- 1Kaye Academic College of Education, Beer-Sheva, Israel

- 2Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan, Israel

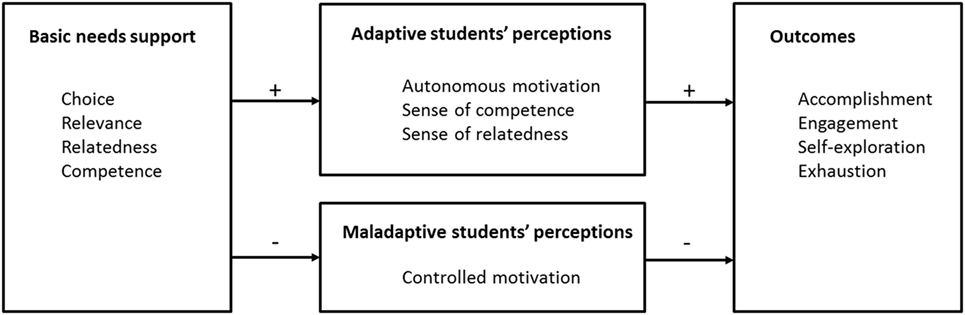

The study employed a self-determination theory (SDT) framework to explore pre-service teachers’ perceptions of their professional training in relation to motivational outcomes. We hypothesized that students’ perceptions of basic psychological need support will be positively associated with their sense of relatedness, competence, and autonomous motivation and negatively associated with controlled motivation. Sense of relatedness, competence, and autonomous motivation were hypothesized to be positively associated with personal accomplishment, engagement, and self-exploration and negatively associated with emotional exhaustion. The study was conducted within a multicultural context, which enabled exploration of the hypotheses among students from two different cultural backgrounds. Based on the universality of SDT, we expected that the general models would be similar for both cultures, although some mean level and correlational paths may be different. The sample (N = 308; mean age 23.4) consisted of Muslim Arab-Bedouin (55.3%) and Jewish (44.7%) pre-service teachers enrolled in the same teachers’ college in Israel. The participants completed self-report surveys assessing their sense of basic psychological need support, autonomous and controlled motivation, self-accomplishment, engagement, self-exploration, and emotional exhaustion. Multiple-group structural equation modeling revealed that need support contributed positively to autonomous motivation, sense of relatedness, and sense of competence in both cultures. Autonomous motivation contributed positively to sense of self-accomplishment, engagement, and self-exploration. Competence in turn was positively related to engagement and negatively related to emotional exhaustion, and relatedness was associated with engagement only among the Bedouin students, and with self-accomplishment only among the Jewish students. These results indicate that sense of need support is highly important regardless of cultural background, while sense of relatedness may be related to different outcomes across cultures. The findings demonstrate the utility of SDT within the context of multicultural teacher training and support the universality of the theoretical framework.

Introduction

For several decades, policymakers and educators around the world have been engaging with issues such as the professional status of teachers, quality of teaching, teacher dropout, and shortage of teachers (Gao and Trent, 2009; Struyven et al., 2013; Weissblei, 2013). Various studies indicate rates of up to 30–50% in teacher dropout in the first 5 years of teaching (State of Israel, Central Bureau of Statistics, 2015; The European Commission Staff Working Document-SEC, 2010). Efforts to address the situation have led to various educational reforms designed to improve the status of teachers and the quality of teaching (Kfir and Ariav, 2008).

Some of the problems can be solved at policymaker level. However, issues such as teacher dropout or teaching quality can be discussed from a different perspective, namely the motivational perspective (Watt and Richardson, 2007).

Previous studies indicate that pre-service teachers report multiple reasons for choosing teaching (e.g., Watt and Richardson, 2007; Kaplan and Madjar, 2013). Some studies indicate that pre-service teachers’ initial motivation to teach at the beginning of their studies is associated with various outcomes during their early teaching career, such as dropout rates (Jungert et al., 2014) or their intentions to stay in the teaching profession (Watt and Richardson, 2007).

Despite some early studies (i.e., Ames and Ames, 1984; Pelletier et al., 2002), the topic of teachers’ motivation is a relatively new field of research (Richardson et al., 2014; Katz and Shahar, 2015). The major focus of the research was mainly on the antecedents and outcomes of students’ motivation (Roth, 2014), and “there was almost no systemic, theory-driven research on teacher motivation” (Batler, 2014, p. 20). This topic began to attract research attention only in recent years, especially with reference to in-service teachers. Teachers’ motivation has been explored using various theoretical frameworks, such as Achievement Goal Theory (Batler, 2014) and Expectancy-Value Theory (Richardson and Watt, 2014), while this study will employ self-determination theory (i.e., SDT; e.g., Deci and Ryan, 2000; Roth et al., 2007; Roth, 2014). Yet, the connection between the motivation of teachers in general and pre-service teachers in particular, and the quality of their training and professional performance is a subject that has been insufficiently explored.

In light of the need to deepen understanding of the possible connections between teachers’ motivation and students’ motivation, we chose SDT as a leading theoretical framework that can deepen our understanding of the psychological mechanisms that explain these connections. SDT focuses on the effects of psychological need support and the outcomes of an experience of need support, and consequently it is suited to this area of research.

We embark from the premise that in-depth understanding of the emotional–motivational processes of pre-service teachers can lead to intervention programs for improving the quality of teaching (Anderman and Leake, 2005).

Based on SDT, this study examined the required conditions for promoting psychological need satisfaction, autonomous motivation, and various motivational outcomes in pre-service teachers. The study compared pre-service teachers from different cultural backgrounds—individualistic and collectivistic (will be elaborated in a separate section). It also enabled an examination of the applicability of SDT to teacher education. In both areas, there is a paucity of research.

The theoretical background will begin with a brief presentation of SDT with emphasis on its applicability to the education system. We shall highlight the perspective of the students, which has been extensively researched. Then, we shall present motivation for teaching from the perspective of teachers, first of in-service teachers, and then we shall focus on pre-service teachers. We shall conclude the introduction with a brief overview of the hypothesized outcome factors that were included in the study.

Self-determination Theory

Self-determination theory is a motivational theory (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2000, 2002, 2017), which posits that people have basic psychological needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence. Fulfillment of psychological needs is essential for people’s psychological health and growth, autonomous motivation, optimal functioning, and self-actualization (Deci and Ryan, 2008). The need for relatedness is the individual’s aspiration to maintain close, safe, and satisfying connections in his/her social environment and feel part of it. The need for competence is the individual’s need to experience himself or herself as capable of realizing abilities, plans, and aims, which are not always easy to achieve, and feel a sense of efficacy. The need for autonomy is the need for self-determination, meaning, and freedom of choice (Deci and Ryan, 2000). This is the individual’s striving to realize and to actively and exploratively form authentic and direction-giving values, goals, interests, and abilities, i.e., to construct his/her identity (Reeve and Assor, 2011; Assor, 2012).

Self-determination theory draws a distinction between controlled and autonomous motivation (Deci and Ryan, 2000). Controlled motivation comprises types of motivation typified by low levels of self-determination: (1) extrinsic motivation, wherein the individual acts out of external pressure, out of hope for material reward, or a desire to avoid punishment; (2) introjected motivation, wherein the individual acts out of internal pressure, out of a desire to gain appreciation, or avoid rejection and feelings of guilt or shame.

Autonomous motivation comprises types of motivation typified by high levels of self-determination: (1) identified motivation, wherein the individual acts out of identification with the value or behavior, and recognition of the importance of the activity, or understanding of its connection with his/her goals; (2) intrinsic motivation, wherein the individual performs the activity for the satisfaction inherent in the activity itself. This is the archetype of inherent self-determined activity that is not the outcome of internalization; (3) integrative motivation. According to SDT, behaviors stemming from controlled motivations can become self-determined through an internalization process, an active process wherein beliefs, values, behaviors, and even demands that were originally motivated by extrinsic motivation become an integrative part of the self (Deci and Ryan, 2000). This is an identity-formation process, which is a meaningful process in teacher education, especially in light of current knowledge whereby some teachers act out of controlled motivation (Kaplan and Madjar, 2013; Richardson et al., 2014).

A large body of research indicates the advantages of autonomous over controlled motivation for the individual’s optimal functioning in various domains, such as learning (Assor et al., 2002), health (Williams and Deci, 1996), and environmental education (Kaplan and Madjar, 2015).

Self-determination theory emphasizes the role of teachers’ support for students’ needs (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Assor et al., 2002; Reeve, 2006). Relatedness support includes teacher behaviors, such as expressing affection, devoting time and resources, willingness to help, and a non-competitive learning structure. Competence support is typified by teacher behaviors such as providing optimal challenges, immediate and non-evaluative feedback, and assistance in coping with failure (Connell, 1990). Autonomy support includes teacher behaviors such as absence of coercion, giving opportunities to choose, clarifying the relevance of the studied material, enabling expression of negative emotions, encouraging personal initiatives, and recognition of the students’ perspective (Assor et al., 2002; Reeve, 2006). Two aspects of autonomy support were included in this study: providing choice and fostering relevancy. These behaviors were identified in previous studies as autonomy-supportive behaviors (Kaplan and Assor, 2001; Assor et al., 2002). Providing choice is a teacher behavior that enables students to choose tasks that are interesting or important to them. Fostering relevancy helps students to experience the learning process as promoting their needs, goals, and values and to perceive the teacher as understanding their feelings and thoughts (Kaplan and Assor, 2001).

Research shows that in response to need support, students experience higher autonomous motivation and less controlled motivation, positive emotionality, sense of competence and relatedness, optimal emotional and social functioning, greater engagement, better academic performance, and internalization processes (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Assor et al., 2002, 2005; Reeve, 2006, 2013; Feinberg et al., 2008; Kaplan and Assor, 2012; Reeve and Lee, 2014; Jang et al., 2016). The results regarding the positive effects of need-supportive environments have been found in education across all age groups (Deci and Ryan, 2000). Some studies confirm the applicability of SDT to students belonging to the Arab-Bedouin culture as well, a population that is included in this study (Kaplan and Madjar, 2013, 2015; Kaplan et al., 2014; Kaplan, 2016). The next section focuses on teachers’ motivation from an SDT perspective, beginning with in-service teachers followed by pre-service teachers.

SDT Perspective of In-Service Teachers’ Motivation

The large body of SDT-based research that explored the antecedents and outcomes of students’ need satisfaction, focused mainly on teachers’ instruction practices (Assor et al., 2002, 2005; Reeve, 2006) and/or satisfaction of the basic needs of students, not teachers (Hanfstingl et al., 2010; Klassen et al., 2012; Roth, 2014). The paucity of SDT-based research concerning teachers’ need satisfaction and teachers’ autonomous motivation for teaching has attracted the interest of researchers in recent years (Roth, 2014). As a result, there is an increase in studies focusing on teachers’ motivation. For example, need satisfaction and autonomous motivation for teaching were found to be positively associated with sense of personal accomplishment (Roth et al., 2007; Fernet et al., 2008), engagement at work (Jansen in de Wal et al., 2014), teachers’ autonomy-supportive behaviors (Van den Berghe et al., 2014), and others.

Studies on in-service teachers have focused on the school context as supporting or frustrating teachers’ needs, and on the connection between teachers’ need satisfaction and various outcomes regarding teachers’ functioning (e.g., Taylor et al., 2008, 2009; Hanfstingl et al., 2010; Klassen et al., 2012; Van den Berghe et al., 2014; Aelterman et al., 2016).

Various pressures at school, such as demands associated with the curriculum, or pressure exerted on teachers by principals, frustrated teachers’ needs and negatively affected autonomous motivation or enhanced controlled motivation for teaching (e.g., Pelletier et al., 2002; Eyal and Roth, 2011). Students’ behaviors and motivation were also found to affect teachers’ motivation and need-supportive behaviors (e.g., Taylor and Ntoumanis, 2007; Fernet et al., 2012).

For example, Pelletier et al. (2002) found that the more the teachers perceived pressure from above and pressure from below, the less they experienced self-determination toward teaching, which in turn resulted in them being more controlling with their students. Fernet et al. (2012) showed that changes in teachers’ perceptions of classroom overload and students’ disruptive behaviors are negatively related to changes in autonomous motivation, which in turn negatively predict changes in teachers’ emotional exhaustion.

Teachers’ autonomous motivation for teaching has been found to predict their autonomy-supportive behaviors (e.g., Roth et al., 2007; Taylor and Ntoumanis, 2007; Taylor et al., 2008; Lam et al., 2009; Van den Berghe et al., 2014), whereas teachers’ controlled motivation predicted autonomy-suppressive behaviors (e.g., Soenens et al., 2012). For example, Roth et al. (2007) found that teachers’ autonomous motivation for teaching predicted students’ autonomous motivation for learning through students’ perceptions of their teachers’ autonomy-supportive behaviors. We shall now examine the motivation of pre-service teachers, the studied population in this study.

SDT Perspective of Pre-Service Teachers’ Motivation

In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of SDT-based studies on in-service teachers’ motivation to teach. However, research in teacher education frameworks is still sparse (Spittle et al., 2009; Kaplan, 2016). Consequently, this study focuses on the under-researched area regarding pre-service teachers’ need satisfaction and autonomous motivation and outcomes connected to these variables.

There have been a number of laboratory studies or educational interventions aimed at developing and/or examining the characteristics and effects of autonomy-supportive teaching behaviors in pre-service teachers, such as enabling choices, providing rational, enhancing relevancy, and relying on non-controlling language (Reeve, 1998; Reeve et al., 1999; Wang and Liu, 2008; Perlman, 2015).

These studies demonstrate that autonomy-supportive teaching behaviors can be developed in pre-service teachers, and to achieve this, it is important to support their needs. Indeed, autonomy-supportive behaviors led to positive outcomes in students.

For example, Reeve (1998) found that autonomy-supportive behaviors were teachable among pre-service teachers who participated in an intervention program. Perlman (2015) examined the effects of an SDT-based intervention in physical education on pre-service teachers’ instructional behaviors and the motivational responses of their students. The results indicated significant changes in pre-service teachers’ autonomy-supportive behaviors and their students’ perceptions.

Some qualitative studies explored the experience of need satisfaction among pre-service teachers (Evelein et al., 2008; Spittle et al., 2009; Bouwma-Gearhart, 2010). For example, Evelein et al. (2008) demonstrated that need satisfaction strongly influences first-year student teachers’ teaching experiences. Bouwma-Gearhart (2010) presents a case study that documents the struggle one pre-service educator experienced due to the school’s pressures and demands regarding students’ performance in the standardized tests. According to the author, this case demonstrates an experience of autonomy suppression.

In light of the dearth of research in this domain, it seems that there is a need to continue researching the conditions required to promote pre-service teachers’ need satisfaction and autonomous motivation, and the possible outcomes of these motivational experiences in teacher education frameworks. We shall now present the variables regarding pre-service teachers’ motivational outcomes that were included in this study.

Teachers’ Motivational Outcomes

This study examines the effects of supporting the needs of pre-service teachers on various motivational outcomes during their studies. The following variables were included in the study: (a) autonomous motivation and controlled motivation—two variables that examined the type of motivation for studying in a teacher education institution; (b) sense of relatedness and sense of competence—two variables that examined the experience of need satisfaction; (c) personal accomplishment and self-exploration—two variables associated with the developing identity of pre-service teachers; (d) engagement in studying to be a teacher—the behavioral aspect of studying; and (e) sense of emotional exhaustion—the emotional aspect associated with students’ studying.

Based on the previous studies (Watt and Richardson, 2007; Jungert et al., 2014), these variables are likely to be associated with pre-service teachers’ future motivation to teach, and thus merit examination. Since the variables directly connected to motivation have already been presented, we shall now present the other variables that are associated with motivational outcomes of pre-service teachers.

Sense of Personal Accomplishment and Emotional Exhaustion

According to SDT, autonomous motivation is associated with a positive experience of vitality and energy. In contrast, autonomous motivation is associated with a negative experience of emotional exhaustion, which is likely to be associated with controlled motivation (La Guardia et al., 2000).

Sense of personal accomplishment refers to the feeling that teaching enables the individual to fully realize his/her abilities and feel satisfied, vital, and energetic (Friedman and Farber, 1992). According to SDT, underlying an act performed out of a sense of autonomy is authentic self-actualization (Deci and Ryan, 2000). People feel a sense of self-actualization when they are involved in an activity that they experience as stemming from their authentic self (Ryan, 1993).

Teachers’ maladaptive experiences at work might be characterized by feelings of burnout (Van den Berghe et al., 2014). Following Maslach and Jackson (1981), this concept is defined as a syndrome containing three components: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and decreased feelings of personal accomplishment. Emotional exhaustion, the variable used in this study, refers to reduction of energy and depletion of emotional and mental resources. Teachers might feel that they cannot engage properly and intensively at work and might feel stressful and overloaded by school demands (Maslach and Jackson, 1981; Friedman and Farber, 1992; Roth et al., 2007; Van den Berghe et al., 2014).

Need satisfaction and autonomous motivation for teaching were found to be positively associated with sense of personal accomplishment (Roth et al., 2007) and negatively associated with burnout, or specifically with emotional exhaustion (Roth et al., 2007; Fernet et al., 2008, 2012; Eyal and Roth, 2011; Soenens et al., 2012; Van den Berghe et al., 2014).

Engagement

Academic engagement refers to devoting time and effort to learning and includes behavioral, emotional, and cognitive components (Reeve and Tseng, 2011; Jungert et al., 2014). Numerous studies found that sense of need satisfaction and autonomous motivation are associated with students’ engagement in learning (e.g., Assor et al., 2002; Reeve and Tseng, 2011). Studies on teachers have primarily addressed engagement at work (e.g., Klassen et al., 2012), while very few have focused on the academic engagement of pre-service teachers (Jungert et al., 2014). Thus, this aspect is one of the innovations of this study. For example, Jansen in de Wal et al. (2014) found that teachers who were characterized by a high identified and intrinsic motivation profile engaged more in professional development activities in comparison to teachers who were characterized by a low-quality motivation profile.

Self-exploration

An additional variable included in this study is self-exploration. Exploration is one of the main components of the identity-formation process (Grotevant, 1987; Marcia, 1993; Flum and Kaplan, 2006). Exploration of one’s potentials and commitment to a coherent set of values, goals, and behaviors is important for healthy identity development (La Guardia, 2009). Flum and Kaplan (2006), p. 100, define exploration as “a deliberate internal or external action of seeking and processing information in relation to the self. An outcome of this processing would be the creation of self-relevant meaning with an integrative effect and thus the facilitation of development.”

Self-determination theory explains the optimal conditions for this process by means of the concepts of needs and internalization (La Guardia, 2009). According to SDT, humans have an inherent tendency to explore, assimilate knowledge, and develop new skills. They strive to integrate these new experiences into a coherent sense of self (Deci and Ryan, 2000). These natural propensities can be either supported or undermined by need-supportive environments (La Guardia, 2009). La Guardia (2009), p. 101, claims that “Active exploration of one’s potentials and integration of experiences into a committed set of personally defining and meaningful values, goals, and roles is deemed essential to healthy identity formation.”

A review of the literature found no SDT-based studies referring to pre-service teachers in which this variable was included. Among adolescents, studies found relationships between basic psychological need support and engagement in identity exploration processes (Madjar and Cohen-Malayev, 2013). The basic premise of this study is that supporting psychological needs creates the optimal conditions for processes in which pre-service teachers can perform exploration processes associated with identity-formation processes.

Cultural Context and Teachers’ Motivation

This study was conducted within a multicultural teacher education context. Most of the students enrolled in the college are from two cultural backgrounds: Bedouin (collectivistic culture) or Jewish (mostly individualistic culture). This multicultural picture is typical in colleges of education in Israel (Agbaria, 2013), and it is therefore important to examine whether there are differences in the motivational processes of different cultural groups. An answer to this question will enable interventions to be built that are suited to the different populations and cultures.

The Bedouins in southern Israel are a Muslim Arab minority group (approximately 20% of the population). In recent years, the Bedouins have transitioned rapidly from a traditional society into modern and urban life (Al-Krenawi, 2010). Despite these change processes, Bedouin lifestyle is still characterized by collectivistic cultural orientations compared with Western cultures (Abu-Rabia-Queder and Weiner-Levy, 2010; Al-Krenawi, 2010). Recent findings still support the notion that Arabs in Israel hold more communal and religious attitudes in comparison to the secular Jewish population (Sharabi, 2014).

According to SDT, psychological needs are universal. Although some cultural differences may exist, psychological needs are expected to promote autonomous motivation among various cultural groups (Deci and Ryan, 2000). Thus, students from various cultural groups may differ in their sense of autonomous motivation, but those who perceive greater need support are more likely to report more autonomous motivation within the same context (Chirkov et al., 2003).

Studies have shown that SDT is applicable in traditional collectivistic societies, for example, South Korea (Jang et al., 2009), Japan (Yamauchi and Tanaka, 1998), Turkey (Chirkov et al., 2003), and the Bedouin community (Kaplan et al., 2014). Recent studies have compared students from different cultural backgrounds and revealed that the psychological mechanism that links basic psychological needs and motivation is similar across cultures (Chen et al., 2015; Ginevra et al., 2015).

This Study

This study focuses on the motivation of pre-service teachers from different cultures. The research question is: What are the relationships between pre-service teachers’ perceptions of their instructors’ psychological need support and their sense of need satisfaction (competence, relatedness), autonomous motivation (in contrast with controlled motivation), and various motivational outcomes? The motivational outcomes refer to the behavioral aspect (engagement in studying), the emotional aspect (low level of emotional exhaustion), and aspects expressing the developing identity (self-exploration and self-accomplishment), in addition to sense of need satisfaction and autonomous motivation, which are also motivational outcomes.

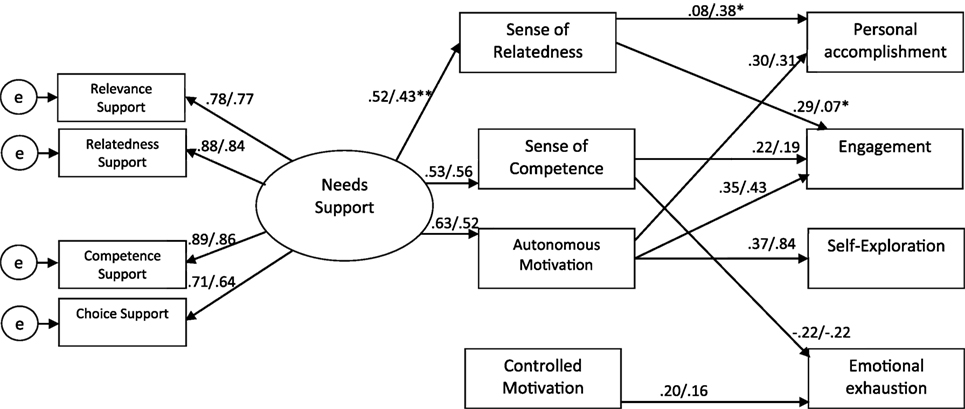

Our hypothesis is that perceived need support will be associated with sense of competence, sense of relatedness, and autonomous motivation for learning at the college, which will in turn predict various motivational outcomes (see Figure 1). More specifically, we expected that need support will be positively associated with sense of relatedness, competence, and autonomous motivation and negatively associated with controlled motivation. In turn, sense of relatedness, competence, and autonomous motivation were hypothesized to be positively associated with personal accomplishment, engagement, and self-exploration and negatively associated with emotional exhaustion. A reverse pattern was expected for controlled motivation. As the universality of SDT has been repeatedly demonstrated in previous research, we hypothesize that these motivational processes will be similar in students from the two cultural groups.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were 308 pre-service teachers (77.3% female; mean age 23.4 SD = 4.92) sampled from a big teacher education college in southern Israel. The college population is multicultural, and socioeconomically and ethnically diverse, including religious and secular Jews and Arab-Bedouins. About 48% of the students studying in the college are Arab-Bedouins. The college specializes in training pre-service teachers for kindergarten, elementary school, and high school with various specialties, such as general sciences, mathematics, arts, sports, special education, Arabic, Hebrew, and English, and the Humanities in 24 annual classes/courses (2 semesters) in various teaching programs and disciplines that represent the college population. The sample included students from Arab-Muslim (Bedouin, 55.3%) and Jewish (44.7%) cultural backgrounds.

Instruments

Teachers’ Psychological Need Support

Perceptions of the instructor’s support for pre-service teachers’ needs were assessed using a scale adapted from Assor et al. (2002). Evidence for the validity of the tool was gathered in various studies (e.g., Roth et al., 2007; Kaplan et al., 2014) and included four aspects of perceived basic need support: (1) providing choice (autonomy support): a 6-item subscale. Sample item: the instructor gives us a choice in course assignments (what to prepare, how, etc.); (2) fostering relevancy (autonomy support): a 6-item subscale. Sample item: the instructor talks to us about the connection between what we are studying and teaching in a school; (3) competence support: a 9-item subscale reflecting various aspects of competence support: giving clear explanations, helping students to manage difficulties, and giving feedback. Sample item: the instructor explains what we need to know or do to succeed in an exam or assignment; and (4) relatedness support: an 8-item subscale. Sample item: the instructor cares about me, and not only in the academic context.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) supported the 4-factor model (χ2 = 556.3, df = 293, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.93, NFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.05). However, these four factors were highly correlated (r’s ranged from 0.50 to 0.73, p’s < 0.001) and therefore modeled as latent variables in the final analysis.

Sense of Basic Need Support

Four subscales of subjective perceptions of autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, sense of relatedness to class, and sense of competence. Evidence for the validity of the tool was gathered in various studies (Assor et al., 2002, 2005; Roth et al., 2007). (1) Autonomous motivation: an 11-item scale; 6 items refer to identified motivation and 5 items refer to intrinsic motivation. Sample item of identified motivation: because it helps me to know things that are important to me. Sample item of intrinsic motivation: because the subjects taught in the course, interest me; (2) controlled motivation: a 13-item scale; 5 items refer to extrinsic motivation and 8 items refer to introjected motivation. Sample item of extrinsic motivation: because I’ll get a good grade in the course if I do what the instructor asks. Sample item of introjected motivation: because I’ll feel guilty if I don’t do what the instructor demands or asks. Both autonomous and controlled motivation scales are based on Ryan and Connell, 1989 and were adapted to pre-service teachers. We examined the four types of motivation: external and introjected (controlled motivation), and identified and intrinsic (autonomous motivation). The various statements begin with: when I invest effort in my studies in this course, I do so because…; (3) sense of relatedness: a 5-item scale. Sample item: there are many students in this class that I’d be happy to meet outside the classroom as well; and (4) sense of competence: a 6-item scale. Sample item: when I decide to study something difficult in this course, I can do it. An additional CFA (χ2 = 579.9, df = 316, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.93, NFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.05) supported the hypothesized 4-factor structure.

Teachers’ Motivational Outcomes

We used four scales: self-exploration, self-accomplishment, engagement, and feelings of exhaustion. (1) Self-exploration: self-exploration refers to a pattern of autonomous learning and is the pre-service teachers’ exploration of and learning about themselves in the context of a specific class (e.g., about their thinking style or their professional development in a specific class). The 3-item scale was developed and validated in previous studies (Kaplan and Assor, 2001; Kaplan et al., 2014). Sample item: I invest in the class to experience a new way of thinking about or observing myself; (2) self-accomplishment and emotional exhaustion: these two scales are based on an abridged version of the scale employed by Friedman and Farber (1992). The self-accomplishment variable expresses satisfaction from teaching and a feeling that teaching enables the realization of one’s abilities. The emotional exhaustion variable expresses feelings of depleted emotional and cognitive resources in learning, and a sense of overload and pressure (Maslach and Jackson, 1981). Evidence for the validity of the tools was gathered in various studies on teachers and the scales were adapted to pre-service teachers (Roth et al., 2007). The self-accomplishment scale included three items. Sample item: I feel that studying teaching gives me great satisfaction. The emotional exhaustion scale included six items. Sample item: I feel that the studies at the college really “burn me out”; and (3) engagement: pre-service teachers’ self-reported engagement in their studies in a particular course. The 5-item scale was validated in a previous study (Assor et al., 2002) and adapted to this study’s population. Sample item: I try to learn as much as possible about the subjects taught in this course.

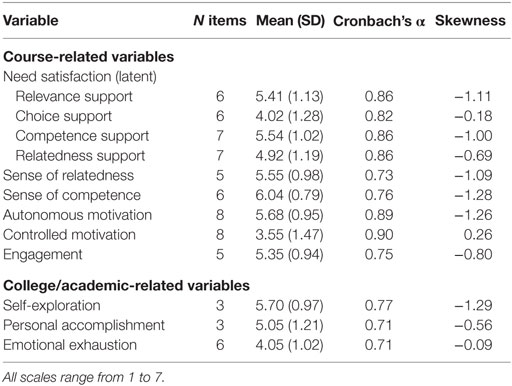

All the items in the various scales range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Measures were calculated as the means of all the items included in each subscale. All the subscales indicated sufficient internal reliability ranging from 71 to 90 (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics).

Procedure

Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. Participants were asked to complete a 25-min survey during class, with reference to the specific course taken at the time of administration. The final data included various 31 courses, with the number of students in each course ranging from 4 to 22.

The courses reflected the various programs (kindergarten, elementary school, and high school) and specializations studied at the college. The questionnaires were administered 4–6 weeks prior to the end of the course, so the participants were already familiar with the course instructors and had formulated their perceptions concerning their experience in the course (thoughts, feelings), the instructors’ behaviors, and their feelings toward them. A trained research assistant administered the questionnaires in one session when the course instructor was not present.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and the internal reliabilities of all the variables included in the study. All the measures yielded adequate internal reliability and psychometric characteristics. For example, students’ autonomous motivation was significantly higher in comparison with controlled motivation [t(307) = 17.15, p < 0.001]. This finding aligns with previous studies commonly indicating that students report higher positive perceptions of motivation and learning contexts in comparison with negative aspects.

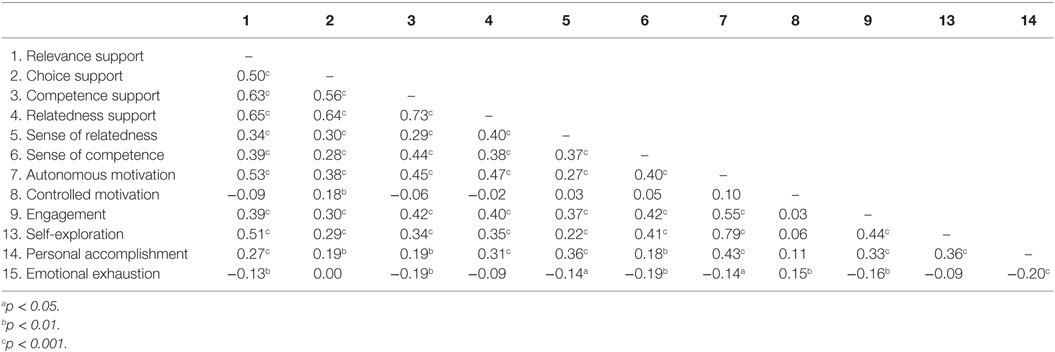

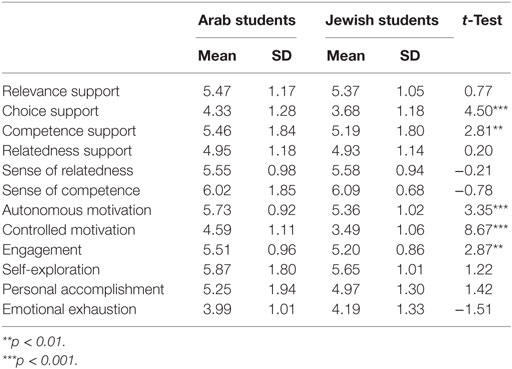

Correlation matrices (Table 2) provided further support for the structural validity of the measurements. For example, autonomous motivation positively correlated with self-accomplishment (r = 0.43, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with emotional exhaustion (r = −0.14, p < 0.05); controlled motivation was not associated with self-accomplishment (r = 0.11, p = ns), and positively correlated with emotional exhaustion (r = 0.15, p < 0.01). Course-related engagement positively correlated with sense of relatedness to class and sense of competence (r = 0.37, p < 0.001; r = 0.42, p < 0.001, respectively), negatively correlated with emotional exhaustion (r = −0.16, p < 0.01), and had no significant correlation with controlled motivation. Mean-level comparisons between cultural groups revealed that Arab and Jewish students reported similar levels for most of the variables included in the study, with the exception of choice support, competence support, autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, and engagement, in which Arab students reported significantly higher mean levels (see Table 3).

Primary Analyses

Multiple-group path analysis was utilized as the primary method for data analysis, based on structural equation modeling using AMOS20. We compared the hypothesized model between two sociocultural groups, namely Arab and Jewish students. Latent variables capturing perceptions of course basic need satisfaction included support for relevance, support for choice, support for competence, and support for relatedness. Perceptions regarding basic need support were hypothesized to predict autonomous and controlled motivations, sense of competence, and sense of relatedness in class; these structures in turn led to sense of self-actualization, engagement in class, self-exploration, and emotional exhaustion (see Figure 2). Model fit indexes generally supported the hypothesized model (CMIN/df = 1.82, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.05). When comparing the two sociocultural groups, measurements weights were not significantly different from the unconstrained model [Δχ2(6) = 12.6, p = ns], whereas measurement intercepts and structural weight were significantly different [Δχ2(13) = 71.1, p < 0.001; Δχ2(22) = 82.2, p < 0.001, respectively]. Therefore, we shall report the results in which the measurement weights were constrained to be identical between groups.

Figure 2. Class-specific path analysis results. Numbers represent Arab/Jewish populations’ coefficients. * indicates significant differences between coefficients. All paths presented are significant at p < 0.05 for at least one population; non-significant paths were removed and constrained to 0.

The findings from the structural equation analysis aligned with our hypotheses. Student engagement in learning was mostly explained by the variables included in the model, with explained variances ranging from 29 to 43% (see Figure 2 for a detailed description of the model). Autonomous motivation and sense of competence were positively associated in both sociocultural populations, whereas sense of relatedness was significant in Arab students. Self-exploration was positively and significantly associated with autonomous motivation for both populations. The self-actualization variance was significantly and positively explained by autonomous motivation in both sociocultural populations, whereas it was positively explained by sense of relatedness only among Jewish students. Emotional exhaustion was positively associated with controlled motivation and negatively associated with sense of competence, with no differences between the populations.

To explore the cultural difference in the strength of the association between the variables in the model (i.e., coefficients) we conducted further analysis, in which each coefficient was constrained to be identical between cultures, compared with the model in which measurement weights were constrained to be equal. The coefficient of sense of relatedness and engagement was significantly different between Arab and Jewish students [Δχ2(1) = 6.51, p < 0.05], indicating that for Arab students sense of relatedness explained significantly more variance in self-reported engagement in class. On the other hand, sense of relatedness explained significantly more variance in self-actualization for Jewish students [Δχ2(1) = 3.84, p < 0.05].

Discussion

The study examined the relationships between pre-service teachers’ perceptions of their need support and satisfaction of their needs for competence and relatedness, autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, and the contribution of those variables to personal accomplishment, engagement, self-exploration, and emotional exhaustion.

The results generally supported the model suggested by SDT (Deci and Ryan, 2000) in both cultural groups included in the study. Pre-service teachers’ need support contributed uniquely and positively to autonomous motivation, sense of relatedness, and sense of competence, that in turn contributed to the additional motivational outcomes. Autonomous motivation contributed positively to sense of self-accomplishment, engagement, and self-exploration. Sense of relatedness contributed positively to sense of self-accomplishment and engagement, while sense of competence contributed positively to engagement and negatively to emotional exhaustion. Sense of need support was not found to be associated with controlled motivation, but controlled motivation positively correlated with emotional exhaustion.

From the cultural perspective, significant differences between the two cultural groups were found in only two of all the possible relationships. The relationship between sense of relatedness and self-accomplishment was found to be stronger in the Jewish pre-service teachers, whereas the relationship between sense of relatedness and engagement in learning was found to be stronger in the Bedouin pre-service teachers.

The findings are consistent with those previous studies that focused on the importance of need support for promoting positive motivational outcomes in teachers (e.g., Roth et al., 2007; Taylor and Ntoumanis, 2007; Fernet et al., 2012; Van den Berghe et al., 2014).

The Importance of Promoting Need Satisfaction and Autonomous Motivation in Teacher Education

We opened the article by indicating the important role played by teacher education institutions in developing professional and quality teachers, especially in light of the present crisis in this area (Kfir and Ariav, 2008). This study highlights one important domain in which this task can be accomplished, namely the motivation domain. Specifically, the study stresses the importance of creating a psychological need-supportive environment for pre-service teachers as a means to improve the quality of teaching. In light of the dearth of SDT-based research regarding pre service teachers’ motivation, the results of this study are important.

Hattie (2003) refers to the major dimensions of excellent teachers, such as having deeper representations about teaching and learning, having the required knowledge about the curriculum, teaching strategies and methods, and more. Besides these abilities, Hattie claims that expert teachers are proficient at creating an optimal classroom climate for learning, attending to their students’ affective attributes, encouraging students’ involvement, giving feedback, respecting the students as learners, and demonstrating care and receptiveness to their students’ needs. According to SDT, these are need-supportive behaviors. SDT deepens our understanding of the students’ psychological needs and ways to support them. In addition, according to SDT, it is important for a quality teacher to be equipped with motivational resources, such as autonomous motivation for teaching, sense of professional self-fulfillment, and ability for exploration on teaching, aspects that previous studies found to be associated with students’ optimal learning experience, such as autonomous motivation for learning. Roth et al. (2007) found that teachers’ autonomous motivation for teaching predicted students’ autonomous motivation for learning and were mediated by teacher behaviors that support students’ autonomy. In other words, autonomously motivated teachers are more supportive of their students’ autonomy, and thus their teaching is of higher quality, according to Hattie.

There are additional reasons why it is important for colleges of education to create a need-supportive environment for the students. Studies focusing on the choice of teaching as a career found that the most prevalent reasons for choosing teaching are autonomous, but teachers choose to engage in teaching for extrinsic reasons as well (e.g., Watt and Richardson, 2007). In addition, studies have shown differences between societies as well; in developing countries, for example, extrinsic reasons are more prevalent than intrinsic or altruistic reasons (Mwamwenda, 2010). Thus, in teacher education institutions, we might find pre-service teachers with various motivations.

Two important tasks emerge from this picture for teacher education institutions. First, to preserve the positive intrinsic motivation to study, with which a considerable proportion of pre-service teachers arrive, and second, to create the conditions to facilitate internalization processes of the teaching profession, so that the extrinsic motivations typifying some pre-service teachers become intrinsic. These processes are associated with teachers’ professional identity (La Guardia, 2009). The key to these processes, according to SDT, is a psychological need-supportive environment (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2017).

While the length of various teacher education programs may change, this is still a sufficient length of time to promote internalization processes in an optimal environment. Pre-service teachers who experience their studies negatively might develop controlled motivation for teaching attended by negative emotions and feelings of emotional exhaustion, as this study found. They may decide to drop out of their studies or go on to teach out of controlled motivation. The negative implications of controlled motivation regarding teachers’ well-being, their quality of teaching, and consequently their negative effects on students’ functioning—are well known (Fernet et al., 2008; Eyal and Roth, 2011; Vansteenkiste and Ryan, 2013).

Some of this study’s findings allude to processes associated with pre-service teachers’ identity formation: their autonomous motivation contributed positively to sense of self-accomplishment and self-exploration. The literature on teacher education indicates the importance of identity in a teacher’s professional development process (Beauchamp and Thomas, 2009). The results of this study support the SDT notion that basic needs are the essential constituents for identity development, even though the study is cross-cultural in nature (Ryan and Deci, 2000; La Guardia, 2009).

The Findings from a Cultural Perspective

The findings of this study support the SDT model in both cultural groups that participated in the study. The few differences found are associated with the strength of the connection between some of the dependent variables and sense of relatedness.

The findings support the SDT argument whereby psychological needs are universal, i.e., they are innate, not acquired, and will be manifested across all cultures and at all developmental stages. SDT researchers do agree, however, that the ways in which autonomy is supported and experienced differ as a function of cultural differences, but their core essence will remain the same (Deci and Ryan, 2008).

It seems that cultural characteristics moderate the connection between sense of relatedness and educational outcomes. Differences in degree of collectivism may explain this moderation: whereas a collectivistic society encourages individuals to conform to society (Triandis, 1999), heightened sense of relatedness improves levels of engagement in learning, but not necessarily levels of more personal self-fulfillment. In contrast, in an individualistic society, sense of relatedness can serve as a better foundation for self-fulfillment, but not necessarily for level of engagement in learning. Consequently, cultural characteristics that can affect the strength of connections between the model’s various components need to be taken into account. Basic psychological need support is important for pre-service teachers in all cultures, but at times the different components will lead to somewhat different outcomes.

The findings of this study do not support the arguments of researchers who adopt a cultural relativism approach, whereby autonomy does not play an important role in the lives of people living in traditional-oriental cultures that emphasize conformity, obedience, social harmony, and mutual dependence within the family and not values of individuality (Triandis, 1999; Iyengar and DeVoe, 2003). The findings join those previous studies confirming the importance of the need for autonomy in different societies, such as South Korea, Russia, United States, Turkey (Chirkov et al., 2003; Jang et al., 2009), and Bedouin society (Kaplan et al., 2014).

Recommendations for Teacher Education Institutions

This study indicates the importance of creating optimal conditions for pre-service teachers’ need support. We suggest that SDT serve as a guiding perception for teaching–learning processes in teacher education institutions.

It is important that the SDT approach be adopted in an autonomy-supportive way, rather than dictated from above by policymakers. Therefore, at the beginning of the process, it is important to enable an open dialog regarding teacher educators’ professional beliefs and the guiding values in the teacher education institution. For example, what are their conceptions regarding the value of autonomy in teacher education and the use of autonomy-supportive vs. controlling methods with student teachers and school students. Based on this preliminary dialog, we recommend jointly formulating the teacher education institution’s guiding educational perception, based on studying research findings and theoretical articles, and then embarking on the construction of SDT-based teaching methods.

In the next stage, a parallel process can be carried out with pre-service teachers. At the start of the process, it is important to hold a dialog with pre-service teachers and help them to clarify their beliefs concerning learning and teaching, and their perceptions regarding promoting autonomy and self-determination in learners. This should be followed by a discussion with them on ways of incorporating psychological need support in their teaching.

Self-determination theory teaching principles should be incorporated into this dialog (Kaplan and Assor, 2012), e.g., providing the rationale, connecting pre-service teachers to past experience that guides their perceptions, and so forth. A dialog of this kind is likely to support the pre-service teachers’ exploration processes, which are essential for their identity formation (La Guardia, 2009; Roth, 2014). Assor (2012) terms this autonomy-supportive process “Supporting Value/Goal/Interest Examination.” In this context, pre-service teachers will be encouraged to engage in discussions or experiences that enable them to conduct in-depth critical reflection, examine their aims and values, and formulate their educational-ideological worldview.

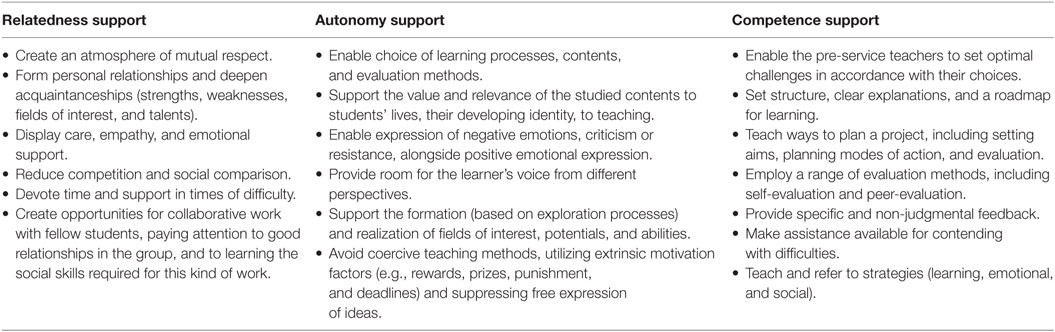

Self-determination theory instructional principles can be divided into three subcore practices: autonomy support, competence support, and relatedness support, each of which contains more specific practices. Based on this study and previous studies (e.g., Assor et al., 2002; Reeve, 2006; Reeve and Halusic, 2009; Jang et al., 2010; Kaplan and Assor, 2012), in Table 4, we recommend ideas for specific SDT-based subcore practices.

Traditional classrooms are likely to reduce the possibilities of giving students autonomy (Rogat et al., 2014). Therefore, our recommendation is to incorporate the suggestions for need support by means of teaching methods that break the traditional structure of specific subjects and contents, connect different disciplines, which are based on personal interests and asking questions, and enable working in groups, collaborative work, inquiry-based learning, and so forth. In other words, to expand the opportunities given to pre-service teachers to realize their autonomy and to be self-determined. An example of this kind of method is project-based learning (Summers and Dickinson, 2012).

It seems that a need-supportive learning environment in teacher education means greater personalization of learning and instruction (Keefe and Jenkins, 2000). This requires changing the instructor’s role to consultant and coach instead of the traditional role of knowledge transference.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. First, we relied on self-report instruments in the assessment of the various variables. Although self-report measures may provide a valid estimation of personal traits (Paunonen and O’Neill, 2010), and self-perceptions of the contextual factors serve as the proximal predictor in students’ engagement (e.g., Kaplan et al., 2002), it may be informative to use observation methods to assess actual support for pre-service teachers’ needs by their instructors. For example, the observation instruments developed by Reeve et al. (2004) or reports written by the college instructors (e.g., regarding students’ engagement). Second, the vast majority of the participants were female pre-service teachers. While this is a representative proportion of the teacher population, future studies could include more male pre-service teachers to enable more thorough inspection of gender-related interactions. Finally, the study is based on cross-sectional data. We examined alternative models using rigorous path analysis methods that exclude some of the other potential explanations (Byrne, 2013). Further research should explore these relationships over time to establish causal relationships between instructors’ practices and pre-service teachers’ perceptions and outcomes. Yet, these findings are essential to support the rationale for initiating research that is focused on the factors that were included in this study.

This study focuses on pre-service teachers’ motivation. If we wish to bring about change in teaching quality, it is of paramount importance to begin in the first circle, namely teacher educators. Future studies can focus on the motivation of teacher educators in a teacher education institution and examine the connections between teacher educators’ beliefs concerning pre-service teachers’ motivation and autonomy, their motivation type for teaching at a teacher education institution, and various outcomes in pre-service teachers. It may be assumed that different motivational profiles will be found among teacher educators as well. For some, teaching at a teacher education institution might be a fallback career. Future studies can also focus on motivational processes that bring about change in pre-service teachers’ initial motivations, e.g., a longitudinal study to examine how the need-suppressive behaviors of college lecturers influence different outcomes over time, such as autonomous motivation changing into controlled motivation, or alternatively, how need support leads to controlled motivation changing into autonomous motivation.

Summary

This study focuses on an issue that is important to policymakers in the field of teacher education, namely how to train quality teachers with autonomous motivation for teaching. The study demonstrates that supporting pre-service teachers’ basic needs is a key to promoting teaching quality. Thus, the pre-service teachers who participated in this study and experienced support for their needs expressed autonomous motivation, sense of competence and relatedness, engaged more in teaching, and experienced less negative emotions. This optimal environment was also found to facilitate identity-formation processes. Based on the findings of this and additional studies, it may be concluded that autonomous motivation for teaching can be considered an adaptive motivation that is associated with the quality of teacher training programs, the quality of pre-service teachers’ learning in the course of their studies, as well as the quality of teaching in practice (Bruinsma and Jansen, 2010).

Thus, if policymakers aim to improve the quality of future teachers, they need to pay attention to the establishment of an optimal learning environment in teacher education institutions (as well as in schools). Some ideas on how to achieve this are presented in the article.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of American Psychological Association (APA) ethical guidelines and was approved by Kaye Academic College of Education IRB.

Author Contributions

HK: substantial contributions to conception and research design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article and then revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. NM: substantial contributions to conception and research design, and analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article; final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Abu-Rabia-Queder, S., and Weiner-Levy, N. (2010). Palestinian Women in Israel: Identity, Power Relations, and Coping Strategies. Tel Aviv and Jerusalem: Hakibbutz Hameuchad and The Van Leer Jerusalem Institute (Hebrew), 27–48.

Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Van Keer, H., and Haerens, L. (2016). Changing teachers’ beliefs regarding autonomy support and structure: the role of experienced psychological need satisfaction in teacher training. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 23, 64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.10.007

Agbaria, A. K. (2013). “The policy of Arab teacher education in Israel. The claim for national and pedagogical unity,” in Teacher Education in the Palestinian Society in Israel: Institutional Practices and Educational Policy, ed. A. K. Agbaria (Tel Aviv: Resling (Hebrew)), 11–47.

Al-Krenawi, A. (2010). “Women in polygamous families in Arab-Bedouin society in the Negev,” in Palestinian Women in Israel: Identity, Power Relations, and Coping Strategies, eds S. Abu-Rabia-Queder and N. Weiner-Levy (Tel Aviv and Jerusalem: Hakibbutz Hameuchad and The Van Leer Jerusalem Institute (Hebrew)), 105–122.

Ames, C., and Ames, R. (1984). Systems of student and teacher motivation: toward a qualitative definition. J. Educ. Psychol. 76, 535–556. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.76.4.535

Anderman, L. H., and Leake, V. S. (2005). The ABCs of motivation: an alternative framework for teaching preservice teachers about motivation. Clear. House 78, 192–196.

Assor, A. (2012). “Allowing choice and nurturing an inner compass: educational practices supporting students’ need for autonomy,” in Handbook of Research on Student Engagement, eds S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie (New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media, LLC), 421–438.

Assor, A., Kaplan, H., Kanat-Maymon, Y., and Roth, G. (2005). Directly controlling teacher behaviors as predictors of poor motivation and engagement in girls and boys: the role of anger and anxiety. Learn. Instruct. 15, 397–413. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.008

Assor, A., Kaplan, H., and Roth, G. (2002). Choice is good, but relevance is excellent: autonomy-enhancing and suppressing teacher behaviors predicting students’ engagement in schoolwork. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 72, 261–278. doi:10.1348/000709902158883

Batler, R. (2014). “What teachers want to achieve and why it matters: an achievement goal approach to teacher motivation,” in Teacher Motivation: Theory and Practice, eds P. W. Richardson, H. M. G. Watt, and S. A. Karabenick (New York, NY: Routledge), 20–35.

Beauchamp, C., and Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: an overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Camb. J. Educ. 39, 175–189. doi:10.1080/03057640902902252

Bouwma-Gearhart, J. (2010). Pre-service educator attrition informed by self-determination theory: autonomy loss in high-stakes education environments. Probl. Educ. 21st Cent. 26, 30–41.

Bruinsma, M., and Jansen, E. P. (2010). Is the motivation to become a teacher related to pre-service teachers’ intentions to remain in the profession? Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 33, 185–200. doi:10.1080/02619760903512927

Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., et al. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motiv. Emot. 39, 216–236. doi:10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

Chirkov, V., Ryan, R. M., Kim, Y., and Kaplan, U. (2003). Differentiating autonomy from individualism and independence: a self-determination theory perspective on internalization of cultural orientations and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84, 97. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.97

Connell, J. P. (1990). “Context, self and action: a motivational analysis of self-system processes across the life span,” in The Self in Transition: From Infancy to Childhood, ed. D. Cicchetti (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press), 61–97.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2008). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Can. Psychol. 49, 14–23. doi:10.1037/0708-5591.49.1.14

Evelein, F., Korthagen, F., and Brekelmans, M. (2008). Fulfillment of the basic psychological needs of student teachers during their first teaching experiences. Teach. Teach. Educ. 24, 1137–1148. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2007.09.001

Eyal, O., and Roth, G. (2011). Principals’ leadership and teachers’ motivation: self-determination theory analysis. J. Educ. Admin. 49, 256–275. doi:10.1108/09578231111129055

Feinberg, O., Kaplan, H., Assor, A., and Kanat-Maymon, Y. (2008). Personal growth in a caring community: autonomy supportive intervention program for reducing violence and promoting caring. Dapim J. Stud. Res. Educ. 46, 21–61. MOFET Institute (Hebrew).

Fernet, C., Guay, F., Senécal, C., and Austin, S. (2012). Predicting intraindividual changes in teacher burnout: the role of perceived school environment and motivational factors. Teach. Teach. Educ. 28, 514–525. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.11.013

Fernet, C., Senécal, C., Guay, F., Marsh, H., and Dowson, M. (2008). The work tasks motivation scale for teachers (WTMST). J. Career Assess. 16, 256–279. doi:10.1177/1069072707305764

Flum, H., and Kaplan, A. (2006). Exploratory orientation as an educational goal. Educ. Psychol. 41, 99–110. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep4102_3

Friedman, I. A., and Farber, B. A. (1992). Professional self-concept as a predictor of teacher burnout. J. Educ. Res. 86, 28–35. doi:10.1080/00220671.1992.9941824

Gao, X., and Trent, J. (2009). Understanding mainland Chinese students’ motivations for choosing teacher education programs in Hong Kong. J. Educ. Teach. 35, 145–159. doi:10.1080/02607470902771037

Ginevra, M. C., Nota, L., Soresi, S., Shogren, K. A., Wehmeyer, M. L., and Little, T. D. (2015). A cross-cultural comparison of the self-determination construct in Italian and American adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 20, 501–517. doi:10.1080/02673843.2013.808159

Grotevant, H. D. (1987). Toward a process model of identity formation. J. Adolesc. Res. 2, 203–222. doi:10.1177/074355488723003

Hanfstingl, B., Andreitz, I., Müller, F. H., and Thomas, A. (2010). Are self-regulation and self-control mediators between psychological basic needs and intrinsic teacher motivation? J. Educ. Res. Online 2, 55–71.

Hattie, J. A. C. (2003). Teachers make a difference: what is the research evidence? Paper Presented at the Building Teacher Quality: What Does the Research Tell Us. Australian Council for Educational Research – ACER Research Conference, Melbourne, Australia. Available at: http://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference_2003/4/

Iyengar, S. S., and DeVoe, S. E. (2003). Rethinking the value of choice: considering cultural mediators of intrinsic motivation. Nebraska Symp. Motiv. 49, 129–174.

Jang, H., Reeve, J., and Deci, E. L. (2010). Engaging students in learning activities: it is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. J. Educ. Psychol. 102, 588. doi:10.1037/a0019682

Jang, H., Reeve, J., and Halusic, M. (2016). A new autonomy-supportive way of teaching that increases conceptual learning: teaching in students’ preferred ways. J. Exp. Educ. 84, 686–701. doi:10.1080/00220973.2015.1083522

Jang, H., Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., and Kim, A. (2009). Can self-determination theory explain what underlies the productive, satisfying learning experiences of collectivistically oriented Korean students? J. Educ. Psychol. 101, 644. doi:10.1037/a0014241

Jansen in de Wal, J., den Brok, P. J., Hooijer, J. G., Martens, R. L., and van den Beemt, A. (2014). Teachers’ engagement in professional learning: exploring motivational profiles. Learn. Individ. Differ. 36, 27–36. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2014.08.001

Jungert, T., Alm, F., and Thornberg, R. (2014). Motives for becoming a teacher and their relations to academic engagement and dropout among student teachers. J. Educ. Teach. 40, 173–185. doi:10.1080/02607476.2013.869971

Kaplan, A., Gheen, M., and Midgley, C. (2002). Classroom goal structure and student disruptive behaviour. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 72, 191–211. doi:10.1348/000709902158847

Kaplan, H. (2016). Needs supporting environment and autonomous motivation in teaching of novice teachers. Paper Presented at the Sixth International Conference of Self-Determination Theory, June 2-5, 2016, Victoria, BC, Canada.

Kaplan, H., and Assor, A. (2001). Integrated motivation: the role of future-plans and identity development in promoting high-quality learning. Paper Presented at the Eighth EARLI Conference, Switzerland.

Kaplan, H., and Assor, A. (2012). Enhancing autonomy-supportive I – Thou dialogue in schools: conceptualization and socio-emotional effects of an intervention program. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 15, 251–269. doi:10.1007/s11218-012-9178-2

Kaplan, H., Assor, A., El-Sayed, H., and Kanat-Maymon, Y. (2014). The unique contribution of autonomy support and autonomy frustration to predicting an optimal learning experience in Bedouin students: testing self-determination theory in a collectivistic society. Dapim 58, 41–77.

Kaplan, H., and Madjar, N. (2013). The effects of needs-supportive teacher educators’ practices on pre-service teachers’ learning experience: a multicultural perspective. Paper Presented at the Fifth International Conference on Self-Determination Theory, June 27-30, Rochester, NY.

Kaplan, H., and Madjar, N. (2015). Autonomous motivation and pro-environmental behaviors among Bedouin students in Israel: a self-determination theory perspective. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 31, 223–247. doi:10.1017/aee.2015.33

Katz, I., and Shahar, B. H. (2015). What makes a motivating teacher? Teachers’ motivation and beliefs as predictors of their autonomy-supportive style. Sch. Psychol. Int. 36, 575–588. doi:10.1177/0143034315609969

Keefe, J. W., and Jenkins, J. M. (2000). Personalized Instruction: Changing Classroom Practice. Larchmont, NY: Eye on Education.

Kfir, D., and Ariav, T. (2008). The Crisis in Teacher Education: Reasons, Problems and Possible Solutions. Tel Aviv and Jerusalem: The Van Leer Jerusalem Institute and Hakibbutz Hameuchad (Hebrew).

Klassen, R. M., Perry, N. E., and Frenzel, A. C. (2012). Teachers’ relatedness with students: an underemphasized component of teachers’ basic psychological needs. J. Educ. Psychol. 104, 150. doi:10.1037/a0026253

La Guardia, J. G. (2009). Developing who I am: a self-determination theory approach to the establishment of healthy identities. Educ. Psychol. 44, 90–104. doi:10.1080/00461520902832350

La Guardia, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Within-person variation in security of attachment: a self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 367–384. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.3.367

Lam, S. F., Cheng, R. W. Y., and Ma, W. Y. (2009). Teacher and student intrinsic motivation in project-based learning. Instr. Sci. 37, 565–578. doi:10.1007/s11251-008-9070-9

Madjar, N., and Cohen-Malayev, M. (2013). Youth movements as educational settings promoting personal development: comparing motivation and identity formation in formal and non-formal education contexts. Int. J. Educ. Res. 62, 162–174. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2013.09.002

Marcia, J. E. (1993). “The ego identity status approach to ego identity,” in Ego Identity: A Handbook for Psychosocial Research, eds J. E. Marcia, A. S. Waterman, D. R. Matteson, S. L. Archer, and J. L. Orlofsky (New York, NY: Springer-Verlag), 3–22.

Maslach, C., and Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 2, 99–113. doi:10.1002/job.4030020205

Mwamwenda, T. S. (2010). Motives for choosing a career in teaching: a South African study. J Psychol Afr. 20, 487–489.

Paunonen, S. V., and O’Neill, T. A. (2010). Self-reports, peer ratings and construct validity. Eur. J. Pers. 24, 189–206. doi:10.1002/per.751

Pelletier, L. G., Levesque, C. S., and Legault, L. (2002). Pressure from above and pressure from below as determinants of teachers’ motivation and teaching behavior. J. Educ. Psychol. 94, 186–196. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.94.1.186

Perlman, D. (2015). Assisting preservice teachers toward more motivationally supportive instruction. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 34, 119–130. doi:10.1123/jtpe.2013-0208

Reeve, J. (1998). Autonomy support as an interpersonal motivating style: is it teachable? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 23, 312–330. doi:10.1006/ceps.1997.0975

Reeve, J. (2006). Teachers as facilitators: what autonomy supportive teachers do and why their students benefit. Elem. Sch. J.106, 225–236. doi:10.1086/501484

Reeve, J. (2013). How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: the concept of agentic engagement. J. Educ. Psychol. 105, 579–595. doi:10.1037/a0032690

Reeve, J., and Assor, A. (2011). “Do social institutions necessarily suppress individuals’ need for autonomy? The possibility of schools as autonomy promoting contexts across the globe,” in Human Autonomy in Cross-Cultural Context: Perspectives on the Psychology of Agency, Freedom and Well-Being, eds V. I. Chirkov, R. M. Ryan, and K. M. Sheldon (New York, NY: Springer), 111–132.

Reeve, J., Bolt, E., and Cai, Y. (1999). Autonomy-supportive teachers: how they teach and motivate students. J. Educ. Psychol. 91, 537–548. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.91.3.537

Reeve, J., Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2004). “Self-determination theory: a dialectical framework for understanding socio-cultural influences on student motivation,” in Big Theories Revisited, eds D. M. McInerney and S. Van Etten (Greenwich, CT: Information Age Press), 31–60.

Reeve, J., and Halusic, M. (2009). How K-12 teachers can put self-determination theory principles into practice. Theory Res. Educ. 7, 145–154. doi:10.1177/1477878509104319

Reeve, J., and Lee, W. (2014). Students’ classroom engagement produces longitudinal changes in classroom motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 106, 527–540. doi:10.1037/a0034934

Reeve, J., and Tseng, T. M. (2011). Cortisol reactivity to a teacher’s motivating style: the biology of being controlled versus supporting autonomy. Motiv. Emot. 35, 63–74. doi:10.1007/s11031-011-9204-2

Richardson, P. W., and Watt, H. M. G. (2014). “Why people choose teaching as a career: an expectancy-value approach to understanding teacher motivation,” in Teacher Motivation: Theory and Practice, eds P. W. Richardson, H. M. G. Watt, and S. A. Karabenick (New York, NY: Routledge), 3–19.

Richardson, P. W., Watt, H. M. G., and Karabenick, S. A. (2014). Teacher Motivation: Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

Rogat, T. K., Witham, S. A., and Chinn, C. A. (2014). Teachers’ autonomy relevant practices within an inquiry-based science curricular context: extending the range of academically significant autonomy supportive practices. Teach. Coll. Rec. 116, 1–46.

Roth, G. (2014). “Antecedents and outcomes of teachers’ autonomous motivation: a self-determination theory analysis,” in Teacher Motivation: Theory and Practice, eds P. W. Richardson, H. M. G. Watt, and S. A. Karabenick (New York, NY: Routledge), 36–51.

Roth, G., Assor, A., Kanat-Maymon, Y., and Kaplan, H. (2007). Autonomous motivation for teaching: how self-determined teaching may lead to self-determined learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 761–774. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.761

Ryan, R. M., and Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: examining reasons for acting in two domains. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57, 749–761.

Ryan, R. M. (1993). “Agency and organization: intrinsic motivation, autonomy and the self in psychological development,” in Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Developmental Perspectives on Motivation, Vol. 40, ed. J. Jacobs (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press), 1–56.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 54–67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2002). “An overview of self-determination theory,” in Handbook of Self-Determination Research, eds E. L. Deci and R. M. Ryan (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press), 3–33.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-Determination Theory. Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York, London: The Guilford Press.

Sharabi, M. (2014). The relative centrality of life domains among Jews and Arabs in Israel: the effect of culture, ethnicity, and demographic variables. Commun. Work Fam. 17, 219–236. doi:10.1080/13668803.2014.889660

Soenens, B., Sierens, E., Vansteenkiste, M., Dochy, F., and Goossens, L. (2012). Psychologically controlling teaching: examining outcomes, antecedents, and mediators. J. Educ. Psychol. 104, 108–120. doi:10.1037/a0025742

Spittle, M., Jackson, K., and Casey, M. (2009). Applying self-determination theory to understand the motivation for becoming a physical education teacher. Teach. Teach. Educ. 25, 190–197. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2008.07.005

State of Israel, Central Bureau of Statistics. (2015). “New teachers dropping out of the education system 2000-2014,” in Statistical Yearbook of Israel. Available at: http://www.cbs.gov.il/reader/newhodaot/hodaa_template.html?hodaa=201506197

Struyven, K., Jacobs, K., and Dochy, F. (2013). Why do they want to teach? The multiple reasons of different groups of students for undertaking teacher education. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 28, 1007–1022. doi:10.1007/s10212-012-0151-4

Summers, E. J., and Dickinson, G. (2012). A longitudinal investigation of project-based instruction and student achievement in high school social studies. Interdiscip. J. Probl. Based Learn. 6, 82–103. doi:10.7771/1541-5015.1313

Taylor, I. M., and Ntoumanis, N. (2007). Teacher motivational strategies and student self-determination in physical education. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 747. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.747

Taylor, I. M., Ntoumanis, N., and Smith, B. (2009). The social context as a determinant of teacher motivational strategies in physical education. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 10, 235–243. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.09.002

Taylor, L., Ntoumanis, N., and Standage, M. (2008). A self-determination theory approach to understanding antecedents of teachers’ motivational strategies in physical education. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 30, 75–94. doi:10.1123/jsep.30.1.75

The European Commission Staff Working Document-SEC. (2010). “Developing coherent and system-wide induction programmes for beginning teachers: a handbook for policy makers,” in European Commission Staff Working Document 538. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/education_culture/repository/education/library/publications/handbook0410_en.pdf

Triandis, H. C. (1999). Cross-cultural psychology. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2, 127–143. doi:10.1111/1467-839X.00029

Van den Berghe, L., Soenens, B., Aelterman, N., Cardon, G., Tallir, I. B., and Haerens, L. (2014). Within-person profiles of teachers’ motivation to teach: associations with need satisfaction at work, need-supportive teaching, and burnout. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 15, 407–417. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.04.001

Vansteenkiste, M., and Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. J. Psychother. Integr. 23, 263. doi:10.1037/a0032359

Wang, C. K. J., and Liu, W. C. (2008). Teachers’ motivation to teach national education in Singapore: a self-determination theory approach. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 28, 395–410. doi:10.1080/02188790802469052

Watt, H. M., and Richardson, P. W. (2007). Motivational factors influencing teaching as a career choice: development and validation of the FIT-Choice Scale. J. Exp. Educ. 75, 167–202. doi:10.3200/JEXE.75.3.167-202

Weissblei, E. (2013). Status of Teachers in Israel and OECD Countries: Training, Qualification, Salary, and Work Conditions. Knesset Research and Information Center. Available at: https://www.knesset.gov.il/mmm/data/pdf/m03321.pdf

Williams, G. C., and Deci, E. L. (1996). Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: a test of self-determination theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 767–779. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.767

Keywords: self-determination theory, pre-service teachers, multicultural context, structural equation modeling, psychological needs, autonomous motivation

Citation: Kaplan H and Madjar N (2017) The Motivational Outcomes of Psychological Need Support among Pre-Service Teachers: Multicultural and Self-determination Theory Perspectives. Front. Educ. 2:42. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00042

Received: 12 April 2017; Accepted: 28 July 2017;

Published: 25 August 2017

Edited by:

Meryem Yilmaz Soylu, University of Nebraska Lincoln, United StatesReviewed by:

Robbert Smit, University of Teacher Education St. Gallen, SwitzerlandBarbara Hanfstingl, Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt, Austria

Copyright: © 2017 Kaplan and Madjar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haya Kaplan, a2FwbGFuaEBrYXllLmFjLmls

Haya Kaplan

Haya Kaplan Nir Madjar

Nir Madjar