- Educational Leadership, University of Connecticut, Mansfield, CT, United States

Black women experience the burdens of gendered racism in their roles as school leaders, yet little is known about how these leaders cope with those experiences or how such coping might impact their ability or desire, to persist and thrive in such positions. This phenomenological study examined the experiences of 10 Black female school leaders and how they coped with gendered racism and the costs associated with doing so. Findings show coping occurred through both adaptive and maladaptive strategies, which we label as “more affirming” or “less affirming,” to highlight how both enabled participants to persist in their leadership roles. More affirming (i.e., adaptive) strategies included reliance on faith, social relationships and professional networks, and advocacy roles to confront, manage, and problem solve around their experiences of gendered racism. Less affirming (i.e., maladaptive) strategies included denial or avoidance, buffering and boundary setting, and in a few cases, exit. Further, findings revealed the costs or tolls borne by participants included internalizing gendered racism, doubting leadership skills and competence, anger at having to operate in a gendered racist context, and resignation. By acknowledging and naming the gendered racism Black female school leaders face and the energy required to exert to cope with it, these findings highlight the need to discuss gendered racism in educational leadership and professional development programs. Further, these findings suggest anti-racist practices by White allies, including shifting the burden of gendered racism to them, is critical to the disruption of practices privileging Whiteness in educational leadership.

Introduction

Racial and gender discrimination in school leadership is widely known to exist (e.g., Shakeshaft, 1989; Peters, 2010; Muñoz et al., 2014; Jean-Marie et al., 2016), and can impact who gets access to these roles and their treatment within them (Cognard-Black, 2004; Tillman, 2004; Myung et al., 2011). Scholars recognize addressing negative discourses around race and gender are necessary for future generations of Black women in school leadership (Wrushen and Sherman, 2008). What has not been examined in detail, but we sought to accomplish in this research, was how Black women experiencing gendered racism in their roles as school leaders cope with those experiences. Further, as noted in previous work examining coping with gendered racism (Lewis et al., 2016), we sought to highlight the costs associated with coping and the extent those costs impact Black female school leaders in their roles.

As scholars interested in using our research to engage in, and promote, anti-racist and anti-patriarchal approaches, it is our hope that by focusing on these issues, we can provide scholars, educators, and practitioners insights into the strengths and struggles of Black women educational leaders. Further, we hope this work will challenge these same individuals to seek change at the individual and organizational level so facing and coping with gender racism is no longer a burden placed on Black women or other minoritized groups.

Theoretical Background

Gendered Racism/Intersectionality

We ground our work using an intersectional frame as the influence of sexism and racism cannot be parceled out as discrete experiences for our participants (Crenshaw, 1989; Collins, 1991). Intersectionality provides “critical insight” (p. 2) that race, gender, ethnicity and other identities “operate not as unitary, mutually exclusive entities, but as reciprocally constructing phenomena that in turn shape complex social inequalities” (Collins, 2015, p. 2). Intersectionality allows us to call attention to social identities often treated as marginal or invisible, while allowing us to highlight the “complex nature of power” (p. 5) and note the “gap between social categorization and the complexity of intersubjective experience” (p. 5) as there is not one social label that can help us explain the complexity of an individual's lived experience (Harris and Leonardo, 2018). In the intersectional frame, Essed (1991) advances gendered racism to examine the intertwining influences of sexism and racism to describe the experiences of Black women.

Gender, Race, and School Leadership

School leadership has historically been defined as the domain of men in general, and White men in particular (Boris-Schacter and Langer, 2006). Some Black women, as a result of differing lived experiences including exclusion from “established power structures” (Peters, 2012; Santamaría and Jean-Marie, 2014; Newcomb and Niemeyer, 2015, p. 787) are shown to lead differently than their White counterparts, male or female. For example, when leading in lower resourced and/or more urban settings, Black women are known to approach leadership from an ethic of care (Dillard, 1995). This type of nurturing and supportive leadership has been described as “othermothering” (Bass, 2012; Newcomb and Niemeyer, 2015). Further, they are more likely to be driven by social justice goals and spirituality (Newcomb and Niemeyer, 2015). Spirituality can be a driving influence of their leadership too, as some describe “heeding the call” (Newcomb and Niemeyer, 2015, p. 792) to serve as leaders (Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010). They also tend to lead in more culturally competent ways (Wood and Eagly, 2012; Newcomb and Niemeyer, 2015) and emphasize “shared” forms of leadership, approaches shown as successful in fostering continuous improvement (e.g., Hallinger and Heck, 2009).

While the evidence suggests Black women are likely to engage in leadership in productive ways (Jean-Marie, 2013), they are also more likely to experience “complex and intersecting racialized and gendered role expectations above and beyond those expected of other administrators” (Reed and Evans, 2008, p. 488) in their roles as school leaders. For example, the “double-jeopardy” hypothesis describes how Black women are punished for violating social roles stereotypically ascribed to both Black men and White women (Beal, 1969; Bell and Nkomo, 2001; Young and Skrla, 2003; Settles, 2006; Rosette and Livingston, 2012; Weiner and Burton, 2016; Burton and Weiner, 2016). Others argue Black female leaders receive responses mirroring those given to White males (Rosette et al., 2019) and thus are not penalized for such behaviors.

Jean-Marie's (2013) work about Black female principals found her participants, like many Black female school leaders, were placed in low performing schools and pigeonholed as “fixers” (Brown, 2005; McCray et al., 2007). In addition, they faced the “triple jeopardy” of gender racism and ageism by those they supervised, parents and community members, and their superintendents. They also experienced subtle biting comments about their capabilities to be successful and had to engage in additional work to access their leadership positions. As leaders, they actively coped with experiences gendered racism by forming a shared bond, supporting one another while also relying on their spirituality to recognize a higher calling to leadership.

One reason it is often incumbent on Black women to create their own support structures is that they are less likely to receive formal support (e.g., mentoring, networking) than their White or male colleagues (Peters, 2010; Muñoz et al., 2014) and face far more challenges. They are also less likely to be recognized for having “leadership potential,” and take longer to become school leaders (Cognard-Black, 2004; Peters, 2010; Myung et al., 2011). Once in leadership positions, they experience extra scrutiny in the role (Mendez-Morse, 2003; Boris-Schacter and Langer, 2006), receive lower performance evaluations (Rosette et al., 2019), have shorter tenures (Christman and McClellan, 2008), and experience higher stress levels (Peters, 2012). Yet they persist, which suggests a need to look at the strategies which enable and empower them to cope as well as the potential costs of such strategies. Reed (2012) highlights coping strategies used by these leaders that allowed them to be successful. “The actions of these leaders are in line with the literature that discusses a long-standing tradition of Black women school leaders making quiet, but steady advancements on behalf of the children they serve” (p. 56).

Coping

Experiences of gendered racism are linked to negative health implications including increased psychological distress (see Lewis et al., 2017 for a review). Past research that has explored the coping strategies or attempts to manage internal and external demands (Folkman and Moskowitz, 2004) of Black people (e.g., Feagin, 1991; Daly et al., 1995; Shorter-Gooden, 2004; Benkert and Peters, 2005) has historically and problematically used inherently White measures. More recent research looks specifically at responses to racial microaggressions and the coping mechanisms individuals of color rely on (Neville et al., 1997; Utsey et al., 2002, 2007; West et al., 2010; Greer, 2011). For example, Lewis et al. (2013) note that individuals who experience gendered racism first evaluate the situation as stressful, make a secondary assessment to either engage in or opt out of addressing the situation (i.e., picking and choosing battles) and then utilize coping strategies. Those strategies included resistance (e.g., using your voice as power), collective (e.g., using support networks), and self-protective (e.g., Black superwoman or becoming desensitized).

Other literature focused on the experiences of racial microaggressions, categorize coping strategies as either adaptive or maladaptive (Utsey et al., 2008; Forsyth and Carter, 2012; Holder et al., 2015). Adaptive strategies empower the individual to confront racism, problem solve, reframe, or manage gendered racism (Harrell, 2000; Mellor, 2004; Forsyth and Carter, 2012; Vassilliere et al., 2016) and include leaning on relationships (Harrell, 2000), spirituality and faith (Thomas et al., 2008), and setting boundaries (Franklin and Boyd-Franklin, 2000; Holder et al., 2015). Maladaptive strategies are those which enable an individual to disconnect or attempt to remove gendered racial experiences and stressors (White et al., 2019) via avoidance and disengagement (Lewis et al., 2013), denial (Mellor, 2004; Thomas et al., 2008), or hypervigilance and preparation (Utsey et al., 2008; Holder et al., 2015).

We build on this existing scholarship regarding the experiences of Black women in school leadership and the work of Lewis et al. (2013) regarding how Black women cope with gendered racism. However, we also wish to trouble the idea these strategies are either adaptive or maladaptive (Forsyth and Carter, 2012; White et al., 2019) as both are used by individuals who successfully persist and cope. Thus, for our purpose here we name these strategies as “more affirming” and “less affirming.” We do so to highlight the potential difference in the psychic and physical costs experienced when utilizing them. Further, we also take into consideration whether our participants' experiences of coping align with the “Strong Black Woman” race-gender schema (Woods-Giscombé, 2010), a “set of cognitive and behavioral expectations for African-American women, notably standing up for oneself, exhibiting self-reliance, and taking care of others” (Watson and Hunter, 2016, p. 425). Our study was guided by the following questions:

1. How do Black women in school leadership cope with the challenges of gendered racism?

2. What are the tolls experienced by Black women as they do so?

In the sections to follow, we outline the methods used to guide our study, including detailed discussion of our analytic process and how we worked to ensure trustworthiness of these analyses. We then share a table of themes and supportive codes and a detailed discussion of our findings. Finally, we examine how our findings support and advance current literature regarding Black women's experiences in coping with gendered racism in educational leadership.

Methods

This research was supported by a grant from President Obama's White House's Advancing Equity for Girls and Women of Color initiative. In keeping with other exploratory studies examining how participants coped with gendered racism (e.g., Lewis et al., 2016), we took a phenomenological approach (Moustakas, 1994; Creswell and Poth, 2018) to this research. Phenomenology moves researchers to examine participants' lived experiences through their descriptions, stories, and narratives (Moustakas, 1994). The larger purpose being to condense these individual experiences to a description of the universal essence of a given set of experiences (i.e., phenomenon) (Creswell and Poth, 2018). As we discuss in more detail below, we modeled our data analytic approach largely after Lewis et al.'s (2016) likewise phenomenological study of gendered racial microaggressions on Black women at a predominately White university and thus used a dimensional analysis (Charmaz, 2014) with both inductive and deductive coding. Finally, it is worth noting that part of the power of phenomenology and one reason we selected it, particularly in the context of capturing and describing participants' recollections and stories via “thick” descriptions (Finlay and Agresti, 1986), is that it calls upon the researchers to engage in “bracketing” and to acknowledge and suspend one's own beliefs and assumptions regarding the phenomenon of interest.

Sample

We utilized a purposeful criterion-based sampling technique (Patton, 1990) to recruit school administrators (principals and assistant principals) who self-identified as Black women (n = 10). Participants came from three U.S. states in the Northeast and were recruited via social and professional networks to support trust building and relatability given the sensitive nature of the interviews (Dickson-Swift et al., 2007). Our sample included one high school assistant principal, two middle school principals, three elementary principals, one elementary school assistant principal, one Headstart principal, and one principal of a k-12 charter school. The participants led schools in a variety of settings, including urban, suburban and rural school districts across the Northeast. They averaged 16 years of experience in education and three had more than 20 years of experience. The women varied in age from 33 to 56, all were married with children and in heterosexual relationships.

Data Collection

In keeping with other phenomenological studies looking at gender racism and Black Female leaders, we favored interviewing as our data collection approach (Weiner et al., 2019). Participants were provided a copy of the institutionally approved informed consent form prior to the first scheduled interview. Upon our first scheduled interview, all participants reviewed the informed consent form, asked questions if desired and agreed to participate and be recorded. Participants were interviewed three times over the year for ~1 h each interview. The interview structure was based on Seidman (2006) and focused on the participants' experiences of gendered racial discrimination, the first interview centered around their professional history and experiences in preparation programs, the second focused on their current position, and the third on their future work and reflections on their experiences. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. While we address our positionality more below, there are always power dynamics present during interviewing (Seidman, 2006) and we were particularly sensitive to the racial dynamics given our identities as White women.

Data Analysis

As suggested by Charmaz (2014) when using a dimensional analysis, we first engaged in open coding ultimately engaging with both inductive and deductive coding (Boyatzis, 1998). We began by randomly selecting four interviews from the first round for research team members to independently code and discuss. We then independently began our coding by each writing gerund-based phrases (e.g., converting “So it's really my faith, that gives me the resilience to stay at it.” to “My faith really giving me the resilience to stay at it.”) to describe the participants' words (Charmaz). We then wrote interpretations of the phrase in the context of the larger piece of text as the basis for the codes e.g., “The participant feels her faith is a source of her resilience in the role”). We then met to discuss and refine our understandings into an initial set of codes (e.g., “Coping Mechanisms, “Resistance”, and “Tolls”). After, we applied these codes to other interviews from the same collection round, generated larger themes into which we sorted the data, and then used the same process across the other interviews.

For our deductive codes, we used work on coping and coping for Black women in particular (e.g., Utsey et al., 2008; Forsyth and Carter, 2012; Lewis et al., 2013; Holder et al., 2015; DeCuir-Gunby et al., 2019) to support the next steps in the dimensional analysis, mapping and axial coding (Charmaz, 2014). All interviews were again recoded. Researchers met frequently to discuss emergent findings and work to ensure reliability and robust conceptualization. As an example, in the independent coding stage, one of us coded interview data around leaving a leadership position as a cost to coping with gendered racism in educational leadership, while the other coded leaving as a less-affirming coping strategy, but not a cost. We then engaged in discussions of these coding differences, returned to the literature and to our data to understand how our participants made meaning of leaving their positions.

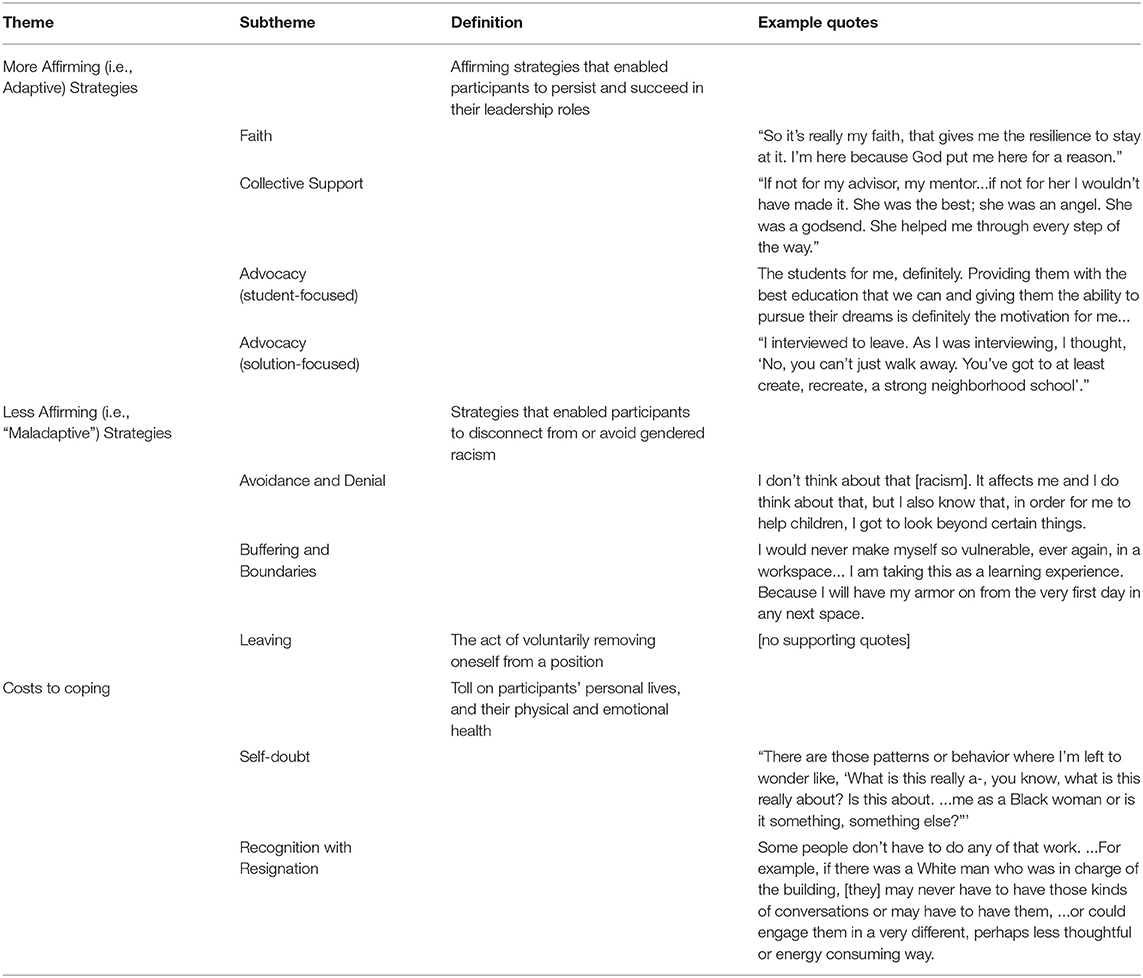

We established credibility of our findings as detailed by Lincoln and Guba (1986), first by prolonged engagement with our participants through 3 h long individual interviews with each participant over the course of 1 year. Second, participants were also sent their transcripts and included in discussions of initial findings for the purposes of member checking (Maxwell, 1992). Transferability of our findings was established by providing detailed descriptions of our themes and relevant quotes in support of those themes (see Table 1). All participants were identified using pseudonyms and they provided consent to have their quotes included in the discussion of findings.

Positionality

As White women who examine issues of gender bias and leadership in our research, we had previously not examined gendered racial discrimination. We came to this work while studying aspiring principals as we were made aware of the disparities in messaging and opportunities participants received based on their gender and/or racial identities (Weiner and Burton, 2016). This work, along with readings and discussions with participants exposed us to the ways racial discrimination and gender bias operate in the school leadership space. We are committed to using our research to make leadership more inclusive and have expanded our work to that end. In this way, the “choice” we have to engage in this work is a form of privilege which we must recognize along with other forms of our privilege, including race, gender identity, class, and academic background. These shape our beliefs and views, and also provide a certain level of power and access. We recognize a need to continually reflect on these privileges, to self-analyze, and then act. We also recognize our backgrounds impacted how we interacted with participants during interviews and vice-versa, as well as how we made sense of the data. While we have experienced gender discrimination, we do not claim to understand the experiences of our participants. Instead, intend to use our access to share the powerful experiences and resilience of our participants and to challenge the racist and gender discriminatory institutional structures in which we participate (Scheurich and Young, 1997).

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, though robust in terms of the recommendations for phenomenology (Creswell and Poth, 2018), our sample size was still small with women who held different types of school leadership positions in different kinds of schools and districts. As such, some of the contextual nuances of being in a particular geographic location (e.g., urban center vs. rural district) or serving in a particular kind of learning environment (e.g., middle school vs. head start program) was not captured. Future studies with larger, and perhaps more uniform, samples might be helpful to better understand how these contextual factors also play a role in the coping mechanisms available to Black female school leaders and the impact of these strategies. Second, to build our sample we focused solely on identity issues related to a singular race (Black) and gender (female). Future studies that explore a broader range of intersecting identities (e.g., ethnicity, ability, language, sexuality; O'Malley and Capper, 2015) would be helpful and enhance our understanding of the nuanced experiences of Black female school leaders. Finally, despite our efforts to invite participants into the larger research conversation, our approach was more traditional, and the interviewers were of a different race than the participants. Together, the elements bring up questions about participants' comfort sharing their truth as well as our ability to interpret in ways aligned with their experiences. With that said, and following the work of Moorosi et al. (2018), we began our interviews by talking about our backgrounds and why, as White women, we were interested in their experiences and conducting this research. While this approach cannot change the nature of privilege and how it operates in researcher-participant relationships, it does facilitate researchers' ability to “be reflexive on our positionality and in taking the ‘political responsibility' to speak for those we represent” (Moorosi et al., 2018, p. 154). To further support these efforts, a more participatory methodology would provide participants more control and ownership over their narratives and is a direction we hope to move in the future. We look forward to seeing others do the same.

Findings

More Affirming (i.e., Adaptive) Strategies

Grounding our findings in the literature, we utilize the terms adaptive and maladaptive (Utsey et al., 2008; Forsyth and Carter, 2012; Holder et al., 2015; DeCuir-Gunby et al., 2019) but shift to call them “affirming” or “less affirming” to highlight the ways both types of strategies were often effective in enabling our participants to persist and succeed in their leadership roles.

Turning first to what we refer to as more affirming (i.e., adaptive) strategies, our participants relied on faith, social relationships and professional networks, and advocacy roles to confront, manage, and problem solve around their experiences of gendered racism. Consistent with the literature, these strategies empowered the women to address instances of racism.

Faith

When considering responses to stress that fostered strength or persistence, our participants described the importance of faith in coping with the challenges of gendered racism in their experiences as principals. We describe faith-based coping as a belief in one's “calling” to a particular place or position as coming from God or finding confirmation of one's task in what one believes. In this way, success was not measured by effectiveness in the realm of school but on the support and development of children. Michele clearly articulated this, “So it's really my faith, that gives me the resilience to stay at it. I'm here because God put me here for a reason.”

Nicole stated faith was a foundational part of her coping as she forged through adversity and challenge as a Black woman in educational leadership, “It can only be my faith. Because without it, I have nothing. I have nothing. Because none of it makes sense. I can't make it rational.” When addressing some of her more difficult days as a principal, Marissa too described faith and prayer as critical to get through those challenges and her wish to make meaningful impact on those she leads, “sometimes my only prayer is let me help somebody today. Let me help someone to be in a better position, you know if it's a family, if it's a teacher, if it's a custodian, just let me help someone today.” She drew strength from her faith and recognized that, despite the challenges she regularly faced, there was a higher calling to her leadership.

Another participant, Marlene, recognized how her faith helped her to shift the stress she experienced via challenges to her leadership to help center her on the meaningful work she accomplished through her leadership. “Faith is a very important part of it, part of me, and it helps to keep me in a place of not really holding on to things and, and letting it go and then really understanding like, ‘Well, how is it that you can help this situation?' Because it's not going to do anybody any good to say, ‘Oh, you know, you just don't like me because I'm a Black woman'.”

Rosa directly addressed the importance of faith as she directly confronted the gendered racism she experienced. “I can always say [regarding those who degrade her], ‘You don't have a final say. My God has the final say.' Of course, that could be a survival technique that we use because the buck can't stop at you because I don't trust you with it.” Here she acknowledges the importance of faith as a “survival technique” noting that without faith, she would relinquish her power to confront gendered racism to those who hold discriminatory views toward her.

Collective Support

All participants spoke of someone or several people who they leaned on and served as a source of strength or encouragement. For some, like Marisa, a mentor provided professional support, “If not for my advisor, my mentor…if not for her I wouldn't have made it. She was the best; she was an angel. She was a godsend. She helped me through every step of the way.” Others, like Michele, had a spouse who supported them, “I will say the other real motivator for me at the time was my husband. He was extremely supportive, and I think he probably saw it as something that I could really do, before I even really had the full confidence to do it.”

Most importantly however, many of the women spoke to how trusted colleagues, whether they be other Black women, colleagues of color, or other administrators, provided encouragement. Kamele commented, “I have two other principal friends. We call each other. I usually spend 10 to 15 min on my ride in talking to one of them. We talk every day. And we end our conversation with, ‘Okay, don't get fired'.” Similarly, Rosa noted, “I had my other, the administrator who was hired at the same time, I had her in the building but then I've always had my own little administrator crew…And they're Black and White.”

Sheila too relied on a fellow administrator, “I have another colleague who started with me, and we did everything together…and even on her roughest days, she'll be like, we can do this. We need to do this and this is why, so I have that.”

Several participants also credited these relationships with keeping them sane or from going crazy. Marlene shared,

…We talk frequently to try and help each other kind of understand,' ‘is this me? Is it other people? How can i impact that perspective? Is this something from a cultural standpoint? Is it something from a different mindset? What is…Help me unders-…Right now, i'm angry so i'm not able to really kind of understand. so she's that person in the mirror that i…sometimes able to say to her, “well, you know you have this perception of…” we can talk honestly…So then i shared with her how other people may see her…It is good to have somebody to talk to. It's like, i'm not crazy. I'm not.

Shelby too celebrated her fellow female Black administrators and how they helped her to not feel alone as well as how this reality decreased the pressure she felt to represent her race and gender in her responses,

Because I'm not the only administrator of color even in the building that day. They [faculty] have me, they have [Female administrator of color #2], and they have [Female administrator of color #3]. Their impression is not just based on their dealings with me. It's based on a broader spectrum of people, because even if they're not dealing with us, they're dealing with parents. At least they're not basing how they feel about a whole group of people on their interactions with me…can breathe a little bit.

Reinforcing Shelby's position regarding the importance of being connected with other Black female leaders, a few participants noted the potential for greater impact and support coming from reaching out to and connecting with other Black women in such roles. Janelle recalled the positive impact of a forum for minority principals had for her,

I joined a forum here, but that was helpful. It was folks of color talking about, “What is it like to be the person in the suit, but still this person, and what you bring?” That was just…it was an outlet. It was an opportunity. It was offline, but it was formalized in the sense that my superintendent knew about it. That they actually supported it financially for me to be a part of this forum, because we needed to talk about what it meant to be a leader of color, and what those complexities were, as it were. That provided an opportunity for us to kind of do that.

Expressing similar sentiments, Kamele reflected on her recent work building a collective support network with other administrators of color, “So next time something comes up, of course I'm going to remember I have something to call him about, and we just start building that…” However, she also recognized that her White colleagues appeared to, “do that better than we do. Maybe it's because it's a larger group of them or because some of them were in other, some of them have other friendships or relationships with people that are higher up in the district because they actually brought them here. So, they already have that.” Here Kamele highlights her need for social capital and how she might foster mutually beneficial relationships in the future.

Just knowing other women of color or having friendships was not enough to serve as a support mechanism, participants repeatedly emphasized the types of conversations necessary for these relationships to be meaningful and a source of encouragement. For Kamele, one such gathering of women lacked substance and she expressed frustration, “We didn't leave with a call to action. We didn't go deep enough into you know, why we need to be together. The conversation was a little lighter than I would have thought, and we haven't developed norms so that …” The need to unpack gendered racism in an in-depth way led her to seek out intentional conversations, “I didn't let them in as much because I was too busy, they were too busy, but now I can talk to them more and say, ‘This is what…This is…I'm gonna tell you this. Let me tell you what happened today. Does this about [sound] like bullshit to you,' and they can affirm like, ‘Yeah, that is.”

Advocacy

Despite the adversity and challenges to their leadership, our participants found ways to address those challenges using more affirming coping strategies. We broadly defined these strategies as advocacy approaches to coping. Subsumed under advocacy were strategies focused on helping and supporting students, families, and members of the community, or working toward solutions to address issues in the school or community. Sheila captured this sentiment, and was one a majority of our participants described, when she reflected on why she took up a leadership position in her school (leaving a position outside education), “I know there's a bigger purpose of why I'm doing what I'm doing.”

Student advocacy

This approach to coping, and for some participants their reason to persevere, was centered on providing support or making changes to the benefit of students and those within the community. Rosa reflected on the importance of being a Black woman in educational leadership, why she chose to work in her district, and how her identity impacted the students she led. She also noted how her students looked like, and had similar experiences to, her own children. “I'm thinking about spaces that have children who look like me. Who need to see me. You know what I mean? I'm looking for places that aren't too large, because then you just feel like a cog in the wheel. And something that's not too far away from my own children, because they need me too.”

When considering why she entered educational leadership, these sentiments were in the forefront of Sheila's thinking. Further, she understood that empowering those in the community was critical to make change.

I didn't really start really thinking about it until I got into a leadership role and seeing how that could influence but at the same time we have to find ways of supporting families, not use it as an excuse or a crutch either, because I struggle with that personally. It's like, I get you had a bad experience, but now I'm telling you I'm going to help you and support you so you can break that cycle in the family.

Terri also described the joy she derived from seeing her students succeed, noting their successes provided her the motivation to persist despite the challenges she faced in her role. “The students for me, definitely. Providing them with the best education that we can and giving them the ability to pursue their dreams is definitely the motivation for me,…when you see them so happy on graduation day, with their whole life ahead of them, it's always so exciting.”

Solution focus

Another approach utilized by our participants to cope in the face of challenges to their leadership focused on finding solutions to problems. As Kamele described, she addressed such challenges by developing new opportunities for engagement and dialogue.

So there was a lot of trying to see if they can get me to change and do things that they wanted me to do, but instead of coming to me directly, they would go to him and present as if it was a union issue. And I had to push back and show how this is a union issue and then I'll address it. If not, then this is how it's going to stand. And then I created an advisory committee.

As outlined below, when Marisa reflected back on the stress she faced in her role as a school leader, she described a desire to leave her position, but then comes back to the work she does being a source of support and means to cope with those challenges. “I thought about leaving this year, strongly, for the first time ever. I interviewed to leave. As I was interviewing, I thought, ‘No, you can't just walk away. You've got to at least create, recreate, a strong neighborhood school'.”

Less Affirming (i.e., “Maladaptive”) Strategies

Participants also relied on strategies which enabled them to disconnect from or avoid gendered racism via denial or avoidance, boundary setting, and in a few cases, exiting. While in the initial framing the use of the term “maladaptive” to describe these strategies suggests they are somehow ineffective, we suggest that, for these women, a conscious choice to rely on one strategy over another depended on the situation, their role, and/or how often they experienced gendered racism in their current position. Moreover, we argue these strategies can be deemed effective in that they empowered these women and enabled them to persist. However, these previously oft-named “maladaptive” strategies also inflicted a larger toll on participants' health and well-being and thus our use of the term “less affirming” to describe them.

Avoidance and Denial

The most prominent of the less affirming strategies participants relied on, was the avoidance of facing or addressing acts of gendered racism they encountered as leaders. And yet, despite this approach, these participants were no less aware of these biases or their impact than those who relied on other strategies. As Janelle reflected in her decision to “ignore” the gendered racism she faced, “I also don't want to be the one to always bring in race, but it's still such a big piece of the puzzle. That's why we can't talk about it, I don't know. We're very passionate about it, but I don't know.” Sheila too spoke of the frequency of gendered racism, “Oh, clearly. It's laughable and, because we'd all be crying all the time if we actually thought about it that much,” and her choice to avoid dwelling on such experiences, “I don't think about that. It affects me and I do think about that, but I also know that, in order for me to help children, I got to look beyond certain things and yeah, there are certain structures in place and my goal is to break through them.” Both women acknowledged the discrimination they faced and their efforts to not let gendered racism occupy their minds or sway them from their important work as leaders.

Marlene, who utilized this strategy more frequently than other participants, was hesitant to name race as a reason she was passed over for a principalship earlier in her career. However, when the interviewer prompted further, she added, “You know, everybody else has their things, but in terms of me being able to move away from, a negative perspective…You know… ‘it's always racism.' It's not healthy for me [to question the potential racism], so that's why I have to opt out of that.” She continued, “Because it's not going to do anybody any good to say, ‘Oh, you know, you just don't like me because I'm a Black woman.' Or, you know, you know, not gonna help anybody. Not gonna help me, not gonna help that person.” For Marlene, reflecting or addressing gendered racism felt like too much to tackle, particularly given the frequency and regularity of these experiences. Her decision to avoid confronting the offender occurred as an effort to remain positive but also out of concern for how others might perceive confrontation.

Nicole said she avoided addressing gendered racism in her work in the Northeast because she felt it was relatively less than what she experienced growing up. “You know what? Because I was raised in the South, I come with a whole different outlook on stupidity and racism. Once your grandmother gets hit in the head with a gun by a police officer during the Civil Rights era, you kind of have a whole thicker skin because for me, it's a shame that you have not progressed as far as you have.”

While avoidance “worked” for several participants in so much that it helped them cope, it is important to recognize that avoiding or denying gendered racism did not protect them from the emotional toll it inflicted. As Kamele explained,

I was talking about something that happened months ago and then I realized that you know what, I had never really unpacked it. I put it in the back and…I'm not saying that it wasn't going to bother me, but I wasn't going to you know, give the time or space to think about it. But then months later it came up again, so it must be there and it must be affecting me in some way. But I just don't have the time or the space to unpack it.

Kamele's comments suggest that while avoidance may “work” in the short term to keep her grounded and in the work, its farther reaching effects may cause more harm than good, and exacts a high toll (i.e., emotional, physical, psychological).

Buffering and Boundaries

Participants used buffering and drew boundaries around themselves to make space between themselves and the personal impact of discrimination when they felt it could no longer be ignored or tolerated. The boundary line for Sheila was racism aimed at her children, “We just have way too much work to do to be focused on it, but I guess I started thinking about it more and more as my own children are going through school and how they're impacted with different things.” For Marlene, a participant who frequently relied on avoidance or denial as a strategy, felt the need to address discriminatory statements if they were repeated or followed a “pattern.” She said, “People will make some not so good statements, but when there are patterns of mis-…patterns of that kind of behavior, then that's when it just has to be…It has to be addressed.” In this way, her line seemed to be related to frequency and saturation.

Buffering, while similar to boundary drawing, worked to create distance or cushion between oneself and gendered racism whether in the present or the future. For some participants, such as Rosa, who felt her current work environment was hostile and discriminatory, buffering meant building up the resources to prepare and protect herself from future assaults.

And I don't want it to take any more. Because I think I can move on to a different work environment, and even if the same things happen, I would have an armor the next time. I would never make myself so vulnerable, ever again, in a workspace…I am taking this as a learning experience. Because I will have my armor on from the very first day in any next space.

Similarly, Sheila reflected on her reliance on buffering via keeping a distance when she started her work as a leader, “I knew I was going to be by myself, I knew that I wouldn't have allies, and so I knew I just had to observe. I knew it worked, so I had to figure out how it worked, and then just started taking notes and got to know who the key players were and who I knew couldn't stay on the staff if I wanted to bring any change.”

Nicole too created buffers between herself and others by, as she explained it, putting potential issues regarding her identity and how she might be experienced on the table before others did so.

Right, so now I just take it off their shoulder. I just take the burden off their shoulders so usually if I get up in front and start talking to them, I say, "Okay, I'm going to tell you, I'm going to be direct, but it's not threatening. I'm going to always be six-foot and a half inch tall because I'm not shrinking. For the life of me, I'm always going to be indigenous to this country and West Africa, okay? None of those things are going to change. Let's just put that out in the air,” so I remove the proverbial elephant in the room so they [don't] get to say anything because….I say, “No, Remember, I told you I was going to be direct, yet not threatening. If you're intimidated, that's something you have to deal with because I'm just speaking my truth. If you're intimidated by that, that's really an internal feeling that you have to deal with because no one can intimidate me unless I allow it. Don't allow it. You're intimidated by what I'm saying, and you don't know enough about the subject. Go learn about the subject, then you won't feel intimidated.”

In each of these experiences, the participants found a way to protect or distance themselves from the nearly constant assault of gendered racism, these boundaries or buffers enabled the women to persist if even for a time, before the next attack. Notably, these buffers or boundaries need to be redrawn as different experiences of gendered racism may require different ways to buffer from those experiences.

Leaving

It is critical to note that by the time of writing this paper, three participants left their positions and two left education altogether. While a tremendous loss for their students, schools, and districts, we choose to frame this strategy as less affirming but demonstrative of resilience. For the women who made the choice to leave, they recognized the constant barrage of gendered racism in their positions as leaders, the toll these experiences had on them, drew a line, and decided enough was enough. We recognize too, however, that for other participants, this strategy was not an option. Despite facing constant discrimination at work, these women served as the primary providers for their families, and or had extended family relying on them, thus leaving a secure job was not an option. Additionally, for others, leaving a position for which they have dedicated so much time, energy, and emotional support, did not feel to be a viable choice.

Costs to Coping

In these workspaces with these behaviors toward you, that are diminishments, that are microaggressions, that is the selective incivility. All of these things that exist, right? From a social perspective. This kind of social science. These constructs. They're real. But who am I supposed to be in the face of that, is the question? Am I supposed to be pumping my fist? Am I supposed to be strong but silent? Am I supposed to be resilient? Am I supposed to be like, “I can take it,” and then come out on the other side stronger? “You can't break me.” I've been, not broken, but bent. (Rosa)

Rosa eloquently articulates the challenges of gendered racism and the impact on our participants despite their coping strategies. Indeed, though these strategies helped the women to survive and for many, to thrive, in their work, not surprisingly, these coping responses came with costs. These women bore these costs in their personal lives, their physical and emotional health, and for some, their leadership positions themselves. In this section, we explore some of the costs borne by our participants. We have named these as tolls our participants carried as a result of being Black women in school leadership. Tolls included internalizing gendered racism as a burden they had to hold, doubting their leadership skills and competence, anger for having to operate in a gendered racist context, and resignation. For some, the costs associated were very close to the surface, as Michele recognized her exhaustion and the physical price she pays as a result of the discrimination she faces. “I definitely get weary in it, definitely say, sometimes I don't want to do it anymore. I feel like it's taken a toll on me physically.” She goes on to discuss the internal battle she wages to maintain her emotional health,

I have to find a way to find that light and not sway over so far into the darkness that I just feel, because then I feel that my power is gone. I give my power away, I give my hope away and then I'm really a victim because I'm like I can't, I would have, I could have, I should have…I don't want to live over there, so it's a constant battle to not go that far over there.

This struggle was evident for Rosa too, as she grappled with the burden of staying “above the fray” and not giving over her real and justifiable anger. She notes, evoking Michelle Obama, “But I don't feel like going high, while people go low anymore. I feel angry.”

Self-Doubt

Experiences of gendered racism exacted a price on participants as they often internalized these experiences; questioning if the negative critiques and messages they received resulted from individual shortcomings or failures in their work as leaders. As Kamele explained, while she understood at an intellectual level that much of what she faced was discriminatory, it did not change her feeling that she should be able to succeed in spite of it—that it shouldn't matter. “I could just say that it's [the negative feedback she receives) because I'm a woman, I think it would be harder because then I can say, ‘Well, I don't want to be that woman,' but for me, it was so many things. It was race, which no one ever talks about. So, I was even afraid to even think it.”

Rosa too struggled to unpack the challenges and insidious nature of gendered racism she faced in her role,

I need some kind of way to make sense, because it keeps coming back to the psychological impact, that's what I want you to get at, at some point. That there's a psychological impact on this constant second guessing what's going on there, what is it? Is it race, is it gender, is it age, is it where I am?

Marlene also shared this self-doubt regarding the source of the negative experiences she faced. “There are those patterns or behavior where I'm left to wonder like, ‘What is this really a-, you know, what is this really about? Is this about…me as a Black woman or is it something, something else?”' As Janelle described, she sought out professional development support in to mitigate the self-doubt she experienced as her leadership was continually challenged. “That's why I asked for a coach, because I'm starting to question myself.”

Michele reflected on the cost of persevering when others are constantly questioning your capabilities as a leader,

It is exhausting, right? It keeps me in this space of questioning myself, my work right. It keeps me in the space of confidence wise, “Well, maybe I'm really not as smart as I think I am. Maybe I've just over-estimated who I am and what I can accomplish.” And it is really heavy.

Recognition With Resignation

While there were clearly costs to trying to work around or through discrimination, so too were their costs when participants attempted to fight it. Participants reported feeling diminished and resigned as a result of such efforts. Resignation that despite their efforts to address others' biases, success was limited and often produced diminishing returns. Marlene named this phenomenon as she recognized the privilege held by those who do not experience gendered racism and her frustration at having to advocate on her own behalf.

Some people don't have to do any of that work.…For example, if there was a White man who was in charge of the building, [they] may never have to have those kinds of conversations or may have to have them,…or could engage them in a very different, perhaps less thoughtful or energy consuming way.

Shelby also noted her experiences with explicit gendered racism and how she disallowed herself to respond with anger, as the costs would be too high in terms of her ability to continue in her leadership role.

And so that's kind of, you have to take that in sometimes. And it's tough, it's tough, it's tough because you're dealing with people that are not necessarily very open to the fact that you're an African American woman. So, I've had some moments. I've had a student say to me ‘I don't want to talk to you, I want to talk to a White person'. So, it's you learn from it and you have to come in, I guess for me, and I say to kids all the time ‘if I held grudges, I wouldn't be able to do this job'.

Discussion

This study looked to share the experiences of Black women in school leadership in K-12 education and examine how they coped with gendered racism as school leaders. We also sought to shed light on the costs associated with this coping. Findings revealed that these Black female leaders' experience of coping with gendered racism were reflective of the strong Black woman (SBW) race-gender schema documented in previous research on the experiences of Black women (Woods-Giscombé, 2010). These women's experiences also reveal that the SBW race-gender schema cannot be understood on a binary of either positive (empowering) or negative (energy depleting), but their experiences in the SBW schema are more holistic (Watson and Hunter, 2016). Participants' experiences of coping with gendered racism in their roles as school leaders were at times less affirming (maladaptive) and exacted costs to their well-being. Yet they also used strategies that were affirming, drawing strength in their support of students, addressing challenges in their schools and communities and using faith to ground their purpose as leaders (Woods-Giscombé, 2010; Abrams et al., 2014).

Further, our findings support work by other scholars who are critical of the SBW schema as it negatively impacts the emotional well-being of Black women (Watson and Hunter, 2016). Our participants developed coping strategies to navigate gendered racism in their work, but they also described the costs paid to utilize these coping strategies. We did not specifically ask about health or health outcomes as a part of this research, though some participants did mention negative impacts on their physical well-being in addition to the negative impacts on their emotional well-being (Corbin et al., 2018).

We note throughout the paper that we troubled the term maladaptive coping and instead labeled this coping as a less-affirming coping strategy. Shorter-Gooden (2004) also problematize maladaptive coping, including avoidance coping, as this coping strategy is not always related to negative outcomes and for some, including our participants, can be beneficial as they must exist under oppressive circumstances that they are not able to change. However, West et al. (2010) noted increased depressive symptoms in those who used more avoidance coping. Also, work by Utsey et al. (2008) found that coping through avoidance, “attempting to forget the situation or minimize the negativity of the situation, or engaging in distracting activities,” (p. 312) did not reduce stress of those experiencing gendered racism. Our findings do not provide definitive support for avoidance as a beneficial coping strategy, but some participants who relied more on avoidance as a coping strategy persisted in their leadership positions, while other participants who did not use this strategy left their positions soon after our research concluded. Those who may have “paid” a higher toll with this form of coping used this strategy to persist in their leadership roles.

We are careful here to note that we do not endorse the SBW schema but want to call attention to the coping strategies utilized by our participants grounded in affirming and strengthening approaches, which we termed as more affirming strategies (Adams-Bass et al., 2014). Our participants had opportunities to exert power, influence change, and counter stereotypes in their roles as school leaders and these opportunities served to support our participants as they coped with gendered racism in their leadership roles (Watson and Hunter, 2016). However, these women had to cope in the workplace primarily on their own, without organization level supports in place acknowledging their experiences as different from predominantly White (male) school leaders. They found coping supports which are characterized as strength in SBW schema manifest “in the form of obligatory and volitional independence” (Abrams et al., 2014, p. 508). There were no formal organizational level supports, the burden of gendered racism was on our participants and they were expected to find the strength to hold this burden.

Implications

Here we offer a few (though not an exhaustive list of) implications for educational leaders, policy makers and educators. One is to create formal and informal spaces for Black women educational leaders to engage in conversations regarding their experiences as school leaders. These spaces should not be considered as places only to “vent” difficulties and challenges, but spaces to share insights, opportunities and strategies that can lead to meaningful policy changes and structural changes to improve the experiences of these leaders. These leaders must be heard by those in positions of power (i.e., still most often White men) and they must receive support for their decisions to address the challenges and embrace the opportunities they experience as school leaders. In addition, gendered racism must be named and discussed in educational leadership programs and in professional development programs (Weiner et al., 2019). These discussions are not “only” for Black women, but for all emerging professionals. The burden of addressing gendered racism must shift from those who experience it to those who witness it and by their silence allow it to continue and negatively harm their colleagues.

Further, we must shift the burden of coping with gendered racism from Black women in school leadership to a critique of how Whiteness is privileged in school leadership and how this privilege must be disrupted in all organizational practices (training, education, access, support, advancement). One, but clearly not the only, way to begin to shift this burden is to construct antiracist, feminist, White allyship (Erskine and Bilimoria, 2019) of Black women in school leadership. White allyship is

a continuous, reflexive practice of proactively interrogating Whiteness from an intersectionality framework, leveraging one's position of power and privilege, and courageously interrupting the status quo of predominantly White corporate leadership by engaging in prosocial behaviors that foster growth-in-connection and have both the intention and impact of creating mutuality, solidarity, and support of Afro-Diasporic women's career development and leadership advancement in organizational leadership (Erskine and Bilimoria, 2019, p. 2).

Allyship is a critical step to place the onus of gendered racism not on those who experience it but on those who benefit from the power and privilege of Whiteness. Specific steps, though not exclusive, that can be taken in White allyship include engaging in critical self-reflexivity and interrogating Whiteness, building trust and high-quality relationships, and providing solidarity and support (Erskine and Bilimoria, 2019). As Janelle reminds us,

Understand how uncomfortable this is for me. Not because I have an issue of talking about equity and injustice. But I don't need you to see…I don't need to be the barrier, because you think, “This is this Black woman, and this is her agenda.” So, we need to understand we're all in this continuum, and we need to approach it from, always a place of learning.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Abrams, J. A., Maxwell, M., Pope, M., and Belgrave, F. Z. (2014). Carrying the world with the grace of a lady and the grit of a warrior: deepening our understanding of the “strong black woman” schema. Psychol. Women Q. 38, 503–518. doi: 10.1177/0361684314541418

Adams-Bass, V. N., Stevenson, H. C., and Kotzin, D. S. (2014). Measuring the meaning of Black media stereotypes and their relationship to the racial identity, Black history knowledge, and racial socialization of African American youth. J. Black Stud. 45, 367–395. doi: 10.1177/0021934714530396

Bass, L. (2012). When care trumps justice: the operationalization of black feminist caring I educational leadership. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 25, 73–87. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2011.647721

Beal, F. M. (1969). Black Women's Manifesto; Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female. New York, NY: Third World Women's Alliance.

Benkert, R., and Peters, R. M. (2005). African American women's coping with health care prejudice. West. J. Nurs. Res. 27, 863–889. doi: 10.1177/0193945905278588

Boris-Schacter, S., and Langer, S. (2006). Balanced Leadership: How Effective Principals Manage Their Work. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Brown, F. (2005). African Americans and school leadership: an introduction. Educ. Adm. Q. 41, 585–590. doi: 10.1177/0013161X04274270

Burton, L., and Weiner, J. (2016). “They were really looking for a male leader for the building”: gender, identity and principal preparation, a comparative case study. Front. Psychol. 7:141. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00141

Christman, D., and McClellan, R. (2008). “Living on barbed wire”: resilient women administrators in educational leadership programs. Educ. Adm. Q. 44, 3–29. doi: 10.1177/0013161X07309744

Cognard-Black, A. J. (2004). Will they stay, or will they go? Sex-atypical work among token men who teach. Soc. Q. 45, 113–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2004.tb02400.x

Collins, P. H. (1991). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York, NY: Routledge.

Collins, P. H. (2015). Intersectionality's definitional dilemmas. Annu. Rev. Soc. 41, 1–20. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142

Corbin, N. A., Smith, W. A., and Garcia, J. R. (2018). Trapped between justified anger and being the strong black woman: black college women coping with racial battle fatigue at historically and predominantly White institutions. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 31, 626–643. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2018.1468045

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. U. Chi. Legal F. 1989:8.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

Daly, A., Jennings, J., Beckett, J. O., and Leashore, B. R. (1995). Effective coping strategies of African Americans. Soc. Work. 40, 240–248.

DeCuir-Gunby, J. T., Johnson, O. T., Womble Edwards, C., McCoy, W. N., and White, A. M. (2019). African American professionals in higher education: experiencing and coping with racial microaggressions. Race Ethn. Educ. 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2019.1579706

Dickson-Swift, V., James, E. L., Kippen, S., and Liamputtong, P. (2007). Doing sensitive research: what challenges do qualitative researchers face? Qual. Res. 7, 327–353. doi: 10.1177/1468794107078515

Dillard, C. B. (1995). Leading with her life: an African American feminist (re) interpretation of leadership for an urban high school principal. Edu. Adm. Q. 31, 539–563. doi: 10.1177/0013161X9503100403

Erskine, S. E., and Bilimoria, D. (2019). White allyship of Afro-diasporic women in the workplace: a transformative strategy for organizational change. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 26, 319–338. doi: 10.1177/1548051819848993

Feagin, J. R. (1991). The continuing significance of race: antiblack discrimination in public places. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1, 101–116. doi: 10.2307/2095676

Folkman, S., and Moskowitz, J. T. (2004). Coping: pitfalls and promise. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55, 745–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456

Forsyth, J., and Carter, R. T. (2012). The relationship between racial identity status attitudes, racism-related coping, and mental health among black Americans. Cult. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 18:128. doi: 10.1037/a0027660

Franklin, A. J., and Boyd-Franklin, N. (2000). Invisibility syndrome: a clinical model of the effects of racism on African-American males. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 70, 33–41. doi: 10.1037/h0087691

Greer, T. M. (2011). Coping strategies as moderators of the relation between individual race related stress and mental health symptoms for African American women. Psychol. Women Q. 35, 215–226. doi: 10.1177/0361684311399388

Hallinger, P., and Heck, R. H. (2009). “Distributed leadership in schools: does system policy make a difference?,” in Distributed Leadership, ed A. Harris (Dordrecht: Springer, 101–117.

Harrell, S. P. (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: implications for the well-being of people of color. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 70, 42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722

Harris, A., and Leonardo, Z. (2018). Intersectionality, race-gender subordination, and education. Rev. Res. Educ. 42, 1–27. doi: 10.3102/0091732X18759071

Holder, A., Jackson, M. A., and Ponterotto, J. G. (2015). Racial microaggression experiences and coping strategies of black women in corporate leadership. Qual. Psychol. 2:164. doi: 10.1037/qup0000024

Jean-Marie, G. (2013). The subtlety of age, gender, and race barriers: a case study of early career African American female principals. J. School Leadersh. 23:6156639. doi: 10.1177/105268461302300403

Jean-Marie, G., Normore, A. T. H., and Cumings Mansfield, K. (2016). “Negotiating race and gender in marginalized work settings,” in Racially and Ethnically Diverse Women Leading Education: A Worldview, ed T. N. Watson and A. H. Normore (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 35–53.

Lewis, J. A., Mendenhall, R., Harwood, S. A., and Browne Huntt, M. (2016). “Ain't I a woman?” perceived gendered racial microaggressions experienced by black women. Couns. Psychol. 44, 758–780. doi: 10.1177/0011000016641193

Lewis, J. A., Mendenhall, R., Harwood, S. A., and Huntt, M. B. (2013). Coping with genderedracial microaggressions among black women college students. J. Afr. Am. Stud. 17, 51–73. doi: 10.1007/s12111-012-9219-0

Lewis, J. A., Williams, M. G., Peppers, E. J., and Gadson, C. A. (2017). Applying intersectionality to explore the relations between gendered racism and health among black women. J. Couns. Psychol. 64:475. doi: 10.1037/cou0000231

Lincoln, Y. S., and Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Dir. Progr. Eval. 30, 73–84.

Maxwell, J. (1992). Understanding and validity in qualitative research. Harv. Educ. Rev. 62, 279–301. doi: 10.17763/haer.62.3.8323320856251826

McCray, C. R., Wright, J. V., and Beachum, F. D. (2007). Beyond brown: examining the perplexing plight of African American principals. J. Instr. Psychol. 34, 247–255.

Mellor, D. (2004). Responses to racism: a taxonomy of coping styles used by aboriginal Australians. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 74, 56–71. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.1.56

Mendez-Morse, S. (2003). “Chicana feminism and educational leadership,” in Reconsidering Feminist Research in Educational Leadership, eds M. D. Young and L. Skrla (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 161–178.

Moorosi, P., Fuller, K., and Reilly, E. (2018). Leadership and inter-sectionality: constructions of successful leadership among Black women school principals in three different contexts. Manag. Educ. 32, 152–159. doi: 10.1177/0892020618791006

Muñoz, A. J., Pankake, A., Ramalho, E. M., Mills, S., and Simonsson, M. (2014). A study of female central office administrators and their aspirations to the superintendency. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 42, 764–784. doi: 10.1177/1741143213510508

Myung, J., Loeb, S., and Horng, E. (2011). Tapping the principal pipeline: identifying talent for future school leadership in the absence of formal succession management programs. Educ. Adm. Q. 47, 695–727. doi: 10.1177/0013161X11406112

Neville, H. A., Heppner, P. P., and Wang, L. F. (1997). Relations among racial identity attitudes, perceived stressors, and coping styles in African American college students. J. Couns. Dev. 75, 303–311. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1997.tb02345.x

Newcomb, W. S., and Niemeyer, A. (2015). African American women principals: heeding the call to serve as conduits for transforming urban school communities. Int. J. Quali. Stud. Educ. 28, 786–799. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2015.1036948

O'Malley, M. P., and Capper, C. A. (2015). A measure of the quality of educational leadership programs for social justice: Integrating LGBTIQ identities into principal preparation. Educ. Administr. Q. 51, 290–330. doi: 10.1177/0013161X14532468

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Peters, A. (2010). Elements of successful mentoring of a female school leader. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 9, 108–129. doi: 10.1080/15700760903026755

Peters, A. L. (2012). Leading through the challenge of change: African-American women principals on small school reform. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 25, 23–38. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2011.647722

Reed, L., and Evans, A. E. (2008). ‘What you see is [not always] what you get!' Dispelling race and gender leadership assumptions. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 21, 487–499. doi: 10.1080/09518390802297797

Reed, L. C. (2012). The intersection of race and gender in school leadership for three black female principals. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 25, 39–58. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2011.647723

Rosette, A. S., de Leon, R. P., Koval, C. Z., and Harrison, D. A. (2019). Intersectionality: connecting experiences of gender with race at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 38, 1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2018.12.002

Rosette, A. S., and Livingston, R. W. (2012). Failure is not an option for black women: effects of organizational performance on leaders with single versus dual-subordinate identities. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48, 1162–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.05.002

Santamaría, L. J., and Jean-Marie, G. (2014). Cross-cultural dimensions of applied, critical, and transformational leadership: women principals advancing social justice and educational equity. Camb. J. Educ. 44, 333–360. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2014.904276

Scheurich, J. J., and Young, M. D. (1997). Coloring epistemologies: are our research epistemologies racially biased? Educ. Res. 26, 4–16. doi: 10.3102/0013189X026004004

Seidman, I. (2006). Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences. New York, NY: Teachers college press.

Settles, I. H. (2006). Use of an intersectional framework to understand Black women's racial and gender identities. Sex Roles 54, 589–601. doi: 10.1007/s11199-006-9029-8

Shakeshaft, C. (1989). Women in Educational Administration. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Corwin Press.

Shorter-Gooden, K. (2004). Multiple resistance strategies: how African American women cope with racism and sexism. J. Black Psychol. 30, 406–425. doi: 10.1177/0095798404266050

Thomas, A. J., Witherspoon, K. M., and Speight, S. L. (2008). Gendered racism, psychological distress, and coping styles of African American women. Cult. Diver. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 14:307. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.4.307

Tillman, L. C. (2004). (Un)intended consequences? The impact of the brown v. board of education decision on the employment status of black educators. Educ. Urban Soc. 36, 280–303. doi: 10.1177/0013124504264360

Utsey, S. O., Bolden, M. A., Williams, III O., Lee, A., and Lanier, Y Newsome, C. (2007). Spiritual well-being as a mediator of the relation between culture-specific coping and quality of life in a community sample of African Americans. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 38, 123–136. doi: 10.1177/0022022106297296

Utsey, S. O., Giesbrecht, N., Hook, J., and Stanard, P. M. (2008). Cultural, sociofamilial, and psychological resources that inhibit psychological distress in African Americans exposed to stressful life events and race-related stress. J. Couns. Psychol. 55:49. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.55.1.49

Utsey, S. O., Payne, Y. A., Jackson, E. S., and Jones, A. M. (2002). Race-related stress, quality of life indicators, and life satisfaction among elderly African Americans. Cult. Diver. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 8:224. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.8.3.224

Vassilliere, C. T., Holahan, C. J., and Holahan, C. K. (2016). Race, perceived discrimination, and emotion-focused coping. J. Community Psychol. 44, 524–530. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21776

Watson, N. N., and Hunter, C. D. (2016). “I had to be strong” tensions in the strong black woman schema. J. Black Psychol. 42, 424–452. doi: 10.1177/0095798415597093

Weiner, J., and Burton, L. (2016). The double bind for women: exploring the gendered nature of turnaround leadership. Harvard Educ. Rev. 86, 339–365. doi: 10.17763/1943-5045-86.3.339

Weiner, J. M., Cyr, D., and Burton, L. J. (2019). Microaggressions in administrator preparation programs: how black female participants experienced discussions of identity, discrimination, and leadership. J. Res. Lead. Educ.. doi: 10.1177/1942775119858655

West, L. M., Donovan, R. A., and Roemer, L. (2010). Coping with racism: what works and doesn't work for black women? J. Black Psychol. 36, 331–349. doi: 10.1177/0095798409353755

White, A. M., DeCuir-Gunby, J. T., and Kim, S. (2019). A mixed methods exploration of the relationships between the racial identity, science identity, science self-efficacy, and science achievement of African American students at HBCUs. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 57, 54–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.11.006

Witherspoon, N., and Taylor, D. L. (2010). Spiritual weapons: black female principals and religio spirituality. J. Educ. Adm. Hist. 42, 133–158. doi: 10.1080/00220621003701296

Wood, W., and Eagly, A. H. (2012). “Biosocial construction of sex differences and similarities inbehavior,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, eds J. M. Olson and M. P. Zanna (Burlington: Academic Press, 55–123.

Woods-Giscombé, C. L. (2010). Superwoman schema: African American women's views on stress, strength, and health. Qual. Health Res. 20, 668–683. doi: 10.1177/1049732310361892

Wrushen, B. R., and Sherman, W. H. (2008). Women secondary school principals: multiculturalvoices from the field. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 21, 457–469. doi: 10.1080/09518390802297771

Keywords: educational leadership, intersectionality, gendered RACISM, women, leadership

Citation: Burton LJ, Cyr D and Weiner JM (2020) “Unbroken, but Bent”: Gendered Racism in School Leadership. Front. Educ. 5:52. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00052

Received: 11 November 2019; Accepted: 17 April 2020;

Published: 12 May 2020.

Edited by:

Victoria Showunmi, University College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Corinne Brion, University of Dayton, United StatesMelanie Carol Brooks, Monash University, Australia

Copyright © 2020 Burton, Cyr and Weiner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura J. Burton, bGF1cmEuYnVydG9uQHVjb25uLmVkdQ==

Laura J. Burton

Laura J. Burton Daron Cyr

Daron Cyr Jennie Miles Weiner

Jennie Miles Weiner