- 1Department of Psychiatry, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, South Korea

- 2Department of Biomedical Informatics, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, South Korea

- 3Office of Biostatistics, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, South Korea

- 4Department of Radiology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, South Korea

- 5Department of Brain Science, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, South Korea

- 6Department of Psychiatry, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Yeouido St. Mary’s Hospital, Seoul, South Korea

Background: It has been suggested that maintaining the efficient organization of the brain’s functional connectivity (FC) supports neuroflexibility under neurogenerative stress. This study examined psychological resilience-related FC in 112 older adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Methods: Using a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) approach, we investigated reorganization of the orbitofrontal gyrus (OFG)/amygdala (AMG)/hippocampus (HP)/parahippocampal gyrus (PHG) FC according to the different levels of resilience scale.

Results: Compared with the low resilient group, the high resilient group had greater connectivity strengths between the left inferior OFG and right superior OFG (P < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected), between the right inferior OFG and left PHG (P < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected), and between the right middle OFG and left PHG (false discovery rate < 0.05).

Conclusion: Psychological resilience may be associated with enhancement of the orbitofrontal network in the elderly with MCI.

Introduction

Pathology processes of major neurocognitive disorder begin before the onset of clinical symptoms. However, many patients remain free of symptoms for a considerable period despite a significant neurodegeneration and brain volume loss The concept of brain “resilience” has emerged to explain individuals’ ability to tolerate disease-related pathology in the brain without developing clinical symptoms or signs (1). Of the many aspects of brain resilience, interest in psychological resilience and its mechanism has increased in terms of major neurocognitive disorder prevention.

To address this issue, it is required to assess functional network in brain. Network resilience derives from the efficient arrangement of connections between brain regions (2, 3). It has been suggested that maintaining the efficient organization of the brain’s functional connectivity (FC) supports neuroflexibility under neurogenerative stress (3–5). For instance, brain regions’ FCs associated with negative emotional processing and regulation, and self-referential function could be modulated and affected by antidepressant treatment (6).

More specifically, it is worth noting the relations between the orbitofrontal gyrus (OFG)-related functional network and psychological resilience (2). OFG functional activity is known to play a mediating role in subjective well-being (7). It was also reported that resilient group had greater connectivity between the OFG and amygdala (AMG) (8). Feng et al. suggested that patients with depression showed weaker functional connectivity links between the medical OFG and the parahippocampal gyrus (PHG)/medial temporal lobe, which are involved in pleasant feelings and rewards with memory systems (9).

Considering this background, the present study was designed to examine psychological resilience-related FC in the elderly with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) accompanied by depression and anxiety symptoms. Using a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) approach, we investigated linear trends of the OFG/AMG/hippocampus (HP)/PHG FC according to the level of resilience scale. In addition, given the modulatory roles of psychological resilience, we examined whether these FCs were associated with depression, anxiety, and cognitive functions.

Methods

Participants

We recruited participants over the age of 60 with MCI accompanied by depression and anxiety symptoms from the geriatric community mental health center in Suwon, Republic of Korea. One hundred twelve subjects with a mean age of 73.78 ± 5.76 years (76.80% women) were recruited. All participants were diagnosed with depressive disorder by psychiatrists a year ago at the time of study enrollment and had taken antidepressants. Inclusion criteria were (a) MCI criteria proposed by Petersen et al. (10), (b) Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) of 0.5 (11), (c) Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S) score below 4 points and not worse than 1 year ago, and (d) the use of antidepressants and anxiolytics at stable dosage for at least 6 weeks prior to study entry without any recommendation for changes in medication. Given the characteristics of older adults from geriatric community mental health center, participants might have chronic or residual affective symptoms, but they were clinically stable on affective symptoms. We excluded those who met the following criteria: (a) a history of severe psychiatric disorder (mental retardation, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other dementia); (b) a history of neurological disorder, such as brain tumor, intracranial hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, epilepsy, hydrocephalus, encephalitis, metabolic encephalopathy, or other neurologic conditions that could interfere with the study; (c) a history of significant hearing or visual impairment; and (d) a history of physical illnesses that could interfere with the study.

Psychological Resilience Measurement

The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) is a simple measurement consisting of six questions. Three questions are positive, and three are negative. Each score is given 1 to 5, and negative scores are added inversely. The higher the total score, the more psychological the resilient state. This scale was validated for Korean population (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.6, test–retest reliability = 0.62) (12, 13). In order to ensure sufficient number of neuroimaging analysis for each group, BRS was treated as a categorical variable based on tertiles. Subjects were divided into three groups based on BRS: from the lowest to 12 points was referred to as 2 group (n = 62); from 13 to 23 points was 1 group (n = 21); 24 points or more was 0 group (n = 29).

Measurement of Other Clinical Variables

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Montgomery–Asbergo Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (14, 15). The MADRS consists of 10 items of depressive symptoms in seven stages from zero to six points. Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was used to evaluate anxiety symptoms. The BAI is a self-rating tool to distinguish anxiety from depression. It has a total of 21 questions and is rated 0–3 for each question (16). Both scales indicate that depression or anxiety increases as scores increase. Cognitive functions were assessed using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), Stroop Test-color reading, Seoul Verbal Learning Test (SVLT)-delayed recall, Digit Span-backward, and CDR (17).

MRI Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Resting-state fMRI (Rs-fMRI) was performed at the beginning and end of the study at Ajou University Hospital. All MRI acquisitions were performed with a 3.0-Tesla Philips scanner (Intera Achieva, Philips, Medical Systems, Best, The Netherland) located at Ajou University Hospital. For resting-state fMRI, gradient echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence was collected (repetition time (TR) = 2,000 ms, echo time (TE) = 30 ms, flip angle = 90°, field of view (FOV) = 220 × 220 mm2, voxel size = 2.75 × 2.75 × 3 mm3, volumes = 176). Rs-fMRI data were acquired while participants lying down and resting with eyes closed, without focusing on any specific thoughts, and without sleeping. High-resolution T1-weighted images were acquired from each subject using a magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) pulse sequence (TR = 2,000 ms, TE = 4 ms, flip angle = 8°, FOV = 220 × 220 mm2, voxel size = 1 mm3).

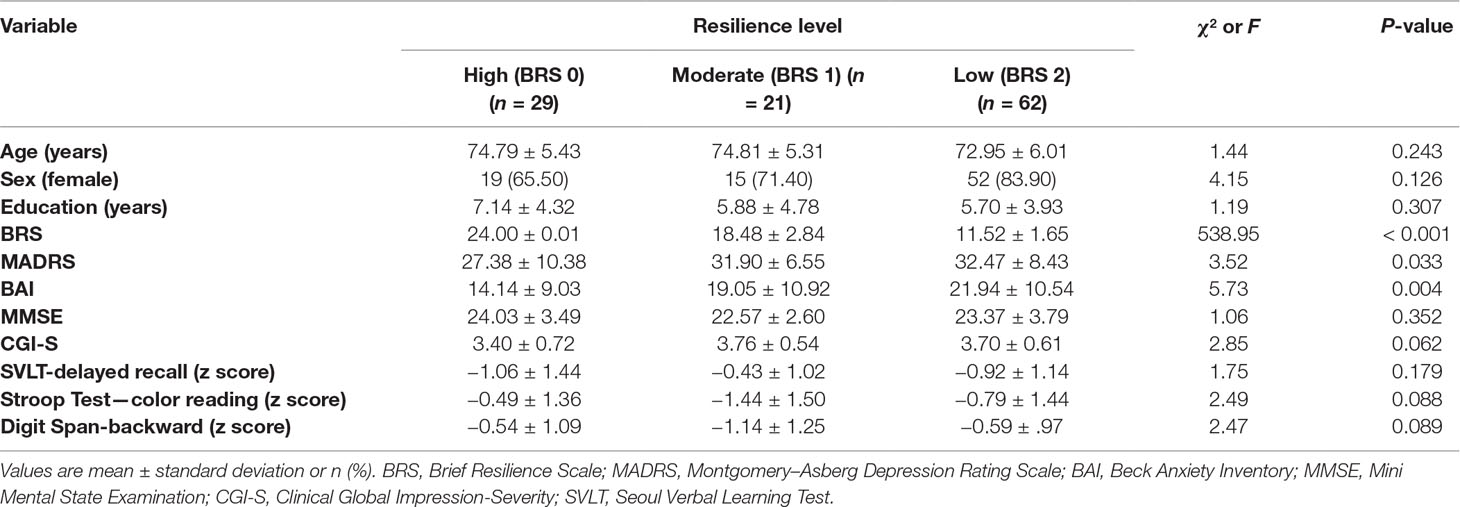

Clinical Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to explore the data. Categorical variables between resilience groups were compared using the chi-square test, while continuous variables were compared using an analysis of variance. SPSS software version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

fMRI Data and FC Analyses

Resting-state fMRI data preprocessing was conducted using statistical parametric mapping (SPM12, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/, Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK) (18). After the first five scans were discarded due to some stability issues, all EPI data were preprocessed by correcting for the delay in the acquisition time between different slices and correcting for head motion by realignment of all consecutive volumes to the first image of the session. The realigned images were co-registered to T1-weighted images, which were used to spatially normalize functional data into a template space using nonlinear transformation. We did not conduct spatial smoothing on the resting-state fMRI data to avoid inflation of local connectivity and clustering.

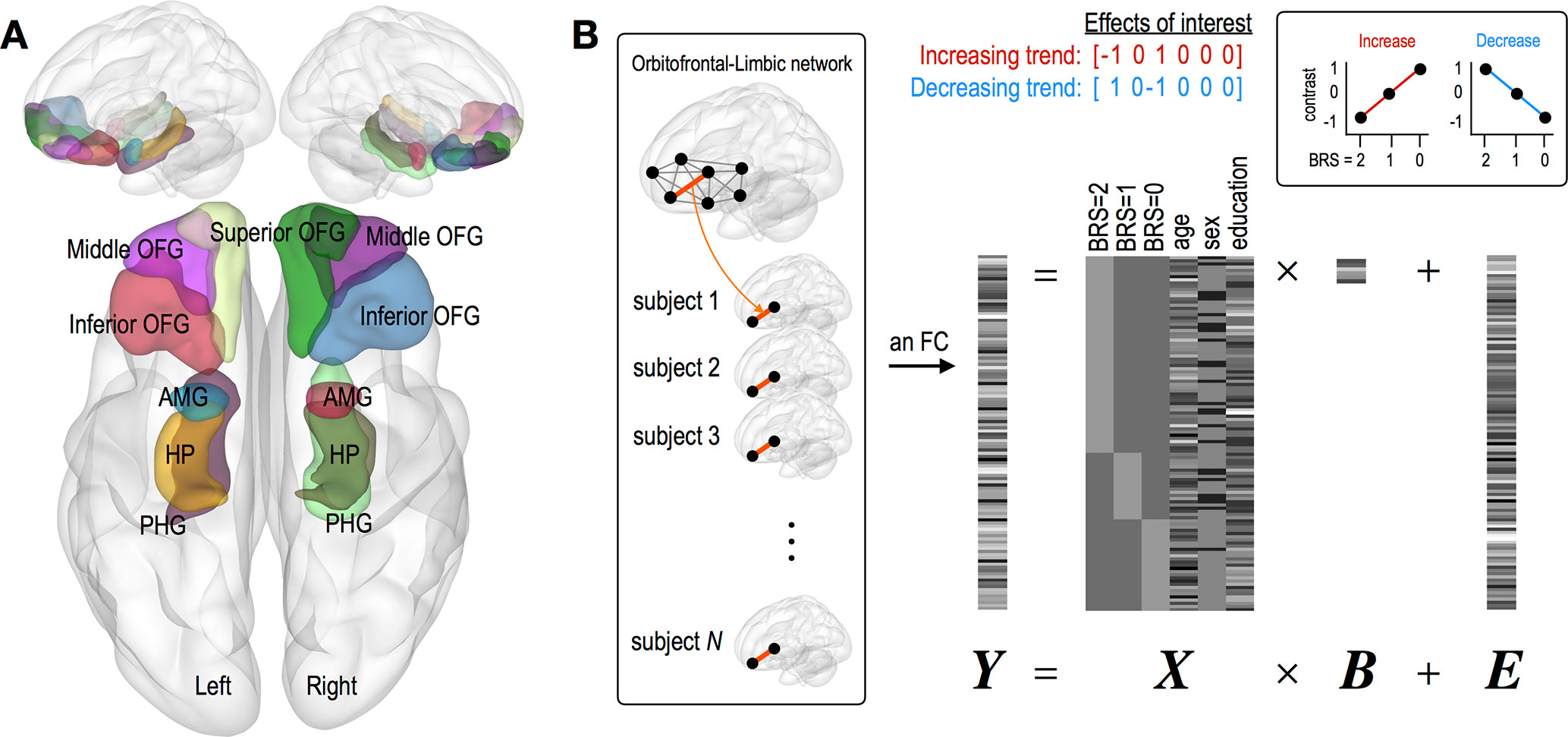

For the current study, we selected 12 regions of interest (ROIs) as the bilateral inferior/middle/superior OFG, HP, PHG, and AMG (Figure 1A), which were defined using automated anatomical labeling (AAL) atlas (19). Regional mean fMRI time series, extracted from the 12 regions, were temporally processed through (a) regressing out effects of six rigid motions and their derivatives, and three principal components of the white matter and the cerebrospinal fluid mask segmented using SPM12; (b) spike detection and despiking based on four times of the median absolute deviation; and (c) band-pass filtering (0.01–0.1 Hz) (20–23). Finally, we estimated inter-regional FCs among 12 regions using Pearson correlation coefficients, which were converted into z-scored maps with Fisher’s r-to-z transformation.

Figure 1 Description of brain regions of interest and a general linear modeling used in the current study. (A) Twelve regions of interest consist of the bilateral inferior/middle/superior OFG, HP, PHG, and AMG. (B) A general linear modeling where individual FC is tested with two contrast vectors representing linear increasing and decreasing trend separately. Variables of age, sex, and education were z-scored. Abbreviation: OFG, orbitofrontal gyrus; HP, hippocampus; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; AMG, amygdala.

This study is aimed to investigate where individual FC shows linearly increasing or decreasing trend according to BRS scales. For this purpose, we used a general linear model, in which we designed the first three regressors (BRS 2, 1, and 0 groups) indicating different groups and the next three regressors (age, sex, and education year) including nuisance covariates (Figure 1B). With this design matrix, the linear trend for each FC was examined using two contrast vectors, that is, C = [−1 0 1 0 0 0] for check increasing FC and C = [1 0 −1 0 0 0] for check decreasing FC. In order to exclude the effect of changes in brain connectivity caused by depressive and anxiety symptoms, the same analyses were conducted in groups with scores of MADRS (≥34, N = 52; 20 to 33, N = 48; ≤19, N = 12) (24) sand BAI (≥32, N = 20; 27 to 32, N = 11; 22 to 26, N = 15; ≤21, N = 66) (25).

To detect FCs showing significant trend, we applied three threshold levels of false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05, FDR < 0.2, and P < 0.05 (Bonferroni corrected) for multiple-comparison correction with the number of connections. Note that FDR control levels in the range of 0.1∼0.2 are originally known to be acceptable for multiple-comparison correction (26).

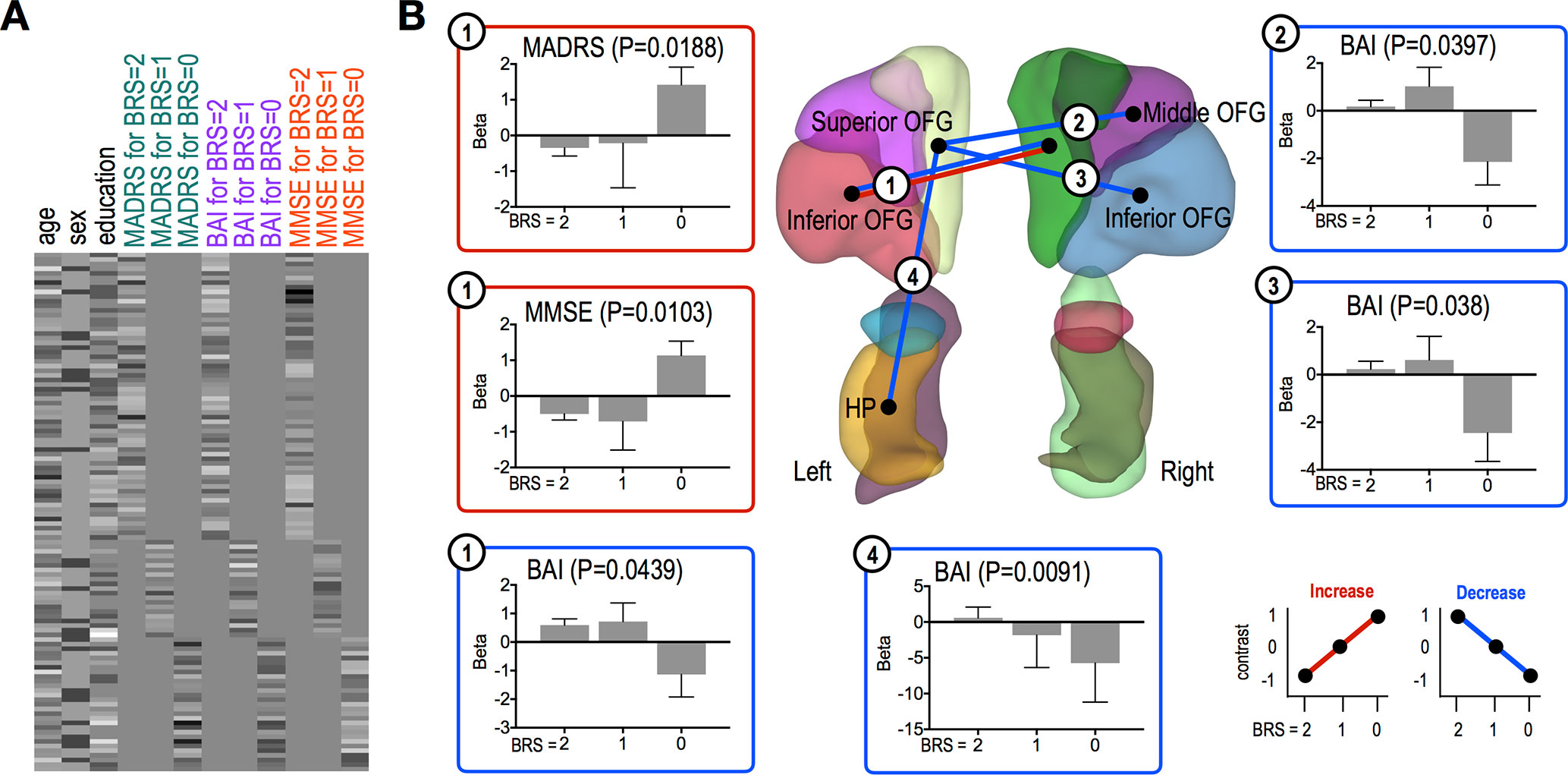

For FCs exhibiting significant linear trends, we further investigated whether such trends of connection strengths are related to MADRS, MMSE, and BAI scores or not. This study was conducted using a newly defined design matrix, where these clinical variables were separated for each group (BRS 2, 1, and 0 groups) and three nuisance covariates were included as well (Figure 3A). All analyses for resting-state fMRI were performed using MATLAB-based custom software.

Results

Clinical Characteristics of Participants

Demographic information and clinical data are summarized in Table 1. There were statistical differences in MADRS and BAI scores according to resilience groups.

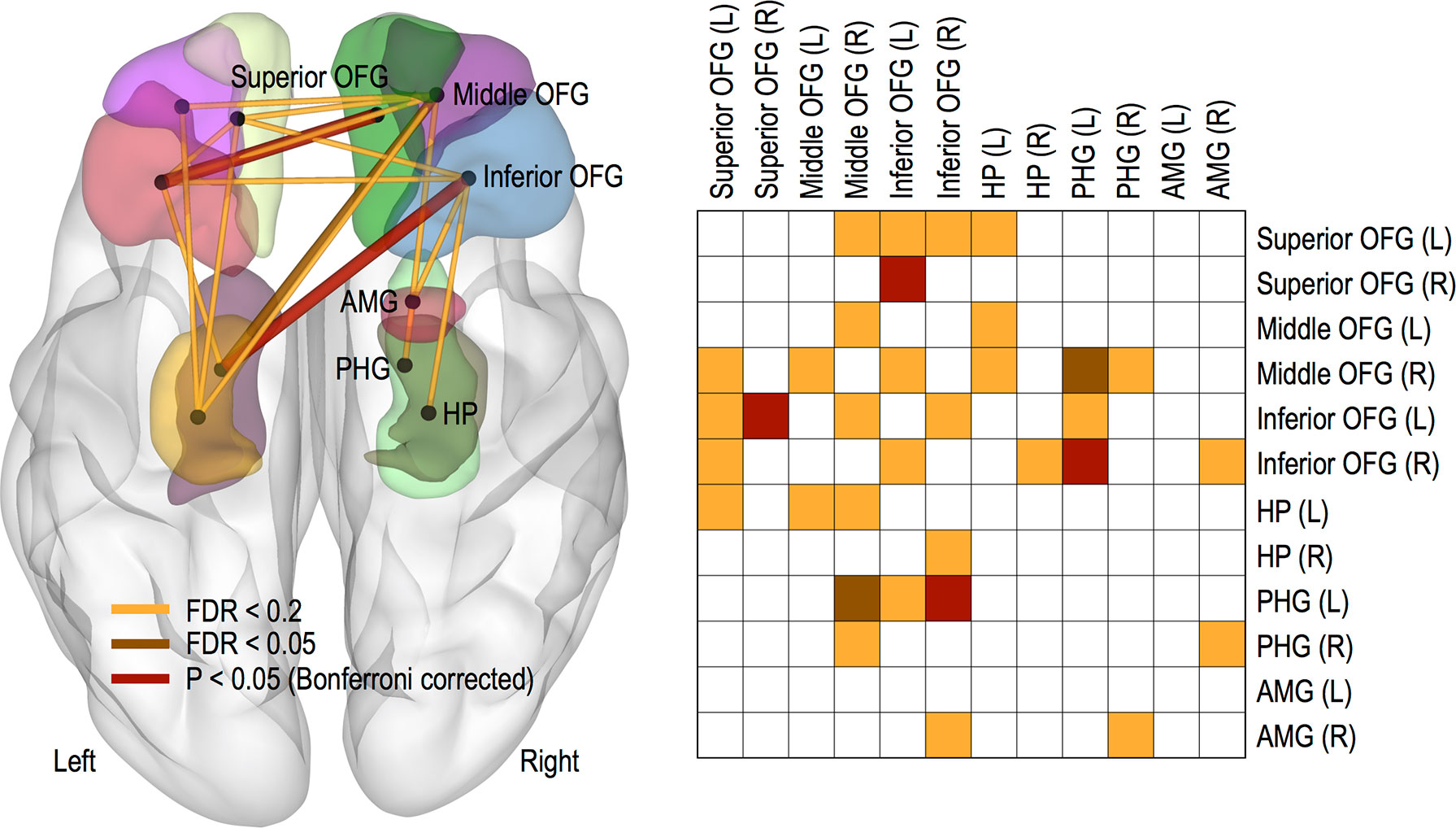

Resilience and OFG/AMG/HP/PHG FC

Compared with the low resilient group (BRS 2 group), the high resilient group (BRS 0 group) had greater FC strength, as follows: the left inferior OFG and right superior OFG (P < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected), the right inferior OFG and left PHG (P < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected), and the right middle OFG and left PHG (FDR < 0.05). However, we did not find any reduced FC strength in the high resilient group compared with the low resilient group. See Figure 2 for more details and a complete list of our results.

Figure 2 Functional connections showing significant increasing trends. Thicker links represent more significant connections and color-coded differently for three threshold levels of FDR < 0.05, FDR < 0.2, and P < 0.05 (Bonferroni corrected). Abbreviation: OFG, orbitofrontal gyrus; HP, hippocampus; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; AMG, amygdala; L, left; R, right.

Meanwhile, no changes in OFC FC were found according to the group of MADRS score. It was also observed that only FC between the left middle OFG and left HG increased in group with low BAI score (FDR < 0.2).

Different Associations Between Cognitive/Depression/Anxiety Symptoms and OFG/AMG/HP/PHG FC According to Resilience Group

MMSE and MADRS scores were significantly positively correlated with FC strength between the left inferior OFG and right superior OFG (MMSE, P = 0.0103; MADRS, P = 0.0188) in the high resilient group (Figure 3B). However, we found significant negative correlations between BAI score and connectivity strength between the left inferior OFG and right superior OFG (P = 0.0439), the left superior OFG and right middle OFG (P = 0.0397), the left inferior OFG and right superior OFG (P = 0.038), and the left superior OFG and left HP (P = 0.0091) in the high resilient group (i.e., BRS 0 group) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3 Functional connections showing significant association trends with clinical scores. (A) A design matrix used in association study with clinical scores. All variables were z-scored before separating to each group (BRS = 2, 1, and 0). (B) Functional connections showing significant trends for associations between the connections and clinical scores. In each bar plot, beta values on the vertical axis represent regression coefficients, and error bars imply standard error of the betas. Red and blue lines/boxes represent FCs and variables exhibiting significantly increasing and decreasing trends, respectively. Abbreviation: OFG, orbitofrontal gyrus; HP, hippocampus; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; AMG, amygdala.

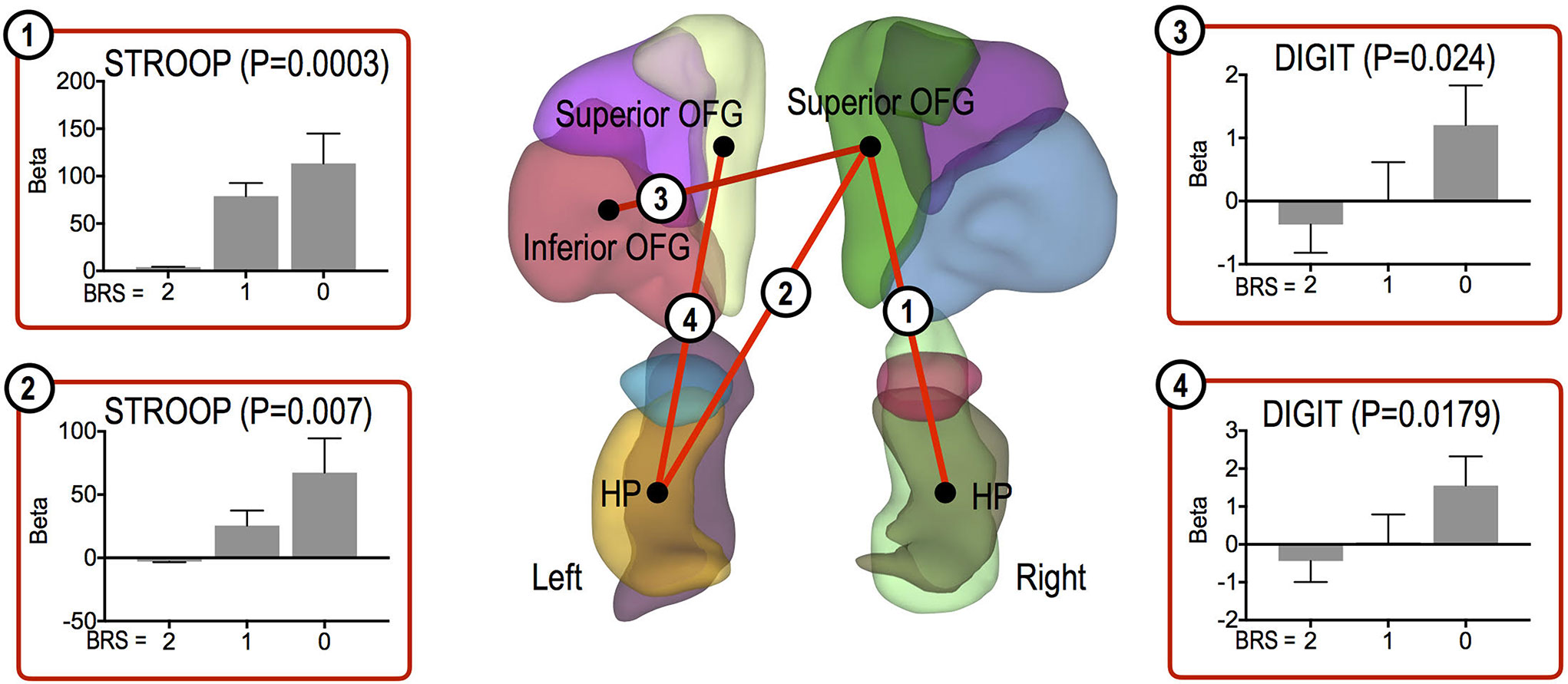

Other cognitive function tests were significantly positively correlated with FC strength in the high resilient group, as follows: the right superior OFG and left HP (Stroop Test, P = 0.007), the right superior OFG and right HP (Stroop Test, P = 0.0003), the left superior OFG and left HP (Digit Span, P = 0.0179), and the right superior OFG and left inferior OFG (Digit Span, P = 0.024) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Functional connections showing significant association trends with cognitive function test scores. Functional connections showing significantly increasing trends for associations between the connections and cognitive scores. In each bar plot, beta values on the vertical axis represent regression coefficients, and error bars imply standard error of the betas. Abbreviation: OFG, orbitofrontal gyrus; HP, hippocampus.

Discussion

The main finding is that psychological resilience may be associated with increased orbitofrontal network in the elderly with MCI. Brain circuits with greater FC strength in the high resilient group involved the OFG and PHG, which are implicated in the reward-related memory system (9). We also observed enhanced interconnectivity between OFG subregions as the resilience level increased.

Recent literature indicated that activation of the brain’s reward system could mitigate subsequent stress responses in humans, suggesting reward pathways as a mechanism for promoting psychological resilience (27). It was proposed that the connections between the medial OFG and HP/PHG provided a route for reward/emotion-related information (28). Therefore, based on our findings, it could be assumed that these FCs are involved in rewards system through positive emotional memory, which could be associated with psychological resilience under stress.

Meanwhile, enhanced interconnectivities between OFG subregions in proportion to the degree of resilience were found in this study. Previous neuroimaging studies have reported medial OFG/reward and lateral OFG/non-reward and punishment gradient consistently. Some studies also observed elevated lateral OFG activity in the low resilience state such as depression, as well as reduced interconnectivity of the medial OFG (29–31). The theory proposed that lateral OFG/non-reward system might be more easily triggered, and this triggered negative cognitive states, which in turn had positive feedback top-down effects on the OFG/non-reward system. The reward and non-reward systems were likely to operate reciprocally in facilitating the medial OFG/reward system, and they might operate by inhibiting the overactivity in the lateral OFG non-reward/punishment system (9, 31, 32). So increased resilience might be associated with reciprocal interconnectivity between the lateral OFG-related non-reward system and the medial OFG-related reward system.

In addition, given the modulatory roles of psychological resilience, we could find significant positive (i.e., MMSE, Stroop Test, and Digit Span) or negative (i.e., BAI) correlations between clinical symptoms and that resilience is related to the OFG connectivity strength in patient with MCI. Orbitofrontal network might be involved in subjective well-being and active stress coping mediated by psychological resilience (7). Chronic stress was known to have an effect on the transition from MCI to dementia, (33, 34). So maintaining the efficient organization of OFG FC supported neuroflexibility under stress, which might be the intervention strategy for preventing dementia. In actuality, our findings suggested that OFG/HP connectivity and interconnectivities between OFG subregions might be associated with executive/attentive function and anxiety symptoms.

However, contrary to expectations, MADRS scores were positively correlated with FC strength between the OFGs in the high resilient group. This was because despite the working of the resilience related to brain function, older adults with chronic or residual depressive symptoms might be included in this study. Given the characteristics of older adults from geriatric community mental health center, our subjects had relatively chronic and severe depressive symptoms compared with anxiety symptoms or cognitive impairment. Our findings on MADRS score might rather show that high stress levels were accompanied by dynamic brain functions in circuits representing the stress reaction and adaption. In this respect, individuals who failed to show such neuroflexibility in this OFG network could have a high risk of developing dementia. In fact, chronic depression has been well known as a risk factor for dementia (35).

There were several limitations. This study was conducted with a relatively small sample size and a high percentage of female participants. It has been reported that brain FC density might be different according to gender (36, 37). Furthermore, subjects with affective symptoms were included, so this aspect might need to be taken into account to interpret these results as an MCI study (31). These symptoms might interfere with both psychological resilience and cognitive impairment independently. However, independent analyses of depressive and anxiety symptom groups showed that increased OFG FC associated with resilience might be irrespective of brain connectivity related to affective symptoms.

Conclusion

We demonstrate that psychological resilience may be associated with the orbitofrontal network in the elderly with MCI. Interventions during the pre-symptomatic period of neurocognitive disorder could be effective if they promote the resilience of the brain’s intrinsically efficient arrangement of functional network connections. Understanding of the resilience system modulation of stress responding might be an exciting avenue for future research.

Data Availability

The datasets for this study will not be made publicly available because due to ethical restrictions, data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

The IRB committee of Ajou University Medical Center approved all protocols of the study (IRB-15-137).

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the study: SS, HR, HL, CH. Performed the study: SS, HK, JC, CH. Analyzed the data: BP, JS, N-RK, SS. Wrote the paper: SS, BP.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Mental Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI15C0995).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors give special thanks to Suwon Geriatric Mental Health Center for recruiting participants.

References

1. Negash S, Xie S, Davatzikos C, Clark CM, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, et al. Cognitive and functional resilience despite molecular evidence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Alzheimers Dement (2013) 9(3):e89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.009

2. Rittman DT, Borchert MR, Jones MS, van Swieten J, Borroni B, Galimberti D, et al. Functional network resilience to pathology in presymptomatic genetic frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiol Aging (2019) 77:169–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.12.009

3. Benson G, Hildebrandt A, Lange C, Schwarz C, Kobe T, Sommer W, et al. Functional connectivity in cognitive control networks mitigates the impact of white matter lesions in the elderly. Alzheimers Res Ther (2018) 10(1):109. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0434-3

4. Sinha R, Lacadie CM, Constable RT, Seo D. Dynamic neural activity during stress signals resilient coping. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2016) 113(31):8837–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600965113

5. Franzmeier N, Hartmann J, Taylor ANW, Araque-Caballero MA, Simon-Vermot L, Kambeitz-Ilankovic L, et al. The left frontal cortex supports reserve in aging by enhancing functional network efficiency. Alzheimers Res Ther (2018) 10(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0358-y

6. An J, Wang L, Li K, Zeng Y, Su Y, Jin Z, et al. Differential effects of antidepressant treatment on long-range and short-range functional connectivity strength in patients with major depressive disorder. Sci Rep (2017) 7(1):10214. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10575-9

7. Kong F, Ma X, You X, Xiang Y. The resilient brain: psychological resilience mediates the effect of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations in orbitofrontal cortex on subjective well-being in young healthy adults. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci (2018) 13(7):755–63. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsy045

8. Fischer AS, Camacho MC, Ho TC, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Gotlib IH. Neural markers of resilience in adolescent females at familial risk for major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry (2018) 75(5):493–502. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4516

9. Cheng W, Rolls ET, Qiu J, Liu W, Tang Y, Huang CC, et al. Medial reward and lateral non-reward orbitofrontal cortex circuits change in opposite directions in depression. Brain (2016) 139(Pt 12):3296–309. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww255

10. Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med (2004) 256(3):183–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x

11. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology (1993) 43(11):2412–4. doi: 10.1212/WNL.43.11.2412-a

12. Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med (2008) 15(3):194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972

13. Kim S, Min K-H. Comparison of three resilience scales and relationship between resilience and emotional characteristics. Korean J Soc Personal Psychol (2011) 25(2):223–43. doi: 10.21193/kjspp.2011.25.2.012

14. Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry (1979) 134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382

15. Ahn YM LK, Yi JS, Kang MH, Kim DH, Kim JL, Shin J, et al. A validation study of the Korean-version of the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc (2005) 44(4):466–76.

16. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol (1988) 56(6):893–7. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.56.6.893

17. Kang Y, N D. Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery (SNSB). 2nd edition Seoul: Hum Brain Res Consult Co (2003) 9–81.

18. Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Worsley KJ, Poline JP, Frith CD, Frackowiak RS. Statistical parametric maps in functional imaging: a general linear approach. Hum Brain Mapp (1994) 2(4):189–210. doi: 10.1002/hbm.460020402

19. Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage (2002) 15(1):273–89. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978

20. Weissenbacher A, Kasess C, Gerstl F, Lanzenberger R, Moser E, Windischberger C. Correlations and anticorrelations in resting-state functional connectivity MRI: a quantitative comparison of preprocessing strategies. Neuroimage (2009) 47(4):1408–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.005

21. Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage (2012) 59(3):2142–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.018

22. Thomas JB, Brier MR, Bateman RJ, Snyder AZ, Benzinger TL, Xiong C, et al. Functional connectivity in autosomal dominant and late-onset Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol (2014) 71(9):1111–22. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1654

23. Taylor JS, Rastle K, Davis MH. Interpreting response time effects in functional imaging studies. Neuroimage (2014) 99:419–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.05.073

24. Snaith RP, Harrop FM, Newby DA, Teale C. Grade scores of the Montgomery-Asberg depression and the clinical anxiety scales. Br J Psychiatry (1986) 148:596–601. doi: 10.1192/bjp.148.5.599

25. Yook SP, Kim ZS. A clinical study on the Korean version of Beck Anxiety Inventory: comparative study of patient and non-patient. Korean J Clin Psychol Aging (1997) 16:185–97.

26. Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage (2002) 15(4):870–8. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1037

27. Dutcher JM, Creswell JD. The role of brain reward pathways in stress resilience and health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev (2018) 95:559–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.10.014

28. Rolls ET. Emotion and decision-making explained: a precis. Cortex (2014) 59:185–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.01.020

29. Kringelbach ML. The human orbitofrontal cortex: linking reward to hedonic experience. Nat Rev Neurosci (2005) 6:691. doi: 10.1038/nrn1747

30. Schoenbaum G, Takahashi Y, Liu TL, McDannald MA. Does the orbitofrontal cortex signal value? Ann N Y Acad Sci (2011) 1239:87–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06210.x

31. Rolls ET. A non-reward attractor theory of depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev (2016) 68:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.007

32. Padoa-Schioppa C, Conen KE. Orbitofrontal cortex: a neural circuit for economic decisions. Neuron (2017) 96(4):736–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.031

33. Peavy GM, Jacobson MW, Salmon DP, Gamst AC, Patterson TL, Goldman S, et al. The influence of chronic stress on dementia-related diagnostic change in older adults. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord (2012) 26(3):260–6. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182389a9c

34. Katz MJ, Derby CA, Wang C, Sliwinski MJ, Ezzati A, Zimmerman ME, et al. Influence of perceived stress on incident amnestic mild cognitive impairment: results from the Einstein Aging Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord (2016) 30(2):93–8. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000125

35. Katon W, Pedersen HS, Ribe AR, Fenger-Gron M, Davydow D, Waldorff FB, et al. Effect of depression and diabetes mellitus on the risk for dementia: a national population-based cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry (2015) 72(6):612–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0082

36. Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Gender differences in brain functional connectivity density. Hum Brain Mapp (2012) 33(4):849–60. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21252

Keywords: resilience, functional connectivity, fMRI, orbitofrontal cortex, elderly

Citation: Son SJ, Park B, Choi JW, Roh HW, Kim N-R, Sin JE, Kim H, Lim HK and Hong CH (2019) Psychological Resilience Enhances the Orbitofrontal Network in the Elderly With Mild Cognitive Impairment. Front. Psychiatry 10:615. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00615

Received: 05 March 2019; Accepted: 01 August 2019;

Published: 29 August 2019.

Edited by:

Francesca Trojsi, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, ItalyReviewed by:

Sabrina Esposito, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, ItalyChantal Viscogliosi, Université de Sherbrooke, Canada

Copyright © 2019 Son, Park, Choi, Roh, Kim, Sin, Kim, Lim and Hong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hyun Kook Lim, ZHJibHVlc0BjYXRob2xpYy5hYy5rcg==; Chang Hyung Hong, YW50aWFnaW5nQGFqb3UuYWMua3I=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Sang Joon Son

Sang Joon Son Bumhee Park

Bumhee Park Jin Wook Choi4

Jin Wook Choi4 Na-Rae Kim

Na-Rae Kim Jae Eun Sin

Jae Eun Sin Hyun Kook Lim

Hyun Kook Lim