- 1African American Studies, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana

- 3Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ, United States

- 4Department of Psychology, Fayetteville State University, Fayetteville, NC, United States

- 5Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana

- 6Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Proverbs are widely used by the Akan of West Africa. The current study thematically analyzed an Akan proverb compendium for proverbs containing emotion references. Of the identified proverbs, a focus on negative emotions was most typical. Emotion-focused proverbs highlighted four emotion regulation strategies: change in cognition, response modulation, situation modification, and situation selection. A subset of proverbs addressed emotion display rules restricting the expression of emotions such as pride, and emotional contagion associated with emotions such as shame. Additional themes including: social context influences on the expression and experience of emotion; expectations of emotion limits; as well as the nature of emotions were present in the proverb collection. In general, Akan emotion-related proverbs stress individual-level responsibility for affect regulation in interpersonal interactions and societal contexts.

Introduction

Humans experience and express emotion in order to react to, interface with, and adapt to the physical and social environment. Emotion regulation — the ability to manage and modify one’s emotional experiences and expressions (Matsumoto, 2006) — is thus important in everyday life. The adaptation and modification of emotion comprises a heterogeneous set of processes involving changes in the experiential, behavioral, and physiological responses associated with an emotion (Gross and John, 2003). These changes are generally either antecedent-focused or response-focused (Gross, 1998a, 2002), meaning emotions can be modified both before and after their initiation (Liverant et al., 2008). Cultural context has been shown to impact emotion at both of these stages (e.g., Davis et al., 2012; Matsumoto and Juang, 2013; Ma et al., 2017). Because cultural rules are not routinely explicit, it is often difficult to access cultural expectations and preferred practices concerning emotion display and regulation by directly asking participants of the culture what the rules are. This may be particularly true of cultural contexts such as Ghana, where in contrast to many North American settings, the preferred communication style is high context (Hall, 1992); indirectness and symbolism rather than explicit communication is common (Copeland and Griggs, 1986; Yankah, 1995); emotion is considered less important to attend to in everyday life (Dzokoto, 2010); and emotion discourse in the description of emotionally significant positive and negative life events is less elaborate (in terms of total number of emotion words used) (Dzokoto et al., 2013). In such settings, a better approach may be to target the symbolism through which the cultural rules are communicated. The goal of the present study is to identify – through qualitative analysis- cultural rules about emotion regulation in Ghana using a widely used (in Ghana), symbolic cultural artifact that is an important component of everyday discourse, socialization, and intergenerational value transmission (Brookman-Amissah, 1986); the proverb.

Emotion Regulation: Strategies and Cultural Variation

Gross (1998b) identified several emotion regulation strategies: situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognition change (antecedent-focused emotion regulation strategies) and response modulation (response-focused emotion regulation strategy). These strategies have been observed in Western as well as non-western cultures. The regulation strategy of situation selection refers to the decision to either approach or avoid certain people, places, or objects in order to regulate emotions. Situation modification is an active effort to change the situation whereas attentional deployment involves devoting efforts to a specific aspect of an emotion situation by distracting, concentrating, or ruminating on it. Cognitive change aims at modifying the emotion response by changing the cognitive evaluation using defenses such as denial, isolation, intellectualization, or use of techniques such as cognitive reframing and reappraisal. According to Gross and John (2003), cognitive reappraisals comprise the interpretation of a potential emotion-eliciting situation in a way that changes its emotional impact. Finally, response modulation entails direct attempts at changing physiological, experiential, or behavioral responses; using techniques like exercise, biofeedback, relaxation, food, and drugs once an emotion has been elicited (Gross, 1998b,c). It may also present as emotional/expressive suppression (Gross and John, 2003), faking, or the amplification of an emotional response (Grandey, 2000; Liverant et al., 2008).

A growing body of research demonstrates that aspects of emotion regulation occur along cultural patterns. Individuals in collectivistic cultures, where social harmony and self-restraint are emphasized, are more likely to regulate their emotion using positive attributions in anger-inducing interpersonal situations (Trommsdorff, 2012). In contrast, individuals in individualistic cultures utilize negative attributions, which activate goals for retaliation and maintenance of self-esteem. Specific cognitive change strategies, for example distancing and thinking about the victim have been found to have a strong association with culture, gender and emotional intensity (Davis et al., 2012). Due to cultural differences in the valuing and meaning of positive and negative emotions, Asians tend not to savor positive emotions, and are less likely to down-regulate negative emotion while European Americans prefer not to dampen positive emotions and are more likely to regulate emotion hedonically in experimental and experiential settings (Miyamoto and Ma, 2011; Miyamoto et al., 2014). Wan and Savina (2015) compared preferred emotion regulation strategies in US and Hong Kong Chinese public school children. They observed that US children endorsed positive distraction and talking to someone to a greater extent than the comparison group, while Chinese (but not US) children endorsed deep breathing as a fear regulation strategy. For both groups, situational avoidance and talking to someone were endorsed for the downregulation of anger. More recently, Ma et al. (2017) observed that culture (Asians from 5 countries and Asian Americans versus EuroAmerican) and situational demands (such as required cognitive effort) interact to shape positive emotion regulation. Nam et al. (2018) noted that whereas for American subjects, the high use of emotion suppression was detrimental to evaluations of life satisfaction, low use of emotion suppression was beneficial to evaluations of life satisfaction for Hong Kong Chinese research participants. In a study of 6 European countries, Potthoff et al. (2016) observed that participants from northern Europe used cognitive emotion regulation strategies as rumination and catastrophization less than respondents from Southern and Eastern Europe. Collectively, work in this area notes cultural and racial differences in mean levels of some emotion regulation strategies, and is beginning to explore association between emotion regulation and psychological adjustment in different cultural settings (Cheung and Park, 2010).

Majority of the studies exploring the interplay of culture and emotion regulation have focused on East–West differences. In contrast, emotion regulation norms and preferences in African settings have been largely understudied. As such, while identified emotion regulation strategies appear to be relevant to markedly different cultural contexts, there is limited information about which ones are promoted and valued in varied African settings. Of the relatively few studies in this area that included African countries, there are some suggestions that African settings may promote unique emotion regulation strategies and patterns. Bozicevic et al. (2016) found cultural differences in emotion regulation between samples of United Kingdom, White South African, and Black South African children, and in maternal responses to infant distress. In contrast, Kliewer et al. (2017) found that similar to research done elsewhere in the world, poverty was significantly associated with emotion dysregulation in South African youth.

Emotion Display Rules

Some elements of emotion regulation and associated variation across cultures have been explored through the lens of cultural display rules. Emotion display rules (socialized, culturally determined rules concerning the propriety of specific emotion expression at specific times, places, and interpersonal settings) train people to automatically modify (dampen, intensify, neutralize, qualify, mask, and fabricate) elicited emotional reactions according to context-specific demand characteristics (Matsumoto and Juang, 2013). These rules, guided in part by cultural values related to inherent social structures and interpersonal relationships, are important for the preservation of social order; the generation of culturally appropriate behavior and emotional responding; and the facilitation of social functioning (Matsumoto and Juang, 2013).

Recent studies have found some cultural differences in emotion displays and display rules. For instance, Elfenbein et al. (2007) posited the existence of expressive display cultural variation patterns similar to those documented in linguistic dialects. While posed expressions of fear, embarrassment, and disgust were similar in Quebecois and Gabonese research participants, different patterns of muscle activations for the two groups were observed for emotions such as serenity, shame, and contempt. Using the GRID instrument to assess components of emotional meaning, Hess et al. (2013) attribute the aforementioned variation to differences in modal appraisal patterns. Also, Thibault et al. (2012) found that while Quebecois perceive the Duchenne marker as an indicator of an authentic smile, Gabonese do not, and Mainland Chinese immigrants use it only when evaluating smiles of Quebecois.

In work that directly explored social expectations of emotion display, Safdar et al. (2009) found cross-national differences in emotional display rules in a 3-country study (Japan, United States, Canada). In their study, Japanese participants thought they should limit the expression of powerful emotions such as anger, as well as positive emotions such as happiness less than North Americans. Additionally, Japanese participants used interaction partner-dependent display rules when expressing powerful emotions while the other groups did not. Matsumoto et al. (2008) used an adapted version of the Display Rule Assessment Inventory to assess expectations about emotion displays for anger, contempt, fear, disgust, happiness, sadness, and surprise in 32 countries. While they observed large universal effects of emotion display norms especially for negative emotions, they also found that individualism was associated with expression norms for happiness and surprise. Subsequently, from a 33 country study which included 2 African countries (Nigeria and Zimbabwe), Matsumoto et al. (2009) concluded that emotional expression differentiation is an important mechanism through which individuals may learn to behave differently in different contexts. Chung (2012) observed that American research participants were more likely than Japanese participants to endorse expressions of anger, contempt, disgust, fear, happiness, and surprise. However, this difference was partially mediated by United States–Japan differences in self-deceptive enhancement. More recently, Tsai et al. (2016) observed that ideal affect differences (degree of preference for high arousal positive emotion states) between the United States and China were reflected in variations in (i) official photo smiles of top-ranked leaders (politicians, CEOs and university presidents); (ii) smiles of winning and losing political candidates; and (iii) CEOs and university presidents of varying ranks from the two countries. The researchers found similar parallels between ideal affect ratings of college students from 10 Western and Eastern countries and emotional expressions displayed by legislators from each of the 10 countries in their official photographs. Culture-specific emotion communication patterns along several of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions have even been observed in studies of affective communication via social media (Furner and George, 2012; Park et al., 2014). Collectively, the emotion display rule literature indicates the existence of display rule universals, as well as patterns of expectations concerning emotional expression nuanced by culture. Because African countries have only recently began to be featured in this focus of research, there is much to learn about emotion display rules and associated nuances in its diverse geographical settings and ethnolinguistic groups.

Proverbs as Cultural Product

Psychological experiences can be examined using a variety of modes of enquiry that have been developed, refined, and tested over time. Unfortunately, some of them are not easily deployable or efficient to use in under-researched settings which often have structural and technological access and affordability barriers that hamper mainstream psychology data collection strategies. A potential way of including such populations in psychological discourse, and thus increasing the global footprint of mainstream and cultural psychological inquiry, is harnessing extant and easily accessible assets of such societies that can provide psychological information. A few researchers have demonstrated that cultural products are useful in explaining human behavior within a cultural context (Morling and Lamoreaux, 2008; DeWall et al., 2011). The body of cultural products—which include proverbs, myths, poems, crafts, visual art, songs, folktales, books, magazines, and advertisements—are thought to contain valuable cultural information that symbolizes the uniqueness of a specific society and “carry the footprints of the social context in which they were created” thereby offering “clues to the long-term cultural dynamics in play” (Kesebir and Kesebir, 2017, p. 259). In other words, cultural products represent cultural affordances (Salter and Adams, 2016). Thus, cultural product (artifact) analysis allows for an exploration of the dynamic interplay between community-relevant events and of psychological phenomena and between facts and incidents across different historical periods (Curşeu and Pop-Curşeu, 2011). Cultural artifact analysis can offer an understanding of (i) cross cultural, within-cultural, and within-person differences (DeWall et al., 2011) and (ii) the nature of the mutual shaping of people and the cultural contexts in which they live (Salter and Adams, 2016).

A ‘proverb’ is a fundamental part of language and culture (Raymond, 1956). It has been variously defined as an epigrammatic philosophical saying that conveys a lesson (Yankah, 2000); and as ‘a rich source of imagery and succinct expression; encapsulating abstract ideas and allusive wording usually in metaphorical form’ (Agbájé, 2002). Proverbs are generally regarded as repositories of folk wisdom (White, 1987). The study of proverbs (Paremiology) dates back to Aristotle (Dabaghi et al., 2010). Used worldwide, proverbs feature prominently in everyday discourse in many African settings. In particular, many African societies conserve and pass on beliefs, heritage, values, norms and other important information from generation to generation using proverbs (Brookman-Amissah, 1986; Lawal et al., 1997; Hussein, 2005). The societal impact of proverbs both in bygone and contemporary eras features prominently in the work of a plethora of Africanist scholars (Brookman-Amissah, 1986; Gyekye, 1995, 1996; Yankah, 2000; Odebunmi, 2008; Aguoru, 2012; Boyejo, 2011, Unpublished; Arinola, 2012), a review of which is beyond the scope of this paper. The proverb is a cultural artifact that has not been widely used in psychological research.

The connection between cultural artifacts and cultural norms has been noted by a growing body of research in Psychology [see reviews by Morling and Lamoreaux (2008) and Lamoreaux and Morling (2012) and research by An (2007), Tsai et al. (2007), and Salter and Adams (2016)]. The aforementioned and similar studies indicate that we can learn things about a culture by looking for patterns in its visual cultural products (e.g., newspaper and internet ads, children’s book illustrations, Black History Month displays). While the cited studies used comparative methods to tap cultural nuances, within-culture analysis can also yield psychologically useful information. Alimi (2012) noted how Chinua Achebe (An African proverbialist and renowned literary author) used proverbs as literary devices in his novels ‘Things Fall Apart’ and ‘Arrow of God’ to describe his characters’ appearances, actions, habits, inner feelings and thoughts. Proverbs have also been used to examine aspects of Chinese mental life (Zhong, 2008); the relationship between changes in song lyrics and cultural changes in psychological processes (DeWall et al., 2011); personality referrents in Romanian epitaphs (Curşeu and Pop-Curşeu, 2011), the psycho-cultural value of proverbial sayings in the work of Chinua Achebe (Aguoru, 2012).

Cultural affordances that make societies unique include factors such as motivations (Markus and Kitayama, 2010) and norms (Eid and Diener, 2001; Marcus and Sabuncu, 2016) that shape the elicitation (Vandello et al., 2008), communication (Crowe et al., 2012), lexica (Dzokoto and Okazaki, 2006), experience (Kitayama et al., 2006), psychological emphasis (Ryder et al., 2008), expression control (Matsumoto et al., 2008), and regulation (Ma et al., 2017) of emotion. It is therefore reasonable to assume that some of this cultural scripting of emotions will be reflected in a culture’s proverbs. Shi-xu (2009) advocates for researchers interested in understanding culture’s influence on emotions to strive to ‘identify the most pertinent, influential and enduring historical elements from cultural moral instructive discourse’ (p. 366). Proverbs fit that bill. Proverbs reflect the values of a society (Yankah, 2000). Research on emotion display rules and emotion regulation reviewed above has shown that values of a society drive emotion display rules (Matsumoto and Juang, 2013; Tsai et al., 2016). Thus, by extension, proverbs may be a cultural product from which to glean information about emotion display rules and emotion regulation practices.

A few studies have explored affect in proverbs. Kurt (1991) examined emotion referencing in cognitive metaphors underlying Judeo-Spanish and Turkish proverbs. Norrick (1994) identified various elements that were representations of expressed emotions in American proverbs, such as exaggeration, images, metaphors, the use of stern warning and impolite vocabulary. Lim (2010) found that emotions tended to be encoded in Malay proverbs as evidenced by various markers of affect. Interestingly, no study has as yet explored emotion in African contexts- contexts in which proverbs are so widely used that they are described as ‘the palm oil with which words are eaten’ (Achebe, 1958).

Exactly how useful are proverbs – age-old nuggets of folk wisdom some of which may have been coined in historic periods preceding modern inventions - in today’s Africa? Are they about as useful today as floppy disks? Hardly. African proverbs provide a window into dominant African worldviews, philosophies, and morality (Mbiti, 1969; Gyekye, 1987). More specifically, proverbs serve as mechanisms for conflict resolution (Kwakye-Nuako et al., 2017), reminders about the social hierarchy and social comportment expectations (Dzahene- Quarshie and Kambon, 2017). They constitute social commentaries on constructions of masculinity (Amfo and Diabah, 2017) and gender (Ahiakpor et al., 2017). Cultural change has occurred over the centuries as a result of influences such as western style education, globalization, rural-urban migration, and the introduction of christianity. Yet, many central values (e.g., kinship systems and ties, importance of spirituality, honoring elders, expectations in romantic relationships) persist (Gyekye, 1996; Goodwin et al., 2012; Darkwah, 2016). Motherhood, for instance, is still very highly valued even though Ghanaian demographic trends indicate societal changes in the context of childbearing. [Between 1998 and 2003 the median age of marriage in Ghana increased; reported age at first intercourse increased by 2 years; the fertility rate decreased from 6.4 to 4.4; Christians were more likely to have less than 3 children per family on average; and the age of first pregnancy increased (Agyei-Mensah, 2005; Heaton and Darkwah, 2011)]. As such, while specific elements may have changed, many underlying elements of what is considered to be good for an individual and Akan society have persisted over time. As such, messages contained in proverbs cannot be presumed obsolete.

Proverbs have an active presence in the contemporary Akan world. In everyday discourse, Akan proverbs serve as a socially acceptable means to be impolite (Anderson, 2017). In traditional settings, proverbs are still one of the verbal strategies used to communicate with chiefs as Yankah described in 1995. They are also featured in literary works of Ghanaian writers (e.g., Aidoo, 1993). Modern developments have expanded the ways in which proverbs are used and circulated. For instance, Akan proverbs are routinely used on Akan radio and television programs (Wiafe-Akenten et al., 2017); in Akan popular music (Agyekum, 2017); in Ghanaian choral music (Amuah and Wuaku, 2017); and in teaching in academic settings (Osseo-Asare, 2017). Regional proverbs have been featured as a task for contestants in a Ghanaian beauty pageant (Ghanaweb, 2011). For at least a decade, one Akan language radio station has run a weekly, hour-long program aired on Sunday evenings in which two competitors engage in a back-and-forth verbal duel of proverbs before a panel of judges. The rules for the program stipulate that appropriate proverbs must be given in response to the previous proverb by the opponent, no proverb can be repeated, and the proverbs have to exist - as in, no one is allowed to make up a proverb on the spur of the moment. Videos of elders engaging in similar friendly proverb mastery competitions have been posted on YouTube and circulate on WhatsApp. Essien (2015) interestingly advocated for a decrease in the use of proverbs and other literary devices in local language news radio programming because according to him, they distract listeners from the central points of the news stories. In sum, far from being a historical relic, proverbs permeate everyday life within and beyond Akan society.

Objective of the Study

The objective of this study is to explore emotion in the Akan society of Ghana through the lens of proverbs as a cultural product. We posited that an examination of a compendium of Akan proverbs will point toward emotion norms and highlight salient approaches to emotion regulation in the culture. Adams (2005) briefly and indirectly hints at the connection between proverbs and culturally grounded behavior and attitudes in his investigation of enemyship and distrust/fear of social others in West African settings. He notes that belief in the existence of dangerous others in immediate social circles are mirrored by proverbs such as “if an insect bites you, it comes from inside your clothes.” Adams goes on to utilize a variety of quantitative data sources and a cultural comparative approach to demonstrate the difference in the cultural grounding of social relationships between West African and North American cultural settings.

Because of the limited amount of research in the area of proverbs and the African psyche, as well as cultural differences in the prevalence, utility, and functions of proverbs between various African and Western (the de facto control in comparative cultural psychology research) cultural contexts, we utilize a non-comparative, qualitative approach in our research. In contrast to a quantitative approach, we use thematic analysis to identify emotion rules promoted by proverbs. Qualitative approaches to investigative inquiry – such as thematic analysis- are particularly useful in illuminating meaning; understanding how and why aspects of specific contexts matter; and unpacking how things, systems, institutions, and cultures work (Patton, 2015). A recent APA task force recognized the significant contributions that researches employing qualitative methods of inquiry have made to the field of psychology (Levitt et al., 2018). The authors observed that the focus on single, often limited, data set yields rich and contextualized descriptions which are often bound to a context or setting. The non-comparative nature of the findings notwithstanding, qualitative findings have their own merits (including theory or social construct development; hypothesis testing; development of initial understandings of a phenomenon or illuminating current understandings of a social process).

The goal of the present study is not to compare the extent to which proverbs provide emotion discourse across different cultures. Rather, we seek to examine a single cultural context to generate a detailed description of complex ways in which this particular, understudied cultural setting may shape affect. In contrast to a comparative epistemology therefore, we use an exploratory, indigenous, cultural study approach to address our research question: the extent to which and the manner in which Akan proverbs address affect. Indigenous cultural studies operate from the assumption that because psychological processes and associated behavior can only be understood within their originating cultural systems, it is crucial to scrutinize the cultural settings that produce the psychological processes (Matsumoto and Juang, 2013). These processes include emotions, and for Akan culture, the cultural setting includes proverbs. As such, our study analyses the proverbs to understand how culture shapes emotions in the Akan.

Similar approaches are adopted in the humanities, especially sociolinguistics, literature, and African Studies. However, we deviate from cultural study and humanities approaches by focusing on psychological principles associated with these cultural influences. In particular, we draw from contemporary psychology theories about emotion and emotion regulation to guide our enquiry. We explore the cultural foundations which may be relevant for the grounding of emotional experience, expression, responding, and management within a specific cultural milieu.

The importance of our study lies in the research gap it starts to address. On the one hand, linguistic anthropology has examined emotion in language in African settings, but has not generated much psychologically useful information due to a predominant focus on morphology, syntax, and pragmatics. On the other hand, while the field of culture and emotion in general has made large strides in exploring the intersection between culture and emotion at a global level, Africa has been significantly under-represented. The goal of the present study is to provide a foundation upon which future research can be based.

The Akan: People, Language and Values

The Akan constitute Ghana’s largest ethnolinguistic group and 47.5% of Ghana’s 24 million citizens (Ghana Statistical Service, 2012). Akans are mostly located in six of Ghana’s ten administrative regions (Agyekum, 2011). The Akan language is one of the most widely spoken and widely studied Ghanaian languages (Agyekum, 2011). It consists of 12 mutually intelligible dialects. Popularly spoken even among multilingual non-native speakers in Ghana, it is routinely used on local language radio stations in Ghana. The first Akan dictionary was developed by Christaller in 1933. The Bible has also been translated into some Akan dialects. Akan can also be found in Eastern and Central Côte D’Ivoire, Ghana’s francophone neighbor.

What does Akan culture value? Traditionally, Akan societies have been described as stratified; with age being one of the main determinant of social role and status. Older people are to be accorded honor and respect. Akan societies are also patriarchal, with gender being an important factor that influences status (Obeng and Stoeltje, 2002). National values data can be taken as a proxy for Akan values given many similarities in values across Ghana’s various ethnolinguistic groups. Ghana ranks higher on Power Distance, and lower on Individualism, Masculinity, and Long Term Orientation compared to the United States and Japan. Ghana’s mean Uncertainty Avoidance score is higher than the United States and lower than Japan’s (Hofstede Insights, 2018). In the World Values Survey’s Wave 5, Ghana ranked higher on traditional values, and lower on self-expression values, and lower on subjective well-being than many western countries (World Values Survey Database, 2018) While these top-down approaches are useful, bottom-up approaches provide complementary and contextual insight. Gyekye (1996) asserts that Akan culture values religion, communal values, marriage, children, traditional political authority, and wealth-building. Adjaye and Aborampah (2004) found that in Akan communities, extended families persist as important kinship structures despite the increase in single (nuclear) family homes due to urbanization and migratory trends, and that elders still play a pivotal role in the intergenerational transmission of cultural values. Extant literature on Akan values has not adequately explored what Akan culture values as far as emotions are concerned. We approach this research question via a bottom-up approach.

Materials and Methods

Emotion Referent Proverbs Identification and Selection

We analyzed seven thousand and fifteen (7,015) Akan proverbs compiled by Appiah et al. (2007) for emotion referents. This compendium of proverbs, gathered over several decades, is the largest and most comprehensive published work of Ghanaian proverbs to date (the previous largest source (Christaller, 1879) had only half as many). The proverb compendium Bu Me Be, Proverbs of the Akans has the original proverbs in Twi (an Akan language), followed by their English literal translations, and their manifest meanings (interpretations) in English. A bilingual (Twi and English) co-author read through each of the 7015 proverbs and created a database consisting of every:

(i) proverb or associated manifest meaning referencing affect (a specific emotion, or mood);

(ii) proverb or associated manifest meaning referencing affect expression (e.g., crying, smiling, weeping, laughing)

(iii) proverb or its manifest meaning alluding to the absence of affect (e.g., proverbs focusing on bravery and courage dealt with the absence of fear).

Coding and Validation

Two hundred and eighty five proverbs had affect referents. Coding was conducted in multiple stages, each with two independent raters. Step 1 involved inductive coding to identify and categorize the specific emotions (such as sadness, fear, and love). Proverbs were also analyzed for cultural nuances (e.g., cultural descriptions; cultural prescriptions; and social context). Interrater agreement was 86.0%. Step 2 was deductive coding using Gross’s emotion regulation strategies as codes. Overall agreement between the coders was 71.9%. Step 3 comprised deductive coding using the six display rules identified by Matsumoto and Juang (2013) as a guide. Interrater agreement was 93.3%. For each of the coding steps, the task was to determine whether a particular code was present either in the proverb or in its meaning provided in English by the authors of the proverbs. Code generation at each stage of the analysis involved: (1) independent identification of codes by two coders; (2) code validation by the two coders; and (3) resolution of discrepancies through discussion. In Steps 2 and 3, the proverbs were also analyzed for affect management strategies and display rules that had not been identified by Gross and Matsumoto, respectively.

Findings

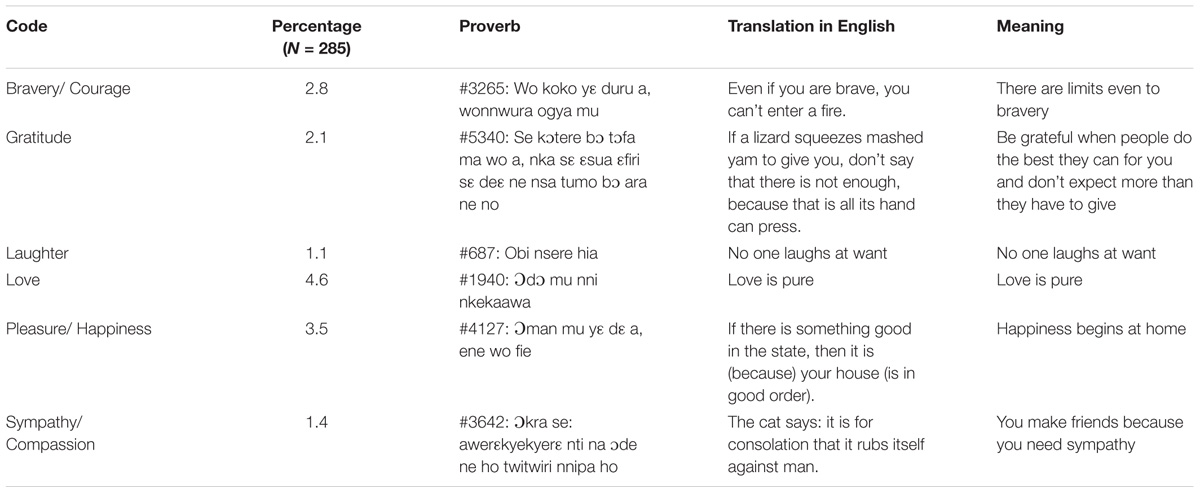

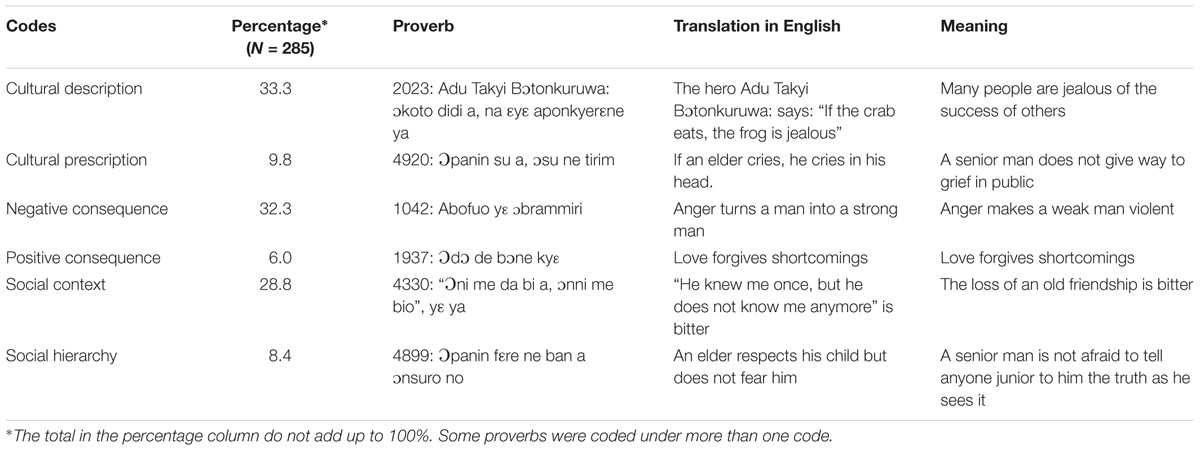

We identified proverbs addressing positive and negative affect and associated behaviors. Negative affect addressed in the Akan proverbs were coded into the following categories: Hurt/Pain/Suffering; Fear; Hatred/Resentment/Contempt; Sorrow/Grief; Anger; Shame/Disgrace; Regret/Disappointment; Dislike; Jealousy/Envy; Worry/Anxiety; Pride1, and Distress. Some of these negative emotions were simultaneously seen as negative and precursors to other negative emotions in proverbs such as “greed brings suffering.” Positive emotions and associated behaviors included Love; Pleasure/Happiness; Bravery/Courage (coded as positive emotions due to their focus on the absence of fear); Sympathy/Compassion; Laughter; and Gratitude. The ratio of negative to positive emotion-focused proverbs was 4.8:1. Category examples are summarized in Tables 1a,b.

The proverbs utilize a variety of formats including declarations (Loneliness is one of the worst forms of suffering); predictions [e.g., If a male cricket gives a fatal blow, some of it gets in his eyes (A warning against fighting or litigation: You will suffer even if you win)]; references to folktales [e.g., Because of shame, Ananse (Father Spider) wears an antelope skin hat to beg for help in weeding his farm (Said of someone who tries to hide what he is like because he wants to get something out of you)]; descriptions (e.g., Anger is like a stranger, it does not stay in only one person’s house); and comparisons [e.g., There are many kinds of weeping: weeping from a game is one thing, weeping from beating is another, weeping from death is yet another, and pretended weeping another (There is a right time for every action)].

Thematically, the proverbs endorse specific regulation strategies, display rules, emotion-specific directives and nuances (cultural prescriptions, cultural descriptions, positive and negative consequences of specific emotions) and the Akan social context (such as emotion norms, social hierarchy, and social interactions). These are discussed below, with our proverb examples provided in italicized English and their manifest meaning in parentheses (except in cases where the literal and manifest meanings are the same).

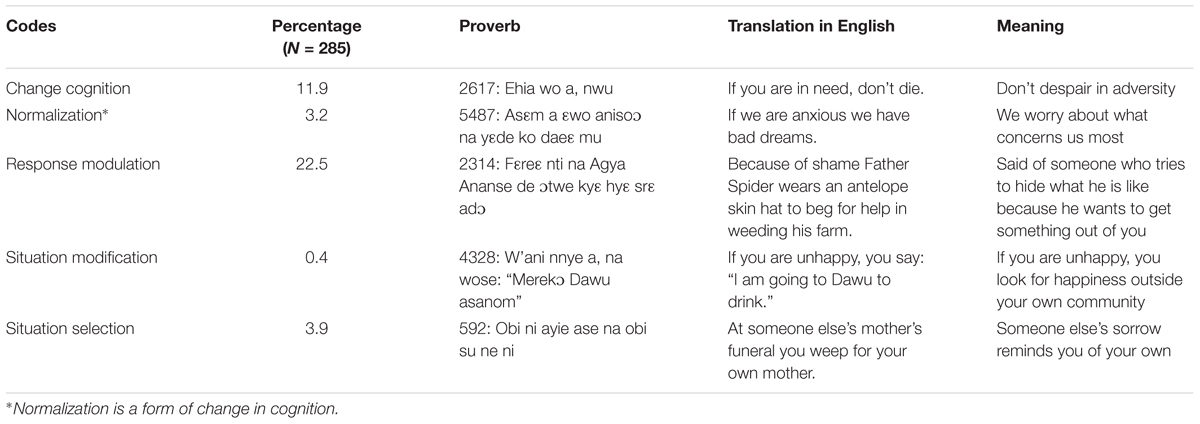

Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation strategies featured prominently in our data (see Table 2). Proverbs such as “We will die, but does that mean we should not sleep?” (There is no point in worrying about the inevitable) reference change in cognition. Some proverbs advocated for response modulation [e.g., “A great man weeps through his pipe” (A great man suffers in silence)]. Proverbs such as “A person full of sores does not go into fellowship with anyone” (If you know you are vulnerable, you avoid those who may hurt you) reference situation selection. “If you are unhappy, you say; I am going to Dawu to drink” (If you are unhappy, you look for happiness outside your own community) reference Situation modification. Also relevant to emotion regulation, some proverbs focus on negative consequences of emotion [e.g., “If one person alone eats the honey, it awakens his stomach (he gets diarrhea)” (Greed brings suffering)]; while others focus on positive consequences [“Remember your creator in the days of your youth, before the bad times come” (Always be grateful to your benefactor and he will continue to help you)].

Proverbs contained messages that normalized particular emotion experiences. Such proverbs refer to cultural narratives about life including the normality of suffering [The deserted town’s small stones say: “it is because of death that we have been scattered” (People suffer from circumstances beyond their control)]; the naturalness of experiencing anxiety in particular contexts [e.g., If we are anxious we have bad dreams. (We worry about what concerns us most)]; the typicality of emotions and/or consequences associated with specific social interactions [If you feel for the young duiker, you eat your soup without meat (If you are too sympathetic, you suffer for it)]; and the futility of agonizing [We will die, but does that mean we should not sleep? (There is no point in worrying about the inevitable)]. Such normalizations have the potential to allow the listener to reappraise emotion-eliciting situations. Proverbs thus furnish a cultural script for coping with negative situations by providing connections between individual situations and experiences of non-specific others within the same cultural context. In a few cases, the proverbs come across as rather brusque [e.g., In normal times, they say that the forest devil is a witch, then how much more so when he is found sitting on the odum tree that bears the fruit of dwarfs? (If you fear something in normal times, how much more so in times of trouble)], potentially serving the additional function as a culturally sanctioned tool that can be used to be impolite (see Anderson, 2017).

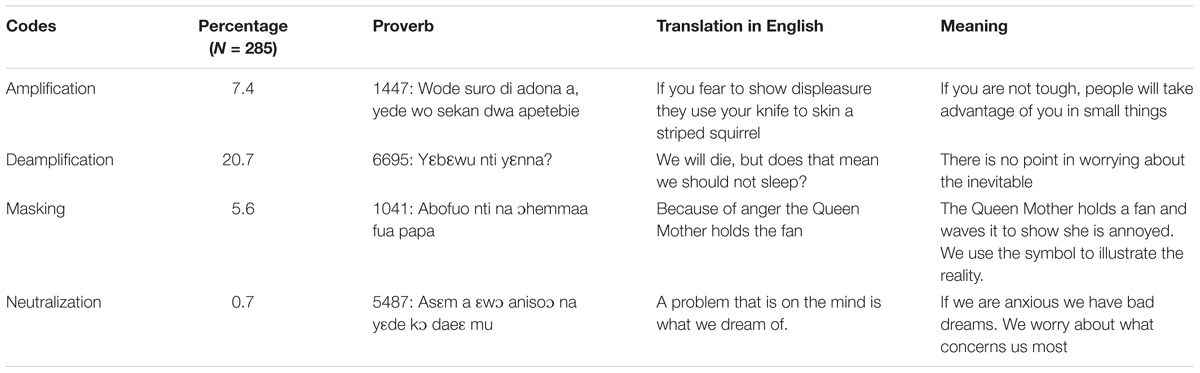

Emotion Display Rules

While no proverbs touch upon specific emotion display markers, some proverbs address preferred action tendencies with respect to particular emotions and social contexts (see Table 3). Shame, a proverb declares “is not a Northern smock that we sew and wear” (We do not advertise our shame). Should an elder need to cry, another proverb dictates that “he cries in his head” (A senior man does not give way to grief in public). We surmise that the cultural expectation that particular emotions should be expressed privately is linked to the loss of status and respect in the eyes of others. This makes sense given that Ghana scores relatively high on Power Distance. In hierarchical contexts, the loss of status is particularly salient, since it disrupts the social order.

Proverbs communicating specific emotion display rules were complemented by others that provide an explicit commentary on undesirable emotions: pride and shame. Proverbs featuring pride communicate that pride – at the level of the individual- is a sign of arrogance and comes before a fall in a variety of ways including :“It is only pride which causes a lizard not to move when you shoot an arrow in it” (Pride may lead to bravado); “Know-all knows nothing”(If you pride yourself on your wisdom, it is a sign of ignorance); and “There is nothing more in pride than getting involved in trouble” (Pride comes before a fall). While many western cultures consider pride to be a positive emotion, this is clearly not the case for the Akan culture. Proverbs such as “Congratulations for giving birth can never end” (People are always pleased at success) do endorse the acknowledgment success. However, the dominant proverb narrative is one in which success should be celebrated, but not evolve into pride. Another emotion noted as undesirable was shame, a message communicated via proverbs including: “Shame and death, death is preferable”; “If a paramount chief who is above destoolment becomes ashamed, he dies through his mouth, i.e., he consumes poison (A great man prefers death to shame); and “Secret criticism hurts more than a wound” (To be hurt physically is less painful than being shamed). Such proverbs communicate expectations that Akans avoid situations that would generate shame, and not display pride.

Akan Emotion Values and Beliefs

The symbolism in the analyzed proverbs includes references to traditional values and practices such as religion, death as a means of contextualization, and the valuing of the group above the individual. Below, we discuss values and beliefs about emotions highlighted by our proverb set that are relevant to emotion regulation and display rules.

Emotion Limits

The collective proverb emotion narrative includes distinctions in limits of emotion. On the one hand, proverbs communicate naturally occurring limits [e.g., “He who weeps cannot weep beyond the cemetery” (Even sorrow has its limits); and “Even when you are brave, you can’t enter a fire” (There are limits even to bravery)], suggesting that some affect types eventually run their course. On the other hand, proverbs – such as “If a man suspects that his wife commits adultery, he should go and suspect the fallen tree across the path to his wife’s farm” (However jealous you are there must be limits to your jealousy) and “Too much benevolence brings suffering to the generous” communicate that some emotions and associated actions should have limits.

Prescriptions (Mandates)

“If God is going to satisfy you, it does not matter if you take a big portion of fufu2 (Be content with what you have).” “Remember the past” we say to those who are ungrateful. (You should always show gratitude for past favors). “Salt should not praise itself saying “I am sweet”” (It is not good to be arrogant nor to praise yourself to others). Proverbs such as these are instructional in nature, communicating expectations about specific affect-related behaviors, see Table 4.

Emotion Descriptions

A subset of proverbs were descriptive in nature, using linguistic tools such as metaphors and similes to communicate philosophies of what emotions are like (e.g., Anger is like a stranger, it does not stay in only one person’s house), and what people experiencing that emotion do [e.g., If a person loves you, (s)he loves you with all your nonsense (You don’t judge those you love, but love everything about them)].

The Akan Socio-Emotional Context

In this section, we address themes observed in the proverbs that relate to the social context. While a few proverbs referenced gender and age (child, adult) these were much less prominent than the themes discussed below.

Socioeconomic Class

A group of proverbs address the intersection between socioeconomic class and affect. These proverbs suggest that socioeconomic class afforded the wealthy particular affect experiences distinguishable from those who were less well off. These included “A poor man’s gunfire passes over a rich man’s ears” (A rich man does not fear a poor man); “Even the ocean that is deep has an excess of salt, how much more the shallow ditch” (If a great man suffers, how much more the poor man); and “If you are in need, one hand lies on the belly of another”3 (The poor cannot afford pride). While the specific connections differ, the local narrative of an affect- socioeconomic class relationship mirrors findings from psychological science. Previous emotion research has demonstrated a link between emotion dysregulation and poverty (Kliewer et al., 2017). Subjective well-being has been linked to income (Diener et al., 2010).

Emotions in Private and Public Spheres

Proverbs address individual-level affect [e.g., “If you are hungry, it is only you who feel it” (You alone have to bear your own suffering)]; individual responsibility for some antecedents [e.g., “If a person is unhappy, it is his own fault” (We are often the cause of our own discontent)], and individual differences [e.g., “If any great animal dies, the vulture puts on white (rejoices)” (One man’s sorrow is another man’s joy)]. The body of proverbs also includes directives to learn from the emotion-related experiences of others [e.g., “Obiri, look at what is happening to Oben” (Take warning from the sufferings of your friends)]; directives to manage the emotions of others [e.g., “We mix hot water with cold water” (If someone is angry you try and cool them down, and do not make it worse)]; and reminders that individual actions can impact others negatively [e.g., “If you have a dog as a member of your family, you are never without tears” (A troublesome relation causes endless worry), and “You should always keep your promises to children or they will be very upset”)]. Impact on others can be deliberate, or accidental as highlighted in “A funeral announcer causes them to kill a witch” (One action unwittingly leads to another person’s suffering). Collectively, these types of proverbs address the intersection between the individual and the social. While emotions are certainly relevant to the individual, they are also relevant to the group that the individual is a member of. As such, the cultural narrative captured by the analyzed proverbs includes responsibility for one’s own emotions, and in some contexts, those of others.

Social Hierarchy

Expectations about maintaining decorum – especially for those of high status – were captured in proverbs focusing on behaviors such as public grief. Proverbs (including some addressed in categories above), mention high status position such as chief, paramount chief, and elder. Others mention servant/slave/employee status [e.g., “A slave taboos the best palm nuts4” (A slave fears to take the best of anything); and “If you keep company with a leopard, you no longer fear anything in the bush” (If you are friends with a powerful man, you don’t need to fear anyone)].

Emotional Contagion

The potency of an individual’s emotions to influence the social world is captured by proverbs highlighting emotional contagion. Proverbs such as “Weeping is contagious” and “Anger is like a stranger, it does not stay in only one person’s house” serve as a reminder that affect can be spread through the community via exposure to someone else’s emotion. One proverb in this category makes the distinction between this quality and other aspects of life that do not transmit across the community in a similar manner thus: “If your mother dies, you don’t die, but if she is shamed, you are also shamed” (Shame is worse than death).

Friendship and Enemyship

In addition to references to various kin, the proverbs highlight other interpersonal relationships relevant to Akan social functioning. Proverbs such as “He knew me once, but he does not know me anymore is bitter” (The loss of an old friendship is bitter); and “The cat says it is for consolation that it rubs itself against man” (“You make friends because you need sympathy”) focus on emotion in the context of friendship. In contrast, proverbs such as “If those who hate you happen to know the inside of your case, if you talk salt, it turns to pepper” (A person who hates you will always do their best to misinterpret you) and “An army fears an army” (You fear your enemies) focus on emotion in the context of enemyship. Taken together, these proverbs portray a social world that consists of supportive and potentially dangerous personal relationships (see Adams, 2005 for a review of enemyship in Ghana).

Social Harmony

Social harmony is relevant to many of the proverbs that addressed the social context. In addition, some proverbs addressed it explicitly e.g., “The brother of want is peacefulness”; “If a male cricket gives a fatal blow, some of it gets in his eyes” (A warning against fighting or litigation: You will suffer even if you win), and “Anger drives something good from the house.”

Discussion

Altogether, emotion-focused proverbs (such as those showcased in our results) construct a philosophy of expectations – albeit incomplete- about how Akans ought to experience and express feeling. In some cases, proverbs articulate expectations about display rules – especially whether emotions should be hidden or expressed in public. In others, they provide cognitive frames relevant to the construction of meaning (e.g., what is normal in the experience of specific emotions; comparisons of emotion to death) from emotion-eliciting events in a variety of social interactions and life experiences (e.g., suffering) which can facilitate cognitive reframing and reappraisal. Proverbs address positive and negative consequences of emotion. They also promote particular, response-focused patterns of emotion regulation (situation selection, response modulation, and situation modification).

Often using symbolism that draws from physical objects and social occurrences in everyday life, the Akan narrative about emotions is woven around culturally salient elements such as interpersonal interactions. Certainly, emotion management is central to many cultural groups including the Akan people, for whom interpersonal associative ties of kinship and other affiliative bodies are central to constructions of identity, and associated behavior and decision-making. While psychological theory makes distinctions between emotion, emotion episodes, and mood, such distinctions are not evident in Akan proverbs. Akan proverbs seem to support an ‘anger-in’ (see Novin et al., 2012) approach, and discourage an ‘anger-out’ strategy. They also promote expression of positive emotions by highlighting personal (e.g., a cheerful person does not arouse resentment), familial (love brings a good manner of living to the home) and societal (what is enjoyable is enjoyed by all) benefits. Relevant to the preservation of social harmony, this trend is consistent with previous research that notes promotion of socially engaging emotion as a feature of interdependent cultural contexts, and a promotion of socially disengaging emotions of a feature of independent contexts (Kitayama et al., 2006). We posit that the discouragement of public expressions of grief and anger are relevant to the maintenance of social hierarchy since they decrease the likelihood of loss of face in high status individuals.

Including a bottom-up approach in our data analysis unearthed emotion-related nuances specific to the Akan proverbial context. Proverbs address dangers of emotional contagion of undesirable emotions such as shame; the expectation that particular emotions have or should have limits; and the intersections between socioeconomic class, social status, and various types of interpersonal relationships with affect. Contrary to our expectations, gender and developmental stages were not prominent in our data. Collectively, the proverbs reflected construction of a social world that involves kinship, friends, and enemies, and an emotion world that involves action, social interaction, and personal effort (in terms of adjusting one’s emotion displays and actions to social expectations). They communicate a concept of emotion that is not simply felt, but performed.

It is striking – but not surprising – that only 4% of Akan proverbs address emotion. The relatively minimal focus on emotion in the larger proverb collection mirrors the minimal explicit focus on emotion in Akan daily life vis-a-vis other concerns. In the United States people are socialized to talk about their feelings, think about their subjective well-being, and identify and seek what makes them happy. Such practices do not occur to the same extent in Akan and other Ghanaian societies. Ghanaian college students scored significantly lower than United States college students on a self-report measure of Emotional Attention, rating emotions as less important to attend to (Dzokoto, 2010). Compared to a college student sample from the United States, Ghanaian college students used fewer emotion words in written descriptions of emotionally significant events (Dzokoto et al., 2013). While emotions are not completely unimportant for the Akan, they are not verbally elaborated or valued in the same manner as the United States. Their relative paucity in the proverb collection is a reflection that other aspects of Akan values and practices are elaborated in greater detail.

Limitations, Conclusion, and Future Research

Understanding cultural narratives about emotion helps document cultural philosophies. These cultural standards of expectation can inform emotion behaviors and emotion regulation strategies which influence behavior and cognition. Also, the fit of individual emotion beliefs and practices with the cultural milieu has implications for physical and mental well-being (see for example Potthoff et al., 2016). Our study demonstrates that Akan proverbs, which serve as a repository of culturally important values and norms, include maxims that favor particular emotional norms and regulatory practices consistent with the preservation of social harmony, prevention of loss of face, and establishment of often value-based standards for the experience and expression of emotion in everyday life. Akan proverbs thus form part of a cultural narrative that dictates how Akans ought to navigate and manage their emotions. A ubiquitous tool in a historically oral culture, proverbs have so far been under-utilized as a research resource in Cultural Psychology.

What our study fails to do, which should be explored in future research, is the actual impact of proverb messages; in other words, the extent to which, and processes through which proverbs’ emotion messages are socialized, and whether they are in fact internalized and demonstrated. For instance, it is unclear whether real time experiences, attitudes, beliefs, and values mirror those addressed in proverbs, or whether Akans perpetually disregard proverb messages, hence needing to be constantly reminded about a culturally utopian state of affairs. Our study also does not quantitatively examine the structure of emotion meaning components [such as appraisals and action tendencies, which can be assessed with tools such as the GRID questionnaire (Fontaine et al., 2013)]. Future research should explore these questions in Akan and other African groups, since – per an Akan proverb- “A matter which troubles the Akan people, the people of Gonja take to play the brεkεtε drum.”

Author Contributions

VAD designed the study and wrote sections of the paper. AO-T was involved in data coding and writing. JK extracted the data and was involved in coding and data interpretation. MT-A revised and edited the manuscript. DAA and DA were involved in data extraction checks and initial drafting of sections of the literature review.

Funding

This project was supported by a Virginia Commonwealth University Humanities Research Center fellowship to the first author.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

- ^See emotion Display Rules section.

- ^A kind of food.

- ^Refers to the cultural hand gesture for pleading.

- ^Used for making local alcohol (palm wine).

References

Adams, G. (2005). The cultural grounding of personal relationship: enemyship in North American and West African worlds. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 88, 948–968. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.948

Adjaye, J. K., and Aborampah, O. (2004). Intergenerational cultural transmission among the Akan of Ghana. J. Intergener. Relationsh. 2, 23–38. doi: 10.1300/J194v02n03_03

Agbájé, J. B. (2002). Proverbs: a strategy for resolving conflict in Yoruba society. J. Afr. Cult. Stud. 15, 237–243. doi: 10.1080/1369681022000042673

Aguoru, D. (2012). African proverbial sayings: a paremiological reading of Achebe’s ‘Arrow of God’. IFE Psychol. 20, 192–204.

Agyei-Mensah, S. (2005). “Fertility transition in Ghana: looking back and looking forward,” in Reproductive Change in Ghana: Recent Patterns and Future Prospects, eds S. Agyei-Mensah, J. B. Casterline, and D. K. Agyeman (Legon: Department of Geography and Resource Development), 1–17.

Agyekum, K. (2011). The ethnopragmatics of the Akan palace language of Ghana. J. Anthropol. Res. 67, 573–593. doi: 10.3998/jar.0521004.0067.404

Agyekum, K. (2017). “Proverbs in Akan music: a case study of Alex Konadu’s lyrics,” in Paper Presented at the Second School of Languages Conference, University of Ghana, Legon.

Ahiakpor, L., Akoto, E., and Mintah, P. (2017). “Social construction of gender with particular reference to Akan proverbs,” in Paper Presented at the Second School of Languages Conference, (University of Ghana, Legon.

Aidoo, A. (1993). Changes: A Love Story. New York, NY: Feminist Press at the City University of New York.

Alimi, S. A. (2012). A study of the use of proverbs as a literary device in Achebe’s ‘Things fall apart’ and ‘Arrow of God’. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2, 121–127.

Amfo, A. N. A., and Diabah, G. (2017). “To dance or not to dance: masculinities in Akan proverbs and their implications for contemporary societies,” in Paper Presented at the Second School of Languages Conference, University of Ghana, Legon.

Amuah, J., and Wuaku, H. (2017). “The use of proverbs as effective textual communication tool in Ghanaian choral music composition,” in Paper Presented at the Second School of Languages Conference, University of Ghana, Legon.

An, D. (2007). Advertising visuals in global brands’ local websites: a six-country comparison. Int. J. Adv. 26, 303–332. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2007.11073016

Anderson, J. (2017). “Politeness mechanism in Akan proverbs,” in Paper Presented at the Second School of Languages Conference, University of Ghana, Legon.

Appiah, P., Appiah, A., and Agyeman-Duah, I. (2007). Bu Me Be: Proverbs of the Akans, 2nd Edn. Oxfordshire: Ayebia Clarke Publishing.

Arinola, A. C. (2012). The decline of proverbs as a creative oral expression: a case study of proverb usage among the Ondo in the South Western part of Nigeria. Afrrev Laligens 1, 127–148.

Bozicevic, L., De Pascalis, L., Schuitmaker, N., Tomlinson, M., Cooper, P., and Murray, L. (2016). Longitudinal association between child emotion regulation and aggression, and the role of parenting: a comparison of three cultures. Psychopathology 49, 228–235. doi: 10.1159/000447747

Cheung, R., and Park, I. (2010). Anger suppression, interdependent self-construal, and depression among Asian american and european american college students. Cult. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 16, 517–525. doi: 10.1037/a0020655

Christaller, J. G. (1879). Twi Mmebusem: Mpensà-Ahansia Mmoaano. A Collection of 3600 Twi Proverbs, Basel. Basel: Evangelische Missionsgesellschaft.

Chung, J. (2012). The contribution of self-deceptive enhancement to display rules in the United States and Japan. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 15, 69–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-839x.2011.01358.x

Crowe, M., Raval, V. V., Trivedi, S. S., Daga, S. S., and Raval, P. H. (2012). Processes of emotion communication and control. Soc. Psychol. 43, 205–214. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000121

Curşeu, P. L., and Pop-Curşeu, I. (2011). Alive after death: an exploratory cultural artifact analysis of the merry cemetery of Săpânţa. J. Commun. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 21, 371–387. doi: 10.1002/casp.1080

Dabaghi, A., Pishbin, E., and Niknasab, L. (2010). Proverbs from the viewpoint of translation. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 1, 807–814.

Darkwah, A. K. (2016). “Globalisation, development and the empowerment of women,” in Handbook of Gender in International Relations, eds J. Steans and D. Tepe (London: Edward Elgar), 386–393.

Davis, E., Greenberger, E., Charles, S., Chen, C., Zhao, L., and Dong, Q. (2012). Emotion experience and regulation in China and the United States: how do culture and gender shape emotion responding? Int. J. Psychol. 47, 230–239. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2011.626043

DeWall, C. N., Pond, R. S., Campbell, W. K., and Twenge, J. M. (2011). Tuning in to psychological change: linguistic markers of psychological traits and emotions over time in popular US song lyrics. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 5, 200–207. doi: 10.1037/a0023195

Diener, E., Ng, W., Harter, J., and Arora, R. (2010). Wealth and happiness across the world: material prosperity predicts life evaluation, whereas psychosocial prosperity predicts positive feeling. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 99, 52–61. doi: 10.1037/a0018066

Dzahene- Quarshie, J., and Kambon, O. (2017). “Ɔpɔ ne nteteε pa ho hia wɔ Akan ne Kiswahili mmε mu,” in Paper Presented at the Second School of Languages Conference,University of Ghana, Legon.

Dzokoto, V. (2010). Different ways of feeling: emotion and somatic awareness in Ghanaians and euro-americans. J. Soc. Evol. Cult. Psychol. 4, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/h0099299

Dzokoto, V., Opare-Henaku, A., and Kpobi, L. (2013). Somatic referencing and psychologisation in emotion narratives: a USA–Ghana comparison. Psychol. Dev. Soc. 25, 311–331. doi: 10.1177/0971333613500875

Dzokoto, V. A., and Okazaki, S. (2006). Happiness in the eye and the heart: somatic referencing in West African emotion lexica. J. Black Psychol. 32, 117–140. doi: 10.1177/0095798406286799

Eid, M., and Diener, E. (2001). Norms for experiencing emotions in different cultures: inter-and intranational differences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81, 869–885. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.869

Elfenbein, H., Beaupré, M., Lévesque, M., and Hess, U. (2007). Toward a dialect theory: cultural differences in the expression and recognition of posed facial expressions. Emotion 7, 131–146. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.131

Essien, P. (2015). Radio Broadcast in Akan. Available at: https://www.graphic.com.gh/features/opinion/radio-broadcast-in-akan-by-peter-essien.html

Fontaine, J., Scherer, K., and Soriano, C. (2013). Components of Emotional Meaning. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199592746.001.0001

Furner, C., and George, J. (2012). Cultural determinants of media choice for deception. Comput. Hum. Behav. 28, 1427–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.03.005

Ghana Statistical Service (2012). 2010 Population and Housing Census: Summary Report of Final Results. Accra: Sankofa Press Limited.

Ghanaweb (2011). Ghana’s Most Beautiful Contestants Speak In proverbs. Available at: https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/artikel.php?ID=218682

Goodwin, R., Marshall, T., Fülöp, M., Adonu, J., Spiewak, S., Neto, F., et al. (2012). Mate value and self-esteem: evidence from eight cultural groups. PLoS One 7:e36106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036106

Grandey, A. (2000). Emotion regulation in the workplace: a new way to conceptualize emotional labor. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 5, 95–110. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95

Gross, J. J. (1998a). Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 224–237.

Gross, J. J. (1998b). Emotion regulation: past, present, and future. Cogn. Emot. 13, 551–573. doi: 10.1080/026999399379186

Gross, J. J. (1998c). The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2, 271–299. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology 39, 281–291. doi: 10.1017/S0048577201393198

Gross, J. J., and John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85, 348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Gyekye, K. (1987). An Essay on African Philosophical Thought: The Akan Conceptual Scheme. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gyekye, K. (1995). An Essay on African Philosophical Thought: The Akan Conceptual Scheme. Revised Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Heaton, T., and Darkwah, A. K. (2011). Religious differences in modernization of the family: family demographic trends in Ghana. J. Fam. Issues 20, 1–21. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11398951

Hess, U., Thibault, P., and Levesque, M. (2013). “Where do emotional dialects come from? A comparison of the understanding of emotion terms between Gabon and Quebec,” in Components of Emotional Meaning: A sourcebook, eds J. Fontaine, K. Scherer, and C. Soriano (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 512–521.

Hofstede Insights (2018). Compare Countries - Hofstede Insights. Available at: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/product/compare-countries/ [accessed April 1, 2018].

Hussein, J. W. (2005). The social and ethno-cultural construction of masculinity and femininity in African proverbs. Afr. Study Monogr. 26, 59–87.

Kesebir, S., and Kesebir, P. (2017). A growing disconnection from nature is evident in cultural products. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 12, 258–269. doi: 10.1177/1745691616662473

Kitayama, S., Mesquita, B., and Karasawa, M. (2006). Cultural affordances and emotional experience: socially engaging and disengaging emotions in Japan and the United States. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91, 890–903. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.890

Kliewer, W., Pillay, B., Swain, K., Rawatlal, N., Borre, A., Naidu, T., et al. (2017). Cumulative risk, emotion dysregulation, and adjustment in South African Youth. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26, 1768–1779. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0708-6

Kwakye-Nuako, C., Osei-Tutu, A., and Dzokoto, V. (2017). ““Obi nka obi”: proverbs and conflict resolution among the Akans of Ghana,” in Paper Presented at the Second School of Languages Conference, University of Ghana, Legon.

Lamoreaux, M., and Morling, B. (2012). Outside the head and outside individualism-collectivism: further meta-analyses of cultural products. J. CrossCult. Psychol. 43, 299–327. doi: 10.1177/1088868308318260

Lawal, A., Ajayi, B., and Raji, W. (1997). A pragmatic study of selected pairs of Yoruba proverbs. J. Pragmat. 27, 635–652. doi: 10.1016/S0378-2166(96)00056-2

Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., and Suarez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: the APA publications and communications board task force report. Am. Psychol. 73, 26–46. doi: 10.1037/amp0000151

Lim, K. H. (2010). How Malay proverbs encode and evaluate emotion? A paremiological analysis. Sari Int. J. Malay World Civilis. 28, 57–81.

Liverant, G. I., Brown, T. A., Barlow, D. H., and Roemer, L. (2008). Emotion regulation in unipolar depression: the effects of acceptance and suppression of subjective emotional experience on the intensity and duration of sadness and negative affect. Behav. Res. Ther. 46, 1201–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.08.001

Ma, X., Tamir, M., and Miyamoto, Y. (2017). A socio-cultural instrumental approach to emotion regulation: culture and the regulation of positive emotions. Emotion 18, 138–152. doi: 10.1037/emo0000315

Marcus, J., and Sabuncu, N. (2016). “Old oxen cannot plow”: stereotype themes of older adults in Turkish folklore. Gerontologist 56, 1007–1022. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv108

Markus, H. R., and Kitayama, S. (2010). Culture and self: a cycle of mutual constitution. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 5, 420–430. doi: 10.1177/1745691610375557

Matsumoto, D. (2006). Are cultural differences in emotion regulation mediated by personality traits? J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 37, 421–437. doi: 10.1177/0022022106288478

Matsumoto, D., and Juang, L. (2013). Culture and Psychology, 5th Edn. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S., and Fontaine, J. (2009). Hypocrisy or maturity? Culture and context differentiation. Eur. J. Pers. 23, 251–264. doi: 10.1002/per.716

Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., and Fontaine, J. (2008). Mapping expressive differences around the world. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 39, 55–74. doi: 10.1177/0022022107311854

Miyamoto, Y., and Ma, X. (2011). Dampening or savoring positive emotions: a dialectical cultural script guides emotion regulation. Emotion 11, 1346–1357. doi: 10.1037/a0025135

Miyamoto, Y., Ma, X., and Petermann, A. G. (2014). Cultural differences in hedonic emotion regulation after a negative event. Emotion 14, 804–815. doi: 10.1037/a0036257

Morling, B., and Lamoreaux, M. (2008). Measuring culture outside the head: a meta-analysis of individualism—collectivism in cultural products. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 12, 199–221. doi: 10.1177/1088868308318260

Nam, Y., Kim, Y., and Tam, K. K. (2018). Effects of emotion suppression on life satisfaction in americans and chinese. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 49, 149–160. doi: 10.1177/0022022117736525

Norrick, N. R. (1994). Proverbial emotions: how proverbs encode and evaluate emotion. Proverbium 11, 207–215.

Novin, S., Banerjee, R., and Rieffe, C. (2012). Bicultural adolescents’ anger regulation: in between two cultures? Cogn. Emot. 26, 577–586. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.592084

Obeng, S., and Stoeltje, B. J. (2002). Women’s voices in Akan juridical discourse. Afr. Today 49, 21–41. doi: 10.1353/at.2002.0008

Odebunmi, A. (2008). Pragmatik functions of crisis – motivated proverbs in Ola Rotimi’s ‘The gods are not to blame’. Linguist. Online 33, 73–84. doi: 10.13092/10.33.530

Osseo-Asare, K. (2017). “Ogya ne atuduro nnaf Faako - fire and gunpowder do not sleep together: teaching and learning materials science and engineering with African proverbs,” in Paper Presented at the Second School of Languages Conference, University of Ghana, Legon.

Park, J., Baek, Y., and Cha, M. (2014). Cross-cultural comparison of nonverbal cues in emoticons on twitter: evidence from big data analysis. J. Commun. 64, 333–354. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12086

Patton, M. (2015). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Potthoff, S., Garnefski, N., Miklósi, M., Ubbiali, A., Domínguez-Sánchez, F., Martins, E., et al. (2016). Cognitive emotion regulation and psychopathology across cultures: a comparison between six European countries. Pers. Individ. Differ. 98, 218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.022

Raymond, J. (1956). Tensions in proverbs: more light on international understanding. West. Folk. 15, 153–158. doi: 10.2307/1497308

Ryder, A. G., Yang, J., Zhu, X., Yao, S., Yi, J., Heine, S. J., et al. (2008). The cultural shaping of depression: somatic symptoms in China, psychological symptoms in North America? J. Abnorm. Psychol. 117, 300. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.300

Safdar, S., Friedlmeier, W., Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S., Kwantes, C., Kakai, H., et al. (2009). Variations of emotional display rules within and across cultures: a comparison between Canada, USA, and Japan. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 41, 1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0014387

Salter, P. S., and Adams, G. (2016). On the Intentionality of cultural products: representations of black history as psychological affordances. Front. Psychol. 7:1166. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01166

Shi-xu, (2009). Continuing commentary: emotions of guilt and shame: towards historical and intercultural perspectives on cultural psychology. Cult. Psychol. 15, 363–371. doi: 10.1177/1354067X09337870

Thibault, P., Levesque, M., Gosselin, P., and Hess, U. (2012). The Duchenne marker is not a universal signal of smile authenticity – but it can be learned! Soc. Psychol. 43, 215–221. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000122

Trommsdorff, G. (2012). Development of ‘agentic’ regulation in cultural context: the role of self and world views. Child Dev. Perspect. 6, 19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00224.x

Tsai, J. L., Ang, J. Y. Z., Blevins, E., Goernandt, J., Fung, H. H., Jiang, D., et al. (2016). Leaders’ smiles reflect cultural differences in ideal affect. Emotion 16, 183–195. doi: 10.1037/emo0000133

Tsai, J. L., Louie, J., Chen, E. E., and Uchida, Y. (2007). Learning what feelings to desire: socialization of ideal affect through children’s storybooks. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 33, 17–30. doi: 10.1177/0146167206292749

Vandello, J. A., Cohen, D., and Ransom, S. (2008). U.S. southern and northern differences in perceptions of norms about aggression mechanisms for the perpetuation of a culture of honor. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 39, 162–177. doi: 10.1177/0022022107313862

Wan, K., and Savina, E. (2015). Emotion regulation strategies in European American and Hong Kong Chinese middle school children. Contemp. School Psychol. 20, 152–159. doi: 10.1007/s40688-015-0059-5

White, G. M. (1987). “Proverbs and cultural models: an American psychology of problem solving,” in Cultural Models in Language and Thought, eds D. Holland and N. Quinn (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press),269–289.

Wiafe-Akenten, N. A., Adomako, K., and Adusei, E. (2017). “Kwatikwan?: kasa nsesaeε sohyiɔ-pragmateks dwumadie wɔ εnnε mmerε yi radio ne TV so,” in Paper Presented at the Second School of Languages Conference, University of Ghana, Legon.

World Values Survey Database (2018). Available at: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp [accessed April 1, 2018].

Yankah, K. (1995). Speaking for the Chief: Ȯkyeame and the Politics of Akan Royal Oratory (African Systems of Thought). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Keywords: culture, emotion, Africa, emotion regulation, emotion display rules

Citation: Dzokoto VA, Osei-Tutu A, Kyei JJ, Twum-Asante M, Attah DA and Ahorsu DK (2018) Emotion Norms, Display Rules, and Regulation in the Akan Society of Ghana: An Exploration Using Proverbs. Front. Psychol. 9:1916. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01916

Received: 31 January 2018; Accepted: 18 September 2018;

Published: 31 October 2018.

Edited by:

Michio Nomura, Kyoto University, JapanReviewed by:

Kosuke Takemura, Shiga University, JapanRonald Fischer, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Copyright © 2018 Dzokoto, Osei-Tutu, Kyei, Twum-Asante, Attah and Ahorsu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vivian A. Dzokoto, dmR6b2tvdG9AdmN1LmVkdQ==

Vivian A. Dzokoto

Vivian A. Dzokoto Annabella Osei-Tutu

Annabella Osei-Tutu Jane J. Kyei3

Jane J. Kyei3 Dzifa A. Attah

Dzifa A. Attah