95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CASE REPORT article

Front. Allergy , 06 March 2025

Sec. Food Allergy

Volume 6 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/falgy.2025.1475023

Lisa Nuyttens1,2*

Lisa Nuyttens1,2* Liselot De Vlieger1

Liselot De Vlieger1 Toon Ieven1,3

Toon Ieven1,3 Marianne Diels2

Marianne Diels2 Tessa Bosmans4

Tessa Bosmans4 Sara Van Meerbeeck4

Sara Van Meerbeeck4 Tine Alliet2

Tine Alliet2 Toon Dominicus2

Toon Dominicus2 Ilse Hoffman4

Ilse Hoffman4 Dominique M. A. Bullens1,2

Dominique M. A. Bullens1,2

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, antigen-mediated disease characterized by eosinophilic inflammation of the esophagus. Common triggers in Europe include cow's milk, hen's egg, wheat, soy, (pea)nuts, and (shell)fish. Recent studies indicate that heated forms of cow's milk in cow's milk-induced EoE may be well tolerated. Similar to cow's milk, we present two cases of children with hen's egg-triggered pediatric EoE treated with topical steroids who remained in remission after the introduction of highly heated forms of hen's egg. The introduction of less heated forms, however, led to relapse. These two cases suggest that heated hen's egg may be well tolerated in hen's egg-induced pediatric EoE, potentially allowing for a less restrictive diet and improved quality of life. Further research is necessary to explore the potential for inducing tolerance to less heated and/or raw egg through the gradual introduction of heated egg products.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, antigen-mediated disease characterized by localized eosinophilic inflammation of the esophagus. Symptoms vary depending on the child's age, with vomiting, nausea, and feeding difficulties resulting in failure to thrive being prominent in young children. Meal-associated cough, epigastric pain, dysphagia, and even food impaction are more prevalent in older children and adolescents (1, 2). The diagnostic criteria for EoE necessitate the presence of both clinical manifestations consistent with esophageal dysfunction and histological evidence of >15 eosinophils per high-power microscopy field (HPF) in esophageal biopsies (1). Treatment strategies include proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), topical corticosteroids (tCS), or elimination diets to achieve disease remission.

In Europe, the six most common food triggers are cow's milk (CM), hen's egg (HE), wheat, soy, (pea)nuts, and (shell)fish. Empirically, avoiding one or more of these allergens can often induce remission (3). However, recent findings suggest that in EoE triggered by cow's milk, baked milk products can in some cases be tolerated (4–6). Similar to cow's milk, we present two cases of hen's egg-triggered pediatric (Ped)EoE (while under treatment with tCS) that remained in remission after the introduction of highly heated forms of egg. Unfortunately, EoE relapse occurred after the introduction of less heated forms of hen's egg, which resulted in renewed exclusion of hen's egg from the children's diet.

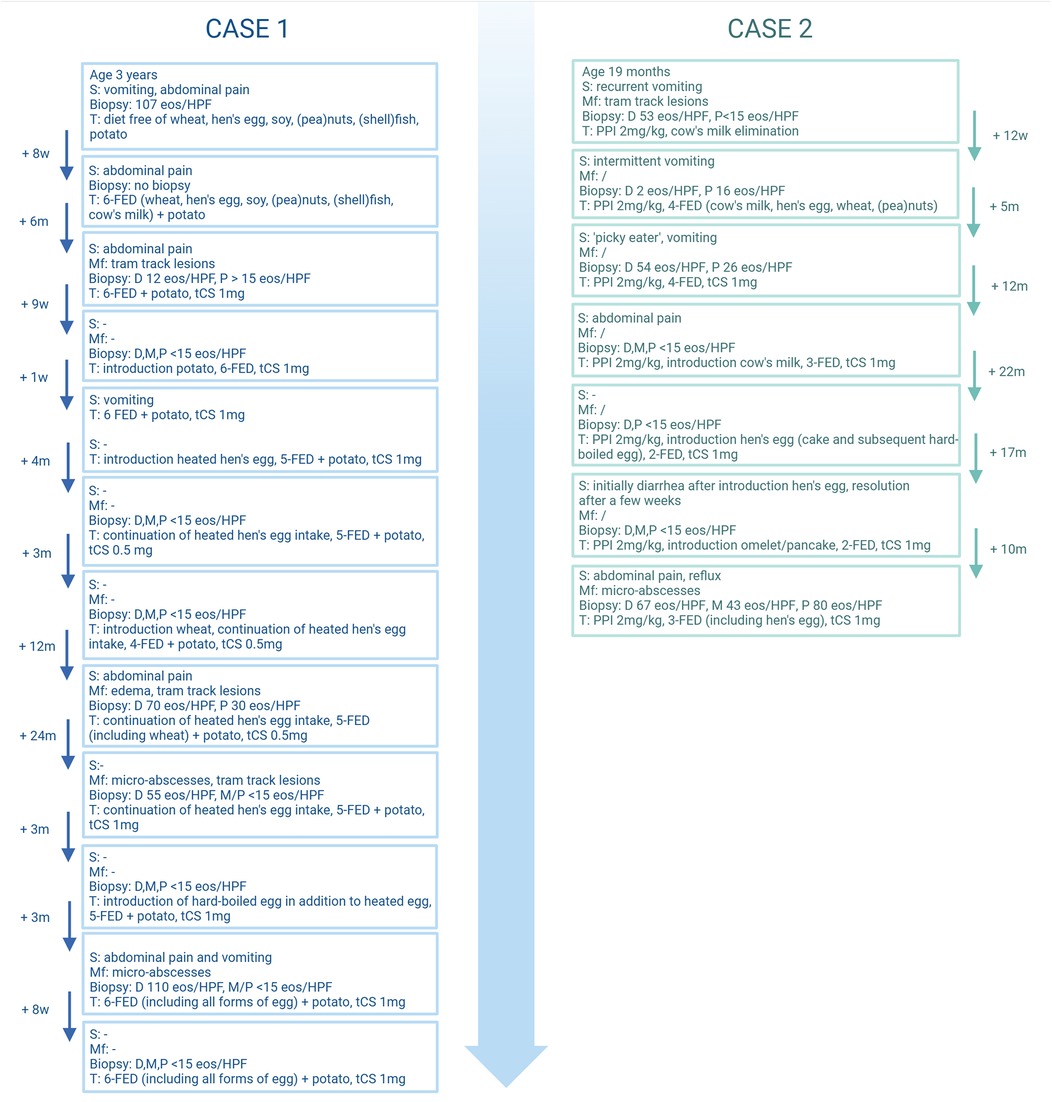

An 8-year-old boy was diagnosed with EoE at the age of 3 years due to vomiting and abdominal pain (Figure 1, Table 1). After the failure of a patient-tailored food elimination diet—including wheat, HE, soy, (pea)nuts, (shell)fish, CM, and potato [the latter based on an IgE-mediated allergy (7)]— tCS (viscous budesonide 1 mg/day, Box 1) were added to the treatment, resulting in remission. Eventually, heated HE was introduced in the form of a cake (heated 120°C, ≥30'; 1 slice 3×/week) in a rice flour-based form, adapted from the wheat-based cake recipe used in step 1 of our HE gradual introduction scheme (8) (Box 2). Persistent clinical and endoscopic remission was observed and tCS were successfully reduced to 0.5 mg/day. Subsequent wheat reintroduction to allow for the consumption of a wheat-based cake led to clinical and endoscopic relapse (70 eos/HPF). Since the re-elimination of wheat was insufficient to re-induce remission, tCS were increased to 1 mg/day with remission 12 weeks later. Hard-boiled HE (step 2 of the gradual protocol) (8) was then introduced after a successful in-hospital oral food challenge (ihOFC). After 1 week, the patient reported abdominal pain and vomiting with EoE recurrence confirmed by endoscopy (110 eos/HPF). An elimination diet excluding all forms of HE was reinstated, resulting in remission. The dose of tCS was maintained at 1 mg/day.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the two cases. w, weeks; m, months; s, symptoms; Mf, macroscopic features; D, distal eosinophilic count (eos/HPF); M, mid eosinophilic count (eos/HPF); P, proximal eosinophilic count (eos/HPF); T, therapy; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; FED, food elimination diet; tCS, topical corticosteroid. Created in BioRender. (2025) https://BioRender.com/a24e976.

A 7-year-old boy with recurrent vomiting was diagnosed with EoE at 19 months of age (Figure 1, Table 1). PPI therapy (2 mg/kg) was initiated, in part to also address concurrent reflux symptoms. After 3 months of PPI treatment combined with an IgE-directed elimination diet for CM, full endoscopic remission was not attained (16 eos/HPF) and a four-food elimination diet (FFED) including CM, HE, wheat, and (pea)nuts was undertaken, again without effect. Thus, 5 months later, after joint consultation with the parents, viscous budesonide 1 mg/day (Box 1) was added to the treatment, resulting in remission by the age of 3 years. Based on decreasing CM-specific IgE (1.60 to <0.10 kU/L), heated CM (20') was introduced, followed by progressively less heated CM and finally unheated CM after 14 months with persistent endoscopic remission. At the age of 5 years, heated HE was introduced (step 1, rice flour-based cake, Box 2) after a successful ihOFC. The cake was consumed several times per week without symptom recurrence. Furthermore, 6 months later, step 2 (hard-boiled HE) was introduced (8) and steadily increased to 1/2 portions/week (white and yolk) without symptoms. Endoscopy 8 weeks after hard-boiled HE introduction showed no recurrence. However, 4 weeks after step 3 (omelet and gluten-free pancake) (8), clinical and endoscopic recurrence was noted (80 eos/HPF), resulting in re-elimination of all forms of HE. The boy remained on PPIs and tCS (1 mg/day) throughout the gradual HE reintroduction. Afterward, an elimination diet excluding all forms of HE was reinstated; however, remission was not achieved. Remission was subsequently attained after increasing the tCS dose to 2 mg/day.

PedEoE is a heterogeneous disease that necessitates a tailored therapeutic approach. Historically, PPIs were considered the first-line treatment for EoE, with administration of tCS or dietary elimination reserved for cases in which remission was not achieved. However, the current guidelines now position PPIs, tCS, and dietary elimination as equally appropriate first-line therapeutic strategies (1). Histological remission is achieved in 59%–66% of children treated with tCS, in 30%–70% of children treated with PPIs, and in 42%–57.2% of children undergoing dietary interventions (1, 2). When dietary elimination is selected as the therapeutic approach, several strategies are available, each associated with different histological remission outcomes. Remission rates have been reported as ranging from 60.2% to 74% with a six-food elimination diet (SFED), from 56.3% to 64% with a FFED, from 30% to 67% with a one-food elimination diet (OFED), and from 52.6% to 58% with a targeted elimination diet (TED) (1, 9–11). In some cases, monotherapy may prove insufficient, necessitating a combination approach involving PPIs and/or dietary elimination and/or tCS to achieve optimal disease control (1). We have recently reviewed all PedEoE cases at our institution, highlighting the treatment difficulties in daily practice (12). Dietary elimination requires complete avoidance of the causative food. Adherence to such a diet is challenging due to the presence of allergenic protein in numerous (processed) foods. Furthermore, strict elimination diets may adversely impact both nutrition and overall quality of life (QoL), especially as more foods are restricted (8).

In the context of IgE-mediated food allergy, recent articles in the literature recommend heated allergen reintroduction, while avoiding less heated allergens during the tolerance introduction process. Indeed, emerging data show that a notable proportion (69%–83%) of children with an IgE-mediated CM allergy successfully tolerate baked CM products such as cake, whereas 63%–83% of children with IgE-mediated HE allergy tolerate baked HE products (4, 13). The allergenicity of CM and HE appears to be influenced by heating temperature and duration (8). Allowing the consumption of baked CM or HE products has the potential to improve compliance and enhance overall nutrition and QoL in children with a CM or HE allergy (4). Furthermore, we have provided evidence that consumption of heated HE may accelerate HE allergy resolution and that raw HE tolerance develops gradually through progressively less heated steps (e.g., cake, hard-boiled HE, omelet, and soft-boiled HE) (8).

Similar to what has been observed in IgE-mediated CM allergy, recent articles in the literature have shown that in a limited number of children with CM-triggered PedEoE, tolerance to baked CM was observed (4–6). In 2013, a retrospective analysis by Leung et al. showed that in a subgroup of children with CM-triggered EoE, 11/15 (73%) maintained histologic remission following the introduction of baked CM products (4). In 2019, Teoh et al. reported on a cohort of CM-triggered PedEoE with 24 children on a strict CM-free diet and 7 under a liberalized diet permitting the consumption of foods with traces of CM, including baked CM products. EoE remission was observed in 16/24 in the strict avoidance group and 2/7 in the liberalized group (5). Furthermore, González-Cervera et al. conducted a prospective study involving 18 patients with CM-triggered EoE in remission, where subjects consumed a minimum of 200 ml of sterilized CM (>100°C for 20') 2×/day over an 8-week period with 12/18 subjects maintaining endoscopic remission (6).

In contrast, Bianchi et al. reported on a 15-year-old who developed EoE during oral immunotherapy for a CM allergy and was initially permitted to eat baked CM products rather than adhering to a strict CM-free diet. Despite symptom resolution, a strict CM-free diet was ultimately required to induce histological remission (14).

Similar to the observed tolerance of heated CM in EoE, our two cases of HE-triggered PedEoE under treatment with tCS strongly suggest that heated HE may be well tolerated in HE-triggered PedEoE and that strict HE avoidance may not be universally required. In the first case, the introduction of a baked HE product (cake) resulted in the maintenance of EoE remission. Remarkably, the second case also tolerated a less heated form (hard-boiled HE) suggesting that in HE-triggered PedEoE, tolerance to less heated HE may be attainable.

The lower allergenic protein content of cake compared to a hard-boiled egg probably contributes to its reduced allergenicity. In the first case, it is plausible that reducing the amount of hard-boiled egg consumed may have been sufficient to maintain remission. However, the second case indicates that higher quantities of hard-boiled hen's egg may be tolerated in certain patients with HE-triggered PedEoE, while a less heated omelet in similar amounts was not tolerated.

Both patients received tCS therapy, which may have contributed to the maintenance of their remission. In case 1, the patient experienced a relapse following the reintroduction of wheat. tCS were reduced to 0.5 mg daily 3 months prior to this reintroduction. Unfortunately, remission did not occur after wheat was again eliminated but was only reestablished after the tCS dose was increased to 1 mg. This indicates that higher doses of tCS were needed to achieve remission. It is plausible that higher doses of tCS facilitated tolerance to the heated HE (rice flour cake), and that even this cake might not have been tolerated with a lower tCS dose. However, even at higher doses, less heated forms of hen's egg were not tolerated. In addition, it is clinically challenging to determine the exact timeframe during which therapeutic adjustments may still exert an effect (especially when multiple therapies are used concurrently). However, the literature suggests that an 8–12-week interval is generally considered sufficient to detect relapse on endoscopy (1). Complete withdrawal of tCS could, in this case, have indicated true tolerance to heated HE (cake), but this has not (yet) been performed.

In our two cases, tolerance acquisition may follow a gradual process analogous to that described in IgE-mediated HE allergy (8). This indicates that, on an individual basis, searching for the extent of HE tolerance in children with HE-triggered EoE may be worthwhile, and that further research is required to assess the extent to which complete raw HE tolerance can be achieved in children with HE-triggered EoE.

We presented two cases of successful heated HE reintroduction in children diagnosed with HE-triggered PedEoE under concomitant treatment with a tCS, while less heated forms were not tolerated, drawing parallels with the observed tolerance of baked CM products in children with CM-triggered EoE. Further research is imperative to investigate the potential for raw HE tolerance induction by introducing these HE products and to understand whether this tolerance acquisition follows a gradual process.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

LN: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LD: Writing – review & editing. TI: Writing – review & editing. MD: Writing – review & editing. TB: Writing – review & editing. SV: Writing – review & editing. TA: Writing – review & editing. TD: Writing – review & editing. IH: Writing – review & editing. DB: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Amil-Dias J, Oliva S, Papadopoulou A, Thomson M, Gutiérrez-Junquera C, Kalach N, et al. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic esophagitis in children: an update from the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2024) 79(2):394–437. doi: 10.1002/jpn3.12188

2. Oliva S, Dias JA, Rea F, Malamisura M, Espinheira MC, Papadopoulou A, et al. Characterization of eosinophilic esophagitis from the European pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis registry (pEEr) of ESPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2022) 75(3):325–33. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000003530

3. Nistel M, Andrews R, Furuta GT, Atkins D. Elimination diet or swallowed topical steroid treatment of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis: five-year outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2023) 11(8):2516–2523.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.05.036

4. Leung J, Hundal NV, Katz AJ, Shreffler WG, Yuan Q, Butterworth CA, et al. Tolerance of baked milk in patients with cow’s milk-mediated eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2013) 132(5):1215–1216.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.017

5. Teoh T, Mill C, Chan E, Zimmer P, Avinashi V. Liberalized versus strict cow’s milk elimination for the treatment of children with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. (2019) 2(2):81–5. doi: 10.1093/jcag/gwy030

6. González-Cervera J, Arias Á, Navarro P, Juárez-Tosina R, Cobo-Palacios M, Olalla JM, et al. Tolerance to sterilised cow’s milk in patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis triggered by milk. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2022) 56(6):957–67. doi: 10.1111/apt.17171

7. De Swert LF, Cadot P, Ceuppens JL. Allergy to cooked white potatoes in infants and young children: a cause of severe, chronic allergic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2002) 110(3):524–35. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.127435

8. De Vlieger L, Nuyttens L, Matton C, Diels M, Verelst S, Leus J, et al. Guided gradual egg-tolerance induction in hen’s egg allergic children tolerating baked egg: a prospective randomized trial. Front Allergy. (2022) 3:886094. doi: 10.3389/falgy.2022.886094

9. De Vlieger L, Smolders L, Nuyttens L, Verelst S, Breynaert C, Vanuytsel T, et al. A clinical perspective on the dietary therapies for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis: the gap between research and daily practice. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:677859. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.677859

10. Navarro P, Feo-Ortega S, Casabona-Francés S, Gutiérrez-Junquera C, Savarino EV, Amorena E, et al. Determinant factors for first-line treatment choice and effectiveness in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis: an analysis of the EUREOS EoE CONNECT registry. Eur J Pediatr. (2024) 183(8):3567–78. doi: 10.1007/s00431-024-05618-z

11. Mayerhofer C, Kavallar AM, Aldrian D, Lindner AK, Müller T, Vogel GF. Efficacy of elimination diets in eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2023) 21(9):2197–2210.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.01.019

12. Dominicus T, Nuyttens L, Hoffman I, Bullens DMA. Pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis: a Belgian single-center retrospective analysis reveals real-life difficulties in diagnosis and treatment. Front Allergy. (2024) 5:1478380. doi: 10.3389/falgy.2024.1478380

13. Leonard SA, Nowak-Węgrzyn AH. Baked milk and egg diets for milk and egg allergy management. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. (2016) 36(1):147–59. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2015.08.013

Keywords: PedEoE, hen’s egg-triggered EoE, heated hen’s egg, tolerance, case report

Citation: Nuyttens L, De Vlieger L, Ieven T, Diels M, Bosmans T, Van Meerbeeck S, Alliet T, Dominicus T, Hoffman I and Bullens DMA (2025) Case Report: Eosinophilic esophagitis and hen's egg tolerance—two cases, treated with topical steroids, showing remission with highly heated but not less heated hen's egg. Front. Allergy 6:1475023. doi: 10.3389/falgy.2025.1475023

Received: 2 August 2024; Accepted: 7 February 2025;

Published: 6 March 2025.

Edited by:

Lucie Mondoulet, Independent Researcher, Kremlin Bicêtre, FranceReviewed by:

Carlo Maria Rossi, San Matteo Hospital Foundation (IRCCS), ItalyCopyright: © 2025 Nuyttens, De Vlieger, Ieven, Diels, Bosmans, Van Meerbeeck, Alliet, Dominicus, Hoffman and Bullens. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lisa Nuyttens, bGlzYS5udXl0dGVuc0BrdWxldXZlbi5iZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.