- Complex Care and Recovery Program, Forensic Division, Division of Forensic Psychiatry, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

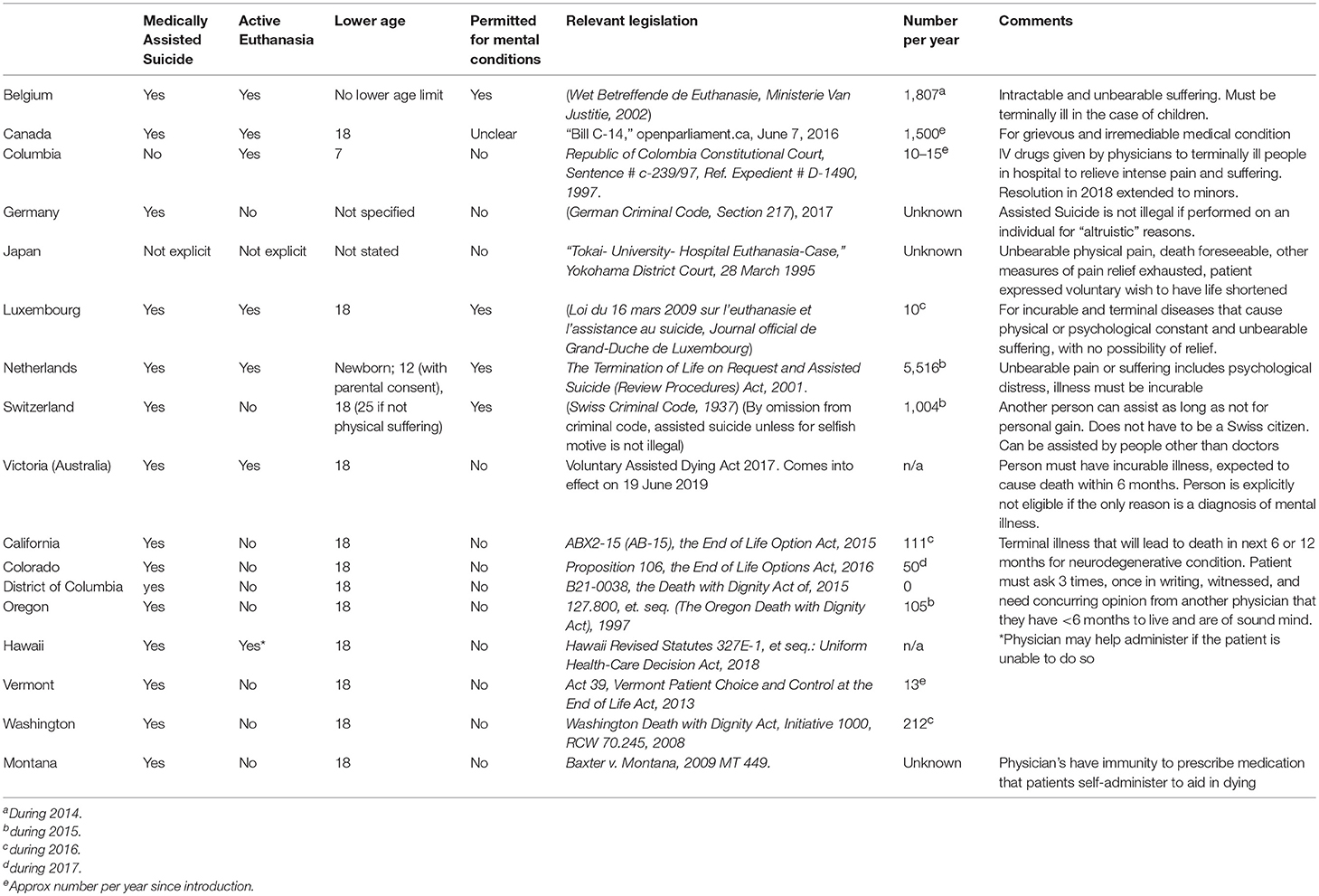

A growing number of jurisdictions explicitly exempt doctors from prosecution who assist in or directly cause the death of a person who voluntarily requests it. Medical aid in dying (MAiD) encompasses voluntary euthanasia, where the patient's life is ended by a doctor, and assisted suicide, where the doctor prescribes medication which the person self-administers at a time of their choosing. MAiD in at least one of its forms is permitted in Belgium, Canada, Columbia, Germany, Luxemburg, Netherlands, Switzerland, and seven jurisdictions of the USA (see Table 1), and there is case law, but no federal law that has permitted MAiD in Japan. Switzerland and Germany in some circumstances, allow aid in dying by people other than doctors. Active euthanasia is currently permitted in only five countries, namely Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Columbia and Canada, and recent legislation enacted permission in Hawaii.

The majority of jurisdictions where MAiD is permitted require that the individual is terminally ill, but four jurisdictions have further criteria for MAiD that include a broader range of situations in which a non-terminal disorder causes the person “intractable” or “unbearable pain” or is “a grievous and irredeemable medical condition” (1). What distinguishes the four European countries from the rest of the world (Canada's position is ambiguous in law and is currently subject to debate), is that MAiD can be accessed by people who have non-terminal conditions including mental illness as the primary or only cause of suffering.

MAiD for non-terminal disorders is permitted in Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Switzerland. The literature on its use is small but building. Although psychiatric MAID is relatively uncommon, its use appears to be rising in Belgium and the Netherlands and for a diverse range of disorders and emotional states, including personality disorders and loneliness (2, 3). Concern has been expressed regarding the oversight of the assessment of eligibility, and from the exclusion of family from the process.

Whether MAiD is acceptable and ethically justifiable is controversial, especially so when the person requesting it is not terminally ill (4–6). In addition, there are concerns whether the capacity of a person with mental disorder to request MAiD can be valid for example where depression or psychosis may cause impairment in judgement. Most tests of competence to consent to medical treatment require that the person can “weigh” the information and “appreciate” consequences of their decision (7), yet the ability to do this may be impaired by the effects of mental disorder. Indeed, there are concerns that capacity is not reliably assessed before MAiD (8). Conversely, some view that attitudes are too paternalistic in assuming that people with mental disorder are unable to consent to MAiD (9). The American Psychiatric Association [APA (10)] and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists [RANZCP (11)] have considered and rejected the use of MAiD for people who request it for mental disorder. However, the consideration of mental illness as the primary indication for MAiD is likely to be encountered in more jurisdictions.

The WPA has not formally adopted a position on MAiD as applied to psychiatric conditions. The Madrid Declaration (12) however is of relevance, as it addresses euthanasia, stating (emphasis added): Euthanasia: A physician's duty, first and foremost, is the promotion of health, the reduction of suffering, and the protection of life. The psychiatrist, among whose patients are some who are severely incapacitated and incompetent to reach an informed decision, should be particularly careful of actions that could lead to the death of those who cannot protect themselves because of their disability. The psychiatrist should be aware that the views of a patient may be distorted by mental illness such as depression. In such situations, the psychiatrist's role is to treat the illness.

The Madrid Declaration emphasizes three medical duties: to promote health, relieve suffering and protect life. A number of jurisdictions and medical bodies accept that in terminal illness, when death is imminent (see table), the relief of suffering and respect for a competent wish to die supersedes the ethical duty to protect life. However, in considering MAiD in non-terminal disorders, these duties may be seen to be in conflict with one another. The mental illness that might rarely be seen as meeting end of life care criteria is likely confined to a small group of persons with intractable anorexia nervosa for whom their mental illness can result in serious medical sequelae similar to conditions seen in end of life cases. Outside this, mental illnesses are not terminal (13). Should the suffering caused by symptoms of serious mental illness ever justify MAiD? Should other psychiatric bodies nationally or internationally develop policy positions ahead of such debates? To assist this, we wish to briefly summarize the ethical debates for and against this position.

Arguments as to Why Mental Illness Might Qualify for MAiD

Autonomy vs. Paternalism

There is little doubt that serious mental illness can be a painful, irremediable and severe illness that causes great suffering. Treatments may be only partially effective, and may result in side effects intolerable for the person. For some the prognosis for relief of symptoms is poor and, despite symptoms of their illness impairing aspects of their function, the person can still competently evaluate their treatment options and chances of their recovery. Autonomy is the fundamental right for competent adults to self-determination. Under this principle, a competent decision to end one's life in order to relieve one's own suffering, provided it is made rationally and without external influence, is justifiable. Persons with lived experience of serious mental illness may view this as their autonomous wish that physicians should respect, and failure to do so reflects continuing medical paternalism.

Equivalence With Physical Illness

To differentiate between treatment resistant medical illness and treatment resistant mental illness is a false division, and reflects stigma. Indeed, there is a small but growing literature on “palliative” mental health care that asserts the need to recognize that current treatments, acceptable to the person, will still leave the person suffering and, that as with some physical illnesses, recovery or cure is not obtainable (14).

Arguments as to Why It Should Not

Protection of Life Is Paramount

The APA and RANZCP positions on this issue emphasize that there is a profound ethical duty of a doctor that cannot be reconciled with participation in the killing of a patient. That some persons with mental illness will die by suicide is a fact that all practicing clinicians are aware, and there can be respect for the person's wish to suicide, but not for participating in or facilitating it.

Although it is accepted that mental illness may be irremediable in some cases, and doctors have a duty to relieve suffering, they have little ability to predict who will suffer unremittingly and who will recover partially or fully. There are also palliative treatments and other approaches to relieve suffering. For patients, that which seemed to be overwhelming may eventually change and become tolerable. Doctor's opinions as to the patient's prognosis and competence to make this irreversible decision may be prone to error, not based on scientific evidence, and based on the values and moral judgment of the individual the doctor.

The Slippery Slope

There is a duty for doctors to protect the most vulnerable in society. There is a risk that practices are prone to abuse, and that there is a “slippery slope” of ever more permissive practices that will fail to protect those who are most in need of protection (15). Patients must have confidence in the medical profession, and there is risk of erosion through physician's involvement in roles that may be seen to be at odds with their duty to treat illness and promote health.

Conclusion

Given the above ethical concerns and rate at which these laws are being considered and reports of some significant problems encountered in countries where it has been adopted, there is a need for psychiatric bodies internationally to consider and provide guidance about how to respond to the question, “Should MAiD extend to serious mental illness?”, and for these questions to debated and carefully considered within the broader psychiatric community.

Author Contributions

RJ and AS co-authored and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by an Academic Scholars Award to Dr. Jones from the Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, Cohen J. Attitudes and practices of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. JAMA (2016) 316:79–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8499

2. Kim SY, De Vries RG, Peteet JR. Euthanasia and assisted suicide of patients with psychiatric disorders in the Netherlands 2011 to 2014. JAMA Psychiatry (2016) 73:362–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2887

3. Thienpont L, Verhofstadt M, Van Loon T, Distelmans W, Audenaert K, De Deyn PP. Euthanasia requests, procedures and outcomes for 100 Belgian patients suffering from psychiatric disorders: a retrospective, descriptive study. BMJ Open (2015) 5:e007454. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007454

4. Vandenberghe J. Physician-assisted suicide and psychiatric illness. N Eng J Med. (2018) 378:885–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1714496

5. Miller FG, Appelbaum PS. Physician-assisted death for psychiatric patients - misguided public policy. N Eng J Med. (2018) 378:883–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1709024

6. Appelbaum PS. Physician-assisted death in psychiatry. World Psychiatry (2018) 17:145–6. doi: 10.1002/wps.20548

7. Grisso T, Appelbaum P. Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment: A Guide for Physicians and Other Health Care Professionals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (1998).

8. Doernberg SN, Peteet JR, Kim SY. Capacity evaluations of psychiatric patients requesting assisted death in the Netherlands. Psychosomatics (2016) 57:556–65. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2016.06.005

9. Shaw D, Trachsel M, Elger B. Assessment of decision-making capacity in patients requesting assisted suicide. Br J Psychiatry (2018) 213:393–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.81

10. American Psychiatric Association. Position Statement on Medical Euthanasia 2016. Available online at: http://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/About-APA/Organization-Documents-Policies/Policies/Position-2016-Medical-Euthanasia.pdf

11. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Position Statement 67: Physician Assisted Suicide. 2016. Available online at: https://www.ranzcp.org/Files/Resources/College_Statements/Position_Statements/PS-67-Physician-Assisted-Suicide-Feb-2016.aspx

12. World, Psychiatric Association,. Madrid Declaration on Ethical Standards for Psychiatric Practice. Available online at: http://www.wpanet.org/detail.php?section_id=5&content_id=48

13. Simpson AIF. Medical assistance in dying and mental health: a legal, ethical, and clinical analysis. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatrie (2018) 63:80–4. doi: 10.1177/0706743717746662

14. Dembo J, Schuklenk U, Reggler J. For their own good: a response to popular arguments against permitting Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) where mental illness is the sole underlying condition. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatrie (2018) 63:451–6. doi: 10.1177/0706743718766055

Keywords: euthanasia, medically assisted suicide, medical assistance in dying, psychiatry, legislation, Madrid Declaration

Citation: Jones RM and Simpson AIF (2018) Medical Assistance in Dying: Challenges for Psychiatry. Front. Psychiatry 9:678. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00678

Received: 12 July 2018; Accepted: 23 November 2018;

Published: 10 December 2018.

Edited by:

Matthias Jaeger, Psychiatrie Baselland, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Dirk Richter, Universitäre Psychiatrische Dienste Bern, SwitzerlandAikaterini Arvaniti, Democritus University of Thrace, Greece

Paul Hoff, Psychiatrische Klinik der Universität Zürich, Switzerland

Copyright © 2018 Jones and Simpson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Roland M. Jones, cm9sYW5kLmpvbmVzQGNhbWguY2E=

Roland M. Jones

Roland M. Jones Alexander I. F. Simpson

Alexander I. F. Simpson