- Department of Teacher Education, Faculty of Social and Educational Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

The study presented in the article focused on school-based development in lower secondary schools in Norway. School-based development represents a new practice not only for school leaders and teachers but also for teacher educators, who should assist schools in their development processes. The study was conducted within the framework of cultural historical activity theory (CHAT). The aim of the professional development project was twofold: to develop teaching practice in schools and also to evolve the teaching in the participating teacher education institutions. The problem formulation for the article is the following: How does teacher educators’ collaboration with schools contribute to learning in their own institutions? The purpose of the study was to find out how the teacher education institutions’ participation influenced the activity within the institutions and what factors could impede or support teacher educators’ actions and learning, and even expansive learning. Expansive learning means that a new collective practice or activity is developed in the institution. To answer the research question, a collective case study was conducted to understand the premises and promises for expansive learning in teacher education. The study found “Organizing of the work at the institutions,” “Teacher educators’ experiences and learning,” “Teacher educators as researchers,” and “Leadership and change” to be central categories that can describe teacher educators’ work and its premises and promises. The study concludes that leadership at the institutions is the main factor that can impede or enhance expansive learning and thus institutional development, and that an interplay between content, culture, and structure is necessary for expansive learning in teacher education.

Introduction

In a national project conducted over the period 2013–2017, the central Norwegian education authority wanted to improve the quality of teaching in lower secondary schools by focusing on school-based development. The Norwegian authorities provide a definition for school-based development:

School-based development means that the school, including school leaders and the entire staff, undergoes a workplace-development process. The aim is to develop the school’s collective knowledge, attitudes, and skills when it comes to learning, teaching, and collaboration.

(Directorate of Education, 2012, p. 5, my translation)

For 4 years, all the 19 teacher education institutions in Norway took part in supporting the schools as development partners for three semesters in each school, in 1114 schools altogether. The authorities said that school leaders should direct the development processes, with assistance from teacher educators, but that local education authorities were responsible for the local projects. The objective was to develop a teaching practice that was varied, practical, relevant, and challenging for students (Directorate of Education, 2012) leaving them with a sense of mastery and a motivation to learn (Ministry of Education, 2011).

School-based development represents a new practice not only for school leaders and teachers, but also for teacher educators, who should assist with the development processes in schools. The aim of the project was not just to develop teaching practice in schools, but the intention was also that the teaching in the participating teacher education institutions should be developed (Directorate of Education, 2012). The teacher educators taking part in the project could meet other teacher educators twice a year to share experiences and to plan their future activity in collaboration with the schools (Normann and Postholm, 2018). The article focuses on how the teacher educators’ actions, which supported the schools, were handled in their institutions and on the outcomes, both at the individual and organizational level. The research problem is formulated as the following question: How does teacher educators’ collaboration with schools contribute to expansive learning in their own institutions? Expansive learning is “to learn something that is not yet there” (Engeström and Sannino, 2010, p. 2) and thus, to creatively develop something collectively new in an organization. The purpose of the study was to understand how the teacher education institutions’ participation influenced the collective activity within the institutions and what factors can impede or support teacher educators’ actions and learning. The study was conducted within the framework of cultural historical activity theory (CHAT).

First, I will present CHAT and the related research connected to the study. Next, I will describe how the research was conducted to answer the research question, before I present the findings. The findings will be analyzed and discussed within the framework of CHAT and the related research. I will end the article with some concluding remarks.

Theoretical Framework and Related Research

Theoretical Framework

Expansive learning is as already mentioned defined as “to learn something that is not yet there” (Engeström and Sannino, 2010, p. 2). According to Virkkunen (2006), transformative agency can be defined as “breaking away from the given frame of action and taking the initiative to transform it” (p. 49). Engeström and Sannino (2016) stated that expansive learning requires and fosters transformative agency. According to Engeström (1987), “expansive learning activity is mastery of expansion from actions to a new activity” (p. 125). Actions are conducted by individuals through the division of labor to move practice toward an object for collective and societal activities (Engeström, 1987), for instance, actions conducted by teacher educators in their institutions.

CHAT is developed on the basis of Lev Vygotsky’s thoughts and ideas and has several features that correspond to Vygotsky’s fundamental thoughts. According to Vygotsky (1981), consciousness is not a product of society; it is produced in the interactions between individuals and society. Thus, external and internal activities have a developmental relationship. Vygotsky (1981) wrote: “It goes without saying that internalization transforms the process itself and changes its structure and function” (p. 163). The individual is active in both transforming and changing the structure of the processes, and the use of language has a central function in these processes (Vygotsky, 1978, 1981). In CHAT, the externalization process is also central (Leont’ev, 1981; Engeström, 1999). In human activity, internalization and externalization continuously operate at every level. Internalization is related to the reproduction of the culture in question, and externalization refers to the processes that create new artifacts or new ways to use them. Externalization thus enables development and creative processes (Engeström, 1999) and can be linked to expansive learning.

In CHAT, the overall aim is to develop practice toward a collective object, and thus, individual actions and development are connected to the division of labor when acting on a joint object. Engeström (1987) p. 174 has expanded on Vygotsky (1978) individual definition of the concept zone of proximal development. According to Vygotsky, learning is a process that starts at the social, external level before it is internalized. At the individual level, the person’s learning should be supported in his or her zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978). Engeström (1987) writes in his collective definition: “It is the distance between the present everyday actions of the individuals and the historically new form of the societal activity that can be collectively generated […]” (p. 174). Leont’ev (1981) pointed out that “the object is the true motive” (p. 59) for our actions. When people share a motive for acting on a collective object, the object will be “invested with meaning and motivating power” (Sannino et al., 2016, p. 602). In teacher education, teacher educators’ motivation should thus be built into the object to create “initiative and commitment” (Sannino et al., 2016 p. 81).

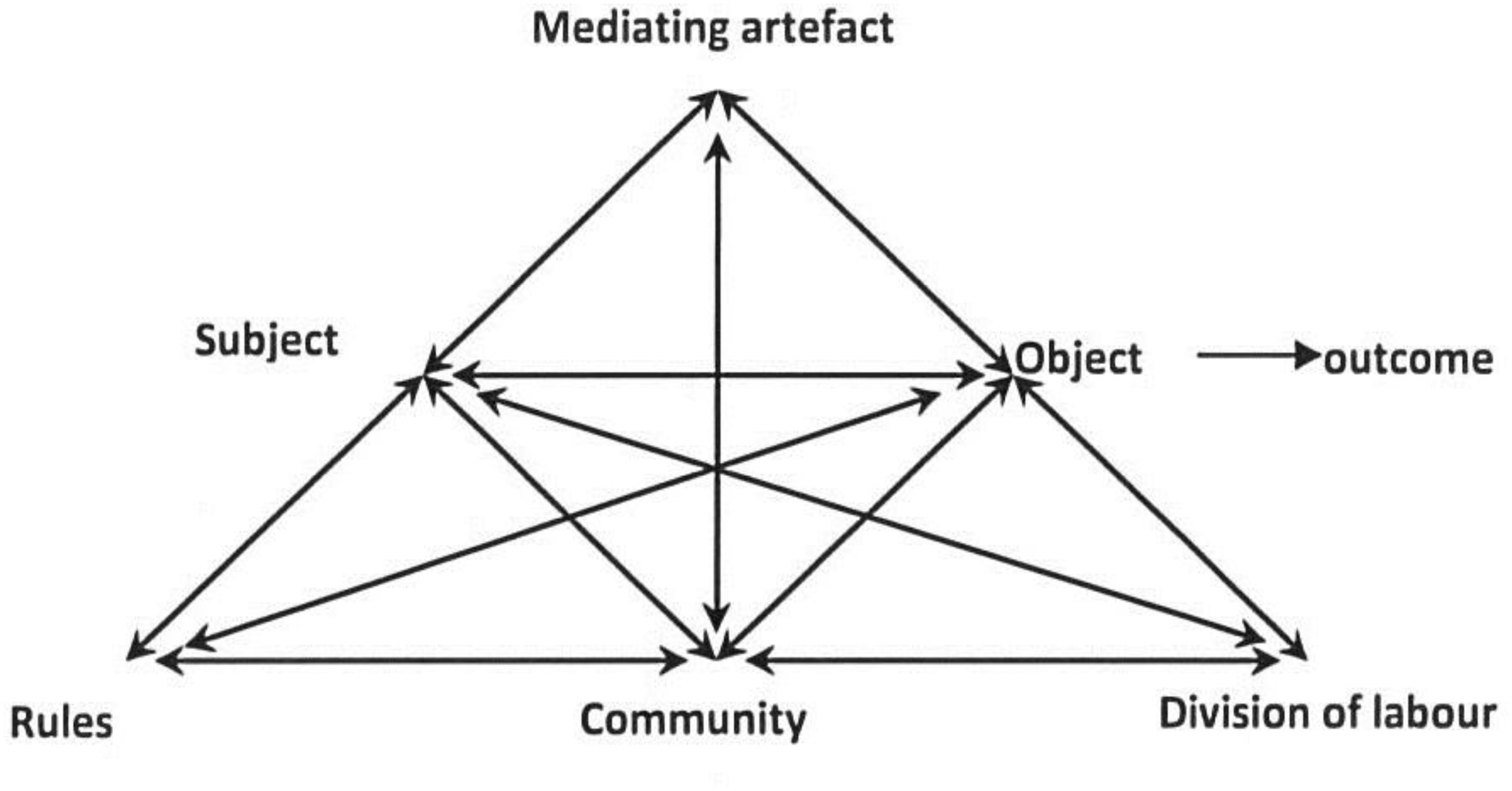

Engeström (1987) has developed CHAT in what he has named three generations. He refers to Vygotsky’s work as the first generation of CHAT, Leont’ev’s contribution as the second generation of CHAT, and his own contribution as the third generation of CHAT. The first generation of CHAT is represented by Vygotsky (1978) triangle, showing an intermediary step between the stimulus (S) and the response (R) through an auxiliary stimulus (X) (see p. 40). A limitation of this first generation of CHAT is that individuals are the unit of analysis. This individual perspective was expanded on by the second generation of CHAT developed by Leont’ev (1981). He introduced, in his example of a hunt scenario, the division of labor and thus described collective activity. Each person conducts goal-directed actions that together satisfy their needs, as in the example of hunting directed at the object of obtaining food. One person is chasing, another is preparing for the ambush, and another should fire the rifle. Engeström (1987, 2001) has visualized this second generation of CHAT in the activity system. The upper triangle in the activity system (see Figure 1 below) corresponds to Vygotsky’s fundamental triangle, but it is turned upside down, with the node mediating artifacts at the top.

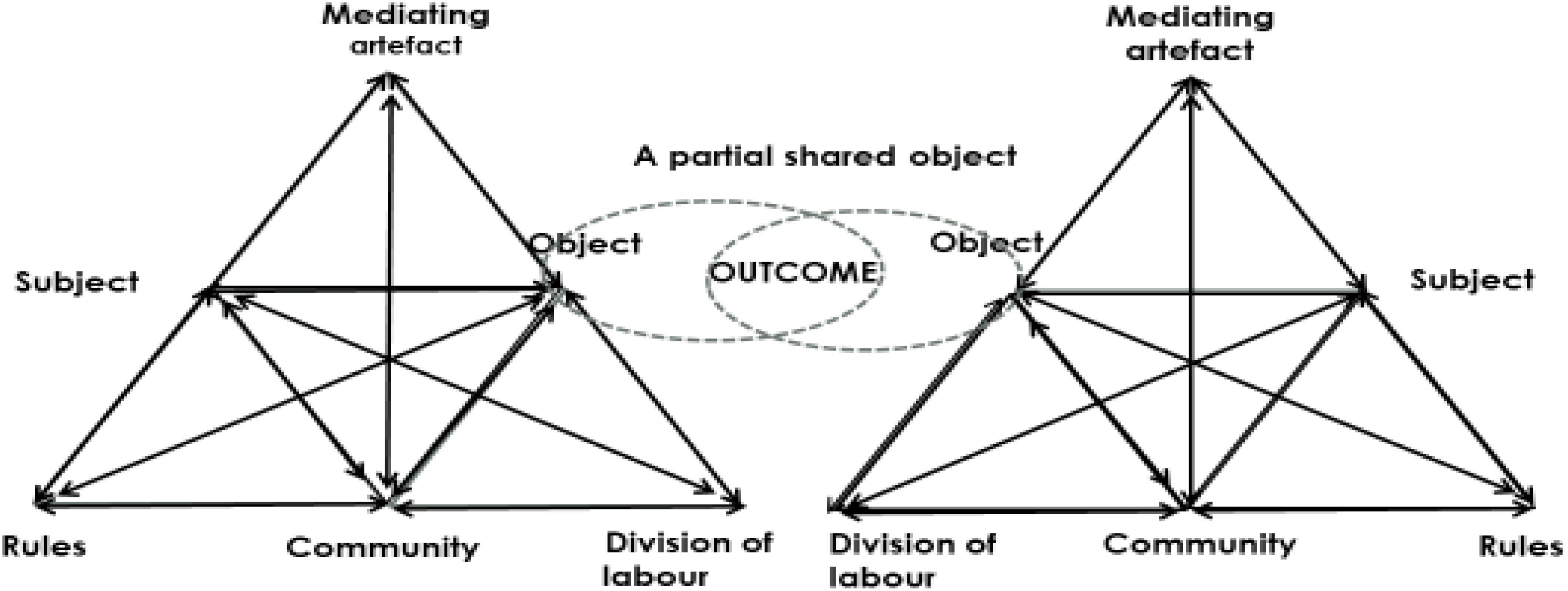

Engeström (1987, 2001) also developed the third generation of CHAT. The third generation focuses on collaboration between two or more activity systems that form networks of interacting systems. The activity system, which is the basic model of CHAT, is thus expanded to include a minimum of two systems in the graphical development of the third generation of CHAT. The subjects are in their networks acting on an object that is partially shared between the systems. At the same time, subjects, in each of their systems, also act on their own objects. The third generation of CHAT is visualized in the model below.

In CHAT, boundary crossing is an important concept. Engeström et al. (1995) stated that boundary crossing is characterized as “horizontal expertise where practitioners must move across boundaries to seek and give help, to find information and tools wherever they happen to be available” (p. 332). The concept of boundary crossing can thus be useful when focusing on the collaboration between teacher educators, leaders, and teachers in schools. Collaboration within a “shared meeting ground” (Engeström and Toiviainen, 2011 p. 35) can lead to the adoption of ideas from one another and, thus, to developmental transfer between different arenas (Engeström and Sannino, 2010), for instance, from school to teacher education and vice versa. Collaboration between systems can thus lead to learning and development within systems.

Related Research

Teacher Educators’ Learning

Lampert and Graziani (2009) state that schools collaborating with universities seem to be places where education might be connected to the improvement of teaching. However, according to Labaree (2006), there can be problems when trying to bring together two institutions, the school and the university, as they are systems that have different cultures, different reward structures, different calendars, and different goals. That various institutions have different objects is visualized in the third generation of CHAT (Engeström, 1987, 2001) and that people from the two different systems can act on a partially shared object at the same time. Loughrang (2014) describes teacher educators’ development as professional growth and states that teacher educators have more autonomy and control over their work than teachers have. However, Anthony et al. (2018) observe that professional growth needs to “embrace more than an incidental trajectory occasioned by learning on the job” (p. 7). Meijer et al. (2017) studied teacher educators’ transformative learning, and they found that the teacher educators’ learning and their development of a shared vision were enhanced by opportunities to learn. Transformative learning and deep learning is embraced in Engeström (2001) concept of expansive learning, and he writes that it means “qualitative shifts in the functioning of the activity system as participants react to growing of contradictions within it, which in turn may lead to a deliberate collective change effort” (p. 137).

In Norway, since 2017, teachers complete a master’s degree and are expected to conduct research on their own practices and learn from it (Ministry of Education, 2014; Postholm and Jacobsen, 2018). Teaching and research also described as key factors in teacher educators’ professional development (Cochran-Smith and Lytle, 2004; Loughrang, 2014; Lunenberg et al., 2014). This is, according to Lampert and Graziani (2009), a challenge in universities, and they suggest that teacher educators should take advantage of what is known about how teachers learn in schools, but according to Levin and Greenwood (2011) teacher education institutions have a long way to go in developing culture; culture defined by Wolcott (2008) as the different ways groups act and the convictions they connect to these actions. Ping et al. (2018) found in their review study that learning through collaborative activity was important for teacher educators to improve their practices. Windschitl and Stroupe (2017) state that teacher educators have the responsibility to learn and take up new roles that are different from the status quo. Parker et al. (2016) suggest that teacher educators can draw on models of teacher professional learning, such as engagement within communities of practice. Below, the research on teachers’ professional development is presented.

Teachers’ Professional Development

According to several researchers, school leaders play an important role in creating a positive learning environment in schools. School leaders can help teachers identify their own developmental needs, encourage experimentation, provide resources to support teachers’ learning, and support the implementation of new learning (Thoonen et al., 2011; Vanblaere and Devos, 2016). Research findings also show that it is crucial for teachers to contribute to the content of development processes if they are to gain ownership of the processes (Knowles et al., 2005) and emphasize the importance of taking the teachers’ needs into account (Ermeling and Yarbo, 2016; Olin and Ingerman, 2016; Tan and Caleon, 2016). Confidence is a word that dates back to research that focuses on the role of leadership in teachers’ learning processes in schools. This implies a responsibility that is given to the leaders when it comes to developing a trust relationship both between themselves and teachers and between teachers (Liu et al., 2016; Piyaman et al., 2017). One way of supporting teachers is for leaders to make sure that there is time, for example, observation and reflection in their schedules (King, 2016; King and Stevenson, 2017) but time alone does not lead to development. Research shows that there must be an interaction between structure and school culture for development to take place (Forte and Flores, 2014; Postholm, 2016). Elmore (2000) states that practice is unlikely to develop in a school if the school, as an organization, and its leaders do not focus on this development practice. This means that an organizational capacity must be created for the professional development of teachers (Feeney, 2016).

Based on a study that encompassed an entire school, the researchers conclude that a common goal is essential for developing the practice across a school (Sung et al., 2017). Research on teachers’ action research (McNiff, 2013) in which teachers develop research questions based on their own needs, shows that teachers experience gaining control of their own learning situations (Goodnough, 2016). Teachers also feel that they are emotionally rewarded when they collaborate (Chen, 2017) and that collaboration contributes to greater satisfaction in teaching (Postholm and Wæge, 2016; Soini et al., 2016). However, research shows that teachers can find themselves in “the land of nice” (City et al., 2010) supporting each other using cumulative talk, rather than exploratory talk that can lead to competition between ideas (Mercer, 2004).

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

To answer the research question: How does teacher educators’ collaboration with schools contribute to expansive learning in their own institutions?, I conducted a collective case study (Stake, 1995; Creswell, 2013). I gathered data by writing field notes when observing reflection dialogues between teacher educators at network seminars where teacher educators from the 19 the teacher education institutions in Norway were present. The country was divided into four regions, and thus teachers educators in the 19 teacher education institutions met in four groups, three with five institutions and one with four institutions. Two network seminars were arranged in each region each year, and thus the teacher educators from each region met each other eight times throughout the project lasting for 4 years (Normann and Postholm, 2018). Furthermore, reflection notes written by groups of teacher educators at the end of each seminar are included in the data material. Focus group interviews (Fontana and Frey, 2000; Kamberelis and Dimitriadis, 2011) were also conducted in each teacher educator institution throughout the project. These interviews were recorded. During the first 3 years in the project focus group interviews were conducted with five different institutions each year. At the end of the last year in the project, four institutions took part in focus group interviews. The participants in these interviews were teacher educators taking part in the project collaborating with schools. The number of participants in these interviews varied from three to ten, depending on the size of the institution and their opportunity to take part. The intention of the focus group interviews was to produce information about the situation at each institution at the time each focus group interview was conducted, and to get insight into what participation meant for development and learning in the project across institution. The observation- and the reflection notes could also trace learning and development in each institution over time.

The questions for the focus group interviews, focusing on what significance the teacher educators’ participation in this project had for the work in their own institutions, were the following:

• In what way has the project affected your own learning?

• In what way do you feel that the work has contributed to your own teaching in teacher education?

• What significance did the project have for the organization of disciplinary and interdisciplinary cooperation in your institution?

• How important has your participation in this project been for the development of your own research expertise?

• How would you describe the leaders’ commitment to the project at your own institution?

In addition to these questions, the participants were also asked about how the work was organized at their institutions. At the end of each gathering of teacher educators during the project, they were asked, as mentioned, to write reflection notes. In groups, formed of participants from each institution, they wrote about their experiences connected to their own learning and to the work in their own institutions. Furthermore, they were asked to write about something that had gone well when collaborating with schools and their thoughts on this, about something that had been problematic and their reflections related to this, and about anticipated upcoming challenges and opportunities regarding the project.

Data Analysis

The focus group interviews constitute the primary data material, and they were transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were analyzed using the open coding process, as described in the constant comparative method of analysis (Strauss and Corbin, 1990, 1998). The categories developed from this analysis were the following: “Organizing of the work at the institutions,” “Teacher educators’ experiences and learning,” “Teacher educators as researchers,” and “Leadership and change.” The developed categories from the analysis of the focus group interviews also gave direction to the analysis of the total data material that supplemented the content of each developed category. The categories structure the presentation of the findings that are narratively constructed (Riessman, 2008) within each category.

Ethics and Quality

The study was approved by the Norwegian national research ethics committee. Before data collection, the study’s participants signed a consent form, so the study was based on informed consent. Furthermore, the study kept all the participants anonymous (NESH, 2016) no one is therefore mentioned by name. A collective summary of the focus group interviews conducted was sent to the participating teacher institutions for member check (Lincoln and Guba, 1985) to ensure trustworthiness of the study.

The presented experiences are connected to a specific project, but the findings presented may have transferability and resonance beyond their context if readers of this article can use them to think creatively and imaginatively (Geertz, 1973) thereby using them as a thinking tool (Gudmundsdottir, 2001). This means that the findings could contribute to the development of teacher educators’ learning, also connected to other school-based development projects, and to the development of their own institutions as a learning organization.

Findings

Organizing the Work at the Institutions

A big puzzle for the institutions was organizing teacher educators into development groups during the project, both in the context of academic background and personal fitness. These development groups should collaborate with schools to develop the teaching practice toward the objective of the project, that was to develop a varied, practical, relevant, and challenging teaching practice to leave the students with a sense of mastery and a motivation to learn. In general, the teacher educators emphasized that members of the group should have prior experience from the schools, should speak “the right language” so that they were understood in schools, and should be personally suitable for this type of work.

Capacity problems at the institutions created challenges related to the composition of the development groups. In addition to teaching on campus, the teacher educators experienced during the project that parallel work with several national projects could be too much for the individual institutions. It was clear, at an early stage, that teacher educators had organized themselves somewhat differently, and that there was a lack of continuity in the development groups. This lack of continuity was experienced as a challenge throughout the project. The constant changes in teacher educators in the development groups became a challenge when it came to maintaining, transferring, and further developing the experiences of the teacher educators during the project. However, at one institution, the development group was stable, and the participants at this institution had also supported schools in pairs, with one teacher educator in pedagogy and the other in a specific subject.

Teacher Educators’ Experiences and Learning

The teacher educators’ understanding of what school-based competence development is had evolved, and the willingness to work in teams at the institutions had increased. The collaboration across institutions had also led to a curiosity around and a motivation to participate in the project. Working closely with colleagues at their own institutions had made the teacher educators feel useful, and it had been professionally enriching. That it was professionally enriching was also connected to the inexperienced being given the opportunity to work with experienced teacher educators. This was a strategy at one of the institutions. The emphasis on collective learning in multidisciplinary groups seemed to be one of the most important characteristics of why some groups of teacher educators had learned. However, there is little evidence that the content and learning that had taken place in the context of the work in the schools had spread to teacher educators not members of the development groups at the institutions, and individual learning in the institutions had been the most prominent type.

Teacher educators supported the schools in different ways. Some of them gave lectures, and others observed teaching, believing that these observations helped them to understand how they should meet the needs of the teachers in the whole school and how they should contribute to the collective practice at the school. One of the teacher educators said the following when interpreting the observations of teaching practices as the starting point when communicating with the all the teachers: “The teachers then had something to jointly talk about.”

Some of the teacher educators were excited about the opportunity that they had to bring experience from their work in schools into their teaching, as the following statement shows:

Just being there to stick my head inside all those schools, it does matter to me in terms of learning something more about schools. So, either consciously or unconsciously, I draw those things into the teaching somehow in my own institution, I think.

In this way, the project has echoed within their own institutions, but mainly learning on the individual level, and the teacher educators experienced a connection between what happened in the field of practice and the content of the education program. They also learned that they gained greater credibility in meeting the needs of their own students on campus.

Others, again, did not use their experience of investing in teaching as they were neither responsible for basic education nor had teaching within further education. They nevertheless saw the transfer value of the experience and thus, of the knowledge that they had acquired during the project, for other tasks at their own institution. Some of the teacher educators who were not directly involved in the education of new teachers were, however, working on master’s programs in school leadership, on the principal’s education, on the supervisor’s education, or in the further education sector. In some cases, master’s students were also given the opportunity to obtain data from the schools where their supervisors worked as teacher educators supporting the schools. This was a practice that depended on which teacher educators the students had. No institutional practice existed that allowed master’s students or undergraduate students who were to write their research and development (R&D) assignments to participate in school-based competence development in schools, but teacher educators want a plan for how students should be involved. There were also some teacher educators who were fully engaged in the project and therefore did not teach on campus.

During the project, many teacher educators experienced that they were able to develop collective knowledge, but there were structures that were lacking in the organization that contributed to the teams’ experience and knowledge of being part of the organization. It is clear that many institutions lacked an overview of the various tasks that were performed and how the experiences could be developed and utilized. Teacher educators, during the course of the project, also learned that they lacked competence in college guidance. They experienced that the teachers did not challenge each other, but for the most part supported each other when reflecting on each other’s teaching. The teacher educators also felt that they did not know enough about how to express themselves in dialogs with teachers to manage to support them to develop their practice. The teacher educators therefore expressed the desire to develop their own professional competences in this field.

Teacher Educators as Researchers

The teacher educators believed that research should be linked to development work in the schools, but several teacher educators stated that they lacked networks or a leader that could drive research projects. However, several teacher educators also formed their own research groups during the project and stated that they perceived the project as a “gift package for teacher education.” A teacher educator uttered: “The schools as a research field became easily accessible for us.”

The teacher educators experienced that the project was important both for research and in terms of having contact with the field of practice. Although there was a unified desire to conduct research in the context of the project, it turned out that it was not so easy for everyone and that such activities depended on the time each individual could allocate to research in his or her position. The activity in these research groups also decreased during the project. At the same time, teacher educators maintained that it was important to develop their knowledge about and a better understanding of how practices and development processes could be researched in R&D work. “We have to develop our methodological competence,” was an utterance that was reiterated.

Leadership and Change

Employees at 12 of the 19 institutions experienced the leaders as being absent or peripheral during the project. “When we work on external development projects, we also have to work internally to develop, also when it comes to research, but that requires us having the leadership with us,” a teacher educator uttered.

At several institutions, the staff found that there was good leadership support for meetings, with experience sharing between the teacher educators taking part in the project, but that there was little support for investment in the professional staff as a whole and in the education programs. They thought that the work they did needed to be communicated further and even to teacher educators who have not cooperated so much with schools in the past. The teacher educators communicated the need for staff to share experiences of how they work at their own institutions. “What do we do to develop as mentors in schools?” one of them says.

The teacher educators concluded that the lack of leadership reduced the possibility of there being lasting effects of the project. The teacher educators wanted leaders that facilitates knowledge sharing in their institutions. They found that the competences that they acquire in collaboration with the schools are not used in the institutions in a systematic manner. However, a tangible evidence of lasting change is the establishment of a separate professional group of teacher educators working on the development in schools in one of the institutions. The leadership at the institution impelled the organization of this group, and they had a clear rule: it was the teacher educators working at the institution that should constitute the group, not teacher educators working part time and hired from outside their organization. The idea behind this decision was that the teacher education institution should learn, and therefore the teacher educators had to be permanently employed at the institution.

Discussion

The study presented in this article was framed by the following research question: How does teacher educators’ collaboration with schools contribute to learning in their own institutions? In the following text, I will discuss the findings within the framework of CHAT and the related research.

First and foremost, it is the teacher educators who have actively participated in the project that have learned. However, due to a lack of collaboration they work differently with the schools, which indicates that they have not developed a common understanding of how to meet the needs of the schools at work. Experience sharing and reflection helps individuals to put into words what they do and thus become aware of their own actions or practices (Vygotsky, 1978, 1981). According to Ping et al. (2018), collaborating activity is important for teacher educators to improve their teaching. It is when individuals as teacher educators become aware of their own practice that they can also develop it on the basis of sharing and reflection with others (Postholm, 2008). There were not formal arenas in place for the sharing of experience and knowledge development for all teacher educators who worked on the project, so time for collaboration was not scheduled at all institutions, as suggested by King (2016) and King and Stevenson (2017). According to Anthony et al. (2018), professional growth needs to embrace more than occasional learning on the job. Despite the lack of formal arenas for knowledge sharing, some teacher educators, nevertheless, felt that they experienced profitable collaboration, both internally and across subjects, at their institutions in connection with their work in the schools. The project may therefore, in some cases, have contributed to a more integrated teacher education, which Nokut (2006) has also pointed out as an aim to act on for teacher education institutions but this still applies especially to some of those who have had an active role in the project. It does not appear that there is a widespread sharing culture at the institutions that allows all the teacher educators to develop together.

Levin and Greenwood (2011) point out that teacher education institutions have a long way to go in developing culture. This study shows that individuals and groups of individuals at the institutions have learned. They have learned that collaboration in teams is useful and professionally enriching. They have, furthermore, learned about practices in schools and that observation of teachers teaching can be the starting point for a dialog between all the teachers in a school, and that the collaboration between them and schools can enrich their teaching in their own institutions. The teacher educators have also learned that teaching including examples from practice can give them greater credibility in meeting the needs of their students. Additionally, the teacher educators have learned that they can develop their methodological competence, and that they can develop collective knowledge, but not a knowledge being part of the whole organization. They have, furthermore, learned about the leaders’ importance when it comes to development in teacher education.

Except in one teacher education institution learning can be connected to the individual or group level. In this teacher education institution, they developed a new form of collective societal activity (Engeström, 1987). They expanded to a new activity and thus broke away from the given (Virkkunen, 2006) and created something new that was not yet there (Engeström and Sannino, 2010) in the organization. They worked together and divided the work between them (the division of labor), conducting actions to reach goals. They were also supported by their leaders who created good conditions (operations), within which the individuals conducted goal-directed actions through their joint activity (Wertsch, 1981). They created something new in terms of expansive learning processes (Engeström and Sannino, 2010) and found themselves in an activity system where the context, made up by the factors of rules, community (also comprising the leaders), and the division of labor (Engeström, 1987, 2001) supported the object-oriented goal-directed actions. What the individual teacher educator has learned can be lasting, while organizational learning and lasting collective learning are dependent on good leaders, such as the leadership at this institution. This finding is supported by Elmore (2000) and Feeney (2016) who found that professional development needs to have an organizational focus, with leaders leading the way if practice in the whole organization is to develop.

The teacher educators also wanted to learn more about college guidance in order to support the teachers in their collaborations. They learned that the teachers did not communicate in such a way that they challenged each other when it came to each other’s teaching (City et al., 2010) and that they used cumulative talk (Mercer, 2004). Forte and Flores (2014) have found in their research that teachers lack collaborative skills. The fact that teacher educators wanted to gain more knowledge about college guidance can also be a sign that this theme does not have a prominent place in the education of teacher students either. In order for student teachers and teachers to become better at collaboration and guiding each other, demands are also made on teacher educators to develop their own competences and to add this theme to the agendas in their own institutions. The teacher educators also expressed that they should definitely have collaborated more, even when it comes to research.

Teacher educators described the project as a “gift package for teacher education” and linked this to the opportunity to research development processes that they themselves helped to support. In connection with the work during the project, several of the teacher educators wanted, as mentioned, to develop their research method expertise. When conducting research on developmental processes in the schools teachers in the teacher education system can be more systematic in their work when collaborating with leaders and teachers. According to Cochran-Smith and Lytle (2004), teacher educators must both research and teach. Teacher educators’ participation in research is described as a key factor in their professional development (Loughrang, 2014; Lunenberg et al., 2014). The material collected and analyzed from the school can further form the basis for teacher educators’ teaching in their own institutions. The fact that teacher educators have research expertise can therefore be of importance to both the schools and the students in their own institutions. Teacher educators will also benefit from research expertise when guiding master’s students.

Several studies focusing on the meeting of external resources, such as teacher educators, and teachers in the schools emphasize the importance of taking teachers’ needs into account (McNiff, 2013; Ermeling and Yarbo, 2016; Goodnough, 2016; Olin and Ingerman, 2016; Tan and Caleon, 2016; Sung et al., 2017). According to Leont’ev (1981), the overall goal or object of an activity is “the true motive” (p. 59). Teachers may find the work motivating if it is based on challenges or opportunities that they see in their own practice. It will then be “invested with meaning and power” (Sannino et al., 2016 p. 602). In their collaborations, teacher educators and teachers and leaders can develop a shared object, as shown in the third generation of activity theory (Engeström, 1987, 2001). But, was the shared object for the collaboration, focusing on developing teaching practice to be varied, practical, relevant, and challenging for students leaving them with a sense of mastery and a motivation to learn, also the object for the teacher educators in their own activity system? Should their effort be directed only to support development in schools when the aim of the project also was to develop practice in teacher education?

The constructivist view represented by the co-construction (Elden and Levin, 1993) of knowledge can occur, for example, by joint observation and reflection related to teaching. Co-construction involves learning for all parties, both for teacher educators and for leaders and teachers in the schools. A one-way lecture planned and given by teacher educators, as some teacher educators in this project did, does not necessarily facilitate this. However, collaboration framed by dialogs between teacher educators and practitioners can lay the foundation for development transfer (Engeström and Sannino, 2010), from school to teacher education and vice versa. Some teacher educators in the project observed the teachers’ teaching and used this observation as a starting point for dialogs. Teacher educators and teachers and leaders can cross each other’s boundaries (Engeström et al., 1995) and learn from each other, but according to Labaree (2006), this can create problems when bringing together different activity systems.

Learning for all parties also means that teacher educators need to develop an object or an overall goal that is known for each of them if they are to be able to move their practices toward the object of their activities in their own systems. However, a collective object requires that teacher educators construct the object together, and also collaborate to be able to move their practices toward it. According to Meijer et al. (2017), teacher educators’ learning and their development of a shared vision, or a shared object, can be enhanced by opportunities to learn. However, the study shows that collaboration between teacher educators has a potential in their institutions. If teachers educators conduct research with a joint research focus this joint focus can help teacher educators to be more coordinated in their work, but, at the same time they should remember that it is the practitioners’ needs that should be the starting point for development and research when collaborating with schools.

Research groups are emphasized as being important for education at teacher education institutions in order to succeed in providing research-based education (Ministry of Education, 2009, 2014). In order to be systematic in their development work in schools, teacher educators need data material to analyze as a starting point for further development in collaboration with practitioners. Collaboration with practitioners means, as already described, that it is also their development needs that should be the starting point for the work. However, research shows that teacher educators have a way to go when it comes to working with practitioners to promote school development and to conduct research in connection with development. A review study of all the articles published in the R&D in practice journal in the period 2007–2017, a total of 92 articles, shows that research was mainly initiated by researchers and their areas of interest (Nilssen and Postholm, 2017). If the teaching is to be research-based, it requires that teacher educators conduct research, but this, according to Lampert and Graziani (2009) is a challenge in teacher education. The findings in this study also show that teacher educators seem to have a way to go when it comes to linking development and research into a fruitful interaction that will have an impact on both developmental processes and on what research-based knowledge can be published and included in the teacher education curriculum.

The teacher educators feel that they need the support of the leaders of their own institutions if they are to succeed in their development work in the schools and, at the same time, conduct research. The school leaders’ role is highly documented in terms of development work in schools. Research have found that leaders are paying attention to teachers’ developmental needs, they encourage experimentation, they provide resources to support teachers’ learning, they support implementation of new learning and they develop trust between leaders and teachers and between teacher (Thoonen et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2016; Vanblaere and Devos, 2016; Piyaman et al., 2017). Research shows, furthermore, that teachers feel emotionally rewarded when collaborating (Chen, 2017) and that collaboration contributes to greater job satisfaction in their teaching work (Postholm and Wæge, 2016; Soini et al., 2016). The teacher educators’ work in the schools has helped some teacher educators to feel safer in their teaching on campus through allowing them to use practical examples that enrich the theory, but the teacher educators have the potential to develop their own competences related to research in development processes (R&D work) (Postholm, 2016). If teacher educators manage to emphasize the R in R&D work, working in schools could also help them make the teaching at their own institutions more research-based. This requires a leadership with an overview of competence and capacity so that those who carry out R&D work in schools also have the opportunity to bring this work to their teaching. The leaders should also organize the work in a way that ensures continuity when it comes to teacher educators participating to enhance the maintenance, transfer, and further development of the experiences.

The teacher educators also want a plan for how students should be involved in R&D work in schools. Student participation in research activities at various levels is emphasized in White Paper No. 16 (2016–2017), Culture for quality in higher education (Ministry of Education, 2017b) in terms of raising the quality of teacher education. The areas affected above are all discussed in Teacher Education 2025. National strategy for quality and collaboration in teacher education. In this strategy, it is pointed out that practice relevance has been a challenge in teacher education, that teacher education institutions need high R&D competence, and that students must be involved in research that should be linked to the field of practice (Ministry of Education, 2017a, p. 11).

Some teacher educators have involved both undergraduate and master’s students in their work in the schools, in connection with the students writing their R&D assignments and master’s theses. This is also a practice that appears to be dependent on the individual teacher educators as there are no institutional practices in place for this. The study shows that the opportunity to involve students in work in schools is not well utilized and formalized in the teacher education institutions. Those who have taken advantage of this opportunity may have an advantage over other teacher educators when it comes to involving students in their own R&D work. They will thus be better equipped to engage students when writing their master’s theses, which should be based on issues related to school practice. From 2017, all student teachers in Norway will take a master’s degree (BR40; Postholm and Jacobsen, 2018) and one intention of the master’s thesis is that the student teachers should gain greater insight into R&D work that can strengthen knowledge-based professional practice. They can thus research his or her own practice in order to continuously develop this. This means that they also need teacher educators who can provide insights into R&D work. However, teacher educators feel that they need to develop their methodological competence when conducting R&D work, which also involves supporting and challenging teachers in terms of reflections on their completed teaching.

Conclusion

The findings show that the participating teacher educators have learned, but several factors need to come into play in establishing premises for expansive learning (Engeström and Sannino, 2010) in the institutions. The leadership at the institutions is found to be a central factor that can impede or enhance expansive learning and thus institutional development. Teacher educators need to have content competences when supporting schools in school-based development. Additionally, they also need to collaborate to develop their competences together and to be coordinated in their work when collaborating with schools. Wolcott (2008) defines culture as the different ways groups act and the convictions they connect to these actions. This means that the teacher educators together need to find out what their convictions are and develop a joint understanding of the work and how it should be conducted. This means that that there needs to be a structure for teacher educators’ collaboration in their own institutions. There also needs to be a structure for how their competences should be transferred to both their colleagues and student teachers. If an interplay is created between content, culture, and structure, there should be promises for expansive learning in teacher education. To make this happen, teacher educators have a responsibility to develop (Windschitl and Stroupe, 2017) but leaders have the main responsibility for making expansive learning happen in their institutions. For teacher educators to be able to learn collectively in their own organizations, the study shows that expansive learning processes need to take place in teacher education, thus forming a new activity.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by NSD. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MP conducted the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Anthony, G., Averill, R., and Drake, M. (2018). Occasioning teacher-educators’ learning through practice-based education. Math. Teach. Educ. Dev. 20, 4–19.

Chen, X. (2017). Theorizing Chinese lesson study from a cultural perspective. Int. J. Lesson Learn. Stud. 6, 306–320.

City, E. A., Elmore, R. F., Fiarman, R. F., and Tietel, L. (2010). Instructional Rounds in Education: A Network Approach to Improving Teaching and Learning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Cochran-Smith, M., and Lytle, S. L. (2004). “Practitioner inquiry, knowledge, and university culture,” in International Handbook of Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices, Vol. 1, eds J. J. Loughrang, M. L. Hamilton, V. K. Laboskey, and T. Russell (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic), 601–649. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6545-3_16

Creswell, H. (2013). Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd Edn. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Inc.

Directorate of Education (2012). Strategi for Ungdomstrinnet- Motivasjon og Mestring for Bedre Læring. Felles Satsing på Klasseledelse, Regning, Lesing og Skriving. [Strategy for the Lower Secondary School – Motivation and Mastery for a Better Learning. Joint Effort on Classroom Management, Numeracy, Reading and Writing]. Oslo: Ministry of Education.

Elden, M., and Levin, M. (1993). “Cogenerative learning. Bringing participation into action research,” in Participatory Action Research, ed. W. F. Whyte (Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications), 127–142.

Engeström, Y. (1999). “Activity theory and individual and social transformation,” in Perspectives on Activity Theory, eds Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, and R. Punamaki (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), 19–38. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511812774.003

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive Learning at Work. Toward an Activity-Theoretical Reconceptualization. London: Institute of Education, University of London.

Engeström, Y., Engeström, R., and Kärkkäinen, M. (1995). Polycontextuality and boundary crossing in expert cognition. Learning and problem solving in complex work activities. Learn. Instruct. 5, 319–335. doi: 10.1016/0959-4752(95)00021-6

Engeström, Y., and Sannino, A. (2010). Studies of expansive learning: foundations, findings and future challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 5, 1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002

Engeström, Y., and Sannino, A. (2016). Expansive learning on the move: insights from ongoing research. J. Study Educ. Dev. 39, 401–435. doi: 10.1080/02103702.2016.1189119

Engeström, Y., and Toiviainen, H. (2011). “Co-configurational design of learning instrumentalities: an activity-theoretical perspective,” in Learning Across Sites: New Tools, Infrastructures and Practices, eds S. R. Ludvigsen, R. Säljö, I. Rasmussen, and A. Lund (Abington: Routledge), 33–52.

Ermeling, B. A., and Yarbo, J. (2016). Expanding instructional horizons: a case study of teacher team-outside expert partnership. Teach. Coll. Rec. 118, 1–48.

Feeney, E. J. (2016). How an orientation to learning influences the expansive-restrictive nature of teacher learning and change. Teach. Dev. 20, 458–481. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2016.1161659

Fontana, A., and Frey, J. H. (2000). “From structured questions to negotiated text,” in Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd Edn, eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc), 645–672.

Forte, A. M., and Flores, M. A. (2014). Teacher collaboration and professional development in the workplace: a study of Portuguese teachers. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 37, 91–105. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2013.763791

Goodnough, K. (2016). Professional learning of K-6 teachers in science through collaborative action research: an activity theory analyses. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 27, 747–767. doi: 10.1007/s10972-016-9485-0

Gudmundsdottir, S. (2001). “Narrative research in school practice,” in Fourth Handbook for Research on Teaching, ed. V. Richardson (New York: Macmillan), 226–240.

Kamberelis, G., and Dimitriadis, G. (2011). “Focus Groups. Contingent articulations of pedagogy, politics, and inquiry,” in Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4th Edn, eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc), 545–561.

King, F. (2016). Teacher professional development to support teacher professional learning: systemic factors from Irish case studies. Teach. Dev. 20, 574–594. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2016.1161661

King, F., and Stevenson, H. (2017). Generating change from below: what role for leadership from above? J. Educ. Admin. 55, 657–670. doi: 10.1108/jea-07-2016-0074

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., and Swanson, R. A. (2005). The Adult Learner, 6 Edn. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Lampert, M., and Graziani, F. (2009). Instructional activities as a tool for teachers ‘and teacher educators’ learning. Element. School J. 109, 492–509.

Leont’ev, A. N. (1981). “The problem of activity in psychology,” in The Concept of Activity in Soviet Psychology, ed. J. V. Wertsch (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, Inc), 37–71.

Levin, M., and Greenwood, D. (2011). “Revitalizing universities by reinventing the social sciences,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, Inc), 27–42.

Liu, S., Hallinger, P., and Feng, D. (2016). Learning-centered leadership and teacher learning in China: does trust matter? J. Educ. Admin. 54, 661–682. doi: 10.1108/jea-02-2016-0015

Loughrang, J. (2014). Professionally developing as a teacher educator. J. Teach. Educ. 65, 271–283. doi: 10.1177/0022487114533386

Lunenberg, M., Dengerink, J., and Korthagen, F. (2014). The Professional Teacher Educator: Professional Roles, Behavior and Development of Teacher Education. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Meijer, M.-J., Kuijpers, M., Boei, F., Vrieling, E., and Geijsel, F. (2017). Professional development of teacher-educators towards transformative learning. Prof. Dev. Educ. 43, 819–840. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2016.1254107

Mercer, N. (2004). Sociocultural discourse analysis: analysing classroom talk as a social mode of thinking. J. Appl. Linguist. 1, 137–168. doi: 10.1558/japl.v1i2.137

Ministry of Education (2009). White Paper no 11: Læreren - Rollen Og Utdanningen [The Teacher - The Role and Education] (2008-2009). Oslo: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education (2011). Meld. St.nr. 22 (2010-2011) Motivasjon – Mestring – Muligheter. [White Paper no. 22 (2010-2011) Motivation – Mastery – Possibilities]. Oslo: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education (2014). Lærerløftet. På lag for Kunnskapsskolen [Teacher Promotion. On Team for the Knowledge School]. Oslo: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education (2017a). Meld. St. nr. 16 (2016-2017). Kultur for Kvalitet i Høyere Utdanning. [White Paper No 16 (2016-2017) Culture for Quality in Higher Education]. Oslo: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education (2017b). Meld. St. nr. 21 (2016-2017). Lærerlyst – Tidlig Innsats og Kvalitet i Skolen. Oslo: Kunnskapsdepartementet. [White Paper No. 21 (2016-21017) Motivation to Learn - Early Efforts and Quality in School]. Oslo: Ministry of Education.

NESH (2016). Available at: https://www.etikkom.no/forskningsetiske-retningslinjer/Samfunnsvitenskap-jus-og-humaniora/ (accessed January 10, 2020).

Nilssen, V., and Postholm, M. B. (2017). Ti år med Tidsskriftet FoU i praksis: fokus, funn og forskning [Ten years with the Journal R&D in practice: focus, findings and research], Tidsskriftet FoU i praksis. J. R&D Pract. 11, 7–40.

Nokut (2006). Evaluering av Allmennlærerutdanningen i Norge 2006. Del 1: Hovedrapport. Rapport fra ekstern komité. Oslo: Nasjonalt organ for kvalitet i utdanningen. [Evaluation of General Teacher Education in Norway 2006. Part 1: Main Report. External Committee Report. Oslo: National body for quality education.

Normann, A., and Postholm, M. B. (2018). “UHs erfaringer, læring og utfordringer i arbeidet med satsingen [Universities and University colleges’ experiences, learning and challenges in the work during the project],” in Skole- og Utdanningssektoren i Utvikling [The School and the Educational Sector Developing], eds M. B. Postholm, A. Normann, T. Dahl, E. Dehlin, G. Engvik, and E. J. Irgens (Bergen: Fagbokforlaget), 51–73.

Olin, A., and Ingerman, Å (2016). Features of an emerging practice and professional development in a science teacher team collaboration with a researcher team. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 27, 607–624. doi: 10.1007/s10972-016-9477-0

Parker, M., Patton, K., and O’Sullivan, M. (2016). Signature pedagogies in support of teachers’ professional learning. Irish Educ. Stud. 35, 137–153. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2016.1141700

Ping, C., Schellings, G., and Beijaard, D. (2018). Teacher educators’ professional learning: a literature review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 75, 93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.06.003

Piyaman, P., Hallinger, P., and Viseshsiri, P. (2017). Addressing the achievement gap. Exploring principal leadership and teacher professional learning in urban and rural primary schools in Thailand. J. Educ. Admin. 55, 717–734. doi: 10.1108/jea-12-2016-0142

Postholm, M. B. (2008). Teachers developing practice: reflection as key activity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 24, 1717–1728. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2008.02.024

Postholm, M. B. (2016). Collaboration between Teacher Educators and Schools to enhance Development. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 39, 452–470. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2016.1225717

Postholm, M. B., and Jacobsen, D. I. (2018). Forskningsmetode for Masterstudenter i Lærerutdanning [Research Method for Master Students in Teacher Education]. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Postholm, M. B., and Wæge, K. (2016). Teachers’ learning in school based development. Educ. Res. 58, 24–38. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2015.1117350

Sannino, A., Enegström, Y., and Lemos, M. (2016). Formative interventions for expansive learning and transformative agency. J. Learn. Sci. 25, 599–633. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2016.1204547

Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., and Pyhältö, K. (2016). What if teachers learn in the classroom? Teacher development. Int. J. Teachers’ Prof. Dev. 20, 380–397. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2016.1149511

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Sung, Y.-K., Lee, Y., and Choi, I.-S. (2017). Contradiction, mediation, and school change: an analysis of the pedagogical practices in the Hyukshin School in South Korea. KJEP 13, 221–244.

Tan, Y. S. M., and Caleon, I. S. (2016). Problem finding in professional learning communities: a learning study approach. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 60, 127–146. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2014.996596

Thoonen, E. E., Sleegers, P. J., Oort, F. J., Peetsma, T. T., and Geijsel, F. P. (2011). How to improve teaching practices, the role of teacher motivation, organizational factors, and leadership practices. Educ. Admin. Q. 47, 496–536. doi: 10.1177/0013161x11400185

Vanblaere, B., and Devos, G. (2016). Relating school leadership to perceived professional learning community characteristics: a multilevel analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 57, 26–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.03.003

Virkkunen, L. S. (2006). Dilemmas in building shared transformative agency. Activités 3, 43–66. doi: 10.4000/activites.1850

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society. The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1981). “The genesis of higher mental functions,” in The Concept of Activity in Soviet Psychology, ed. J. V. Wertsch (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, Inc), 144–188.

Wertsch, J. V. (1981). “The concept of activity in soviet psychology. An Introduction,” in The Concept of Activity in Soviet Psychology, ed. J. V. Wertsch (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe), 3–36.

Keywords: cultural historical activity theory, teacher educators’ learning, school-based development, organizational learning, expansive learning, teachers’ professional development, leaders’ role

Citation: Postholm MB (2020) Premises and Promises for Expansive Learning in Teacher Education. Front. Educ. 5:41. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00041

Received: 28 January 2020; Accepted: 30 March 2020;

Published: 24 April 2020.

Edited by:

Ainat Guberman, David Yellin College of Education, IsraelReviewed by:

Maria Antonietta Impedovo, Aix-Marseille Université, FranceMary Frances Hill, The University of Auckland, New Zealand

Copyright © 2020 Postholm. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: May Britt Postholm, may.britt.postholm@ntnu.no

†ORCID: May Britt Postholm, orcid.org/0000-0002-9997-7318

May Britt Postholm

May Britt Postholm