95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 14 March 2019

Sec. Organizational Psychology

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00442

This article is part of the Research Topic Police Trauma, Loss, and Resilience View all 26 articles

Values represent people’s highest priorities and are cognitive representations of basic motivations. Work values determine what is important for employees in their work and what they want to achieve in their work. Past research shows that levels of both aspects of job-related well-being, job burnout and work engagement, are related to work values. The policing profession is associated with high engagement and a risk of burnout. There is a gap in the literature regarding the hierarchy of work values in police officers, how work values are associated with job burnout and work engagement in this group, and whether work values in police officers are sensitive to different levels of job burnout and work engagement. Therefore, the aim of our study was to examine the relationships between work values and job burnout and work engagement, in a group of experienced police officers. We investigated: (a) the hierarchy of work values based on Super’s theory of career development, (b) relationships between work values and burnout and work engagement, and (c) differences between the work values in four groups (burned-out, strained, engaged, and relaxed). A group of 234 Polish police officers completed the Work Values Inventory (WVI) modeled upon Super’s theory, the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory and the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. The results show that police officers gave the highest priority to extrinsic work values. Job burnout was negatively correlated with the cognitive intrinsic work values (Creativity, Challenge, and Variety), while work engagement was positively correlated with the largest group of intrinsic work values (Creativity, Challenge, Variety, Altruism, and Achievement), as well as with the extrinsic work values (Prestige and Co-workers). The police officers showed significant differences, between levels of job burnout and work engagement, for intrinsic work values such as Variety, Challenge, and Creativity (large effects), and for Altruism and Prestige (moderate effects). The findings are discussed within the context of the Conservation of Resources theory, which explains how people invest and protect their personal resources, and how this is connected with preferred work values. We conclude that intrinsic work values are sensitive to different levels of burnout and engagement.

Values are viewed as deeply rooted motivations that guide and explain attitudes, standards, and behaviors (Schwartz, 1999). Values can influence how individuals evaluate various events and their importance, and also how they are motivated to undertake activities in different circumstances. Work is an important domain in a human being’s activities and its main function is to provide economic security. However, work also fulfills other psychological functions which lead to growth and learning, and it is also a manifestation of social activity. Work values determine what is important for employees and what they want to achieve in their work (Warr, 2008). So far, research has placed more emphasis on general values, not those of a specific work context. Additionally, more attention was paid to coherence between the general values of the employees and the values preferred by the organization. Thus, in this study we focused on the work value theory of career development by Super (1957, 1980) because the work context is more significant for the proper psychological functioning of employees, and for clarifying their goals and determining their matching for a given type of further education and career development. This life-span theory of career development emphasizes the concept of “role” (e.g., child, student, worker, or being a police officer), and that work values are important in the development of people’s individual role concepts. Super (1975) believed that “educators and personnel workers must look if they want to attend to motivation in ways relevant to the choices and performances of their students and employees” (p. 190). Work values modeled upon Super’s theory reflect different goals that motivate people to work, and are reflected in both extrinsic values to work (outcomes of work), and intrinsic values in work (those which people seek in their work activity). The context of work and its conditions are generally important for most people in any culture, and it is worthwhile to investigate which work values are given highest priority in order to understand what drives people in their work. For this reason, knowledge about which work values are given priority is invaluable for organizations.

Values represent our highest priorities (“I know what is important and valuable”), and define what is important and valuable for a person within a specific culture and context. Maslow (1987) exemplified “the basic values of our culture” (p. 183) by honesty, humanitarianism, and respect for the individual. Work is for some people, especially for those engaged in higher level occupations (such as in the policing profession), a means of self-actualization, that is, “valued for its own sake” (Super, 1975, p. 191) through finding a life-role. In Super’s life-span theory of career development (Super, 1962, 1970) more than a dozen specific work values are identified. Super (1980) defined these work values as “an objective, either a psychological state, a relationship, or material condition, that one seeks to attain” (p. 130).

Work values are related to work performance and job satisfaction (Chen and Kao, 2012; Tomaževič et al., 2018). However, in some professions organizational effectiveness depends on the respect of these values. This is mainly related to the ethics of these professions (Wang et al., 2018). For example, in the policing profession, responsibility for the security and effective protection of citizens coexists with a variety of interpersonal relations with citizens, as victims or persons violating the law, and is associated with occupational stress. Consequently, the work values preferred by police officers can be important for organizational success.

Work values can evolve during career development and they are related to vocational maturity. Moreover, they may depend on job-related well-being. In line with the Job Demands – Resources theory (Bakker and Demerouti, 2014, 2017), two aspects of well-being are distinguished, job burnout and work engagement. These are rather independent from each other, but correlated. In the work of police officers, there is a high risk of job burnout, whilst high engagement is expected. Past research shows that levels of both aspects of job-related well-being, job burnout and work engagement, are related to work values (Sortheix et al., 2013; Schreurs et al., 2014; Tartakovsky, 2016; Saito et al., 2018). Values are relatively stable over time (Konrad et al., 2000; Jin and Rounds, 2012), but the policing profession is associated with high engagement and a risk of burnout (Talavera-Velasco et al., 2018; Violanti et al., 2018), and the question is whether work values are sensitive to different levels of burnout and engagement.

There is a gap in the literature regarding the hierarchy of work values in police officers, how work values are associated with job burnout and work engagement in this group, and whether work values in police officers are sensitive to different levels of job burnout and work engagement. Applying the Conservation of Resources theory (COR, Hobfoll, 1989, 2011; Hobfoll et al., 2018) may help understand how people with different levels of job burnout and work engagement are motivated to invest and protect their personal resources at work, and how this is connected with preferred work values. Thus, the aim of the study was twofold. First, we aimed to examine the hierarchy of work values in police officers. Second, we aimed to investigate the relationships between work values and both aspects of job-related well-being, job burnout and work engagement, and whether work values in police officers are sensitive to different levels of job burnout and work engagement in a group of experienced police officers.

From the perspective of human resources management, an important distinction in work is made between extrinsic and intrinsic values (Ryan and Deci, 2000). Extrinsic work values focus on work outcomes for which people are given tangible rewards that are associated with the economic function of work, such as salary, prestige or job security. In contrast, intrinsic values focus on work outcomes that are related to psychological rewards such as recognition, opportunity for growth, and thriving (Bakker and Oerlemans, 2012; Spreitzer and Porath, 2014). Thus, extrinsic or intrinsic work values may lead to a variety of motivations and they require different managerial instruments and practices.

Extrinsic values are related to instrumental aspects of work and provide external rewards or satisfaction. They include such values as striving for financial success and high income, job security, opportunities for advancement, status, and power. Based on Super’s life-span theory of career development, Hartung et al. (2010) suggested that some work values such as Management, Workplace, Security, Prestige, and Income are extrinsic values. Further, Leuty and Hansen (2011) have revealed that these work values, and also Achievement, are moderately positively correlated with extrinsic rewards. Lifestyle was also identified as an extrinsic value (Super, 1962). It is possible that this value is sometimes assessed as “style in private life” (and thus as an intrinsic value), and sometimes as appreciation of the people around us, attitude to free time, and the balance between work and home.

Intrinsic values are reflected in an inherent psychological satisfaction with work. They include such general values as autonomy, interesting and meaningful work tasks, challenge, variety, emotional intimacy, community contribution, altruism, and personal growth. Hartung et al. (2010) classified Creativity, Challenge, Variety, Achievement, Lifestyle, Esthetics, Autonomy (or Independence), and Altruism as intrinsic values. Work values such as Creativity, Challenge, Variety, and Achievement are moderately positively correlated with intrinsic rewards (Lyons et al., 2006).

Some work values are ambiguous and may be classified as extrinsic and intrinsic simultaneously. It should be noted that Autonomy is related to both intrinsic and extrinsic rewards with similar magnitudes. In addition, Achievement is somewhat ambiguous, but is related more strongly to intrinsic rewards than to extrinsic rewards (Lyons et al., 2006). Hartung et al. (2010) pointed out that Co-workers and Supervision overlap both intrinsic and extrinsic values.

To better understand the role of work values as intrinsic or extrinsic, the terms of the five levels of Maslow’s (1987) hierarchy of needs can be used. Extrinsic values, due to their instrumental nature, are closely related to the basic levels of needs such as physiological, safety and security, and belongingness. Thus, Autonomy, Co-workers, and Supervision are viewed as more instrumental in the work context. In contrast, intrinsic values are more associated with higher levels of needs such as esteem and self-actualization. Hence, the work value Achievement is more reflected in growth and development and, in this way, can be classified as an intrinsic value. Hartung et al. (2010) argued that “in theory, intrinsic values reflect outcomes people seek in work because they are satisfying in and themselves, whereas extrinsic values reflect those outcomes desired because they provide some external reward or satisfaction” (p. 38).

Work values are positively associated with job satisfaction (Dawis and Lofquist, 1984; Rounds, 1990; Judge and Bretz, 1992; Zalewska, 1999; Dawis, 2002; Chen and Kao, 2012; Tomaževič et al., 2018) and with work performance (Swenson and Herche, 1994). Brown and Crace (1996) proposed that work values that are given a high priority are more critical for decision-making than work values given a low priority. This fact may have practical consequences in professions that frequently require appropriate decisions to be made quickly. Some situations in the work of police officers may be very stressful and require critical decision-making, and it is thus desirable to know which high-priority work values are shared by other police officers, at least in a specific culture or district. Furthermore, Ruibyte and Adamoniene (2013) showed that police officers valued work values other than effectiveness and productivity. In this profession the correct balance between extrinsic and intrinsic work values is particularly desirable because they are deeply held driving forces and they form the culture of the organization (Wasserman and Moore, 1988). The work value theory of career development by Super strongly emphasizes the work context, and its application facilitates connecting these values with occupational rewards and other instruments for personnel management.

According to the Job Demands – Resources theory, two facets of well-being, reflecting negative and positive indicators, are job burnout and work engagement (Bakker and Demerouti, 2014, 2017). Job burnout is a serious adverse consequence of work in a chronically demanding and threatening work environment. Job burnout has been described as a specific, prolonged reaction of employees to occupational stress (Schaufeli et al., 2009). It is increasingly emphasized that burnout syndrome comprises two main factors: exhaustion and disengagement from work (Demerouti et al., 2003, 2010). Exhaustion is described as a sense of loss of the physical, cognitive and emotional energy required to perform, as a long-term consequence of prolonged exposure to specific working conditions. Disengagement is a state in which a person distances himself or herself from the work, and holds negative attitudes toward the work object, work content and the work in general. Job burnout is correlated with low arousal emotions and with depression (Shirom and Ezrachi, 2003; Bakker and Oerlemans, 2012). Some studies indicate that job burnout is negatively related to intrinsic work values (van den Broeck et al., 2011; Saito et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the orientation toward extrinsic work values was observed in exhausted and disengaged employees (Tartakovsky, 2016; Saito et al., 2018).

Work engagement is one of the most important constructs of positive well-being at work, and of the adult’s happiness (Bakker and Oerlemans, 2012). Work engagement is defined as “a positive, fulfilling work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (Schaufeli et al., 2002, p. 74). It is positively correlated with intrinsic motivation (Schaufeli and Salanova, 2007). Further, an engaged employee differs from an unengaged one in personal resources such as autonomy, optimism, self-esteem, and self-efficacy (Bakker et al., 2008). An engaged employee is also willing to carry out both in-role behavior and extra-role behavior at work (Bakker and Schaufeli, 2008; Zhu, 2013). Moreover, engaged employees are more oriented to intrinsic work values and rewards (Sortheix et al., 2013; Schreurs et al., 2014; Saito et al., 2018).

Police officers are exposed to high work-related stress (Anshel, 2000; McCreary et al., 2017), and it is for this reason worthwhile to investigate the relationships between work values and job-related well-being. Two aspects of job-related well-being were included in the present study: job burnout (negative aspect), and work engagement (positive aspect). Only one study has investigated these relationships (Dyląg et al., 2013). That study, however, used another concept to assess work values, and aimed to investigate the discrepancy between individual and organizational values. It focused on validation of the instrument in a new population, while we have used a well-validated instrument. Dyląg et al. investigated work values, job burnout and work engagement in white-collar workers, while we have investigated these variables in police officers.

In previous studies, attention was paid to the association between job burnout and work engagement as the two facets of job-related well-being (Timms et al., 2012; Moeller et al., 2018). Some researchers focus on activation and pleasure (Russell, 2003; Bakker et al., 2012), while others take a broader approach and focus on energy, pleasure, challenges, and skills (Salanova et al., 2014).

We suggest that different levels of job burnout and work engagement indicate different degrees of the investment (maintaining and collecting), protect and withdrawal of personal resources in the work process. The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2011; Hobfoll et al., 2018) provides a useful framework for the conceptualization of these relationships. According to the COR theory, people strive to obtain, maintain, protect and promote resources that are valuable to them. The first principle of the COR theory postulates that the loss of resources is felt disproportionately more than the obtaining of resources. People who are threatened by a potential or actual loss of resources are more motivated to obtain, retain, foster and protect valued resources for future needs. The second principle of the COR theory postulates that people invest resources to conserve possessed resources, gain additional resources and offset the potential loss of resources. Those with greater resources are less vulnerable to resource loss, and they are more capable of organizing resource gain. This theory suggests that resource loss and resource gain occur in a process of “cycles” or “spirals.” A person who lacks access to large stores of resources is more likely to experience further resource loss when demands accumulate, and in this way goes through a downward spiral. In this way, people strive to accumulate resources, and cycles of resource loss tend to have a higher speed than cycles of resource gain. When moderate or massive losses are experienced, a defensive attitude is adopted.

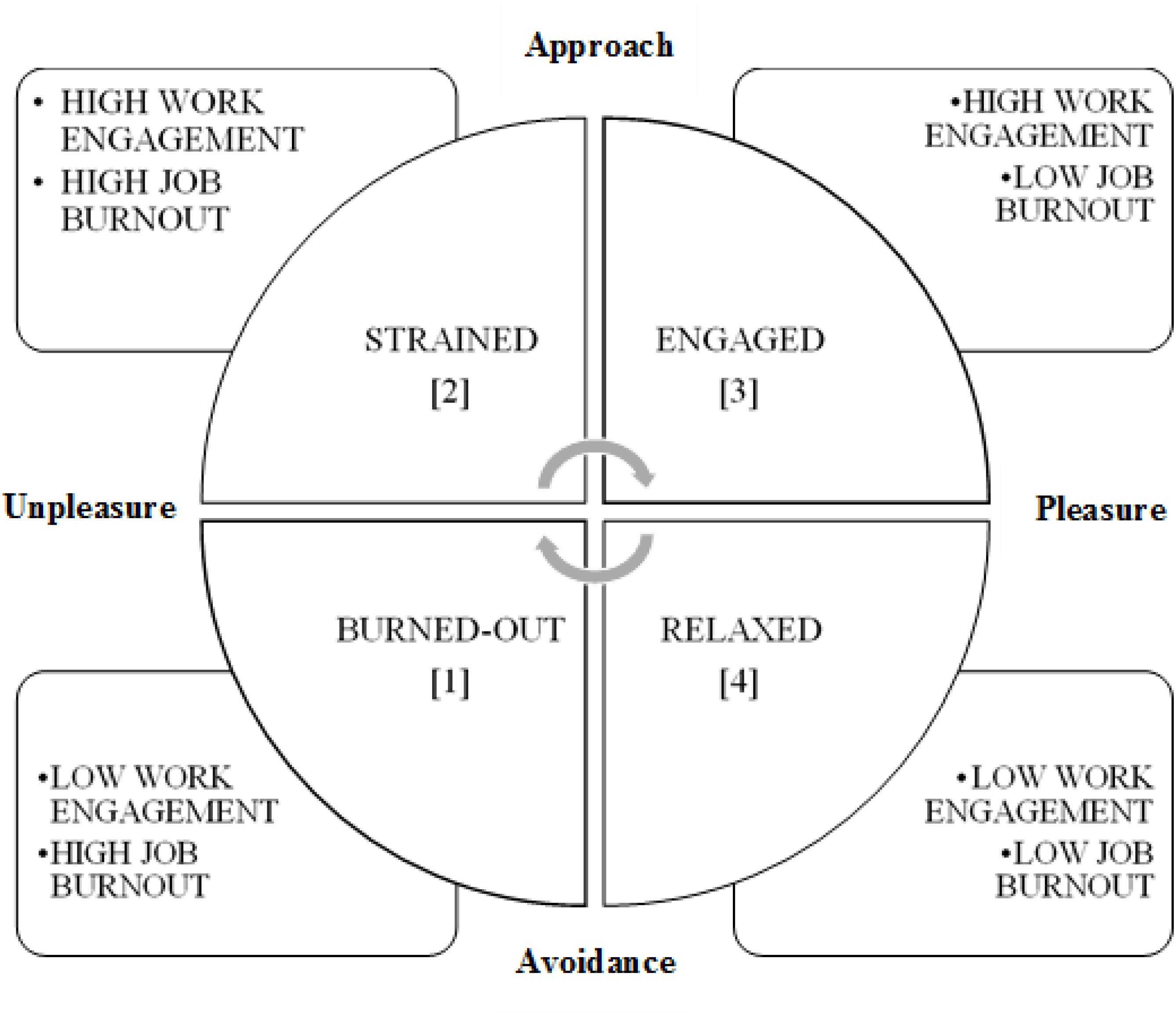

To facilitate understanding of the results from the current study, we used COR theory to create a conceptual model by introducing labels for four groups at different levels of job burnout and work engagement, compatible with the COR theory: burned-out, strained, engaged, and relaxed. Figure 1 presents a theoretical framework of the relationships between different levels of job burnout and work engagement. Two dimensions are defined. The first dimension includes pleasure-unpleasure states, while the second focuses on approach-avoidance with respect to work. These dimensions are related to a person’s affective state and the distribution of his or her personal resources. How can we apply this model on the investigated group? The first group comprises burned-out police officers, with a high level of job burnout and a low level of work engagement. This group has depleted personal resources, both energetic and motivational, and can be exhausted and fatigued because the access to resources is limited. The second group comprises strained police officers, with a high level of job burnout and a high level of work engagement. These police officers take risks in investing their personal resources because their resources are seriously depleted. In fact, they should protect their resources instead of involving them in the work. This may be a source of tension. The third group comprises engaged police officers. These are enthusiastic and characterized by a high level of work engagement and a low level of job burnout. They have strong personal resources and can invest in new ones. The fourth group comprises relaxed police officers, with a low level of job burnout and a low level of work engagement. These police officers do not invest their personal resources in work and are satisfied by the current status of their work.

Figure 1. A study model that distinguishes between various combinations of job burnout and work engagement compatible with the Conservation of Resources theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2011; Hobfoll et al., 2018).

Work values are relatively stable for most adult people, when measured by self-reported inventories (Dawis, 1991; Jin and Rounds, 2012). Work values are deep-rooted and quite stable also in police officers (Hazer and Alvares, 1981), but they may change with time, due to professional experiences, vocational maturity and the consequences of work. Positive experiences and positive consequences of work may result in work engagement, while negative ones may result in job burnout. It is possible that police officers adopt different coping strategies in stressful situations, which may result in their work values changing. The distinctions between the level of job burnout and work engagement interpreted in the COR theory (Figure 1) may shed new light on the priority of work values which are related to the way police officers invest personal resources (dimension of approach versus avoidance) to maintain their affective states (dimension of pleasure versus unpleasure).

It is necessary to know about the hierarchy of work values held by police officers in order to work actively for their well-being, job satisfaction, career development, intentions to stay in the job, and job tenure. We have pointed out that knowledge about individual work values in police officers is insufficient. Past studies mainly focus on work values among early stage career officers (students and cadets) (Hazer and Alvares, 1981; Zedeck et al., 1981; Sundström and Wolming, 2014; Cuvelier et al., 2015; Kohlström et al., 2017). The associations between work values and other work-related aspects have been relatively well-investigated, but little is known about the relationships between work values and job burnout and work engagement in police officers. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to investigate relationships between work values and job burnout and work engagement in police officers. The following research questions were formulated:

• Which work values are given highest priority by police officers?

• What is the relationship between work values and job burnout and work engagement?

• Are there any differences in work values between police officers with different degrees of job burnout and work engagement?

Participants consisted of 234 sworn police officers aged between 26 and 58 years (M = 35.6 standard deviation [SD] = 4.3), and with work tenure between 4 and 30 years (M = 12.3 SD = 4.5). In this group, 48 were women (21%). The police officers worked as investigators (60%), in the uniformed division (preventive police – 21%), in the logistic division (9%), or with other duties (9%). Most of them were in close relationships (marriage or cohabitation) (89%). They came from a group of police officers undergoing further education for future commissioned police officers at the Police Academy in Szczytno, Poland. Due to this fact, all of them had higher education degrees (93% at Master’s level and 7% at Bachelor’s level). Missing data did not exceed 2%, except for data regarding marital status (2.5%).

According to Polish institutions’ guidelines and national regulations regarding healthy and adult participants, a full ethical review and approval was not required. The study was approved by the Rector of the Police Academy. Before data sampling, the subjects were informed about the aims of the study and the rules for participation (informed consent and the right to information, protection of personal data and confidentiality guarantees, non-discrimination, without remuneration, and the right to withdraw from the study). Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. All the participants gave their written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Work values were assessed by the Polish version (Zalewska, 2000) of the German version (Seifert and Bergmann, 1983) of the Work Values Inventory (WVI), modeled upon Super’s Work Values Inventory (1970). Fourteen of these scales correspond closely to the original English version (Super, 1970). Siefert and Bergman added one value (Promotion) to the original version, and this value was also investigated in the current study. In addition, the work value Leisure was redefined as Lifestyle. The English labels of the work values used here were taken from the recent literature. Using a five-point Likert-type scale from 1 (Not important) to 5 (Very important), respondents rate the importance of 48 work-related phenomena that constitute 16 scales with three items each. For example, one of the three statements for the Achievement value is: “For me in my professional job, the realization that I have done something very well is…”. Scores range from 3 to 15 for each value, and higher scale scores show that the respondent places greater significance on the corresponding work value.

The User Manual for the WVI (Super, 1970) reports test-retest reliabilities ranging from 0.74 to 0.82 for 2 weeks, and provides sufficient evidence for content, construct, and concurrent validity of the instrument. Seifert and Bergmann (1983), and Zalewska (2000), have shown that both the German version and the Polish version of the WVI have sufficient stability and reliability scores. The internal consistency, measured by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, was above the lower limit of acceptability (values of 0.60 to 0.70), according to Nunnally (1978), for all work values. Two scales (Autonomy and Lifestyle) had values of Cronbach’s alpha at the lower limit of acceptability, while Management had the largest value (0.86). The WVI scales comprise only three items each, and therefore, Cronbach’s alpha may not be a suitable measure of reliability. Instead, a measure of mean interitem correlation is more appropriate to assess the homogeneity of the scales. A value of mean interitem correlation should exceed 0.30 (Robinson et al., 1991). Values of mean interitem correlations for all work values were satisfactory, with mean interitem correlations between 0.34 and 0.67.

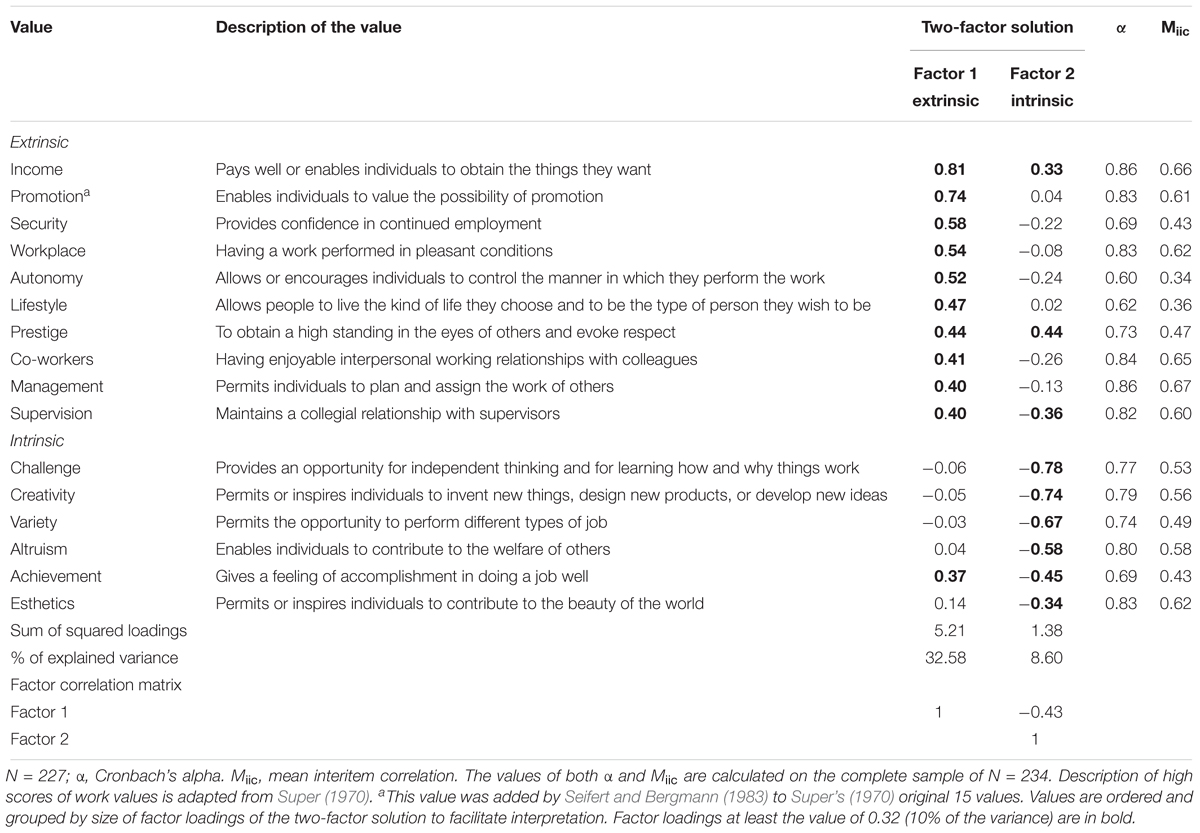

To determine the number of factors to extract from the WVI, we conducted exploratory factor analysis on the single scales, representing a total of 16 variables. In deciding how many factors to retain, we employed parallel analysis (PA) (Horn, 1965; Reise et al., 2000), using SPSS syntax by Hayton et al. (2004). In Table 1 we present the 16 actual eigenvalues from our sample of the 16 scales from the WVI, as well as the average and 95th percentile.

Table 1 shows two different suggestions for retaining the number of factors. In our PA results, both the first two and three actual eigenvalues are greater than those generated by PA (one for the average, and another one, for the 95th percentile criteria). It is therefore difficult to say what is the “correct” number of factors we could choose for the interpretation. However, Harshman and Reddon (1983) and Glorfeld (1995) suggested that PA has a tendency to “overfactor,” and according to Hayton et al. the 95th percentile of each eigenvalue is more conservative than the mean. In addition, the two factor-solution, with one factor comprising externalizing and another one comprising internalizing values is more consistent with Super’s theory and previous research. We therefore decided to retain two factors and interpret them as externalizing and internalizing.

In the next step, we performed our factor analysis (by principal axis factoring). We applied the practical recommendations of Tabachnick and Fidell (2018). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of adequacy (KMO) (Kaiser, 1974) was 0.87 (“meritorious”). Two factors accounted for 41.18% of the total variance (Table 2). An oblique rotation was chosen, because the correlation between the factors was strong (-0.43). After inspection, we labeled Factor 1 as “Extrinsic,” and Factor 2 as “Intrinsic.” Prestige cross-loaded on two factors. Previous findings indicated that Prestige is more correlated with extrinsic than intrinsic reward (Hartung et al., 2010; Leuty and Hansen, 2011). Thus, Prestige was included in the group of extrinsic values. In addition, Achievement cross-loaded on two factors with a somewhat higher loading on Factor 2. In line with Maslow (1987) and Hartung et al. (2010) we included Achievement in the group of intrinsic values (Factor 2).

Table 2. Factor loadings, percentage of extracted variance accounted by for each factor, based on principal axis factoring and oblimin rotation with Kaiser normalization of work values in police officers.

Job burnout was evaluated by means of the Polish version (Baka and Basińska, 2016) of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI; Demerouti et al., 2003, 2010). This scale consists of 16 items and measures two aspects of burnout: exhaustion (for example: “After my work, I usually feel worn out and weary”) and disengagement (for example: “Lately, I tend to think less at work and do my job almost mechanically”). Job burnout is the sum of the values for exhaustion and disengagement. The answering format is a four-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly agree) to 4 (Strongly disagree). The level of burnout is calculated as the average from the sum of scores divided by the number of items. Higher scores indicate a higher level of burnout. We have used the total OLBI scale score in the work reported here. We chose to do so because we aimed to evaluate the model presented in Figure 1. The descriptive statistics of OLBI in the group examined were M = 36.13, SD = 6.70, and median [Me] = 36, with an internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.79. We did not observe any significant difference in the level of job burnout depending on gender (t = 1.20, df = 228, p = 0.230).

Work engagement was evaluated by means of the Polish version (Szabowska-Walaszczyk et al., 2011) of the short version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9; Schaufeli and Bakker, 2003; Schaufeli et al., 2006). This scale measures the overall work engagement in terms of vigor (by the statement, for example: “At my work, I feel that I am bursting with energy”), dedication (“I am enthusiastic about my job”), and absorption (“I feel happy when I am working intensely”). Each item is rated on a seven-point scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 6 (Always/every day). The average of the sum of scores divided by the number of items gives the level of engagement. Higher scores indicate a higher work engagement. We used the total scale score in the present study, because we aimed to evaluate the model presented in Figure 1. Schaufeli et al. showed that the one-factor model of UWES-9 fits quite well to the data from ten national samples. The descriptive statistics of UWES-9 in the group examined were M = 34.42, SD = 8.74, Me = 35, with an internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.91. We did not find any significant difference between females and males in the level of work engagement (t = 0.82, df = 228, p = 0.412). In this study, job burnout and work engagement were moderately negatively correlated (r = -0.58, p < 0.001).

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients between variables were calculated, and the Bonferroni correction was applied (Howell, 1997). Student’s t-test for paired samples was applied to calculate the differences between the preferred work values. One-way ANOVA was used to compare differences in the preferred work values between groups. The four groups with different levels of job burnout and work engagement were created (see Figure 1), using the group mean values. The effect sizes were calculated using η2. A value of 0.02 for this coefficient indicates a small effect size, 0.06 a moderate effect size, and 0.14 a large effect size (Ferguson and Takane, 1989). The Honest Significant Difference (HSD) Tukey post hoc tests for unequal frequencies in the groups were carried out using the STATISTICA 13.1 program. Other statistical analyses were performed in SPSS 25.

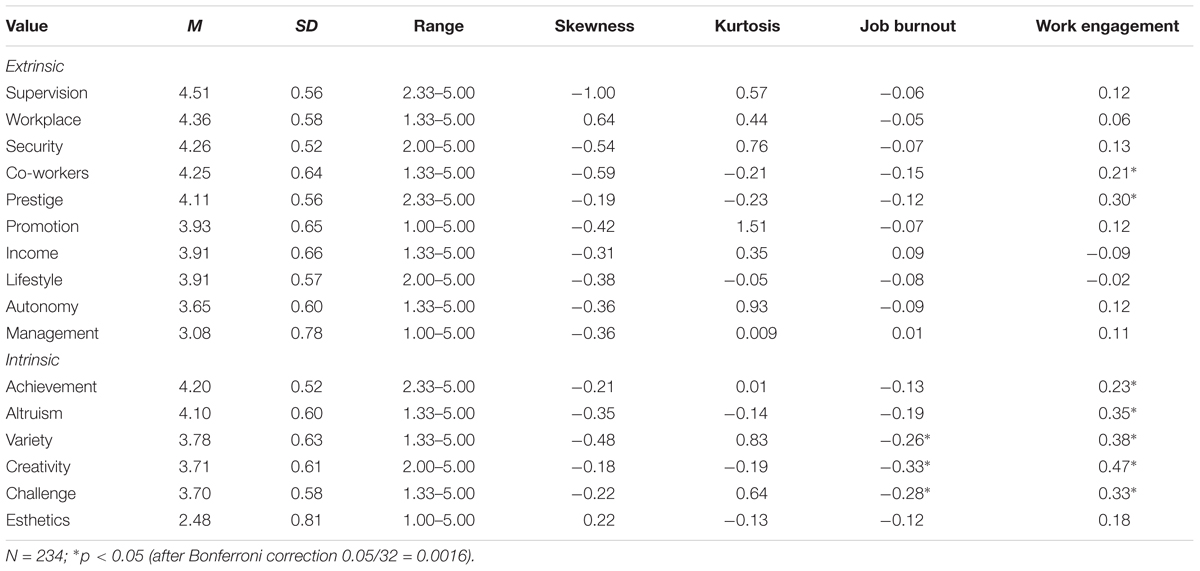

Table 3 presents details of the hierarchical structure of the work values, grouped into intrinsic and extrinsic work values. The work values measured in the current study fulfilled the criteria for normal distribution.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of work values and their correlations with job burnout and work engagement.

The work values given highest priority by police officers were: Supervision, Workplace, Security, Co-workers, and Achievement. Among the most appreciated work values, only one – Achievement – derived from the group of intrinsic values. The differences between work values in rank 1 Supervision (t = 3.79, df = 233 p < 0.001) and in rank 2 Workplace (t = 2.76, df = 233 p < 0.01) were significantly higher than the next group of work values (Security, Co-workers, and Achievement). Esthetics was not highly valued.

In addition, Table 3 shows correlations between work values and job burnout and work engagement. Table 3 shows that work engagement was more highly correlated with work values than job burnout was. Work engagement was moderately positively correlated with Creativity, Variety, Challenge, Altruism and Prestige.

We noted some difference in evaluation of work values depending on gender. Females valued Achievement (t = 3.60, df = 228, p < 0.001), Supervision (t = 3.91, df = 228, p < 0.001) and Security (t = 3.69, df = 228, p < 0.001) as more important than males did. These effect sizes, measuring by Cohen’s d coefficient, were medium (ranged between 0.62 and 0.70). Females also more appreciated than males Altruism (t = 2.10, df = 228, p < 0.05), Prestige (t = 2.38, df = 228, p < 0.05) and Co-workers (t = 1.98, df = 228, p < 0.05). However, these effect sizes were small (ranged between 0.36 and 0.39).

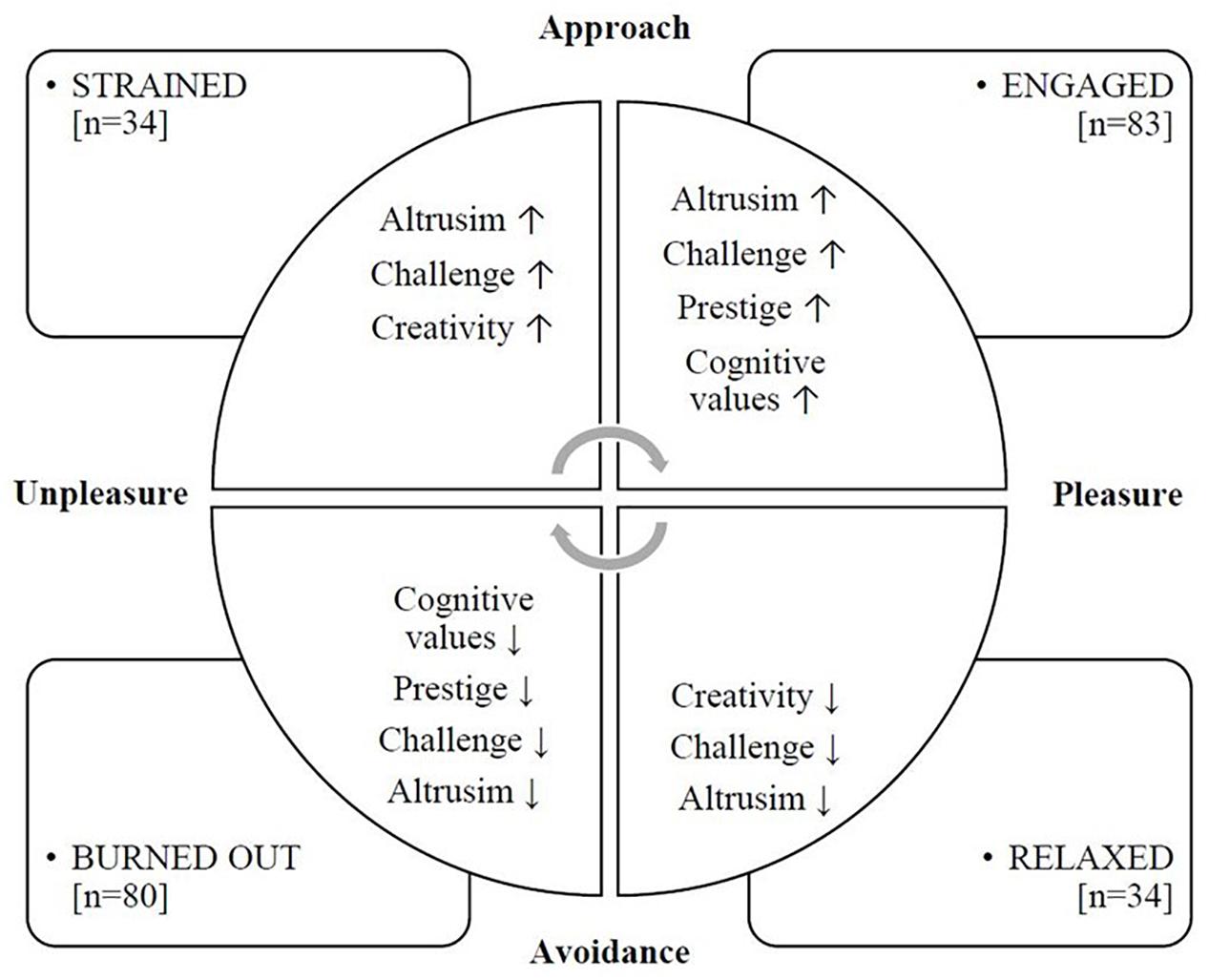

Four groups with different levels of job burnout and work engagement were formed by grouping the police officers according to their mean score on OLBI and UWES-9 (Figure 2). Two groups were relatively large: 36% of police officers were placed into the engaged group and 34% into the burned-out group. The strained group and the relaxed group each consisted of 15% of the police officers.

Figure 2. Work values among four groups of Polish police officers (N = 231): An application of a model, presented in Figure 1. It distinguished between various combinations of job burnout and work engagement.

Before applying post hoc tests, 6 of the 16 work values differentiated significantly the police officers with respect to job burnout and work engagement. The effect sizes measured by η2 coefficients were small for Achievement, moderate for Prestige and Altruism, and large for Variety, Challenge and Creativity. Table 4 presents the statistics relating to group differences.

Table 4 shows that burned-out police officers were systematically lower on the presented work values than those who were relaxed. Strained police officers were higher than relaxed police officers on Altruism and Creativity, while the relaxed police officers were lower on these values than those who were engaged. The effects of group differences in Variety and Creativity were large, while the effects on Altruism and Prestige were moderate. After applying the HSD Tukey test, the mean difference between the groups on Achievement was no longer significant and the effect was small.

The results presented here show that: (a) police officers gave the highest priority to the following work values: Supervision, Workplace, Security, Co-workers, Achievement; (b) job burnout was significantly negatively correlated with the intrinsic work values Creativity, Challenge, and Variety, while the magnitude of the correlation was moderate; (c) work engagement was significantly positively correlated with the intrinsic work values Creativity, Variety, Altruism, Challenge, and Achievement, as well as with the extrinsic work values Prestige and Co-workers; and (d) there were significant differences between police officers with different levels of job burnout and work engagement for intrinsic work values such as Variety, Challenge, and Creativity (large effects), and for Altruism and Prestige (moderate effects).

The values given highest priority by police officers in this study were Supervision, Workplace, Co-workers, Security, and Achievement. All, with the exception of Achievement, derived from the group of extrinsic values. These values may be regarded as an important key for many successful organizations, and they are related to the five most basic resources in an organization (such as a place to work, the right equipment, money to pay the bills, and the right people working there). Previous studies in healthy and well-educated groups showed that men prefer extrinsic values and that they are more monetary and prospect oriented (Furnham and MacRae, 2018; Guo et al., 2018). Our sample comprised of 80% males, and this may partly explain their preference of extrinsic values, regardless the policing profession. These extrinsic values may also be regarded as lower-order needs, the need of security and the need to belong, as identified in Maslow’s (1987) hierarchy of needs. Previous research has shown that such work values raise intrinsic motivation significantly and lead to people persisting longer with a challenging task willingly, reporting greater interest in the task, becoming more engrossed in it, performing better on it, and spontaneously expressing greater enjoyment of and interest in it (Carr and Walton, 2014). To summarize, the police officers gave a high priority to having an understanding and respectful manager, the possession of good coworkers, friction-free collaboration with others, the certainty of their job, and the security of their current position. Police officers almost always work together, and it was not unexpected that they gave a highest priority to a fundamental basic value – the need to belong.

The priorities given to various work values may differ between different cultures, due to individual differences or the availability of resources in a particular police district or country (this is the case also for Maslow’s hierarchy of needs). Ruibyte and Adamoniene (2013) pointed out that a change in values may occur over time in post-transformation (that is after the fall of the iron curtain and the transformation to market-based capitalism) countries such as Lithuania, because of rapid changes in society, increased competition, and thus, more demanding work conditions. The current study was performed in Poland, which is a post-transformation country. These studies differ in the methods used and this means that it is not easy to compare the results. The police officers studied by Ruibyte and Adamoniene were asked to describe their beliefs about organizational values. They replied that clear time limits, the achievement of good performance, professional development, security, integrity and formality were the beliefs that were most highly valued in the police organization. A study of first-year student police officers in Sweden (Sundström and Wolming, 2014) showed that altruistic values were most important, which contrasts with the results presented here: altruistic values were among the work values given medium levels of priority (Table 3). It is possible that the differences are related to the duration of work tenure. Sundström and Wolming studied student police officers, whereas we have studied experienced police officers. More research on the work values of police officers in different countries is needed.

A higher level of job burnout and a lower level of work engagement were significantly related to some of the intrinsic work values. This was expected because these two aspects of job-related well-being are correlated with each other and also with an intrinsic motivation (Schaufeli and Salanova, 2007; Maslach and Leiter, 2008; Sortheix et al., 2013; Schreurs et al., 2014; Saito et al., 2018). Furthermore, a higher level of work engagement was correlated with two extrinsic values, Co-workers and Prestige. Employees that are more engaged are more willing to perform an occupational role in a social environment (Bakker and Schaufeli, 2008; van den Broeck et al., 2011).

Three intrinsic work values (Creativity, Challenge, and Variety), closely related to intrinsic rewards, were positively correlated to the level of work engagement, and negatively correlated to the level of job burnout (Table 3). These values are theoretically related to the impairment of cognitive functions (such as frequent switching between tasks, an inability to update activity, inhibition of certain cognitive functions, impairments in sustained and controlled attention, poor long-term and short-term memory, and poor working memory) (Deligkaris et al., 2014; Golonka et al., 2017; Sokka et al., 2017). These relationships suggest that job burnout can be associated with cognitive impairment, which is compatible with findings presented by Deligkaris et al. (2014). Deligkaris et al. showed that people who are burned out have impaired cognitive functions, such as executive functions, attention and memory.

First, we discuss the two largest groups, burned-out and engaged, according to our conceptual model. Our results (Table 4 and Figure 2) show that the burned-out police officers and engaged police officers had the largest difference in the mean values of intrinsic values. This is consistent with results of previous studies regarding other groups than police officers (Timms et al., 2012; Salmela-Aro and Read, 2017; Moeller et al., 2018; Schult et al., 2018). These studies suggest that job-related well-being decreases as less priority is given to intrinsic values (Tartakovsky, 2016; Saito et al., 2018). In particular, the group of three work values: Creativity, Challenge, and Variety, was less preferred. As mentioned above, people who are burned out can have cognitive deficits and they need to protect their depleted mental resources more. Further, the burned-out police officers gave lower priority to Altruism and Prestige than engaged police officers gave. It is not surprising that this group gave less priority to intrinsic work values, since job burnout is characterized by a lack of cognitive and mental energies (Demerouti et al., 2010; van den Broeck et al., 2011). Police officers in this group had neither the power nor the desire to get involved in work-related social relationships or social comparisons. One aspect of job burnout is disengagement, which is expressed in psychological withdrawal from the task, clients and work in general. It is not known whether this withdrawal is an adaptive mechanism to cope with the excessive occupational stress that results in feelings of exhaustion (Hobfoll and Shirom, 2001; Arble et al., 2018). It may also indicate that the police officers limit their investment of resources and adopt a defensive attitude in order to protect themselves.

The Relaxed police officers, who were neither burned-out nor engaged, gave a lower priority to Altruism than the strained police officers, and they gave a lower priority to Challenge than engaged officers. They valued Creativity less than those who were engaged, and less than those who were strained. These findings are compatible with Hobfoll’s (1989) COR theory. Specifically, the level of engagement determines how much of own resources are invested in the process of work. Relaxed employees invest fewer of their own resources because work in general can be less valuable to them. Thus, they are also called unengaged or unfulfilled in the work and even apathetic (Timms et al., 2012; Moeller et al., 2018; Schult et al., 2018). Our findings are compatible with results obtained by Salanova et al. (2014), and introduce a new aspect: we have included work values in our model (Figure 2). Salanova et al. validated a theory-based classification of employees’ well-being, using a classification of participants similar to that we have used, and identified a group who gave low priority to work. They denoted this group as “working from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.,” and it corresponds to our relaxed group.

The results of the study demonstrated that trained and engaged police officers showed no difference in their preferred work values. These groups were characterized by similar levels of work engagement (Figure 2). Past research shows that engaged employees are full of empowered (Timms et al., 2012; Moeller et al., 2018). In contrast, strained employees experience job burnout and engagement simultaneously and that they therefore can be considered as striving, frustrated or being under pressure (Timms et al., 2012; Salmela-Aro and Read, 2017; Schult et al., 2018). It can be assumed that a higher level of engagement is conducive to investing personal resources, irrespective of their wealth or poverty (Violanti et al., 2018). In addition, creativity was more important for the police officers who were strained than it was for burned-out. Results of previous studies have suggested that creative and challenging work is needed in order to satisfy people’s need for growth, learning and development (Ryan and Deci, 2000; Paterson et al., 2014). This result is also compatible with Hobfoll’s (1989) COR theory, which states that some burned-out employees want to invest and thrive, despite the burnout. The engagement of employees is a fundamental factor in building a competitive advantage of an organization on the labor market (Paterson et al., 2014).

This study has some limitations. First, it has a cross-sectional design, which does not allow causal directions of the relationships between work values and job burnout/work engagement to be formulated. However, it is theoretically well-proven that preferred work values are closer to personal dispositions (Jin and Rounds, 2012) and have a higher priority. In contrast, well-being is a consequence of work (Bakker and Oerlemans, 2012). Second, the way in which data were collected may have given an unrepresentative sample. The participants were, however, from several Polish districts, which increases the probability of obtaining a representative sample. Third, males outnumbered females, and this imbalance may have affected the results. The number of women in the study (about 20%) was, however, higher than the number of women among the Polish police officers (14%, data from the National Police Headquarters). Fourth, we have not investigated the stability of work values. Work values, however, are relatively stable (Dawis, 1991; Jin and Rounds, 2012; Leuty, 2013). It is easy to assume that work values are dynamic and flexible, as they are influenced by environmental factors (such as education, change of socioeconomic status, change in marital status), and as employees are exposed to work-related trials (such as experiences during working life, consequences of the work carried out, and change in occupation). Furthermore, employees experience rapidly changing societies, increased competition and individualism, and, again, it is easy to assume that work values change with time. However, only few studies have shown that work values are influenced by experiences and by environmental factors. Hazer and Alvares (1981), for example, showed that organizational entry and assimilation resulted in work value stability in police officers.

Police officers are extremely important for a properly functioning society and for citizen security. Taken together, the hierarchy of work values, relationships within the theoretical model, and the discovery of significant differences between the groups provide information that managers should consider when providing career assessment for police officers, and when support them. It is important for managers to identify police officers who show early signs of job burnout, in order to provide work resources and managerial support, which lead in turn to satisfied co-workers and role clarity. Future research should focus on similar variables in the populations of police officers in other countries, in order to determine how general our results are.

To conclude, we have examined work values of experienced police officers and identified those given a high priority. We have examined also the relationships between work values and two important aspects of job-related well-being, job burnout and work engagement. The results show that extrinsic work values were given high priority. In contrast, intrinsic work values are more sensitive to different levels of job burnout combined with different levels of work engagement. The burned-out group and the engaged group were the most different in terms of intrinsic work values. Three of these intrinsic work values (Creativity, Challenge, and Variety). that are theoretically related to cognitive processes, were positively correlated with work engagement, and negatively correlated with job burnout. Police organizations should be aware that work values are important aspects of working life and thus should be taken into consideration during the selection and assessment process throughout the vocational career.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the supplementary files.

BB designed the study, performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. AD designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

This work was financially supported by University West (Trollhättan, Sweden) to AD during the preparation of this article and the library of University West provided the publication costs.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Åke Hellström for conducting the parallel analysis, and for checking our description of the factor analysis.

Anshel, M. (2000). A conceptual model and implications for coping with stressful events in police work. Crim. Justice Behav. 27, 375–400. doi: 10.1177/0093854800027003006

Arble, E., Daugherty, A. M., and Arnetz, B. B. (2018). Models of first responder coping: police officers as a unique population. Stress Health 34, 612–621. doi: 10.1002/smi.2821

Baka,Ł., and Basińska, B. A. (2016). Psychometryczne właściwości polskiej wersji oldenburskiego kwestionariusza wypalenia zawodowego (OLBI) [Psychometric properties of the polish version of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI)]. Med. Pr. 67, 29–41. doi: 10.13075/mp.5893.00353

Bakker, A., Demerouti, E., and Xanthopoulou, D. (2012). How do engaged employees stay engaged. Cienc. Trab. 14, 15–21.

Bakker, A., and Oerlemans, W. (2012). “Subjective well-being in organizations,” in The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship, eds K. S. Cameron and G. M. Spreitzer (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 178–189.

Bakker, A., and Schaufeli, W. (2008). Positive organizational behavior: engaged employees in flourishing organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 29, 147–154. doi: 10.1002/job.515

Bakker, A., Schaufeli, W., Leiter, M., and Taris, T. (2008). Work engagement: an emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work Stress 22, 187–200. doi: 10.1080/02678370802393649

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2014). “Job demands-resources theory,” in Wellbeing: A Complete Reference Guide. Work and Wellbeing, eds P. Y. Chen and C. L. Cooper (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell), 37–64.

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22, 273–285. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000056

Brown, D., and Crace, R. (1996). Values in life role choices and outcomes: a conceptual model. Career Dev. Q. 44, 211–223. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.1996.tb00252.x

Carr, P., and Walton, G. (2014). Cues of working together fuel intrinsic motivation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 53, 169–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2014.03.015

Chen, C. V., and Kao, R. H. (2012). Work values and service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors: the mediation of psychological contract and professional commitment: a case of students in Taiwan police college. Soc. Indic. Res. 107, 149–169. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9832-7

Cuvelier, S. J., Jia, D., and Jin, C. (2015). Chinese police cadets’ attitudes toward police roles revisited. Policing 38, 250–264. doi: 10.1108/PIJPSM-09-2014-0101

Dawis, R. (1991). “Vocational interest, values, and preferences,” in Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, eds M. Dunette and L. Hough (Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press), 833–871.

Dawis, R. (2002). “Person-environment-correspondence theory,” in Career Choice and Development, ed. S. Brown (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 427–464.

Dawis, R., and Lofquist, L. (1984). A Psychological theory of Work Adjustment. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minneapolis Press.

Deligkaris, P., Panagopoulou, E., Montgomery, A., and Masoura, E. (2014). Job burnout and cognitive functioning: a systematic review. Work Stress 28, 107–123. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2014.909545

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A., Vardakou, I., and Kantas, A. (2003). The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: a multitrait-multimethod analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 19, 12–23. doi: 10.1027//1015-5759.19.1.12

Demerouti, E., Mostert, K., and Bakker, A. (2010). Burnout and work engagement: a thorough investigation of the independency of both constructs. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 15, 209–222. doi: 10.1037/a0019408

Dyląg, A., Jaworek, M., Karwowski, W., Kozusznik, M., and Marek, T. (2013). Discrepancy between individual and organizational values: occupational burnout and work engagement among white-collar workers. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 43, 225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2013.01.002

Ferguson, G., and Takane, Y. (1989). Statistical Analysis in Psychology and Education, 6th Edn. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Furnham, A., and MacRae, I. (2018). The dark side of work values. Curr. Psychol. 1–7. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9873-z

Glorfeld, L. W. (1995). An improvement on Horn’s parallel analysis methodology for selecting the correct number of factors to retain. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 55, 377–393. doi: 10.1177/0013164495055003002

Golonka, K., Mojsa-Kaja, J., Gawlowska, M., and Popiel, K. (2017). Cognitive impairments in occupational burnout–error processing and its indices of reactive and proactive control. Front. Psychol. 8:676. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00676

Guo, J., Eccles, J., Sortheix, F., and Salmela-Aro, K. (2018). Gendered pathways towards STEM careers: the incremental roles of work value profiles above academic task values. Front. Psychol. 9:1111. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01111

Harshman, R. A., and Reddon, J. R. (1983). “Determining the number of factors by comparing real with random data: a serious flaw and some possible corrections,” in Proceedings of the Classification Society of North America at Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, 14–15.

Hartung, P., Fouad, N., Leong, F., and Hardin, E. (2010). Individualism-collectivism links to occupational plans and work values. J. Career Assess. 18, 34–45. doi: 10.1177/1069072709340526

Hayton, J. C., Allen, D. G., and Scarpello, V. (2004). Factor retention decisions in exploratory factor analysis: a tutorial on parallel analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 7, 191–205. doi: 10.1177/1094428104263675

Hazer, J., and Alvares, K. (1981). Police work values during organizational entry and assimilation. J. Appl. Psychol. 66, 12–18. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.66.1.12

Hobfoll, S. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 84, 116–122. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016

Hobfoll, S., and Shirom, A. (2001). “Conservation of resources theory: applications to stress and management in the workplace,” in Handbook of Organizational Behavior, 2nd Edn, ed. R. Golembiewski (New York, NY: Marcel Dekker), 57–80.

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., and Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 5, 103–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika 30, 179–185. doi: 10.1007/BF02289447

Jin, J., and Rounds, J. (2012). Stability and change in work values: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 326–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.10.007

Judge, T., and Bretz, R. (1992). Effects of work values on job choice decisions. J. Appl. Psychol. 77, 261–271. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.77.3.261

Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrica 39, 31–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02291575

Kohlström, K., Rantatalo, O., Karp, S., and Padyab, M. (2017). Policy ideals for a reformed education: how police students value new and enduring content in a time of change. J. Workplace Learn. 29, 524–536. doi: 10.1108/JWL-09-2016-0082

Konrad, A. M., Ritchie, J. E. Jr., Lieb, P., and Corrigall, E. (2000). Sex differences and similarities in job attribute preferences: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 126, 593–641. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.4.593

Leuty, M. (2013). Stability of scores on super’s work values inventory–revised. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 46, 202–217. doi: 10.1177/0748175613484034

Leuty, M., and Hansen, J. (2011). Evidence of construct validity for work values. J. Vocat. Behav. 79, 379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.04.008

Lyons, S. T., Duxbury, L. E., and Higgins, C. A. (2006). A comparison of the values and commitment of private sector, public sector, and parapublic sector employees. Public Admin. Rev. 66, 605–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00620.x

Maslach, C., and Leiter, M. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 93, 498–512. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498

McCreary, D. R., Fong, I., and Groll, D. L. (2017). Measuring policing stress meaningfully: establishing norms and cut-off values for the operational and organizational police stress questionnaires. Police Pract. Res. 18, 612–623. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2017.1363965

Moeller, J., Ivcevic, Z., White, A. E., Menges, J. I., and Brackett, M. A. (2018). Highly engaged but burned out: intra-individual profiles in the US workforce. Career Dev. Int. 23, 86–105. doi: 10.1108/CDI-12-2016-0215

Paterson, T., Luthans, F., and Jeung, W. (2014). Thriving at work: impact of psychological capital and supervisor support. J. Organ. Behav. 35, 434–446. doi: 10.1002/job.1907/full

Reise, S. P., Waller, N. G., and Comrey, A. L. (2000). Factor analysis and scale revision. Psychol. Assess. 12, 287–297. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.12.3.287

Robinson, J. P., Shaver, P. R., and Wrightsman, L. S. (eds). (1991). Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes, Vol. 1. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Rounds, J. (1990). The comparative and combined utility of work value and interest data in career counseling with adults. J. Vocat. Behav. 37, 32–45. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(90)90005-M

Ruibyte, L., and Adamoniene, R. (2013). Occupational values in Lithuania police organization: managers’ and employees’ value congruence. Inz. Ekon. 24, 468–477. doi: 10.5755/j01.ee.24.5.3309

Russell, J. (2003). Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychol. Rev. 110, 145–172. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.110.1.145

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Saito, Y., Igarashi, A., Noguchi-Watanabe, M., Takai, Y., and Yamamoto-Mitani, N. (2018). Work values and their association with burnout/work engagement among nurses in long-term care hospitals. J. Nurs. Manag. 26, 393–402. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12550

Salanova, M., Del Libano, M., Llorens, S., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2014). Engaged, workaholic, burned out or just 9 to 5? Toward a typology of employee well-being. Stress Health 30, 71–81. doi: 10.1002/smi.2499

Salmela-Aro, K., and Read, S. (2017). Study engagement and burnout profiles among Finnish higher education students. Burn. Res. 7, 21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2017.11.001

Schaufeli, W., and Bakker, A. (2003). Utrecht Work Engagement Scale; Test forms (UWES). Utrecht: Utrecht University.

Schaufeli, W., Bakker, A., and Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire a cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 66, 701–716. doi: 10.1177/0013164405282471

Schaufeli, W., Leiter, M., and Maslach, C. (2009). Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev. Int. 14, 204–220. doi: 10.1108/13620430910966406

Schaufeli, W., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., and Bakker, A. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 3, 71–92. doi: 10.1023/A:1015630930326

Schaufeli, W. B., and Salanova, M. (2007). “Work engagement: an emerging psychological concept and its implications for organizations,” in Managing Social and Ethical Issues in Organizations. Research in Social Issues in Management, Vol. 5, eds S. W. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, and D. P. Skarlicki (Houston, TX: Rice University).

Schreurs, B., van Emmerik, H. I. J., van den Broeck, A., and Guenter, H. (2014). Work values and work engagement within teams: the mediating role of need satisfaction. Group Dyn. 18, 267–281. doi: 10.1037/gdn0000009

Schult, T. M., Mohr, D. C., and Osatuke, K. (2018). Examining burnout profiles in relation to health and well-being in the Veterans Health Administration employee population. Stress Health 34, 490–499. doi: 10.1002/smi.2809

Schwartz, S. H. (1999). A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 48, 23–47. doi: 10.1080/026999499377655

Seifert, K. H., and Bergmann, C. (1983). Deutschsprachige adaptation des work values inventory von super – Ergebnisse bei gymnasiasten und berufstätigen [German adaptation of super’s work values inventory – Results from high school students and occupational workers]. Psychol. Prax. Z. Arbeits Organisationspsychol. 27, 160–172.

Shirom, A., and Ezrachi, Y. (2003). On the discriminant validity of burnout, depression and anxiety: a re-examination of the burnout measure. Anxiety Stress Coping 16, 83–97. doi: 10.1080/1061580021000057059

Sokka, L., Leinikka, M., Korpela, J., Henelius, A., Lukander, J., Pakarinen, S., et al. (2017). Shifting of attentional set is inadequate in severe burnout: evidence from an event-related potential study. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 112, 70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.12.004

Sortheix, F. M., Dietrich, J., Chow, A., and Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). The role of career values for work engagement during the transition to working life. J. Vocat. Behav. 83, 466–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2013.07.003

Spreitzer, G., and Porath, C. (2014). “Self-Determination as a nutriment for thriving: building an integrative model of human growth at work,” in The Oxford Handbook of Work, ed. M. Gagne (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 245–254.

Sundström, A., and Wolming, S. (2014). Swedish student police officers’ job values and relationships with gender and educational background. Police Pract. Res. 15, 35–47. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2013.815385

Super, D. E. (1962). The structure of work values in relation to status, achievement, interests, and adjustment. J. Appl. Psychol. 46, 231–239. doi: 10.1037/h0040109

Super, D. E. (1975). “The work values inventory,” in Contemporary Approaches to Interest Measurement, ed. D. G. Zytowski (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press).

Super, D. E. (1980). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. J. Vocat. Behav. 52, 129–148. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(80)90056-1

Swenson, M., and Herche, J. (1994). Social values and salesperson performance: an empirical examination. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 22, 283–289. doi: 10.1177/0092070394223009

Szabowska-Walaszczyk, A., Zawadzka, A., and Wojtaś, M. (2011). Zaangażowanie w pracę i jego korelaty: adaptacja skali UWES autorstwa Schaufeliego i Bakkera [Work engagement and its correlates: adaptation of the UWES by Schaufeli and Bakker]. Psychol. Jakości Życia 10, 57–74.

Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, L. S. (2018). Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th Edn. New York, NY: Pearson Education.

Talavera-Velasco, B., Luceño-Moreno, L., Martín-García, J., and García-Albuerne, Y. (2018). Psychosocial risk factors, burnout and hardy personality as variables associated with mental health in police officers. Front. Psychol. 9:1478. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01478

Tartakovsky, E. (2016). Personal value preferences and burnout of social workers. J. Soc. Work 16, 657–673. doi: 10.1177/1468017315589872

Timms, C., Brough, P., and Graham, D. (2012). Burnt-out but engaged: the co-existence of psychological burnout and engagement. J. Educ. Adm. 50, 327–345. doi: 10.1108/09578231211223338

Tomaževič, N., Seljak, J., and Aristovnik, A. (2018). Occupational values, work climate and demographic characteristics as determinants of job satisfaction in policing. Police Pract. Res. 1–18. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2018.1500282

van den Broeck, A., van Ruysseveldt, J., Smulders, P., and de Witte, H. (2011). Does an intrinsic work value orientation strengthen the impact of job resources? A perspective from the Job Demands-Resources Model. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 20, 581–609. doi: 10.1080/13594321003669053

Violanti, J. M., Mnatsakanova, A., Andrew, M. E., Allison, P., Gu, J. K., and Fekedulegn, D. (2018). Effort–reward imbalance and overcommitment at work: associations with police burnout. Police Q. 21, 440–460. doi: 10.1177/1098611118774764

Wang, K. Y., Chou, C. C., and Lai, J. C. Y. (2018). A structural model of total quality management, work values, job satisfaction and patient-safety-culture attitude among nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12669 [Epub ahead of print].

Warr, P. (2008). Work values: some demographic and cultural correlates. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 81, 751–775. doi: 10.1348/096317907X263638

Wasserman, R., and Moore, M. (1988). Values in Policing. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

Zalewska, A. (1999). Achievement and social relations values as conditions of the importance of work aspects and job satisfaction. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 5, 395–416. doi: 10.1080/10803548.1999.11076428

Zalewska, A. (2000). Adaptacja kwestionariusza “Orientacja na wartości zawodowe” Seiferta i Bergmanna do warunków polskich [Polish adaptation of super’s work values inventory Seifert and Bergmann]. Stud. Psychol. 38, 57–77.

Zedeck, S., Middlestadt, S., and Hayes, E. (1981). Police work values: a comparison of police science students and current officers. J. Occup. Psychol. 54, 187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1981.tb00059.x

Keywords: work values, occupational well-being, job burnout, work engagement, Super’s Work Values Inventory, Conservation of Resources theory, police officers

Citation: Basinska BA and Dåderman AM (2019) Work Values of Police Officers and Their Relationship With Job Burnout and Work Engagement. Front. Psychol. 10:442. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00442

Received: 17 October 2018; Accepted: 13 February 2019;

Published: 14 March 2019.

Edited by:

Montgomery Anthony, University of Macedonia, GreeceReviewed by:

Krystyna Golonka, Jagiellonian University, PolandCopyright © 2019 Basinska and Dåderman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anna M. Dåderman, YW5uYS5kYWRlcm1hbkBodi5zZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.