendry, G. D., and Anderson, J. (2012). Helping students understand the standards of work expected in an essay: using exemplars in mathematics pre-service education classes. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 38, 754–768. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.703998

Hendry, G. D., and Jukic, K. (2014). Learning about the quality of work that teachers expect: students' perceptions of exemplar marking versus teacher explanation. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. Available online at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol11/iss2/5

Kean, J. (2012). Show AND tell: Using peer assessment and exemplars to help students understand quality in assessment. Pract. Res. High. Educ. 6, 83–94. Available online at: https://ojs.cumbria.ac.uk/index.php/prhe/article/view/126

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Salda-a, J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd Edn. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Newlyn, D. (2013). Providing exemplars in the learning environment: the case for and against. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 1, 26–32. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2013.010104

Newlyn, D., Juriansz, J., and Spencer L. (2012). Using exemplars to improve student performance in a contracts law research essay. Int. J. Learn. High. Educ. 19, 83–94.

Newlyn, D., and Spencer, L. (2009). Using exemplars in an interdisciplinary law unit: listening to the students' voices. J. Aust. Law Teach. Assoc. 2, 121–133. Available online at: file://usc.internal/usc/home/pgrainge/Downloads/2-2-59-749.pdf

Nicol, D., and Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and selfregulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Stud. High. Educ. 31, 199–218. doi: 10.1080/03075070600572090

Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: six models and four directions for research. Front. Psychol. 8:422. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00422

Panadero, E., Andrade, H., and Brookhart, S. (2018). Fusing self-regulated learning and formative assessment: a roadmap of where we are, how we got here, and where we are going. Aust. Educ. Res. 45, 13–31. doi: 10.1007/s13384-018-0258-y

Perry, R. P., and Smart, J. C. (eds.). (2007). The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: An Evidence-Based Perspective. Springer.

Price, M., Handley, K., Miller, J., and O'Donovan, B. (2011). Feedback: all that effort, but what is the effect? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 35, 277–289. doi: 10.1080/02602930903541007

Price, M., Rust, C., O'Donovan, B., Handley, K., and Bryant, R. (2012). Assessment Literacy: The Foundation for Improving Student Learning. Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development.

Rapley, T. (2014). “Sampling strategies in qualitative research,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, ed U. Flick (London: SAGE Publications Ltd.), 49–63.

Rust, C., Price, M., and O'Donovan, B. (2003). Improving students' learning by developing their understanding of assessment criteria and processes. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 28, 147–164. doi: 10.1080/02602930301671

Sadler, D. R. (1987). Specifying and promulgating achievement standards. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 13, 191–209. doi: 10.1080/0305498870130207

Sadler, D. R. (2002). “Ah!…So That's Quality,” in Assessment Case Studies, Experience and Practice from Higher Education, eds P. Schwartz and G. Webb (London: Kogan Page), 130–136.

Sadler, D. R. (2005). Interpretations of criteria-based assessment and grading in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 30, 175–194. doi: 10.1080/0260293042000264262

Sadler, D. R. (2009). Grade integrity and the representation of academic achievement. Stud. High. Educ. 34, 807–826. doi: 10.1080/03075070802706553

Scoles, J., Huxham, M., and McArthur, J. (2013). No longer exempt from good practice: using exemplars to close the feedback gap for exams. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 38, 631–645. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.674485

Thomson, R. (2013). Implementation of criteria and standards-based assessment: an analysis of first-year learning guides. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 32, 272–286. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2012.676026

To, J., and Carless, D. (2015). Making productive use of exemplars: peer discussion and teacher guidance for positive transfer of strategies. J. Further High. Educ. 40, 746–764. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2015.1014317

To, J., and Liu, Y. (2017). Using peer and teacher-student exemplar dialogues to unpack assessment standards: challenges and possibilities. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 43, 449–460. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2017.1356907

Wimshurst, K., and Manning, M. (2013). Feed-forward assessment, exemplars and peer-marking: evidence of efficacy. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 38, 451–465. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2011.646236

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). “Attainment of self-regulation: a social cognitive perspective,” in Handbook of Self-regulation, eds M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, and M. Zeidner (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 13–39.

Keywords: assessment, exemplars, pre- service education teachers, efficacy, feedforward

Citation: Grainger PR, Heck D and Carey MD (2018) Are Assessment Exemplars Perceived to Support Self-Regulated Learning in Teacher Education? Front. Educ. 3:60. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00060

Received: 28 March 2018; Accepted: 03 July 2018;

Published: 14 August 2018.

Edited by:

Anders Jönsson, Kristianstad University, SwedenReviewed by:

Graham Hendry, University of Sydney, AustraliaDavid Newlyn, Western Sydney University, Australia

Copyright © 2018 Grainger, Heck and Carey. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peter R. Grainger, cGV0ZXIuZ3JhaW5nZXJAdXNjLmVkdS5hdQ== orcid.org/0000-0001-8214-2595

†Deborah Heck orcid.org/0000-0002-0235-8546

Michael D. Carey orcid.org/0000-0002-3117-9010

Peter R. Grainger

Peter R. Grainger Deborah Heck†

Deborah Heck† Michael D. Carey

Michael D. Carey