- 1Faculty Health, Education, Medicine, Social Care, Anglia Ruskin University, Chelmsford, United Kingdom

- 2Faculty Health, Education, Medicine, Social Care, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Tutoring in one form or another is a consistent feature in the higher education learning experience. However, the tutorial relationship involves an intricate mix of intra and interpersonal dynamics which influence short and long-term learning. In this paper, work from a phenomenological study of distance learning students provides transferable insights about the immediate and lasting impact of the tutorial relationship. Ideas from Heideggarian hermeneutic phenomenology are translated to the context of contemporary higher education to establish how achieving a sense of being-with has affective implications to help students to strengthen resilience and the capacity to challenge, confirm and develop confidence in their new learning, thinking and actions. The discussion introduces and unravels the nature of academic care in relation to working with learner vulnerability to enhance ability. Re-conceptualizing the tutorial as a form of academic care can provide support and security for learners at a time of unsettlement without lessening their autonomy. We argue that by creating an atmosphere of academic care, learners are empowered and inspired to be courageous and curious, both in the immediate and longer-term. The discussion refocuses the tutorial relationship through ideas and applied strategies for successful future-facing tutoring practices, without major upheaval to the existing operational tutoring infrastructure within the HEI.

Introduction

The context of this paper is informed by an empirical study which explored the lived experience of adult distance learning (Goldspink, 2017). Using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) (Smith et al., 2009), the alumni from a specific part-time, undergraduate course voiced their distance learning stories via semi-structured telephone interviews. In orientation, IPA is encapsulated as inductive, interrogative, and idiographic approach (Smith, 2004). The intention is to generate novel ways of understanding pre-existing ways of thinking and doing, and to open fresh insights about how the phenomenon as it is actually experienced. To explore the data, initial descriptive analysis progressed toward abstract and detailed conceptual interpretations, whilst remaining grounded in the participants' words, thus revealing “the extraordinary in the ordinary, the strange in the commonplace; the hidden in the obvious” (McNamara, 2005, p. 697).

In the study, the participants detailed narrative accounts convey various notions of care, which resonated specifically within the academic tutorial. Despite never meeting their tutors in person during their course, their descriptions included “caring people”; “they (tutors) cared about us and the course” and feeling “cared for.” The participant dialogue exposes a deeper understanding of the qualities pertaining to “caring” in the tutors' concern and attention as academic caregivers, but significantly, associated with empowerment because the perceived caring actions of their tutors did not remove or diminish the learner's own responsibility in their learning (Rogers, 1959).

It was at the person-to-person level that the participants perceived the tutors to be with their learning: “they understood what it was all about for me.” In this way, academic care is directed to the experience of learning and what this may mean for the individual learner. The examples of academic care referred to by the participants are all the more interesting because the learner-tutor contact relied on modes of communication that were either voice-led (telephone/skype) or employed the written word (emails/discussion boards). Care is often perceived as parallel with physical presence and action, for example ensuring that the classroom environment is conducive for learning or in the arrangements for face-to-face tutorials. However, this study suggests that care is more than sharing the same physical space as each other, and it is from here our discussion begins. First, we start by discussing what the academic tutorial care might be, and we then consider this in relation to care using Heideggerian phenomenology.

The Academic Tutorial

When asked about learning experiences as a tutee, the chances are that responses will vary from excellent to not so good, but rarely indifferent. Specific tutors may easily spring to mind, while others fade into the shadows of the past. The reasons and reactions about what worked and what did not work in the tutorial relationship will be contextually orientated and individual. Thus, the tutorial relationship has a powerful effect on the here and now learning experience as well as influencing future thinking and action: in short, the in-course experience is likely to have post-course impact. Indeed, the style and approach adopted by tutors may reflect elements of their own experience which they may or may not be aware of. The jumble of personal experience, professional knowledge and organizational requirements renders pinpointing what makes a good tutorial relationship tricky. No two learners (or tutors) are the same, no two learning contexts will ever be totally repeatable, so identifying the principles of what makes a tutorial relationship successful, rather than prescriptive method, is beneficial. Yet, despite the importance of the tutorial relationship, there is limited empirical consideration of the more subtle, intrinsic implications of the tutorial process (Yale, 2017). Indeed, as Walker (2018) points out, it is hard to find a unified definition of what tutoring is. This gap in evidence and lack of consensus is intriguing given UKs emphasis placed on tutorial support in relation to issues of competition, league tables, retention, widening participation and the consumerisation of education as wrapped within the UK Teaching Excellence Framework (Stenton, 2017; Thomas et al., 2017; O'Leary et al., 2019).

It may be that organizations respond to political and policy drivers by reviewing tutoring policies, guidance, governance and training, where the tutorial can be framed as an auditable activity, to show that tutoring is “done” and is reportable to a host of academic committees and overall, can be made publicly visible (Blackmore et al., 2016). However, focus on the externally visible and measurable activities misses the crucial point of tutoring: that learning is a highly personalized endeavor, often implicit, often recognized retrospectively, and largely, without quantification. This observation is important as the role of higher education has a dual remit; firstly, attainment in the here-and-now, and secondly to enable learners to manage and succeed in unknown futures. Therefore, we cannot fix our attention on the short-term targets without considering what happens after our students leave the university. Knowledge and people move on and develop, therefore tutorial concern is more than “getting students through” an educational system. Rather, we are empowering learners to become their own “knowledge producers” (Iversen et al., 2015, p. 1) in the present and longer term, adopting an on-going attitude for acquiring and evolving the skills to question, search, select, and analyse. In other words, the preparative function of the tutorial has important pedagogic implications for current understandings, and possible future understandings. The tutorial relationship inherently encompasses the past, present and future, and where the individual is in relation to the often slippery states between the known and the unknown (Land and Meyer, 2010). The question of what makes “good” tutorial therefore is unanswered.

The uncertainty triggered by the process of learning is unique for each individual and carries with it two interlinked factors; firstly that recollections of the embodied experiences may appear as long forgotten, and secondly, how we were made to feel during those tutorial interactions can transport us back to those precise moments via the affective residues of that experience. What we experience could fall on a spectrum of responses, ranging from positive, negative or indifferent, but significantly, our memories are bundled in with how we feel about a situation. However, when we as academics book in, or plan tutorials, it is easy to overlook the affective consequences of our tutorial intentions. This is not deliberate. When we add the student name(s) to our diary and do the tutorials, we are often thinking about the purpose of the tutorial from our own academic perspective, which may be the assignment work and the specific disciplinary content. We may forget what it is really like to be a tutee, resulting in a mismatch between our intention and the learner experience. Such division may be compounded because the tutorial as a concept and as a process is multifarious, resulting in tutoring guides which tend to steer us toward the practical tasks of the tutorial role. Yet, to get to grips with what contributes to “good” tutoring, the powerful psychoeducational consequences cannot be ignored (Goldspink, 2017), and as Fung (2017) stresses, we need to ask what we, as part of a university are ultimately aiming to achieve. This type of intrinsic consideration is necessary as the tutorial experience is not explicated by observable behaviors alone, because actions are “infused with intentions” (Pring, 2015, p. 117). Moving beyond the idiom of “tutorial as doing” enables new conversations about what underpins constructive tutor/learner interactions and as Giles (2011) points out, relationships in the educational experience are hard to avoid, however we view them. The pedagogic meanings held within tutorial relationships are idiosyncratic, they belong to the individual and will resonate in different ways. As a result, heightening the sensitivity of the tutor and tutee relationship matters because of the far-reaching consequences of the academic exchange. This is why we argue that the tutorial needs to be re-framed as a form of academic care, and our proposition is not purely theoretical, it has practical implications too.

Pedagogic Definitions of Care

Care is a complex phenomenon. At a rudimentary level, the origins of the word refer to internal “trouble” or “grief” (Simpson and Weiner, 1989, p. 893–894) associated with mental suffering. However, in the literature, the theory of care connects the self, other people and things, in terms of practice, values, and personal disposition. An overarching explanation of care is offered by Fisher and Tronto (1990, p.40) as:

“a species of activity that includes everything we do to maintain, contain, and repair our ‘world' so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, ourselves, and our environment, all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web” (1990, p. 40).

However, Tronto (1994) later refined this view via four sub-elements that reflect phases, good intentions, or aims: (a) attentiveness; (b) responsibility; (c) competence and (d) responsiveness. Similarly, in an educational context, Noddings (2002, p.11) expresses the notion of ethical caring or a care for as; “a state of being in relation, characterized by receptivity, relatedness and engrossment” (2002, p. 11) and suggests that care is the backdrop for pedagogical activity.

In this paper, we accept that care is implicit within most pedagogical activity—most academics teach because they care about their subject, its disciplinary foundations and its potential applications. Mostly they want their students to understand their discipline, and to gain from this understanding, and hopefully to enjoy it. Our view is consistent with Nixon (2008) ideas about the moral cornerstones of academic work which include practice as relational, purposeful, and presupposes social connectivity. In this respect, academic care signifies that people and things matter to us on a range of cognitive and emotional levels. Yet, academic care conveys a number of dialectic struggles because care that enables independence can equally foster dependence. As such, academic care is often obscured within the curriculum, and we argue for a shift in the focus of academic care from that of tutor-led pedagogical intention to that of the lived interactions within the personal tutorial context. To conceptually revisit the tutorial as academic care, we ground the concept within phenomenology. However, before we can revisit the tutorial as academic care, we need to briefly point to why phenomenology is useful.

Heideggerian Lexicon of Care

The central concern for the hermeneutic phenomenologist Heidegger (1927) involves the philosophical conundrum of the meaning of being. In Heideggerian terms, care is how we define the human self (Inwood, 2000) and is essential for our engagement with the world.

To explain his ideas, he used the term Dasein, which means “being-there” to refer to our experience of participation and involvement in the world. Conceptually, Heidegger (1927) took inspiration from a Danish philosopher, Kierkegaard, and his beliefs about concern and care, but where Kierkegaard recognized care or concern as psychologically subjective, Heidegger took an ontological view that care is the primordial structural entity, preceding and featuring in every aspect of our lived experience. As such, care reflects the self in terms of unity, authenticity, and entirety, or Dasein. However, Heidegger (1927) points out that the human self is inclined to become removed from its own authentic being by retreating into the crowd. Living in the wake of how other people think and act means that we allow ourselves to be led by, and unquestioningly follow taken-for-granted social expectations. Here, care (Sorge) is important because it beckons the self (Dasein) away from the other, and in its place, empowers authenticity. Hence, for Heidegger (1927), care is inherently linked to openness and a willingness to engage with future possibilities. In this respect, recognizing the self (Dasein) as care indicates that we understand ourselves-in-the-world by what we can and cannot do. Dasein decides itself, hence the meaning of its existence unfolds through all of our experience. Thus, the experience of higher education is not restricted to a particular time, place or person, instead it is interwoven within our being-in-the-world.

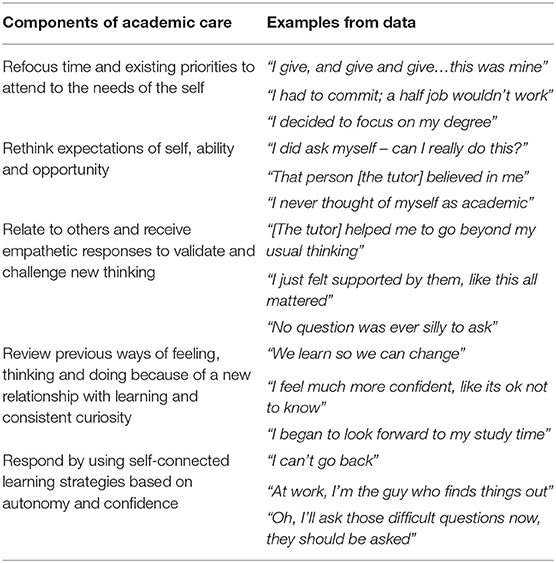

The findings in Goldspink (2017) research evidences the tutees transition from their acceptance of taken-for-granted assumptions to the consideration and construction of new, authentic insights about their previously held beliefs, which led to new was of being and interacting with others. Acknowledgment and questioning of prior understandings enable alternative perspectives to grow and flourish in the context of the individual, which engenders meaning and purpose. Involvement and ownership in the tutorial process gradually adjusted from content-based knowledge to self-based knowledge through five components of engagement: refocus, rethink, relate, review, and respond. These are presented in Table 1 alongside verbatim examples from Goldspink's data. However, how the learner perceives the tutorial relationship will influence their investment in the tutorial relationship or as one participant said, “the tutor is key.” The tutor can metaphorically unlock learning, but they can also inadvertently shut-down learning opportunities through their unchecked expectations and actions.

What is evident in the table is that there is a distinct shift between component 1 and 2, and 4 and 5. Here there is a shift from the outside world and “they” (the tutors) to the internal world of the “I,” specifically; I own my learning and what I want to do with that learning. As the participants began to confidently and routinely question themselves and others (Baxter Magolda and King, 2012), their response to their learning enhanced their autonomy, which continued post-course. The nurturing learning environment fortified individualized transformational processes, without the expectation of transformation to occur in any set frame.

However, when two of the participants struggled to connect with their tutors, they experienced feelings of frustration, confusion, and abandonment. Without feeling cared for, mutual respect diminished and learning facilitators become learning inhibitors: “I don't think she [the tutor] got just how difficult it is when you're a distance learner and you don't get what you are supposed to be doing,” and “I was bottom of the list… he [the tutor] didn't fill me with much enthusiasm.” The situation returned the participants to previous ways of being and “wanting answers” rather than finding solutions for themselves. As such, we can identify factors that are both enhancing of, and limiting to, learner confidence and authenticity in their learning. The academic tutorial thus is a relationship of care, where good care can develop authentic learning, and where a poor care relationship, can stifle authentic and independent learning. To explore this further, we turn again to Heidegger.

Discussion: Academic care and tutorial relationships

In the context of higher education, Heideggarian philosophy emphasizes the experiential complexities and fluidities of the academic development/personal development nexus. To polarize academic development from personal development fails to recognize higher education as an integrated experience of thoughts, feelings and behaviors. In the Heideggerian tradition, the semantics of care derive from the Latin cura, meaning to be aware of, and compassionately attentive to, the self, people and things (Escudero, 2013). The translation includes being concerned and troubled as key components for growth. However, according to Heidegger (1927), our approaches to care are not static and change depending on the situation that we find ourselves in.

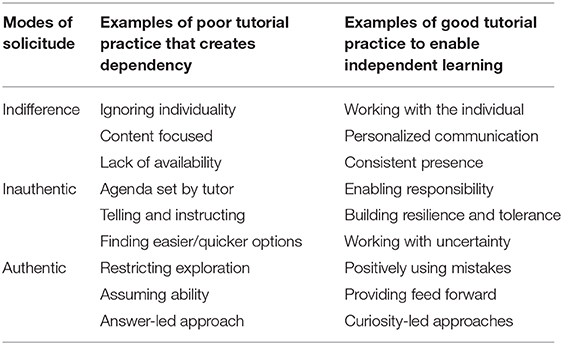

As such, Heidegger conceptualized care as solicitude, or an attitude to other human beings. He defined the three modes of solicitude: firstly, a mode of indifference, where the “being-there” of others is unnoticed or neglected; secondly, there is “inauthentic solicitude” which is the type of involvement that “leaps in” for the other and is characterized as a form of control, even though it may be well-meaning. In this instance, there is the likelihood of increasing unconstructive dependency because others surrender their struggle and even if they appear to be receiving help, their autonomy is taken from them. In this mode of caring, the other person's existential project in negated. In other words, by giving, we are actually taking their experiential prospects away from them. Alternatively, authentic solicitude assists others in taking responsibility and care for themselves. Heidegger (1927, p. 123) describes this as a “leaping ahead” of the other to liberate them to face their own “Being” and manage the burden of their own existence. Instead of taking over another's task, they are encouraged to do it in their own way and deal with the outcome for themselves. In doing so, the unique existential project of the other is preserved and respected.

Applying this to education, (see Table 2) effective academic care is conveyed through interactions that will inspire learners to autonomously connect to their own learning. Hence, the experience of academic care reveals human connections help people to grow by embracing their own curiosity (Riley, 2013).

A feature of academic care within the tutorial is to challenge taken-for-granted thinking. Academic care therefore is not a set strategy, but rather is an ethos that re-positions the learner as the architect of their lived experience. We see this as a joint commitment between the tutor and the learner, and it is the skill of the tutor to know how and when to support the individual learner so that they can gain the academic confidence to evolve from a reliance on others to a reliance on themselves.

However, gaining of academic confidence takes time. To go beyond our accepted frames of reference exposes us to the unknown and requires a level of courage. Learners must risk bewilderment, making mistakes or owning up to a lack of understanding, all of which are tied to taken-for-granted thinking and can hold us back from our own potential. However, to care is more than to support. It is also a way to advocate and demonstrate what it means to be curious, a way of being-there by actively experiencing the world in order to become oneself in the world. The transition from acceptance of the status quo to curiosity is regarded by Heidegger (1927) as an ontological necessity for human beings (Inwood, 2000). Heidegger (1927) did not believe that a person could be taught to think by another, because thinking is an experience of being-lost-in-thought. As soon as we attempt to instruct how thinking happens, we shift from in-thought toward an ontic method (i.e., describing the phenomena rather than the nature of the phenomena) which is not the same.

This Heideggerian view illustrates how self-induced thinking and inquisitiveness is more effective than a didactic exchange of knowledge for future impact. From this perspective, academic care compels a different type of tutorial conversation and approach. The tutorial relationship is based on learner reflections of their own academic strengths and needs to shape what is experienced and inspire deeper levels of personalized learning, with the aim of longer-term benefit and utility (Goldspink and Engward, 2018). As a result, the internalized learning that may have taken place is likely to be different to the learning that is assumed. Although external knowledge is more recognizable in the present, longer-term understanding becomes more available as curiosity enables “what ifs” to be explored, even if not acted upon. Conversely, passively living without care reduces the possibilities of what our world has to offer, limiting choice and personal potential.

It is within the space of uncertainty that “not knowing” can be redefined as a place for curiosity rather than something to be avoided, where learning is nurtured through opportunities to challenge, question and discover. The problem is knowing what that experience of ambiguity might mean for the learner, because for Heidegger (1927), the self is taken-for-granted and unquestioned. As Mezirow and Associates (2000) notes, people more often question outcomes when they are not expected or wanted. In other words, transformation is not about receiving information or “knowing more”; it is experienced in terms of how a person appraises new information and the impact of that information on themselves. Mälkki and Green (2014, p11) phrase this as putting knowing to “the test” (2014, p. 11), and Maiese (2017) argues that transformation occurs when changes occur in how we think, feel, and behave. Hence, deeper-level learning is recognizable when knowing the answers is superseded by curiosity, and as knowledge approaches the self, so self-connected learning unites the self with the world so that different viewpoints and possibilities come into view (Goldspink, 2017).

Revisiting the tutorial as academic care offers the opportunity to review both our assumptions as tutors and our pedagogic practice. In particular, the ideas surrounding academic care requires a review of both how and why tutors enter into dialogue with learners. Consideration is needed about the language of the tutorial and what the messages are intended to convey. The following questions are prompts to appraise tutorial interactions and to demonstrate that academic care may already be embedded within practice or can be adopted without major upheaval to the existing operational tutoring infrastructure within the university:

• How do I routinely greet students?/What message might this give?

• In what ways to I personalize the learning experience?

• How do I understand the meaning of this learning experience for the student?

• How does this learning connect with the students' previous learning experiences?

• In the students' view, what were the challenges/opportunities of this learning experience?

• Are there ways to find out and understand what the student gained from the learning experience—was it expected?

• What strategies can I use / develop to enable the student to manage and positively respond to uncertainty?

• What can the student take forward from this learning experience/what needs to change?

• How will the student translate their new knowledge/understanding outside of the university setting?

• How do I routinely end tutorial interactions?/What message might this give?

Remaining open to questioning routine tutorial practices ensures that the tutoring role does not become a mechanical, task-based process. Situating learners at the center of their learning experience allows them to view issues from different perspectives and gives access to alternative ways of thinking and acting.

Conclusion

In this paper we suggest that academic care unites academic and personal development by recognizing the personalized, psychoeducational nature of the learning experience. Our discussion establishes the experience of academic care as central to effective tutorial support which has long-lasting and far-reaching positive consequences. Connecting learning and the learner's life experiences is essential, and in particular between interaction and the continuing nature of experiences. In doing so, the learner is the main contributor to their own learning process and the learner's role is transformed and as a result, so is the tutor's. Learner choice, autonomy and accountability cultivates opportunities for meaningful and applicable pedagogy.

The notion of academic care encompasses growth, from both understanding and having an effect on the world around us, whilst also being affected and changed. Therefore, the purpose of academic care in the tutorial relationship is to inspire curiosity, leading to a deeper, and longer lasting, understanding of the self and the world around us. The role of the tutor is therefore directed to the unique needs of the learner, and the tutor's main aim is to work with the individual, assist them to gain confidence to question understandings and remain curious about the application of knowledge. Goldspink (2017) empirical work suggests that the achievement of personalized outcomes stems from a nurturing, self-connected experience, which encourages and empowers a new relationship to learning. The tutorial process is centrally positioned to enable learners to adapt to learning by the self, for the self. Supportive interactions that encourage learners to take responsibility for their own learning will promote new ways of learning. Tutor attitudes and actions can facilitate inquisitiveness so that learners rediscover and remain curious in order for them to positively manage and use the experience of uncertainty to find their own innovative and creative solutions. Overall, the tutorial is a learning space which needs to acknowledge and respond to the physical, affective and cognitive reactions of learning. Establishing trusting tutorial relationships offers learners the opportunity to find and trust their inner voice which is essential when viewing personal development as a continuing, lived experience.

The focus of the findings presented here thus relate to the academic tutorial; however, we accept the difficulties of attempting to narrow educational interactions into neatly defined roles. Instead, we are suggesting a way to manage the complexity of educational interactions by revisiting the ethos of what we are aiming to achieve when we work with students. As such, the notion of academic care spans the definitional ambiguities of tutoring and offers potential insights that can inform routine practice. The intention is to actively think about how we work with students in order to maximize their learning experience without major disruption to current educational processes. In other words, it is not about finding more time to work with our students, rather it is about considering how we use the time that we have with them.

Ethics Statement

The study referred to in this paper was carried out in full accordance with the recommendations of the Faculty of Health, Social Care and Education, Research Ethics Committee, Anglia Ruskin University.

Author Contributions

The authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Baxter Magolda, M. B., and King, P. M. (2012). Assessing Meaning Making and Self-Authorship: Theory, Research and Application. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Blackmore, P., Blackwell, R., and Edmondsen, M. (2016). Tackling Wicked Issues: Prestige and Employment Outcomes in the Teaching Excellence Framework. HEPI Occasional Paper 14. Available online at: http://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Hepi_TTWI-Web.pdf

Escudero, J. A. (2013). Heidegger: being and time and the care for the self. Open J. Philos. 3, 302–307. doi: 10.4236/ojpp.2013.32047

Fisher, B., and Tronto, J. (1990). “Toward a feminist theory of care,” in Circles of Care: Work and Identity in Women's Lives, eds E. Abel and M. Nelson (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press) 36–54.

Giles, D. L. (2011). Relationships always matter: findings from a phenomenological research inquiry. Austr. J. Teacher Educ. 36, 80–91. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2011v36n6.1

Goldspink, S. (2017). A phenomenological exploration of adult, asynchronous distance learning (Doctoral thesis). Chelmsford: Anglia Ruskin University.

Goldspink, S., and Engward, H. (2018). Shedding light on transformational online learning using five practice based tenets: illuminating the significance of the self. Asia Pacific J. Contemp. Educ. Commun. Technol. 5, 10–16. doi: 10.25275/apjcectv4i2edu2

Heidegger, M. (1927). [2010]. Being and Time (J. Stambaugh Translation). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Iversen, A.-M., Pedersen, A. S., Krogh, L., and Jensen, A. A. (2015). Learning, Leading, and Letting Go of Control: Learner-Led Approaches in Education. SAGE Open. doi: 10.1177/2158244015608423

Land, R., and Meyer, J. (2010). “Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge: dynamics of assessment,” in Threshold Concepts and Transformational Learning, eds R. Meyer, R. L. and R. and C. Baillie (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers), 61–80.

Maiese, M. (2017). Transformative learning, enactivism, and affectivity. Stud. Philos. Educ. 36, 197–216. doi: 10.1007/s11217-015-9506-z

Mälkki, K., and Green, L. (2014). Navigational aids: the phenomenology of transformational learning. J. Trans. Educ. 12, 5–24. doi: 10.1177/1541344614541171

McNamara, M. (2005). Knowing and doing phenomenology: the implications of the critique of “nursing phenomenology” for a phenomenological inquiry: a discussion paper. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 42, 695–704. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.02.002

Mezirow, J., and Associates (2000). Learning as Transformation. Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Nixon, J. (2008). Towards the Virtuous University. The Moral Bases of Academic Practice. New York, NY: Abingdon: Routledge.

Noddings, N. (2002). Noddings N. Starting at Home: Caring and Social Policy. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

O'Leary, M., Cui, V., and French, A. (2019). Understanding, Recognising and Rewarding Teaching Quality in Higher Education: An Exploration of the Impact and Implications of the Teaching Excellence Framework. UCU Project Report. Available online at: https://www.ucu.org.uk/media/10092/Impact-of-TEF-report-Feb-2019/pdf/ImpactofTEFreportFEb2019

Riley, D. C. (2013). Heidegger teaching: an analysis and interpretation of pedagogy. Educ. Philos. Theory 43, 797–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-5812.2009.00549.x

Simpson, E. S. C., and Weiner, J. A. (Eds.) (1989). The Oxford Encyclopaedic English Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Smith, J. A. (2004). Reflecting on the development of interpretative phenomenological analysis and its contribution to qualitative research. Psychol. Qual. Res. Psychol. 1, 39–54. doi: 10.1191/1478088704qp004oa

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., and Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London: Sage.

Stenton, A. (2017). Why Personal Tutoring is Essential for Student Success. HEA. Available online at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/blog/why-personal-tutoring-essentialstudent-success

Thomas, L., Hill, M. O.', Mahony, J., and Yorke, M. (2017). Supporting Student Success: Strategies for Institutional Change What Works? Student Retention and Success Programme. Higher Education Academy. Available online at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/hub/download/what_works_2_-_full_report.pdf (accessed April 05, 2019).

Tronto, J. (1994). Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. New York, NY: Routledge.

Walker, B. (2018). A defining moment in personal tutoring: reflections on personal tutoring definitions and their implications. IMPact 1:8. doi: 10.25507/1120188

Keywords: academic care, curiosity, hermeneutic phenomenology, higher education, transformation, tutorial relationship, self-connected learning

Citation: Engward H and Goldspink S (2020) Working With Me: Revisiting the Tutorial as Academic Care. Front. Educ. 5:105. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00105

Received: 20 February 2020; Accepted: 04 June 2020;

Published: 09 July 2020.

Edited by:

Liz Thomas, Edge Hill University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Helen Louise Holder, Keele University, United KingdomMichelle Morgan, Consultant, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2020 Engward and Goldspink. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hilary Engward, aGlsYXJ5LmVuZ3dhcmRAYW5nbGlhLmFjLnVr

Hilary Engward1*

Hilary Engward1* Sally Goldspink

Sally Goldspink