- 1Department of Nutrition and Food Technology, Jashore University of Science and Technology, Jashore, Bangladesh

- 2Department of Biomolecular Innovation, Institute for Biomedical Sciences, Shinshu University, Nagano, Japan

Unmethylated cytosine–guanine dinucleotide (CpG) motifs are potent stimulators of the host immune response. Cellular recognition of CpG motifs occurs via Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9), which normally activates immune responses to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) indicative of infection. Oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) containing unmethylated CpGs mimic the immunostimulatory activity of viral/microbial DNA. Synthetic ODNs harboring CpG motifs resembling those identified in viral/microbial DNA trigger an identical response, such that these immunomodulatory ODNs have therapeutic potential. CpG DNA has been investigated as an agent for the management of malignancy, asthma, allergy, and contagious diseases, and as an adjuvant in immunotherapy. In this review, we discuss the potential synergy between synthetic ODNs and other synthetic molecules and their immunomodulatory effects. We also summarize the different synthetic molecules that function as immune modulators and outline the phenomenon of TLR-mediated immune responses. We previously reported a novel synthetic ODN that acts synergistically with other synthetic molecules (including CpG ODNs, the synthetic triacylated lipopeptide Pam3CSK4, lipopolysaccharide, and zymosan) that could serve as an immune therapy. Additionally, several clinical trials have evaluated the use of CpG ODNs with other immune factors such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, cytokines, and both endosomal and cell-surface TLR ligands as adjuvants for the augmentation of vaccine activity. Furthermore, we discuss the structural recognition of ODNs by TLRs and the mechanism of functional modulation of TLRs in the context of the potential application of ODNs as wide-spectrum therapeutic agents.

Introduction

The immune system provides biosecurity against aggression by pathogens. The human body maintains impediments to prohibit entrance by microbes. Innate and adaptive components are part of the immune system. Innate immune responses provide a prompt response by the body. Innate immune reactions are mediated by Toll-like receptors (TLRs), a representative, evolutionarily conserved group of proteins that are able to induce innate immune reactions, particularly against bacterial infections, through the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (1, 2), to recognize and eradicate invading organisms (3). The germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) recognize conserved molecular patterns that activate the innate immune system. This response is coordinated by specialized cells such as basophils, dendritic cells (DCs), eosinophils, macrophages, monocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, neutrophils, and NKT cells (4). PRRs bind to molecular identification molecules, fundamental structural molecules, or historical segments that are preserved among microbes. This provides the innate immune system with the ability to rapidly counter a comprehensive scope of contagious agents that contact the dermis and mucous membranes.

TLRs are an important family of PRRs that are activated by PAMPs expressed by bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa (5, 6). PAMPs are the key molecules that mediate microbial destruction by processes such as mobilization of phagocytes to infected tissues and microbial killing. TLR family members are classified into two types: cell membrane receptors and endosome-associated receptors. Here, lipoprotein is derived from gram-positive bacteria and induces signaling pathways through TLR2 and other receptors (7, 8). Lipopolysaccharide is a cell wall component of gram-negative bacteria that induces signaling through TLR4 (9). Flagellin (a TLR5 agonist) is derived from the cell wall of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Zymosan, an extract from S. cerevisiae, is recognized by another heterodimer, TLR2/6. These TLR agonists act as potent immune stimulators that activate adaptive immune responses as well as recognize microbial components such as lipids, lipoproteins, and flagella. Different types of TLR have different recognition sites. TLR3 recognizes double-stranded RNA, and TLR7/8 recognizes single-stranded RNA. On the other hand, the recognition site of TLR9 is single-stranded synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) or viral/microbial DNA. TLR9 also recognizes unmethylated cytosine-guanine dinucleotide (CpG) motifs (10–13) expressed in the intracellular vesicles of prokaryotic cells (e.g., endoplasmic reticulum, endosomes, and lysosomes).

TLRs are part of a universal group of molecules that consists of extracellular leucine-rich repeats and a cytoplasmic Toll interleukin-1 receptor domain (14). TLRs recognize PAMPs and have specific immune functions. TLR activation initiates and maintains innate and adaptive immune pathways in association with memory function (15). Adapters induce signaling cascades that terminate in the stimulation of nuclear factor kappa B, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and interferon (IFN) regulatory factors 1, 3, 5, and 7 (16). Collectively, these transcription factors induce a variety of cytokines, and chemokines, some of which regulate cellular proliferation, growth, and maintenance. Thus, TLRs are an important group of receptors through which the innate immune system recognizes invasive microorganisms. Here, we discuss the synergistic activities of TLR1/2, TLR4, TLR2/6 with synthetic ODNs in the immune system. Furthermore, we discuss the immune synergistic phenomenon of TLRs in the context of the potential application of ODNs as therapeutic agents.

Oligodeoxynucleotides as Immune Modulators

CpG ODNs

ODNs containing CpG motifs trigger host defense mechanisms that involve both innate and adaptive immune responses. TLR9 recognizes viral/microbial DNA containing CpG motifs, triggering alterations in the cellular redox balance and the induction of cell signaling pathways, including mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor kappa B (17). Bacterial DNA serves as a PAMP, which is recognized by the vertebrate immune system for coordination of immune responses correlated with immunity (18). CpGs are extremely prevalent in prokaryotic DNA, but rare in eukaryotic DNA (19, 20). Overall, CpG hexamer motifs contain one or more CpG-deoxynucleotides, and the number, position, spacing, and surrounding bases of these motifs mediate their immunostimulatory activities (21–23). These CpG-hexamer motifs also have species-specific activity, which is determined by their structural features and length (18, 24, 25). Another research group explored whether bacterial DNA combines with other bacterial products to trigger the secretion of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-12, IFN-γ, and IgM (26). CpG motifs of synthetic ODNs stimulate B cells (18, 27), NK cells (28, 29), and specialized antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to multiply and/or secrete a variety of cytokines, chemokines, and immunoglobulins (30–32). CpG class A (CpG-A) is particularly effective at stimulating NK cells and inducing production of IFN-α by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), whereas CpG class B (CpG-B) is an especially potent B-cell activator. CpG-driven immune activation aggravates inflammatory tissue deterioration, stimulates the advancement of autoimmune disorders, and enhances lethal shock (33–37).

CpG DNA has been sought after as a therapeutic agent and adjuvant immunotherapy for the treatment of cancer, asthma, allergies, and infectious diseases, but this agent frequently involves phosphorothioate or chemical modification. Such modification may lead to imperfections owing to integral toxicity combined with an ephemeral anticoagulant effect, induction of the complement cascade, or inhibition of a primary fibroblast growth component attached to surface receptors due to non-specific protein binding (38). Therefore, CpG DNA can activate Th1 cytokine production, which stimulates a cytotoxic T-cell response with increasing Ig production; this has been observed in the therapy of a wide spectrum of infections, including viral infections and inflammatory disorders (21, 39–41).

Several classes of CpG ODNs exist and are based on structural attributes and immunomodulatory actions. Examples include CpG-A (also known as type D) (42), which induces secretion of IFN-α and stimulates pDC maturation, and monomeric CpG-B (or type K) (42), which induces production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)- α, promotes pDC maturation, and fully stimulates B cells. Lastly, the dimeric CpG class C (CpG-C) incorporates elements of both CpG-A and CpG-B, albeit with intermediate strength. Different CpG ODNs are assembled CpG-A or CpG-B/C with a phosphorothioate backbone to avoid degradation by serum nucleases and to augment in vitro and in vivo activity. Apart from CpG-A, CpG-B, and CpG-C, some researchers have suggested another unique class, P-class CpG ODN (CpG-P) (41), which can induce IFN-α production more than class C ODNs due to inclusion of two palindromic sequences. Therefore, synthetic CpG ODNs are considered to be promising immunomodulators (40).

Novel Synergistic ODNs

The immunosynergistic effects of ODNs have been established in ODN research. Initially, research was conducted on the immunomodulatory (43), immunosuppressive (44, 45), and immunostimulatory (46) effects of ODNs. In 2017, Nigar et al. explored a novel ODN (named “iSN34”) incorporated into Lactobacillus rhamnosus, GGATCC53108, that has synergistic effects on the immune response in CpG-induced immune activation (47). The iSN34 sequence is TTCCTAAGCTTGAGGCCT (48). Originally, we evaluated inhibitory or suppressive ODN (iODNs) with a TTAGGG motif. In 2013, Ito et al. successfully designed an effective iODN (designated “iSG3”) and revealed that iSG3 has strong immunosuppressive activity (49). As a synergistic ODN, iSN34 could be incorporated with CpG to trigger the production of IL-6 and IL-6-secreting CD19+ B cells. Thus, iSN34 may be an extraordinarily impressive adjuvant-mediated vaccine via Th1 that defends against intracellular pathogens, or iSN34 may provide antibody-mediated immunity compared to extracellular pathogens (47). We also conducted further investigations into the synergistic induction of IL-6 by the consolidation of iSN34 with the cell wall components of bacteria (TLR1/TLR2, TLR4) and fungi (TLR2/TLR6) (48). This review focuses on the synergistic immune effects of combining CpG ODNs with synthetic molecules associated with TLR ligands targeting inflammation and autoimmune diseases.

Immunotherapeutic Application of ODNs and Other Synthetic Molecules

Prevention and Treatment of Innate and Adaptive Immunity Dysfunction

Innate and adaptive immune responses are two key components of the immune system. Innate immune feedback is recognized as the body's primary defense by which non-specific cells engulf foreign organisms and molecules. Many cells of the immune system (monocytes, macrophages, DCs, neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils) along with NK cells and NKT cells (50) harmonize this response. These specialized cells bind to molecular signatures and are triggered by germline-encoded PRRs, which are fundamental receptors that recognize molecules that are conserved among microbes. This allows the innate immune system to react expeditiously to an extensive spectrum of organisms and protects the dermis and mucous membranes. In the innate immune system, TLRs are recognized as pattern recognition molecules. Alternatively, in the adaptive immune system, APCs are frequently triggered by activation of TLRs, are limited in mobilization, but maintain a remarkably antigen-specific response. This is attained through T-cell and B-cell receptors following somatic recombination. The innate immune system effectively defends humans from an immense spectrum of contaminants by relying on antecedent molecules. Moreover, the innate immune system eliminates the infectious microorganisms that trigger PRRs. Therefore, an equity between stimulation and inhibition must be maintained to provide a secure and potent immune response. Further investigation of the activity and response of the innate immune system will support the design of reliable and efficient therapeutic interventions.

In the vertebrate immune system, viral/microbial DNA that acts as PAMPs coordinates immune responses involving both innate and adaptive immunity. This stimulates the proliferation of B cells and the production of cytokines such as IL-12, IFN-γ, IL-6, and TNF-α, and of co-stimulatory molecules by monocytes/macrophages, B cells, and DCs (51). In this context, the ability of bacterial DNA to induce IL-6 is of particular concern. Immunomodulatory CpG ODNs are currently being assessed to establish the optimum induction of specific cytokine profiles and the activation of individual and mouse immune cells. In 2017, Nigar et al. demonstrated the immune synergistic effects of a combination of a non-CpG ODN (iSN34) and a CpG ODN (CpG-B). The activity of iSN34 was combined with different types of CpG-ODNs. The synergistic effects of iSN34 and CpG-B to stimulate the production of IL-6 would be an immensely effective adjuvant for Th1-mediated vaccines. The combined activity may be advantageous for the avoidance or treatment of inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis, systemic-onset juvenile chronic arthritis, osteoporosis, and psoriasis (52–54). The synergistic effects of iSN34 and CpG ODN may have the unique ability to target the treatment of systemic inflammatory diseases.

Use of ODNs as Immunotherapeutics Against Inflammatory Diseases

Inflammation is a vital process in response to injury or infection that occurs through a sequence of events to produce wound healing and maintenance of normal tissue homeostasis. It is a complicated process involving molecular mechanisms that recognize specific molecular patterns associated with infection or tissue injury. The inflammatory response is mediated by key regulators that are proinflammatory molecules. Inflammation involves the contribution of many enzymes and the infiltration of heterogeneous cells that modify chemokine gradients as well as the inflammatory response (55, 56).

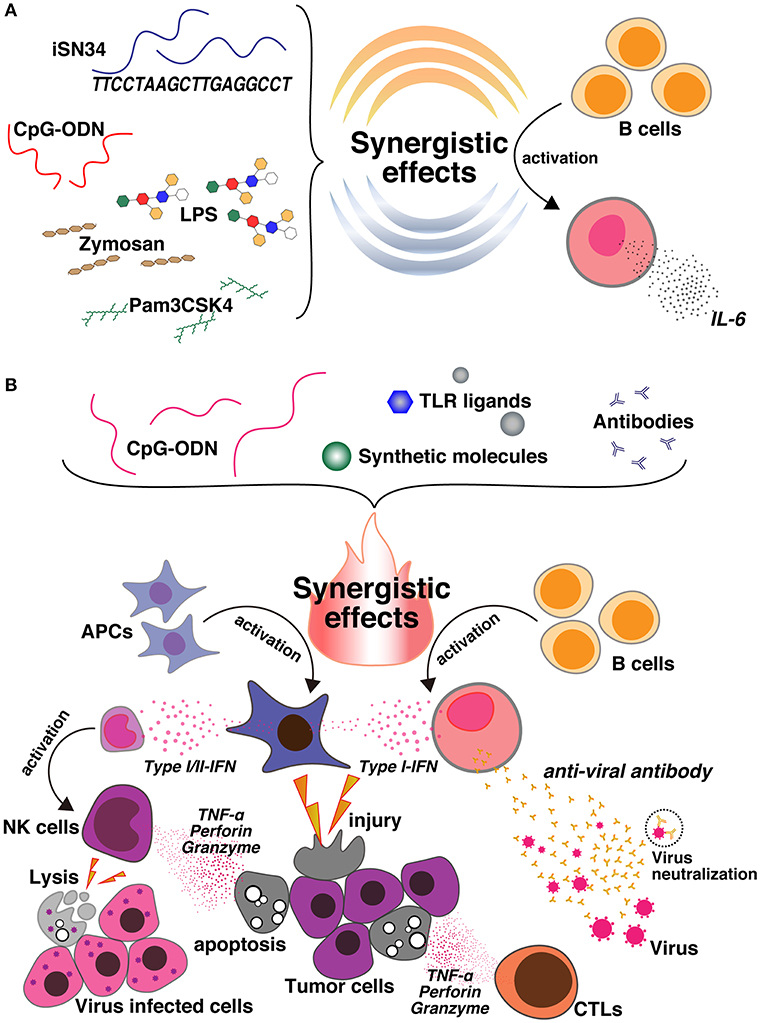

Unwanted inflammation occurs regardless of whether consolidation of TLR3/TLR9 agonists leads to IFN-α or B-cell activation or the potentially immunoregulatory function of IL-10 (57). In a model of measles virus pathogenesis, B-cell proliferation and antibody secretion are suppressed not only by maternal antibodies (58, 59), but also by T-cell responses (60–64). The main mechanism of B-cell responses includes the neutralization of live-attenuated vaccines, which reduces epitope masking and interferes with the recognition of antigens by B cells. Then, neutralizing antibodies can only produce a B-cell response when the antibody can attach to the Fcγ IIB receptor (CD32) on the B-cell surface (65). In 2018, Nigar et al. reported that association of iSN34 with TLR1/2, TLR4, and TLR2/6 induces IL-6, leading to a potent immune response (Figure 1A). They also revealed that the effects highlight the potential of TLRs, especially CD19+ cells, as managers of B-cell activation, which performs a vital role in antigen-autonomous evolution and immunology-induced activation of B cells. These results suggest that inflammatory diseases can perhaps be treated by targeting upstream progression in innate immune cells.

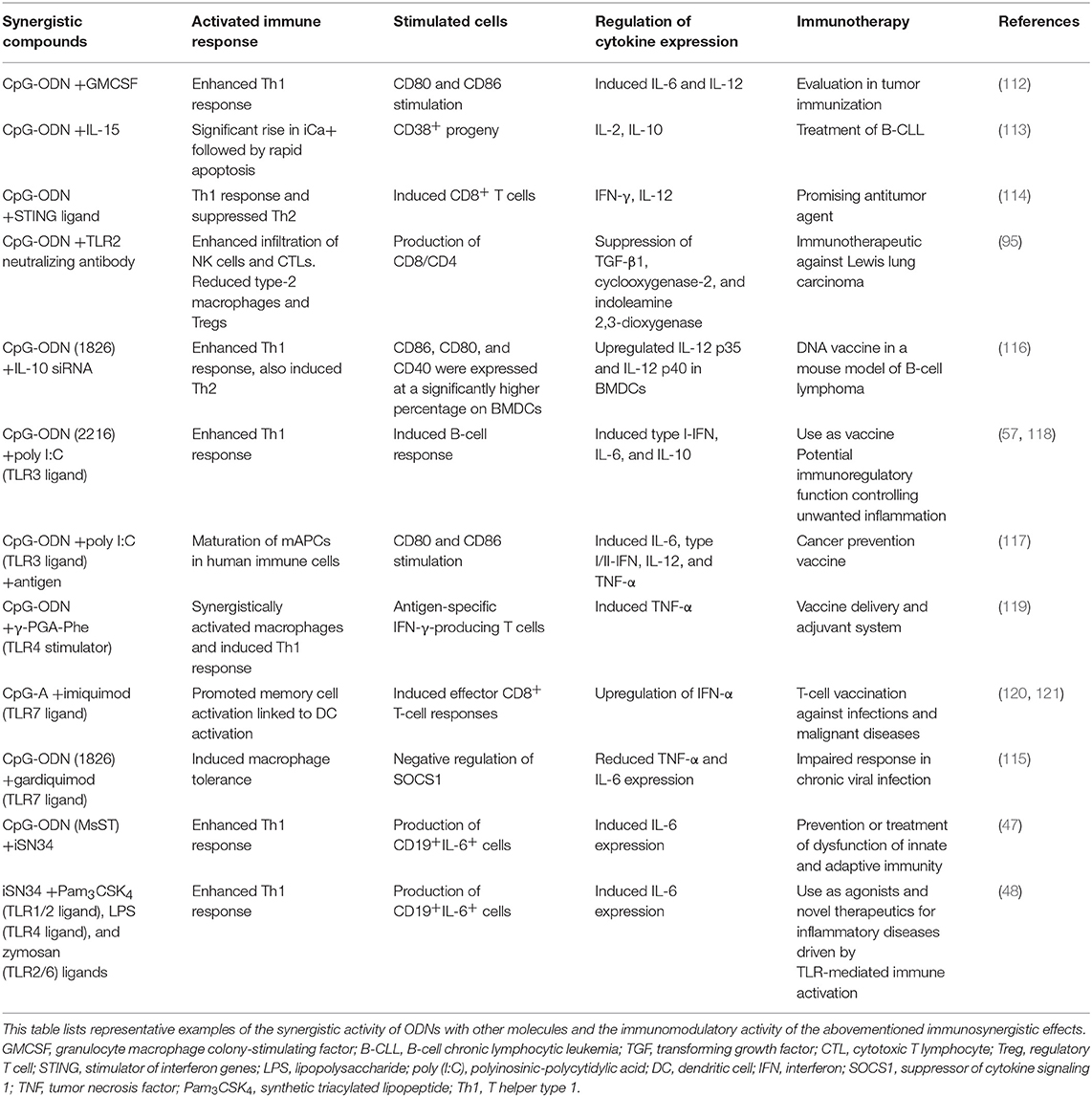

Figure 1. (A) CpG ODNs are synergistically activated with a novel ODN, iSN34, and other TLR ligands, such as Pam3CSK4 (TLR1/2), LPS (TLR4), and Zymosan (TLR2/6). This synergy enhances IL-6 induction and activates B cells. (B) Co-delivery of CpG ODNs and different TLR ligands, synthetic molecules, and antibodies produces an immunosynergistic response, which promotes the secretion of Type I/II-IFN cytokines and also the production of B cells. This leads to the generation of tumor-specific antibodies, which may be useful for enhancing antitumor agents, cancer vaccines, and the immunoregulatory effects against inflammatory disorders, as well as enhancing antiviral action and facilitating apoptosis. In contrast, the synergy of CpG and the synthetic molecule also activates NK cells, leads to cell lysis, and is useful for preparing vaccines against virally infected cells.

Vaccination

T-Cell Vaccination

T-cell lymphomas are infrequent, but antagonistic malignancies can occur due to resistance to chemotherapy and chemotoxicity. The combination of melanoma with recurrent spontaneous CD8+ T-cell responses is of clinical concern. In all enrolled patients, T-cell numbers improved following vaccination with Montanite (incomplete Freund's adjuvant, IFA) as an adjuvant treatment, and marked T-cell responses, which are associated with predominant generation of effector-memory-phenotype cells, were observed. Consequently, imiquimod induced a significant increase in the number of key-memory-phenotype cells and larger percentages of CD127+ (IL-7R) T cells in lymphoma, whereas imiquimod and CpG-ODN synergistically induced the growth of effector CD8+ T cells. Another investigation explored the T-cell induction properties associated with various adjuvants (IFA, imiquimod 5%) administered by unusual routes, such as subcutaneous, intradermal, and intranasal. That study did not report any autoimmune-related reactions after introducing immunotherapy with anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 antibody (ipilimumab) (66). By contrast, our data emphasize that significant proportions of central memory (CM)-phenotype cells (CD45RA−CCR7+) with enhanced expression of CD127 were induced by imiquimod. Therefore, in triggering the TLR7 agonist, imiquimod may elevate memory differentiation and potential T-cell responses (67–69). Despite the interest in memory cells, insufficient synthetic vaccines have been developed for the treatment of lymphoma. The generation of memory cells may depend on the canonical Wnt pathway with β-catenin/T-cell factor-1, the mammalian target of rapamycin, and AMP-activated protein kinase signaling pathways (67–69). Here, we indicate that the combination of imiquimod and IFA synergistically leads to the enhancement of memory-phenotype cells. This article documented that the synergistic effect of imiquimod and IFA may enhance vaccine efficacy (70), which supports the idea that innate immunity may be triggered via multiple microbe-associated molecular patterns.

Measles Vaccines

CpG ODNs, which are generally recognized as present in viral/microbial DNA, but are unusual in mammalian DNA, enhance the innate immune response. ODNs and TLR ligands synergistically induce an immune response by triggering different signaling pathways and may affect antigen-dependent T-cell immune memory. Viruses induce type-I IFN through TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9. A combination of TLR3 and TLR9 agonists, which enhance the induction of type I IFN, was tested and found to fully activate the B-cell response after vaccination when assigned to inhibitory MeV-specific IgG. This mechanism suggests that TLR3 and TLR9 signal via the TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing IFN-α (TRIF)/interferon regulatory factor (IRF)-3 and MyD88/IRF-7 pathways, respectively, as well as IFN-α and IFN-β, respectively. The principal tenet is that an amalgam of these agonists would result in greater induction of type-I IFN because of the synergistic effects mediated through the IFN receptor. This review suggests that the measles vaccine may lead to an optimum antibody response, even though it is reassembled with TLR3 and TLR9 agonists, which may have enormous potential for clinical control. An essential issue that remains unresolved in vaccinology is the inhibition of vaccination against transmittable diseases in humans (71–77) and animals (78–86) by maternal antibodies. In a recent review of measles vaccines in both patients and cotton rats (61), a research group discovered a relevant model of measles virus pathogenesis and affirmed that the proliferation of B cells and secretion of antibodies are suppressed by maternal antibodies (62). In addition, T-cell responses are often noticeable (60, 63, 64, 66, 69). However, the suppressive mechanisms of B-cell responses by maternal antibodies comprise the neutralization of live attenuated vaccines. The neutralization of live attenuated vaccines is not reasonable because the immune response against protein vaccines is further inhibited by maternal antibodies, and B-cell responses can also be suppressed by non-neutralizing antibodies (69) and attach to the Fcγ IIB receptor (CD32) on the surface of B cells (87).

DNA Vaccine in a Mouse Model of B-Cell Lymphoma

B-cell lymphoma, also known as B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL), comprises 90% of NHLs, which develop from different stages of B-cell growth and development. NHL is a diverse group of disorders that have divergent ancestral, histologic, and clinical backgrounds. Patients with NHL initially receive treatment with rituximab, a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, as well as cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, and prednisone. Looking only at lymphoma targets, anti-CD20 contributes to B-cell deficiency through the following three essential mechanisms: (i) initiation of apoptosis, in which anti-CD20 inhibits intracellular signaling pathways; (ii) initiation of complement-dependent cytotoxicity; and (iii) approach to anti-CD20 targeted B cells (generally NK cells or macrophages), thereby stimulating antibody-dependent cytotoxicity (88).

The efficacy of cancer vaccines usually depends on the essential strength of Th1 and Th2 responses prompted by APCs and DCs, respectively. Th1-driven cytotoxic T-cell responses are effective for eradicating tumor cells. However, CpG ODNs, which are universally investigated TLR9 agonists, enhance the Th1 response and likewise result in substantial levels of the anti-inflammatory Th2-promoting cytokine IL-10, which could counteract the increasing Th1 response. Furthermore, concurrent immunotherapy with CpG ODNs and IL-10 siRNAs synergistically increases immune protection through a DNA vaccine against B-cell lymphoma in a prophylactic murine model. These outcomes suggest that PAMPs can be administered to modulate TLR ligand-mediated immune stimulation precisely in DCs through the co-delivery of cytokine-silencing siRNAs, thereby boosting antitumor immunity through an idiotype DNA vaccine in a mouse model of B-cell lymphoma.

Cancer Immunotherapy

Immunotherapeutics Against Lewis Lung Carcinoma

The TLR9 agonist CpG ODN has shown promise as an effective treatment for infectious disease, allergic disease and to have encouraging antitumor activity mediated by the stimulation of antitumor immunity in numerous animal models. Increasing evidence has shown significant advances in cancer immunotherapy, and numerous strategies have been developed to deliver a tumor-specific immune response (89). Here, the synergistic effect of a TLR2-neutralizing antibody and a TLR9 agonist CpG ODN was observed to advance coherent immunotherapy against tumor metastasis. The mechanism of action for this combination regimen has been investigated (90). Metastasis treatment with CpG ODNs plus an anti-TLR2 antibody synergistically suppressed and subsequently improved infiltration of NK and cytotoxic T cells, reduced the recruitment of type-2 macrophages and regulatory T cells, and reduced the expression of immunosuppressive factors together with transforming growth factor-β1, cyclooxygenase-2, and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. However, in a metastatic Lewis lung carcinoma mouse model, CpG ODNs and an anti-TLR2 antibody regimen eradicated synergistic immunosuppressive tissues from the tumor environment.

Immunosuppression by the TLR2 and TLR9 combination regimen on host immune and tumor cells for controlling metastatic behavior was associated with a nominal effect on initial subcutaneously embedded tumor growth (91–94). In 2007, Krieg demonstrated that CpG ODNs have a promising anticancer immunotherapeutic ability to trigger Th1 antibodies in the innate and adaptive immune system. On the other hand, TLR2 is an inimitable member of the TLR family because it activates an immunosuppressive response in vivo (95). The administration of CpG ODNs also improved the frequency of NK and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) infiltration, secretion of IFN-γ, and differentiation of M1 cells, but did not reduce the number of regulatory T cells in the spleen (89). These findings show that the synergistic effects of both CpG ODNs and the TLR2-neutralizing antibody are the result of enhanced immune cytotoxicity against tumor cells and show an anti-metastatic effect.

Evaluation of Tumor Immunization

In this review, we discuss the synergistic activity of CpG ODNs and stimulator of interferon gene (STING)-ligand cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate (cGAMP). The STING-cGAMP interaction and CpG ODNs terminate NK cells, lead to production of IFN-γ, have similar effects as IL-12 and type-I IFNs, and are differentially controlled by IRF3/7, STING, and MyD88. The aggregation of CpG ODNs and cGAMP is an effective type-1 adjuvant that leads to robust Th1-type and cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell responses. In murine tumor models, researchers administered intratumorally vaccinated CpG ODNs and cGAMP synergistically, which resulted in a significantly decreased tumor size. This treatment thus functioned as an antigen-free anticancer agent. Moreover, Th1 cells play vital roles in the generation of antitumor immunity, which resulted in suitable activation and effector functions of CTLs, including IFN-γ production (96, 97). Thus, Th1 cells are the key inducers of type-1 immunity and are preeminent in phagocytic activity (98, 99). An important feature of CpG ODNs, mainly D-type CpG ODNs, is that they strongly induce both type-I and type-II IFNs, and are also rather incapable of inducing B-cell activation (42, 46). Taken together, these findings indicate that the synergistic effects induced by K3 CpG and cGAMP may lead to potent activation of NKs and induction of IFN-γ. However, these mechanisms partially rely on IL-12 and type-I IFNs. This review also illustrates that the synergistic effects of CpG ODNs and cGAMP result in a strong antitumor agent, suggesting that synergy may be advantageous for immunotherapeutic applications (100).

Treatment of B-Cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) is the most prevalent adult leukemia, targeting mainly older individuals in the U.S., Europe, and Australia (101). Its clinical progression involves stroma-dependent B-CLL growth within lymphoid tissue. Mongini et al. reported that high proliferator status in vitro was linked to diminished patient survival with immunohistochemical evidence of apoptotic cells and IL-15-producing cells proximal to B-CLL pseudo-follicles in patients' spleens. They also suggested that ODNs and IL-15 signaling may synergistically promote in vivo B-CLL growth. B-CLL depends on TLR9 signals, which led some researchers to investigate whether in vitro exposure to CpG ODNs triggers the proliferation of blood-derived B-CLL (102–104), and whether co-stimuli may make TLR9 signals uniformly stimulatory for B cells. IL-15, an inflammatory cytokine produced by endothelial cells (105, 106), is a plausible candidate for promoting the TLR9-triggered growth of B-CLL. However, this cytokine is best known for its major effects on the growth or survival of NK cells, CD8+ T cells, and intra-epithelial γ/σ cells (107, 108). This suggests that the cooperation of CpG ODNs and recombinant human IL-15 may boost the response of B-CLL through TLR9 signaling and the survival of carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester-labeled B-CLL cells with approaches that have yielded important insights concerning clonal growth and the activation-induced death of normal human B cells (109–111).

Conclusion And Future Perspectives

This review emphasized the immune activity of CpG ODNs with synthetic molecules to produce an innate and adaptive immune system response. Overall, the results show that the incorporation of CpG ODNs and various synthetic molecules improves humoral and cellular immune responses. Thus, the synergistic effects of CpG ODNs enhance both Th1 and Th2 responses and advances maturation of APCs. This review demonstrated the widespread immune response involving CpG and different synthetic molecules such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (112), IL-15 (113), the STING ligand (114), Gardiquimod (115), IL-10 siRNA (116), poly (I:C) (57, 117, 118), encapsulated poly(γ-PGA-Phe) (119), imiquimod (120, 121), TLR2-neutralizing antibody (95), and iSN34 (47, 48) (Table 1). Furthermore, the application of CpG ODNs and synthetic molecules as adjuvant treatment was demonstrated to improve immunity even in cases with weakened immune systems. Most of the representative studies showed that CpG ODNs and other synthetic molecules induced the immunogenicity of B-cell and effector T-cell responses, macrophage stimulation, and antigen-specific IFN-γ-producing T cells. Therefore, the synergistic activity of CpG DNA and the abovementioned synthetic molecules can induce Th1 cytokine production, thereby stimulating CTLs with increasing Ig production. These activities play a role in the treatment of an extensive spectrum of diseases, comprising cancer, viral and bacterial infections, allergic diseases, and inflammatory disorders (21, 35, 122, 123). Interestingly, these studies also confirmed the clear synergistic activity of TLR9 agonist CpG ODNs and different synthetic molecules (Figure 1B), which may be effective for enhancing immunoregulation in inflammatory disorders, or for heat-killed Brucella abortus (HKBa) treatment, antitumor agents, DNA vaccines for B-CLL, measles vaccines, T-cell vaccines, cancer vaccines, and treatment of Lewis lung carcinoma, as well as antiviral action. Patients administered adjuvanted vaccines produced stronger antigen-specific serum antibodies and CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses. Anticancer immunity was produced more quickly in cases immunized with CpG-adjuvanted vaccines (124). However, the immune effects varied, and the effects of CpG ODNs and other immune factors, such as the frequency of NK cells or DCs, were seldom reproducible (100, 125–128). Certainly, demonstrating that the vaccine/adjuvant formulations (synergistic CpG ODNs and synthetic molecules) examined reproducibly change the advancement of tumors is essential. Of greater importance, the immune responses observed barely corresponded to clinical assumptions.

Table 1. Synergistic effects of oligodeoxynucleotides combined with synthetic compounds on immunotherapy.

Based on the results outlined above, we considered the immunological aspects and ability of vaccine adjuvants to be suitable for use in antitumor immunotherapy, because the mechanisms of activity have been observed in vitro and in vivo. Additionally, this combination should be evaluated in vivo by estimating the initiation of antigen-specific T-cell and B-cell responses after combination immunization in an immunization model. Therefore, our results provide insight into the processes of the associated response of TLR9 and specific synthetic molecules, which potentially encourage the immunotherapeutic and adjuvant equities of their combination.

Author Contributions

SN and TS conceived, designed, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

The review was funded by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (No. 17H03907) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) to TS.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The iSN34 study mentioned in this review is based on the doctorate thesis by SN from Shinshu University, Japan. The new knowledge from the iSN34 study was described in this review and may be a therapeutic advancement in immunology research.

References

1. Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat Immunol. (2001) 2:675–80. doi: 10.1038/90609

2. Takeda K, Akira S. Roles of Toll-like receptors in innate immune responses. Genes Cells. (2001) 6:733–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00458.x

3. Akira S, Hemmi H. Recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by TLR family. Immunol Lett. (2003) 85:85–95. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2478(02)00228-6

4. Medzhitov R, Janeway CA Jr. Innate immunity: impact on the adaptive immune response. Curr Opin Immunol. (1997) 9:4–9. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(97)80152-5

5. Kumagai Y, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pathogen recognition by innate receptors. J Infect Chemother. (2008) 14:86–92. doi: 10.1007/s10156-008-0596-1

6. Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. (2003) 21:335–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126

7. Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and their signaling mechanism in innate immunity. Acta Odontol Scand. (2001) 59:124–30. doi: 10.1080/000163501750266701

8. Patel M, Xu D, Kewin P, Choo-Kang B, McSharry C, Thomson NC, et al. TLR2 agonist ameliorates established allergic airway inflammation by promoting Th1 response and not via regulatory T cells. J Immunol. (2005) 174:7558–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7558

9. Akashi S, Shimazu R, Ogata H, Nagai Y, Takeda K, Kimoto M, et al. Cutting edge: cell surface expression and lipopolysaccharide signaling via the toll-like receptor 4-MD-2 complex on mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. (2000) 164:3471–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3471

10. Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. (2001) 413:732–8. doi: 10.1038/35099560

11. Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, Ampenberger F, Kirschning C, Akira S, et al. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science. (2004) 303:1526–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620

12. Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. (2010) 11:373–84. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863

13. Takeshita F, Leifer CA, Gursel I, Ishii KJ, Takeshita S, Gursel M, et al. Cutting edge: role of Toll-like receptor 9 in CpG DNA-induced activation of human cells. J Immunol. (2001) 167:3555–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3555

14. Matsushima N, Tanaka T, Enkhbayar P, Mikami T, Taga M, Yamada K, et al. Comparative sequence analysis of leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) within vertebrate toll-like receptors. BMC Genomics. (2007) 8:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-124

15. Schmidlin H, Diehl SA, Blom B. New insights into the regulation of human B-cell differentiation. Trends Immunol. (2009) 30:277–85. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.03.008

16. Fitzgerald KA, Rowe DC, Barnes BJ, Caffrey DR, Visintin A, Latz E, et al. LPS-TLR4 signaling to IRF-3/7 and NF-kappaB involves the toll adapters TRAM and TRIF. J Exp Med. (2003) 198:1043–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031023

17. Krieg AM. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA and their immune effects. Annu Rev Immunol. (2002) 20:709–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064842

18. Krieg AM, Yi AK, Matson S, Waldschmidt TJ, Bishop GA, Teasdale R, et al. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA trigger direct B-cell activation. Nature. (1995) 374:546–9. doi: 10.1038/374546a0

19. Cardon LR, Burge C, Clayton DA, Karlin S. Pervasive CpG suppression in animal mitochondrial genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1994) 91:3799–803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3799

20. Razin A, Friedman J. DNA methylation and its possible biological roles. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. (1981) 25:33–52. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)60482-1

21. Klinman DM, Yi AK, Beaucage SL, Conover J, Krieg AM. CpG motifs present in bacteria DNA rapidly induce lymphocytes to secrete interleukin 6, interleukin 12, and interferon gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1996) 93:2879–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2879

22. Pisetsky DS. Immune responses to DNA in normal and aberrant immunity. Immunol Res. (2000) 22:119–26. doi: 10.1385/IR:22:2-3:119

23. Yamamoto M, Yoshizaki K, Kishimoto T, Ito H. IL-6 is required for the development of Th1 cell-mediated murine colitis. J Immunol. (2000) 164:4878–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4878

24. Bauer M, Redecke V, Ellwart JW, Scherer B, Kremer JP, Wagner H, et al. Bacterial CpG-DNA triggers activation and maturation of human CD11c-, CD123+ dendritic cells. J Immunol. (2001) 166:5000–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.5000

25. Chuang TH, Lee J, Kline L, Mathison JC, Ulevitch RJ. Toll-like receptor 9 mediates CpG-DNA signaling. J Leukoc Biol. (2002) 71:538–44.

26. Yi AK, Klinman DM, Martin TL, Matson S, Krieg AM. Rapid immune activation by CpG motifs in bacterial DNA. Systemic induction of IL-6 transcription through an antioxidant-sensitive pathway. J Immunol. (1996) 157:5394–402.

27. Ballas ZK, Rasmussen WL, Krieg AM. Induction of NK activity in murine and human cells by CpG motifs in oligodeoxynucleotides and bacterial DNA. J Immunol. (1996) 157:1840–5.

28. Sparwasser T, Miethke T, Lipford G, Erdmann A, Hacker H, Heeg K, et al. Macrophages sense pathogens via DNA motifs: induction of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated shock. Eur J Immunol. (1997) 27:1671–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270712

29. Verthelyi D, Ishii KJ, Gursel M, Takeshita F, Klinman DM. Human peripheral blood cells differentially recognize and respond to two distinct CPG motifs. J Immunol. (2001) 166:2372–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2372

30. Behboudi S, Chao D, Klenerman P, Austyn J. The effects of DNA containing CpG motif on dendritic cells. Immunology. (2000) 99:361–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00979.x

31. Sparwasser T, Koch ES, Vabulas RM, Heeg K, Lipford GB, Ellwart JW, et al. Bacterial DNA and immunostimulatory CpG oligonucleotides trigger maturation and activation of murine dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. (1998) 28:2045–54.

32. Stacey KJ, Sweet MJ, Hume DA. Macrophages ingest and are activated by bacterial DNA. J Immunol. (1996) 157:2116–22.

33. Cowdery JS, Chace JH, Yi AK, Krieg AM. Bacterial DNA induces NK cells to produce IFN-gamma in vivo and increases the toxicity of lipopolysaccharides. J Immunol. (1996) 156:4570–5.

34. Deng GM, Nilsson IM, Verdrengh M, Collins LV, Tarkowski A. Intra-articularly localized bacterial DNA containing CpG motifs induces arthritis. Nat Med. (1999) 5:702–5. doi: 10.1038/9554

35. Heikenwalder M, Polymenidou M, Junt T, Sigurdson C, Wagner H, Akira S, et al. Lymphoid follicle destruction and immunosuppression after repeated CpG oligodeoxynucleotide administration. Nat Med. (2004) 10:187–92. doi: 10.1038/nm987

36. Sparwasser T, Miethke T, Lipford G, Borschert K, Hacker H, Heeg K, et al. Bacterial DNA causes septic shock. Nature. (1997) 386:336–7. doi: 10.1038/386336a0

37. Zeuner RA, Verthelyi D, Gursel M, Ishii KJ, Klinman DM. Influence of stimulatory and suppressive DNA motifs on host susceptibility to inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. (2003) 48:1701–7. doi: 10.1002/art.11035

38. Henry AJ, Cook JP, McDonnell JM, Mackay GA, Shi J, Sutton BJ, et al. Participation of the N-terminal region of Cepsilon3 in the binding of human IgE to its high-affinity receptor FcepsilonRI. Biochemistry. (1997) 36:15568–78. doi: 10.1021/bi971299+

39. Kandimalla ER, Yu D, Agrawal S. Towards optimal design of second-generation immunomodulatory oligonucleotides. Curr Opin Mol Ther. (2002) 4:122–9.

40. Krieg AM. Therapeutic potential of Toll-like receptor 9 activation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2006) 5:471–84. doi: 10.1038/nrd2059

41. Samulowitz U, Weber M, Weeratna R, Uhlmann E, Noll B, Krieg AM, et al. A novel class of immune-stimulatory CpG oligodeoxynucleotides unifies high potency in type I interferon induction with preferred structural properties. Oligonucleotides. (2010) 20:93–101. doi: 10.1089/oli.2009.0210

42. Klinman DM. Immunotherapeutic uses of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Nat Rev Immunol. (2004) 4:249–58. doi: 10.1038/nri1329

43. Wang Y, Yamamoto Y, Shigemori S, Watanabe T, Oshiro K, Wang X, et al. Inhibitory/suppressive oligodeoxynucleotide nanocapsules as simple oral delivery devices for preventing atopic dermatitis in mice. Mol Ther. (2015) 23:297–309. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.239

44. Sato T, Yamamoto M, Shimosato T, Klinman DM. Accelerated wound healing mediated by activation of Toll-like receptor 9. Wound Repair Regen. (2010) 18:586–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2010.00632.x

45. Shirota H, Gursel I, Gursel M, Klinman DM. Suppressive oligodeoxynucleotides protect mice from lethal endotoxic shock. J Immunol. (2005) 174:4579–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4579

46. Wooldridge JE, Ballas Z, Krieg AM, Weiner GJ. Immunostimulatory oligodeoxynucleotides containing CpG motifs enhance the efficacy of monoclonal antibody therapy of lymphoma. Blood. (1997) 89:2994–8.

47. Nigar S, Yamamoto Y, Okajima T, Shigemori S, Sato T, Ogita T, et al. Synergistic oligodeoxynucleotide strongly promotes CpG-induced interleukin-6 production. BMC Immunol. (2017) 18:44. doi: 10.1186/s12865-017-0227-7

48. Nigar S, Yamamoto Y, Okajima T, Sato T, Ogita T, Shimosato T. Immune synergistic oligodeoxynucleotide from Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG enhances the immune response upon co-stimulation by bacterial and fungal cell wall components. Anim Sci J. (2018) 89:1504–11. doi: 10.1111/asj.13082

49. Ito Y, Shigemori S, Sato T, Shimazu T, Hatano K, Otani H, et al. Class I/II hybrid inhibitory oligodeoxynucleotide exerts Th1 and Th2 double immunosuppression. FEBS Open Bio. (2013) 3:41–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2012.11.002

50. Megjugorac NJ, Young HA, Amrute SB, Olshalsky SL, Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P. Virally stimulated plasmacytoid dendritic cells produce chemokines and induce migration of T and NK cells. J Leukoc Biol. (2004) 75:504–14. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603291

51. Zhao Q, Temsamani J, Zhou RZ, Agrawal S. Pattern and kinetics of cytokine production following administration of phosphorothioate oligonucleotides in mice. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. (1997) 7:495–502. doi: 10.1089/oli.1.1997.7.495

52. Atreya R, Mudter J, Finotto S, Mullberg J, Jostock T, Wirtz S, et al. Blockade of interleukin 6 trans signaling suppresses T-cell resistance against apoptosis in chronic intestinal inflammation: evidence in crohn disease and experimental colitis in vivo. Nat Med. (2000) 6:583–8. doi: 10.1038/75068

53. Collins LE, DeCourcey J, Rochfort KD, Kristek M, Loscher CE. A role for syntaxin 3 in the secretion of IL-6 from dendritic cells following activation of toll-like receptors. Front Immunol. (2014) 5:691. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00691

54. Ulevitch RJ, Tobias PS. Receptor-dependent mechanisms of cell stimulation by bacterial endotoxin. Annu Rev Immunol. (1995) 13:437–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002253

55. Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Aikawa E, Stangenberg L, Wurdinger T, Figueiredo JL, et al. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J Exp Med. (2007) 204:3037–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070885

56. Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Leukocyte behavior in atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Science. (2013) 339:161–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1230719

57. Kim D, Niewiesk S. Synergistic induction of interferon alpha through TLR-3 and TLR-9 agonists identifies CD21 as interferon alpha receptor for the B cell response. PLoS Pathog. (2013) 9:e1003233. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003233

58. Gans HA, Arvin AM, Galinus J, Logan L, DeHovitz R, Maldonado Y. Deficiency of the humoral immune response to measles vaccine in infants immunized at age 6 months. JAMA. (1998) 280:527–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.6.527

59. Naniche D. Human immunology of measles virus infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. (2009) 330:151–71. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-70617-5_8

60. Gans H, DeHovitz R, Forghani B, Beeler J, Maldonado Y, Arvin AM. Measles and mumps vaccination as a model to investigate the developing immune system: passive and active immunity during the first year of life. Vaccine. (2003) 21:3398–405. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00341-4

61. Gans H, Yasukawa L, Rinki M, DeHovitz R, Forghani B, Beeler J, et al. Immune responses to measles and mumps vaccination of infants at 6, 9, and 12 months. J Infect Dis. (2001) 184:817–26. doi: 10.1086/323346

62. Gans HA, Maldonado Y, Yasukawa LL, Beeler J, Audet S, Rinki MM, et al. IL-12, IFN-gamma, and T cell proliferation to measles in immunized infants. J Immunol. (1999) 162:5569–75.

63. Pueschel K, Tietz A, Carsillo M, Steward M, Niewiesk S. Measles virus-specific CD4 T-cell activity does not correlate with protection against lung infection or viral clearance. J Virol. (2007) 81:8571–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00160-07

64. Siegrist CA, Barrios C, Martinez X, Brandt C, Berney M, Cordova M, et al. Influence of maternal antibodies on vaccine responses: inhibition of antibody but not T cell responses allows successful early prime-boost strategies in mice. Eur J Immunol. (1998) 28:4138–48.

65. Kim D, Huey D, Oglesbee M, Niewiesk S. Insights into the regulatory mechanism controlling the inhibition of vaccine-induced seroconversion by maternal antibodies. Blood. (2011) 117:6143–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-320317

66. Bouwhuis MG, Ten Hagen TL, Suciu S, Eggermont AM. Autoimmunity and treatment outcome in melanoma. Curr Opin Oncol. (2011) 23:170–6. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328341edff

67. Araki K, Youngblood B, Ahmed R. The role of mTOR in memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Immunol Rev. (2010) 235:234–43. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00898.x

68. Finlay D, Cantrell DA. Metabolism, migration and memory in cytotoxic T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. (2011) 11:109–17. doi: 10.1038/nri2888

69. Gattinoni L, Zhong XS, Palmer DC, Ji Y, Hinrichs CS, Yu Z, et al. Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nat Med. (2009) 15:808–13. doi: 10.1038/nm.1982

70. Kasturi SP, Skountzou I, Albrecht RA, Koutsonanos D, Hua T, Nakaya HI, et al. Programming the magnitude and persistence of antibody responses with innate immunity. Nature. (2011) 470:543–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09737

71. Bjorkholm B, Granstrom M, Taranger J, Wahl M, Hagberg L. Influence of high titers of maternal antibody on the serologic response of infants to diphtheria vaccination at three, five and twelve months of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (1995) 14:846–50. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199510000-00005

72. Dagan R, Amir J, Mijalovsky A, Kalmanovitch I, Bar-Yochai A, Thoelen S, et al. Immunization against hepatitis A in the first year of life: priming despite the presence of maternal antibody. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2000) 19:1045–52. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200011000-00004

73. del Canho R, Grosheide PM, Mazel JA, Heijtink RA, Hop WC, Gerards LJ, et al. Ten-year neonatal hepatitis B vaccination program, The Netherlands, 1982–1992: protective efficacy and long-term immunogenicity. Vaccine. (1997) 15:1624–30. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(97)00080-7

74. Englund JA, Anderson EL, Reed GF, Decker MD, Edwards KM, Pichichero ME, et al. The effect of maternal antibody on the serologic response and the incidence of adverse reactions after primary immunization with acellular and whole-cell pertussis vaccines combined with diphtheria and tetanus toxoids. Pediatrics. (1995) 96(Pt 2):580–4.

75. Letson GW, Shapiro CN, Kuehn D, Gardea C, Welty TK, Krause DS, et al. Effect of maternal antibody on immunogenicity of hepatitis A vaccine in infants. J Pediatr. (2004) 144:327–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.11.030

76. Sormunen H, Stenvik M, Eskola J, Hovi T. Age- and dose-interval-dependent antibody responses to inactivated poliovirus vaccine. J Med Virol. (2001) 63:305–10.

77. Trollfors B. Factors influencing antibody responses to acellular pertussis vaccines. Dev Biol Stand. (1997) 89:279–82.

78. Bradshaw BJ, Edwards S. Antibody isotype responses to experimental infection with bovine herpesvirus 1 in calves with colostrally derived antibody. Vet Microbiol. (1996) 53:143–51. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(96)01242-4

79. Ellis JA, Gow SP, Goji N. Response to experimentally induced infection with bovine respiratory syncytial virus following intranasal vaccination of seropositive and seronegative calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2010) 236:991–9. doi: 10.2460/javma.236.9.991

80. Fulton RW, Briggs RE, Payton ME, Confer AW, Saliki JT, Ridpath JF, et al. Maternally derived humoral immunity to bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) 1a, BVDV1b, BVDV2, bovine herpesvirus-1, parainfluenza-3 virus bovine respiratory syncytial virus, Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida in beef calves, antibody decline by half-life studies and effect on response to vaccination. Vaccine. (2004) 22:643–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.08.033

81. Klinkenberg D, Moormann RJ, de Smit AJ, Bouma A, de Jong MC. Influence of maternal antibodies on efficacy of a subunit vaccine: transmission of classical swine fever virus between pigs vaccinated at 2 weeks of age. Vaccine. (2002) 20:3005–13. doi: 10.1016/S0042-207X(02)00283-X

82. Mondal SP, Naqi SA. Maternal antibody to infectious bronchitis virus: its role in protection against infection and development of active immunity to vaccine. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. (2001) 79:31–40. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(01)00248-3

83. van Jong MT, Kuhn EM, Makoschey B. A single vaccination with an inactivated bovine respiratory syncytial virus vaccine primes the cellular immune response in calves with maternal antibody. BMC Vet Res. (2010) 6:2. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-6-2

84. van Maanen C, Bruin G, de Boer-Luijtze E, Smolders G, de Boer GF. Interference of maternal antibodies with the immune response of foals after vaccination against equine influenza. Vet Q. (1992) 14:13–7. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1992.9694319

85. Waner T, Naveh A, Ben Meir NS, Babichev Z, Carmichael LE. Assessment of immunization response to canine distemper virus vaccination in puppies using a clinic-based enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay. Vet J. (1998) 155:171–5. doi: 10.1016/S1090-0233(98)80013-0

86. Waner T, Naveh A, Wudovsky I, Carmichael LE. Assessment of maternal antibody decay and response to canine parvovirus vaccination using a clinic-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Vet Diagn Invest. (1996) 8:427–32. doi: 10.1177/104063879600800404

87. Eidson CS, Thayer SG, Villegas P, Kleven SH. Vaccination of broiler chicks from breeder flocks immunized with a live or inactivated oil emulsion Newcastle disease vaccine. Poult Sci. (1982) 61:1621–9. doi: 10.3382/ps.0611621

88. Huang H, Hao S, Li F, Ye Z, Yang J, Xiang J. CD4+ Th1 cells promote CD8+ Tc1 cell survival, memory response, tumor localization and therapy by targeted delivery of interleukin 2 via acquired pMHC I complexes. Immunology. (2007) 120:148–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02452.x

89. King J, Waxman J, Stauss H. Advances in tumour immunotherapy. QJM. (2008) 101:675–83. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcn050

90. Yang HZ, Cui B, Liu HZ, Mi S, Yan J, Yan HM, et al. Blocking TLR2 activity attenuates pulmonary metastases of tumor. PLoS ONE. (2009) 4:e6520. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006520

91. Kim S, Takahashi H, Lin WW, Descargues P, Grivennikov S, Kim Y, et al. Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature. (2009) 457:102–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07623

92. Netea MG, Van der Meer JW, Kullberg BJ. Toll-like receptors as an escape mechanism from the host defense. Trends Microbiol. (2004) 12:484–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.09.004

93. Wang C, Cao S, Yan Y, Ying Q, Jiang T, Xu K, et al. TLR9 expression in glioma tissues correlated to glioma progression and the prognosis of GBM patients. BMC Cancer. (2010) 10:415. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-415

94. Xie W, Wang Y, Huang Y, Yang H, Wang J, Hu Z. Toll-like receptor 2 mediates invasion via activating NF-kappaB in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2009) 379:1027–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.009

95. Yan J, Hua F, Liu HZ, Yang HZ, Hu ZW. Simultaneous TLR2 inhibition and TLR9 activation synergistically suppress tumor metastasis in mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. (2012) 33:503–12. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.193

96. Mantovani A, Sica A. Macrophages, innate immunity and cancer: balance, tolerance, and diversity. Curr Opin Immunol. (2010) 22:231–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.009

97. Spellberg B, Edwards JE Jr. Type 1/Type 2 immunity in infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. (2001) 32:76–102. doi: 10.1086/317537

98. Hung K, Hayashi R, Lafond-Walker A, Lowenstein C, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. The central role of CD4(+) T cells in the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med. (1998) 188:2357–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2357

99. Vesely MD, Kershaw MH, Schreiber RD, Smyth MJ. Natural innate and adaptive immunity to cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. (2011) 29:235–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101324

100. Nigar S. A study on the immune effects of synergistic oligodeoxynucleotide from probiotics (Dissertation/Doctor's thesis). Shinshu University, Minamiminowa, Japan (2018).

101. van Gent R, Kater AP, Otto SA, Jaspers A, Borghans JA, Vrisekoop N, et al. In vivo dynamics of stable chronic lymphocytic leukemia inversely correlate with somatic hypermutation levels and suggest no major leukemic turnover in bone marrow. Cancer Res. (2008) 68:10137–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2325

102. Decker T, Schneller F, Sparwasser T, Tretter T, Lipford GB, Wagner H, et al. Immunostimulatory CpG-oligonucleotides cause proliferation, cytokine production, and an immunogenic phenotype in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Blood. (2000) 95:999–1006.

103. Jahrsdorfer B, Wooldridge JE, Blackwell SE, Taylor CM, Griffith TS, Link BK, et al. Immunostimulatory oligodeoxynucleotides induce apoptosis of B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. J Leukoc Biol. (2005) 77:378–87. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0604373

104. Longo PG, Laurenti L, Gobessi S, Petlickovski A, Pelosi M, Chiusolo P, et al. The Akt signaling pathway determines the different proliferative capacity of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B-cells from patients with progressive and stable disease. Leukemia. (2007) 21:110–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404417

105. Oppenheimer-Marks N, Brezinschek RI, Mohamadzadeh M, Vita R, Lipsky PE. Interleukin 15 is produced by endothelial cells and increases the transendothelial migration of T cells in vitro and in the SCID mouse-human rheumatoid arthritis model in vivo. J Clin Invest. (1998) 101:1261–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI1986

106. Park CS, Yoon SO, Armitage RJ, Choi YS. Follicular dendritic cells produce IL-15 that enhances germinal center B cell proliferation in membrane-bound form. J Immunol. (2004) 173:6676–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6676

107. Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. Interleukin 15: biology and relevance to human disease. Blood. (2001) 97:14–32. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.1.14

108. Malamut G, El Machhour R, Montcuquet N, Martin-Lanneree S, Dusanter-Fourt I, Verkarre V, et al. IL-15 triggers an antiapoptotic pathway in human intraepithelial lymphocytes that is a potential new target in celiac disease-associated inflammation and lymphomagenesis. J Clin Invest. (2010) 120:2131–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI41344

109. Lee H, Haque S, Nieto J, Trott J, Inman JK, McCormick S, et al. A p53 axis regulates B cell receptor-triggered, innate immune system-driven B cell clonal expansion. J Immunol. (2012) 188:6093–108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103037

110. Mongini PK, Inman JK, Han H, Fattah RJ, Abramson SB, Attur M. APRIL and BAFF promote increased viability of replicating human B2 cells via mechanism involving cyclooxygenase 2. J Immunol. (2006) 176:6736–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6736

111. Mongini PK, Inman JK, Han H, Kalled SL, Fattah RJ, McCormick S. Innate immunity and human B cell clonal expansion: effects on the recirculating B2 subpopulation. J Immunol. (2005) 175:6143–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6143

112. Liu HM, Newbrough SE, Bhatia SK, Dahle CE, Krieg AM, Weiner GJ. Immunostimulatory CpG oligodeoxynucleotides enhance the immune response to vaccine strategies involving granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood. (1998) 92:3730–6.

113. Mongini PK, Gupta R, Boyle E, Nieto J, Lee H, Stein J, et al. TLR-9 and IL-15 synergy promotes the in vitro clonal expansion of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. J Immunol. (2015) 195:901–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403189

114. Temizoz B, Kuroda E, Ohata K, Jounai N, Ozasa K, Kobiyama K, et al. TLR9 and STING agonists synergistically induce innate and adaptive type-II IFN. Eur J Immunol. (2015) 45:1159–69. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445132

115. Lee HJ, Kim KC, Han JA, Choi SS, Jung YJ. The early induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 and the downregulation of toll-like receptors 7 and 9 induce tolerance in costimulated macrophages. Mol Cells. (2015) 38:26–32. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2015.2136

116. Pradhan P, Qin H, Leleux JA, Gwak D, Sakamaki I, Kwak LW, et al. The effect of combined IL10 siRNA and CpG ODN as pathogen-mimicking microparticles on Th1/Th2 cytokine balance in dendritic cells and protective immunity against B cell lymphoma. Biomaterials. (2014) 35:5491–504. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.039

117. Bayyurt B, Tincer G, Almacioglu K, Alpdundar E, Gursel M, Gursel I. Encapsulation of two different TLR ligands into liposomes confer protective immunity and prevent tumor development. J Control Release. (2017) 247:134–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.01.004

118. Kim D, Niewiesk S. Synergistic induction of interferon alpha through TLR-3 and TLR-9 agonists stimulates immune responses against measles virus in neonatal cotton rats. Vaccine. (2014) 32:265–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.013

119. Shima F, Uto T, Akagi T, Akashi M. Synergistic stimulation of antigen presenting cells via TLR by combining CpG ODN and poly(gamma-glutamic acid)-based nanoparticles as vaccine adjuvants. Bioconjug Chem. (2013) 24:926–33. doi: 10.1021/bc300611b

120. Goldinger SM, Dummer R, Baumgaertner P, Mihic-Probst D, Schwarz K, Hammann-Haenni A, et al. Nano-particle vaccination combined with TLR-7 and−9 ligands triggers memory and effector CD8(+) T-cell responses in melanoma patients. Eur J Immunol. (2012) 42:3049–61. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142361

121. Sacre K, Criswell LA, McCune JM. Hydroxychloroquine is associated with impaired interferon-alpha and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. (2012) 14:R155. doi: 10.1186/ar3895

122. Dalpke A, Zimmermann S, Heeg K. CpG DNA in the prevention and treatment of infections. BioDrugs. (2002) 16:419–31. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200216060-00003

123. Sato Y, Roman M, Tighe H, Lee D, Corr M, Nguyen MD, et al. Immunostimulatory DNA sequences necessary for effective intradermal gene immunization. Science. (1996) 273:352–4. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5273.352

124. Scheiermann J, Klinman DM. Clinical evaluation of CpG oligonucleotides as adjuvants for vaccines targeting infectious diseases and cancer. Vaccine. (2014) 32:6377–89. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.065

125. Fujiki F, Oka Y, Kawakatsu M, Tsuboi A, Tanaka-Harada Y, Hosen N, et al. A clear correlation between WT1-specific Th response and clinical response in WT1 CTL epitope vaccination. Anticancer Res. (2010) 30:2247–54.

126. Hara I, Takechi Y, Houghton AN. Implicating a role for immune recognition of self in tumor rejection: passive immunization against the brown locus protein. J Exp Med. (1995) 182:1609–14. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1609

127. Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Restifo NP. CD8+ T-cell memory in tumor immunology and immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. (2006) 211:214–24. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00391.x

Keywords: ligands, molecule, ODN, synergy, TLR

Citation: Nigar S and Shimosato T (2019) Cooperation of Oligodeoxynucleotides and Synthetic Molecules as Enhanced Immune Modulators. Front. Nutr. 6:140. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00140

Received: 17 May 2019; Accepted: 13 August 2019;

Published: 27 August 2019.

Edited by:

Pinyi Lu, Biotechnology HPC Software Applications Institute (BHSAI), United StatesReviewed by:

Margaret J. Lange, University of Missouri, United StatesBisheng Zhou, University of Illinois at Chicago, United States

Copyright © 2019 Nigar and Shimosato. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Takeshi Shimosato, c2hpbW90QHNoaW5zaHUtdS5hYy5qcA==

†ORCID: Takeshi Shimosato orcid.org/0000-0001-8132-1911

Shireen Nigar

Shireen Nigar Takeshi Shimosato

Takeshi Shimosato