- Faculty of Education, University of the Americas, Santiago, Chile

The following article is about the conceptions that different novel teachers of history and social sciences have concerning the inclusion of women and their history during their teaching practices. The objectives followed were to interpret and understand the content of the discourse of the interviewees, in order to analyse the advantages and limitations that the participants recount about their initial teaching practices. The methodology used is qualitative, forming a focus group and interviewing the teachers. Amongst the main results, it stands out that the formation given has not included women and their history, confined in traditional perspectives with predominance of powerful men. The interviewees add that in their teaching practice they have not worked with women's narrative, however; they recognize how relevant it is to include and transform teaching practices based on the recognition of gender issues in today's world. From a history and social sciences teaching point of view, learning, and working with the relevance of actions and narratives of women would generate agency. Thus, students could feel empower themselves by identifying themselves with these new models; this with the objective of generating social change concerning gender equality.

Introduction

Critical theory and their approaches were considered for the analysis and reflection over the content of the speech of the participants (Giroux, 1998; Apple and Beane, 2012; Apple, 2014; McLaren and Kincheloe, 2015). Critical theory provides tools to reflect on teaching and learning processes with the purpose of generating developments concerning the fight against inequality because of gender, ethnic groups and social status. As Giroux (1998) and McLaren and Kincheloe (2015) stated, one of the objectives of critical perspectives is to position social justice as an axis of educational projects. It must be acknowledged that the struggle is against a school that has silenced, traditionally and historically, the different critical expressions of their students (Giroux, 1998; Apple, 2014). The authors state that their stories, knowledge and possibilities of generating changes are scarcely worked on Giroux (1998), unlike the broad work done in the interests of powerful structures.

We coincide with the idea that the school is, within the analysis of critical theory, a space of hegemonic struggle over the domain and transmission of specific and dominant ideologies (Apple, 1998, 2014). These ideologies usually belong to those who have or have had power. The educational guidelines can vary according to the current government, however; what rarely varies is the hegemonic and ideological struggle. The school deals with the distribution of standards and convenient dispositions that each of us will assume in a hierarchic society (Apple, 1998, p. 33).

Bonilla and Martínez (1992), Apple and Beane (2012), and Azorín (2015) agree with what has been posited adding that the school and their teaching systems fragments knowledge aligning it with the “official” instructions of content and standardized tests. In general, this content does not recognize the presence and actions of characters that are outside the dominant culture, such as women, ethnic groups, immigrants, childhood, amongst other absentees. The rare times these characters are depicted, they are relegated to their condition of secondary characters in spite of their own individualities, always subordinated to the actions of the powerful male protagonist (Marolla, 2019a,b).

Regarding the context where this study is developed, it is important to consider that there are both public and private universities in the Chilean educational system. In both systems a tuition fee must be paid and the amount will depend on the type of institution. As to the school system (ages six to eighteen) there are three types of schools: state, private, and mixed. The employment system for novel teachers does not show greater complexity. This is because, there are neither applications nor public tenders to fill in the positions. Therefore, each year the school's administration selects curricula to integrate the novel teachers into the teaching staff. This selection is made under different selection criteria, such as external recommendations, qualifications, and/or school necessities. The selection criteria are of exclusive decision of each school's administration department. Thus the lack of problems novel teachers face to be integrated into the school system, furthermore; this enables yearly mobility and integration of novel and experimented teachers in educational establishments (Marolla, 2019b).

It is relevant to state that the study programmes and the official curriculum supplied by the Chilean Education Ministry, which belongs to the State, and specifically, the history, and social science programmes are built based on traditional perspectives on history with male, white, and western protagonists. As a consequence, the formation of the teaching staff in general is framed as to provide future history and social sciences teachers the necessary tools and strategies to continue teaching based on the traditional perspectives: the protagonism of men that have had political, social and economic power (Apple, 1998).

Theoretical Framework

When teaching history and social sciences is done from ideologies that arise from pre-established power hierarchies it causes the preservation of status quo, which has been in charge of the production and reproduction of the aforementioned power hierarchies and, this way, of the continuance of social inequality (Azorín, 2015; Balteiro and Roig-Marín, 2015; McLaren and Kincheloe, 2015). History is presented as a tale or narrative built from the protagonists that have had some sort of political, economic, and/or military power in society (Barton, 2002), perpetuating the absence of women, who are understood as passive historic characters without any relevance to the social progress.

It can be acknowledged that in the last decades legislation, as well as the studies and movements concerning women, gender and feminism have incremented (Hutchinson, 1992, 2001; Badinter, 1993; Bengoa, 1996; Lerda and Todaro, 1997; Scott, 2008; Friedan, 2009; Díez Bedmar, 2015; Díaz de Greñu and Anguita, 2017). Regardless, this does not mean that there is social justice for marginalized, poor, dissident, anti-capitalistic and migrant women that continue suffering violence, rape, abuse and marginalization, amongst other atrocities.

It is priority that the fight for empowerment and gender social justice spreads to every area of social and cultural life. From the didactics of social sciences point of view, we face the challenge of the formation of new generations; antisexist, and anticapitalistic formation recognizing the fights that have occurred throughout the history of the movement for gender social justice (Hooks, 2000). However, currently women and childhood are not protagonists of the history that is taught and learnt (Marolla, 2019a,b). On the contrary, their voices and narratives are absent while their tales and actions continue to be subordinated by the history of powerful men. Thus, women continue to be mere spectators of the history that is being taught (Spivak, 2012).

Díez Bedmar (2015), Tomé and Rambla (2001), and Díaz de Greñu and Anguita (2017) agree that women, their voices and history are absent in the educational processes as well as in books, programmes and teaching practices (Pinochet, 2015; Marolla, 2019a,b). In fact, Appleby et al. (1994) agree that history and its teaching has been built and transmitted from the hegemonic national values, hierarchic masculinity, and the exclusion of a diverse and pluralist society. To female authors the history that is taught stands out for being racist, sexist, and homophobic (Díez Bedmar, 2015).

Alonso Gutiérrez (1998), Vavrus (2009), Stanley (2010), and Crocco (2018) agree that the teaching staff is an agent in the transmission of gender stereotypes. If the formation continues under the traditional structures of history teaching, issues such as discrimination and inequality will continue to be produced and reproduced in classrooms as well as in society (Ortega-Sánchez and Pagès, 2018; Marolla, 2019a).

Moreno and Sastre (2003), Díez Bedmar (2015), and Crocco (2018) claim that teaching staffs, due to their formation and the androcentric social structures, tend to teach from the patriarchal hegemonic model. Thus a radical change of approaches must exist concerning formation and practices. It is not enough to include women but it is necessary to rethink the models that are included (Espigado, 2004; Fernández and Johnson, 2015; Marolla, 2019a,b). Teaching must encourage reflection and analysis of the provided spaces and tales on women and their history. Accordingly, stereotypes, biases, as well as traditional and normalized marginalization begin to breakdown.

When women are included it is from anecdotal positions or highlighting only those women who, somehow, have had a connection with powerful men. Most women, who have identified themselves with the plight of their people and the dissidences, do not have the place to express their voices, actions, and problems. Women, poor people, children, girls, elderly men, and women, and those who belong to non-white ethnic groups are the human groups that have suffered and continue to be oppressed and dominated (Pagès and Sant, 2012; Ortega-Sánchez and Pagès, 2018; Marolla, 2019a,b); like so, the school acts as a collaborator producing and reproducing guidelines as well as cultural and gender stereotypes. Bullock and Stallybrass (1977) state that sexism is manifested as a system rooted in beliefs, attitudes and institutions, often unconsciously, in which the distinctions between intrinsic value of people are based on their gender and sexual roles (Bullock and Stallybrass, 1977; Gillborn, 1990, p. 165).

Subirats and Brullet (1988), Aubert et al. (2010), Díez Bedmar (2015), and Díaz de Greñu and Anguita (2017) claim that, because of what has been stated before, there are barely any women in historical narratives. Practically, there are not any female philosophers, scientists, workers, and leaders except those who have become prominent because of their collaboration in masculine protagonism. Feminine subordination has been naturalized in society (Marolla, 2019a).

Harris (1996), Bickmore (1999, 2002, 2008), Vega (2002), and Aguilar Ródenas (2015) agree that the school is an excellent place to promote and generate changes. The process of teaching and learning could arise from the students' critic and reflection regarding social inequalities and injustices from a gender perspective.

Crocco (2008, 2018) states, agreeing with what has been discussed, that the inclusion of women in teaching and learning history not only requires that it is done in the curriculum, programmes, and books, but it is required that the practices and discourses that are transmitted are critical and reflexive, inclusive and diverse. There must be a teaching practice and a discourse that not only includes women and their voices, but it must also promote the critic of their structures and spaces where gender inequality remains and reproduces (García Luque, 2013; Rodríguez Martínez, 2014).

Álvarez de Zayas and Palomo Alemán (2002) and Azorín (2015) agree that inclusion of diversity favors new understanding of the processes, and specially, of the social reality the students are part of. It is a way, according to the authors, that the students can identify with historical references. Grever (1991), Volman et al. (1993), Díez Bedmar (2015), Fernández Valencia (2015), and Díaz de Greñu and Anguita (2017) and add that from identification they could start to consider spaces and paths to social activity and politics against inequality and gender violence.

Therefore, Casas (1999), Subirats (2001), and Azorín (2015) posit that, first of all, school spaces must be democratized with the purpose of breaking the gender barriers that can be found in the classrooms and in teaching. Concerning this, Thornton (2010) states that women, as well as other actors and actresses who are prominent in society but have been made invisible in history teaching, are essential to make transformations. Hence the author asks this: “Does everybody count as human?” (Thornton, 2010, p. 88).

Woyshner (2002) claims that research concerning the teaching staff must not only be about women's experiences and voices, but about inclusion of topics that have been traditionally silenced as bodies, sex, race, private life, feminine mind-set, domestic work, among others. There are many female authors that have worked on this and have presented the urgent necessity that the teaching staff becomes a critic of traditional and masculine history with the purpose to provide students with places that could generate participation and empowerment against gender inequality (Hahn, 1996; Asher and Crocco, 2001; Hess, 2002; Crocco and Libresco, 2007; Bickmore, 2008; Crocco, 2010, 2018; Donoso-Vázquez and Velasco-Martínez, 2013; Aguilar Ródenas, 2015; Balteiro and Roig-Marín, 2015; Díez Bedmar, 2015; Fernández and Johnson, 2015; Díaz de Greñu and Anguita, 2017; Ortega-Sánchez and Pagès, 2018).

Methods

Design

The study is of qualitative type (Álvarez-Gayou, 2003) following the strategy of collective case study (Simons, 2011). In addition, critical methodology was used for the analysis conceptions (Álvarez-Gayou, 2003; Cohen et al., 2007). Arnal et al. (1994) posit that such strategy delivers the chance to make decisions, generate assumptions and reflect to the emancipation of people.

The advantages of case studies, following Arnal et al. (1994), Cohen et al. (2007), Stake (2007), and Simons (2011) are: (a) to discover facts or processes that other methodologies would overlook; (b) to deliver chances to uncover deep and unknown meanings; (c) to collaborate in the comprehension of complex and educative realities; (d) to involve the participants and the researcher in the comprehension of educational practices; (e) to include an specific population and does not pretend to generalize the findings of the research.

The design of the study is designed through the ideas of Habermas (1988) and Wolcott (1994), as described by Smyth (1989). Wolcott (1994) presents three stages: description, analysis and interpretation. The description stage is focused on what is happens; the analysis stage determines how structures and relationships work. While, the interpretation phase is concerned with the results obtained with the purpose of understanding the processes. Smyth (1989) based on the critical thoughts of Habermas (1988) proposes a sequence of four stages: description (what is happening?), information (what does it mean?), confrontation (why does it happen?), and reconstruction (how could it be different?), this model was used by Marolla (2019a,b).

It is noteworthy that what has been included in this study about novel teachers as well as the objectives and proposed methodology are part of a much wider research that includes different types of teachers such as historians and teachers of teachers; data which is still in the analysis stage. Nevertheless, due to the relevance of the data gathered from the novel teachers; it was decided to give the same relevancy to these in relation to the results of this study.

Objectives

The objectives of the investigation were:

• To describe and analyse the content of the novel teachers' discourse concerning the inclusion of women in initial teaching practices in history and social sciences teaching.

• To explore the opportunities and the limitations that the participants have pointed out concerning the inclusion of women and their narratives in their initial teaching practice.

• To explore the opportunities and the alternatives limitations that the novel teachers have put forward pointed out in order to include women and their history in their teaching practice.

• To offer and describe ideas and perspectives concerning the spaces that the participants have proposed have pointed out, with the aim to include and present as an issue problematize the assigned role to women and their history in the teaching practices.

Participants

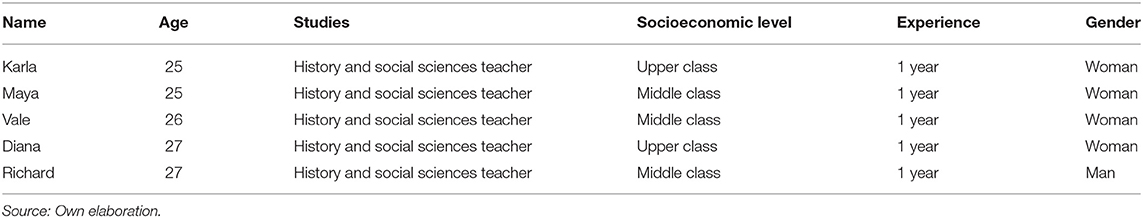

The participants were five female and male teachers of history and geography who had been teaching for a year in public schools in Santiago, Chile. All of them were awarded their degree and title in a public university that forms teachers. Every name included is fictitious, in order to give identity to every participant while safeguarding their anonymity and integrity at all times. The participant's age ranges between 25–27 years old, which makes them young teachers early in their career. In Table 1, essential characteristics of the participants are detailed:

The criteria used for selection was framed according to the definitions of Rodríguez Gómez et al. (1999) and Simons (2011): (a) the accessibility and easiness to remain at work in the field; (b) the existence of diverse processes and interactions; (c) the chance to establish a good rapport with the informants; (d) the geographic location and; (e) the disposition of the institutions and people that participated. It is worth stressing that the selection of participants was not done with representation in mind, but with the purpose of meeting the objectives set for the study.

We assume that the initial study presented is a big advancement for the didactic area of social sciences and the inclusion of female protagonists in the teaching and learning processes. Specially, for the issues of discrimination, stereotypes, and bias that firmly prevail in our classrooms, as well as the constant productions and reproductions of the classic gender roles and patterns. What has been stated here could serve as an initial study since by no means this study has aimed for generalization. The results, this way, leave the open option that this research topic, methodology, and objectives are replicated based on a bigger sample, with the objective to corroborate the methodological approaches, as well as to provide new ideas and perspectives concerning the research questions (?).

The Interviews and Focus Groups

The interviews were semi-structured, following the criteria of Álvarez-Gayou (2003), Bisquerra (2004), Stake (2007), and Creswell (2014). The focus group was conducted after the interview was finished. This decision was advantageous because it facilitated the clarification of topics that arose in the interview, at the same time it allowed to contrast different expressions expressed by the teachers (Álvarez-Gayou, 2003; Bisquerra, 2004; Cohen et al., 2007). The design of the interviews and the focus group was constructed according to Álvarez-Gayou (2003) and Cohen et al. (2007) following: (a) number of participants; (b) selection, duration, guideline, and technical support, and; (c) informants that are willing to share their experiences.

In the interviews the method used was informal conversation interviews with the aim to generate trusting environment and relationship which allowed the informants to share their experiences and opinions with freedom. Cohen et al. (2007) add that this method is ideal to gather information about controversial topics since a non-hierarchic space is created so the participants can express their ideas freely. The inquiry, the data reduction analysis, the categorical measurement and the categorization for the research designs phases followed (Bisquerra, 2004; Cohen et al., 2007; Simons, 2011). These phases contributed with the construction and the execution of the interviews.

The reduction phase contributes with the information selection which is key concerning the answers gathered in the interviews (Bisquerra, 2004; Cohen et al., 2007). The categorical measurement contributes in establishing concepts and classifications based on key information that answers to the objectives, and the categorization phase helps to establish useful patterns to put the information in order, based on the objectives of the study (Bisquerra, 2004; Cohen et al., 2007; Simons, 2011).

The construction of the focus groups was done according to Álvarez-Gayou (2003) and Cohen et al. (2007) criteria where they suggest that their design is undertaken after the interviews with the aim of generating questions and topics based on what was firstly said by the interviewees. The strategy of “the probes” was used (Cohen et al., 2007), which consists of generating extensions to the themes and answers gathered in the interviews. In addition, with “the probes,” extensions and clarifications are generated concerning what has been said in the interview process as well as in the focus group itself. This way information could be compared, topics explored in depth, debate between the participants generated, and consensus amongst the questions established.

Data Analysis

The process that was followed for the qualitative analysis was based on the stages that arose by the claims of Miles and Huberman (1994), Wolcott (1994), Stake (2007), and Creswell (2014). The followed stages were: (a) descriptive stage; (b) analytic stage; (c) case interpretation stage (where data is put in order, patterns are organized, concepts, and schemes to reflect about the problem); (d) triangulation; (e) critical stage (where analysis and reflection about data are done). It is important to highlight that for the speech analysis delivered by the participants, Bardin's (1986) content analysis was used.

With the objective of defining the research results, the following research questions are posed which have served as a guide in the instruments' design and in the analysis of the teacher's discourse that the teacher staff has provided: How would you describe the initial teaching practices you have done? What are the main difficulties that you have faced teaching history and social sciences? Have you included women and their narrative in the teaching processes? How would you describe the topics that are seen in class? With which protagonists do you work in history and social sciences class? Which are the perspectives that you believe would promote the inclusion of women and their narratives in teaching practice? What is required in classrooms and in teaching to include women and their narrative in the teaching practice? How would you assess the first year of teaching practice concerning women and their history as protagonists in your classes? What are the main opportunities and the obstacles that you could describe that influence the teaching practices to include women and their history? All of these questions, are intertwined directly with the proposed objectives in the construction of the instruments and in the definition of the topics that are presented in the results.

Ethical Criteria

The ethical criteria were defined according to the democratic model for research (Simons, 2011). This model states that this type of research proposes the implication of the participants. Confidentiality, negotiation, and accessibility were used with the purpose to make knowledge available in a public way whilst caring that the research does not affect the participants. For this, an informed consent (Stake, 2007; Simons, 2011; Creswell, 2014) was given to the participants where they, understanding the study's objectives, expressed their willingness to participate. Furthermore, the participants were shown the transcripts and results, this with the objective of approving their use, or otherwise correcting/deleting the content.

Confidentiality and anonymity (Cohen et al., 2007; Stake, 2007; Simons, 2011; Creswell, 2014) allowed safeguarding the participants concerning any sensitive, personal, or problematic information. Pseudonyms were used for participants as well as the institutions involved. Therefore, people's integrity is under safekeeping and protection in this study. The ethical protocol was approved by University of the Americas. All participants gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Practicality of History and Social Sciences Teaching and Learning

The participants shared their impressions on the practicality of history and social sciences from a gender perspective. Vale claims that it gives a “sense of reality” (Vale, 2018), beyond the contrast of past and present, history provides tools for people to “think for themselves” (Vale, 2018). Diana agrees with what was said and adds that it collaborates in making students feel “part of a whole” (Diana, 2018), because these competences should be acquired in order to fight against “inequality and their own context” (Diana, 2018). Karla states that, at the same time, “history is supposed to drive oneself to reflect about the causes and consequences of one's own acts” (Karla, 2018).

Regardless, the participants mention some difficulties that prevent them to meet the objectives stated. For example, Karla said the pressure to “comply with the programmes based on the objectives of the State” (Karla, 2018) as well as standardized tests, makes it complicated to pose other objectives. Vale and Karla agree that teaching becomes a “mechanistic [sic] process that is not meaningful for the student” (Vale, 2018) because learning based on data memorization primes in class. This is explained by Maya, adding that “the school is focused in facts and events” (Maya, 2018).

Furthermore, Richard states that the curricular organization itself complicates the integration of new themes and characters “the students have problems seeing themselves in the past and see [history] as something disconnected from the present […] particularly with world history content or content that is not closely related to students” (Richard, 2018). Vale agrees and adds that this is caused by the professional formation they have had, where she stresses they are taught “a very chauvinist history, much about men” (Vale, 2018).

All of the participants agree that in the moment they require assistance from their colleagues from the area of history and social sciences to include women and their history, as to generate innovation, but these could not be carried out because of the heavy workload and pressure that their peers were under to cover the contents included in the curriculum. In addition to this and most importantly they all coincide by expressing similar problems concerning the lack of didactic tools and strategies, as well as little knowledge of historiographic perspectives to include women and their history. Moreover, they detail the dominance of historic knowledge based only in the current official curriculum as, with the prevalence of male protagonists who have political, economic, and military power.

Diana, concerning the professional formation granted, claims “I had no courses about women”; thus, she comments that other female and male teachers formed “do not know anything, do not have any context and never go near feminism […] they continue to replicate history” (Diana, 2018). Vale adds that “the text books are decontextualized or not up to date” (Vale, 2018), thus the history and social science that we teach comes from a traditional and masculine point of view.

Vale states that teaching teachers is fundamental to suggest inclusion of women and their history; however; “in my mayor overall: Are there any women's education courses? No” (Vale, 2018). Diana agrees with what was stated and adds that hers was a formation focused on the history of male protagonism, “I do not recall that even one of the questions, in tests, in the different history classes, focused on women” (Diana, 2018). Maya adds that, in her mayor, to suggest women's inclusion and their history came from a personal initiative, since the mandatory subjects involved powerful men as protagonists. It was about developing inclusion “from a perspective of what was more appealing to me and develop it as a personal interest” (Maya, 2018).

Topics That Are Worked in Class

Diana states that, more than just content, she looks to work from the comprehension of the discourse that is transmitted in history and social sciences teaching. Nevertheless, in the framework of women's inclusion, she expressed that “it lacks meaningfulness” (Diana, 2018). In fact, she adds by commenting that in one of her classes “we were discussing the Second World War and every name, every topic were only related to masculinity. The dates, the characters, everything is masculine” (Diana, 2018). According to the interviewee, the female students posit “What is it with us women that we have not been able to bring up this discourse?” (Diana, 2018).

In her experience, Diana reveals that in class, from masculinity we face “hostile and violent environment” (Diana, 2018), thusly Richard states that in order to “make a change the discourse and the way of how one refers to individuals and women” must change (Richard, 2018). To Richard, the complexity lies in that it is a matter of power “where men have the power, power quotas […] because are seeing as powerful figures and women have not had power” (Richard, 2018). Vale agrees with what was stated and adds that “we as female teachers are ignorant concerning women's history” (Maya, 2018) what supposes obstacles to suggest new content.

Maya and Vale agree with this and add that “somehow one builds a society with language and characters” (Vale, 2018), Maya comments that this is crucial because it is “a duty as a teacher to do so” (Maya, 2018) with the purpose to generate social transformations. Vale considers that women's inclusion is conducted outside the official requirements and moved by personal initiatives “it is almost personal what the teaching staff does […] I believe that there are empowered women, the issue is that the studies that are executed are not focused on this matter” (Vale, 2018). Hereby the approach is, from the teacher's point of view, that sources are found within the teaching staff and these generate new inclusive practices.

In addition to this, the teacher claims that with the limitations that arise in the classroom changes to the structures could be made since in her opinion: “it is not necessary to change the curriculum; it is based on what it is already there; to create a new reality with our tools” (Maya, 2018). Richard agrees and states that for example: with “the content of 19th century history or the ‘Conservative-Liberal Republic' one could do something” (Richard, 2018). Nevertheless, the complexity lies in the lack of information in order to work and include women and their history.

Perspectives Concerning Women's Inclusion and Their History

The participants coincide with each other when stating that the absence of women is not caused by the lack of research concerning their history, but it is a problem of patriarchal social structures that have controlled the educational and teaching processes. Diana states that “it is a problem of society, because to ask to be included is like ‘begging', as if we were not human beings […] even when one speaks with another woman she does not even know if she is conscious that she is an individual. So, the problem is a society that had marginalized women for so long” (Diana, 2018). Vale agrees with these comments and says that “our society is essentially chauvinistic” (Vale, 2018).

The teaching staff claims that, in conversation with students, many female students have been victims of gender discrimination and marginalization. Karla states that in her conversations “many girls were actual victims of gender violence, they were actually victimized by their partners […] it is very difficult to change that mentality, to teach women that that is not normal, [they] repeat violence cycles and just a few women are aware of it. In this society there is a lot of gender violence” (Karla, 2018). Diana adds to her previous comments a critique toward women's inclusion and their history being presented as only anecdotal:

“The historical event of the women's vote', do you think it has any relevance? It does not. However, if one comes and says why this is important, why it is useful in a global context or national context, that you did this […] but not all teachers can do that. Firstly, because they do not believe it is relevant or simply because we do not think about it. It is a problem of society, and we, as female teachers, do not put ourselves in that position because it is easier to continue teaching as we have always taught, without making students reflect together” (Diana, 2018).

Thusly, as well as Diana the rest of the participants agree that when women are included as anecdotal or annexes, the way they are included in official plans, it contributes to perpetuate subordination toward a history built from patriarchy. Furthermore, they consider the difficulties that exist in the same society; one that generally is framed under sexist structures. Vale even states that this situation “gets so far that one cannot make any changes, patriarchy is a very rigid structure” (Vale, 2018).

Considering the stated comments, the teaching staff suggests different spaces to include women and their history. Richard states that what it is fundamental is not inclusion per se, but to generate inclusive educative structures: “I think the important matter is to generate a more inclusive society. One that includes groups, not only women, but groups or collectives that are made invisible, that would generate other points of view” (Richard, 2018). Maya agrees that inclusion must be oriented “toward other genders, [to] talk about homosexuals, [to] talk about transsexuals, [to] talk about minorities, also of language and your behavior” (Maya, 2018).

Diana adds, agreeing with her peers, that the educational structures are based on hegemonic and masculine guidelines of the state concerning the citizens' formation: “the educational structures are neither created by women, nor for women, nor to form an inclusive society. These simply answer to form obedient citizens that exercise their civil rights and maintain the order of Chile” (Diana, 2018). Karla adds that within the patriarchal structures, one of the fundamental aspects to change is related to gender judgement and gender stereotypes where women are presented as subordinated toward powerful men, which can change concerning:

“Whenever the topic of women is discussed, immediately one goes to the subject of feelings- the affectivity- as if women were only feelings and no rationale. Young women need to be shown that they are equally capable of studying, of being rational, that they are not ruled by their hearts, that they can go further. They can discover themselves as women, not inferior, on the contrary; capable of carrying out their history” (Karla, 2018).

As the female and male teachers express: to promote an education that includes women from the questioning of the patriarchal structures point of view could be possible in order to establish spaces for the girls to reflect on the marginalization that they have suffered and thus to propose transformations. Richard, concerning inclusion and transformation of the official educational structures says that it should be done in consonance with the content; focused on changes to the traditional approaches: “I believe that it should not be treated as a separate topic because this generates exclusion, segregation. Traditional approaches must be changed” (Richard, 2018).

Teaching Practices in the First Year of Teaching

Maya suggests that in order to accomplish what they have stated they face the problem of didactic formation. In other words, they agree that they do not have the necessary tools to generate transformations to the educational system, as to propose women's inclusion from critical perspectives:

“I believe that there is also a problem in tools given in history teaching programmes, more than just in the curriculum. In general, the problems happen in the mayor's programmes […] we as individuals, as teaching professionals we have the capacity to link it with what we claim […] because I am a woman, we can see it from a different perspective and what we can achieve as teachers” (Maya, 2018).

Diana adds, in relation to the lack of tools in didactics during the professional formation, that it is crucial to include women as well as to propose transformations. For her, in her first year as a teacher it has been complex to generate proposals of inclusion: “If you have a teaching formation where women's historical sources are not included and they are scarce, to deliver these sources to the classrooms is very complex since there is no formation, didactics knowledge and tools concerning this.”

Thus, Vale adds the labor of the teaching staff to include women and their history should not only be about an education based on content, but mainly on values: “as women, we have everything against us, a chauvinist system, but I feel that a woman and teacher has the role not only to teach contents concerning women […] I believe that we need to draw on values to generate ruptures in the chauvinist system” (Vale, 2018).

Richard and Vale agree with what has been stated until now, where the priority is the formation in didactics in order to have tools that collaborate in suggesting spaces of educational transformation. Both add that it has been complex to suggest new spaces and content in their first year of teaching: “I believe that didactics are fundamental […] it shows you the teaching practices in the classroom […] that teaching and learning is not only repetition, that it is not mechanical, but transformational” (Vale, 2018).

Karla also comments about the difficulties that she has had in her teaching practice where she has made efforts to include women and their history. However, students themselves have manifested difficulties to understand the break of the traditional contents that they see in class:

“In my case, colonial history was the most challenging […] I tried to give explanation about a Mapuche woman's witch craft trial, which was a text that a female historian had written […] to see the Mapuche woman, the ‘machi’, mostly as a witch being judged and everything that that woman went through is hard because they [the students] did not understand some concepts […]” (Karla, 2018).

Maya comments about her teaching practices, and that she has included women looking to give meaning to her work:

“My logic is to give sense to these facts and events, and to work or link the student to the facts through practical matters that they see in their daily lives […] given that history is not so distant, it is part of them […]. For me, that is the aim of studying history; not only to understand what happened or why it happened, but to understand how what happened influences us, what does it get to […]. It is possible to give a different meaning to history in people's everyday life and that is much more than just dates and years. It is to give meaning to our present from past events […] (Maya, 2018).

In Richard's experience he expresses that because of the school's curricular organization where he has worked, he had to exclude the approach to women and their history due to the fact that it did not make sense with the content seen in class, further; because of the pressure of his educational center:

“What I did in my teaching, 20th century Chilean history, according to the school's textbook plan, we had to work on the subject of women. It was separated, as a unit: “Women and the vote” […] I discarded it because of matters of time versus content. So, I planned my classes within the framework of two lines: “economy and politics” and a bit of “social” […] then the unit or the section of women was in the middle of the content without any sense, women related content did not fit with the rest of the content. It did not make much sense, there was no correlation in the plan, I might have mentioned it but it was not a class about it” (Richard, 2018).

Diana, at the same time, explains that she has also experienced the pressure of the educational centers and the disconnection of women's approach and their history in function to the rest of the content: “what happens is that one focuses in politics and economy. One sees gender in the classroom if there is enough time when it should be mandatory” (Diana, 2018). Richard adds that in the educational centers and their practices, the problem lies in that women and their history is seen as an annex to the official history led by men: “at least in what I saw […], there is an attempt to include women. In Chilean History, at least women are included but in a separate section when women suddenly make an appearance politically and participate, but then women disappear and have no major continuity” (Richard, 2018).

Lastly, Diana states that the content related to women and their narrative; their actions have been denied and made invisible from the patriarchal construction of history. In her opinion, the solution must be to transform the structures and the history teaching practices with the purpose to include the voices of women in coherence with the content: “in general women, feminism and everything we could say is a recent topic in history […]. I think that if we see gender history or content related to women in class, it has already been discriminated because it should not be apart from the rest […]” (Diana, 2018).

Discussion and Conclusions

In regards to the professional formation the participants have received, all of them have been instructed based on traditional logic where the State's hegemony and masculine leadership has prevailed (Apple, 1998, 2014; Giroux, 1998; McLaren and Kincheloe, 2015). Considering critical theory, the powerful social structures promote that some content is privileged over other, these being controlled by the patriarchal protagonism and power (Pagès and Sant, 2012; Ortega-Sánchez and Pagès, 2018). As the participants argue, the contents that control the scholastic structures perpetuate those which produce and reproduce privileges, and also male undertakings over the inclusion of a diversity of protagonists (Donoso-Vázquez and Velasco-Martínez, 2013; Aguilar Ródenas, 2015; Balteiro and Roig-Marín, 2015).

All of the participants agree that the school promotes the production and reproduction of national values and national belonging (Donoso-Vázquez and Velasco-Martínez, 2013; García Luque, 2013; Díaz de Greñu and Anguita, 2017), where men who have had political, military and economic power are the ones who play a leading role and arise as builders of historical processes (Woyshner, 2002; Rodríguez Martínez, 2014; Crocco, 2018). It is claimed that educational centers as well as history teaching looks to perpetuate the “tradition” such as hegemonic axis, which experiments little variability and furthermore does not allow the inclusion of new narratives and characters (Barton, 2002; Foucault, 2008; Scott, 2008).

Hence it has to be understood that the national curriculum that the participants work with is built from hegemonic and State official structures where knowledge is understood as external to people. (Vega, 2002; Bickmore, 2008; Díez Bedmar, 2015). As Foucault (2008) states, the power structures have normalized roles and gender structures. Thus, the curriculum produces and reproduces the hierarchies that have positioned women under the actions of men that have had power in society (Bonilla and Martínez, 1992; Scott, 2008; Pagès and Sant, 2012; Díaz de Greñu and Anguita, 2017).

As the participants claim, women, and their history are presented in an anecdotal manner and as annex to the official history (Marolla, 2019a,b). The few times these are presented, it is from a domestic and private points of view being their actions subsidiary to the ones powerful men have performed (Tomé and Rambla, 2001; Barton, 2002). Appleby et al. (1994), Tomé and Rambla (2001), Barton (2002), Donoso-Vázquez and Velasco-Martínez (2013), and Crocco (2018) have claimed that teaching has excluded women and their history in order to perpetuate unequal social structures; giving privilege to a passive perspective on the participation of the individual and the changes that they could make.

Concerning professional formation, the participants state that they have not received the ideal tools to include, problematize and work women's narrative. While they claim that they have knowledge that there are sources that could be sought for, they have not received instruction in didactics that allows inclusion. The teaching practices, in that sense, are performed from endocentric conceptions that provoke the production and reproduction of gender inequality.

The practices that have been performed, the participants recognize, perpetuate gender structures (Marolla, 2019b) where they have raised the actions of men over the actions and protagonism of women in history (Benavente and Núñez, 1992; Crocco, 2008; Pagès and Sant, 2012; Fernández and Johnson, 2015; Ortega-Sánchez and Pagès, 2018). Regardless, the teachers argue that they have made some changes making women visible within the content seen in class. This, however relevant, has been framed in the traditional gender structures. Women not having a major participation in the construction of history has continued reproducing and normalizing.

The participants comment that in their first year of teaching, it has been complex to be able to modify the curriculum forced by the educational centers and the State, as well as the pressure of the standardized tests. However, they argue that in schools there are feasible spaces to be transformed with the objective of including and working with women's narratives, their protagonism, and their actions (Lerner, 1979; McIntosh, 1983; Pagès and Sant, 2012; Marolla, 2019b). The participants add that inclusion should be done with the purpose of transforming all the androcentric structures of history and social sciences teaching (Grever, 1991; Volman et al., 1993; Azorín, 2015; Fernández and Johnson, 2015).

The participants, faced with the aforementioned matters, claim that in their first teaching year they have made efforts to generate brief disruptions in tradition and unequal gender structures. They claim that one of the strategies is that history teaching should be taught as something close to the students, stressing how the teaching processes can be related to everyday life (Subirats and Brullet, 1988; Subirats, 2001; Aubert et al., 2010; Donoso-Vázquez and Velasco-Martínez, 2013; Díez Bedmar, 2015). As Heimberg (2005), Pagès and Sant (2012), and Ortega-Sánchez and Pagès (2018) say, history and social sciences teaching must allow students to identify with the processes and this way actively participate in society (Heimberg, 2005; Del Olmo Pintado and Gutiérrez Sánchez, 2006; Aguilar Ródenas, 2015; Fernández and Johnson, 2015).

It is important to mention that the participants agree that women's inclusion could be promoted so the girls feel identified with the actions of their peers over history (Vázquez, 2003; Scott, 2008; Fernández and Johnson, 2015; Marolla, 2019a,b). This would in the service of creating agency where the female students could understand that they are also developers and protagonists of historical processes (Alonso Gutiérrez, 1998; Vavrus, 2009; Stanley, 2010; Crocco, 2018; Marolla, 2019a). Not only female students could generate agency regarding their participation in history but male students could understand that history has been built stressing masculine over feminine protagonism, situation that answers to hegemonic interests (Levstik and Groth, 2002; Heimberg, 2005; Vavrus, 2009; Crocco, 2010; Balteiro and Roig-Marín, 2015). This empowerment would imply that male and female citizens participate socially to fight against gender inequality (Álvarez de Zayas and Palomo Alemán, 2002; García Luque, 2013; Fernández and Johnson, 2015; Marolla, 2019b).

Lastly, it is relevant that the participants agree, in tandem with Casas (1999), Subirats (2001), Thornton (2010), and Aguilar Ródenas (2015), by claiming that in their first year of teaching practice it has been complex to include women and their history, and they have made efforts to disrupt the pressure in the educational centers and the official curriculum. Nevertheless, these efforts have not produced the expected results since they stress that: firstly, they do not have the necessary tools or formation in didactics; secondly, their little experience in teaching practices leads to them being restricted to what is enforced official programmes. Thusly agreeing with Hahn (1996), Woyshner (2002), Bickmore (2008), and Hess (2002) who state that the formation and reflexive practices are fundamental to generate educational transformations.

Amongst the main conclusions that can be obtained, the relevance of research concerning the initial teaching practices is stressed. As the participants have manifested they agree on the importance of women's inclusion and their history in teaching, even so, they express a number of worrying situations to those who work in teaching teachers.

This way the teachers express criticism of the formation they have had. These comments are in tandem with the studies of Pagès and Sant (2012), Ortega-Sánchez and Pagès (2018), and Marolla (2019a), who, in a similar way, express what was said in the research; that the content and processes that have been learnt in their programmes are ruled by traditional structures of history. These structures are based in male protagonism stressing their actions and narratives over the rest of the characters.

Women's inclusion and their history are carried out from anecdotal positions or as annex data to official history with men as protagonists. History teaching is presented from patriarchal points of view, being women the spectators of the tales, narratives, and the actions. This means that the students identify that history has been built from the actions performed by men where women have had neither participation nor interference in the social progress.

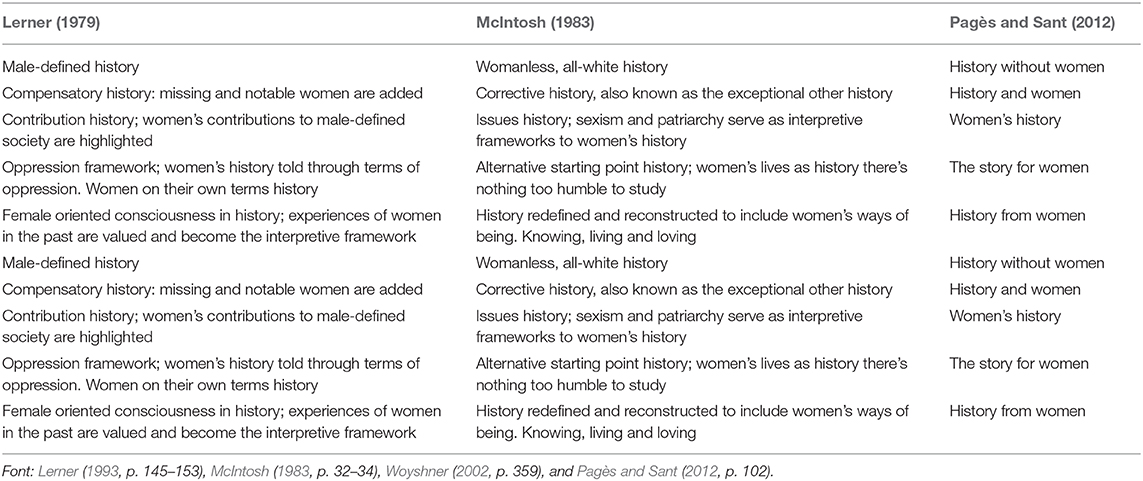

Lerner (1979), McIntosh (1983), and Pagès and Sant (2012) propose a work model for the understanding of teaching practices from a perspective of gender and inclusion of women in teaching. This model can be summarized in the following stages (Table 2).

These models agree that, in general, history teaching does not include women and their history. Except in those areas and tasks that have been identified as “women's activities”; no historic narratives have been recovered, being androcentric history that includes them in an anecdotal and subordinate way in the history that includes masculine protagonists. The model proposes their inclusion from the transformation of traditional practices and structures (Grever, 1991; Volman et al., 1993; Aguilar Ródenas, 2015; Díez Bedmar, 2015). Inclusion from those perspectives would collaborate with the recognition of the students' particularities, supporting identification with the past and their position in today's society (Heimberg, 2005; Del Olmo Pintado and Gutiérrez Sánchez, 2006; Azorín, 2015; Fernández and Johnson, 2015).

Thus the participants add that in their professional formation they have not worked with content and processes linked to women's history, their narratives and voices. On the contrary, it has been focused in traditional content with powerful male protagonists, because of politics, economy and/or military aspects. Hence they agree that the professional formation they have had has come from patriarchal and androcentric structures making women as well as those who represent social diversity invisible.

In this context, the participants also comment that the didactic courses have not prepared or formed them to create spaces that include women and their history. On the contrary, the formation has focused on preparing them to work and teach from the status quo. Although they recognize the importance to include women and their voices, so much that boys and girls could identify themselves as developers of their own history, as to generate social transformations to inequality, they do not have the tools or the reflection concerning reflexive practices to propose changes to the educational centers and the compulsory programmes.

It is crucial that the professional formation is recognized by the importance to transform the traditional viewpoint of history and social sciences teaching. All the programmes should be reformed from a logic that not only promotes the questioning of patriarchal structures, gender, race, and social class inequality, but that it is also thought to promote changes in teaching practices, official programmes, and the educational centers impositions.

Didactics comes to be crucial as an axis to create spaces of transformation in current teaching practices. The context in which one works, in general, is going to be problematic which is why the teaching staff should have the necessary competences to face problems, as well as to suggest solutions and transformations. Here is that didactics, as the teaching staff recognizes, becomes essential in order to be reflective– in practice (Donoso-Vázquez and Velasco-Martínez, 2013; Marolla and Pagès, 2015), so to count with enough tools that allow teachers to face the different contexts.

One of the main advantages of women's inclusion and their narrative in history teaching is recognized when stating that girls could identify themselves with historic characters seen in class, assuming that they are also part and developers of historical processes. In this way they could empower themselves when faced with social issues and inequality, therefore, helping them to participate in generating changes in the context of social justice.

Lastly, the teaching staff recognizes the importance of their teaching work in the context of a socially troubled society. They claim that their role is more than delivering content and that the students continue under an economy based educational logic (Pagès and Sant, 2012; Azorín, 2015; Díaz de Greñu and Anguita, 2017; Ortega-Sánchez and Pagès, 2018; Marolla, 2019a,b) but that their main function is to deliver the competences and tools so that the students can feel empowered by and actively participate in the fight against the inequality that they are part of.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets for this article are not publicly available because the data sets are not definitive and are in the process of being extended. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to amVzdXNtYXJvbGxhQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of the Americas. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

JM-G: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review, and editing supervision. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I thank Professor Monserrat Mena for all her work building the English version of this manuscript.

References

Aguilar Ródenas, C. (2015). Igualdad, género y diversidad sexual en la Formación Inicial de Maestro/a en la Universidad Jaume I (UJI). Temas Educ. 21, 77–96.

Alonso Gutiérrez, A. M. (1998). “El sexismo en el aula. Los valores y la didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales,” in Actas del IX Simposium de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales (Lleida: University of Lleida), 309–316.

Álvarez de Zayas, R. M., and Palomo Alemán, A. (2002). Los protagonistas de la historia. Los alumnos “descubren” que los hombres comunes también hacen historia. Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales 1, 27–39.

Álvarez-Gayou, J. L. (2003). Cómo hacer investigación cualitativa. Fundamentos y metodología. Mexico City: Paidós.

Apple, M. (2014). Official Knowledge. Democratic Education in a Conservative Age. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203814383

Arnal, J., Del Rincón, D., and Latorre, A. (1994). Investigación educativa. Fundamentos y metodología. Barcelona: Labor.

Asher, N., and Crocco, M. S. (2001). Engendering multicultural identities and representations in education. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 29, 129–151. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2001.10505932

Aubert, S., Duque, E., Fisas, M., and Valls, R. (2010). Dialogar y Transformar: Pedagogía crítica del siglo XXI. Barcelona: Graó.

Azorín, C. M. (2015). “Análisis de la política de género en España: hacia una educación inclusiva y coeducadora,” in Investigación e innovación: una constante necesaria en la formación del profesorado, eds. A. B. Mirete and R. Nortes (Murcia: University of Murcia), 1–12.

Balteiro, I., and Roig-Marín, A. (2015). “Reflexiones sobre la integración de cuestiones de género en la enseñanza universitaria,” in Investigación y propuestas innovadoras de Redes UA para la mejora docente, eds J. D. Álvarez Teruel, M. T. Tortosa and N. Pellín (Alicante: University of Alicante- Instituto de Ciencias de la Educación (ICE)), 851–870.

Barton, K. (2002). Masculinity and schooling. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 30, 306–312. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2002.10473198

Benavente, J. M., and Núñez, A. (1992). “El androcentrismo en la enseñanza de la historia y la geografía,” in Del silencio a la palabra, ed M. Moreno (Madrid: Ministerio de Asuntos Sociales, Instituto de la Mujer), 153–176.

Bengoa, J. (1996). “El Estado desnudo. Acerca de la formación de lo masculino en Chile,” in Diálogos sobre el género masculino en Chile ed S. Montecino (Santiago: Universidad de Chile), 63–82.

Bickmore, K. (1999). Elementary curriculum about conflict resolution: can children handle global politics? Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 27, 45–69. doi: 10.1080/00933104.1999.10505869

Bickmore, K. (2002). How might social education resist heterosexism? Facing the impact of gender and sexual ideology on citizenship. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 30, 198–216. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2002.10473191

Bickmore, K. (2008). “Social justice and the social studies,” in Handbook of Research in Social Education, eds L. Levstik and C. Tyson (New York, NY: Routledge), 155–171.

Bonilla, A., and Martínez, I. (1992). “Análisis del currículo oculto de los modelos sexistas,” in Del silencio a la palabra. Coeducación y reforma educativa, ed M. Moreno (Madrid: Ministerio de Asuntos Sociales, Instituto de la Mujer), 60–92.

Bullock, A., and Stallybrass, O. (1977). The Fontana Dictorionary of Modern Thought. London: Fontana.

Casas, M. (1999). El concepto de diferenciación en la enseñanza de las ciencias sociales. Íber 6, 21, 23–29.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2007). Research Methods in Education. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203029053

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. California: Sage.

Crocco, M. S. (2008). “Gender and sexuality in social studies,” in Handbook of Research in Social Education, eds L. Levstik and C. Tyson (New York, NY: Routledge), 172–196.

Crocco, M. S. (2010). “Using literature to teach about others, the case of shabanu,” in Social Studies Today: Research and Practice, ed W. Parker (New York, NY: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group), 175–182.

Crocco, M. S. (2018). “Gender and sexuality in history education,” in The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning, eds S. A. Metzger and L. McArthur Harris (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 335–364. doi: 10.1002/9781119100812.ch13

Crocco, M. S., and Libresco, A. (2007). “Gender and social studies teacher education,” in Gender and Teacher Education: Exploring Essential Equity Questions, eds D. Sadler and E. Silber (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 109–164.

Del Olmo Pintado, M., and Gutiérrez Sánchez, C. (2006). Identidad y educación. Una perspectiva teórica. Íber 47, 7–13.

Díaz de Greñu, D., and Anguita, R. (2017). Estereotipos del profesorado en torno al género y a la orientación sexual. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 20, 219–232. doi: 10.6018/reifop/20.1.228961

Díez Bedmar, M. C. (2015). Enseñanza de la historia en educación preuniversitaria y su impacto en la formación de identidades de género, repercusiones en la universidad. Clío Hist. Hist. Teach. 41, 35–64.

Donoso-Vázquez, T., and Velasco-Martínez, A. (2013). ‘Por qué una propuesta de formación en perspectiva de género en el ámbito universitario? Profesorado 17, 71–88.

Espigado, G. (2004). “Historia y genealogía femenina a través de los libros de texto,” in La ausencia de las mujeres en los contenidos escolares, ed C. Rodríguez (Buenos Aires: Niño y Dávila), 113–115.

Fernández Valencia, A. (2015). “Género y enseñanza de la Historia,” in Género y enseñanza de la Historia: silencios y ausencias en la construcción del pasado, eds. M. A. Domíngez Arranz and R. M. Sáez (Madrid: Sílex), 29–55.

Fernández, M. B., and Johnson, M. D. (2015). Investigación-acción en formación de profesores: Desarrollo histórico, supuestos epistemológicos y diversidad metodológica. Psicoperspectivas 14, 93–105. doi: 10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol14-Issue3-fulltext-626

García Luque, A. (2013). Igualdad de género en las aulas de la educación primaria: bases teóricas y guía orientativa de recursos. Jaén: University of Jaén.

Gillborn, D. (1990). ‘Race’, Ethnicity and Education: Teaching and Learning in Multi-Ethnic Schools. London: Unwin Hyman/Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203400265

Giroux, H. (1998). “Las políticas de educación y cultura,” in Sociedad, Cultura y Educación, eds H. Giroux and P. McLaren (Madrid: Niño y Dávila), 79–86.

Grever, M. (1991). Pivoting the centre. Women's history as a compulsory examination subject in all Dutch secondary schools in 1990-1991. Gender Hist. 3, 65–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0424.1991.tb00112.x

Hahn, C. (1996). Gender and political learning. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 24, 8–36. doi: 10.1080/00933104.1996.10505767

Harris, I. (1996). From world peace to peace in the hood: peace education in a postmodern world. J. Just Caring Educ. 2, 378–395.

Heimberg, C. H. (2005). “L'alterité et le multiculturalismo au coeur de l'histoire enseignée,” in Enseñar ciencias sociales en una sociedad multicultural, eds C. García Ruiz, E. Gómez Rodríguez, M. D. Jiménez, J. M. Martínez López, and C. Moreno Baró (Almería: University of Almería), 17–32.

Hess, D. (2002). Teaching controversial public issues discussions: learning from skilled teachers. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 30, 10–41. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2002.10473177

Hutchinson, E. (1992). El feminismo en el movimiento obrero chileno: la emancipación de la mujer en la prensa obrera feminista, 1905–1908. Proposiciones 21, 45–68.

Lerda, S., and Todaro, R. (1997). ¿Cuánto cuestan las mujeres?, un análisis de lo labores por sexo. Sociol. Trabajo 30, 3–23.

Lerner, G. (1979). The Majority Finds It Past: Placing Women in History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Levstik, L., and Groth, J. (2002). Scary thing being an eighth grader: exploring gender and sexuality in a middle school US history unit. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 30, 233–254. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2002.10473193

Marolla, J. (2019a). La didáctica de las ciencias sociales y el problema de la ausencia de las mujeres y su historia. Reflexiones en torno a un estudio de casos para transformar las prácticas de enseñanza. Revista Electrón. Educare 23, 1–25. doi: 10.15359/ree.23-1.8

Marolla, J. (2019b). La inclusión de las mujeres en las clases de historia: posibilidades y limitaciones desde las concepciones de los estudiantes chilenos. Revista Colombiana de Educación 78, 1–24. doi: 10.17227/rce.num77-6549

Marolla, J., and Pagès, J. (2015). Ellas sí tienen historia. Las representaciones del profesorado chileno de secundaria sobre la enseñanza de la historia del as mujeres. Clío y Asociados 21, 223–236.

McLaren, P., and Kincheloe, J. (2015). Pedagogía crítica. De qué hablamos, dónde estamos. Barcelona: Graó.

Miles, B. M., and Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Moreno, M., and Sastre, G. (2003). “Visión de la enseñanza desde otra identidad,” in Relaciones de género en psicología y educación, eds M. Dolores Villuendas and Á. G. López (Madrid: Comunity of Madrid), 65–76.

Ortega-Sánchez, D., and Pagès, J. (2018). Género y formación del profesorado: análisis de las guías docentes del área de didáctica de las ciencias sociales. Contex. Educ. Revista Educ. 21, 53–66. doi: 10.18172/con.3315

Pagès, J., and Sant, E. (2012). Las mujeres en la enseñanza de la historia: ¿Hasta cuándo serán invisibles? Cad. Pesq. Cdhis 25, 91–117.

Pinochet, S. (2015). Doctoral Dissertation. Profesor, profesora ¿Por qué los niños y las niñas no aparecen en la historia? Concepciones del profesorado y el alumnado sobre la historia de la infancia. Barcelona: Autonomous University of Barcelona.

Rodríguez Gómez, G., Gil Flores, J., and García Jiménez, E. (1999). Metodología de la investigación cualitativa. Archidona: Aljibe.

Rodríguez Martínez, C. (2014). La invisibilidad de las mujeres en los contenidos escolares. Cuadernos Pedagogía 447, 32–35.

Smyth, J. (1989). Developing and sustaining critical reflection in teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 4, 2–9. doi: 10.1177/002248718904000202

Spivak, G. (2012). In Other Worlds: Essays in Cultural Politics. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203441114

Stanley, W. (2010). “Social studies and the social order, transmission or transformation?,” in Social Studies Today: Research and Practice, ed W. Parker (New York, NY: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group), 17–24.

Subirats, M. (2001). “¿bewQué es educar? De la necesidad de reproducción a la necesidad de cambio,” in Contra el sexismo: coeducación y democracia en la escuela, eds A. Tomé and X. Rambla (Madrid: Síntesis), 17–21.

Subirats, M., and Brullet, C. R. (1988). Rosa y Azul. La transmisión de los géneros en el sistema educativo. Madrid: Woman's Institute.

Thornton, S. (2010). “Silence on gays and lesbians in social studies curriculum,” in Social Studies Today: Research and Practice, ed W. Parker (New York, NY: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group), 87–94.

Tomé, A., and Rambla, X. (2001). Contra el sexismo. Coeducación y democracia en la escuela. Madrid: Síntesis. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

Vavrus, M. (2009). Sexuality, schooling, and teacher identity formation: a critical pedagogy for teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 25, 383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.002

Vega, C. (2002). “La mujer en la historia y la historia de las mujeres,” in Mujer y educación, eds A. González and C. Lomas (Barcelona: Graó), 13–20.

Volman, M., ten Dam, G., and van Eck, E. (1993). Girls in the educational research discourse. Comenius 13, 196–217.

Wolcott, H. (1994). Transforming Qualitative Data: Description, Analysis and Interpretation. London: Sage.

Keywords: gender education, teacher education, citizenship education, women history, social thinking

Citation: Marolla-Gajardo J (2020) The Challenge of Women's Inclusion for Novel Teachers. Case Study in a Teacher Educator Public University. Front. Educ. 5:91. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00091

Received: 17 March 2020; Accepted: 25 May 2020;

Published: 24 June 2020.

Edited by:

Esther Sanz De La Cal, University of Burgos, SpainReviewed by:

Manpreet Kaur Bagga, Partap College of Education, IndiaGloria Gratacos, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Copyright © 2020 Marolla-Gajardo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jesús Marolla-Gajardo, am1hcm9sbGFAdWRsYS5jbA==

Jesús Marolla-Gajardo

Jesús Marolla-Gajardo