- 1Centre for Applied Cross-Cultural Research, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand

- 2International Recruitment, Relations and Study Abroad, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Social Psychology, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Cross-cultural transitions are challenging and often have detrimental consequences for psychological well-being. This is particularly true for international students at tertiary institutions who are not only transitioning between school and higher education, but also between vastly different educational systems. This study tests a predictive model of psychological adaptation with international students whereby host national connectedness mediates the effects of personal resources and contextual factors on adaptive outcomes. A sample (N = 1527) of international tertiary students in New Zealand completed a survey that measured self-reported English language proficiency, perceived cultural distance, perceived cultural inclusiveness in the classroom, host national connectedness (defined by frequency of contact, number of friends, social support, and general belongingness), and positive (life satisfaction) and negative (psychological symptoms) indicators of psychological adaptation. Path analysis indicated that host national connectedness fully mediated the effects of English language proficiency on psychological symptoms and partially mediated the effects of language proficiency, cultural distance and cultural inclusion in the classroom on life satisfaction and psychological symptoms. The findings highlight the importance of international students’ relationships with host nationals, and the results are discussed in relation to strategies that could enhance student-host connectedness during cross-cultural transitions.

Introduction

Cross-cultural transitions can be very challenging. Individuals are called upon to learn new skills to operate effectively in an unfamiliar cultural environment, to resolve tensions between differing cultural perspectives and worldviews, and to manage the stresses associated with significant changes in daily life (Ward and Szabó, 2019). In addition, it is critical that individuals establish and maintain social support networks that enhance resources for meeting these demands. While cross-cultural transition can take its toll on psychological well-being in general, the impact of these pressures is greater in some groups than others. For international students crossing cultures can be particularly stressful given the simultaneous occurrence of multiple transitions. Beyond crossing national and cultural boundaries, they may also experience normative developmental transitions from school to university and non-normative transitions between educational systems based on different values and assumptions (Lun et al., 2010; McGhie, 2017). When multiple transitions such as these occur simultaneously, there is a high probability that subjective well-being will be compromised, particularly if the transitions involve associated stressors such as discrimination (Hanassab, 2006; Lee and Rice, 2007), financial vulnerability (Li and Kaye, 1998; Sawir et al., 2012) and practical problems in daily living, such as securing appropriate accommodation (Bradley, 2000; Sawir et al., 2008). This paper examines the psychological well-being of international students during cross-cultural transition, highlighting the role of host national connectedness (HNC) in fostering positive outcomes.

The study is grounded in psychological theory and research on acculturation (changes in an individual’s psychological characteristics and behavioral patterns that arise from sustained intercultural contact) and adaptation (i.e., “feeling well”/psychological adaptation, “doing well”/sociocultural adaptation, and “relating well”/intercultural adaptation) as articulated by Berry and Sam (2016). The over-arching theoretical framework highlights the importance of both individual and contextual factors in shaping the acculturation process and its adaptive (or maladaptive) outcomes (also see Ward and Szabó, 2019). We are particularly interested in the dynamic role of contextual factors for two reasons. First, in terms of theory development, contextual factors have been relatively under-researched compared to individual differences such as personality, motivation, and attitudes. Second, in terms of application, schools and universities have educational and pastoral responsibilities; contextual factors are malleable, and policies and practices can be changed in ways that are more conducive to positive outcomes for international students.

Host National Connectedness

Connectedness has been conceptualized and measured in a myriad of ways. Both objective measures such as the number of friends and frequency of contact (e.g., Bochner et al., 1985; Ward and Searle, 1991; Hendrickson et al., 2011) and subjective assessments, like feelings of belongingness or social support, that capture the more intimate nature of connectedness (Rajapaksa and Dundes, 2002–2003; Ong and Ward, 2005) have been used. At its core connectedness refers to ties among people that foster a sense of belonging and diminish feelings of aloneness (Barber et al., 2005). Moreover, connectedness has been shown to predict international student success during cross-cultural transitions (Yeh and Inose, 2003; Sümer et al., 2008).

International students form multiple connections as they settle into their new academic environments, and all of these have the potential to offer social support and bolster well-being. In terms of student peers, connections occur across three primary groups: host nationals (native-borns), co-nationals (compatriots), and multi-nationals (international students from other national backgrounds), although technological advances have also made retaining home country peer support much easier (Bochner et al., 1977; Bochner, 2006; Lin et al., 2012; Li and Chen, 2014). It has been suggested that each of these friendship networks offers different resources, with co-nationals largely providing emotional support and host nationals offering functional or instrumental assistance (Bochner et al., 1977); however, more recent research has shown that a higher ratio of host national individuals in international students’ social networks is associated with their greater satisfaction and contentment (Hendrickson et al., 2011). More broadly, host national connectedness has been shown to attenuate the negative effects of the educational and cultural stressors that international students encounter during their transitions (Kashima and Loh, 2006; Zhang and Goodson, 2011; Cheung and Yue, 2013). It is also linked to higher levels of satisfaction with the international student experience (Rohrlich and Martin, 1991) as well as lower levels of homesickness and social isolation (Ying and Han, 2006; Hendrickson et al., 2011).

Despite the benefits that host national connectedness brings, international students find it difficult to cultivate friendships with local students (Zheng and Berry, 1991). A 2012 Australian national survey indicated that 86% of international students would like to have more Australian friends (Australian Education and International, 2013). Similarly, in a New Zealand national survey, Ward and Masgoret (2004) reported that 70% of international students desired to have more local friends. Indeed, not only international students, but researchers, educators, administrators, and counselors have identified low levels of intercultural engagement between international students and their domestic peers as one of the most significant challenges in international education (Bethel et al., 2016). Therefore, it is useful to examine the antecedents of host national connectedness in international students. In the next section we review key factors that predict HNC and describe how HNC might mediate their effects on psychological well-being in international students.

Antecedents and Outcomes of Host National Connectedness

As with most phenomena, the factors that predict HNC include individual differences as well as situational and contextual factors. Among individual differences language proficiency has been shown to be a strong predictor of connectedness with host nationals (Church, 1982; Masgoret and Gardner, 1999; Poyrazli et al., 2002). Conversely, a low level of language fluency inhibits the formation of intercultural relations (Peacock and Harrison, 2009; Gareis, 2012; Yu and Moskal, 2019). Language proficiency has also been associated with better psychological well-being in international students (Poyrazli et al., 2004; Dao et al., 2007; Cetinkaya-Yildiz et al., 2011). Cao and Meng (2019) integrated these findings in their mediational model of international student adaptation demonstrating that host national connectedness partially mediated the positive effects of language proficiency on adaptive outcomes. Similarly, we hypothesize that English language proficiency will exert both direct and indirect effects on the psychological adaptation of international students with the indirect effects mediated by host national connectedness.

While international students play an active role in their cross-cultural adaptation, there are situational and institutional factors that also come into play. The extent to which international students’ bond with their domestic peers as well as their adaptation outcomes are affected by the degree to which the international students’ heritage culture differs from their destination culture. This is referred to as cultural distance (Babiker et al., 1980). Early work by Furnham and Bochner (1982) demonstrated that international students in the United Kingdom who originated from high cultural distance countries had more social difficulties relating to British students in terms of everyday activities such as making British friends. More recent research has drawn similar conclusions (Fritz et al., 2008). High cultural distance is likely to lead to parallel lives for international and domestic students partly because having less in common results in fewer bonding opportunities (Montgomery, 2010; Bethel et al., 2016). In addition to the association between cultural distance and lower levels of social connectedness, cultural distance is known to predict negative psychological outcomes for international students (Galchenko and van de Vijver, 2007), including greater anxiety (Fritz et al., 2008) and mood disturbance (Ward and Searle, 1991) and lower levels of life satisfaction (Sam, 2001). Accordingly, we predict that the detrimental effects of cultural distance on international students’ well-being will be partially mediated by host national connectedness.

Diversity climates in educational institutions can influence the experiences and outcomes of cross-cultural transitions (Stuart and Ward, 2015). More specifically, diversity climates are known to affect both social connectedness and the psychological adaptation of students from minority backgrounds (Schachner et al., 2015, 2019; Titzmann et al., 2015) including international students (Ward and Masgoret, 2004). Culturally plural and inclusive climates enhance a sense of school belongingness, which leads, in turn, to greater life satisfaction (Schachner et al., 2019). Along similar lines, multicultural classrooms that reflect an appreciation of cultural diversity increase empathy and comfort with peers from different cultural backgrounds, and these positive relationships contribute to greater subjective happiness (Le et al., 2009). Therefore, we hypothesize that cultural inclusiveness in the classroom will predict greater host national connectedness, and host national connectedness will partially mediate the positive effects of inclusiveness on the psychological adaptation of international students.

Finally, personal background factors such as age, gender, and length of residence in the destination country can relate to international students’ connectedness with their domestic peers and their overall level of psychological adaptation; however, the research findings on these demographic factors are so inconsistent that it is impossible to derive well-grounded hypotheses. Studies have shown that: older international students have more local friends (Hendrickson, 2016), but younger students have more contact with their domestic peers (Ward and Masgoret, 2004); females are more likely to have meaningful relationships with host nationals (Yang et al., 1994), but males report having more host national friends (Ward and Masgoret, 2004); and relationships between international and domestic students grow during study abroad (Hernández-Nanclares, 2016), but interaction between them decreases over time (Rienties and Nolan, 2014). The associations among these demographic characteristics and the psychological adaptation of international students are likewise highly variable. Females have been shown to experience both higher levels of well-being and more symptoms of anxiety and depression (Bulgan and Çiftçi, 2017; Alharbi and Smith, 2018). Age and length of residence in the destination country have been both positively and negatively associated with psychological adaptation (Ying and Liese, 1994; Wilton and Constantine, 2003; Alharbi and Smith, 2018; Yang et al., 2018). These mixed findings are not surprising as age ranges and length of residence can vary enormously across studies, and how connectedness and well-being play out during cross-cultural transition are also affected by the way in which constructs are measured and the characteristics of the international student sample, educational institutions and national context (Ward and Masgoret, 2004; Le et al., 2009; Geeraert et al., 2019; Schachner et al., 2019). Consequently, we explore the direct and indirect of effects of demographic factors (gender, age, and length of residence) on the psychological adaptation of international students rather than testing specific hypotheses.

In summary, this study tests a mediational model whereby host national connectedness partially mediates the effects of demographic factors, English language proficiency, perceived cultural distance and perceived cultural inclusiveness in the classroom on the psychological adaptation of international students.

Methods and Measurements

Participants and Procedures

With the support of a New Zealand government agency, an email invitation to participate in an online survey was sent to 23,205 international students studying in tertiary and private training institutions. Of the 23,205 international students invited to participate, 2,823 (12.17%) responded. We eliminated those who indicated they were not international students, no longer studying or had not yet arrived in New Zealand. We also eliminated those who had missing responses to all items on an adaptation outcome variable; this left us with an adjusted response/inclusion rate of 6.58%.

The final sample was made up of 1527 participants (56.7% male) whose ages ranged from 17 to 62 years old (M = 26.68, SD = 6.01). Students originated from 78 countries, with the highest proportions from India (27.2%), the Philippines (9.9%), and China (9.3%). At the time of the survey, participants had lived in New Zealand on average for just over 1 year (M = 15.74 months, SD = 8.40). All students had been in New Zealand for less than five years.

Measures

In addition to demographic information (gender, age, country of origin and length of time in New Zealand), we measured self-reported English language proficiency, perceived cultural distance, perceived cultural inclusion in their educational environment, host national connectedness and positive and negative indicators of psychological adaptation.

English Language Proficiency

Four self-rated items were used to assess participants’ English language proficiency. In line with the most common conventions, participants rated their proficiency in reading, writing, speaking, and comprehension on a scale from very poor (1) to excellent (6), with a rating of 7 for native speakers (Li et al., 2006; Tomoschuk et al., 2019). We combined the four items for an overall proficiency score, as is typically done in acculturation research (e.g., Sam et al., 2015; Doucerain et al., 2017) so that higher scores indicate greater language proficiency (Cronbach’s α = 0.94).

Cultural Distance

A 10-item scale adapted from Babiker et al. (1980) was used to evaluate the perceived level of cultural distance between the participants’ country of origin and New Zealand. The instructions read “Please rate how much, if at all, your own background differs from that of New Zealand in the following areas,” and items included areas such as climate, food, and religion (Searle and Ward, 1990). Responses are measured on a 4-point scale, from not different (1) to very different (4), with higher scores reflecting greater cultural distance. The measure demonstrated an acceptable level of reliability in this study (α = 0.85).

Perceived Cultural Inclusion

To measure perceived cultural inclusion, a 7-item Cultural Inclusiveness in the Classroom Scale (CICS; Ward and Masgoret, 2004) was used. Sample items include “Cultural differences are respected in my institution,” and “My lecturers encourage contact between international and local students.” Participants responded on a 5-point Likert Scale, strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) so that higher scores reflect greater inclusiveness (α = 0.87).

Host National Connectedness

Given the complexity of the definition of connectedness, multiple measures were needed to capture the intricacy of HNC. We aimed to combine both objective and subjective elements of host national connectedness, where connectedness is conceptualized as a complex, higher-order construct identified by key psychological (e.g., Ong and Ward, 2005) and contextual (e.g., Bochner et al., 1985) indicators known from previous research. Hence, measures tapping the quantity and frequency of host national connections, feelings of connectedness, and support provided by host nationals were used. To measure the number and frequency of host national friends and interactions, ten items (i.e., “Indicate how many close friends you have who are New Zealanders outside of your educational institution,” and “How often do you spend free time outside of class with New Zealand students?”) were adapted from Ward and Masgoret’s (2004) national survey of international students in New Zealand. Responses are given on five-point scales: none (1) to many (5) and never (1) to very often (5). Separate mean scale scores were calculated for the two number-of-friends items (Spearman–Brown = 0.59) and for the eight frequency-of-contact items (α = 0.88).

Feelings of connectedness were measured with the General Belongingness Scale (Malone et al., 2012). Participants are instructed to think about their relationships with host nationals when responding to the 12-item scale with statements such as “When I am with other people, I feel included,” on a 7-point Likert Scale, strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). Higher overall scores indicate a greater sense of belonging. The measure met the standard reliability criterion (α = 0.81) in this study.

Finally, the instructions for the 18-item Index of Sojourner Social Support Scale (Ong and Ward, 2005) were adapted to measure the support that host nationals provide to international students. For example, participants are asked to respond to statements such as, “Think about your relationships with New Zealanders. Indicate how many New Zealanders you know who would listen and talk with you whenever you feel lonely or depressed.” The items measure the number of host nationals available to international students in a variety of situations on a five-point scale, no one (1) to many (5) with higher scores denoting higher levels of social support from host nationals. In this study, the scale demonstrated a high level of reliability (α = 0.98).

Psychological Adaptation

To measure psychological adaptation both positive (life satisfaction) and negative (psychological symptoms) indicators were used. The Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985) uses an agreement scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) in response to statements such as “In most ways my life is close to my ideal” and “The conditions of my life are excellent.” Higher scores signify greater life satisfaction. In this study, the scale had a reliability of α = 0.88.

Finally, we used the 15-item psychological symptoms scale (α = 0.93) from a multi-national study of immigrant youth by Berry et al. (2006). The scale asks participants to indicate how often in the last month they had experienced a list of symptoms, particularly depression, anxiety, and psychosomatic complaints, e.g., “I feel unhappy and sad;” “I worry a lot of the time;” and “I feel weak all over.” Responses were measured on a five-point scale, from never (1) to most of the time (5). Higher scores indicate greater frequency of psychological disturbances. The scale had high reliability in this study; Cronbach’s α = 0.93

Results

The results are presented in three parts: (1) the preliminary analyses, including the psychometric properties of the scales and bivariate correlations; (2) a confirmatory factor analysis for the construction of the HNC variable; and (3) a mediational model of psychological adaptation.

Preliminary Analyses

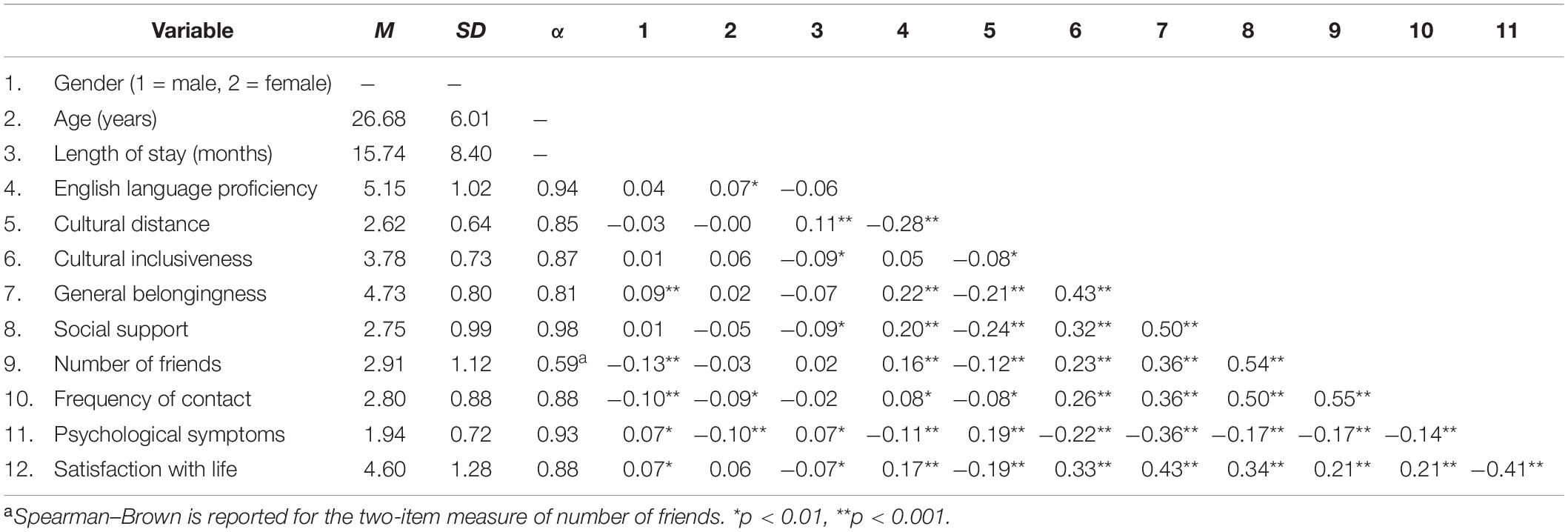

Table 1 provides the scale reliabilities, mean scores, and standard deviations for the measurement scales. With respect to host national connectedness, it is noteworthy that mean scores for both the number of host friends (M = 2.91, SD = 1.12, where 2 = one friend and 3 = a few) and the frequency of contact with host nationals (M = 2.80, SD = 0.88, where 2 = seldom and 3 = sometimes) were below the scalar midpoint (i.e., 3 on 5-point scales). A similar pattern emerged for social support (M = 2.75, SD = 0.99), suggesting that connectedness to host nationals may be a struggle for international students even though the findings for belongingness were more positive (M = 4.73, SD = 0.80).

Table 1 also reports the bivariate correlations among variables. The findings show that the four indicators of host national connectedness (number of local friends, frequency of contact with New Zealanders, social support and belongingness) were significantly inter-related, with medium to large effect sizes. Each indicator was also associated with life satisfaction and psychological symptoms in the expected direction although in these cases the effect sizes were small to medium. Moreover, language proficiency, cultural distance and cultural inclusiveness were significantly related to the adaptation outcomes as expected, most commonly with small effect sizes.

With respect to demographic factors, females tended to experience a slightly greater sense of belongingness although they had fewer friends and less frequent contact with their domestic peers. They reported greater life satisfaction, but also more psychological symptoms. Age was associated with better English language proficiency, but negatively correlated with frequency of contact with local students and psychological symptoms. Length of residence was related to less perceived cultural inclusiveness, social support and life satisfaction, but greater cultural distance and psychological symptoms. All of the effect sizes for these relationships were small.

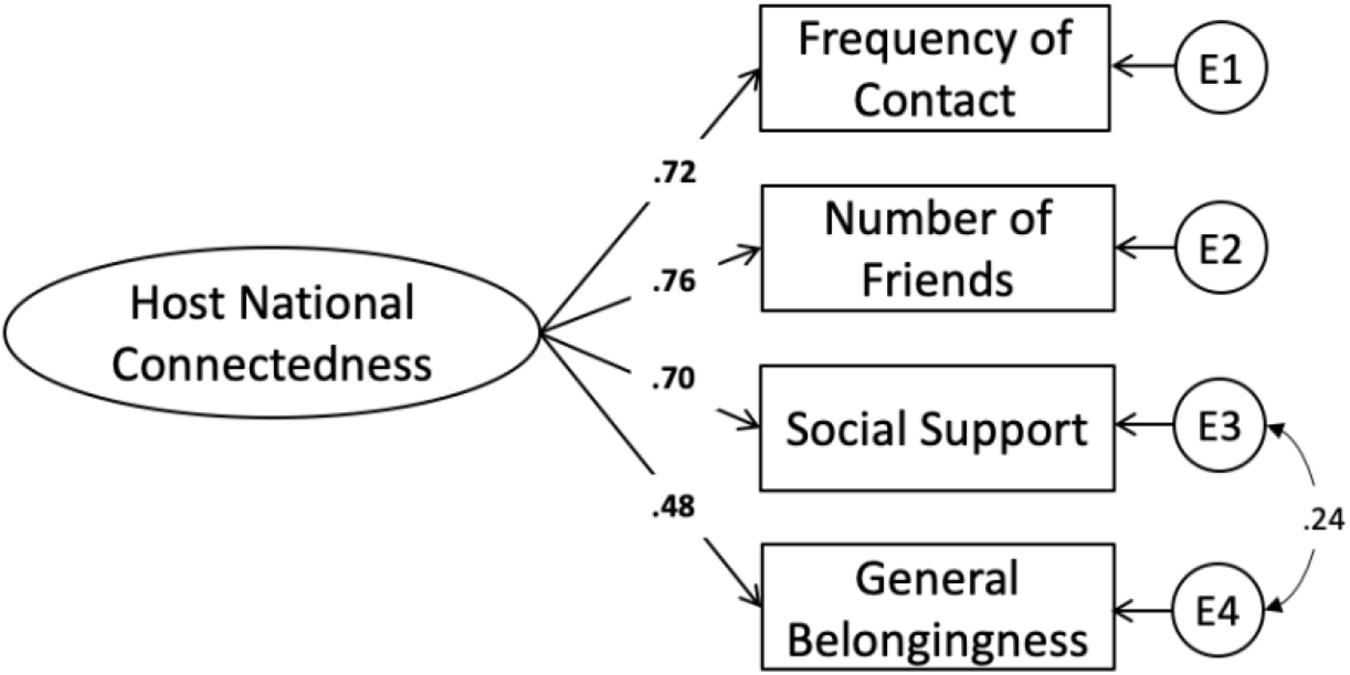

Measuring Host National Connectedness

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted in Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén, 2012) to assess our theoretical model of HNC with four indicators: frequency of contact, number of friends, social support, and general belongingness. We first estimated the single-factor model with the four independent indicators and obtained the following results: χ2(2, N = 1527) = 52.37, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.13, SRMR = 0.03. The modification indices suggested the correlation between the error terms of social support and general belongingness be added. The correlation is theoretically justifiable as both indicators are subjective measures of HNC, measuring the affective nature of connectedness rather than the quantitative, objective measures of friendships and contact. We allowed the error terms of social support and general belongingness to be correlated and obtained the following results for the modified model: χ2(1, N = 1527) = 0.76, ns., CFI = 1, RMSEA = 0.00, SRMR = 0.00. The model is presented in Figure 1. As can be seen in the figure, each of the four indicators loaded strongly on HNC. The HNC component score was used in the mediational model.

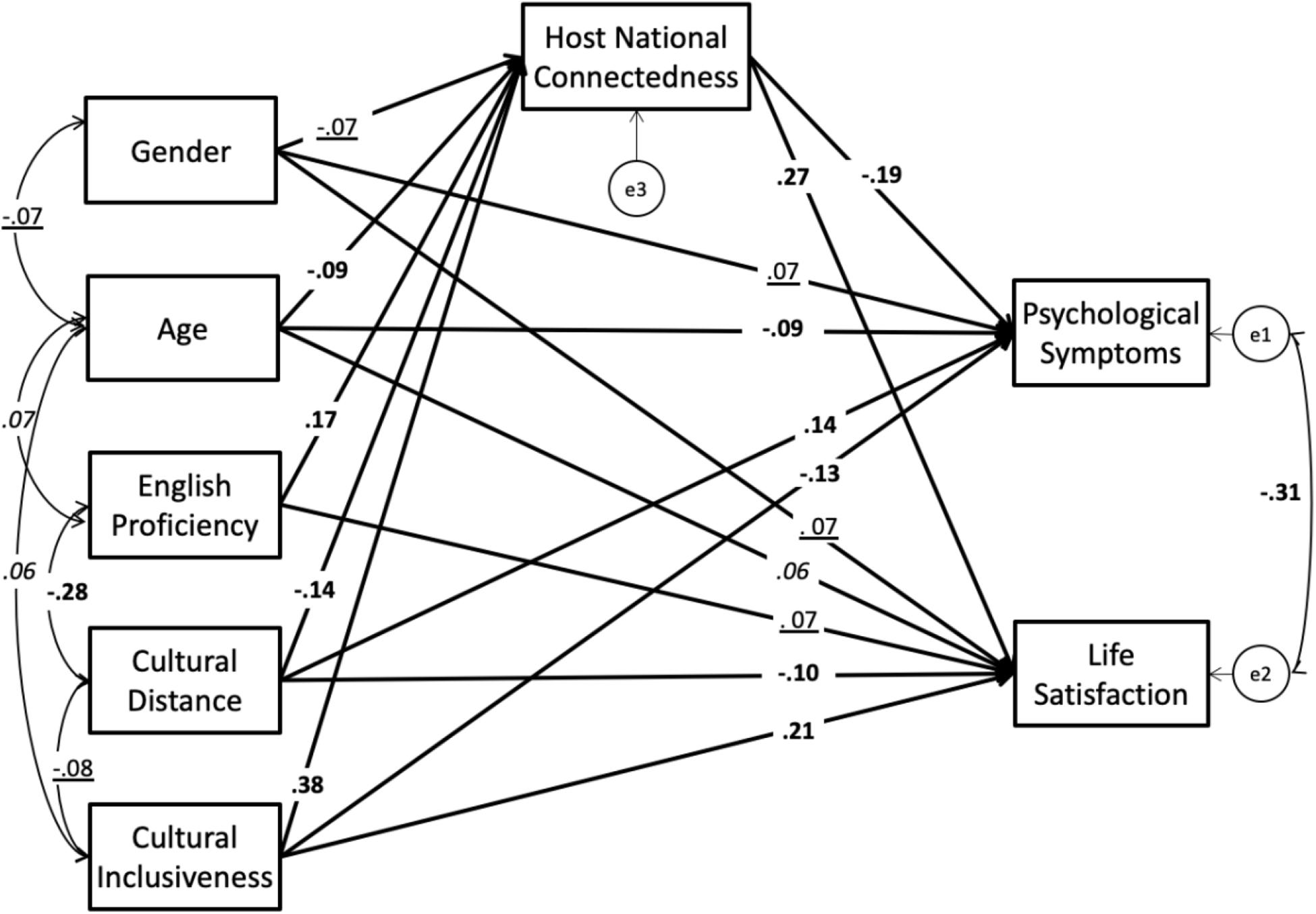

Testing the Mediational Model

We conducted a mediation path analysis in Mplus, starting with the saturated model including gender, age, length of stay, English proficiency, cultural distance, and cultural inclusion in the classroom as predictors; HNC as the mediator; and psychological symptoms and life satisfaction as outcomes (Kline, 2015). Length of stay in New Zealand had no significant effect on HNC or either outcome, so we removed it from the model. We further simplified the model by removing the non-significant direct effect of English proficiency on psychological symptoms. The resulting model is presented in Figure 2. This model, still close to the saturated model, had an excellent fit, χ2(1, N = 1527) = 0.89, ns; CFI = 1, RMSEA = 0.00, SRMR = 0.00. The indirect effects of gender and age were significant at 0.01 and those of the other predictors, at 0.001; the 95% confidence intervals from bootstrapped analyses using 1000 samples did not straddle zero (see Table 2 for all indirect effects). These findings indicate that host national connectedness mediated entirely the effect of English language proficiency on psychological symptoms, and partially all other effects.

Figure 2. Mediational model of psychological adaptation. Standardized coefficients are displayed. Coefficients significant at 0.05 are italicized, and those significant at 0.01 are underlined; all other coefficients are significant at 0.001.

Table 2. Standardized indirect effects on psychological symptoms and life satisfaction through host national connectedness.

Discussion

The present study identified host national connectedness as a critical factor in international students’ successful adaptation to cross-cultural transition. It was hypothesized that host national connectedness mediates the effects of personal resources, such as language proficiency, and contextual factors, such as perceived cultural distance and inclusiveness, on the psychological adaptation of international students. The hypotheses were confirmed. English language proficiency and cultural inclusiveness in the classroom predicted greater connectedness, and cultural distance predicted less connectedness for international students. Host national connectedness, in turn, predicted a higher level of life satisfaction and fewer psychological symptoms. With respect to demographic factors, being younger and female were related to less connectedness and more psychological symptoms; however, being older and female were associated with greater life satisfaction. Length of residence was negatively related to perceived social support and psychological adaptation. It should be emphasized that the effects of the demographic factors were small.

Host national connectedness is a complex construct. It can be conceptualized and measured in different ways, but essentially refers to ties that foster a sense of belongingness, dispel loneliness and offer a source of social support. Interpersonal contact and friendships are two indicators of these ties. The international literature has repeatedly noted the infrequency of social interactions between overseas and domestic students and described the low occurrence of intercultural friendships as a serious issue, not only for students, but also for educational institutions that aspire to enhance cultural awareness and cultivate global citizens (Smart et al., 2000; Smith and Khawaja, 2011; Quinton, 2020). In this study the ties between international students and host nationals both within and outside of their educational institutions were relatively weak, a common finding in New Zealand and abroad (Bochner et al., 1977, 1985; Volet and Ang, 1998; Ward and Masgoret, 2004; Neri and Ville, 2008; Townsend and Poh, 2008), especially for East Asian students in Western countries (Rienties et al., 2013).

Despite the obstacles to developing bonds with host nationals, connectedness is a strong predictor of psychological adaptation during cross-cultural transition. The findings in our study converge with the broader literature that links host national ties with international students’ well-being (Kashima and Loh, 2006; Ying and Han, 2006; Hendrickson et al., 2011; Cheung and Yue, 2013; Bender et al., 2019; Shu et al., 2020). While multiple sources of social support can bolster psychological adjustment in international students (Bender et al., 2019), a higher ratio of host nationals in one’s social networks is associated with greater satisfaction and contentment (Hendrickson et al., 2011). Therefore, it is worthwhile to consider the factors that might enhance connectedness and lead to better adaptive outcomes for international students.

In this study a mix of personal and contextual factors were investigated as antecedents of host national connectedness, i.e., English language proficiency, cultural distance, cultural inclusiveness in the classroom and demographic characteristics. In line with our hypothesized model, English language proficiency predicted greater host national connectedness. This is in agreement with those studies that point to an association between native language proficiency and greater social capital and social support; stronger national ties and feelings of belongingness; and less loneliness (Poyrazli et al., 2004; Montgomery and McDowell, 2009; Rienties et al., 2012; Pham and Tran, 2015). Indeed, the inability to speak the native language fluently is a major obstacle both to embeddedness in the national culture and to the maintenance of psychological well-being during cross-cultural transitions (Cetinkaya-Yildiz et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015; Cao et al., 2017; Taušová et al., 2019). Paralleling our findings on life satisfaction, Cao and Meng (2019) reported that language proficiency had both direct and indirect effects on international students’ social adaptation with the indirect effects mediated by their ties with host nationals. Similarly, we found that host national connectedness partially mediated the effects of language proficiency on life satisfaction; however, it fully mediated the effects language proficiency on psychological symptoms. Both studies highlight the critical role that connectedness plays in adapting to cross-cultural transitions.

Host national connectedness also partially mediated the negative effects of cultural distance on the adaptation outcomes. Again, this finding is in accordance with international student research. Cultural distance has been assessed in different ways, both as objective measures of difference and as individuals’ perceived dissimilarity between heritage and contact cultures. In both cases research demonstrates that cultural distance is associated with lower levels of host national connectedness (Furnham and Bochner, 1982; Fritz et al., 2008; Rienties et al., 2013; McGarvey et al., 2015; Bethel et al., 2016). There is also strong evidence that cultural distance has a detrimental influence on the psychological adaptation of overseas students (Ward and Searle, 1991; Furukawa, 1997; Sam, 2001; Galchenko and van de Vijver, 2007; Fritz et al., 2008). Not surprisingly, larger cultural differences mean that overseas students and host nationals have less in common upon which to base intimate contact and personal friendships. In addition, greater cultural distance presents more intense adjustive demands and taxes coping resources, resulting in lower levels of psychological well-being (Ward and Szabó, 2019).

In recent years there has been an evolving body of research on diversity climates in schools and how these impact the experiences of students from minority backgrounds. Experimental and longitudinal studies have provided ample evidence that diversity and inclusion norms affect intercultural experiences and outcomes (Nesdale et al., 2005; Titzmann et al., 2015; Tropp et al., 2016). Research has shown that teachers and peers shape educational environments that influence students’ intercultural relations and psychological well-being. Inclusive classroom norms are known to predict more intercultural friendships (Titzmann et al., 2015; Tropp et al., 2014). They also enhance a sense of belongingness for minority students, which leads, in turn, to better psychological and academic outcomes (Schachner et al., 2019). Our findings converge with these trends; specifically, cultural inclusiveness in the classroom predicted better psychological adaptation for international students, and its effects were partially mediated by host national connectedness.

Finally, we explored the relationships among demographic characteristics, host national connectedness and psychological well-being. The finding that younger students and males have a stronger sense of connectedness to host nationals is consistent with the results of Ward and Masgoret’s (2004) national survey of international students in New Zealand. Specifically, younger international students reported having more contact with their domestic peers, and males reported having more local friends. The findings on psychological adaptation were mixed. Females had more symptoms of psychological distress, largely in terms of anxiety and depression, a finding that is in accordance with international student research as well as established gender differences in mental health (Rosenfield and Smith, 2012; Alharbi and Smith, 2018); however, females also had higher levels of life satisfaction. This finding diverges from previous studies with international students (Sam, 2001; Gebregergis et al., 2019) including those conducted in New Zealand (Ward and Masgoret, 2004; Ward et al., 2009a). These studies failed to find significant gender differences in life satisfaction – as was the conclusion of a recent meta-analysis on this topic (Batz-Barbarich et al., 2018). As the effect size was small in this study, and as we have no theory-based explanation for this finding, it may be a spurious result. Finally, there was evidence, albeit with small effect sizes, that psychological adaptation was poorer in younger students. There is some evidence that higher levels of psychological distress are found in younger international students (Bulgan and Çiftçi, 2017; Alharbi and Smith, 2018), which may be due in part to normative developmental changes. Certainly, research has shown an increased risk for depression during the period of emerging adulthood (Rohde et al., 2013), which is in the lower age range of our sample.

While our findings on host national connectedness are not novel in themselves, the study advances theory and research on the adaptation of international students in four ways: (1) it offers a more complex conceptualization of connectedness by combining quantitative and qualitative assessments of contact and intimacy; (2) it integrates personal and contextual factors in a mediational model; (3) it reiterates the important, but often overlooked, point that international students’ adaptation is not only a product of their motivation and skills, but is also a product of their environments; and (4) it provides insights into policies and practices that can be implemented in educational institutions to increase the likelihood of stronger ties and greater connectedness between international students and their domestic peers.

Research Applications

Studies have consistently shown that international students expect and desire frequent contact with host nationals in both academic and social settings and that lack of intercultural interaction is seen as problematic (Choi, 1997; Trice, 2004; Ward and Masgoret, 2004). Research is equally clear that intercultural contact is perceived as more important and valuable by international students than their domestic peers (Beaver and Tuck, 1998; Volet and Ang, 1998; Smart et al., 2000). What can educational institutions do to foster meaningful connections between international and domestic students? How can they enrich international student experiences and enhance psychological well-being during cross-cultural transition?

Tertiary institutions can and do offer foundational language courses for non-native speakers, but they must also ensure that entry requirements for higher education are sufficiently high to enable meaningful social relationships and academic success. However, it is equally, if not more, important to address the institutions’ diversity climate. More specifically, it is critical to ensure diversity-receptive norms throughout educational institutions. In the broadest sense these norms should reflect frequent intercultural contact, a widespread valuing of cultural diversity, and the policies and practices that support and accommodate that diversity (Schachner et al., 2016, 2019; Schwarzenthal et al., 2018; Stuart and Ward, 2019; Ward et al., 2020). Such norms enhance not only social relations, but also academic performance and psychological well-being for minority students and in many instances for majority groups as well (Titzmann et al., 2015; Schachner et al., 2019).

Norms for intercultural contact can be strengthened through peer-pairing, buddy and mentoring programs between domestic students and international students (Quintrell and Westwood, 1994; Pritchard and Skinner, 2002), intercultural activities in residential halls (Todd and Nesdale, 1997), extra-curricular activities (Hendrickson, 2018) and intercultural team work in the classroom (Woods et al., 2013; Rienties and Nolan, 2014; Rienties et al., 2014), all of which have been shown to increase connections between overseas and local students. Intercultural contact and diversity-valuing norms in educational institutions can be shaped by academic staff. Not only can they structure course material and assignments to promote positive intercultural contact, but they are a powerful normative reference group and can enable positive social change (Deakins, 2009; Leask, 2009). For example, students’ perceptions of teachers’ readiness to foster intercultural contact and their interest in students’ diverse cultural backgrounds are associated with stronger feelings of belongingness and more positive intergroup relations between majority and minority students (Schwarzenthal et al., 2018; Schachner et al., 2019).

It is clear from the evidence that multicultural norm-setting in educational institutions can strengthen intercultural bonds and bolster the psychological well-being of international students. Although setting new norms can modify behaviors (Miller and Prentice, 2016), this is not always easy to achieve. Resistance to change, an absence of coordination, lack of social feedback, and “high costs” of modifying behaviors can present obstacles to shifting norms (Nyborg et al., 2016). Despite these barriers, a clear route to fostering multicultural norms in educational institutions is by introducing multicultural policies. Indeed, research has shown that multicultural policies in educational settings reduce the gaps in belongingness and academic achievement between students from majority and minority backgrounds (Celeste et al., 2019). Nyborg et al. (2016) have provided insights into the dynamic process of policy-initiated norm change in their discussion of social norms as solutions to a range of global challenges. They argue that policies create visible behavioral changes that can reach “tipping points,” altering individuals’ expectations about what other people will and should do. Moreover, individuals are more likely to conform to these expectations as the frequency of the expected behaviors increases, particularly if the behaviors are reinforced by positive social feedback, and non-conformity is sanctioned. In contrast to top-down, policy-initiated norm-setting, Cislaghi and Heise (2018) have advocated for “people led” norm-setting where bottom-up changes in community norms are undertaken in ways that are compatible with the social and cultural context. This opens up future possibilities for students to be more actively involved in institutional change.

Limitations and Future Research

Despite the important findings and applications of this research, the use of cross-sectional survey data is a major limitation. While our mediational model is grounded in theory and research on cross-cultural transition and psychological adaptation of international students, longitudinal data are needed to confirm the direction of the relationships amongst the variables of interest. It is also important to acknowledge that survey research such as this cannot determine causal relationships. When we refer to “exerting effects on…” in the description of the mediational model, we are referring to statistical effects rather than causal effects. Future studies should go beyond survey research and integrate experimental approaches to determine cause and effect relationships between the proposed antecedents and outcomes of host national connectedness. It is also recommended that qualitative methods be adopted for more in-depth explorations of the nuances and richness of the international student experience.

Although the study has a large sample size, the overall response rate for the survey was low (6.58%). It is not uncommon for web-based surveys to return less than 10% response rates (Fricker, 2008; Van Mol, 2017); however, this can introduce bias into the research. More broadly, biases such as social desirability responding, acquiescence and avoidance of scalar extremes, are known to threaten the validity of self-report surveys (Johnson et al., 2011). Self-ratings of language proficiency in particular can be problematic as meta-analyses have shown that self-ratings are only moderately correlated with performance measures (Zell and Krizan, 2014). It is also important to bear in mind that the research was conducted in New Zealand where most of the international students originate from Asian countries. The extent to which this might affect the study’s external validity is unknown.

Although the study has shed light on connectedness between international students and host nationals, it does not directly take into account the perceptions, attitudes and behaviors of members of the host society. This is important as research has shown that domestic students view international students in a stereotypic fashion (Spencer-Rodgers, 2001) and see them as posing realistic and symbolic threat (Ward et al., 2009b). They also often lack interest and motivation for intercultural interactions (Smart et al., 2000). Ultimately, host national connectedness is a reciprocal process (Ujitani and Volet, 2008), and the perspectives of local students and their wider community need to be taken into account. It would be worthwhile to investigate this topic in future research.

Concluding Comments

The present research has added to the current body of literature by conceptualizing and measuring host national connectedness as a complex, multi-faceted construct. Both objective aspects (such as number of host national friends and frequency of interaction with host nationals) and subjective aspects (such as feelings of belongingness and social support) should be included in the assessment of host national connectedness to fully capture its complexity. Moreover, the study demonstrates that it is important to go beyond the consideration of individual differences and to incorporate contextual variables for predicting host national connectedness and the psychological adaptation of international students. Most importantly, the findings suggest that connections with host nationals may serve as a functional mechanism through which international students ease their transition stress and cope with cultural differences. As international education increases across the globe, how best to enhance intercultural connectedness remains an important question for students, teachers, counselors, administrators and policy makers.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated for this study is available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the School of Psychology Human Ethics Committee under the delegated authority of Victoria University of Wellington’s Human Ethics Committee. In accordance with the pre-survey information provided to participants, completion of the survey was deemed to indicate informed consent.

Author Contributions

AB designed the study, undertook the data collection and analysis and produced a master’s thesis under the supervision of CW, who revised and updated the thesis text for publication. VF conducted additional statistical analyses and contributed to writing the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The research was funded by the School of Psychology, Victoria University of Wellington (Grant number 85050).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Alharbi, E. S., and Smith, A. P. (2018). Review of the literature on stress and wellbeing of international students in English-speaking countries. Internat. Educ. Stud. 11, 22–44. doi: 10.5539/ies.v11n6p22

Australian Education and International (2013). International student survey 2012: Overview report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Babiker, I. E., Cox, J. L., and Miller, P. M. (1980). The measurement of cultural distance and its relationship to medical consultations, symptomatology and examination performance of overseas students at Edinburgh University. Soc. Psych. 15, 109–116. doi: 10.1007/BF00578141

Barber, B. K., Stolz, H. E., and Olsen, J. A. (2005). Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monogr. Soc Res. Child Devel. 70, 1–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2005.00365.x

Batz-Barbarich, C., Tay, L., Kuykendall, L., and Cheung, H. K. (2018). A meta-analysis of gender differences in subjective well-being estimating effect sizes and associations with gender inequality. Psychol. Sci. 29, 1491–1503. doi: 10.1177/0956797618774796

Beaver, B., and Tuck, B. (1998). The adjustment of overseas students at a tertiary institution in New Zealand. New Zealand J. Educa. Stud. 33, 167–179.

Bender, M., van Osch, Y., Sleegers, W., and Ye, M. (2019). Social support benefits psychological adjustment of international students. J. Crosscultural Psychol. 50, 827–847. doi: 10.1177/0022022119861151

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., and Vedder, P. (eds) (2006). Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity and adaptation across national contexts. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Berry, J. W., and Sam, D. L. (2016). “Theoretical perspectives,” in The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology, 2nd Edn, eds D. L. Sam and J. W. Berry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 11–29.

Bethel, A., Szabo, A., and Ward, C. (2016). “Parallel lives: Predicting and enhancing connections between international and domestic students,” in Multi-Dimensional Transitions of International Students to Higher Education, eds D. Jindal-Snape and B. Rienties. (London: Taylor & Francis), 21–36.

Bochner, S. (2006). “Sojourners,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology, eds D. L. Sam and J. W. Berry (New York: Cambridge University Press), 181–197.

Bochner, S., Hutnik, N., and Furnham, A. (1985). The friendship patterns of overseas and host students in an Oxford student residence. J. Soc. Psychol. 125, 689–694. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1985.9713540

Bochner, S., McLeod, B. V., and Lin, A. (1977). Friendship patterns of overseas students: A functional model. Internat. J. Psychol. 12, 277–294.

Bradley, G. (2000). Responding effectively to the mental health needs of international students. High. Educ. 39, 417–433. doi: 10.1023/A:1003938714191

Bulgan, G., and Çiftçi, A. (2017). Psychological adaptation, martial satisfaction and academic self-efficacy of international students. J. Internat. Stud. 7, 687–702. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.570028

Cao, C., and Meng, Q. (2019). Mapping the paths from language proficiency to adaptation in Chinese students in a non-English speaking country: An integrative model of mediation. Curr. Psychol. J. Div. Perspect. Div. Psychol. Issues 38, 1564–1575. doi: 10.1007/s12144-017-9708-3

Cao, C., Zhu, C., and Meng, Q. (2017). Predicting Chinese international students’ acculturation strategies from socio-demographic variables and social ties. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 20, 85–96. doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12171

Celeste, L., Baysu, G., Phalet, K., Meeussen, L., and Kende, J. (2019). Can school diversity climates reduce belonging and achievement gaps between minority and majority youth? Multiculturalism, colorblindness and assimilationism addressed. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 45, 1603–1618. doi: 10.1177/0146167219838577

Cetinkaya-Yildiz, E., Cakir, S. G., and Kondakci, Y. (2011). Psychological distress among international students in Turkey. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 35, 534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.04.001

Cheung, C.-K., and Yue, X. D. (2013). Sustaining resilience through local connectedness among sojourn students. Soc. Indicat. Res. 111, 785–800. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0034-8

Choi, M. (1997). Korean students in Australian universities: Intercultural issues. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 16, 263–282. doi: 10.1080/0729436970160302

Church, A. (1982). Sojourner adjustment. Psychol. Bull. 91, 540–572. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.91.3.540

Cislaghi, B., and Heise, L. (2018). Theory and practice of social norms interventions: Eight common pitfalls. Globalizat. Health 14, 83. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0398-x

Dao, T. K., Lee, D., and Chang, H. (2007). Acculturation level, perceived English fluency, perceived social support level, and depression among Taiwanese international students. College Stu. J. 41, 287–295.

Deakins, E. (2009). Helping students value cultural diversity through research-based teaching. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 28, 209–226. doi: 10.1080/07294360902725074

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., and Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Doucerain, M. M., Deschênes, S. S., Gouin, J.-P., Amiot, C. E., and Ryder, A. G. (2017). Initial mainstream cultural orientations predict early social participation in the mainstream cultural group. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 43, 245–258.

Fricker, R. D. (2008). “Factors reflecting response rates for web and e-mail surveys,” in The Sage handbook of online research methods, eds N. Fielding, R. M. Lee, and G. Blank (Los Angeles, CA: Sage), 195–216. doi: 10.4135/9780857020055

Fritz, M. V., Chin, D., and DeMarinis, V. (2008). Anxiety, acculturation and adjustment among international and American students. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 32, 244–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.01.001

Furnham, A., and Bochner, S. (1982). “Social difficulty in a foreign culture: An empirical analysis of culture shock,” in Cultures in contact: Studies in cross-cultural interaction, ed S. Bochner (Oxford: Pergamon Press).

Furukawa, T. (1997). Cultural distance and its relationship to psychological adjustment of international exchange students. Psychiat. Clinic. Neurosci. 51, 87–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1997.tb02367.x

Galchenko, I., and van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2007). The role of perceived cultural distance in the acculturation of exchange students in Russia. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 31, 181–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.03.004

Gareis, E. (2012). Intercultural friendship: Effects of home and host region. J. Internat. Intercultural Commun. 5, 309–328. doi: 10.1080/17513057.2012.691525

Gebregergis, W. T., Tekie, D., Yikealo, D., and Habte, A. (2019). Antecedents of psychological adjustment of international students studying in China: The roles of self-efficacy and self-esteem. Open J. Soc. Sci. 7, 233–254. doi: 10.4236/jss.2019.72019

Geeraert, N., Li, R., Ward, C., Gelfand, M., and Demes, K. A. (2019). A tight spot: How personality moderates the impact of social norms on sojourner adaptation. Psychol. Sci. 30, 333–342. doi: 10.1177/0956797618815488

Hanassab, S. (2006). Diversity, international students, and perceived discrimination: Implications for educators and counselors. J. Stud. Internat. Edu. 10, 157–172. doi: 10.1177/1028315305283051

Hendrickson, B. (2016). Comparing international students friendship networks in Buenos Aires: Direct enrolment programs versus study abroad centers. Front. Interdiscipl. J. Stud. Abroad 27, 47–69.

Hendrickson, B. (2018). Intercultural connectors: Explaining the influence of extra-curricular activities and tutor programs on international student friendship network development. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 63, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.11.002

Hendrickson, B., Rosen, D., and Aune, R. K. (2011). An analysis of friendship networks, social connectedness, homesickness, and satisfaction levels of international students. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 35, 281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.08.001

Hernández-Nanclares, N. (2016). “The transition processes of Erasmus students: Motivation, social networks and academic performance,” in Multi-Dimensional Transitions of International Students to Higher Education, eds D. Jindal-Snape and B. Rienties (London: Routledge), 240–255.

Johnson, T. P., Shavitt, S., and Holbrook, A. L. (2011). “Survey response styles across cultures,” in Cross-cultural research methods in psychology, eds D. Matsumoto and F. J. R. van de Vijver (New York: Cambridge University Press).

Kashima, E. S., and Loh, E. (2006). International students’ acculturation: Effects of international, conational and local ties and need for closure. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 30, 471–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.12.003

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 4th Edn. New York, NY: Guilford.

Le, T. N., Lai, M. H., and Wallen, J. (2009). Multiculturalism and subjective happiness as mediated by relational variables. Cult. Div. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 15, 303–313. doi: 10.1037/a0015507

Leask, B. (2009). Using formal and informal curricula to improve interactions between home and international students. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 13, 205–221. doi: 10.1177/1028315308329786

Lee, J. J., and Rice, C. (2007). Welcome to America? International students’ perceptions of discrimination. High. Educat. 53, 381–409.

Li, P., Sepanski, S., and Zhao, X. (2006). Language history questionnaire: A web-based interface for bilingual research. Behav. Res. Methods 38, 202–210. doi: 10.3758/bf03192770

Li, R. Y., and Kaye, M. (1998). Understanding international students’ concerns and problems. J. High. Educat. Policy Manage. 20, 41–50. doi: 10.1080/1360080980200105

Li, X., and Chen, W. (2014). Facebook or renren? A comparative study of social networking site use and social capital among Chinese international students in the United States. Comput. Human Behav. 35, 116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.012

Lin, J.-H., Peng, W., Kim, M., Kim, S. Y., and LaRose, R. (2012). Social networking and adjustments among international students. New Med. Soc. 14, 421–440. doi: 10.1177/1461444811418627

Lun, V. M.-C., Fischer, R., and Ward, C. (2010). Exploring cultural differences in critical thinking: Is it about my thinking style or the language I speak? Learn. Indivi. Differ. 20, 604–616. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2010.07.001

Malone, G. P., Pillow, D. R., and Osman, A. (2012). The general belongingness scale (GBS): Assessing achieved belongingness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 52, 311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.027

Masgoret, A.-M., and Gardner, R. C. (1999). A causal model of Spanish immigrant adaptation in Canada. J. Multilingual Multicult. Dev. 20, 216–236. doi: 10.1080/01434639908666378

McGarvey, A., Brugha, R., Conroy, R. M., Clarke, E., and Byrne, E. (2015). International students’ experience of a Western medical school: A mixed methods study exploring the early years in the context of social and cultural adjustment compared to students from the host country. BMC Med. Educat. 15:111. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0394-2

McGhie, V. (2017). Entering university studies: Identifying enabling factors for a successful transition from school to university. High. Educat. 73, 407–422. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0100-2

Miller, D. T., and Prentice, D. A. (2016). Changing norms to change behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 67, 339–361. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015013

Montgomery, C. (2010). Understanding the international student experience: Universities in the 21st century. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Montgomery, C., and McDowell, L. (2009). Social networks and the international student experience. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 13, 455–466. doi: 10.1177/1028315308321994

Neri, F. V., and Ville, S. (2008). Social capital renewal and the academic performance of international students in Australia. J. Socio Econ. 37, 1515–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2007.03.010

Nesdale, D., Griffith, J., Durkin, K., and Maass, A. (2005). Empathy, group norms and children’s ethnic attitudes. Appl. Devel. Psychol. 26, 623–637. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2005.08.003

Nyborg, K., Anderies, J. M., Dannenberg, A., Lindahl, T., Schill, C., Schlüter, M., et al. (2016). Social norms as solutions. Science 354, 42–43. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8317

Ong, A. S. J., and Ward, C. (2005). The construction and validation of a social support measure for sojourners: The index of sojourner social support (ISSS) scale. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 36, 637–661. doi: 10.1177/0022022105280508

Peacock, N., and Harrison, N. (2009). “It’s so much easier to go with what’s easy:” “Mindfulness” and the discourse between home and international students in the United Kingdom. J. Stud. Internat. Educ. 13, 487–508. doi: 10.1177/1028315308319508

Pham, L., and Tran, L. (2015). Understanding the symbolic capital of intercultural interactions: A case study of international students in Australia. Internat. Stud. Sociol. Educat. 5, 204–224. doi: 10.1080/09620214.2015.1069720

Poyrazli, S., Arbona, C., Nora, A., McPherson, R., and Pisecco, S. (2002). Relation between assertiveness, academic self-efficacy, and psychosocial adjustment among international graduate students. J. Colleg. Stud. Devel. 43, 632–642.

Poyrazli, S., Kavanaugh, P. R., Baker, A., and Al-Timimi, N. (2004). Social support and demographic correlates of acculturative stress in international students. J. Coll.Counsel. 7, 73–82. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2004.tb00261.x

Pritchard, R. M. O., and Skinner, B. (2002). Cross-cultural partnerships between home and international students. J. Stud. Internat. Educ. 6, 323–353. doi: 10.1177/102831502237639

Quinton, W. J. (2020). So close and yet so far? Predictors of international students’ socialization with host nationals. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 74, 7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.10.003

Quintrell, N., and Westwood, M. (1994). The influence of a peer-pairing programme on international students’ first year experience and the use of student services. High. Educ. Res. Devel. 13, 49–57. doi: 10.1080/0729436940130105

Rajapaksa, S., and Dundes, L. (2002-2003). It’s a long way home: International student adjustment to living in the United States. J. Colleg. Stud. Retent. 4, 15–28. doi: 10.2190/5HCY-U2Q9-KVGL-8M3K

Rienties, B., Beausaert, S., Grohnert, T., Niemantsverdriet, S., and Kommers, P. (2012). Understanding academic performance of international students: The role of ethnicity, academic and social integration. High. Educa. 63, 685–700. doi: 10.1007/s10734-011-9468-1

Rienties, B., Heliot, Y., and Jindal-Snape, D. (2013). Understanding social learning relations of international students in a large classroom using social network analysis. High. Educ 66, 489–504. doi: 10.1007/s10734-013-9617-9

Rienties, B., Johan, N., and Jindal-Snape, D. (2014). A dynamic analysis of social capital- building of international and UK students. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 36, 1212–1235. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2014.886941

Rienties, B., and Nolan, E.-M. (2014). Understanding friendship and learning networks of international and host students using longitudinal social network analysis. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 41, 165–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.12.003

Rohde, P., Lewinsohn, P. M., Klein, D. N., Seeley, J. R., and Gau, J. M. (2013). Key characteristics of major depressive disorder occurring during childhood, adolescence, emerging adulthood and adulthood. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 1, 41–53. doi: 10.1177/2167702612457599

Rohrlich, B. F., and Martin, J. N. (1991). Host country and re-entry adjustment of student sojourners. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat 15, 163–182. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(91)90027-E

Rosenfield, S., and Smith, D. (2012). “Gender and mental health: Do men and women have different amounts or types of problems?,” in eds T. L. Scheid and T. N. Brown (New York: Cambridge University Press), 256–267. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511984945.017

Sam, D. L. (2001). Satisfaction with life among international students: An exploratory study. Soc. Indicat. Res. 53, 315–337. doi: 10.1023/A:1007108614571

Sam, D. L., Tetteh, D. C., and Amponsah, B. (2015). Satisfaction with life and psychological symptoms among international students in Ghana and their correlates. Internat. J. Intercult Relat. 49, 156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.09.001

Sawir, E., Marginson, S., Deumert, A., Nyland, C., and Ramia, G. (2008). Loneliness and international students: an Australian study. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 12, 148–180. doi: 10.1177/1028315307299699

Sawir, E., Marginson, S., Forbes-Mewett, H., Nyland, C., and Ramia, G. (2012). International student security and English language proficiency. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 16, 434–454. doi: 10.1177/1028315311435418

Schachner, M. K., Brenick, A., Noack, P., van de Vijver, F. J. R., and Heizmann, B. (2015). Structural and normative conditions for interethnic friendships in multiethnic classrooms. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 47, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.02.003

Schachner, M. K., Noack, P., van de Vijver, F. J. R., and Eckstein, K. (2016). Cultural diversity climate and psychological adjustment at school- Equality and inclusion versus cultural pluralism. Child Devel. 87, 1175–1191. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12536

Schachner, M. K., Schwarzenthal, M., van de Vijver, F. J. R., and Noack, P. (2019). How all students can belong and achieve: Effects of the cultural diversity climate amongst students of immigrant and non-immigrant background in Germany. J. Educat. Psychol. 111, 703–716. doi: 10.1037/edu0000303

Schwarzenthal, M., Schachner, M. K., van der Vijver, F. J. R., and Juang, L. (2018). Equal but different: Effects of equality/inclusion and cultural pluralism on intergroup outcomes in multi-ethnic classrooms. Cult. Div. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 24, 260–271. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000173

Searle, W., and Ward, C. (1990). The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 14, 449–464. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(90)90030-Z

Shu, F., Ahmed, S. F., Pickett, M. L., Ayman, R., and McAbee, S. T. (2020). Social support perceptions, network characteristics, and international student adjustment. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 74, 136–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.11.002

Smart, D., Volet, S., and Ang, G. (2000). Fostering social cohesion in universities: Bridging the cultural divide. Canberra: Department of Education, Training, and Youth Affairs.

Smith, R. A., and Khawaja, N. G. (2011). A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 35, 699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.08.004

Spencer-Rodgers, J. (2001). Consensual and individual stereotypic beliefs about international students by American host nationals. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 25, 639–657. doi: 10.1016/S0147-1767(01)00029-3

Stuart, J., and Ward, C. (2015). “The ecology of acculturation,” in Counselling across cultures: Toward inclusive cultural empathy, 7th Edn, eds P. Pedersen, J. G. Draguns, W. J. Lonner, J. E. Trimble, and M. Scharrón-del Rio (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 383–405.

Stuart, J., and Ward, C. (2019). Exploring everyday experiences of cultural diversity: The construction, validation and application of the Normative Multiculturalism Scale. Europ. J. Soc. Psychol. 49, 313–332. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2542

Sümer, S., Poyrazli, S., and Grahame, K. (2008). Predictors of depression and anxiety among international students. J. Counsel. Devel. 86, 429–437. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00531.x

Taušová, J., Bender, M., Dimitrova, R., and van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2019). The role of perceived cultural distance, personal growth initiatives, language proficiencies, and tridimensional acculturation orientations for psychological adjustment among international students. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 69, 11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.11.004

Titzmann, P. F., Brenick, A., and Silbereisen, R. K. (2015). Friendships fighting prejudice: A longitudinal perspective on adolescents’ cross-group friendships with immigrants. J Youth Adolescent 44, 1318–1331. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0256-6

Todd, P., and Nesdale, D. (1997). Promoting intercultural contact between Australian and international university students. J. High. Educ. Policy Administr. 19, 61–76. doi: 10.1080/1360080970190108

Tomoschuk, B., Ferreira, V. S., and Gollan, T. H. (2019). When a seven is not a seven: Self-ratings of bilingual language proficiency differ between and within language populations. Bilingualism Language Cognition 22, 516–536.

Townsend, P., and Poh, H. J. (2008). An exploratory study of international students studying and living in a regional area. J. Market. High. Educ. 18, 240–263. doi: 10.1080/08841240802487411

Trice, A. (2004). Mixing it up: International graduate students’ social interactions with American students. J. Colleg. Stud. Devel. 45, 671–687. doi: 10.1353/csd.2004.0074

Tropp, L. R., O’Brien, T. C., González Gutierrez, R., Valdenegro, D., Migacheva, K., Tezanos-Pinto, P., et al. (2016). How school norms, peer norms and discrimination predict interethnic experiences among ethnic minority and majority youth. Child Devel. 87, 1436–1451. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12608

Tropp, L. R., O’Brien, T. C., and Migacheva, K. (2014). How peer norms of inclusion and exclusion predict children’s interest in cross-ethnic friendships. J. Soc. Issues 70, 151–166. doi: 10.1111/josi.12052

Ujitani, E., and Volet, S. (2008). Socio-emotional challenges in international education: Insight into reciprocal understanding and intercultural relational development. J. Res. Internat. Educ. 7, 279–303. doi: 10.1177/1475240908099975

Van Mol, C. (2017). Improving web survey efficiency: The impact of an extra reminder and reminder content on web survey response. Internat. J. Soc. Res. Methodol 20, 317–327. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2016.1185255

Volet, S., and Ang, G. (1998). Culturally mixed groups on international campuses: An opportunity for international learning. High. Educat. Res. Develop. 17, 5–23.

Wang, K., Wei, M., and Chen, H.-H. (2015). Social factors in cross-national adjustment: Subjective well-being trajectories among Chinese international students. Counsel. Psychol. 43, 272–298. doi: 10.1177/0011000014566470

Ward, C., Fischer, R., Lam, F. S. Z., and Hall, L. (2009a). The convergent, discriminant and incremental validity of scores on a self-report measure of cultural intelligence. Educat. Psychol. Measure. 69, 85–105. doi: 10.1177/0013164408322001

Ward, C., Masgoret, A.-M., and Gezentsvey, M. (2009b). Investigating attitudes toward international students: Programs and policy implications for social integration and international education. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 3, 79–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2409.2009.01011.x

Ward, C., Kim, I., Karl, J. A., Epstein, S., and Park, H.-J. (2020). How normative multiculturalism relates to immigrant well-being. Cult Dive. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000317

Ward, C., and Masgoret, A.-M. (2004). The experiences of international students in New Zealand: Report on the results of the national survey. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Ward, C., and Searle, W. (1991). The impact of value discrepancies and cultural identity on psychological and sociocultural adjustment of sojourners. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 15, 209–225. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(91)90030-K

Ward, C., and Szabó, Á (2019). “Affect, behavior, cognition and development: Adding to the alphabet of acculturation,” in Handbook of culture and psychology, eds D. Matsumoto and H. S. Hwang (New York: Oxford University Press), 640–692.

Wilton, L., and Constantine, M. G. (2003). Length of residence, cultural adjustment difficulties, and psychological distress symptoms in Asian and Latin America international college students. J. Colleg. Counsel. 6, 177–186. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2003.tb00238.x

Woods, P., Poropat, A., Barker, M., Hills, R., Hibbins, R., and Borbasi, S. (2013). Building friendships through a cross-cultural mentoring program. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 37, 523–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.08.004

Yang, B., Teraoka, M., Eichenfield, G. A., and Audas, M. C. (1994). Meaningful relationships between Asian international and U.S. college students: A descriptive study. Colleg. Stud. J. 28, 108–115.

Yang, Y., Zhang, Y., and Sheldon, K. M. (2018). Self-determined motivation for study abroad predicts lower culture shock and greater wellbeing among international students: The mediating role of basic needs satisfaction. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 63, 95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.10.005

Yeh, J. Y., and Inose, M. (2003). International students’ reported English fluency, social support satisfaction, and social connectedness as predictors of acculturative stress. Counsel. Psychol. Quart. 16, 15–28. doi: 10.1080/0951507031000114058

Ying, Y. W., and Han, M. (2006). The contribution of personality, acculturative stressors, and social affiliation to adjustment: A longitudinal study of Taiwanese students in the United States. Internat. J. Intercult. Relat. 30, 623–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.02.001

Ying, Y. W., and Liese, L. H. (1994). Initial adjustment of Taiwanese students to the United States: The impact of post-arrival variables. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 25, 466–477. doi: 10.1177/0022022194254003

Yu, Y., and Moskal, M. (2019). Missing intercultural engagements in the university experiences of Chinese international students in the UK. J. Comparat. Internat. Educat. 49, 654–671.

Zell, E., and Krizan, Z. (2014). Do people have insight into their abilities? A metasynthesis. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9, 111–125. doi: 10.1177/1745691613518075

Zhang, J., and Goodson, P. (2011). Acculturation and psychosocial adjustment of Chinese international students: Examining mediation and moderation effects. Internat. J. Intercult. Relations 35, 614–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.11.004

Keywords: connectedness, cultural inclusiveness, international students, psychological adaptation, New Zealand, well-being

Citation: Bethel A, Ward C and Fetvadjiev VH (2020) Cross-Cultural Transition and Psychological Adaptation of International Students: The Mediating Role of Host National Connectedness. Front. Educ. 5:539950. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.539950

Received: 03 March 2020; Accepted: 14 August 2020;

Published: 11 September 2020.

Edited by:

Elizabeth Fraser Selkirk Hannah, University of Dundee, United KingdomReviewed by:

Jeroen Huisman, Ghent University, BelgiumVincent Donche, University of Antwerp, Belgium

Copyright © 2020 Bethel, Ward and Fetvadjiev. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Colleen Ward, Y29sbGVlbi53YXJkQHZ1dy5hYy5ueg==

Alicia Bethel

Alicia Bethel Colleen Ward

Colleen Ward Velichko H. Fetvadjiev

Velichko H. Fetvadjiev