- 1QUT Design Lab, School of Design, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 2School of Architecture and Built Environment, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Emerging from the social disparities of the COVID-19 pandemic and contestations over marginal bodies in space during the global Black Lives Matter movement, Radical Placemaking is proposed as a digital placemaking design practice and investigated as part of a 3-year design study. This practice involves marginalized bodies highlighting social issues through the ephemerality and spectacularity of digital technologies in public space in [smart] cities. Radical Placemaking methodology, as demonstrated through three design interventions, engages participatory action research, slow design, and open pedagogies for marginal bodies to create place-based digital artifacts. Through the making and experience of the artifacts, Radical Placemaking advances and simulates a virtual manifestation of the marginal beings' bodies and knowledge in public spaces, made possible through emerging technologies. Through nine key strategies, the paper offers a conceptual framework that imbibes a relational way of co-designing within the triad of people-place-technology.

1. Introduction

“All paradises, all utopias are designed by who is not there, by the people who are not allowed in.”—Toni Morrison (Morrison, 1998).

This work emerges from disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic and social movements such as Black Lives Matter (BLM) where racialized bodies faced economic, racial, and health disparities (Devlin, 2020), ongoing police brutality, and, in Australia, Blak1 deaths in custody (Henriques-Gomes and Visontay, 2020). BLM also brought to the forefront the new contestations over histories of the USA, UK, and Australia as seen in the colonial statues in public spaces (Slessor and Boisvert, 2020): the statues serve as a reminder of suppression, erasure, and continuous reminders of colonial brutality on the colonial subject, the other (Spivak, 2010). These movements represent the growing need for counter-narratives (Milner and Howard, 2013), that is, other narratives of places and their history. In this paper, we share some of our experiences and reflections on employing Radical Placemaking as a praxis to lead an activist-driven agenda of creating counter-narratives through digital placemaking. Rather than reporting empirical findings from data analysis, these reflections are summative and synthesize our experience from leading three Radical Placemaking projects.

The spaces that have assigned meaning and attachment within the dimensions of the human experience are termed places (Graham, 2014). The civic and community-driven process that involves the conversion of spaces into places, particularly public spaces, is termed placemaking (Project for Public Spaces, 2007) and is imagined as a democratic and inclusionary process. However, this effectively top-down process remains exclusionary (Harvey, 2012), having a role to play in gentrification, breakdown of social networks (Atkinson, 2000), and spatial inequality (Sutton and Kemp, 2011). But, most importantly, in the ongoing dispossession of land associated with terra nullius, that is, the colonists' justification for “empty” land as being “nobody's land” (Moreton-Robinson, 2020), the placemaking process often ignores the existing use and history of places (Burns and Berbary, 2021). Despite the ways that citizens and their histories are excluded in the top-down process of placemaking, citizens activate their right to the city through tactics such as pop-up events, street festivals, guerrilla and community gardening, graffiti/street art, skateboarding, and parkour (Iveson, 2013; Houghton et al., 2015; Lydon and Garcia, 2015; Foth, 2017). While enabling belonging, citizenship, and making of the city (Lepofsky and Fraser, 2003; Barry and Agyeman, 2020), these interventions offer another vision of the city (Lashua, 2013). However, these urban imaginaries remain subject to temporality with minimal traces and subject to the institution (Estrada-Grajales et al., 2018).

Information and communication technology offers another way to navigate this temporality and bureaucracy. Beyond the urban complaint modality of the smartphone in the form of Boston 311 and Citizen Connect phone apps (Foth et al., 2011; Lehner et al., 2014), technology offers a modality for place-based activism. For example, the temporary media architecture of urban screens took on messages of those affected by the ongoing gentrification of parts of London in the “London is Changing” project (Caldwell and Foth, 2014). While media architecture interventions tend to require access guaranteed by expertise and/or monetary value, it offers replicability through the digital and spectacularity in pixels. Even the small media screen of the smartphone, as seen in the popular pervasive game Pokémon Go, presents possibilities for place-specific and activist-driven urban experiences (Paavilainen et al., 2017; Low et al., 2022). The game, which inserted digital Pokémon characters for players to capture within the urban environment, allowed players to make loose social connections (Vella et al., 2019), engage in memory-making within the public space (Mejeur, 2019), enabled the discovery of urban places (Colley et al., 2017), and accentuated health benefits for players through walking (LeBlanc and Chaput, 2017). However, Pokémon Go replicated spatial inequality by leading players toward affluent neighborhoods (Layland et al., 2018), did not emphasize strong narratives of place (Hjorth and Richardson, 2017), and offered players limited opportunities to create unique experiences of “Pokémon Go” (Wang and Kuo, 2018).

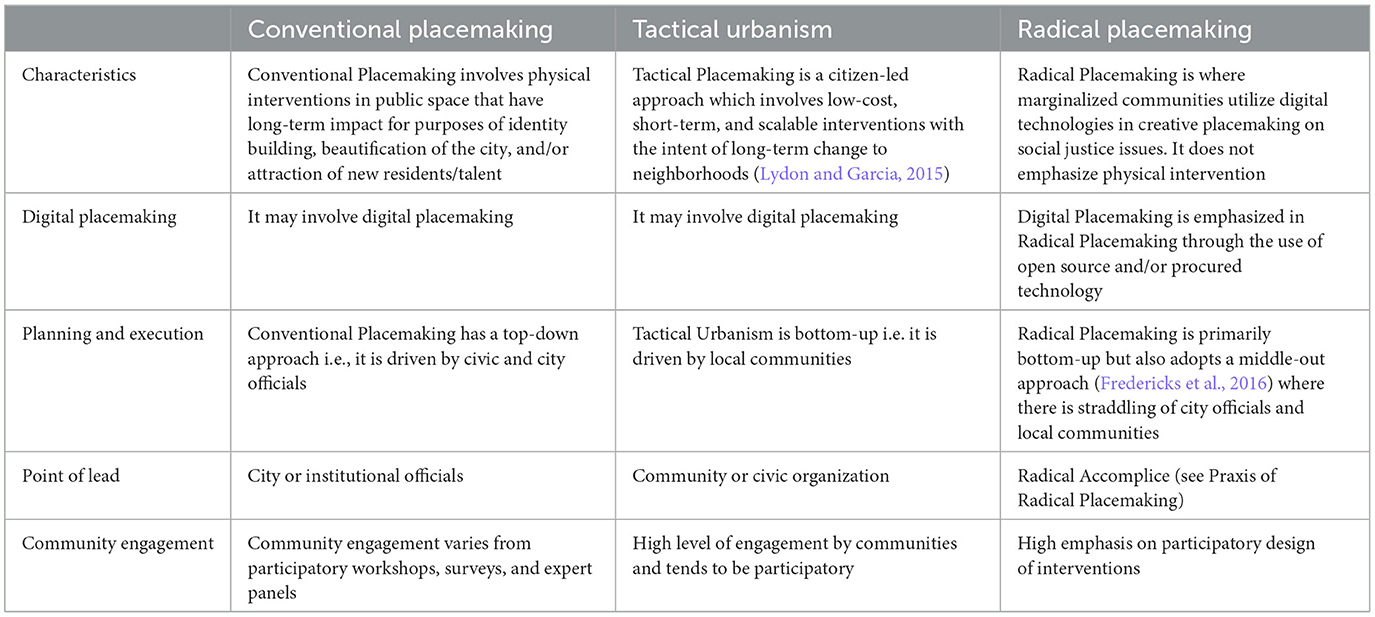

Bearing in mind these limitations of Pokémon Go, this paper presents the promise of Radical Placemaking (Table 1): It considers the possibilities of digital placemaking for building connections to place (Tuan, 1991), construction of other realities (Bruner, 1991), and prospects of community care, healing, and empowerment (Rappaport and Simkins, 1991). As a step away from colonial structures of design thinking and methodologies (Akama et al., 2019), Radical Placemaking engages marginalized communities in designing and utilizing digital tools to “occupy” the city with an emphasis on social justice and place-based activism (Gonsalves et al., 2021b). Positioning Radical Placemaking in literature and theory, the next section explores some of the challenges that lie at the intersections of placemaking, participatory action research, marginalization, and the potential of creative technologies. This is followed by our reflections on the impact of employing Radical Placemaking as demonstrated through three hybrid digital-physical design interventions that took place during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brisbane, Australia: the Chatty Bench Project (Gonsalves et al., 2021c), TransHuman Saunter (Gonsalves et al., 2022b), and the Chatty Bench Festival Community Media Visual Projections (Gonsalves, 2021). The article aims to contribute to further academic discussion on the community-driven design practice of digital placemaking and its radicality, how community members are to be engaged in radical placemaking, and the emergent outcomes of the radical placemaking process. It concludes by speculating on the future of radical placemaking. This paper's concept and speculations address the themes of “Combining digital and non-digital co-design and participatory design tools for scaling up participation” and “Prototyping tools for city professionals and citizens to co-create the city” of the Frontiers in Computer Science special issue on “Scaling Up Co-creation in the Smart and Social City: New Approaches to Diversify and Expand Participation.”

Table 1. An overview of the differences and the challenges of traditional placemaking, tactical urbanism, and radical placemaking.

2. Examples of radical placemaking

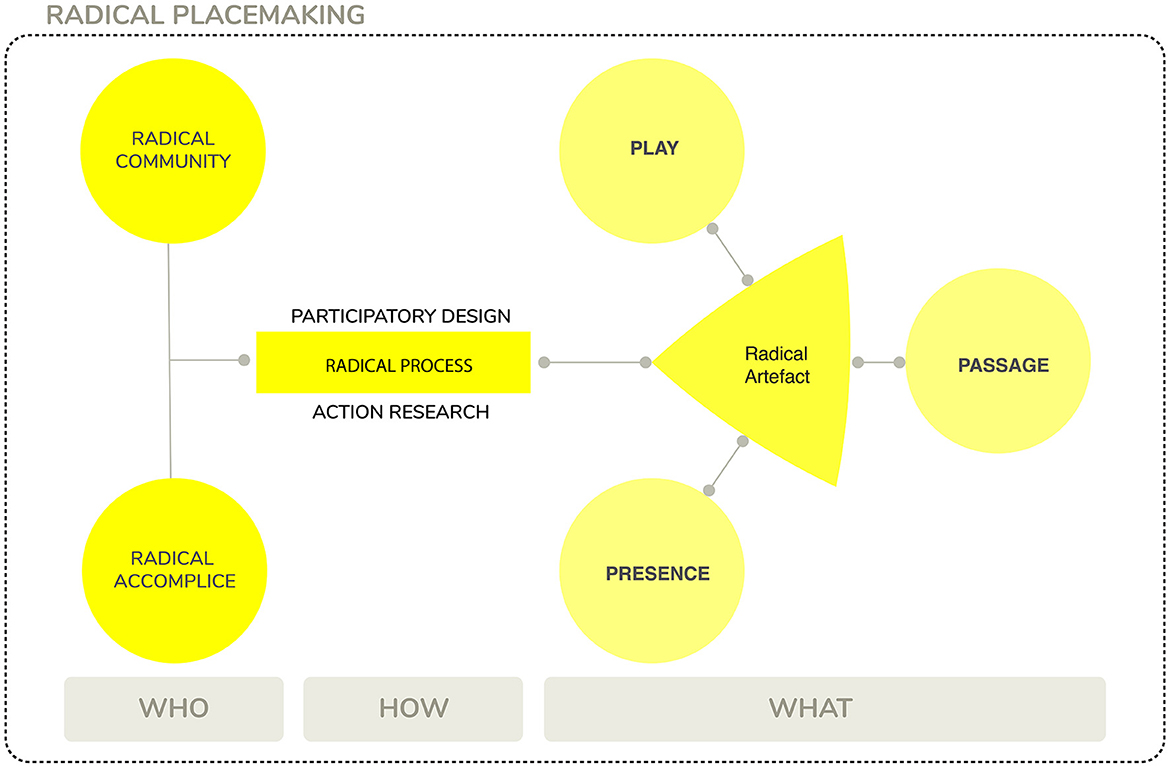

While commentators have acknowledged the radical premise of placemaking (Foth et al., 2016; Courage, 2020), conventional placemaking often lacks radical aspirations. Radical Placemaking (Figure 1) is a tactic where those who experience marginalization utilize digital tools to engage in place-based activism (Gonsalves et al., 2020). It is “radical” as it builds on (i) Freire's pedagogy of the oppressed where the marginalized lead the creation and deployment of their digital artifact (Freire, 2000); (ii) Ledwith's radical approach to community development with a focus on social and environmental issues (Ledwith, 2007); and (iii) a radical departure from institutional placemaking processes encouraging the marginalized to occupy the hybrid digital-physical environments with the aid of digital technology. Potentially complementary approaches include situated practices utilized by community activism groups (Monno and Khakee, 2012; Boyd and Mitchell, 2013; Foth et al., 2015; Vlachokyriakos et al., 2016; Estrada-Grajales et al., 2018).

For us, for a placemaking practice to become radical, we argue that several key elements and considerations must be at play. While the specific requirements may vary depending on the context and goals of the praxis, some common aspects that contribute to a placemaking practice being considered radical include:

1. Challenging power structures: A radical placemaking practice seeks to challenge existing power structures and dynamics within the community and the decision-making processes related to the built environment. It questions the dominant narratives and traditional modes of urban planning and design, advocating for more equitable and inclusive approaches.

2. Community empowerment: Radical placemaking places a strong emphasis on empowering communities to actively participate in the decision-making and transformation of their own spaces. It values local knowledge, fosters collaboration, and ensures that community members have a meaningful voice in shaping their environments.

3. Inclusivity and social justice: Radical placemaking praxis strives to address social inequities and promote social justice within the built environment. It aims to create inclusive spaces that cater to the needs and aspirations of all community members, particularly those who have been historically marginalized or excluded.

4. Disruption and alternative narratives: Radical placemaking challenges the status quo by introducing alternative narratives and perspectives about place and space. It seeks to disrupt conventional notions of design and planning, encouraging innovative and unconventional approaches that can lead to transformative change.

5. Critical inquiry and reflection: Radical placemaking praxis involves critical inquiry and reflection on the social, cultural, economic, and political dimensions of place. It encourages a deep understanding of the underlying issues and encourages critical thinking to drive meaningful action and change.

6. Engagement with grassroots movements and activism: Radical placemaking often involves collaboration with grassroots movements and activist groups that are working toward social change. It aligns with their goals and supports their efforts to transform public spaces and challenge systemic injustices.

7. Long-term sustainability and resilience: Radical placemaking considers the long-term sustainability and resilience of the interventions and transformations. It aims to create lasting impacts by addressing environmental concerns, promoting sustainable practices, and fostering a sense of ownership and stewardship within the community.

Radical Placemaking defines a process that includes the who, how, and what. The who are the stakeholders within radical placemaking. They consist of a radical community, that is, the community that engages in radical placemaking and the radical accomplice. The radical accomplice supports the radical community with the development of the digital artifacts, utilizes technical know-how, and facilitates the dialogue and placemaking process within the radical community, that is the main researcher in this study. The “accomplice” is immersed in the community, the ensuing work, and its challenges (Powell and Kelly, 2017). The how refers to the participatory design process that the community engages in learning and employing digital tools to develop the digital artifact. In this process, participants are partners in the research process with the researchers and championed as domain experts in the design process (Duarte et al., 2018). The what refers to marginalized communities' digital placemaking strategies, which include smartphone-based apps and use of urban screens and visual projections to engage in social justice activism.

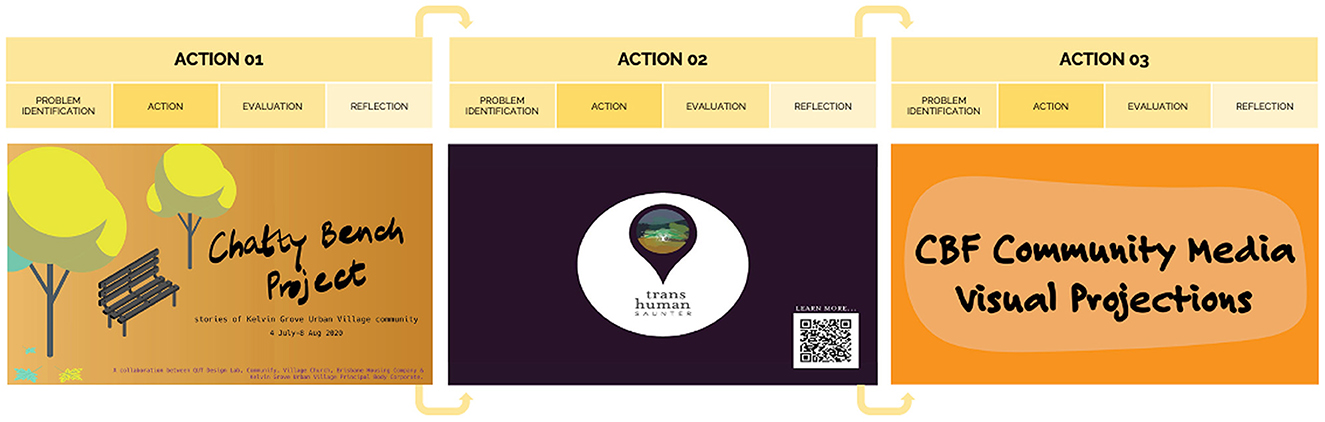

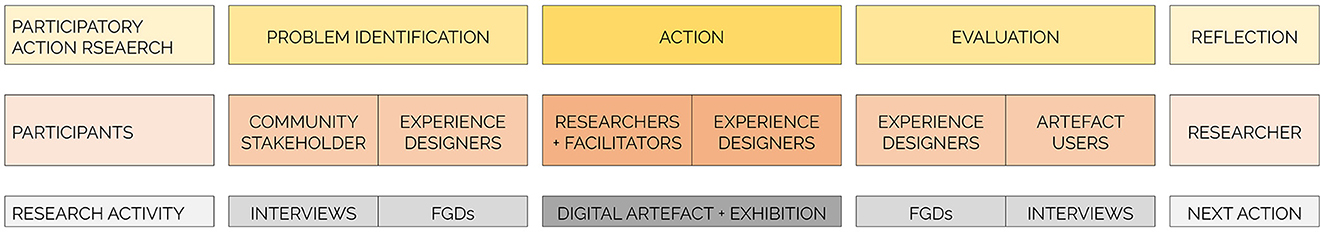

Using this process, three Radical Placemaking design interventions took place during the COVID-19 pandemic: The Chatty Bench Project (CBP), TransHuman Saunter (THSP), and the Chatty Bench Festival Community Media Visual Projections (CBF CMVP). In line with objectives of radical placemaking, the projects were developed in the problem definition-action-evaluation-reflection cycles of participatory action research methodology (Foth and Brynskov, 2016). All the participants engaged in creation of digital artifacts (web-based applications and digital media) and are referred to as experience-designers in the article (Gonsalves et al., 2020). As they create, their engagement requires higher levels of creativity i.e. the making and creating of the digital artifact (Sanders, 2006). Those who experience the artifacts as part of a showcase or exhibition and were interviewed as part of the research process are referred to as artifact-users. All projects gained University Ethical clearance; written consent from all experience-designers and artifact-users was procured for all research activities. Most research activities such as interviews and most workshops took place online and were recorded via the Zoom online tele-conferencing tool. The videos of the recordings serve as a record and audio recording was transcribed via Otter.ai, an online transcription tool. Textual data underwent thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2019) with an emphasis on looking for patterns on the participatory process and ethos, roles of the participants, and the outcomes of the radical placemaking projects.

The critical reflections presented in this paper arise from a three-year program of research into Radical Placemaking. Other publications arising from this work include (i) the initial framework of Radical Placemaking and the ethos surrounding the first project, CBP (Gonsalves et al., 2020); (ii) a detailed account of the methodology in the use of immersive technologies and initial findings of CBP (Gonsalves et al., 2021b); (iii) a discussion of the findings of CBP based on the interview data of those who participated in the Radical Placemaking process (Gonsalves et al., 2022a); (iv) an account of the use of design probes within the placemaking process during the pandemic (Slingerland et al., 2022); and (v) the methodology and initial findings of THSP (Gonsalves et al., 2022b). This paper is a summative reflection and synthesis of our experience and learnings from conducting these three Radical Placemaking projects. It also comments on the metamorphosis of the praxis of Radical Placemaking during this process. By way of situating the projects and offering context, we now turn to describing the three design interventions (Figure 2).

2.1. Chatty Bench project

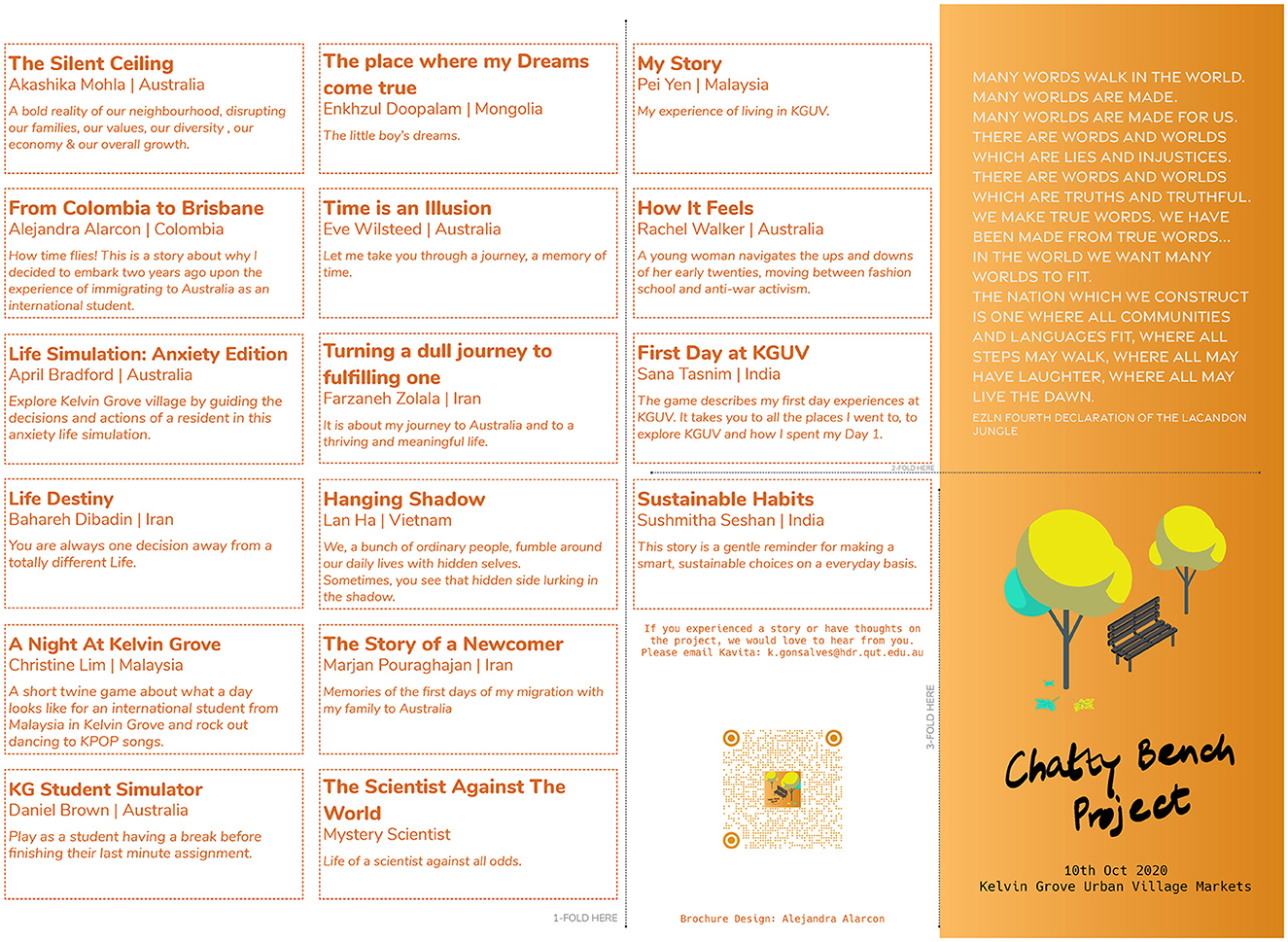

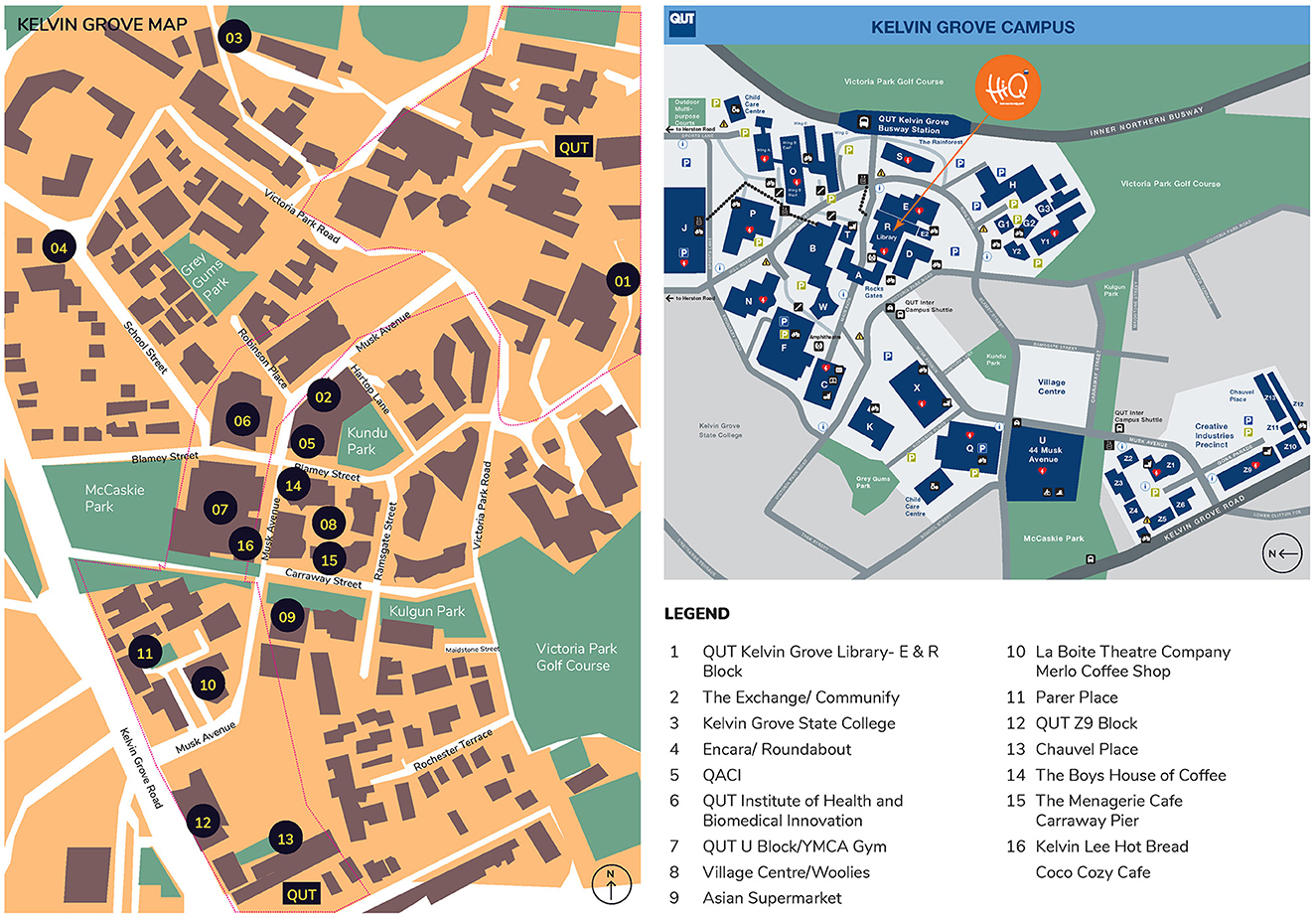

CBP is a situated, digital storytelling project conducted in the Kelvin Grove Urban Village (KGUV), Brisbane, Australia as a collaboration between the QUT Design Lab, local community organization Communify, and the KGUV Principal Body Corporate (Gonsalves et al., 2021b). It involved 16 KGUV experience-designers of varied racial and professional backgrounds creating KGUV-based digital stories on topics such as anxiety, domestic violence, and human migration for smartphones. To make the digital stories (Figure 3), they learnt Twine's coding language, embedded digital media such as audio and video into their stories, and utilized the geolocation API in Twine to make the stories place-based (Figure 4). The project was run completely online for ten weeks from July-October 2021 as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and ended with a face-to-face exhibition during community markets when COVID-19 restrictions eased to allow for group gatherings in public spaces (Figure 2). Post the exhibition, seven experience-designers and seven artifact-users were interviewed (Gonsalves et al., 2022b). The project was featured in the Media Architecture Biennale 2020/21 conference (Gonsalves et al., 2021a).

2.2. TransHuman Saunter

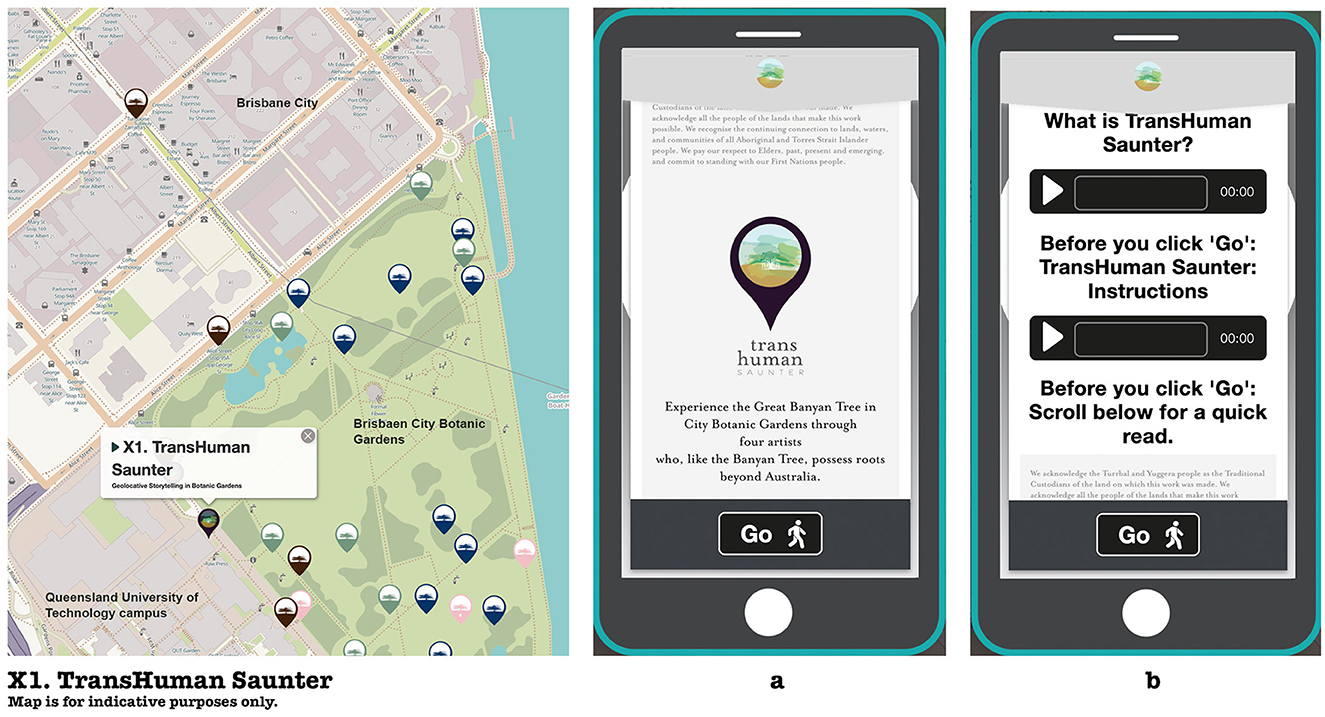

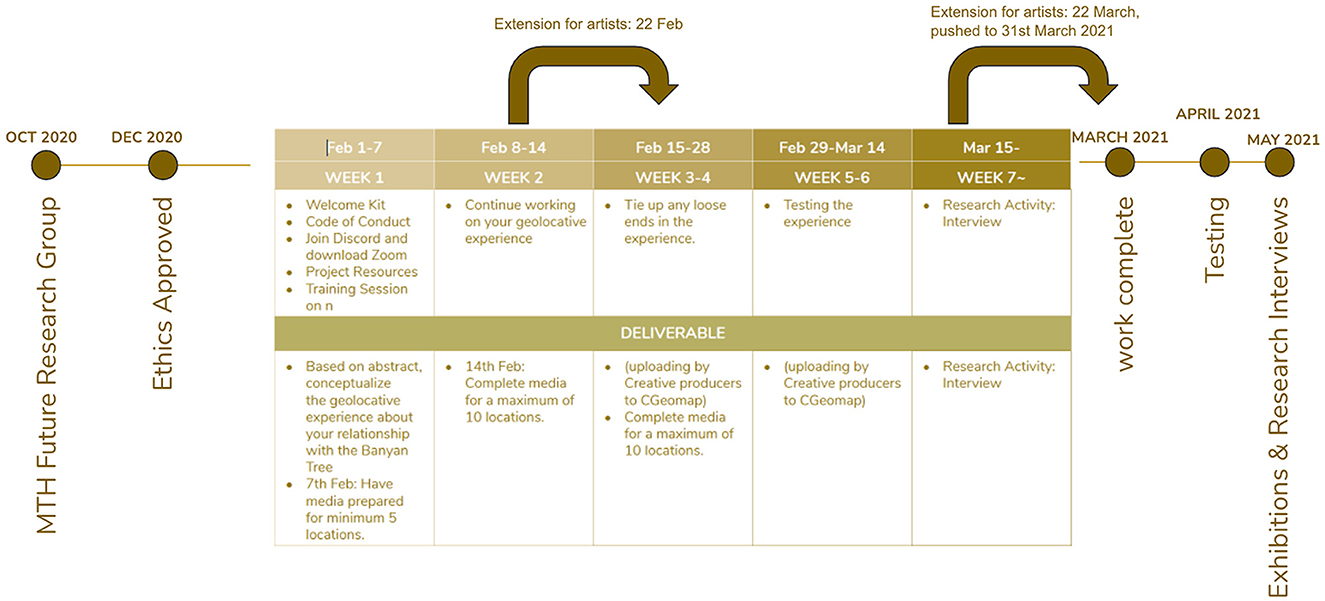

The TransHuman Saunter Project (THSP) is a situated digital storytelling project that can be experienced in the City Botanic Gardens, Brisbane, Australia and documents the socio-cultural, geographical, and environmental entanglements of four women of color with the Indian Banyan Tree (Ficus benghalensis) (Gonsalves et al., 2022b). THSP is a response to the Anthropocenic-generated earthly crises of the ongoing climate emergency through colonialism, human exceptionalism, and racial capitalism. The project uses the locative technology platform CGeomap to house four Botanic Garden-based narratives of place from the viewpoint of four experience-designers who are Brisbane-based migrants with various professional backgrounds: Agapetos of Samoa-Australia who is a filmmaker, Lan of Vietnam who is a digital communications strategist, Naputsamohn of Thailand who is an exhibition and spatial designer, and Natasha of India-Australia who is a visual artist. The project had four online workshops from February 2021, with the work completing in March 2021. While the work is best experienced with a smartphone in the gardens (Figure 5), it can also be experienced on a computer. The completed work was exhibited during the Brisbane Art Design festival 2021, Uroboros festival 2021, After Progress exhibition 2022, and in the repository of the More-than-Human Library. After an artist-mediated walk in the gardens, all four experience-designers and eight artifact-users were interviewed.

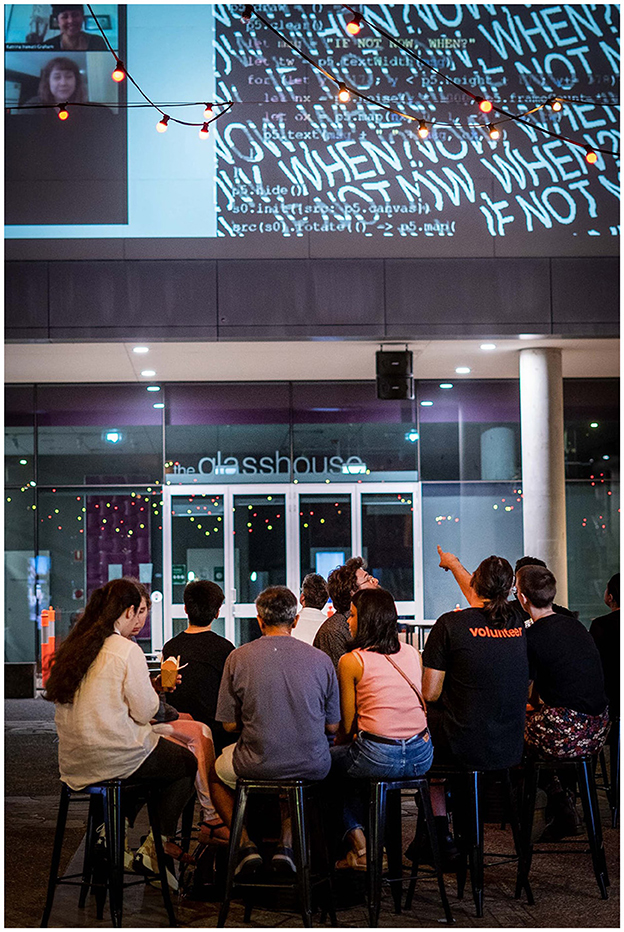

2.3. Chatty bench festival community media visual projections

CBF CMVP (Figures 6, 7) was the final event of the Chatty Bench Festival, a three-weekend festival that celebrated community storytelling in Kelvin Grove, Brisbane from November-December 2021. CBF CMVP, a collaboration between the lead author and Montreal-based creative coder Kofi Oduro, engaged in workshops where community stories were collected from 11 community members of various racial backgrounds, remixed with digital code by Oduro, and projected onto the university campus building with existing projectors (12,000 ANSI lumen) and a speaker system in Parer Place. The visual projections, a combination of the submitted digital media and the live-coded remixed digital media, took place on the evening of 4th December 2021. Post the event, six experience-designers and another six artifact-users were interviewed by the main author.

3. Reflecting on our radical placemaking practice

We break down Radical Placemaking in terms of the who, how, and what, which was initially elaborated in Figure 1 (Gonsalves et al., 2020). Based on the learnings across the three design interventions, the concept of Radical Placemaking has expanded to include aspects such as prototyping and staging live events, which are discussed in this section (Figure 8). We begin by elaborating on the who, which identifies stakeholders within radical placemaking: the radical accomplice who works with the radical community to develop the artifact and the ethics of engagement. The following section of how refers to the participatory design and action research process that the radical community engages in to create the artifact. The final section of what refers to digital placemaking strategies that are employed by the radical communities in the making of their artifacts, the event that showcases the artifacts to a broader community, and the documentation and publishing of the work to widen each project's reach and impact.

3.1. The how of radical placemaking

The key philosophy of the process underpinning Radical Placemaking is elucidated through an overarching philosophy of participatory action research and the making of the artifact through slow design and open digital pedagogy.

3.1.1. Participatory process

Radical Placemaking (Figure 8) borrows from Participatory Action Research (PAR), where participants engage in the research as “both subjects and co-researchers” so that the participants are actively involved in various stages of the research process: the planning and problem identification, planned action, evaluation, and reflection (Foth and Brynskov, 2016). The study notes two ways Radical Placemaking functioned and negotiated the ethos of Participatory Action Research. First, Radical Placemaking as a design practice emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic. Imagined as face-to-face workshops in computer labs, it pivoted to online and hybrid modalities (Gonsalves et al., 2021b); this led to exclusions of people who did not have personal technology or access to digital infrastructure that would have enabled them to participate. While this points to the larger digital inclusion debate about the availability, access, and affordability of digital tools (Thomas et al., 2020), the projects tackled the efficient use of technology where experience-designers learnt emerging technologies (Notley and Foth, 2008).

Second, each radical placemaking participatory process (Figure 9) began with the radical accomplice i.e., the main researcher and the community stakeholders determining a problem as opposed to having all participants involved from the start. Further, the main researcher imagined the process of each project, designing the prototype, testing the digital tools, and designing the workshops. The experience-designers' involvement began with the design of the artifact, facilitated by the main researcher where requested, and in the evaluation stage. Due to the intensive nature of creating and showcasing the digital artifacts, the experience-designers viewed the showcase and exhibition as the end of their role in the project. Although engaging in the evaluation process, the experience-designers did not engage in the reflection process with the researcher pointing to “not participating” as an option of participation (Bennett, 2004). Thus, the term “participation” in Radical Placemaking adopts a fluid and flexible nature in Radical Placemaking to account for dynamicity in participants' situations, desires, and inclination to participate and the limits of participation in the digital.

3.1.2. Slow design

Radical Placemaking merges the qualities of design and pedagogical philosophies of slow design principles with that of participatory action research. Slow design has six broad principles: (a) reveal: where slow design makes apparent spaces and experiences that are often missed or forgotten; (b) expand: the expression of the artifact is beyond its perceived functionality and life; (c) reflect: the artifacts induce reflection and reflective consumption; (d) engage: the processes are open-source and collaborative so that the designs can continue to evolve; (e) participate: people are active participants in the design process which can enhance communities; and (f) evolve: artifacts provide richer experiences as they mature (Strauss and Fuad-Luke, 2008; Grosse-Hering et al., 2013). On this basis, we felt that slow design is a fitting concept because it shares similar principles and goals. Radical placemaking seeks to transform public spaces and communities by challenging existing norms and power structures, promoting inclusivity, and encouraging active participation from community members. Slow design also emphasizes a holistic approach to design that prioritizes sustainability, mindfulness, and meaningful experiences, including deep engagement, commitment to a legacy, and reflective practice.

The designed digital artifacts of all three interventions were created with the intention to represent communities that are otherwise unheard and provoke thought about places and stories/histories that are often unseen in these places. The experience-designers built the artifacts through a participatory design process utilizing open-source, low-tech, and affordable technologies where possible over a period ranging from two weeks in CBF CBVP to the more than ten weeks' engagement of CBP and THSP (Figure 9). CBP and THSP had place-based digital stories mediated through the smartphone and CBF CMVP involved place-based media being creatively projected in public space. The intention of the artifacts was, through the immersive experiences in public space about social justice issues, to provoke learning and mindset change. The artifacts showed potential in creating awareness about the issue, providing embodied experiences in place, particularly CBP and THSP, and access to lived experiences that were otherwise not possible (Gonsalves et al., 2021b).

Further, the richness of the artifact lies in it being experienced in the urban environment, offering the artifact-user the opportunity to “role-play” the experience-designer's story while experiencing an alternative imagination of place. The artifacts remain accessible online and serve as a record of the experiences of the experience-designer during and about the COVID-19 pandemic. The process of the three design interventions and their outputs indicate that Radical Placemaking adapts Slow Design Principles in an effort to create mindful digital experiences of place.

3.1.3. Open (digital) design pedagogy

Open pedagogy entails both students and educators engaging in the creation of knowledge whilst emphasizing experiential learning (Tietjen and Asino, 2021). We opted for this approach to teaching and learning new skills as it aligns with the principles of inclusivity, collaboration, and community engagement that are central to Radical Placemaking, too. Open Design Pedagogy emphasizes the democratization of design processes, knowledge sharing, and the active involvement of diverse participants, which are common values shared by both concepts. We argue that by integrating open pedagogy into the praxis of radical placemaking, communities can engage in meaningful knowledge exchange and learning, challenge power structures, and create more inclusive and transformative public spaces.

The making of the digital artifacts utilized open-source digital tools such as Twine (interactive fiction tool), which required participants to learn coding to make their artifacts, and Hydra live coding web interface, where coding was optional for participants. THSP utilized a low-cost technological platform CGeomap for housing the narrative-based digital stories, as this project had a short timeline of four weeks and eliminated the need for learning coding which was identified as a challenge in CBP. Learning materials associated with these tools are also openly available. However, the COVID-19 pandemic pushed the pedagogy of radical placemaking to not just using digital tools for creating the place-based artifacts but also to going digital in delivery (Rosen and Smale, 2015). Digital tools for delivery of the projects included Google Classroom (digital learning environment), Zoom, Slack, and Discord for digital collaboration.

While the researchers and the experience-designers worked together to develop their artifacts through the online workshops, the experience-designers were the primary creators of their digital artifacts. The digital artifacts are pedagogical tools as they cover a variety of topics such as mental health, domestic violence, migration, colonization, and environmentalism which should be experienced in situ. Further, the experience-designers, particularly in the case of THSP, engaged in transfer of knowledge through performance lectures and online and offline exhibitions. Radical Placemaking had experience-designers expanding their hybrid literacies (Marenko, 2021) of design, technology, performance, and storytelling. The making of the digital artifacts offers transdisciplinary skills, criticality, world-building, and reflective thinking essential for new design futures (Ely, 2020) while indicating that anyone can be a “designer” given the opportunity.

3.2. The who of radical placemaking

We now turn to the participants in the praxis of radical placemaking. They comprise the radical community and the radical accomplice. This section also discusses the ethics of engagement.

3.2.1. Radical community

The Radical Community is the place-specific marginalized community that engages in Radical Placemaking. They can be split into the (a) experience-designers, who create the place-based digital artifact, and (b) the community stakeholders i.e. those who enable radical placemaking. In this study, marginalization is considered at the intersections of advantages and disadvantages a person may face due to factors such as age, sex, race, gender, and abilities (Crenshaw, 1991). The article highlights that the experience-designers themselves may not see themselves as marginalized and do recognize that they are beings of their own agency. The three design interventions predominantly showcased the work of those stuck in a transitory phase, such as international migrants who do not fit the mainstream identity of White Australia (Sargent and Larchanché-Kim, 2006) or as students in the COVID-19 pandemic without governmental support (Gibson and Moran, 2020). The term “marginalized” is used to acknowledge the discriminatory impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on ethnoracial identities (CBP, THSP, and CBF CMVP), the social justice issue of social isolation for liminal identities (CBP and CBF CMVP), and the experience of being a woman of color in White Australia (THSP).

While it is the marginal identity that is emphasized in Radical Placemaking, the community of the experience-designers transforms into a community of practice that is a community that faces a shared problem and learns to negotiate the problem through constant interactions (Wenger et al., 2002). In each project, experience-designers met regularly online to share stories, and sought each other's feedback and knowledge to create place-based narratives. They adopted technologies to digitize historical, personal, and social justice-driven accounts that are geolocated to place. In the creation of the digital artifacts, the experience-designers indicated their attachment to those places through place-based digital cultural narratives and media. In making these place-based digital narratives, they created pluralistic counter-narratives which represent alternative futures of place. Thus, while the Radical Placemaking design artifacts and interventions are led by marginalized communities, they transition beyond their identities to become a learning community that designs other imaginations of place.

3.2.2. Radical accomplice

The Radical Placemaking design interventions have a facilitator, termed a radical accomplice, who supports in the delivery of the participatory design of artifacts and the research methodology of participatory action research (PAR). The term “accomplice” is distinctive from the activist terminology of “ally” as, compared to the ally, they are involved in deeper work with the community (Dombrowski, 2017). In Radical Placemaking, the radical accomplice, similar to the transdisciplinary creative producer (Pinxit-Gregg, 2021), is responsible for the educational, social, cultural, and technological dimensions of the design interventions and its creative production.

The main researcher functioned as the radical accomplice in this study. For the projects CBP and THSP, the main researcher, an architect and transdisciplinary designer, began each project by developing prototypes of sample digital artifacts as a learning tool for the radical community. Following that, the main researcher was involved in the following ways: building relationships with the community stakeholders, acquiring funding grants, managing budgets and timeline, converting the projects to online during COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, designing of marketing assets, website development and maintenance, setting up learning tools and content (such as Google Classroom), liaising with external and tech partners, ensuring experience-designers' compensation, checking and ensuring the limits of the experience-designers (such as mental health), providing technical support to the experience-designers (such as support sessions during CBP), conducting research activities, and writing the research publications. The challenges that the main researcher navigated in the project were conflicts associated with managing their own expectations of the quality of the digital artifacts and the experience-designers and low self-confidence and inexperience of the experience-designers when it came to exhibiting or discussing their work with the audience. Further, the researcher would experience isolation as the one carrying the vision of the projects, which draws attention for the need of these projects to be managed team-based. Thus, the role of the radical accomplice is multidimensional and complex, and the researcher's experience emphasizes the need for a team to deliver these projects.

3.2.3. Ethics of engagement

Radical Placemaking is an extension of digital placemaking that imbibes the ethos of participatory action research. Participatory action research is used to challenge injustice in place and document the phenomena of everyday life through creative use of digital technologies (Gonsalves et al., 2020). This section covers radical placemaking with regards to ethics: subjectivity, confidentiality, compensation, and the location of power within the process.

First, the radical placemaking projects required the researcher to engage in strong subjectivity as both a researcher, designer, facilitator, and a community member while maintaining relationships between the researcher and the experience-designers to create the digital artifact (Foth et al., 2007). Second, while all participants were given the choice to remain confidential, Radical Placemaking mediated the erasure of the experience-designers through de-identification and confidentiality as specified through the ethics review processes (Blake, 2007). Given the nature of the projects, experience-designers were credited for their contributions to the projects on websites, social media, publications, exhibitions, and where applicable with their consent. Thirdly, the experience-designers also received monetary compensation for their time as research participants in the projects and own the intellectual property rights to their artifacts. Finally, the desire of the participatory action research process is that the power dynamics in the research process is equally shared between the researcher and participant (Grant et al., 2008). However, real-world implementation of projects posed dilemmas: the researcher needing to negotiate the projects to suit the short PhD timelines and external partnerships, negotiation of deliverables such as showcasing through exhibitions and planning practice sessions for performance lectures, and the researcher being the node of all relationships- their maintenance as well as their breakdown. Thus, Radical Placemaking involves complex and constant negotiation of power between researcher and participants, and researcher and stakeholders.

3.3. The what of radical placemaking

The Radical Placemaking process outputs three kinds of knowledge assets, which are expanded on below. Two are in the digital form, that is the prototype and the digital artifact that are created by the experience-designers. Once the digital artifacts are created, the third output involves dissemination in the form of a showcase event, moving beyond academic publications.

3.3.1. The prototype

In the creative and design process of objects, buildings, and interactive experiences, the prototype is a tool to indicate viability, testing unknowns, decision-making, reflecting a future outcome, and creating new knowledge (Odom et al., 2016). The importance of prototypes are seen in commercial innovation processes such as the Google Design Sprint which are implemented in order to save development and testing time for new services and to bypass the business bureaucracy that can stymie innovation (Banfield et al., 2015).

In Radical Placemaking interventions, the prototypes served multiple purposes such as learning and testing technology, exploring the potential of the technology, and serving as an example for the experience-designers as they begin work on their digital artifact. In CBP, the main researcher created the pre-CBP pilot and prototype “In the mood for Love” to learn and test Twine in order to check its potential for geolocative storytelling. The learning process that the main researcher underwent to develop the prototype played a role in developing the curriculum and resources of CBP. Further, the prototype with the raw file (Twine code) served for the experience-designers as a repository of code to mimic and experiment with. In THSP, the prototype resulted from collaborative work that the main researcher engaged in during the Locative Media (online) Summer School 2020 (Supercluster, 2020) titled “Locative Media for Earthlings in a Changing World” (Abdou et al., 2020). The engagement in this summer school and creation of the prototype was critical in developing the THSP work plan and goals (Figure 9). Finally, for CBF CMVP, examples of what was going to be created through the digital media and live coding set the expectations of the project. Thus, in Radical Placemaking, it was the making and sharing of the prototype that determined what was possible in each project and served as an important tool in the experiential learning, creating, and deploying of the experience-designer's digital artifact.

3.3.2. The digital artifact

Pivoting away from the Western and elitist notions of design (Papanek, 1985), Radical Placemaking is where marginalized communities design and engage in place-based activism through the use of technology. It involves design processes and methods to critically engage both the marginalized maker and the user in making and experiencing counter-narratives aimed at positive social change (Hernandez Ibinarriaga and Martin, 2021).

CBP, through the making of the artifacts, highlighted the need for a stronger feedback and iteration loop in the design process, which was implemented in THSP. Additionally, CBP involved the experience-designers learning creative coding which was eliminated in THSP through the use CGeomap: CBP and THSP had the same time frames but with the elimination of creative coding in THSP, so the THSP experience-designers could focus on the creative making of their works. Further, in CBP and CBF CMVP, the majority of the experience-designers were of non-designer backgrounds whereas THSP involved people with creative backgrounds. Thus, reducing complexity in making, a feedback loop, and experience-designers' creative backgrounds resulted in THSP's sophisticated design outcome. CBF CMVP functioned differently to CBP and THSP: the project had a tighter timeline, a limited feedback loop with a vigorous process, and it had a similar demographic mix to CBP. However, CBF CMVP indicates that meaningful design outcomes are a result of process intention and facilitation objectives. For example, the facilitators leading the packaging of the digital media for projection were conscious to minimally edit the digital media as digital media glitches, fumbles, and retakes, which are normally edited out, had meaning in this work. All three projects resulted in designed activist digital artifacts on personal social justice issues as was the goal of Radical Placemaking. It further reinforces that design is a fundamental human activity which can be enhanced with the right conditions and resources (Papanek, 1985).

3.3.3. The showcase (event + publications)

Radical Placemaking manifests itself in public spaces as opposed to the traditional spaces of museums and civic institutions (Schuermans et al., 2012). Thus, a key step of Radical Placemaking is its showcase in public space. CBP's Week 6 online exhibition in Mozilla Hub's virtual environment revealed the experience-designers' desire to meet in person, which led to the face-to-face exhibition in KGUV Kundu Park (Gonsalves et al., 2021b). While CBP's goal was to construct the social capital of KGUV community members through artifact-making, it also highlighted the need for an event which can further contribute to community identity and community building (Loopmans et al., 2012).

Post CBP, each Radical Placemaking design intervention had a showcase on the completion of the making of the artifact and was tailor-made to the best way the artifact could be experienced. For example, while THSP went on to exhibit at international conferences and online exhibitions, the key event for the project was when the artists themselves took the artifact-users on an experiential walk through Brisbane City Botanic Gardens using a smartphone to access the situated digital stories. Through this, the artifact-users felt a strong attachment to THSP's experience-designers while experiencing an immersion of the digital stories. Thus, the purpose of the showcase is to mark the definite end to the making of the digital artifact for the experience-designers, provide a get-together to reconnect and celebrate the completion of the intervention, and offer a place for the artifact-users to engage with the digital artifact. The making of the event itself is a placemaking act and act of knowledge-making as it brings people together in shared memory-making and sense-making around the radical placemaking project.

4. Conclusion

This paper initially established the context of Radical Placemaking praxis and its associated challenges. It then illustrated the practice and framework of Radical Placemaking through the design actions of CBP, THSPP, and CBF CMVP that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. Key components of Radical Placemaking included the participatory action research process, the adoption of slow design principles during artifact creation, and the employment of open pedagogical principles to generate knowledge through artifact development. The community, the radical accomplice facilitating the process, and the ethics of engagement play pivotal roles in the participatory processes of Radical Placemaking.

The final phase of this praxis focuses on specific outputs of the Radical Placemaking process. This includes the essential prototype that shapes the engagement process itself, the resulting digital artifact created by the radical community, the knowledge production occurring through the digital artifact, the event designed to engage the broader community with the artifact, and the reporting on the event through a digital website or research publications. It is important to note that these elements of Radical Placemaking are replicable but subject to contextual factors, the specific place, and the engaged community. As interventions continue, creative communities grow, more researchers become facilitators, and marginalized communities gain control over their right to the city through technology, using these tools to influence the production of knowledge.

The process of Radical Placemaking can be applied to various projects, extending beyond the realm of traditional placemaking. However, there are strengths and limitations to consider when using Radical Placemaking as a conceptual tool, along with factors to be mindful of for further engagement with the concept. In the context of city placemaking, challenges arise due to limited access to technological expertise and issues of digital exclusion, which restrict who can participate in shaping the city and whose perspectives can be represented. While participatory practices have been explored in traditional placemaking, the literature lacks sufficient exploration of these practices in digital placemaking. This research aims to address this gap by exploring the interconnections between place, people, and technology through Radical Placemaking.

Radical Placemaking, as a form of digital placemaking, focuses on marginalized communities utilizing digital technologies to create experiential digital interventions addressing social justice issues. However, it is essential to acknowledge that access to technology and proficiency in its use can hinder participation. Nevertheless, if the playing field is leveled, Radical Placemaking offers an opportunity to cultivate creative communities engaging with technology. Technology serves as a tool within this process, while the ultimate goal of Radical Placemaking is to empower these communities to create digital artifacts that facilitate critical inquiry, reflection, and social justice action.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the QUT Human Research Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KG, GC, and MF contributed to conception and design of the study. KG coordinated the projects, undertook research activities, performed analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Turrbal and Yuggara Country as the traditional custodians of the lands that this work has emerged from and recognize their and our continuing connection to spirit, land, and waters. We pay our respect to Elders past, present, and emerging, and to all the decisions that have brought us to this moment. The authors thank all the study participants, project partners, and team members of CBP, THSP, and CBF CMVP. The CBP and CBF CMVP was supported by the KGUV Principal Body Corporate and Brisbane City Council. THSP was supported by QUT More-than-Human Futures Research Group.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^We use the spelling “blak” here on purpose in support of the call by artist Destiny Deacon who “redefined both the spelling and the meaning of the word ‘black' as a direct response to non-Indigenous people's labeling and consistent misrepresentations of our people” (Munro, 2020).

References

Abdou, E., Apolonio, L., Benson, T., Cámara, C., Drake, B., Elliott, K. J., et al. (2020). Locative Media for Earthlings in a Changing World. CGeomap. Available online at: https://cgeomap.eu/earthlings/ (accessed July 21, 2023).

Akama, Y., Hagen, P., and Whaanga-Schollum, D. (2019). Problematizing replicable design to practice respectful, reciprocal, and relational co-designing with indigenous people. Des. Cult. 11, 59–84. doi: 10.1080/17547075.2019.1571306

Atkinson, R. (2000). The hidden costs of gentrification: displacement in central London. J. Housing Built Environ. 15, 307–326. doi: 10.1023/A:1010128901782

Banfield, R., Todd Lombardo, C., and Wax, T. (2015). Design Sprint: A Practical Guidebook for Building Great Digital Products. Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly Media.

Barry, J., and Agyeman, J. (2020). On belonging and becoming in the settler-colonial city: co-produced futurities, placemaking, and urban planning in the United States. J. Race Ethn. City 1, 22–41. doi: 10.1080/26884674.2020.1793703

Bennett, M. (2004). A review of the literature on the benefits and drawbacks of participatory action research. First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 1, 19–32.

Blake, M. K. (2007). Formality and friendship: research ethics review and participatory action research. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geograph. 6, 411–421.

Boyd, A., and Mitchell, D. O. (2013). Beautiful Trouble: A Toolbox For Revolution. New York City, NY: OR Books. Available online at: https://beautifultrouble.org/ (accessed July 21, 2023).

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exe. Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Crit. Inquiry 18, 1–21. doi: 10.1086/448619

Burns, R., and Berbary, L. A. (2021). Placemaking as unmaking: settler colonialism, gentrification, and the myth of “revitalized” urban spaces. Leis. Sci. 43, 644–660. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2020.1870592

Caldwell, G. A., and Foth, M. (2014). “DIY media architecture: open and participatory approaches to community engagement,” in Proceedings of the 2Nd Media Architecture Biennale Conference: World Cities, 1–10. doi: 10.1145./2682884.2682893

Colley, A., Thebault-Spieker, J., Lin, A. Y., Degraen, D., Fischman, B., Häkkilä, J., et al. (2017). “The Geography of PokéMon GO: beneficial and problematic effects on places and movement,” in Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (New York City, NY: ACM), 1179–1192. doi: 10.1145./3025453.3025495

Courage, C. (2020). “Preface: the radical potential of placemaking,” in The Routledge Handbook of Placemaking (Routledge), 219–223. doi: 10.4324./9780429270482-27

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 43, 1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039

Devlin, H. (2020). Why Are People From BAME Groups Dying Disproportionately of COVID-19? The Guardian. Available online at: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/22/why-are-people-from-bame-groups-dying-disproportionately-of-covid-19 (accessed July 21, 2023).

Dombrowski, L. (2017). Socially just design and engendering social change. Interactions 24, 63–65. doi: 10.1145/3085560

Duarte, A. M. B., Brendel, N., Degbelo, A., and Kray, C. (2018). Participatory design and participatory research: an hci case study with young forced migrants. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 25, 1–39. doi: 10.1145/3145472

Ely, P. (2020). Designing futures for an age of differentialism. Des. Culture 12, 265–288. doi: 10.1080/17547075.2020.1810907

Estrada-Grajales, C., Foth, M., and Mitchell, P. (2018). Urban imaginaries of co-creating the city: local activism meets citizen peer-production. J. Peer Prod. 11, 32–35.

Foth, M. (2017). “Lessons from urban guerrilla placemaking for smart city commons,” in Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Communities and Technologies, eds M. Rohde, I. Mulder, D. Schuler, and M. Lewkowicz (Association for Computing Machinery), 32–35. doi: 10.1145/3083671.3083707

Foth, M., and Brynskov, M. (2016). “Participatory action research for civic engagement,” in Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice, eds E. Gordon and P. Mihailidis (MIT Press), 563–580. doi: 10.7551./mitpress/9970.003.0046

Foth, M., Brynskov, M., and Ojala, T. (Eds.). (2016). Citizen's Right to the Digital City: Urban Interfaces, Activism, and Placemaking. Singapore: Springer. doi: 10.1007./978-981-287-919-6

Foth, M., Odendaal, N., and Hearn, G. (2007). “The view from everywhere: towards an epistemology for urbanites,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Intellectual Capital, Knowledge Management and Organisational Learning (ICICKM) (Reading: Academic Conferences International), 127–134. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/9149/ (accessed July 21, 2023).

Foth, M., Schroeter, R., and Anastasiu, I. (2011). “Fixing the city one photo at a time: mobile logging of maintenance requests,” in Proceedings of the 23rd Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference on (OzCHI'11), 126–129. doi: 10.1145./2071536.2071555

Foth, M., Tomitsch, M., Satchell, C., and Haeusler, M. H. (2015). “From users to citizens: some thoughts on designing for polity and civics,” in Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Australian Special Interest Group for Computer Human Interaction, 623–633. doi: 10.1145/2838739.2838769

Fredericks, J., Caldwell, G. A., and Tomitsch, M. (2016). “Middle-out design: collaborative community engagement in urban HCI,” in Proceedings of the 28th Australian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction, 200–204. doi: 10.1145./3010915.3010997

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition. New York City, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.

Gibson, J., and Moran, A. (2020). As coronavirus spreads, “it's time to go home” Scott Morrison tells visitors and international students. ABC News. Available online at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-03/coronavirus-pm-tells-international-students-time-to-go-to-home/12119568 (accessed July 21, 2023).

Gonsalves, K. (2021). Chatty Bench Festival 2021. Chatty Bench Project. Available online at: https://sites.google.com/urbaninformatics.net/chatty-bench-project/chatty-bench-festival-2021 (accessed July 21, 2023).

Gonsalves, K., Foth, M., and Caldwell, G. (2021a). Chatty Bench Project: Radical Media Architecture in Precarious Times: Situated [Story-Place-Media] Making during COVID-19. MIT Press. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/210834/ (accessed July 21, 2023).

Gonsalves, K., Foth, M., and Caldwell, G. (2021b). Radical placemaking: utilizing low-tech AR/VR to engage in communal placemaking during a pandemic. Interact. Design Architect., 48, 143–164. doi: 10.55612/s-5002-048-007

Gonsalves, K., Foth, M., and Caldwell, G. (2021c). “Chatty bench project: Radical media architecture during COVID-19 pandemic,” in Proceedings of the Media Architecture Biennale 20 (MAB20) (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery), 182–183. doi: 10.1145/3469410.3469428

Gonsalves, K., Foth, M., and Caldwell, G. (2022a). “Radical placemaking: digitally situated community narratives as inclusive citymaking practice,” in The Routledge Handbook of Architecture, Urban Space and Politics, Vol II: Ecology, Social Participation and Marginalities, eds in N. Bobic and F. Haghighi (Routledge). doi: 10.4324./9781003112471

Gonsalves, K., Foth, M., Caldwell, G., and Jenek, W. (2020). Radical Placemaking: Immersive, Experiential and Activist Approaches for Marginalised Communities. Connections: Exploring Heritage, Architecture, Cities, Art, Media. Canterbury, United Kingdom: Connections: Exploring Heritage, Architecture, Cities, Art, Media.

Gonsalves, K., Aia-Fa'aleava, A., Ha, L. T., Junpiban, N., Narain, N., Foth, M., and Caldwell, G. A. (2022b). TransHuman saunter: multispecies storytelling in precarious times. Leonardo 1–12. doi: 10.1162./leon_a_02243

Graham, M. (2014). Aboriginal notions of relationality and positionalism: a reply to Weber. Global Discourse, 4, 17–22. doi: 10.1080/23269995.2014.895931

Grant, J., Nelson, G., and Mitchell, T. (2008). “Negotiating the challenges of participatory action research: relationships, power, participation, change and credibility,” in The SAGE Handbook of Action Research, eds P. Reason and H. Bradbury (Oaks, CA: Sage Thousand), pp. 589–607.

Grosse-Hering, B., Mason, J., Aliakseyeu, D., Bakker, C., and Desmet, P. (2013). “Slow design for meaningful interactions,” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 3431–3440. doi: 10.1145./2470654.2466472

Harvey, D. (2012). Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. New York, NY: Verso Books.

Henriques-Gomes, L., and Visontay, E. (2020). Australian Black Lives Matter protests: tens of thousands demand end to Indigenous deaths in custody. The Guardian. Available online at: http://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/jun/06/australian-black-lives-matter-protests-tens-of-thousands-demand-end-to-indigenous-deaths-in-custody (accessed July 21, 2023).

Hernandez Ibinarriaga, D., and Martin, B. (2021). Critical co-design and agency of the real. Des. Cult. 13, 253–276. doi: 10.1080/17547075.2021.1966731

Hjorth, L., and Richardson, I. (2017). Pokémon GO: mobile media play, place-making, and the digital wayfarer. Mobile Med. Commun. 5, 3–14. doi: 10.1177/2050157916680015

Houghton, K., Foth, M., and Miller, E. (2015). Urban acupuncture: hybrid social and technological practices for hyperlocal placemaking. J. Urban Technol. 22, 3–19. doi: 10.1080/10630732.2015.1040290

Iveson, K. (2013). Cities within the city: do-it-yourself urbanism and the right to the city. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 37, 941–956. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12053

Lashua, B. D. (2013). Pop-up cinema and place-shaping: urban cultural heritage at Marshall's Mill. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leisure Events 5, 123–138. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2013.789728

Layland, E. K., Stone, G. A., Mueller, J. T., and Hodge, C. J. (2018). Injustice in mobile leisure: a conceptual exploration of Pokémon Go. Leisure Sci. 40, 288–306. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2018.1426064

LeBlanc, A. G., and Chaput, J.-P. (2017). Pokémon go: a game changer for the physical inactivity crisis? Prevent. Med. 101, 235–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.11012

Ledwith, M. (2007). Reclaiming the radical agenda: a critical approach to community development. Infed. https://infed.org/mobi/reclaiming-the-radical-agenda-a-critical-approach-to-community-development/ (accessed July 21, 2023).

Lehner, U., Baldauf, M., Eranti, V., Reitberger, W., and Fröhlich, P. (2014). “Civic engagement meets pervasive gaming: toward long-term mobile participation,” Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 32nd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1483–1488. doi: 10.1145./2559206.2581270

Lepofsky, J., and Fraser, J. C. (2003). Building community citizens: claiming the right to place-making in the city. Urban Stud. 40, 127–142. doi: 10.1080/00420980220080201

Loopmans, M., Cowell, G., and Oosterlynck, S. (2012). Photography, public pedagogy and the politics of place-making in post-industrial areas. Soc. Cult. Geography 13, 699–718. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2012.723734

Low, A., Turner, J., and Foth, M. (2022). “Pla(y)cemaking with care: locative mobile games as agents of place cultivation,” in Proceedings of the 25th International Academic Mindtrek Conference, 135–146. doi: 10.1145./3569219.3569311

Lydon, M., and Garcia, A. (2015). “A tactical urbanism how-to,” in Tactical Urbanism: Short-term Action for Long-term Change (pp. 171–208). Island Press. doi: 10.5822./978-1-61091-567-0_5

Marenko, B. (2021). Stacking complexities: reframing uncertainty through hybrid literacies. Des. Culture 13, 165–184. doi: 10.1080/17547075.2021.1916856

Mejeur, C. (2019). “PokéStories: on narrative and the construction of augmented reality,” in The Pokemon Go Phenomenon: Essays on Public Play in Contested Spaces, eds J. Henthorn, A. Kulak, and K. Purzycki (McFarland) (pp. 136–155). Available online at: https://mcfarlandbooks.com/product/the-pokemon-go-phenomenon/ (accessed July 21, 2023).

Milner, H. R., and Howard, T. C. (2013). Counter-narrative as method: race, policy and research for teacher education. Race Ethn. Edu. 16, 536–561. doi: 10.1080/1362013817772

Monno, V., and Khakee, A. (2012). Tokenism or political activism? Some reflections on participatory planning. Int. Plann. Stud. 17, 85–101. doi: 10.1080/13563475.2011.638181

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2020). “I still call Australia home: indigenous belonging and place in a white postcolonizing society,” in Uprootings/Regroundings: Questions of Home and Migration, eds S. Ahmed, C. Castada, A.-M. Fortier, and M. Sheller Routledge, pp. 23–40.

Morrison, T. (1998). Toni Morrison (interview by E. Farnsworth) [Interview]. PBS NewsHour. Available online at: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/toni-morrison (accessed July 21, 2023).

Munro, K. (2020). Why “Blak” not Black?: Artist Destiny Deacon and the origins of this word. SBS NITV. Available online at: https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/why-blak-not-black-artist-destiny-deacon-and-the-origins-of-this-word/7gv3mykzv (accessed July 21, 2023).

Notley, T., and Foth, M. (2008). Extending Australia's digital divide policy: an examination of the value of social inclusion and social capital policy frameworks. Aus. Soc. Policy 7, 87–110.

Odom, W., Wakkary, R., Lim, Y-. K., Desjardins, A., Hengeveld, B., Banks, R., et al. (2016). “From research prototype to research product,” in Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2549–2561. doi: 10.1145./2858036.2858447

Paavilainen, J., Korhonen, H., Alha, K., Stenros, J., Koskinen, E., Mayra, F., et al. (2017). “The PokéMon GO experience: a location-based augmented reality mobile game goes mainstream,” in Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2493–2498. doi: 10.1145./3025453.3025871

Papanek, V. (1985). Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. Chicago: Academy Chicago.

Pinxit-Gregg, Q. (2021). The Transdisciplinary Creative Producer: The Role and Practice of a Creative Producer in Festivals; Emerging and Ever-Evolving. MPhil, Queensland University of Technology.

Powell, J., and Kelly, A. (2017). Accomplices in the academy in the age of Black Lives Matter. J. Crit. Thought Praxis 6, 3. doi: 10.31274/jctp-180810-73

Project for Public Spaces (2007). What is Placemaking? Available online at: https://www.pps.org/article/what-is-placemaking (accessed July 21, 2023).

Rappaport, J., and Simkins, R. (1991). Healing and empowering through community narrative. Prevent. Human Serv. 10. 29–50. doi: 10.1300/J293v10n01_03

Rosen, J. R., and Smale, M. A. (2015). Open Digital Pedagogy= Critical Pedagogy. Available online at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1682andcontext=ny_pubs (accessed July 21, 2023).

Sanders, E. B. N. (2006). “Scaffolds for building everyday creativity,” in, Designing Effective Communications: Creating Contexts for Clarity and Meaning, ed J. Frascara (Allworth Press), pp. 65–77.

Sargent, C. F., and Larchanché-Kim, S. (2006). Liminal lives: immigration status, gender, and the construction of identities among Malian migrants in Paris. Am. Behav. Scient. 50, 9–26. doi: 10.1177/0002764206289652

Schuermans, N., Loopmans, M. P. J., and Vandenabeele, J. (2012). Public space, public art and public pedagogy. Soc. Cult. Geography 13, 675–682. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2012.728007

Slessor, C., and Boisvert, E. (2020). Black Lives Matter protests renew push to remove “racist” monuments to colonial figures. ABC News. Available online at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-10/black-lives-matter-protests-renew-push-to-remove-statues/12337058 (accessed July 21, 2023).

Slingerland, G., Gonsalves, K. A., and Murray, M. T. (2022). “Design probes in a pandemic: two tales of hybrid radical placemaking from Ireland and Australia,” in Proceedings of the 34th Australian Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 126–142. doi: 10.1145./3572921.3572931

Spivak, G. C. (2010). “Can the subaltern speak?” in Can the Subaltern Speak? Reflections on the History of an Idea, ed R. C. Morris (Columbia University Press), pp. 21–78.

Strauss, C. F., and Fuad-Luke, A. (2008). “The slow design principles: a new interrogative and reflexive tool for design research and practice,” in Changing The Change: Design Visions, Proposals and Tools, eds C. Cipolla and P. P. Peruccio (Politecnico di Milano and Politecnico di Torino). Available online at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/52dfe66be4b0cad36168429a/t/53499733e4b09ac51176571d/1397331763401/CtC_SlowDesignPrinciples.pdf (accessed July 21, 2023).

Supercluster (2020). Locative Media for Earthlings in a Changing World. Supercluster. Available online at: https://supercluster.eu/courses/earthlings/ (accessed July 21, 2023).

Sutton, S. E., and Kemp, S. P. (Eds.). (2011). The Paradox of Urban Space: Inequality and Transformation in Marginalized Communities. Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057./9780230117204

Thomas, J., Barraket, J., Wilson, C. K., Holcombe-James, I., Kennedy, J., Rennie, E., et al. (2020). The Australian Digital Inclusion Index 2020. Australian Digital Inclusion Index.

Tietjen, P., and Asino, T. I. (2021). What is open pedagogy? Identifying commonalities. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distribut. Learn. 22, 185–204. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v22i2.5161

Tuan, Y. F. (1991). Language and the making of place: a narrative-descriptive approach. Annals Assoc. Am. Geographers 81, 684–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1991.tb01715.x

Vella, K., Johnson, D., Cheng, V. W. S., Davenport, T., Mitchell, J., Klarkowski, M., et al. (2019). A sense of belonging: Pokémon GO and social connectedness. Games Culture 14, 583–603. doi: 10.1177/1555412017719973

Vlachokyriakos, V., Crivellaro, C., Le Dantec, C. A., Gordon, E., Wright, P., Olivier, P., et al. (2016). “Digital civics: citizen empowerment with and through technology,” Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1096–1099. doi: 10.1145./2851581.2886436

Wang, C. Y., and Kuo, C. L. (2018). The formulation of hybrid reality: Pokémon Go mania. Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Virtual, Augmented, and Intelligent Environments, 160–170. doi: 10.1007./978-3-319-92052-8_13

Keywords: placemaking, participatory action research, urban informatics, research methodology, research ethics, participatory design, radical placemaking

Citation: Gonsalves K, Caldwell GA and Foth M (2023) The praxis of radical placemaking. Front. Comput. Sci. 5:1193538. doi: 10.3389/fcomp.2023.1193538

Received: 25 March 2023; Accepted: 03 July 2023;

Published: 02 August 2023.

Edited by:

Laura Maye, University College Cork, IrelandReviewed by:

Sarah Foley, University College Cork, IrelandJanis Lena Meissner, Vienna University of Technology, Austria

Copyright © 2023 Gonsalves, Caldwell and Foth. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marcus Foth, bS5mb3RoQHF1dC5lZHUuYXU=

Kavita Gonsalves

Kavita Gonsalves Glenda Amayo Caldwell2

Glenda Amayo Caldwell2 Marcus Foth

Marcus Foth