- 1The Cairns Institute, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 2School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, Central Queensland University, CNR Shield and Abbott Sts, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 3College of Public Health, Medical and Veterinary Sciences, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 4Transition Support Service, Queensland Department of Education and Training, Parramatta School, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 5Resilience Research Centre, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

- 6Apunipima Cape York Health Council, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 7School of Population Health, University of Queensland at St Lucia, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Background: Australian policies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander well-being outline the importance of local community-based interventions; for adolescents, school-based programs have been identified as beneficial. However, there is a lack of localized data to determine levels of resilience and risk and thus whether programs are effective. This paper describes the challenges and opportunities in collaboratively designing and piloting a localized survey instrument to measure Indigenous students’ resilience and upstream risk factors for self-harm and the resultant instrument.

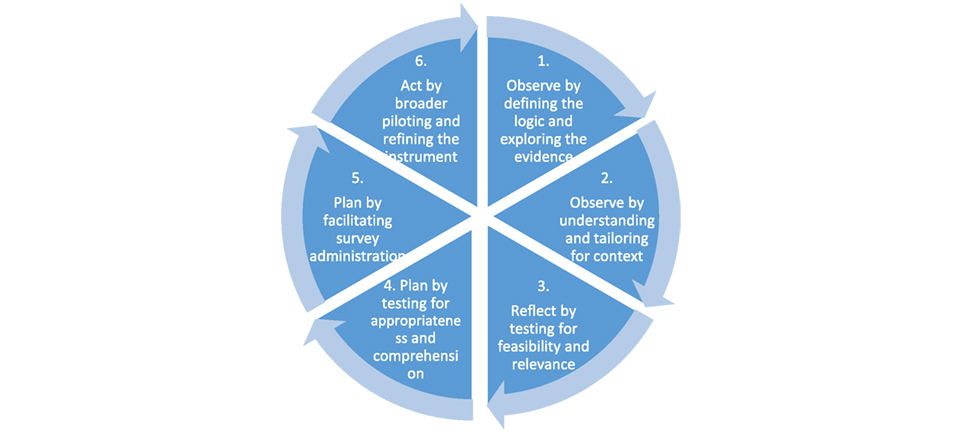

Methods: A participatory action research approach was used to engage education staff, health-care providers, students, and researchers to design and pilot the survey instrument. A six-phased process facilitated survey development: (1) defining the logic and exploring the evidence; (2) understanding and tailoring for context; (3) testing for feasibility and relevance; (4) testing for appropriateness and comprehension; (5) facilitating survey administration; and (6) refining the instrument. Processes in each phase were recorded and transcribed with thematic analysis used to identify key challenges and opportunities arising during development.

Results: Four key challenges and opportunities were identified: (1) the relevance of international survey instruments for Indigenous Australian students; (2) accounting for distinct environments; (3) the balance between assessing risk and protective factors; and (4) tailoring for literacy levels and school engagement. The final Student Survey instrument comprised 4 demographic and 56 resilience, risk, service use, and satisfaction questions. The T4S will be administered routinely on annual student intake.

Discussion and conclusion: The six-phased participatory processes resulted in a tailored instrument that could identify the critical resilience and upstream risk factors facing a cohort of Indigenous students who attend boarding schools for secondary education. Challenges were resolved collaboratively and the pilot results were directly translated to education practice and its integration with health services. Our results suggest that both the phased process of developing the T4S and the instrument itself can be adapted for other Indigenous adolescent well-being and/or self-harm prevention programs.

Introduction

From 2013, Australian national policy documents have advocated the use of local approaches to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (hereafter respectfully termed Indigenous) well-being (Commonwealth of Australia, 2013). In 2015, Primary Health Networks were introduced in the most significant transformation of the Australian health-care system since Medicare and will assume the lead role in planning across mental health, substance misuse, and suicide prevention initiatives at the regional and local levels. The need for evidence-based approaches was reiterated for the priority Indigenous populations (Booth et al., 2016). School-based programs were identified as offering particular opportunities for Indigenous adolescents (Commonwealth of Australia, 2013).

Along with local approaches, there is a corresponding need for local health and education indicators of Indigenous social environments and individual health determinants and outcomes, particularly for small remote communities (Abonyi et al., 2013; Commonwealth of Australia, 2013). In Australia, data for Indigenous well-being and self-harm are aggregated and available only at state and national levels (Dockery, 2011) and information relevant to understanding the relationship of risk and protective factors is very limited. Hence, determining local self-harm risk and protective factors requires services and/or researchers to identify appropriate routine and/or survey data.

As with all aspects of Indigenous people’s lives, when developing measures of well-being, it is necessary to ensure that defined constructs are measured in ways that are meaningful. Some of the most vital aspects of behavior and experience are intangible and can only be measured indirectly. For example, the concept of resilience has not been well conceptualized for Indigenous peoples, even though cross-cultural work on resilience has shown a common set of social, physical, and cultural environments as well as personal qualities that predict successful coping in contexts of adversity (Zubrick et al., 2010; Ungar, 2011). Similarly, the upstream risk factors for self-harm can include a multitude of cumulative personal or distal factors across diverse cultures such as histories of trauma or grief from discrimination, removal of children, premature deaths of community members and their impact on cultural identity, sexual or physical abuse or neglect, physical and mental illness, interpersonal violence, history of self-harm, substance abuse, juvenile detention, and/or police custody (Zubrick et al., 2010). The complex interaction of such factors in relation to Indigenous suicide has been termed risk amplification (Hunter and Milroy, 2006).

International survey instruments are readily available sources from which questions of well-being can be drawn, but these are generally framed within Western epistemological foundations and may not represent the experiences of Indigenous peoples whose worldviews and cultural identities differ (Bodkin-Andrews et al., 2010; Antonio and Chung-Do, 2015). The majority of the internationally available survey instruments focus on deficit health risk factors rather than on well-being or resilience; concepts that have long been advocated by Indigenous people (e.g., Bainbridge et al., 2013b). This contrasts with the holistic view of health held by many Indigenous Australians, whereby the social, emotional, spiritual, and cultural well-being of the whole community is essential for the health and well-being of the individuals that comprise it (Garvey, 2008). Connection to land or “country” (traditional place of family origin), culture, spirituality, ancestry, family, and community are considered to be central to well-being (Gee et al., 2014). Indigenous-developed or tailored survey instruments may therefore be more acceptable to Indigenous survey administrators and participants, particularly with sensitive topics such as mental health (Antonio and Chung-Do, 2015). Decisions about survey constructs should therefore be led by Indigenous services, with local people involved in the process (Abonyi et al., 2013; Anderson et al., 2016, p. 2063).

This paper describes the challenges and opportunities experienced in the collaborative, participatory, and multi-phased design, development, and piloting of a tailored survey instrument to assess the resilience and the risk factors for self-harm of a cohort of Indigenous secondary school students and the resultant tailored survey instrument. The student survey was designed and developed for annual implementation as a routine measure for assessing students’ self-reported resilience and exposure to upstream risk factors for self-harm to (1) inform appropriate targeting, prioritization and improvement of student support, including early response to identified risk and (2) determine how well a resilience-based student support program worked. We adopted Ungar’s (Ungar, 2008), p. 225 definition of resilience as navigation “to the psychological, social, cultural, and physical resources that sustain well-being, and capacity individually and collectively to negotiate for these resources to be provided in culturally meaningful ways.” Resources to support resilience include healthy relationships, a powerful identity, social justice, material needs such as food and education, cultural continuity, and a sense of belonging, life purpose, and spirituality (Ungar et al., 2007).

Materials and Methods

Research Approach

The survey instrument was developed as part of a 5-year collaborative and participatory research project between the Transition Support Service (TSS) of the Queensland Department of Education and Training and (removed for blind review) University researchers. This broader research project was instigated in response to needs expressed by TSS to better target, prioritize, and improve student support, including early response to identified risk factors for self-harm (reference removed for blind review). Supported by international and national investigators, the project was funded from December 2014.

A decolonizing research approach (Semaili and Kincheloe, 1999; Smith, 1999; Bishop, 2005) was adopted to align the study with efforts to produce benefits from research that are responsive to and respectful of Indigenous peoples rights and aspirations (Thomas et al., 2014; Bainbridge et al., 2015). Co-led by an Indigenous (XX removed for blind review) and non-Indigenous (XX) researcher, we endeavored to build a coalition of knowledge, practical application, and vision for Indigenous students based on the Indigenous research ethics of care and responsibility (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2010). Working at the cultural interface between Western and Indigenous knowledge, the concerns of Indigenous TSS staff members and researchers, and relevancy of measures for supported students were central to the process (Smith, 1999; Bainbridge et al., 2013a). Non-Indigenous researchers and practitioners were positioned as “allied other” (Denzin, 2007, p. 457).

Context

Indigenous secondary school students from remote Cape York and Palm Island communities in north Queensland, Australia are supported in their transitions to boarding schools across the State by TSS. Attendance at a boarding school is required because there is limited or no secondary education available in the Indigenous students’ home communities. Students are supported by TSS through three service streams: (1) year 6 students (10–11 years old) who will transition from primary to secondary schooling; (2) years 7–12 students (11–19 years old) who engage in secondary education at boarding schools; and (3) excluded students (11–19 years) who are supported to re-engage with other learning, training, or employment opportunities.

Participants

Researchers collaborated with 19 TSS staff members to design, develop, and pilot the research. TSS staff members are located both in remote communities and cities across Queensland, and comprise professional teachers, guidance officers, community-based support officers, and Indigenous youth mentors. Eleven TSS staff members were Indigenous (including eight youth mentors).

Twenty project investigators were consulted, including national and international researchers, clinicians, and education specialists, along with a local community-controlled health service, mental health service providers, and TSS staff members. Five were Indigenous Australians; 1 Maori and 14 non-Indigenous.

The 94 students (10–19 years of age) were all of TSS-supported students from 5 randomly selected schools and one remote community (3 boarding secondary schools, 2 primary schools, plus re-engagement students in 1 community). They were part of a larger cohort of approximately 515 TSS-supported students. All were Indigenous.

Data Collection

The design, development, and piloting of the survey occurred through a six-phased approach (Supplementary Table 1). Each phase was developed in collaboration with TSS staff, with advice from expert project investigators incorporated into phases 2 and 3, and from students incorporated into phases 4 and 6 (Figure 1). Participatory action research (PAR) was used to involve all relevant parties in actively examining the situation, and planning and conducting a research process to develop the survey instrument (Bergold and Thomas, 2012). PAR is ethical in that research is focused on the priorities, values, and preferences of the research end-users, and the convergence between everyday practice with research leads to a reinterpretation of situations and strategies (Bainbridge et al., 2011). PAR is consistent with international recommendations for strategies and methods to ensure the inclusive engagement of Indigenous peoples in the development of high-quality Indigenous data systems (Anderson et al., 2016).

Participatory action research typically requires multiple participatory and collaborative cyclical processes encompassing observation, reflection, planning, and action (Wadsworth, 1998; Crane and O’Regan, 2010; p. 13). Observation of what is happening in the situation starts the cycle by examining available or new information to describe the situation accurately. Reflection occurs through listening to the different perspectives and interpretations of stakeholders, brainstorming ideas, looking at alternative explanations, and building a shared understanding. In planning, those directly affected by the research are engaged to collaboratively clarify the questions being asked and determine potential actions. Through action, plans are systematically and creatively implemented with stakeholders, and the process is observed and documented. To conclude the PAR cycle and inform the start of the next cycle, the tentative answers to the research question/s and conclusions are shared within and beyond the PAR group (Crane and O’Regan, 2010).

Phase 1: Observe: Defining the Logic and Exploring the Evidence

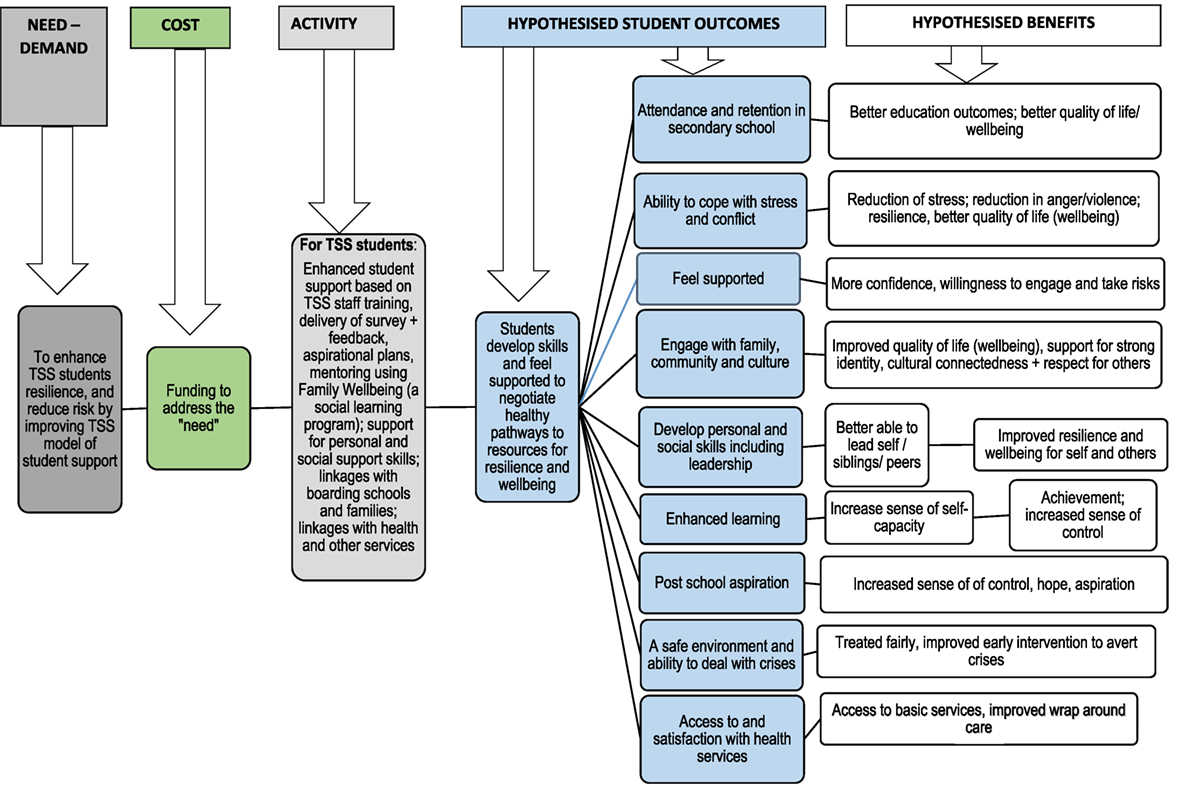

We started by identifying the available or new information required to assess the likely resilience and self-harm risks of TSS-supported students. Based on the work of Searles et al. (2016), a program logic model was developed to identify the key pathway between TSS student support and potential outcomes and the expected attributable benefit of the TSS/research approach (Figure 2). Research benefit was understood as the establishment or enhancement of capacities, opportunities or outcomes that advance the interests of Indigenous people and that are valued by them (Bainbridge et al., 2015; Tsey et al., 2016).

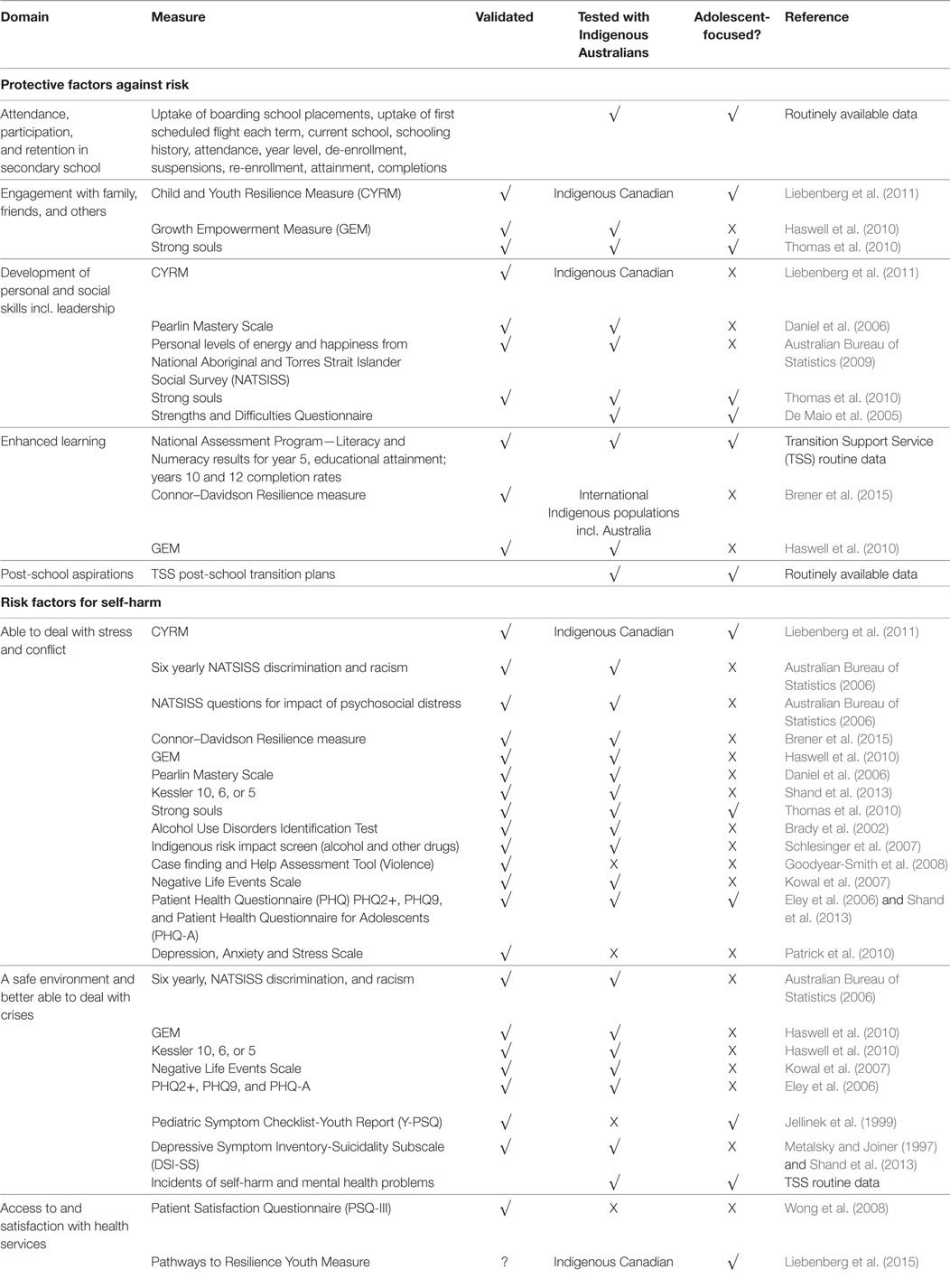

To ensure that we brought the most appropriate resilience and risk measures to the study, we searched the international literature and websites and consulted with project investigators to find measurement tools that (1) matched the domains identified in the logic framework; (2) were supported by evidence (validated); and (3) had relevance for the TSS student cohort (were developed for and/or effectively applied with Indigenous peoples and/or adolescent-focused). In addition, we identified relevant data that were routinely available through TSS.

We then created a checklist for selecting measures (adapted from Searles et al., 2012). The checklist specified that each measure should be selected according to how well it:

• Represented an issue of relevance to students at the school and/or community level;

• Was useful for TSS when they plan, develop, or refine programming at the school and/or community levels;

• Was evidence based or was clearly evidence informed;

• Showed reasonable sensitivity to change over time;

• Allowed comparison over time and with people from other geographic areas;

• Had low or reasonable cost for data collection, analysis and reporting of results; and

• Was easily interpreted by education and health and well-being experts and the wider community.

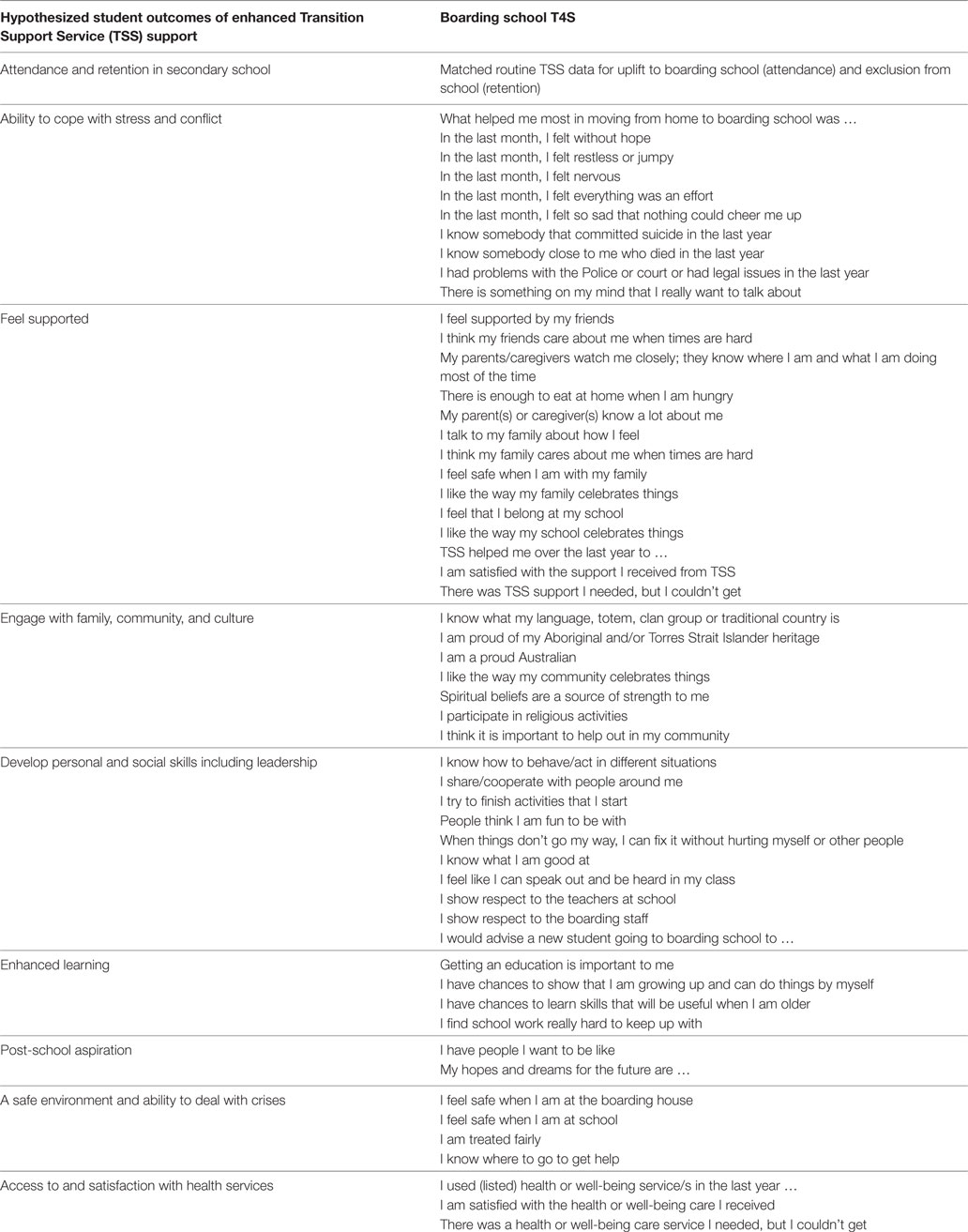

An initial lengthy mega-survey was drafted which encompassed the domains outlined in the program logic to provide a basis for reflection by TSS and project investigators (Table A1 in Appendix). Where possible, we prioritized Indigenous Australian and adolescent-focused measures.

Phase 2: Observe: Understanding and Tailoring for Context

A second observational phase sought to determine resilience and self-harm risk in the contexts experienced by TSS-supported students to consider which measures, identified through the literature search, would be most appropriate. A face-to-face workshop was held with two TSS staff members, two project investigators, an expert in survey design and four project researchers. Participants were asked to identify: “How do you recognize a TSS-supported student who is doing well?” Attributes were mapped on a whiteboard. The information from phase 2 was used to refine the mega-survey and develop a first draft of the Transition Support Service Student Survey (T4S) (Table A1 in Appendix).

Phase 3: Reflect: Testing for Feasibility and Relevance

In phase 3, TSS staff (n = 17), including four Indigenous youth mentors, participated in a face-to face meeting with researchers to test the draft T4S. Researchers explained the T4S and TSS staff members were asked to trial the survey, answering questions as though they were a student. Each staff member was invited to ask the researchers clarifying questions and to provide warm and cool feedback on any aspect of the survey using the Coalition of Essential School’s Exhibitions Tuning Protocol (Blythe et al., 1999). Expert advice was also sought from project investigators about how best to ask questions about risk and life stressors and how to respond appropriately to students who scored high on these questions. Their perspectives and interpretations were used to refine a second draft of the T4S which encompassed four sections and a 5-point rating scale (Table A1 in Appendix).

Phase 4: Plan: Testing for Appropriateness and Comprehension

This planning phase entailed piloting the T4S with students to clarify whether the questions being asked were relevant and comprehensible. Three Indigenous students of year levels 7, 10, and 12 were asked to test an online version of the T4S, using iPads. The older students took 10–20 min to complete the survey, but younger student, took 30 min to complete, and required explanation of some of the questions and differentiated points on the 5-point scale.

Phase 5: Plan: Facilitating Survey Administration

Transition Support Service staff were also engaged in determining processes for obtaining parent/caregiver consent. Given the sensitive nature of the project, and history of mistrust by Indigenous Australians of research (Bainbridge et al., 2015), consent required face-to-face meetings between TSS staff and parents/caregivers located in 11 Cape York communities and Palm Island. TSS workers met with each family to describe the research project and obtain informed consent, often prior to their child leaving their home community to return to boarding school after vacation breaks. Student consent was incorporated into the survey instrument, with all surveys de-identified to maintain student confidentiality.

Mindful of the diverse school and remote community settings in which the survey would be administered and the potential for individual or group administration, the T4S was made available through three survey format options: (1) online using Survey Monkey on iPads or computers; (2) offline using Quicktap, a survey application designed to collect data using iPads without an internet connection; and (3) paper based. Logistical issues were faced in transitioning the surveys from Survey Monkey to QuickTap; specific questions that had not held formatting between the two different survey platforms had to be readministered.

Finally, the roles of researchers and TSS staff in survey administration were negotiated. Because the survey included questions about use and satisfaction of TSS services, it was important for validity that administration be actioned by a third party. However, the collaborative nature of the research project and relational role of TSS with schools and students meant that administration of the T4S required TSS facilitation. Hence, a protocol was developed whereby researchers took responsibility for administration fidelity. Questions were read aloud to students and interpreted if necessary (e.g., for any younger students who did not understand the question), but leading was disallowed. TSS took responsibility for the relational and logistic aspects of engagement with students. The final draft T4S and protocols were successfully submitted to DET and university ethics committees for approval.

Phase 6: Act: Broader Piloting and Refinement

Finally, the T4S was systematically piloted using iPads in term 1 of the 2016 academic year in a randomly selected cluster of 3 boarding schools (n = 46 secondary students), 2 remote community feeder schools (n = 40 year six students), and 1 remote community (8 re-engaging students). TSS and researchers documented the administration process, and again, students were invited to provide feedback about any questions that did not make sense. In response to analysis of the pilot results, 28 questions were amended or deleted (22 of these questions which pertained to satisfaction with health and TSS services were collapsed into 2). The construct validity of the T4S was then checked using the COSMIN quality assessment tool for measurement studies (Mokkink et al., 2010).

A protocol was developed to specify a referral pathway for those students whose survey responses suggested risk of self-harm, in order to provide early support. The protocol directed researchers to provide an identified student’s code to the TSS Manager, who then identified the student and contacted the boarding school, parent/guardian, and relevant health service.

To conclude the PAR cycle and inform the start of the next cycle, the survey and pilot results were shared at a face-to-face meeting organized to inform the next phase of the research study. Feedback was invited from TSS staff, school principals and boarding staff, Cape York community Mayors and educational representatives, and project investigators/health practitioners.

Data Analysis

The interactive PAR processes were recorded and transcribed. Thematic analysis methods (Braun and Clarke, 2006) were used to identify key challenges and opportunities arising during development. Having participated in all PAR sessions, researchers were familiar with the content; however, challenges and opportunities were identified by reviewing and notating transcripts, memoing, and mind mapping to sort the concepts and identify the relationships between them. Key issues were then reviewed, refined, and named (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

Results

Four key challenges and opportunities were identified: (1) the relevance of international survey instruments for Indigenous Australian students; (2) accounting for distinct environments; (3) the balance between assessing risk and protective factors; and (4) tailoring for literacy levels and school engagement. Some key challenges occurred across several phases.

The Relevance of International Survey Instruments for Indigenous Australian Students

The targeted literature search, informed by the hypothesized outcomes identified in the logic model, produced 20 survey instruments (some with multiple variants). As well, we found TSS (DET) routinely collected information about four of the domains outlined in the program logic model (attendance and retention in secondary schooling, enhanced learning, post-school aspiration, and ability to deal with crises). We had assumed that survey instruments developed by and/or for Indigenous Australians (Schlesinger et al., 2007; Thomas et al., 2010; Haswell et al., 2013), would be the most relevant, and prioritized these instruments in our early drafts and testing with TSS staff and students. Only one instrument, Strong Souls, was developed specifically to assess Indigenous Australian adolescents’ well-being (Thomas et al., 2010). A further 13 instruments had been tested or implemented with Indigenous Australians and nine had been developed specifically for adolescents. However, the Indigenous Australian measures were considered by TSS staff, and later students, to be either of less relevance than the international questions, or too complex for young adolescents to answer through a self-administered survey instrument. For example, one staff member said the scenario questions of the Growth Empowerment Measure were “too ‘deep’ for year 7 students. A lot of preparation/trust building would be required prior.” The final T4S questions were therefore all drawn from international measurement instruments.

Accounting for Distinct Environments

Transition Support Service staff iterated a need to take account in the framing of survey questions of the distinct home community and boarding school/boarding house environments experienced by students. One TSS staff member reflected: “These students virtually have two or three lives/personas.” Examples provided during brainstorming with TSS staff and project investigators, included “being a blackfella from a remote community,” “being strong in identity,” as well as “belief TSS support is helping to achieve education.” The questions of the internationally validated Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM) were therefore framed in a way that could be tailored and allocated to sections related to experiences at home and at boarding school (Liebenberg et al., 2011).

The Balance between Assessing Risk and Protective Factors

It was also challenging to determine the right balance between questions about resilience compared to those about risk factors for self-harm. There was an understandable reluctance by TSS staff to ask sometimes vulnerable students risk-based questions, because of a potential harm to their esteem and well-being, and a reluctance to contribute to deficit-based discourses pertaining to Indigeneity more generally. One staff member noted: “If a child is upset after questions, [it’s possible that this] can have a blowout effect.” A different staff member said that they were: “Worried about asking some of these [risk questions]. Will people feel that this survey is a little presumptive?” Related to this issue was concern about the effect of historical colonial policies such as family separations on the willingness of students to answer questions accurately. In the context of Indigenous students’ experiences of intergenerational trauma, such as that engendered by the stolen generations policies, TSS staff considered that students might be unwilling to accurately respond to statements such as having plenty to eat at home and feeling safe with family. A staff member suggested: “students would say no to substance abuse and be reluctant to answer about family.” Another said it was: “Important to build a relationship with the student, and students often tell you what they think you want to hear.” There were also concerns expressed by TSS staff that they had neither the training nor skills to respond appropriately to students’ identification of risk of self-harm. One said: “What if it [the survey] brings up issues for a student that we aren’t trained to deal with?” Hence, many of the questions considered in the early drafts about life stressors, alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana were excluded; instead, the Kessler 5 psychosocial distress scale was included. No student subsequently expressed any negative concerns about answering question.

Unexpectedly, however, the majority of students in the pilot survey administration responded affirmatively to the concluding T4S question offering an option to talk with someone about a well-being issue. The general nature of this question created uncertainty as to whether students had a personal well-being issue of concern, or perhaps just wanted to talk about well-being in general. The question was subsequently amended for improved clarity of meaning.

Tailoring for Literacy Levels and School Engagement

Piloting of the T4S with older students suggested that the literacy level was appropriate, but younger students required explanation of complex concepts and struggled to complete the draft T4S. A youth mentor suggested of complex concepts: the “survey could be turned into a group discussion/workshop.” Another youth mentor commented: “22 questions is a long enough survey.” Student feedback suggested that some questions were repetitive, others were in an inappropriate order, and that there was value in simplifying the literacy level of the survey even further. A second, simplified version of the T4S with a 3-point rating scale was developed for primary school (year 6) students. Additionally, the questions in the boarding school section of the secondary school T4S were inappropriately framed for those students who had been excluded from schools. A third version was therefore developed to account for the past experiences at boarding school of students who had been de-enrolled and were back in their home communities awaiting re-engagement in another school or educational pathway; this version also included a 3-point scale.

The Resultant Survey Instrument

The six-phased development process resulted in a tailored survey instrument to identify Indigenous students’ resilience and risk factors for self-harm. The final boarding school T4S comprised 4 demographic and 56 resilience, risk, and service use and satisfaction questions. The year 6 T4S comprised 5 demographic and 51 resilience, risk, and service use and satisfaction questions. The re-engagement T4S comprised 5 demographic and 59 resilience, risk, and service use and satisfaction questions. The final T4S questions were consistent with the hypothesized student outcomes of enhanced TSS support, initially outlined in the program logic model (Table 1).

Results of the pilot T4S administration for year 6, secondary boarding, and re-engagement students are reported elsewhere (Redman-MacLaren et al., 2017). The final T4S instrument will be administered to further cohorts of TSS-supported students at randomly selected schools from 2017.

Discussion

This paper examined the design, development, and piloting of a tailored survey for routine administration. The survey aimed to assess students’ self-reported resilience and exposure to risk of self-harm in order to appropriately target, prioritize, and improve TSS student support. A strength of the T4S lies in its synthesis of the perceptions of service providers and users through its co-creation through PAR. Survey development started in a routine manner with researchers searching the literature and identifying routine data. By reflecting and building on what we learned from successive PAR cycles with TSS staff, project investigators, and students, we were able to test small changes in its development sequentially and detect and amend design problems early. Each phase built on the findings of former steps, allowing the survey to be tailored for the boarding school and remote community contexts, address relevant well-being issues, and be delivered in ways appropriate to the literacy levels of the students. The final questions fit well together to comprehensively reflect the constructs of resilience and risk being measured. National policy highlights the importance of tailored measures for local Indigenous resilience and self-harm risk. However, given the complexity of survey development processes, concomitant resourcing to support their development is needed.

Although there is a range of survey instruments available internationally to measure resilience and risk, our literature search, and workshops suggested that the instruments are rarely or inconsistently used to inform the decision making of education and health services (Kinchin et al., 2017). This might be because of a reluctance by education and health professionals to ask risk-based questions because of valid fears about students’ vulnerability, such as we found in this study. But the willingness of students to answer these questions suggested that concerns may be related more to staff anxiety rather than student sensitivity. The reluctance by services to measure resilience and risk might also be caused by the difficulties and resource requirements of conducting intervention research in Indigenous health (Sanson-Fisher et al., 2006; Paul et al., 2010), concern that the service may not have the capacity to manage the potentially high level of risk reported in surveys, or concern that international survey instruments might not be relevant for application with Indigenous populations. We found that, if developed collaboratively with Indigenous services and tested with local Indigenous participants, internationally validated measures can be useful for determining Indigenous resilience and risk and should not be ignored.

The reliability of the T4S is assured by use of the internationally validated CYRM (Liebenberg et al., 2012, 2013; Daigneault et al., 2013) and Kessler scales (Kessler et al., 2002; Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013), as well as reliability tests on the pilot results. Incorporation of the CYRM-28 meant that all important aspects of the construct of resilience were covered. Some constructs of upstream risk factors might have been missed because of the decisions made about removing these. However, the participatory process provided confidence that the final questions measured the intended constructs and resulted in an instrument that identified the critical self-harm risk and protective factors. The result of the collaborative dialog and reflective learning by people of diverse backgrounds and interests through PAR (Mayo et al., 2009; Crane and O’Regan, 2010; Bainbridge et al., 2011) thus promoted development of an optimal survey instrument for the local context and participants.

The T4S was developed in response to TSS service delivery needs, and the collaborative approach resulted in direct translation of the pilot results to inform quality improvements in TSS student support. For example, in the absence of other data availability, the identified high levels of students’ psychosocial distress and exposure to life stressors also prompted TSS and the regional Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Service to improve the integration of their services. Similarly, the result of students’ strong positive feelings about family, community, and culture was identified as a strength upon which TSS could support more robust linkages between boarding schools and families. Further implementation of the T4S will determine whether strategies developed in response to the pilot T4S results will translate into higher levels of students’ resilience and reductions in their psychosocial distress scores. These examples of impact provide support for the value of locally developed survey instruments.

Limitations of our design methodology include the limited sample sizes for the T4S results, which have not yet been large enough to publish. Further, each phase of development could have been more extensive and rigorous but was limited by the resource constraints of both TSS and the research project. For example, TSS and research resources were required to obtain informed consent from parents/caregivers across 11 remote communities. That all parents gave consent reflects the tenacity and strong relationships forged by TSS staff with parents/caregivers, and parental concerns that their children are supported in the best ways possible during their transitions to boarding schools. Finally, the T4S relies on self-reported subjective resilience and risk measures from children as young as 10 years old. We are cautiously optimistic, however, that these children’s responses are valid despite their age, given results from other international studies. For example, a United Kingdom measure of child and adolescent well-being considered the realistic minimum age for asking children subjective well-being questions as 8 years old (Joloza, 2013).

Conclusion

While national policy measures outline the importance of tailored community-based Indigenous resilience and self-harm prevention programs, there is a lack of localized data to determine the level of resilience or risk among population groups, or whether or not programs work. Yet, as this paper describes, the rigorous development of tailored survey instruments is complex and time consuming, indicating a policy gap in concomitant resourcing to support such processes. This paper provides a guide for other practitioners and researchers as to the phases required in collaboratively designing, developing, and piloting a tailored survey instrument to identify Indigenous students’ resilience and risk, and the issues that arose through the process of development. The required six phases are likely to be common to the collaborative development of other surveys. The T4S was developed in response to service delivery needs for a specific localized context and resulted in direct translation of the pilot results to education and health workforces. It can be adapted for other populations of Indigenous adolescent and is likely to be generalizable to other Indigenous well-being and/or self-harm prevention programs.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of James Cook University Ethics Committee, Central Queensland University Ethics Committee, and Education Queensland Ethics ommittee. All participants gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by Central Queensland University and Education Queensland Ethics Committees.

Author Contributions

JM conceived and designed the paper, carried out the thematic analysis of survey development issues, and drafted the manuscript. RB, MR-M, and KT provided critical analysis of the first draft of the manuscript. RB, MR-M, SR, KR, KT, MU, MW, and EH contributed to data interpretation and revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content. All the authors read, approved, and agreed to be accountable for the content of the work.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of other TSS staff members, students, and project investigators.

Funding

This research study was funded by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) project grant 1076774 and early career fellowship APP1113392. The contents of the published material are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the views of NHMRC.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/feduc.2017.00019/full#supplementary-material.

References

Abonyi, S., Lidguerre, T., Anthony, B., Stylianidou, S., and Jeffery, B. (2013). Are we measuring the right things in the right ways? Local perspectives on the influence of the environment on community health in northern Saskatchewan, Canada. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 72(Suppl. 1), 1002–1004. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v7210.22447

Anderson, I., Robson, B., Connolly, M., Al-Yaman, F., Bjertness, E., King, A., et al. (2016). Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health (The Lancet; Lowitja Institute Global Collaboration): a population study. Lancet. 388, 131–157. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00345-7

Antonio, M. C. K., and Chung-Do, J. J. (2015). Systematic review of interventions focusing on Indigenous adolescent mental health and substance use. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 22, 36–56. doi:10.5820/aian.2203.2015.36

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2006). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) (Vol. Cat No 4715.0). Canberra: ABS.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2009). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (Vol. ABS Cat. No. 4714.0). Canberra: ABS.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013). Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Users’ Guide, 2012-13. Canberra: ABS. Available at: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4727.0.55.002Chapter3602012-13

Bainbridge, R., McCalman, J., Tsey, K., and Brown, C. (2011). Inside-out approaches to promoting Aboriginal Australian wellbeing: evidence from a decade of community-based participatory research. Int. J. Health Wellness Soc. 1, 13–27. doi:10.18848/2156-8960/CGP/v01i02/41165

Bainbridge, R., McCalman, J., and Whiteside, M. (2013a). Being, knowing and doing: a phronetic approach to constructing grounded theory with Indigenous partners. Qual. Health Res. 23, 275–288. doi:10.1177/1049732312467853

Bainbridge, R., Tsey, K., Andrews, R., McCalman, J., and Brown, C. (2013b). Managing top-down change with bottom-up leadership: developing a social and emotional wellbeing action framework with a discrete Aboriginal community. J. Aust. Indigenous Issues 16, 2–20.

Bainbridge, R., Tsey, K., McCalman, J., Kinchin, I., Saunders, V., Watkin Lui, F., et al. (2015). No one’s discussing the elephant in the room: contemplating questions of research impact and benefit in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. BMC Public Health 15:696. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2052-3

Bergold, J., and Thomas, S. (2012). Participatory research methods: a methodological approach in motion. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 13, 1–12.

Bishop, R. (2005). “Freeing ourselves from neo-colonial domination in research: a Maori approach to creating knowledge,” in Handbook of Qualitative Research, eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 109–138.

Blythe, T., Allen, D., and Powell, B. S. (1999). Looking Together at Student Work. New York: Teachers’ College Press.

Bodkin-Andrews, G., O’Rourke, V., and Craven, R. G. (2010). The utility of general self-esteem and domain-specific self-concepts: their influence on Indigenous and non-Indigenous students’ educational outcomes. Australian J. Educ. 54(3):Article 4.

Booth, M., Hill, G., Moore, M., Dalla, D., Moore, M., and Messenger, A. (2016). The new Australian Primary Health Networks: how will they integrate public health and primary care? Public Health Res. Pract. 26, e2611603. doi:10.17061/phrp2611603

Brady, M., Sibthorpe, B., Bailie, R., Ball, S., and Sumnerdodd, P. (2002). The feasibility and acceptability of introducing brief intervention for alcohol misuse in an urban Aboriginal medical service. Drug Alcohol Rev. 21, 375–380. doi:10.1080/0959523021000023243

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brener, L., Wilson, H., Jackson, L. C., Johnson, P., Saunders, V., and Treloar, C. (2015). The role of Aboriginal community attachment in promoting lifestyle changes after hepatitis C diagnosis. Health Psychol. Open 2, 2055102915601581. doi:10.1177/2055102915601581

Commonwealth of Australia. (2013). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention Strategy. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, 48.

Crane, P., and O’Regan, M. (2010). On PAR. Using Participatory Action Research to Improve Early Intervention. Canberra: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, Australian Government. Available at: https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/05_2012/reconnect_0.pdf

Daigneault, I., Dion, J., Hébert, M., McDuff, P., and Collin-Vézina, D. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM-28) among samples of French Canadian youth. Child Abuse Negl. 37, 160–171. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.06.004

Daniel, M., Brown, A., Dhurrkay, J. G., Cargo, M. D., and O’Dea, K. (2006). Mastery, perceived stress and health-related behaviour in northeast Arnhem Land: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Equity Health 5, 10. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-5-10

De Maio, J., Zubrick, S., Silburn, S., Lawrence, D., Mitrou, F., Dalby, R., et al. (2005). The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: Measuring the Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal Children and Intergenerational Effects of Forced Separation. Perth: Curtin University of Technology and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research.

Denzin, N. (2007). “Grounded theory and the politics of interpretation,” in The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory, eds A. Bryant and K. Charmaz (London: SAGE), 454–471.

Dockery, A. M. (2011). Traditional Culture and the Wellbeing of Indigenous Australians: An Analysis of the 2008 NATSISS. Perth: Centre for Labour Market Research, Curtin University.

Eley, D., Hunter, K., Young, L., Baker, P., Hunter, E., and Hannah, D. (2006). Tools and methodologies for investigating the mental health needs of Indigenous patients: it’s about communication. Australas. Psychiatry 14, 33–37. doi:10.1080/j.1440-1665.2006.02235.x

Garvey, D. (2008). Review of the social and emotional wellbeing of Indigenous Australian peoples – considerations, challenges and opportunities. Available at: http://www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/sewb_review

Gee, G., Dudgeon, P., Schultz, C., Hart, A., and Kelly, K. (2014). “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing,” in Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, eds P. Dudgeon, H. Milroy, and R. Walker. 2nd Edn (Canberra: Department of The Prime Minister and Cabinet), 55–68.

Goodyear-Smith, F., Coupe, N. M., Arroll, B., Elley, C. R., Sullivan, S., and McGill, A.-T. (2008). Case finding of lifestyle and mental health disorders in primary care: validation of the ‘CHAT’ tool. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 58, 26–31. doi:10.3399/bjgp08X263785

Haswell, M. R., Kavanagh, D., Tsey, K., Reilly, L., Cadet-James, Y., Laliberte, A., et al. (2010). Psychometric validation of the Growth and Empowerment Measure (GEM) applied with Indigenous Australians. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 44, 791–799. doi:10.3109/00048674.2010.482919

Haswell, M. R., Wargent, R., Tulip, F., Wheeler, T., Brownlie, A., Baird, M., et al. (2013). Validation and enhancement of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander psychiatric hospitalisation statistics through an Indigenous Mental Health Worker Register. Rural Remote Health 13, 2002.

Hunter, E., and Milroy, H. (2006). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander suicide in context. Arch. Suicide Res. 10, 141–157. doi:10.1080/13811110600556889

Jellinek, M., Murphy, J., Little, M., Pagano, M. E., Comer, D. M., and Kelleher, K. J. (1999). Use of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC) to screen for psychosocial problems in pediatric primary care: a national feasability study. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 153, 254–260. doi:10.1001/archpedi.153.3.254

Joloza, T. (2013). Review of Available Sources and Measures for Children and Young People’s Well-being. Newport, NSW: Office for National Statistics, UK Statistics Authority.

Kessler, R., Andrews, G., Colpe, L., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D., Normand, S., et al. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 32, 959–976. doi:10.1017/S0033291702006074

Kinchin, I., McCalman, J., Bainbridge, R., Tsey, K., and Watkin Lui, F. (2017). Does indigenous health research have impact? A systematic review of reviews. Int. J. Equity Health 16:52. doi:10.1186/s12939-017-0548-4

Kowal, E., Gunthorpe, W., and Bailie, R. S. (2007). Measuring emotional and social wellbeing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations: an analysis of a Negative Life Events Scale. Int. J. Equity Health 6, 18. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-6-18

Liebenberg, L., Ikeda, J., and Wood, M. (2015). “It’s just part of my culture”: understanding language and land in the resilience processes of Aboriginal youth,” in Youth Resilience and Culture, eds L. Theron, L. Liebenberg, and M. Ungar (Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer), 105–116.

Liebenberg, L., Ungar, M., and LeBlanc, J. C. (2013). The CYRM-12: a brief measure of resilience. Can. J. Public Health 104, 5. doi:10.17269/cjph.104.3657

Liebenberg, L., Ungar, M., and Van de Vijver, F. (2011). Validation of the Child and Youth Resilience Measure-28 (CYRM-28) among Canadian youth. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 1, 24–27. doi:10.1177/1049731511428619

Liebenberg, L., Ungar, M., and Vijver, F. V. D. (2012). Validation of the Child and Youth Resilience Measure-28 (CYRM-28) among Canadian youth. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 22, 219–226. doi:10.1177/1049731511428619

Mayo, K., Tsey, K., McCalman, J., Whiteside, M., Fagan, R., and Baird, L. (2009). The research dance: university and community research collaborations at Yarrabah, North Queensland, Australia. Health Soc. Care Community 17, 133–140. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00805.x

Metalsky, G., and Joiner, T. (1997). The hopelessness depression symptom questionnaire. Cognit. Ther. Res. 21, 359–384. doi:10.1023/A:1021882717784

Mokkink, L. B., Terwee, C. B., Knol, D. L., Stratford, P. W., Alonso, J., Patrick, D. L., et al. (2010). The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 10:22. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-10-22

National Health and Medical Research Council. (2010). NHMRC Roadmap II: A Strategic Framework for Improving the Health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People Through Research. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Patrick, J., Dyck, M., and Bramston, P. (2010). Depression Anxiety Stress Scale: is it valid for children and adolescents? J. Clin. Psychol. 66, 996–1007. doi:10.1002/jclp.20696

Paul, C., Sanson-Fisher, R., Stewart, J., and Anderson, A. (2010). Being sorry is not enough. The sorry state of the evidence base for improving the health of Indigenous populations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 38, 566–568. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.02.001

Redman-MacLaren, M. L., Klieve, H., McCalman, J., Russo, S., Rutherford K., Wenitong, M., and Bainbridge, R. G. (2017). Measuring resilience and risk factors for the psychosocial well-being of aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Boarding school students: pilot baseline study results. Front. Educ. 2:5. doi:10.3389/feduc.2017.00005.

Sanson-Fisher, R. W., Campbell, E. M., Perkins, J. J., Blunden, S. V., and Davis, B. B. (2006). Indigenous health research: a critical review of outputs over time. Med. J. Aust. 184, 502–505.

Schlesinger, C., Ober, C., McCarthy, M., Watson, J., and Seinen, A. (2007). The development and validation of the Indigenous Risk Impact Screen (IRIS): a 13-item screening instrument for alcohol and drug and mental health risk. Drug Alcohol Rev. 26, 109–117. doi:10.1080/09595230601146611

Searles, A., Doran, C., Attia, J., Knight, D., Wiggers, J., Deeming, S., et al. (2016). An approach to measuring and encouraging research translation and research impact. Health Res. Policy Syst. 14, 60. doi:10.1186/s12961-016-0131-2

Searles, A., McCalman, J., Tsey, K., Doran, C., and Shakeshaft, A. (2012). Evaluating Health Initiatives in Cape York Indigenous Communities. Cairns, Newcastle: Hunter Medical Research Institute.

Semaili, L. M., and Kincheloe, J. L. (1999). “Introduction: what is Indigenous knowledge and why should we study it?” in What is Indigenous Knowledge: Voices from the Academy, eds L. M. Semaili and J. L. Kincheloe (New York: Falmer Press), 3–57.

Shand, F. L., Ridani, R., Tighe, J., and Christensen, H. (2013). The effectiveness of a suicide prevention app for indigenous Australian youths: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 14, 396–396. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-14-396

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books Ltd.

Thomas, A., Cairney, S., Gunthorpe, W., Paradies, Y., and Sayers, S. (2010). Strong souls: development and validation of a culturally appropriate tool for assessment of social and emotional well-being in Indigenous youth. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 44, 40–48. doi:10.3109/00048670903393589

Thomas, D., Bainbridge, R., and Tsey, K. (2014). Changing discourses in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research 1914–2014. Med. J. Aust. 201(1 Suppl.), S15–S18. doi:10.5694/mja14.00114

Tsey, K., Lawson, K., Kinchin, I., Bainbridge, R., McCalman, J., Watkin, F., et al. (2016). Evaluating research impact: the development of a research for impact tool. Front. Public Health 4:160. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00160

Ungar, M., Brown, M., Liebenberg, L., Othman, R., Kwong, W., Armstrong, M., et al. (2007). Unique pathways to resilience across cultures. Adolescence 42, 287–310.

Ungar, M. (2011). The social ecology of resilience. Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry, 81, 1–17.

Wadsworth, Y. (1998). What is participatory action research. Action Res. Int. Available at: http://www.scu.edu.au/schools/gcm/ar/ari

Wong, W. S., Fielding, R., Wong, C. M., and Hedley, A. J. (2008). Psychometric properties of the nine-item Chinese Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (ChPSQ-9) in Chinese patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Psychooncology 17, 292–299. doi:10.1002/pon.1247

Zubrick, S., Dudgeon, P., Gee, G., Glaskin, B., Kelly, K., Paradies, Y., et al. (2010). “Social determinants of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing,” in Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, eds N. Purdie, P. Dudgeon, and R. Walker (Barton: ACT: Commonwealth of Australia), 75–90.

Appendix

Keywords: youth, adolescent, well-being, resilience, mental health, measurement, Indigenous

Citation: McCalman J, Bainbridge RG, Redman-MacLaren M, Russo S, Rutherford K, Tsey K, Ungar M, Wenitong M and Hunter E (2017) The Development of a Survey Instrument to Assess Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students’ Resilience and Risk for Self-Harm. Front. Educ. 2:19. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00019

Received: 11 December 2016; Accepted: 27 April 2017;

Published: 24 May 2017

Edited by:

Colette Joy Browning, RDNS Institute, AustraliaReviewed by:

Stacie Craft DeFreitas, University of Houston at Downtown, USAMarianne Cockroft, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA

Copyright: © 2017 McCalman, Bainbridge, Redman-MacLaren, Russo, Rutherford, Tsey, Ungar, Wenitong and Hunter. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Janya McCalman, ai5tY2NhbG1hbkBjcXUuZWR1LmF1

Janya McCalman

Janya McCalman Roxanne Gwendalyn Bainbridge

Roxanne Gwendalyn Bainbridge Michelle Redman-MacLaren

Michelle Redman-MacLaren Sandra Russo4

Sandra Russo4 Komla Tsey

Komla Tsey Mark Wenitong

Mark Wenitong