- Curriculum and Pedagogy, Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Literacy is increasingly being thought of as a social practice with its use and understandings being context dependent. As an essential element within and of education, literacy offers possibilities for engaging in everyday life. Health literacy has emerged as a means to develop health-promoting practices that has meaning in social contexts. Reflecting biomedical interests, the focus of health literacy is predominately constructed as a neutral and technical process that has specific meaning and practice, positioning it as functional literacy. This paper presents one approach to critical health literacy based on a multidimension (3D) approach with literacy as a situated social practice. The 3D model will be described and then the model’s application to health literacy will be explored. The use of the 3D model to build critical health literacy challenges the biomedical approach to health literacy as solely functional literacy. Functional literacy is not sufficient for a person to build a critical social consciousness and illuminate how social determinates of health create inequitable health or how it could be ameliorated. Social justice and equity are presented as fundamental prerequisites for health. Working with young people in context of schools, the reciprocal relationship between health and education offers space for possibilities around literacy skills and understanding about what creates health. The same space can enable young people to see opportunities for empowerment to shape and recreate their social reality. Health literacy for social justice and equity, therefore, has to include possibilities for understanding and responding to sociocultural knowing.

According to the World Health Organization (2010), social determinates of health are the main causes of health inequity. Health inequity is avoidable. Arising out of social and economic conditions, the impact of health inequality affects the lives of people and determines the level of risk for preventable illness as well as their capacity to prevent or manage their ill health. It is important to also note that health inequities are significantly reduced in civil societies. It is within civil societies that there is democratic engagement, and wealth is redistributed so that it benefits the majority rather than the privileged few.

The past 20 years has seen health literacy emerge and become identified as a resource for health (Wilkinson and Marmot, 2003; Sykes et al., 2013). The Jakarta Declaration (World Health Organization, 1997) argues that participation and engagement in health literacy is an activity that supports health (Paasche-Orlow and Wolf, 2007; Renwick, 2014). Furthermore, Speros (2005) contends that health literacy can be perceived as a stronger predictor of health status than a person’s socioeconomic status, age, or ethnic background. There is currently no one common definition of health literacy (Speros, 2005; Wharf-Higgins et al., 2009; Chinn, 2011); however, shared conceptualizations that are emerging include that it is a social practice and that builds a critical social consciousness about health that benefits individuals, their family, and the community-at-large.

This article considers how health literacy is being conceptualized, and how, as a situated social practice, it contributes to understandings of citizenship, identity as a healthy person, and of how health is built in socially positive ways. Health literacy is increasingly evident in school curricula and is considered for how it enables young people to achieve health literacy in more equitable ways. Specifically, Green’s 3D model (Green 1999, 2012a) is applied to health literacy to demonstrate how the inclusion of a critical dimension offers possibilities for a critical social consciousness.

Health Literacy Models

Literacy is increasingly recognized as a social practice (Green, 2012b) and health literacy is more than reading texts and symbols relevant to health system and care (Renwick, 2013). Nutbeam (2009) has also argued that health literacy is both content and context specific. Drawing on the work of Freebody and Luke (1990), Nutbeam (2000) developed a model for health literacy based on three levels of literacy: (i) functional health literacy; (ii) interactive health literacy and; (iii) critical health literacy. Sykes et al. (2013) argue that Nutbeam’s definition of critical health literacy has not been utilized widely. According to Wharf-Higgins et al. (2009), health promotion researchers have not paid attention to context so they have not been able to convey knowledge that makes sense within the social spaces that people inhabit that also generate the conditions for health literacy.

The debate about health literacy within the health field is limited to a particular paradigm. The results of commonsense positions and knowing’s about what is both needed and possible are reflective of considerations about efficacy in health care (Speros, 2005). This leads to a second reason for a lack of engagement in critical literacy due to an inability to measure health literacy against social and political skill sets. For critical health literacy to develop, Sykes et al. (2013) argues that there is a need to “to locate responsibility beyond the individual level” (p. 159). Chinn (2011) has observed the significant expansion of health literacy since the mid 1990s, with only a few focused on critical health literacy (Sykes et al., 2013).

Nutbeam’s (Nutbeam, 2000) modeling of Freebody and Luke’s (Freebody and Luke, 1990) work on effective literacy into health promotion has not been fully referenced and is, therefore, absent in wider health literacy debates. Freebody and Luke identified components of success in literacy practice—a heuristic guide for decoding what literacy is. This guide describes four roles that a successful reader uses: (i) code breaker; (ii) text participant; (iii) text user; and (iv) text analysis. Furthermore, no one role is sufficient for meeting the interests of the individual or the collective, while engaging with a range of texts, tasks, and discourses. To date, these roles have not been included in any of the debates regarding health literacy, and have been only provided in one discussion of how to approach health literacy with young people in schools (Renwick, 2013).

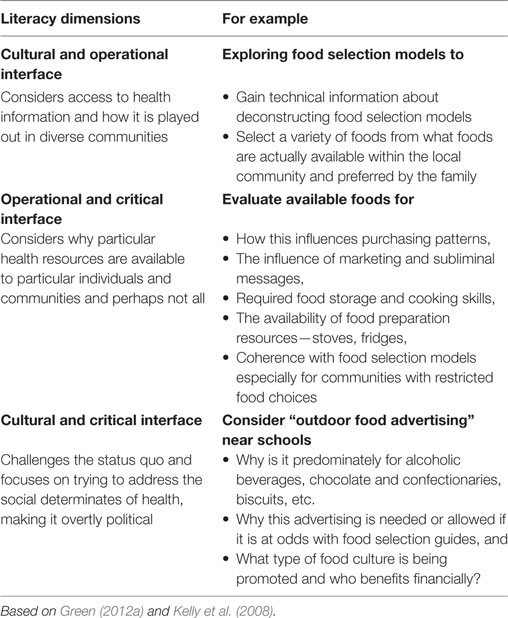

A second model of literacy, emerging at the same time as Freebody and Luke’s work and developed by Green (1999) brings together the three familiar areas of practice for literacy that can be seen in Nutbeam’s (Nutbeam, 2000) model (see Figure 1A). The three dimensions “are to be understood as working simultaneously in any literacy event, and not hierarchically” [(Green, 2012b), p. 175]. This is significant deviation from the way in which health promotion uses Nutbeam’s model, where it is assumed that the three different literacies are hierarchical and mutually exclusive (Wharf-Higgins et al., 2009; Chinn, 2011).

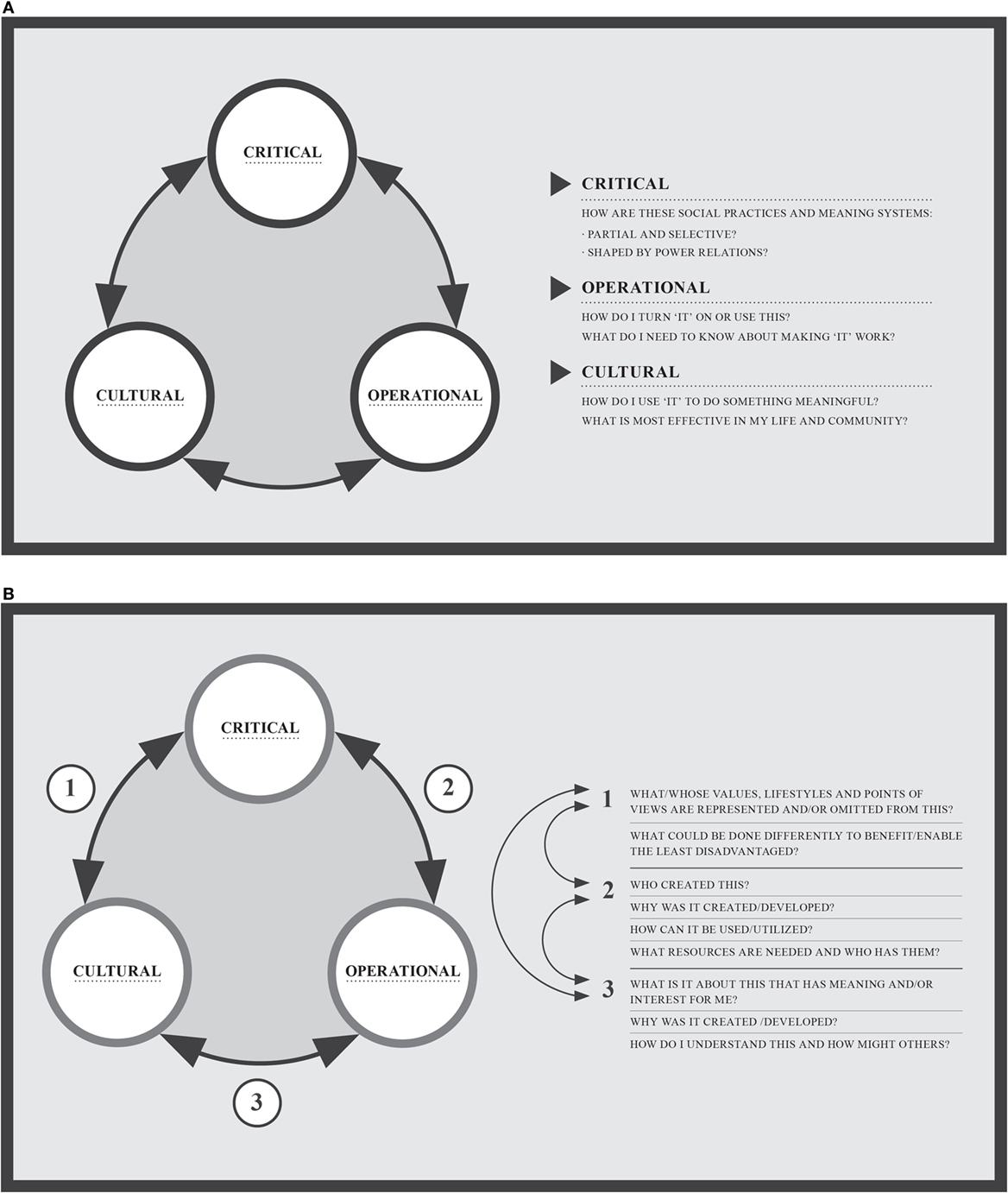

Figure 1. (A) 3D model of literacy [based on Green (1999)]. (B) Critical health literacy in 3D [based on Green (1999) and Thoman and Jolls (2004)].

Green’s model demonstrates how literacy is a “situated social practice”. Green (2012a) describes it as a 3D model, it draws upon the three dimensions for literate practice that are connected with the social context. Since health is “determined by the different social, economics, and environmental circumstance” (Nutbeam, 2000, p. 260), then there is congruence with the 3D model and, therefore, as a model for health literacy.

Health literacy becomes a means for not only acquiring knowledge but also as a resource for engaging in health at personal and community levels (Sykes et al., 2013). Health literacy in this sense is not just about how the individual engages with health texts but also how these texts can be interrogated in order to support or challenge opportunities for equitable health. Health literacy is becoming increasingly referenced in school curricula; however, a critical perspective on health literacy is challenging in an era of performativity.

Health Literacy for Youth and Imagined Futures

Wharf-Higgins et al. (2009) have observed that health literacy is usually defined at/by adult levels of competence and the associated debate continues to focus on adults (American Medical Association, 1999; Nutbeam, 2009). Adults are not suddenly proficient in adult/real world practices especially in regards to health; rather, being health literate as an adult is by its very nature predicated on what has gone before; hence, the benefit in considering health literacy in schools (Jensen, 2000; Borzekowski, 2009).

Borzekowski (2009) observes that children and youth have particular health risks, however, these are unlikely to be identified within writings on health literacy in ways that risks for other groups are. Rather than being considered in their own right, any consideration of health literacy for children and youth is presumed through the agency of others—parents, caretakers, guardians, teachers, youth workers, etc. If the observation that health literacy and health outcomes are inter-related (DeWalt and Pignone, 2005; Paasche-Orlow and Wolf, 2007), the health literacy needs of children and youth are worthy of attention. This has substantial implications for not only how youth view themselves and their relationship with their organic body but also the shaping of how others “see” them (James and Hockey, 2007).

The future imagined is an all-pervading component of school health education and promotion whereby today’s experience of health is somehow different to that of tomorrow (Jensen, 2000; Renwick, 2014). This can be seen in aims for behavioral change and informed decision-making processes. School health education and promotion programs focus on influencing a child or teenager’s health behavior so as to have a longer-term impact on their adult health status. While these are not inappropriate intentions per se, the issue is more about the ethics and efficacy of such programs. The model of healthy lifestyles and activities provided in classrooms may not connect with the lived reality of student lives (Kelly et al., 2008) and the impact of the social environment including the impact of unequal distribution of material wealth (James and Hockey, 2007), and requires action beyond the individual (Wilkinson and Marmot, 2003; Chinn, 2011; Sykes et al., 2013). Where youth have little motivation to follow the healthy lifestyles outlined in class (Kelly et al., 2008), it is unlikely to affect their future health (Renwick, 2014).

What, therefore, are the possibilities for health education and promotion in schools that offers opportunity for action to support health, and that allows individuals to begin and continue the development of health literacy? How might this be presented so that is meaningful within the growing stages of life and classroom experiences as well as establishing a (latent) capability to be drawn on in any near and further future? This requires learning to engage with health texts in ways that develop capabilities to be able to learn and manage as required in one’s health future compared to “learning” about those aspects of health/illness/disease that might have or will never have an impact (Renwick, 2014). Kickbusch (2009) suggests that health literacy is a “challenge of access” and “is about rights, access and transparency” (p. 132) in an inequitable world. The provision of opportunities to develop critical health literacy capabilities in young people is needed.

Health Literacy as Situated Social Practice

According to Green (2012b), being literate and engaging with literacy is a socially situated act that engages with power relations. If young people only experience a dominant view of literacy that is limited predetermined skill development and embodied text, then necessary societal transformation is not possible (Green, 2012b; Renwick, 2014). Such positions are mirrored in health education where skills for health and behavioral change predominate, and health literacy is only at a functional or communicative level. In the conceptualization of health literacy, the focus is on the developing diagnostic tools (McCray, 2005); and rewriting medical communication that utilizes plain English or first language (Speros, 2005).

Critical health literacy has to attend to the validity of culturally diverse and often inequitable life experiences that generate health, and the necessary “empowerment needed to act on the social determinants of health” (Chinn, 2011, p. 65). By applying the 3D model of literacy to health literacy, the interplay of all three aspects demands substantially more than the functional health literacy being promulgated as reading and writing skills in a health-care setting (American Medical Association, 1999) or about compliant self management or required system documentation (DeWalt and Pignone, 2005). Health literacy that encompasses the interrelationship between the three aspects is a more effective enabler of possibilities for capacity building and empowerment (Renwick, 2013). The 3D model, when applied to health literacy (see Figure 1B), demonstrates the interplay of the three equally important dimensions together with consideration of how each dimension interfaces with the others, and generates possibilities for inquiry and reflection.

Exploring the dimensions and how they intersect is a way to demonstrate how health literacy can go beyond surviving in one’s social context, to being able to integrate with the social context, and use critical capacities to both make choices and transform reality (Freire, 1973). Using food and nutrition as a focus (see Table 1), it is possible to see how these both inform and construct learning experiences as well as enable and enact health literacy.

By describing what each dimension of the 3D model focuses on together and how they interface and interplay, a type of literacy emerges that is not necessarily expected. What is offered is a focus on problem-posing, giving students license to understand their world through different and multiple texts (Freire and Macedo, 1987). Classrooms are not isolated, and on any given day, students and teachers bring any number of family/community “pieces” with them—racism, sexism, classism (Fecho and Allen, 2003). These play out in everyday scenarios as students try to make some sense of what they are being asked to learn against what they already know but in impassive ways.

Experiencing health literacy through a medical and health-care dominance, students are subordinated to accept health inequities experienced in their families and communities rather than perceive possibilities for change that generates better health. Social determinants of health are readily identifiable within classrooms, and they are important spaces to generate understandings and build capacity to achieve Health For All. In thinking about schools as sites for primary health promotion, any consideration of health literacy has to be so much more than about reading, writing, compliance, and regimes.

Conclusion

The provision of opportunity for young people in schools to develop critical health literacy supports many possibilities for enhancing health literacy (Kickbusch, 2009). When given the chance, young people are able to consider how their use of critical health literacy has relevance within their own sociocultural context and, therefore, has meaning for both themselves and their community. In presenting the 3D model, Green (1999, 2012a) challenges us to consider how textual practice needs to be transformative and, therefore, makes a difference (Green, 2012b). Thus, health literacy practice should create change within a context where individual and community health is generated both physically and socially.

This article has considered how health literacy can be used specifically with young people in schools to view health in more equitable ways. As a situated social practice, health literacy that is critical is able to reveal how social, economics, and environmental conditions impact the health of diverse social groups. This is not sufficient in and of itself and, therefore, a critical health literate person is also able to see and enact possibilities for action on social determinates of health. Green’s (Green, 1999, 2012a) 3D model of health literacy was used as a way to deconstruct health literacy and, therefore, to reveal possibilities for critical social consciousness as espoused by Freire (1973). In accepting that health is a basic human right and that health inequalities are avoidable, there is a moral obligation upon us to act. Further consideration is, therefore, warranted as to the difference to be made when health literacy makes visible knowledge and cultural expectations, and builds a repertoire of reflective practice, through understandings of power and social justice.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

American Medical Association. (1999). Health literacy report of the Council of Scientific Affairs. Ad Hoc Committee on health literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 281, 552–557.

Borzekowski, D. L. (2009). Considering children and health literacy: a theoretical approach. Pediatrics 124(Suppl. 3), S282–S288. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1162D

Chinn, D. (2011). Critical health literacy: a review and critical analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 73, 60–67. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.004

DeWalt, D. A., and Pignone, M. P. (2005). Reading is fundamental: the relationship between literacy and health. Arch. Intern. Med. 165, 1943–1944. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.17.1943

Fecho, B., and Allen, J. (2003). “Teacher inquiry into literacy, social justice, and power,” in The Handbook of Research on Teaching the English Language Arts, 2nd Edn, eds J. Flood, D. Lapp, J. R. Squire, and J. M. Jensen (New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.), 232–246.

Freebody, P., and Luke, A. (1990). “Literacies” programs: debates and demands in cultural context. Prospect 5, 7–16.

Green, B. (2012a). “Subject-specific literacy and school learning: a revised account,” in Literacy in 3D: An Integrated Perspective in Theory and Practice, Chap. 1, eds B. Green, and C. Beavis (Camberwell, VIC: ACER Press), 2–21.

Green, B. (2012b). “Into the fourth dimension,” in Literacy in 3D: An Integrated Perspective in Theory and Practice, Chap. 11, eds B. Green, and C. Beavis (Camberwell, VIC: ACER Press), 174–187.

Jensen, B. B. (2000). Health knowledge and health education in the democratic health-promoting school. Health Educ. 100, 146–154. doi:10.1108/09654280010330900

Kelly, B., Cretikos, M., Rogers, K., and King, L. (2008). The commercial food landscape: outdoor food advertising around primary schools in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 32, 522–528. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00303.x

Kickbusch, I. (2009). Health literacy: engaging in a political debate. Int. J. Public Health 54, 131–132. doi:10.1007/s00038-009-7073-1

McCray, A. T. (2005). Promoting health literacy. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 12, 152–163. doi:10.1197/jamia.M1687

Nutbeam, D. (2000). Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 15, 259–267. doi:10.1093/heapro/15.3.259

Nutbeam, D. (2009). Defining and measuring health literacy: what can we learn from literacy studies? Int. J. Public Health 54, 303–305. doi:10.1007/s00038-009-0050-x

Paasche-Orlow, M. K., and Wolf, M. S. (2007). The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am. J. Health Behav. 31(Suppl. 1), S19–S26. doi:10.5993/AJHB.31.s1.4

Renwick, K. (2013). Critical reading in health literacy. Int. J. Literacies 19, 99–107. doi:10.18848/2327-0136/CGP/v19i02/48777

Renwick, K. (2014). Critical health literacy: shifting textual–social practices in the health classroom. Asia Pacific J. Health Sport Phys. Educ. 5, 201–216. doi:10.1080/18377122.2014.940808

Speros, C. (2005). Health literacy: concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 50, 633–640. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03448.x

Sykes, S., Wills, J., Rowlands, G., and Popple, K. (2013). Understanding critical health literacy: a concept analysis. BMC Public Health 13:150. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-150

Thoman, E., and Jolls, T. (2004). Media literacy: a national priority for a changing world. Am. Behav. Sci. 48. Available at: http://www.medialit.org/reading-room/media-literacy-national-priority-changing-world

Wharf-Higgins, J., Begoray, D., and MacDonald, M. (2009). A social ecological conceptual framework for understanding adolescent health literacy in the health education classroom. Am. J. Community Psychol. 44, 350–362. doi:10.1007/s10464-009-9270-8

Wilkinson, R. G., and Marmot, M. G. (2003). Social Determinants of Health: The Solid Facts. Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. (1997). Jakarta Declaration for Health Promotion. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Keywords: critical health literacy, critical social consciousness, health promotion, health education, social justice and equity

Citation: Renwick K (2017) Critical Health Literacy in 3D. Front. Educ. 2:40. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00040

Received: 23 May 2017; Accepted: 17 July 2017;

Published: 08 August 2017

Edited by:

Matthew Lee Smith, University of Georgia, United StatesReviewed by:

Alba Rosalia Nuñez, Instituto de Pedagogía Crítica (IPEC), MexicoMarcia G. Ory, Texas A&M University, United States

Copyright: © 2017 Renwick. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kerry Renwick, a2VycnkucmVud2lja0B1YmMuY2E=

Kerry Renwick

Kerry Renwick