- 1Kent State University, Kent, OH, United States

- 2Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA, United States

- 3New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM, United States

- 4Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, United States

Aspiring and practicing school leaders often identify graduate degrees as playing a significant role in achieving educational access and engaging in building, district-wide, regional, state, and national decision-making regarding practice and policy impacting marginalized populations in K–12 U.S. schools. The rationale behind initiating discourse on graduate student involvement grows out of current policy and reform initiatives requiring increased accountability for improved student performance, especially for children from predetermined “subgroups” due to race, class, native language, and ability (i.e., emotional, social, cognitive, and physical). The call for more deliberate involvement in understanding graduate admissions also arises in regard to student attrition and retention concerns. Faculty often play an under-examined role as gatekeepers throughout the admissions process. The way in which they understand graduate requirements, holistic evaluation, and merit affords opportunities to positively address significant implications for racial equity and diversity in graduate education. To understand faculty reliance upon graduate admissions criteria that undermine espoused university strategic plans, college-level diversity goals, and programmatic decision-making, four professors across the U.S. explore graduate admissions processes and the significance of implementing holistic admissions criteria. We present a holistic graduate admissions conceptual model for school leadership preparation programs to consider when increasing equity and access for minoritized candidates.

Although U.S. public schools have continued to address racial segregation as well as class inequality after Brown v. Board of Education Topeka (1954), race and class inequalities within K–12 schools continues to exist and influences inequalities found in higher education (Orfield et al., 2014). Although access to higher education for Students of Color (i.e., Black, Latino/a, and American Indian) may have improved since the 1950s Civil Rights Movement, most Students of Color attend public institutions while most middle class White students still attend private universities or colleges. Often, however, racial and class inequalities are often not recognized, questioned, or even challenged. In the dialog below (which does not represent a real conversation, is fictional, and has been constructed from experiences in multiple conversations, with multiple faculty, across multiple institutions as an example of our collective experiences), we present an example of how faculty sometimes discuss how they understand dimensions of equity, access, and multiculturalism, especially in recruiting candidates from diverse cultural backgrounds:

Admissions Committee Chair: We have a possible doctoral candidate who recently applied to our program.

Faculty #2: I read over his file. Tyrone has an extensive background working with Children of Color. He is a dean at a charter school, started a nonprofit to empower adolescents across the state, is a first-generation college student and presented at both regional and national conferences regarding his work with Students of Color.

Faculty #7: Tyrone mentors Latino students at his church. He also implemented a culturally responsive curriculum in his church youth groups.

Faculty #8: Social justice and equity seem to be at the heart of what he does as a leader. He grew up in an impoverished neighborhood, overcame challenges he faced, and is a first-generation college student. Wouldn’t we consider all of these factors during our admissions process?

Faculty #1: But is that actually enough to call him a leader? [Long pause]

Faculty #8: He’s just a dean? That’s a leader? And his GRE scores are quite low.

Admissions Committee Chair: How do you understand what it means to be a leader?

Faculty #1: What kind of question is that? He was not an assistant principal, director, or principal?

Faculty #2: Let’s just stop right there. He is a dean, not a principal and he has low GRE scores? I don’t think he should be eligible if he hasn’t been a principal. I don’t care what he wants.

Faculty #8: Why does Tyrone need a doctorate anyway? He is just a dean. What’s he going to do with it? Everyone knows you don’t need a doctorate to work in schools.

Faculty #3: Are you kidding me? I am offended by these comments. Tyrone has extensive experience in leading diverse groups of people. He worked with Young Men of Color state-wide … and if we look at him holistically, I don’t think we can make the GRE score hold him back.

Faculty #1: I need to be convinced Tyrone has what it takes to be a doctoral student here.

Admissions Committee Chair: What information do you need to determine whether or not Tyrone should be accepted into our doctoral program?

Faculty #1: He doesn’t meet my criteria for being here. His scores are low and his only experience as a traditional leader is that of a dean? He doesn’t belong in our doctoral program.

Faculty #2: I think you are asking us to lower our standards. If we start letting candidates like Tyrone into our program, we are setting a new precedent. I am not supporting that.

Faculty #3: What criteria are both of you referring to? Tyrone has extensive experience in the state, church community, and locally. His professional experiences align with our vision and commitment to recruiting candidates from diverse backgrounds. Don’t we want students who are from diverse racial, ethnic, linguistic, religious, and economic groups? Most of our students identify as White, middle class, heterosexual, Christian, English speaking, American citizens, and educators who have chosen to work in the suburbs.

Faculty #4: I didn’t think we were expected to actually recruit students? That’s not our job. We should wait for people to apply to our department.

Faculty #5: I think we should take actions to meet students from diverse school communities across the country.

Faculty #6: It’s not our job as faculty.

Faculty #3: Do we not want students to have equal opportunities to participate in our leadership program? Our population of current students who identify as Black, Latino/a, or Native American is less than 1%? How does this align with the institution’s goal to increase the number of Students of Color?

Faculty #7: Are we committed to this or not?

Admissions Committee Chair: According to what was presented, Tyrone engages in real community outreach and presented conference papers to several regional, state, and national organizations.

Faculty #3: I think we should support this candidate. He is an emerging school leader. His experiences are aligned with what we want from our doctoral students.

Faculty #1: I can’t support Tyrone.

Faculty #4: I can’t support him either.

Faculty #5: No. I think he needs another program that can meet his needs.

Faculty #2: I am not going to lower my standards for someone like Tyrone. He will need to find another doctoral program. Maybe he can find a program in an urban community or online.

The above dialog illustrates the extent professors can act as gatekeepers throughout the graduate student evaluative processes. Several red flags emerge including, but not limited to the following: (1) a limited understanding of cultural diversity; (2) an absence of counter narratives from members of the emerging cultural majority in discussion-oriented courses; (3) a limited number of Students of Color, especially students who identify as Latino/a and Black, which may lead to increased racial isolation for these specific groups of students within their higher education academic careers; and (4) contradictions among the university’s/college’s diversity goals and holistic admissions policy to utilize an applicant’s cultural identity (e.g., race, class, and educational attainment). Many argue the committee should not consider the department’s broader goal of achieving educational benefits of cultural diversity and the extent by which accepting this candidate would align with a cultural diverse admissions policy. Most colleges and universities such as this may identify their admission policies as holistic, which suggests decision-makers view the totality of an applicant (i.e., grade point average, test scores, recommendations, lived experiences, activities, and so forth). However, admission processes, such as the one noted in this dialog, are often unknown to outsiders and, sometimes, taken for granted by professors within the admissions process (Chang, 2002; Boske, 2010a).

This dialog provides a springboard to further discuss the need for universities/colleges to increase student diversity and attract greater numbers of low-income students to higher education (Castles, 2004) through more inclusive, holistic admissions criteria. For the purpose of this article, when we refer to holistic criteria, we suggest there is a need to recognize cultural diversity (i.e., race, ethnicity, class, religion/beliefs/faith, abilities (i.e., cognitive, social, emotional, and physical), geographic location, sexual orientation, gender, gender expression, educational attainment, family structure, citizenship, and other areas of difference), and social equality (i.e., ensuring diverse groups have equal opportunities to actively participate in higher education). First, we explore the need to promote of diversity initiatives within universities. Second, we examine the racialization of educational opportunities in higher education. Third, we investigate racism in higher education. And finally, we propose a conceptual model to provide faculty and administrators ways to critically think about the influence of implementing holistic sociocultural inquiry admissions model to promote equal opportunities for marginalized populations.

The Need to Promote Diversity Initiatives

Faculty interested in promoting diversity initiatives, especially when considering how to recognize the extent to which their admissions process is situated within multicultural and social equality dimensions, may want to conceptualize what they are attempting to achieve. Those who want to address the reversing of the educational gap for Students of Color, as well as other minority groups, may consider the following questions: (1) To what extent is race a barrier to attaining equity within our educational leadership program? (2) How do faculty participate in the admissions process? (3) To what extent do faculty play a role in initiating changes within the institution to increase equity for students from marginalized populations? (4) To what extent does the school leadership preparation program create environments in which all students experience justice and cultural recognition? (5) How do faculty understand what is meant by a holistic admissions process? (6) How do faculty understand what is meant by diversity? (7) What data are collected regarding who is and who is not admitted into the educational leadership preparation program? and (8) What data are collected throughout a candidate’s experience within the program to examine to what extent a candidate has a sense of self-respect, cultural recognition, and caring? (Boske, 2010a; Dowd and Bensimon, 2015).

With U.S. classrooms experiencing the largest increase in the number of first-generation immigrants since the early 1900s, it is important to note that less than 10% of immigrants come from Europe; and knowing this, and the significance this demographic shift plays in Students of Color matriculating to universities, this influx will and does have a significant role in understanding how to increase culturally diverse populations within universities (Camarota, 2011). We also may conclude that if this current demographic trend continues, Students of Color will be the majority in K–12 U.S. school populations within the next 20 years. And when we consider the influence of increasing immigrant populations, this too, will also impact language and religious diversity (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). If higher education institutions are to provide access to increasingly diverse students, then promoting practices and policies related to the education of racial, cultural, ethnic, linguistic, and other groups in the United States will play a pertinent role in addressing the inequities historical minority populations face in schools. Dimensions of content integration, culturally responsive pedagogy and curricula, equity, explicit/implicit bias, micro/macroaggressions, authentic integration, dismantling oppressive structures, and empowering institutional culture and social structures will be essential in facilitating a movement toward increased equity for all students.

The process of deepening understanding of the extent policies and practices perpetuate inequality for students, especially students from marginalized populations, is the first step to addressing the power institutional culture plays in affording students access to higher education (see Haney-Lopez, 2006; Boske, 2010b; Yim et al., 2012). The message is compelling considering often students with the highest grades and test scores seem to have greater access to opportunities within higher education—and these students are often from privileged backgrounds (Dowd and Bensimon, 2015). However, when we consider the impact of an oppressive educational system on educational access for marginalized populations due to race, class, ability, native language, and other dimensions of diversity, admissions decision-making may be more complicated. Recruiting a more racially and socioeconomically diverse group of students may be theoretically aligned with a university’s vision and mission; however, these aspirations are not always authentically integrated into policy and practice. Thus, how do faculty and administrators understand the extent vision and mission influence their university strategic plans? To what extent do university strategic plans impact department policies and practices, as well as faculty handbooks? and When we consider what is happening in classrooms, how do policies and practices translate into student recruitment, expectations for students, student outcomes, attrition, and student graduation? Moreover, how do faculty and administrators understand the need and demand for more culturally diverse representation with antiquated admissions criteria, which may be applauded for being progressive rhetoric, but may actually be quite difficult to navigate, implement, and sustain.

We begin by examining ways faculty may assess and make sense of holistic admission graduate admission processes to begin addressing disparities among marginalized populations within school leadership preparation programs. We consider the promotion of holistic candidate reviews as a social co-constructed admissions process. This examination is dependent on subjective processes including judgment, social and institutional constraints, and cultural bias faculty and administrators. In this article, we focus specifically on ways in which faculty and administrators understand cultural diversity (Dowd and Bensimon, 2015), which may or may not include race and ethnicity (Klitgaard, 1985) or merit. Although the notion of merit often drives academic evaluations (Lamont, 2009), merit is often socially constructed, contextually based, and contested (Espeland and Sauder, 2007). Research on graduate admissions suggests merit is understood as a myriad of a candidate’s goods and comparatively evaluates candidates against one another as well as themselves (Stevens, 2008). When considering a candidate’s goods, this may include but is not limited to Graduate Record Exam (GRE) scores. These scores are often considered strong predictors of graduate admissions (Sternberg and Williams, 1997), as well as professional competency, personal goals, transcripts, and identified race/ethnicity (Campbell, 2009; Dowd and Bensimon, 2015). Therefore, dynamics of merit are often subjective when considering what matters throughout an admissions process (Wechsler, 1977).

The Grutter v. Bollinger (2003) Supreme Court case considers the role of merit and cultural diversity in creating diverse learning environments in which students from cross-cultural groups promote cross-cultural understanding, eliminate deficit-laden attitudes, beliefs, practices, as well as prepare students to succeed in an increasingly culturally diverse and globalized society. The case suggests faculty and administrators actively engage in equity mindedness, which is not only an awareness of equity issues facing marginalized populations but also encourages administrators and faculty to actively engage in addressing equity issues within their higher education institutions. The Association of American Colleges and Universities (2016) reiterated the urgency for the integration of inclusive excellence noting how critical this practice is to the well-being of promoting a democratic culture. The AACU’s guiding principles for access and student success are designed to promote diversity, equity, and quality educational efforts to address inclusion and the well-being of a democratic culture in higher education. The promotion of diversity, inclusion, and equity are at the heart of their work. Building upon these practices is essential to organically creating, implementing, and sustaining institutional change.

These practices also encourage higher education institutions to “leverage diversity for student learning and institutional excellence” (Milem et al., 2005). Therefore, in an effort to better understand how educational administration programs can implement a holistic admissions review process, we examine the need to recapitulate dialog regarding cultural diversity and enact justice-oriented practices and policies to promote equitable access to these programs.

The Racialization of Educational Opportunities

It seems to me that before we can begin to speak of minority rights in this country, we’ve got to make some attempt to isolate or to define the majority—James Baldwin (p. 229).

Racism in schools continues to be a difficult, complex, and pressing issue facing U.S. schools. Even though racial segregation, as well as race and class inequality, is still pertinent issues within U.S. schools, some people seem surprised. Why? People consider the Brown v. Board decision as the elimination of racial segregation. However, even with the 50th anniversary of the March in Washington and the Civil Rights Movement, it is important to realize historical racial inequalities have not diminished, but, rather, have continued since the 1950s and perpetuate apartheid education in U.S. schools (Kozol, 2006; National Center for Educational Statistics, 2015a). The question of race refers to the extent educational contexts and the racialization of educational opportunities influence students’ experiences in school are influenced by their skin color or other cultural diversity attributes. In turn, the extent these cultural attributes influence a student’s experiences with social, cultural, socioeconomic, psychological, or political contexts is characterized as racialization (Teranishi and Briscoe, 2006). When considering the influence of segregation on children across this country, not only are children separated according to their racial and ethnic backgrounds, but the schools these children attend also differ in regard to student outcomes between White and Asian students in comparison with Black, Latino/a, and American Indians (Clotfelter, 2004). As researchers emphasize and document these demographic and geographic trends, segregation also plays an important role in understanding the lived experiences of marginalized populations, because segregation also leaves minoritized children feeling inferior (Orfield and Yun, 1999; McNamara Horvat and O’Connor, 2005). Key findings from the impact of continuous racial segregation illuminates that the intractable race and class inequality in K–12 schools also exists in higher education institutions (Jencks and Mayer, 1990; Jencks and Phillips, 1998).

Those in higher education are not immune to issues of race, racism, or the impact of socially constructed cultural identities, especially when considering minoritized students and college or university admissions. The field of educational administration scholarship does not seem to have language or tools to collectively engage in critical dialog regarding equitable access or ways to hold ourselves as faculty and administration for equitable outcomes [see discussions in higher education with Bensimon and Bishop (2012)]. There is a need to engage faculty and administrators in dialog regarding how to make sense of equity and accountability when considering the extent practices and policies address historical discriminatory practices. Because, often times, as suggested in the opening dialog at the beginning of this article, the legacies of racism are often not challenged, recognized, or questioned.

Faculty and administrators have the capacity to play a significant role in enacting equity-oriented policies and practices within their institutions, especially when considering the admissions process, curricula, and pedagogy (Stanton-Salazar, 2001). As faculty examine the extent their university engages in inclusive excellence and how these practices align with student cultural diversity, those engaged in this process may discover the extent their educational institution provides sufficient resources for minoritized students, especially Students of Color, as well as providing these students with ample learning opportunities. By Students of Color, we refer to communities with members of emerging majority minority populations who identify as Black, Latino/a, and American Indian (Orfield, 2001).

The goal of investing racialization within higher education actively engages faculty and administrators in promoting inclusive excellence by addresses the extent they embrace cultural diversity through policy and practice. Well-intentioned faculty and administrators need to be aware of challenges they may face along the way. As they pursue equity-oriented goals and outcomes for the school leadership preparation programs, some of these challenges may include, but are not limited to, deepening awareness at both the self and institutional level regarding color blindness, structural racism, meritocracy, and values aligned with equity-oriented work (Haney-Lopez, 2010). To authentically engage in the process of providing diverse student groups with equal access to higher education, Castles (2004) suggests two pivotal dimensions of diversity be placed at the center of this work: (1) recognition-addressing how the U.S. publicly claims the promotion and integration of cultural diversity and (2) social equality-taking steps to promote equal access to educational institutions for diverse populations.

Integral to this conversation is the discussion of diversity—both representational and pluralistic. When approaching graduate admissions criteria from a holistic perspective, it is important to understand the difference between representational and pluralistic diversity. According to Osanloo and Reyes (2013), representational diversity focuses on having different groups (whether racial or ethnic, by gender, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, etc.), represented in different areas of university/institution life, including, but not limited to: leadership, departments, programs, policy, student life, and academics. Pluralistic diversity is an imperative that pushes the boundaries of representational diversity. The tenets for pluralistic diversity are as follows: (1) inclusion of diverse representation in the various facets of the university/institution; (2) diversity is nurtured and engaged; (3) works toward creating a community of belonging; (4) participation is democratic and deliberative; and (5) each individual is a stakeholder in the success of the university/institution (Osanloo and Reyes, 2013, p. 1085). The benefits of approaching graduate admissions criteria from a pluralistic perspective are that it champions diversity from an integrative and mission-based focus so that the university and institution can transform, progress, innovate, and thoughtfully engage each of the necessary constituents. Moreover, pluralistic diversity serves the public interest.

Engaging in Issues of Race and Racism in Higher Educations

Students who identify as White continue to be the most segregated population in U.S. schools, because the majority of students served identify as White (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2015a). For students attending schools in the south and west, they are more likely to attend more racially diverse schools and attend schools with children living in poverty (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2015b). However, for those attending private schools, Whites are even more racially segregated than their K–12 public school counterparts. In regards to postsecondary attendance patterns based on race and ethnicity, 67% of all undergraduates attending nonprofit institutions in 2013 identified as White, while 30% of Black students attended private for-profit institutions versus 12% at public institutions or nonprofit 4-year institutions at 13%. For Latino/a students, 15% of students attended public and private institutions, and 10% attended nonprofit 4-year institutions (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2015c). For attendance in graduate programs, disparities between White students and Students of Color increase significantly. Attendance patterns reflect 70% of White students attend graduate school in comparison with 37% of Black students and 9% of Latino/a students (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2015c).

Although U.S. schools actively participate in apartheid education (Kozol, 2006; Frankenberg and Orfield, 2012), the school-to-prison pipeline (Ladson-Billings, 2005; Kim et al., 2010; Alexander, 2012), and provide limited resources to children who live in poverty (Gorski and Landsman, 2013; Milner, 2015), discussions regarding the influence of disenfranchisement of marginalized populations within higher education are often overlooked. To address the perpetuation of exclusive practices within higher education, those working in U.S. educational systems will need to deepen their understanding of cultural minority and majority groups, oppression, colonization, and disenfranchisement (Gay, 2010; Boske, 2010b; Bensimon and Malcom, 2012). For faculty who are members of the cultural majority (i.e., White, middle/upper class, English speaking, U.S. citizens, heterosexual, and Christian), they may be more reluctant to identify themselves as members of the cultural majority, because they may need to utilize their majority status to address structural transformations to promote inclusive excellence within educational settings. And for those collaborating with educators, school leaders, and professors who identify as members of the cultural majority, they may discover some of these members may dispute the existence of structural racism as well as their responsibility to disrupt these oppressive practices, ideologies, and policies within educational settings (Guinier and Torres, 2003).

Faculty involved in promoting increasing cultural diversity may not only need to deepen their awareness of racialized educational practices, in addition, they may want to explore ways to promote diversity through culturally responsive curriculum (Nieto, 1999, 2000; Murrell, 2002; Howard, 2003), social justice pedagogies (Bogotch and Reyes-Guerra, 2014), as well as inclusiveness (Dowd and Bensimon, 2015). Faculty within educational leadership programs can play a critical role as gatekeepers throughout the graduate admissions process. Admission into graduate school is essential for candidates and their educational career due to licensure and degree requirements across the country (i.e., superintendency, principalship, and professoriate). Faculty are in positions of power that may hinder the progress of supporting a more diverse workforce reflective of increasingly diverse societal demographics, specifically Communities of Color (Posselt, 2014).

Criteria for evaluating who is afforded access to selected seats in college, irrespective of ideological, demographic, economic, and sociological backgrounds have become the sole responsibility of faculty. They in turn, review potential applicants through the lens of their own worldview and understanding of applicants’ backgrounds (Guinier, 2003). Therefore, if faculty have a more philosophical bent toward quantitative criteria (e.g., GRE scores) within an admissions policy, applicants who identify as Students of Color and from low socioeconomic backgrounds will be significantly hindered in the admissions process (American Psychological Association, and Presidential Task Force on Educational Disparities, 2012; Miller and Stassun, 2014). And as a result, holistically reviewing candidates for the possible graduate admissions has been widely contested within higher education (Posselt, 2014). And although self-awareness through critical perspectives may be uncommon, it may be essential to addressing racialized inequities (Dowd, 2008).

Faculty utilizing holistic evaluation policies for graduate admissions may begin discussing holistic reviewing processes by engaging in dialog regarding equity mindedness (Valencia, 2010). The concept of equity mindedness is language that often encompasses cultural assumptions. These assumptions often contrast with deficit mindedness, which perpetuates language and practices that creating underlying assumptions about what causes exclusion or minimum numbers of marginalized student populations in graduate programs (Valencia, 2010). Cultural assumptions about preparedness, aspirations, inquiry protocols, and qualitative data collections should be discussed, especially in discussing how often deficit-laden assumptions influence how candidates are evaluated using a perceived holistic evaluation process. For example, terms such as leadership, potential, dispositions, and experience create opportunities for professors to engage in critical dialog regarding how they understand what is meant by holistic evaluative processes.

Vague and ambiguous graduate admissions policies may leave room for an unfair and inequitable interpretation of who should be granted access and who should be denied. To promote a fair and equitable admissions review, committees need to reassess their admission policies and practices. Numerical data, such as GRE scores, GPA, and transcripts, may already easily accessible within university data bases; however, there is a need for these numerical data points to be further analyzed to better understand the experiences of and admission outcomes for Students of Color. Some questions to consider when considering the quantitative data are as follows: (1) What data are collected throughout the admissions process? (2) Is data narrowly defined as quantitative? (3) Do admission policies emphasize grade point averages and entrance exam scores? (4) Is qualitative data collected by admission board members? (5) To what extent do faculty understand the lived experiences of Students of Color as they apply for graduate programs? (6) To what extent do faculty assess the quality of educational practices from a race-conscious perspective? (7) Do faculty collect data through observations, document analysis, and interview Students of Color to deepen our understanding of ways to assess educational access? (8) To what extent is the content of inquiry-based protocols throughout the admissions process influenced by a race-conscious lens? (9) To what extent are faculty aware of the influence of their own practices within the admissions process (Bensimon et al., 2004)? and (10) To what extent do faculty utilize these understandings to engage in equity-minded race consciousness throughout the interpretation of the data (Bensimon and Malcom, 2012)?

Holistic Review Process

A holistic review process, also known as a full admissions review process, provides faculty, who are in the role of powerful decision-makers, with a myriad of candidate credentials. Examples of these credentials include, but are not limited to (1) portfolios; (2) behavioral interviewing; (3) writing samples; (4) displaying an understanding of the vision and mission of the department; (5) interdisciplinary knowledge and experience; and (6) social justice-minded work and activities. These credentials afford reviewers with artifacts and indicators informing faculty of a candidate’s qualities they believe will contribute to successful completion of the degree program. A holistic review examines the extent by which the applicant not only meets academic qualifications for admission, but also demonstrates dispositions, skills, knowledge, and experiences that may facilitate degree completion and success upon graduation (see Alon and Tienda, 2007; Bensimon, 2007).

A holistic review emphasizes and ensures no single factor leads to accepting or excluding a candidate from program admission. More importantly, one of the key elements to this process includes the recognition of a candidate’s strengths and the extent a candidate’s strengths may offset possible challenges (Hardigan et al., 2001). When faculty carefully weigh the candidate’s strengths, achievements, service, and ways in which the candidate may contribute to the graduate degree program and educational environment, they increase the likelihood the candidate may be offered admission to those who are most likely to succeed (Hardigan et al., 2001).

When considering the parameters of admission policies, the more limited mode of assessing candidates for possible admission often places significant value on only a few attributes which are numerically quantified (i.e., grade point average, standardized test scores) (Sternberg and Williams, 1997; Micceri, 2002). This quantitative approach to reviewing candidates is based on the belief that standardized tests, such as the GRE, are the best indicators of an individual’s academic ability and capacity to achieve success within a program. However, this practice is not encouraged by the Educational Testing Service (ETS). In essence, the Education Testing Service (2015) suggests the GRE does not and cannot accurately measure a candidate’s skills or the extent these skills are associated with academic and professional competence. ETS urges faculty and administrators who utilize the standardized test score to recognize the limitations of any single measure of knowledge and ability to determine a candidate’s rate of success. The narrowly defined practice does not consider a candidate’s full range of abilities and often overlooks valuable indicators of preparedness for degree completion, as well as the candidate’s contributions to the program.

Credentials for holistic admission reviews include academic qualifications (i.e., grade point average, GRE score), however, there are multiple lenses utilized to measure and understand an applicant’s academic skills. These considerations include, but are not limited to (1) gauging the curricular rigor in prior institutions; (2) cumulative grade point average within a wider context of the academic record; the maturity, intent, and sophistication of the goal statement; (3) extent of prior experiences in the field; (4) recommendations; (5) standardized test scores; (6) service to the community; and (7) correspondence between the candidate and faculty members (Sedlacek, 2004). The holistic review process places the candidate’s academic skills and achievements within a wider school-community context and examines the effect the candidate may have in not only completing the degree program, but contributing to the community-at-large as a school leader. This ability may be indicated by the candidate’s leadership experience, the level of involvement and progression of programming, a demonstrated passion for this work in schools and its alignment to the disciplinary interests; initiated and sustained community involvement; possible research endeavors; and talents aligned with possible and effective employment. Several indicators that take into account the whole student measure efficaciousness.

Higher rates of completion are seen when academic achievement and related skills are taken into account during the admissions process. For example, the National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowships (2016) and the Gates Millennium Scholars (2016) use a holistic review process to select graduate awards. Furthermore, the Education Testing Service (2009) and the GRE Board concluded there is a need to offer candidates a Personal Potential Index as an option within the test. Faculty who engaged in this evaluation process assessed students on a 6-point scale in the areas of creativity, knowledge, communication skills, planning, organizing, communication skills, ethics, resilience, and integrity. This holistic review process may be viewed as more rigorous and individualized because it requires faculty to make considerations for more highly qualified candidates by broadening the scope of admissions criteria. This reified vision for review is critical to the admissions process. Rather than focusing on academic achievement and a single standardized test score to measure candidate success, the holistic review process considers not only academic performance but also a student’s potential to contribute to the community-at-large via research as well as the individual’s commitment to educational success.

Holistic Sociocultural Inquiry Admissions Model

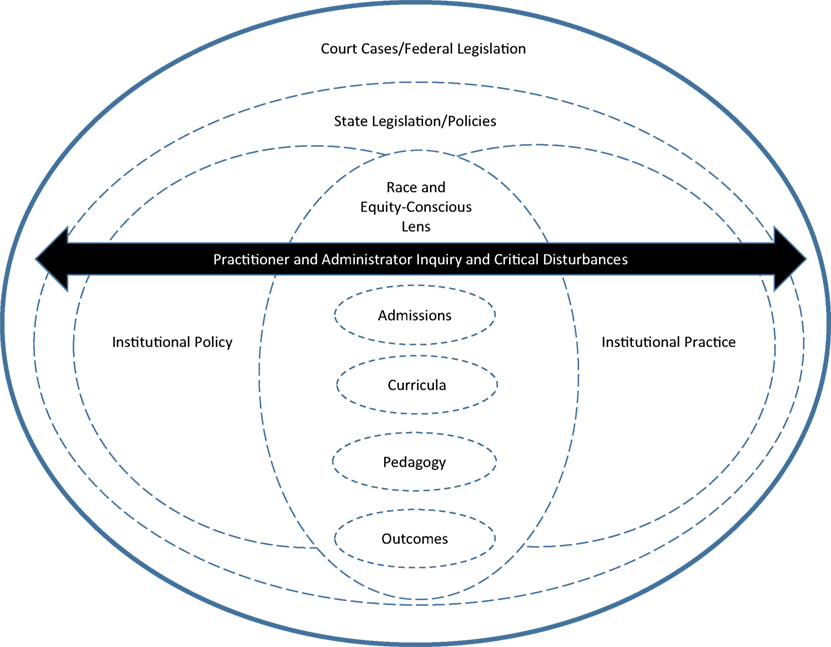

Although issues of implicit and explicit cultural bias illuminated in the vignette at the beginning of this article may not dramatically shift simply by changing a College’s admissions process, we call upon decision-makers to deepen their understanding regarding the implementation and possible consequences associated with promoting holistic admission processes. In this article, we assert that those who engage in admission processes consider integrating the holistic sociocultural inquiry-centered admission’s model conceptual model we created as a critical starting point (see Figure 1). Furthermore, as noted earlier within the hypothetical committee discussion, this model encourages institutional members to look within and reflect on the extent admission processes align among programs, faculty, practices, and policies. In other words, faculty and other decision-makers are responsible for considering the influence of beliefs, attitudes, and practices, especially when considering who is and who is not deemed qualified for candidacy. Reflecting on the influence of data-driven decision-making may reveal an institution’s tendencies, and possibly, outright biases. These understandings might encourage universities to justify their practices and policies while providing candidates with opportunities to better understand which universities align with their values, beliefs, and opportunities for growth.

Our conceptual model draws on the need to promote holistic sociocultural inquiry to implement race and equity-conscious practices and policies throughout the admissions process as well as through the intellectual community of an institution at-large (see Figure 1). Relationships among federal policy/legislation, state policy/legislation, institutional practices and policies, practitioners, administrators, and candidates are essential to understanding what is working, why it is working, what is not working, and why it is not working. This holistic sociocultural inquiry-centered admission’s model is based on the belief that deepening ways of knowing and responding to race and equity consciousness is essential to supporting the acquisition of culturally responsive practices, policies, and experiences throughout the admissions process.

The way in which we, as faculty and administrators, made meaning from our experiences as practitioners not only influenced how we engage with others, but the extent to which we engage in remediating artifacts and jointly producing decisions and actions toward disrupting institutional and structural racism. These practitioner-centered inquiries were and still are intended to expand learning and sense of purpose within institutions and the profession of educational leadership (Engeström, 2001). As faculty gain practical wisdom to promote culturally responsive work within their institutions, often times, they may experience resistance from administration and colleagues. This resistance, however, may be necessary to examine programs through a race and equity-conscious lens. The resistance provides opportunities to address contradictions among institutional data, vision, mission, and programmatic practices. Those engaged in the admissions process may understand these contradictions as critical disturbances. Each of these critical disturbances affords faculty and administrators opportunities to utilize these gaps in understanding alignment between practice and policy as a means to promote authentic culturally responsive curricula, pedagogy, and outcomes. Therefore, each critical disturbance functions as a catalyst for individual and organizational learning. Not only do these catalysts encourage practitioners and administrators to examine institutional data, they support them in promoting dialog regarding the extent these data aligned with national policy, state mandates, institutional practices, research, and experiences of marginalized populations, and in this case, Students of Color. Within this conceptual model, critical disturbances are recognized, valued, and understood as opportunities to re-envision admission processes, curricula, pedagogy, and outcomes for Students of Color in an effort to promote a race and equity-conscious lens. The principles of social justice, care, and humanity as transformation emphasize the significance of promoting culturally responsive and inclusive pedagogies and curricula (Paris, 2012). However, the faculty’s capacity to face and develop demands they face throughout this examination will play a critical role in developing cultural competencies to carry out these transformations (Bensimon, 2007).

The holistic sociocultural inquiry admissions model encourages organizational change, which begins from within. The model encourages faculty and administrators to consider the influence of beliefs, attitudes, and insights of those who serve as practitioners, or in this case, as admissions committee members selecting candidates. This inquiry-based model calls on for those who hold positions of power within the institution to examine how they understand the purpose of maintaining the status quo as well as the ways in which organizational change may be enacted (Seo and Creed, 2002; Battilana, 2006). This model draws upon sociocultural theories of learning that suggest how faculty develop ways of knowing is related to cultural, institutional, and historical contexts; therefore, social interactions and culturally organized activities influence how faculty make meaning (Chaiklin and Lave, 1993; Cole and Engeström, 1994; Cole, 1996; Nasir and Hand, 2006), and thus, decisions made.

The dotted lines suggest relationships exist among federal policy, state mandates, institutional practices and policies, and programmatic outcomes (i.e., admissions, curricula, pedagogy, and outcomes). As faculty and administrators engage in promoting race and equity consciousness within their institutions, they may recognize the extent critical disturbances functioned as catalysts within their programs. Examining an institution’s vision, mission, diversity statements, marketing, retention rates, curricula, pedagogy, assessments, experiences of Students of Color, admission requirements, and outcomes to address institutional logic may be critical in promoting this work. As substantive disagreements emerge between strong indicators of contradiction within an admissions process and institutional strategic plans to improve their practices, faculty may find themselves addressing the values and meaning making about programmatic purpose. The reflective dialog may become a strong indicator for the need to further examine contradictions among policy, practice, values, attitudes, and institutional logics challenging the extent different institutional actors attached different meanings to the same actions.

These critical disturbances afford those involved in the admissions process with opportunities to address contradictions as institutionally illogical and as an attempt to reframe divergent understandings of what it means to holistically evaluate candidates for graduate admission. This conceptual model suggests practitioner and administrator inquiries provide spaces to actively engage in decisions and actions aligned with new understandings. These new understandings have the capacity to lead to new conceptualization of institutional logics and propose inquiry-centered efforts align with decision-making, actions, and beliefs. As faculty continue to engage in this significant work, they may recognize racialized power imbalances and the extent these imbalances influence how they make meaning from their work. This conceptual model is not an attempt to persuade faculty and administrators to change their admission policies and practices. Rather, to involve each of them in an ongoing authentic inquiry in which divergent views are considered when thinking about what it means to promote race and equity consciousness.

The model encourages admissions decision-makers to clearly identify and explain their admissions processes in clear, concise, and compelling ways, especially for those outside of the admissions fold. Factors that affect candidate’s opportunities for admittance within various institutions may not be precise; however, institutions may present a host of distinct interests encouraging candidates from diverse backgrounds and experiences to apply. As a result, within this conceptual model, selective institutions embed these authentic and comprehensive holistic understandings throughout their curricula, vision, mission, pedagogy, and student outcomes. This process relies upon the professional judgment, expertise, and ways of knowing and being of institutional decision-makers. Together, they assess applicants beyond mechanical processes in which a limited number of factors may influence a candidate’s academic access; and moreover, understand a candidate as an individual with the capacity to achieve the institution’s mission and vision.

The conceptual model does not assert one means of implementing the process. What the model suggests are inclusive practices and policies in which institutional members evaluate, reconsider, revise, and implement their institutional goals and priorities; in other words, the model encourages grass root movements. For example, academic and personnel, as well as personal factors, play a significant role in developing a holistic admissions process. Some institutions may seek candidates from specific areas of study while others may focus on recruiting candidates across states or adhering to specific religious affiliations. However, those involved in the decision-making process should consider the implications of committee review, paired admission officers, internal reviewers, and in some cases, external application reviewers.

The variability among institutions should be transparent; in other words, public perception a selective admissions should involve a myriad of inputs throughout the process, align with the institution’s values, practices, and policies versus a selective admissions process mirroring a black box. The conceptual model asserts institutions engage in a transparent admissions process and demonstrates the extent at which candidates’ experiences, interests, and lived experiences are not only valued throughout the holistic review, but continue to be honored throughout the candidate’s academic career at the university or college.

A candidate’s distinctive experiences, talents, and perspectives should enhance the institution’s goals and priorities. One means of deepening the decision-makers’ understanding of applicants may be to encourage a process in which personal narratives are valued, including but not limited to a candidate’s background, lived experiences, as well as multiple mediums/ways an applicant may express themselves. These understandings of self may involve discussions regarding race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, gender, gender expression, native language, geographic location, family educational levels, religion/beliefs/faith, citizenship, or other aspects of identity that enhance how an applicant represents or understands oneself.

As institutions consider the implementation of this conceptual model, they may revisit the extent the college or university embraces the integration of a diversity statement. An admissions decision-making committee may utilize a diversity statement, goals, and/or priorities to support an applicant’s admission. For example, an institution may consider a candidate’s birth place, neighborhood, national origin, or even where a candidate attended school. Their decisions, therefore, become comprised of constellation of factors throughout the admissions process. In other words, the decision-makers consider an applicant’s intimate choices and lived experiences that often define a candidate’s identity, beliefs, and ways of knowing and being.

Throughout the admissions process, those in positions of power may want to discuss the following: (1) To what extent does the institution define cultural diversity? Is it clearly defined? Is it broadly defined? To what extent does this understanding include the lived experiences, interests, and talents of applicants? Why or why not? (2) To what extent if this understanding of cultural diversity embedded in the institution’s vision? Mission? Diversity statement? To what extent has this understanding been embraced by the faculty? By the leadership? (3) To what extent do departments across the college or university reflect the institution’s understanding of a holistic review process? Why or why not? (4) To what extent is the vision, mission, diversity statement, internal institution practices, and admissions aligned? (5) To what extent is this understanding clearly articulated throughout institutional policies including, but not limited to admissions processes, faculty handbooks, professional development, college/university-wide communication efforts (both internal and external)? (6) To what extent is the admissions process transparent, feasible, and accessible to the public? (7) To what extent do faculty, institutional leaders, and recruiters emphasize admission rates and success with university’s/college’s cultural diversity goals and priorities? (8) To what extent do students, families, community-at-large members, donors, and alumni articulate relationships among cultural diversity, success, and institutional excellence? Why or why not? (9) To what extent does the institution actively engage in evaluating their admissions processes, successes, challenges, and considerations for authentic revision? and (10) To what extent does student academic affairs, student admissions, and institutional departments aligned with resource allocation collaborate to better serve future, present, and graduated students? These questions assert institutional leaders move beyond traditional admissions processes and consider the implications of engaging in meaningful, inclusive opportunities that move institutions toward rich diversity within, throughout, and beyond the classroom.

We recognize efforts to invite equity-enhancing changes that engage faculty and administrators in developing new core organizational routines, beliefs, and attitudes influencing admissions, assessment, curricula, administration, services, and scholarly work are sometimes difficulty and complex work. However, understanding the relevance of critical disturbances as a means of actively engaging in this critical dialog and holistic admissions process is necessary to promoting this work. Therefore, we contend, all of the elements presented in this conceptual model are essential to promoting transformative justice when considering race and equity conscious in within a holistic admissions policy.

The number of critical disturbances experienced may inform faculty they are having an impact on increasing race and equity consciousness within their graduate programs. Decision-makers may want to evaluate the impact of current practices and/or policies. For example, when considering the initial dialog among admission committee members noted at the beginning of this article, several red flags emerged: (1) To what extent is socioeconomic diversity addressed within racial groups? (2) To what extent do discussions centered on race occur in courses and/or among decision-makers? and (3) What seems to contribute to the absence of Students of Color? Together, faculty may strive for culturally responsive praxis, which is at the core of these inquiries. As faculty consider the influence of praxis, they may understand the significance of authentically promoting and integrating a race and equity-conscious lens. Furthermore, this work requires a particular form of knowledge (i.e., wisdom), which often contradicts epistemic knowledge essential to building and reproducing functioning systems (Greenwood and Levin, 2005). This conceptual model promotes a praxis, which is practitioner-centered, because faculty must engage in critical reflection and collective action to promote just and culturally responsive work in understanding the admissions process, especially for those who identify as Students of Color (Seo and Creed, 2002). The contradictions and gaps noted throughout this hypothetical dialog noted at the beginning of this article create critical disturbances among faculty experiences within institutions, leading faculty to see and intentionally disrupt espoused policy and practice and actual practice (Argyris, 1977; Argyris and Schon, 1996; Seo and Creed, 2002; Engeström, 2009).

This conceptual model encourages those involved in promoting a culturally diverse graduate admissions policy to examine the extent culturalized inequities influence the practices and policies within a higher education. This important work urges faculty and administrators to consider the influence of sociocultural elements in understanding the impact of larger structural influences as well as microlevel influences regarding the implementation of inclusive policies and practices. For those involved in higher education decision-making (i.e., admissions, vision, mission, curricula, assessments, pedagogy, etc.), this model suggests greater attention be given to inviting members of different racial and ethnic groups to reconstruct unjust practices and policies within educational institutions. Faculty members should be involved in taking steps to end racial inequities influencing a myriad of student outcomes (i.e., acceptance, attrition, and graduation rates), especially those who experience racism or other forms of oppression. Their experiential knowledge provides opportunities to counter master narratives of equal opportunity, which are often dismissed or devalued (Noddings, 1999; Dowd and Tong, 2007; Rodriguez, 2013). Purposely inviting culturally diverse members to address the root causes of these culturalized inequities may suggest these institutional efforts will move higher education toward inclusiveness and right past wrongs. However, this conceptual model suggests knowledge alone will not improve diversity or equity within higher education. This model emphasizes the need for admission policies, programmatic practices/policies, and curricula/pedagogy to shift from being “diversity focused” to “race and equity focused” (Orfield et al., 1997; Wells, 2014).

This model addresses racism as one of the contributing factors to promoting unequal educational participation as well as tendencies for faculty to avoid conversations regarding the need to address the racialization within education. Chesler and Crowfoot (1989) argue racial injustices are maintained through contemporary policies and practices and as such, are often reflected in significant differentials regarding opportunities, educational access, and other outcomes that still exist between People of Color and their White counterparts. Unfortunately, racism is so embedded in day-to-day interactions within U.S. society that deficit-laden assumptions are ingrained in political, legal, and educational structures that they are, at times, unrecognizable (Coia and Taylor, 2009). Many White students do not understand or acknowledge the extent educational practices and policies can be discriminatory because they do not realize the extent racism is embedded within larger social organizational structures, such as universities (Haney-Lopez, 2010). Therefore, for those involved in graduate admissions, there is a need to pay closer attention to the ways in which higher education programs operate to pass on and reinforce historic patterns of privilege and disadvantage by deciding who will and who will not gain access to higher education (Chesler and Crowfoot, 1989).

This conceptual model reminds admissions decision-makers of the importance cultural diversity and authentic inclusive practices play within the admission processes. There is a need for universities and colleges to recommit to the essential work of diversity and inclusion, because institutions cannot achieve the educational benefits associated with admitting a diverse study body without culturally diverse students; and our institutions cannot enroll or retain these same students without a well-designed admissions process. Furthermore, this conceptual model provides a framework for articulating this admissions process in a clear and compelling manner, especially when considering the role universities and colleges play in deepening understanding regarding factors that may or may not affect admissions within various institutions.

Conclusion

Deepening awareness among faculty and providing spaces to consider and address practices rooted in unjust social arrangements for marginalized populations is essential to addressing racial inequities (Harper and Hurtado, 2011; Harper, 2012). Faculty, who are in decision-making positions, should carefully consider their admissions processes, how they are communicated, and the extent their policies align with curricula, goals, and institutional practices. Addressing critical aspects raised in the pursuit of a culturally inclusive and dynamic higher educational environment may be a step forward in promoting authentic holistic admission processes. Taking concrete actions, especially for those who are underrepresented, play a significant role in changing the institutional culture and learning environment. An institution’s efforts to address cultural diversity illustrate not only the seriousness of purpose behind a holistic admissions process, but the institution’s commitment to diversity.

Despite progress to improve access for racial groups, gaps between People of Color and their White counterparts still exist (Perna and Finney, 2014). The holistic sociocultural model addresses equity as the status of Students’ of Color lack of power, limited educational/economic/political assets versus the numerical underrepresentations in society or educational institutions (Gillborn, 2005). Although some postsecondary faculty and administrators may practice professional accountability with an explicit recognition of racism as a root cause of inequalities in U.S. schooling, there is a need for language to communicate the extent their knowledge is dismissed, disallowed, or considered too politically volatile to open a dialog about race and racism. This model encourages university practitioners to critically reflect on what is meant by equality of opportunity, align practice and policy from the inside out, and utilize inquiry-based reflection to promote critical disturbances, therefore, urging those involved in graduate admissions to consider addressing equity in a more concerted effort in their interpersonal, institutional, and structural forms. As we look forward to the next three decades of population growth and demographic changes in this country, People (ergo Students) of Color will become the majority population. If deleterious racist trends in education continue and Students of Color remain relegated to the “under-educated” edupolitical class in this country, we are truly headed for an educational apartheid—one, which will have long-lasting and long-term effects on many facets of development within the United States.

Author Contributions

CB and CE led the discussion of the creation of this article with AO and WN. CB, CE, AO, and WN collaborated on the extant literature and framework. CB took the lead in developing the conceptual model. CB, AO, and WN took the lead on major revisions.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewers, CB and HL, and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

References

Alexander, M. (2012). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York, NY: New Press.

Alon, S., and Tienda, M. (2007). Diversity, opportunity, and the shifting meritocracy in higher education. Am. Sociol. Rev. 72, 487–511. doi: 10.1177/000312240707200401

American Psychological Association, and Presidential Task Force on Educational Disparities. (2012). Ethnic and Racial Disparities in Education: Psychology’s Contributions to Understanding and Reducing Disparities. Available at: http://www.apa.org/ed/resources/racial-disparities.aspx

Argyris, C., and Schon, D. A. (1996). “Organizational learning,” in Organizational Theory, ed. D. S. Pugh (New York, NY: Penguin Books), 352–371.

Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2016). Making Excellence Inclusive. Available at: http://www.aacu.org/compass/inclusive_excellence.cfm

Battilana, J. (2006). Agency and institutions: the enabling role of individuals’ social position. Organization 13, 653–676.

Bensimon, E. M. (2007). The underestimated significance of practitioner knowledge in the scholarship of student success. Rev. High. Ed. 30, 441–469. doi:10.1353/rhe.2007.0032

Bensimon, E. M., and Bishop, R. (2012). Introduction: why “critical”? The need for new ways of knowing. Rev. High. Ed. 36, 1–7. doi:10.1353/rhe.2012.0046

Bensimon, E. M., and Malcom, L. E. (2012). Confronting Equity Issues on Campus: Implementing the Equity Scorecard in Theory and Practice. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Bensimon, E. M., Polkinghorne, D. E., Bauman, G. L., and Vallejo, E. (2004). Doing research that makes a difference. J. High. Educ. 75, 104–126. doi:10.1353/jhe.2003.0048

Bogotch, I., and Reyes-Guerra, D. (2014). Leadership for social justice: social justice pedagogies. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social 3, 33–58.

Boske, C. (2010a). “A time to grow: workplace mobbing and the making of a tempered radical,” in Building Bridges: Connecting Educational Leadership and Social Justice to Improve Schools, eds A. K. Tooms and C. Boske (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 29–56.

Boske, C. (2010b). “I wonder if they had ever seen a black man before?” Grappling with issues of race and racism in our own backyard. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 5, 248–275. doi:10.1177/194277511000500701

Brown v. Board of Education Topeka. (1954). Available at: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/347/483/case.html

Camarota, S. A. (2011). Achieving Equity for Latino Students: Expanding the Pathway to Higher Education Through Public Policy. New York, NY: Teachers College Record.

Campbell, J. (2009). Attitudes and Beliefs of Counselor Educators Toward Gatekeeping. Dissertation, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA.

Castles, S. (2004). “Migration, citizenship, and education,” in Diversity and Citizenship Education: Global Perspectives, ed. J. A. Banks (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 17–48.

Chaiklin, S., and Lave, J. (1993). Understanding Practice: Perspectives on Activity and Context. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Chang, M. (2002). Preservation or transformation: where’s the real educational discourse on diversity? Rev. High. Ed. 25, 125–140. doi:10.1353/rhe.2002.0003

Chesler, M. A., and Crowfoot, J. (1989). Racism in Higher Education: An Organizational Analysis. Ann Harbor, MI: Center for Research on Social Organization.

Clotfelter, C. T. (2004). After Brown: The Rise and Retreat of School Desegregation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Coia, L., and Taylor, M. (2009). “Co/autoethnogrpahy: exploring our teaching selves collaboratively,” in Research Methods for the Self-Study of Practice: Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices, eds D. L. Tidwell, M. Heston, and L. Fitzgerald (Netherlands: Springer), 3–16.

Dowd, A. C. (2008). The community college as gateway and gatekeeper: moving beyond the access “saga” to outcome equity. Harv. Educ. Rev. 77, 407–419. doi:10.17763/haer.77.4.1233g31741157227

Dowd, A. C., and Bensimon, E. M. (2015). Engaging the ‘Race Question’: Accountability and Equity in U.S. Higher Education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Dowd, A. C., and Tong, V. P. (2007). “Accountability, assessment, and the scholarship of “best practice”,” in Handbook of Higher Education, Vol. 22, ed. J. C. Smart (New York, NY: Springer), 57–119.

Education Testing Service. (2015). Guide to the Use of Scores. Available at: http://www.ets.org/s/gre/pdf/gre_guide.pdf

Educational Testing Service. (2009). News on Research, Products, and Solutions for Learning and Education. Available at: http://www.ets.org/Media/News_and_Media/pdf/innovations_spring2009.pdf

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. J. Educ. Work 1, 133–156. doi:10.1080/13639080020028747

Engeström, Y. (2009). “Expansive learning: toward an activity-reconceptualization,” in Contemporary Learning Theories, ed. K. Illeris (New York, NY: Routledge), 53–73.

Espeland, W. N., and Sauder, M. (2007). Rankings and reactivity: how public measures recreate social worlds. Am. J. Sociol. 113, 1–40. doi:10.1086/517897

Frankenberg, E., and Orfield, G. (2012). The Resegregation of Suburban Schools: A Hidden Crisis in American Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Gates Millennium Scholars. (2016). Gates Millennium Scholars Program. Available at: https://scholarships.gmsp.org/Program/Details/7123dfc6-da55-44b7-a900-0c08ba1ac35c

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research and Practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gillborn, D. (2005). Education policy as an act of white supremacy: whiteness, critical race theory, and education reform. J. Educ. Policy 20, 485–505. doi:10.1080/02680930500132346

Gorski, P. C., and Landsman, J. (2013). The Poverty and Education Reader: A Call for Equity in Many Voices. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Greenwood, D. J., and Levin, M. (2005). “Reform of the social sciences and of universities through action research,” in Handbook of Qualitative Research, eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 43–46.

Grutter v. Bollinger. (2003). 288 F, 3d 732(6th Cir.) Available at: https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/02-241.ZO.html

Guinier, L. (2003). Admissions rituals as political acts: guardians at the gates of our democratic ideals. Harv. Law Rev. 117, 1–315.

Guinier, L., and Torres, G. (2003). The Miner’s Canary: Enlisting Race, Resisting Power, and Transforming Democracy. Cambridge, MA: First Harvard University Press.

Haney-Lopez, I. (2006). White by Law: The Legal Construction of Race. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Haney-Lopez, I. F. (2010). Is the “post” in post-racial the “blind” in colorblind? Cardozo Law Rev. 32, 807–831.

Hardigan, P. C., Lai, L. L., Arneson, D., and Robeson, A. (2001). Significance of academic merit, test scores, interviews, and the admissions process: a case study. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 65, 40–44.

Harper, S. R. (2012). Black Male Student Success in Higher Education: A Report from the National Black Male Achievement Study. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania.

Harper, S. R., and Hurtado, S. (2011). “Nine themes in racial campus climates and implications for implications for institutional transformation,” in Race and Ethnic Diversity in Higher Education, eds S. R. Harper and S. Hurtado (Boston, MA: Pearson), 204–216.

Howard, T. C. (2003). Culturally relevant pedagogy: ingredients for critical teacher reflection. Theory Pract. 42, 195–202. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4203_5

Jencks, C., and Mayer, E. (1990). “The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood,” in Inner-City Poverty in the United States, eds L. E. Lynn and M. F. H. McGeary (Washington, DC: National Academy Press), 111–186.

Jencks, C., and Phillips, M. (1998). The Black-White Test Score Gap. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Kim, C., Losen, D., and Hewitt, D. (2010). The School-to-Prison Pipeline: Structuring Legal Reform. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Klitgaard, R. (1985). Choosing Elites: Selecting the “Best and Brightest” at Top Universities and Elsewhere. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Kozol, J. (2006). The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America. New York, NY: Crown.

Ladson-Billings, G. J. (2005). From the Achievement Gap to the Education Debt: Understanding Achievement in U.S. Schools. San Francisco, CA: Presidential address at the American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting.

Lamont, M. (2009). How Professors Think: Inside the Curious World of Academic Judgment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

McNamara Horvat, E., and O’Connor, C. (2005). Beyond Acting White: Reframing the Debate on Black Student Achievement. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Micceri, T. (2002). Evidence Suggesting We Should Admit Students Who Score Extremely Low on GRE Subsets or the GMAT to Graduate School Programs. Paper Presented at Meeting of the Association for Institutional Research, Toronto, Canada.

Milem, J., Mitchell, C., and Anthony, A. (2005). Making Diversity Work on Campus: A Research-Based Perspective. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Milner, R. H. (2015). Rac(e)ing to Class: Confronting Poverty and Race in Schools and Classrooms. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Murrell, P. (2002). African-centered pedagogy: developing schools of achievement for African-American children. J. Black Stud. 34, 386–401.

Nasir, N. S., and Hand, V. M. (2006). Exploring sociocultural perspectives on race, culture, and learning. Rev. Educ. Res. 76, 449–475. doi:10.3102/00346543076004449

National Center for Educational Statistics. (2015a). Racial/Ethnic Enrollment in Public Schools. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cge.asp

National Center for Educational Statistics. (2015b). Children Living in Poverty. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cce.asp

National Center for Educational Statistics. (2015c). Characteristics of Postsecondary Students. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_csb.asp

National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowships. (2016). NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program. Available at: http://www.nsf.gov/funding/pgm_summ.jsp?pims_id=6201

Nieto, S. (1999). The Light in Their Eyes: Creating Multicultural Learning Communities. New York: Teachers College Press.

Nieto, S. (2000). Affirming Diversity: The Sociopolitical Context of Multicultural Education, 3rd Edn. White Plains, NY: Longman.

Noddings, N. (1999). “Care, justice, and equity,” in Justice and Caring: The Search for Common Ground in Education, eds M. S. Katz, N. Noddings, and K. A. Strike (New York, NY: Teachers College Press), 7–20.

Orfield, G. (2001). Diversity Challenged: Legal Crisis and New Evidence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Publishing Group.

Orfield, G., Bachmeier, M. D., James, D. R., and Eitle, T. (1997). Deepening segregation in American public schools: a special report from the Harvard Project on school desegregation. Equity Excell. Educ. 30, 5–24. doi:10.1080/1066568970300202

Orfield, G., Frankenberg, E., Ee, E., and Kuscera, J. (2014). Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future. Los Angeles, CA: The Civil Rights Project. Available at: https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/brown-at-60-great-progress-a-long-retreat-and-an-uncertain-future/Brown-at-60-051814.pdf

Orfield, G., and Yun, J. T. (1999). Resegregation in American Schools. Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project/Harvard University.

Osanloo, A., and Reyes, L. (2013). “Hispanic-serving institutions,” in Multicultural America, Vol. 2, eds C. Cortes and G. Golson (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 1083–1086.

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: a needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educ. Res. 41, 93–97. doi:10.3102/0013189X12441244

Perna, L. W., and Finney, J. E. (2014). The Attainment Agenda: State Policy Leadership in Higher Education. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

Posselt, J. R. (2014). Toward inclusive excellence in graduate education: constructing merit and diversity in PhD admissions. Am. J. Educ. 120, 481–514. doi:10.1086/676910

Rodriguez, A. J. (2013). “Epilogue: moving the equity agenda forward requires transformative action,” in Moving the Equity Agenda Forward: Equity Research, Practice and Policy in Science Education, eds J. A. Bianchini, V. L. Akerson, A. C. Barton, O. Lee, and A. J. Rodriguez (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer), 355–363.

Sedlacek, W. E. (2004). Beyond the Big Test: Noncognitive Assessment in Higher Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Seo, M. G., and Creed, W. E. D. (2002). Institutional contradictions, praxis, and institutional change: a dialectical perspective. Acad. Manage. Rev. 27, 222–247. doi:10.5465/AMR.2002.6588004

Stanton-Salazar, R. D. (2001). Manufacturing Hope and Despair: The School and Kin Support Networks of U.S. Mexican Youth. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Sternberg, R., and Williams, W. (1997). Does the graduate record examination predict meaningful success in the graduate training of psychologists? A case study. Am. Psychol. 52, 630–641. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.630

Stevens, M. (2008). Creating a Class: College Admissions and the Education of Elites. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Teranishi, R., and Briscoe, K. (2006). “Social capital and racial stratification in higher education,” in Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, eds J. C. Smart and M. B. Paulsen (New York, NY: Springer), 591–614.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2013). Selected Social Characteristics in the United States: 2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. Available at: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

Valencia, R. (2010). Dismantling Contemporary Deficit Thinking: Educational Thoughts and Practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

Wechsler, H. S. (1977). The Qualified Student: A History of Selective College Admission in America. New York, NY: Wiley.

Wells, A. S. (2014). Seeing Past the “Colorblind” Myth of Education Policy: Addressing Racial and Ethnic Inequality and Supporting Culturally Diverse Schools. Boulder, CO: University of Boulder, National Education Policy Center, 1–30.

Keywords: graduate admissions, educational leadership, inclusive education, social justice and equity, leadership preparation

Citation: Boske C, Elue C, Osanloo AF and Newcomb WS (2018) Promoting Inclusive Holistic Graduate Admissions in Educational Leadership Preparation Programs. Front. Educ. 3:17. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00017

Received: 13 October 2017; Accepted: 19 February 2018;

Published: 05 April 2018

Edited by:

Paula A. Cordeiro, University of San Diego, United StatesReviewed by:

Corinne Brion, University of San Diego, United StatesHeather Lattimer, University of San Diego, United States

Margaret Grogan, Chapman University, United States

Copyright: © 2018 Boske, Elue, Osanloo and Newcomb. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Whitney Sherman Newcomb, d3NuZXdjb21iQHZjdS5lZHU=

Christa Boske

Christa Boske Chinasa Elue

Chinasa Elue Azadeh Farrah Osanloo

Azadeh Farrah Osanloo Whitney Sherman Newcomb

Whitney Sherman Newcomb