- 1School of Business, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China

- 2Department of Agricultural, Environmental, and Development Economics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, United States

Compromise effect suggests that a product will have a higher chance to be chosen from a product choice set when its attributes are not the extremes (the best with the highest price or the worst with the lowest price). Few studies have examined compromise effect in food purchase. We investigate consumer pork purchase decision in the context of different decoy information intended to induce behavior and consider different presentation of decoy information. Furthermore, we explore compromise effect in relation to price, quality, and safety, which are directly related to consumer health. Results demonstrate that consumers exhibit significant compromise effects after receiving both low-price and high-price decoy information. However, when decoy information is presented after consumers have made choices without decoy information, their behavior changes systematically with a weakened compromise effect. This study highlights the implications of compromise effect in food marketing and policies related to food traceability and safety.

Introduction

In the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith proposed the concept of an “economic man” and rational human behavior. The core of this theoretical hypothesis considers people as subjects pursuing maximum personal utility (Richard, 2016). Based on this hypothesis, the rational choice theory argues that consumers attach utility to each option in a product choice set and will choose a product or group of products with maximized utility, regardless of the choice set in which the product is placed (Simonson and Tversky, 1992; Aleskerov and Monjardet, 2007). In recent years, psychology theories have also been used to study human economic behavior. According to Herbert A. Simon, a pioneer of modern decision theory, human choice is an adaptation mechanism with bounded rationality, rather than an optimum mechanism with complete rationality (Herbert, 1988). To a substantial degree, consumer choices depend on the environment in which the choices are made (Ahn and Vazquez Novoa, 2016). Therefore, under bounded rationality, consumers may not always choose the option that maximizes utility, and preference for a product depends on changes in consumption context (Huber et al., 1982; Payne et al., 1992; Li, 1995). This so-called context effect can be understood as a process in which consumers consider the absolute level of attributes of a target option, but at the same time are influenced by the location of the target option relative to other options in a choice set (Tversky and Simonson, 1993; Novemsky et al., 2007).

Huber et al. (1982) stated that compromise effect is a form of context effect. Simonson (1989) later summarized the concept of compromise effect, referring to it as a phenomenon “where an option is more likely to be chosen by consumers and attracts a larger portion of choices when it is a compromising or middle option in a choice set.” Simonson (1989) and Dhar and Maach (2004) argued that during the consumer decision-making process, the most likely context effect is compromise effect. Existing literature suggests that compromise effect influences consumer choices, leading to violations of the principle of utility maximization in traditional economic theory, and reflecting the characteristics of bounded rationality (Chen et al., 2018). Understanding compromise effects has proven useful for manufacturers in market positioning, brand promotion, and creation of competition strategies (Simonson and Tversky, 1992; Ran et al., 2004). For example, to help sell a high-priced product, marketers can introduce another option with a higher price compared to the target product as decoy information (Lichters et al., 2017). Although considerable research has focused on compromise effect in general consumer products, few have explored the effect in consumer food purchasing behavior. Food safety is of great importance to human health and has thus attracted considerable consumer attention, particularly in developing countries such as China. Therefore, in this paper, we use pork products as a case to explore the existence of compromise effect in food purchases and investigate the effect under different consumption contexts.

We chose pork because it is the most popular type of meat produced and consumed in China. Data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) show that China’s pork production in 2017 was 53.50 million tons, accounting for 48.19% of the total pork output worldwide (111.03 million tons), with a per capita consumption of 39.12 kg, some 4.6 times the average of other countries. Nonetheless, pork and pork products have also triggered substantial quality and safety concerns in China. For example, Zhong and Wu (2019) reported that among the 22 436 quality and safety incidents regarding meat and meat products between 2006 and 2015, 65% of them were related to pork. These incidents were found in all areas of pork production, including breeding, slaughtering and processing, and circulation and sales, which accounted for about 39, 36, and 25% of the total number of pork-related incidents, respectively. Studying pork and measures to improve pork safety is thus relevant to food policy.

To enhance consumer knowledge and facilitate strengthened food safety, traceability measures of pork have received considerable attention in academia and industry (Heath and Chatterjee, 1995; Chuang and Yen, 2007; Chamorro et al., 2015). Although a complete food traceability system has not yet been established in China, many existing studies show that traceability plays one of the most important roles in improving consumer confidence in and consumption of pork products (Hobbs, 2004; Alfnes et al., 2018; Hou et al., 2019). As the increased costs of establishing a traceability system will also lead to higher sales prices of traceable pork, understanding consumer acceptance of traceable pork is crucial but is under-investigated in China. Therefore, in the present study, a separate goal is to also explore the future development of and consumer preference for traceable pork in China. With regard to compromise effect, if it exists in consumer purchase of traceable pork, food manufacturers and policy makers could take advantage of the compromise effect to improve acceptance and sales of traceable pork.

Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

Previous studies have examined the consumer psychology aspects of compromise effect (Wernerfelt, 1995; Mourali et al., 2007). Dhar and Simonson (2003) proposed that consumers prefer the compromise option when they are uncertain but must make a choice so as to reduce losses associated with the extreme options and minimize expected loss. Simonson and Tversky (1992) and Sheng et al. (2005) called such consumer behavior the extreme circumvention principle. Consumer characteristics, product characteristics, and the external consumption environment are the main factors that influence compromise effect. However, consumer knowledge, psychological factors, product familiarity, consumption motivation, risk perception, and attitudes toward risks can all affect compromise effect (Mishra et al., 1993; Sheng et al., 2005; Mourali et al., 2007; Sinn et al., 2007; Drolet et al., 2009; Pinger et al., 2016). Although these factors are not the focus of this study, understanding these factors can also provide insight into the causes of compromise effect and should be a continued focus of future research.

For product characteristics, attribute importance (Belk, 1977), attribute comparability (Gourville and Soman, 2007), and brand effect of the option (Sinn et al., 2007) can affect compromise effect. In particular, brand image and reputation have a significant impact on consumer decision-making. Zeithaml (1988); Richardson et al. (1994), and González et al. (2015) demonstrated that consumers have higher expectation about product quality and higher willingness to buy when a product has a better brand image. Chuang and Yen (2007) studied the impact of the origin of various products (e.g., suitcases, watches, and sports shoes) on compromise effect and found that products from Germany can have more significant compromise effect on consumers than similar products from China. This is because a product originating from an origin with less quality image passes negative information about product quality to consumers and weakens the quality and price advantages of the compromise option.

Compromise effect is closely related to the external environment of consumption (Payne et al., 1992; Mourali et al., 2007). Kahneman and Tversky (1979) and Hoek et al. (2006) stated that when the same product information is presented differently, consumers may experience different information evaluation, psychological response, or attitude toward the product, and may consequently exhibit different preferences. Yoo et al. (2018) found that product information produces a different compromise effect on consumers when manufacturers present them in different formats. For example, compared to text, information expressed in numbers, figures, or symbols can have a greater impact on consumer preference and can produce a more significant compromise effect (Frederick and Lee, 2008; Kim, 2017). The same product information can also differ in its influence on compromise effect when presented in either positive or negative context comparing to other products. For instance, Schneider et al. (2001) found that physicians are more persuasive to patients when expressing the same information in a negative frame, whereas Levin and Gaeth (1988) found that consumers prefer the presentation of information in a positive frame. The same product information can also affect compromise effect when presented in a different order (Monk et al., 2016). Chen et al. (2011) revealed that compromise effect still occurs when consumers face decoy information presented to induce consumption, but when respondents are asked to first make a choice in the absence of decoy information and then to make a choice in the presence of decoy information, the results of the two choices differ significantly and compromise effect disappears. In our analysis, we also consider decoy information, which is defined as information given to consumers to induce their focus on certain product attributes instead of presenting new product attributes.

To summarize, extensive research has been conducted on compromise effect in consumer behavior. However, previous studies have primarily focused on compromise effect in consumer purchase of general products, with few studies exploring the effects on food purchase behavior. Thus, in the current study, we investigated compromise effect and its impact on marketing and consumer choice of food products. We proposed and tested the following five hypotheses using pork based on a consumer survey conducted in Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, China. We differentiated low-price and high-price decoy information, where the former was intended to induce consumers to consider low-priced products while the latter reversed the intention.

H10: For consumers in a consumption context in the absence of decoy information, no compromise effect will occur in their behavior when choosing a pork product.

H20: For consumers in a consumption context with low-price decoy information, no compromise effect will occur in their behavior when choosing a pork product.

H30: For consumers in a consumption context with high-price decoy information, no compromise effect will occur in their behavior when choosing a pork product.

We further explored whether presenting decoy information at different stages of choice may affect choice behavior and compromise effect. This involved two stages: consumers were first asked to make a product choice without seeing any decoy information, and then they made another choice following the presentation of decoy information. Based on these considerations, we proposed the following two hypotheses:

H40: Whether the low-price decoy information was presented to consumers after they have made a choice in absence of decoy information does not affect compromise effect in their behavior when choosing a pork product.

H50: Whether the high-price decoy information was presented to consumers after they have made a choice in absence of decoy information does not affect compromise effect in their behavior when choosing a pork product.

Experimental Design, Implementation, and Sample Characteristics

We chose pork hind leg meat since it is commonly consumed in China (Wang et al., 2011). Our preliminary survey indicated that pork hind leg meat is sold at a similar market price in different urban areas of Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, China, where our study was conducted. Studying consumer behavior regarding the same pork cut can effectively reduce the influence of non-experimental factors on research conclusions (Wang et al., 2011). We considered three pork characteristics directly related to food safety; i.e., traceable, Voted-Trusted-Brand (VTB), and origin-labeled.

Based on pork quality and safety risks in real markets and the Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) system in the pork supply chain in China, as well as the impact of information asymmetry on pork safety risks, a whole-process traceable pork information system should at least cover the three main aspects: breeding, slaughtering and processing, as well as circulation and sales.

Compared with conventional pork, traceable pork inevitably has higher production costs (Meuwissen et al., 2009). Traceability system covering more players in the supply chain can better help consumers identify and reduce pork quality risks, but at the same time can also increase the price of traceable pork (Bai et al., 2017; Matzembacher et al., 2018). At present, there is no complete list of prices for various traceable pork cuts on the Chinese market (Wu et al., 2015). Hence, since our survey was conducted in Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, consistent with Wu et al. (2018), and the time lag between our study and that of Wu et al. (2018) was relatively short, we used the same traceable pork prices set by Wu et al. (2018).

In the literature review, we described the relationship between brand and product origin and consumer behavior. We also investigated two other pork hind leg meat attributes: brand and origin-label, in addition to traceable pork. Due to inconsistent pork quality, since 2005, China has been vigorously developing the program known as the consumers’ Voted-Trusted-Brand (VTB) products. Each year, China’s Brand Name Association assesses and recommends pork brands as VTB. The assessment is based on market consumption for the year and consumer evaluation collected through the assocation’s country-wide consumer opinion surveys. Pork products sold in many food markets in China are considered safe but have only met safety standards at the minimum level. Compared with such pork products, VTB pork products have better perceived quality, more reliable safety, and usually higher prices.

In China, an origin-labeled product refers to a product that is from a specific geographical region, after which it is named and upon approval by the China National Accreditation Committee. This is consistent with the definition of country-of-origin-labeled products provided by the World Trade Organization in regard to intellectual property rights. Displaying the origin of a pork product in the form of a label can provide quality or safety information (Lim et al., 2014). Origin-label and traceability have different implications. The former establishes the overall product quality in association with the customs and culture of the certified geographical origin, whereas the latter identifies the specific enterprises or individuals involved in pork production and circulation.

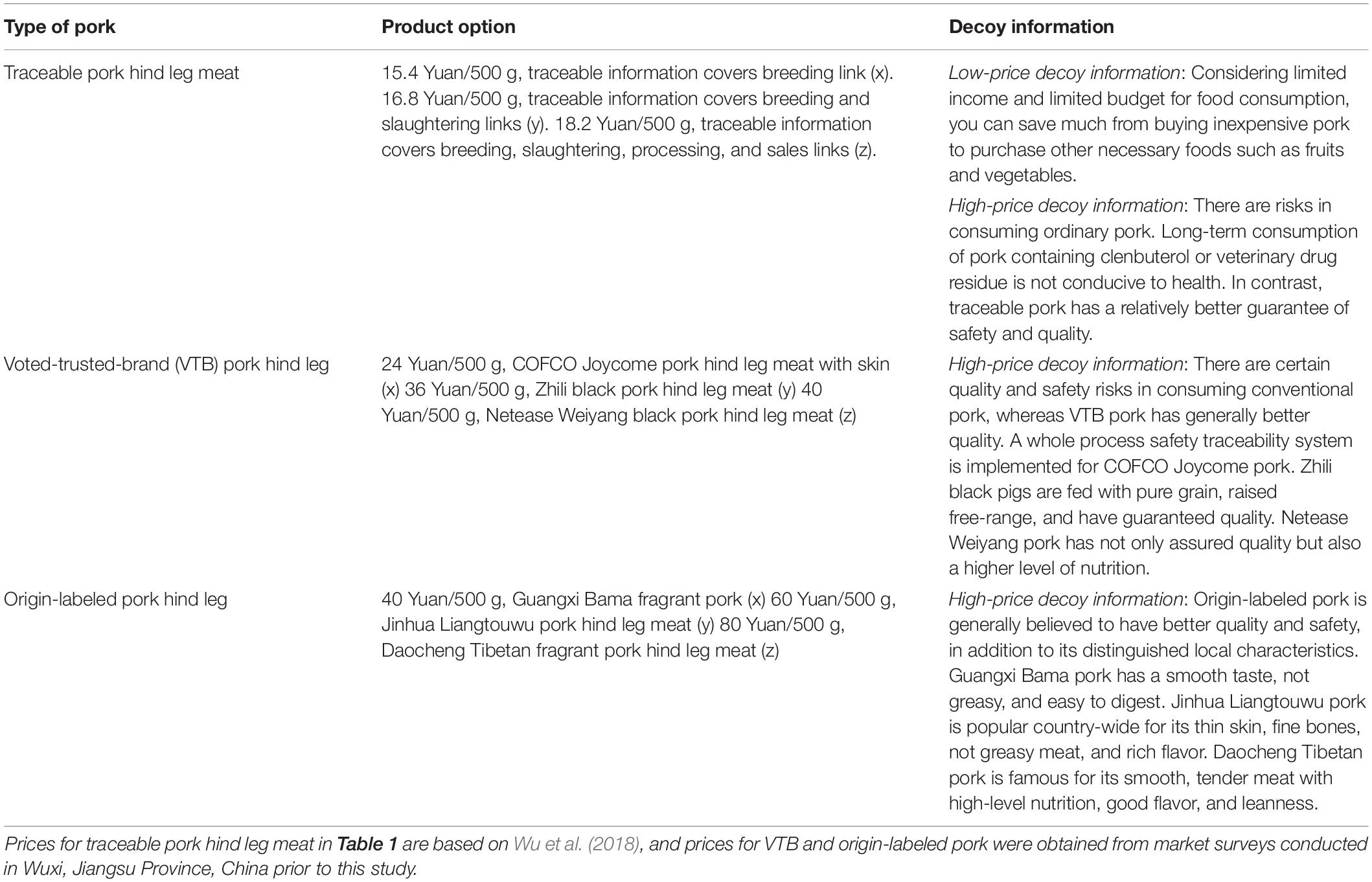

We designed three pork products, represented by x, y, and z for each of the three types of pork hind leg (pork hind leg with each of the three safety and quality characteristics), as shown in Table 1. For each type of pork, we designed different decoy information. During the survey, all pork products were presented to participants in the order of x, y or x, y, z (no option z in some sample groups) to ensure consistency and comparability of the products. As stated previously, in addition to compromise effect, a second goal of our study is to specifically examine consumer behavior regarding traceable pork. Therefore, for traceable pork, we investigated whether consumer behavior demonstrated compromise effect under both high-price and low-price decoy information, whereas for the VTB and origin-labeled pork, we only implemented high-price decoy information due to article length constraints.

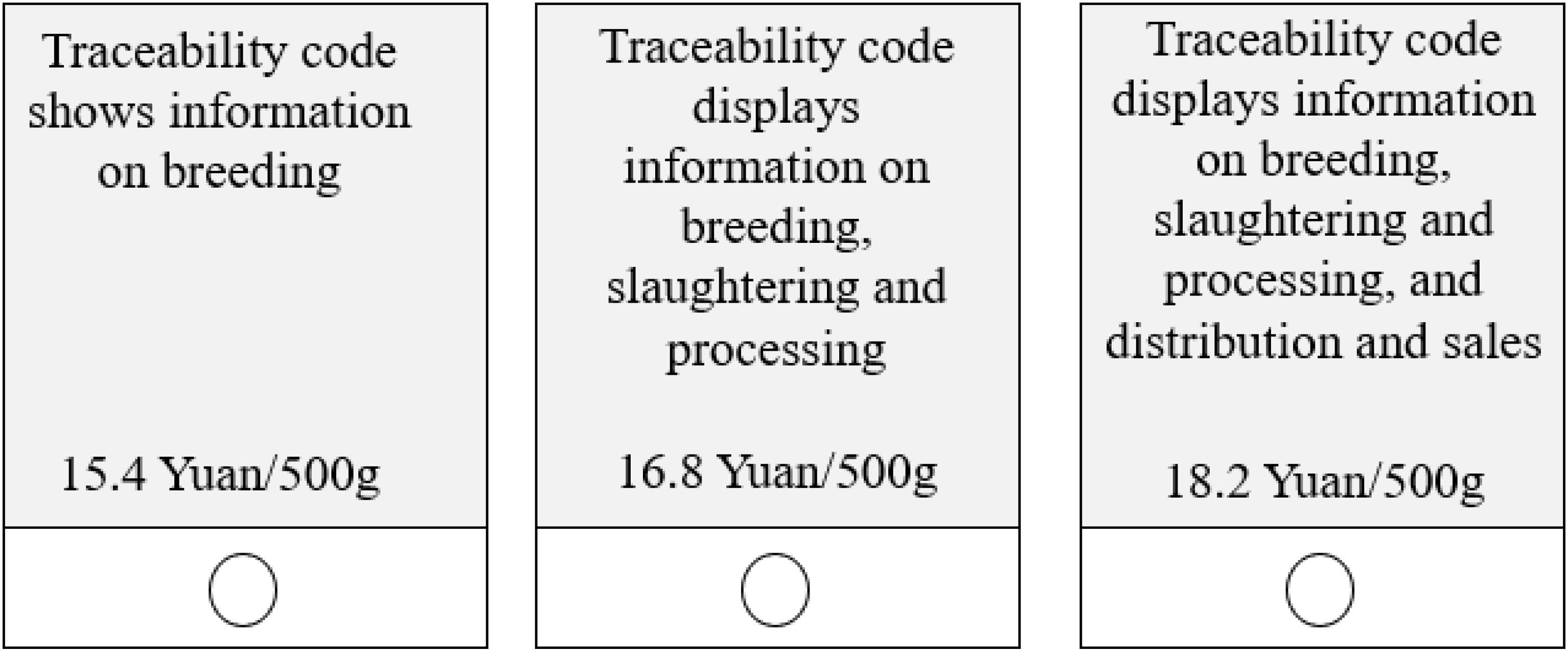

To present participants a choice context similar to a real consumption environment, we conducted our survey in large-scale super stores, pork shops, farmers’ markets, and shopping centers where consumers were engaging in actual grocery purchase in Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, China. The survey was conducted in August 2018 with a total of 1176 completed responses. Each respondent who completed the questionnaire was given a gift of 5 Yuan as compensation for their time. The interviewers were trained postgraduate students from a local university. The interviewers approached every third adult shopper came to their sight. Although respondents were not asked to make actual purchase, all pork products described in our survey were presented on site for participants to view and examine. Based on the objectives of the study, we designed eight sample groups, into which each survey participant was randomly assigned. Figure 1 shows a choice set of traceable pork. The options were represented by x, y, and z in the same left to right order in all sample groups. The number of pork products and number of choice sets each respondent review was different but the order of products presented in each choice set followed the order of x, y, and z in Table 1. The detailed description of the eight sample groups is as follows:

• Sample group #1 (no decoy information, two traceable pork options): Respondents made a choice in the absence of decoy information from a choice set composed two traceable pork hind leg meat products x and y, as shown in Table 1.

• Sample group #2 (no decoy information, three traceable pork options): Respondents made a choice in the absence of decoy information from a choice set composed of three traceable pork hind leg meat products x, y, and z, as shown in Table 1.

• Sample group #3 (low-price decoy information, two traceable pork options): Respondents were asked to first review the low-price information and then make a choice from a choice set composed of two traceable pork hind leg meat products x and y, as shown in Table 1.

• Sample group #4 (low-price decoy information, three traceable pork options): Respondents were asked to first review the low-price information and then make a choice from a choice set composed of three traceable pork hind leg meat products x, y, and z as shown in Table 1.

• Sample group #5 (first no decoy information, three traceable pork options, followed by low-price decoy information, same three traceable pork options): Respondents were first asked to make a choice in the absence of decoy information from a choice set composed of three traceable pork options as x, y, and z shown in Table 1. Then, low-price decoy information was presented and the same respondents were asked to make a choice from the same choice set.

• Sample group #6 (no decoy information, three types of pork products): Respondents made a choice in the absence of decoy information for each of the three types of products (traceable, VTB, and origin-labeled pork). For each type of product, three options were presented (i.e., products x, y, and z as shown in Table 1).

• Sample group #7 (high-price decoy information, three types of pork products): For each type of three pork products (traceable, VTB, and origin-labled pork), respondents were asked to first review the high-price information and then make a choice from a choice set composed of three options for each type of pork (i.e., products x, y, and z for each of the three types of pork hind leg meat, as shown in Table 1).

• Sample group #8 (first no decoy information, three types of pork products, followed by high-price decoy information, three types of pork products): For each of three types of pork (traceable, VTB, and origin-labeled pork), respondents were first asked to make a choice in the absence of decoy information from a choice set composed of three options (i.e., products x, y, and z for each of the three types of pork, as shown in Table 1). Then high-price decoy information was presented and the same respondents were asked to make a choice from each of the same choice set for the three types of products, respectively.

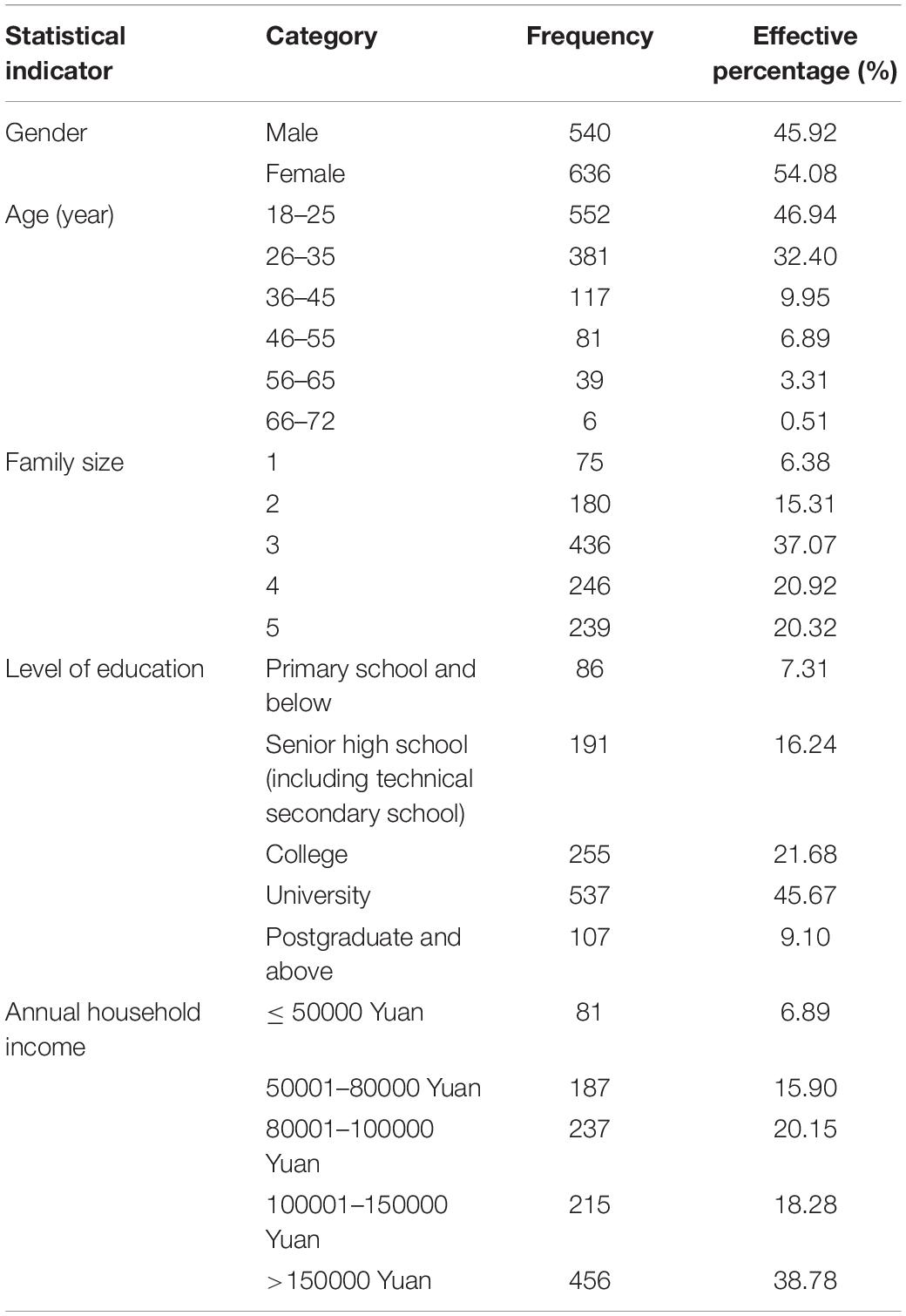

Characteristics of the total of 1176 adult consumers recruited into the study are shown in Table 2. These characteristics coincided with those in previous studies involving Chinese pork consumers (Wu et al., 2012).

Analysis Framework

Based on Chernev (2004), Eq. 1 calculates the change of the share of compromise option y being chosen between choice set {x, y} and {x, y, z}:

where, P(y; x) is the share of option y relative to option x chosen from choice set {x, y}: and PZ(y; x) is the share of compromise option y relative to option x chosen from choice set {x, y, z}. PZ(y; x) indicates the attractiveness of compromise option y relative to x after the addition of the third traceable pork option z to the set, calculated using:

where, P(y; x, z) is the share of compromise option y from choice set {x, y, z} and P(x; y, z) is the share of option x in choice set {x, y, z}.

H1 can be tested by observing the share of option y chosen in sample groups #1 and #2. P1 (y, x) can be defined as the share of option y chosen in the two-option choice set {x, y} in sample group #1, and P2z (y, x) can be defined as the share of option y chosen after option z was added to the set in sample group #2. If P1 (y, x) ≥ P2z (y, x), then hypothesis H10 cannot be rejected.

H2 can be tested by observing the share of option y chosen in sample groups #3 and #4. If P3 (y, x) ≥ P4z (y, x) (both with similar definitions as above), then hypothesis H20 cannot be rejected.

H3 can be tested by observing the share of options y and z chosen in sample groups #6 and #7. If P7 (z, x) ≥ P7z (y, x), then hypothesis H30 cannot be rejected. In this design, tests were conducted for each of the three types of products.

Using sample groups #2 and #4, P2z (y, x) and P4z (y, x) can be obtained. The values for P5az (y, x) and P5bz (y, x) (which represent the share of option y chosen without and with decoy information, respectively) can be obtained from sample group #5. Then P4z (y, x) – P2z (y, x) and P5bz (y, x) – P5az (y, x) can be calculated, respectively. If P4z (y, x) – P2z (y, x) = P5bz (y, x) – P5az (y, x), then hypothesis H40 cannot be rejected.

Using sample groups #6 and #7, P6z(y, x) and P7z(y, x) can be obtained. The values for P8az(y, x) and P8bz(y, x) (with similar definitions as to P5az(y, x) and P5bz(y, x), respectively) can be obtained from sample group #8. Similarly, if P7z(y, x) – P6z(y, x) = P8bz(y, x) – P8az(y, x), hypothesis H50 cannot be rejected. Tests can be conducted for each of the three types of pork products.

Results and Discussion

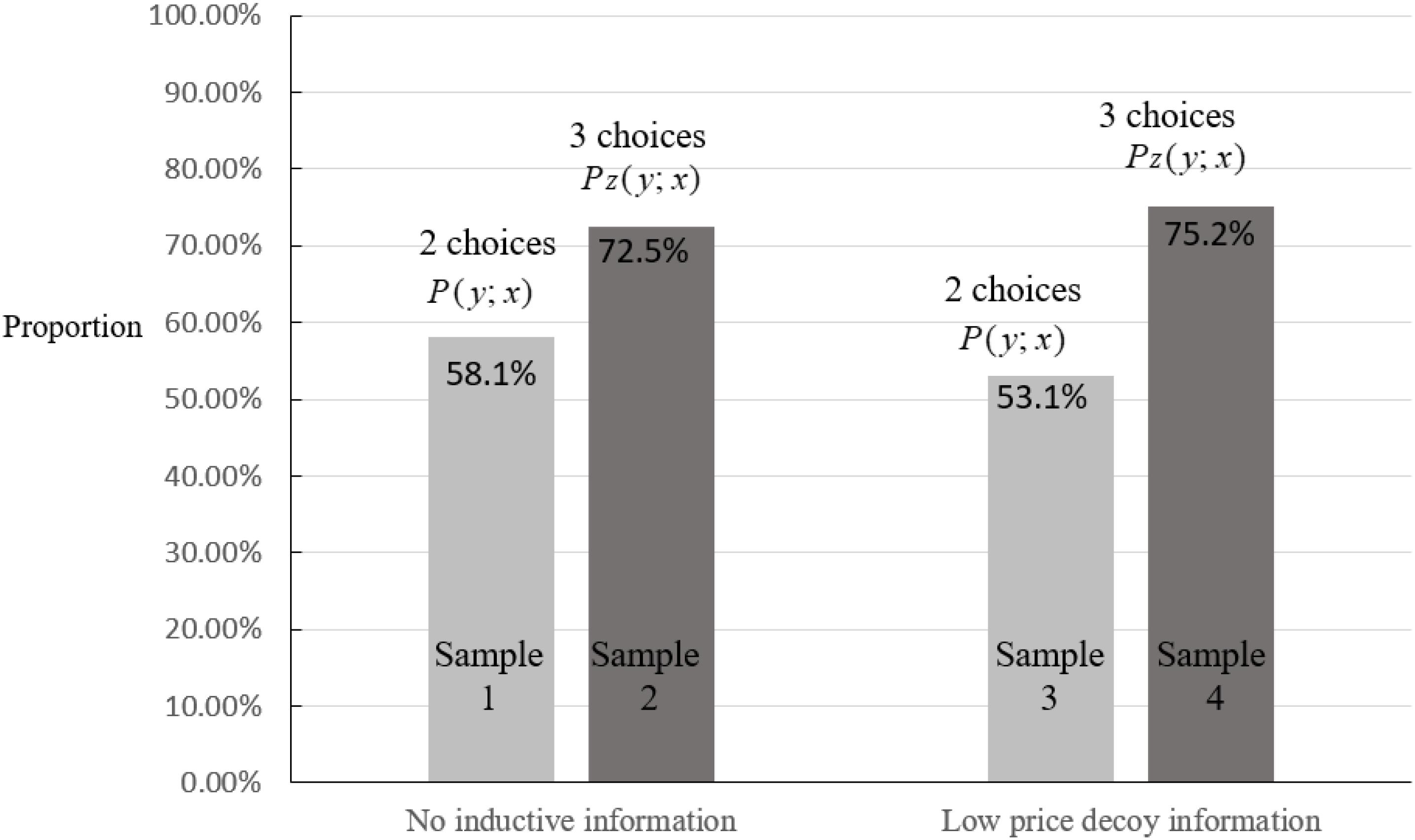

In the absence of decoy information, the share of choosing compromise option y was 58.1% in sample group #1 (no decoy information and two traceable options) from choice set {x, y}, which increased to 72.5% in sample group #2 (no decoy information and three traceable options) from choice set {x, y, z} (see Table 3 and Figure 2), with ΔP = 21.94% (χ2 = 29.26, p < 0.001), P1 (y, x) < P2z (y, x). Therefore, hypothesis H10 can be rejected, indicating compromise effect occurring in consumer behavior in the absence of decoy information.

Under the low-price decoy information context, the share of choosing compromise option y was 53.1% in sample group #3 (low-price decoy information and two traceable options) from choice set {x, y}, which increased to 75.2% in sample group #4 (low-price decoy information and three traceable options) from choice set {x, y, z} (see Table 3 and Figure 2), with ΔP = 30.46% (χ2 = 45.35, p < 0.001), P3 (y, x) < P4z (y, x). Therefore, hypothesis H20 is rejected, showing compromise effect occurring in consumer behavior under low-price decoy information context.

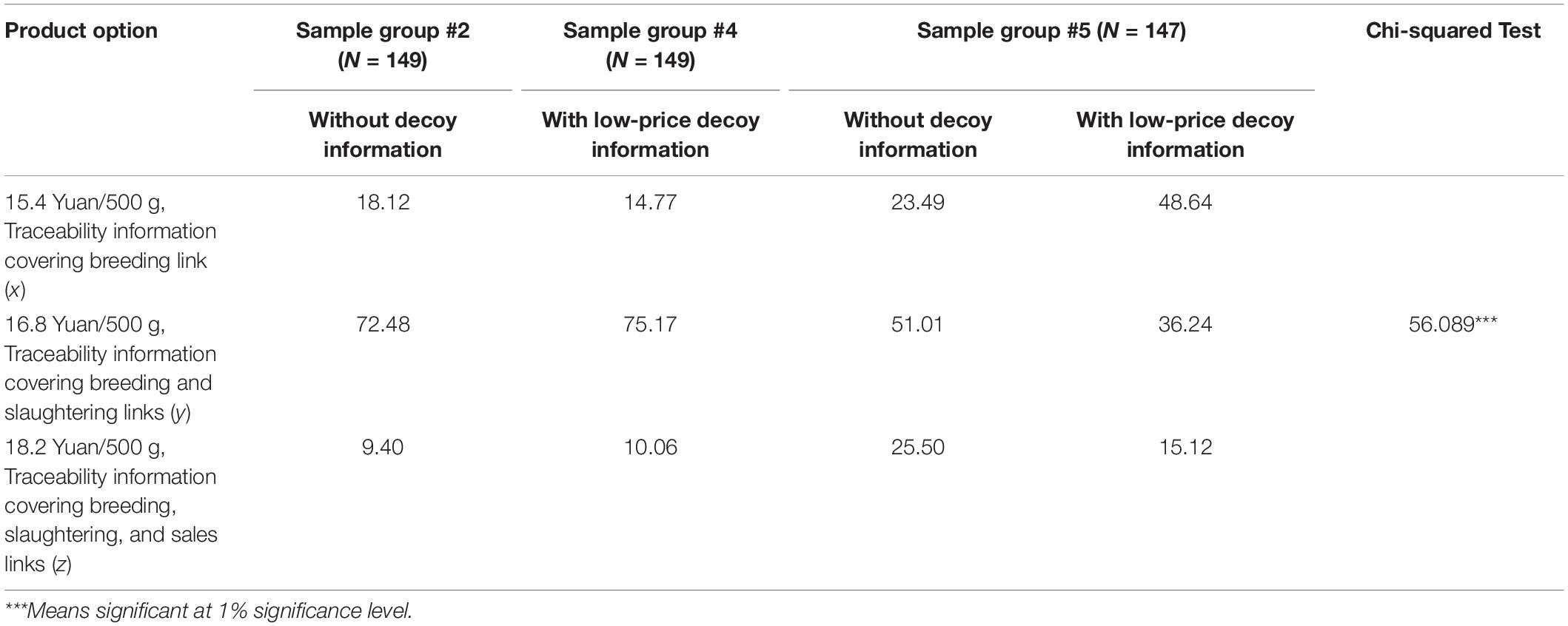

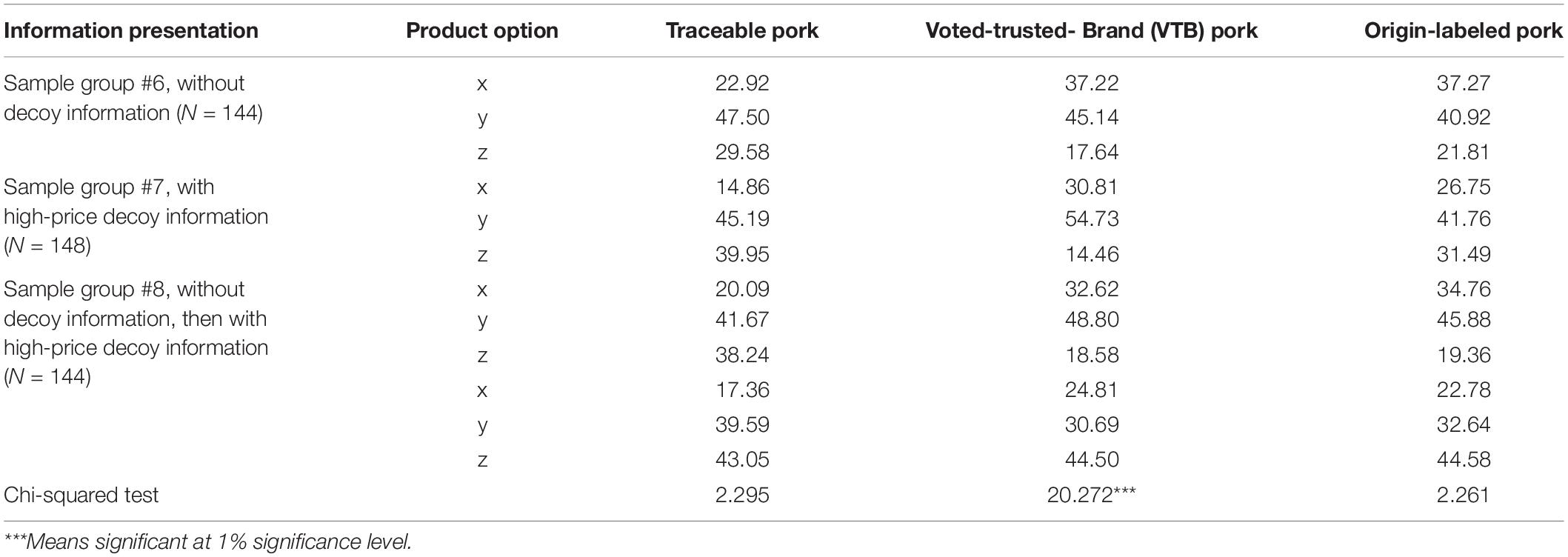

We also test the influence of high-price decoy information on participant choices, as presented in Table 4. In group #7 (high-price decoy information for all three types of pork), the share of compromise option y chosen by participants from the three traceable pork choice set {x, y, z} was 45.19% and the share of option z was 39.95% (χ2 = 23.08, p < 0.05), suggesting that option y shows a compromise effect under this context. Also in group #7, the share of the VTB pork option y chosen by participants was 54.73% and that of option z was 14.46% (χ2 = 36.36, p < 0.05), demonstrating the existence of compromise effect in the share of option y. The share of origin-labeled pork option y chosen by group #7 was 41.76%, and that of option z was 31.49% (χ2 = 5.20, p < 0.01), suggesting the existence of compromise effect in option y. Based on these results, H30 can be rejected and participant choice behavior showed a compromise effect. As shown in Table 3, P2z (y, x) was 72.48% and P4z (y, x) was 75.17%. For sample group #5 (first no decoy information and then low-price decoy information for all three types of pork), the values for P5az (y, x) and P5bz (y, x) were 51.01 and 36.24%, respectively. Hence, P4z (y, x)–P2z (y, x)≠ P5bz (y, x)–P5az (y, x) (χ2 = 56.089, p < 0.01). Therefore, hypothesis H40 can be rejected. In other words, whether the low-price decoy information is given after consumers have experienced non-decoy information affected compromise effect.

We next tested hypothesis H5, based on findings shown in Table 4. Results showed that P7z(y, x), P8az(y, x), and P8bz(y, x) for traceable pork compromise option were 45.19, 41.67, and 39.59%, respectively, hence, P7z(y, x)–P6z(y, x)≠ P8bz(y, x)–P8az(y, x) (χ2 = 2.295, p = 0.317). Values of P7z(y, x), P8az(y, x), and P8bz(y, x) for VTB pork compromise option were 54.73, 48.80, and 30.69%, respectively, hence, P7z(y, x)–P6z(y, x)≠ P8bz(y, x)–P8az(y, x) (χ2 = 20.272, p < 0.01). Values of P7z(y, x), P8az(y, x), and P8bz(y, x) for the origin-labeled pork compromise option were 41.76, 45.88, and 32.64%, respectively, hence P7z(y, x)–P6z(y,x)≠ P8bz(y, x)–P8az(y, x) (χ2 = 2.261, p = 0.3230). Therefore, H50 can be rejected for all three types of pork products. In other words, whether the high-price decoy information is given after consumers have experienced non-decoy information affected compromise effect.

Chen et al. (2011) revealed that the likelihood of a compromise option being chosen by participants decreases under decoy information in comparison to when no decoy information is presented. In contrast, however, our results showed that participants still preferred pork product option y and showed a significant compromise effect.

Results of testing hypothesis H4 based on Table 4 shows participant choices under different consumption contexts in the absence of decoy information and in the presence of low-price decoy information. When participants made choices without decoy information (sample group #2). Under this context, compromise option y was selected most often, and a significant compromise effect occurred. In sample group #4, participants made a choice in the presence of decoy information. Comparing sample groups #2 to #4, compromise option y exhibited an absolute advantage and had the largest choice share. However, in sample group #5, we found that if respondents first made a choice in the absence of decoy information and then made a choice again after receiving low-price decoy information, the share of option y decreased from 51.01 to 36.24% (χ2 = 56.089, p < 0.01) and compromise effect disappeared. Further analysis of sample groups #4 and #5 after the addition of low-price decoy information showed that consumer choices differed greatly. Specifically, the share of option x chosen by participants increased from 14.77% in sample group #4 to 48.64% in sample group #5, whereas that of option y decreased from 75.17 to 36.24%, respectively. Option x was traceable pork with the lowest price. The intention of the decoy information was to induce participants to consider low-priced traceable pork. However, this decoy effect did not occur in sample group #4.

Similar results were observed when testing H5 based on Table 3. We observed the three choice decisions made by participants in sample group #8 and found that without decoy information, the shares of compromise option y were 41.67, 48.80, and 45.88%, respectively. When the same participants chose again after the addition of high-price decoy information, the shares of compromise option y decreased to 39.59, 30.69, and 32.64%, respectively. Further analysis revealed that the share of option y chosen by sample group #8 under a high-price decoy information context was significantly lower than that of option z, which then became the most preferred product.

These findings suggested that a change in the presentation of decoy information had an influence on compromise effect. Presenting the decoy information after a choice without decoy information weakened compromise effect (in sample group #5 and #8). However, for sample groups #4 or #7, significant decoy effect was still observed, even though these consumers were presented with the same decoy information. Overall, we find that when facing three pork options in a choice set {x, y, z}, participants generally considered it attractive to choose the compromise option, thus showing a clear compromise effect. When the presentation of decoy information is moved after a choice without decoy information, participant preference changed to exhibit less compromise effect.

Conclusion and Implications

This paper focused on understanding compromise effect in consumer choices of pork products under a consistent sequence of product presentation. We also examined the impact of different decoy information and whether the information was presented with or without the respondents first making a choice with no decoy information. As demonstrated, consumer decision-making in pork purchases showed significant compromise effect. Furthermore, compromise effect exists under decoy information featured as high-price and low-price information in this research. However, when consumers made an initial choice without any decoy information, and then chose again following the presentation of decoy information, their choices were more spread out across all products in the choice set and the compromise effect disappeared. This is a reflection of how changes in the presentation of decoy information influenced consumer behavior.

In this study, we used pork to demonstrate that consumer choices exhibited compromise effect with or without decoy information. However, the size of compromise effect may not be identical for all types of food. As the main source of animal protein for Chinese consumers and a basic component of the Chinese CPI, demand price elasticity for pork is lower than that for most other foods. If a product with even lower demand elasticity was used in this study (for instance, rice or wheat flour), the intensity of compromise effect may need reevaluation when these products are compared in one choice set with those having higher demand elasticity. However, within one product category, we expect compromise effect still to take place.

In sample groups #5 and #8 in our study, in order to ensure that the choices of the same respondents before and after the decoy information were not influenced by the order of product presentation, we maintained a consistent product order in the choice set before and after the presentation of decoy information. This also allows a more direct comparison with choices made in other sample groups. This means that during our entire study, the products were always presented to the respondents in the order of x, y, and z. A drawback of this approach is that the order effect may be confounded with compromise effect. Furthermore, compromise effect is being tested predominantly in the literature by varying the number of products/attributes in a choice set. Another layer of confounding may occur between the number of products/attributes and compromise effect, although we argue that based on our consistent discovery of compromise effect in product choice sets with different numbers of products/attributes, the possible confounding effect may not significantly undermine our findings. Limited by the current length of the article, we have not specifically tackled these potential confounding effects, which may be a valuable subject for exploration in future research.

The conclusions of this study have several policy implications. Much of our findings on traceable pork suggest that the Chinese government should encourage manufacturers to produce traceable pork with diverse levels of traceable information at varied prices to form a traceable pork system. This will not only satisfy the diverse demand for traceable pork, if traceability is deemed as the prominent tool to assist the construction of a safer national pork supply chain, manufacturers should be encouraged to increase the market share of traceable pork products by harnessing the compromise effect to promote traceable pork.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this manuscript are not publicly available to protect subjects’ privacy, and to comply with regulations set by Jiangsu Social Science Fund Major Project. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by human ethics review board of the Jiangnan University of China. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

LW: proposing the research direction of the thesis and designing the structure of the article. XG: questionnaire and manuscript drafting. XC and WH: revise and propose.

Funding

This work was supported by two funding which are the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 71633002 and 71803067), and Jiangsu Social Science Fund Major Project (Grant No. 18ZD004).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Ahn, H., and Vazquez Novoa, N. (2016). The decoy effect in relative performance evaluation and the debiasing role of DEA. Eur. J. Operat. Res. 249, 959–967. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2015.07.045

Aleskerov, F., and Monjardet, B. (2007). Utility Maximization, Choice and Preference. Germany: Springer.

Alfnes, F., Chen, X., and Rickertsen, K. (2018). Labeling farmed seafood: A review. Aquacult. Econ. Manag. 22, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/13657305.2017.1356398

Bai, H., Zhou, G., Hu, Y., Sun, A., Xu, X. L., Liu, X., et al. (2017). Traceability technologies for farm animals and their products in China. Food Control 79, 35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.02.040

Belk, R. W. (1977). “A free response approach to developing product-specific consumption situation taxonomies,” in Analytic Aproaches to Product and Market Planning, A. D. Shocker (Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute).

Chamorro, A., Rubio, S., and Miranda, F. J. (2015). The region-of-origin (ROO) effect on purchasing preferences: the case of a multiregional designation of origin. Br. Food J. 117, 820–839. doi: 10.1108/bfj-03-2014-0112

Chen, J. S., Fu, G. Q., and Wu, J. T. (2011). The influence of decoy information on the compromise effect of consumers choice-making. Chin. J. Manag. 8, 437–442, 474.

Chen, S.-Y., Chuang, C.-H., and Chen, S.-J. (2018). A conceptual review of human resource management research and practice in Taiwan with comparison to select economies in East Asia. Asia Pacific J. Manag. 35, 213–239. doi: 10.1007/s10490-017-9516-1

Chernev, A. (2004). Extremeness aversion and attribute-balance effects in choice. J. Cons. Res. 31, 249–263. doi: 10.1086/422105

Chuang, S. C., and Yen, H. J. R. (2007). The impact of a product’s country-of-origin on compromise and attraction effects. Market. Lett. 18, 279–291. doi: 10.1007/s11002-007-9017-y

Dhar, R., and Maach, M. B. (2004). Toward extending the compromise effect to complex buying contexts. J. Market. Res. 41, 258–261. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.41.3.258.35996

Dhar, R., and Simonson, I. (2003). The Effect of Forced Choice on Choice. J. Market. Res. 40, 146–160. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.40.2.146.19229

Drolet, A., Luce, M. F., and Simonson, I. (2009). When does choice reveal preference? Moderators of Heuristic versus goal-based choice. J. Cons. Res. 36, 137–147. doi: 10.1086/596305

Frederick, S., and Lee, L. (2008). Attraction, repulsion, and attribute representation. Adv. Cons. Res. 35, 122–123.

González, B. Ó, Martos-Partal, M., and San Martín, S. (2015). Brands as substitutes for the need for touch in online shopping. J. Retail. Cons. Serv. 27, 121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.07.015

Gourville, J. T., and Soman, D. (2007). Extremeness Seeking: When and Why Consumers Prefer the Extremes. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Working Paper.

Heath, T. B., and Chatterjee, S. (1995). Asymmetric decoy effects on lower-quality versus higher-quality brands: Meta-analytic and experimental evidence. J. Cons. Res. 22, 268–284.

Herbert, A. S. (1988). Administrative Behavior: A Study of Decision-Making Process in Administrative Organizations. Beijing: Beijing Economics College Press.

Hobbs, J. E. (2004). Information asymmetry and the role of traceability systems. Agribusiness 20, 397–415. doi: 10.1002/agr.20020

Hoek, J., Pope, T., Young, K., and Young, K. (2006). Message framing effects on price discounting. J. Product Brand Manag. 15, 458–465. doi: 10.1108/10610420610712847

Hou, B., Wu, L. H., Chen, X. J., Zhu, D., Ying, R. Y., and Tsai, F. S. (2019). Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Foods with Traceability Information: Ex-Ante Quality Assurance or Ex-Post Traceability? Sustainability 11, 1464–1478.

Huber, J., Payne, J. W., and Putoc, A. (1982). Adding asymmetrically dominated alternatives violation of regularity and the similarity hypothesis. J. Cons. Res. 9, 90–98.

Kahneman, D., and Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47, 263–291.

Kim, J. (2017). The influence of graphical versus numerical information representation modes on the compromise effect. Market. Lett. 28, 397–409. doi: 10.1007/s11002-017-9419-4

Levin, I. P., and Gaeth, G. J. (1988). How Consumers Are Affected by the Framing of Attribute Information Before and After Consuming the Product. J. Cons. Res. 15, 374–378.

Lichters, M., Bengart, P., Sarstedt, M., and Vogt, B. (2017). What really matters in attraction effect research: when choices have economic consequences. Market. Lett. 28, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11002-015-9394-6

Lim, K. H., Hu, W. Y., Maynard, L. J., and Goddard, E. (2014). A taste for safer beef? How Much does consumers’ perceived risk influence willingness to pay for country-of-origin labeled beef. Agribusiness 30, 17–30. doi: 10.1002/agr.21365

Matzembacher, D. E., Stangherlin, I. D. C., Slongo, L. A., and Cataldi, R. (2018). An integration of traceability elements and their impact in consumer’s trust. Food Control 92, 420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.05.014

Meuwissen, M. P. M., Velthuis, A. G. J., Hogeveen, H., and Huirne, R. B. M. (2009). Traceability and certification in meat supply chains. J. Agribus. 21, 167–181.

Mishra, S., Umesh, U. N., and Stem, D. E. (1993). Antecedents of the attraction effect: an information-processing approach. J. Market. Res. 30, 331–349. doi: 10.1177/002224379303000305

Monk, R. L., Qureshi, A. W., Leatherbarrow, T., and Hughes, A. (2016). The decoy effect within alcohol purchasing decisions. Subst. Use Misuse 51, 1353–1362. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2016.1168449

Mourali, M., Böckenholt, U., and Laroche, M. (2007). Compromise and attraction effects under prevention and promotion motivations. J. Cons. Res. 34, 234–247. doi: 10.1086/519151

Novemsky, N., Dhar, R., and Schwarz, N. (2007). Preference fluency in choice. J. Market. Res. 44, 347–356. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.44.3.347

Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., and Johnson, E. J. (1992). Behavioral decision research: a constructive processing perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 43, 87–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.43.020192.000511

Pinger, P., Ruhmer-Krell, I., and Schumacher, H. (2016). The compromise effect in action: lessons from a restaurant’s menu. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 128, 14–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2016.04.017

Ran, K., Netzer, O., and Srinivasan, V. (2004). alternative models for capturing the compromise effect. J. Market. Res. 41, 237–257. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.41.3.237.35990

Richard, T. (2016). Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Richardson, P. S., Dick, A. S., and Jain, A. K. (1994). Extrinsic and intrinsic cue effects on perceptions of store brand quality. J. Market. 58, 28–36. doi: 10.1177/002224299405800403

Schneider, T. R., Salovey, P., Apanovitch, A. M., Pizarro, J., McCarthy, D., Zullo, J., et al. (2001). The effects of message framing and ethnic targeting on mammography use among low-income women. Health Psychol. Official J. Divis. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 20, 256–266. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.4.256

Sheng, S., Parker, A. M., and Nakamoto, K. (2005). Understanding the mechanism and determinants of compromise effects. Psychol. Market. 22, 591–609. doi: 10.1002/mar.20075

Simonson, I. (1989). Choice based on reasons: the case of attraction and compromise effects. J. Cons. Res. 16, 158–174.

Simonson, I., and Tversky, A. (1992). Choice in context: trade-off contrast and extremeness aversion. J. Market. Res. 39, 281–292.

Sinn, F., Milberg, S. J., Epstein, L. D., and Goodstein, R. C. (2007). Compromising the compromise effect: Brands matter. Market. Lett. 18, 223–236. doi: 10.1007/s11002-007-9019-9

Wang, H. M., Ni, C. J., and Xu, R. L. (2011). An empirical study on consumers’ willingness to pay for food quality and safety identification – pork consumption in Nanjing. J. Nanjing Agricult. Univ. 11, 21–29.

Wernerfelt, B. (1995). A rational reconstruction of the compromise effect: using market data to infer utilities. J. Cons. Res. 21, 627–633.

Wu, L., Bu, F., and Zhu, D. (2012). Consumer preference analysis of traceable pork with different quality and safety information. Chinese Rural Econ. 2012, 13–23.

Wu, L., Wang, S., Zhu, D., Hu, W., and Wang, H. (2015). Chinese consumers’ preferences and willingness to pay for traceable food quality and safety attributes: The case of pork. China Econ. Rev. 35, 121–136. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2015.07.001

Wu, L. H., Gong, X. R., Chen, X. J., and Zhu, D. (2018). Study on consumer preference for traceability information with ex ante quality assurance and ex post tracing function. China Populat. Resour. Environ. 8, 42–54.

Yoo, J., Park, H., and Kim, W. (2018). Compromise effect and consideration set size in consumer decision-making. Appl. Econ. Lett. 25, 513–517. doi: 10.1080/13504851.2017.1340567

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Market. 52, 2–22. doi: 10.1177/002224298805200302

Keywords: compromise effect, consumer preference, decoy information, pork products, anchoring effect

Citation: Wu L, Gong X, Chen X and Hu W (2020) Compromise Effect in Food Consumer Choices in China: An Analysis on Pork Products. Front. Psychol. 11:1352. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01352

Received: 11 February 2020; Accepted: 21 May 2020;

Published: 30 June 2020.

Edited by:

Shalini Srivastava, Jaipuria Institute of Management, IndiaReviewed by:

Li Zhou, Nanjing Agricultural University, ChinaKelly Davidson, University of Delaware, United States

Copyright © 2020 Wu, Gong, Chen and Hu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Linhai Wu, d2xoNjc5OUBqaWFuZ25hbi5lZHUuY24=

Linhai Wu

Linhai Wu Xiaoru Gong1

Xiaoru Gong1 Xiujuan Chen

Xiujuan Chen Wuyang Hu

Wuyang Hu