- 1Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, Department of Cardiac, Thoracic, Vascular Sciences and Public Health, University of Padua, Padua, Italy

- 2Department of Philosophy, Sociology, Education and Applied Psychology, University of Padua, Padua, Italy

- 3Department of Human Science (Communication, Training, Psychology), LUMSA University, Rome, Italy

Organizational research has highlighted the crucial role of supervisors in promoting employee well-being and performance. According to the motivational approach, supervisors positively influence employees’ outcomes by enhancing their positive feelings. In this study, we examine how positive supervisor behaviors may improve employee performance through the serial mediation of workplace spirituality and work engagement. Data were collected from 330 Italian employees. Results showed that supervisor integrity and responsible behaviors have a positive effect on employee performance directly; moreover, positive supervisor behaviors influence performance indirectly, through both the partial mediation of work engagement and the serial mediation of workplace spirituality and work engagement. The present study highlighted that supervisors should behave responsively and honestly to trigger a virtuous motivational process in their employees, which leads to boost their performance. The practical implications of these findings are discussed.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, supervisor behaviors have been recognized as a key factor for promoting employee performance (Braun et al., 2013; Barrick et al., 2015; Rana and Javed, 2019; Shin and Hur, 2020) and well-being (Liu et al., 2010; Benevene et al., 2018; He et al., 2019). Within the field of positive psychology (Seligman, 1998; Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), several much evidence pointed out the crucial role of positive organizational behaviors, starting from positive leadership styles (Luthans, 2002a, b; Avolio et al., 2004). For instance, the transformational leadership style has been studied extensively: results showed its positive relationships with improved performance and reduced stress (Dvir et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2011; Salem, 2015; Ng, 2017). Moreover, a growing body of evidence showed positive relationships between the authentic leadership style and several positive organizational outcomes, such as commitment, job satisfaction, creativity, innovativeness, and performance (Khan, 2010; Azanza et al., 2013; Müceldili et al., 2013; Wong and Laschinger, 2013; Wang et al., 2014; Baek et al., 2019). An authentic leadership style is a positive approach to organizational leadership, characterized by self-awareness, relational transparency, authentic behaviors, and positive moral perspective (Avolio and Gardner, 2005; Walumbwa et al., 2008). Authentic leaders are confident, hopeful, optimistic, resilient, genuine, reliable, motivated by personal convictions, moral/ethical, future-oriented, and aware of their own and others’ values (Gardner et al., 2011). Much research suggests that authentic leaders encourage employees’ development, reduce burnout risk, promote a positive ethical climate, and improve work engagement (Hassan and Ahmed, 2011; Laschinger and Fida, 2014). Moreover, some evidence showed the positive effect of supervisor integrity and authentic leadership on performance (Leroy et al., 2012; Tak et al., 2019). Integrity, emotion management, respect, and a responsible and considerate approach are crucial competencies to manage employees positively and to become positive supervisors (Yarker et al., 2008; Dal Corso et al., 2019b). These competencies are part of a behavioral framework designed to help supervisors in both reducing stress and promoting organizational well-being. This framework revolves around a set of positive macro competencies, given the need for an approach that defines in a practical way the skills to be developed and improved by supervisors. The focus on behaviors has several strengths: for example, behaviors are observable, learnable, and changeable quite easily; it also guides HR management in developing effective interventions. The framework is mainly linked to the transformational, ethical, and authentic models of leadership (Donaldson-Feilder et al., 2011), because the difference between supervisors and leaders is subtle: only supervisors hold a responsibility toward both tasks and other people’s work; the direct link to this strategic responsibility is the essence of the managerial dimension given that leadership does not necessarily entail this concept (Drucker, 2008; De Carlo et al., 2016a).

The literature suggests that several variables are crucial in influencing the relationship between supervisor behaviors and employee performance. Among the main core mechanisms identified in the literature (Ng, 2017), the motivational one is particularly interesting for the present study. According to it, supervisors can stimulate employees to improve their performance by enhancing their feelings of vigor, competence, absorption, and dedication to work. Therefore, this approach suggests that the relationship between positive supervisor behaviors and employee performance may be mediated by positive work feelings, such as the fulfillment of one’s needs or work engagement (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004; Salanova et al., 2011; Kovjanic et al., 2013).

Over the last few years, workplace spirituality has gained increasing attention in the organizational research field. The literature conceived workplace spirituality as a multidimensional construct and a positive means to improve employees’ well-being (McKee et al., 2011; Kinjerski, 2013). It has beneficial effects across various kinds of organizations, currently influenced by technological innovations (De Carlo et al., 2020) and through environment sharing (Ivaldi and Scaratti, 2019). Spiritual workplaces encourage employees’ sense of community, recognize their spiritual-mystical needs, foster feelings of engaging in meaningful work, and support integrity, respect, responsibility, and personal growth (see Garcia-Zamor, 2003; Giacalone and Jurkiewicz, 2003; Duchon and Plowman, 2005; Badrinarayanan and Madhavaram, 2008; Kinjerski, 2013). Empirical support was found for workplace spirituality as a predictor of several positive organizational outcomes (van der Walt and de Klerk, 2014), such as performance (De Carlo et al., 2016b; Do, 2018; Rahman et al., 2019). Workplace spirituality was found to be positively associated with work engagement, as well (Saks, 2011; Roof, 2015; Gupta and Mikkilineni, 2018; Van Wingerden and Van der Stoep, 2018). Both workplace spirituality and work engagement refer to a sense of entirety and completeness: workplace spirituality posits that employees express their whole inner self at work (Milliman et al., 2003; Duchon and Plowman, 2005), work engagement requests the simultaneous investment of the physical, cognitive, and emotional self (Kahn, 1990). Despite the similarities, much evidence found workplace spirituality to be an antecedent of work engagement (Kolodinsky et al., 2008; Ahmad and Omar, 2015; Petchsawang and McLean, 2017; Hunsaker, 2018; van der Walt, 2018; Hua et al., 2019; Lizano et al., 2019; Baker and Lee, 2020). The more organizations are oriented toward the fulfillment of spiritual needs, the more easily they can engage employees in work (Jurkiewicz and Giacalone, 2004). In particular, Saks (2011) stated that the connection between the two constructs is due to workplace spirituality ability to create the psychological conditions that, according to Kahn (1990), are needed to increase work engagement—namely, psychological meaningfulness, psychological safety, and psychological availability. Bickerton et al. (2015) analyzed the connection between workplace spirituality and work engagement in the JD-R model and found that spiritual resources had a significant motivational effect: mystical experience at work increased employees’ work engagement and reduced their intention to quit the organization.

Work engagement is a positive state of vigor, dedication, and absorption of employees with their work (Bakker and Demerouti, 2008). Engaged employees have a sense of energetic and effective connection with their activities, feel competent and effective on their job (Schaufeli et al., 2006), and experience a fulfilling state of mind (Bakker et al., 2008). Work engagement has been largely studied in the framework of positive organizational psychology. Positive associations were found with several positive outcomes, such as improved performance (e.g., Christian et al., 2011; Bakker et al., 2012; Reijseger et al., 2017), greater organizational commitment (e.g., Hakanen et al., 2008; Saks, 2011; Qodariah Akbar and Mauluddin, 2019), increased levels of well-being (e.g., Schaufeli et al., 2008; Shimazu and Schaufeli, 2009; Joo and Lee, 2017), and reduced intention to quit (e.g., Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004; Li et al., 2019). Much research, in addition, devoted efforts to identify antecedents of work engagement. Results highlighted the positive effect of job resources, such as autonomy, value congruence, social support from colleagues and supervisors, trusting relationships with supervisors, and workplace spirituality (Bakker and Demerouti, 2008; Rich et al., 2010; Saks, 2011; Falco et al., 2013; Barbieri et al., 2014; Roof, 2015; Gill et al., 2019).

This study aims to analyze how positive supervisor behaviors are linked to employee performance. Specifically, we aim to examine the serial mediation of workplace spirituality and work engagement in the relationship between positive supervisor behaviors and employee performance.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedure

A total of 330 completed questionnaires were collected (males = 237; mean age = 39.61, SD = 9.06) from five different Italian companies (23.9% banking; 1.8% large-scale retailing; 32.1% oil and gas; 15.5% chemical, industrial, and pharmaceutical; 26.7% metalworking). The majority of participants were white collars (78.5%; blue collars 20%; missing 1.5%) with a seniority in their company lower than ten years (58.5%; over 10 years 39.7%; missing 1.8%). A questionnaire consisting of three standardized scales was administered to measure positive supervisor behaviors, workplace spirituality, and work engagement. The questionnaires were administered on-site and they were filled out in pencil by the participants. A researcher, present in the room during the administration, collected the questionnaires. Participants were asked to rate their performance. Our study was conducted following the recommendations of the Ethics Committee of Psychology Research of the University of Padua. All participants were duly informed that participation was anonymous and voluntary.

Measures

Positive supervisor behaviors were assessed through the first scale of the Stress Management Competency Indicator Tool (SMCIT; Donaldson-Feilder et al., 2009). The scale includes 17 items scored on a five-point scale (from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) and evaluates three dimensions: integrity (e.g., “This Manager is honest”), emotions management (e.g., “This Manager doesn’t pass on their stress to the team”), and considerate approach (e.g., “The deadlines this Manager creates are realistic”). High scores in this scale describe respectful and honest supervisors with clear values. These supervisors support employees, manage them thoughtfully, and behave consistently and calmly, as good role models. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is 0.89.

Workplace spirituality was evaluated through the Spirit at Work Scale (SAWS; Kinjerski, 2013). The instrument includes 18 items scored on a six-point scale (from “completely untrue” to “completely true”). The SAWS evaluates the experience of workplace spirituality through four subscales: engaging work (e.g., “I am passionate about my work”), sense of community (e.g., “I feel like I am part of ‘a community’ at work”), spiritual connection (e.g., “My spiritual beliefs play an important role in everyday decisions that I make at work”), and mystical experience (e.g., “I experience moments at work where everything is blissful”). The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is 0.91.

Work engagement was assessed by the shortened Italian version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9; Balducci et al., 2010; see also Schaufeli et al., 2006). The instrument comprises three subscales, with three items each: vigor (e.g., item “At my job, I feel strong and vigorous”), dedication (e.g., item “My job inspires me”), and absorption (e.g., item “I feel happy when I am working intensely”). The items were rated on a six-point scale (from “never” to “always”). The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is 0.91.

Employee performance was evaluated through two self-report items. Specifically, participants were asked to evaluate their performance on a 10-point scale (from “low” to “high”) and to rate the work objectives achieved in the last year through a percentage (from 0 to 100%). The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is 0.69.

Statistical Analyses

We examined the relationships between positive supervisor behaviors, workplace spirituality, work engagement, and employee performance through structural equation modeling. In the tested model, positive supervisor behaviors were the predictor, workplace spirituality was the first-order mediator, work engagement was the second-order mediator, and employee performance was the criterion variable. Three to four parcels were computed to define the constructs (parcels were created by averaging items of the subscales of the different constructs), while a two-item indicator was employed to measure employee performance. The analyses were run using the Mplus7 package (Muthén and Muthén, 2012) and the maximum likelihood as an estimator. In the mediation model, all paths were estimated and the 95% bootstrap confidence interval (5000 bootstrap samples) was used to test the significance of the indirect effect.

To evaluate the model, several goodness-of-fit indices were used: χ2, comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR; Bentler, 1995), and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne and Cudeck, 1993). Concerning χ2, a solution fits the data well when the value is non-significant (p ≥ 0.05). Because this statistic is sensitive to the sample size, inspection of the other fit indices is recommended. In particular, a good fit is supported by CFI indices close to 0.95 (0.90–0.95 for a reasonable fit), SRMR values less than 0.08, and RMSEA smaller than 0.06 (0.06–0.08 for a reasonable fit; Hu and Bentler, 1999; Marsh et al., 2004; Brown, 2006).

Results

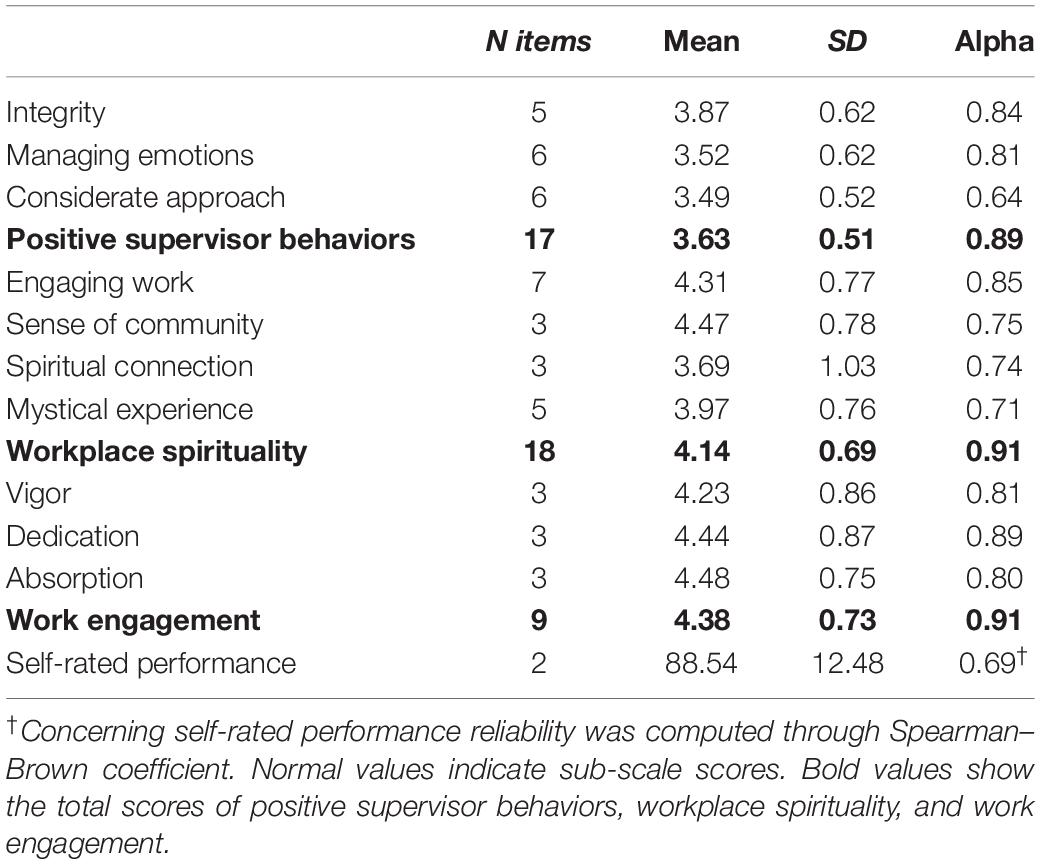

Descriptive statistics and reliability indices of all scales are reported in Table 1.

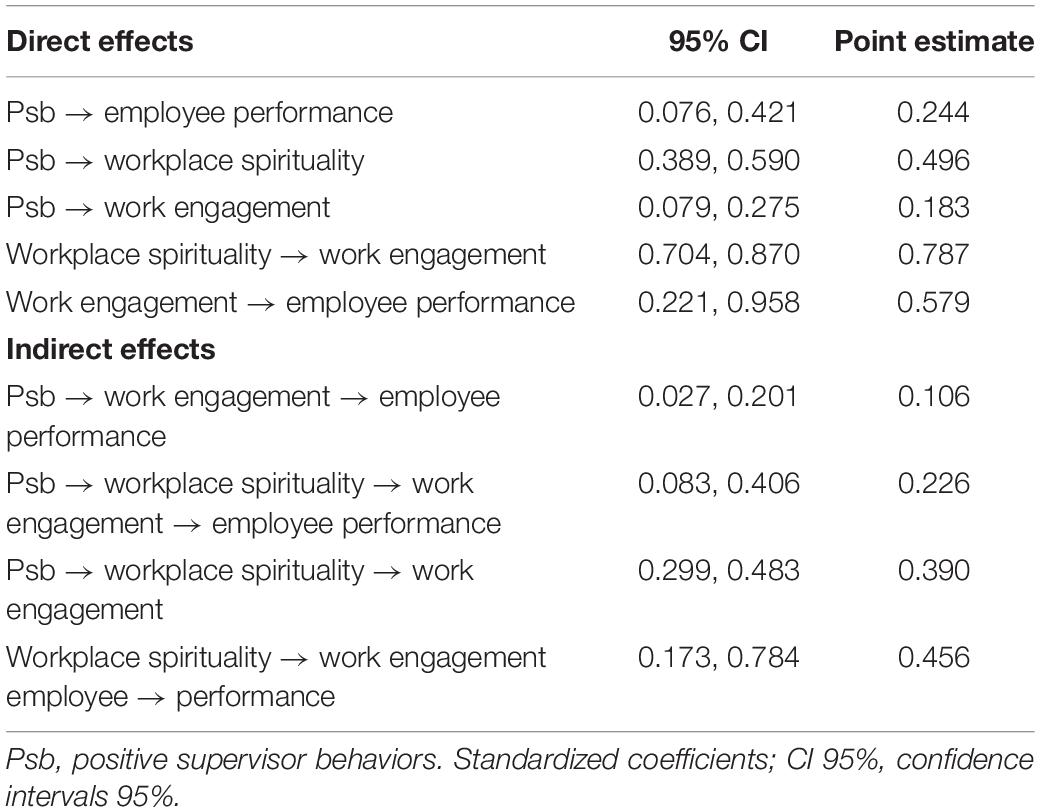

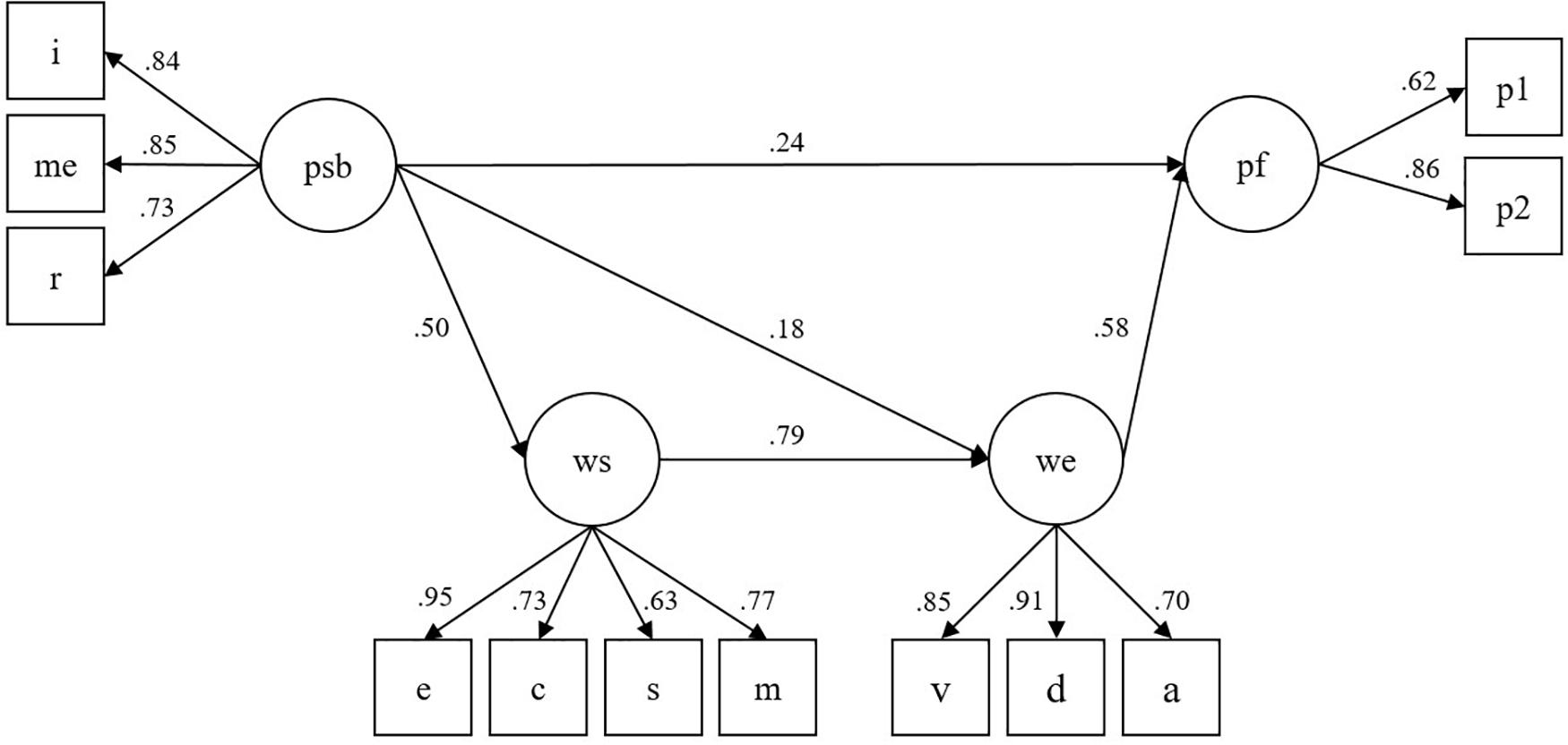

The model tested is represented in Figure 1 and fits the data well: χ2(48) = 94.684, p ≅ 0.000; RMSEA = 0.054, CFI = 0.979; SRMR = 0.032. Results show a direct positive effect of positive supervisor behaviors on employee performance (95% CI = 0.076, 0.421) and two indirect effects mediated by workplace spirituality and work engagement (Table 2). Specifically, positive supervisor behaviors have a positive effect on work engagement (95% CI = 0.079, 0.275), which partially mediates the effect of positive supervisor behaviors on employee performance (95% CI = 0.027, 0.201). In addition, positive supervisor behaviors have a positive effect on workplace spirituality (95% CI = 0.389, 0.590), which partially mediates the effect of positive supervisor behaviors on work engagement (95% CI = 0.299, 0.483). Positive supervisor behaviors, therefore, have positive effects on employee performance through the partial mediation of work engagement (95% CI = 0.027, 0.201) and through the serial mediation of both workplace spirituality and work engagement (95% CI = 0.083, 0.406). The relation between workplace spirituality and employee performance is totally mediated by work engagement (95% CI = 0.173, 0.784).

Figure 1. The model tested. Note. Psb, positive supervisor behaviors (parcels: i = integrity, me = managing emotions, r = considerate approach); ws, workplace spirituality (parcels: e = engaging work, c = sense of community, s = spiritual connection, m = mystical experience); we, work engagement (parcels: v = vigor; d = dedication; a = absorption); pf, employee performance (p1, p2 = items-indicator). Standardized coefficients; all values are significant p ≤ 0.01 (only significant paths are represented).

Discussion

The present study aimed to analyze how positive supervisor behaviors were linked to employee performance. Specifically, we examined the mediation role of workplace spirituality and work engagement in the relationship between positive supervisor behaviors and employee performance.

The literature suggested that positive supervisors positively influenced employees’ outcomes through a motivational process mediated by employees’ positive feelings, such as the fulfillment of one’s needs and work engagement (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004; Salanova et al., 2011; Kovjanic et al., 2013; Ng, 2017; Dal Corso et al., 2019a). The results of the present study supported this perspective.

We found that positive supervisor behaviors had a direct positive effect on workplace spirituality, work engagement, and performance. Workplace spirituality is a multifaceted construct, which has only recently been introduced in the organizational research field. Research conducted in the last few years showed its positive effects on several positive outcomes, such as reduced burnout, increased well-being, and job satisfaction (McKee et al., 2011; Kinjerski, 2013; van der Walt and de Klerk, 2014). In addition, several studies observed a positive effect of workplace spirituality on employee performance (Garcia-Zamor, 2003; Giacalone and Jurkiewicz, 2003). In the present study, workplace spirituality partially mediated the relationship between positive supervisor behaviors and work engagement, which, in turn, totally mediated the relationship between workplace spirituality and performance, confirming the crucial role of work engagement in promoting positive outcomes. Indeed, work engagement is a positive work-related motivational state associated with other favorable outcomes, such as organizational commitment, employee well-being, and reduced stress (Saks, 2006; Hakanen et al., 2008; Schaufeli et al., 2008; Shimazu and Schaufeli, 2009).

Moreover, our results showed that positive supervisor behaviors had positive indirect effects on employee performance through both the partial mediation of work engagement and the serial mediation of workplace spirituality and work engagement, respectively. In particular, supervisor integrity and ability in managing emotions was found to be crucial to increase work engagement, thus leading to enhanced employee performance. At the same time, workplace spirituality contributed to explain the relationship between positive supervisor behaviors and work engagement. Because work engagement mediated the relationship between positive supervisor behaviors and employee performance, and workplace spirituality mediated the relationship between positive supervisor behaviors and work engagement, the serial mediation is confirmed. Therefore, workplace spirituality and work engagement are important links in the chain that contributes to explain the relationship between positive supervisor behaviors and employee performance.

Although our results are interesting, some limitations can be recognized, for example, the cross-sectional nature of the study. Future studies should try to extend our findings using a longitudinal design. Furthermore, studies with wider and different samples could be useful to circumscribe the possible effects of the specific sample of this study. Indeed, our sample of mainly white collars could have increased the effect of workplace spirituality and work engagement because of their education level and the inherent nature of their job. Besides that, the fact that the participants were completely from Italian companies can make the spirituality effect influenced by the Italian history and culture. Finally, our sample of female workers is still smaller than males, and that should be expanded in the future. In addition, future research should attempt to replicate our results using not only self-report measures but also other data sources (Falco et al., 2012, 2018). Moreover, future studies are needed to understand how positive supervisor behaviors may be trained to foster workplace spirituality and, consequently, its positive outcomes. Finally, future research could investigate the association between positive supervisor behaviors and workplace spirituality on the one hand and negative forms of heavy work investment (e.g., workaholism; Falco et al., 2017) on the other.

Practical Implications

The findings of the present study suggest that supervisors have a great responsibility toward employees’ well-being because they shape the working environment through their daily behaviors (Girardi et al., 2015). Top management should help supervisors to identify misbehaviors by suggesting better alternative conduct. At the same time, organizations should plan adequate training activities to improve supervisors’ positive competencies (Ivaldi and Scaratti, 2015) and set positive examples on which all supervisors can model their behaviors. The importance of involving the entire organization is decisive in creating a positive organizational culture. The role of organizations is also to emphasize the significance of positive management, specifying that it is not an additional burden to be met, but a set of competencies and attitudes to be valued and integrated into the day-to-day management of employees and tasks. Once this shared awareness has been created, positive supervisors will fulfill employees’ spiritual needs and foster the motivational process that enhances their performance.

Conclusion

The present findings highlight the importance of positive supervisor behaviors in promoting employee well-being. Moreover, they support the crucial role of work engagement in the relationship between positive supervisor behaviors and employee performance, and provide a new contribution by taking into account the role of workplace spirituality.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

AD developed the research project, with the contribution of LD and AF. AD and LD reviewed the literature, with the contribution of AF and FC. FC and DC prepared the dataset and carried out the data analysis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the University of Padua Research Funds.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Ahmad, A., and Omar, Z. (2015). Improving organizational citizenship behavior through spirituality and work engagement. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 12, 200–207. doi: 10.3844/ajassp.2015.200.207

Avolio, B. J., and Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadership Quart. 16, 315–338. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.001

Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Walumbwa, F. O., Luthans, F., and May, D. R. (2004). Unlocking the mask: a look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. Leadership Quart. 15, 801–823. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.09.003

Azanza, G., Moriano, J. A., and Molero, F. (2013). Authentic leadership and organizational culture as drivers of employees’ job satisfaction. Rev. Psicol. Trabajo Organ. 29, 45–50. doi: 10.5093/tr2013a7

Badrinarayanan, V., and Madhavaram, S. (2008). Workplace spirituality and the selling organization: a conceptual framework and research propositions. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manage. 28, 421–434. doi: 10.2753/PSS0885-3134280406

Baek, H., Han, K., and Ryu, E. (2019). Authentic leadership, job satisfaction and organizational commitment: the moderating effect of nurse tenure. J. Nurs. Manage. 27, 1655–1663. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12853

Baker, B. D., and Lee, D. D. (2020). Spiritual formation and workplace engagement: prosocial workplace behaviors. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 17, 107–138. doi: 10.1080/14766086.2019.1670723

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 13, 209–223. doi: 10.1108/13620430810870476

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., and Lieke, L. (2012). Work engagement, performance, and active learning: the role of conscientiousness. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.08.008

Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., and Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: an emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work Stress 22, 187–200. doi: 10.1080/02678370802393649

Balducci, C., Fraccaroli, F., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the utrecht work engagement scale (uwes-9). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 26, 143–149. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000020

Barbieri, B., Amato, C., Passafaro, P., Dal Corso, L., and Picciau, M. (2014). Social support, work engagement, and non-vocational outcomes in people with severe mental illness. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 21, 181–196. doi: 10.4473/TPM21.2.5

Barrick, M. R., Thurgood, G. R., Smith, T. A., and Courtright, S. H. (2015). Collective organizational engagement: linking motivational antecedents, strategic implementation, and firm performance. Acad. Manage. J. 58, 111–135. doi: 10.5465/amj.2013.0227

Benevene, P., Dal Corso, L., De Carlo, A., Falco, A., Carluccio, F., and Vecina, M. L. (2018). Ethical leadership as antecedent of job satisfaction, affective organizational commitment and intention to stay among volunteers of non-profit organizations. Front. Psychol. 9:2069. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02069

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 107, 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Bickerton, G. R., Miner, M. H., Dowson, M., and Griffin, B. (2015). Incremental validity of spiritual resources in the job demands-resources model. Psychol. Relig. Spirit. 7, 162–172. doi: 10.1037/rel0000012

Braun, S., Peus, C., Weisweiler, S., and Frey, D. (2013). Transformational leadership, job satisfaction, and team performance: a multilevel mediation model of trust. Leadership Quart. 24, 270–283. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.11.006

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Browne, M. W., and Cudeck, R. (1993). “Alternative ways of assessing model fit,” in Testing Structural Equation Models, eds K. A. Bollen, and J. S. Long (Newbury Park, CA: SAGE), 136–162.

Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., and Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: a quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 64, 89–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x

Dal Corso, L., Carluccio, F., Buonomo, I., Benevene, P., Vecina, M. L., and West, M. (2019a). “I that is we, we that is I”: the mediating role of work engagement between key leadership behaviors and volunteer satisfaction. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 26, 561–572. doi: 10.4473/TPM26.4.5

Dal Corso, L., De Carlo, A., Carluccio, F., Girardi, D., and Falco, A. (2019b). An opportunity to grow or a label? Performance appraisal justice and performance appraisal satisfaction to increase teachers’ well-being. Front. Psychol. 10:2361. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02361

De Carlo, A., Carluccio, F., Rapisarda, S., Mora, D., and Ometto, I. (2020). Three uses of Virtual Reality in work and organizational psychology interventions - A dialogue between Virtual Reality and organizational well-being: relaxation techniques, personal resources, and anxiety/depression treatments. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 27, 129–143. doi: 10.4473/TPM27.1.8

De Carlo, N. A., Dal Corso, L., Falco, A., Girardi, D., and Piccirelli, A. (2016a). “To be, rather than to seem”: the impact of supervisor’s and personal responsibility on work engagement, job performance, and job satisfaction in a positive healthcare organization. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 23, 561–580. doi: 10.4473/TPM23.4.9

De Carlo, N. A., Dal Corso, L., Marella, L., Girardi, D., and Mantovani, P. (2016b). “Razionalità diffusa: benessere organizzativo, performance, spiritualità nel lavoro,” in Etica e Mondo Del Lavoro. Razionalità, Modelli, Buone Prassi, eds F. Menegoni, and N. A. De Carlo (Milano: FrancoAngeli), 69–96.

Do, T. T. (2018). How spirituality, climate and compensation affect job performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 14, 396–409. doi: 10.1108/SRJ-05-2016-0086

Donaldson-Feilder, E., Lewis, R., and Yarker, J. (2009). Preventing Stress: Promoting Positive Manager Behavior. CIPD Insight Report. London: CIPD Publications.

Donaldson-Feilder, E., Lewis, R., and Yarker, J. (2011). Preventing Stress in Organizations: How to Develop Positive Managers. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons.

Duchon, D., and Plowman, D. A. (2005). Nurturing the spirit at work: impact on work unit performance. Leadership. Quart. 16, 807–833. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.07.008

Dvir, T., Eden, D., Avolio, B. J., and Shamir, B. (2002). Impact of transformational leadership on follower development and performance: a field experiment. Acad. Manage. J. 45, 735–744. doi: 10.2307/3069307

Falco, A., Dal Corso, L., Girardi, D., De Carlo, A., Barbieri, B., Boatto, T., et al. (2017). Why is perfectionism a risk factor for workaholism? The mediating role of irrational beliefs at work. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 24, 583–600. doi: 10.4473/TPM24.4.8

Falco, A., Dal Corso, L., Girardi, D., De Carlo, A., and Comar, M. (2018). The moderating role of job resources in the relationship between job demands and interleukin-6 in an Italian healthcare organization. Res. Nurs. Health 41, 39–48. doi: 10.1002/nur.21844

Falco, A., Girardi, D., Dal Corso, L., Di Sipio, A., and De Carlo, N. A. (2013). Fear of workload, job autonomy, and work-related stress: the mediating role of work-home interference. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 20, 217–234. doi: 10.4473/TPM20.3.2

Falco, A., Girardi, D., Sarto, F., Marcuzzo, G., Vianello, L., Magosso, D., et al. (2012). Una nuova scala di misura degli effetti psico-fisici dello stress lavoro-correlato in una prospettiva d’integrazione di metodi [A new scale for measuring the psycho-physical effects of work-related stress in a perspective of methods integration]. Med. Lav. 103, 288–308.

Garcia-Zamor, J. C. (2003). Workplace spirituality and organizational performance. Public Admin. Rev. 63, 355–363. doi: 10.1111/1540-6210.00295

Gardner, W. L., Cogliser, C. C., Davis, K. M., and Dickens, M. P. (2011). Authentic leadership: a review of the literature and research agenda. Leadership Quart. 22, 1120–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.09.007

Giacalone, R. A., and Jurkiewicz, C. L. (eds) (2003). Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational(Performance). Armonk, NY: Me Sharpe.

Gill, H., Cassidy, S. A., Cragg, C., Algate, P., Weijs, C. A., and Finegan, J. E. (2019). Beyond reciprocity: the role of empowerment in understanding felt trust. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 28, 845–858. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2019.1678586

Girardi, D., Falco, A., Piccirelli, A., Dal Corso, L., Bortolato, S., and De Carlo, A. (2015). Perfectionism and presenteeism among managers of a service organization: the mediating role of workaholism. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 22, 507–521. doi: 10.4473/TPM22.4.5

Gupta, M., and Mikkilineni, S. (2018). “Spirituality and employee engagement at work,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Fulfillment, eds S. Dhiman, G. E. Roberts, and J. E. Crossman (Berlin: Springer), 681–695. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-62163-0_20

Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., and Ahola, K. (2008). The Job Demands-Resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work Stress 22, 224–241. doi: 10.1080/02678370802379432

Hassan, A., and Ahmed, F. (2011). Authentic leadership, trust and work engagement. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Tech. 6, 164–170.

He, J., Morrison, A. M., and Zhang, H. (2019). Improving millennial employee well-being and task performance in the hospitality industry: the interactive effects of HRM and responsible leadership. Sustainability 11:4410. doi: 10.3390/su11164410

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Hua, Y., Cheng, X., Hou, T., and Luo, R. (2019). Monetary rewards, intrinsic motivators, and work engagement in the it-enabled sharing economy: a mixed-methods investigation of internet taxi drivers. Decision. Sci. 51, 755–785. doi: 10.1111/deci.12372

Hunsaker, W. D. (2018). Workplace spirituality and well-being: examining the relationship on employee engagement in South Korea. J. Global. Bus. Adv. 11, 650–664. doi: 10.1504/JGBA.2018.097375

Ivaldi, S., and Scaratti, G. (2015). Manager on the ground: a practice based approach for developing management education: lessons from complex and innovative organizations. Appl. Psychol. Bull. 272, 42–57.

Ivaldi, S., and Scaratti, G. (2019). Coworking hybrid activities between plural objects and sharing thickness. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 26, 121–147. doi: 10.4473/TPM26.1.7

Joo, B.-K., and Lee, I. (2017). Workplace happiness: work engagement, career satisfaction, and subjective well-being. Evid. Based HRM 5, 206–221. doi: 10.1108/EBHRM-04-2015-0011

Jurkiewicz, C. L., and Giacalone, R. A. (2004). A values framework for measuring the impact of workplace spirituality on organizational performance. J. Bus. Ethics. 49, 129–142. doi: 10.1023/B:BUSI.0000015843.22195.b9

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of employee engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manage. J. 33, 692–724. doi: 10.5465/256287

Khan, S. N. (2010). Impact of authentic leaders on organization performance. Int. J. Bus. Manage. 5, 167–172.

Kinjerski, V. (2013). “The spirit at work scale: developing and validating a measure of individual spirituality at work,” in Handbook of Faith and Spirituality in the Workplace, ed. J. Neal (New York, NY: Springer), 340–383.

Kolodinsky, R. V., Giacalone, R. A., and Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2008). Workplace values and outcomes: exploring personal, organization, and interactive workplace spirituality. J. Bus. Ethics 81, 465–480. doi: 10.1007/s10551-007-9507-0

Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S. C., and Jonas, K. (2013). Transformational leadership and performance: an experimental investigation of the mediating effects of basic needs satisfaction and work engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 86, 543–555. doi: 10.1111/joop.12022

Laschinger, H. K. S., and Fida, R. (2014). New nurses burnout and workplace wellbeing: the influence of authentic leadership and psychological capital. Burn. Res. 1, 19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2014.03.002

Leroy, H., Palanski, M. E., and Simons, T. (2012). Authentic leadership and behavioral integrity as drivers of follower commitment and performance. J. Bus. Ethics 107, 255–264. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-1036-1031

Li, B., Li, Z., and Wan, Q. (2019). Effects of work practice environment, work engagement and work pressure on turnover intention among community health nurses: mediated moderation model. J. Adv. Nurs. 75, 3485–3494. doi: 10.1111/jan.14130

Liu, J., Siu, O. L., and Shi, K. (2010). Transformational leadership and employee well-being: the mediating role of trust in the leader and self-efficacy. Appl. Psychol. 59, 454–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2009.00407.x

Lizano, E. L., Godoy, A. J., and Allen, N. (2019). Spirituality and worker well-being: examining the relationship between spirituality, job burnout, and work engagement. J. Relig. Spiritual Soc. Work Soc. Thought. 38, 197–216. doi: 10.1080/15426432.2019.1577787

Luthans, F. (2002a). Positive organizational behavior: developing and managing psychological strengths. Acad. Manage. Exec. 16, 57–72. doi: 10.5465/AME.2002.6640181

Luthans, F. (2002b). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 23, 695–706. doi: 10.1002/job.165

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., and Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Modeling 11, 320–341. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2

McKee, M. C., Driscoll, C., Kelloway, E. K., and Kelley, E. (2011). Exploring linkages among transformational leadership, workplace spirituality and well-being in health care workers. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 8, 233–255. doi: 10.1080/14766086.2011.599147

Milliman, J., Czaplewski, A. J., and Ferguson, J. (2003). Work spirituality and employee work attitudes: an exploratory empirical assessment. J. Organ. Change. Manag. 16, 426–447. doi: 10.1108/09534810310484172

Müceldili, B., Turan, H., and Erdil, O. (2013). The influence of authentic leadership on creativity and innovativeness. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 99, 673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.538

Muthén, B. O., and Muthén, L. K. (2012). Mplus Version 7: User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Ng, T. W. (2017). Transformational leadership and performance outcomes: analyses of multiple mediation pathways. Leadership Quart. 28, 385–417. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.11.008

Petchsawang, P., and McLean, G. N. (2017). Workplace spirituality, mindfulness meditation, and work engagement. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 14, 216–244. doi: 10.1080/14766086.2017.1291360

Qodariah Akbar, M., and Mauluddin, M. (2019). Effect of work engagement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment to employee performance. Int. J. Recent. Technol. Eng. 8, 815–822. doi: 10.35940/ijrte.B1164.0782S419

Rahman, M. S., Zaman, M. H., Hossain, M. A., Mannan, M., and Hassan, H. (2019). Mediating effect of employee’s commitment on workplace spirituality and executive’ssales performance: an empirical investigation. J. Islam. Mark. 10, 1057–1073. doi: 10.1108/JIMA-02-2018-0024

Rana, F. A., and Javed, U. (2019). Psychosocial job characteristics, employee well-being, and quit intentions in Pakistan’s insurance sector. Glob. Bus. Organ. Exc. 38, 38–45. doi: 10.1002/joe.21933

Reijseger, G., Peeters, M. C., Taris, T. W., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2017). From motivation to activation: why engaged workers are better performers. J. Bus. Psychol. 32, 117–130. doi: 10.1007/s10869-016-9435-z

Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., and Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manage. J. 53, 617–635. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2010.51468988

Roof, R. A. (2015). The association of individual spirituality on employee engagement: the spirit at work. J. Bus. Ethics 130, 585–599. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2246-0

Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manage. Psychol. 21, 600–619. doi: 10.1108/02683940610690169

Saks, A. M. (2011). Workplace spirituality and employee engagement. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 8, 317–340. doi: 10.1080/14766086.2011.630170

Salanova, M., Lorente, L., Chambel, M. J., and Martínez, I. M. (2011). Linking transformational leadership to nurses’ extra-role performance: the mediating role of self-efficacy and work engagement. J. Adv. Nurs. 67, 2256–2266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05652.x

Salem, I. E. B. (2015). Transformational leadership: relationship to job stress and job burnout in five-star hotels. Tour. Hosp. Res. 15, 240–253. doi: 10.1177/1467358415581445

Schaufeli, W. B., and Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 25, 293–315. doi: 10.1002/job.248

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., and Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: a cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Measur. 66, 701–716. doi: 10.1177/0013164405282471

Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., and Van Rhenen, W. (2008). Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Appl. Psychol. 57, 173–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00285.x

Seligman, M. E., and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Special issue on happiness, excellence, and optimal human functioning. Am. Psychol. 55, 5–183.

Shimazu, A., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Is workaholism good or bad for employee well-being? The distinctiveness of workaholism and work engagement among Japanese employees. Ind. Health. 47, 495–502. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.47.495

Shin, Y., and Hur, W. M. (2020). Supervisor incivility and employee job performance: the mediating roles of job insecurity and amotivation. J. Psychol. 154, 38–59. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2019.1645634

Tak, J., Seo, J., and Roh, T. (2019). The influence of authentic leadership on authentic followership, positive psychological capital, and project performance: testing for the mediation effects. Sustainability 11:6028. doi: 10.3390/su11216028

van der Walt, F. (2018). Workplace spirituality, work engagement and thriving at work. J. Ind. Psychol. 44:1457. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v44i0.1457

van der Walt, F., and de Klerk, J. J. (2014). Workplace spirituality and job satisfaction. Int. Rev. Psychiatr. 26, 379–389. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2014.908826

Van Wingerden, J., and Van der Stoep, J. (2018). The motivational potential of meaningful work: relationships with strengths use, work engagement, and performance. PLoS One 13:0197599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197599

Walumbwa, F. O., Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., and Peterson, S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: development and validation of a theory-based measure. J. Manage. 34, 89–126. doi: 10.1177/0149206307308913

Wang, G., Oh, I. S., Courtright, S. H., and Colbert, A. E. (2011). Transformational leadership and performance across criteria and levels: a meta-analytic review of 25 years of research. Group Organ. Manag. 36, 223–270. doi: 10.1177/1059601111401017

Wang, H., Sui, Y., Luthans, F., Wang, D., and Wu, Y. (2014). Impact of authentic leadership on performance: role of followers’ positive psychological capital and relational processes. J. Organ. Behav. 35, 5–21. doi: 10.1002/job.1850

Wong, C. A., and Laschinger, H. K. (2013). Authentic leadership, performance, and job satisfaction: the mediating role of empowerment. J. Adv. Nurs. 69, 947–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06089.x

Keywords: positive supervisor behaviors, workplace spirituality, work engagement, employee performance, positive organizations

Citation: De Carlo A, Dal Corso L, Carluccio F, Colledani D and Falco A (2020) Positive Supervisor Behaviors and Employee Performance: The Serial Mediation of Workplace Spirituality and Work Engagement. Front. Psychol. 11:1834. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01834

Received: 05 June 2020; Accepted: 03 July 2020;

Published: 24 July 2020.

Edited by:

Giuseppe Santisi, University of Catania, ItalyReviewed by:

Ernesto Lodi, University of Sassari, ItalyPaola Magnano, Kore University of Enna, Italy

Copyright © 2020 De Carlo, Dal Corso, Carluccio, Colledani and Falco. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alessandro De Carlo, YWRlY2FybG8ucmVzZWFyY2hAYWxlc3NhbmRyb2RlY2FybG8uaXQ=

Alessandro De Carlo

Alessandro De Carlo Laura Dal Corso

Laura Dal Corso Francesca Carluccio

Francesca Carluccio Daiana Colledani

Daiana Colledani Alessandra Falco

Alessandra Falco