- 1Department of Language and Culture, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway

- 2Department of Linguistics, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany

- 3Department of English Literature and Linguistics, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel

- 4Department of Language and Literature, NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

In this paper, we consider elicited production data (real and nonce words tasks) from five different studies on the acquisition of grammatical gender in Heritage Russian, comparing children growing up in Germany, Israel, Norway, Latvia, and the United Kingdom. The children grow up in diverse heritage language backgrounds, ranging from small groups (in Norway) to large communities (in Latvia). Furthermore, the children vary with respect to family background (one or two Russian-speaking parents) as well as the intensity of instruction in the heritage language through complementary schools. Russian has a three-gender system (masculine, feminine, and neuter) with gender cues varying in their transparency, predictability and frequency. The majority languages that these children speak differ widely with respect to the linguistic property studied: While English has no grammatical gender, Latvian and Hebrew both have two-gender systems (feminine and masculine), as well as the Oslo and Tromsø dialects of Norwegian (masculine and neuter), while German has a three-gender system, with a feminine-masculine-neuter distinction, like Russian. However, the transparency of gender assignment varies greatly, with Hebrew and Latvian having predictable gender based on the shape of the noun, like Russian, while gender assignment in Norwegian is generally arbitrary and German is semi-transparent, with gender assignment tendencies rather than rules. The focus in the paper is on language-internal and language-external factors that may be (non-)facilitative for the acquisition of gender in Russian, i.e., possible cross-linguistic influence from the majority language and the importance of background factors, such as family situation, age at start of kindergarten, size of the Russian-speaking community, current exposure to Heritage Russian instruction, and the main language of instruction. Our results show no significant differences across groups with respect to the majority language, but clear effects of background variables, with family type, age, and current exposure to Heritage Russian instruction as the most important ones.

Introduction

The paper investigates the effects of language-internal and language-external factors on the acquisition of grammatical gender in Heritage Russian (HR) acquired in the context of five different majority languages, German, Hebrew, Latvian, Norwegian, and English. The main focus of the paper is on heritage speaker (HS) sensitivity to morphophonological cues, i.e., noun endings in nominative singular. In this study, we adopt the traditional definition of grammatical gender as agreement between the noun and other targets (Hockett, 1958; Corbett, 1991).1 With regards to the acquisition of grammatical gender we adopt the cue-based approach, which argues that gender acquisition is cue-driven, such that children are highly sensitive to microvariation in the input, paying attention to fine distinctions in gender assignment in the form of morphophonological cues on the nouns (Westergaard, 2009; Rodina and Westergaard, 2012; Mitrofanova et al., 2018).

As our language-internal factor, we consider cross-linguistic influence (CLI) from the majority language on the acquisition of HR. The majority languages of the children in the current study differ in the following way: While English has no grammatical gender at all, Latvian and Hebrew both have two-gender systems (feminine and masculine), the relevant Norwegian dialects have masculine (or common) and neuter (cf. Rodina and Westergaard, 2015; Rodina and Westergaard, forthcoming)2 while German has a three-gender system with a feminine-masculine-neuter distinction, like Russian. The comparison of large datasets obtained from bilingual children with different majority languages is expected to shed light on the possible influence of structural properties of the majority language on the acquisition/maintenance of the heritage language (HL). The datasets were obtained from two elicitation experiments (real and nonce words tasks).

Previous studies bring inconclusive evidence on the extent to which CLI affects the acquisition of grammatical gender in the heritage and majority languages of bilinguals. Some studies demonstrate that structural similarities may facilitate language development, while differences between the two languages may impede language acquisition (Cornips and Hulk, 2008; Dieser, 2009; Hulk and Van der Linden, 2010; Brehmer and Rothweiler, 2012; Eichler et al., 2013; Schwartz et al., 2015; Meir et al., 2017; Egger et al., 2018; Kaltsa et al., 2019). The direction of influence and the associated effect (acceleration or delay) are shown to be affected by the properties of the gender system in terms of transparency and frequency of the gender cues it offers to the learner as well as by various language external factors. Numerous studies demonstrate that parental input and bilingual contexts shape bilingual language acquisition, including the acquisition of gender (Gathercole and Thomas, 2005; Armon-Lotem et al., 2011; Chondrogianni and Marinis, 2011; Paradis, 2011; Unsworth et al., 2014; Mitrofanova et al., 2018). The amount and quality of input is related to the success or failure in language acquisition (for an overview see Armon-Lotem and Meir, 2019).

In the current study, we consider possible effects of CLI together with language-external variables, such as language exposure and use, literacy training, and sociodemographic origin of the speakers. Furthermore, we consider the importance of morphophonological gender cues in the context of HL teaching in Norway, Germany, Israel, Latvia, and the United Kingdom that have very active HR communities. The participants in our study have received language and literacy training in complementary schools and through HL immersion. In order to advance a dialogue between bilingualism research and HL education, one of the goals of our paper is to identify HSs’ educational needs related to the learning of grammatical gender and to highlight some strategies that can facilitate the learning of grammatical gender.

Internal and External Factors in Gender Acquisition

Language-Internal Factors, Cross-Linguistic Effects

While it is obvious that acquisition outcomes in heritage bilinguals are determined by extra-linguistic factors, specifically quality and quantity of input, there is substantial evidence that language-internal factors play an additional role. Internal factors that might be crucial for how fast gender is acquired include (i) the number of gender categories (ii) the variety and transparency of gender assignment cues, and (iii) the variety and transparency of structural cues, i.e., gender agreement marking on elements that are in a syntactic relation with the noun. When comparing gender acquisition across languages, children acquiring languages with more transparent systems start to mark gender at an earlier age and converge on the target system faster (e.g., Kupisch et al., 2002; Blom et al., 2006; Rodina and Westergaard, 2017). Broadly speaking, three types of languages can be distinguished: Type I: languages with transparent gender-marking systems; Type II: languages with semi-transparent systems; and Type III: languages with opaque systems. Amongst the factors listed in (i–iii), formal transparency seems to be more important for acquisition than the number of gender categories, because some three-way gender systems (e.g., Greek and German) are acquired earlier than some two-gender systems with opaque assignment (e.g., Dutch and Norwegian) (e.g., Eichler et al., 2013; Unsworth et al., 2014; Egger et al., 2018; Kaltsa et al., 2019).

Italian and Spanish exemplify Type I, as nominal endings often provide unambiguous cues for a particular gender; other gender-marked elements are often phonologically similar or identical to these endings (e.g., It. la mia casa rossa “the.F my.F red.F house(F)”). Nouns are almost always accompanied by articles in these languages and bare nominals are the exception. Gender-marking errors are very rare in monolingual children acquiring Italian and Spanish (e.g., Chini, 1995; Kupisch et al., 2002; Kuchenbrandt, 2005).

In Type II languages, gender-assignment is semi-transparent and predicted by formal (phonological and morphological cues) or semantic (natural gender) cues.3 Some of the cues are highly transparent, while others are ambiguous, leading to some overgeneralization errors (cf. Gvozdev, 1961; Ceitlin, 2005 for Russian). This is true for Russian, Latvian and Hebrew, which are discussed in more detail in section “Gender Assignment in Russian, Norwegian, German, Hebrew, Latvian, and English.” German is somewhat less transparent, as many gender cues only reflect probabilistic tendencies rather than rules.

Norwegian and Dutch are representative of Type III: Nouns in these languages provide hardly any formal or semantic cues to gender assignment, although there are articles, which provide structural cues. It has been widely shown that children acquiring these languages struggle with gender throughout their preschool years (Blom et al., 2006; Rodina and Westergaard, 2013, 2015).

According to Egger et al. (2018), cross-language variation between the gender systems in terms of the number of gender values and especially the frequency and transparency of the morphophonological cues for gender can lead to acceleration or delay in bilingual acquisition. This influence is argued to be indirect in that properties of one system (usually less complex, more transparent/reliable and exhibiting higher frequency) may lead to an increased awareness of the properties of another system. Egger et al. (2018) have argued that Greek facilitates gender discovery in Dutch by Greek-Dutch bilinguals compared to English-Dutch bilinguals as a result of early and increased awareness of gender in Greek. Hulk and Van der Linden (2010) have proposed CLI from French and Spanish to Dutch with an accelerating effect in Dutch due to the transparency of the respective Romance systems. Kaltsa et al. (2019) have shown advantages of Greek-German children over Greek-English children in the acquisition of gender marking in Greek: Although German has a semi-transparent system that is different from Greek, it is arguably more beneficial to gender acquisition than the simultaneous acquisition of a language without grammatical gender. Schwartz et al. (2015) argue that the presence of gender in bilinguals’ majority languages (e.g., Hebrew and German) has a facilitating effect on gender assignment in HR, while the absence of gender (e.g., in English and Finnish) can cause a delay. At the same time, the acquisition of HR in the context of a non-transparent gender system like Norwegian was shown to be delayed only in the absence of sufficient input in the HL (Rodina and Westergaard, 2017). Furthermore, Cornips and Hulk (2008) proposed that structural similarities in gender systems, as found e.g., in the Heerlen dialect (a variety of Limburgish) and Dutch, can have an accelerating effect too. Similarly, Kupisch and Klaschik (2017) show that there are no delaying effects if the gender systems of relatively similar varieties, such as Standard Italian and Venetian, are acquired simultaneously. By contrast, Eichler et al. (2013) argue that neuter marking in German is delayed in children who acquire a two-way gender system at the same time, like the one found in French, Italian or Spanish. Delays in the acquisition of neuter gender have also been observed for Russian-German and Polish-German bilinguals (Dieser, 2009; Brehmer and Rothweiler, 2012), but it remains unclear whether these are the effects of bilingualism, since similar delays have been reported for monolinguals.

These studies suggest that there may be acceleration (and in some cases delay) in the acquisition of gender in bilinguals acquiring two languages with grammatical gender. These effects appear to be linked to the transparency, reliability, and frequency of gender cues. In our view, the specifics of CLI in gender acquisition are still unclear and the effects are somewhat problematic in light of evidence that gender acquisition is cue-driven, such that children are sensitive to fine distinctions in gender assignment (cf. Rodina and Westergaard, 2012; Mitrofanova et al., 2018). The cue-based approach proposed by Westergaard (2009) argues that children are highly sensitive to microvariation in the input, paying attention to fine distinctions in syntax, morphology, and information structure from early on. This approach has been supported for both mono- and bilingual acquisition. This means that in the acquisition of gender in Russian, where a number of different morphophonological gender cues can be distinguished, it is crucial to address cross-linguistic effects in relation to the specifics of the different cues across the two languages involved as well as their expression on gender targets via agreement. The study of CLI should also consider confounding effects of language-external factors, which we turn to in the next section.

Language-External Factors

The literature on language development of bilingual children has consistently shown that one of the most important language-external factors predicting bilingual language acquisition is the amount of exposure (Gathercole and Thomas, 2005; Guiberson et al., 2006; Armon-Lotem et al., 2011; Blom and Vasić, 2011; Chondrogianni and Marinis, 2011; Paradis, 2011; Anderson, 2012; Unsworth, 2013, 2015; Paradis and Jia, 2016, among many others). In a setting with one dominant societal language and a minority language, a child’s input is typically divided between the two languages and comes from two main sources: home and school. The success in the acquisition of the majority language is typically linked to input at school. It has been repeatedly shown that more exposure to the majority language at school reliably predicts vocabulary size, accurate morphology, narrative skills, and greater use of complex sentences in that language (Goldberg et al., 2008; Paradis, 2011; Paradis and Kirova, 2014; Paradis et al., 2017). At the same time, the link between the acquisition of the majority language and its use in the home is not that strong. Studies by Sorenson Duncan and Paradis (2018, 2019) demonstrated that higher use of the majority language by mothers at home had very little or no effect on the child’s skills in that language, while higher use of the minority or heritage language by mothers correlated significantly with stronger HL skills. Similar findings come from the study by Rodina and Westergaard (2017), who find no effect of family type (minority language family vs. mixed family) on the acquisition of grammatical gender in the majority language. On the other hand, the study finds a significant effect of family type (i.e., the amount of HL use at home) on the development of grammatical gender in the HL.

To sum up, the use of the majority language at school has been found to have a strong effect on the acquisition of the majority language, while the use of this language at home has only little or no effect. At the same time, the use of the HL at home has a profound effect on the acquisition of the heritage language. Little is known about whether and to what extent the use of the HL outside of the home contributes to the development of the minority language. There is evidence from studies with adult heritage bilinguals that if the HL is used as a medium of instruction at school, speakers can become indistinguishable from monolinguals in both their HL and majority language (Kupisch and Rothman, 2018), but these results were based on a rather small dataset. In our study, we aim at filling this gap by considering the effects of a variety of extra-linguistic factors, especially the amount of instruction offered in a HL, on the acquisition of grammatical gender in HR by children in Norway, Germany, Israel, Latvia, and the United Kingdom.

Gender Assignment in Russian, Norwegian, German, Hebrew, Latvian, and English

Russian assigns nouns to one of three gender classes, masculine, feminine and neuter, where masculine is considered the grammatical default. Based on dictionary counts (Corbett, 1991:78), the frequency of masculine nouns in Russian is 46%, while there is 41% feminine and 13% neuter nouns. Gender is expressed only in the singular on adjectives, possessives and demonstrative pronouns, as well as verbs in the past tense. In this paper, we only consider gender marking on the adjectives in the nominative singular.

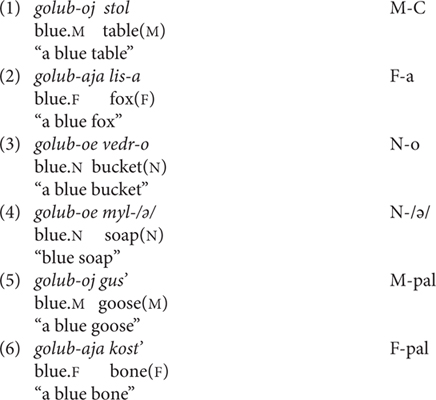

Russian nouns are assigned gender based on declensional class endings, henceforth referred to as morphophonological cues. In the majority of cases, noun suffixes in the nominative singular, which is the citation form of a Russian noun (Corbett, 1991:35), can be used to predict gender. Therefore this form is investigated in the present study. Most masculine nouns end in a consonant (stol “table(M)”), while most feminine nouns end in -a (lisá “fox(F)”). It should be noted that in some cases the -a ending is realized as -/ǝ / (schwa) in the unstressed position (párt-/ǝ / “desk(F)”). Both the M-C and F-a cues (stressed and unstressed) appear to be reliable gender predictors as the respective noun classes are acquired early by monolinguals, at approximately the age of two (Gvozdev, 1961; Ceitlin, 2005, 2009). This is likely due to their high frequency and a small number of exceptions. Neuter nouns end in -o (vedro “bucket(N)”) or -/ǝ / (schwa) (mýl-/ǝ / “soap(N)”) when the final -o is unstressed. Nouns ending in -o and -/ǝ / are infrequent, which may explain why neuter is typically acquired later by monolinguals. Moreover, the N-/ǝ / cue presents additional difficulty for learners, since the pronunciation of the nominative singular of these nouns is indistinguishable from stem-stressed feminines ending in an unstressed -a, as both have reduced vowels (Iosad, 2012). In monolingual acquisition, gender agreement with transparent neuters ending in -o is usually mastered between 3;0 and 4;0 years of age. Errors with neuters ending in -/ǝ / persist until approximately the age of 6;0 due to overgeneralization of feminine. While Russian children have been shown to overgeneralize feminine agreement with non-transparent neuter nouns (Gvozdev, 1961; Popova, 1973), the opposite pattern, i.e., neuter agreement with stem-stressed feminines, has not been attested. While the lack of transparency can explain the delay in the acquisition of neuter with nouns ending in -/ǝ /, additional factors are at play, such as overall low frequency of neuters as well as scarcity and ambiguity of the gender cues through agreement on gender targets. Gender agreement may have an additional delaying effect since the majority of the adjectival endings in Russian are unstressed, e.g., krasn/ǝ(j)ǝ/ myl-/ǝ/ “red soap(N).” This makes their phonological form indistinguishable from the feminine, e.g., krasn/ǝ(j)ǝ/ lis-a “a red fox(F).” Finally, there are two relatively large classes of Russian nouns that end in a palatal consonant, which may be either masculine (M-pal, gus’ “goose(M)”) or feminine (F-pal, kost’ “bone(F)”). Gender assignment with these nouns has been found to be problematic in monolingual acquisition, where overgeneralization of masculine has been observed with feminine nouns during the preschool years (Gvozdev, 1961; Ceitlin, 2005, 2009). The opposite pattern, i.e., feminine forms used with masculine nouns ending in palatal consonants, has not been attested in monolingual acquisition.

The examples in (1–6) provide an overview of Russian noun classes. In all examples we provide nouns in the nominative singular. In the glosses, the gender of the noun is marked in parentheses and the agreeing item is marked after a full stop. In this paper, we only consider adjective-noun agreement. Within the noun phrase, gender is also expressed on possessive and demonstrative determiners, but there are no articles in Russian.

German has a three-way gender system as well, while English does not have grammatical gender. The three other majority languages – Norwegian, Latvian, and Hebrew – have two-way gender systems. The relevant dialects of Norwegian differentiate between common and neuter gender, while Latvian and Hebrew distinguish between masculine and feminine. Similarly to Russian, masculine is the most frequent category in Norwegian, German (along with feminine), Hebrew, and Latvian, while neuter, on the other hand, is very infrequent and present in only two of the contact majority languages, German, and Norwegian.

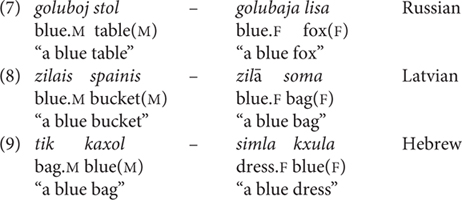

The gender systems of Latvian and Hebrew show interesting parallels with Russian in both gender assignment and gender agreement, while German and Norwegian pattern differently in both respects. Despite the fact that Latvian and Hebrew do not have neuter, the languages use similar cues for masculine and feminine: just like Russian, the gender of Latvian nouns can largely be predicted based on their endings in the nominative singular. Most masculine nouns end in consonants -s (e.g., spainis “bucket(M)”) or -š (e.g., vējš “wind(M)”) and most feminine nouns end in -a (e.g., soma “bag(F)”) or -e (e.g., pele “mouse(F)”) (Sokols et al., 1959). The same is true for Hebrew, where most masculine nouns end in a consonant (tik “bag(M)”) and feminine nouns in -a (simla “dress(F)”) or -t (e.g., rakevet “train(F)”) (Schwarzwald, 1982; Ravid and Schiff, 2015). These patterns in Latvian and Hebrew are transparent and regular. In addition, Russian, Latvian and Hebrew show similarities in gender marking on adjectives, illustrated in (7–9).

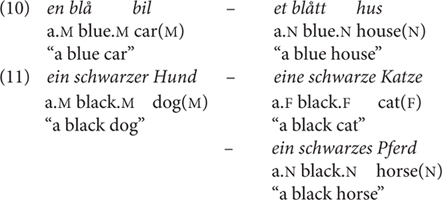

In contrast to Russian, the gender system of German lacks transparency in terms of morphophonological cues and the gender system of Norwegian (Tromsø and Oslo dialects) is considered to be (more or less) arbitrary, as there are no gender cues on the nouns themselves (cf. Rodina and Westergaard, 2013, 2015). Gender is marked on adjectives as well as on possessive pronouns and demonstratives in both languages. Unlike Russian, Norwegian and German have indefinite and definite articles (the latter is a suffix in Norwegian), which are the most frequent elements on which gender marking in visible. The examples in (10–11) illustrate gender distinctions in Norwegian and German indefinite DPs, respectively. In German, gender interacts with definiteness and case and there is considerable syncretism.

There are phonological (as well as morphological and semantic) cues to gender assignment in German, but phonological cues reflect probabilistic tendencies rather than rules. For example, disyllabic nouns ending in [ǝ] are associated with feminine gender 90% of the time (e.g., die Katze “the.F cat(F)”), monosyllabic nouns starting with the onset cluster /∫/ + C_ are associated with masculine gender 81% of the time (e.g., der Strand “the.M beach(M)”), and nouns ending in [εt] tend to be neuter (e.g., das Bett “the.N bed(N)”) (see e.g., Köpcke, 1982; Wegener, 1995; Schwichtenberg and Schiller, 2004).

In sum, in terms of gender assignment, Russian exhibits six morphophonological cues. Only two cues, M-C and F-a, are highly frequent, transparent, and predictable. The remaining four cues (M-pal, F-pal, N-o, N-/ǝ/) are less transparent and less frequent. This is especially the case for the neuter, N-o and N-/ǝ/, where transparent and reliable cues from gender agreement with attributive adjectives are scarce. HR in this study is in contact with three semi-transparent languages, German, Hebrew, and Latvian, as well as one non-transparent language, Norwegian, and a language without grammatical gender, English. Only Latvian and Hebrew show direct parallels with Russian and only for the highly frequent, transparent, and predictable cues, M-C and F-a. Overall, the gender systems of Latvian and Hebrew exhibit higher transparency and predictability than those of German and Norwegian, but the latter two distinguish neuter.

The Acquisition of Gender in Heritage Russian

The acquisition of gender by HR-speaking children appears to be qualitatively similar to monolingual acquisition, which is confirmed by both observational (e.g., Dieser, 2009) and experimental data (Schwartz et al., 2015; Mitrofanova et al., 2018; to some extent also Rodina and Westergaard, 2017). For instance, Schwartz et al. (2015) conducted an elicitation study investigating adjectival gender agreement with transparent and opaque Russian nouns in two groups of Russian monolinguals (aged 3;0–4;0 and 4;0–5;0) and four groups of bilingual children aged between 4;0 and 5;0, who had English, Hebrew, German or Finnish as their majority language. While quantitative differences in accuracy between monolinguals and bilinguals were found, Schwartz et al. (2015) concluded that error patterns were the same across all participant groups. The results are to a certain extent confirmed by the experimental study in Rodina and Westergaard (2017), who investigated the acquisition of gender assignment in Russian-Norwegian preschoolers living in Norway. In their study, the majority of children were both quantitatively and qualitatively similar to age-matched Russian monolinguals, while a small group of children exposed to mostly Norwegian in the home were significantly less accurate with respect to gender assignment. Crucially, they also found qualitative differences between monolinguals and this small group of bilingual children, who overgeneralized masculine agreement across the board (with most feminine and neuter targets), i.e., they seemed to be developing a variety of Russian without gender.

A somewhat different scenario has been reported for young adults speaking HR in the United States (Polinsky, 2008). In this study, low-proficiency speakers develop a two-gender system consisting of masculine and feminine only. Quantitative and qualitative differences between monolinguals and bilinguals have been linked primarily to the differences in the amount of exposure (Polinsky, 2008; Schwartz et al., 2015; Rodina and Westergaard, 2017; Mitrofanova et al., 2018). Lower exposure in bilinguals has been argued to have a negative affect on bilinguals’ gender cue sensitivity. Unsurprisingly, the effect of lower exposure in bilinguals is especially evident with low-frequency forms (i.e., Russian neuters) and the forms where gender assignment cannot be done based on the morphophonological form in the nominative singular (e.g., feminine nouns ending in a palatal). In addition, low-frequency nouns belonging to these groups can be expected to elicit more errors than high-frequency items (Dieser, 2009).

Present Study

The present study places HR in the context of five societal majority languages, Norwegian, German, Hebrew, Latvian, and English. The languages show similarities and differences in gender assignment and provide an excellent test case for assessing the effects of CLI and external factors on child bilingual acquisition of grammatical gender focusing on sensitivity to morphophonological gender cues. The study asks the following three main questions:

RQ1: Is there evidence for CLI in bilingual acquisition of grammatical gender in HR?

RQ2: How does the amount of exposure to HR in the home affect gender assignment?

RQ3: How does the amount of exposure to HR outside the home affect gender assignment?

More specifically, RQ1 investigates whether the properties of the gender systems in contact may strengthen or weaken bilingual sensitivity to the six morphophonological cues in Russian. The nature of the Russian gender system (see section “Gender Assignment in Russian, Norwegian, German, Hebrew, Latvian, and English”) and its acquisition patterns (see section “The Acquisition of Gender in Heritage Russian”) suggest that bilingual performance with the masculine cues, M-C and M-pal, may not be affected by CLI and may be at ceiling since masculine is the default gender in Russian. Previous research on HR shows that these cues are unproblematic even in bilinguals with comparatively little input and low proficiency in HR (Rodina and Westergaard, 2017; Mitrofanova et al., 2018). The latter scenario can of course indicate that bilinguals with comparatively little input and low proficiency in HR do not acquire gender at all, since masculine is used as a default across all subclasses of nouns by these speakers. Given this, the acceleration or delay effects might be expected for F-a, F-pal, N-o and N-/ǝ/ cues.

As mentioned above, previous studies have shown that contact with transparent gender systems may lead to increased awareness of the properties of another system (Schwartz et al., 2015; Egger et al., 2018). The degree of gender transparency and predictability varies for the four gender languages in contact, so that Latvian and Hebrew are most transparent, followed by German and then Norwegian. Based on this, one can predict higher performance on gender assignment in Russian-Latvian and Russian-Hebrew bilinguals compared to Russian-German bilinguals. Delays may be expected in Russian-Norwegian and especially Russian-English bilinguals. However, these predictions are problematic, as they do not take into account fine-grained similarities and differences in terms of gender values and cues across the languages involved. While Latvian, Hebrew and German have feminine, only Latvian and Hebrew share the F-a cue. Will acceleration effects for the F-a nouns be restricted to Russian-Latvian and Russian-Hebrew bilinguals? Another possible outcome is ceiling performance with the F-a cue across all participant groups, due its high frequency, transparency, and predictability.

Asymmetries in the number of gender values across gender languages add further complexity. Thus, accuracy on F-a and F-pal nouns might be lower in Russian-Norwegian bilinguals than in Russian-Latvian, Russian-Hebrew, and Russian-German bilinguals. In principle, accuracy on neuter cues could be higher in Russian-German and Russian-Norwegian bilinguals, but this is unlikely in light of the overall low frequency and predictability of neuter in Russian as well as in the contact languages. Finally, contact with English, a language without grammatical gender, may result in low accuracy across all non-masculine gender cues in Russian-English bilinguals (cf. Kaltsa et al., 2019). Yet, gender acquisition in the Russian-English language pair may be simply predicted by the gender cues available in Russian and the amount of input, with no delaying effect from English (cf. Unsworth et al., 2014 for Greek-Dutch and English-Dutch bilinguals). We will consider these different scenarios in a cross-linguistic comparison for the six morphophonological cues.

RQ2 and RQ3 address confounding effects of various extra-linguistic factors that have been shown to affect the acquisition of gender in bilingual children. HL exposure in the home is one of the key external factors investigated in the present study, factored in through a number of background variables, including the child’s age, age of onset of acquisition of the majority language, family type (Russian only or mixed), and kindergarten start. In addition, we investigate the effects of HR exposure outside the home with a special focus on HR instruction. The bilinguals live in different urban areas and are enrolled in different types of HR instruction (cf. see section “HR Communities and Education in Israel, Germany, Norway, Latvia, and the United Kingdom”). Some children are exposed to HR in immersion kindergartens and schools, while others attend complementary language programs and receive a limited number of hours of HR instruction per week. To capture these differences we quantify the proportion of current (weekly) exposure to HR Instruction for all participants in the following urban areas: Oslo and Tromsø (Norway), Berlin, Stuttgart, and Singen (Germany), London and Reading (the United Kingdom), Riga (Latvia) as well as Petach Tikva and Rishon-le-Zion (Israel). The size of the HR community in these areas differs, which may have an effect on the bilingual performance. Therefore, three additional independent variables capturing bilingual experience outside the home are included into the analysis: size of the HR community, current exposure to HR instruction, and main language of instruction.

Finally, we explore the implications that the in-depth knowledge about the gender systems and the acquisition mechanisms might have for HL learners, parents, and educators. In our discussion we address research findings from simultaneous bilingual language acquisition showing that the transparency of the gender system in terms of morphophonological cues and learner sensitivity to the cues are critical factors in gender acquisition (cf. for HR: Polinsky, 2008; Dieser, 2009; Rodina and Westergaard, 2015, 2017; Schwartz et al., 2015; Mitrofanova et al., 2018). Furthermore, the amount of input a learner receives affects cue sensitivity and defines an outcome of bilingualism. Thus, given the linguistic knowledge that we have, we would like to explore strategies that can encourage and support cue sensitivity in bilingual learners – strategies that HL learners, their parents and educators may take advantage of.

HR Communities and Education in Israel, Germany, Norway, Latvia, and the United Kingdom

HR communities in the five national contexts investigated – Israel, Germany, Norway, Latvia, and the United Kingdom – constitute relatively large migrant groups. The communities are diverse, involving different paths to migration, educational levels, national identities, plans for settlement, etc. (cf. Ivashinenko, 2018). In Israel, Germany, Norway, and the United Kingdom, our bilingual participants are second-generation migrants whose parents migrated from Russia over the last two decades. The HR community in Latvia is different in that ethnic Russians have lived there since the 19th century, and the Russian language has had a formal status in the country, especially during the Soviet era. Our participants were recruited through HR complementary schools or immersion kindergartens and schools, which are the main HL providers outside the home. As becomes clear below, the amount of exposure to HR outside the home varies considerably, as only some participants are enrolled in dual language immersion programs, while others have instruction that only amounts to a few hours per week.

Russians are the 14th largest migrant population in Norway (21,504 in 2019, according to Statistics Norway, 2019) with the peak of migration having occurred between 2001 and 2006. Considerable numbers of Russian-Norwegian bilinguals are raised in Russian families where both parents are migrants from Russia or in Russian-Norwegian families where the mothers are Russian and the fathers are Norwegian with little or no knowledge of Russian (cf. Henriksen et al., 2010; Timofeeva and Wold, 2012). Bilinguals from both family types participated in the present study. Data collection took place in two urban areas: Oslo, the capital, and Tromsø, the largest city in North Norway. Our participants were recruited from one of the five complementary Russian schools in Oslo. The Oslo school is private and offers half a day (5 h) complementary education in Russian on weekends. The Tromsø school offers complementary education in Russian: 1 h for preschoolers and 2 h for primary school children on weekends.

Of the 20.8 million people with a migration background in Germany, 1.4 million (6.6.%) are from the Russian Federation (information from BAMF, 2017; Statistisches Bundesamt, 2019). The data collection for the present study took place in three urban areas: Berlin, the capital, Stuttgart, the largest city in Baden-Württemberg, and Singen, a small town in South Germany. In large cities there are educational centers that offer Russian language and culture immersion. Our participants from Berlin attended a kindergarten with a 50% Russian immersion program, and participants from Stuttgart attended a kindergarten with 90% immersion in Russian. Bilinguals from Singen attended a private complementary Russian school for children between the ages of 1 and 15, 2 h weekly on average.

More than one million speakers of Russian live in Israel (approximately 15% of the total population, Statistical Abstract of Israel, 2010). Russian-speaking migrants promote the acquisition of Russian among their children, including those who are born in Israel (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2011). For younger children up to the age of 5, there are private Russian-only and bilingual Russian-Hebrew daycares; for older children there are complementary Russian-literacy schools and evening classes (Schwartz et al., 2011). The children recruited for the current study were all born and raised in Israel in only-Russian or mixed Russian-Hebrew families. Data collection was carried out in two cities, Petach Tikva and Rishon-le-Zion, which have large Russian-speaking communities. The children were recruited from private educational settings providing a 6-day bilingual program for younger children. In such programs, pre-school teachers carry out an educational program in Russian and Hebrew. Older children (aged 5–8) attend obligatory Hebrew-speaking kindergartens/schools in the morning and join bilingual educational settings after school.

Although the only state language of Latvia is Latvian, it has traditionally been a multinational country, with ethnic Russians constituting the most numerous minority group, about 26% overall (Latvijas Republikas Centrālā statistikas pārvalde [Central Statistical Bureau of the Republic of Latvia], 2013). In Riga (where the data for the present study was collected) 39% of the respondents reported mainly using Latvian at home, while approximately 50% mainly use Russian. Our participants were all raised in mixed Russian-Latvian families. Many kindergartens and schools use Russian as the language of instruction, yet, our participants attended kindergartens with only Latvian as the language of instruction.

The UK Office for National Statistics estimated that in 2011 there were 67,366 speakers of Russian in England and Wales (0.12% of the population UK Census, 2011). Data collection for our study took place in two urban areas: London and Reading. In both cities there are Russian language centers which are complementary educational organizations set up by the HR communities outside of mainstream schooling. Our participants were recruited from one of the six complementary schools in London. The London school is private and offers half a day (5 h) complementary education in Russian on the weekends. The Reading school offers complementary education in Russian on the weekends, 4 h weekly.

Methodology

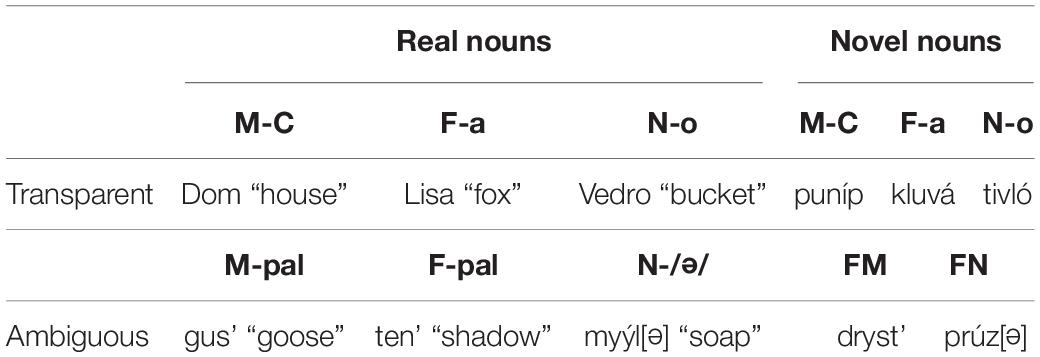

We carried out two experiments in (most of) our bilingual populations, a real and a nonce word task. The procedure used in the experiments is an adapted version of the elicited production tasks used in Rodina and Westergaard (2015) and Mitrofanova et al. (2018). In Experiment 1, the stimuli were real nouns referring to countable objects, illustrated in Table 1. The nouns were divided into six conditions (five nouns in each condition): feminine, masculine and neuter nouns with transparent as well as ambiguous gender cues. To avoid a gender match across the languages, for each language we chose only nouns whose translation equivalents in the majority language had a different (non-congruent) gender (e.g., Rus. grib(M) vs. Lat. sçne(F) “mushroom”). The real nouns consisted of one to four syllables (e.g., dom “house”; lisa “fox”; moloko “milk”; odejalo “blanket”). The accuracy measure was coded as 1 for target production (e.g., goluboj dom “blue.M house(M)”) and 0 for non-target production (e.g., golubaja dom “blue.F house(M)”/goluboje dom “blue.N house(M)”).

In Experiment 2, the stimuli were novel nouns conforming to Russian phonotactics. These nonce nouns were one or two syllables and were divided into five conditions (five in each condition): nouns containing transparent feminine (F-a), masculine (M-C) and neuter (N-o) gender cues, as well as stem-stressed schwa-final nouns (either feminine or neuter, FN) and nouns ending in palatal consonants (either masculine or feminine, (FM). As in Experiment 1, the nouns were presented as labels for colored pictures. The pictures used in this experiment depicted items selected from the Novel Object and Unusual Name Database (NOUN; Horst and Hout, 2016). In order to avoid neighborhood density effects, only nouns that had no nominal phonological neighbors were selected. For this, we used the Phonological Corpus Tools software (PCT, Hall et al., 2016), which enables us to check for any minimal pairs with nouns in the Frequency Dictionary of Russian (Sharoff, 2002).

Pictures of the target nouns were presented as Power Point slides on a laptop screen. During each trial, two identical objects of different colors appeared on the screen. The name of the objects was introduced to the participant in the lead-in sentence in Russian (“This is what we call…”). To elicit adjectival agreement, the participant was then prompted to name the objects on the screen along with their colors (“This is a blue dress, and this is a pink dress”). After the participant had named the objects, the experimenter pressed a button causing one of the objects to disappear. Again, the participant was prompted to name the object that disappeared, along with its color. Thus, we elicited three adjective-noun combinations per stimulus from each participant. Only the first response was used for the analysis presented here.

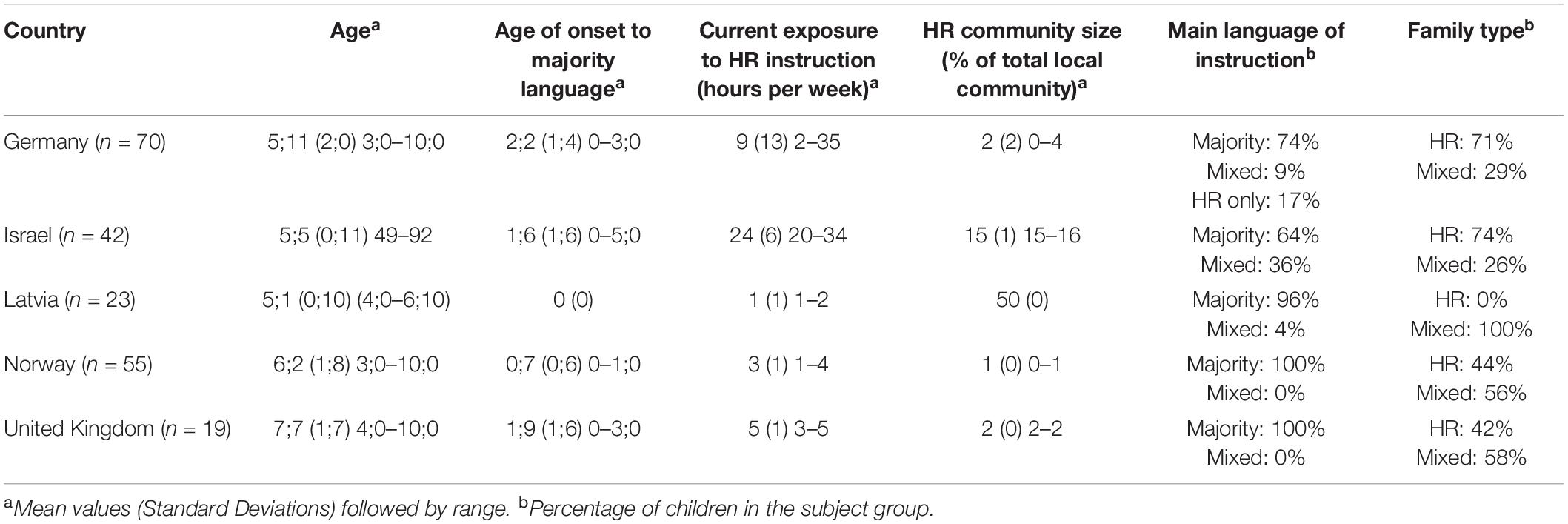

An overview of the participant groups and their background is provided in Table 2. The statistical analysis of the participant data shows that there was an effect of country for Age (F(4,204) = 8.17, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.14): post hoc analysis with a Bonferroni correction revealed that the United Kingdom sample was older than the other groups (p < 0.001), while there were no significant differences between the other groups. There were differences between the groups on Current Exposure to HR (F(4,204) = 448.50, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.90). A post hoc analysis revealed that the children from Israel had the largest amount of current exposure in an educational setting, which was significantly different from the rest of the groups. The children in Germany had significantly more instruction in HR than the children in Latvia and Norway, yet there were no significant differences between Latvia, Norway, and the United Kingdom as determined by pairwise post hoc tests. There were significant differences between the countries with respect to the community size from which the children were recruited (F(4,204) = 11927.92, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.99). All the differences between the communities were significant with a Bonferroni correction. Pair-wise comparisons using a Tamhane’s T2 for the unequal variance with an adjusted alpha-level showed that the HR community size was significantly larger in Latvia as compared to the other countries in the study, followed by Israel. No differences were observed in the HR community size in Germany and the United Kingdom.4 In Norway, the HR community size was the smallest. There were differences between the distribution of mixed vs. HR-only families across the five countries (χ2 (4) = 45.66, p < 0.001). The proportion of HR-only families was highest in Germany and Israel, it was significantly smaller in Norway and the United Kingdom, where bilinguals from mixed families were nearly as many as those from HR-only families. The Russian-Latvian bilinguals were all raised in mixed families. There were significant differences between the samples on the distribution of the main language of instruction across the five countries (χ2 (8) = 63.39, p < 0.001). The majority language was the main language of instruction for all or nearly all the bilinguals in Norway, Latvia, and the United Kingdom, but its presence in instruction was significantly lower in Germany and Israel.

The same participants completed the nonce-word task, but the sample size of the children was somewhat smaller than in the real-word task for Germany (n = 65 vs. n = 70, respectively), Israel (n = 41 vs. n = 42, respectively), and the United Kingdom (n = 12 vs. n = 19, respectively). The children in Latvia were not tested on the nonce-word experiment because the data collection in Latvia took place in connection with a different research project and it was not possible to run experimentation on both tasks again.

In order to answer the research questions of the study, we ran generalized linear mixed models with binary dependent variables – Experiment 1: the accuracy of gender assignment; Experiment 2: the probability of masculine gender assignment. We evaluated the effect of language-internal and language-external variables. Two variables were treated as language-internal: Experimental condition and Country. The variable Country represents five Majority Languages with gender systems that vary with respect to the presence/absence of grammatical gender, the number of grammatical genders and transparency of gender cues, as discussed in section “Gender Assignment in Russian, Norwegian, German, Hebrew, Latvian, and English.” The variable Condition maps onto transparency of the gender cues in Russian. The variable Family Type (HR family vs. mixed family) addressed the role of exposure to HR in the home (RQ2). The variables addressing the role of exposure to HR outside the home (RQ3) were Size of the HR Community, Current Exposure to HR Instruction, Kindergarten start, and Main Language of Instruction. Age and Age of Onset to Majority Language were relevant for both RQ2 and RQ3. Language-external variables were inserted into the analysis as continuous variables. Participants and Items were entered into the models as random factors.

Results

Real Words

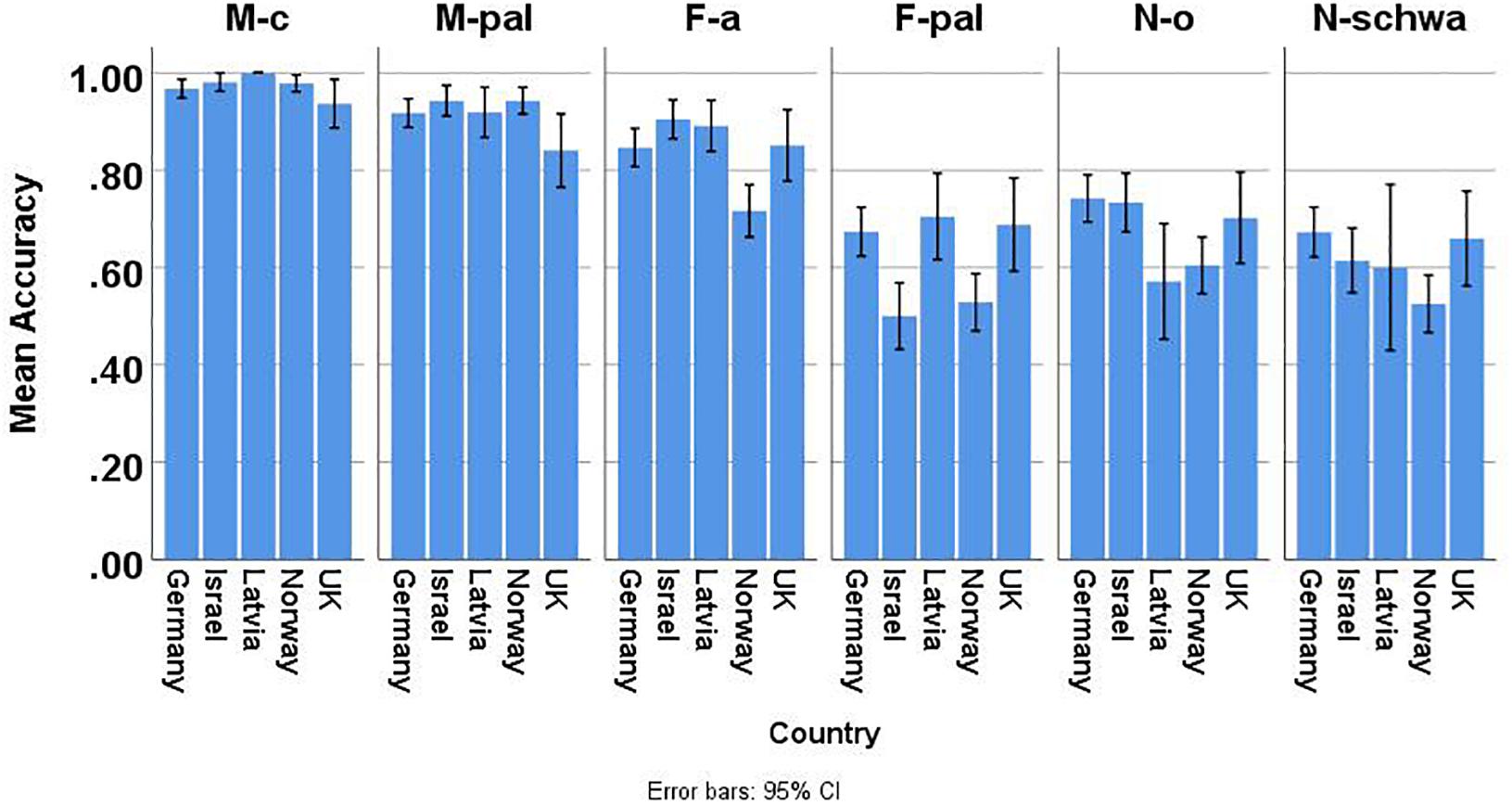

To analyze the results of the real word task we fit two generalized linear mixed models with the help of the R package lme4 (Bates et al., 2015). In the first model, Accuracy was estimated based on two predictors: Experimental condition (M-C, F-a, M-pal, F-pal, N-o, N-a) and Country (Germany, Israel, Latvia, Norway, the United Kingdom), as well as their interaction. Participants, Items, Age, and Family type (minority vs. mixed) were included as random effects. The effect of condition was significant, while the effect of country was not (see Figure 1). Children from all groups were significantly more accurate with respect to the two masculine conditions than all other conditions (M-C: M = 0.97; M-pal: M = 0.92). Furthermore, transparent F-a nouns (M = 0.84) were less error-prone than F-pal (M = 0.60) and neuter nouns (both N-o and N-/ǝ/: M = 0.68 and M = 0.61, respectively) in all groups. We ran post hoc pairwise comparisons of groups within conditions with the help of the R package emmeans (Lenth et al., 2019). The following two contrasts were significant: a) the children from Latvia were significantly more accurate on the F-pal condition than the children from Israel (compare M = 0.70 vs. M = 0.50) and b) participants from Norway were more accurate than participants from the United Kingdom on the M-pal condition (compare M = 0.94 vs. M = 0.84) (see Supplementary Appendix for the output of the model and post hoc pairwise comparisons).

In the second model, we examined the effects of seven background variables (Age, Family, Current Exposure to HR Instruction, Size of the HR Community, Main Language of Instruction, Age of Onset for Majority Language, and Kindergarten Start) on the accuracy of gender assignment with real words. Main Language of Instruction and Age of Onset for Majority Language were excluded as predictors, based on collinearity with other effects (if correlation was above 0.7) and model comparison (if the model fit was not significantly worse without this predictor than with it). The best model included Family, Age, Size of the HR Community, Current Exposure to HR Instruction and Kindergarten start as fixed effects. Participants, Items, Condition and Country were included as random effects. The model shows that three predictors, Family, Age and Size of the HR Community, have a significant effect on accuracy. Children from families with two Russian-speaking parents perform more accurately than children from families with one Russian-speaking parent. Age and Size of the HR Community both correlated positively with the children’s accuracy, indicating that older children were more accurate than the younger ones, and that children from communities with a higher proportion of Russian speakers performed better than children from communities with a lower percentage of Russian speakers.

We also fit an additional model to estimate the effect of the same five background variables on accuracy in four countries: Germany, Israel, Norway, and the United Kingdom. Latvia was excluded because the dataset differed substantially from those of the other countries: Although the experimental conditions were the same, the participant group in Latvia were younger than the children from other countries (4–6 vs. 4–10 years) and consisted only of children from mixed families. After model comparison, the best model for the dataset comprising data from the four countries included Family, Age, Size of the HR Community, Current Exposure to HR Instruction and Kindergarten start as fixed effects, while Participants, Items, Condition and Country were included as random effects. The model shows that Family, Age and Current Exposure to HR Instruction correlated significantly with Accuracy, while Size of the HR Community was marginally significant (see the output of the model in Supplementary Appendix).

Nonce Words

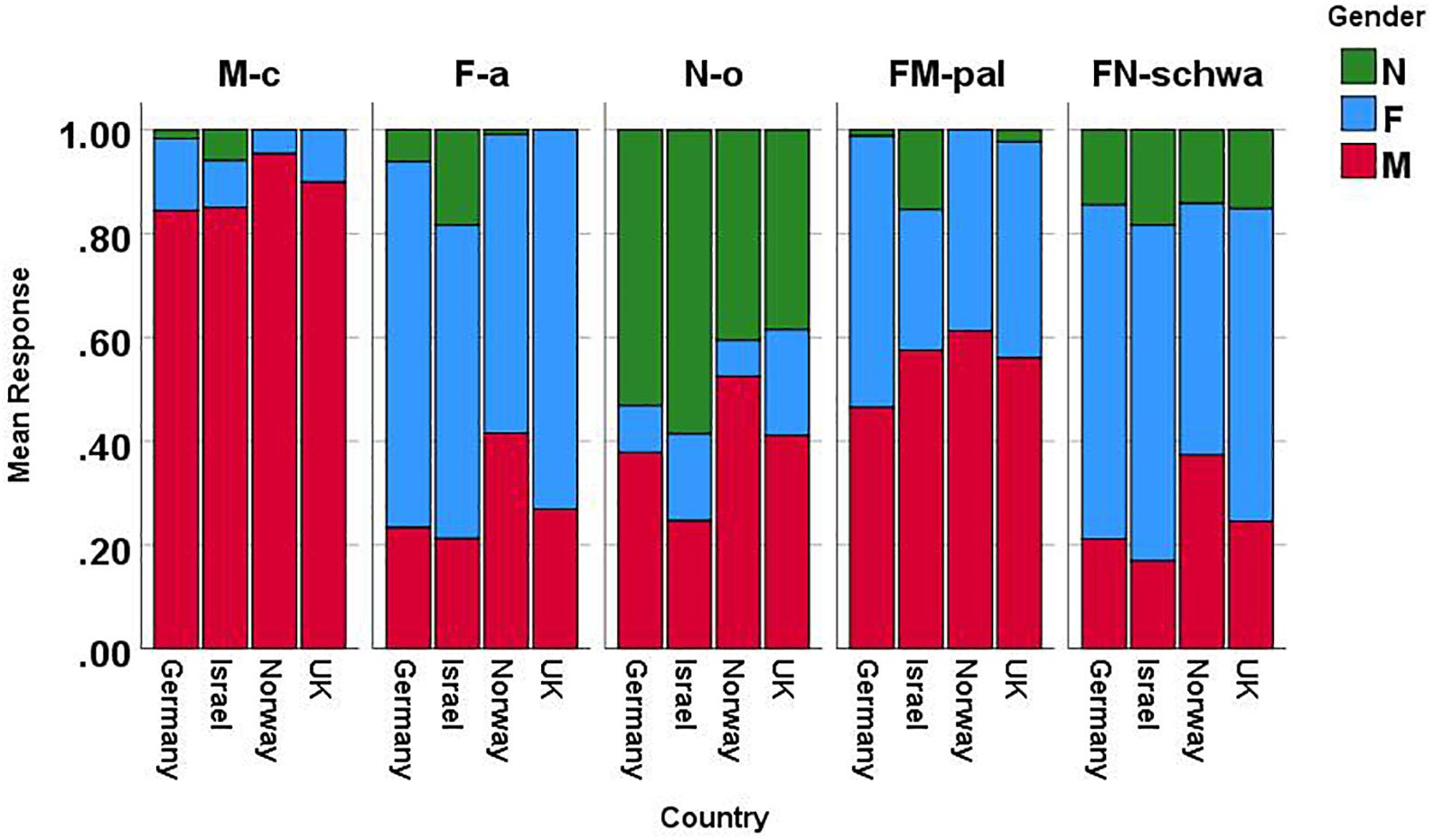

The nonce word task was conducted in Germany, Israel, Norway and the United Kingdom (see the Methodology section). To analyze the results we fit two generalized linear mixed models. In the first model we estimated the probability of masculine (i.e., the main default error pattern in all groups, see section “Real Words”) based on the effects of Condition and Country, as well as their interaction. Participants, Items, Age, and Family were included as random effects. The model shows that the effect of condition is significant (Figure 2). The children were sensitive to transparent gender cues on nonce words: on the transparent M-C condition masculine was the most frequent answer provided (M = 0.88), feminine was provided on the F-a condition (M = 0.68), while the preference of neuter responses was lower on the N-o condition (M = 0.50). In the ambiguous FM-pal condition, the responses were split between feminine and masculine (M = 0.43, M = 0.53, respectively). In the opaque FN-schwa condition, the responses were divided between feminine (M = 0.61), masculine (M = 0.24) and neuter (M = 0.15). Children from all groups were using more masculine in the FM-pal (M = 0.53), M-C (M = 0.88) and N-o (M = 0.32) conditions than in the F-a (M = 0.27) and FN-pal (M = 0.24) conditions. Furthermore, the effect of country was significant. Post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed the following significant contrasts: (a) the children from Israel used significantly less masculine than the children from Norway in all conditions except FM-pal; (b) the children from Norway used more masculine in the M-C condition than children from Germany; and (c) participants from Israel used significantly less masculine in the N-o condition than the children from Germany (see Supplementary Appendix for the output of the model and post hoc pairwise comparisons).

In the second model, we estimated the effect of seven background variables (Age, Family, Current Exposure to HR Instruction, Size of the HR Community, Main Language of Instruction, Age of Onset for Majority Language, and Kindergarten Start) on the probability of masculine responses. Size of the HR Community, Main Language of Instruction and Age of Onset for Majority Language were excluded as predictors based on collinearity with other effects (if the correlation was above 0.7) and model comparison (if the model fit was not significantly worse without this predictor). The best model included Family, Age, Kindergarten Start and Current Exposure to HR Instruction as fixed effects. Participants, Items and Condition were included as random effects. The resulting model shows that Family, Age, Kindergarten Start and Current Exposure to HR Instruction all significantly predicted the probability of using masculine. Age and Kindergarten Start correlated negatively with the likelihood of masculine, indicating that the older the children were and the later they had started kindergarten, the less likely they were to (over)use masculine. At the same time, the more exposure to minority language instruction the children had at the moment of testing, the lower was the probability to (over)use masculine. Finally, children from mixed families were significantly more likely to (over)use masculine than children from minority families.

Individual Profiles, Real Words

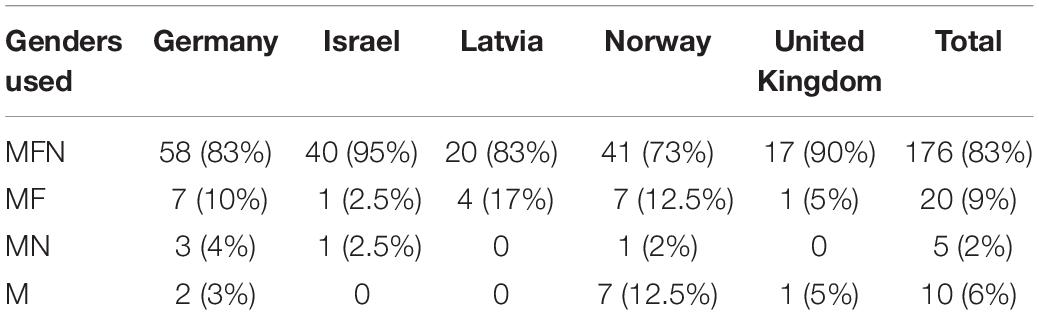

The majority of the children in our sample (174/211, 83%) used all three genders in their responses, illustrated in Table 3. No children exhibited F-only, N-only or FN patterns. At the same time, we found that ten children in our sample used M-only (this pattern can be dubbed “no-gender” due to the unmarked status of masculine agreement in Russian), 20 children used masculine and feminine, but no neuter (MF or “no-Neuter” pattern), and five children used masculine and neuter, but no feminine (MN pattern or “no-Feminine” pattern). We present the distribution of these patterns and their relation to the background variables in more detail. Note that the cross-language comparison of the individual profiles should be taken with caution, as the sample sizes in Germany, Israel, and Norway were considerably larger than those in Latvia and the United Kingdom.

M (“No-Gender”) Pattern

The majority of children with this pattern (7/10) come from mixed families (8/10) and from the younger age group: three- and four-year-olds. However, there were also three participants from the older age group (8–10), showing that although younger children are more likely to use exclusively masculine in their responses, older children can also exhibit this pattern. The majority of children in this group (7/10) come from Norway, two from Germany, and one from the United Kingdom. We propose that this is consistent with a substantially earlier kindergarten start in Norway (at age 1), as opposed to all other countries (at age 3 and later). All Russian-Norwegian bilinguals in our sample attended kindergarten in the majority language. Overall, these results clearly indicate that the M-only (“no-gender”) pattern is dependent on the amount of input: the less input the children have had in Russian (younger children, mixed families, earlier kindergarten start), the more likely they are to exhibit the M-only pattern.

MF (“No-Neuter”) Pattern

There were 20 children from all countries who used only feminine and masculine in their responses: seven in Germany, one in Israel, four in Latvia, seven in Norway and one in the United Kingdom. Based on the proportion of feminine used by the children in this group, we can further subdivide them into two groups: (1) eight children used feminine only once or twice (less than 10% of the time) and masculine in all other cases; (2) 12 children used feminine four and more times (13–66% of the time). Feminine was used exclusively in Feminine-compatible conditions by subgroup 1 (predominantly in the F-a condition, but three times also in the F-pal condition), while it was used in the Feminine-compatible conditions (F-a and F-pal) as well as in the Neuter-compatible conditions by subgroup 2. Note that feminine was not used in the M conditions. We propose that the pattern observed for subgroup 1 can be regarded as a sub-type of the all-masculine pattern, with occasionally rote-learned gender for certain feminine nouns (typically, transparent feminine ones). On the other hand, the pattern observed for subgroup 2 can be regarded as the next step in the acquisition of grammatical gender in Russian, where the children start making a regular distinction between feminine and masculine and establish regular morphophonological cues for each gender.

MN (“No-Feminine”) Pattern

This pattern was quite unexpected given that neuter has been reported to be acquired after the more frequent feminine gender. Looking more closely at the responses of the five children with this pattern, we observe that the proportion of neuter was less than 10% for each child: two children used neuter only once (and masculine in the remaining 29 trials), while three children used neuter twice (and masculine in 28 remaining trials). Almost all neuter responses were produced target-consistently with N-o nouns, while one response was produced with the N-/ǝ/noun (platje “dress”). Three children in the MN group are from Germany, one from Israel, and one from Norway. There were three five-year-olds, one three- and one eight-year old in this group. Four out of five children come from mixed families, and one from a HR family. Given that neuter is only used once or twice by these children, it seems impossible to conclude that they have acquired neuter gender. Alternatively, this pattern can be viewed as a sub-type of the only-masculine pattern, with occasional use of neuter (possibly rote-learned forms). Similar to the M-only pattern, this pattern correlates with the amount of input and is more likely to occur in younger children and children from mixed families than in children with a larger amount of input in Russian.

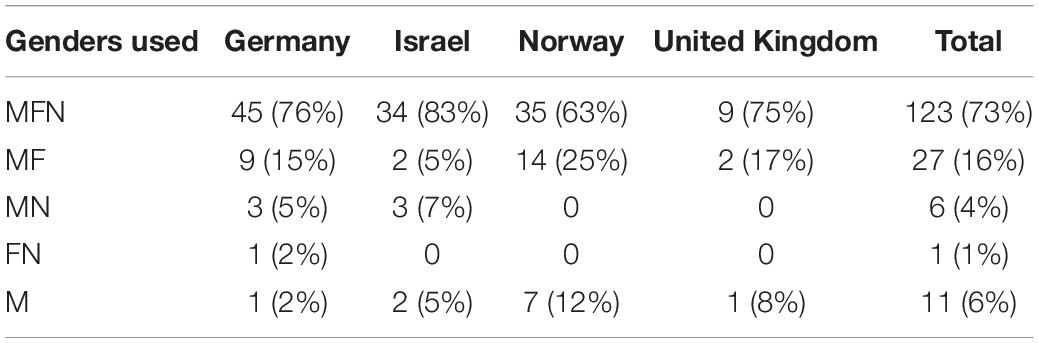

Individual Profiles, Nonce Words

The patterns observed in the nonce words experiment resemble the ones observed for the real words task, but with a higher overall proportion of masculine. This is expected given our assumption that many feminine and neuter responses in the real word task should be attributed to rote-based lexical learning and not to cue-driven assignment. Nevertheless, the role of morphophonological cues was still significant, as evident from the fact that the majority of bilingual children in our sample (123/168, 74%) used all three genders in their responses, cf. Table 4. No children exhibited F-only and N-only patterns. At the same time, we found that 11 children in our sample used only masculine in their responses, 27 children used feminine and masculine only, and six children used masculine and neuter only.

M-Only Pattern

The core of the M-only group consists of the same children that used exclusively masculine in the real word task, with the exclusion of the Latvian participant who did not participate in the nonce word task, and the addition of two participants from Israel. One of these latter participants was in the MN group in the real word task (however, she only used neuter once and masculine in all other trials), while the other one used masculine and feminine in the real word task, but only masculine in the nonce word task.

MN Pattern

The majority of children with this pattern used neuter only once (three from Germany and one from Israel). We can classify such use of neuter as occasional and marginal. However, there were two children (both from Israel) who used neuter 60 and 76% of the time, respectively. One of these children used neuter only in the vowel-final conditions (F, FN, and N cues) and masculine in the consonant-final conditions (FM and M cues). The second child used neuter in all conditions, but additionally used masculine (at approximately the same rate as neuter) in M-C and N-o conditions. Interestingly, these two children did not overuse neuter in the real word task: they correctly used neuter in the two N conditions (with 100% accuracy), but not with feminine or masculine nouns.

MF Pattern

As in the real word task, the MF group contains at least two subgroups: productive and occasional users of feminine. Thus, out of the 27 children in this group, 12 used feminine only once or twice and masculine in all other trials (the occasional feminine users). The feminine responses were produced exclusively in feminine-compatible conditions (F, FN, and FM cues) and never in M and N conditions. This indicates that even children who used feminine less than 10% of the time in their responses were sensitive to the cues and only produced feminine in conditions where the nonce word had a feminine-compatible cue. The second group of children (n = 15), the “productive feminine users,” also used feminine predominantly in the feminine-compatible conditions – which makes up 80% of all of their feminine responses. At the same time, they almost never used feminine with nonce words ending in a non-palatalized consonant (M-C cue). In the N condition (nonce words in -o), eight children used (almost) exclusively masculine, four children used (almost) exclusively feminine, and three children used masculine and feminine interchangeably. This distribution is similar to the one observed for the FM pattern in the real word task. At the same time, we can conclude that even children who have not yet fully developed a three-gender system make use of the formal gender cues, and their behavior in the nonce word task is not random, but driven by the morphophonological gender cues.

Discussion

Effects of Language-Internal Factors, Cross-Linguistic Effects (RQ1)

In the present study we compared gender assignment in Russian across five different national contexts: Latvia, Germany, Israel, Norway, and the United Kingdom. Our bilinguals acquire a semi-transparent gender system of Russian (where the different noun endings are strongly associated with specific genders) simultaneously with a gender system of Latvian and Hebrew (most transparent), German (less transparent), and Norwegian (non-transparent) as well as English, a language without grammatical gender. If CLI takes place in the bilingual acquisition of grammatical gender in HR, we predicted this influence to be indirect and manifest itself in the form of acceleration or delay.

Specifically, we predicted that the properties of the gender systems in contact may strengthen or weaken the bilinguals’ sensitivity to some of the six morphophonological cues in Russian. In the real-word task, we find that gender assignment is at ceiling on the M-C cue and that it is near-target-like on the M-pal cue (Figure 1). This confirms our prediction that the cues for masculine are not good indicators of crosslinguistic effects due to the high frequency, predictability, and transparency of these cues in Russian. In other words, formal characteristics of these cues override potential CLI. The same seems to be true for the F-a cue, which is also highly frequent and transparent in Russian. According to Figure 1, all participant groups display approximately 90% accuracy with feminines ending in -a. These results suggest that gender assignment with the M-C, M-pal, and F-a nouns in HR is easy for bilinguals regardless of whether their two languages share the respective gender cues or not.

Similarly, in the nonce-word task, the majority languages lacking transparency or grammatical gender do not seem to have a negative effect on the bilinguals’ sensitivity to the M-C, M-pal, and F-a cues, since all participant groups show a clear preference for masculine and feminine in the respective conditions (Figure 2). However, the children from all countries experience considerable difficulties assigning gender with F-pal, N-o and N-/ǝ/ nouns (Figure 1). This striking similarity may also speak against CLI. For the two N conditions we predicted acceleration from German and Norwegian that have neuter gender in contrast to Latvian and Hebrew as well as English. Nevertheless, no significant acceleration is found in the Russian-German group, and the Russian-Norwegian group score among the lowest. Interestingly, the Russian-English bilinguals score among the highest in the N conditions as well as in the F-pal condition, where the groups from Norway, Israel, and Latvia score among lowest.

The results from both the real-word and the nonce-word tasks in the present study suggest that the absence of grammatical gender in the majority language is not a disadvantage. We can also conclude that the acquisition of neuter, which has been shown to be highly problematic in HR, does not seem to be affected by the presence or absence of this gender category in the other language of a bilingual child. This is in contrast to Egger et al. (2018) observation that early and increased awareness of neuter in Greek can facilitate the discovery of neuter in Dutch, and it runs counter to Eichler et al. (2013), who claimed that neuter was affected negatively in bilingual children’s German because they were acquiring a two-way (M, F) system simultaneously. It should be noted, though, that the lack of acceleration from German or Norwegian in our study may be attributed to the fact that neuter nouns in these languages are the least frequent gender and are also late acquired (Rodina and Westergaard, 2015; Kupisch et al., unpublished). To conclude, our results show that bilingual sensitivity to gender cues in HR is not affected (positively or negatively) by simultaneous acquisition of another gender or non-gender language. The gender systems exhibiting high transparency and predictability (like Latvian and Hebrew) do not seem to lead to an increased awareness of the Russian gender system. And the systems exhibiting reduced transparency and predictability (like German and Norwegian) do not cause delays. We would argue that the reason for this is that gender acquisition in HR is largely predicted by the gender cues available in Russian and the extra-linguistic factors discussed below.

Effects of Language-External Factors (RQ2 and RQ3)

In what follows we would like to discuss how gender acquisition (especially the difficulties that HL speakers experience) is affected by the amount of exposure to the HR in the home and outside. The difficulties that we identified in the real-word task occur with F-pal, N-o, and N-/ǝ/ cues. They are present to a similar degree in all participant groups and are not unexpected, as they occur with the noun classes that are infrequent and/or have ambiguous gender cues. Their acquisition may thus require more extensive exposure than the acquisition of nouns with frequent and transparent gender cues. This is also confirmed by the results in nonce-word task. In line with previous research, our analysis reveals that language exposure in the home defined in terms of family type (HR family vs. mixed family) is one of the main predictors of accuracy in gender assignment. The novel line of research taken in this paper focuses on HL use outside the home and shows that gender assignment is also shaped by the size of the HR community and especially by current exposure to HR instruction. Overall, older children, children from communities with higher proportion of Russian speakers, as well as children receiving more exposure to HR instruction, acquire gender more easily than the children from communities with a lower percentage of Russian speakers and less exposure to HR instruction.

The examination of the children’s individual profiles reveals that the masculine-feminine-neuter distinction is present in the majority of bilinguals across all countries (Tables 3, 4). There is also a small number of children who have difficulties acquiring neuter or grammatical gender altogether. Both patterns were previously attested in HR speakers in the United States and Norway (Polinsky, 2008; Rodina and Westergaard, 2017; Mitrofanova et al., 2018). Our results indicate that the probability of developing a reduced gender system of masculine and feminine or only masculine is predicted by family type, age at kindergarten start, and current exposure to HR instruction. In other words, the less input the children have had in Russian (younger children, children from mixed families, and those who started kindergarten early), the more likely they are to develop a reduced gender system in Russian. Thus, it is clear that HL experience inside and outside the home is beneficial for HL acquisition.

Pedagogical Implications

For HL speakers (HSs) grammatical gender is part of an implicit mental representation. In other words, gender acquisition is a developmental process during which HSs (just like monolinguals) build implicit knowledge from mere exposure, without any explicit grammatical knowledge of gender assignment to Russian nouns. The acquisition of this implicit knowledge (acquired in the absence of instruction) can sometimes be challenging for HSs due to the lack of sufficient exposure. Russian HSs may experience delays in the acquisition of grammatical gender, especially with neuter nouns and feminines ending in a palatal consonant. A more disruptive scenario is when the gender system is restructured and a new one develops, which is either reduced to two genders (masculine-feminine) or just one (masculine, virtually no) gender (Polinsky, 2008; Rodina and Westergaard, 2017). Language acquisition research demonstrates that reduced input is the major source of difficulty in gender acquisition, due to the ambiguity and low frequency of certain gender cues. Therefore, an important question is whether we can find strategies that would encourage and support cue sensitivity in bilingual learners.

It is highly unlikely that child bilinguals would benefit from explanations of explicit rules for gender assignment, especially when it comes to morphophonological and syntactic rules. In fact, L2 research shows that even older cognitively mature learners are not able to take advantage of explicit descriptions of grammatical gender rules (Corder, 1973; Tucker et al., 1977). On the other hand, input processing strategies that aim at altering and/or improving learners’ processing of input data, show promise (Culman et al., 2009). These strategies rely on processing instruction activities that push learners to recognize the grammar in the input, ensuring grammatical intake for acquisition. The key feature of processing instruction is structured input, i.e., input that is manipulated in order to force learners to notice and process grammatical forms. In the context of grammatical gender, processing instruction may push learners to rely on more appropriate cues. We need to look for strategies that would help learners notice morphophonological gender cues. For example, the adjective-noun pair strategy investigated in Ranjan (2013) was found to facilitate grammatical gender learning in heritage and L2 learners of Hindi/Urdu. In his pilot study Ranjan presented the experimental group of Hindi/Urdu learners with adjective-noun pairs where adjectives were unambiguously marked for masculine or feminine and nouns had no explicit masculine or feminine endings. In the immediate post-test, a grammaticality judgment task, this group outperformed the control group who prior to the experiment leant gender through the list of nouns not coupled with adjectives.

To encourage and support gender cue sensitivity in HR learners, we propose that learners are provided with increased exposure to unambiguous noun forms, especially with the neuters ending in a stressed -o, e.g., okno “window,” which can then be contrasted with the unambiguous feminines, like lisa “fox.” It is also crucial that nouns with ambiguous cues are paired with agreement targets which have unambiguous gender forms, e.g., moje/takoje/bol’šoje/goluboe/zolotoe myl-/ǝ/ ‘my/such/big/blue/golden soap’. Learners may also benefit from increased exposure to masculine and feminine nouns ending in a palatal, which present another source of ambiguity. This may be in the form of contrastive use of such masculine and feminine nouns paired with agreement. Older learners may also benefit from knowledge about the ambiguities of the gender system in Russian and the acquisition of literacy. Whether these strategies can lead to increased awareness of the morphophonological gender cues and facilitate the acquisition of gender assignment in Russian is subject to future research.

Conclusion

This paper has investigated the acquisition of grammatical gender in Russian as a HL in five different countries – Norway, Germany, Latvia, Israel and the United Kingdom. We have focused on both language-internal and language-external factors, the former generally referring to CLI between the heritage and majority languages and the latter to background factors investigating the role of exposure to HR in the home and outside. Our background factors included chronological age, family type (Russian only or mixed input in the home), current exposure to HR instruction, size of the HR community in the country, main language of instruction, age of onset for majority language, and age at kindergarten start. The five countries differ considerably with respect to these factors, ranging from small communities in Norway to robust communities in Latvia, where it is questionable whether Russian can even be considered a HL. The five majority languages also display interesting similarities and differences with respect to the linguistic phenomenon at hand, from having no gender at all (English) to being similar to Russian in having a three-gender system (German) or having opaque or largely transparent systems for gender assignment (Norwegian vs. Latvian and Hebrew). We carried out two elicitation experiments on altogether 209 HR children (age range 3 to 10), using both real and nonce words. The experiments focused on the three transparent morphophonological gender assignment rules in Russian (ending in a consonant for masculine, -a for feminine and -o for neuter), as well as two ambiguous cues [ending in a palatalized consonant (masculine or feminine) or an unstressed vowel (feminine or neuter)]. The children in all countries are generally sensitive to the gender cues, but display certain problems with feminine palatalized and neuter gender. We find no significant differences between the various countries in this respect, indicating that there is no CLI in this grammar domain. This is presumably due to the fact that gender acquisition in HR is largely predicted by the gender cues available in the target language. Another reason could be that many of the children in our samples have a higher proficiency in Russian than in the majority language, e.g., the children in Germany (Kupisch et al., unpublished). On the other hand, some of the external factors are shown to have major effects: While the size of the Russian-speaking community is a significant factor in the real-word task and age of starting kindergarten is significant for the nonce-word task, the following three factors are significant predictors of accuracy on both tasks: family type, age, and current exposure to HR instruction. Thus, it is clear that literacy in Russian is a major factor for the acquisition of grammatical gender, and we make some suggestions for how the acquisition of this complex linguistic property could be facilitated through instruction and enhanced input.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the project was registered and approved by the Norwegian Social Science Data Service (NSD, http://www.nsd.uib.no). Data collection was conducted in accordance with NSD’s ethical principles. Written informed consent was obtained from parents of all the participants prior to testing. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

All authors were responsible for the conception of the work and experimental design. NMe, NMi, YR, and OU carried out the collection of data with bilingual participants. NMe and NMi were responsible for data analysis and interpretation of the results. All authors shared responsibility for drafting of the work and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding

This research was partly supported by a grant from the Research Council of Norway for the project MiMS (Micro-variation in Multilingual Acquisition & Attrition Situations), project number 250857 as well as by a grant from the Norwegian Financial Mechanism 2009–2014 for Latvian-Norwegian research collaboration, project contract number NFI/R/2014/053.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.00020/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ 1In many studies on the acquisition of gender, a distinction is made between gender assignment and gender agreement, the latter referring to agreement between different targets and the former to the gender assigned to the noun itself. In our study, the focus is on gender assignment [see more on this distinction in acquisition in Rodina and Westergaard (2017) and Stöhr et al. (2012)].

- ^ Some varieties of Norwegian still have a traditional three-gender system of masculine, feminine, and neuter, but many dialects have lost the feminine, including the dialects where data collection took place (Oslo and Tromsø).

- ^ The distinction between phonological or morphological cues is not clear-cut, both refer to the shape of the end of the noun, but phonological cue often refers to a single form of the noun, while morphological cue, refers to more than one form, e.g., noun’s declension type (Corbett, 1991).

- ^ It should be noted that the proportion of Russian speakers living in different cities varies within each country. For example, the size of the Russian speaking community in Berlin is larger than in Singen. However, due to the lack of reliable statistics and because making this distinction would result in small groups sizes of participants (especially in the United Kingdom), we were unable to address these population differences in our analysis.

References

Anderson, R. T. (2012). “First language loss in Spanish-speaking children: patterns of loss and implications for clinical practice,” in Bilingual Language Development & Disorders, ed. B. A. Goldstein (Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co Inc.), 193–212.

Armon-Lotem, S., and Meir, N. (2019). “The nature of exposure and input in early bilingualism,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Bilingualism, eds A. De Houwer, and L. Ortega (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 193–212.