95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem. , 15 May 2023

Sec. Organic Chemistry

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2023.1193080

This article is part of the Research Topic Metal-organic frames (MOF) - Based Materials and Their Applications View all 5 articles

Various pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidines were synthesized by the multicomponent reaction of aldehydes, malononitrile, and acidic C–H compounds such as barbituric acid through the tandem Knoevenagel–Michael cyclocondensation pathway in an environmentally friendly reactive medium in the presence of a recoverable nanocomposite. This nanocomposite includes Fe3O4 nanoparticles placed on an organometallic framework. The synthesized Fe3O4@iron-based metal–organic framework nanocomposite was characterized using scanning electron microscopy, energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, X-ray powder diffraction, a vibrating sample magnetometer, and thermogravimetric analysis.

Catalysis is one of the fundamental and beneficial processes in the chemical industries as they can reduce reagent-based wastes and enhance the selectivity of reactions in standard chemical transformations, hence minimizing potential by-products. Nanocatalysts are distinguished from their bulk counterparts due to their significantly smaller size with a unique shape which can significantly increase the surface area-to-volume ratio (Sajjadifar et al., 2019).

As a novel class of porous materials, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) have recently attracted a great deal of attention due to their well-defined structure and high surface area. Made of an inorganic metal cluster and polyfunctional organic linkers, MOFs have found diverse applications in optics, gas storage, sensors, gas separation, biomedicine, energy technologies, and catalysis (Zeraati et al., 2021).

Among various kinds of MOFs, iron-based MOFs are developed as heterogeneous catalysts for organic reactions due to their high dispersibility, structural efficiency, and abundant catalytically active sites (Bai et al., 2016; Rimoldi et al., 2017). Given the strong affinity of Fe3+ ions toward carboxylate groups of organic linkers, Fe-based MOFs have highly stable chemical structures, which can facilitate recycling and increase the chance of microwave-assisted synthesis. Moreover, the low toxicity, redox activity, and cost-effectiveness of Fe3+ further added to the popularity of MOF (Fe) (Doan et al., 2016; Nguyen et al., 2016).

Thanks to their reusability and facile separation, Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4 MNPs) have found wide applications in heterogeneous catalysis (Liu et al., 2015). Numerous functional materials have been studied with the Fe3O4 MNPs as a core. However, the easy oxidation by other substances and strong magnetic properties lead to aggregation and instability of Fe3O4 MNPs (Chen et al., 2019). Hence, some functional materials (e.g., MOF, carbon, polymer, PEG, and metal oxide) are loaded on the surface of the Fe3O4 MNPs to increase the stability and dispersion (Kim et al., 2013; Mirfakhraei et al., 2018; Moradi et al., 2018; Bakhteeva et al., 2019).

Chemists are interested in synthesizing compounds with a minimum of one pyran nucleus, as revealed by the current synthesis of various pyran derivatives such as pyranopyran, pyranochromene, and pyranopyrimidine (Raj et al., 2010; Solhy et al., 2010; Boominathan et al., 2011; Brahmachari and Banerjee, 2014).

Pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidines are important heterocyclic compounds with remarkable pharmaceutical and biological effects, such as antibacterial, antitumor, antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, anti-hypertension (Daneshvar et al., 2018), analgesics, and herbicidal (Amirnejat et al., 2020) features. The three-component condensation of aromatic aldehydes, barbituric acid, and malononitrile is among the simplest and most popular strategies in the synthesis of pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine dione-derived materials. So far, various catalysts have been introduced for the synthesis of pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine compounds, including (NH4)2HPO4, (Balalaie et al., 2008), SBA-Pr-SO3H (Ziarani et al., 2013), TMU-16-NH2 (Beheshti et al., 2018), KF (Elinson et al., 2014), ZnFe2O4 (Khazaei et al., 2015), the Fe3O4@SiO2@(CH2)3-Urea-SO3H/HCl magnetic nanoparticle (Zolfigol et al., 2016), Et3N (Azarifar et al., 2012), and ZnO nano powder (Maleki et al., 2016). Some studies have also reported the synthesis of pyrano[2,3–d]pyrimidines in the presence of ionic liquids (Karami et al., 2019), Bronsted acids (Mahmoudi et al., 2019), and magnetic catalysts (Sajjadifar and Gheisarzadeh, 2019). Most of these catalysts have had considerable drawbacks, including long reaction time, harsh reaction conditions, difficulties in the recovery of the catalyst, high-cost reagents, low yield, laborious workup, use of dangerous organic solvents, costly and moisture-sensitive reagents, and application of disposable dangerous catalysts. Therefore, research has mainly focused on the development of environmentally friendly and recyclable catalysts capable of effective synthesis of pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives.

Scheme 1 presents some examples of bioactive pyrimidine-annulated heterocyclic compounds with various medicinal properties.

In continuation of our attempts to the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds via MCR methodologies (Yahyazadehfar et al., 2019; Moghaddam-Manesh et al., 2020a; Moghaddam-Manesh et al., 2020b; Moghaddam-Manesh et al., 2020c; Yahyazadehfar et al., 2020), this research is focused on the synthesis of an eco-friendly and recyclable Fe3O4@iron-based metal–organic framework nanocomposite [Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC] using microwave irradiation to synthesize pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine scaffolds through three-component reactions of aryl aldehyde derivatives, malononitrile with barbituric acid. While the magnetic characteristics of the catalysts facilitate their quick and straightforward solid-phase separation from solution, further functionality can be introduced by magnetic nanoparticles through the synthesis of magnetic framework composites. This study reports a facile preparation of a magnetic metal–organic framework (Fe3O4@MOF (Fe)) as a new and cost-effective catalyst by microwave irradiation and use in the synthesis of pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine heterocycles.

Iron (III) nitrate, iron (II) chloride, ammonia, and 2,6-pyridinedicarboxylic acid were provided by Sigma-Aldrich. All the reagents and solvents were purchased from Merck chemical company and used without further purification.

Products were characterized in terms of their physical constants in comparison to authentic samples based on FT-IR spectroscopy. The purity of the substrates and reaction progress were determined by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on aluminum-backed plates coated with Merck Kieselgel 60 F254 silicagel. Melting points were measured using the Electrothermal 9,100 Apparatus in open capillary tubes. IR spectra were recorded on a JASCO FT-IR-4000 spectrophotometer device in the range of 400–4,000 cm−1. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were also attained using a Bruker AC (400 MHz for 1H NMR and 100 MHz and 13C NMR) and DMSO-d6 as solvents. A Philips analytical PC-APD X-ray diffractometer operating with Kα (α2, λ2=1.54439 Å) and graphite mono-chromatic Cu (α1, λ1=1.54056 Å) radiations was used for X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) to explore the structure of the product. Then, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy (KYKY & EM 3200) were applied to observe CB Fe-MOF@Fe3O4 NFC. Magnetization measurements were also carried out with a Lake Shore vibrating sample magnetometer (model 7407) under magnetic fields at room temperature.

First, 16 mmol (4.325 g) of iron (III) chloride was dissolved in a minimum amount of deionized water. In another beaker, 8 mmol (1.590 g) of iron (II) chloride was dissolved in a minimum volume of deionized water. The two solutions were mixed followed by the dropwise addition of 10 mL of 25% ammonia which immediately resulted in the formation of a large amount of black Fe3O4 precipitate. Stirring was continued for 20 min. Finally, the products were magnetically separated, rinsed with distilled water four times, and dried in an oven at 80°C.

To achieve a solution containing 13.365 mmol (2.233 g) of 2,6-pyridinedicarboxylic acid-linker in deionized water at 80°C, 4.455 mmol (1.8 g) iron nitrate was dissolved in the minimum amount of deionized water and stirred at 80°C. After overnight refrigeration, the resulting Fe-MOF precipitates were collected. To remove the raw materials, the resulting products were washed three times with boiling water and dried at 70°C for 12 h.

Dried Fe-MOF (0.6 g; 1.050 mmol) was dispersed in deionized water. Next, 0.137 g (0.35 mmol) of Fe3O4 was added, and the mixture was stirred at 80°C for 10 min to achieve a homogeneous solution. The final powder mixture was transferred to a glassy vial for microwave irradiation. Then, the glassy vial was immediately inserted in the microwave oven (145 W) and irradiated for 1 h. The raw materials were eliminated from the resulting products through washing with acetic acid. Ultimately, the dried powder was calcined at 170°C.

A mixture of aryl aldehyde derivatives (1 mmol), malononitrile (1 mmol), barbituric acid (1 mmol), Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC (25 w %), and 10 mL H2O/EtOH (1:1) was heated at 90°C for an appropriate time duration. After completion of the reaction (monitored by TLC (n-hexane/EtOAc, 70:30), the reaction mixture was cooled down, and 5 mL hot EtOH was added. Since the catalyst is insoluble in ethanol, the magnetic nanocatalyst was separated from the reaction vessel using an external magnet bar. After evaporation of EtOH, the expected products were formed and washed with hot H2O.

7-Amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-2,4-dioxo-1,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2H-pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carbonitrile (4a): Yield: 95%. M.p. = 226°C–229°C. IR (KBr, cm−1), 3,315, 3,187, 2,198, 1718, 1,637. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ = 4.23 (s, 1H, benzylic CH), 7.13–7.34 (m, 6H, 2H-NH2, 4H-Ar), 11.06 (s, 1H, NH), 12.07 (s, 1H, NH).

7-Amino-2,4-dioxo-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-1,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2H-pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carbonitrile (4b): Yield: 98%. M.p. = 249°C–252°C. IR (KBr, cm−1), 3,452, 3,288, 2,197, 1705, 1,663.1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ = 3.71 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.80 (s, 6H, OCH3), 4.42 (s, 1H, benzylic CH), 6.44 (s, 2H, H-Ar), 7.35 (s, 2H, NH2), 10.40 (s, 1H, NH), 11.10 (s, 1H, NH). 7-amino-5-(2-methoxyphenyl)-2,4-dioxo-1,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2H-pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carbonitrile (4c): Yield: 98%. M.p. = 209°C–212°C. IR (KBr, cm-1), 3,365, 3,304, 2,175, 1721, 1,674. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ = 3.71 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.46 (s, 1H, benzylic CH), 6.83–6.92 (m, 2H, H-Ar), 7.01 (brs, 2H, NH2), 7.04–7.19 (m, 2H, H-Ar), 10.96 (s, 1H, NH), 11.96 (s, 1H, NH). 7-amino-5-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-2,4-dioxo-1,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2H-pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carbonitrile (4d): Yield: 91%. M.p. = 171°C–172°C. IR (KBr, cm−1), 3,445, 2,201, 1726, 1,643. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ = 4.89 (S, 1H, benzylic CH), 6.66 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.05–7.40 (m, 4H, H-Ar), 9.73 (s, 1H, OH), 10.98 (s, 1H, NH), 11.02 (s, 1H, NH). 7-amino-5-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-2,4-dioxo-1,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2H-pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carbonitrile (4e): Yield: 93%. M.p. = 239°C–242°C. IR (KBr, cm−1), 3,390, 3,327, 2,195, 1717, 1,678. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ = 4.71 (s, 1H, benzylic CH), 7.18 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.32–7.51 (m, 3H, H-Ar), 11.06 (s, 1H, NH), 12.10 (s, 1H, NH).

7-Amino-5-(3-nitrophenyl)-2,4-dioxo-1,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2H-pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carbonitrile (4f): Yield: 97%. M.p. = 264°C–266°C. IR (KBr, cm−1), 3,417, 3,203, 2,192, 1711, 1,659. 1HNMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 4.47 (s, 1H, benzylic CH), 7.30 (br s, 2H, NH2), 7.61 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, H-Ar), 7.75 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H-Ar), 8.0.6 (t, J = 2 Hz, 1H), 8.08–8.12 (m, 2H, H-Ar), 11.12 (s, 2H, NH), 12.18 (s, 1H, NH).

7-Amino-5-(2-nitrophenyl)-2,4-dioxo-1,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2H-pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carbonitrile (4g): Yield: 94%. M.p. = 229°C–233°C. IR (KBr, cm-1), 3,468, 3,365, 2,198, 1705, 1,659. 1HNMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 5.00 (s, 1H, benzylic CH), 7.27 (brs, 2H, NH2), 7.44–7.82 (m, 4H, H-Ar), 11.04 (s, 1H, NH), 12.12 (s, 1H, NH).

7-Amino-5-(4-nitrophenyl)-2,4-dioxo-1,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2H-pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carbonitrile (4h): Yield: 97%. M.p. = 240°C–243°C. IR (KBr, cm−1): 3,373, 3,186, 2,198, 1720, 1,637. 1HNMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 4.40 (s, 1H, benzylic CH), 7.24 (brs, 2H, NH2), 7.51 (d, J = 8.25 Hz, 2H, H-Ar), 8.14 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H, H-Ar), 11.09 (s, 1H, NH), 12.15 (s, 1H, NH). 7-amino-2,4-dioxo-5-(p-tolyl)-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carbonitrile (4i): Yield: 96%. M.p. = 226°C–228°C. IR (KBr, cm−1): 3,391, 3,321, 2,199, 1716, 1,677. 1HNMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 2.23 (s, 3H, CH3), 4.14 (s, 1H, benzylic CH), 7.06 (brs, 6H, 2H-NH2, 4H-Ar), 11.03 (s, 1H, NH), 12.02 (s, 1H, NH). 7-amino-2,4-dioxo-5-(m-tolyl)-1,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2H-pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carbonitrile (4j): Yield: 91%. M.p. = 230°C–233°C. IR (KBr, cm−1): 3,415, 3,319, 2,194, 1711, 1,661. 1HNMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 2.25 (s, 3H, CH3), 4.15 (s, 1H, benzylic CH), 6.97–7.15 (m, 6H, 2H-NH2, 4H-Ar), 11.03 (s, 1H, NH), 12.04 (brs, 1H, NH).

7-Amino-2,4-dioxo-5-phenyl-1,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2H-pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carbonitrile (4k): Yield: 95%. M.p. = 206°C–208°C. IR (KBr, cm-1): 3,385, 3,335, 2,194, 1714, 1,677. 1HNMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 4.20 (s, 1H, benzylic CH), 7.08–7.25 (m, 7H, 2H-NH2, 5H-Ar), 11.04 (s, 1H, NH), 12.05 (brs, 1H, NH).

7-Amino-5-(4-bromophenyl)-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2,4-dioxo-1H-pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carbonitrile (4l): Yield 97%, m.p = 228°C–232°C. IR (KBr, cm−1): 3,207, 3,153, 3,091, 2,195, 1,693, 1,678. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ: 4.21 (s, 1H, CH), 7.16 (d, 4H, J = 8.25, 2H-Ar, 2H-NH2), 7.45 (d, 2H, J = 7.75, H-Ar), 11.04 (s, 1H, NH), 12.06 (brs, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (75 Hz, DMSO-d6): δ = 162.9, 158.0, 152.8, 149.9, 132.7, 132.6, 131.5, 130.1, 120.2, 119.5, 88.4, 58.7, 35.7.

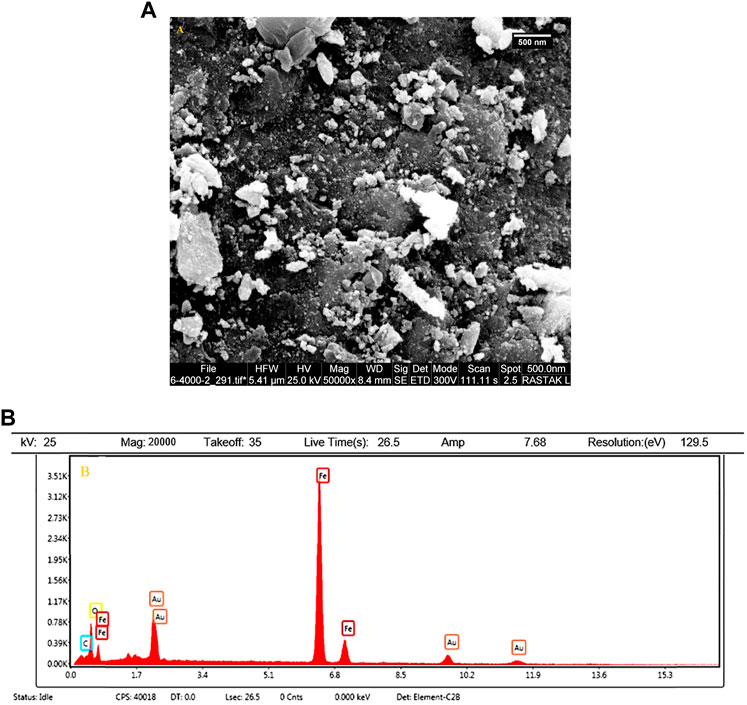

The size and morphology of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC were characterized by SEM (Figure 1). The SEM image represents the spherical morphology of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC. The as-synthesized Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC showed uniform size and shape with relative mono-dispersion. The particles have a narrow size distribution with less than 10 nm.

Moreover, the purity of the synthesized Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NCs was studied after calcination EDX (Figure 2). The EDX results revealed that the prepared Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC consisted of carbon, oxygen, and iron (52.33, 40.05, and 7.62 w/w%, respectively) (inset of Figure 2) with no impurity, indicating that the composite sample is composed of Fe3O4 and MOF (Fe).

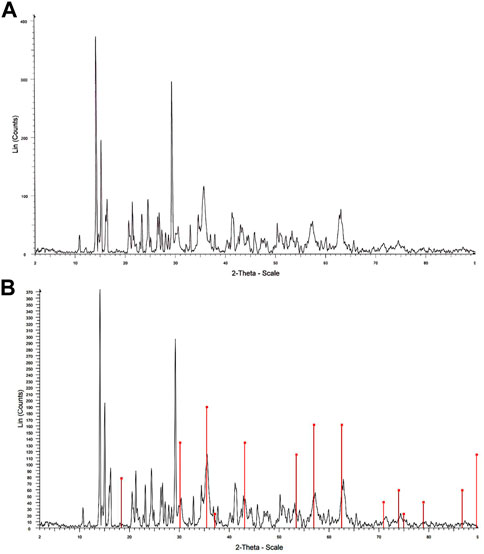

The XRD patterns of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC and Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC simulated on phase (Fe3O4) are, respectively, shown in Figures 3A, B. In both XRD patterns, the peaks are recorded in the 2θ range of 10°–70°. The nanocomposite showed six characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ = 30.56°, 35.83°, 43.08°, 53.30°, 57.47°, and 62.74°, which can be indexed to the (220), (311), (400), (422), (511), and (440) crystalline planes of the cubic inverse spinel structure of Fe3O4 (JCPDS no. 88–0315). Therefore, the crystalline structure of Fe3O4 MNPs was not notably damaged by MOF (Fe) coating (Ali et al., 2019). Moreover, Figure 3B shows the XRD patterns of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC simulated on phase (Fe3O4). According to this figure, the XRD pattern showed multiple diffraction peaks that were assigned to MOF (Fe) as a poly-crystalline structure. As an important result, the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC was successfully simulated on phase (Fe3O4). Using the Debye–Scherrer equation, D=Kλ/βcosθ, the average crystallite size (D) was estimated by measuring the width of the Bragg reflections, where λ stands for the wavelength of X-ray (1.54056 Å for Cu lamp), K represents the Scherrer constant (0.9), θ shows half of the Bragg diffraction angle, and β denotes half of the width of the maximum intensity diffraction peak. The average crystallite size of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC was 10 nm, indicating the excellent dispersity and crystal structures of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC with no agglomeration.

FIGURE 3. XRD pattern of the (A) Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC and (B) Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC simulated on phase (Fe3O4).

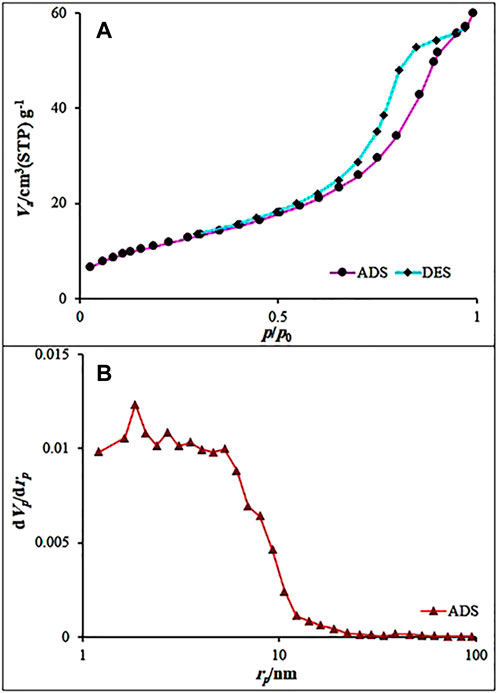

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms were recorded at 77 K. The Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC was analyzed using the BET and 2D-NLDFT methods (Figure 4). A slow absorption was observed in the P/P0 range of 0.0–0.2, followed by a rapid increase in the P/P0 range of 0.2–1.0. These results suggest IV isotherm with a type H2 hysteresis loop for the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC samples, which is a typical feature of materials with uniform mesoporous and inkbottle shape pores. The BJH pore volume (VBJH) and the BET surface area (SBET) of the samples were 0.093 cm3/g and 113.93 m2/g, respectively. These results revealed the wide pore openings and a high porosity of Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC, making it one of the best catalysts in the organic transformations.

FIGURE 4. (A) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC and (B) BJH results obtained for the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC.

The magnetic hysteresis loop of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC in the presence of magnetic field was measured using a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM). Figure 5 shows the hysteresis loops of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC at room temperature. This figure proved the super-paramagnetic properties of Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC. The Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC exhibited small remanent magnetization (Mr, 1.98 emu/g) and coercivity (Hc, 0.9 Oe), indicating its suitable magnetic behavior and saturation magnetization (Ms, 21.2 emu/g). The Ms value of 21.2 emu/g suffices for magnetic separation by a conventional magnet. Therefore, the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC can be used as a recoverable catalyst in the organic transformations.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and DSC were utilized to assess the thermal behavior of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC (Figures 6A, B). Therefore, TGA was applied on an STA-1500 thermoanalyzer under the inert condition in the scope 30°C–350°C and at a heating rate of 10°C min−1. Thermal analysis of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC as a final product is presented in Table 1. The results reveal appropriate thermal stability without weight loss. A partial diminish in the weight (1%) was recorded at a temperature from 50°C to 100°C. This is due to the removal of trapped solvents such as the water in the pores and on the MOF (Fe) skeleton. Proportionate to the temperature ascent from 100°C to 235°C, a 7.71% reduction in weight was observed. That probably corresponds to decomposing linker on the skeleton. The weight loss of dissociation of coordinated water (12.98%) for the catalyst was estimated in the range of 235°C–347°C. The main weight loss of 79.22% of the catalyst is observed in the range of 347°C–399°C, which is connected with the final decomposition. Therefore, obtained data show high thermal stability in elevated temperatures.

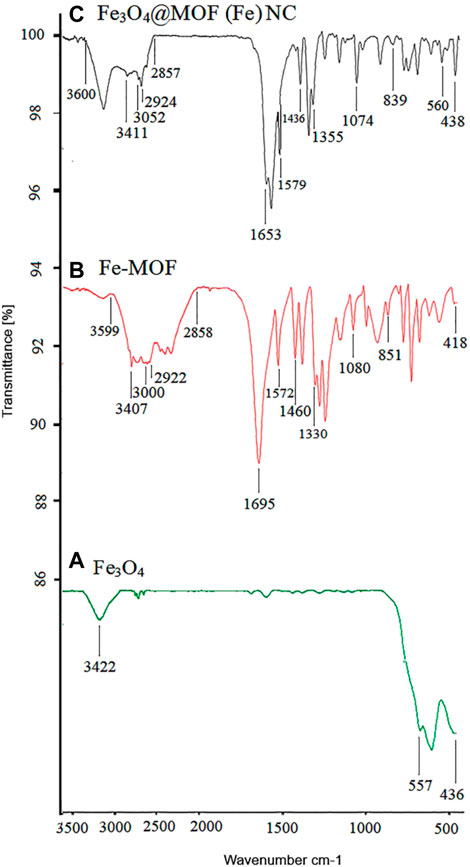

The FT-IR spectra of Fe3O4, Fe-MOF, and the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC are shown in Figure 7. The presence of nanoparticles in the complex structure of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC is confirmed by emergence of some peaks at 436, 557, and 438, 560 cm−1 corresponding to Fe–O vibration in Fe3O4 and the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC, respectively. The stretching frequencies of hydroxyl groups on the surface of the nanoparticles appeared as a peak at 3,422 cm-1 whose broadening and low intensity can be due to intermolecular hydrogen bonding and the chelation of iron atom with the oxygen atom of Fe3O4, respectively. Moreover, two bands at 3,052 and 2,924 cm−1 can be attributed to C–H stretching, while the two peaks at 1,436 and 1,579 cm−1 are related to C–C and C–N bonds of pyridine, respectively. The band at 1,355 cm−1 can be also ascribed to the NO−3 counter ion. The bands at 1,074 and 839 cm−1, respectively, confirm the presence of C–N groups and Fe–N bond, whereas the band at 438 cm−1 indicates the presence of an Fe–O bond. Vibration frequencies indicate the presence of Fe-MOF in the structure of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC. The absorption of acidic OH in the nano-organocatalyst at 2,857 to 3,600 cm−1 is related to the acidic OH of the ligand, which is seen in the region of 2,858–3,599 cm−1 in Fe-MOF. The adsorption of the CO ligand in Fe-MOF appeared at 1,695 cm−1, while this adsorption in nano-organocatalyst emerged at 1,653 cm−1. Other absorptions at 1,074, 839, and 438 cm-1 in nano-organocatalyst are, respectively, equivalent to the absorptions at 1,080 and 851 cm−1 in Fe-MOF and absorption of 436 cm−1 in nanoparticles, indicating the presence of magnetite nanoparticles on the structure of Fe-MOF and formation of the complex Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC.

FIGURE 7. IR (KBr, υ/cm-1) curve of (A) Fe3O4, (B) synthesized Fe-MOF, and (C) the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC.

The Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NCs were designed, synthesized, and characterized before their employment in the one-pot synthesis of pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives using a variety of aldehydes, malononitrile, and barbituric acid (Scheme 2).

Initially, the model reaction had to be formed by selecting the 4-chlorobenzaldehyde, malononitrile, and barbituric acid mixture (containing 1 mmol of each), followed by meticulous investigation of the impact of different factors, including the catalyst amount, solvent, and temperature to obtain the most desirable reaction conditions.

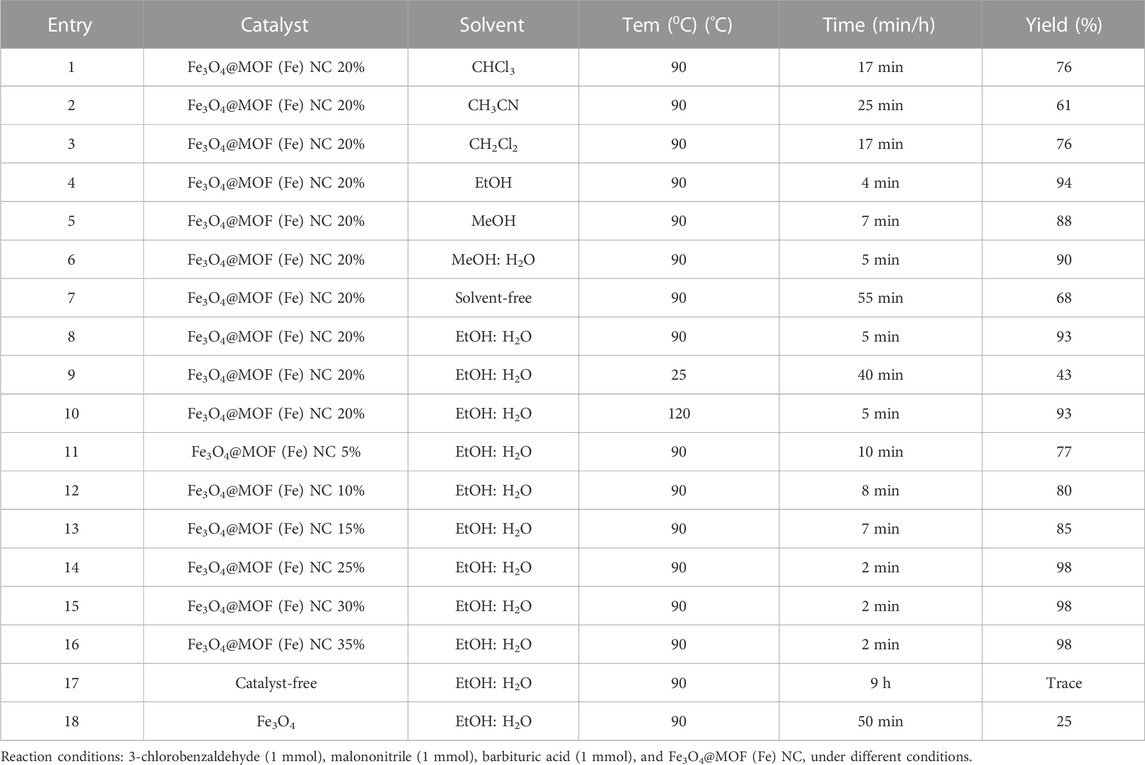

Accordingly, the impacts of different solvents, temperatures, and catalyst amounts were examined on the model reaction of 4-chlorobenzaldehyde, malononitrile, and barbituric acid to optimize the reaction conditions and evaluate the primary influential parameters on the catalyzed pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine reactions. Lower yields and longer reaction times were reported in the absence of the solvent but the presence of 20 w% catalyst at 90°C, suggesting the effects of the solvent on the reaction advancement. The EtOH: H2O ratio of 1:1 represents the most effective solvent for this reaction, as it accelerated the reaction more than other solvents and solvent-free conditions (Table 2). The use of ethanol: water mixture as a green solvent can offer several advantages including the absence of carcinogenic complications, eco-friendliness, relatively lower operating costs, and clean reaction conditions. The impact of the organic–aqueous EtOH interface and stabilization of the reaction intermediate can be described by the effective establishment of hydrogen bonding. A solvent with considerable polarity and faster heat transfer can offer optimum conditions for intermediate generation.

TABLE 2. Optimization of the reaction conditions for the synthesis of pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives using the CB Fe-MOF@Fe3O4 NFC.

The effect of reaction temperature was also examined to improve the yields and interaction conditions (Table 2, entries 8, 9). A temperature decline from 90°C to 25°C enhanced the reaction time while decreasing the reaction rate and the product yield (Table 2, entry 9). On the other hand, an increment in the reaction temperature from 90 to 120°C led to no further improvements in the yield or decrease in the reaction time at different temperatures (Table 2, entry10).

The effect of catalyst loading was examined after optimization of the effects of solvent and temperature. In the absence of the catalyst, only a trace of product was observed at 90°C within 9 h (Table 2, entry 17), indicating the essential role of the catalyst in this transformation. A decrease in the catalyst loading from 20 w% to 5 w% reduced the yield of the relative product (Table 2, entries 8, 11–13). In the catalyst loading of 20–35 w%, the catalyst content of 25% led to the highest efficiency, below which no effects were detected on the yield or reaction improvement (Table 2, entries 8, 14–16). Thus, 25 w% of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC as the nano-organocatalyst in H2O/EtOH (1:1) at 90°C resulted in the most desirable reaction conditions (Table 2, entry 14).

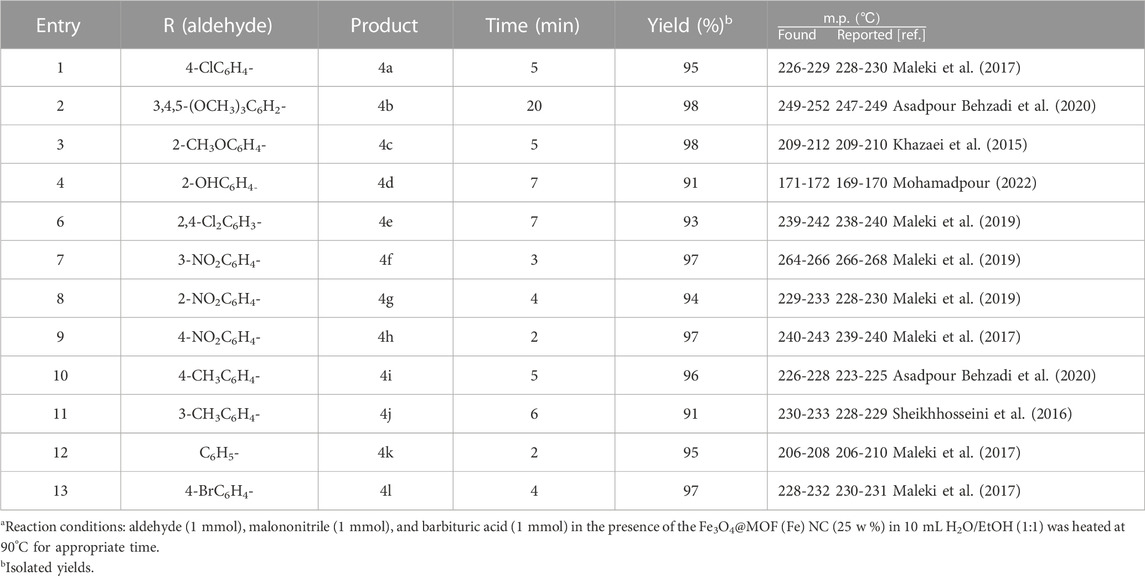

The effect of the reaction scope on the model reaction was investigated following the optimization of the reaction conditions. Based on the findings (Table 3), the electronic impact of various substitutions on the aromatic aldehydes had no effects on the product yield. Activation of the reactions was totally similar in both (electron-donating/withdrawing) substitutions at the ortho/meta/para positions on the aromatic aldehyde (Table 3).

TABLE 3. Preparation of pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine using the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC as the nano-organocatalyst.

To justify this mechanism, Knoevenagel condensation and then cyclization resulting in xanthene derivatives are ascribed to the special role of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC as a catalyst (Scheme 3). As the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC is a Lewis acidic catalyst, benzaldehyde was first partially bound with the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC for the carbonyl carbon activation, after which C=C bonds were formed with the active methylene group of malononitrile 2 for the formation of intermediate 2-benzylidenemalononitrile (I). The next step involved the formation of C–C bonds of intermediates (I) which had activated barbituric acid for the intermediate (II) formation. Then, the intramolecular cyclization of intermediates (II) gave intermediates (III), followed by the NH group protonation which yielded the eventual product (4) and regenerated the catalyst.

Recovery and recyclability of the catalyst can significantly contribute to different industries, commercial areas, and green chemistry. The most important advantages of the reported magnetic nanocomposite are its reusability and recovery due to its magnetic properties. The reusability of the prepared catalyst was checked in a model reaction for the pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivative preparation under optimized conditions for at least three runs. For this purpose and reaction completion, the nanocatalyst was simply separated by an external magnetic field followed by washing with ethanol, drying in an oven at 40°C. After three runs, no considerable decrease was detected in the catalytic activity of the samples (Figure 8).

The SEM image and EDX elemental analysis of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC after the catalytic procedure are shown in Figures 9A, B. Based on Figure 9A, the particle size distribution of samples is uniform, and there is no evidence of agglomeration in the structure. As an important result, the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC is stable in terms of morphology and surface. Also, the EDX elemental analysis confirmed the presence of related elements (Fe, O, and C) of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC in the final product after the catalytic procedure (Figure 9B).

FIGURE 9. (A) SEM image and (B) EDX analysis of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC after the catalytic procedure.

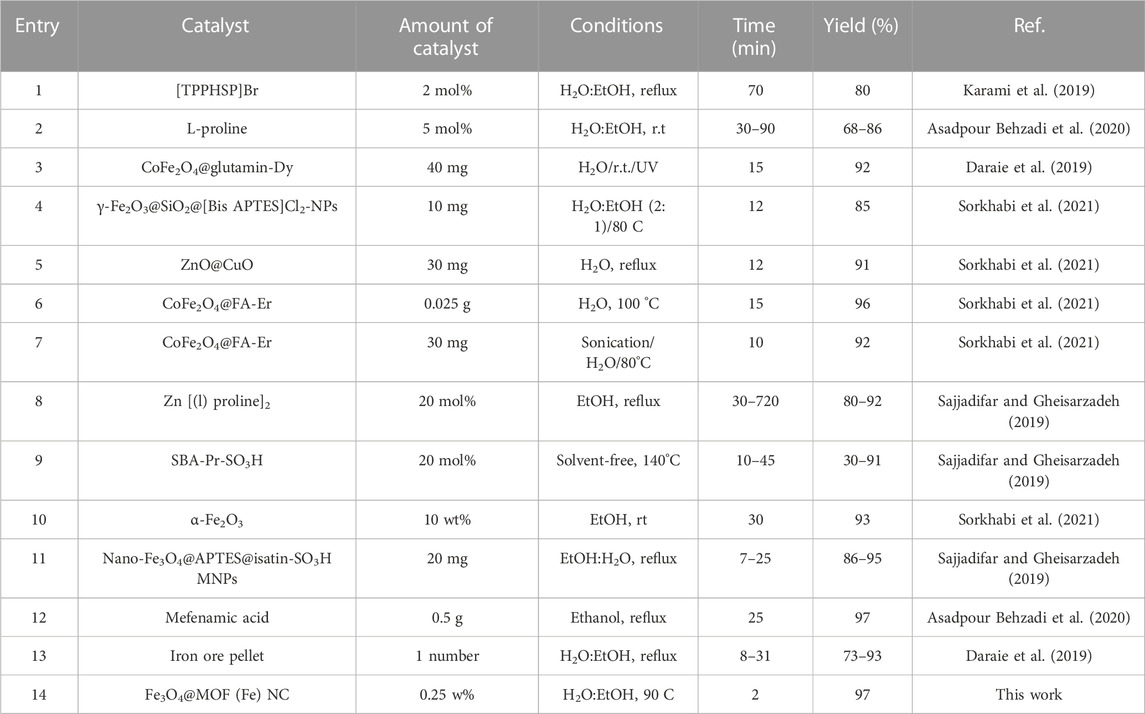

Table 4 compares the catalytic potential of several previously reported catalytic reactions with the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC for the synthesis of pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine scaffolds. According to the current paper, the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC has extraordinary potential as an economic and easily accessible catalyst to mildly and conveniently synthesize these biologically active heterocyclic compounds at a considerable yield and short reaction time. The results revealed that the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC is an excellent nano-organocatalyst in terms of both reaction time and product yield.

TABLE 4. Comparison of the synthesis of pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidines in the presence of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC with other catalysts reported in the literature.

In summary, a novel and efficient magnetic Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC was synthesized as a nano-organocatalyst by microwave irradiation. The nanocatalyst was fully characterized by various techniques, including FE-SEM, EDX, XRD, TGA, BET, and VSM. The catalytic activity of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC as a solid Lewis acid magnetic nanocatalyst was approved in the preparation of pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine scaffolds through the tandem Knoevenagel–Michael cyclocondensation reactions in aqueous/aqueous ethanol media at 90°C. This nanocatalyst can be easily recovered by an appropriate external magnet and reused at least three times with no considerable decline in its catalytic effects. High catalytic activity and easy magnetic separation from the reaction medium are two significant factors in the performance of the Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC in the organic transformations. This novel protocol offers advantages such as short reaction times, eco-friendly catalyst, recyclability, no need for column chromatography, easy workup, and progress of the reaction under green conditions.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

GH: investigation and writing—original manuscript. ES: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing—review and editing. SA and MY: formal analysis, methodology, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing—review and editing. All authors read and agreed to publish this article. All authors listed made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors appreciate the Islamic Azad University (Kerman Branch) for supporting this research.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ali, S., Khan, S. A., Yamani, Z. H., Qamar, M. T., Morsy, M. A., and Sarfraz, S. (2019). Shape-and size-controlled superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles using various reducing agents and their relaxometric properties by Xigo acorn area. Appl. Nanosci. 9, 479–489. doi:10.1007/s13204-018-0907-5

Amirnejat, S., Nosrati, A., Peymanfar, R., and Javanshir, S. (2020). Synthesis and antibacterial study of 2-amino-4 H-pyrans and pyrans annulated heterocycles catalyzed by sulfated polysaccharide-coated BaFe12O19 nanoparticles. Res. Chem. Intermed. 46, 3683–3701. doi:10.1007/s11164-020-04168-x

Asadpour Behzadi, S., Sheikhhosseini, E., Ali Ahmadi, S., Ghazanfari, D., and Akhgar, M. (2020). Mefenamic acid as environmentally catalyst for threecomponent synthesis of dihydropyrano [2, 3-c] chromene and pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidine derivatives. J. Appl. Chem. Res. 14, 63–73.

Azarifar, D., Nejat-Yami, R., Sameri, F., and Akrami, Z. (2012). Ultrasonic-promoted one-pot synthesis of 4H-chromenes, pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidines, and 4H-pyrano [2, 3-c] pyrazoles. Lett. Org. Chem. 9, 435–439. doi:10.2174/157017812801322435

Bai, Y., Dou, Y., Xie, L. H., Rutledge, W., Li, J. R., and Zhou, H. C. (2016). Zr-Based metal–organic frameworks: Design, synthesis, structure, and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 2327–2367. doi:10.1039/C5CS00837A

Bakhteeva, I. A., Medvedeva, I. V., Filinkova, M. S., Byzov, I. V., Zhakov, S. V., Uimin, M. A., et al. (2019). Magnetic sedimentation of nonmagnetic TiO2 nanoparticles in water by heteroaggregation with Fe-based nanoparticles. Sep. Purif. Technol. 218, 156–163. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2019.02.043

Balalaie, S., Abdolmohammadi, S., Bijanzadeh, H. R., and Amani, A. M. (2008). Diammonium hydrogen phosphate as a versatile and efficient catalyst for the one-pot synthesis of pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidinone derivatives in aqueous media. Mol. Divers. 12, 85–91. doi:10.1007/s11030-008-9079-7

Beheshti, S., Safarifard, V., and Morsali, A. (2018). Isoreticular interpenetrated pillared-layer microporous metal-organic framework as a highly effective catalyst for three-component synthesis of pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidines. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 94, 80–84. doi:10.1016/j.inoche.2018.06.002

Boominathan, M., Nagaraj, M., Muthusubramanian, S., and Krishnakumar, R. V. (2011). Efficient atom economical one-pot multicomponent synthesis of densely functionalized 4H-chromene derivatives. Tetrahedron 67, 6057–6064. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2011.06.021

Brahmachari, G., and Banerjee, B. (2014). Facile and one-pot access to diverse and densely functionalized 2-amino-3-cyano-4 H-pyrans and pyran-annulated heterocyclic scaffolds via an eco-friendly multicomponent reaction at room temperature using urea as a novel organo-catalyst. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2, 411–422. doi:10.1021/sc400312n

Chen, W., Zhang, J., and Chen, F. (2019). Glycothermal synthesis of fluorinated Fe3O4 microspheres with distinct peroxidase-like activity. Adv. Powder Technol. 30, 999–1005. doi:10.1016/j.apt.2019.02.014

Daneshvar, N., Nasiri, M., Shirzad, M., Langarudi, M. S. N., Shirini, F., and Tajik, H. (2018). The introduction of two new imidazole-based bis-dicationic Brönsted acidic ionic liquids and comparison of their catalytic activity in the synthesis of barbituric acid derivatives. New J. Chem. 42, 9744–9756. doi:10.1039/C8NJ01179F

Daraie, M., Heravi, M. M., and Tamoradi, T. (2019). Investigation of photocatalytic activity of anchored dysprosium and praseodymium complexes on CoFe2O4 in synthesis of pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidine derivatives. ChemistrySelect 4, 10742–10747. doi:10.1002/slct.201903138

Doan, T. L., Dao, T. Q., Tran, H. N., Tran, P. H., and Le, T. N. (2016). An efficient combination of Zr-MOF and microwave irradiation in catalytic Lewis acid Friedel–Crafts benzoylation. Dalton Trans. 45, 7875–7880. doi:10.1039/C6DT00827E

Elinson, M. N., Ryzhkov, F. V., Merkulova, V. M., Ilovaisky, A. I., and Nikishin, G. I. (2014). Solvent-free multicomponent assembling of aldehydes, N, N′-dialkyl barbiturates and malononitrile: Fast and efficient approach to pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidines. Heterocycl. Commun. 20, 281–284. doi:10.1515/hc-2014-0114

Karami, S., Momeni, A. R., and Albadi, J. (2019). Preparation and application of triphenyl (propyl-3-hydrogen sulfate) phosphonium bromide as new efficient ionic liquid catalyst for synthesis of 5-arylidene barbituric acids and pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidine derivatives. Res. Chem. Intermed. 45, 3395–3408. doi:10.1007/s11164-019-03798-0

Khazaei, A., Ranjbaran, A., Abbasi, F., Khazaei, M., and Moosavi-Zare, A. R. (2015). Synthesis, characterization and application of ZnFe 2 O 4 nanoparticles as a heterogeneous ditopic catalyst for the synthesis of pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidines. RSC Adv. 5, 13643–13647. doi:10.1039/C4RA16664G

Kim, Y. S., Lee, S. M., Govindaiah, P., Lee, S. J., Lee, S. H., Kim, J. H., et al. (2013). Multifunctional Fe3O4 nanoparticles-embedded poly (styrene)/poly (thiophene) core/shell composite particles. Synth. Mater. 175, 56–61. doi:10.1016/j.synthmet.2013.04.019

Liu, F., Niu, F., Peng, N., Su, Y., and Yang, Y. (2015). Synthesis, characterization, and application of Fe3O4@SiO2–NH2 nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 5, 18128–18136. doi:10.1039/C4RA15968C

Mahmoudi, Z., Ghasemzadeh, M. A., and Kabiri-Fard, H. (2019). Fabrication of UiO-66 nanocages confined bronsted ionic liquids as an efficient catalyst for the synthesis of dihydropyrazolo [4′, 3’: 5, 6] pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidines. J. Mol. Struct. 1194, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.05.079

Maleki, A., Jafari, A. A., and Yousefi, S. (2017). Green cellulose-based nanocomposite catalyst: Design and facile performance in aqueous synthesis of pyranopyrimidines and pyrazolopyranopyrimidines. Carbohydr. Polym. 175, 409–416. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.08.019

Maleki, A., Niksefat, M., Rahimi, J., and Taheri-Ledari, R. (2019). Multicomponent synthesis of pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidine derivatives via a direct one-pot strategy executed by novel designed copperated Fe3O4@ polyvinyl alcohol magnetic nanoparticles. Mat. Today Chem. 13, 110–120. doi:10.1016/j.mtchem.2019.05.001

Maleki, N., Shakarami, Z., Jamshidian, S., and Nazari, M. (2016). Clean synthesis of pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidines using ZnO nano-powders. Acta Chem. iasi. 24, 20–28. doi:10.1515/achi-2016-0002

Mirfakhraei, S., Hekmati, M., Eshbala, F. H., and Veisi, H. (2018). Fe3O4/PEG-SO3 H as a heterogeneous and magnetically-recyclable nanocatalyst for the oxidation of sulfides to sulfones or sulfoxides. New J. Chem. 42, 1757–1761. doi:10.1039/C7NJ02513K

Moghaddam-Manesh, M., Ghazanfari, D., Sheikhhosseini, E., and Akhgar, M. (2020a). Synthesis of bioactive magnetic nanoparticles spiro [indoline-3, 4′-[1, 3] dithiine]@ Ni(NO3)2 supported on Fe3O4@SiO2@CPS as reusable nanocatalyst for the synthesis of functionalized 3, 4-dihydro-2H-pyran. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, e5543. doi:10.1002/aoc.5543

Moghaddam-Manesh, M., Ghazanfari, D., Sheikhhosseini, E., and Akhgar, M. (2020b). Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial evaluation of novel 6'-Amino-spiro [indeno [1, 2-b] quinoxaline [1, 3] dithiine]-5'-carbonitrile derivatives. Acta Chim. Slov. 67, 276–282. doi:10.17344/acsi.2019.5437

Moghaddam-Manesh, M., Sheikhhosseini, E., Ghazanfari, D., and Akhgar, M. (2020c). Synthesis of novel 2-oxospiro [indoline-3, 4′-[1, 3] dithiine]-5′-carbonitrile derivatives by new spiro [indoline-3, 4′-[1, 3] dithiine]@ Cu (NO3)2 supported on Fe3O4@gly@CE MNPs as efficient catalyst and evaluation of biological activity. Bioorg. Chem. 98, 103751. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103751

Mohamadpour, F. (2022). Supramolecular β-cyclodextrin as a biodegradable and reusable catalyst promoted environmentally friendly synthesis of pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidine scaffolds via tandem knoevenagel–michael–cyclocondensation reaction in aqueous media. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 42, 2805–2814. doi:10.1080/10406638.2020.1852274

Moradi, S., Zolfigol, M. A., Zarei, M., Alonso, D. A., Khoshnood, A., and Tajally, A. (2018). An efficient catalytic method for the synthesis of pyrido [2, 3-d] pyrimidines as biologically drug candidates by using novel magnetic nanoparticles as a reusable catalyst. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 32, e4043. doi:10.1002/aoc.4043

Nguyen, V. T., Ngo, H. Q., Le, D. T., Truong, T., and Phan, N. T. (2016). Iron-catalyzed domino sequences: One-pot oxidative synthesis of quinazolinones using metal–organic framework Fe3O(BPDC)3 as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 284, 778–785. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2015.09.036

Raj, T., Bhatia, R. K., kapur, A., and Sharma, M. (2010). Cytotoxic activity of 3-(5-phenyl-3 H -[1,2,4]dithiazol-3-yl)chromen-4-ones and 4-oxo-4 H -chromene-3-carbothioic acid N -phenylamides. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 45, 790–794. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.11.001

Rimoldi, M., Howarth, A. J., DeStefano, M. R., Lin, L., Goswami, S., Li, P., et al. (2017). Catalytic zirconium/hafnium-based metal–organic frameworks. ACS Catal. 7, 997–1014. doi:10.1021/acscatal.6b02923

Sajjadifar, S., and Gheisarzadeh, Z. (2019). Isatin-SO3H coated on amino propyl modified magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4@ APTES@ isatin-SO3H) as a recyclable magnetic nanoparticle for the simple and rapid synthesis of pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidines derivatives. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 33, e4602. doi:10.1002/aoc.4602

Sajjadifar, S., Zolfigol, M. A., and Tami, F. (2019). Application of 1-methyl imidazole-based ionic liquid-stabilized silica-coated Fe3O4 as a novel modified magnetic nanocatalyst for the synthesis of pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidines. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 66, 307–315. doi:10.1002/jccs.201800171

Sheikhhosseini, E., Sattaei, M. T., Faryabi, M., Rafiepour, A., and Soltaninejad, S. (2016). Iron ore pellet, a natural and reusable catalyst for synthesis of pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidine and dihydropyrano [c] chromene derivatives in aqueous media. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 35, 43–50.

Solhy, A., Elmakssoudi, A., Tahir, R., Karkouri, M., Larzek, M., Bousmina, M., et al. (2010). Clean chemical synthesis of 2-amino-chromenes in water catalyzed by nanostructured diphosphate Na2CaP2O7. Green Chem. 12, 2261–2267. doi:10.1039/C0GC00387E

Sorkhabi, S., Mozafari, R., and Ghadermazi, M. (2021). New advances in catalytic performance of erbium-folic acid-coated CoFe2O4 complexes for green one-pot three-component synthesis of pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidinone and dihydropyrano [3, 2-c] chromenes compounds in water. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 35, e6225. doi:10.1002/aoc.6225

Yahyazadehfar, M., Ahmadi, S. A., Sheikhhosseini, E., and Ghazanfari, D. (2020). High-yielding strategy for microwave-assisted synthesis of Cr2O3 nanocatalyst. J. Mat. Sci. Mat. Electron. 31, 11618–11623. doi:10.1007/s10854-020-03710-2

Yahyazadehfar, M., Sheikhhosseini, E., Ahmadi, S. A., and Ghazanfari, D. (2019). Microwave-associate synthesis of Co3O4 nanoparticles as an effcient nanocatalyst for the synthesis of arylidene barbituric and Meldrum's acid derivatives in green media. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 33, e5100. doi:10.1002/aoc.5100

Zeraati, M., Mohammadi, A., Vafaei, S., Chauhan, N. P. S., and Sargazi, G. (2021). Taguchi-assisted optimization technique and density functional theory for green synthesis of a novel Cu-MOF derived from caffeic acid and its anticancerious activities. Front. Chem. 9, 722990. doi:10.3389/fchem.2021.722990

Ziarani, G. M., Faramarzi, S., Asadi, S., Badiei, A., Bazl, R., and Amanlou, M. (2013). Three-component synthesis of pyrano [2, 3-d]-pyrimidine dione derivatives facilitated by sulfonic acid nanoporous silica (SBA-Pr-SO3H) and their docking and urease inhibitory activity. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 21, 3–13. doi:10.1186/2008-2231-21-3

Zolfigol, M. A., Ayazi-Nasrabadi, R., and Baghery, S. (2016). The first urea-based ionic liquid-stabilized magnetic nanoparticles: An efficient catalyst for the synthesis of bis (indolyl) methanes and pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidinone derivatives. Appl. Organometal. Chem. 30, 273–281. doi:10.1002/aoc.3428

Keywords: magnetic nanocatalyst, metal–organic frameworks, pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidines, 2,6-pyridinedicarboxylic acid, green chemistry, microwave irradiation

Citation: Hootifard G, Sheikhhosseini E, Ahmadi SA and Yahyazadehfar M (2023) Fe3O4@iron-based metal–organic framework nanocomposite [Fe3O4@MOF (Fe) NC] as a recyclable magnetic nano-organocatalyst for the environment-friendly synthesis of pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives. Front. Chem. 11:1193080. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2023.1193080

Received: 24 March 2023; Accepted: 02 May 2023;

Published: 15 May 2023.

Edited by:

Yong-Sheng Wei, Kyoto University, JapanReviewed by:

Yu Wang, Northwestern Polytechnical University, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Hootifard, Sheikhhosseini, Ahmadi and Yahyazadehfar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Enayatollah Sheikhhosseini, c2hlaWtoaG9zc2VpbnlAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.