- 1Department of Management and Organization, School of Business and Economics, VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 2Utrecht School of Economics, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

This paper examines how employees’ career aspirations benefit organizations, i.e., contribute to strengthening organizational capabilities and connections, by means of two aspects of contemporary work: proactive and relational. Data were collected from alumni of a public university in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, in two waves with a 1-year time lag. The results showed that employees with career aspirations strengthen: (a) organizational capabilities; and (b) organizational connections through their instrumental and psychosocial relationships. Interestingly, although employees’ career aspirations were positively associated with taking charge, we did not find that taking charge mediates the relationship between career aspirations and employees’ individual contributions to organizational capabilities. This study is the first to examine how individual career aspirations benefit organizations, and it discusses the results in light of their novel contributions to theory and practice.

Introduction

Over the past decade, scholars have highlighted the importance of employees’ contribution to organizational effectiveness (e.g., Griffin et al., 2007; Strauss et al., 2015). This is because, in today’s dynamic and accelerated business environment, organizations rely heavily on employees’ novel and creative input to outperform competitors, excite customers and offer better services (Yang et al., 2016). Parallel to this trend, many career theorists contend that individuals have become active and agentic in their career development, generating strategies to fulfill their career needs and attain their career goals (Briscoe et al., 2006; Sullivan and Baruch, 2009). Thus, while managers are exerting much effort in identifying strategies to manage demanding business environments, employees have become more driven by their own career needs than by organizational goals. Therefore, it is not surprising that scholars have become increasingly interested in examining how organizational goals can be accomplished through employees’ career attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Fleisher et al., 2014; Dobrev and Merluzzi, 2018).

Recognizing the necessity of this new research approach reveals an important gap in the contemporary career literature that must be further explored and addressed. As part of the contemporary discourse about careers, we know, for example, that organizations can benefit from employees’ career mobility, which brings novel social and human capital (Dobrev and Merluzzi, 2018). We also know that employees’ career competencies, including their career motivation, knowledge, and network, can benefit organizations by strengthening the organizational core competencies of culture, capabilities, and connections (Fleisher et al., 2014). However, little is known about whether and how employees’ ambitions to advance in their careers benefit organizations. This may be partly owing to the negative connotations of ambition, which has been largely associated with individualistic cravings for power and self-interested behavior (Larimer et al., 2007; Pettigrove, 2007). In the present study, we refer to career-related ambitions as career aspirations and acknowledge that such aspirations indeed trigger self-interested behavior. Employees with career aspirations in particular proactively engage in skill-development behaviors and networking behaviors and proactively seek career consultation solely to plan for their careers (Strauss et al., 2012). Despite the self-interested career focus, some of these behaviors (i.e., skill-development and networking behaviors) could potentially positively influence important organization-level outcomes (e.g., Li et al., 2017; Shin and Konrad, 2017); hence, we believe that employees with career aspirations will benefit their employing organizations through their self-interested career behaviors. As this is the first study to focus on understanding the benefits that career aspirations might offer to organizations, we make an important contribution to the contemporary career literature. Next, we aim to highlight the important role that managers play in enhancing the positive effects of employees’ career aspirations on organizations. In line with a recent argument, we believe that although employees are capable of exercising control over their careers, organizations must still support them in achieving their career goals by providing them with human resource (HR) practices or organizational support programs (Jung and Takeuchi, 2018). More specifically, we argue that an empowering work design acts as a high-performance practice (Van De Voorde and Beijer, 2015), providing employees with the opportunities to fulfill their career aspirations, which in turn increases employees’ motivation to address organizational needs. In our understanding of such a work design, we refer to Grant and Parker (2009) work design perspective, which posits that proactive and relational aspects of work are the key characteristics of contemporary jobs. Specifically, the authors argue that due to increases in uncertainty and dynamism in work environments, it has become increasingly important for employees to be proactive and to take charge in anticipating future work needs and addressing them. Employees must also be more active in developing work relationships since interdependence and interactions with coworkers, customers and other stakeholders have increased (Grant and Parker, 2009). As relationship building and taking charge behaviors are both considered to also be proactive career behaviors (e.g., Fuller and Marler, 2009; Tschopp et al., 2016), we are the first to contribute to Grant and Parker (2009) work design perspective and to the HRM literature by demonstrating that contemporary work demands create opportunities for employees to address personal career and organizational needs. To explain our argument from a theoretical perspective, we follow recent work (e.g., Su et al., 2018) employing the Ability, Motivation and Opportunity (AMO) model and social exchange theory to explain why empowering HR practices could trigger employees to reciprocate by contributing to organizational performance. First, the AMO model states that high-performance work practices such as work designs are aimed at empowering employees to perform by enhancing their job-related abilities (A), by increasing their motivation levels (M) and by creating opportunities for them to positively contribute to the organization (O) (Appelbaum et al., 2000). We argue that Grant and Parker (2009) contemporary work design perspective not only enhances performance but also assists employees in fulfilling their career aspirations. For example, as we argue, the proactive aspect of work requires employees to be proactive by engaging in taking charge behaviors (Morrison and Phelps, 1999), which creates opportunities for them to enhance their job-related abilities and to develop career self-management skills. Then, the relational aspect of work provides employees with opportunities to develop instrumental and developmental relationships, affording them access to important resources that are needed to perform effectively and to progress in their careers (Higgins and Thomas, 2001). Second, consistent with the argument of social exchange theory and recent work (e.g., Sung et al., 2017; Su et al., 2018), we argue that employees will feel the need to reciprocate favorable organizational treatment with positive behaviors to benefit their organization (Whitener, 2001). Specifically, we argue that they will be motivated to utilize their job-related abilities and will engage in taking charge behavior to contribute to their organizations’ capabilities. We also argue that they will be motivated to strengthen their organization’s connections by utilizing their instrumental and psychosocial relationships to obtain important resources for the good of their organization. Simply stated, we thus propose that the proactive and relational aspects of work are the mechanisms through which employees with career aspirations contribute to organizations.

Theory and Hypotheses

Fulfilling Employees’ Career Aspirations: Opportunities Provided by Contemporary Work Design

There is a growing number of papers noting that the design of contemporary work is increasingly changing (Wegman et al., 2018). While aspects of work such as autonomy are still very relevant, more papers are suggesting that other aspects of work, such as proactivity, are becoming increasingly relevant in the contemporary workplace (Grant and Parker, 2009). This proactive aspect of work requires that employees adapt to dynamic jobs and contribute to shaping these jobs by introducing changes in the way that work is conducted (Morrison and Phelps, 1999; Frese and Fay, 2001).

To comply with this proactive nature of work, we argue that employees will be motivated to take charge at work, which is a form of proactive behavior that focuses on individual contributions to positive change with respect to the execution of work in organizations (Morrison and Phelps, 1999). By doing so, individuals need to actively seek out new information, identify opportunities for improvements and take action to improve work (Fuller et al., 2006). Therefore, engaging in taking charge behavior offers employees opportunities to gain new knowledge, to develop skills, and also to enhance their abilities, which are needed to perform successfully in higher positions in the future (Metz, 2004). Moreover, as other scholars have argued, proactive individuals who take charge at work will most likely also be better able to take charge of their careers (Fuller and Marler, 2009) and thus better achieve their career goals. Engaging in taking charge behavior could also directly open doors to better career opportunities, as the behavior signals strong leadership potential (Fuller et al., 2007). Considering these points together, we argue that employees with career aspirations will be motivated to take charge at work since doing so supports them in achieving their work and career goals. Therefore, we propose the following:

H1: Employees’ career aspirations will be positively associated with their taking charge behaviors.

Second, according to Grant and Parker (2009), we have also experienced changes in the social context at work, because teams are being used to complete work more frequently than in the past (Osterman, 2000). With this trend, employees are required to coordinate their work within their teams, as well as beyond their teams’ boundaries, with individuals and teams from different departments and organizations (Howard, 1995; Mohrman et al., 1995; Griffin et al., 2007). With the growing service sector, employees have also become responsible for addressing the needs of more demanding stakeholders (e.g., Schneider and Bowen, 1995; Batt, 2002; Grant and Parker, 2009), which requires that employees also proactively develop relationships outside their organizations. In other words, internal and external relationships have become more widespread and important in contemporary jobs.

This relational aspect of work offers opportunities for employees with career aspirations to develop relationships with influential individuals from inside and outside their employing organizations who can help them to progress and advance in their careers. Such relationships are called instrumental relationships and are especially beneficial for careers because they provide employees with important job-related information and resources (Higgins and Thomas, 2001). Indeed, research has demonstrated that being connected to influential individuals offers many career-related benefits, such as salary growth (Wolff and Moser, 2009), higher supervisor-rated promotion evaluations (Lin and Huang, 2005; Huang, 2016), more job-related knowledge (Forret and Dougherty, 2004), and more external job offers (Wolff and Moser, 2010). Therefore, we propose that employees with career aspirations will develop and use their instrumental relationships because such relationships can assist them in achieving their work and career goals.

H2: Employees’ career aspirations will be positively associated with their instrumental relationships.

Additionally, we also propose that employees with career aspirations will be motivated to develop psychosocial relationships at work. Such relationships are developed to gain emotional and appraisal support during one’s career and include role modeling, counseling and friendship (Higgins and Thomas, 2001). When employees set high career goals, they can have an unrealistic approach to career expectations, which could result in work-related stress (Van Emmerik et al., 2005), especially if they are not able to fulfill their personal expectations. Therefore, such employees are likely to be in need of role models who can offer them psychosocial support and help them reduce stress and other negative work-related outcomes such as exhaustion or burn-out. For instance, through psychosocial relationships, mentors can enhance employees’ sense of competence and self-esteem (Seibert, 1999; Ragins and Kram, 2007). They can also enhance employee resilience, an ability that is considered to be effective in maintaining employee well-being during high-pressure work situations (Ferris et al., 2005; Kao et al., 2014). In difficult times, such positive outcomes can motivate employees to pursue their career ambitions. Therefore, we formulate the following:

H3: Employees’ career aspirations will be positively associated with their psychosocial relationships.

Employees’ Contributions to Organizations: The Roles of Proactive and Relational Aspects of Contemporary Work

Based on the AMO model, we employed Grant and Parker’s (2009) work design perspective to argue that it supports employees in fulfilling their career aspirations by developing their abilities, enhancing their motivation to pursue their career ambitions and by offering more and better career opportunities. Following social exchange theory, we now argue that employees with career aspirations will feel a sense of obligation to reciprocate by contributing positively to organizational capabilities and connections. As previously explained, we argue that the proactive and relational nature of work will provide employees with the opportunities to do so. Organizational capabilities refer to the knowledge and skills that are embodied in organizational activities (Quinn, 1992) and are strengthened when employees accumulate new skills and capabilities and utilize them for the good of the organization (Teece et al., 1997; Khapova et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2012). As previously argued, when employees take charge at work, they will most likely gain new knowledge and develop better skills; therefore, these employees will be better able to develop strategies to render work processes more effective and efficient (Wright et al., 1994) and to enhance productivity (Shin and Konrad, 2017). In line with this argument, Wu et al. (2014) found that new ideas and approaches facilitate product development and better ways of doing things in the workplace. Similarly, Yang et al. (2016) provide relevant evidence by showing that, when frontline bank employees creatively apply their knowledge to service procedures, they can help achieve innovation and enhance overall service performance. Therefore, we propose the following:

H4: Employees’ taking charge behaviors will be positively associated with their contribution to organizational capabilities.

Organizational connections, then, refer to the external contacts of organizations, such as suppliers, customers, alliances, and other stakeholders (Quinn, 1992). Organizational connections are likely to be strengthened when employees utilize their personal contacts to benefit their employing organizations (Khapova et al., 2009). Su et al. (2009) demonstrate, for example, that employees can acquire information from their personal relationships with customers and utilize it to contribute to positive organizational outcomes, such as product innovation. In a similar vein, Heirati et al. (2013) provide evidence that overall firm performance can be enhanced when employees utilize important market-related knowledge obtained from their personal ties with other firms, governmental officials and academic institutions. Consistent with the latter point, a recent study of Chinese firms in the manufacturing sector indicates that political and innovative economic stakeholders positively influence a firm’s innovative performance (Li et al., 2017), likely because employees can obtain information about important government regulations and innovation policies from their personal ties with political stakeholders and utilize this information to enhance their organizations’ innovative performance. Similarly, employees can obtain information from their relationships with competitors, suppliers, and buyers and utilize this information to develop better products and services for their employing organizations (Li et al., 2017). Therefore, the following two hypotheses are set:

H5: Employees’ instrumental relationships will be positively associated with their contribution to organizational connections.

H6: Employees’ psychosocial relationships will be positively associated with their contribution to organizational connections.

Mediating Effects

We have argued that employees’ career aspirations are positively associated with their taking charge behaviors and instrumental and psychosocial relationships and that the latter strengthen organizational capabilities and connections. Building on these points, we also propose that the proactive and relational aspects of work are mechanisms through which employees’ career aspirations add value to organizations. This proposal is consistent with recent findings demonstrating that antecedents of firm performance are indirectly associated with actual firm performance through employees’ capabilities and behaviors (e.g., Shanker et al., 2017; Ashford et al., 2018). It is also in line with recent studies demonstrating that employees positively contribute to organizations through the resources that they obtain from their networks (e.g., Liu et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2018). Therefore, the following three hypotheses are set:

H7: Taking charge behavior mediates the relationship between employees’ career aspirations and their individual contribution to organizational capabilities.

H8: Instrumental relationships mediate the relationship between employees’ career aspirations and their individual contribution to organizational connections.

H9: Psychosocial relationships mediate the relationship between employees’ career aspirations and their individual contribution to organizational connections.

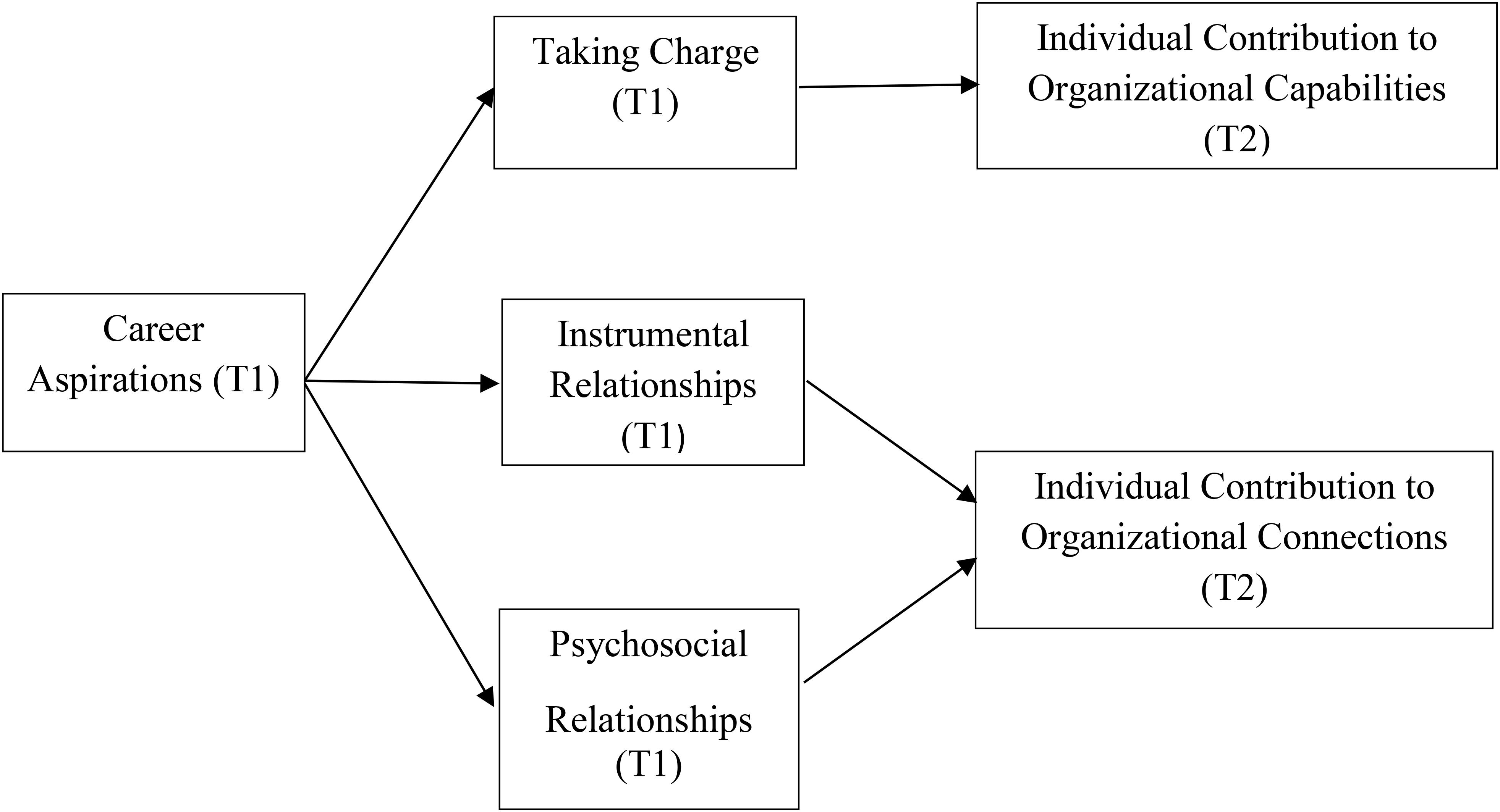

Figure 1 provides an overview of all hypotheses.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

This study was initiated at a public university in the Netherlands. A web-based survey covering concepts such as work attitudes, career-related behaviors, and background factors was sent to a total of 4,880 business and economics graduates. The survey was sent at two time points with a 1-year time lag, in line with the suggestions of other scholars who argue that employee behaviors in work contexts should be examined with a 1-year time lag (Koys, 2001). Specifically, at time 1, the university was provided with a preliminary Microsoft Excel spreadsheet consisting of contact information from 2,000 graduates. At time 2, the contact information of the alumni group was completed; hence, the survey could be sent to an additional 2,880 potential candidates. At time 1, 558 graduates returned completed surveys, resulting in a response rate of 28%. At time 2, the response rate was 11%, since only 555 graduates returned completed surveys. The final sample (N = 181) consists only of participants who had completed the survey at times 1 and 2, who had graduated at least 1 year before the first survey was sent and who were employed at times 1 and 2. Thus, aside from normal attrition, the drop-outs were retirees, unemployed graduates and those not interested in participating in the project. The final sample (N = 181) consists of graduates holding job positions in different professional fields and industries such as management consultancy, HR management, accounting, and finance. Seventy-seven percent of the total sample was male, and the respondents were predominantly of Dutch nationality, with an average age of 37.7 years old (at time 1).

Measures

Unless stated otherwise, abbreviated versions of the original scales were used, consisting solely of items fitting conceptually in the definitions of our study variables. In line with prior research using abbreviated versions of original scales (e.g., Leijten et al., 2015), we determined whether exploratory factor analysis revealed sufficient factor loadings for the selected items. The factor loadings ranged from 0.50 to 0.75 and could be considered sufficient for our sample size (N = 181) (Hair et al., 2010; Leijten et al., 2015). Additionally, the Cronbach’s alphas demonstrated that all of the scales were reliable (α > 0.77).

Career Aspirations

Five items from a scale developed by Gray and O’Brien (2007) were used to measure career aspirations. Example items include “I hope to become a leader in my career field,” “When I am established in my career, I would like to manage other employees,” and “I hope to move up through any organization or business in which I work” (1 = “strongly disagree” and 5 = “strongly agree”) (Baroudi, 2016, p. 88). The item scores were averaged to form total scores for career aspirations (T1 α = 0.77; T2 α = 0.78).

Taking Charge

Participants responded to Morrison and Phelps (1999) 10-item scale measuring taking charge. The items prefaced with “In my job, I often…” read as follows: “…try to adopt improved procedures for performing my job”; “…try to correct a faulty procedure or practice”; and “…try to implement solutions to pressing organizational problems.” A five-point scale was used, ranging from 1, “I strongly disagree” to 5 “I strongly agree,” with an option of “non-applicable” (Baroudi, 2016, p. 88). The item scores were averaged to form total scores for taking charge (T1 α = 0.91; T2 α = 0.91).

Instrumental Relationships

To measure instrumental relationships, seven items were used from a scale developed by Higgins (2001). The items prefaced with “In my network of relationships, I have people who…” read as follows: “…provide useful experiences for me professionally”; “…provide me with opportunities that benefit me professionally”; and “…open doors for me professionally” (1 = “not at all” and 5 = “to a great extent”) (Baroudi, 2016, p. 88). The item scores were averaged to form total scores for instrumental relationships (T1 α = 0.92; T2 α = 0.92).

Psychosocial Relationships

To measure psychosocial relationships, six items were used from Higgins and Thomas (2001) scale. The items prefaced with “In my network of relationships, I have people who…” read as follows: “…coach me on difficult work-related issues”; “…counsel me on work- and non-work-related issues”; and “…frequently act as supporters” (1 = “not at all” and 5 = “to a great extent”) (Baroudi, 2016, p. 88). Again, the item scores were averaged to form total scores for psychosocial relationships (T1 α = 0.90; T2 α = 0.89).

Individual Contribution to Organizational Capabilities

The participants also completed Khapova et al. (2009) (in Fleisher et al., 2014), eight-item scale measuring individuals’ contributions to organizational capabilities. Example items include “I try to use my external experiences to improve existing ways of doing things in my organization” and “I try to use what I learn outside my organization in my work” (Baroudi, 2016, p. 89). The respondents used a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “I strongly disagree” to 5 “I strongly agree.” The item scores were averaged to form total scores for individuals’ contributions to organizational capabilities (T1 α = 0.80; T2 α = 0.81).

Individual Contribution to Organizational Connections

The participants completed five items from Khapova et al. (2009) scale (in Fleisher et al., 2014). The items prefaced with “In my work…” read as follows: “…my external contacts assist me in work-related problem solving” and “I utilize knowledge generated from my external professional activities” (1 = “strongly disagree” and 5 = “strongly agree”). Item scores were averaged to form total scores for individual contributions to organizational connections (T1 α = 0.84; T2 α = 0.83).

Control Variables

Following the recommendations of Carlson and Wu (2012), we looked for demographic variables that have significant correlations with our study variables to include them as control variables. Only gender and age were found to meet the requirement; therefore, other demographic variables were omitted from our statistical analyses. Indeed, in prior studies, gender was found to have associations with career aspirations such that fathers were more likely to consider promotion to be the most important career aspiration, compared to mothers (van der Horst et al., 2014). Age was also found to influence career advancement motives in another study such that motives were found to decrease when employees’ age increased (Kooij et al., 2011). Older employees were also found to build work relationships to help others, rather than utilize the relationships to fulfill career needs (Kooij et al., 2011). Age was also found to positively influence the quality of organizational performance in prior work (Backes-Gellner et al., 2011). Finally, including gender and age as control variables is also consistent with prior research examining the effects of antecedents on taking charge behaviors (Morrison and Phelps, 1999; Burnett et al., 2015). Gender was recorded as a dummy variable (i.e., male = 1 and female = 2) in our statistical analyses.

Statistical Analysis

To examine the validity of the measurement model, we ran a confirmatory factor analysis in which we included all of our main variables. The results demonstrated a good model fit (χ2 = 1166.08, df = 764, RMSEA = 0.05, NFI, CFI = 0.96) (e.g., Hu and Bentler, 1999; Hooper et al., 2008), indicating that each measure had a good level of convergent and discriminant factorial validity. Given that all of the measures in the model were self-reported from a single survey, we also tested for common method variance. Following the recommendation of Podsakoff et al. (2012), the procedure involved comparing alternative models as well as adding a latent common method variable. In this case, the baseline proposed model also obtained a better fit, suggesting that common method variance did not inordinately influence our results. To test the direct and mediated effects formulated in our hypotheses, we used Process (version 2.15) in IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 24. Process assesses mediation effects based on bias-corrected confidence intervals obtained from 5,000 bootstrapped estimates of each required path (Hayes, 2009). To investigate the effects of the mediators (i.e., taking charge, instrumental, and psychosocial relationships) on the relationship between career aspirations and individuals’ contribution to organizational capabilities and connections, we included the mediators of T1 in our analyses. This approach is in line with prior work investigating mediation effects with two waves (e.g., Solove et al., 2015). Finally, in line with prior longitudinal research, we included the control variables of T1 in all of our analyses (i.e., gender and age) (Tims et al., 2015).

Results

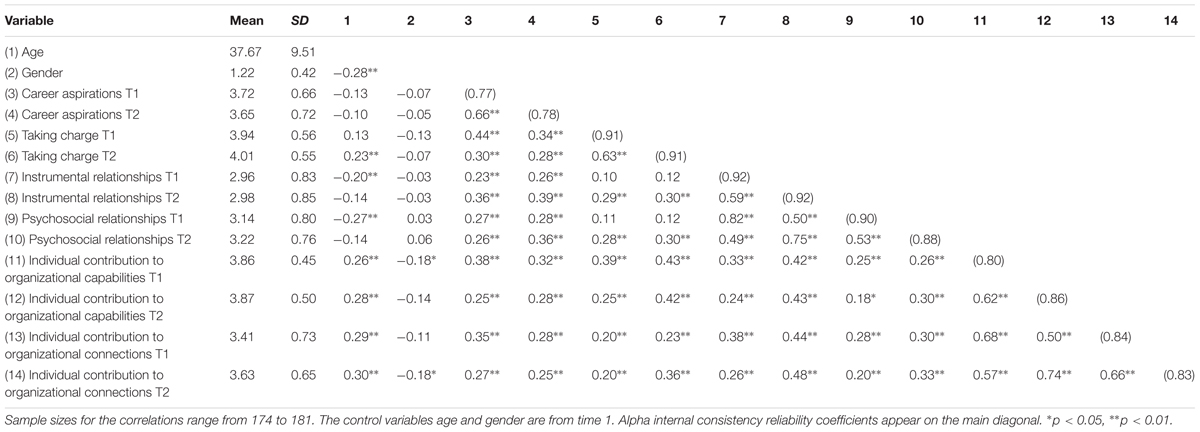

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations for all of the study variables. The study variables were all positively correlated, except for taking charge (T1 + T2), which was not related to instrumental and psychosocial relationships (T1). The control variable age was negatively related to gender and instrumental and psychosocial relationships (T1) but positively related to taking charge (T2), individual contribution to organizational capabilities (T1 + T2) and individual contribution to organizational connections (T1 + T2). Gender was negatively related to individual contribution to organizational capabilities (T1) and individual contribution to organizational connections (T2).

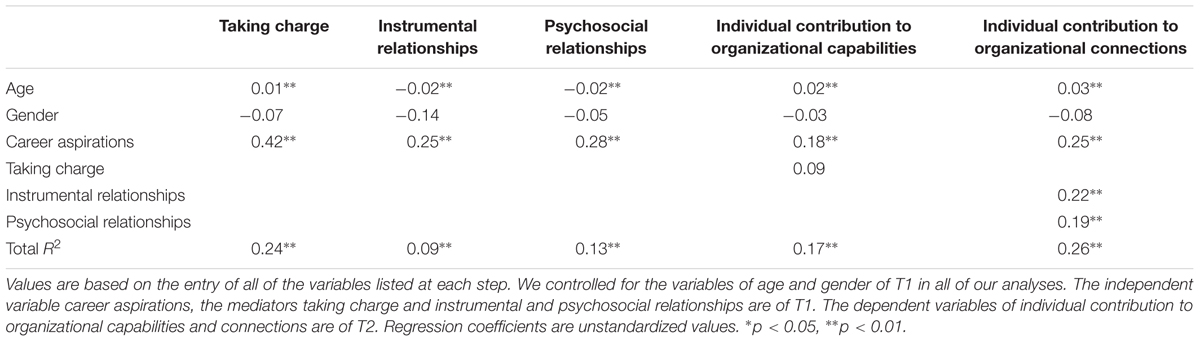

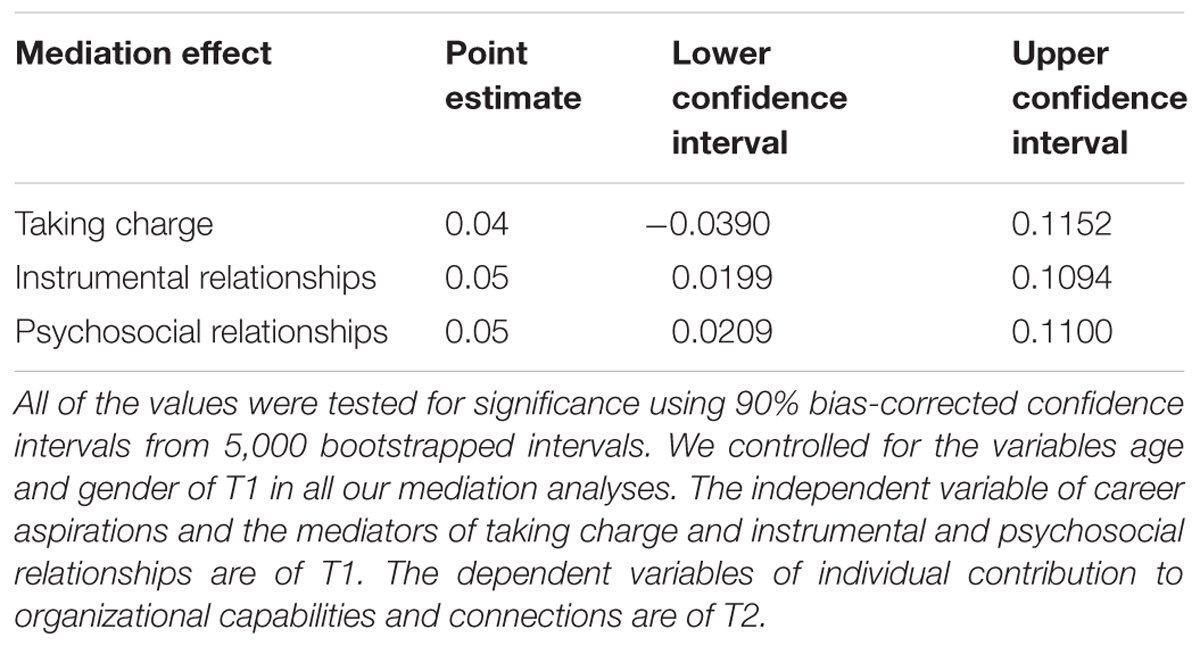

Results of the mediation analyses are reported in Tables 2, 3. Support was found for Hypothesis 1, which stated that employees’ career aspirations are positively related to employees’ taking charge behavior (b = 0.42, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 2, which stated that employees’ career aspirations are positively related to instrumental relationships, was also supported (b = 0.25, p < 0.01). The results also supported Hypothesis 3, which stated that employees’ career aspirations are positively related to psychosocial relationships (b = 0.28, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 4, which stated that employees’ taking charge behavior is positively related to employees’ contribution to organizational capabilities was not supported (b = 0.09, p > 0.05). Hypotheses 5 and 6, which stated that employees’ instrumental and psychosocial relationships are positively related to employees’ contributions to organizational connections, were supported (b = 0.22, p < 0.01) and (b = 0.19, p < 0.01). Moreover, although not formulated as hypotheses, Table 2 shows that employees’ career aspirations are positively related to the dependent variables of individual contribution to organizational capabilities (b = 0.18, p < 0.01) and connections (b = 0.25, p < 0.01). Table 3 shows the results of our mediation hypotheses 7–9. Hypothesis 7, which stated that employees’ taking charge behavior mediates the relationship between employees’ career aspirations and their individual contribution to organizational capabilities, was not supported. The indirect effect of taking charge behavior (0.04) is not significant within a 90% confidence interval of -0.0390 to 0.1152. Support was found for Hypothesis 8. The indirect effect of employees’ instrumental relationships (0.05) on the relationship between employees’ career aspirations and their individual contribution to organizational connections is significant within a 90% confidence interval of 0.0199 to 0.1094. Finally, the indirect effect of employees’ psychosocial relationships (0.05) on the relationship between employees’ career aspirations and their individual contribution to organizational connections (i.e., Hypothesis 9) was also significant within a 90% confidence interval of 0.0209 to 0.1100.

Discussion

Our study aimed to develop and examine a theoretical model (Figure 1) of (1) the link between employees’ career aspirations and their contributions to organizations; and (2) the mechanisms (i.e., proactive and relational aspects of contemporary work) underlying this link. The study results confirm that employees with career aspirations contribute to strengthening: (a) organizational capabilities; and (b) organizational connections through their instrumental and psychosocial relationships. Interestingly, although career aspirations were positively associated with taking charge, we did not find that taking charge predicts employees’ individual contributions to organizational capabilities. Hence, a mediating effect of taking charge on the direct relationship between employees’ career aspirations and their individual contributions to organizational capabilities was also not found. Based on these results, we make a number of significant contributions.

The first contribution concerns the link between employees’ career aspirations and their contribution to organizations. While recent studies have demonstrated how employees’ career mobility benefits organizations (Dobrev and Merluzzi, 2018) and how organizational career management, as well as individual career investments, are beneficial for firm performance (Crook et al., 2011; De Vos and Cambré, 2017), we extend support for this reasoning by demonstrating that employees’ career aspirations also strengthen organizational capabilities and connections. To date, research has examined career aspirations of high school and university students to understand and influence their future career paths (e.g., Schoon and Polek, 2011; Kitchen et al., 2017). For instance, more recently, insufficient student interest in STEM careers has prompted scholars to examine students’ career aspirations and to identify effective strategies to inspire more students to pursue STEM careers (e.g., Kitchen et al., 2017; Holmes et al., 2018). Contributing to this recent work, our results suggest that career aspirations are not only useful for influencing students’ future careers but are also an important force for achieving positive organizational outcomes.

Our findings also contribute to the understanding of the proactive and relational aspects of contemporary work according to Grant and Parker’s (2009) work design perspective and to the HRM literature focusing on demonstrating the effects that high-performance practices have on employees’ willingness to contribute to organizations (e.g., Jeong and Shin, 2017; Shin and Konrad, 2017). We demonstrate that the relational aspect is an important mechanism explaining the positive relationships between employees’ career aspirations and their contributions to organizational connections. Interestingly, although findings show that employees with career aspirations engage in more taking charge behaviors, this fact does not subsequently lead to a contribution to organizational capabilities. We assume that this finding can be partly ascribed to the behavior itself, as taking charge is often considered to be a risky behavior and, hence, requires careful nurturing (Burnett et al., 2015). Employees could engage in taking charge behavior to fulfill their career aspirations, but when they decide to utilize their taking charge experience to contribute to their employing organization, they could fear that their manager and even the top management may perceive their effort as threatening rather than positive. Therefore, we recommend future research to examine the influence of organizational support on the mediated relationship among employees’ career aspirations, their taking charge behaviors and their individual contribution to organizational capabilities. By doing so, special attention should be paid to employee perceptions of fairness regarding the distribution of other HR practices (next to work design) since doing so might also influence employees’ willingness to contribute to organizational performance (Vanhala and Ritala, 2016).

Finally, returning to our findings regarding the relational aspect, we find this aspect to be an important mechanism explaining the positive relationship between employees’ career aspirations and their contributions to organizational connections. Specifically, we find that employees’ career aspirations are positively associated with their instrumental and psychosocial relationships, which are in turn both beneficial to organizations. These findings are consistent with prior work demonstrating that employees can obtain important resources from their relationships and utilize them for the good of their company (e.g., Su et al., 2009; Heirati et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017). However, we extend this work by specifying the type of employees that are likely to do so (i.e., career ambitious employees). Moreover, we also demonstrate that, although employees develop different types of relationships to achieve different career goals, such relationships appear to involve a more unified role for achieving positive organizational outcomes. Consistent with recent work on career relationships (Van Vianen et al., 2018), we thus show that it is worthwhile to focus on examining the effects of career relationships at distinguished organizational levels (i.e., individual and organization levels).

Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite the significant contributions, we acknowledge that this study has some limitations that must be addressed in future research. For instance, we used two waves of data to examine mediation effects in relationships in which the independent variable and mediators are from time 1, and the dependent variables are from time 2. According to other scholars, this process means that the results cannot be interpreted causally and that the real direction of effects is possibly counter to the hypothesized effects (Holman et al., 2012). A natural follow-up to this study would be to examine similar mediation predictions using a design in which the independent variable, mediators and dependent variables are from different time points. Three waves of data would allow for time 1 data to be used for the predictor (X), time 2 data to be used for the mediator (M), and time 3 data to be used for the outcome variable (Y) (Rose et al., 2004), thus making it possible to better distinguish between causes and effects (Cole and Maxwell, 2003; Baroudi et al., 2017). Another limitation concerns the reliance on self-reported data in our measurements. Measuring relationships between variables with self-reported surveys only could result in inflation due to mono-method bias or common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2012; Baroudi, 2016). We minimized concerns about inflated relationships in our study because we tested for common method variance following the recommendation of Podsakoff et al. (2012). The results suggested that common method variance does not inordinately affect the study findings. Nevertheless, more objective measures could be used in future studies examining similar predictions to better ensure that the results are unbiased (Holman et al., 2012). A third limitation of our study concerns our statistical analytical approach. Researchers have suggested that techniques such as structural equation modeling (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 1993) might be more appropriate for testing mediation models with longitudinal data. However, as a limitation, such techniques require larger samples to observe significant changes in effects (e.g., Finch et al., 1997; Fan and Wang, 1998). To overcome weak mediation analyses and results (Dudley et al., 2004), we followed prior work and tested our mediation hypotheses using bias-corrected confidence intervals from 5,000 bootstrapped intervals (e.g., Baroudi et al., 2017). According to Williams and MacKinnon (2008) and Clifford et al. (2017), bootstrapping is a robust method for testing the effects of mediating variables. Nevertheless, we recommend that future researchers test our mediation predictions using structural equation modeling and a larger sample to augment our research results and conclusions.

Practical Implications

A key practical implication of this study is that managers should utilize HRM practices effectively to motivate employees not only to follow their career aspirations but also to utilize their personal resources for the good of the organization. For instance, this study suggests that managers should aim to recruit career ambitious employees and retain them, as this group of employees contributes to making organizations strong by strengthening organizational capabilities and organizational connections. The work design of such employees also plays an important role because the relational aspect of work was found to benefit career ambitious employees and their employing organizations. However, attention should be devoted to the proactive aspect of work, as employees with career aspirations do engage in taking charge behavior but do not use this experience to contribute to their organization’s capabilities. Therefore, we recommend that managers encourage employees to orient their taking charge behaviors toward benefiting the organization (Griffin et al., 2007), by for example rewarding employees’ proactive efforts and behaviors.

Ethics Statement

For this study, ethics approval was not required per the Vrije Universiteit’s guidelines and national regulations. Nevertheless, the research was conducted in line with the Research Ethics Regulations of the School of Business and Economics of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. All of the participants were voluntarily involved in the study. Emails were sent to the participants, in which the purpose and procedures of the study were described and in which their approval was asked for participation in the study. The online survey included a consent form with all of the necessary information that participants had to read and approve prior to proceeding with the survey. Moreover, the participants were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time. The participants who decided to withdraw from the study were not included in the final sample, and their data were destroyed.

Author Contributions

SB was involved in conception and design of the study, in the data collection and analysis, and in the manuscript writing. SK was involved in conception and design of the study, the data collection and manuscript writing and approved the submitted version. CF was involved in the data collection and analysis. PJ was involved in the data analysis and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) under project number 017.006.076.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the Ph.D. thesis of SB, directed by SK and PJ in the Department of Management and Organisation at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in Amsterdam, the sNetherlands.

References

Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P., and Kalleberg, A. L. (2000). Manufacturing Advantage: Why High-Performance Work Systems Pay Off. Ithaca. New York, NY: Cornell University Press.

Ashford, S. J., Wellman, N., de Luque, M. S., de Stobbeleir, K. E. M., and Wollan, M. (2018). Two roads to effectiveness: CEO feedback seeking, vision articulation, and firm performance. J. Organ. Behav. 39, 82–95. doi: 10.1002/job.2211

Backes-Gellner, U., Schneider, M., and Veen, S. (2011). Effect of workforce age on quantitative and qualitative organizational performance: conceptual framework and case study evidence. Organ. Stud. 32, 1103–1121. doi: 10.1177/0170840611416746

Baroudi, S. E., Fleisher, C., Khapova, S. N., Jansen, P. G. W., and Richardson, J. (2017). Ambition at work and career satisfaction. The mediating role of taking charge behavior and the moderating role of pay. Career Dev. Int. 22, 87–102. doi: 10.1108/CDI-07-2016-0124

Baroudi, S. E. (2016). Shading a Fresh Light on Proactivity Research. Examining When and How Proactive Behaviors Benefit Individuals and Their Employing Organizations. Dissertation thesis, Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit.

Batt, R. (2002). Managing customer services: human resource practices, quit rates, and sales growth. Acad. Manage. J. 45, 587–597. doi: 10.5465/3069383

Briscoe, J. P., Hall, D. T., and DeMuth, R. L. F. (2006). Protean and boundaryless careers: an empirical exploration. J. Vocat. Behav. 69, 30–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2005.09.003

Burnett, M. F., Chiaburu, D. S., Shapiro, D. L., and Li, N. (2015). Revisiting how and when perceived organizational support enhances taking charge: an inverted u-shaped perspective. J. Manage. 41, 1–22. doi: 10.1177/0149206313493324

Carlson, K. D., and Wu, J. (2012). The illusion of statistical control: control variable practice in management research. Organ. Res. Methods 15, 413–435. doi: 10.1177/1094428111428817

Clifford, C., Vennum, A., Busk, M., and Fincham, F. (2017). Testing the impact of sliding versus deciding in cyclical and non-cyclical relationships. Pers. Relationsh. 24, 233–238. doi: 10.1111/pere.12179

Cole, D. A., and Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 112, 558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558

Crook, T. R., Todd, S. Y., Combs, J. G., Woehr, D. J., et al. (2011). Does human capital matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship between human capital and firm performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 96, 443–456. doi: 10.1037/a0022147

De Vos, A., and Cambré, B. (2017). Career management in high performing organizations: a set theoretic approach. Hum. Resour. Manage. 56, 501–518. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21786

Dobrev, S. D., and Merluzzi, J. (2018). Stayers versus movers: social capital and early career imprinting among young professionals. J. Organ. Behav. 39, 67–81. doi: 10.1002/job.2210

Dudley, W. N., Benuzillo, J. G., and Carrico, M. S. (2004). SPSS and SAS programming for the testing of mediation models. Nurs. Res. 53, 59–62. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200401000-00009

Fan, X., and Wang, L. (1998). Effects of potential confounding factors on fit indices and parameter estimates for true and misspecified models. Struct. Equat. Model. 5, 701–735. doi: 10.1177/0013164498058005001

Ferris, P. A., Sinclair, C., and Kline, T. J. (2005). It takes two to tango: personal and organizational resilience as predictors of strain and cardiovascular disease risk in a work sample. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 10, 225–238. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.3.225

Finch, J. F., West, S. G., and MacKinnon, D. P. (1997). Effects of sample size and non- normality on the estimation of mediated effects in latent variable models. Struct. Equat. Model. 4, 87–105. doi: 10.1080/10705519709540063

Fleisher, C., Khapova, S. N., and Jansen, P. G. W. (2014). Effects of employees’ career competencies development on their organizations. Does satisfaction matter? Career Dev. Int. 19, 700–717. doi: 10.1108/CDI-12-2013-0150

Forret, M. L., and Dougherty, T. W. (2004). Networking behaviors and career outcomes: differences for men and women? J. Organ. Behav. 25, 419–437. doi: 10.1002/job.253

Frese, M., and Fay, D. (2001). Personal initiative: an active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Res. Organ. Behav. 23, 133–187. doi: 10.1016/S0191-3085(01)23005-6

Fuller, B. Jr., and Marler, L. E. (2009). Change driven by nature: a meta-analytic review of the proactive personality literature. J. Vocat. Behav. 75, 329–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.05.008

Fuller, J. B., Barnett, T., Hester, K., Relyea, C., and Frey, L. (2007). An exploratory examination of voice behavior from an impression management perspective. J. Managerial Issues 19, 134–151.

Fuller, J. B., Marler, L. E., and Hester, K. (2006). Promoting felt responsibility for constructive change and proactive behavior. Exploring aspects of an elaborated model of work design. J. Organ. Behav. 27, 1089–1120. doi: 10.1002/job.408

Grant, A. M., and Parker, S. K. (2009). Redesigning work design theories: the rise of relational and proactive perspectives. Acad. Manage. Ann. 3, 317–375. doi: 10.1080/19416520903047327

Gray, M. P., and O’Brien, K. M. (2007). Advancing the assessment of women’s career choices: the career aspirations scale. J. Career Assess. 15, 317–337. doi: 10.1177/1069072707301211

Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., and Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance, positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Acad. Manage. J. 50, 327–347. doi: 10.5465/amj.2007.24634438

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond baron and kenny: statistical mediation in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 76, 408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360

Heirati, N., O’ Cass, A., and Ngo, L. V. (2013). The contingent value of marketing and social networking capabilities in firm performance. J. Strateg. Market. 21, 82–98. doi: 10.1080/0965254X.2012.742130

Higgins, M. C. (2001). Changing careers: the effects of social context. J. Organ. Behav. 22, 595–618. doi: 10.1002/job.104

Higgins, M. C., and Thomas. D. A. (2001). Constellations and careers: toward understanding the effects of multiple developmental relationships. J. Organ. Behav. 22, 223–247. doi: 10.1002/job.66

Holman, D., Totterdell, P., Axtell, C., Stride, C., Port, R., Svensson, R., et al. (2012). Job design and the employee innovation process: the mediating role of learning strategies. J. Bus. Psychol. 27, 177–191. doi: 10.1007/s10869-011-9242-5

Holmes, K., Gore, J., Smith, M., and Lloyd, A. (2018). An integrated analysis of school students’ aspirations for STEM careers: which student and school factors are most predictive? Int. J. Sci. Mathemat. Educ. 16, 655–675. doi: 10.1007/s10763-016-9793-z

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., and Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 6, 53–60.

Howard, A. (1995). “A framework for work change,” in The Changing Nature of Work: 3-44, ed. A. Howard (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass).

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equat. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang, Y. M. (2016). Networking behavior: from goal orientation to promotability. Pers. Rev. 45, 907–927. doi: 10.1108/PR-03-2014-0062

Jeong, I., and Shin, S. J. (2017). High-performance work practices and organizational creativity during organizational change: a collective learning perspective. J. Manage. 1–17. doi: 10.1177/0149206316685156

Jiang, X., Lui, H., Fey, C., and Jiang, F. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation, network resource acquisition and firm performance: a network approach. J. Bus. Res. 87, 46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.02.021

Jöreskog, K. G., and Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the Simplis Command Language, Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International Inc.

Jung, Y., and Takeuchi, N. (2018). A lifespan perspective for understanding career self-management and satisfaction: the role of developmental human resource practices and organizational support. Hum. Relat. 71, 73–102. doi: 10.1177/0018726717715075

Kao, K. Y., Rogers, A., Spitzmueller, C., Lin, M. T., and Lin, C. H. (2014). Who should serve as my mentor? The effects of mentor’s gender and supervisory status on resilience in mentoring relationships. J. Vocat. Behav. 85, 191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2014.07.004

Khapova, S. N., Arthur, M. B., and Fleisher, C. (2009). Employees meanings of work, career investments and organizational learning. Paper Presented at the Academy of Management, Chicago, IL.

Kitchen, J. A., Sonnert, G., and Sadler, P. M. (2017). The impact of college- and university-run high school summer programs on students’ end of high school STEM career aspirations. Sci. Educ. 102, 529–547. doi: 10.1002/sce.21332

Kooij, D., De Lange, A. H., Jansen, P. G. W., Kanfer, R., and Dikkers, J. S. (2011). Age and work-related motives: results of a meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 32, 197–225. doi: 10.1002/job.665

Koys, D. J. (2001). The effects of employee satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior, and turnover on organizational effectiveness: a unit-level, longitudinal study. Pers. Psychol. 54, 101–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00087.x

Larimer, C. W., Hannagan, R., and Smith, K. B. (2007). Balancing ambition and gender among decision makers. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 614, 56–73. doi: 10.1177/0002716207305272

Leijten, F. R. M., van den Heuvel, S. G., van der Beek, A. J., Ybema, J. F., Robroek, S. J. W., and Burdorf, A. (2015). Associations of work-related factors and work engagement with mental and physical health: a 1-year follow-up study among older workers. J. Occup. Rehabil. 25, 86–95. doi: 10.1007/s10926-014-9525-6

Li, J., Xia, J., and Zajac, E. J. (2017). On the duality of political and economic stakeholder influence on firm innovation performance: theory and evidence from Chinese firms. Strategic Manage. J. 39, 193–216. doi: 10.1002/smj.2697

Lin, S. C., and Huang, Y. M. (2005). The role of social capital in the relationship between human capital and career mobility. J. Intell. Capital 6, 191–205. doi: 10.1108/14691930510592799

Liu, X., Huang, Q., Dou, J., and Zhao, X. (2017). The impact of informal social interaction on innovation capability in the context of buyer-supplier dyads. J. Bus. Res. 78, 314–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.12.027

Metz, I. (2004). Do personality traits indirectly affect women’s advancement? J. Manage. Psychol. 19, 695–707. doi: 10.1108/02683940410559383

Mohrman, S. A., Cohen, S. G., and Mohrman, A. M. Jr. (1995). Designing Team-Based Organizations: New Forms for Knowledge and Work. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Morrison, E. W., and Phelps, C. C. (1999). Taking charge at work: extra-role efforts to initiative workplace change. Acad. Manage. J. 42, 403–419.

Osterman, P. (2000). Work reorganization in an era of restructuring: trends in diffusion and effects on employee welfare. Ind. Lab. Relat. Rev. 53, 179–196. doi: 10.1177/001979390005300201

Pettigrove, G. (2007). Ambitions. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 10, 53–68. doi: 10.1007/s10677-006-9044-4

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63, 539–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Quinn, J. B. (1992). The intelligent enterprise a new paradigm. Executive 6, 48–63. doi: 10.5465/ame.1992.4274474

Ragins, B. R., and Kram, K. E. (2007). The Handbook of Mentoring at Work: Theory, Research and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rose, B. M., Holmbeck, G. N., Coakley, R. M., and Franks, E. A. (2004). Mediator and moderator effects in developmental and behavioral pediatric research. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 25, 58–67. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200402000-00013

Schneider, B., and Bowen, D. E. (1995). Winning the Service game. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Schoon, I., and Polek, E. (2011). Teenage career aspirations and adult career attainment: the role of gender, social background and general cognitive ability. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 35, 210–217. doi: 10.1177/0165025411398183

Seibert, S. (1999). The effectiveness of facilitated mentoring: a longitudinal quasi- experiment. J. Vocat. Behav. 54, 483–502. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1998.1676

Shanker, R., Bhanugopan, R., Van der Heijden, B. I., and Farrell, M. (2017). Organizational climate for innovation and organizational performance: the mediating effect of innovative work behavior. J. Vocat. Behav. 100, 67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.02.004

Shin, D., and Konrad, A. M. (2017). Causality between high-performance work systems and organizational performance. J. Manage. 43, 973–997. doi: 10.1177/0149206314544746

Solove, E., Fisher, G. G., and Kraiger, K. (2015). Coping with job loss and reemployment. A two-wave study. J. Bus. Psychol. 30, 529–541. doi: 10.1007/s10869-014-9380-7

Strauss, K., Griffin, M. A., and Parker, S. K. (2012). Future work selves: how salient hoped-for identities motivate proactive career behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 97, 580–598. doi: 10.1037/a0026423

Strauss, K., Griffin, M. A., Parker, S. K., and Mason, C. M. (2015). Building and sustaining proactive behaviors: the role of adaptivity and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Psychol. 30, 63–72. doi: 10.1007/s10869-013-9334-5

Su, Y. S., Tsang, E. W. K., and Peng, M. W. (2009). How do internal capabilities and external partnerships affect innovativeness? Asia Pacific J. Manage. 26, 309–331. doi: 10.1007/s10490-008-9114-3

Su, Z. X., Wright, P. M., and Ulrich, M. D. (2018). Going beyond the SHRM paradigm: examining four approaches to governing employees. J. Manage. 44, 1598–1619. doi: 10.1177/0149206315618011

Sullivan, S. E., and Baruch, Y. (2009). Advances in career theory and research: a critical review and agenda for future exploration. J. Manage. 35, 1542–1571. doi: 10.1177/0149206309350082

Sung, S. Y., Choi, J. N., and Kang, S. C. (2017). Incentive pay and firm performance: moderating roles of procedural justice climate and environmental turbulence. Hum. Resour. Manage. 80, 1–19. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21765

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., and Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Manage. J. 18, 509–533. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-SMJ882<3.0.CO;2-Z

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., and Derks, D. (2015). Job crafting and job performance: a longitudinal study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 24, 914–928. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2014.969245

Tschopp, C., Unger, D., and Grote, G. (2016). Are support and social comparison compatible? Individual differences in the multiplexity of career-related social networks. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 46, 7–18. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12338

Van De Voorde, K., and Beijer, S. (2015). The role of employee HR attributions in the relationship between high-performance work systems and employee outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manage. J. 25, 62–78. doi: 10.1111/1748-8583.12062

van der Horst, M., van der Lippe, T., and Kluwer, E. (2014). Aspirations and occupational achievements of Dutch fathers and mothers. Career Dev. Int. 19, 447–468. doi: 10.1108/CDI-12-2012-0128

Van Emmerik, H., Baugh, S. G., and Euwema, M. C. (2005). Who wants to be a mentor? An examination of attitudinal, instrumental, and social motivational components. Career Dev. Int. 10, 310–324. doi: 10.1108/13620430510609145

Van Vianen, A. E. M., Rosenauer, D., Homan, A. C., Horstmeijer, C. A. L., and Voelpel, S. C. (2018). Career mentoring in context: a multi-level study on differentiated career mentoring and career mentoring climate. Hum. Resour. Manage. 57, 583–599. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21879

Vanhala, M., and Ritala, P. (2016). HRM practices, impersonal trust and organizational innovativeness. J. Managerial Psychol. 31, 95–109. doi: 10.1108/JMP-03-2013-0084

Wegman, L. A., Hoffman, B. J., Carter, N. T., Twenge, J. M., and Guenole, N. (2018). Placing job characteristics in context: cross-temporal meta-analysis of changes in job characteristics since 1975. J. Manage. 44, 352–386. doi: 10.1177/0149206316654545

Whitener, E. (2001). Do “high commitment” human resource practices affect employee commitment? A cross-level analysis using hierarchical linear modelling. J. Manage. 27, 515–535.

Williams, J., and MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Resampling and distribution of the product methods for testing indirect effects in complex models. Struct. Equat. Model. 15, 23–51. doi: 10.1080/10705510701758166

Wolff, H. G., and Moser, K. (2009). Effects of networking on career success: a longitudinal study. J. Appl. Psychol. 94, 196–206. doi: 10.1037/a0013350

Wolff, H. G., and Moser, K. (2010). Do specific types of networking predict specific mobility outcomes? A two-year prospective study. J. Vocat. Behav. 77, 238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.03.001

Wood, S., van Veldhoven, M., Croon, M., and De Menezes, L. (2012). Enriched job design, high involvement management and organizational performance: the mediating roles of job satisfaction and well-being. Hum. Relat. 65, 419–445. doi: 10.1177/0018726711432476

Wright, P. M., McMahan, G. C., and McWilliams, A. (1994). Human resources and sustained competitive advantage: a resource-based perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 5, 301–326. doi: 10.1080/09585199400000020

Wu, C. H., Parker, S. K., and De Jong, J. P. J. (2014). Need for cognition as an antecedent of individual behavior. J. Manage. 40, 1511–1534. doi: 10.1177/0149206311429862

Keywords: career aspirations, organizational core competencies, taking charge, proactive behavior, networking

Citation: Baroudi SE, Khapova SN, Fleisher C and Jansen PGW (2018) How Do Career Aspirations Benefit Organizations? The Mediating Roles of the Proactive and Relational Aspects of Contemporary Work. Front. Psychol. 9:2150. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02150

Received: 13 July 2018; Accepted: 19 October 2018;

Published: 09 November 2018.

Edited by:

Roberta Fida, University of East Anglia, United KingdomReviewed by:

Robert Jason Emmerling, ESADE Business School, SpainGary Pheiffer, University of Hertfordshire, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2018 Baroudi, Khapova, Fleisher and Jansen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sabrine El Baroudi, cy5lbGJhcm91ZGlAdnUubmw=

Sabrine El Baroudi

Sabrine El Baroudi Svetlana N. Khapova

Svetlana N. Khapova Chen Fleisher

Chen Fleisher Paul G. W. Jansen

Paul G. W. Jansen