94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem., 24 August 2021

Sec. Organic Chemistry

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2021.734822

This article is part of the Research TopicAdvances and Future Trends in Bioactive Natural Products: Insights into Total Synthesis and Their Biological and Biomedical ApplicationsView all 4 articles

Two known azaphilone derivatives, 4,6-dimethylcurvulinic acid (1) and austdiol (2), and their novel heterotrimer, muyophilone A (3), were isolated and identified from an endophytic fungus, Muyocopron laterale 0307-2. Their structures and stereochemistry were established by extensive spectroscopic analyses including HRMS, NMR spectroscopy, electronic circular dichroism (ECD) and vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) spectroscopic methods, as well as single crystal X-ray diffraction. In the structure of 3, two compound 2-derived azaphilone units were connected through an unprecedented five-membered carbon bridge which was proposed to be originated from compound 1. Compound 3 represents the first example of azaphilone heterotrimers.

Azaphilones or azaphilonoids, a large family of naturally occurring fungal polyketides, have attracted considerable attention owing to their diverse structures and intriguing biological activities (Pavesi et al., 2021). Since the discovery of the best known fungal mycotoxin citrinin in 1931 (Hetherington and Raistrick, 1931), more than 600 azaphilones have been isolated and identified from diverse fungal genera, such as Penicillium, Talaromyces, Aspergillus, and Chaetomium species (Osmanova et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2020). Their structures are typically characterized by the presence of a pyrone-quinone bicyclic skeleton and a quaternary carbon center (Osmanova et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2020). The substitution and cyclization of different side chains, as well as the polyketide dimerization, greatly contribute to the structural diversity and complexity of azaphilones (Yin et al., 2017). Further incorporation of amines by the exchange of pyrane oxygen for nitrogen affords red or purple vinylogousγ-pyridones and also increases the number of azaphilones (Akihisa et al., 2005; Wei and Yao, 2005). Azaphilones exhibited a large range of biological activities, such as antimicrobial, cytotoxic, antioxidant, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory activities (Osmanova et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2020).

During our continuing search for biologically active secondary metabolites from fungal endophytes harbored in the medicinal plant Blumea balsamifera (Yuan et al., 2019), an endophyte Muyocopron laterale 0307-2 was isolated and chemically investigated. Three azaphilones including two known ones, 4,6-dimethylcurvulinic acid (1) and austdiol (2), and their novel trimeric derivative, muyophilone A (3), were obtained. By carefully searching azaphilone structures and to the best of our knowledge (Osmanova et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2020), the presence of a polysubstituted five-membered 1,3-diketone in compound 3 is unprecedented among azaphilones and their dimers or trimers (Figure S1). Here, we report their isolation, structural elucidation, as well as proposed biosynthetic pathway.

Compound 1 (Figure 1) was obtained as a white powder and compound 2 (Figure 1) was isolated as a yellow powder. They were identified as known azaphilones, 4,6-dimethylcurvulinic acid and austdiol, respectively, based on the comparison of their 1H and 13C NMR data with those reported in the literature (Supplementary Figures S2, S3) (Liu et al., 2017; de Oliveira et al., 2019). The absolute configuration of 2 was further confirmed to be 7R, 8S by single crystal X-ray diffraction and ECD calculation (Supplementary Figures S4, S5) (Presti et al., 2003).

Compound 3 (Figure 1) was also obtained as yellow powder. Its molecular formula was established as C31H32O10 by analysis of ESI-HRMS at m/z 565.2066 [M + H]+ (Supplementary Figure S12). The 1H NMR spectrum (Supplementary Figure S6) showed the presence of six singlet methyls (δH 0.99, 1.06, 1.09, 1.93, 2.21, and 2.23), two methylenes (δH 2.49, 1H, d, J = 14.0 Hz; δH 2.67, 1H, d, J = 14.0 Hz; δH 3.32, 1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz; δH 3.41, 1H, d, J = 15.5 Hz), two oxygenated methines (δH 4.33, and 4.52), and four olefinic or aromatic protons (δH 6.28, 6.50, 7.39, and 7.44). The 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S7) in combination with HSQC spectrum (Supplementary Figure S8) confirmed the presence of six methyls, two methylenes, two oxygenated methines, three quaternary carbons (two oxygenated), and 14 olefinic/aromatic carbons (four oxygenated), together with four ketones. These data accounted for all 1H and 13C NMR resonances.

The planar structure of 3 was constructed by detailed analysis of HMBC spectrum (Supplementary Figure S9). Key HMBC correlations from H3-9 to C-3 and C-4, from H-4 to C-4a and C-8a, and from H-1 to C-3 and C-4a (Figure 2), coupled with the requirement of chemical shifts of C-1 (δC 146.1) and C-3 (δC 161.7) identified a γ-pyran ring with a methyl at C-3. Further analysis of key HMBC correlations of H3-10/C-6, H3-10/C-7, H3-10/C-8, H-8/C-8a, H2-11/C-4a, H2-11/C-5, and H2-11/C-6 (Figure 2), as well as the chemical shifts of C-6 (δC 199.2), C-7 (δC 77.7), and C-8 (δC 72.9) demonstrated an azaphilonoid moiety. This substructure was similar to that of co-isolated austdiol (2), except for the C-11 methylene in 3 instead of aldehyde group in 2.

A five-membered carbon ring, 1,3-diketone moiety, was further verified and connected to C-11 on the basis of the key HMBC correlations of H2-11 with C-12 and C-16, of H3-17 with C-12, C-13, and C-14, and of H3-18 with C-14, C-15, and C-16 (Figure 2), as well as the chemical shifts of C-14 (δC 207.8) and C-16 (δC 207.2) (Table 1). Another austdiol (2)-derived azaphilone moiety was confirmed to be present in the structure of 3 by HMBC correlations as shown in Figure 2. It was linked to C-15 of the five-membered ring by the key HMBC correlations of H3-18 with C-11′, which was also consistent with the MS requirement. The above results indicated that compound 3 is anazaphilone that contained two austdiol (2)-derived units.

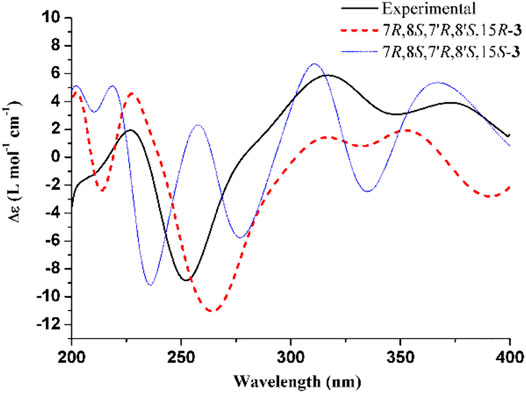

Considering the same biosynthetic origin and the classical structural characteristics of azaphilone dimers or trimers (Supplementary Figure S1), the stereochemistry of azaphilone monomers in 3 should be same to that of 7R,8S-austdiol (2), revealing a 7R,8S,7′R,8′S configuration for 3. In accordance of our previous computational study on absolute configurations assignments for natural products (Cao et al., 2019; Ren et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2016). the electronic circular dichroism (ECD) calculations and vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) (Mazzeo et al., 2013; Mándi and Kurtán, 2019; Mazzeo et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2020) were performed to clarify the absolute configuration of C-15 of 3.

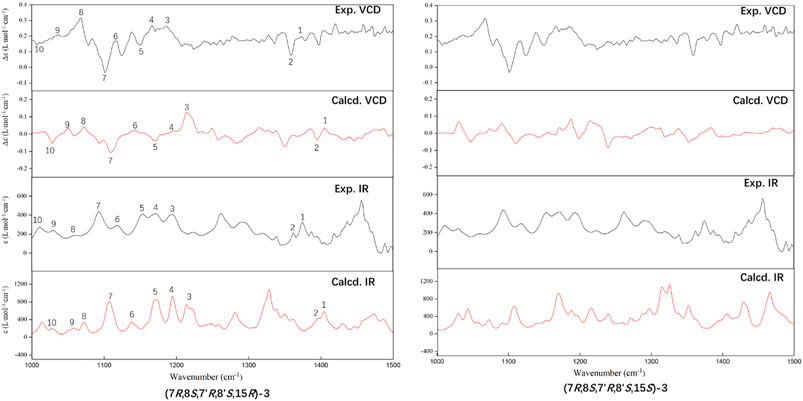

The experimental ECD and VCD conditions are shown in the experimental section in the Supplementary Material. The procedure for the ECD and VCD computation is shown in Scheme 1. Conformational searches for compound 3 were first performed using the MMFF94S force field (Halgren, 1999) and the resulted conformers within 0–10 kcal/mol (Supplementary Table S1) were optimized through density functional theory (DFT). The benchmark performed suggests the dispersion-corrected functional B3LYP-D3BJ owns a high accuracy, and the method is proposed for biochemically relevant systems (Pracht and Grimme, 2021; Katsyuba et al., 2019). Those conformers within 0–10 kcal/mol were optimized through the B3LYP-D3BJ/6-31G(d) level, and the optimized structures with relative energies ranging from 0 to 4 kcal/mol were further re-optimized at the B3LYP-D3BJ/6-311G (2d,p) level (Rassolov et al., 1998). The ECD computations were performed at the TDDFT/B3LYP/6-311G (2d,p)/SMD (methanol) level, and the VCD and IR computations were performed at the B3LYP/6-311G (2d,p)/SMD (chloroform) level (Marenich et al., 2009). All the computations are performed in the Gaussian09 programs (Frisch et al., 2009). The Cartesian coordinates of all conformers and corresponding energies are presented in the Supplementary Material. As showed in Figure 3, the calculated ECD spectrum of (7R,8S,7′R,8′S,15S)-3 had a positive Cotton effect near 262 nm. However, the experimental ECD had a negative Cotton effect at 254 nm. In contrast, the (7R,8S,7′R,8′S,15R)-3 had a negative Cotton effect at 265 nm. Therefore, ECD curve of (7R,8S,7′R,8′S,15R)-3 is in good agreement with the experimental curve. The VCD study gives the consistent result, and the predicted vibrational modes 1 to 10 labelled in the Figure 4 for (7R,8S,7′R,8′S,15R)-3 are in good agreement with the experimental results. Besides, the similarity factor (Bruhn et al., 2013; Rodriguez-Garcia et al., 2019) issued to quantify the degree of matching of VCD curves with the SpecDis software (Bruhn et al., 2017), and the value of (7R,8S,7′R,8′S,15R)-3 is 0.5838 which is significantly higher than that for (7R,8S,7′R,8′S,15S)-3 (0.4096). In conclusion, the absolute configuration of 3 is finally assigned as 7R,8S,7′R,8′S,15R.

FIGURE 3. Experimental ECD spectrum of 3 and calculated ECD spectra for (7R,8S,7′R,8′S,15R)-3 and (7R,8S,7′R,8′S,15S)-3. The band width was set to 0.18 eV.

FIGURE 4. Comparison of the calculated (Calcd.) VCD and IR spectra of (7R,8S,7′R,8′S,15R)-3 and (7R,8S,7′R,8′S,15S)-3 with the experimental (Exp.) spectra of 3. The band half-width is 4 cm−1.

Compound 3 features a polysubstituted five-membered ring, 1,3-diketone, which acts as an unprecedented bridge with the attachment of two austdiol (2)-derived azaphilone wings. This structural feature is unprecedented among azaphilones and their dimers or trimers (Supplementary Figure S1). Based on the structural characteristics of 3 (Pavesi et al., 2021; Powers et al., 2019), its biosynthetic pathway is proposed as shown in Scheme 2. A linear PKS biosynthetic precursor was first constructed from a polyketide chain (pentaketide) followed by cyclization and oxidation to afford compound 1 or 2. Further heterotrimerization between one molecule 1 and two molecules 2 formed the final product 3. During this heterotrimerization, perhaps the most intriguing step is the proposed oxidation-rearrangement in the six-membered ring of 1 to produce the five-membered 1,3-diketone in 3. Following the established bioassay methods in our laboratory, the novel compound muyophilone A (3) was evaluated for antibacterial activities (against Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa), and antifungal activity (against Candida albicans). Unfortunately, no inhibitory activities were observed.

In summary, muyophilone A (3) represents a new family of azaphilone trimers featuring an unprecedented five-membered carbon bridge, expanding the structural diversity of azaphilones. The unique biosynthetic pathway of 3 is worth unveiling in future study.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

CY and YG drafted the manuscript; KW and ZW performed the bioassay; LL and HZ computed the ECD and VCD spectra; GL designed the strategy.

This work was financially supported by the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 220RC718), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81903494, 21877025, 21903018), and Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund for Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences (No. 1630032019005).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2021.734822/full#supplementary-material

Akihisa, T., Tokuda, H., Yasukawa, K., Ukiya, M., Kiyota, A., Sakamoto, N., et al. (2005). Azaphilones, Furanoisophthalides, and Amino Acids from the Extracts of Monascus Pilosus-Fermented Rice (Red-Mold Rice) and Their Chemopreventive Effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 562–565. doi:10.1021/jf040199p

Bruhn, T., Schaumlöffel, A., Hemberger, Y., and Bringmann, G. (2013). SpecDis: Quantifying the Comparison of Calculated and Experimental Electronic Circular Dichroism Spectra. Chirality 25, 243–249. doi:10.1002/chir.22138

Bruhn, T., Schaumlöffel, A., Hemberger, Y., and Pescitelli, G. (2017). SpecDis Version 1.71. Berlin, Germany: University of Pisa. Available at: http:/specdis-software.jimdo.com.

Cao, F., Meng, Z.-H., Mu, X., Yue, Y.-F., and Zhu, H.-J. (2019). Absolute Configuration of Bioactive Azaphilones from the Marine-Derived Fungus Pleosporales Sp. CF09-1. J. Nat. Prod. 82, 386–392. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b01030

Chen, C., Tao, H., Chen, W., Yang, B., Zhou, X., Luo, X., et al. (2020). Recent Advances in the Chemistry and Biology of Azaphilones. RSC Adv. 10, 10197–10220. doi:10.1039/D0RA00894J

de Oliveira, L., Ishida, A., da Silva, C., Carvalho, J., Feitosa, A., Marinho, P., et al. (2019). Antibacterial Activity of Austdiol Isolated from Mycoleptodiscus Indicus against Xanthomonas Axonopodis Pv. Passiflorae. Rev. Virtual Quim 11, 596–604. doi:10.21577/1984-6835.20190045

Ding, W.-Y., Yan, Y.-M., Meng, X.-H., Nafie, L. A., Xu, T., Dukor, R. K., et al. (2020). Isolation, Total Synthesis, and Absolute Configuration Determination of Renoprotective DimericN-Acetyldopamine-Adenine Hybrids from the Insect Aspongopus Chinensis. Org. Lett. 22, 5726–5730. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01593

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., et al. (2009). Gaussian 09, Revision B.01. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc..

Gao, J.-M., Yang, S.-X., and Qin, J.-C. (2013). Azaphilones: Chemistry and Biology. Chem. Rev. 113, 4755–4811. doi:10.1021/cr300402y

Halgren, T. A. (1999). MMFF VI. MMFF94s Option for Energy Minimization Studies. J. Comput. Chem. 20, 720–729. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-987x(199905)20:7<720::aid-jcc7>3.0.co;2-x

Hetherington, A. C., and Raistrick, H. (1931). Studies in the Biochemistry of Micro-organisms. Part XIV.-On the Production and Chemical Constitution of a New Yellow Colouring Mater, Citrinin, Produced from Glucose by Penicillium. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 220, 269–295. doi:10.1098/rstb.1931.0025

Katsyuba, S. A., Zvereva, E. E., and Grimme, S. (2019). Fast Quantum Chemical Simulations of Infrared Spectra of Organic Compounds with the B97-3c Composite Method. J. Phys. Chem. A. 123, 3802–3808. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.9b01688

Liu, F., Tian, L., Chen, G., Zhang, L.-h., Liu, B., Zhang, W., et al. (2017). Two New Compounds from a marine-derived Penicillium griseofulvum T21-03. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 19, 678–683. doi:10.1080/10286020.2016.1231671

Lo Presti, L., Soave, R., and Destro, R. (2003). The Fungal Metabolite Austdiol. Acta Crystallogr. C 59, o199–o201. doi:10.1107/S0108270103005031

Mándi, A., and Kurtán, T. (2019). Applications of OR/ECD/VCD to the Structure Elucidation of Natural Products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 36, 889–918. doi:10.1039/C9NP00002J

Marenich, A. V., Cramer, C. J., and Truhlar, D. G. (2009). Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 6378–6396. doi:10.1021/jp810292n

Mazzeo, G., Cimmino, A., Masi, M., Longhi, G., Maddau, L., Memo, M., et al. (2017). Importance and Difficulties in the Use of Chiroptical Methods to Assign the Absolute Configuration of Natural Products: The Case of Phytotoxic Pyrones and Furanones Produced byDiplodia Corticola. J. Nat. Prod. 80, 2406–2415. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00119

Mazzeo, G., Santoro, E., Andolfi, A., Cimmino, A., Troselj, P., Petrovic, A. G., et al. (2013). Absolute Configurations of Fungal and Plant Metabolites by Chiroptical Methods. ORD, ECD, and VCD Studies on Phyllostin, Scytolide, and Oxysporone. J. Nat. Prod. 76, 588–599. doi:10.1021/np300770s

Osmanova, N., Schultze, W., and Ayoub, N. (2010). Azaphilones: a Class of Fungal Metabolites with Diverse Biological Activities. Phytochem. Rev. 9, 315–342. doi:10.1007/s11101-010-9171-3

Pavesi, C., Flon, V., Mann, S., Leleu, S., Prado, S., and Franck, X. (2021). Biosynthesis of Azaphilones: a Review. Nat. Prod. Rep. 38, 1058–1071. doi:10.1039/d0np00080a

Powers, Z., Scharf, A., Cheng, A., Yang, F., Himmelbauer, M., Mitsuhashi, T., et al. (2019). Biomimetic Synthesis of Meroterpenoids by Dearomatization-Driven Polycyclization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 16141–16146. doi:10.1002/anie.201910710

Pracht, P., and Grimme, S. (2021). Calculation of Absolute Molecular Entropies and Heat Capacities Made Simple. Chem. Sci. 12, 6551–6568. doi:10.1039/D1SC00621E

Rassolov, V. A., Pople, J. A., Ratner, M. A., and Windus, T. L. (1998). 6-31G* Basis Set for Atoms K through Zn. J. Chem. Phys. 109, 1223–1229. doi:10.1063/1.476673

Ren, J., Ding, S.-S., Zhu, A., Cao, F., and Zhu, H.-J. (2017). Bioactive Azaphilone Derivatives from the Fungus Talaromyces aculeatus. J. Nat. Prod. 80, 2199–2203. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00032

Rodríguez-García, G., Villagómez-Guzmán, A. K., Talavera-Alemán, A., Cruz-Corona, R., Gómez-Hurtado, M. A., Cerda-García-Rojas, C. M., et al. (2019). Conformational, Configurational, and Supramolecular Studies of Podocephalol Acetate from Lasianthaea Aurea. Chirality 31, 923–933. doi:10.1002/chir.23042

Wei, W.-G., and Yao, Z.-J. (2005). Synthesis Studies toward Chloroazaphilone and Vinylogous γ-Pyridones: Two Common Natural Product Core Structures. J. Org. Chem. 70, 4585–4590. doi:10.1021/jo050414g

Xu, L.-L., Cao, F., Yang, Q., Li, W., Tian, S.-S., Zhu, H.-J., et al. (2016). Experimental and Theoretical Study of Stereochemistry for New Pseurotin A3 with an Unusual Hetero-Spirocyclic System. Tetrahedron 72, 7194–7199. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2016.09.053

Yin, G.-P., Wu, Y.-R., Yang, M.-H., Li, T.-X., Wang, X.-B., Zhou, M.-M., et al. (2017). Citrifurans A-D, Four Dimeric Aromatic Polyketides with New Carbon Skeletons from the Fungus Aspergillus Sp. Org. Lett. 19, 4058–4061. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01823

Keywords: muyocopron, endophytes, azaphilones, ECD, VCD

Citation: Yuan C, Guo Y, Wang K, Wang Z, Li L, Zhu H and Li G (2021) A Novel Azaphilone Muyophilone A From the Endophytic Fungus Muyocopron laterale 0307-2. Front. Chem. 9:734822. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.734822

Received: 01 July 2021; Accepted: 12 August 2021;

Published: 24 August 2021.

Edited by:

Essa M. Saied, Humboldt University of Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Xiaoxiao Huang, Shenyang Pharmaceutical University, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Yuan, Guo, Wang, Wang, Li, Zhu and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Longfei Li, bGlsb25nZmVpQGhidS5lZHUuY24=; Huajie Zhu, emh1aHVhamllQGhvdG1haWwuY29t; Gang Li, Z2FuZy5saUBxZHUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.