- 1Faculty of Psychology, University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland

- 2Institute of Psychology, Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University, Warsaw, Poland

The concept of acceptance, understood as a self-regulation strategy based on an open and welcoming attitude toward one's own emotions, thoughts, or external events (Williams and Lynn, 2010)1, is present in various domains of psychological research and practice. Previous studies have brought important knowledge on the nature of this strategy, but very significant gaps in the knowledge still exist.

The most important issues are as follows: (1) conceptual difficulties regarding acceptance as an emotion regulation strategy; (2) lack of coherence in operationalizations of acceptance in various research; and (3) acceptance not being recognized as a distinct emotion regulation strategy in the most influential emotion regulation models. In the present paper we highlight and discuss these issues in more detail and—based on this discussion, postulate directions for future experimental research on acceptance.

The popularity of research on acceptance has grown steadily since the 1990s, when acceptance-based therapeutic approaches started to develop more rapidly. For example, the role of acceptance was underlined in the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 1999), as well as other approaches.

Many different forms of acceptance-based programs were developed and tested for effectiveness. They were shown to be successful in stress and pain reduction as well as decreasing anxiety and depression symptoms (Segal et al., 2002; Hayes et al., 2006; Veehof et al., 2011; Twohig and Levin, 2017; Feliu-Soler et al., 2018). Other studies showed the role of mindfulness and acceptance for the severity of psychotic symptoms (Cramer et al., 2016; Jansen et al., 2019), eating disorders (Prefit et al., 2019), compulsive sexual behavior (Lew-Starowicz et al., 2019), addictive behaviors (Bowen et al., 2011), suicidal ideation and self-harm (Tighe et al., 2018) as well as other psychopathological symptom clusters (Aldao et al., 2010).

The definitional goal of acceptance as an emotion regulation strategy is not to change the experienced emotions, but to receive them without control attempts (Hayes, 2004; Kohl et al., 2012). Thus, acceptance is quite distinct from other frequently studied ways of regulating emotion (e.g., suppression, most forms of cognitive reappraisal, rumination) that are most often based on some form of active modification of emotional state in terms of quality, strength, length, or frequency of emotion (Gross, 2015). Despite these differences, acceptance is present in psychological research on emotion regulation and is often compared with other regulatory strategies (e.g., Liverant et al., 2008; Aldao et al., 2010; Naragon-Gainey et al., 2017; Southward et al., 2019). However, despite the presence of acceptance in the work of both psychological practitioners and theoreticians, we stumble upon significant difficulties when trying to find acceptance in broader theoretical models of emotion regulation. ACT has its theoretical roots in the theory of Relational Frames (Barnes-Holmes et al., 2001). However, many techniques designed to support emotional acceptance that are applied in therapeutic practice itself are not very close to the theoretical model. What is crucial is that acceptance is not explicitly present within the most influential model of emotion regulation, i.e., Gross's process model (Gross, 1998), although it is present in others (Gratz and Roemer, 2004; Berking et al., 2008). According to the conception put forward by Gratz and Roemer (2004), (a) non-acceptance of emotion and (b) lack of emotional awareness and (c) clarity are three out of six of the most important areas of difficulties in emotion regulation.

Some authors suggest that within Gross's model, acceptance should be classified within the attentional deployment strategies' family (e.g., Slutsky et al., 2017), while others see it as a form of reappraisal (e.g., Webb et al., 2012), depending on whether they focus on either acceptance as influencing attention or acceptance as a way of understanding the whole emotional experience. These two approaches to acceptance-based strategies hint at another important issue visible in the acceptance literature: lack of conceptual clarity and stark differences in operationalizations of this emotion regulation strategy. This leads to difficulties in integrating the results of research on acceptance and possibly to high variability in the results of research on acceptance effectiveness. This point will be elaborated on in following sections. Previous research contains attempts at placing acceptance-related strategies within other classes of regulation emotion strategies and studying the underlying factor structure (see e.g., Naragon-Gainey et al., 2017), although more research on this front is needed to provide us with reliable and parsimonious solutions.

According to a meta-analysis by Webb et al. (2012), acceptance-like strategies are—on average—effective (d = 0.30, the effect sizes are reported in terms of Cohen's d, Cohen, 1988)—their effectiveness is, moreover, higher than the effectiveness of suppression (d = 0.03), similar to distraction (d = 0.31), but lower than some other forms of reappraisal, like perspective taking (d = 0.61). However, as mentioned above, there is a very high variability between the results of particular studies (for a meta-analysis, see Kohl et al., 2012). Some results indicate that acceptance is more effective, and some indicate that it is less effective when compared to other strategies, like reappraisal (Kohl et al., 2012; Webb et al., 2012; Smoski et al., 2015). One recent study showed for example that acceptance can be ineffective on the level of emotional experience, while still successfully downregulating psychophysiological responses (Boehme et al., 2019), although not all studies led to similar findings (Kohl et al., 2012). In our view, these differences can be partially ascribed to the fact that, in various studies, qualitatively different self-regulatory strategies are activated under one joint label, acceptance. When operationalizing acceptance, researchers most often refer to ACT theory, but available studies differ in, for example, the number of ACT components that a particular self-regulation instruction addresses. ACT consists of 6 components: (1) willingness to take in emotions, (2) being present (mindfulness), (3) cognitive defusion, (4) self as a context, and (5) concentration on values and (6) commitment (Hayes et al., 1999).

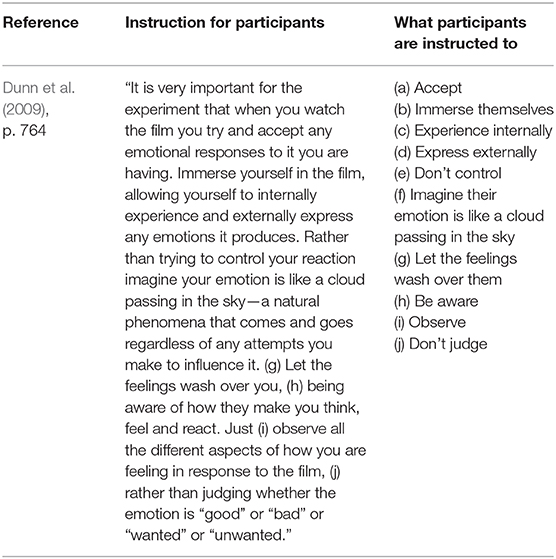

To illustrate the issue of differing operationalizations of acceptance in experiments, we can use a representative example of an instruction:

The instruction refers to two components distinguished in ACT: (1) willingness (Table 1), which is readiness and openness to fully experiencing emotion (Hayes et al., 2006) and (2) being present, which is related to concentration on the present moment (Hayes et al., 2006). Instructions based on willingness stress the lack of necessity to control, modify, or intervene in emotional processes. While when instructions refer to being present and mindfulness, participants are asked to keep their attention focused on emotions, thoughts and feelings they are experiencing at a particular moment (e.g., Segal et al., 2002; Singer and Dobson, 2007). Recent work brought the first evidence that the two described processes, willingness, and mindfulness, can have differential consequences for emotion regulation outcomes (Lindsay and Creswell, 2016). When these two components are applied in conjunction, they support effective emotion regulation; however, when mindfulness is applied without acceptance, it leads to the strengthening, and not reducing, negative emotional reactions, such as anxiety and stress (Barnes and Lynn, 2010; Desrosiers et al., 2014).

Moreover, in some of the instructions, aimed at activating acceptance in experiments, an internal monolog is encouraged and examples of self-talk are given (Singer and Dobson, 2007; Matthies et al., 2014). Others invite participants to change their attitude toward emotion and thoughts in a non-discursive manner (discursive thought is not the main tool of emotion regulation in such cases) (e.g., Wolgast et al., 2011). The distinction between discursive and non-discursive strategies seems very interesting, but it has also been completely overlooked—as of now, we do not have any studies systematically comparing these two ways of instructing emotion regulation strategies.

Another type of instruction is designed to activate the next ACT component—the process of cognitive defusion—the ability to separate from one's thoughts and emotions and allow them to come and go. Defusion's primary function is to change the status of regulated emotions instead of changing their length or strength directly. Defusion decreases the believability of private experiences, thereby decreasing reliance on and attachment to one's own emotions (Hayes et al., 2006). In some of the previous studies, cognitive defusion instruction consisted of the rapid vocal repetition of one word (e.g., “milk”), which also prevents discursive thinking and suggests that it could also be effective in dealing with self-referential negative thought (Masuda et al., 2010). In another study, participants were encouraged to disconnect their thoughts from their feelings and to notice their thoughts and feelings, but not allow them to control their behavior (Keogh et al., 2005, p. 593). In still another one, participants were taught to step back from cravings and see themselves having them (Forman et al., 2007, p. 2377). It is worth noting that the kind of diffusion that is based on stepping back from emotional experience (distancing) has been studied within another emotion management tradition: memory research (as self-distancing Ayduk and Kross, 2010; Kross and Ayduk, 2017) and within Gross's process model (as distancing; Ochsner et al., 2004). However, in research related to Gross's process model, distancing is conceptually different from acceptance as a strategy, which is another sign of the lack of conceptual clarity within the field of emotion regulation research (Ochsner et al., 2004; Webb et al., 2012).

There is also research in which another ACT process is invoked—concentration on values. In instructions that operationalize this process, participants are encouraged to be open to their experiences, while simultaneously concentrating on behavior change in valued directions (Levitt et al., 2004). This ACT component has a behavioral and evaluative element (focusing on elements of experience that are deemed to be important), which is not the case for other genres of acceptance. While this subject needs more research, we argue that this component can be viewed as assisting, but not a core element of acceptance strategy.

To sum up, even a single look at different ways of instructing acceptance as emotion regulation strategy shows that completely different processes may be activated by these different instructions, as being present, willingness, diffusion, and concentration on values are starkly different mental processes (see Kohl et al., 2012). Treating them as the same process, or mixing them within one instruction without sufficient care about their specific effects, is in our view not a useful approach and a missed opportunity to learn more about the nature of acceptance as a regulatory strategy. We postulate that to be able to more reliably study acceptance in experimental research on emotion regulation, researchers should: (1) demonstrate if various acceptance components are different or not (2) if they are—researchers should investigate the effectiveness of various acceptance components separately, as well as (3) systematically study combinations of acceptance components in a controlled way. This would give us better understanding of the mechanisms that underlie the effectiveness of acceptance.

Lastly, we wanted to highlight some additional, methodological factors that could possibly influence the results of experimental studies centered on acceptance as emotion regulation strategy. Aside from the conceptual differences in the operationalizations described above, there are also other important discrepancies between studies that are strictly methodological in nature. The acceptance instructions have different lengths, level of detail and level of complexity. Some of them include examples, metaphors or additional exercises (Gutiérrez et al., 2004; Roche et al., 2007; McMullen et al., 2008), while others do not. Sometimes, benefits of using acceptance are described in the instruction itself (so the effectiveness of the strategy is effectively primed; Levitt et al., 2004). In some studies, participants just read the instruction (Dunn et al., 2009), whereas in others they complete short practice exercises (Eifert and Heffner, 2003) or even participate in a longer training (Hayes et al., 1999). Available results suggest that acceptance requires longer training to be effective than other, simpler strategies (Baer et al., 2012; Desbordes et al., 2015), and only the participants who knew the strategy before were able to use it effectively after a short training session, to deal with the experience of pain (Blacker et al., 2012). It seems that the discussed methodological differences can have significant importance for the outcomes of the research, as they lead to differential consequences on the cognitive (e.g., the level of comprehension and memorization of instruction) as well as motivational level (e.g., willingness to apply the instruction)—however, in most research, these factors are not controlled. Additionally, recent research showed that effectiveness of emotion regulation strategies can be dependent on the specific emotion that is targeted in the regulation episode, which should be further explored in future studies (Southward et al., 2019). Also, it appears that, under particular circumstances, the use of acceptance can be greater among older adults (Allen and Windsor, 2019), so the age of participants should be systematically examined in research.

To conclude, in light of the current state of research, as well as the discussed deficiencies in knowledge on acceptance as an emotion regulation strategy, we postulate a more thorough and systematic approach to conceptualizing and studying this strategy, taking into account various and distinct acceptance components and other methodological factors that can contribute to acceptance effectiveness. We encourage researchers to pay more attention to: (1) placing acceptance in the existing emotion regulation conceptualizations, (2) controlling different components of acceptance that are activated through instructions, and (3) the issue of training (and its length) of the strategy in the course of a study.

Author Contributions

AW came with the idea for the paper and prepared the outline. AW and DK prepared the literature review. All three authors participated in preparing the first and second draft of the manuscript.

Funding

The involvement of AW in the preparation of this article was supported by the National Science Centre 2017/01/X/HS6/00839. The involvement of KL in the preparation of this article was supported by National Science Center grant DEC 2016/21/N/HS6/02678. DK was supported by Faculty of Psychology, University of Warsaw.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^It is noteworthy that this definition of acceptance includes two forms of acceptance: of the situation and of emotions. The articles on acceptance rarely contain clear definition of this strategy, sometimes they even don't contain definition at all (Hayes, 2004; Aldao et al., 2010; Kohl et al., 2012). Research usually concerns only the first form (acceptance of emotions).

References

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., and Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30, 217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004

Allen, V. C., and Windsor, T. D. (2019). Age differences in the use of emotion regulation strategies derived from the process model of emotion regulation: a systematic review. Aging Ment. Health 23, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1396575

Ayduk, O., and Kross, E. (2010). From a distance: implications of spontaneous self-distancing for adaptive self-reflection. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 98, 809–829. doi: 10.1037/a0019205

Baer, R. A., Carmody, J., and Hunsinger, M. (2012). Weekly change in mindfulness and perceived stress in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J. Clin. Psychol. 68, 755–765. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21865

Barnes, S. M., and Lynn, S. J. (2010). Mindfulness skills and depressive symptoms: a longitudinal study. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 30, 77–91. doi: 10.2190/IC.30.1.e

Barnes-Holmes, Y., Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D., and Roche, B. (2001). “Relational frame theory: a post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition,” in Advances in Child Development and Behavior, Vol. 28, eds H. W. Reese & R. Kail (New York, NY: Academic), 101–138. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2407(02)80063-5

Berking, M., Wupperman, P., Reichardt, A., Pejic, T., Dippel, A., and Znoj, H. (2008). Emotion-regulation skills as a treatment target in psychotherapy. Behav. Res. Ther. 46, 1230–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.08.005

Blacker, K. J., Herbert, J. D., Forman, E. M., and Kounios, J. (2012). Acceptance-versus change-based pain management: the role of psychological acceptance. Behav. Modif. 36, 37–48. doi: 10.1177/0145445511420281

Boehme, S., Biehl, S. C., and Mühlberger, A. (2019). Effects of differential strategies of emotion regulation. Brain Sci. 9:225. doi: 10.3390/brainsci9090225

Bowen, S., Chawla, N., and Marlatt, G. A. (2011). Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention for Addictive Behaviors: A Clinician's Guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Edn. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Haller, H., Langhorst, J., and Dobos, G. (2016). Mindfulness-and acceptance-based interventions for psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 5, 30–43. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2015.083

Desbordes, G., Gard, T., Hoge, E. A., Hölzel, B. K., Kerr, C., Lazar, S. W., et al. (2015). Moving beyond mindfulness: defining equanimity as an outcome measure in meditation and contemplative research. Mindfulness 6, 356–372. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0269-8

Desrosiers, A., Vine, V., Curtiss, J., and Klemanski, D. H. (2014). Observing nonreactively: a conditional process model linking mindfulness facets, cognitive emotion regulation strategies, and depression and anxiety symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 165, 31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.024

Dunn, B. D., Billotti, D., Murphy, V., and Dalgleish, T. (2009). The consequences of effortful emotion regulation when processing distressing material: a comparison of suppression and acceptance. Behav. Res. Ther. 47, 761–773. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.05.007

Eifert, G. H., and Heffner, M. (2003). The effects of acceptance versus contexts on avoidance of panic-related symptoms. J. Behav. Therapy Exp. Psychiatry 34, 293–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2003.11.001

Feliu-Soler, A., Montesinos, F., Gutiérrez-Martínez, O., Scott, W., McCracken, L. M., and Luciano, J. V. (2018). Current status of acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a narrative review. J. Pain Res. 11:2145. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S144631

Forman, E. M., Hoffman, K. L., McGrath, K. B., Herbert, J. D., Brandsma, L. L., and Lowe, M. R. (2007). A comparison of acceptance- and -based strategies for coping with food cravings: an analog study. Behav. Res. Ther. 45, 2372–2386. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.004

Gratz, K. L., and Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 26, 41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2, 271–299. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

Gross, J. J. (2015). The extended process model of emotion regulation: elaborations, applications, and future directions. Psychol. Inq. 26, 130–137. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2015.989751

Gutiérrez, O., Luciano, C., Rodríguez, M., and Fink, B. C. (2004). Comparison between an acceptance based and a cognitive-based protocol for coping with pain. Behav. Ther. 35, 767–783. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80019-4

Hayes, S. C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behav. Ther. 35, 639–665. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80013-3

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., and Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 44, 1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., and Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Jansen, J. E., Gleeson, J., Bendall, S., Rice, S., and Alvarez-Jimenez, M. (2019). Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for persons with psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. S0920-9964(19)30522-5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.11.016

Keogh, E., Bond, F. W., Hanmer, R., and Tilston, J. (2005). Comparing acceptance-and -based coping instructions on the cold-pressor pain experiences of healthy men and women. Europ. J. Pain 9, 591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.12.005

Kohl, A., Rief, W., and Glombiewski, J. A. (2012). How effective are acceptance strategies? A meta-analytic review of experimental results. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 43, 988–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2012.03.004

Kross, E., and Ayduk, O. (2017). “Self-distancing: theory, research, and current directions”, in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 55, ed J. M. Olson (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 81–136. doi: 10.1016/bs.aesp.2016.10.002

Levitt, J. T., Brown, T. A., Orsillo, S. M., and Barlow, D. H. (2004). The effects of acceptance versus suppression of emotion on subjective and psychophysiological response to carbon dioxide challenge in patients with panic disorder. Behav. Ther. 35, 747–766. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80018-2

Lew-Starowicz, M., Lewczuk, K., Nowakowska, I., Kraus, S., and Gola, M. (2019). Compulsive sexual behavior and dysregulation of emotion. Sex. Med. Rev. S2050-0521(19)30103-9. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.10.003

Lindsay, E. K., and Creswell, J. D. (2016). Mechanisms of mindfulness training: Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). Clin. Psychol. Rev. 51, 48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.011

Liverant, G. I., Brown, T. A., Barlow, D. H., and Roemer, L. (2008). Emotion regulation in unipolar depression: the effects of acceptance and suppression of subjective emotional experience on the intensity and duration of sadness and negative affect. Behav. Res. Ther. 46, 1201–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.08.001

Masuda, A., Twohig, M. P., Stormo, A. R., Feinstein, A. B., Chou, Y. Y., and Wendell, J. W. (2010). The effects of cognitive defusion and thought distraction on emotional discomfort and believability of negative self-referential thoughts. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 41, 11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.08.006

Matthies, S., Philipsen, A., Lackner, H. K., Sadohara, C., and Svaldi, J. (2014). Regulation of sadness via acceptance or suppression in adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Psychiatry Res. 220, 461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.017

McMullen, J., Barnes-Holmes, D., Barnes-Holmes, Y., Stewart, I., Luciano, C., and Cochrane, A. (2008). Acceptance versus distraction: brief instructions, metaphors and exercises in increasing tolerance for self-delivered electric shocks. Behav. Res. Ther. 46, 122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.09.002

Naragon-Gainey, K., McMahon, T. P., and Chacko, T. P. (2017). The structure of common emotion regulation strategies: a meta-analytic examination. Psychol. Bull. 143, 384–427. doi: 10.1037/bul0000093

Ochsner, K. N., Ray, R. D., Cooper, J. C., Robertson, E. R., Chopra, S., Gabrieli, J. D., et al. (2004). For better or for worse: neural systems supporting the cognitive down-and up-regulation of negative emotion. Neuroimage 23, 483–499. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.030

Prefit, A. B., Cândea, D. M., and Szentagotai-Tătar, A. (2019). Emotion regulation across eating pathology: a meta-analysis. Appetite 143:104438. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104438

Roche, B., Forsyth, J. P., and Maher, E. (2007). The impact of demand characteristics on brief acceptance-and-based interventions for pain tolerance. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 14, 381–393. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2006.10.010

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., and Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Singer, A. R., and Dobson, K. S. (2007). An experimental investigation of the cognitive vulnerability to depression. Behav. Res. Ther. 45, 563–575. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.05.007

Slutsky, J., Rahl, H., Lindsay, E., and Creswell, J. D. (2017). “Mindfulness, emotion regulation, and social threat,” in Mindfulness in Social Psychology, eds E. K. Papies and J. Karremans (New York, NY: Springer Publications; Routledge), 79–93. doi: 10.4324/9781315627700-6

Smoski, M. J., Keng, S. L., Ji, J. L., Moore, T., Minkel, J., and Dichter, G. S. (2015). Neural indicators of emotion regulation via acceptance vs. reappraisal in remitted major depressive disorder. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 10, 1187–1194. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsv003

Southward, M. W., Heiy, J. E., and Cheavens, J. S. (2019). Emotions as context: do the naturalistic effects of emotion regulation strategies depend on the regulated emotion? J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 38, 451–474. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2019.38.6.451

Tighe, J., Nicholas, J., Shand, F., and Christensen, H. (2018). Efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy in reducing suicidal ideation and deliberate self-harm: systematic review. JMIR Mental Health 5:e10732. doi: 10.2196/10732

Twohig, M. P., and Levin, M. E. (2017). Acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for anxiety and depression: a review. Psychiatric Clin. 40, 751–770. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.009

Veehof, M. M., Oskam, M.-J., Schreurs, K. M. G., and Bohlemeijer, E. T. (2011). Acceptance-based intrventions for treatment of chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 152, 533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.002

Webb, T. L., Miles, E., and Sheeran, P. (2012). Dealing with feeling: a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of strategies derived from the process model of emotion regulation. Psychol. Bull. 138, 775–808. doi: 10.1037/a0027600

Williams, J. C., and Lynn, S. J. (2010). Acceptance: an historical and conceptual review. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 30, 5–56. doi: 10.2190/IC.30.1.c

Keywords: acceptance, emotion regulation strategies, instructing acceptance, experiments on emotion regulation, emotion regulation

Citation: Wojnarowska A, Kobylinska D and Lewczuk K (2020) Acceptance as an Emotion Regulation Strategy in Experimental Psychological Research: What We Know and How We Can Improve That Knowledge. Front. Psychol. 11:242. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00242

Received: 12 December 2019; Accepted: 03 February 2020;

Published: 27 February 2020.

Edited by:

Hyemin Han, University of Alabama, United StatesReviewed by:

Marta Sancho, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, SpainXianglong Zeng, Beijing Normal University, China

Copyright © 2020 Wojnarowska, Kobylinska and Lewczuk. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dorota Kobylinska, ZG9yb3Rha0Bwc3ljaC51dy5lZHUucGw=

Agnieszka Wojnarowska

Agnieszka Wojnarowska Dorota Kobylinska

Dorota Kobylinska Karol Lewczuk

Karol Lewczuk