- 1General Linguistics, Faculty for Linguistics and Literary Science, Bielefeld University, Bielefeld, Germany

- 2Linguistics & English Language, School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

In this paper we bring together the results of our research into agreement in copular clauses in four different Germanic languages—Dutch, German, Faroese, and Icelandic—in order to provide an overview of the results. These cases present a particularly interesting window into how verbal agreement operates, since there are two potential controllers of agreement, which may disagree in person and/or number (The source of the rumor BE the neighbors/you-sg/you-pl). We will show that there is variation at all levels in which nominal controls agreement: cross-linguistic, inter-speaker within a single language, and intra-speaker. We argue that our data support the following claims: (1) “Downward” agreement for person, as well as number, with a nominal that is not in the canonical subject position is possible and in some cases preferred; (2) The agreement patterns observed in Icelandic and Faroese support the hypothesis that in these languages there are distinct Number and Person heads; (3) “Downward” agreement from a high position in the left-periphery is a grammatically distinct phenomenon from agreement when the verb remains in a lower position in the clause; (4) In some languages and some configurations, speakers show a significant degree of indeterminacy in their judgments and production, suggesting that speakers use more than one grammar. We relate our findings to current discussions in the generative literature on subject agreement and in particular differences between number and person agreement, and possible connections to restrictions on object clitics; we also discuss questions that remain open, and invite new, cross-disciplinary research.

1. Introduction

In this paper we bring together results from a series of experiments that we have conducted investigating agreement in a particular type of clause, across four Germanic languages: Dutch, German, Faroese, and Icelandic. Our investigation focusses on SPECIFICATIONAL COPULAR CLAUSES (SCCs henceforth), which feature minimally the copular verb (be in English) and two noun phrases (DPs). The definition of these clauses will be gone into in more detail below; (1) gives examples from English.

This type of clause is of interest for the syntax of agreement for various reasons. Notably, languages differ as to which of the two nominals the verb agrees with. As is suggested by the examples above, in English agreement is, to a high degree of consistency, with the leftmost/first DP (DP1); conversely, as discussed in Moro (1991, 1997), in Italian agreement is consistently with the rightmost/second DP (DP2):

While there is general consensus in the literature that English and Italian are consistently “DP1 agreement” and “DP2 agreement” languages, respectively, in the syntax of these copular clauses, in this article we show that in other languages—even those closely related to English—there is a richer and more complex pattern of variation. We give an initial illustration in (3):

First, although in non-copular clauses all of these Germanic languages typically show a pattern very like English, in which the finite verb consistently agrees with a clause-initial subject1, here we find three different agreement patterns:

1. agreement in number and person with the precopular noun phrase (DP1 agreement), as in English;

2. agreement in number and person with the post-copular noun phrase (DP2 agreement), as in Italian;

3. agreement with the post-copular noun phrase in number only (number-only DP2 agreement)—see the Icelandic example in (3d).

Second, all of the four languages that we investigated allowed at least two of these patterns, but to different extents: Icelandic and to a lesser degree Faroese show all three patterns; Dutch only shows DP1 and DP2 agreement; and German almost categorically requires full DP2 agreement in all but one context. Third, all four languages—even German, which as just stated is almost categorical in the preference for DP2 agreement—show a notable shift toward DP1 agreement in one particular syntactic context, when the copula precedes both DPs, as in (4):

SCCs in these languages thus provide an interesting testbed for theories of agreement; in particular, for theories which predict severe restrictions on agreement with “low” nominative arguments, i.e., nominative arguments that appear in a position lower than the canonical subject position. They also present a new, relatively unstudied set of cases of agreement variability. In this paper we bring together the results from a series of experimental studies to give an overview of the generalizations that have emerged, and to relate these results to current theories of agreement. While the details of the goals and results of the individual experiments are available in a number of different papers, our aim here is to summarize the results, show the emerging overall picture and relate our findings to current issues discussed in the syntax of copular clauses and agreement. Our hope is that this will facilitate interdisciplinary discussion of the issues raised. Throughout, we will provide the references to papers where more detailed descriptions of experiments have been reported.

In section 2, we will outline some current issues in the syntax of agreement that are relevant to, and we hope illuminated by, our results. In section 3 we give some background on Specificational Copular Clauses and outline an argument that the agreement facts support an “inversion” analysis of these clauses. With this background, in section 4 we discuss patterns that are common to all four languages, and then in section 5 we turn to the variation we find, focussing in particular on person agreement. In section 6 we briefly discuss some of the new questions that have opened up in the course of this investigation, before concluding in section 7.

2. The Syntax of Agreement: Some Background

There is a range of theories on how the sharing of features that constitutes agreement can be modeled. In current generative grammar, it is generally assumed that morphological agreement is one possible reflex of a more general syntactic relation, AGREE, that is established between a “probe” (the agreeing element, typically a head) and a “goal” (the agreement controller). There are a number of different proposals concerning the configurational relationship between the probe and the goal. (i) A longstanding position, going back at least to Chomsky (1981), but more recently championed in Koopman (2006), is that agreement holds between a head and an agreement controller in its specifier. (ii) A less constrained alternative is that Agree can be established between a probe and a c-commanding goal that may be more remote than the local specifier: see among others Wurmbrand (2012), Zeijlstra (2012), Bjorkman and Zeijlstra (2019). This is termed either “Upward Agree” or “Reverse Agree” because it reverses the hierarchical relations between probe and goal in the more widely adopted proposal of Chomsky (2000), namely that (iii) the probe must c-command the goal (“Downward Agree”). Depending on the framework and language considered, there is also work that argues for allowing both upwards and downward Agree (with upwards Agree often reducing to specifier-head agreement), see for example Béjar and Rezac (2003), Baker (2008), and Ackema and Neeleman (2018); note that for Béjar and Rezac (2003) the two types do not have equal status: upward Agree obtains only where downward Agree fails2.

In this paper we will be assuming downward Agree, for reasons that will become clearer when we have introduced the structure of copular clauses. (5) illustrates a simple case of how a downward Agree analysis handles subject-verb agreement in a non-copular sentence like John has lived in Berlin.

In this representation it is assumed that there is a single probe that has unvalued features for both person and number that will be valued by the first set of features that it encounters on a downward search of its c-command domain. Considerable work has been done on the idea that probes may be more or less specified in the features that they are searching for: e.g., a probe might be specified to match not against any person feature, but only, say, 1st or 2nd person, as proposed for Persian in Béjar and Kahnemuyipour (2017); again, we find cross-linguistic variation in this domain, see section 3.2 for further discussion.

There is now in fact a significant body of work establishing that agreement for person and agreement for number do not always behave in the same way; in some analyses it is argued that there are distinct syntactic probes, and in some cases in fact distinct heads associated with person and with number agreement. An argument for this last position is made in Sigurðsson and Holmberg (2008), based on “dative-nominative” configurations in Icelandic where there is a dative subject and a nominative argument lower in the structure. In such cases the verb may agree in number with a 3rd person nominative, as illustrated in (6a), but it cannot agree at all with a non-3rd person nominative, as illustrated in (6b)3.

Differences between number and person agreement will be discussed in more detail in section 5.

Two requirements for a successful agreement relation to be established are thus that the probe and the goal must be in the appropriate hierarchical relation to each other, and that the goal must carry the features searched for by the probe. A third requirement is that there can be no “intervening” goal: Agree must establish a match with the first appropriate set of features in its search path (assuming downward Agree, this means that it will seek to match with the highest potential goal in its c-command domain).

In the case of morphological agreement, there also seems to be a further requirement: whether or not a DP with the relevant features can in fact control agreement depends on its morphological case. At least in the Germanic languages, there is a generalization that only nominative DPs can control agreement (see Bobaljik, 2008 for discussion, but also Jónsson, 2009; Ussery, 2017 for potential counterexamples). In most configurations, the nominative argument is the structurally highest argument, so in order to see the relevance of case, we need a configuration in which the two are separated. We find such a configuration in German with a number of psych verbs that select for a dative experiencer argument and a nominative theme argument. The dative argument has been shown to be the structurally higher argument (higher before any movement has taken place, and at the point that T is merged) with such verbs like gefallen in (7) (see Lenerz, 1977; Sternefeld, 2009, p. 563), subject-verb agreement is nevertheless with the nominative argument. This shows that nominative case is a precondition for agreement in German.

The Icelandic dative-nominative construction illustrated above in (6) shows a similar effect, but in these cases it has been argued that while the dative argument does not control agreement, it does interact with the agreement probe in some way (a phenomenon referred to in the literature as “defective intervention” see among many others, Holmberg and Hróarsdóttir, 2004; Sigurðsson and Holmberg, 2008; Thráinsson et al., 2015; Ussery, 2017; Hartmann and Heycock, 2018d); we will come back to this briefly in section 5.1.

In all the discussion so far we have been considering an agreement probe associated with finite T[ense], the goal of which is a nominative noun phrase (typically the subject), which results in morphological agreement on the finite verb. While this is the most familiar instance of agreement in Germanic, it has also been observed that in some Germanic languages, agreement with the subject of a clause can additionally be related to the C[omplementizer]-position. One version of this C-agreement is that there is agreement marking on the complementizer in a number of varieties of Dutch, as illustrated in (8), from van Koppen (2005), p. 33.

We will argue in section 4.3 that C-agreement is the basis for the agreement exemplified in (4b) above. But first we need to look also at the type of copular clauses that are the focus of our investigation.

3. Specificational Copular Clauses and Agreement

3.1. Specificational Copular Clauses: Background

Copular clauses may have various syntactic types of phrase in nonsubject position, including Adjective Phrases, as in (9a), Prepositional Phrases, as in (9b), among others.

However, the case that is of interest to us here is that of “binominal” copular clauses, where both of the phrases that accompany the copular verb are nominals. Such binominal copular clauses have been further subclassified, the most influential classification being the four-way scheme set out in Higgins (1979) and illustrated in (10).

There is a substantial literature on copular clauses: for recent discussion and extensive references to other work, we refer the reader to den Dikken (2006b), Mikkelsen (2011), and Heycock (in press). Here we simply present a brief summary of some relevant distinctions from that literature.

The hallmark of predicational copular clauses like (10a) is that the pre-copular noun phrase, Sarah in (10a), is assigned the property described by the post-copular noun phrase, a genius/the winner in (10a). The post-copular noun phrase does not introduce a referent, even when it is definite (see Coppock and Beaver, 2015 for a recent discussion of the use of definite nominals as predicates). A syntactic diagnostic for predicative copular clauses in English that is often appealed to is that the same predication is felicitous in a small clause, without any instance of the copula:

In equative/equational binominal sentences like (10b), two individuals are “equated”; put differently, the two descriptions are asserted to pick out the same referent. Such cases generally cannot appear in small clauses:

The ungrammaticality of examples like (12a), while frequently cited as following from the status of the small clause as an equative, is however already predicted by the fact that consider is a verb that requires its argument proposition to be open to subjective assessment (Saebø, 2009), and presumably being identical to another entity is not even coercible into a subjective predicate. Absolute adjuncts introduced by with are not subject to the same restriction, so that the ungrammaticality of (12b) does not suffer from the same confound4.

The third class, identificational copular clauses, illustrated in (10c), have a deictic expression as the first nominal and some referring expression (whether a name or a definite) as the second. There is some discussion in the literature as to whether such sentences should rather be subsumed into one of the other classes; see Partee (1986), Huber (2002), Mikkelsen (2005), Heller and Wolter (2008), and Moltmann (2013) for discussion.

The fourth class are specificational copular clauses (SCCs). This is the type that is our primary focus in this paper. One example was already given in (10d) above, some more are given in (13):

SCCs typically have a definite description as the first nominal, and some referring expression as the second. Since many definite nominals are ambiguous between a predicational and a referential reading, many sentences are ambiguous between a predicational and a specificational reading. Such sentences can give a sense of the kind of interpretation associated with “specification.” Consider for example (14):

On the predicational reading, the sentence is a natural answer to the question Has your favorite horse just won that race, or has it lost? On the specificational reading, it is a natural answer to the question Which horse do you like best, the one that won or the one that lost? The predicational reading can be forced by adding a proper name as an apposition to the first DP:

Equally, the specificational reading can be forced by a proper name in apposition to the second DP

It is important to observe that in SCCs, at least in Germanic, the first DP occupies the canonical subject position, rather than some topic position high in the left periphery. Thus, for example, the subject of an SCC can immediately follow the auxiliary in a root polar interrogative in English:

This distinguishes SCCs from cases that have been described in the literature as A′ predicate fronting, of the kind discussed in Birner (1992) and illustrated in the second sentence in (18) (the introductory sentence is included just to provide a favoring environment), where the same diagnostic indicates that the initial phrase does not occupy the canonical subject position. For extended discussion of the contrast between SCCs and A′ predicate fronting, see Heycock and Kroch (1998).

Although, as just discussed, the first DP in an SCC does not occupy some peripheral “topic” position, one of the best-known characteristics of SCCs is that they nevertheless have a fixed information structure. In particular, the second DP has to be in focus (Heggie, 1988). The following exemplification is from Heycock (1994). First, we see that the same predicative copular sentence can be used felicitously in both (20) and (21), where the questions set up either the first DP or the second as the focus in the answer:

In contrast, the specificational sentence is good in only one of these two contexts, where the focus is on the postcopular constituent.

For experimental evidence of this restriction that makes use of the prosodic contours associated with focus, see Hartmann (2019).

A typical characterization of specificational sentences is that the first nominal, although in the canonical subject position, does not have a simple referential reading (of type e). In cases where this nominal could in principle pick out an animate entity, this can be seen by the pronoun used to refer back to it. Thus, while normally the best candidate would have to be referred back to by a gendered pronoun if it picks out a human candidate, this is not the case when it appears as the subject of a specificational copular sentence (Mikkelsen, 2005; Heycock, 2012):

While there is general agreement in the literature that the second nominal in an SCC denotes an individual (in contrast to a predicational copular sentence), and that the first nominal does not, there is less consensus concerning the denotation of the first, and this relates closely to the analyses that different researchers have put forward. One widely-adopted proposal (see among others, Heggie, 1988; Moro, 1991, 1997; Mikkelsen, 2005; den Dikken, 2006a) is that the initial nominal is in fact a predicate (type <e,t>), and that specificational sentences are derived when the predicate, rather than the subject, of a small clause complement to the copula moves into the matrix subject position, as schematized in (25b). “F” is whatever functional head is taken to project the small clause; for most of the writers above it can be taken to be something akin to Bowers' (1993) Pr[edicative]P.

An alternative proposal for the interpretation of the initial nominal is that it is a concealed question, an interpretation available to definite descriptions in cases like (26) (Romero, 2005; Heycock, 2012):

This proposal is still compatible with the syntactic “inversion” analysis schematized in (25), as a concealed question denotation can be shifted into a predicative interpretation (in the sense that it can combine with an argument of type e to yield a proposition) just like other definite descriptions, as discussed in Heycock (2012). The possibility of inversion will be important in the discussion to follow, but the precise nature of the semantic contribution of the first nominal will not be important here, so we will not be discussing it further.

Note that all inversion accounts have to explain why the higher DP within the small clause (DP2) does not “intervene” to block movement of the lower, preventing the inversion. There have been a number of proposals for how this problem could be circumvented. The essence of the proposal in den Dikken (2006a) is that the head of the small clause moves to adjoin to the copula be, and that this head-movement has the effect of making the two DPs within the small clause “equidistant” from a probe above. For Mikkelsen (2005), Shlonsky and Rizzi (2018), and Hartmann (2016) what is crucial is an informational asymmetry between the two DPs in a specificational sentence. As mentioned briefly above, specificational sentences are unusual in that they have a restricted type of information structure. We have followed the characterization of this as being a requirement that DP2 is in focus; this is the characterization that Shlonsky and Rizzi assume as well. An alternative characterization, adopted in Mikkelsen (2005), is that DP1 has to be a topic. Mikkelsen capitalizes on the informational asymmetry by proposing that the agreement probe on T may optionally carry a [+Topic] feature. If it does, and if in addition the lower of the two DPs (DP1) carries such a feature, then it may move past the higher DP (DP2), simply because that DP cannot match the probe. Shlonsky and Rizzi (2018), on the other hand, argue that DP2 in a specificational sentence moves to a low Focus position at the edge of the VP. In their terms, this is a “criterial position,” from which further movement is impossible (a case of “criterial freezing”). The remnant small clause may then move, stranding the focus to its right, and “smuggling” with it the lower DP, which subsequently moves out of it. In this paper we will assume that it is indeed the information structural asymmetry that is crucial in allowing the lower DP within the small clause to cross the higher, we will not discuss further the exact mechanism, but see Hartmann (2016, 2019) for a proposal.

There are a number of criteria that have been used as diagnostics for SCCs: as well as the distinctive pronominalization pattern for apparently animate nominals in initial position, illustrated in (24) above; these include restrictions on A′-extraction and obligatory focus on the second nominal (see Higgins, 1979; den Dikken, 2006b; Moro, 2006 for overviews and references). For the purposes of our studies, we operationalized the category of specificational copular clause as follows:

Clearly this operationalization would include some sentences that are at least ambiguous between specificational and predicational readings, as (14) above was. See section 3.3 for some detail concerning our strategies for avoiding such potential ambiguities in our materials.

3.2. Agreement in SCCs

The important work on specificational sentences in Moro (1991, 1997) showed that SCCs have different agreement properties in English and in Italian, as mentioned in the introduction. Essentially, in English agreement in SCCs is with the linearly leftmost/first/precopular overt nominal (DP1 henceforth), as illustrated in (1) above, repeated here as (28)5.

Note that, whether DP1s in specificational sentences are concealed questions or predicates, in either case they are predicted to be limited to 3rd person. They may be singular or plural, as just illustrated. In a specificational clause, if DP1 is singular, DP2 can be either singular or plural, and of any person. However, if DP1 is plural, the linearly rightmost/last/postcopular nominal (DP2) is again free to be of any person, but can typically only be plural, as in (28c,d)6. Evidently this restricts the types of potential agreement “mismatch” that can be constructed with this kind of specificational sentence. It should be noted, nevertheless, that the ungrammaticality of (28c,d) with singular agreement suggests strongly that the 3rd singular agreement in (28a,b) is controlled by DP1; if it were simply default agreement, the same 3rd singular agreement would be predicted to be acceptable in (28c,d), contrary to fact. We will return to this point in section 4.2.

The agreement pattern in Italian is different, as Moro argued: it is with DP2. This holds true both of number and person agreement. We repeat here the examples given earlier, which are adapted from those in Moro (1997), Ch. 1.

Moro (1997) derived this difference between English and Italian from the pro-drop character of the latter language. However, it has been known for some time that this cannot be the whole story. As pointed out in den Dikken (1998), Dutch allows DP2 agreement despite being a non-pro-drop language, and the same is true of German, which allows DP2 agreement even more freely (examples discussed for German go back at least as far as Berg, 1998).

If Dutch and German were invariant DP2 agreement languages (the characterization that Moro assumes for Italian), and English an invariant DP1 agreement language, one might pursue the idea that the difference in agreement is determined by the case properties of the languages. In Italian, Dutch, and German, both DPs in a finite specificational clause are nominative (in Dutch and Italian this is only evident when DP2 is a pronoun, since there is no overt morphological case marking on non-pronominal DPs in these languages). In Present Day English, on the other hand, where DP2 is a pronoun that is not syncretic for case, it is evident that it has to be accusative7:

As discussed in the last section, in all the Germanic languages, only nominative DPs can control morphological agreement on the finite verb. Given that postcopular DPs in English specificational sentences are accusative (for whatever reason), this precludes the possibility of the verb agreeing with them. It might then be possible to set up a system that makes DP2 the first candidate for controlling agreement for some structural reason. In Italian, Dutch, and German the search for an agreement controller would stop there, yielding DP2 agreement; in English however, since DP2 agreement would be precluded by the accusative case, some mechanism could allow the search to continue, to find the nominative DP1 and agree with that.

However, Fischer (2003) established already that Dutch at least is not an “invariant DP2 agreement language.” Rather, there is significant inter- and intra-speaker variation between DP1 and DP2 agreement in this language even in SCCs, where DP2 is invariantly nominative. One of the goals of our work on agreement in SCCs in Germanic, then, has been to look in detail at four languages that all have nominative DP2 in SCCs: first to establish what the agreement patterns are in a number of configurations, and then to work toward an analysis that could explain the patterns observed. The languages that we chose to investigate are German, Dutch, Icelandic, and Faroese. All four are Verb Second (V2) languages, as will be discussed further below. German and Dutch have SOV order in subordinate clauses, while Icelandic and Faroese, like the other Scandinavian languages have SVO. All four languages show morphological agreement on the copula (unlike a number of other Germanic languages, including Afrikaans and the standard varieties of all the other Scandinavian languages), but German and Icelandic have “richer” (less syncretic) agreement morphology than Dutch and Faroese.

One possible line of analysis for the difference between DP1 and DP2 agreement in specificational sentences is developed in Béjar and Kahnemuyipour (2017, 2018). These authors adopt the kind of inversion analysis discussed above, according to which DP1 in a specificational sentence originates in the lower position within a small clause. However, rather than assuming that DP1 moves directly from this position to Spec,TP [as sketched in (25) above], they adopt the proposal that DP1 in a specificational sentence always moves initially to a position below T, which they take to be the locus of the agreement probe. They do not discuss the specifics of this position, but it seems that for the purpose of discussion we can identify it with Spec,vP:

Given this derivation, DP1 in a specificational sentence, just like DP1 in a predicational sentence, will always be the first DP found by the agreement probe on T. The crucial extra assumption that Béjar and Kahnemuyipour (2017) make is that in a specificational sentence DP1 is deficient in ϕ-features. DP2 agreement then arises if a language has a probe that is searching for the feature(s) that DP1 lacks; such a probe will “skip” DP1 and hence be able to find and Agree with DP2. On the other hand, if a language has a sufficiently underspecified, and hence “undiscriminating” probe, it will match against DP1 and so agreement with DP2 will be blocked. In Béjar and Kahnemuyipour (2018) it is proposed that DP1 in a specificational sentence is deficient in that it lacks person features. Note that this lack of person cannot be common to all non-pronominal DPs, as it must distinguish between specificational subjects (which by hypothesis are skipped by a probe that is searching for person) and “ordinary” DPs occurring, say, as the subjects of predicational sentences (which are not skipped). Under this kind of analysis, variation between DP1 and DP2 agreement in a single language presumably reflects multiple options for the type of probe available (assuming, as is surely the case, that postulating variation in the ϕ-features of DP1 would be highly undesirable).

An alternative approach, which we have outlined in Hartmann and Heycock (2016, 2017) and follow-up work, is to propose that DP1 may fail to be agreed with in a specificational structure not because it is ϕ-deficient, but because in some languages it is possible for DP1 to reach a position above the agreement probe directly from its position within the small clause. Thus, while a derivation such as that in (31) will result in DP1 agreement, in some languages the derivation illustrated in (32) is possible:

Assuming downward Agree, the highest DP within the c-command domain of T is DP2 (Sarah): this then predicts that agreement will hold between T and DP2. In DP1's base position it will not be found by the agreement probe because DP2 is closer to that probe; and in its derived position it is above the probe, and hence not in a position for Downward Agree to reach it.

Under this view, rather than a difference in the ϕ-sensitivity of the probe, variation between DP1 and DP2 agreement reflects a difference in the initial landing site of DP1, possibly reflecting the presence of two distinct grammars.8 We will return to this issue after we have discussed how we have gone about trying to establish the essential facts about agreement in the languages we have been considering.

In order to begin to address the theoretical questions arising from agreement in these copular clauses, we have sought to address the following questions, which we will discuss in more detail in sections 4, 5.

The questions in (33) aim at providing the overall picture of variation with respect to the availability of DP1 and DP2 agreement in different syntactic contexts. More specifically, potential differences in DP2 agreement with respect to number vs. person are interesting in the light of recent agreement theories, where it has been argued that downwards agreement with person is more restricted than number agreement, or—depending on whether or not we are dealing with a multiple agree configuration—possibly subject to syncretism effects. For recent analyses of agreement, the availability of DP1 agreement and the lack of default agreement is relevant for a distinction between a configurational approach to agreement in SCC (as we have proposed) and an approach such as Béjar and Kahnemuyipour (2017) in which DP2 agreement is claimed to arise just when DP1 does not have any ϕ-features accessible to the probe9.

Additionally, one important point of dispute in agreement theories is whether or not person and number should be taken to be different probes or in fact distinct heads in at least some of our languages, see (33e).

3.3. Methodological Issues and Strategies

As discussed above, while earlier work on agreement in SCCs assumed that each language was of a particular “type” (requiring either DP1 or DP2 agreement), more recent work on Dutch and Faroese (Fischer, 2003; Heycock, 2009) suggested that in at least some cases there is intra-language variation of various kinds. Some of this variation is conditioned by syntactic environment (see in particular section 4.3), but some is not (or at least, not evidently). Given the possibility of inter-speaker variation, in order to understand the status of the different agreement options in a language it is essential not to rely on data from a single consultant.

In order to investigate the available patterns of number and person agreement with two nominative DPs in SCCs, we therefore conducted several experimental studies on number and person agreement in Dutch, Faroese, German and Icelandic, combining production studies (fill-in-the-blank) and rating studies (thermometer rating, following Featherston, 2008, which is a variant of the magnitude estimation technique, see Bard et al., 1996). We chose to investigate the issue using both production and rating tasks, as both have their advantages and disadvantages. A production task, such as the fill-in-the-blanks paradigm that we used, allows but does not force speakers to reflect on their own production. This method has been used in previous studies (see Berg, 1998; Fischer, 2003; Heycock, 2009). A further benefit of such a production task is that it allows for speakers to produce forms that the investigators were not previously aware of. However, the production task is to some extent a forced-choice task, in that participants are presented with a sentence in a particular order and can only choose some form to fit a single blank. Hence for example a 50/50 distribution might reflect two fully acceptable options (potentially, completely free variation between two grammatical variants) or two equally degraded options. The rating task can reveal such distinctions.

It has to be acknowledged that these experiments can only be viewed as a preliminary exploration, as there has been no prior work on this topic on Faroese and Icelandic, and little on Dutch or German. In particular, our experiments were not designed to easily reveal the extent of intra-speaker variability, since each participant saw at most 3 examples of each condition. We have made some preliminary attempts to look at individual speakers, and to establish to what extent it is possible to identify dialect splits: for this we refer the reader to Hartmann and Heycock (2017, 2018a). Further, for logistic reasons we had to conduct most of our experiments on-line, so that they had to be of limited length, and it was not possible for us to have the same participants do both the production and rating tasks. As pointed out by a referee, this is worth bearing in mind in the context of discrepancies that we found in some cases between production and rating data, discussed below.

The experiments were designed and run as parallel as possible to allow for cross-linguistic comparison of the overall patterns/effects, even though direct comparison of individual ratings and productions is not possible10. All studies were set-up online using the OnExp online software package11. Test sentences and fillers were presented one per screen in randomized orders per participants.

Participants were recruited via personal contacts for Faroese, Dutch, and Icelandic and we additionally used the mailing list “Onze Taal” for Dutch. Experiments for these three languages were run fully online. Participants could sign up to take part in a lottery for a gift voucher after having finished the online study. The studies on German were all run on-site at the University of Tübingen, with individual payment for participation. All participants had to state their mother tongue(s), we only included the data of the participants who declared themselves to be native speakers of the language we were investigating (none of the participants reported themselves as bilinguals). As the test sentences were distributed across various lists, we analyzed the data with roughly an equal number per list per experiment. Per study we had between 8 and 15 participants per list, which adds up to between 50 and 90 participants per study.

For the production studies, participants were presented with sentences with a blank in one position of the sentence, as in (34), which participants were asked to fill with a single word of their own choosing.

Before the actual study started, participants went through a short practice phase. All studies included fillers, between 1.5 and 2 times as many as the actual test sentences.

In analysing the data, we excluded all cases where participants used a verb other than the copula. All included cases were coded for number and person agreement on the copula, and then as DP1 and DP2 agreement (plus number-only DP2 agreement in Icelandic, see below). For the statistical analyses, we calculated relative frequency of DP1 agreement. These values (f) were transformed as usual, i.e., arcsine(square-root(f))—and we calculated planned contrasts with participant (F1) or item (F2) as random factors. Where appropriate, we also looked at the variation within and between speakers in more detail.

The rating studies followed the Thermometer Rating task model described in Featherston (2005), a variant of the Magnitude Estimation technique (Bard et al., 1996). Participants are asked to rate the naturalness of a sentence in relation to two reference sentences. The reference sentences are provided with a fixed score: one, a rather natural sentence, is assigned the value 30, one, a less natural sentence, is assigned the value 20. Reference sentences were kept on the screen throughout the experiment; stimulus clauses were presented one at a time, with participants advancing to the next by button press, with no possibility to return to earlier screens. Participants were asked to rate the naturalness of individual examples by providing numerical scores (all positive numbers) for individual sentences. As with the Magnitude Estimation technique, this allows participants to make finer grained judgments and to make distinctions between more or less unacceptable sentences. Before presenting the study, participants went through two short practice phases: the first one gave participants practice in assigning a value to the length of a line in reference to two standard lines assigned the values 30 and 20. Then they practiced rating naturalness with a set of sentences that varied in naturalness, so that they could familiarize themselves with the task.

The resulting scores for the rating experiments were all z-transformed (including fillers) per participant in order to normalize for the different scales participants might still have used. Z-scores were aggregated within conditions for each participant (F1) or item (F2). Where possible and useful, we computed the difference between DP1 and DP2 agreement for participants or items by subtracting DP1 z-scores from DP2 z-scores (positive values indicate that DP2 agreement is overall rated higher; negative values indicate that DP1 agreement is overall rated higher). This procedure allows us to investigate the same contrasts for the production and the rating studies. Depending on the design and more specific goals of each study, we also analyzed the rating data independently from the production data using ANOVA and mixed effect models (see the respective papers for details), especially when considering potential correlations with other factors, or speaker-groups.

All rating studies included a range of different filler sentences, including a set of standard-setting sentences, which help to put the overall acceptability into perspective (along the lines of the ideas presented in Gerbrich et al., 2019).

To test for number agreement with either DP1 or DP2 we used singular DP1 and plural DP2, corresponding to (35a)12; to test for person agreement we used singular DP1 and non-3rd person DP2, corresponding to the English example in (35b) (note that in all the Germanic languages that we investigated other than English, the pronouns for 2nd person singular and plural are distinct):

While keeping the studies in the different languages as similar as possible, we needed to make adjustments in the design of the experiments due to language specific differences in the morphology of the copula; e.g., Dutch and Faroese do not make person distinctions in the plural, while Icelandic and German do; Icelandic and German on the other hand have syncretic forms for 1/3sg (in both present and past tenses in Icelandic, only in the past tense in German). Additionally, the pronominal forms in Dutch and German have a syncretic form for 3sg feminine and 3pl (zij and sie in Dutch and German, respectively). In order to avoid ambiguity in production and rating, where we needed a 3rd person plural we could not use a pronoun in these languages but rather had to use a nonpronominal DP.

It was mentioned earlier that individual examples of binominal copular sentences—particularly taken out of context—may be ambiguous, or simply indeterminate. We note here the principal ways we sought to avoid this in our materials:

• In the experiments reported here, DP1 was usually headed by a singular non-animate abstract noun [option II.ii in (27) above] like reason/cause, problem, hope, inspiration etc.: e.g., The reason for the delay BE their friends, except when DP1 needed to be plural (which is not possible with all of these abstract nouns). In the right context it is certainly possible for speakers to use even such abstract nouns to refer to individuals in a kind of metonymy (e.g., The reason for the delay just walked into the room), so in principle a copular clause like The reason for the delay is my husband is ambiguous between a specificational reading (≈ My husband caused the delay) and a predicational one (≈ The reason for the delay is related to me by marriage), but to our ears the predicational reading is much less readily available.

• Additionally, we did carry out experiments that included conditions where DP1 was headed by a noun denoting some kind of role [the option described in II.i in (27) above], like the most likely winner(s), the only witness(es), her favorite drinking companion(s). This is the type of DP1 that seems most likely to create ambiguities, as DPs like the winner can more easily be used to refer to individuals than DPs like the problem. This “role” type of DP1 was used almost exclusively when we wanted to test the possibilities for agreement when DP1 is plural, since they are more natural in the plural than the DPs headed by many abstract nouns. For example, we take (36b) to be more natural than (37b):

In most cases where we used these “role” type DP1s, however, DP2 was a pronoun (and hence unlikely to be given a predicative interpretation, as mentioned above). Further, in our production experiments in Icelandic and German we did a direct comparison between a condition where DP1 was headed by a “role” type noun (e.g., The most likely winner ___ you.SG), and a condition where DP1 was headed by an abstract noun (e.g., The main problem ___ you.SG), and we found no difference in participants' choice of agreement on the copula in the two conditions (Hartmann and Heycock, 2017, pp. 249–261).

• In all conditions where we were testing for the distribution/acceptability of person agreement in SCCs, DP2 was a pronoun (The reason for the delay BE you). 1st and 2nd person pronouns have a predicative use only in very restricted circumstances (see e.g.,Percus and Sharvit, 2014), so all such cases are highly unlikely to get a predicational construal.

• When we were testing for the distribution/acceptability of number agreement in SCCs, DP1 was always singular and DP2 plural. This also strongly disfavors a predicational reading (and, clearly, also an equative one). Consider the examples in (38):

(38a), where both DPs are singular, can with some considerable effort get a predicational interpretation, where “the source of the rumor” is taken to be a very indirect way to describe an individual (the source of the rumor—my friend Michael—was my favorite violinist). But (38b) clearly cannot get such an interpretation: its only interpretation is as an SCC.

All four languages that we discuss are Verb Second (V2) in root clauses: thus in a root clause, the initial position is not reserved for subjects. This creates possible confounds that do not arise in English, where topicalization of a predicative NP is not string-identical to the specificational order, as show in (39)13:

We discuss in section 4.1 how we avoided this confound.

The production and rating studies on number included root clauses as well as embedded clauses in order to evaluate the possible effect of embedding (that is, of non-V2 vs. V2 structures), the experiments considering person only included embedded contexts in Icelandic, Faroese, and Dutch. In the German production study for person, we tested root clauses.

Based on our work on production of number agreement in Faroese and Icelandic (Heycock, 2009, 2012; Hartmann and Heycock, 2016, 2017), rating of person agreement in Icelandic (Hartmann and Heycock, 2018d), rating and production of person agreement in Faroese (Hartmann and Heycock, 2018e), rating and production of number agreement in Dutch and German (Hartmann and Heycock, 2018b) and rating and production of person agreement in Dutch (Hartmann and Heycock, 2019), we have arrived at the following answers to the questions raised in (33):

We will discuss the patterns (40a), (40d), and (40f) that all four languages share in section 4, and the other patterns, which we find only in a subset of the four languages, in section 5.

4. Shared Patterns of Agreement Across Dutch, Faroese, German, Icelandic

Our investigations of copular clauses in Dutch, Faroese, German and Icelandic show that all four languages share two patterns of agreement. First, all four languages allow agreement with DP2 both in V2 clauses, but also—more significantly, given the issues of ambiguity in V2 structures outlined in the last section—in non-V2 contexts. None of the languages we investigated show evidence for default agreement. Additionally, we find that all four languages show high levels of use of DP1 agreement in adjunct/modifier-initial V2 structures (that is, root clauses that have the order XP–be–DP1–DP2). We discuss the three patterns in the following subsections.

4.1. DP2 Agreement

In all four languages we found a high level of production of DP2 agreement in root (V2) clauses. When DP1 was 3rd singular and DP2 3rd plural, in German root clauses DP2 agreement was virtually categorical (92%); the lowest rate in root clauses was 62% (Dutch). DP2 agreement was also robustly attested in all four languages in embedded clauses, although at lower rates for all but Dutch, ranging from 88% for German to 46% for Faroese14.

The possibility of DP2 agreement is especially interesting from a theoretical point of view when it comes to person agreement: as outlined above in section 2, person agreement has been claimed to be universally restricted to be impossible downwards (see most prominently Baker's Structural Condition on Person Agreement, Baker, 2008, p. 52, discussed below in section 5.1). DP2 agreement in person in SCCs would therefore constitute an important counterexample to the universality of this claim.

In order to be able to show that agreement with DP2 is indeed downward agreement, however, we need to make sure that DP2 is indeed in a position that is below the agreement probe. This issue comes up in different environments in the languages we tested. As all four are V2 languages, the position of DP2 in root V2 clauses is not necessarily a position below the agreement probe: given den Besten's widely adopted analysis that V2 orders involve the verb in a high position in the left periphery (e.g., the Complementizer position) and the initial XP in the specifier of that position, one derivation for a clause like German (41) would have the initial nominal topicalising from a low predicate position, and the second nominal occupying a position above the agreement probe in T.

In the example in (41) it is clear that this is not a specificational sentence, rather the initial nominal is actually a predicate that has presumably reached the initial position in the clause by A′-movement, given that it is a bare (determinerless) nominal of a type that typically cannot appear in subject position (compare for example the ungrammatical case in (42), which is unacceptable because the bare NP Ärztin cannot function as the subject of reich 'rich', just like e.g., mayor or indeed doctor in English):

The issue is potentially more complicated with the specificational structures we are dealing with, however. Because, as discussed above, definites can also get a predicative interpretation (as in e.g., Joan is the best-paid psychiatrist in Europe and its translation equivalents), root sentences corresponding to English (39b) on the one hand, which involve predicate topicalization (A′ movement) and to (39a) on the other, which instantiate a specificational structure, are string-identical in the languages we looked at.

It is however possible to establish that the DP2 agreement that we find in specificational sentences in Faroese, Icelandic, Dutch and German is not simply reducible to the result of the kind of A′ predicate fronting + V2 illustrated in (41a), although the situation is most difficult in German. The type of A′ predicate fronting just discussed is generally taken to be a root phenomenon (Heycock and Kroch, 1998; Heycock, 2012), and in a V2 language is thus expected to pattern together with V2 order. In the SOV languages Dutch and German, the embedded clauses in our materials were all verb-final, and hence unambiguously had no possible parse as embedded V2. In the SVO languages Faroese and Icelandic, embedded V2 has been shown to be possible in environments that allow “embedded root phenomena,” but it is not freely available across all clause types. In order to avoid the confound of a parse as embedded V2, our materials therefore had the copular clause as an embedded interrogative (introduced by the equivalent of whether), as interrogatives are known to be the least favorable environment for embedded V2 (see e.g.,Thráinsson, 2007 p. 44 for Icelandic, Heycock et al., 2010 for Faroese and Icelandic). In some of our experiments/conditions for Faroese and Icelandic we added a further control, namely the inclusion of sentential negation. As discussed extensively in Mikkelsen (2002) for Danish, negation in Faroese and Icelandic occupies a position somewhere at or just above the left edge of the VP. Hence, if DP2 follows negation, it must be in a low position, not in the specifier of TP. We tested the influence of negation in the Faroese and Dutch production studies, with the result that negation did not affect agreement patterns (see Hartmann and Heycock, 2018e, 2019 for details), supporting the assumption that in these embedded clauses the first DP below the complementizer is indeed parsed as the subject, and DP2 as occupying a lower position15. We did not include negation in all of our experiments/conditions, since the examples were already fairly complex and adding negation to the interrogative adds further complexity.

While, as mentioned above, it is straightforward in the SOV languages Dutch and German to construct clauses that are unambiguously non-V2, these languages present a different issues in that they both, in some circumstances, allow “scrambling” to front a constituent all the way to the left of a subject in an embedded clause, and it has been argued that such scrambling is also an instance of A′ movement (see Neeleman and van de Koot, 2002, 2008; Grewendorf, 2005; Frey, 2010 for discussion and references). For these two languages, then, such a derivation might potentially be another confound. In Dutch this is not a serious concern. Such scrambling is much more restricted than in German: this kind of A′-scrambling requires a very specific context and is not even accepted by all speakers (see Neeleman and van de Koot, 2002, 2008). Additionally, in some of the conditions/experiments we added negation (which marks the edge of the VP) to further support the parse in which DP2 is in a low position. In German, scrambling of an object across a subject is more freely available than in Dutch, making a parse in which DP2 occupies the subject position (above T) with DP1 in a higher A′-position possible. In such a structure, DP2 agreement is not necessarily downwards agreement. However, A′-scrambling of a non-referential DP1 across DP2 in a copular clause is also an information-structurally restricted option even in German, i.e., it only occurs in contrastive/focus/emphasis contexts (see Frey, 2010 for discussion and references). As the sentences were presented out of the blue without such a context, it is unlikely that participants ended up analysing our test sentences as cases where a predicate has undergone A′-movement to a high position in the left periphery. Therefore, while acknowledging that we cannot completely exclude the possibility of an alternative parse, we think that DP2 agreement in German SCCs is also most plausibly taken to be an instance of downwards agreement.

In sum, we think that the materials we tested across the four languages indeed represent structures in which DP2 occurs in a position below the agreement probe. In this light let us now turn to the results.

In all four languages, in non-V2 contexts, DP2 agreement occurred (in production) and was judged relatively acceptable in the rating tasks, although as we have documented, the rates of production and the degree of acceptability was not the same across languages. We will discuss the differences in section 5 and concentrate on the shared production results here.

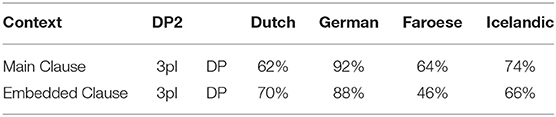

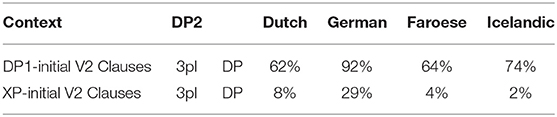

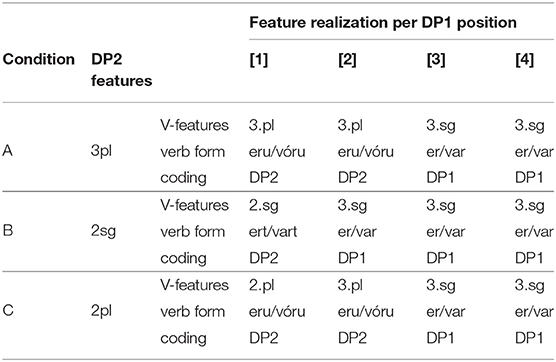

As mentioned at the beginning of this section, speakers of all four languages produced DP2 agreement when the two DPs were mismatched for number in a V2 clause like (43a). Crucially, this was also the case in embedded contexts, (43b). The rates of production for examples like (43) are given in Table 1. Note that in all the tables, where we give information about DP2, “3pl DP” means that the nominal in question is a “full” (non-pronominal) plural DP.

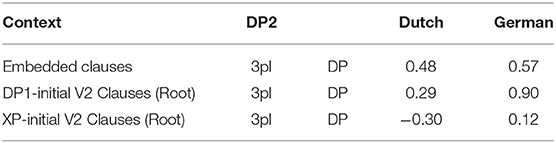

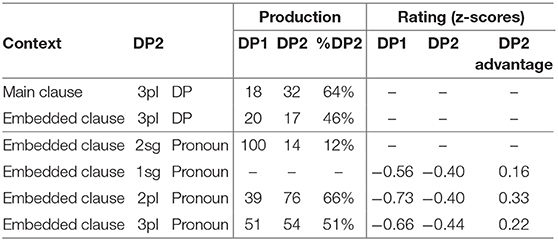

While there are differences between number and person (see section 5) all four languages also show the production of DP2 agreement when DP2 is non-third person as in (44), see Table 216.

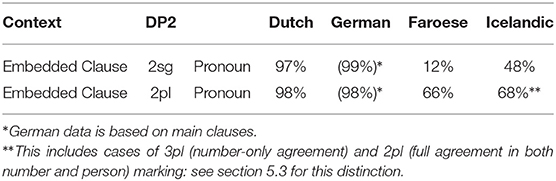

So from the production data, we conclude that DP2 agreement is a viable option for at least some speakers, in all four languages. The production data show, however, that there is significant variation with respect to the extent to which DP2 agreement is a possible or preferred option. This is also reflected in the rating data that we obtained for DP1 and DP2 agreement both for number agreement (with DP1 and DP2 differing in number only) and person agreement (where DP2 is a 1st or 2nd person pronoun). See Table 317,18. In this table we see that there are also differences between languages in the rating advantage of DP2 agreement. So while the difference in German is 0.94 in embedded clauses with 2pl pronouns, in Faroese it only reaches 0.33 for the same case. In Icelandic on the other hand, overall, speakers rated DP1 agreement higher than full agreement (in both person and number) with DP219. We nevertheless find a small group of speakers who rate DP2 agreement over DP1 agreement (see Hartmann and Heycock, 2018d), supporting the conclusion that DP2 agreement for number and person is possible for at least some varieties of Icelandic (for differences in the extent to which DP1/DP2 agreement is possible in all four languages see section 5).

Thus the rating data also illustrates our point that the languages under consideration differ in how much variation they exhibit20.

4.2. Lack of Default Agreement

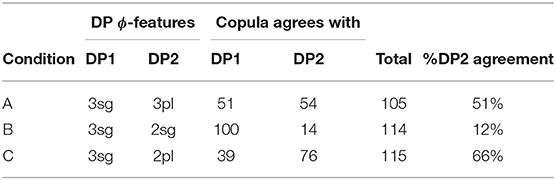

As discussed above, in a specificational sentence DP1 is always 3rd person. Because in many cases mismatches in ϕ-features can only be tested with DP1 being singular and DP2 being plural or non-3rd person, one might be tempted to analyse what we have been calling DP1 agreement rather as “default” 3rd person singular, or lack of agreement with any DP. However, there are configurations where it is possible to tease these possibilities apart. We set up such cases and found that, wherever we were able to test, default is not in fact an option in SCCs. This seems clear in English: if DP1 agreement in (45a) were default agreement, we would expect a 3sg copula also with two plural DPs, but this is sharply ungrammatical (see already Heycock, 2009 for English and Faroese).

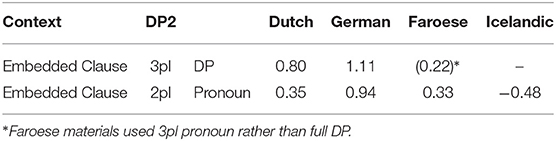

Initial informal evidence suggested already that default is not grammatical in SCCs in all the four languages in our studies. We included this configuration in our rating studies to get a value for a clearly ungrammatical agreement pattern with SCC (a baseline), see the examples in (46). The results showed indeed that default is ungrammatical: in Icelandic and Dutch default is significantly worse than any of the other conditions tested; in Faroese default is numerically but not significantly worse than DP1 agreement; in German, which is a consistent DP2 agreement language, default agreement is as bad as DP1 agreement, see Table 4, illustrated with respective examples in (46).

This further supports the conclusion from English that 3rd singular agreement with a 3rd singular DP1 is DP1 agreement, not default. Thus, any analysis in which DP1 does not have ϕ-features to be agreed with, see e.g., Béjar and Kahnemuyipour (2017), cannot be generally upheld.

4.3. DP1 Agreement in XP-Initial V2 Contexts

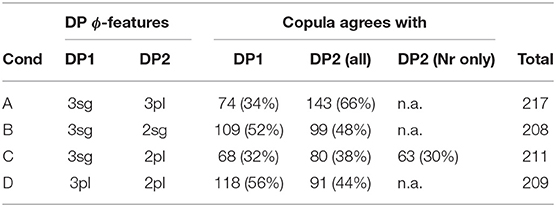

A further pattern that all four languages share is a specific effect in V2 contexts which we relate to C[omplementizer]-agreement. When considering adjunct-initial root clauses like (47) (which we will refer to as XP-initial V2 clauses in the tables below) in the four languages we discuss, we see that the production rate of DP2 agreement drops significantly in all four languages. This drop is especially striking for German, where we otherwise found a rather stable and strong preference in production for DP2 agreement across all other contexts we tested.

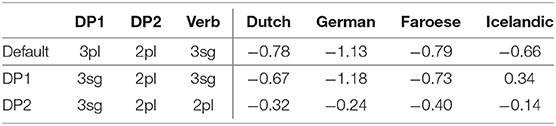

This difference also shows up in acceptability ratings, although the effect seems less dramatic, for reasons that we do not yet understand. As can be seen in Table 5, in the production data the adjunct-initial V2 order results in a “flip” from DP2 agreement to DP1 agreement being the most frequently produced order in all four languages (for all but German in fact the production of DP1 agreement in this order is close to categorical). Table 6 shows the extent to which DP2 agreement is rated higher than DP1 agreement in the judgment task in three different environments, including the adjunct-initial V2 order, In the rating data for Dutch, the “flip” in production corresponds to slightly—but significantly—higher ratings for DP1 agreement over DP2 agreement in the adjunct-initial order only. In the German rating data, the advantage of DP2 agreement in adjunct-initial root clauses is significantly reduced compared to the advantage of that agreement in embedded clauses and DP1-initial main clauses, so that in adjunct-initial V2 clauses there is no significant difference between the ratings for DP1 and DP2 agreement21.

Evidently, in these V2 languages one effect of the XP-initial order is that the order of the finite verb (in the cases we tested, always the copula itself) and the DPs becomes Vfin < DP1 < DP2. An initial hypothesis might therefore be that the increased advantage for DP1 agreement here is some kind of performance effect tied to the linear order. However, whether or not there is a performance effect contributing to the increased production/acceptability of DP1 agreement, it does not seem likely that this is an effect which produces DP1 agreement in a system in which DP1 agreement is ruled out by the syntax. This is particularly relevant for German, where our results based on other configurations suggest that DP1 agreement is essentially ungrammatical. Consider, for example, that given the relatively free word order of German, it is possible for the DP immediately following the finite verb in an XP-initial non-copular sentence to be the object, even though the “default” order would be for this position to be occupied by the subject:

As there is syncretism between feminine singular nominative and accusative, in (48b) it is only when the unambiguously nominative singular DP der Vater is reached that it becomes evident that die Tochter cannot be the subject. One can reproduce such a structure with plural noun phrases, which are equally syncretic for nominative and accusative. If there is a performance effect that induces agreement with the first DP following the finite verb in second position, we would expect to find that examples like (49) are both produced and judged grammatical:

In the judgment of the German-speaking author of this paper, (48b) rather has the effect of a garden-path sentence, and (49) is simply unacceptable. This seems quite different to what is observed with the XP-initial copular clauses with DP1 agreement.

We have therefore pursued a different approach to explaining agreement in the adjunct-initial order. Namely, we have argued that what we observe here is not regular subject-verb agreement, associated with an agreement probe in T; instead we propose that here the agreement on the verb is in fact the exponent of a probe on C, which agrees with the closest DP in its c-command domain. As mentioned above in section 2, it has been known for some time that complementizers in Germanic sometimes also carry agreement features. The case mentioned above was so-called complementizer agreement, which is particularly associated with West Germanic varieties, see Bayer (1984), Ackema and Neeleman (2004), van Koppen (2005), and van Koppen (2017) among many others. An example from a Dutch variety was given above as (8), (50) is a further example, this time from Flemish, where the complementizer dat in (50) is inflected for number and person in agreement with the subject that immediately follows it.

Note that this type of complementizer agreement only obtains when the subject immediately follows the complementizer in the linear order.

A second type of C-related agreement occurs in cases of so-called “inversion agreement” in Dutch. The distinct marking of the 2nd person singular in Standard Dutch is obligatorily omitted when the 2nd person subject immediately follows the finite verb in exactly the kind of adjunct-initial V2 structures where we find the unexpected high rates of DP1 agreement in our copular clauses (for a discussion of inversion agreement in other varieties of Dutch see Don et al., 2013 and references therein):

As just noted, both types of C-related agreement discussed in the literature only obtain when the DP immediately follows the C position (see the proposals in the literature referenced in van Koppen, 2017 on how this adjacency requirement can be implemented). This is exactly the configuration in which we found increased production/acceptability of DP1 agreement in the specificational sentences. Given this parallel behavior, we analyse the significant increase in the use/rating of DP1 agreement in SCCs when the copula has moved to C and is immediately followed by DP1 as the result of a type of inversion agreement. The agreement probe on C—to which the finite verb has moved—probes downwards and finds the closest available target, which is DP1, as in (52)22.

Thus, the agreement on the verb is the exposition of agreement of a person/number probe in the C-domain, whereas agreement in the T-domain is not expressed; here we have to assume that when both C-agreement and T-agreement conflict, but have to be realized on a single head (the verb), the conflict is resolved in favor of C agreement for most speakers23. In most of our languages this C-agreement is not usually visible, because in most sentences no differences between agreement in the T-domain and C-domain can arise with usually only a single nominative argument being present, see Hartmann and Heycock (2018b) for details.

5. Fine-Grained Differences: Number vs. Person

5.1. Background on Person vs. Number Agreement

Work on agreement especially in the last 15 years has drawn attention to the fact that agreement for person and agreement for number are not fully parallel. This topic is explored in depth in Baker (2008), Preminger (2011), Preminger (2014), and Ackema and Neeleman (2018) among many others (see in particular the references in Ackema and Neeleman, 2018). In general, person agreement is more restricted (in the terms of Baker, 2008 more “fragile”) than number agreement. In the Germanic family that we are concerned with here, the most prominent case comes from Icelandic. As mentioned earlier, Icelandic has a number of verbs whose subject has to appear with dative case-marking24. Some of these verbs are transitive, and have their lower argument appear in the nominative case; another class consists of verbs that select for non-finite clauses of one type or another, with the subject of the embedded non-finite clause again appearing in the nominative. Strikingly, the finite verb may agree in number with the low nominative argument (as seen in the (a) examples), but not in person (as seen in the (b) examples).

As noted earlier with respect to (6), an additional complexity here is that “default” 3rd singular agreement rescues examples like (53b), where the nominative argument is not an argument of the higher clause, but does not have the same effect—at least for many speakers—on examples like (54b):

There are a range of suggestions as to how to account for such restrictions in general, and the Icelandic case in particular. One prominent approach is that of Baker (2008), where it is claimed that while number agreement can obtain “at a distance,” this is ruled out for person agreement, which can only be established via a specifier-head relation, as expressed more formally in the SCOPA:

An alternative family of proposals relates the “person effect” seen in this configuration in Icelandic to a constraint observed in combinations of direct and indirect object clitics in a number of languages, the Person Case Constraint. This type of proposal is built on two core ideas. First, it is argued that a significant set of cases where there is a “low” 1st/2nd person argument that gives rise to ungrammaticality [including Icelandic examples like (54) and (53)], a higher argument intervenes between the agreement probe and the 1st/2nd person argument, preventing agreement from being established with that lower argument. In the case of the Icelandic dative-nominative constructions, this intervening argument is the dative DP. Second, 1st and 2nd person pronouns have the special property that they need to be licensed via agreement with a relevant probe, see Béjar (2003) and Béjar and Rezac (2003) for key proposals, and Preminger (2014) for a recent discussion of Icelandic cases like the ones just presented. This special property of 1st/2nd person pronouns is summed up in the Person Licensing Condition (PLC) of Béjar and Rezac (2003).

This formulation is subsequently amended in Preminger (2011) to exempt person features in clauses—even small clauses—without person ϕ-probes, precisely to account for the grammaticality of examples like (55a):

The net effect is that when some nominal intervenes between an agreement probe on some functional category and a 1st or 2nd person pronoun, the probe will fail to “reach” the pronoun (intervention) and the resultant lack of agreement will be fatal (PLC). More has to be said about why agreement for number with a “low” nominal (3rd person pronoun or nonpronominal DP) is possible even in the presence of an apparent intervenor; we leave this aside here, but see the cited works for details.

A third option for deriving the restrictions on person agreement also relies on the fact that such cases involve an “intervening” nominal, but assumes that agreement can be established with both DPs in such cases (“multiple agreement”). Ungrammaticality arises if there is no possible morphological exponent that is consistent with both of the agreement features that are copied onto the agreeing head. Thus it is argued that in (54b) and (53b) the dative argument triggers default (3rd person) agreement, and the nominative triggers 2nd or 1st person, respectively. The resulting conflict in feature values can however be resolved if there is a morphological form that happens to be syncretic for the two distinct values. Thus for example (59) is argued to be grammatical in Sigurðsson and Holmberg (2008) because for the verb virðast ‘seem' there is syncretism in the plural between 2nd and 3rd person:

See Schütze (2003) (based on data from Sigurðsson, 1996) and Sigurðsson and Holmberg (2008) and Ackema and Neeleman (2018) for this kind of proposal for Icelandic Dative-Nominative structures25.

All the proposals just listed have been argued to be general restrictions on person agreement. It then becomes relevant to ask whether their effects are evident also in SCCs—and not only in Icelandic. That is, we might expect that agreement with DP2 should be possible only for number, and not person; and that failure to agree with a 1st or 2nd person DP2 should result in ungrammaticality. And indeed such a claim is made for Dutch in den Dikken (2019), on the basis of his own judgments. However, our data suggest that other Dutch speakers show a different effect, as will be made clear in the next sections.

5.2. Person Agreement in SCCs

First, as reported above in Table 2, DP2 agreement in person is produced in all four languages, though to varying degrees.

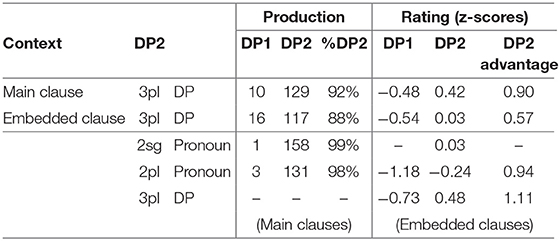

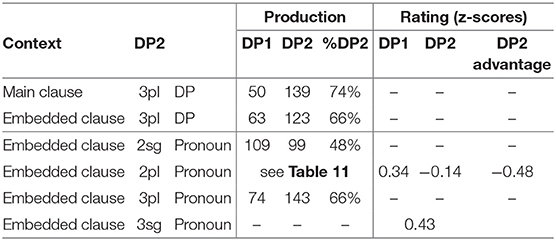

German is in general quite consistent in having agreement with DP2, as shown in Table 726. In addition, the rating data show a consistent overall higher rating for DP2 agreement in this language27.

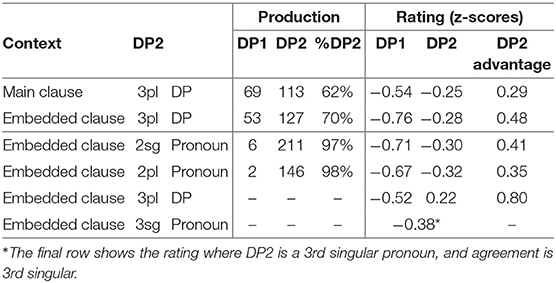

Dutch is clearly different from German in a number of respects: see Table 8. Observe that more Dutch speakers than German produced DP1 agreement in number (where DP2 was a plural non-pronominal DP, Dutch speakers produced DP1 agreement in 38% of root clauses, and 30% of embedded clauses; the corresponding figures for German are 8% and 12%). However, in both languages we tested embedded clauses with 2nd person pronouns (both singular and plural) as DP2: in these cases the rate of DP2 agreement in Dutch rises to match that of German. The rating studies reveal though that in Dutch ratings drop in general when DP2 is a personal pronoun, independent of whether there is syncretism with 3rd person in the verbal agreement, or indeed whether the pronoun is 2nd or 3rd person. Thus there is no difference in the ratings between the conditions in (60a) and (60b) and the very small difference to (60c) is not significant. On the other hand, there is a significant difference between the cases where DP2 is a pronoun (whether 2sg, 2pl, or 3sg) and those where it is a full DP, as in (60d). In German we also see a difference between the ratings for cases where DP2 is a full DP, and those where it is a pronoun (2sg or 2pl), with the full DP condition rated more acceptable overall. However, we do not have a direct comparison within a single experiment that compares a full DP with a third person pronoun as DP2. Thus, our data cannot be used to argue for a pronoun effect in German. Informal discussions with native speakers of German and Dutch seem to suggest that there is indeed a difference between Dutch and German in that focused pronouns in SCCs are problematic in Dutch, but not in German: this clearly requires further investigation.

Thus, in our data, Dutch DP2 agreement in SCCs exhibits a pronoun effect and there is no evidence for a person effect.

From the perspective of whether or not downwards person agreement with a low nominative is possible in these languages (contra SCOPA), we need to look at the data quite carefully, and take into consideration independently known facts about these languages. German shows DP2 agreement both with number and person. On the face of it, this looks like a clear case of downwards person agreement into the VP. However, of the languages we are considering, German has the most “free” word order within TP; most relevantly here, object pronouns generally move out of the VP to the left edge of the “middle field”, which could be—depending on the analysis of scrambling—outside the c-command domain of the agreement probe (presumably T, but see footnote 22), as in (62):

If speakers parse our copular sentences with pronominal DP2 as involving such movement, these examples would not necessarily involve agreement into the VP, and could not be used as an argument against theories that treat downwards agreement for person as impossible (as e.g., Baker's SCOPA) However, the alternative parse with the nominative DP2 in a low position is at least equally plausible: leftward movement is not obligatory, and focused pronouns in particular tend to remain within the VP. In an SCC the second DP is obligatorily focussed, so it is at the least possible that the pronominal DP2 has indeed remained in a low position. The usual way to force such a parse is to include negation, which would precede an unmoved, “low” pronominal. While we did not include negation in our materials for German, informally elicited judgments from native speakers informants suggest that the presence of negation does not affect the preference for DP2 agreement in any way.

In Dutch, the production data in Table 8 show that when presented with SCCs with a 2nd person pronoun as DP2, participants overwhelmingly chose to agree with the pronoun, regardless of whether this agreement was syncretic with 3rd person (97%–98%). Evidently, this is consistent with downwards person agreement being grammatical in this language. It is the case that, as we just saw, in Dutch, pronouns in general are less acceptable in the low position following negation and it could be objected that this production task does not allow us to determine whether speakers simply found this order unacceptable, and that they were making agreement choices for sentences that were ungrammatical for them. If we inspect the ratings data in the same table, however, we can see that while the ratings for the examples with pronouns were low, they were not at floor. Further, we find no additional effect of 1st/2nd person. That is, if there was a “person effect” on top of the pronoun effect, the ratings should be worse for 1/2 person pronouns than for 3rd person pronouns, but that is not what we see. Thus, we find no “person effect” in Dutch either, and we have evidence that person agreement with low nominatives is possible in this language.

We can strengthen this point by looking at the data in Faroese and Icelandic, in Tables 9, 10, respectively. Both languages are VO, so DP2 is clearly in a low position in the embedded interrogatives that we tested, since it follows the verb. In production in Faroese, we see that native speakers produce DP2 agreement to a significant extent (see section 5.3 below, and also Hartmann and Heycock, 2018e, for discussion of why DP2 agreement appears to be produced at an unusually low rate just when DP2 is the 2nd singular pronoun). In the rating data, we see that they in general prefer DP2 agreement over DP1 agreement, though ratings in general are rather low for SCCs with pronominal DP2. In Faroese there is some evidence that the rather low ratings when DP2 is a pronominal is not due to a person effect, since the ratings when DP2 is a 3rd person pronoun are not significantly higher than the ratings when it is 1st or 2nd person. It could be that there is a “pronoun effect”, as in Dutch, but to establish this would take further research, as the Faroese rating experiment did not include a condition with a non-pronominal DP2.

In Icelandic, we see that overall, DP2 agreement is preferred with number agreement, but not person agreement, which is also reflected in the rating data, where DP1 agreement is preferred over DP2 agreement. Despite this fact, a more detailed investigation into the data reveals is that there are still some speakers in Icelandic (though few in our sample) who consistently prefer DP2 person agreement over DP1 agreement: for this see Hartmann and Heycock (2018d).

In summary, we do not find any clear evidence in SCCs of the kind of “person effect” (ungrammaticality of “low” 1st/2nd person nominatives) that is present in Icelandic dative-nominative constructions. To the extent that these languages allow for pronouns to appear as DP2, agreement is possible regardless of person.

It is also relevant to consider the production and rating of DP1 agreement. In Icelandic, the production and grammaticality (at least for some speakers) of DP1 agreement when DP2 is a 1st or 2nd person pronoun constitutes an argument against the general applicability of the requirement for 1st/2nd person pronouns to be agreed with (the Person Licensing Condition (PLC) described in section 5.1 above). It is clear from the Icelandic data that DP1 agreement is a viable option and the preferred option for many speakers in our sample.

Finally in our data we did not find any evidence for a syncretism effect that could be taken as evidence for multiple agreement in SCCs (recall the discussion in section 5.1 of multiple agreement as an account of the person effect in dative-nominative constructions in Icelandic). In all languages we tested syncretic forms (German: 1/3 plural, Dutch 1/2/3 plural, Icelandic: 1/3 singular, Faroese: 1/2/3plural) as potentially providing evidence for multiple agree, but either we found that syncretism did not have a significant effect (German, Dutch, Icelandic) or that what looks like a syncretism effect in Faroese, akin to what is found in dative-nominative constructions in Icelandic, in fact has a ratings profile that requires a different explanation (see Hartmann and Heycock, 2018e, and below). Thus, multiple agreement does not arise where there are two nominative arguments in a single clause (though it is a viable analysis for the dative-nominative construction, as we argue in Hartmann and Heycock, 2018d)28.

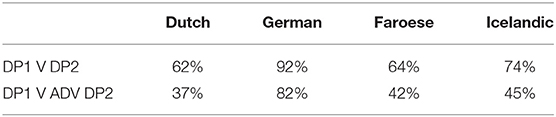

5.3. Person and Number Are Separate Probes in Icelandic and Faroese