94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem. , 01 September 2022

Sec. Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Chemistry

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2022.990734

This article is part of the Research Topic Bioactive Natural Products for Health: Isolation, Structural Elucidation, Biological Evaluation, Structure-activity Relationship, and Mechanism View all 10 articles

A chemical investigation on the kiwi endophytic fungus Bipolaris sp. Resulted in the isolation of eight new terpenoids (1–8) and five known analogues (9–13). Compounds 1–5 are novel sativene sesquiterpenoids containing three additional skeletal carbons, while compounds 4 and 5 are rare dimers. Compounds 6–8 and 13 are sesterterpenoids that have been identified from this species for the first time. Compounds 4 and 5 showed antibacterial activity against kiwifruit canker pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. Actinidiae (Psa) with MIC values of 32 and 64 μg/ml, respectively.

Kiwifruit is an important global food source produced at a scale of 4 million tons per year (Richardson et al., 2018; Dolly et al., 2021). However, the kiwi plant (Actinidia chinensis Planch.) is severely attacked by canker caused by the pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas syringae pv. Actinidiae (Psa) (Renzi et al., 2012; Scortichini et al., 2012). As one of the major countries in the kiwifruit industry, China’s kiwifruit has also suffered extensive damage from canker disease, causing huge economic losses (Serizawa et al., 1989; McCann et al., 2017; Vanneste, 2017). Traditional Psa inhibitors such as copper-based preparations and streptomycin are not friendly to the environment and even cause drug resistance (Bardas et al., 2010; Colombi et al., 2017; Scortichini, 2018; Wicaksono et al., 2018). Therefore, the development of new antibacterial agents is highly desireable.

Endophytes and hosts have formed a close interrelationship in the long-term evolution process, making endophytes an excellent resource for the production of natural antibacterial ingredients (Kusari et al., 2012; Gouda et al., 2016; Gupta et al., 2020). Our strategy intends to explore the active substances against Psa from the metabolites of the endophytic bacteria of the kiwifruit itself. Some progress has been made in our previous research. For example, 3-decalinoyltetramic acids and cytochalasins from the kiwifruit endophytic fungus Zopfiella sp. Showed anti-Psa activity (Yi et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021), while imidazole alkaloids from Fusarium tricinctum were characterized as anti-Psa agents (Ma et al., 2022). Bipolaris sp. Is also an endophytic fungus that was characterized from health kiwi plant. Our previous chemical investigation on this fungus yielded a series sesquiterpenoids (bipolarisorokins A–I) and xanthones with anti-Psa properties from the liquid fermented extract (Yu et al., 2022). In order to search for more anti-Psa agents from this fungus, we further investigated the fermentation products from the culture grown on rice medium. As a result, eight new terpenoids including five sesquiterpenoids (1–5) and three new sesterterpenoids (6–8), as well as five known analogues (9–13), have been obtained (Figure 1). Their structures have been identified by extensive spectroscopic methods, as well as quantum chemical calculations. All compounds were evaluated for their anti-Psa activity. Herein, the isolation, structure elucidation and anti-Psa activity of these isolates are reported.

Optical rotations were measured with an Autopol IV polarimeter (Rudolph, Hackettstown, NJ, United States ). UV spectra were obtained using a double beam spectrophotometer UH5300 (Hitachi High-Technologies, Tokyo, Japan). 1D and 2D NMR spectra were run on a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz spectrometer with TMS as an internal standard. Chemical shifts (δ) were expressed in ppm with references to the solvent signals. High resolution electrospray ionization mass spectra (HR-ESIMS) were recorded on a LC-MS system consisting of a Q Exactive™ Orbitrap mass spectrometer with an HRESI ion source (ThermoFisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) used in ultra-high-resolution mode (140,000 at m/z 200) and a UPLC system (Dionex UltiMate 3000 RSLC, ThermoFisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Column chromatography (CC) was performed on silica gel (200–300 mesh, Qingdao Marine Chemical Ltd., Qingdao, China), RP-18 gel (20–45 μm, Fuji Silysia Chemical Ltd., Kasugai, Japan), and Sephadex LH-20 (Pharmacia Fine Chemical Co., Ltd., Sweden). Medium-pressure liquid chromatography (MPLC) was performed on a Büchi Sepacore System equipped with a pump manager C-615, pump modules C-605, and a fraction collector C-660 (Büchi Labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland). Preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (prep-HPLC) was performed on an Agilent 1,260 liquid chromatography system equipped with Zorbax SB-C18 columns (5 μm, 9.4 mm × 150 mm, or 21.2 mm × 150 mm) and a DAD detector. Fractions were monitored by TLC (GF 254, Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China), and spots were visualized by heating silica gel plates sprayed with 10% H2SO4 in EtOH.

The fungus Bipolaris sp. Was isolated from fresh and healthy stems of kiwifruit plants (Actinidia chinensis Planch, Actinidiaceae), which were collected from the Cangxi county of the Sichuan Province (GPS: N 31°12′, E 105°76′) in July 2018. Each fungus was obtained simultaneously from at least three different healthy tissues. The strain was identified as one species of the genus Bipolaris by observing the morphological characteristics and analysis of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions. A living culture (internal number HFG-20180727-HJ32) has been deposited at the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, South-Central Minzu University, China.

The fungus Bipolaris sp. Was cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium for 7 days, which was used as “seed” to incubate in rice medium. The 500 ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 g rice and 80 ml distilled water in each were sterilized at 120°C for 15 min. Then the pieces of Bipolaris sp. PDA medium was inoculated into Erlenmeyer flasks. A total of a hundred 500 ml Erlenmeyer flasks were incubated statically in dark place at 25°C for 28 days.

The cultures of Bipolaris sp. Were extracted with 5 L methanol four times, and the total residue was obtained by reduced pressure evaporation. Then, the remaining aqueous phase was further extracted four times by EtOAc to afford a crude extract (45.0 g). The latter was subjected to silica gel CC (200–300 mesh) eluted with a gradient of CHCl3-MeOH (from 1:0 to 0:1, v/v) to obtain five fractions, A–E. Fraction B was separated by CC over silica gel with a gradient elution of the CHCl3-MeOH system (from 15:1 to 0:1, v/v) to give five fractions (Fr. B1–B5). Fraction B2 was applied to Sephadex LH-20 eluting with CHCl3-MeOH (1:1, v/v) and was separated by HPLC with MeCN-H2O (21:79, v/v, 4.0 ml/min) to obtain 6 (4.3 mg, retention time (tR) = 26.3 min), and 13 (5.2 mg, tR = 29.4 min). Fraction B3 was subjected to Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) and then further repeatedly purified by semipreparative HPLC with MeCN-H2O (32:68, v/v, 3.0 ml/min) to afford 11 (86.2 mg, retention time (tR) = 24.2 min) and 12 (94.3 mg, tR = 27.2 min). Fraction B4 was purified using semipreparative HPLC with MeCN-H2O (20:80, v/v, 4.0 ml/min) to afford 10 (7.8 mg, tR = 16.8 min) and 9 (9.6 mg, tR = 20.6 min). Fraction C was purified by semipreparative HPLC with MeCN-H2O (26:74, v/v, 4.0 ml/min) to afford 7 (4.8 mg, tR = 24.6 min) and 8 (7.3 mg, tR = 27.5 min). Fraction D was separated by CC over silica gel with a gradient elution of PE-acetone (from 50:1 to 0:1, v/v), and then was purified by semipreparative HPLC with MeCN-H2O (18:82, v/v, 4.0 ml/min) to obtain 1 (6.4 mg, tR = 29.6 min), 2 (3.8 mg, tR = 24.3 min), and 3 (7.6 mg, tR = 18.5 min). Fraction E was purified over Sephadex LH-20 eluted with MeOH, and was further separated using semipreparative HPLC with MeOH-H2O (78:22, v/v, 3.0 ml/min) to afford 4 (8.7 mg, tR = 38.2 min) and 5 (12.8 mg, tR = 34.3 min).

Bipolarisorokin J (1): colorless oil;

Bipolarisorokin K (2): colorless oil;

Bipolarisorokin L (3): colorless oil;

Bipolarisorokin M (4): colorless oil;

Bipolarisorokin N (5): colorless oil;

Bipolariterpene A (6): colorless oil;

Bipolariterpene B (7): colorless oil;

Bipolariterpene C (8): colorless oil;

The samples of 1 (1.5 mg each) were dissolved in pyridine (500 μl), and added with DMAP (2 mg) and (R)- or (S)-MTPA-Cl (10 μl) to the solution. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. The productions were individually purified by semipreparative HPLC and eluted with MeCN-H2O (78:22, v/v, 4.0 ml/min) to obtain the (S)-MTPA ester 1a (1.0 mg, tR = 14.0 min) and (R)-MTPA ester 1b (0.8 mg, tR = 14.0 min), respectively.

(S)-MTPA ester (1a). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): 1.44 (1H, d, J = 6.9 Hz, H-4a), 1.35 (1H, m, H-4b), 1.75 (1H, dd, J = 12.0, 6.7 Hz, H-5a), 0.88 (1H, m, H-5b), 1.06 (1H, overlap, H-6), 3.00 (1H, br s, H-7), 0.92 (3H, s, H-8), 1.03 (1H, overlap, H-9), 0.76 (3H, d, J = 5.8 Hz, H-10), 1.05 (3H, overlap, H-11), 2.01 (3H, s, H-12), 2.09 (1H, d, J = 9.4 Hz, H-13), 5.79 (1H, dd, J = 15.3, 9.4 Hz, H-14), 10.05 (1H, s, H-15), 5.62 (1H, dd, J = 15.3, 7.4 Hz, H-16), 5.55 (1H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, H-17), 3.74 (3H, s, H-19); positive ion HR-ESI-MS m/z 537.24640, [M + H]+, (calculated for C29H36F3O6+, 537.24585).

(R)-MTPA ester (1b). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): 1.43 (1H, m, H-4a), 1.34 (1H, m, H-4b), 1.74 (1H, m, H-5a), 0.83 (1H, m, H-5b), 1.01 (1H, overlap, H-6), 2.93 (1H, br s, H-7), 0.86 (3H, s, H-8), 1.00 (1H, overlap, H-9), 0.75 (3H, d, J = 5.3 Hz, H-10), 1.02 (3H, overlap, H-11), 1.98 (3H, s, H-12), 2.04 (1H, d, J = 9.4 Hz, H-13), 5.67 (1H, m, H-14), 10.02 (1H, s, H-15), 5.56 (1H, overlap, H-16), 5.57 (1H, overlap, H-17), 3.77 (3H, s, H-19); positive ion HR-ESI-MS m/z 559.22748, [M + Na]+, (calculated for C29H35F3NaO6+, 559.22779).

The NMR calculations were carried out using the Gaussian 16 software package (Frisch et al., 2010). Systematic conformational analyses were performed via SYBYL-X 2.1 using the MMFF94 molecular mechanics force field calculation with 10 kcal/mol of cutoff energy (Hehre, 2003; Shao et al., 2006). The optimization and frequency of conformers were calculated on the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level in the Gaussian 16 program package. All the optimized conformers in an energy window of 5 kcal/mol (with no imaginary frequency) were subjected to gauge-independent atomic orbital (GIAO) calculations of their 13C NMR chemical shifts, using density functional theory (DFT) at the mPW1PW91/6-311 + G (d,p) level with the PCM model. The calculated NMR data of these conformers were averaged according to the Boltzmann distribution theory and their relative Gibbs free energy. The 13C NMR chemical shifts for TMS were also calculated by the same procedures and used as the reference. After the calculation, the experimental and calculated data were evaluated by the improved probability DP4+ method (Grimblat et al., 2015).

All compounds were evaluated for their antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas syringae pv. Actinidae. The antibacterial assay was conducted by the previously described method (Yu et al., 2022). The sample to be tested was added into a 96-well culture plate, and the final compound concentration range from 4 to 256 μg/ml. Bacteria liquid was added to each well until the final concentration is 5 × 105 CFU/ml. It was then incubated at 27°C for 24 h, and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC, with an inhibition rate of ≥90%) was determined by the microplate reader at OD600 nm. The medium blank control was used in the experiment. Streptomycin was used as the positive control.

Bipolarisorokin J 1) was isolated as a colorless oil. The molecular formula was determined as C19H28O4 with six degrees of unsaturation based on the HRESIMS data (measured at m/z 343.18790 [M + Na]+, calcd for C19H28NaO4+ 343.18798). The 13C NMR data of 1 displayed 19 carbon signals, which were assigned as five methyls, two methylenes, eight methines, and four quaternary carbons in association with the HSQC data (Table 1). The 1H NMR data of 1 showed five methyl signals at δH 0.93 (3H, s, H-8), 0.75 (3H, d, J = 6.0 Hz, H-10), 1.04 (3H, overlap, H-11), 2.02 (3H, s, H-12), and 3.77 (3H, s, H-19), two olefinic protons at δH 5.68 (1H, ddd, J = 15.4, 9.5, 1.4 Hz, H-14) and 5.51 (1H, dd, J = 15.3, 5.8 Hz, H-16), and an aldehyde proton at δH 10.04 (H, s, H-15) (Table 1). The characteristic signals of 1D NMR, together with the data of analogues from the same origin, suggested that 1 was most likely a seco-sativene type sesquiterpenoid derivative. According to 1H−1H COSY spectrum, two structural fragments were deduced as shown with bold lines in Figure 2. Based on this, the HMBC correlations from δH 2.02 (3H, s, Me-12) to δC 165.9 (s, C-2), 52.4 (s, C-3) and δC 137.8 (s, C-1), from δH 0.93 (3H, s, Me-8) to C-2, C-3, 33.8 (t, C-4) and 63.5 (d, C-13), from δH 3.00 (1H, br s, H-7) to C-1, C-13, and δC 134.5 (d, C-14) established a seco-sativene type sesquiterpene backbone. In addition, one aldehyde group was connected to C-1, which was deduced from HMBC correlations from δH 10.04 (H, s, H-15) to δC 44.9 (d, C-7) and C-1. Furthermore, the HMBC correlations from δH 3.77 (3H, s, Me-19) and 4.58 (1H, dd, J = 5.8, 1.4 Hz, H-17) to δC 174.2 (s, C-18) suggested that the connections among C-17, C-18 and C-19. The planar structure of 1 was thus deduced as shown in Figure 2, resembling bipolarisorokin G (10) (Yu et al., 2022). The ROESY correlations (Figure 3) of H-13/H-8, H-13/H-6 and H-12/H-14 revealed that H-3, H-6, H-7 and H-8, were co-facial and assigned to be β-oriented. Correlations between H-13 and H-16, as well as large coupling constants (J = 15.4 Hz), confirmed the double bonds (C-14 and C-16) to be E-geometry. However, the geometry of H-17 cannot be determined by using the NOESY correlation. Regarding the same origin of 1 and 10, the absolute configuration of 1 thus was suggested to be the same as that of 10, except for C-17. However, the stereo-chemistry at C-17 was determined using a modifie Mosher’s method (Hoye et al., 2007). The observed differences of chemical shifts (Δδ = δS − δR) (Figure 4) indicated that the C-17 absolute configuration is R. Consequently, the absolute configuration of 1 was assigned as 3R, 6R, 7S, 13S, 17R.

Bipolarisorokin K (2), a colorless oil, was assigned the molecular formula of C19H28O5 with six degrees of unsaturation based on HRESIMS data (measured at m/z 359.18268 [M + Na]+, calcd for C19H28NaO4+ 359.18290). The 1H and 13C NMR data of 2 (Table 1) are closely similar to those of 1. The significant difference was the presence of a carboxyl group at C-15 (δC 169.9, s) in 2, instead of the aldehyde group in 1. This deduction was identified by the HMBC corrections from δH 2.93 (1H, br s, H-7) to δC 128.2 (s, C-1), δC 160.0 (s, C-2) and C-15, together with its HRESIMS data. Moreover, the absolute configuration of 2 was suggested to be the same with that of 1 based on the nearly identical NMR data, the biosynthetic pathway, and the consistent experimental ECD data of these two compounds (Figure 5).

Bipolarisorokin L 3) was obtained as a colorless oil. Its molecular formula was determined to be C18H26O4 based on HRESIMS data (measured at m/z 307.19046 [M + H]+, calcd for C18H27O4+ 307.19039). Comparing its 1D and 2D NMR data with those of 1 indicated that they shared almost the same chemical construction. However, the major difference was that the methyl ester group in 1 was replaced by a carboxyl group at C-18 in 3. The loss of a methoxy signal in the 13C NMR spectrum, the HMBC correlation from δH 4.52 (1H, dd, J = 5.9 Hz, 1.4 Hz, H-17) to δC 176.3 (s, C-18), and the mass data analysis confirmed the above deduction. The relative configurations of in 3 should be in agreement with the configuration of 1 based on the nearly identical NMR data. Finally, the experimental ECD curve of 3 matched well with that of 1 (Figure 5), suggesting that the absolute configuration of 3 was identical to that of 1.

Bipolarisorokin M 4) was obtained as a colorless oil. Its molecular formula of C33H48O5, together with ten degrees of unsaturation, were established by its HRESIMS data (measured at m/z 525.35706 [M + H]+, calcd for C33H49O5+ 525.35745). The 1H NMR data of 4 displayed signals for two olefinic protons, eight methyl groups, and two protons of aldehyde group (Table 2). The 13C NMR and DEPT data of 4 exhibited 33 carbon resonances, including eight methyls, five methenes (one oxygenated), twelve methines (one oxygenated, two olefinic and two aldehyde carbons), seven nonprotonated carbons (four olefinic and one ester carbonyl) (Table 2). After literature investigations, the aforementioned NMR data indicated that compound 4 should comprise of two different seco-sativene sesquiterpenoid units. Interpretation of the 1H−1H COSY spectrum of 4 revealed the presence of four discrete proton−proton spin systems as shown with bold lines in Figure 2. Further analysis of its HMBC spectra demonstrated the existence of two building blocks of units A and B, which were highly similar to 3 and 11, respectively. The above deduction was confirmed by the HMBC correlations as shown in Figure 2, together with comparison of the 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data. Meanwhile, the key HMBC correlation from δH 3.80 (1H, dd, J = 10.9 Hz, 8.9 Hz, H-14′a) and 4.25 (1H, dd, J = 11.0 Hz, 5.8 Hz, H-14′b) to δC 173.8 (s, C-18), along with analysis of the HRESIMS data, suggested the connection by an ester bond between units A and B. Therefore, considering similar NMR data and coupling constants, as well as their concurrent biogenetic relationship, the absolute configurations of 4 should agree with those of 3 and 11, respectively. Finally, the structure of 4 was established as depicted in Figure 1.

Bipolarisorokin N 5) was also isolated as a colorless oil. Its molecular formula was established as C33H48O6 based on the HRESIMS ion peak at m/z 541.35254 [M + H]+ (calcd for C33H49O6+, 541.35237), corresponding to ten degrees of unsaturation. The 1D NMR data of 5 closely resembled those of 4 (Table 2), except for the obviously shifted signal of C-15′ (−16.8 ppm) and the absence of aldehyde hydrogen proton signal at H-15′. The HMBC correlations from δH 3.06 (1H, br s, H-7′) to δC 126.0 (s, C-1′) and 171.3 (s, C-15′), as well as the HRESIMS data analysis, led to the location of a carboxyl group (C-15′) at C-1′. Furthermore, the similar ROESY data and experimental ECD curves of 4–5 (Figure 5) suggested that they shared the same absolute configuration. Therefore, the structure of 5 was finally established as shown in Figure 1.

Bipolariterpene A 6) was assigned a molecular formula of C27H40O6 with eight degrees of unsaturation based on its HRESIMS data (measured at m/z 483.27176 [M + Na]+, calcd for C27H40NaO6+ 483.27171). The 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 3) showed 27 carbon resonances comprising five methyls (δC 16.8, 15.5, 10.5, 14.7, and 20.8); eight methylenes including six aliphatic ones (δC 40.5, 41.3, 24.3, 31.4, 31.0, and 30.2) and two oxygenated ones at δC 59.5 and 67.6; six methines including two aliphatic ones at δC 50.7 and 35.2, three olefinic ones (δC 123.3, δC 128.7 and δC130.0), and a oxygenated one at δC 77.1; eight non-protonated carbons with a aliphatic one at δC 50.2, five olefinic ones (δC 138.6, δC 137.6 × 2, δC 149.9, δC 149.5), a carbonyl one at δC 209.9, and a ester carbonyl one at δC 172.7. The general features of its NMR data closely resembled those of the co-isolated known bicyclic sesterterpene fusaproliferin 13) (Nihashi et al., 2002; Gao et al., 2020). The major difference was that an additional hydroxy group was substituted at C-21 in 6, which could be fully established through the HMBC corrections from δH 4.20 (1H, d, J = 12.0 Hz, H-21a) and 4.08 (1H, d, J = 12.0 Hz, H-21b) to δC 128.7 (d, C-7), 137.6 (s, C-8) and 31.4 (t, C-9). The ROESY correlations between Me-20/H-2b, H-3/H-5b, H-21a/H-6a, H-7/H-9a, H-11/H-13, Me-22/H-14b indicated that the configurations of C-3/C-4, C-7/C-8, and C-12/C-13 double bonds were assigned as E, Z, and E, respectively. Furthermore, as indicated by its ROESY spectrum, the cross-peaks of H-11/H-13, H-13/H-15, H-15/H-23 suggested that H-11, H-15 and H-23 is β-oriented. Meanwhile, the key interaction of H-14b/Me-19, Me-22/Me-19 and H-14b/Me-22, along with the lack of H-15/Me-19, implied that Me-19 was α-oriented. Thus, compound 6 was determined to share the same stereochemistry with that of 13 for which the absolute configuration had been earlier confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis (Santini et al., 1996) and total enantioselective synthesis (Myers et al., 2002). By comparing the specific rotation of 6 (

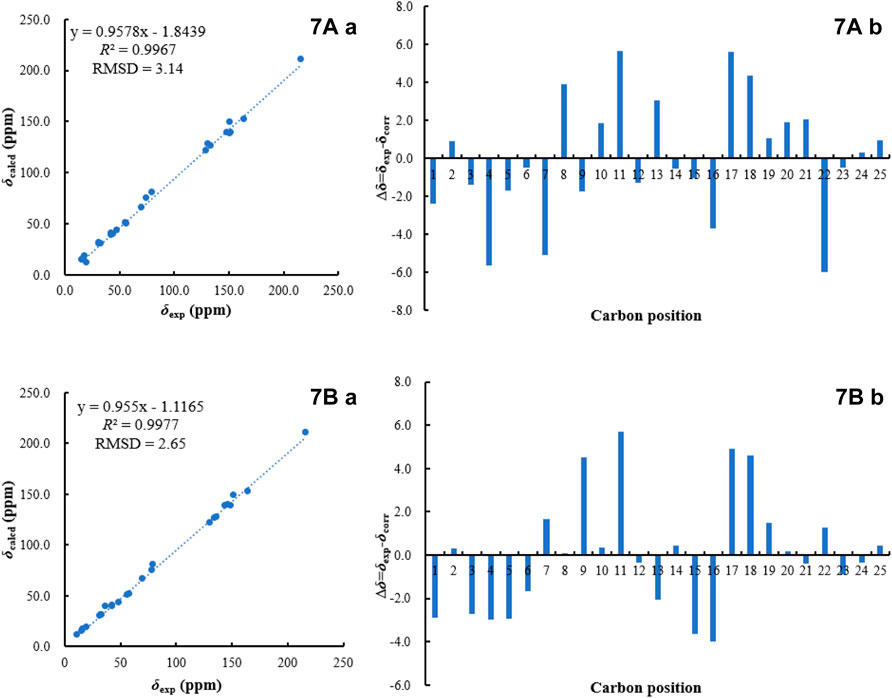

Bipolariterpene B 7) was obtained as a colorless oil. The molecular formula of 7 was assigned as C25H38O5 based on its HRESIMS spectrum (measured at m/z 441.26044 [M + Na]+, calcd for C25H38NaO5+ 441.26115), which showed two fewer carbon atoms than fusaproliferin (13) (Nihashi et al., 2002). Additionally, the 1H and 13C NMR data of 7 were similar to those of 13 (Table 3). The significant difference between 7 and 13 was the absence of an acetyl group in 7, which was confirmed by the HMBC correlations from δH 3.82 (1H, m, H-24a) and 3.68 (1H, dd, J = 10.4, 6.5 Hz, H-24b) to δC 14.6 (q, C-25), 38.8 (d, C-23) and 152.2 (s, C-16), together with its HRESIMS data. Moreover, the HMBC correlations from δH 1.26 (3H, s, H-21) to δC 138.0 (d, C-7), 74.3 (s, C-8) and 39.0 (t, C-9), as well as chemical shift of C-8, indicated that an additional hydroxy group was located at C-8. Furthermore, the HMBC correlations from δH 5.75 (1H, m, H-6) and 5.48 (1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz, H-7) to δC 42.9 (t, C-5) and C-8, along with the observed 1H−1H COSY cross-peak of δH 2.78 (2H, m, H-5)/H-6/H-7, confirmed that one double bond between C-7 and C-8 in 13 migrated to C-6 and C-7 in 7. Based on the biogenetic and NOESY data consideration, the absolute configuration of 7 was proposed to be consistent with the known compound 13, except for C-8. To determine its absolute configuration, the NMR calculations with DP4+ analysis for two possible isomers (1S, 8R, 11S, 15R, 23S)-7A and (1, 8, 11S, 15R, 23S)-7B were carried out using the GIAO method at the mPW1PW91/6-311+G (d,p) level with the PCM model. As a result, the calculated chemical shifts of 7B matched well with the experimental ones (Figure 6), showing a better correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.9977) and a low root-mean-square deviation value (RMSD = 2.65), together with a high DP4+ probability of 100% (all data) probability (Supplementary Tables S3 in the Supporting Information). Hence, compound 7 was identified as shown in Figure 1 and named as bipolariterpene B.

FIGURE 6. 13C NMR calculation results of two possible isomers of 7 (A): Linear correlation plots of predicted versus experimental 13C NMR chemical shift. (B) Relative errors between the predicted δC of two potential structures and recorded δC.).

Bipolariterpene C 8) was also isolated as a colorless oil. Its molecular formula was established as C27H40O6 based on the HRESIMS ion peak at m/z 461.28955 [M + H]+ (calcd for C27H41O6+, 461.28977), suggesting eight degrees of unsaturation. Analyses of NMR spectra (Table 3) indicated that the structure of 8 was explicitly similar to that of fusaprolifin A (Liu et al., 2013). However, the signals for two olefinic methines were replaced by signals of a methylene δC 30.1 (t, C-6) and an oxygenated methine δC 75.7 (d, C-7). These observations indicated the hydration of the double bond in fusaprolifin A, leading to the location of a hydroxy group at C-7 in 8. It was supported by HMBC correlations from δH 3.38 (1H, dd, J = 8.1, 3.7 Hz, H-7) to δC 35.3 (t, C-5), 30.1 (t, C-6), 74.8 (s, C-8), 35.3 (t, C-9) and 24.6 (q, C-21), along with the 1H–1H COSY cross peaks of H-5/H-6/H-7. Furthermore, the chiral centers in 8, except for C-7, were found to be identical to that of fusaprolifin A based on their highly similar coupling constant and ROESY data. In order to confirm the assigned chemical architecture of 8 and its the stereochemistry, the 13C NMR calculations and DP4+ analysis of (1S, 7R, 8S, 11R, 15R, 23S)-8A and (1, 7, 8S, 11R, 15R, 23S)-8B were carried out at the mPW1PW91/6-311+G (d,p) level. The results showed that 8A was the most likely structure based on a better correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.9970) and a low root-mean-square deviation value (RMSD = 3.05), as well as a high DP4 + probability of 100% (all data) probability (Supplementary Figure S6 and Supplementary Table S6 in the Supporting Information). Finally, the absolute configuration of 8 was defined.

In addition, the structures of five known compounds were identified as bipolarisorokin H (9), bipolarisorokin G (10), helminthosporol (11), helminthosporic acid (12) and fusaproliferin (13), by comparing the spectral data with those reported in the literature (Osterhage et al., 2002; Abdel-Lateff et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2022). In this study, compounds 1 and 2 were isolated as methyl esters, which could be derived from the separation process since methanol was used as the solvent. To verify whether these compounds are of natural origin, we analyzed the ethanol extract of the fermentation broth of the fungus by HPLC (see Supporting Information). As a results, all compounds could be confirmed their natural attributes.

Structurally, compound 9 possessed two additional skeletal carbons, while compounds 1–5 and 10 possessed three additional skeletal carbons, which might be derived from acetyl-CoA or acetoacetyl-CoA. Compounds 11 and 12 were isolated as major components, which were most probably employed as the original precursor to assemble the above compounds. The hydroxyl group at C-14 in 11 was oxidized to produce an aldehyde product, which then underwent aldol condensation with the acetyl-CoA to give 9. Similarly, the aldehyde product combined an acetoacetyl-CoA to give compounds 1–3 and 10. Finally, additional esterification happened between 3 and 11 or 12 led to the formation of 4 or 5, respectively Scheme 1.

All compounds (1–13) were evaluated for their anti-Psa activity by using the method as described previously (Yu et al., 2022). Streptomycin was used as the positive control. As a result, compounds 4 and 5 showed certain inhibitory activity, with MICs of 32 and 64 μg/ml, respectively. Additionally, compounds 1–3, and 10 showed weak activity, with MICs of 128 μg/ml (Table 4). The results demonstrated that the additional skeletal carbons of seco-sativene sesquiterpenoids may be vital for Psa inhibitory activity.

In conclusion, eight new terpenoids (1–8), along with five known analogues (9–13) was identified from the culture medium of an endophyte Bipolaris sp, a fungus isolated from fresh and healthy stems of kiwifruit plants. Compounds 1–3, together with the known compound 10, represented novel structures of seco-sativene sesquiterpenoids possessing three additional skeletal carbons, which were only found in this fungus. In addition, compounds 4 and 5 were rare seco-sativene/seco-sativene adducts. In anti-Psa activity assay, compounds 4 and 5 displayed certain inhibitory activity against Psa. This study, together with our previous work (Yu et al., 2022), further supported that it is an effective approach to search for anti-Psa agents from endophytic fungi of kiwi plant itself. The endophyte Bipolaris sp. Could be a potential antibacterial strain, while its sativene sesquiterpene products could be potential anti-Psa agents.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

J-JY: methodology, data curation, writing—original draft preparation. W-KW: methodology, data curation. YZ: data curation, methodology. RC: writing—review and editing. JH: conceptualization, funding acquisition. J-KL: funding acquisition. TF: conceptualization, project administration, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing.

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22177139, 21961142008) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, South-Central Minzu University (CZP21001).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2022.990734/full#supplementary-material

Abdel-Lateff, A., Okino, T., Alarif, W. M., and Al-Lihaibi, S. S. (2013). Sesquiterpenes from the marine algicolous fungus Drechslera sp. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 17 (2), 161–165. doi:10.1016/j.jscs.2011.03.002

Bardas, G. A., Veloukas, T., Koutita, O., and Karaoglanidis, G. S. (2010). Multiple resistance of botrytis cinerea from kiwifruit to SDHIs, QoIs and fungicides of other chemical groups. Pest Manag. Sci. 66 (9), 967–973. doi:10.1002/ps.1968

Colombi, E., Straub, C., Kunzel, S., Templeton, M. D., Mccann, H. C., and Rainey, P. B. (2017). Evolution of copper resistance in the kiwifruit pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae through acquisition of integrative conjugative elements and plasmids. Environ. Microbiol. 19 (2), 819–832. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13662

Dolly, S., Kaur, J., Bhadariya, V., and Sharma, K. (2021). Actinidia deliciosa (kiwi fruit): A comprehensive review on the nutritional composition, health benefits, traditional utilization and commercialization. J. Food Process. Preserv. 45, e15588. doi:10.1111/jfpp.15588

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., et al. (2010). Gaussian 09, revision D. 01. Wallingford CT: Gaussian, Inc.

Gao, Y., Stuhldreier, F., Schmitt, L., Wesselborg, S., Wang, L., Müller, W. E. G., et al. (2020). Sesterterpenes and macrolide derivatives from the endophytic fungus Aplosporella javeedii. Fitoterapia 146, 104652. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2020.104652

Gouda, S., Das, G., Sen, S. K., Shin, H.-S., and Patra, J. K. (2016). Endophytes: A treasure house of bioactive compounds of medicinal importance. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1538. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01538

Grimblat, N., Zanardi, M. M., and Sarotti, A. M. (2015). Beyond DP4: An improved probability for the stereochemical assignment of isomeric compounds using quantum chemical calculations of NMR shifts. J. Org. Chem. 80 (24), 12526–12534. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.5b02396

Gupta, S., Chaturvedi, P., Kulkarni, M. G., and Van Staden, J. (2020). A critical review on exploiting the pharmaceutical potential of plant endophytic fungi. Biotechnol. Adv. 39, 107462. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2019.107462

Hehre, W. J. (2003). A guide to molecular mechanics and quantum chemical calculations. Irvine, CA: Wavefunction, Inc. 51, 1–812. doi:10.1117/1.OE.51.8.083604

Hoye, T. R., Jeffrey, C. S., and Shao, F. (2007). Mosher ester analysis for the determination of absolute configuration of stereogenic (chiral) carbinol carbons. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2451–2458. doi:10.1038/nprot.2007.354

Kusari, S., Hertweck, C., and Spitellert, M. (2012). Chemical ecology of endophytic fungi: Origins of secondary metabolites. Chem. Biol. 19 (7), 792–798. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.06.004

Liu, D., Li, X. M., Li, C. S., and Wang, B. G. (2013). Sesterterpenes and 2H-Pyran-2-ones (=alpha-Pyrones) from the mangrove-derived endophytic fungus Fusarium proliferatum MA-84. Helv. Chim. Acta 96 (3), 437–444. doi:10.1002/hlca.201200195

Ma, J. T., Du, J. X., Zhang, Y., Liu, J. K., Feng, T., and He, J. (2022). Natural imidazole alkaloids as antibacterial agents against Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae isolated from kiwi endophytic fungus Fusarium tricinctum. Fitoterapia 156, 105070. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2021.105070

McCann, H. C., Li, L., Liu, Y. F., Li, D. W., Pan, H., Zhong, C. H., et al. (2017). Origin and evolution of the kiwifruit canker pandemic. Genome Biol. Evol. 9 (4), 932–944. doi:10.1093/gbe/evx055

Myers, A. G., Siu, M., and Ren, F. (2002). Enantioselective synthesis of (-)-terpestacin and (-)-fusaproliferin: Clarification of optical rotational measurements and absolute configurational assignments establishes a homochiral structural series. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 4230–4232. doi:10.1021/ja020072l

Nihashi, Y., Lim, C.-H., Tanaka, C., Miyagawa, H., and Ueno, T. (2002). Phytotoxic sesterterpene, 11-epiterpestacin, from Bipolaris sorokiniana NSDR-011. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 66 (3), 685–688. doi:10.1271/bbb.66.685

Osterhage, C., Konig, G. M., Holler, U., and Wright, A. D. (2002). Rare sesquiterpenes from the algicolous fungus Drechslera dematioidea. J. Nat. Prod. 65 (3), 306–313. doi:10.1021/np010092l

Renzi, M., Copini, P., Taddei, A. R., Rossetti, A., Gallipoli, L., Mazzaglia, A., et al. (2012). Bacterial canker on kiwifruit in Italy: Anatomical changes in the wood and in the primary infection sites. Phytopathology 102 (9), 827–840. doi:10.1094/phyto-02-12-0019-r

Richardson, D. P., Ansell, J., and Drummond, L. N. (2018). The nutritional and health attributes of kiwifruit: A review. Eur. J. Nutr. 57 (8), 2659–2676. doi:10.1007/s00394-018-1627-z

Santini, A., Ritieni, A., Fogliano, V., Randazzo, G., Mannina, L., Logrieco, A., et al. (1996). Structure and absolute stereochemistry of fusaproliferin, a toxic metabolite from Fusarium proliferatum. J. Nat. Prod. 59 (2), 109–112. doi:10.1021/np960023k

Scortichini, M. (2018). Aspects still to solve for the management of kiwifruit bacterial canker caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae biovar 3. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 83 (4), 205–211. doi:10.17660/eJHS.2018/83.4.1

Scortichini, M., Marcelletti, S., Ferrante, P., Petriccione, M., and Firrao, G. (2012). Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae: A re-emerging, multi-faceted, pandemic pathogen. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13 (7), 631–640. doi:10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00788.x

Serizawa, S., Ichikawa, T., Takikawa, Y., Tsuyumu, S., and Goto, M. (1989). Occurrence of bacterial canker of kiwifruit in Japan description of symptoms, isolation of the pathogen and screening of bactericides. Jpn. J. Phytopathol. 55 (4), 427–436. doi:10.3186/jjphytopath.55.427

Shao, Y., Molnar, L. F., Jung, Y., Kussmann, J., Ochsenfeld, C., Brown, S. T., et al. (2006). Advances in methods and algorithms in a modern quantum chemistry program package. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 8 (27), 3172–3191. doi:10.1039/B517914A

Vanneste, J. L. (2017). “The scientific, economic, and social impacts of the New Zealand outbreak of bacterial canker of kiwifruit (Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae),” in Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. Palo Alto: Annual Reviews. Editors J. E. Leach, and S. E. Lindow, 377–399.

Wicaksono, W. A., Jones, E. E., Casonato, S., Monk, J., and Ridgway, H. J. (2018). Biological control of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae (Psa), the causal agent of bacterial canker of kiwifruit, using endophytic bacteria recovered from a medicinal plant. Biol. Control 116, 103–112. doi:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2017.03.003

Yi, X. W., He, J., Sun, L. T., Liu, J. K., Wang, G. K., and Feng, T. (2021). 3-Decalinoyltetramic acids from kiwi-associated fungus Zopfiella sp. and their antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas syringae. RSC Adv. 11, 18827–18831. doi:10.1039/D1RA02120F

Yu, J. J., Jin, Y. X., Huang, S. S., and He, J. (2022). Sesquiterpenoids and xanthones from the kiwifruit-associated fungus Bipolaris sp. and their anti-pathogenic microorganism activity. J. Fungi (Basel). 8 (1), 9. doi:10.3390/jof8010009

Keywords: endophytic fungus, Bipolaris sp., sesquiterpenoids, sesterterpenoids, antibacterial activity

Citation: Yu J-J, Wei W-K, Zhang Y, Cox RJ, He J, Liu J-K and Feng T (2022) Terpenoids from Kiwi endophytic fungus Bipolaris sp. and their antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae. Front. Chem. 10:990734. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.990734

Received: 10 July 2022; Accepted: 08 August 2022;

Published: 01 September 2022.

Edited by:

Allan Patrick Macabeo, University of Santo Tomas, PhilippinesReviewed by:

Chung Sub Kim, Sungkyunkwan University, South KoreaCopyright © 2022 Yu, Wei, Zhang, Cox, He, Liu and Feng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Juan He, MjAxNTA0OEBtYWlsLnNjdWVjLmVkdS5jbg==; Ji-Kai Liu, bGl1amlrYWlAbWFpbC5zY3VlYy5lZHUuY24=; Tao Feng, dGZlbmdAbWFpbC5zY3VlYy5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.