95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 30 May 2018

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 3 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00032

This article is part of the Research Topic What Is the Role for Effective Pedagogy In Contemporary Higher Education? View all 13 articles

Studying at university continues to grow in popularity and the modern-day university has expanded considerably to meet this need. Invariably as such expansion occurs pressures arise on a range of quality enhancement processes. This may have serious implications for the continued delivery of high quality learning experiences that both meet the expectations of incoming students and are appropriate to their postgraduation aspirations. Ensuring students become active partners in their learning will encourage them to engage with a range of quality enhancement processes. The aim of the current work is to examine the various factors that motivate students to engage in such a fashion. Three focus groups were carried out in a stratified manner to ascertain student motivations and to triangulate an effective set of recommendations for subsequent practice. The participants consisted of engaged and non-engaged first year undergraduate students as well as student-facing staff who were asked to comment on their experiences as to why students would want to engage as a course representative. Nominal group technique was applied to the emerging thematic data in each group. Three key motivational themes emerged that overlapped across all focus groups i.e., a need for individual representation that makes a change, a desire to develop a professional skillset as well as a desire to gain a better understanding of their course of study. A university that aligns its student experience along these themes is likely to facilitate student representation. As is standard practice recommendations for future work are described alongside a discussion of the limitations.

A considerable body of evidence now exists supporting the range of advantageous outcomes that engaging with Higher Education (HE) has at both the level of state and individual (Bloom et al., 2006; King and Ritchie, 2013; Holmes and Mayhew, 2016). Indeed, a positive relationship has been revealed between HE and a higher level of earnings (Walker and Zhu, 2013), increased employability skills (Mason et al., 2009; Towl and Senior, 2010) as well as engagement in civic behaviors such as voting (Dee, 2004). Graduates are also less likely to engage in criminal activity (Sabates, 2008). In light of these clear benefits it is perhaps unsurprising that the global HE sector remains vibrant with more and more people applying to study at HE than ever before (Altbach et al., 2009 see also Burgess et al., 2018).

The significant benefits associated with successfully graduating from a programme of study in HE has invariably seen a rise in the numbers of people wanting to take part in such learning (Walker and Zhu, 2008). Indeed, across the global HE sector the number of student enrolments have been increasing and show growth from 13.8% in 1990 to 29% in 2010 (Varghese, 2013). To accommodate the increase in student applications institutions have had to change their organizational practice to ensure that they remain appealing to a wider and more diverse pool of applicants (see e.g., Trow, 2000). The rate of such expansion in the HE sector has led some scholars to describe it as “massification” which is a sociological term used to describe the process by which a particular concept is adopted into mainstream culture (Scott, 1995). The significance of this massification philosophy is such that the current global HE sector has changed so much over the last decade that it is almost unrecognizable (Teichler, 1998; Guri-Rosenblit et al., 2007). However the almost constant expansion on key stakeholder roles within HE are invariably starting to reveal some negative effects (Pechar and Park, 2017). As universities grow in size and complexity it is likely that this will place a strain on the quality of the provision (Lomas and Tomlinson, 2000; Lomas, 2002) which may in turn have an adverse effect on the levels of student engagement (Bryson and Hand, 2007). One way to potentially ameliorate such adverse effects is to ensure that the design and delivery of effective pedagogy be informed by the student experience or what has been termed the “student voice” (DeFur and Korinek, 2010).

The potential impact that massification may have on student engagement is not trivial as the drive for an ever-growing HE provision catering for an ever-growing cohort can only successfully occur if students are placed at the very heart of its quality (Hodson and Thomas, 2003). Placing students at the heart of quality processes ensures that the HE sector has both the ability to expand as well as meet the expectations of the students that it serves (Brown and Burdsal, 2012; Senior et al., 2014). By engaging students at the very core of the delivery of their programmes it may also be possible to drive effective learning. Students who feel that they are embedded within the activities of an academic department feel more aligned to their professional identity and subsequently start to develop effective learning strategies that facilitate the emergence of such an identity (Towl and Senior, 2010; Senior and Howard, 2014; Tissington and Senior, 2017 see also Carey, 2013).

From an organizational perspective the need to ensure that effective mechanisms for quality governance are in place has never been more important. Despite the traditionally established balances of rewarding research output more than teaching performance, academic staff are seeing more and more of their time being spent on teaching activities (Young, 2006; Winstone, 2017). This has not only resulted in an increase in teaching staff who may lack the appropriate qualifications, but has also driven a significant increase in dissatisfaction within the professoriate who tend to regard their professional identity as being more aligned to their research activities (Smeby, 2003). Indeed there is an emerging literature focusing on the effects that such shifts in professional identity may have on the detriment of quality throughout HE (Bathmaker, 2003; Beblavý et al., 2015).

However such significant sectoral growth ensures that the development of effective quality governance structures is complex. Today's universities are more akin to the pluralistic complexity of the so-called “multiversity” (Kerr, 2001). An organizational structure that can best be imagined as an entity consisting of a central steering core with many semi-autonomous and interlocking research programmes that in turn inform the delivery of a large-scale teaching portfolio. A casual observer to any of the key HE institutions in the developed world will readily see that Kerr's model for a pluralistic multiversity is very much the dominant design.

In light of the significant organizational complexity that is evident within a contemporary university we have previously argued the need for significant change to the governance structures that will allow for the development of innovation (Knight and Senior, 2017). This new model would see the development of a common steering core consisting of academic members of staff, professional administrators working alongside student-stakeholders. The members of this common steering core would be allowed the opportunity to develop professional skills in management as well have protected time to reflect on how best to innovate effective delivery.

For such governance structure to succeed it would be necessary for all members to be motivated to engage with the various processes. It goes without saying that academic administrators would be the most motivated stakeholder group here and linking reputational advantages to a positive student learning experience could act as an extrinsic motivator for members of academic staff (Meyer and Evans, 2005). However, it is not known what motivations, if any, engender student participation within the full range of quality governance processes (see e.g., Ross et al., 2016). While it could indeed be argued that the opportunity to develop a set of professional skills that would be acquired when contributing to the quality of any academic programme is important, it has yet to be seen whether or not this is a sufficient mechanism for students to fully engage with the governance process.

Addressing the problem of facilitating student engagement is both fundamental to the success of a university and is at the core of a critical pedagogy that seeks to promote effective learning via the process of democratic engagement, mutual dialogue and cooperative working (Shor and Freire, 1987). At the heart of effective critical pedagogy is the importance of students being active partners of their learning rather than simply absorbing the information that they are given (Freire, 2000). To achieve this, students are encouraged to think critically about what they are taught and to challenge these views which in turn will enable them to make subsequent changes to their learning (Cole et al., 2014).

Taking in hand such Frierian logic it is clear that universities should develop effective strategies that facilitate student engagement. But how does an ever-expanding university continue to deliver on its underlying service imperative to provide excellence in teaching while also developing mechanisms to encourage students to be more involved in the management of such excellence? There is no doubt that what might be called “the student voice” is fundamental to effective governance in the modern-day university (Senior et al., 2014). The pertinent question is how do universities develop an effective relationship with students to ensure that they become partners in quality governance and have their voice heard?

That said, there have been some approaches to empower students to participate more often and more readily in the various organizational processes that are part and parcel of a mainstream university. Allowing students to participate fully in the ongoing research activities of academic staff is an effective means to develop a sense of community in the student cohort (Towl and Senior, 2010). This is in line with the Humboldian tradition of HE that sees both student and academic staff members working together for advancement of scientific understanding (Pritchard, 2004). Engaging with ongoing research activity may be one way to develop a sense of a professional community with the student cohort, and this in turn may motivate students to engage further with the on-going governance processes at a university (Tissington and Senior, 2017). However, despite being an effective means to engender the experience of a learning community at the departmental level it is still not known if research activity (or indeed any other kind of potentially relevant activity) is effective in driving sustained student engagement in the wider remit of quality assurance.

There are two main aims to the current research. First, to examine the various motivational factors that may facilitate student engagement. The qualitative nature of the current research will ensure the generation of theory and contribute to an emerging framework that offers a more complete understanding of undergraduate student aspirations. The second is to apply the established qualitative approach of the Nominal Group Technique (NGT; see methods section for a detailed discussion on this technique) to examine student expectations around engagement of the quality provision of their delivery of their programme of study. It is hoped that the application of this technique to examine the psychology of student engagement will lead to the formation of a wider understanding of this crucial, but often overlooked aspect of HE pedagogy.

So as to ensure that the full range of student expectations and attitudes toward engagement were captured the focus groups consisted of (a) students who self-identified as being highly engaged with the role of quality enhancement within their respective courses e.g., an active course representative1, as well as (b) a group of age matched students who self-identified as being non-engaged with the quality enhancement processes and finally (c) a group of student-facing academic staff. Here participants from the academic staff population were recruited via opportunity sampling from a cohort of ~100 members of staff who indicated that they spent more than 70% of their time interacting with students in a support capacity i.e., teaching fellows etc.

In order to ensure that each of the two student-based focus groups consisted of participants who strongly identified as being engaged or non-engaged recruitment was carried out via the institutional student union (SU) organization. The SU manages all aspects of the recruitment and training of local course representatives and as such we could be sure that the two student cohorts were clearly operationalized as consisting of “engaged” and “non-engaged” individuals.

The age of the participants in each of the two student-led focus groups ranged between 18 and 23 years. The three focus groups consisted of mainly female participants apart from one male participant who identified himself as being a highly-engaged student with the quality processes and attended the appropriate focus group (group a). All of the students were enrolled in the first year of a Psychology undergraduate degree programme.

Three focus groups, each lasting approximately an hour were conducted with 5–8 participants. Each of the focus groups were carried out in a medium-sized university in the West Midlands, UK. Prior to engaging with a focus group each participant was informed of their rights to confidentiality and to withdraw at any point. The student participants were also informed that participation (or indeed subsequent withdrawal) would not have any impact in any academic assessments. Participants were also provided with an opportunity to ask any questions prior to the initiation of the protocol.

In this institution there is a relatively low level of student engagement with ~160 of a total 600 (27%) student volunteers being trained to become a course representative within the academic year of 2016/17. This is against a regional average of 558 out of 600 students (93%) being recruited in a comparator institution of equivalent size in the same area2.

All procedures reported here were approved by the local institutional review board and as noted above all participants provided written consent prior to taking part in the focus groups3. The sample size was deemed appropriate for the current study as it was consistent with the critical realist assumptions that underpin this study (Parker, 1992) and with existing work in the field (e.g., Sims-Schouten et al., 2007) as well as studies that have utilized NGT (Lloyd-Jones et al., 1999). Each focus group was carried out in a dedicated room at the same time of day and, to minimize social desirability effects, were led by one of the authors who had not had any contact with any of the participants prior to the data collection and was not identifiable as a member of academic staff by the participants (AS).

Originally developed in 1975, NGT is a structured alternative for facilitating small group discussions in order to achieve a consensus or plan a set of activities (see e.g., Van de Ven and Delbecq, 1974; Claxton et al., 1980; Horton, 1980). It has previously been used to examine a range of HE related questions including examination of the undergraduate student experiences and expectations (O'Neil and Jackson, 1983; Chapple and Murphy, 1996; Williams et al., 2006) and more recently been used to examine effective curriculum design in HE (Abdullah and Islam, 2011; Foth et al., 2016). Indeed, the ease in which NGT protocols can be carried out is likely to be the main factor in driving its uptake within pedagogic research (see e.g., Al-Samarraie and Hurmuzan, 2018).

NGT is also considered to be a more efficient means of analysing focus group data compared to more conventional qualitative techniques (Gallagher et al., 1993; Varga-Atkins et al., 2017). Due to the discursive and democratic nature of the NGT technique participation creates an effective balance between a friendly environment and the group members staying focused on the task at hand (Gallagher et al., 1993). In comparison to other qualitative research techniques such as participant observation or in-depth interviews, NGT diminishes facilitator bias within data collection. Participants occupy an active role within the research, rather than analytic themes or discourses being imposed upon them. It is also extremely time efficient as most sessions are completed within an hour to an hour and a half and the central methodological principle of this technique is that analysis is carried out in a democratically-decided fashion by the focus group participants within the session itself, where most other methods require additional analysis via transcription etc. (Boddy, 2012).

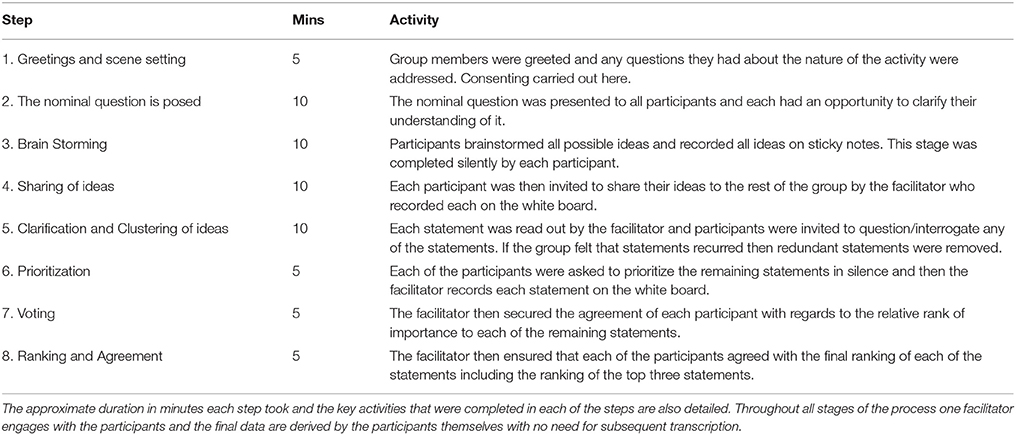

As noted above when compared to the traditional focus group technique, NGT uses a more structured format to allow participants to analyze problems and arrive at solutions in a democratic manner (see Bailey, 2014; Patterson et al., 2017). It also avoids overly directive questions from a facilitator or topic guide that makes a priori assumptions about the importance of specific topics by raising them as questions. To achieve this, participants within each of the focus groups were presented with a single nominal prompt that was written down on a white board in the room, i.e., “What are the driving factors of student engagement in the quality enhancement of programmes?” They were guided through their understanding of a particular prompt in a step-by-step process which began with the participants being given 10 min to write down their ideas in response to the prompt (See Table 1). The facilitator then invited each of the participants to provide the rest of the group with their responses, which were recorded by the facilitator on the white board. This process allows each group member the chance to participate equally and indeed the facilitator plays a crucial role here by ensuring that each group member has an equal opportunity to contribute to the discussion in a “round-robin” fashion. After this stage, the facilitator then initiated the voting stage, which involved asking each participant to rank the importance of each of the responses on the board. At this stage a shortlist of the most appropriate and relevant answers to the prompt are developed on the board. This process is carried out by collating and removing any duplications. Participants were then asked to pick their top five as an individual. These ranking scores (a score of five for the highest ranked, and 1 for the lowest) are then collated by the facilitator while the participants have a short break. These collated scores are then added on to the white board and the pattern of voting discussed. This democratically driven process continued until the list could not be reduced any further and all participants agreed that the responses were ranked in order of importance.

Table 1. Summary of each of the stages of the NGT protocol that were carried out in each of the three focus groups.

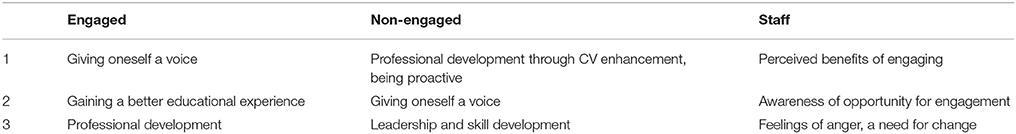

As can be seen from Table 2 below a comparison of the top three themes revealed a partial overlap with some of the themes being revealed by each of the three groups. Consideration of the complete range of themes that were revealed within each of the groups also revealed overlap (see Tables 3–5 below).

Table 2. The top three ranked themes which resulted from the engaged and non-engaged student focus groups as well as the student-facing staff focus group.

The aim of the current study was to examine the range of student motivations that facilitate their engagement with the quality assurance processes of their respective programme of study. To achieve this a qualitative approach using NGT was carried out. As is shown on Table 2 the ranking of the top three themes across each of the three focus groups revealed some overlap with regards to the motivations for engagement. The main drivers for engagement as revealed here can be grouped together as (a) giving oneself a voice, (b) improving learning and then finally (c) professional development. The importance of each of these three themes are each discussed in turn.

Considering the engaged student's, it is perhaps unsurprising that they ranked the opportunity to represent their opinions as the most important factor driving their engagement. Such expression is, after all, the reason for such engagement in the first place. The motivational aspect of this tends to be associated around the development of a clear student identity (McKenna, 2004). For example, in earlier work we found that the psychology of student group formation is such that individuals tend to engage in various social encounters but are unaware they are using these exchanges to reinforce their professional identity (Senior et al., 2012; Senior and Howard, 2014). It may be the case that the act of engagement in various governance committees consolidates their identity at the nexus of academic literacy and professional identity. The finding that the engaged students ranked the opportunity to develop a professional identity higher than the non-engaged students further supports the importance of identity formation in effective learning (See e.g., Senior and Howard, 2014). Additionally, undergraduate students whose professional identities were associated with high academic responsibility are also more likely to express plans to continue their education beyond undergraduate study (Burke and Reitzes, 1981).

The themes that were revealed from the staff focus groups also informed an understanding of the students' desire to develop a representative voice throughout their time at university. Here, the student data were elaborated upon by the staff perspectives. The teaching staff also considered the development of a student voice to be an important driver of engagement. However, they also considered anger as the prime emotion driving such engagement. There has indeed been some work highlighting the need for teachers to be more attuned to their student's emotional state, especially since a positive staff-student relationship leads to an increase in student satisfaction and has a beneficial effect on the retention and performance of students (Thomas, 2002; Rhodes and Nevill, 2004). But there remains a surprising paucity of literature on the effects that negative emotions may have on the student experience. What could be driving the feeling of anger in the modern day student population? (see also Hargreaves, 2000).

As described above there is no doubt that the HE environment has changed considerably over the last 10 years and the modern-day university now places a consumerist ideology at its core (Bok, 2009; Brooks et al., 2016). Within such an ideology, where students are regarded as the key consumer and effective learning the key product, it is legitimate to assume that the measurement of student satisfaction would be straightforward; however this is far from the case (Senior et al., 2017). Yet despite the rapid rise of academic consumerism there remains an issue with regards to the expectations of the students (Riesman, 1980; James, 2002) and in some cases there is a significant disconnection between institutional aspirations and the experiences of the student body (Tomlinson, 2017). In some of these instances students are frustrated with their learning experience as it failed to meet their expectations of a programme of effective study (Nixon et al., 2016). Here the student voice is one of frustration and it is likely that student facing staff (such as the Teaching Fellows who participated in the third focus group) would regularly experience such ire (Finch et al., 2015). It needs to be borne in mind that the nature of the current protocol was such that while student anger was indeed perceived to be a possible intrinsic motivator for student engagement further work needs to confirm the factors that lay behind such anger.

The academic benefits of participation in quality enhancement meetings were rated as the second top ranked theme by the engaged students. While the non-engaged students did not consider the opportunity to develop a better educational experience as important they did rank the ability to develop professional skills in general and leadership skills specifically in the top three themes. The engaged students ranked professional development as number three in the ranks. This spread of ranks and the identification of specific skills by the non-engaged students does show how highly the need to develop a professional skillset is considered by the wider student cohort.

It tends to be common institutional practice to encourage students to engage with the quality management processes by highlighting the benefit to their professional skillset and the current data do show that this is an effective strategy to some extent. The perceived importance of this skillset is also clearly indicated by the top ranked theme from the staff focus group (see Table 5). The data also show the lack of importance that the non-engaged students place on the development of the overall learning experience compared to the professional skill-set. The non-engaged students not only considered a professional skill-set as the most important reason for engaging, but these students also considered the opportunity to develop leadership skills as the third ranked reason for engagement. This particular student group considers the elements of the professional and transferable skillset to be separate entities and judge each of these separate entities as important on its own merits. In light of the fact that the non-engaged students considered the acquisition of such skills to be so important it may be that institutions could see immense dividends returned by clearly framing student engagement as a means to easily acquire such skills.

On considering the rest of the ranked themes that were revealed in the data from the non-engaged students it is clear that the development of a professional skillset is one of the things that they consider to be a positive aspect of engaging with the quality management of their programmes. Indeed, aspects such as the opportunity to develop confidence in oneself, the ability to help others as well as the opportunity to network with others students on the programme are all diagnostic of the need to develop a wide professional and transferable skill set. The depth of detail revealed by the non- engaged students compared to the dearth of detail revealed by the engaged students again highlights the perceived need by the non-engaged students to develop this skillset in their wider learning (Kavanagh and Drennan, 2008). That the students in these groups considered the importance of the development of the professional skill differently is worthy of consideration especially as the development of such a skill-set is starting to be used by institutional managers to encourage students to engage in this manner (Crebert et al., 2004). Highlighting the importance of leadership development as well as the more generic professional skill-set may therefore be beneficial for encouraging engagement in this way.

It is worth noting that both the student groups considered the positive aspects of being actively involved in various management structures and how such involvement would support their ability to enact change e.g., “giving oneself a voice” (Engaged students 18 votes vs. Non enagaged 15 votes). In the staff focus group the importance of this skill did emerge and was reported as “social influence (peers)” but received no votes in the final ranking stage. As the non-engaged students also considered the ‘the opportunity to network with others’ as a possible motivational factor (albeit with four votes) this does show that the wider student body may be motivated by their peers to affect change but do not engage as a means of meeting other students socially. Previous research has suggested the importance of peer relationships in academic performance (Smith and Peterson, 2007) and social ties in an academic context have been shown to positively influence academic performance, generally through motivation as well as the exchange of knowledge and ideas (Smith and Peterson, 2007; Senior and Howard, 2014). It may be the case that the engaged students feel more empowered by their peers to affect a change compared to their non-engaged counterparts.

Worthy of note is the theme of “conscientiousness” that was raised and voted highly by the staff group which shows that staff perceived it to be a more important factor than both the student groups. While previous work does show a strong relationship between a conscientious personality and learning performance the current findings suggest that engaging within quality assurance processes may not (Colquitt and Simmering, 1998). Within the engagers and staff groups, it could be seen that a fair amount of importance was given to the concept of one's own positive attitude as a motivation for engagement. However, it was perceived as significantly less important by the non-engaged group, which perhaps reflects their views on personal responsibility toward motivating oneself to be more engaged.

As can be seen across the various tables above, the majority of themes that secured a rank overlapped across the groups. By carrying out such a triangulatory analysis that involved the three different levels of focus groups it was possible to develop a better understanding of what motivates students to engage with the quality enhancement mechanisms of their specific programme of study. The application of NGT allowed for a detailed analysis of the various expectations to be developed in timely fashion without the need for the interpretation of extensive transcripts. Moreover, as the analysis of the various themes were carried out in a democratic and discursive fashion the members of each of the focus groups could develop ownership of each of the themes which in turn ensured that each of the focus group members were sure of their relevance. The presence of the staff perspective enabled a comprehensive overview of the full range of factors facilitating engagement to be developed.

Despite the unique nature of the current research, the findings should be borne in mind alongside some limitations. Take for example the emerging literature highlighting the role of culture and student engagement (e.g., Zhao et al., 2005). Bearing in mind the fact that the student participants in the current research identified as belonging to two main different cultural groups i.e., white British and east Asian the numbers of participants were too low to enable a cultural comparison to be carried out. Replication of the current paradigm with a larger and more diverse group of participants would therefore be useful. A further limitation to note is that the current research made no inferences to distance learners who may be engaging with their studies online (Chen et al., 2010). The steady increase in online delivery across the global HE sector ensures that more work needs to be carried out examining the means by which this unique student cohort can be engaged.

Future work should also be carried out to ensure a cross-institutional comparison between the expectations of a student cohort in both an institute with a profile of high engagement compared to a profile of low engagement. Work that examines how the motivational aspects of student engagement can be used to drive subsequent student representation should clearly be carried out. While, student engagement in quality processes is clearly a complex and multifaceted issue, use of NGT proved to be an efficient and effective means of unpicking elements of this complexity. The findings presented above provide a firm foundation and serve to inform a fuller understanding of the processes by which students can start to become more engaged in their learning and the quality processes that surround it. This is an important first step toward engaging students fully as partners in their learning.

An earlier version of this article was submitted to PsycArxiv as an open access preprint: doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/H7WUS.

All procedures were approved by the local ethical review board for the Centre for Learning Innovation and Professional Practice at Aston University (10th March 2016).

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

We would like to acknowledge the support of the National Teaching Fellowship to CS.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We would like to thank the final three reviewers whose feedback did indeed contribute to a much stronger final submission. We do appreciate that such efforts can often go unnoticed e.g., https://blog.frontiersin.org/2014/10/05/why-you-should-review-papers-for-frontiers-in-educational-psychology/.

1. ^Engagement as a student course representative is more often than not a voluntary activity so by recruiting these individuals in the present study we can be sure that they strongly identify as being an engaged in supporting learning quality.

2. ^Personal communication 29/06/2017

3. ^Application reference 100316/02

Abdullah, M. M., and Islam, R. (2011). Nominal group technique and its applications in managing quality in higher education. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 5, 81–99.

Al-Samarraie, H., and Hurmuzan, S. (2018). A review of brainstorming techniques in higher education. Think. Skills Creativ. 27, 78–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2017.12.002

Altbach, P. G., Reisberg, L., and Rumbley, L. E. (2009). Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution. Report prepared for the UNESCO 2009 World Conference on Higher Education. Available online at: https://www.kiva.org/cms/trends_in_global_higher_education.pdf (Accessed June 5, 2017).

Bailey, A. M. (2014). The use of nominal group technique to determine additional support needs of Victorian TAFE senior educators and managers. Int. J. Train. Res. 11, 260–266 doi: 10.5172/ijtr.2013.11.3.260

Bathmaker, A. M. (2003). “The expansion of higher education: a consideration of control, funding and quality,” in Education Studies: Essential Issues, eds S. Bartlett and D. Burton (London: Sage), 169–189.

Beblavý, M., Tateryatnikova, M., and Thum, A. E. (2015). Does the growth in higher education mean a decline in the quality of degrees? The role of economic incentives to increase college enrolment rates. CEPS Working Document. Available online at: https://www.ceps.eu/publications/does-growth-higher-education-mean-decline-quality-degrees#

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., and Chan, K. (2006). Higher Education and Economic Development in Africa, Vol. 102. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Boddy, C. (2012). The nominal group technique: an aid to brainstorming ideas in research. Qualit. Market Res. Int. J. 15, 6–18. doi: 10.1108/13522751211191964

Bok, D. (2009). Universities in the Marketplace: The Commercialization of Higher Education. New Jersey, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brooks, R., Byford, K., and Sela, K. (2016). Students' unions, consumerism and the neo-liberal university. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 37, 1211–1228. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2015.1042150

Brown, S. K., and Burdsal, C. A. (2012). An exploration of sense of community and student success using the national survey of student engagement. J. Gen. Educ. 61, 433–460. doi: 10.1353/jge.2012.0039

Bryson, C., and Hand, L. (2007). The role of engagement in inspiring teaching and learning. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 44, 349–362. doi: 10.1080/14703290701602748

Burgess, A., Senior, C., and Moores, E. (2018). A 10-year case study on the changing determinants of university student satisfaction in the UK. PloS ONE 13:e0192976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192976

Burke, P. J., and Reitzes, D. C. (1981). The link between identity and role performance. Soc. Psychol. Q. 44, 83–92. doi: 10.2307/3033704

Carey, P. (2013). Student engagement: stakeholder perspectives on course representation in University Governance. Stud. High. Educ. 38, 1290- 1304. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.621022

Chapple, M., and Murphy, R. (1996). The nominal group technique: extending the evaluation of students' teaching and learning experiences. Asses. Eval. High. Educ. 21, 147–160. doi: 10.1080/0260293960210204

Chen, P. S. D., Lambert, A. D., and Guidry, K. R. (2010). Engaging online learners: the impact of web-based learning technology on college student engagement. Comput. Educ. 54, 1222–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2009.11.008

Claxton, J. D., Ritchie, J. B., and Zaichkowsky, J. (1980). The nominal group technique: its potential for consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 7, 308–313. doi: 10.1086/208818

Cole, M. T., Shelley, D. J., and Swartz, L. B. (2014). Online instruction, e-learning, and student satisfaction: a three year study. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 15, 111–131. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v15i6.1748

Colquitt, J. A., and Simmering, M. J. (1998). Conscientiousness, goal orientation, and motivation to learn during the learning process: a longitudinal study. J. Appl. Psychol. 83, 654–665. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.83.4.654

Crebert, G., Bates, M., Bell, B., Patrick, C. J., and Cragnolini, V. (2004). Developing generic skills at university, during work placement and in employment: graduates' perceptions. High. Edu. Res. Develop. 23, 147–165. doi: 10.1080/0729436042000206636

Dee, T. S. (2004). Are there civic returns to education? J. Public Econ. 88, 1697–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.11.002

DeFur, S. H., and Korinek, L. (2010). Listening to student voices. Clear. House J. Educ. Strateg. Issues Ideas 83, 15–19. doi: 10.1080/00098650903267677

Finch, D., Peacock, M., Lazdowski, D., and Hwang, M. (2015). Managing emotions: a case study exploring the relationship between experiential learning, emotions, and student performance. Int. J. Manage. Educ. 13, 23–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2014.12.001

Foth, T., Efstathiou, N., Vanderspank-Wright, B., Ufholz, L. A., Dütthorn, N., Zimansky, M., et al. (2016). The use of delphi and nominal group technique in nursing education: a review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 60, 112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.04.015

Gallagher, M., Hares, T., Spencer, J., Bradshaw, C., and Webb, I. (1993). The nominal group technique: a research tool for general practice? Fam. Pract. 10, 76–81. doi: 10.1093/fampra/10.1.76

Guri-Rosenblit, S., Šebková, H., and Teichler, U. (2007). Massification and diversity of higher education systems: interplay of complex dimensions. High. Educ. Policy 20, 373–389. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.hep.8300158

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Mixed emotions: teachers' perceptions of their interactions with students. Teach. Teach. Educ. 16, 811–826. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00028-7

Hodson, P., and Thomas, H. (2003). Quality enhancement in higher education: fit for the new millennium or simply year 2000 compliant? High. Educ. 45, 375–387. doi: 10.1023/A:1022665818216

Holmes, C., and Mayhew, K. (2016). The economics of higher education. Oxford Rev. Econ. Policy 32, 475–496. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grw031

Horton, J. N. (1980). Nominal group technique. Anaesthesia 35, 811–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1980.tb03924.x

James, R. (2002). Students' Changing Expectations of Higher Education and the Consequences of Mismatches with Reality. Responding to student expectations. Paris: OECD.

Kavanagh, M. H., and Drennan, L. (2008). What skills and attributes does an accounting graduate need? Evidence from student perceptions and employer expectations. Acc. Finance 48, 279–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-629X.2007.00245.x

King, J., and Ritchie, C. (2013). “The Benefits of Higher Education Participation for Individuals and Society: Key Findings and Reports:‘The Quadrants,’ in Research paper for the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/254101/bis-13-1268-benefits-of-higher-education-participation-the-quadrants.pdf (Accessed June 5, 2017).

Knight, T., and Senior, C. (2017). On the very model of a modern major manager: the importance of academic administrators in support of the new pedagogy. Front. Educ. Psychol. 2:43. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00043

Lloyd-Jones, G., Fowell, S., and Bligh, J. G. (1999). The use of the nominal group technique as an evaluative tool in medical undergraduate education. Med. Educ. 33, 8–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00288.x

Lomas, L. (2002). Does the development of mass education necessarily mean the end of quality? Qual. High. Educ. 8, 71–79. doi: 10.1080/13538320220127461

Lomas, L., and Tomlinson, K. (2000). Standards: the varying perceptions of senior staff in higher education institutions. Qual. Assurance Educ. 8, 131–139. doi: 10.1108/09684880010372725

Mason, G., Williams, G., and Cranmer, S. (2009). Employability skills initiatives in higher education: what effects do they have on graduate labour market outcomes? Educ. Econ. 17, 1–30. doi: 10.1080/09645290802028315

McKenna, S. (2004). The intersection between academic literacies and student identities: research in higher education. South African J. Higher Educ. 18, 269–280.

Meyer, L. H., and Evans, I. M. (2005). Supporting academic staff: meeting new expectations in higher education without compromising traditional faculty values. High. Educ. Policy 18, 243–255. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.hep.8300086

Nixon, E., Scullion, R., and Hearn, R. (2016). Her majesty the student: marketised higher education and the narcissistic (dis) satisfactions of the student-consumer. Stud. High. Educ. 39, 927–943. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2016.1196353

O'Neil, M. J., and Jackson, L. (1983). Nominal group technique: a process for initiating curriculum development in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 8, 129–138. doi: 10.1080/03075078312331378994

Parker, I. (1992). Discourse Dynamics: A Critical Analysis for Individual and Social Psychology. London: Routledge.

Patterson, C., Stephens, M., Chiang, V., Price, A. M., Work, F., and Snelgrove-Clarke, E. (2017). The significance of personal learning environments (PLEs) in nursing education: extending current conceptualizations. Nurse Educ. Tod. 48, 99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.09.010

Pechar, H., and Park, E. (2017). “Academic careers during the massification of austrian higher education,” in Challenges and Options: The Academic Profession in Europe, eds M. Machado-Taylor, V. Soares, and U. Teichler (Zurich: Springer International Publishing), 143–166.

Pritchard, R. (2004). Humboldtian values in a changing world: staff and students in German universities. Oxford Rev. Educ. 30, 509–528. doi: 10.1080/0305498042000303982

Rhodes, C., and Nevill, A. (2004). Academic and social integration in higher education: a survey of satisfaction and dissatisfaction within a first year education studies cohort at a new university. J. Further High. Educ. 28, 179–193. doi: 10.1080/0309877042000206741

Riesman, D. (1980). On Higher Education: The Academic Enterprise in an Era of Rising Student Consumerism. Chicago, IL: Transaction Publishers.

Ross, M., Perkins, H., and Bodey, K. (2016). Academic motivation and information literacy self-efficacy: the importance of a simple desire to know. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 38, 2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lisr.2016.01.002

Sabates, R. (2008). Educational attainment and juvenile crime area-level evidence using three cohorts of young people. Br. J. Criminol. 48, 395–409. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azn003

Senior, C., and Howard, C. (2014). Learning in friendship groups: developing students' conceptual understanding through social interaction. Front. Educ. Psychol. 5:1031. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01031

Senior, C., Howard, C., Reddy, P., Clark, R., and Lim, M. (2012). The relationship between student-centred lectures, emotional intelligence, and study teams: a social telemetry study with mobile telephony. Stud. High. Educ. 37, 957–970. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.556719

Senior, C., Moores, E., and Burgess, A. P. (2017). “I can't get no satisfaction”: measuring student satisfaction in the age of a consumerist higher education. Front. Educ. Psychol. 8:980. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00980

Senior, C., Reddy, P., and Senior, R. (2014). The relationship between student employability and student engagement: working toward a more unified theory. Front. Educ. Psychol. 5:238. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00238

Shor, I., and Freire, P. (1987). What is the“ dialogical method” of teaching? J. Educ. 169, 11–31. doi: 10.1177/002205748716900303

Sims-Schouten, W., Riley, S. C., and Willig, C. (2007). Critical realism in discourse analysis: a presentation of a systematic method of analysis using women's talk of motherhood, childcare and female employment as an example. Theory Psychol. 17, 101–124. doi: 10.1177/0959354307073153

Smeby, J. C. (2003). The impact of massification on university research. Tertiary Educ. Manage. 9, 131–144. doi: 10.1080/13583883.2003.9967098

Smith, R. A., and Peterson, B. L. (2007). “Psst what do you think?” the relationship between advice prestige, type of advice, and academic performance. Commun. Educ., 56, 278–291. doi: 10.1080/03634520701364890

Teichler, U. (1998). Massification: a challenge for institutions of higher education. Tertiary Educ. Manage. 4, 17–27. doi: 10.1080/13583883.1998.9966942

Thomas, L. (2002). Student retention in higher education: the role of institutional habitus. J. Educ. Policy 17, 423–442. doi: 10.1080/02680930210140257

Tissington, P., and Senior, C. (2017). Research activity and the new pedagogy: why taking part in research is essential for effective learning. Front. Psychol. 8:1838. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01838

Tomlinson, M. (2017). Student perceptions of themselves as ‘consumers’ of higher education. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 38, 450–467. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2015.1113856

Towl, M., and Senior, C. (2010). Undergraduate research training and graduate recruitment. Educ. Train. 52, 292–303. doi: 10.1108/00400911011050963

Trow, M. (2000). From mass higher education to universal access: the American advantage. Minerva 37, 303–328. doi: 10.1023/A:1004708520977

Van de Ven, A. H., and Delbecq, A. L. (1974). The effectiveness of nominal, Delphi, and interacting group decision making processes. Acad. Manage. J. 17, 605–621. doi: 10.2307/255641

Varga-Atkins, T., McIsaac, J., and Willis, I. (2017). Focus group meets nominal group technique: an effective combination for student evaluation? Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 54, 289–300. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2015.1058721

Varghese, N. V. (2013). Governance Reforms in Higher Education: A Study of Selected Countries in Africa. UNESCO. International Institute for Educational Planning. IIEP/SEM334/Themepaper. Available online at: http://www.iiep.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/News_And_Events/pdf/2013/Governance_reforms_in_HE_paper_PF.pdf (Accessed June 5, 2017).

Walker, I., and Zhu, Y. (2008). The college wage premium and the expansion of higher education in the UK. Scand. J. Econ. 110, 695–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9442.2008.00557.x

Walker, I., and Zhu, Y. (2013). The Impact of University Degrees on the Lifecycle of Earnings: Some Further Analysis. Research Paper for the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/229498/bis-13-899-the-impact-of-university-degrees-on-the-lifecycle-of-earnings-further-analysis.pdf

Williams, P. L., White, N., Klem, R., Wilson, S. E., and Bartholomew, P. (2006). Clinical education and training: using the nominal group technique in research with radiographers to identify factors affecting quality and capacity. Radiography 12, 215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2005.06.001

Winstone, N. E. (2017). “The ‘3 RS’of Pedagogic Frailty,” in Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience in the University, eds I. M. Kinchin and N. E. Winstone (Rotterdam: SensePublishers), 33–48.

Young, P. (2006). Out of balance: lecturers' perceptions of differential status and rewards in relation to teaching and research. Teach. High. Educ. 11, 191–202. doi: 10.1080/13562510500527727

Keywords: students, quality, nominal group technique, focus groups, higher education

Citation: Senior RM, Bartholomew P, Soor A, Shepperd D, Bartholomew N and Senior C (2018) “The Rules of Engagement”: Student Engagement and Motivation to Improve the Quality of Undergraduate Learning. Front. Educ. 3:32. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00032

Received: 29 June 2017; Accepted: 27 April 2018;

Published: 30 May 2018.

Edited by:

Steve Myran, Old Dominion University, United StatesReviewed by:

Caterina Fiorilli, Libera Università Maria SS. Assunta, ItalyCopyright © 2018 Senior, Bartholomew, Soor, Shepperd, Bartholomew and Senior. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carl Senior, Yy5zZW5pb3JAYXN0b24uYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.