- 1Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang, China

- 2Department of General Surgery, Tianjin Haihe Hospital, Tianjin, China

Helicobacter pylori is the main pathogenic bacterium involved in chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer and a class 1 carcinogen in gastric cancer. Current research focuses on the pathogenicity of H. pylori and the mechanism by which it colonizes the gastric mucosa. An increasing number of in vivo and in vitro studies demonstrate that H. pylori can invade and proliferate in epithelial cells, suggesting that this process might play an important role in disease induction, immune escape and chronic infection. Therefore, to explore the process and mechanism of adhesion and invasion of gastric mucosa epithelial cells by H. pylori is particularly important. This review examines the relevant studies and describes evidence regarding the adhesion to and invasion of gastric mucosa epithelial cells by H. pylori.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative, flagellated, microaerophilic bacterium that selectively colonizes the gastric mucosa. H. pylori is one of the most common infectious agents worldwide, and approximately 50% of the world's population is estimated to be infected (Marshall and Warren, 1983, 1984). Although the detailed transmission route of H. pylori remains uncertain, an oral-oral or fecal-oral route during childhood is thought to be the most plausible method of human-to-human transmission (Goh et al., 2011). Once established, H. pylori has no significant bacterial competitors (Peek and Blaser, 2002). The prevalence of H. pylori infection varies widely by geographic area, age, race, and socioeconomic status (SES), and developing appear to have higher infection rates than developed countries (Brown, 2000). Indeed, the prevalence exhibits country-to-country variation, with values as low as 15.4% in Australia to values as high as 90% in developing countries such as Iran (Moujaber et al., 2008; Hosseini et al., 2012; Siao and Somsouk, 2014). H. pylori is unique in that the bacterium can persist for decades in the harsh stomach environment, where it damages the gastric mucosa and alters the pattern of gastric hormone release, thereby affecting gastric physiology (Wang et al., 2014). The slow development of cancer known as Correa's cascade (Correa, 1992) includes a series of intermediate stages (precancerous lesions) before malignancy per se occurs. These precancerous lesions occur in the following order: gastritis, atrophy, intestinal metaplasia (IM), and eventually dysplasia. H. pylori represents the most significant risk factor for gastric malignant tumors (Wang et al., 2014). Gastric cancer (GC) is an insidious disease, with symptoms that often manifest at an advanced stage, a time when the few remaining therapeutic options have low efficiency (Boreiri et al., 2013). Approximately 10% of infected individuals develop severe gastric lesions, such as those in peptic ulcer disease; 1–3% progress to GC, with a low 5-year survival rate (Cirak et al., 2007), and 0–1% develop mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (Noto and Peek, 2012; Parreira et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). Compared with uninfected individuals, individuals infected with H. pylori are estimated to have a 2–8-fold increased risk of developing GC (Huang et al., 1998; Eslick et al., 1999; Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group, 2001; Kamangar et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007), and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified H. pylori as a class I carcinogen (IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, 1994). However, the inability of the immune system to clear H. pylori infection is not well described. Furthermore, the mechanisms controlling the induction and maintenance of H. pylori-induced chronic inflammation are only partly understood.

In the past, H. pylori was considered to be a non-invasive bacterium that generally only adhered to gastric mucosa epithelial cells or survived in the gastric lumen. In contrast, recent studies have shown that H. pylori is invasive, and it is now regarded as a special intracellular pathogen (Petersen and Krogfelt, 2003; Dubois and Borén, 2007). H. pylori microcolonies form on the surface of the cell membrane, and this area then becomes the microenvironment for bacterial reproduction (Tan et al., 2009). H. pylori can invade cells and replicate to reproduce and complete an entire biological cycle by cell division (Chu et al., 2010). Nonetheless, the mechanism of invasion remains unclear, and studies to date have mainly concentrated on receptor-mediated endocytosis and a tyrosine kinase-dependent process (Evans et al., 1992; Birkness et al., 1996; Su et al., 1999; Kwok et al., 2002). A phagosome forms after H. pylori invades gastric epithelial cells; the bacterium then exits cells to colonize again while conditions are suitable and repeatedly infects cells. These findings suggest that invasion might play an important role in disease induction, immune escape, and chronic infection (Kwok et al., 2002; Dubois and Borén, 2007; Jang et al., 2013). In this “cellular internalization” process, a bacterium specifically binds to a host cell receptor and enters the cytoplasm via phagocytic vacuoles formed through cell membrane invagination. Therefore, to provide insight into the pathogenic mechanism of H. pylori, this article will review relevant studies and describe evidence for the adhesion and invasion of gastric mucosa epithelial cells by this bacterium.

Host Cell Adhesion by H. pylori

Within the gastric mucus layer, bacteria can be found relatively close to the gastric lumen or deep within the gastric glands, and these microbes can either swim freely (Hazell et al., 1986; Schreiber et al., 2004; Celli et al., 2009) or attach to gastric epithelial cells (Hessey et al., 1990). To achieve successful engraftment, the most important step in H. pylori infection, the bacterial cells must survive under various unfavorable conditions, such as exposure to pepsin and an extremely low pH. Engraftment occurs primarily when adhesion molecules or other molecules on the surface of H. pylori bind to mucins, allowing the bacterial cells to colonize the gastric mucosa epithelium. This event triggers expression of several bacterial genes, including some that encode virulence factors and protect the pathogen from clearance mechanisms, such as liquid flow, peristaltic movement or shedding of the mucous layer (Kim et al., 2004). This process includes at least two steps: (1) H. pylori quickly moves through the mucus layer to the surface of the gastric mucosa, which has a relatively neutral pH, under the aegis of the pH buffer mechanism; and (2) H. pylori firmly adheres to gastric mucosa epithelial cells via the outer membrane protein (OMP).

Mucins

Mucins, which are high molecular weight, heavily glycosylated glycoproteins secreted by epithelial cells, play a key role in the adhesion process. Mucins are located on the surface of the stomach cavity and are the main components of the gastric mucosa epithelial mucus layer. At this location, mucins form a barrier in the mucosal defense system that protects gastric epithelial cells against chemical, enzymatic, microbial, and mechanical damage. Mucin-1 (MUC-1), Mucin-5AC (MUC-5AC), and Mucin-6 (MUC-6) are expressed in the gastric mucosa of normal adults, and the genes encoding these mucins are located on different chromosomes. The main structures formed by mucins are protein scaffolds based on the core peptide, the typical structure of which is a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTRs) rich in serine, threonine and proline, which are potential glycosylation sites. One study has to date demonstrated that MUC-5AC and MUC-6 are separated in the gastric mucus gel, resulting in a layered linear array (Ho et al., 2004). The former is mainly found on the surface and bottom of the mucus gel, and the latter is present among the various layers. This natural stratification of mucins increases the viscosity of gastric mucosa epithelial mucus gel and provides an independent system to completely protect gastric mucosa epithelial cells. Therefore, H. pylori must pass through mucins to successfully adhere to to host cells.

Ureases and Motility

Both urease and flagella-mediated, chemosensory-directed motility are essential and relevant to the process of colonization (Eaton et al., 1991, 1996; Nakamura et al., 1998; Rolig et al., 2012). H. pylori secretes a large amount of urease, and the surface-bound enzyme catalyzes hydrolysis of urea to generate ammonia and bicarbonate, which are then released into the cytosol and periplasm, forming a neutral environment around the bacterial cells (Weeks et al., 2000). This process decreases the viscosity and elastic modulus of the mucus layer, which changes from a gel to a viscous solution with increasing pH, thereby facilitating the passage of the bacteria through the mucus. Ammonia protects the metabolic activity of H. pylori, which remains at 50–60% of its normal activity level in the highly acidic environment of pH 2.5 (Celli et al., 2009; Follmer, 2010). Microscopy studies of the motility of H. pylori in the gastric mucosa at acidic and neutral pH values in the absence of urea showed that the bacteria swim freely at high pH but are highly constrained at low pH (Celli et al., 2009). From a hydrodynamics viewpoint, the shape of the H. pylori cell can also affect its swimming speed. Previous studies have suggested that H. pylori possesses numerous long flagella that may allow the cell to swim through the sticky viscoelastic mucus gel in a manner similar to how a screw passes through a cork (Berg and Turner, 1979; Karim et al., 1998). Swimming speeds also decrease with increasing viscosity of the polymer solution (Worku et al., 1999). The results of Martínez et al. (2016) are consistent with the above observations. On this basis, these authors provide an in-depth, quantitative analysis of H. pylori's natural variation in helical cell and flagellum morphology, indicating that both cell shape and flagellum number independently affect swimming speed in viscous environments, with flagellum number contributing to a greater degree. In addition, as for other commensal microbes that colonize a host over long periods of time, H. pylori must sense and integrate many signals emanating from the gastric epithelium that attract the microbes to the cell surface for colonization and persistence. This ability to move in response to chemical cues, i.e., chemotaxis, is determined by the core signaling complex proteins CheW, CheA, and CheY (Beier et al., 1997; Foynes et al., 2000; Pittman et al., 2001). H. pylori also has three membrane-bound chemoreceptors, TlpA, TlpB, and TlpC, and one cytoplasmic chemoreceptor, TlpD (Lertsethtakarn et al., 2011). Rolig et al. (2012) found that different regions of the stomach contain unique chemotactic signals. For example, in the corpus, H. pylori utilizes chemotaxis for initial localization but not for subsequent growth. In contrast, in the antrum and the corpus-antrum transition zone, chemotaxis does not help initial colonization but does promote subsequent proliferation. The main chemoreceptor that allows H. pylori to thrive in the antrum is TlpD, with the other chemoreceptors playing minor roles. Thus, chemotaxis may be necessary to locate the antrum or to maintain colonization at this site. Indeed, chemotaxis of H. pylori toward the urea present on the epithelial cell surface may also be crucial for survival in the stomach (Nakamura et al., 1998). It was recently demonstrated that H. pylori swims toward injured epithelia, suggesting that the bacterial cells are attracted to host-derived molecules (Aihara et al., 2014). The main bacterial chemoreceptor responsible for this chemoattraction is TlpB, and urea has been identified as the host metabolite that attracts H. pylori (Huang et al., 2015). In addition, Huang et al. (2015) revealed a function for H. pylori urease in facilitating sensitive detection of urea at concentrations as low as 50 nanomolar. Therefore, H. pylori has evolved a sensitive urea chemodetection and destruction system involving a high-affinity chemoreceptor-ligand interaction that functions at the nanomolar concentrations created locally by urease, allowing the bacterium to dynamically and locally modify the host environment to locate the epithelium. Overall, we believe that the ability of H. pylori to bore through the mucus gel might be achieved in two ways: flagella and chemotaxis provide some contribution, but changes in the rheological properties of the environment are also important.

Adhesins

Adhesins, which attach to the surface of the bacterium, play a vital role because they can recognize the structures of glycans expressed in the gastric mucosa, and H. pylori must swim through the mucus gel (Ilver et al., 1998; Mahdavi et al., 2002). Using adhesins, H. pylori can identify peptidoglycans on the surface of gastric epithelial cells, molecules that are mainly found on mucins in the gastric mucus gel. Furthermore, any H. pylori cell that does not adhere to an epithelial cell would be quickly removed from the epithelial cell surface and the mucus gel. At present, it is generally believed that OMPs are the main adhesins of H. pylori. Among these adhesins, blood group antigen-binding adhesion (BabA) can identify the difucosylated ABO/Lewis b (LeB) antigen present on red blood cells and gastrointestinal mucosa epithelial cells. In normal gastric tissue, LeB-binding strains always bind to MUC-5AC- and LeB-positive epithelial cells (Van de Bovenkamp et al., 2003). Moreover, the BabA-Leb interaction is important not only for H. pylori to adhere to the stomach surface but also to anchor the bacterial secretion system to the host cell surface for effective injection of bacterial factors into the host cell cytosol, which is the cause of clinical outcomes. In other words, once BabA binds to LeB, Type IV secretion system (TFSS)-dependent host cell signaling is triggered to induce the transcription of genes that enhance inflammation, intestinal metaplasia development, and associated precancerous transformation (Ishijima et al., 2011). Another adhesin is sialic acid-binding adhesion (SabA), which can bind to the antigens Lewis X (sLex) and Lewis a (sLea). Lewis antigens are common in infected and inflamed gastric mucosa (Lindén et al., 2008). SabA expression can rapidly respond to changing conditions in the stomach or in different regions of the stomach that permit H. pylori to adapt to varying microenvironments or host immune responses to ensure long-term colonization and infection (Goodwin et al., 2008). Accordingly, SabA-mediated adherence is positively correlated with the sLex concentration in vitro (Lindén et al., 2004). During persistent infection and chronic inflammation, H. pylori triggers an alteration in the glycosylation patterns in the gastric mucosa, including upregulation of inflammation-associated sLex antigens, and H. pylori is likely to adhere to the gastric mucosa with SabA. In addition, SabA interacting with the sLex antigen can enhance H. pylori colonization in patients with weak or no Leb expression (Yamaoka, 2008). SabA production is indeed reported to be associated with severe intestinal metaplasia, gastric atrophy, and the development of gastric cancer (Yamaoka et al., 2006). However, de Klerk et al. (2016) also found certain Lactobacillus strains could inhibit SabA expression at the transcriptional level by releasing an effector molecule into the medium, further affecting H. pylori binding capacity and thereby reducing its adherence. In particular, Lactobacillus, a well-known member of the normal microbiota in the human gastrointestinal tract, has always been studied in relation to H. pylori but largely as a possible supplement for antibiotic treatment (Patel et al., 2014), and interference with H. pylori colonization may contribute to the molecular mechanism for this association (de Klerk et al., 2016). AlpA and AlpB as OMPs also play a role in adherence to host cells and tissues (Odenbreit et al., 1999, 2002a). The alpAB locus, which is ubiquitously present in H. pylori strains, is expressed during infections (Rokbi et al., 2001; Odenbreit et al., 2009), and alpAB mutants are defective in adherence to human gastric tissue sections (Odenbreit et al., 1999). One study demonstrated that laminin is the host receptor of both AlpA and AlpB, and H. pylori deficient in these factors causes more severe inflammation than the isogenic wild-type strain in gerbils (Senkovich et al., 2011). The reason may be that the alpAB locus influences host cell signaling and cytokine production (Odenbreit et al., 2002a,b; Loke et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2007). H. pylori CagL protein is a specialized adhesin that is targeted to the pilus surface, where it binds to and activates integrin alpha5beta1 receptor on gastric epithelial cells through an arginine-glycine-aspartate motif. This interaction can mediate receptor-dependent delivery of CagA into gastric epithelial cells and may assist in certain intracellular signaling events.(Kwok et al., 2007; Barden et al., 2013). Current evidence suggests that MUC-1 in fact inhibits H. pylori colonization in vitro and in vivo (McGuckin et al., 2007; Lindén et al., 2009). Lindén et al. (2009) showed that MUC1 could inhibit H. pylori binding to epithelial cells, a process that occurs through both BabA and SabA. When the pathogen fails to bind to MUC1, the mucin sterically inhibits adhesion to other potential cell surface ligands. However, when the pathogen does bind to MUC1, the extracellular domain of the mucin is released from the epithelial surface and acts as a releasable decoy to prevent prolonged adherence. H. pylori also can modulate host cell glycosylation patterns to enhance adhesion. A highly pathogenic strain was able to alter expression of β3GlcNAcT5 (β3GnT5), a GlcNAc transferase essential for the biosynthesis of Lewis antigens, to increase sLex expression and H. pylori adhesion in human gastric carcinoma cell lines (Marcos et al., 2008). Furthermore, although the urease and alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpC) located on the surface of H. pylori are not OMPs, these enzymes still have good affinity for stomach mucins because they are components of the membrane (Nilsson et al., 2000). Loke et al. (2007) confirmed that both polysaccharides and mucin could bind to AhpC and UreA, so polysaccharides may function as a potential anti-adhesive agent against H. pylori colonization of gastric mucin by competing for mucin-binding sites. This result indirectly indicated the probable role of these two H. pylori proteins in colonization. Other adhesins, such as HopZ and OipA, are also involved in the adhesion process, though the specific ligands need to be further clarified.

Adherens Junctions

In the gastric mucosa, the basement membrane is separated from the gastric lumen by only a single cell layer, and H. pylori can swim freely in the mucus layer in close contact with the epithelial cells, preferentially at the apical side of intercellular contacts (Hazell et al., 1986; Necchi et al., 2007; Tan et al., 2009). Any damage to the epithelial cell layer will expose extracellular matrix proteins, and disruptions of tight junctions by H. pylori will also allow the bacterial cells access to the basement membrane (Necchi et al., 2007). H. pylori targeting of adherens junctions may be beneficial for colonization and persistence at the host epithelial surface, and it may also cause abnormal receptor activation and stimulation of signaling pathways involved in inflammation, proliferation, migration, and invasion, which will have detrimental consequences and result in disease development (Costa et al., 2013).

Cellular Invasion of H. pylori

Observation In Vivo and In Vitro

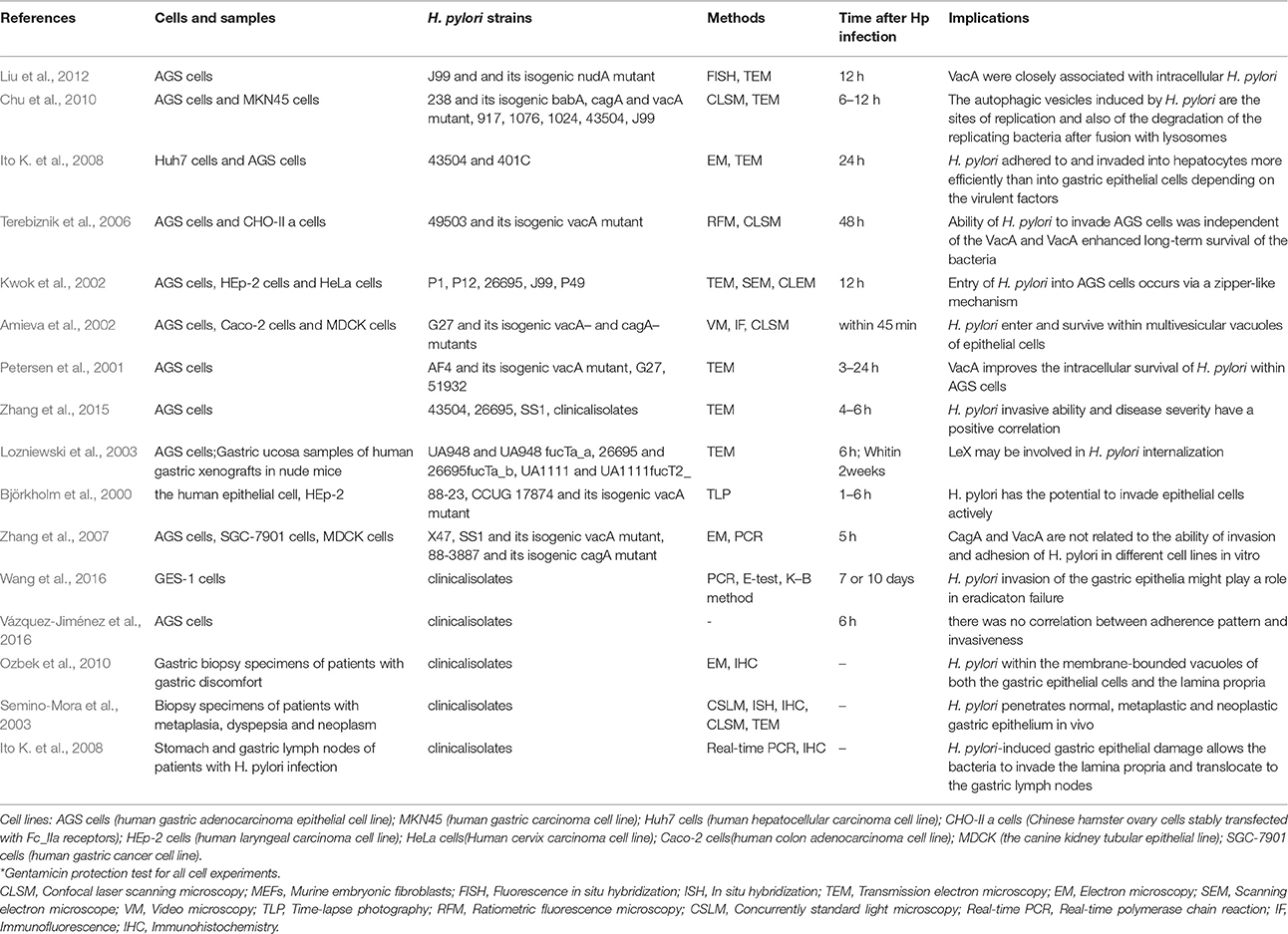

Adhesion is an important step in H. pylori internalization, and invasion has been confirmed in a variety of samples (Table 1). Some in vivo studies demonstrate that H. pylori can invade gastric mucosa lesions in different stages. For instance, invasion was observed in patients with gastritis, ulcers, precancerous lesions and gastric cancer, and the bacteria were able to invade epithelial cells of the stomach and duodenum, parietal cells and immune cells, and even the lamina propria (Noach et al., 1994; el-Shoura, 1995; Papadogiannakis et al., 2000; Semino-Mora et al., 2003; Dubois and Borén, 2007; Necchi et al., 2007; Ozbek et al., 2010). Animals, such as mice, are also susceptible to H. pylori invasion (Oh et al., 2005), and in vitro studies have shown that H. pylori can enter cells. Although H. pylori is a common pathogenic bacterium of the human digestive system, invasion is not limited to cell lines that are closely related to gastric epithelial cells, such as AGS, MKN45, and SGC-7901. Indeed, invasion has been confirmed in the Huh7, HEp-2, and HeLa cell lines, among others (Björkholm et al., 2000; Amieva et al., 2002; Kwok et al., 2002; Terebiznik et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2007; Ito K. et al., 2008).

Invasive ability also varies with the host cell type and H. pylori strain, with a rate of approximately 0.01–0.1% of inoculated bacteria (Rautelin et al., 1995; Burridge and Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, 1996; Amieva et al., 2002; Dubois and Borén, 2007; Ito K. et al., 2008; Chu et al., 2010). Zhang et al. (2007) indicated that the strain 88-3887 can invade cells better than strains SS1 and X47, and each strain had the highest invasive ability in SCG-7901 cells. As H. pylori typically does not possess the ability to enter cells freely, most of the bacterial cells are internalized into the cytoplasm via endocytosis (Ozbek et al., 2010). A study from Stanford University (Amieva et al., 2002) showed that due to the innate immune response, cells can form phagocytic vesicles that wrap around H. pylori after cellular entry, even though the vesicles were immature. The encapsulated H. pylori cells were not swallowed or digested; instead, the vesicle acted as a protective barrier, allowing the microbes to evade the immune response.

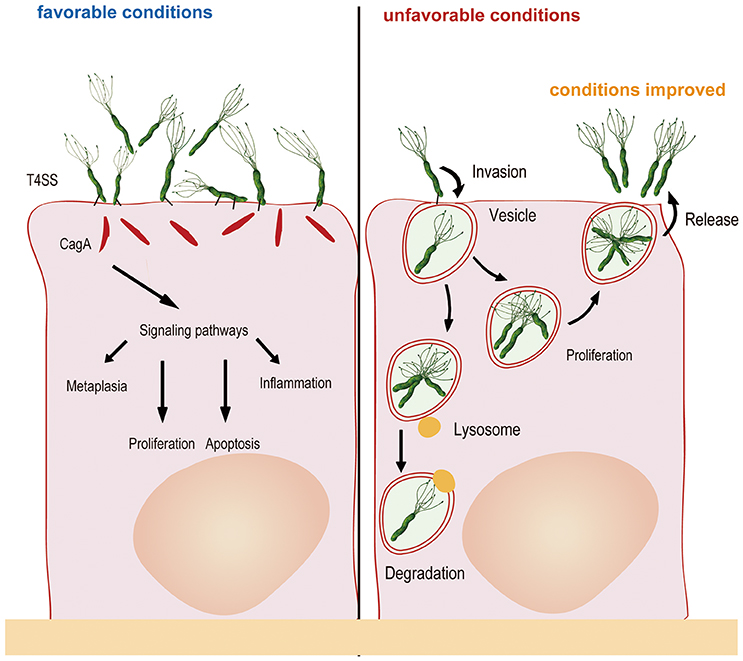

These investigators also used differential immune fluorescence staining and live video microscopy to further investigate the physiological activities of internalized H. pylori and found that internalization occurred within 45 min of bacterial attachment to the cell surface. The bacterial cells then entered vacuoles and remained viable for at least 48 h. However, replication of the internalized H. pylori cells was not observed in the study, perhaps because of the short monitoring time and because the intracellular milieu was not suitable for bacterial replication (Amieva et al., 2002). Nonetheless, a most recent study found that H. pylori could proliferate in cells: two cells lines (AGS and MKN45) were evaluated in gentamicin protection experiments, revealing that H. pylori could proliferate after entering the cells, with the maximum number of bacterial cells observed after 6–12 h (van der Wouden et al., 1999; Rokkas et al., 2009; Chu et al., 2010). Zhang et al. (2015) also observed this phenomenon in their study, whereby H. pylori attached to the cell membrane and combined with cellular microvilli after 2.5 h of infection. After invasion, double-layer membrane vesicles surrounded the H. pylori cells (4 h). At 6 h after infection, invasion reached a peak, with many bacteria observed in the cytoplasm. Bacterial adhesion, invasion, division and lysis were observed after 12 h, and most of the intracellular bacterial cells had lysed at 24 h. Another study confirmed that autophagosomes form to degrade ingested H. pylori through the lysosomal killing mechanism at 24 h after invasion (Chu et al., 2010). H. pylori possesses sophisticated mechanisms. For example, the bacterium seeks refuge inside host cells when the external environment changes and becomes unsuitable for survival; once the external conditions become suitable for survival, undegraded H. pylori is released from host cells into the external environment at the appropriate time. In vitro experiments have shown that when gentamicin was removed, viable H. pylori repopulates the extracellular environment, in parallel with a decrease in the number of intravacuolar bacteria (Amieva et al., 2002). Regardless, how H. pylori exits the intracellular space remains unclear. It is possible that viable bacteria are released as infected cells die. Vacuoles containing live H. pylori resemble multivesicular bodies, which, in some cell types, are capable of exocytosis and thus release their contents into the extracellular medium (Amieva et al., 2002). In brief, the number of bacteria in the cell is maintained through a dynamic process involving invasion, proliferation, apoptosis and release (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Generally, H. pylori adheres to gastric mucosa epithelial cells via the outer membrane protein and injects CagA into host cells via a type IV secretory system, resulting in changes in cytokine signaling and cell cycle control. When the external environment changes and becomes unfavorable, H. pylori invades the epithelial cells and multiplies in double-layer membrane vesicles to seek refuge. After internalization, autophagosomes form to degrade some of the ingested bacteria. Once the external environment becomes favorable, undegraded H. pylori is released from host cells into the external environment for recolonization.

To some extent, these findings provide a clear explanation for repeated infection by H. pylori: bacterial cells could escape the immune response of epithelial cells after invasion, and the amount and pathogenicity of the bacteria do not decrease during this process. Such a process might be a strategy for H. pylori to escape immune surveillance and remain alive in vivo (Amieva et al., 2002; Dubois and Borén, 2007), and it contributes to the complication of eradication. To determine whether H. pylori internalization plays a role in treatment failure, one study (Wang et al., 2016) carried out in our laboratory applied an invasion assay to evaluate the levels of H. pylori invasion of GES-1 cells. The results showed that the internalization levels of the failing strains were higher than those of the successful strains. However, there is no consensus regarding whether the level of internalization is related to antibiotic resistance, with some studies considering that resistant strains are associated with significantly higher internalization activity than susceptible strains (Lai et al., 2006) but Wang et al. (2016) reporting no evidence of this. Regardless of the correlation, once therapy fails, more consideration should be given to H. pylori internalization activity.

Invasion Mechanisms

There is increasing research on the invasion mechanism of invasive bacteria, and invasion could proceed by direct engagement of surface host cell receptors or by direct translocation of bacterial proteins into the host-cell cytosol that promote rearrangements of the plasma membrane architecture and induce pathogen engulfment. The former is the “zipper” mechanism, and Yersinia and Listeria invade cells in this manner. The latter is the “trigger” mechanism, which is used by such bacteria as Escherichia coli, and Shigella, Salmonella (Pizarro-Cerdá and Cossart, 2006). The invasion mechanism of H. pylori remains unclear to date. Kwok et al. (2002) found that H. pylori invasion of AGS cells involves close contact with microvilli on the cell membrane and activation of tyrosine phosphorylation signals. Su et al. (1999) reported that H. pylori enters cultured AGS cells via the beta 1 integrin receptor in a tyrosine kinase-dependent manner. Other researchers report that H. pylori enters cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis, which requires cytoskeletal rearrangement (Evans et al., 1992; Birkness et al., 1996). Given the close relationship between beta 1 integrin, the cytoskeleton and the pathogenicity of internalized H. pylori, Ito K. et al. (2008) used a beta 1 integrin antibody to block the binding of H. pylori to the corresponding receptor on the cell membrane and used cytochalasin D to block intracellular actin polymerization. These experiments were performed to further observe changes in the invasive capability of H. pylori, and the results showed that the number of internalized bacteria decreased substantially after application of these factors. Moreover, the effect of cytochalasin D was more effective than that of the beta 1 integrin antibody, though neither was able to completely block invasion, suggesting that other unidentified and unconfirmed pathways mediate the activities of H. pylori. Furthermore, the role of bacterial virulence factors in this process is unclear. As mentioned above, H. pylori is enveloped by double-layer membrane vesicles after invasion. Amieva et al. (2002) found that vacuoles have the same morphology as late endosomal multivesicular bodies induced by vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA). The role of VacA in inducing vacuolization is known, and the effect of VacA in H. pylori invasiveness has also been reported. Some previous studies (Amieva et al., 2002; Terebiznik et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2007; Chu et al., 2010) showed that VacA did not influence the cell-invasion capability of H. pylori. Although the bacterial cells were found in vacuoles formed through a VacA-dependent process, the researchers proposed that VacA only affects the survival and multiplication of internalized H. pylori. However, an in vitro study revealed increased internalization in a strain producing the vacuolating cytotoxin compared to an isogenic VacA knockout mutant (Björkholm et al., 2000). Petersen et al. (2001) also found that the vacuolating cytotoxin of H. pylori can improve its intracellular survival in AGS cells. More remarkably, VacA could disrupt autophagy during chronic infection, thereby resulting in a failure to clear the bacteria to promote intracellular survival (Raju et al., 2012). This is different from our previous understanding that autophagy can be induced as an innate defense mechanism to protect against H. pylori infection (Orvedahl and Levine, 2009). This phenomenon is mainly due to the length of exposure time. During initial infection, bacterial load and levels of VacA may be low, and host cell autophagy plays an important role in clearance of bacteria; During chronic infection, prolonged exposure to VacA will make immature autophagosomes form (Raju et al., 2012). Ito K. et al. (2008) also used two types of H. pylori differing in virulence to compare invasive ability and found better virulence and invasiveness in the strain harboring the cag pathogenicity island (PAI), Vac A, OipA, and BabA isogenes. Based on this evidence, virulence factors also play a role in cell invasion, even though the role of each factor in internalization remains unclear and awaits clarification by experiments involving isogenic mutants. Conversely, a study from China found the opposite result: invasive ability was associated with the VacA mid-region and not with cytotoxin-associated gene A (Cag A), Cag A-EPIYA, or Cag E (Zhang et al., 2015). Therefore, the role of bacterial virulence factors requires more research. In addition, as Nudix enzymes are typically involved in bacterial invasion of eukaryotic cells (Maki and Sekiguchi, 1992), some authors speculate that H. pylori invasin may play a role in the entry of the bacterium into epithelial cells because the Nudix hydrolase NudA can degrade toxic substances induced during invasion (Lundin et al., 2003). Originally, Lundin et al. (2003) found no quantifiable differences in invasion frequency for the H. pylori NudA J99 mutant compared to WT when using a gentamicin protection assay. Liu et al. (2012) confirmed the previous report, utilizing FISH and an ultrastructural approach to make changes to the “classical” gentamicin protection assay and demonstrating significantly more intracellular and fewer membrane-bound H. pylori in WT-infected AGS cells than in cells infected with a mutant carrying a ΔnudA allele. These observations indicated that NudA plays a biologically significant role in H. pylori entry into host cells and emphasized that the sensitivity of the “classical” assay may not be sufficient to demonstrate differences in invasion capacity. This lack of sensitivity may be due to the fact that complete killing of extracellular bacteria is rarely achieved (Amieva et al., 2002).

Another concern is the invasiveness of H. pylori. As mentioned above, binding of the bacterium to the cell membrane is needed prior to internalization, and it is unclear whether there is any association between adherence pattern and invasiveness. Vázquez-Jiménez et al. (2016) found that H. pylori strains exhibiting localized adherence would be more reactive toward gastric epithelial cells compared to the strains exhibiting diffused adherence; this would result in more damage and more proinflammatory signals but has no significant association with invasiveness. However, another report showed a specific ratio of invasive and adherent H. pylori (Demirel et al., 2013). Zhang et al. (2015) found no significant differences among various strains with regard to the ratio of invasion and adhesion, a finding that shows that the amount of adherent bacteria rather than the bacterial strain determines the final amount of invasive bacteria. Adhesion is the single major determinant for cell invasion by H. pylori, and many researchers have performed various invasion experiments to further investigate this process. In an in vitro study, Kwok et al. (2002) found the level of H. pylori entry into epithelial cells to be within the same range as that of other known invasive pathogens, such as Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. They also observed greater H. pylori uptake by AGS cells than by HeLa or HEp-2 cells, indicating that uptake mainly depends on the host cell type.

Association with Pathogenesis

The pathogenicity of bacteria that colonize the human mucosa is influenced by their capacity to invade and survive within epithelial cells. However, whether H. pylori internalization affects pathogenicity remains controversial. An in vivo study showed a positive correlation between the invasive ability of H. pylori and disease severity, and the average invasion rates of H. pylori strains found in gastric cancer and ulcers were higher than the rate of strains found in gastritis (Zhang et al., 2015). Moreover, many studies have confirmed that internalized H. pylori is pathogenic and able to express the virulence proteins Cag A and Vac A (Semino-Mora et al., 2003; Dubois and Borén, 2007; Necchi et al., 2007; Ito T. et al., 2008; Chu et al., 2010). Internalized H. pylori can also activate the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling pathway and induce interleukin-8 (IL-8) secretion, which suggests that invasion by this bacterium might be an important strategy in the development of H. pylori-associated diseases (Zhang et al., 2015). In addition, in vivo and in vitro studies show an association between internalized H. pylori and cell damage as well as cell disintegration (el-Shoura, 1995; Wilkinson et al., 1998). Ito T. et al. (2008) even found that H. pylori-induced gastric epithelial damage allows the bacterial cells to invade the lamina propria and translocate to the gastric lymph nodes, which may chronically stimulate the immune system. Additionally, the bacterial cells, alive or not, captured by macrophages may contribute to the induction and development of H. pylori-induced chronic gastritis.

Conclusions

H. pylori is the main pathogenic bacteria of chronic active gastritis, peptic ulcers, gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric cancer. This bacterium seeks refuge inside cells when the external environment is not suitable, and it can also complete an entire biological cycle, including proliferation and apoptosis, within gastric epithelial cells. Furthermore, once the external conditions become suitable, undegraded H. pylori cells leave the host cell and can be released to infect other cells and cause repeated infection. The above findings suggest that invasion plays an important role in the induction of disease, immune escape and chronic infection. Moreover, these results provide a new direction for research on the pathogenic mechanism of H. pylori-associated gastric diseases. The latest consensus recommendations for treating H. pylori infection are non-bismuth quadruple therapy and traditional bismuth quadruple therapy as first-line strategies (Fallone et al., 2016). To date, studies on the reasons for eradication failure have concentrated on antibiotic resistance. However, H. pylori internalization provides a new research focus. The antibiotics in the recommended regimens include both cell membrane-penetrating antibiotics, such as clarithromycin or metronidazole, and antibiotics that do not penetrate the cell membrane, such as amoxicillin. Increasing the concentration and treatment time of cell membrane-penetrating antibiotics that effectively penetrate epithelial cells to kill intracellular H. pylori might help in achieving complete eradication.

Author Contributions

YH, QW, DC, WX, and NL contributed equally to this review.

Disclosures

Language has been improved by the company named AJE.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81060038 and 81270479) and grants from the Jiangxi Province Talent 555 Project.

References

Aihara, E., Closson, C., Matthis, A. L., Schumacher, M. A., Engevik, A. C., Zavros, Y., et al. (2014). Motility and chemotaxis mediate the preferential colonization of gastric injury sites by Helicobacter pylori. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004275. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004275

Amieva, M. R., Salama, N. R., Tompkins, L. S., and Falkow, S. (2002). Helicobacter pylori enter and survive within multivesicular vacuoles of epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 4, 677–690. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00222.x

Barden, S., Lange, S., Tegtmeyer, N., Conradi, J., Sewald, N., Backert, S., et al. (2013). A helical RGD motif promoting cell adhesion: crystal structures of the Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system pilus protein CagL. Structure 21, 1931–1941. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.018

Beier, D., Spohn, G., Rappuoli, R., and Scarlato, V. (1997). Identification and characterization of an operon of Helicobacter pylori that is involved in motility and stress adaptation. J. Bacteriol. 179, 4676–4683.

Berg, H. C., and Turner, L. (1979). Movement of microorganisms in viscous environments. Nature 278, 349–351. doi: 10.1038/278349a0

Birkness, K. A., Gold, B. D., White, E. H., Bartlett, J. H., and Quinn, F. D. (1996). In vitro models to study attachment and invasion of Helicobacter pylori. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 797, 293–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb52983.x

Björkholm, B., Zhukhovitsky, V., Löfman, C., Hultén, K., Enroth, H., Block, M., et al. (2000). Helicobacter pylori entry into human gastric epithelial cells: a potential determinant of virulence, persistence, and treatment failures. Helicobacter 5, 148–154. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00023.x

Boreiri, M., Samadi, F., Etemadi, A., Babaei, M., Ahmadi, E., Sharifi, A. H., et al. (2013). Gastric cancer mortality in a high incidence area: long-term follow-up of Helicobacter pylori-related precancerous lesions in the general population. Arch. Iran. Med. 16, 343–347.

Brown, L. M. (2000). Helicobacter pylori: Epidemiology and routes of transmission. Epidemiol. Rev. 22, 283–297. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018040

Burridge, K., and Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, M. (1996). Focal adhesions, contractility, and signaling. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 463–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.463

Celli, J. P., Turner, B. S., Afdhal, N. H., Keates, S., Ghiran, I., Kelly, C. P., et al. (2009). Helicobacter pylori moves through mucus by reducing mucin viscoelasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14321–14326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903438106

Chu, Y. T., Wang, Y. H., Wu, J. J., and Lei, H. Y. (2010). Invasion and multiplication of Helicobacter pylori in gastric epithelial cells and implications for antibiotic resistance. Infect. Immun. 78, 4157–4165. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00524-10

Cirak, M. Y., Akyön, Y., and Mégraud, F. (2007). Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 12 (Suppl. 1), 4–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00542.x

Correa, P. (1992). Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process–first American Cancer Society award lecture on cancer epidemiology and prevention. Cancer Res. 52, 6735–6740.

Costa, A. M., Leite, M., Seruca, R., and Figueiredo, C. (2013). Adherens junctions as targets of microorganisms: a focus on Helicobacter pylori. FEBS Lett. 587, 259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.12.008

de Klerk, N., Maudsdotter, L., Gebreegziabher, H., Saroj, S. D., Eriksson, B., Eriksson, O. S., et al. (2016). Lactobacilli reduce Helicobacter pylori attachment to host gastric epithelial cells by inhibiting adhesion Gene expression. Infect. Immun. 84, 1526–1535. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00163-16

Demirel, B. B., Akkas, B. E., and Vural, G. U. (2013). Clinical factors related with Helicobacter pylori infection–is there an association with gastric cancer history in first-degree family members? Asian. Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 14, 1797–1802. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.3.1797

Dubois, A., and Borén, T. (2007). Helicobacter pylori is invasive and it may be a facultative intracellular organism. Cell. Microbiol. 9, 1108–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00921.x

Eaton, K. A., Brooks, C. L., Morgan, D. R., and Krakowka, S. (1991). Essential role of urease in pathogenesis of gastritis induced by Helicobacter pylori in gnotobiotic piglets. Infect. Immun. 59, 2470–2475.

Eaton, K. A., Suerbaum, S., Josenhans, C., and Krakowka, S. (1996). Colonization of gnotobiotic piglets by Helicobacter pylori deficient in two flagellin genes. Infect. Immun. 64, 2445–2448.

el-Shoura, S. M. (1995). Helicobacter pylori: I. Ultrastructural sequences of adherence, attachment, and penetration into the gastric mucosa. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 19, 323–333. doi: 10.3109/01913129509064237

Eslick, G. D., Lim, L. L., Byles, J. E., Xia, H. H., and Talley, N. J. (1999). Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastric carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 94, 2373–2379. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01360.x

Evans, D. G., Evans, D. J., and Graham, D. Y. (1992). Adherence and internalization of Helicobacter pylori by HEp-2 cells. Gastroenterology 102, 1557–1567. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91714-F

Fallone, C. A., Chiba, N., van Zanten, S. V., Fischbach, L., Gisbert, J. P., Hunt, R. H., et al. (2016). The Toronto consensus for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in adults. Gastroenterology 151, 51–69.e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.04.006

Follmer, C. (2010). Ureases as a target for the treatment of gastric and urinary infections. J. Clin. Pathol. 63, 424–430. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2009.072595

Foynes, S., Dorrell, N., Ward, S. J., Stabler, R. A., McColm, A. A., Rycroft, A. N., et al. (2000). Helicobacter pylori possesses two CheY response regulators and a histidine kinase sensor, CheA, which are essential for chemotaxis and colonization of the gastric mucosa. Infect. Immun. 68, 2016–2023. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.4.2016-2023.2000

Goh, K. L., Chan, W. K., Shiota, S., and Yamaoka, Y. (2011). Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and public health implications. Helicobacter 16 (Suppl. 1), 1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00874.x

Goodwin, A. C., Weinberger, D. M., Ford, C. B., Nelson, J. C., Snider, J. D., Hall, J. D., et al. (2008). Expression of the Helicobacter pylori adhesin SabA is controlled via phase variation and the ArsRS signal transduction system. Microbiology 154, 2231–2240. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/016055-0

Hazell, S. L., Lee, A., Brady, L., and Hennessy, W. (1986). Campylobacter pyloridis and gastritis: association with intercellular spaces and adaptation to an environment of mucus as important factors in colonization of the gastric epithelium. J. Infect. Dis. 153, 658–663. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.4.658

Helicobacter Cancer Collaborative Group (2001). Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 49, 347–353. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347

Hessey, S. J., Spencer, J., Wyatt, J. I., Sobala, G., Rathbone, B. J., Axon, A. T., et al. (1990). Bacterial adhesion and disease activity in Helicobacter associated chronic gastritis. Gut 31, 134–138. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.2.134

Ho, S. B., Takamura, K., Anway, R., Shekels, L. L., Toribara, N. W., and Ota, H. (2004). The adherent gastric mucous layer is composed of alternating layers of MUC5AC and MUC6 mucin proteins. Dig. Dis. Sci. 49, 1598–1606. doi: 10.1023/B:DDAS.0000043371.12671.98

Hosseini, E., Poursina, F., de Wiele, T. V., Safaei, H. G., and Adibi, P. (2012). Helicobacter pylori in Iran: a systematic review on the association of genotypes and gastroduodenal diseases. J. Res. Med. Sci. 17, 280–292.

Huang, J. Q., Sridhar, S., Chen, Y., and Hunt, R. H. (1998). Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology 114, 1169–1179.

Huang, J. Y., Sweeney, E. G., Sigal, M., Zhang, H. C., Remington, S. J., Cantrell, M. A., et al. (2015). Chemodetection and destruction of host urea allows Helicobacter pylori to locate the epithelium. Cell Host Microbe 18, 147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.07.002

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (1994). Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum. 61, 1–241.

Ilver, D., Arnqvist, A., Ogren, J., Frick, I. M., Kersulyte, D., Incecik, E. T., et al. (1998). Helicobacter pylori adhesin binding fucosylated histo-blood group antigens revealed by retagging. Science 279, 373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.373

Ishijima, N., Suzuki, M., Ashida, H., Ichikawa, Y., Kanegae, Y., Saito, I., et al. (2011). BabA-mediated adherence is a potentiator of the Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system activity. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 25256–25264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.233601

Ito, K., Yamaoka, Y., Ota, H., El-Zimaity, H., and Graham, D. Y. (2008). Adherence, internalization, and persistence of Helicobacter pylori in hepatocytes. Dig. Dis. Sci. 53, 2541–2549. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0164-z

Ito, T., Kobayashi, D., Uchida, K., Takemura, T., Nagaoka, S., Kobayashi, I., et al. (2008). Helicobacter pylori invades the gastric mucosa and translocates to the gastric lymph nodes. Lab. Invest. 88, 664–681. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.33

Jang, S. H., Cho, S., Lee, E. S., Kim, J. M., and Kim, H. (2013). The phenyl-thiophenyl propenone RK-I-123 reduces the levels of reactive oxygen species and suppresses the activation of NF-κB and AP-1 and IL-8 expression in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric epithelial AGS cells. Inflamm. Res. 62, 689–696. doi: 10.1007/s00011-013-0621-4

Kamangar, F., Dawsey, S. M., Blaser, M. J., Perez-Perez, G. I., Pietinen, P., Newschaffer, C. J., et al. (2006). Opposing risks of gastric cardia and noncardia gastric adenocarcinomas associated with Helicobacter pylori seropositivity. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 98, 1445–1452. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj393

Karim, Q. N., Logan, R. P., Puels, J., Karnholz, A., and Worku, M. L. (1998). Measurement of motility of Helicobacter pylori, Campylobacter jejuni, and Escherichia coli by real time computer tracking using the Hobson BacTracker. J. Clin. Pathol. 51, 623–628. doi: 10.1136/jcp.51.8.623

Kim, N., Marcus, E. A., Wen, Y., Weeks, D. L., Scott, D. R., Jung, H. C., et al. (2004). Genes of Helicobacter pylori regulated by attachment to AGS cells. Infect. Immun. 72, 2358–2368. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2358-2368.2004

Kwok, T., Backert, S., Schwarz, H., Berger, J., and Meyer, T. F. (2002). Specific entry of Helicobacter pylori into cultured gastric epithelial cells via a zipper-like mechanism. Infect. Immun. 70, 2108–2120. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2108-2120.2002

Kwok, T., Zabler, D., Urman, S., Rohde, M., Hartig, R., Wessler, S., et al. (2007). Helicobacter exploits integrin for type IV secretion and kinase activation. Nature. 449, 862–866. doi: 10.1038/nature06187

Lai, C. H., Kuo, C. H., Chen, P. Y., Poon, S. K., Chang, C. S., and Wang, W. C. (2006). Association of antibiotic resistance and higher internalization activity in resistant Helicobacter pylori isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57, 466–471. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki479

Lertsethtakarn, P., Ottemann, K. M., and Hendrixson, D. R. (2011). Motility and chemotaxis in Campylobacter and Helicobacter. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65, 389–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102908

Lindén, S., Borén, T., Dubois, A., and Carlstedt, I. (2004). Rhesus monkey gastric mucins: oligomeric structure, glycoforms and Helicobacter pylori binding. Biochem. J. 379, 765–775. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031557

Lindén, S. K., Sheng, Y. H., Every, A. L., Miles, K. M., Skoog, E. C., Florin, T. H., et al. (2009). MUC1 limits Helicobacter pylori infection both by steric hindrance and by acting as a releasable decoy. PLOS Pathog. 5:e1000617. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000617

Lindén, S., Mahdavi, J., Semino-Mora, C., Olsen, C., Carlstedt, I., Borén, T., et al. (2008). Role of ABO secretor status in mucosal innate immunity and H. pylori infection. PLOS Pathog. 4:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040002

Liu, H., Semino-Mora, C., and Dubois, A. (2012). Mechanism of H. pylori intracellular entry: an in vitro study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2:13. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00013

Loke, M. F., Lui, S. Y., Ng, B. L., Gong, M., and Ho, B. (2007). Antiadhesive property of microalgal polysaccharide extract on the binding of Helicobacter pylori to gastric mucin. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 50, 231–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00248.x

Lozniewski, A., Haristoy, X., Rasko, D. A., Hatier, R., Plenat, F., Taylor, D. E., et al. (2003). Influence of Lewis antigen expression by Helicobacter pylori on bacterial internalization by gastric epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 71, 2902–2906. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2902-2906.2003

Lu, H., Wu, J. Y., Beswick, E. J., Ohno, T., Odenbreit, S., Haas, R., et al. (2007). Functional and intracellular signaling differences associated with the Helicobacter pylori AlpAB adhesin from Western and East Asian strains. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 6242–6254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611178200

Lundin, A., Nilsson, C., Gerhard, M., Andersson, D. I., Krabbe, M., and Engstrand, L. (2003). The NudA protein in the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori is an ubiquitous and constitutively expressed dinucleoside polyphosphate hydrolase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 12574–12578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212542200

Mahdavi, J., Sondén, B., Hurtig, M., Olfat, F. O., Forsberg, L., Roche, N., et al. (2002). Helicobacter pylori SabA adhesin in persistent infection and chronic inflammation. Science 297, 573–578. doi: 10.1126/science.1069076

Maki, H., and Sekiguchi, M. (1992). MutT protein specifically hydrolyses a potent mutagenic substrate for DNA synthesis. Nature 355, 273–275. doi: 10.1038/355273a0

Marcos, N. T., Magalhães, A., Ferreira, B., Oliveira, M. J., Carvalho, A. S., Mendes, N., et al. (2008). Helicobacter pylori induces beta3GnT5 in human gastric cell lines, modulating expression of the SabA ligand sialyl-Lewis x. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 2325–2336. doi: 10.1172/JCI34324

Marshall, B. J., and Warren, J. R. (1983). Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet 1:1273.

Marshall, B. J., and Warren, J. R. (1984). Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet 1, 1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91816-6

Martínez, L. E., Hardcastle, J. M., Wang, J., Pincus, Z., Tsang, J., Hoover, T. R., et al. (2016). Helicobacter pylori strains vary cell shape and flagellum number to maintain robust motility in viscous environments. Mol. Microbiol. 99, 88–110. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13218

McGuckin, M. A., Every, A. L., Skene, C. D., Linden, S. K., Chionh, Y. T., Swierczak, A., et al. (2007). Muc1 mucin limits both Helicobacter pylori colonization of the murine gastric mucosa and associated gastritis. Gastroenterology 133, 1210–1218. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.003

Moujaber, T., MacIntyre, C. R., Backhouse, J., Gidding, H., Quinn, H., and Gilbert, G. L. (2008). The seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in Australia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 12, 500–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.01.011

Nakamura, H., Yoshiyama, H., Takeuchi, H., Mizote, T., Okita, K., and Nakazawa, T. (1998). Urease plays an important role in the chemotactic motility of Helicobacter pylori in a viscous environment. Infect. Immun. 66, 4832–4837.

Necchi, V., Candusso, M. E., Tava, F., Luinetti, O., Ventura, U., Fiocca, R., et al. (2007). Intracellular, intercellular, and stromal invasion of gastric mucosa, preneoplastic lesions, and cancer by Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 132, 1009–1023. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.049

Nilsson, I., Utt, M., Nilsson, H. O., Ljungh, A., and Wadström, T. (2000). Two-dimensional electrophoretic and immunoblot analysis of cell surface proteins of spiral-shaped and coccoid forms of Helicobacter pylori. Electrophor. 21, 2670–2677. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(20000701)21:13<2670::AID-ELPS2670>3.0.CO;2-5

Noach, L. A., Rolf, T. M., and Tytgat, G. N. (1994). Electron microscopic study of association between Helicobacter pylori and gastric and duodenal mucosa. J. Clin. Pathol. 47, 699–704. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.8.699

Noto, J. M., and Peek, R. M. (2012). Helicobacter pylori: an overview. Methods Mol. Biol. 921, 7–10. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-005-2_2

Odenbreit, S., Faller, G., and Haas, R. (2002a). Role of the alpAB proteins and lipopolysaccharide in adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric tissue. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292, 247–256. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00204

Odenbreit, S., Kavermann, H., Püls, J., and Haas, R. (2002b). CagA tyrosine phosphorylation and interleukin-8 induction by Helicobacter pylori are independent from alpAB, HopZ and bab group outer membrane proteins. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292, 257–266. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00205

Odenbreit, S., Swoboda, K., Barwig, I., Ruhl, S., Borén, T., Koletzko, S., et al. (2009). Outer membrane protein expression profile in Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates. Infect. Immun. 77, 3782–3790. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00364-09

Odenbreit, S., Till, M., Hofreuter, D., Faller, G., and Haas, R. (1999). Genetic and functional characterization of the alpAB gene locus essential for the adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric tissue. Mol. Microbiol. 31, 1537–1548. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01300.x

Oh, J. D., Karam, S. M., and Gordon, J. I. (2005). Intracellular Helicobacter pylori in gastric epithelial progenitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5186–5191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407657102

Orvedahl, A., and Levine, B. (2009). Eating the enemy within: autophagy in infectious diseases. Cell Death Differ. 16, 57–69. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.130

Ozbek, A., Ozbek, E., Dursun, H., Kalkan, Y., and Demirci, T. (2010). Can Helicobacter pylori invade human gastric mucosa? An in vivo study using electron microscopy, immunohistochemical methods, and real-time polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 44, 416–422. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181c21c69

Papadogiannakis, N., Willén, R., Carlén, B., Sjöstedt, S., Wadström, T., and Gad, A. (2000). Modes of adherence of Helicobacter pylori to gastric surface epithelium in gastroduodenal disease: a possible sequence of events leading to internalisation. APMIS 108, 439–447. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2000.d01-80.x

Parreira, P., Magalhães, A., Reis, C. A., Borén, T., Leckband, D., and Martins, M. C. (2013). Bioengineered surfaces promote specific protein-glycan mediated binding of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Acta Biomater. 9, 8885–8893. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.06.042

Patel, A., Shah, N., and Prajapati, J. B. (2014). Clinical application of probiotics in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection–a brief review. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 47, 429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2013.03.010

Peek, R. M., and Blaser, M. J. (2002). Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc703

Petersen, A. M., and Krogfelt, K. A. (2003). Helicobacter pylori: an invading microorganism? A review. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 36, 117–126. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00020-8

Petersen, A. M., Sørensen, K., Blom, J., and Krogfelt, K. A. (2001). Reduced intracellular survival of Helicobacter pylori vacA mutants in comparison with their wild-types indicates the role of VacA in pathogenesis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 30, 103–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2001.tb01556.x

Pittman, M. S., Goodwin, M., and Kelly, D. J. (2001). Chemotaxis in the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori: different roles for CheW and the three CheV paralogues, and evidence for CheV2 phosphorylation. Microbiology 147, 2493–2504. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-9-2493

Pizarro-Cerdá, J., and Cossart, P. (2006). Bacterial adhesion and entry into host cells. Cell 124, 715–727. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.012

Raju, D., Hussey, S., Ang, M., Terebiznik, M. R., Sibony, M., Galindo-Mata, E., et al. (2012). Vacuolating cytotoxin and variants in Atg16L1 that disrupt autophagy promote Helicobacter pylori infection in humans. Gastroenterology 142, 1160–1171. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.043

Rautelin, H., Kihlström, E., Jurstrand, M., and Danielsson, D. (1995). Adhesion to and invasion of HeLa cells by Helicobacter pylori. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 282, 50–53. doi: 10.1016/S0934-8840(11)80796-6

Rokbi, B., Seguin, D., Guy, B., Mazarin, V., Vidor, E., Mion, F., et al. (2001). Assessment of Helicobacter pylori gene expression within mouse and human gastric mucosae by real-time reverse transcriptase PCR. Infect. Immun. 69, 4759–4766. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.8.4759-4766.2001

Rokkas, T., Sechopoulos, P., Robotis, I., Margantinis, G., and Pistiolas, D. (2009). Cumulative H. pylori eradication rates in clinical practice by adopting first and second-line regimens proposed by the Maastricht III consensus and a third-line empirical regimen. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 104, 21–25. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.87

Rolig, A. S., Shanks, J., Carter, J. E., and Ottemann, K. M. (2012). Helicobacter pylori requires TlpD-driven chemotaxis to proliferate in the antrum. Infect. Immun. 80, 3713–3720. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00407-12

Schreiber, S., Konradt, M., Groll, C., Scheid, P., Hanauer, G., Werling, H. O., et al. (2004). The spatial orientation of Helicobacter pylori in the gastric mucus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 5024–5029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308386101

Semino-Mora, C., Doi, S. Q., Marty, A., Simko, V., Carlstedt, I., and Dubois, A. (2003). Intracellular and interstitial expression of Helicobacter pylori virulence genes in gastric precancerous intestinal metaplasia and adenocarcinoma. J. Infect. Dis. 187, 1165–1177. doi: 10.1086/368133

Senkovich, O. A., Yin, J., Ekshyyan, V., Conant, C., Traylor, J., Adegboyega, P., et al. (2011). Helicobacter pylori AlpA and AlpB bind host laminin and influence gastric inflammation in gerbils. Infect. Immun. 79, 3106–3116. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01275-10

Siao, D., and Somsouk, M. (2014). Helicobacter pylori: evidence-based review with a focus on immigrant populations. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 29, 520–528. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2630-y

Su, B., Johansson, S., Fällman, M., Patarroyo, M., Granström, M., and Normark, S. (1999). Signal transduction-mediated adherence and entry of Helicobacter pylori into cultured cells. Gastroenterology 117, 595–604. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70452-X

Tan, S., Tompkins, L. S., and Amieva, M. R. (2009). Helicobacter pylori usurps cell polarity to turn the cell surface into a replicative niche. PLOS Pathog. 5:e1000407. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000407

Terebiznik, M. R., Vazquez, C. L., Torbicki, K., Banks, D., Wang, T., Hong, W., et al. (2006). Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin promotes bacterial intracellular survival in gastric epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 74, 6599–6614. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01085-06

Van de Bovenkamp, J. H., Mahdavi, J., Korteland-Van Male, A. M., Büller, H. A., Einerhand, A. W., Borén, T., et al. (2003). The MUC5AC glycoprotein is the primary receptor for Helicobacter pylori in the human stomach. Helicobacter 8, 521–532. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00173.x

van der Wouden, E. J., Thijs, J. C., van Zwet, A. A., Sluiter, W. J., and Kleibeuker, J. H. (1999). The influence of in vitro nitroimidazole resistance on the efficacy of nitroimidazole-containing anti-Helicobacter pylori regimens: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 94, 1751–1759. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01202.x

Vázquez-Jiménez, F. E., Torres, J., Flores-Luna, L., Cerezo, S. G., and Camorlinga-Ponce, M. (2016). Patterns of adherence of Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates to epithelial cells, and its association with disease and with virulence factors. Helicobacter 21, 60–68. doi: 10.1111/hel.12230

Wang, C., Yuan, Y., and Hunt, R. H. (2007). The association between Helicobacter pylori infection and early gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 102, 1789–1798. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01335.x

Wang, F., Meng, W., Wang, B., and Qiao, L. (2014). Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation and gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 345, 196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.016

Wang, Y. H., Lv, Z. F., Zhong, Y., Liu, D. S., Chen, S. P., and Xie, Y. (2016). The internalization of Helicobacter pylori plays a role in the failure of H. pylori eradication. Helicobacter. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1111/hel.12324

Weeks, D. L., Eskandari, S., Scott, D. R., and Sachs, G. (2000). A H+-gated urea channel: the link between Helicobacter pylori urease and gastric colonization. Science 287, 482–485. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.482

Wilkinson, S. M., Uhl, J. R., Kline, B. C., and Cockerill, F. R. (1998). Assessment of invasion frequencies of cultured HEp-2 cells by clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori using an acridine orange assay. J. Clin. Pathol. 51, 127–133. doi: 10.1136/jcp.51.2.127

Worku, M. L., Sidebotham, R. L., Baron, J. H., Misiewicz, J. J., Logan, R. P., Keshavarz, T., et al. (1999). Motility of Helicobacter pylori in a viscous environment. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 1143–1150. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199910000-00012

Yamaoka, Y. (2008). Increasing evidence of the role of Helicobacter pylori SabA in the pathogenesis of gastroduodenal disease. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2, 174–181. doi: 10.3855/jidc.259

Yamaoka, Y., Ojo, O., Fujimoto, S., Odenbreit, S., Haas, R., Gutierrez, O., et al. (2006). Helicobacter pylori outer membrane proteins and gastroduodenal disease. Gut 55, 775–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.083014

Zhang, M. J., Meng, F. L., Ji, X. Y., He, L. H., and Zhang, J. Z. (2007). Adherence and invasion of mouse-adapted H pylori in different epithelial cell lines. World J. Gastroenterol. 13, 845–850. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i6.845

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, adhesion, invasion, chronic infection, mechanism

Citation: Huang Y, Wang Q-l, Cheng D-d, Xu W-t and Lu N-h (2016) Adhesion and Invasion of Gastric Mucosa Epithelial Cells by Helicobacter pylori. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 6:159. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00159

Received: 27 August 2016; Accepted: 04 November 2016;

Published: 22 November 2016.

Edited by:

D. Scott Merrell, Uniformed Services University, USAReviewed by:

Robert Maier, University of Georgia, USATraci Testerman, University of South Carolina, USA

Copyright © 2016 Huang, Wang, Cheng, Xu and Lu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nong-hua Lu, bHVub25naHVhQG5jdS5lZHUuY24=

Ying Huang

Ying Huang Qi-long Wang

Qi-long Wang Dan-dan Cheng

Dan-dan Cheng Wen-ting Xu

Wen-ting Xu Nong-hua Lu

Nong-hua Lu