94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 22 March 2019

Sec. Organizational Psychology

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00649

The current study aims to test a moderated-mediation model in which occupational self-efficacy determines the indirect effect of negative stereotypes about older workers in the organization both on psychological engagement in the work domain and on attitudes toward development opportunities through identification with the company. The survey involved 1,501 Italian subjects aged over 50 who were employed by a major large-scale retailer. Consistently with the Social Identity Theory and the Social Exchange Theory, results showed that the perception of negative stereotypes about older workers in the organization is associated with low identification with the company and, subsequently, with poor psychological engagement in the work domain and with attitudes indicating very little interest in development opportunities. In addition, this association was found to be stronger in older workers with higher and medium levels of occupational self-efficacy. These findings suggest that organizations should discourage the dissemination of negative stereotypes about older workers in the workplace because they may lead to older workers’ disengagement from the work domain and their loss of interest in development opportunities.

Nowadays, population aging across the Western world is increasing the need to extend the participation of older people in the labor market. However, workplaces often present a number of barriers that might strongly impact on older employees’ motivation at work, willingness to learn and intention to retire (Billett et al., 2011; Kanfer et al., 2013; Hertel et al., 2013). Specifically, the literature about occupational stress (i.e., Adams et al., 2013) reports that older workers might experience different social stressors in their work environment stemming from ageism. Ageism is the “systematic stereotyping of and discrimination against older people because they are old” (Butler, 1989, p. 139). Age stereotypes, defined as beliefs and expectations regarding a worker, based on his or her age (Hamilton and Sherman, 1994; Posthuma and Campion, 2009), generally refer negatively to older workers as poorly productive, resistant to change, unable to learn new solutions, and less healthy in comparison with younger workers (i.e., Posthuma and Campion, 2009; Ng and Feldman, 2010; Dordoni and Argentero, 2015). According to the Social Identity Theory (SIT; Tajfel and Turner, 1986), negative stereotypes could be a source of unfavorable self-evaluation (Branscombe and Ellemers, 1998), as well as a threat to people’s desire to be considered positively (Finkelstein et al., 2013). Older workers may adopt different strategies to cope with ageism: some of them are individual strategies adopted to improve the older worker’s status as an individual, and others are collective strategies to improve the status of the group of older workers as a whole (Desmette and Gaillard, 2008). In this sense, disengaging, either physically or psychologically, from their own work and organization may be considered an individual strategy that will allow older workers to re-establish the perceived integrity of self (Chasteen and Cary, 2015). In a similar vein, consistently with the norm of reciprocity formulated by the Social Exchange Theory (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005), negative age stereotypes may encourage older employees to reduce the perceived imbalance between effort and reward by decreasing engagement in the work domain and in development opportunities. The current study intends to explore the impact of negative age stereotypes on psychological engagement in the work domain and positive attitude toward development opportunities, hypothesizing a meditational effect of organizational identification moderated by occupational self-efficacy.

Employee engagement has been defined in many different ways (Saks, 2006) but, in any case, it has been found to be negatively related with age stereotypes (i.e., Gaillard and Desmette, 2008; James et al., 2013). Given that individuals express their preferred selves through work engagement (Kahn, 1990), work engagement may be influenced by the extent to which the organization is integrated into the self-definition of individuals.

Older people can adopt many coping strategies to protect their self-view from age stigma (Chasteen and Cary, 2015), indeed, according to the SIT (Tajfel and Turner, 1986), people define themselves in terms of their social group memberships striving to maintain a positive self-image. Disengagement strategies are aimed to abandon the stigmatized group or, alternatively, to psychologically escape from the stigma by reducing the centrality of the stigmatized identity to self. According to Desmette and Gaillard (2008) and Gaillard and Desmette (2008), this is what happens when older workers decide to retire in order to withdraw physically from their stigmatized group, or to psychologically disengage from their work. By detaching their self-worth from external feedback or from outcomes in the work domain, older workers make their feelings of self-worth independent from success or failure in that domain (Major and Schmader, 1998). Similarly, Gaillard and Desmette (2010) observed that older workers who were exposed to negative age-related stereotypic information were more willing to retire and less interested in learning and developing, than those who were exposed to positive age-related stereotypic information. The current study assumes that negative age stereotypes impact on psychological engagement in work domain and attitudes toward training and development because they reduce the organizational identification. Indeed, given that organizational identity is a specific form of social identity, and that organizational identification represents the strength of this identity (Haslam, 2004), we expect decreasing organizational identification to become a coping strategy against negative age stereotypes.

Scholars agree that the choice of a specific strategy to cope with stereotypes may be affected by individual attributes (i.e., Berjot and Gillet, 2011; Chasteen and Cary, 2015). In particular, self-efficacy is considered a personal resource that may facilitate dealing with potentially aversive events because it refers to the individual’s ability and willingness to exercise control (Bandura, 1977). Hence, its role in moderating the negative effect of potential work environment stressors has been the focus of interest in occupational stress literature (Stetz et al., 2006). Given that the efficacy belief system is not a global trait but a differentiated set of self-beliefs linked to distinct functional domains (Bandura, 2005), this study focuses on a domain-specific measure of self-efficacy, namely occupational self-efficacy, the competence people feel concerning their ability to successfully fulfill the tasks required by their job role (Rigotti et al., 2008). The aim is to explore the moderating role of self-efficacy in determining the adoption of a disengagement strategy in response to organizational age stereotypes. Previous studies (Fletcher et al., 1992) have provided evidence that occupational self-efficacy is more negatively related to job stress among workers aged 50 and older, than among younger workers. We expect age stereotypes to decrease organizational identification, and to subsequently reduce both psychological engagement in the work domain and positive attitudes toward development opportunities. Older workers with high occupational self-efficacy will perceive themselves as able to do their job (Schyns and Von Collani, 2002) and, consequently, they will likely feel less similar to other older employees who are stereotypically considered as ineffective at work. The perception of similarities and differences between self and other in-group members is based on self-definition as either a unique individual or as an interchangeable group member (i.e., Simon et al., 1995). Ellemers and Van Rijswijk (1997) found that perceived intragroup heterogeneity is associated with an individual response to unfavorable intergroup comparison. Consistently, people who perceive themselves as dissimilar to the stereotypical image of older workers will more likely adopt a self-protection strategy that entails decreasing their identification in an organization that is a source of negative identity.

Moreover, research indicates that individuals tend to select interactions with others who provide self-confirming feedback. It means that employees with a positive self-view will seek an organization that provides positive feedback about their performance (Swann, 1990), and they will detach from one that applies negative stereotypes about them. Finally, the moderating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between negative age stereotypes and older workers’ organizational identification is understandable in the light of the Social Exchange Theory’s perspective too. The Social Exchange Theory (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005) defines social exchanges as a series of interactions over time regulated mainly by the norm of reciprocity. Consistently, Saks (2006) argued that employees who receive socio-emotional resources from their organization to meet their social and self-esteem needs feel obliged to repay the organization with high levels of engagement. Conversely, when the organization fails to provide a good fit between socio-emotional resources and individual needs, employees are more likely to withdraw and disengage themselves from their work roles in order to restore the effort-reward balance. Thus, reciprocal interdependence provides a theoretical foundation to explain why employees become engaged in their work and organization. Obtaining affective rewards (emotional satisfaction) and supporting personal identity become more and more important during later adulthood (Carstensen, 1998; Kanfer and Ackerman, 2004). Hence, age stereotypes may create a strong misfit between older workers’ expectations to be rewarded and the actual situation in the organization (i.e., Bal et al., 2015). In line with these assumptions, Armstrong-Stassen and Ursel (2009) found that older workers who perceived that their organization valued their contribution and cared about their well-being expressed higher levels of career satisfaction and a greater intent to continue working, than those who perceived little organizational support. In a similar vein, Rabl and Triana (2013) suggested that older workers who experienced exclusion or were disadvantaged because of their age decreased their affective organizational commitment in order to minimize the net loss of resources resulting from the perceived lack of acknowledgment of personal accomplishments.

We expect a higher perception of the worker’s own value to correspond to a higher expected organizational reward. Hence, older workers who possess higher occupational self-efficacy will consider the presence of negative stereotypes that devalue older worker’s contributions to the organization a more serious violation of the norm of reciprocity, with a subsequent stronger negative effect on their identification with the company.

Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 – Occupational self-efficacy moderates the relationship between negative stereotypes about older workers and their identification with the company; therefore, the perception of negative stereotypes about older workers in the organization will be more negatively related to the identification with the company in older workers with higher self-efficacy, compared to their colleagues with lower self-efficacy.

In addition, the current study intends to explore the meditational role of organizational identification in the relationship between age stereotypes and, respectively, psychological engagement in the work domain and attitudes toward development opportunities at different levels of occupational self-efficacy. There is evidence (Murray et al., 2015; Dai and Qin, 2016) that high identifiers within the organization are more involved in achieving organizational goals by engaging with their work. There is also evidence that individuals who have a strong psychological bond with their organization are more inclined to expend their time and energies in acquiring new skills and expertise in order to contribute to the growth and development of the organization (i.e., Chughtai and Buckley, 2010). Hence, we expect that negative age stereotypes may cause psychological disengagement in the work domain and negative attitudes toward development opportunities especially in older workers with a high level of occupational self-efficacy because they will have a lower level of organizational identification.

Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 – The indirect effect of negative stereotypes about older workers on their psychological engagement in the work domain (H2a) and on their attitudes toward development opportunities (H2b) through identification with the company depends on occupational self-efficacy. Hence, for older workers with higher occupational self-efficacy, the perception of negative stereotypes about older workers in the organization will have a larger negative impact on their identification with the company and, in turn, on psychological engagement in the work domain, and on the attitudes toward development opportunities (moderated-mediation model).

The conceptual model framing the study variables in a moderated mediation relationship is reported in Figure 1.

Participants included in the study were 1,501 Italians aged over 50, employed by a supermarket chain. Overall, 559 completed the variables of interest in this study (response rate 37.24%). The age of participants was chosen based on the age interval conventionally used by studies on older workers (Zaniboni, 2015). The sample comprised 69% male workers (n = 387), and the mean age was 53.64 years (SD = 2.57; range: 50–65). Regarding the job type held by participants, 25.4% (n = 142) were office administration clerks, 64.4% (n = 371) were sales officers, and 8.2% (n = 46) did not provide this information. The average organizational tenure was 19.79 years (SD = 9.54), and 67% (n = 375) of the participants were working full time.

Data was collected through a cross-sectional self-reported survey that was distributed by e-mail. An anonymous link to the questionnaire was generated by the Qualtrics platform1 and sent by e-mail. At the same time, the e-mail informed them that participation in the survey was entirely voluntary, and that all the answers were anonymous. Given the anonymity of responses, the consent of participants was given by completing the survey after they were provided with sufficient information about the study, in accordance with the Italian privacy law. Procedural remedies were used to reduce common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Respondents were informed that there were neither right nor wrong answers, and they were asked to answer the questions as honestly as possible (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Moreover, the model included an interaction effect based on the suggestion that relations between negative stereotypes about older workers and identification with the company were different for older workers with high and low occupational self-efficacy. Thus, the hypothesized model was probably not part of the respondents’ cognitive map, and this reduced the threat of respondents “guessing” (Harrison et al., 1996; Chang et al., 2010).

We used the 13-items in an Italian version of Henkens’s (2005) scale validated by Chiesa et al. (2016). Respondents were asked to indicate to what extent they agreed with the statements presented, which referred to their organization’s negative beliefs about workers aged 50 years and older. A sample item was “My organization thinks that… older workers are less productive than younger workers.” The response scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The coefficient alpha in this study was 0.76.

We measured the perceived self-efficacy related to the work domain with the eight items of the Italian version (Di Fabio and Taralla, 2006) of the Occupational Self-Efficacy Scale (short form) (Schyns and Von Collani, 2002; Rigotti et al., 2008). A sample item was “Whatever comes my way in my job, I can usually handle it.” The original six-point response scale was adjusted into a five-point one ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (completely true). The coefficient alpha in this study was 0.87.

We adapted three items from Farth et al. (1997) to describe employees’ identification with the company, and their willingness to protect the corporate reputation by making suggestions to improve the organization’s functional features. A sample item was “I am willing to stand up to protect the reputation of the company.” Responses were obtained in addition to adapting the original seven-point scale to a five-point one where it ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The coefficient alpha in this study was 0.76.

It was measured by six items adapted from Major and Schmader (1998; Schmader et al., 2001) that refer to “a detachment of self-esteem from external feedback or outcomes in a particular domain, such as the feelings of self-worth, are not dependent on the successes or failures in that domain” (Major and Schmader, 1998; p. 220). A sample item was “Doing my job well is very important to me.” These items were rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The coefficient alpha in this study was 0.75.

We used three ad hoc items to assess the extent to which respondents evaluate the organization’s initiatives for the development older workers as useful. Participants rated their perception of the level of opportunities of “counseling for career development,” “training,” and “campaigns for recruiting older workers” on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally useless) to 5 (totally useful). The coefficient alpha in this study was 0.76.

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and alpha reliabilities of the variables are presented in Table 1. Negative stereotypes about older workers resulted in a negative correlation with occupational self-efficacy (r = -0.31, p < 0.01), identification with the company (r = -0.28, p < 0.01), psychological engagement in the work domain (r = -0.29, p < 0.01), and attitudes toward development opportunities (r = -0.18, p < 0.01). Conversely, occupational self-efficacy was positively correlated with identification with the company (r = 0.39, p < 0.01), psychological engagement in the work domain (r = 0.31, p < 0.01) and attitude toward development opportunities (r = 0.20, p < 0.01). Moreover, identification with the company was positively correlated both with psychological engagement in the work domain (r = 0.44, p < 0.01) and with attitudes toward development opportunities (r = 0.20, p < 0.01). We used the covariance matrix as input and maximum likelihood as estimation method to perform a CFA on the variables considered in our model. The CFA 1-factor model [χ2 (527) = 12530.54, p = 0.00; RMSEA = 0.16; NNFI = 0.37; CFI = 0.41] was compared to the CFA 5-factor model [χ2 (517) = 3115.67, p = 0.00; RMSEA = 0.08; NNFI = 0.82; CFI = 0.83]. The chi-square difference test was significant [Δχ2 (10) = 9414.87, p < 0.01]; thus, the model with five factors was preferred. Moreover, we used specification search (Leamer, 1978) to improve the fit of the 5-factor model. Particularly, following modification indices, some measurement errors were correlated with the scale of negative stereotypes about older workers. The modified model showed acceptable fit indices [χ2 (511) = 2073.94, p = 0.00; RMSEA = 0.06; NNFI = 0.90; CFI = 0.91].

PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2012) was used to test our moderated-mediation model where the interaction between negative stereotypes about older workers (independent variable) and occupational self-efficacy (moderator) affects identification with the company (mediator) which, in turn, affects psychological engagement in the work domain and attitudes toward development opportunities (outcomes). We specified 10,000 bootstrap samples to obtain robust estimates of standard errors and confidence intervals (Preacher et al., 2007), namely centered, independent, and moderator variables.

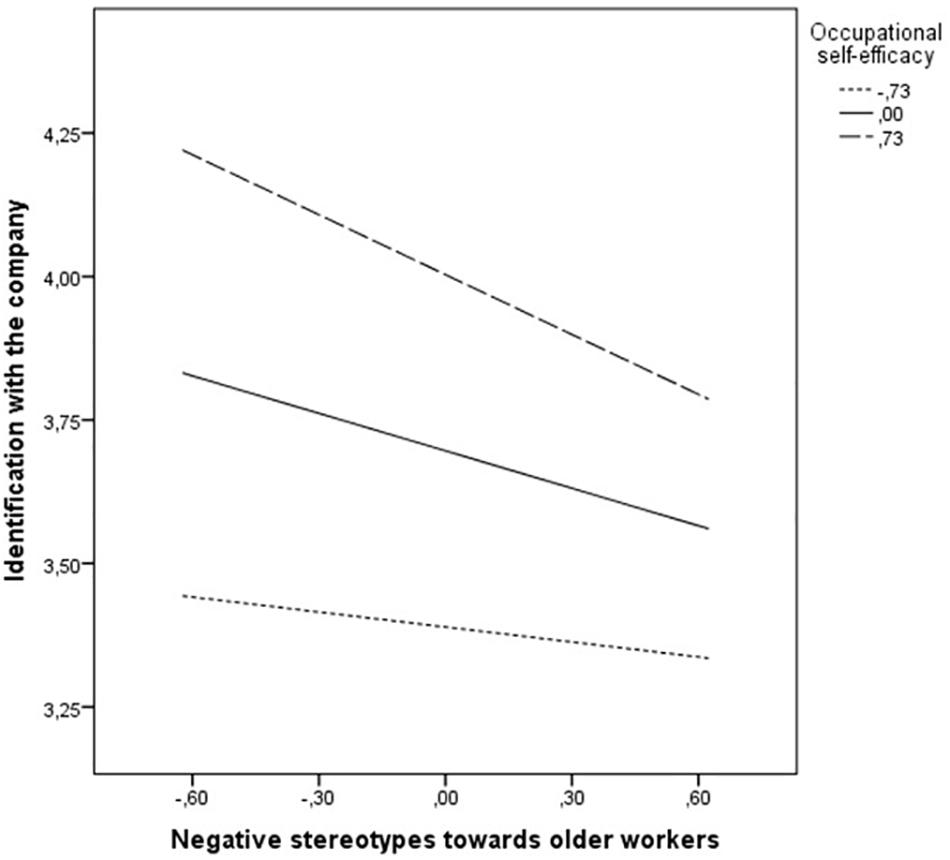

Table 2 reports the results of the moderated-mediation models tested2. Negative stereotypes about older workers (B = -0.22, p = 0.00) and the interaction between negative stereotypes about older workers and occupational self-efficacy (B = -0.18, p = 0.00) negatively affected identification with the company. Instead, occupational self-efficacy positively affected identification with the company (B = 0.42, p = 0.00). According to our Hypothesis 1, occupational self-efficacy moderated the relationship between negative stereotypes about older workers and identification with the company. Hence, the presence of negative stereotypes about older workers in the organization was more negatively related to identification with the company in older workers with higher occupational self-efficacy, compared to their colleagues with lower occupational self-efficacy. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was confirmed.

The two models of the dependent variables showed that identification with the company significantly and positively affected psychological engagement in the work domain (B = 0.41, p = 0.00) and the attitude toward development opportunities (B = 0.21, p = 0.00). According to Hypothesis 2, the indirect effects of negative stereotypes about older workers, respectively, on psychological engagement in the work domain (H2a) and on attitudes toward development opportunities (H2b) through identification with the company depended on the occupational self-efficacy level. The lower part of Table 2 reports critical values of conditional indirect effects (Hayes, 2012). Results indicate that the indirect effects of negative stereotypes about older workers on psychological engagement in the work domain and on attitudes toward development opportunities through identification with the company were significant at higher and medium levels of occupational self-efficacy. In particular, the effects were significant and negative for workers perceiving higher levels of occupational self-efficacy (for psychological engagement, -0.14, CI = [-0.21, -0.08]; for attitude toward development opportunities, -0.08, CI = [-0.14, -0.03]) and medium levels of occupational self-efficacy (for psychological engagement, -0.09, CI = [-0.14, -0.04]; for attitudes toward development opportunities, -0.05, CI = [-0.10, -0.02]). They were not significant for workers perceiving lower levels of occupational self-efficacy (for psychological engagement, -0.03, CI = [-0.12, 0.04]; for attitude toward development opportunities, -0.02, CI = [-0.07, 0.02]). Our Hypotheses 2a and 2b were thus confirmed.

Figure 2 provides more details regarding the effect of interaction between negative stereotypes about older workers and occupational self-efficacy on identification with the company, showing that the negative relationship between organizational negative stereotypes about older workers and identification with the company was stronger for higher and medium levels of occupational self-efficacy.

Figure 2. Workers’ self-efficacy and negative stereotypes toward older workers interact to affect the identification with the company. Lower occupational self-efficacy: 1 standard deviation below the mean (M – 1SD = 3.37). Medium occupational self-efficacy: the mean (M = 4.09). Higher occupational self-efficacy: 1 standard deviation above the mean (M + 1SD = 4.81).

The aim of this study was to examine a moderated-mediation model in which the indirect effect of negative stereotypes about older workers regarding their psychological engagement in the work domain and their attitudes toward development opportunities through identification with the company depend on occupational self-efficacy. Results support the hypotheses indicating that the perception of negative stereotypes about older workers in the organization is negatively associated with the identification of the company and, in turn, with psychological engagement in the work domain and with attitudes toward development opportunities. In addition, they confirm that this relationship is stronger in older workers with higher and medium levels of occupational self-efficacy.

Consistently with the SIT, which assumes that people may adopt different strategies to cope with negative stereotypes in order to protect their self-image or the overall image of their group (Desmette and Gaillard, 2008), our findings suggest that especially older workers with either medium or high levels of occupational self-efficacy are inclined to adopt a disengagement strategy that decreases organizational identification with negative consequences for psychological engagement in the work domain and for attitudes toward learning and development. This is probably due to the fact that they perceive themselves as quite dissimilar to the other older workers who are considered negatively by the organization and, therefore, they select an individual response to protect their positive sense of self. Conversely, the effect of negative age stereotypes on organizational identification is not significant for older workers with low occupational self-efficacy, perhaps because they may adopt different strategies to cope with age stereotypes.

This paper contributes to research on the Social Exchange Theory too. Our findings are of particular interest because they show the mediational effect of identification with the company in this relationship at different levels of occupational self-efficacy. As Edwards (2009) argued, employees embrace the organization’s values and goals as their own in exchange for acknowledgment of their contribution. Therefore, the presence in the workplace of negative stereotypes about older workers may be perceived as a lack of reciprocity that leads older employees to reduce their organizational identification and their investment in the work domain in order to limit the loss of resources (Rabl and Triana, 2013). This is especially true when the level of occupational self-efficacy is either medium or high because the perception of imbalance between invested and gained resources is higher in these cases.

When occupational self-efficacy was low, we did not observe any effect of negative age stereotypes on the identification with the company. Perhaps this is because our respondents justified the organization’s negative beliefs about them with their low ability to successfully fulfill the tasks required by their job. In this sense, negative age stereotypes could be considered self-confirming feedback that does not require overcoming the imbalance between efforts and rewards.

Human resources (HR) practices may offer resources and opportunities to prolong the work life of employees but, despite the increasing number of HR strategies designed to promote the use and retention of older workers, empirical evidence about their effectiveness is largely insufficient (Kooij et al., 2010). Indeed, little is known about older workers’ needs and the motives that can retain them at work. The general assumption is that people in their late careers are not likely to be thriving and their goals are less growth-oriented than younger workers’ goals. Hence, “age-friendly” HR strategies often aim to maintain older workers in their current functional level, rather than to encourage them to achieve new and challenging levels. However, recent studies have shown that older workers considered learning and development opportunities provided by the organizations as an interesting opportunity (Veth et al., 2015; Taneva et al., 2016). Our study suggests that in order to prevent disengagement from the work domain and loss of interest toward development opportunities, it is important to discourage the dissemination of negative stereotypes about older workers in the workplace. This is because the perception of an identity threat and the lack of reciprocity in the relationship with the organization may lead older workers to adopt work avoidance reactions that create a self-fulfilling prophecy for them. Despite an evident lack of studies that investigate how to decrease stereotypes about older workers in the workplace, some experimental studies suggest which kind of interventions organizations could implement to decrease older workers’ stereotypes. For example, Abrams et al. (2006) found that according to the intergroup contact theory, positive intergenerational contacts were associated with reduced prejudice and reduced in-group identification, suggesting that organizational intervention aimed to increase positive intergenerational contacts could diminish vulnerability to the stereotype threat among older people. More in general, age-inclusive HR practices demonstrated to foster the development of positive organizational age-diversity climate, which in turn is related with important outcomes as job crafting (Ingusci, 2018), company’s performance, employees’ commitment and turnover intentions (Kunze et al., 2011; Boehm et al., 2014).

Although this study makes an important contribution, it also has some limitations that future research should address. First, the data available were cross-sectional and were acquired from self-reports; hence, they may have been affected by a common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003). As suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2003), procedural remedies were used to control and counteract the common method variance. In order to reduce evaluation apprehension and prevent response distortion, respondents’ anonymity was protected with respect to their employer, respondents were advised that there were neither right nor wrong answers, and they were asked to answer questions as honestly as possible. Furthermore, the variables were measured with validated scales that have already been used in the aging research field, which can mitigate measurement error and thereby decrease common method bias (Spector, 1987). In addition, a moderated relationship was considered, reducing the threat of respondents “guessing” patterns (Harrison et al., 1996; Chang et al., 2010). Finally, the results of the confirmatory factor analysis revealed that the 5-factor model provided a significantly better fit to the data rather than the 1-factor model, which can suggest that the common method bias is not a serious concern in this study. In any case, future research should repeat the study using a longitudinal or time-lagged research design, and by gathering data from multiple sources. Second, future research should explore the possibility that other personal resources, besides self-efficacy (e.g., work ability), can moderate relations between negative stereotypes about older workers, identification with the company, psychological engagement in the work domain and attitude toward development opportunities for older workers. Moreover, considering the importance of keeping older workers at work, retirement-related outcomes (e.g., retirement intentions) should be included in future research. Furthermore, only workers from one organization participated in this study; therefore, the results should be retested with different working populations and organizations to increase the external validity of the study. Finally, the current study involved only workers aged over 50, while it could be interesting to explore generational differences, among younger, middle-aged and older workers. Especially, some recent research (Ingusci, 2018) suggested that older workers may play an important role in motivating their middle-aged colleagues, supporting them in seeking and coping with new challenges, and encouraging them to produce new ideas.

In conclusion, this study makes an important contribution by addressing a gap in research regarding the interaction between negative stereotypes about older workers in the organization and occupational self-efficacy in affecting identification with the company, psychological engagement in the work domain and attitude toward development opportunities. Specifically, we found that stereotypes about older workers are more negatively related to identification with the company and, therefore, to psychological job engagement in the work domain and to the attitude toward development opportunities when levels of occupational self-efficacy are at high and medium levels. We believe these findings have important implications for both practice and research, and we encourage future research on the relationship between age-related stereotypes, personal resources at work, and organizational and retirement outcomes in various jobs and industry types.

Ethical approval was not required for this study in accordance with the national and institutional guidelines. In fact, data for this study were collected through a self-reported survey distributed by email. Participants received an anonymous link generated by Qualtrics platform (www.qualtrics.com) to complete the questionnaire.

RC and SZ conceptualized the model and chose the theoretical framework. RC defined the tools and collected the data. SZ performed the data analyses. RC, SZ, and MV wrote the first draft of the paper. DG revised the paper. All the authors gave final approval of the paper.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abrams, D., Eller, A., and Bryant, J. (2006). An age apart: the effects of intergenerational contact and stereotype threat on performance and intergroup bias. Psychol. Aging 21, 691–702. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.4.69

Adams, G. A., DeArmond, S., Jex, S. M., and Webster, J. R. (2013). “Older workers occupational stress and safety,” in Sage Handbook of Aging, Work and Society, eds R. Burke, C. Cooper, and J. Field (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 266–282. doi: 10.4135/9781446269916.n15

Armstrong-Stassen, M., and Ursel, N. D. (2009). Perceived organizational support, career satisfaction, and the retention of older workers. J. Occupat. Organ. Psychol. 82, 201–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-8583.2007.00057.x

Bal, P. M., de Lange, A. H., Van der Heijden, B. I. J. M., Zacher, H., Oderkerk, F., and Otten, S. (2015). Young at heart, old at work? Relations between age, (meta-)stereotypes, self-categorization, and retirement attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 91, 35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.09.002

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (2005). The primacy of self-regulation in health promotion. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 54, 245–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00208.x

Berjot, S., and Gillet, N. (2011). Stress and coping with discrimination and stigmatization. Front. Psychol. 2:33. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00033

Billett, S., Dymock, D., Johnson, G., and Martin, G. (2011). Overcoming the paradox of employers’ views about older workers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 22, 1248–1261. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2011.559097

Boehm, S. A., Kunze, F., and Bruch, H. (2014). Spotlight on age-diversity climate: the impact of age-inclusive hr practices on firm-level outcomes. Pers. Psychol. 67, 667–704. doi: 10.1111/peps.12047

Branscombe, B., and Ellemers, N. (1998). “Use of individualistic and group strategies in response to perceived group-based discrimination,” in Prejudice: The Target’s Perspective, eds J. Swim and C. Stangor (New York, NY: Academic Press), 243–266.

Butler, R. (1989). Dispelling ageism: the cross-cutting intervention. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 503, 138–147. doi: 10.1177/0002716289503001011

Carstensen, L. L. (1998). “A life-span approach to social motivation,” in Motivation and Self-Regulation Across the Life Span, eds J. Heckhausen and C. S. Dweck (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 341–364. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511527869.015

Chang, S. J., van Witteloostuijn, A., and Eden, L. (2010). From the editors: common method variance in international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 41, 178–184. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2009.88

Chasteen, A. L., and Cary, L. A. (2015). “Age stereotypes and age stigma: connections to research on subjective aging,” in Research on Subjective Aging: New Developments and Future Directions. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, Vol. 35, eds M. Diehl and H. W. Wahl (New York, NY: Springer), 99–119. doi: 10.1891/0198-8794.35.99

Chiesa, R., Toderi, S., Dordoni, P., Henkens, K. Fiabane, E. M., and Setti, I. (2016). Older workers: stereotypes and occupational self-efficacy. J. Manage. Psychol. 31, 1152–1166. doi: 10.1108/JMP-11-2015-0390

Chughtai, A. A., and Buckley, F. (2010). Assessing the effects of organizational identification on in-role job performance and learning behaviour. Pers. Rev. 39, 242–258. doi: 10.1108/00483481011017444

Cropanzano, R., and Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J. Manage. 31, 874–900. doi: 10.1177/0149206305279602

Dai, K., and Qin, X. (2016). Perceived organizational support and employee engagement: based on the research of organizational identification and organizational justice. Open J. Soc. Sci. 4, 46–57. doi: 10.4236/jss.2016.412005

Desmette, D., and Gaillard, M. (2008). When a “worker” becomes an “older worker”: the effects of age-related social identity on attitudes towards retirement and work. Career Dev. Int. 13, 168–185. doi: 10.1108/13620430810860567

Di Fabio, A., and Taralla, B. (2006). L’autoefficacia in ambito organizzativo: proprietà psicometriche dell’occupational self efficacy scale (short form) in un campione di insegnanti di scuole superiori. Risorsa Uomo 12, 51–66.

Dordoni, P., and Argentero, P. (2015). When age stereotypes are employment barriers: a conceptual analysis and a literature review on older workers stereotypes. Age. Int. 40, 1–20. doi: 10.1007/s12126-015-9222-6

Edwards, M. R. (2009). HR, perceived organisational support and organisational identification: an analysis after organisational formation. Hum. Resour. Manage. J. 19, 91–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-8583.2008.00083.x

Ellemers, N., and Van Rijswijk, W. (1997). Identity needs versus social opportunities: the use of group level and individual level identity management strategies as a function of relative group size, status, and ingroup identification. Soc. Psychol. Quart. 60, 52–65. doi: 10.2307/2787011

Farth, J. L., Earley, P. C., and Lin, S. C. (1997). Impetus for extraordinary action: a cultural analysis of justice and extra-role behavior in Chinese society. Adminis. Sci. Quart. 42, 421–444. doi: 10.2307/2393733

Finkelstein, L. M., Ryan, K. M., and King, E. B. (2013). What do the young (old) people think of me? Content and accuracy of age-based metastereotypes. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 22, 633–657. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2012.673279

Fletcher, W. L., Hansson, R. O., and Bailey, L. (1992). Assessing occupational self-efficacy among middle-aged and older adults. J. Appl. Gerontol. 11, 489–501. doi: 10.1177/073346489201100408

Gaillard, M., and Desmette, D. (2008). Intergroup predictors of older workers’ attitudes towards work and early exit. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 17, 450–481. doi: 10.1080/13594320801908564

Gaillard, M., and Desmette, D. (2010). (In)validating stereotypes about older workers influences their intentions to retire early and to learn and develop. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32, 86–95. doi: 10.1080/01973530903435763

Hamilton, D. L., and Sherman, J. W. (1994). “Stereotypes,” in Handbook of Social Cognition, Applications, eds R. S. Wyer Jr. and T. K. Srull (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 1–68.

Harrison, D. A., McLaughlin, M. E., and Coalter, T. M. (1996). Context, cognition, and common method variance: psychometric and verbal protocol evidence. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 68, 246–261. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1996.0103

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling. Available at: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

Henkens, K. (2005). Stereotyping older workers and retirement: the managers’ point of view. Can. J. Aging. 24, 353–366. doi: 10.1353/cja.2006.0011

Hertel, G., van der Heijden, B. I. J. M, de Lange, A. H., and Deller, J. (2013). Facilitating age diversity in organizations – part I: challenging popular misbeliefs. J. Manage. Psychol. 28, 729–740. doi: 10.1108/JMP-07-2013-0233

Ingusci, E. (2018). Diversity climate and job crafting: the role of age. Open Psychol. J. 11, 105–111. doi: 10.2174/1874350101811010105

James, J. B., McKechnie, S. P., Swanberg, J. E., and Besen, E. (2013). Exploring the workplace impact of intentional and unintentional age discrimination. J. Manag. Psychol. 28, 907–927. doi: 10.1108/JMP-06-2013-0179

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manage. J. 33, 692–724.

Kanfer, R., and Ackerman, P. (2004). Aging, adult development, and work motivation. Acad. Manage. Rev. 29, 440-458. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2004.13670969

Kanfer, R., Beier, M., and Ackerman, P. L. (2013). Goals and motivation related to work in later adulthood: an organizing framework. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 22, 253–264. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2012.734298

Kooij, D. T. A. M., Jansen, P. G. W., Dikkers, J. S. E., and de Lange, A. H. (2010). The influence of age on the associations between HR practices and both affective commitment and job satisfaction: a meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 31, 1111–1136. doi: 10.1002/job.666

Kunze, F., Boehm, S. A., and Bruch, H. (2011). Age diversity, age discrimination climate, and performance consequences-A cross-organizational study. J. Organ. Behav. 32, 264–290. doi: 10.1002/job.698

Leamer, E. E. (1978). Specification Searches: Ad Hoc Inference with Non Experimental Data. New York, NY: Wiley.

Major, B., and Schmader, T. (1998). “Coping with stigma through psychological disengagement,” in Prejudice: The Target’s Perspective, eds J. K. Swim, and C. Stangor (New York, NY: Academic Press219–241).

Murray, M. K., Duncan, N., Pontes, H. M., and Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Organizational identification, work engagement, and job satisfaction. J. Manage. Psychol. 30, 1019–1033. doi: 10.1108/JMP-11-2013-0359

Ng, T. W. H., and Feldman, D. C. (2010). The relationship of age with job attitudes: a meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 63, 667–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01184.x

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Posthuma, R. A., and Campion, M. A. (2009). Age stereotypes in the workplace: common stereotypes, moderators and future research directions. J. Manage. 35, 158–188. doi: 10.1177/0149206308318617

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., and Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 42, 185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316

Rabl, T., and Triana, M. (2013). How German employees of different ages conserve resources: perceived age discrimination and affective organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 24, 3599–3612. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.777936

Rigotti, T., Schyns, B., and Mohr, G. (2008). A short version of the occupational self-efficacy scale: structural and construct validity across five countries. J. Career Assess. 16, 238–255. doi: 10.1177/1069072707305763

Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manage. Psychol. 21, 600–619. doi: 10.1108/02683940610690169

Schmader, T., Major, B., Eccleston, C. P., and McCoy, S. K. (2001). Devaluing domains in responses to threatening intergroup comparisons: perceived legitimacy and the status value asymmetry. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 80, 782–796. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.5.782

Schyns, B., and Von Collani, G. (2002). A new occupational self-efficacy scale and its relation to personality constructs and organizational variables. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 11, 219–241. doi: 10.1080/13594320244000148

Simon, B., Pantaleo, G., and Mummendey, A. (1995). Unique individual or interchangeable group member? The accentuation of intragroup differences versus similarities as an indicator of the individual self versus the collective self. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 69, 106–119. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.1.106

Spector, P. E. (1987). Method variance as an artifact in self-reported affect and perceptions at work: myth or significant problem? J. Appl. Psychol. 72, 438–443. doi: 10.1037//0021-9010.72.3.438

Stetz, T. A., Stetz, M. C., and Bliese, P. D. (2006). The importance of self-efficacy in the moderating effects of social support on stressor-strain relationships. Work Stress 20, 49–59. doi: 10.1080/02678370600624039

Swann, W. B. (1990). “To be adored or to be known: the interplay of self-enhancement and self-verification,” in Handbook of Motivation and Cognition, Vol. 2, eds R. M. Sorrentino and E. T. Higgins (New York: Guilford Press), 408–480.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Psychol. Intergroup Relat. 5, 7–24.

Taneva, S. K., Arnold, J., and Nicolson, R. (2016). The experience of being an older worker in an organization: a qualitative analysis. Work Aging Retire. 2, 396–414. doi: 10.1093/workar/waw011

Veth, K., Emans, B., Van der Heijden, B. I. J. M., Korzilius, H. P. L. M., and De Lange, A. H. (2015). Development (f)or maintenance? an empirical study on the use of and need for HR practices to retain older workers in health care organizations. Hum. Resour. Dev. Quart. 26, 53–80. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.21200

Keywords: older workers, age-related stereotypes, identification with the organization, occupational self-efficacy, psychological engagement, development opportunities for workers

Citation: Chiesa R, Zaniboni S, Guglielmi D and Vignoli M (2019) Coping With Negative Stereotypes Toward Older Workers: Organizational and Work-Related Outcomes. Front. Psychol. 10:649. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00649

Received: 25 April 2018; Accepted: 08 March 2019;

Published: 22 March 2019.

Edited by:

Renato Pisanti, University Niccolò Cusano, ItalyReviewed by:

Thomas Rigotti, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, GermanyCopyright © 2019 Chiesa, Zaniboni, Guglielmi and Vignoli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rita Chiesa, cml0YS5jaGllc2FAdW5pYm8uaXQ=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.