- 1University Teaching Academy, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 2Institute of Education, College of Arts, Humanities and Education, University of Derby, Derby, United Kingdom

The Higher Education and Research Act established both a regulatory framework and the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) with associated metrics for student retention, progression and employability in the United Kingdom. As a key site in meeting these requirements, the significance of personal tutoring is clear. Despite this, according to existing institutional research, there is a need for developmental support, greater clarification on the requisite competencies, and adequate recognition for those undertaking this challenging role. Moreover, arguably compounding these concerns is the lack of distinct professional standards for personal tutoring and advising against which to measure effective practice, only recently addressed by the publication of The UKAT Professional Framework for Advising and Tutoring. Through a review of the literature supported by findings from a survey of practitioners, this paper discusses the need for such standards, and the skills and competencies populating them. Additionally, the usefulness of pre-existing standards pertinent to tutoring work (such as the United Kingdom Professional Standards Framework for Teaching and Supporting Learning in HE) are evaluated and the value and recognition with which personal tutoring standards could be associated are advanced. The survey supported the need for specific standards – represented by the UKAT framework – as evident from the literature. Justifications provided for both this and the opposing view are examined. Clarity for both individual practitioners and institutions was stipulated along with meaningful recognition and reward for this work which is considered highly important and yet ‘invisible.’ The participants and literature reviewed identify relevant content along with illuminating the debate about the relationships between personal tutoring, teaching and professional advising roles. Valuable analysis of standards, recognition and reward also emerged. This is considered by discussing the connection between standards and changes to practice, responses to policy developments and the purpose of ‘standards’ in comparison to ‘guidance.’ The paper proposes that the recent introduction and use of a bespoke framework is a necessary response to alleviate some of the current tensions which beset personal tutoring and advising in higher education.

Introduction

The continuing importance of personal tutoring in United Kingdom Higher Education (HE) is evident from recent research (Thomas, 2012; Thomas et al., 2017) and policy (OfS, 2018). However, corresponding understanding and recognition has not readily followed and therefore it may often lack attention, support, and development at practitioner level (Owen, 2002; Ridley, 2006; Stephen et al., 2008; McFarlane, 2016; Walker, 2020). In addition, the ‘massification’ and widening access of United Kingdom HE has hastened the need to meet increasingly diverse student needs. This situation both creates the demand for individualized support through personal tutoring and arguably, simultaneously renders it impossible to deliver effectively given unmanageable student/staff ratios and workload demands, also recently identified as key challenges for United States ‘faculty advisors’ (Hart-Baldridge, 2020).

The response to these dilemmas in recent United Kingdom-based literature and support materials has provided definitions and depictions of effective practice through modeling tutoring interactions (Stork and Walker, 2015; Lochtie et al., 2018) and evidence of positive impact from developmental training (Walker, 2020). Inherent within the outcomes of such research is the call for the ‘professionalization’ of personal tutoring. In the United States, wider research on defining the role from those undertaking it (Larson et al., 2018), identifying required competencies (Menke et al., 2018) and the question of professionalization has been carried out (Shaffer et al., 2010; McGill, 2019; McGill et al., 2020). While the last of these is arguably more advanced in the United States, comparable dilemmas exist and leaders in the field argue the role has not yet met the sociological and societal conceptions of a ‘profession’ (Shaffer et al., 2010; McGill, 2019).

To determine how it may be initiated and achieved, one has to examine what may be associated with ‘professionalization’ more closely. Central to such an endeavor would seem to be the establishment and use of professional standards for the role (Walker, 2020) from which institutional and sectoral recognition and qualification can follow. If comparable standards constitute the foundation of professional teaching in HE [through the United Kingdom Professional Standards Framework for Teaching and Supporting Learning in HE (UK PSF; Advance HE, 2011)] and associated Postgraduate Certificates and Higher Education Academy (HEA) Fellowship, then surely the same applies to personal tutoring? While some may argue that teaching and personal tutoring coalesce in the single role of an ‘academic’ and view them as inter-dependent, previous studies clearly show HE teachers’ views on the latter’s particular demands and requirements in addition to the gaps in training and support for the role (Owen, 2002; Ridley, 2006; Stephen et al., 2008; McFarlane, 2016; Hart-Baldridge, 2020; Walker, 2020).

‘As higher education acclimates to the disequilibrium caused by change, the stature and legitimacy of academic advising will rise … During this time, all academic advisors … will be increasingly judged on their expertise and knowledge as well as their abilities and the results of their work. As a result they will be seated at the decision-making tables at colleges and universities across the globe … We predict that by 2025, academic advisors will garner respect from all institutional leaders and faculty members.’

(McGill and Nutt, 2016, p. 353)

This paper explores the urgent issues pertaining to personal tutoring contained within McGill and Nutt’s (2016) assertion, namely its importance, skills and attributes, and recognition, and their co-dependency, in the context of sectoral flux. Comprising a review of key literature discussed alongside findings from a pilot research study undertaken, this paper both explores the context within which the United Kingdom Advising and Tutoring association’s (UKAT) new Professional Framework for Advising and Tutoring [UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT), 2019, Supplementary Appendix 2] was developed and considers its relevance. The latter is examined in terms of the needs of the principal potential users and evaluation of pre-existing standards pertinent to tutoring work. In doing so, skills and competencies populating them and the new UKAT framework are discussed and the value and recognition with which discrete standards could be associated are proposed. The various intersections and discrepancies between the literature and the key themes of the study’s findings are explored.

Terminology and the International Perspective

This study is within the United Kingdom context. However, given that ‘academic advisor,’ the term used in the United States and other countries (NACADA, 2017a), is broadly synonymous with ‘personal tutor’ (Grey and Lochtie, 2016), this article draws on international literature to inform the British situation while using the latter term unless directly quoting and relevant. Indeed, the preponderance of United States studies cited illustrates the richer history of American academic advising research in comparison to the dearth of such work in the United Kingdom. ‘Faculty role advisors,’ where academics undertake advising alongside their other duties equates to the dominant model of personal tutoring in the United Kingdom. ‘Primary role advisors,’ where advising is the entire role, has an increasing number of British counterparts where it is sometimes referred to as the ‘super tutor’ model with exemplar job titles including ‘Student Engagement and Retention Officer’ (University of Huddersfield), ‘Student Support Officer’ (University of Sheffield), and ‘Transition and Retention Tutor’ (University of Hull). The fact the latter is the dominant role type in the United States may partly explain the imbalance in professional development and research.

Pilot Research Study Methodology

A pilot study, in the form of an online survey (Supplementary Appendix 1), was undertaken to assess the views of those involved in the delivery and management of personal tutoring practitioners in the United Kingdom. The survey sought the views of participants in three areas. First, the relevance, adequacy, and usefulness of pre-existing standards. Second, the necessity for, and potential benefits of, distinct tutoring standards in addition to the skills and competencies which are associated with the new UKAT framework [UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT), 2019]. Third, the extent to which they felt tutoring to be valued, rewarded, and recognized (before assessing the demand for separate professional recognition and how practice may benefit). This represents the order of the survey whereas in the subsequent discussion and data tables, the order of the first and second areas is reversed. These multiple areas were identified in the survey design due to their close relation. Given the width of this scope, the paper discusses the data pertaining to key elements of these broad and complex areas and thus represents a pilot for future work on additional related aspects.

The UKAT framework [UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT), 2019] was published in February 2019 and the latest version, including professional recognition descriptors, in November of the same year when associated professional awards were initiated in pilot form by UKAT. The survey was undertaken between these two dates during July and August 2019.

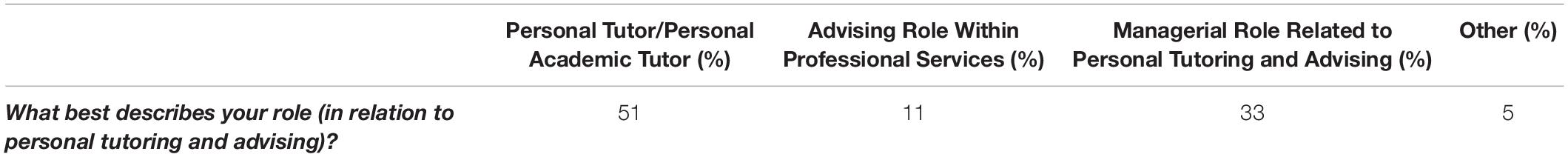

Fifty-seven responses were received from participants representing 26 United Kingdom universities. Two respondents did not state their institution and one was from an international university. The research population was comprised of self-selecting members of UKAT (numbering approximately 240 at the time of the survey), a sector body constituting individuals engaged with personal tutoring and advising, whether that be as a practitioner, leader or in a related support role (see Table 1). A snowball sampling technique was used to gather responses and therefore some respondents may have been from outside UKAT.

The survey constituted 15 questions of different types: demographic (for role titles, institutions and role types), multiple choice (allowing for multiple responses), scaling/ranking, closed (with yes/no/don’t know response options) and free text. Both the closed and scaling/ranking questions were accompanied by free text questions asking respondents to briefly explain their answers. The rationale for this, and the question types represented, reflected the intention to gain as much meaningful data as possible in a study seeking views on a subjective topic.

Data Analysis

Both quantitative and qualitative data were gathered and an inductive coding approach was used to analyze the latter. Initial reading and annotation was followed by identification of themes and a subsequent thematic content analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Bryman, 2008).

The Necessity and Usefulness of Professional Standards for Personal Tutoring and Advising

To discuss the necessity and usefulness of discrete standards for personal tutoring, one needs to consider personal tutoring’s importance and how they may help overcome the challenges it faces. In addition, the content of standards, in particular tutor skills and competencies, can be a key determiner of relevance and meaningfulness. Illustrated with relevant literature and findings from the pilot study, this section examines each of these three interlinked areas.

The Importance of Personal Tutoring at Policy, Institution, Practitioner, and Student Level

The support provided by an institution is judged by the metrics and objectives associated with the regulatory framework (OfS, 2018) and Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) established by the Higher Education and Research Act (2017): student retention, progression, and employability, a high quality academic experience and value for money (OfS, 2018, p. 4). Arguably vital in meeting these requirements, the increasing attention paid to personal tutoring is perhaps not surprising. Moreover, this focus is borne out of student-centered strategy following the 2012 increase in tuition fees and diversification of student needs resulting in HE institutions re-evaluating their relationship with students. The headlines from key research in the field convey a similar high level of importance. The comprehensive and seminal What Works? reports (Thomas, 2012; Thomas et al., 2017) affirm proactive holistic support through personal tutoring as the way to achieve the ‘belonging’ at the heart of student retention and success. The persistence of differences in student outcomes for ‘at risk’ groups in institutions (Mountford-Zimdars et al., 2015; OfS, 2019a,b; UUK/NUS, 2019) which universities are charged with addressing can be combatted through tutoring enabling student engagement and attainment of social and cultural capital (Mountford-Zimdars et al., 2015). An improved student experience and student success is attributed to good personal tutoring (Braine and Parnell, 2011; Battin, 2014; Pellagrino et al., 2015; McFarlane, 2016). It is important to retention and progression (Smith, 2008; Drake, 2011; Webb et al., 2017) and personal tutors can be influential in the final decision of students who are thinking of leaving (Bowden, 2008). Leach and Wang (2015) found those who receive good academic advising are twice as likely to prosper from positive wellbeing and be engaged in their professional careers at work. Given such a level of significance is placed on it then one would assume a set of standards is necessary in order to undertake, measure and recognize the endeavor.

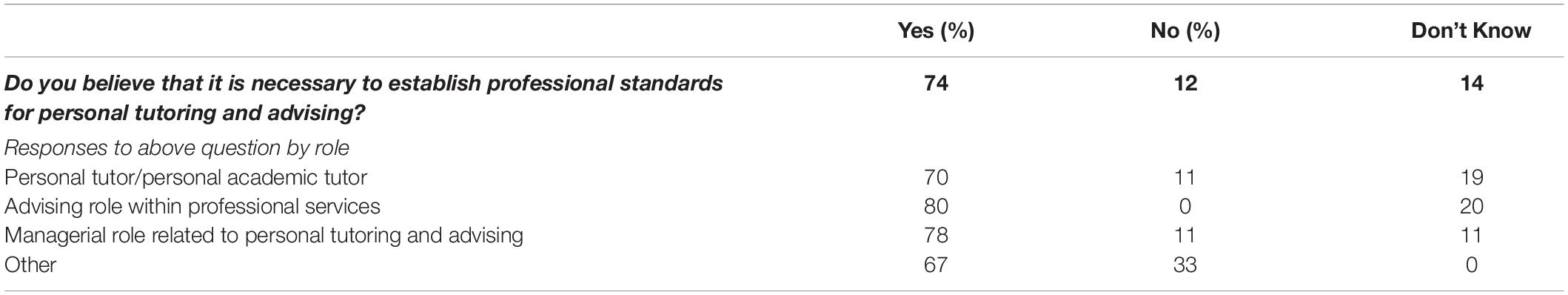

Almost three quarters of respondents (across role types) in the pilot study indeed believed it is necessary for professional standards for personal tutoring and advising to be established (see Table 2). Respondents’ reasoning for this view included the importance of tutoring to students’ transition to HE and wider experience as well as the associated need for professionalization.

Table 2. Responses to the question “Do you believe that it is necessary to establish professional standards for personal tutoring and advising?”

The Challenges Facing Personal Tutoring and How Professional Standards May Help

Despite the significant evidence of value, and the fact nearly all academics will undertake personal tutoring at some point in their career (Mynott, 2016, p. 104), personal tutoring systems have been subject to chronic under-resourcing and described as ‘in crisis’ (Evans, 2009). The tension between sufficiently organizing personal tutoring and rapid expansion was voiced over 20 years ago (Rivis, 1996, p. 46). More recent reports have articulated unmet student needs and limited academic and pastoral support (National Audit Office, 2007; House of Commons Public Accounts Committee, 2008) leading institutions to review their tutorial structures and provision. Time pressures associated with these tensions may explain the ‘academic research desert’ of personal tutoring (Thomas, 2018, p. x) and, specifically, the scarcity of studies from those actually undertaking the role (Ghenghesh, 2018), a group engaged by this pilot study. Habley’s (2009) summary of advising in the United States may equally apply to the current United Kingdom context:

‘…to date, a unique and credible body of knowledge is non-existent, evidence supporting the impact of advising is insufficient, and a coherent and widely delivered curriculum for advising is currently unavailable.’ [my italics]

(p. 82)

Although the pilot study’s scope does not encompass all the aspects which comprise tutoring ‘knowledge,’ ‘impact evidence,’ and ‘curriculum,’ its findings illustrate that standards could have a significant part to play in furthering each of these. Respondents felt personal tutoring ‘knowledge’ would be enhanced by the greater visibility, awareness of best practice (and limiting poor practice) that standards produce thus improving buy-in and recognition from individual academics. They could set boundaries for staff, students and the institution and manage expectations of students. Others believed it would generate ‘impact evidence’ through showcasing and, just as the UK PSF sets professional standards in teaching and the associated results are considered important and recognized, this development similarly, ‘has the potential to raise standards of tutoring practice across the sector.’ Further perceived benefits included promotion of an aspirational approach and potential increased retention and attainment resulting from greater student resilience (with associated HE market and societal benefits). Others believed it would aid with work load and help gauge how local requirements stand up to sector recommendations thus being beneficial at student, practitioner and institutional level. Respondents’ views on the inclusion of specified skills, competencies and behaviors that comprise aspects of the UKAT framework [UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT), 2019] – which can be seen to relate to ‘curriculum’ – is analyzed in a following section.

Four respondents felt standards are abstract, a guide only, not related to day-to-day practice, and are too reductive and rigid for the multi-faceted personal tutor role. Some suggested that any benefit would not be felt if ‘it’s a prescriptive tool.’ Such concern over whether establishing a unifying set of principles represents a reductive and unhelpful ‘one size fits all’ approach to diverse contexts is understandable but does not necessarily negate the need. ‘There is no single correct approach’ to tutoring (Ridley, 2006, p. 132), something that can equally be said of teaching where standards are well established. Referring to the models and provision of personal tutoring in light of the diverse student body, the literature recommends flexibility (Gidman et al., 2000; Sosabowski et al., 2003; Grey and Osborne, 2018) and tailoring to needs, whether they be those of the institution, programme, or student (Atkinson, 2014; Battin, 2014; Grey and Osborne, 2018). If an ethos of ‘freedom within a framework’ is used, professional standards for tutoring can exhibit the same characteristics.

Further valid scrutiny of standards arises from asking what purpose, or purposes, they have. Are they used to assess, evaluate, measure impact, or support? Data gathered from the survey on pre-existing standards pertinent to the personal tutoring role elicited their general use for guidance and regulatory policy rather than delivery thus suggesting a particular interpretation of their purpose. This may also indicate that there is an absence of published institutional ‘standards’ for tutoring which represent a baseline for measuring professional tutoring and advising practice. In United States academic advising, ‘assessment’ is concerned with overall institutional delivery whereas ‘evaluation’ is focused on the performance of an individual academic advisor (Robbins and Zarges, 2011). It is important to emphasize that assessment/evaluation and support/value are not the polar opposites they may seem. It can be argued that the practitioner derives satisfaction from knowing what they are doing and that it is effective and, as a result, feel supported. Moreover, given the importance of the role and impact it can have, a level of scrutiny is to be expected.

Reasons given by some respondents who were skeptical about any benefits which standards would accrue included questioning whether they would improve institutional recognition, ‘Doubtful. We have standards for other practices. They are not associated with recognition in any way.’ Culture change is needed and professional recognition (associated with standards) will not necessarily result in changed practice and better personal tutoring. One respondent felt ‘there are already enough in place’ and fears it would represent an officious task were expressed by others, ‘it would create yet another layer of bureaucratic box-ticking.’ Another believed an additional set is potentially ‘overwhelming.’

What Skills and Competencies Should Populate Professional Standards for Personal Tutoring?

As can be seen, explanations of the need and demand for standards are very much linked to their relevance and meaningfulness which, in turn, can be determined by the skills and competencies which populate them. Previous studies highlight the concerns and gaps in support expressed by tutors and therefore, by implication, suggest the most relevant elements of content for standards. Primary among them are role definition, clarification and induction, boundary setting, and training on pastoral support (Owen, 2002; Ridley, 2006; Stephen et al., 2008; McFarlane, 2016; Hart-Baldridge, 2020; Walker, 2020).

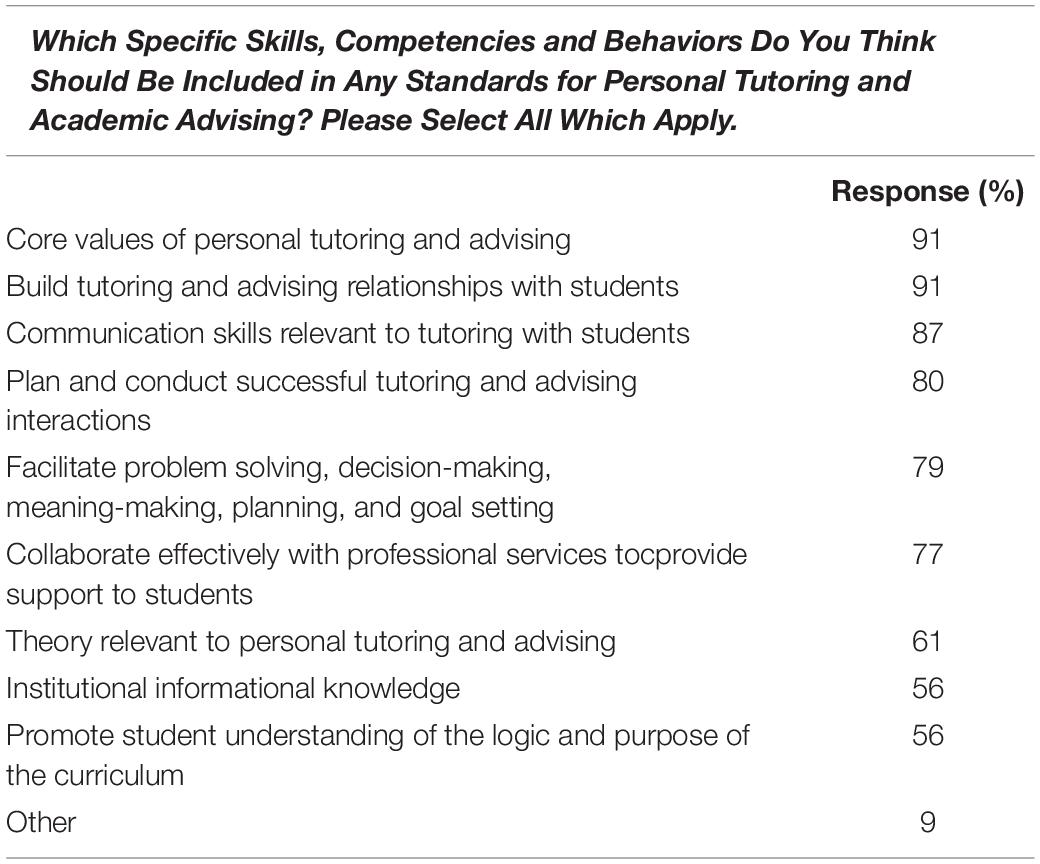

Two United States-based studies identified interpersonal, communication and listening skills as essential competencies (among a wide variety) for entry-level academic advisors (Menke et al., 2018) and advising for the future, helping students navigate systems and empowering students to be the key responsibilities according to faculty advisors (Hart-Baldridge, 2020). Further sources give us a picture of tutoring functions and influence from which skills and competencies can be extrapolated. Personal tutoring facilitates the social integration, through engagement and belonging, upon which student success relies (Beard et al., 2007). The relationship students have with academic staff is most important for nurturing belonging (Thomas, 2012, pp. 17–18). As personal tutors, they can enable students to perceive they are part of an academic community and that this is as important as the academic content of programs (McCary et al., 2011). They are ‘cultural navigators who teach students the language… and help them acclimatize to the academic environment’ (Miller, 2016, p. 45), thus facilitating academic integration (Leach and Wang, 2015). Tutoring is important to personal and professional development (Smith, 2008). These research findings and the examples contained within the National Academic Advising Association’s (NACADA) ‘Core Competencies’ (2017c) informed the development of the UKAT framework [UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT), 2019] which focuses on ‘knowledge,’ ‘skills,’ and ‘understanding’ (see Supplementary Appendix 2). Of the three components, ‘Conceptual,’ ‘Informational,’ and ‘Relational’ (the fourth ‘Professional’ component was added after the survey took place), those descriptors most closely representing skills and competencies (six of the seven ‘Relational’ aspects for example) were included in the survey with participants asked to judge their relevance (see Table 3).

Table 3. Responses to the question “Which specific skills, competencies and behaviors do you think should be included in any standards for personal tutoring and academic advising?”

Survey respondents deemed the UKAT related descriptors as highly relevant and broad agreement with the specified skills, competencies and behaviors is underlined by the fact only 8.8% of respondents chose ‘other.’ In addition, McGill et al. (2020) recently found the views of 17 North American leaders in Advising on the professionalization of academic advising ‘illuminate aspects’ of the UKAT framework (p. 8). The suggestions accompanying the ‘other’ category were ‘CPD, e.g., on mental health training,’ ‘empowering students to take ownership and responsibility’ and ‘coaching.’ Arguably, this small number of additions outlined by participants is covered in the specified descriptors. Further detail in the form of reasons why could be elicited in future study.

The Relevance and Usefulness of Pre-Existing Standards for Personal Tutoring

A number of pre-existing standards can be viewed as pertinent to personal tutoring in HE. The most prominent of these are discussed here: the aforementioned United Kingdom Professional Standards Framework for Teaching and Supporting Learning in HE (UK PSF; Advance HE, 2011), The National Union of Students (NUS) Academic Support Benchmarking Tool (NUS, 2015a) and Charter on Personal Tutors (NUS, 2015b), the National Occupational Standards for Personal Tutoring (NOS) (Learning and Skills Improvement Service, 2013), and NACADA’s ‘Core Competencies’ (2017c).

The UK PSF is nationally recognized and commonly known, perhaps unsurprisingly given it underpins the two awards necessary for teaching in HE, Postgraduate Certificates and HEA Fellowship. Given the assumed undertaking of personal tutoring alongside an academic teaching role, the question of its relevance and sufficiency for the role needs posing. Advance HE’s definition of the UK PSF references ‘HE teaching and learning support’ [my italics] (Advance HE, n.d., online) and ‘supporting learning’ occurs in the title of the standards itself. However, despite the inclusion of the descriptor ‘approaches to student support and guidance’ (Advance HE, 2011, p. 3), this stops short of specific reference to personal tutoring and its associated skills and requirements. The remaining ‘Areas of Activity,’ A1, 2, 3, and 5, relate to teaching. The dimension ‘professional values’ incorporates ‘respect individual learners,’ ‘promote participation … and equality of opportunity for learners’ (Advance HE, 2011, p. 3). Their relevance and sufficiency for tutoring may be a matter of interpretation and depend on one’s view of the complex relationship between teaching and personal tutoring. However, recent studies have identified personal tutoring’s specific requirements and skills, in terms of tutoring approach (signposting, non-directive and directive), levels of support for students (McFarlane, 2016), setting boundaries, effective one-to-one conversations including coaching and supporting ‘at risk’ and ‘vulnerable’ students (Walker, 2020). Such particulars are not covered by the UK PSF and arguably only partially by the other standards considered here, whereas the UKAT framework references connected specific skills under its ‘relational’ component, for example:

‘empathetic listening and compassion … be accessible in ways that challenge, support, nurture, and teach … communicate in an inclusive and respectful manner … motivate, encourage and support students … plan and conduct successful tutoring interactions … facilitate problem-solving, decision-making, planning, and goal setting … collaborate effectively with campus services to provide support to students.’

UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT), 2019, p. 4 (for full list, see Supplementary Appendix 2).

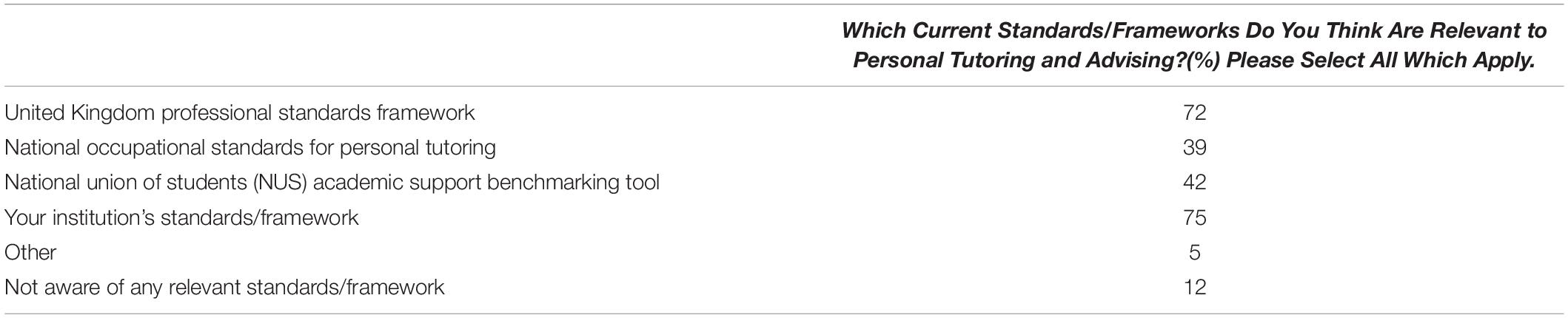

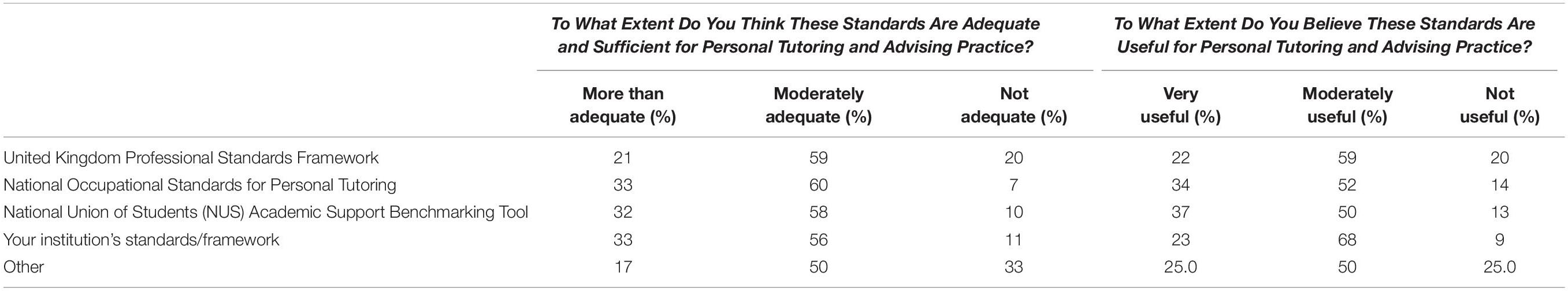

Of the pre-existing standards listed in the pilot study survey, the UK PSF and the standards of respondents’ own institutions were felt to be most relevant to tutoring and advising practice with the NOS and the NUS Academic Support Benchmarking Tool being relevant according to approximately 40% of respondents (see Table 4). However, multiple respondents viewed the UK PSF as not having enough detail with no reference to tutoring theory, skills and competencies. Table 5 shows views of respondents on the adequacy and sufficiency of pre-existing standards. Some explained the inadequacy of the UK PSF for tutoring by making the link with HEA fellowship. In their view, discussing tutoring is not a necessity for conferring HEA fellowship and one cannot achieve beyond Associate Fellow of the HEA based solely on tutoring and advising practice thus making ‘the UK PSF of particularly little use for recognizing effective tutoring/advising practice for professional (primary role) advisors.’

Table 4. Responses regarding the relevance of pre-existing standards to personal tutoring and advising.

Table 5. Responses regarding the adequacy and sufficiency of pre-existing standards to personal tutoring and advising.

Two respondents stated that the UK PSF was used for personal tutoring (as part of overall academic practice) and that their institutional framework reflects this. One respondent felt that the UK PSF’s Area of Activity 4 ‘does prompt me to reflect on my personal tutoring.’ Also, according to another, the UK PSF was utilized when tutoring provided evidence in an HEA fellowship application; however, another felt this evidence can only ever be partial. A further respondent stated that the NUS tool was useful in evidencing academic advising provision with students (the comparison to staff perspectives proving beneficial) and had been used to create a simpler institutional version. Three respondents viewed certain elements of the UK PSF as useful.

Interestingly, one respondent explains the gap of skills and competencies as resulting from a lack of clarity over where personal tutoring should be positioned in relation to professional service functions and teaching duties, issues discussed later in the paper:

‘The United Kingdom professional standards framework and national occupation [sic] standards both have issues in that they don’t specifically conceive or make allowances for personal tutoring as teaching rather than just a professional function, or of it as [a] form of teaching and learning distinct to other classroom learning because it is one-on-one and about self-development.’

The NUS Academic Support Benchmarking Tool (NUS, 2015a) and Charter on Personal Tutors (NUS, 2015b) outline principles of an effective tutoring service and process from a student perspective with the latter arising from a student survey. The charter proposes that tutoring should ‘be adaptable (tailored) to students’ needs,’ ‘support both academic and personal development’ and ‘set mutual expectations [between staff and students]’ (NUS, 2015b, p. 2), therefore going some way to referencing skills and competencies. Interestingly, the charter states, ‘staff should be given full training on being an effective personal tutor’ (NUS, 2015b, p. 2) thus echoing the aforementioned research on staff perceptions.

Tutoring standards at a national level do exist in the form of the comprehensive National Occupational Standards for Personal Tutoring (NOS) (Learning and Skills Improvement Service, 2013). Despite being positioned to apply across sectors, they originated in further education and therefore the extent to which they are used in the HE sector is questionable. Nevertheless, they represent a thorough scoping of the role and are a useful tool for both populating group tutorial content and measuring the impact of tutoring (Lochtie et al., 2018, pp. 123–127, 189–191). However, they are not linked to formal accreditation for qualification to teach in a particular sector. Grey and Osborne’s (2018) effective tutoring principles make some reference to skills in a similar way to the NUS (2015b) charter but are primarily for institutional personal tutoring systems and structure thus representing an evaluation tool for universities.

The NOS and the NUS benchmarking tool had less relevance for respondents (approximately 40%) as shown in Table 4. Reasons given included that, in the views of some, as unrelated to both institutional organization of tutoring and individual tutoring practice, they lack sufficient detail. On the positive side, three respondents believed that that the NUS tool was detailed and useful for tutoring.

With its longer history of professionalization of the role, perhaps the closest existing provision of standards for personal tutor competencies and attributes comes from the United States in the form of NACADA’s three ‘pillars’. The ‘Concept’ (NACADA, 2017a) aims to define the role, the ‘Core Values’ (NACADA, 2017b) describe seven key attributes of the Academic Advisor and the ‘Core Competencies’ (NACADA, 2017c) are organized into three areas: ‘conceptual,’ ‘informational,’ and ‘relational.’ NACADA also endorses the ‘Standards and Guidelines for Academic Advising’ produced by the Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (CAS), a consortium of professional associations in higher education (CAS, 2018). No such national standard is defined by United Kingdom regulatory bodies (Grey and Osborne, 2018, p. 2), such as the Office for Students (OfS).

NACADA’s competency areas mirror the content of training for academic advisors in the United States (King, 2000). While many of the elements of this professional guidance are useful to United Kingdom personal tutoring practice, its full application and sufficiency for the British context can be questioned. The guidance has arisen from the United States context where models of academic advising include those whose entire role is advising whereas in the United Kingdom undertaking personal tutoring alongside academic duties is prevalent. Partly due to its basis in the in loco parentis moral tutor system used in the universities of Oxford and Cambridge since the 16th century, the United Kingdom personal tutor role can have a larger scope than the NACADA classifications (Grey and Osborne, 2018, p. 2). This is exemplified by the fact that, although there is much common content between them and the aforementioned UKAT framework [UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT), 2019], the latter has the additional fourth ‘professional’ component (added after the survey was undertaken) which references supportive environments, student diversity, professional development, and quality assurance [UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT), 2019; p. 3]. NACADA does refer to some of these areas but within their ‘Core Values’ (NACADA, 2017b) rather than as competencies.

Elements of effective personal tutoring systems have been outlined (Gordon and Habley, 2000; Owen, 2002; Morey and Robbins, 2011; Thomas, 2012; McFarlane, 2016) but do not extend to skills and competencies needed. This absence could explain the tacit understanding around the role (Stephen et al., 2008; McFarlane, 2016) and assumption it will ‘come naturally’ (Owen, 2002; Gubby and McNab, 2013) leading tutors to ‘fall back on a variety of misguided historical practices’ (Wootton, 2006, p. 115). Students not initiating contact has been explained by a lack of understanding of the role from their perspective (Malik, 2000).

McGill et al.’s (2020) recent study found the views of 17 NACADA leaders on the professionalization of academic advising reflected, and thus supported, the relevance of many significant aspects of the NACADA, UKAT, and NOS frameworks, in addition to the core values and skills of effective personal tutoring proposed by Lochtie et al. (2018).

Only approximately half of the participants responded to the free text question asking how pre-existing standards were used in personal tutoring which may reinforce the picture of limited specific use. As for the high level of relevance given to ‘your own institution’s standards,’ along with the fact this was not explained by many may highlight a conflation of terminology, specifically, ‘standards’ with ‘guidance’ or ‘policy’ as discussed further later in the paper.

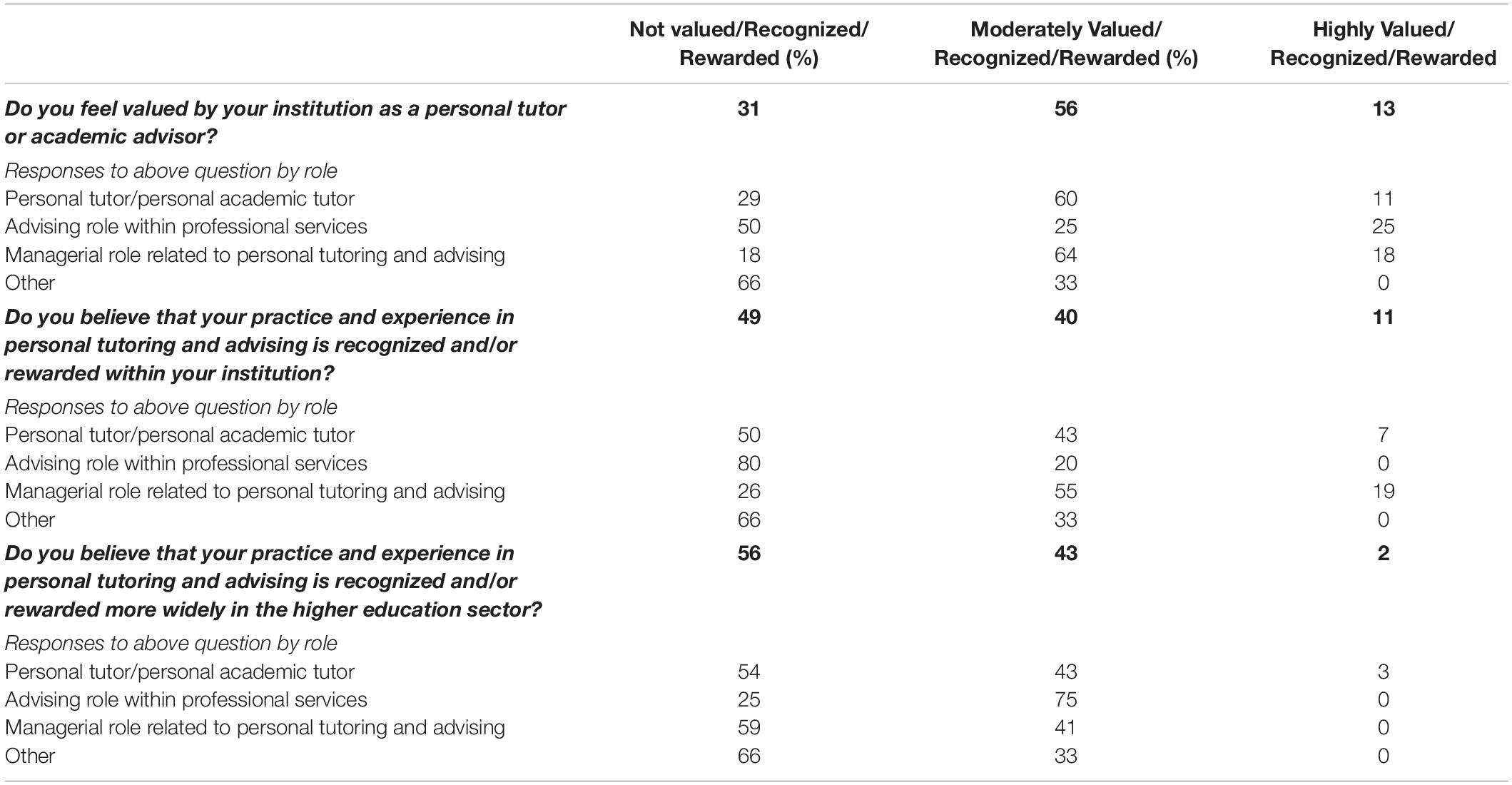

Value, Recognition, and Reward Associated With Professional Standards for Personal Tutoring and Advising

As is the case with the UK PSF for teaching, the standards being discussed here are connected to ‘value,’ ‘reward’ and ‘recognition.’ These terms have broad meanings and their interdependence, as well as the nuanced distinctions between them, need recognizing and an important point of interpretation can be applied to each: whether the perspective is individual or institutional. Moreover, ‘recognition,’ particularly if expressed as ‘professional recognition’ (as distinct from institutional recognition) generally denotes an associated professional qualification. It was expressed as ‘professional recognition’ in the wording of the pilot study’s survey but, potentially, not all respondents made the link between professional recognition and qualification. As mentioned previously, at the time of the survey an associated qualification (through UKAT) was only in the pilot stage and therefore participants will not have been aware of this. The literature and survey responses speak to the connected nature of individual, institutional and sectoral (professional) interpretations.

The literature presents a picture of personal tutoring as invisible ‘other’ work for which there is a lack of reward and recognition. References to personal tutoring in academic job descriptions usually go no further than stating it must be undertaken as a role, with little or no information on skills and competencies given. In the United States, faculty advising ‘has generally been an extra job added on to the teaching work load’ (Raskin, 1979, p. 101), a point made some time ago but Hart-Baldridge’s (2020) recent findings of the principal challenges for faculty advising – ‘advising as an isolated initiative,’ ‘unclear expectations,’ and ‘workload (in)equity’ (pp. 15–16) – suggest that the situation has not radically changed.

A perception of under-valued, under-recognized, and under-rewarded personal tutoring at both institutional and sector level emerged from the survey findings (see Table 6). This was particularly marked at the institutional level amongst those in an advising role within professional services and is in contrast to the value which students and individual practitioners themselves place on the role. There is ‘no reward or acknowledgment’ and it is ‘viewed as a burden rather than a privilege.’ Regarding sectoral recognition, ‘I don’t think there is enough national focus on this part of the role.’ Tutors desire institutional recognition (Luck, 2010) and its absence, combined with excessive workloads and ineffectual staff development, explains issues with personal tutoring delivery, rather than this being the fault of students or tutors themselves (Huyton, 2009). Students believe that for effective tutoring to take place, it ‘should be recognized in staff reward and recognition schemes’ (NUS, 2015b, p. 2).

Tutors’ reference to colleagues’ mixed commitment to the role in comparison to their other duties (Stephen et al., 2008; Walker, 2020) implies varied individual value, which, in turn, could be explained by varied institutional value. Personal tutoring should be valued by institutions at the same level as teaching, research and other scholarly activities (Robbins, 2012; Battin, 2014; McFarlane, 2016) if tutors are to prioritize it and believe that it will enhance their careers (Trotter, 2004; Stephen et al., 2008). Advisors must know training is an institutional priority, be offered incentives and if it is not evident, they may be resistant to engage and prefer to spend time on activities linked to their own professional recognition (King, 2000). The United States experience tells us that academic advisors work harder when they are appreciated and rewarded in meaningful ways for their work and positive reinforcement promotes natural enjoyment which results in good performance (McClellan, 2016). Assessing and evaluating personal tutoring sends the message that it is important and valued (Cuseo, 2015). The lack of this at most institutions (Creamer and Scott, 2000; Smith, 2008), possibly due to the challenge posed by tutoring’s complexity (Lynch, 2000; Smith, 2008; Anderson, 2017), reinforces reduced value.

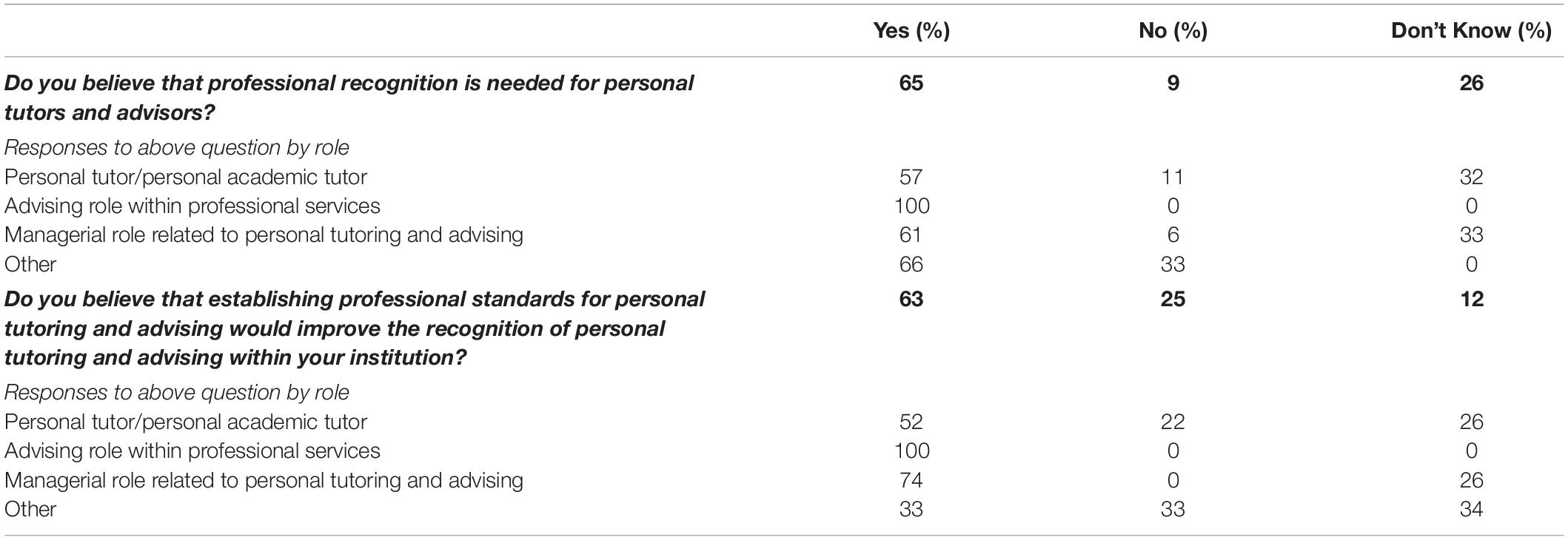

With almost two-thirds of respondents answering positively, a theme of professional recognition being wanted and needed emerged (see Table 7). However, with almost a third of overall participants responding ‘don’t know,’ some uncertainty is evident and differences of views by role type emerged with 100% of those in an advising role within professional services believing it is needed and would improve institutional recognition. Diverse opinions on this topic were also expressed. The majority of survey participants conveyed the positive effects they believed professional recognition would have. This perception was expressed in terms of greater motivation and perceived value, a raised profile for tutoring, and parity of esteem with the other duties of academics, primarily teaching and research. They believed specific skills are involved and therefore the role should be recognized and rewarded. According to one respondent, tutors should be ‘recognized for their impact in this field [pedagogy].’ Another two participants felt that standards would incentivise practitioners to perform this role to a higher level, help address where the role wasn’t being done at all and that industry responds to professional recognition.

Table 7. Responses regarding the need for professional recognition of personal tutoring and advising.

Those who were not sure or didn’t think professional recognition of tutoring was needed stated that teaching excellence covers it already, with one respondent uncertain whether it should be ‘separated out’ and asking ‘Perhaps the UK PSF should just have more emphasis on it?’ Participants referenced tutoring’s subordinate status, described variously as ‘a minor part … a bolt on’ and a ‘hybrid’ role, which meant few would see it as something which needs recognition. Interestingly, this contrasts to the positive responses arguing that recognition is precisely what is needed to address tutoring’s inferior standing. Such recognition is arguably the stimulus for overcoming this barrier to progress, a reasoning which is echoed in the literature reviewed. Despite the apparent greater focus on professionalization in the United States, the comparable role of ‘faculty advisor’ seems to face similar issues, with a lack of reward and recognition resulting in academics giving it less importance (Reinarz, 2000). This may be explained by the fact no professional qualification is offered to faculty advisors, although Master’s courses in Advising do exist which mainly primary role advisors undertake. Similarly, reward and recognition is more prevalent among the latter with academic faculty advisors rarely rewarded or encouraged (McClellan, 2016). Future research could focus further on the correlation between the relative status of tutoring in the overall role of an ‘academic’ and other perceptions, for example the purpose and importance of tutoring.

In addition to the raised profile and importance in common with previous answers, further reasons for positive responses included demonstration of the associated skill set and providing a benchmark. The statement ‘Tutoring has a unique combination of skills and competencies so should have [its] own framework of qualification clearly!’ provides a further contrast to the aforementioned views (in response to this and other questions) of tutoring as a corresponding or ancillary activity to teaching.

Perhaps inevitably, variations between how respondents felt about management within their respective institutions on this matter were evident. The view from one participant that ‘senior management of my institution see a clear link between recognition of personal tutoring and the ability to use [this] as evidence for TEF submissions (in same way as HEA fellowship is used as evidence) to advance TEF aspirations’ clearly contrasts with another: ‘management wouldn’t care – only if it affected recruitment and reputation.’ However, one could argue that the TEF is one such determinant of recruitment and reputation.

Limitations of the Study

This study acts as a pilot, in part due to a number of limitations. This section discusses these limitations as they pertain to the study in its entirety, and offers several general suggestions for further research. In the following conclusion, implications of the findings on the various aspects of the study are presented and further, more specific opportunities for research proposed.

Fifty-seven responses were received but these came from only 26 different United Kingdom higher education institutions (HEIs). Of the eight universities having multiple respondents, responses from three of these accounted for 39% of total responses thus potentially skewing the results. However, analyzing the responses to the key question of whether professional standards for personal tutoring and advising are necessary with responses from these institutions excluded makes no significant difference (varying by 3.4%). The initial distribution of the survey to the members of UKAT and the fact participants were self-selecting meant respondents were likely to be those most engaged in personal tutoring and invested in improving practice. Therefore, both the claim that the institutions involved were representative of United Kingdom universities and that the individual respondents were representative of the range of views on personal tutoring within his or her institution can be contested.

Given the diversity of views found among the relatively limited research population, work to examine what informs such perceptions would seem to be necessary. Therefore, future research could explore the latent variables in the perceptions of tutors about the role which may rely on a larger research population and potentially wider ranging survey.

The content of the questions was based on the issues most evident from the literature. The high percentage of positive responses to these suggest most respondents aspire to improve the profile and practice of personal tutoring identified in previous research thus reflecting the membership of UKAT. The questions’ formats were designed specifically for this study, with the inclusion of free text ‘explain your answer’ options linked to closed, scaling/ranking and multiple choice questions intended to maximize meaningfulness through qualitative data complementing quantitative data. Explanations were optional not compulsory and had completion rates of between 60 and 88% except for one question whose 49% completion rate is potentially explained due to it asking for explanations only from those who use existing standards in personal tutoring practice. It is argued that this gleaned significant findings which are of use and interest to those engaged in personal tutoring and the sector more widely. However, potentially other data collection methods, such as focus groups, could have extended this significance.

Moreover, the study is potentially restricted by the relatively limited response rate and short research period. However, arguably, the survey reached those most engaged in personal tutoring practice who were thus best placed to answer. In addition, these respondents were from across the sector employed in both modern and ‘red brick’ HEIs and therefore a reasonably wide evidence base was achieved. Briefly referenced in responses, the absence of student perspectives on these standards is a further specific limitation of the study, particularly in light of their lack of understanding of the role (Malik, 2000), and incorporating such would be a useful extension and develop the work undertaken by the NUS survey which led to its Charter on Personal Tutors (NUS, 2015b).

Conclusion – Implications for Policy, Research and Practice

Based on theory and data, support for the establishment, and relevance, of bespoke standards for personal tutoring and advising in the United Kingdom HE context – in particular as represented by the new UKAT framework [UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT), 2019] – is evident. The review of relevant literature undertaken highlights this need and is underlined by the findings of the pilot study which surveyed a selection of those undertaking, and being responsible for, these roles across the sector. Justifications for this convey that such a development would help positively address the fundamental tensions and contradictions of personal tutoring in the current HE climate across individual, institutional, and sector levels, namely standardization, professionalization, recognition (both ‘institutional’ and ‘professional’ through accreditation), status, and value. It is important to acknowledge that this demand was not felt across all survey respondents but was in the majority. Many questioned the relevance, adequacy and usefulness of pre-existing sectoral standards for personal tutoring, therefore reinforcing the overall conclusion, while some argued the opposite and raised issues around the effectiveness of standards generally.

The Embedding of Standards and Professional Recognition

As previously mentioned, the NACADA (2017c) ‘Core Competencies,’ informed the development of the UKAT framework [UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT), 2019], included in Supplementary Appendix 2, and Professional Recognition Scheme. At the time of the study the former was newly published and the latter in pilot form. In line with the conceptions of the role highlighted by this study, these standards aim to serve both the personal tutor undertaking the role as part of an academic post and the professional personal tutor or advisor. An evaluation of the usefulness, value, effectiveness, and impact of this framework (and the newly associated qualification) would be a worthwhile future research activity. The matters professionals feel are most pertinent to standards as provided by this study – namely clarity of purpose, flexibility, practical application, incorporation of guidance and links to meaningful recognition and value – could be used as criteria in such an assessment. Student outcomes would be a further important criterion for inclusion here.

The ‘Meaningfulness’ of Standards

Care needs to be taken to ensure standards are meaningful to the practitioner, institutions, and the sector. Inclusion of relevant skills, competencies and behaviors provides an important way of achieving this. The majority view in the pilot study that personal tutoring is a discrete exercise with a particular skill set aligns with previous research (McFarlane, 2016; Walker, 2020). The broad functions of personal tutoring, which imply the skills required, have been extrapolated from the literature. The survey goes some way to assessing and validating the new UKAT framework [UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT), 2019] through respondents’ corroboration of the relevance of specific skills and behaviors contained within it, for example, communication skills, problem solving, goal setting, and collaboration with professional services. Further assessment could be provided by future research into the application of the framework and impact on practice.

Other important ways of affording ‘meaningfulness,’ resulting in practitioners valuing the standards themselves, are highlighted by the literature and this pilot study. While the concern which emerged from the findings that standards and frameworks equate to ‘one size fits all’ is a legitimate one, perhaps particularly so in relation to personal tutoring’s diverse contexts, it is overcome by flexibility and relevance. The diversity of teaching contexts and yet existence and use of established associated professional standards underlines this.

The assertion expressed by a minority in the study, that producing more standards will not have the desired impact and, by implication, meaning, can be contested. Associated with this view, the call for ‘guidance’ rather than ‘standards’ by some respondents may highlight the negative association of the latter caused by previous experiences or a misunderstanding of terminology or purpose. Standards, if linked to nationally recognized qualification, can represent a minimum ‘threshold’ or ‘benchmark’ for practice and therefore have a wider purpose than ‘guidance.’ Arguably, standards can include ‘guidance’ within them but ‘guidance’ in itself does not represent standards. Indeed, when conceived of as a benchmark, as the UK PSF is for teaching (Turner et al., 2013, p. 50), assessment against such standards would convey a minimum level of good practice. At the time of the survey, professional qualification linked to the UKAT framework was only in the pilot stage, but now that a recognition scheme has been developed, its effectiveness in providing a benchmark merits further research.

Value, Recognition, and Reward

In terms of the value, recognition, and reward with which personal tutoring standards could be associated, to some extent the responses reflected the complex definitions of these, in addition to the different, although interdependent, perspectives of the individual, institutional and sectoral. While space does not allow for a detailed discussion of these nuances here, a number of interesting themes emerged.

While the skepticism from some about reward systems related to tutoring is not new (Arnold et al., 1998; Deci et al., 2001; Lawler, 2008; McClellan, 2016), specific claims that standards would not improve, or are not associated with, institutional recognition emerged. This can be challenged through appreciating the parallels with the UK PSF and HEA fellowship (outlined previously) which are recognized in institutional metrics. Fellowship provides a required benchmark and thus arguably instigates cultural change, and an associated change in the practice of teaching and learning. Therefore, using personal tutoring standards such as the UKAT framework [UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT), 2019], as proposed by this study, offers a corresponding development for the important work of tutoring and advising.

A crucial differentiator would seem to be recognition conceived of as professional recognition and associated qualification, specifically through an evidence-based assessment mapped to the standards. As a consequence of such sectoral recognition, improvement in institutional recognition and the associated benefits for personal tutoring would follow. Greater commitment would transpire, the survey response: ‘without professional recognition tutors will not seek to improve their practice’ here echoing the prioritization cited as a benefit by King (2000) and Stephen et al. (2008). Those respondents’ view that no positive effect will be felt could suggest that not all made the key link between standards and professional qualification (and thus professional recognition). Future study could clearly emphasize evidence-based retrospective assessment against personal tutoring standards (leading to a professional recognition qualification), which UKAT has now developed, and investigate the effect on improving quality and practice.

Further research comparable to past work which investigated the impact on practice from teaching professional standards/accreditation, primarily the UK PSF and associated HEA fellowship (Turner et al., 2013; Botham, 2018; Spowart et al., 2019), would be valuable. The questioning of the correlation between standards and impact evident from this work does not justify halting the endeavor of embedding personal tutoring standards. Indeed, as respondents in the pilot study expressed, any future assessment of impact can only take place if these standards are actually utilized.

The fact equivalent assessments of teaching standards ‘suggest a split in sector opinion as to whether engagement with the UK PSF benefits learning and teaching practice’ (Botham, 2018, p. 166) and provide ‘mixed evidence’ (Botham, 2018, p. 166) has not resulted in rejection of standards and affords lessons which can be learned for their personal tutoring counterpart. Among these is a key finding from Spowart et al. ’s (2019) cross-institutional study on how HEA fellowship impacts on participants’ teaching development: ‘caution must be taken to ensure that the professional development opportunities offered by [HEA] accreditation schemes are fully realized’ (p. 1299). More positively, Turner et al.’s (2013) research across eight HEIs found the impact of the UK PSF ‘has been significant in most institutions and for many institutional staff’ (p. 50) and is used in a ‘myriad of ways’ (p. 50) including

‘to underpin initial and continuing professional development, to influence learning and teaching and related strategies, to act as a national benchmark, to provide an aspiration for staff, to underpin promotion and probation policies, and to change the language of learning and teaching.’

(p. 50)

These echo the potential benefits both expressed by many participants in this study and inferred from the literature in the context of personal tutoring and further reinforce the argument for their adoption.

The Relationship Between Teaching and Personal Tutoring

In the context of examining the relevance of teaching standards, this study contributes to an under-researched area: the important question of the relationship between personal tutoring and teaching. The complexity of this relationship is reflected in the diverse opinions which were expressed, for example, the minority view of tutoring as a marginal or hybrid role subordinate to teaching, contrasting with the more commonly held view of its significance. The former view, expressed by those who believed professional recognition of tutoring is not necessary, can be contested by the fact that, although personal tutoring is not explicitly referenced in the TEF, it contains criteria referring to personalized learning and student support to which personal tutoring directly relates. Since evidence from personal tutoring practice could be used to support TEF claims against these criteria then, arguably, it is sufficiently important and separate professional recognition is a necessity.

A further relationship, that between tutoring as part of an academic position and a separate ‘professional tutor’ role (mirroring ‘faculty’ and ‘primary role’ advisors in the United States), was highlighted by the findings. This was exemplified by an additional view which emerged, that tutoring standards are necessary but would need to situate the role as a mode of teaching, rather than as a separate ‘professional tutor’ activity. Building on this research, and the small number of other previous studies which highlight and discuss these relationships (Stork and Walker, 2015, pp. 7–9; Lochtie et al., 2018, pp. 9–14), would be a fruitful avenue for future work.

The increasing importance of personal tutoring at sectoral, institutional, individual practitioner and student level has not produced the requisite advance in professionalization. The adoption of discrete professional standards for this work would be a notable step toward resolving this unsatisfactory situation. While acknowledging the limitations of this study, and in combination with the literature reviewed, it is argued that the embedding of relevant personal tutoring standards, such as those represented by the new UKAT framework [UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT), 2019], is needed and justified through the associated improvements in support, development and recognition it could provide for this most crucial of roles.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Manchester Metropolitan University Business and Law Research Ethics and Governance Committee. Written informed consent was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr. David Grey for his help in administering the survey.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.531451/full#supplementary-material

References

Advance HE (2011). UK Professional Standards Framework for Teaching and Supporting Learning in Higher Education. Available online at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/downloads/UK%20Professional%20Standards%20Framework.pdf (accessed August 22, 2019).

Anderson, H. D. S. (2017). Assessment: It is A Process. Available online at: https://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Academic-Advising-Today/View-Articles/Assessment-It-is-a-Process.aspx (accessed August 22, 2019).

Arnold, K., Fisher, C., and Glover, R. (1998). Satisfaction with academic advising: developing a measurement tool. Qual. High. Educ. 4, 247–256. doi: 10.1080/1353832980040305

Atkinson, S. P. (2014). Rethinking Personal Tutoring Systems: The Need to Build on a Foundation of Epistemological Beliefs. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Simon_Atkinson3/publication/271191988_Rethinking_personal_tutoring_systems_the_need_to_build_on_a_foundation_of_epistemological_beliefs/links/54bf977f0cf28ce68e6b67a1.pdf?origin=publication_list (accessed August 22, 2019).

Battin, J. R. (2014). Improving academic advising through student seminars: a case study. J. Crim. Justice Educ. 25, 354–367. doi: 10.1080/10511253.2014.910242

Beard, C., Clegg, S., and Smith, K. (2007). Acknowledging the affective in higher education. Br. Educ. J. 33, 235–252. doi: 10.1080/01411920701208415

Botham, K. A. (2018). The perceived impact on academics’ teaching practice of engaging with a higher education institution’s CPD scheme. Innovat. Educ. Teach. Int. 5, 164–175. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2017.1371056

Bowden, J. (2008). Why do nursing students who consider leaving stay on their courses? Nurse Res. 15, 45–58. doi: 10.7748/nr2008.04.15.3.45.c6456

Braine, M. E., and Parnell, J. (2011). Exploring student’s perceptions and experiences of personal tutors. Nurse Educ. Today 31, 904–910. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.01.005

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

CAS (2018). Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education CAS Standards for Academic Advising. Available online at: http://standards.cas.edu/getpdf.cfm?PDF=E864D2C4-D655-8F74-2E647CDECD29B7D0 (accessed August 22, 2019).

Creamer, E. G., and Scott, D. W. (2000). “Assessing individual advisor effectiveness” in Academic Advising: A Comprehensive Handbook, eds V. N. Gordon and W. R. Habley (San Francsico, CL: Jossey-Bass).

Cuseo, J. (2015). Assessing Adviser Effectiveness. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277711351 (accessed August 22, 2019).

Deci, E., Koestner, R., and Ryan, R. (2001). Extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation in education: reconsidered once again. Rev. Educ. Res. 71, 1–26. doi: 10.3102/00346543071001001

Drake, J. K. (2011). The role of academic advising in student retention and persistence. About Campus, 16, 8–12. doi: 10.1002/abc.20062

Ghenghesh, P. (2018). Personal tutoring from the perspectives of tutors and tutees. J. Fur. High. Educ. 42, 570-584

Gidman, J., Humphreys, A., and Andrews, M. (2000). The role of the personal tutor in the academic context. Nurse Educ. Today 20, 401–407. doi: 10.1054/nedt.2000.0478

Gordon, V.N., and Habley, W.R. (2000). “Training, Evaluation, and Recognition,” in Academic Advising: A Comprehensive Handbook eds V. N. Gordon and W. R. Habley. San Francisco, CL: Jossey-Bass.

Grey, D., and Lochtie, D. (2016). Comparing Personal Tutoring in the UK and Academic Advising in the US. Available online at: www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Academic- Advising-Today/View-Articles/Comparing-Personal-Tutoring-in-the-UK-and-Academic-Advising-in-the-US.aspx (accessed August 22, 2019).

Grey, D., and Osborne, C. (2018). Perceptions and principles of personal tutoring. J. Fur. High. Educ. 42, 1–15.

Gubby, L., and McNab, N. (2013). Personal tutoring from the perspective of the tutor. Capture 4, 7–18.

Habley, W. R. (2009). Academic advising as a field of inquiry. NACADA Journal, 29, 76–83. doi: 10.12930/0271-9517-29.2.76

Hart-Baldridge, E. (2020). Faculty advisor perspectives of academic advising. NACADA Journal, 40, 10–22. doi: 10.12930/nacada-18-25

Higher Education and Research Act (2017). (c.25). London: TSO. Available online at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2017/29/pdfs/ukpga_20170029_en.pdf (accessed August 22, 2019)

House of Commons Public Accounts Committee (2008). Staying the Course: The Retention of Students on Higher Education Courses. London: HMSO.

Huyton, J. (2009). Significant personal disclosure: exploring the support and development needs of HE tutors engaged in the emotion work associated with supporting students. J. Learn. Dev. High. Educ. 1, 1-18

King, M. C. (2000). “Designing Effective Training for Academic Advisors,” in Academic Advising: A Comprehensive Handbook eds V. N. Gordon and W. R. Habley and Associates (San Francisco, CL: Jossey-Bass).

Larson, J., Johnson, A., Aiken-Wisniewski, S. A., and Barkemeyer, J. (2018). What is academic advising? An application of analytic induction. NACADA J. 38, 81–93. doi: 10.12930/0271-9517-38.2.81

Lawler, E. E. (2008). Talent: Making People Your Competitive Advantage. San Francisco, CL: Jossey-Bass.

Leach, R. B., and Wang, T. R. (2015). Academic advisee motives for pursuing out-of-class communication with the faculty academic advisor. Commun. Educ. 64, 325–343. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2015.1038726

Learning and Skills Improvement Service (2013). Personal Tutoring National Occupational Standards. Available online at: https://www.excellencegateway.org.uk/content/eg6176 (accessed August 22, 2019).

Lochtie, D., McIntosh, E., Stork, A., and Walker, B. W. (2018). Effective Personal Tutoring in Higher Education. Northwich: Critical Publishing.

Luck, C. (2010). Challenges faced by tutors in higher education. Psychodyn. Pract. 16, 273–287. doi: 10.1080/14753634.2010.489386

Lynch, M. (2000). “Assessing the effectiveness of the advising program,” in Academic Advising: A Comprehensive Handbook, eds V. N. Gordon and W. R. Habley (San Francisco, CL: Jossey-Bass).

Malik, S. (2000). Students, Tutors and Relationships: the ingredients of a successful student support scheme. Med. Educ. 34, 635-641.

McCary, J., Pankhurst, S., Valentine, H., and Berry, A. (2011). A Comparative Evaluation of the Roles of Student Adviser and Personal Tutor in Relation to Undergraduate Student Retention, Final Report. Cambridge: Anglia Ruskin University.

McClellan, J. (2016). Reward Systems and Career Ladders for Advisors: Beyond Foundations: Developing as a Master Academic Advisor. San Francisco, CL: Jossey-Bass, 225-245.

McFarlane, K. J. (2016). Tutoring the tutors: supporting effective personal tutoring. Active Learn. High. Educ. 17, 77–89. doi: 10.1177/1469787415616720

McGill, C. M., and Nutt, C. (2016). Challenges for the Future: Developing as a Profession, Field and Discipline in Beyond Foundations: Developing as a Master Academic Advisor. San Francisco, CL: Jossey-Bass, 351-361.

McGill, C. M. (2019). The professionalization of academic advising: a structured literature review. NACADA J. 39, 89–100. doi: 10.12930/nacada-18-015

McGill, C. M., Ali, M., and Barton, D. (2020). Skills and competencies for effective academic advising and personal tutoring. Front. Educ. 5:135. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00135

Menke, D., Stuck, S., and Ackerson, S. (2018). Assessing advisor competencies: a delphi method study. NACADA J. 38, 2–21.

Mountford-Zimdars, A. K., Sanders, J., Jones, S., Sabri, D., Moore, J., and Higham, L. (2015). Causes of Differences in Student Outcomes (Report). Higher Education Funding Council for England. Available online at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/23653/1/HEFCE2015_diffout.pdf (accessed August 22, 2019).

Miller, M. A. (2016). Building Upon the Components of Academic Advising to Facilitate Change in Beyond Foundations: Developing as a Master Academic Advisor. San Francisco, CL: Jossey-Bass.

Morey, S., and Robbins, S. (2011). Final report: Comparing and Evaluating the Impacts on Student Retention of Different Approaches to Supporting Students Through Study Advice and Personal development. Available online at: http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/resources/detail/what-works-student-retention/Reading_Oxford_Brookes_What_Works_Final_Report (accessed August 22, 2019).

Mynott, G. (2016). Personal tutoring: positioning practice in relation to policy. Innovat. Pract. 10, 103–112.

NACADA (2017a). Concept of Academic Advising. Available online at: https://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Pillars/Concept.aspx (accessed August 22, 2019).

NACADA (2017b). Core Values of Academic Advising. Available online at: https://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Pillars/CoreValues.aspx (accessed August 22, 2019).

NACADA (2017c). Core Competencies of Academic Advising. Available online at: https://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Pillars/ CoreCompetencies.aspx (accessed August 22, 2019).

National Audit Office (2007). Staying the Course: The Retention of Students in Higher Education. London: HMSO. Available online at: http://www.nao.org.uk/idoc.ashx?docId = f2e92c15–d7cb–4d88–b5e4–03fb8419a0d2&version=–1 (accessed August 22, 2019).

NUS (2015a). Academic Support Benchmarking Tool. Available online at: www.nusconnect.org.uk/ resources/academic- support- benchmarking- tool (accessed August 22, 2019).

NUS (2015b). NUS Charter on Personal Tutors@NUS Connect. Available online at: https://www.nusconnect.org.uk/resources/nus-charteron-personal-tutors (accessed August 22, 2019)

OfS (2018). Securing Student Success: Regulatory Framework for Higher Education in England. Bristol: OfS.

OfS (2019a). Access and Participation Dashboard. Available online at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/data-and-analysis/access-and-participation-data-dashboard/ (accessed August 22, 2019).

OfS (2019b). New Data Reveals University Performance on Access and Student Success. Available online at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/press-and-media/new-data-reveals-university-performance-on-access-and-student-success/ (accessed August 22, 2019).

Owen, M. (2002). ‘Sometimes you feel you’re in niche time’: the personal tutor system, a case study. Active Learn. High. Educ. 3, 7–23. doi: 10.1177/1469787402003001002

Pellagrino, J. L., Snyder, C., Crutchfield, N., Curtis, C. M., and Pringle, E. (2015). Leveraging institutional knowledge for student success: promoting academic advisors. Perspect. Pol. Pract. High. Educ. 19, 135–141. doi: 10.1080/13603108.2015.1081302

Raskin, M. (1979). Critical issue: faculty advising. Peabody J. Educ. 56, 99–108. doi: 10.1080/01619567909538228

Reinarz, A.G. (2000). “Delivering Academic Advising; Advisor Types,” in Academic Advising: A Comprehensive Handbook eds V. N. Gordon and W. R. Habley (San Francisco, CL: Jossey-Bass), 210-219.

Ridley, P. (2006). “Who’s looking after me? – Supporting new personal tutors,” in Personal Tutoring in Higher Education, eds L. Thomas and P. Hixenbaugh (Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books), 127-136.

Rivis, V. (1996). Personal Tutoring and Academic Advice in Focus. London: Higher Education Quality Council.

Robbins, R. (2012). Everything you have always wanted to know about academic advising (Well, Almost). J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 26, 216–226. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2012.685855

Robbins, R., and Zarges, K. M. (2011). Assessment of Academic Advising: A Summary of the Process. NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources. Available online at: https://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Assessment-of-academic-advising.aspx (accessed August 22, 2019).

Shaffer, L. S., Zalewski, J. M., and Leveille, J. (2010). The professionalization of academic advising: where are we in 2010? NACADA J. 30, 66–77. doi: 10.12930/0271-9517-30.1.66

Smith, E. M. (2008). Personal Tutoring: An Engineering Subject Centre Guide. Heslington: Higher Education Academy.

Sosabowski, M. H., Bratt, A. M., Herson, K., Olivier, G. W. J., Sawers, R., Taylor, S., et al. (2003). Enhancing quality in the M.Pharm degree programme: optimisation of the ersonal tutor system. Pharm. Educ. 3, 103–108. doi: 10.1080/1560221031000121942

Stephen, D. E., O’Connell, P., and Hall, M. (2008). ‘Going the extra mile’, ‘fire-fighting’, or laissez-faire? Re-evaluating personal tutoring relationships within mass Higher Education. Teach. High. Educ. 13, 449–460. doi: 10.1080/13562510802169749

Spowart, L., Winter, J., Turner, R., Burden, P., Botham, K. A., Muneer, R., et al. (2019). ‘Left with a title but nothing else’: the challenges of embedding professional recognition schemes for teachers within higher education institutions. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 38, 1299–1312. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2019.1616675

Stork, A., and Walker, B. (2015). Becoming an Outstanding Personal Tutor: Supporting Learners Through Personal Tutoring and Coaching. Northwich: Critical Publishing.

Thomas, L. (2012). What Works? Student Retention and Success Programme (Report). York: Higher Education Academy. Available online at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/building-student-engagement-and-belonging-higher-education-time-change-final-report (accessed August 22, 2019).

Thomas, L., Hill, M., O,Mahony, J., and Yorke, M. (2017). What Works 2? Supporting Student Success, Strategies for Institutional Change (Report). York: Higher Education Academy. Available online at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/supporting-student-success-strategies-institutional-change (accessed August 22, 2019).

Thomas, L. (2018). “Foreword,” in Effective Personal Tutoring in Higher Education eds D. Lochtie, E. McIntosh, A. Stork, and B. W. Walker (Northwich: Critical Publishing).

Trotter, E. (2004). Personal Tutoring: Policy v Reality of Practice. Education in a Changing Environment. Conference Proceedings. Salford: University of Salford.

Turner, N., Oliver, M., McKenna, C., Hughes, J., Smith, H., Deepwell, F., et al. (2013). Measuring the Impact of the UK Professional Standards Framework for Teaching and Supporting Learning (UK PSF). York: HEA.

UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT) (2019). The UKAT Professional Framework for Advising and Tutoring. Available online at: https://www.ukat.uk/professional-development/professional-framework-for-advising-and-tutoring/ (accessed August 22, 2019).

NOS (2019). Ukstandards.org.uk Repository for All Approved National Occupational Standards. Available online at: https://www.ukstandards.org.uk/ (accessed August 22, 2019).

UUK/NUS (2019). Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Student Attainment at UK Universities: #ClosingTheGap (Report). London: UUK.

Walker, B. W. (2020). Tackling the personal tutoring conundrum: a qualitative study on the impact of developmental support for tutors. Active Learn. High. Educ. 21, 167-172.

Webb, O., Wyness, L., and Cotton, D. (2017). Enhancing Access, Retention, Attainment and Progression in Higher Education. Available online at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/resources/enhancing_access_retention_attainment_and_progression_in_higher_education_1.pdf (accessed August 22, 2019).

Keywords: personal tutoring, academic advising, professional standards, professional development, professional recognition

Citation: Walker BW (2020) Professional Standards and Recognition for UK Personal Tutoring and Advising. Front. Educ. 5:531451. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.531451

Received: 31 January 2020; Accepted: 02 September 2020;

Published: 14 October 2020.

Edited by:

Oscar Van Den Wijngaard, Maastricht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Craig M. McGill, University of South Dakota, United StatesMark Te Wierik, Windesheim University of Applied Sciences, Netherlands

Copyright © 2020 Walker. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ben W. Walker, Yi53YWxrZXJAbW11LmFjLnVr

Ben W. Walker

Ben W. Walker