- 1State Key Laboratory of Microbial Metabolism, MOST-USDA Joint Research Center for Food Safety, School of Agriculture and Biology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

- 2Shanghai Municipal Center for Disease Control & Prevention, Shanghai, China

Diverse mobile genetic elements (MGEs) including plasmids, insertion sequences, and integrons play an important role in the occurrence and spread of multidrug resistance (MDR) in bacteria. It was found in previous studies that IS26 and class 1 integrons integrated on plasmids to speed the dissemination of antibiotic-resistance genes in Salmonella. It is aimed to figure out the patterns of specific genetic arrangements between IS26 and class 1 integrons located in plasmids in MDR Salmonella in this study. A total of 74 plasmid-harboring Salmonella isolates were screened for the presence of IS26 by PCR amplification, and 39 were IS26-positive. Among them, 37 isolates were resistant to at least one antibiotic. The thirty-seven antibiotic-resistant isolates were further involved in PCR detection of class 1 integrons and variable regions, and all were positive for class 1 integrons. Six IS26-class 1 integron arrangements with IS26 inserted into the upstream or downstream of class 1 integrons were characterized. Eight combinations of these IS26-class 1 integron arrangements were identified among 31 antibiotic-resistant isolates. Multidrug-resistance plasmids of the IncHI2 incompatibility group were dominant, which all belonged to ST3 by plasmid double locus sequence typing. These 21 IncHI2-positive isolates harbored six complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns. Conjugation assays and Southern blot hybridizations confirmed that conjugative multidrug-resistance IncHI2 plasmids harbored the different complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements. The conjugation frequency of IncHI2 plasmids transferring alone was 10−5-10−6, reflecting that different complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns didn't significantly affect conjugation frequency (P > 0.05). These data suggested that class 1 integrons represent the hot spot for IS26 insertion, forming diverse MDR loci. And ST3-IncHI2 was the major plasmid lineage contributing to the horizontal transfer of composite IS26-class 1 integron MDR elements in Salmonella.

Introduction

Salmonella is recognized worldwide as a predominant pathogen causing foodborne diseases in humans (Yang et al., 2016). Multidrug resistance (MDR) among Salmonella toward numerous first-line agents, especially fluoroquinolones and extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs) that are recommended as primary treatment choices for severe infections, may jeopardize therapy options and reduce the effectiveness of invasive Salmonellosis treatment (Folster et al., 2015; Tadesse et al., 2016). The recruitment, dissemination and rapid evolution of diverse antibiotic resistance in bacteria has been largely manipulated by mobile genetic elements (MGEs) such as plasmids, insertion sequences (ISs), transposons (Tns) and integrons via horizontal gene transfer (HGT) (Brown-Jaque et al., 2015). A typical example is that Acinetobacter baumannii isolates with a plasmid bearing ISAba1-blaOXA−51−like gene had higher rates of resistance to imipenem and meropenem than those with the genes chromosomally encoded, probably due to increased gene dosage via higher copy number of associated plasmids (Chen et al., 2010).

Integrons are DNA elements capable of capturing and mobilizing exogenously functional gene cassettes, potentially permitting rapid adaptation to selective pressure and endowing increased fitness to the host (Deng et al., 2015). The class 1 integron is the most prevalent type associated with MDR Salmonella, playing a critical role in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance among various bacterial species (Li R. et al., 2013; Abraham et al., 2014). In addition, other MGEs could serve as vast reservoirs and massive genetic pool for integrons, facilitating their further extensive distribution (Sunde et al., 2015). ISs are the simplest autonomous mobile elements capable of transposing and altering the expression of neighboring genes (Siguier et al., 2014). IS26 in multiple copies frequently reside in MDR plasmids flanking antibiotic resistance genes, performing actively in the fusion and reorganization of different plasmid replicons as well as the creation and diffusion of various MDR regions via a replicative mechanism or a translocatable unit (TU) (Harmer et al., 2014; He et al., 2015; García et al., 2016). It's noteworthy that IS26 has been discovered to insert into and rearrange class 1 integrons, generating novel multi-resistance loci embedded in conjugative plasmids (Miriagou et al., 2005; Povilonis et al., 2010; Lai et al., 2013). The transposition activity of IS26 collaborates with capture and integration of class 1 integrons, resembling resistance gene clusters onto a single plasmid and resulting in the occurrence and spread of MDR. Unfortunately, there is very little research directly targeting on the correlation between IS26 and the class 1 integron in Salmonella, providing little highlights to trace IS26-class 1 integron-mediated MDR transmission and the evolution of MDR Salmonella under antibiotic selective pressure.

In this study, we analyzed IS26 prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, class 1 integrons, and complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements as well as their transfer functionality among Salmonella isolates. The objective of this study was to figure out regularity of specific genetic arrangements between IS26 and class 1 integrons in Salmonella as well as to clarify the molecular mechanism of transferable IS26-class 1 integron-mediated MDR.

Materials and Methods

Salmonella Isolates

A total of 74 plasmid-harboring Salmonella isolates were used in this study, of which 37 were food isolates and 37 were clinical isolates. Among these Salmonella isolates, clinical isolates were collected by Shanghai Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention and Wuhan Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention, while food isolates were collected from beef, poultry, pork, shrimp, vegetables, fresh juice, and shellfish. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing (PBRT) has been investigated by Chen et al. (2016). The detailed information of these isolates is listed in Table S1.

Screening of IS26-Positive Isolates

Genomic DNA of Salmonella isolates was extracted by the TIANamp Genomic DNA kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). All 74 Salmonella isolates were screened for the presence of IS26 by simplex PCR amplification, according to Rodríguezmartínez et al. (2013).

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

The resulting IS26-positive Salmonella isolates underwent antimicrobial susceptibility testing using the disk diffusion method against a panel of 21 antibiotics, according to the standards and guidelines recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (CLSI, 2013). A total of 21 antibiotic disks (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, UK) that included ampicillin (AMP, 10 μg), piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP, 100/10 μg), ampicillin/sulbactam (SAM, 10/10 μg), ceftriaxone (CRO, 30 μg), ceftazidime (CAZ, 30 μg), cefepime (FEP, 30 μg), cefotetan (CTT, 30 μg), aztreonam (ATM, 30 μg), cephazolin (CZO, 30 μg), ciprofloxacin (CIP, 5 μg), imipenem (IPM, 10 μg), amikacin (AMK, 30 μg), gentamicin (GEN, 10 μg), tobramycin (TOB, 10 μg), ertapenem (ETP, 10 μg), levofloxacin (LEV, 5 μg), nitrofurantoin (NIT, 300 μg), sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (SXT, 23.75/1.25 μg), streptomycin (STR, 10 μg), chloramphenicol (CHL, 30 μg), and tetracycline (TET, 30 μg) were assessed. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as control strain. Isolates were defined as MDR if they were resistant to at least three different classes of antibiotics.

Detection of Class 1 Integrons

The presence of class 1 integrons was determined by conventional PCR targeting the class 1 integrase gene intI1 and the qacEΔ1-sulI genes in the 3′-conserved segment (3′CS) using primers intI1-F/intI1-R and QS-F/QS-R respectively listed in Table S2 among IS26-positive antibiotic-resistant Salmonella isolates. Primers 5′CS/qacEΔ1R, 5′CS/3′CS, hep58/hep59, and 5′CS/hep59 (see Table S2) were then used to amplify gene cassettes within the variable region of class 1 integrons by a touch-down PCR protocol (annealing temperature decreasing from 60 to 50°C in 20 cycles, and then 15 cycles at 50°C). PCR products were purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen, USA) and sequenced by Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology Co., Ltd. Comparative analysis of nucleotide sequences was performed using the BLAST program at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) site (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast).

Genetic Context Analysis of Class 1 Integrons Associated With IS26

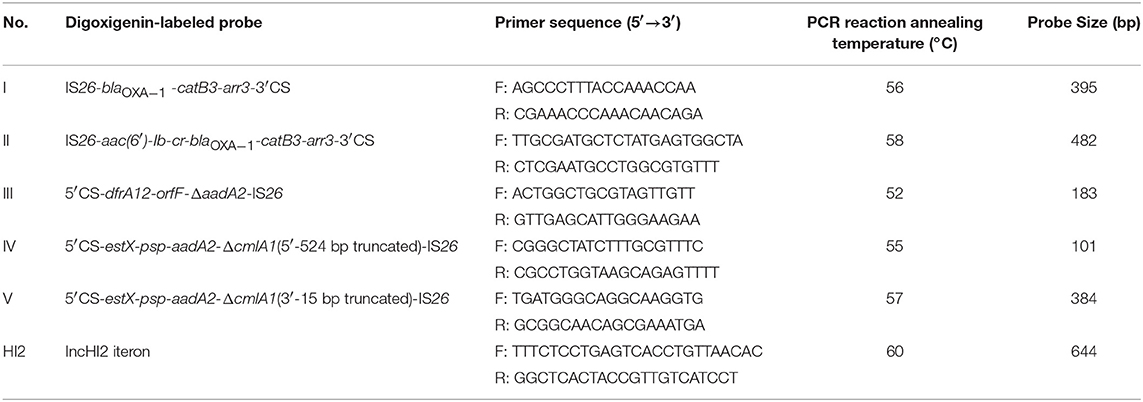

Genetic context associated with IS26 and class 1 integrons toward their frequently reported position relationship, was carried out by a touch-down PCR protocol (annealing temperature decreasing from 65 to 55°C in 20 cycles, and then 15 cycles at 50°C) among Salmonella isolates both positive for IS26 and class 1 integrons. Primers used were also listed in Table S2. Primers HS1081/qacEΔ1R targeted the IS26-class 1 integron relationship with the IS inserted into the upstream of class 1 integron, while primers 5′CS/IS26-F and 5′CS/IS26-3-F targeted the position relationship with the IS26 inserted into the downstream of class 1 integrons (Figure 1). PCR products were purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen, USA) and sequenced by Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology Co., Ltd. Comparative analysis of nucleotide sequences was performed using the BLAST program at the NCBI site (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of genetic association between IS26 and class 1 integrons toward their frequently reported position relationship with IS26 inserted into (A) the upstream or (B) the downstream of class 1 integrons. The dashed frames indicate the genes of the class 1 integron that may be truncated by IS26. The locations of the primers used for the PCR assay are represented with dark arrows.

IncHI2 Plasmid Characterization and Conjugation Experiment

IncHI2 was dominant incompatibility group in this study (Table S1). To better characterize IncHI2 plasmids, plasmid double locus sequence typing (pDLST) was performed as previously described (García-Fernández and Carattoli, 2010). To investigate the association between IncHI2 plasmids and complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements, the corresponding isolates harboring both elements underwent the liquid mating assay (Dang et al., 2016) using rifampin-resistant E. coli NK5449 as the recipient strain. Transconjugants were selected on LB agar plates supplemented with rifampin (200 μg/ml) and another appropriate antibiotic [kanamycin (50 μg/ml), streptomycin (50 μg/ml), tetracycline (50 μg/ml), or ciprofloxacin (16 μg/ml)]. Conjugation frequencies were also calculated as the number of transconjugants per recipient for several representative isolates. The putative transconjugants were examined for the antibiotic susceptibility profile using the same set of antibiotics, and for the presence of complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements as well as plasmid replicon type by PCR method as described above.

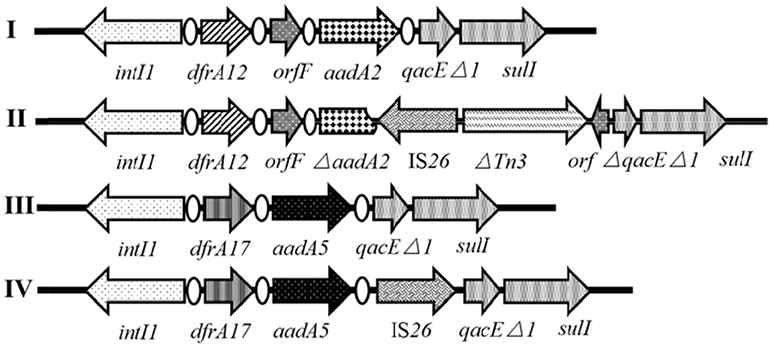

Confirmation of the IS26-Class 1 Integron Arrangements Located on IncHI2 Plasmids

The transconjugants harboring both IncHI2 plasmids and typical complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns were selected to determine the plasmid size and location of those typical complex arrangements. All types of IS26-class 1 integron arrangements and IncHI2 replicon were PCR amplified (Table 1) and then purified using Axyprep DNA gel extraction kit (Axygen, Corning, China). All PCR amplifications were performed with the following amplification scheme: 1 cycle of denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at different annealing temperature for 30 s and elongation at 72°C for 1 min. The amplification was concluded with an extension program of 1 cycle at 72°C for 10 min. The purified PCR products were labeled by DIG High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit I (Roche Applied Sciences, Germany) to be later used as Southern blot probes. The total DNA of transconjugants was first prepared in agarose plugs, digested with S1 nuclease (TaKaRa, China) and further separated by PFGE using CHEF-Mapper XA PFGE system (Bio-Rad, USA) to distinguish the plasmids of transconjugants (Dierikx et al., 2010). S. Braenderup H9812 universal size standard was used as PFGE marker (Hunter et al., 2005). The separated DNA fragments were transferred to a nylon membrane (Amersham, GE, USA), and then hybridized with the IncHI2 probe and corresponding digoxigenin-labeled IS26-class 1 integron arrangement probes, and finally detected using a NBT/BCIP color detection kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Sciences, Germany).

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Number

The nucleotide sequences of gene cassette arrays embedded in class 1 integrons found in this study have been deposited in GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ under the following accession numbers: KY399735 (dfrA12-orfF-ΔaadA2-IS26-ΔTn3-orf), KY399738 (dfrA17-aadA5-IS26), KY399736 (dfrA12-orfF-aadA2), and KY399737 (dfrA17-aadA5). The nucleotide sequences of characterized complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements have also been deposited in GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ under the following accession numbers: KY399739 (IS26-aac(6′)-Ib-cr-blaOXA−1-catB3-arr3-3′CS), KY399740 (IS26-blaOXA−1 -catB3-arr3-3′CS), KY399741 (IS26-ΔtnpR-tnpM-intI1-dfrA17-aadA5-3′CS), KY399744 (5′CS-estX-psp-aadA2-ΔcmlA1(5′-524 bp truncated)-IS26), KY399743 (5′CS-estX-psp-aadA2-ΔcmlA1(3′-15 bp truncated)-IS26), and KY399742 (5′CS-dfrA12-orfF-ΔaadA2-IS26).

Results and Discussion

IS26 Prevalence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility

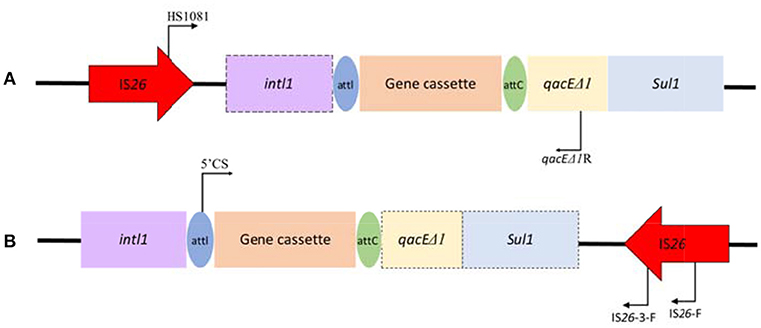

IS26 was present in 52.7% (39/74) of plasmid-harboring Salmonella isolates. Amongst the 39 IS26-positive isolates, 94.9% (37/39) demonstrated resistance to at least one antibiotic, of which 70.3% (26/37) showed MDR phenotypes. It's noteworthy that the strain SJTUF 10702 isolated from chicken exhibited resistance to 14 antibiotics. Among the 37 antibiotic-resistant isolates (Figure 2), resistance to individual agents was most frequently observed against TET (83.8%) and AMP (78.4%), followed by SAM (59.5%) and STR (51.4%). Resistance to CHL (45.9%), TOB (40.5%), SXT (35.1%), GEN (27.0%), CZO (21.6%), CIP (21.6%), CRO (10.8%), LEV (10.8%), CAZ (5.4%), AMK (2.7%), ATM (2.7%), CTT (2.7%), and NIT (2.7%) were less common. No resistance was detected to TZP, FEP, IPM, and ETP.

Figure 2. The resistance to individual agents among 37 IS26-carrying antibiotic-resistant Salmonella isolates. The antibiotics listed are abbreviated as follows: AMK, amikacin; AMP, Ampicillin; ATM, aztreonam; CAZ, ceftazidime; CHL, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CRO, ceftriaxone; CTT, cefotetan; CZO, cephazolin; GEN, gentamicin; LEV, levofloxacin; NIT, nitrofurantoin; SAM, ampicillin/sulbactam; STR, streptomycin; SXT, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim; TET, tetracycline; TOB, tobramycin.

Characterization of Class 1 Integrons

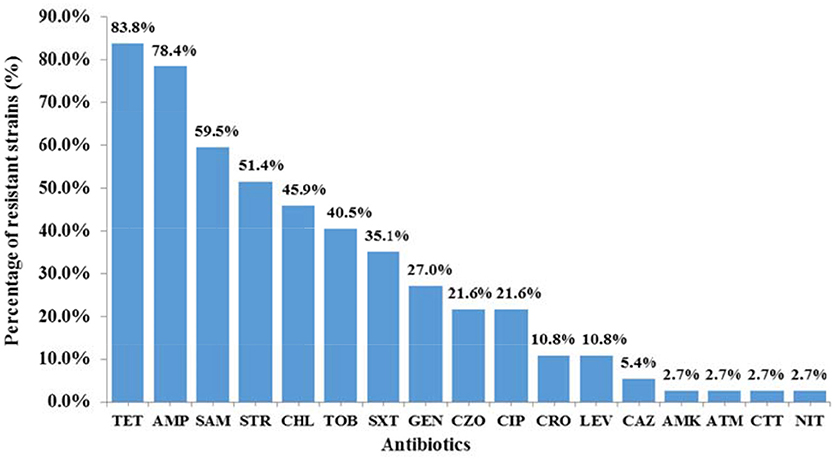

Both intI1 and qacEΔ1-sulI genes of the class 1 integron were detected in all of the 37 IS26-positive antibiotic-resistant Salmonella isolates, of which 16 (43.2%) isolates harbored variable regions clustered in four different cassette arrays (Figure 3, I~IV). Apart from qacEΔ1 and sulI genes responsible for resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds and sulfonamides, respectively, the four antibiotic resistance gene cassettes confer resistance to aminoglycosides with aadA2 or aadA5, and confer resistance to trimethoprim with dfrA12 or dfrA17. Two such cassette arrays were embedded in simple integrons consisting of dfrA12-orfF-aadA2 (1.9 kb, n = 4, Figure 3I) and dfrA17-aadA5 (1.6 kb, n = 4, Figure 3III), while the other two were embedded in complex integrons carrying the IS26 element consisting of dfrA17-aadA5-IS26 (2.5 kb, n = 1, Figure 3IV) and dfrA12-orfF-ΔaadA2-IS26-ΔTn3-orf (4 kb, n = 7, Figure 3II). Array I and III in Figure 3 were popularly distributed in Salmonella (Li R. et al., 2013; Pérez-Moreno et al., 2013; Meng et al., 2017). Compared to Array I, aadA2 gene in Array II was truncated at the 578-bp from the 5′ CS by IS26, along with the insertion of a ΔTn3-orf fragment and partial deletion of the qacEΔ1 gene. Compared to Array III, reversely oriented IS26 inserted into the downstream of the aadA5 gene in Array IV without any disruption.

Figure 3. Genetic organization of different class 1 integrons. The orientation of each gene and insertion element is indicated by arrows.

Characterization of Complex IS26-Class 1 Integron Arrangements

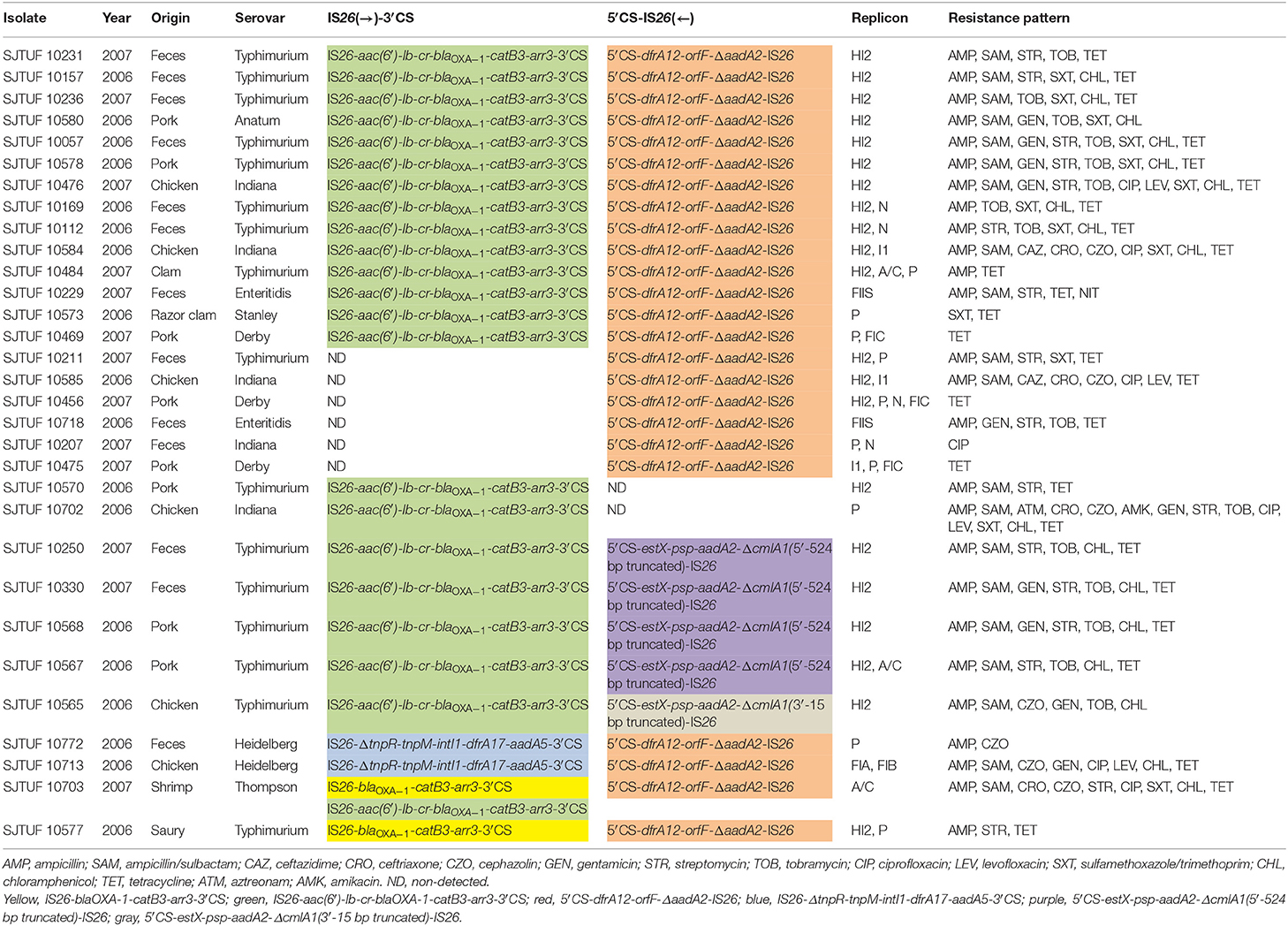

Toward the position relationship with IS26 inserted into the upstream of class 1 integrons, three different IS26-class 1 integron arrangements were characterized as follows: IS26-aac(6′)-Ib-cr-blaOXA−1-catB3-arr3-3′CS (3.5 kb, n = 22), IS26-blaOXA−1 -catB3-arr3-3′CS (2.8 kb, n = 2), and IS26-ΔtnpR-tnpM-intI1-dfrA17-aadA5-3′CS (4 kb, n = 2) [Table 2, IS26(→)-3′CS]. Toward the position relationship with IS26 inserted into the downstream of class 1 integrons, three different IS26-class 1 integron arrangements were also characterized as follows: 5′CS-dfrA12-orfF-ΔaadA2-IS26 (2.3 kb, n = 24), 5′CS-estX-psp-aadA2-ΔcmlA1(3′-15 bp truncated)-IS26 (4.3 kb, n = 1), and 5′CS-estX-psp-aadA2-ΔcmlA1(5′-524 bp truncated)-IS26 (3.5 kb, n = 4) [Table 2, 5′CS-IS26(←)]. Among the 37 antibiotic-resistant isolates, only 31 were positive for complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements mentioned above with eight different complex patterns shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns characterized in 31 antibiotic-resistant Salmonella isolates, including isolated year, sources, serovar, antibiotic resistance profiles, complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements as well as plasmid replicon types.

The genetic arrangement of IS26-aac(6′)-Ib-cr-blaOXA−1-catB3-arr3-3′CS was composite structure consisting of an IS26 element and a peculiar class 1 integron without 5′CS, which carrying aac(6′)-Ib-cr, blaOXA−1, catB3, arr3 gene cassettes, so conferring resistance to quinolone and aminoglycoside, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and rifampicin, respectively. The Pc promoter responsible for the expression of gene cassettes is located in the 5′CS region of the class 1 integron (Stalder et al., 2012). Interestingly, 17 of 22 isolates carrying this genetic arrangement exhibited antibiotic tolerance against ampicillin and chloramphenicol (Table 2, green), suggesting that IS26 achieved gene cassette expression through forming a suitable−10 box aided by−35 box in the IR of IS26 (Lee et al., 1990; Cain and Hall, 2011). In comparison, another genetic arrangement of IS26-blaOXA−1-catB3-arr3-3′CS was similar but lacking the aac(6′)-Ib-cr gene cassette (Table 2, yellow). Interestingly, S. Thompson isolate SJTUF 10703 harboring both IS26-aac(6′)-Ib-cr-blaOXA−1-catB3-arr3-3′CS and IS26-blaOXA−1-catB3-arr3-3′CS conferred resistance to 9 antibiotics. S. Typhimurium isolate SJTUF 10577 simultaneously harboring IS26-blaOXA−1 -catB3-arr3-3′CS and 5′CS-dfrA12-orfF-ΔaadA2-IS26 showed less antibiotic resistance than other S. Typhimurium isolates harboring IS26-aac(6′)-Ib-cr-blaOXA−1-catB3-arr3-3′CS and 5′CS-dfrA12-orfF-ΔaadA2-IS26, indicating that the emergence of IS26-aac(6′)-Ib-cr-blaOXA−1-catB3-arr3-3′CS may be the outcome of molecular evolution of IS26-blaOXA−1-catB3-arr3-3′CS under antibiotic pressure. Another novel composite structure was identified, consisting of an IS26 element and a peculiar Tn21 with tnpR gene (encoding resolvase) truncated by IS26 while an intact class 1 integron was embedded in Tn21 carrying the gene cassette array of dfrA17-aadA5 (Table 2, blue). This arrangement was only found in two S. Heidelberg isolates from feces and chicken, respectively. Dawes et al. (2010) also discovered a complex IS26-Tn21 module in E. coli. But in their findings, IS26 directly inserted into the downstream of the aadA5 gene cassette embedded in the class 1 integron, truncating the 3′CS and leaving functional genes of Tn21 intact.

The IS26-class 1 integron arrangements with the IS26 inserted into the downstream of class 1 integrons were all composite structures consisting of an IS26 element and a peculiar class 1 integron with gene cassettes interrupted. On the basis of sequence alignments, the prevalent arrangement of 5′CS-dfrA12-orfF-ΔaadA2-IS26 (Table 2, red) may originate from the typical class 1 integron with the array of intI1-dfrA12-orfF-aadA2-qacΔE-sulI or the sul3-type class 1 integron with the array of intI1-dfrA12-orfF-aadA2-cmlA1-aadA1-qacH-IS440-sul3 (Antunes et al., 2007), due to the insertion of IS26 at the 578-bp of the aadA2 gene cassettes from the 5′ end. Furthermore, The other two genetic arrangements of 5′CS-estX-psp-aadA2-ΔcmlA1-IS26 (Table 2, purple and gray) may both originate from the sul3-type class 1 integron carrying the gene cassette array of estX-psp-aadA2-cmlA1-aadA1 (Antunes et al., 2007), similarly due to the insertion of IS26 at different loci of the cmlA1 gene cassette (conferring resistance to chloramphenicol). Other studies also discovered the correlation between IS26 and sul3-type class 1 integrons with IS26 frequently inserted into the downstream of the qacH-sul3 domain, forming IS440-sul3-Δorf1-IS26 clusters (Curiao et al., 2011; Moran et al., 2016). These data pointed out the potential of IS26 to mediate horizontal transfer of sul3-type class 1 integrons.

Target site duplication (TSD) is the characteristic hallmark of transposition (He et al., 2015). However, 8-bp typical TSD (TTCTACGG) (Oliveira et al., 2013) of IS26 transposition didn't occur among complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements characterized in this study, which was also observed in some researches (Miriagou et al., 2005; Curiao et al., 2011; Hudson et al., 2014). Since IS26 transposes via a cointegrating mechanism, homologous recombination following IS26 transposition may cause DNA deletions or rearrangements, merely resulting in the generation of itself without flanking TSDs (He et al., 2015). In addition, IS26 in the Translocatable Unit (TU) targets an existing copy of IS26 and the TU will be incorporated immediately adjacent to it without increasing the number of IS26 copies or creating a duplication of the target (Harmer et al., 2014). Thus, further complete sequencing and analysis of representative plasmids harboring specific complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements may be required to better understand the molecular mechanism of IS26-class 1 integron-mediated MDR.

Eight complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns shown in Table 2 were distributed in 8 Salmonella serovars with the high prevalence of S. Typhimurium (51.6%, 16/31). And six complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns were distributed in the IncHI2-positive Salmonella isolates. S. Typhimurium is an important foodborne pathogen with a high prevalence of antimicrobial resistance (Torpdahl et al., 2013). All of S. Typhimurium isolates harboring complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements except one exhibited MDR phenotypes, inferring that composite IS26-class 1 integron elements may play a critical role in the acquisition and dissemination of antibiotic resistance as well as the environmental adaptation of S. Typhimurium. Moreover, S. Typhimurium isolates with the same complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement pattern showed similar antibiotic resistance profile, and vice versa (Table 2). The diversity of complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns may be useful as a marker in epidemiological studies of outbreak associated with S. Typhimurium that contain such elements, assisting in foodborne disease source-tracking and the antibiotic resistance surveillance.

Characterization of IncHI2 Plasmids and Localization of the Complex IS26-Class 1 Integron Arrangement on IncHI2 Plasmids

IncHI2 plasmids are responsible for carrying numerous classes of resistance genes and frequently detected among MDR Salmonella (Lai et al., 2013; Li L. et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014). IncHI2 was the dominant incompatibility group in this study and six complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns were distributed in 21 IncHI2-positive Salmonella isolates (Table 2). Thus, pDLST was performed to better characterize these IncHI2 plasmids. All IncHI2 plasmids were assigned to ST3 except one untypable IncHI2 plasmid in SJTUF 10456 due to a failure to detect the smr0199 locus (data not shown), suggesting the occurrence of a new variant after multiple recombination events (Campos et al., 2016).

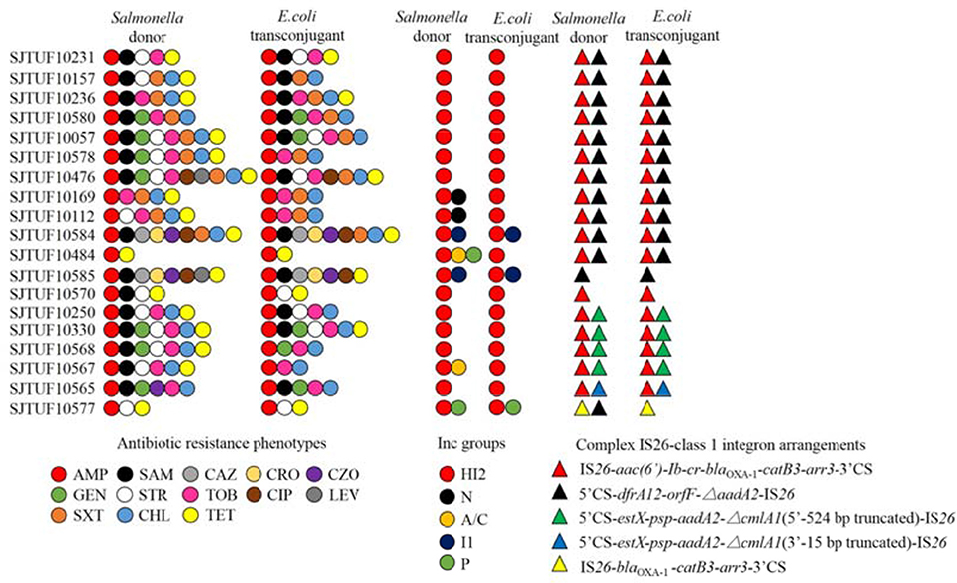

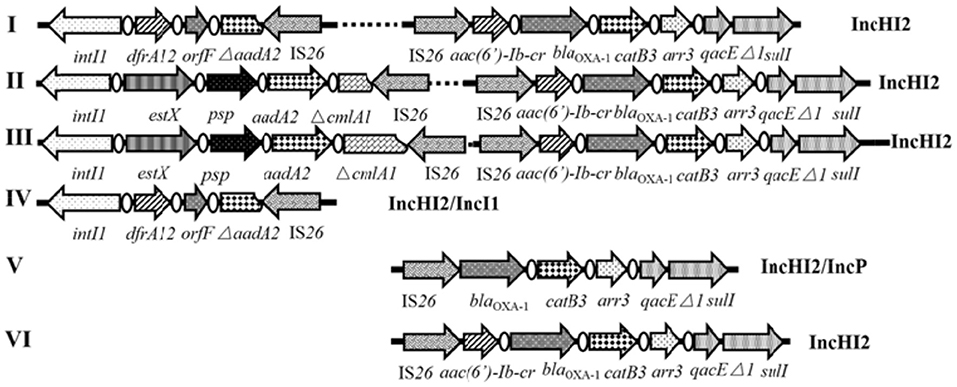

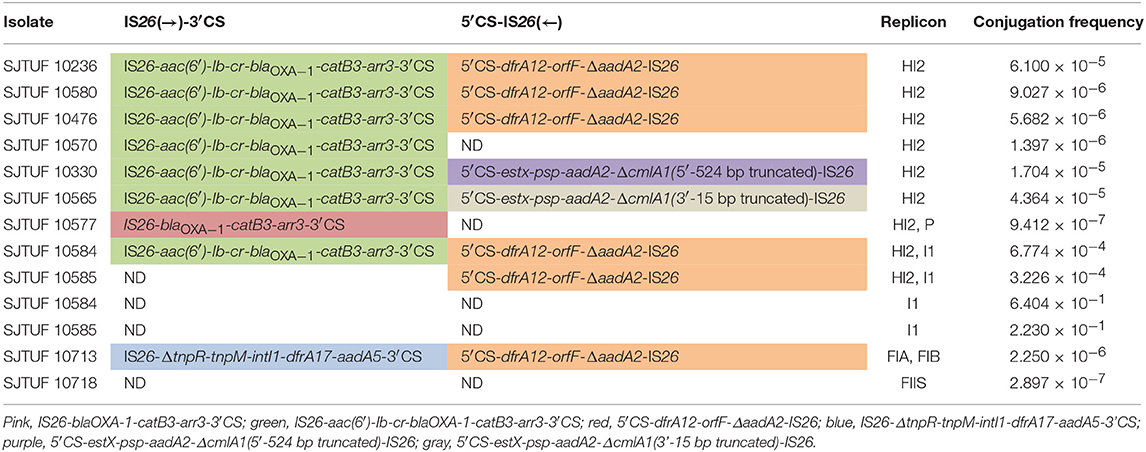

Twenty-one isolates both harboring IncHI2 plasmid and complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement were selected in the liquid mating assay to disclose their correlation. Nineteen transconjugants were obtained (Figure 4), and the conjugation rate was 90.5% (19/21). Based on the PCR-based replicon typing, IncHI2 plasmids from donors were all transferred to the E. coli rifampicin-resistant recipient with the co-transfer of IncI1 plasmids in SJTUF 10584 and SJTUF 10585 as well as IncP plasmid in SJTUF 10577. All of the detected complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements were also transferred to the recipient after conjugation experiment except the genetic arrangement of 5′CS-dfrA12-orfF-ΔaadA2-IS26 in SJTUF 10577. Six complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns associated with IncHI2 plasmids were further confirmed (Figures 4, 5) harboring 5 types of IS26-class 1 integron arrangements (corresponding to five probes I-V in Table 1). In addition, MDR phenotypes were also observed in the transconjugants, indicating that the majority of the MDR traits were determined by these ST3-IncHI2 plasmids. The conjugation frequencies of IncHI2 plasmids transferred alone were 10−5-10−6 (Table 3), reflecting that different complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns located on the IncHI2 plasmids didn't significantly affect conjugation frequencies (P > 0.05). IncHI2 and IncI1 plasmids were co-transferred with the conjugation frequencies of 10−4, reflecting that IncI1 plasmids could highly promote the co-transfer of IncHI2 plasmids.

Figure 4. Comparison of Salmonella donors and the corresponding E. coli transconjugants based on antibiotic resistance profiles, plasmid replicon types and complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns. The antibiotics listed are abbreviated as follows: AMP, ampicillin; SAM, ampicillin/sulbactam; CAZ, ceftazidime; CRO, ceftriaxone; CZO, cephazolin; GEN, gentamicin; STR, streptomycin; TOB, tobramycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; LEV, levofloxacin; SXT, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim; CHL, chloramphenicol; TET, tetracycline.

Figure 5. Schematic representation of IncHI2-associated complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns. The dotted lines imply omissions of the IncHI2 backbones. The orientation of each gene and insertion element is indicated by arrows.

Table 3. Conjugation frequencies of plasmids from eleven antibiotic-resistant Salmonella isolates and the resulting transferred plasmid incompatibility groups and complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements.

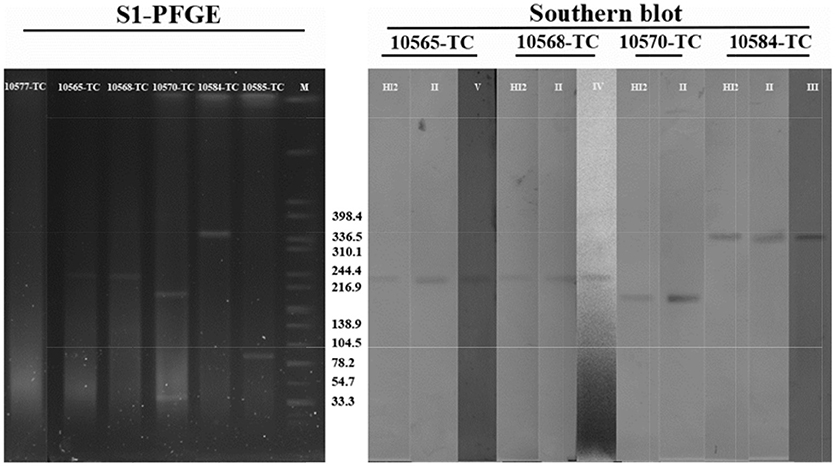

Six tranconjugants (SJTUF10565-TC, SJTUF10568-TC, SJTUF10570-TC, SJTUF10577-TC SJTUF 10584-TC, and SJTUF10585-TC) covering the six typical IncHI2-associated complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns were selected for the analysis of S1-PFGE and Southern blot to confirm the genome-independent existence of IncHI2 plasmids and the localization of IS26-class 1 integron arrangements on IncHI2 plasmids. It is expected that SJTUF10565-TC harbors pattern III (probes II and V), SJTUF10568-TC harbors pattern II (probes II and IV), SJTUF10570-TC harbors pattern VI (probe II), SJTUF10577-TC harbors pattern V (probe I), SJTUF 10584-TC harbors pattern I (probes II and III), and SJTUF10585-TC harbors pattern IV (probe III) as shown in Figures 4, 5 and Table 1.

S1-PFGE and subsequent Southern hybridization against DIG-labeled IncHI2 specific probes revealed that the size of IncHI2 plasmids in transconjugants with different IS26-class 1 integron arrangements ranged between 200 and 340 kb (Figure 6). It is noteworthy that there were no separated plasmids in SJTUF10577-TC which is inconsistent with previous PCR-based plasmid replicon typing results. This may be due to the nuclease degradation during S1 digestion or the plasmid integration into E. coli genome, which needs further study. There was only one plasmid in SJTUF 10584-TC and SJTUF10585-TC separated successfully by S1-PFGE, and the Southern blot confirmed only the plasmid in SJTUF 10584-TC belonged to IncHI2 group. The approximate 80-kb plasmid in SJTUF10585-TC possibly belonged to IncI1 group for that its size was in correspondence with the sequenced IncI1 plasmid (Tagg et al., 2014). Besides IncHI2 plasmid, there was one more untypable plasmid around 33 kb in SJTUF10570-TC. Therefore, except SJTUF 10577-TC and SJTUF 10585-TC, the four transconjugants SJTUF10565-TC, SJTUF10568-TC, SJTUF10570-TC, and SJTUF 10584-TC could be further involved in the Southern blot with different IS26-class 1 integron arrangement probes. As shown in Figure 6, the expected hybridization bands were displayed in all these four transconjugants with corresponding size of each IncHI2 plasmid. It could be concluded that the four IncHI2-associated complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns I-III, and VI (Figure 5) have been confirmed to locate on IncHI2 plasmids. Since SJTUF 10585-TC or SJTUF 10577-TC was the only transconjugant harboring IncHI2-associated complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement pattern IV or V, it was hard to prove the localization of the pattern IV or V on IncHI2 plasmids in this study. Further whole genome sequencing including plasmids may be needed.

Figure 6. PFGE of S1-digested transconjugants DNA and Southern blot hybridization with specific IS26-class 1 integron arrangement probes shown in Table 1. M, S. Braenderup H9812 universal size standard.

ST3-IncHI2 plasmids have been disseminated in multiple chicken and livestock farms of China, which are frequently associated with fosA3 and oqxAB flanking by IS26 (Yang et al., 2014; Fang et al., 2016; Wong et al., 2016). Despite of a recent study discovering the complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement pattern I(i.e., IS26-aac(6′)-Ib-cr-blaOXA−1-catB3-arr3-3′CS plus 5′CS-dfrA12-orfF-ΔaadA2-IS26) through whole genome sequencing in two ST3-IncHI2 plasmids (Wong et al., 2016), few studies have systematically reported the association between ST3-IncHI2 plasmids and complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements. The genetic arrangement of IS26-aac(6′)-Ib-cr-blaOXA−1-catB3-arr3-3′CS was the most popular IS26-class 1 integron arrangement identified in this study, with prevalent distribution in S. Typhimurium. The identical genetic context of the class 1 integron associated with IS26 on IncHI2 plasmids was also detected in S. Indiana in China (Lai et al., 2013) as well as S. Typhimurium in Europe (Campos et al., 2016), suggesting a similar evolutionary origin and highlighting the potentially global spread of IncHI2 plasmids among Salmonella. Furthermore, a similar genetic context of that was also identified on an IncR plasmid of a Klebsiella oxytoca strain in Spain (Ruiz et al., 2011), and an IncN plasmid of an E. coli isolate in Hong Kong (Ho et al., 2013). The similar genetic module infers that the transfer of composite IS26-class 1 integron element between different plasmid replicons was probably mediated by IS26 (Li L. et al., 2013; He et al., 2015). Moreover, the sul3-type class 1 integron with the array of intI1-dfrA12-orfF-aadA2-cmlA1-aadA1-qacH-IS440-sul3 has been identified on IncA/C, IncI1 and IncB/O plasmids (Curiao et al., 2011; García et al., 2011), but rarely on IncHI2 plasmids. Sequence alignments revealed that two genetic arrangements of 5′CS-estX-psp-aadA2-ΔcmlA1-IS26 identified on IncHI2 plasmids in this study may both originate from that sul3-type class 1 integron, indicating that IS26 plays an important role in the transfer of sul3-type class 1 integrons between different plasmid replicons as well as the diversity of complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements.

IncHI2 plasmids always show very conserved and stable scaffolds (García-Fernández and Carattoli, 2010), the formation of diverse complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements may be mediated by IS26 via a replicative mechanism or a TU element (Harmer et al., 2014; Harmer and Hall, 2015; He et al., 2015). The transposition activity of IS26 collaborates with capture and integration of class 1 integrons, resembling resistance gene clusters onto a single plasmid. IS26-mediated further fusion and reorganization of such plasmids will facilitate the occurrence of novel IncHI2 derivative plasmids with various MDR regions (He et al., 2015; Fang et al., 2016; García et al., 2016). In addition, gene cassettes embedded in atypical class 1 integrons with 5′CS or 3′CS interrupted by IS26 couldn't be screened by conventional PCR. Thus, the comprehensive study of complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements in Salmonella may provide a new perspective in tracing the spread and evolution of IS26-class 1 integron-mediated MDR as well as MDR IncHI2 plasmids.

The conjugation frequencies of IncHI2 plasmids transferred alone at 37°C ranged from 10−5 to 10−6 (Table 3), and different complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangement patterns located on the IncHI2 plasmids didn't significantly affect conjugation frequencies (P > 0.05), inferring that conjugation frequency may mainly depend on the mutual regulation by transfer-related functional elements located on the plasmid (Page et al., 1999; Gruber et al., 2016). The conjugation frequency of IncI1 plasmids transferred alone was 10−1, and then became 10−4 while co-transfer with IncHI2 plasmids, reflecting that highly conjugative plasmids could promote the movement of other plasmids. García et al. (2007) found that the conjugation frequency of IncHI2 plasmids transferred together with IncF plasmids increased two orders of magnitude than that of IncHI2 plasmids transferred alone, attributing to the formation of cointegrate FIB–HI2 plasmid fusion during transfer process. Whether IncI1 plasmids promoted the transfer of IncHI2 plasmids through a similar mechanism may need further study. IncHI2 plasmids belonging to broad-host-range plasmid vectors contain several functional elements to ensure their stable permanence in host, such as the mutagenesis induction system (mucAB), the relE/relB toxin–antitoxin system and bacteriophage inhibition (phi) (García-Fernández and Carattoli, 2010). Meanwhile, IncHI2 plasmids exhibit optimal transfer capacity at low temperature (<30°C), along with co-transfer driven by highly conjugative plasmids like IncI1 plasmids, will facilitate the dissemination of composite IS26-class 1 integron MDR elements among various bacterial species. Thus, increased active surveillance of the MDR IncHI2 plasmids carrying such composite IS26-class 1 integron elements in Salmonella is urgently needed.

In conclusion, class 1 integrons represent the hot spot for IS26 insertion, and IS26 can insert into class 1 integrons at different sites, forming diverse MDR loci. Moreover, ST3-IncHI2 was the major plasmid lineage contributing to the horizontal transfer of composite IS26-class 1 integron MDR elements. Further investigation of complex IS26-class 1 integron arrangements is urgently needed to track and monitor the spread of IS26-class 1 integron-mediated antibiotic resistance as well as the evolution of IncHI2 MDR plasmids.

Author Contributions

HZ completed the screening of IS26-positive isolates, detection of Class 1 integrons, genetic context analysis of Class 1 integrons associated with IS26, conjugation experiments, and IncHI2 plasmid characterization. WC completed the isolate collection, antimicrobial susceptibility test, screening of IS26-positiveisolates, and detection of Class 1 integrons. XX helped to finish the isolate collection. XZ helped to finish the isolate collection, antimicrobial susceptibility test, and data release. CS designed the project, completed the data analysis, and prepared the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (grant number 2017YFC1600100), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 31671943 and 31601562).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02492/full#supplementary-material

References

Abraham, S., Groves, M. D., Trott, D. J., Chapman, T. A., Turner, B., Hornitzky, M., et al. (2014). Salmonella enterica isolated from infections in Australian livestock remain susceptible to critical antimicrobials. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 43, 126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.10.014

Antunes, P., Machado, J., and Peixe, L. (2007). Dissemination of sul3-containing elements linked to class 1 integrons with an unusual 3′ conserved sequence region among Salmonella isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 1545–1548. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01275-06

Brown-Jaque, M., Calero-Cáceres, W., and Muniesa, M. (2015). Transfer of antibiotic-resistance genes via phage-related mobile elements. Plasmid 79, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2015.01.001

Cain, A. K., and Hall, R. M. (2011). Transposon Tn5393e carrying the aphA1-containing transposon Tn6023 upstream of strAB does not confer resistance to streptomycin. Microb. Drug Resist. 17, 389–394. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2011.0037

Campos, J., Mourão, J., Marçal, S., Machado, J., Novais, C., Peixe, L., et al. (2016). Clinical Salmonella Typhimurium ST34 with metal tolerance genes and an IncHI2 plasmid carrying oqxAB-aac(6′)-Ib-cr from Europe. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71, 843–845. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv409

Chen, T. L., Lee, Y. T., Kuo, S. C., Hsueh, P. R., Chang, F. Y., Siu, L. K., et al. (2010). Emergence and distribution of plasmids bearing the blaOXA-51-like gene with an upstream ISAba1 in carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in Taiwan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4575–4581. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00764-10

Chen, W., Fang, T., Zhou, X., Zhang, D., Shi, X., and Shi, C. (2016). IncHI2 plasmids are predominant in antibiotic-resistant Salmonella isolates. Front. Microbiol. 7:1566. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01566

CLSI (2013). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Tweenty-third Informational Supplement M100-S23. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

Curiao, T., Cantón, R., Garcillán-Barcia, M. P., de la Cruz, F., Baquero, F., and Coque, T. M. (2011). Association of composite IS26-sul3 elements with highly transmissible IncI1 plasmids in extended-spectrum-β-Lactamase-producing Escherichia coli clones from humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 2451–2457. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01448-10

Dang, B., Mao, D., and Luo, Y. (2016). Complete nucleotide sequence of IncP-1β plasmid pDTC28 reveals a non-functional variant of the blaGES-type gene. PLoS ONE 11:e0154975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154975

Dawes, F. E., Kuzevski, A., Bettelheim, K. A., Hornitzky, M. A., Djordjevic, S. P., and Walker, M. J. (2010). Distribution of class 1 integrons with IS26-mediated deletions in their 3′-conserved segments in Escherichia coli of human and animal origin. PLoS ONE 5:e12754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012754

Deng, Y., Bao, X., Ji, L., Chen, L., Liu, J., Miao, J., et al. (2015). Resistance integrons: class 1, 2 and 3 integrons. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 14:45. doi: 10.1186/s12941-015-0100-6

Dierikx, C., van Essen-Zandbergen, A., Veldman, K., Smith, H., and Mevius, D. (2010). Increased detection of extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Salmonella enterica, and Escherichia coli, isolates from poultry. Vet. Microbiol. 145, 273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.03.019

Fang, L., Li, X., Li, L., Li, S., Liao, X., Sun, J., et al. (2016). Co-spread of metal and antibiotic resistance within ST3-IncHI2 plasmids from E. coli isolates of food-producing animals. Sci. Rep. 6:25312. doi: 10.1038/srep25312

Folster, J. P., Campbell, D., Grass, J., Brown, A. C., Bicknese, A., Tolar, B., et al. (2015). Identification and characterization of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Albert isolates in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 2774–2779. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05183-14

García, A., Navarro, F., Miró, E., Villa, L., Mirelis, B., Coll, P., et al. (2007). Acquisition and diffusion of blaCTX−M−9 gene by R478-IncHI2 derivative plasmids. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 271, 71–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00695.x

García, P., Guerra, B., Bances, M., Mendoza, M. C., and Rodicio, M. R. (2011). IncA/C plasmids mediate antimicrobial resistance linked to virulence genes in the Spanish clone of the emerging Salmonella enterica serotype 4,[5],12:i:–. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66, 543–549. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq481

García, V., García, P., Rodríguez, I., Rodicio, R., and Rodicio, M. R. (2016). The role of IS26 in evolution of a derivative of the virulence plasmid of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis which confers multiple drug resistance. Infect. Genet. Evol. 45, 246–249. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.09.008

García-Fernández, A., and Carattoli, A. (2010). Plasmid double locus sequence typing for IncHI2 plasmids, a subtyping scheme for the characterization of IncHI2 plasmids carrying extended-spectrum β-lactamase and quinolone resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65, 1155–1161. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq101

Gruber, C. J., Lang, S., Rajendra, V. K. H., Nuk, M., Raffl, S., Schildbach, J. F., et al. (2016). Conjugative DNA transfer is enhanced by plasmid R1 partitioning proteins. Front. Mol. Biosci. 3:32. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2016.00032

Harmer, C. J., and Hall, R. M. (2015). IS26-Mediated precise excision of the IS26-aphA1a translocatable unit. mBio 6:e01866–e01815. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01866-15

Harmer, C. J., Moran, R. A., and Hall, R. M. (2014). Movement of IS26-associated antibiotic resistance genes occurs via a translocatable unit that includes a single IS26 and preferentially inserts adjacent to another IS26. mBio 5:e01801–01814. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01801-14

He, S., Hickman, A. B., Varani, A. M., Siguier, P., Chandler, M., Dekker, J. P., et al. (2015). Insertion sequence IS26 reorganizes plasmids in clinically isolated multidrug-resistant bacteria by replicative transposition. mBio 6:e00762–e00715. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00762-15

Ho, P.-L., Chan, J., Lo, W.-U., Lai, E. L., Cheung, Y.-Y., Lau, T. C. K., et al. (2013). Prevalence and molecular epidemiology of plasmid-mediated fosfomycin resistance genes among blood and urinary Escherichia coli isolates. J. Med. Microbiol. 62, 1707–1713. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.062653-0

Hudson, C. M., Bent, Z. W., Meagher, R. J., and Williams, K. P. (2014). Resistance determinants and mobile genetic elements of an NDM-1-encoding Klebsiella pneumoniae strain. PLoS ONE 9:e99209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099209

Hunter, S. B., Vauterin, P., Lambert-Fair, M. A., van Duyne, M. S., Kubota, K., Graves, L., et al. (2005). Establishment of a universal size standard strain for use with the PulseNet standardized pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols: converting the national databases to the new size standard. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 1045–1050. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1045-1050.2005

Lai, J., Wang, Y., Shen, J., Li, R., Han, J., Foley, S. L., et al. (2013). Unique class 1 integron and multiple resistance genes co-located on IncHI2 plasmid is associated with the emerging multidrug resistance of Salmonella Indiana isolated from chicken in China. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 10, 581–588. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2012.1455

Lee, K. Y., Hopkins, J. D., and Syvanen, M. (1990). Direct involvement of IS26 in an antibiotic resistance operon. J. Bacteriol. 172, 3229–3236. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3229-3236.1990

Li, L., Liao, X., Yang, Y., Sun, J., Li, L., Liu, B., et al. (2013). Spread of oqxAB in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium predominantly by IncHI2 plasmids. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68, 2263–2268. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt209

Li, L., Liao, X. P., Liu, Z. Z., Huang, T., Li, X., Sun, J., et al. (2014). Co-spread of oqxAB and blaCTX−M−9G in non-Typhi Salmonella enterica isolates mediated by ST2-IncHI2 plasmids. Int. J. Antimicro. Agents 44, 263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.05.014

Li, R., Lai, J., Wang, Y., Liu, S., Li, Y., Liu, K., et al. (2013). Prevalence and characterization of Salmonella species isolated from pigs, ducks and chickens in Sichuan Province, China. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 163, 14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.01.020

Meng, X., Zhang, Z., Li, K., Wang, Y., Xia, X., Wang, X., et al. (2017). Antibiotic susceptibility and molecular screening of class i integron in Salmonella isolates recovered from retail raw chicken carcasses in China. Microb. Drug Resist. 23, 230–235. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2015.0359

Miriagou, V., Carattoli, A., Tzelepi, E., Villa, L., and Tzouvelekis, L. S. (2005). IS26-associated In4-Type integrons forming multiresistance loci in Enterobacterial plasmids. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 3541–3543. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3541-3543.2005

Moran, R. A., Holt, K. E., and Hall, R. M. (2016). pCERC3 from a commensal ST95 Escherichia coli: a ColV virulence-multiresistance plasmid carrying a sul3-associated class 1 integron. Plasmid 84–85, 11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2016.02.002

Oliveira, C. S., Moura, A., Henriques, I., Brown, C. J., Rogers, L. M., Top, E. M., et al. (2013). Comparative genomics of IncP-1ε plasmids from water environments reveals diverse and unique accessory genetic elements. Plasmid 70, 412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2013.06.002

Page, D. T., Whelan, K. F., and Colleran, E. (1999). Mapping studies and genetic analysis of transfer genes of the multi-resistant IncHI2 plasmid, R478. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 179, 21–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08702.x

Pérez-Moreno, M. O., Picó-Plana, E., de Toro, M., Grande-Armas, J., Quiles-Fortuny, V., Pons, M. J., et al. (2013). β-Lactamases, transferable quinolone resistance determinants, and class 1 integron-mediated antimicrobial resistance in human clinical Salmonella enterica isolates of non-Typhimurium serotypes. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 303, 25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2012.11.003

Povilonis, J., Šeputiene, V., RuŽauskas, M., ŠiugŽdiniene, R., Virgailis, M., Pavilonis, A., et al. (2010). Transferable class 1 and 2 integrons in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica isolates of human and animal origin in Lithuania. Foodborne pathog. dis. 7, 1185–1192. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0536

Rodríguezmartínez, J. M., Díaz de Alba, P., Briales, A., Machuca, J., Lossa, M., Fernándezcuenca, F., et al. (2013). Contribution of OqxAB efflux pumps to quinolone resistance in extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68, 68–73. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks377

Ruiz, E., Rezusta, A., Sáenz, Y., Rocha-Gracia, R., Vinué, L., Vindel, A., et al. (2011). New genetic environments of aac (6′)-Ib-cr gene in a multiresistant Klebsiella oxytoca strain causing an outbreak in a pediatric intensive care unit. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 69, 236–238. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.09.004

Siguier, P., Gourbeyre, E., and Chandler, M. (2014). Bacterial insertion sequences: their genomic impact and diversity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 38, 865–891. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12067

Stalder, T., Barraud, O., Casellas, M., Dagot, C., and Ploy, M.-C. (2012). Integron involvement in environmental spread of antibiotic resistance. Front. Microbiol. 3:119. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00119

Sunde, M., Simonsen, G. S., Slettemeås, J. S., Böckerman, I., and Norström, M. (2015). Integron, plasmid and host strain characteristics of Escherichia coli from humans and food included in the Norwegian Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring Programs. PLoS ONE 10:e0128797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128797

Tadesse, D. A., Singh, A., Zhao, S., Bartholomew, M., Womack, N., Ayers, S., et al. (2016). Antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella in the United States from 1948 to 1995. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 2567–2571. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02536-15

Tagg, K. A., Iredell, J. R., and Partridge, S. R. (2014). Complete sequencing of IncI1 sequence type 2 plasmid pJIE512b indicates mobilization of blaCMY-2 from an IncA/C plasmid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 4949–4952. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02773-14

Torpdahl, M., Lauderdale, T.-L., Liang, S.-Y., Li, I., Wei, S.-H., and Chiou, C.-S. (2013). Human isolates of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium from Taiwan displayed significantly higher levels of antimicrobial resistance than those from Denmark. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 161, 69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.11.022

Wong, M. H.-y., Chan, E. W.-c., Xie, L., Li, R., and Chen, S. (2016). IncHI2 Plasmids are the key vectors responsible for oqxAB transmission among Salmonella species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 6911–6915. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01555-16

Yang, X., Huang, J., Wu, Q., Zhang, J., Liu, S., Guo, W., et al. (2016). Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance and genetic diversity of Salmonella isolated from retail ready-to-eat foods in China. Food Control 60, 50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.07.019

Keywords: Salmonella, IS26, class 1 integron, multidrug resistance, IncHI2

Citation: Zhao H, Chen W, Xu X, Zhou X and Shi C (2018) Transmissible ST3-IncHI2 Plasmids Are Predominant Carriers of Diverse Complex IS26-Class 1 Integron Arrangements in Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella. Front. Microbiol. 9:2492. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02492

Received: 18 April 2018; Accepted: 28 September 2018;

Published: 23 October 2018.

Edited by:

Miklos Fuzi, Semmelweis University, HungaryReviewed by:

Benoit Doublet, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA), FranceBidur P. Chaulagain, Chosun University, South Korea

Copyright © 2018 Zhao, Chen, Xu, Zhou and Shi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunlei Shi, Y2xzaGlAc2p0dS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Hang Zhao

Hang Zhao Wenyao Chen

Wenyao Chen Xuebin Xu2

Xuebin Xu2 Xiujuan Zhou

Xiujuan Zhou Chunlei Shi

Chunlei Shi