- School of English Education, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, China

Practicum poses great challenges for pre-service teachers who learn to assess because their conceptions of assessment (CoAs) may undergo dramatic changes. This multiple-case study reports on how three pre-service teachers' CoA changed over practicum at a primary school in China. Findings show that pre-service teachers' CoAs have experienced a rapid change from a superficial perception of assessment for academic achievement and moral character development to a more comprehensive understanding of varied assessment purposes, constructs in assessment criteria, feedback, fairness in classroom assessment, and students' involvement in and engagement with assessment. A range of factors are found to have exerted varying degrees of influence on these conception changes, such as personal factor (i.e., agency in assessment), experiential factors [i.e., school-based assessment practices, interactions with students, and (anti-)apprenticeship of observation about assessment], and contextual factors (i.e., mentoring, classroom reality, school assessment culture, and national assessment policy). These findings are discussed in terms of how these changes are diverse but limited, as well as how the mediating factors have exerted differentiated influences in positive or negative ways. This paper concludes with implications for research on teachers' CoAs and professional development for assessment literacy.

Introduction

Against the background of the increasing accountability of student learning and the rising importance of assessment for learning across school levels and contexts, there is a pressing need for preparing assessment-literate teachers (DeLuca et al., 2016; Popham, 2018). In China, teachers are placed within tensions between a strong testing tradition that used high-stakes exams for selection and ranking purposes (Carless, 2011; Chen and Brown, 2018) and liberal educational reforms featuring assessment for learning [Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (MOE), 2011, 2017]. Such tensions indicate that preparing assessment-literate teachers is by no means an easy task. In teacher education programs, pre-service teachers are expected to learn to assess through courses and practicum. Specifically, they need to expand assessment knowledge, reflect upon their conception of assessments (CoAs), enact their assessment practices, and bridge the gap between theory and practice of assessment (Cheng et al., 2010; Hill and Eyers, 2016). Thus, learning to assess is one of the most important yet challenging tasks for pre-service teachers.

During the practicum, “one of the most important aspects of a teacher education program” (Farrell, 2008, p. 226), pre-service teachers' conceptions of teaching and learning are subject to changes through various field experiences (Lawson et al., 2015). Various activities and people are also found to have played a part in this changing process, including mentoring from university professors and associate teachers in the field schools and pre-service teachers' classroom observations and teaching practices (Anderson and Stillman, 2013; Izadinia, 2013, 2016; Lawson et al., 2015). Research on how pre-service teachers' CoA change during practicum is regrettably scarce.

In teacher education programs, pre-service teachers' CoAs are found to have changed after they start learning to assess (Smith et al., 2014). Importantly, how teachers conceptualize assessment is found to influence their uptake of assessment knowledge and implementation of assessment practices (Brookhart, 2011; Deneen and Boud, 2014; Barnes et al., 2015; Fulmer et al., 2015). Despite growing recognition of the importance and dynamics of teachers' CoA, the processes and patterns of pre-service teachers' CoA change during practicum have not been adequately explored. To address this gap, this study aims to explore pre-service teachers' CoA changes over practicum and the influential factors of this changing process by drawing on three Chinese prospective teachers' cases. Specifically, the focus on the changing processes of these teachers' CoA can generate useful insights into the complexities of pre-service teachers' assessment literacy development. Such insights can provide implications for teacher education programs in terms of how to maximize the outcome of practicum in promoting teacher assessment literacy.

Literature Review

Understanding of Pre-service Teachers' CoA

In this paper, CoA refers to “a teacher's understanding of the nature and purpose of how students' learning is examined, tested, evaluated, or assessed” (Brown and Gao, 2015, p. 4). Given that teachers' CoA functions as an interpretive and guiding framework to take in assessment knowledge and as a potent mediator of assessment planning and practice within contextual tensions (Fulmer et al., 2015; Deneen and Brown, 2016; Xu and Brown, 2016), continually expanding and deepening CoA is an essential prerequisite for being an assessment-literate teacher. Compared with the bulk of research on in-service teachers' CoA, studies on pre-service teachers' CoA mainly converge on three themes.

The first theme mainly focused on teachers' conceptions of assessment (CoA) purposes (e.g., Winterbottom et al., 2008; Deluca and Klinger, 2010; Brown and Remesal, 2012; Chen and Brown, 2013; Deluca et al., 2013a). For instance, using the Teachers' Conceptions of Assessment (TCoA) inventory for a cross-cultural comparison between pre-service teachers in New Zealand and in Spain, Brown and Remesal (2012) established a model for pre-service teachers' CoA, which comprises five different assessment purposes. Given the context-dependent nature of CoA, the results of this study cannot be generalized to other contexts (e.g., China).

The second theme mainly used surveys to investigate what CoAs are like at a certain point within the teacher education programs (see a review by Bonner, 2016). For example, Chen and Brown (2013) found that Chinese pre-service teachers in their first 3 years of teacher education conceived assessment purposes as four intercorrelated factors, that is, diagnose and formative, irrelevant, control, and life character. Although these studies have generated useful insights into the complexities of pre-service teachers' CoA in China, they did not explore the nuances of pre-service teachers' CoA changes as part of their professional development.

The third theme mainly explored how CoA changes are related to effectiveness of explicit assessment training in teacher education programs (e.g., Chen, 2005; Deluca and Klinger, 2010), based on which to identify effective pedagogical strategies for facilitating pre-service teachers' conceptual changes about assessment (Deluca et al., 2013b). Regrettably, little is known about the role of practicum in pre-service teachers' CoA.

Context-Dependent and Dynamic Nature of Pre-service Teachers' CoA

What pre-service teachers' CoAs are like is a recurring theme of research in this line. An analysis of prior research generates two features of pre-service teachers' CoA. First, it is context dependent. Pre-service teachers' CoAs vary not only across different cultural and policy contexts (e.g., New Zealand vs. Spain) (Brown and Remesal, 2012) but also across putatively similar policy contexts (e.g., China vs. Egypt) (Chen and Brown, 2013; Gebril and Brown, 2014) as well as different levels of schooling in the same context (e.g., primary vs. secondary schools in Spain) (Remesal, 2007). For instance, while pre-service teachers in New Zealand and Spain regard the primary assessment purpose as improving both teaching and learning (Brown and Remesal, 2012), Chinese pre-service teachers mostly endorse the control-oriented purpose of assessment (i.e., using assessment to control teachers' work and students' daily behavior) (Chen and Brown, 2013). The differences in pre-service teachers' CoA can be attributed to different cultural norms, assessment policy priorities, and assessment courses offered (Brown and Remesal, 2012).

Second, it is dynamic, constantly changing along with teachers' learning experience (Winterbottom et al., 2008; Brown, 2011; Brown and Remesal, 2012). To be specific, their CoAs arise from their experiences of being assessed as learners and then change along the process of teacher education (Hill and Eyers, 2016). Particularly, their experiences of apprenticeship of observation (i.e., learning about teaching subconsciously through observing their own teachers' teaching) (Lortie, 1975) largely influence pre-service teachers' initial conceptions and account for their teaching practice (Knapp, 2012; Boyd et al., 2013). Negative experiences of apprenticeship of observation can serve as “anti-apprenticeship of observation” (Moodie, 2016, p. 29), as pre-service teachers can learn a lesson from their teachers about what not to do as teachers. Besides, as a result of teacher education, pre-service teachers' CoA shifted from limited understanding about summative assessment (Graham, 2005; Brown, 2011; Smith et al., 2014) toward an increased recognition of formative assessment (Deluca and Klinger, 2010; Deluca et al., 2013a; Smith et al., 2014).

To understand the trajectory of pre-service teachers' CoA change during practicum, we extend our review to research on their general conception change in this period. Pre-service teachers' various conception changes about teaching and learning during the practicum (see a review by Lawson et al., 2015) can be attributed to their interactions with university supervisors, peer student teachers, students, associate teachers, and other teachers from the field schools (Stuart and Thurlow, 2000; Ng et al., 2010). The interactions vary in forms, including daily communication, classroom observation, and regular meetings. Classroom teaching can also exert an influence on pre-service teachers' conception change (Borg, 1999) through both their critical reflection (Farrell, 2007) and their engagement in lesson planning activities (Stuart and Thurlow, 2000).

In addition to these external factors, teacher agency is found to play an essential role in conception change (Barcelos and Kalaja, 2011). Agency, “the capacity of people to act purposefully and reflectively on their world” (Rogers and Wetzel, 2013, p. 63), is achieved and mediated by social interactions within contextual conditions (Priestley et al., 2012). During the practicum, pre-service teachers' conception changes are found to benefit from their agentic engagement with others, critical thinking, and reflection (Yuan and Lee, 2014). The exercise of teacher agency on their conception change is also found to be constrained by various external factors, such as prescribed syllabus, entrenched classroom practices, and insufficient mentoring (Tang et al., 2012; Yuan and Lee, 2014; Yuan, 2016).

To recap, although these studies have identified sociocultural factors that contribute to pre-service teachers' general conception change during practicum, whether the influence of these factors can be generalized to pre-service teachers' CoA change has remained unclear. Given that pre-service teachers' CoA changes during practicum are underexplored, the present study intends to address this research gap by answering the following two questions:

RQ1: What are the CoAs among pre-service teachers before and after practicum?

RQ2: What are the influential factors to these changes?

Methodology

Research Context and Participants

This study was conducted with participants from a 4-year English teacher education program at a university in China. Within the teacher education curriculum, two courses related to assessment were offered to pre-service teachers, namely, Language Testing and Evaluation and English Language Teaching [see more basic information in Appendix A (Supplementary Material)]. In the fourth year, pre-service teachers were assigned to different schools for a 6-week practicum. Each practicum team was supervised by one university professor and their respective associate teachers in the field school. The associate teachers assumed the primary responsibility for supporting and evaluating pre-service teacher's performance during practicum, whereas the university professor regularly visited the field school to observe teaching and give advice.

Participants in this study were from the same practicum team in a primary school located in Guangzhou, China. Responding to the quality education policy [(Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (MOE), 2010)], the constructs in evaluation criteria for the quality of primary education have changed from students' academic examination results and enrollment quotas to students' moral character1 development, academic achievement, physical and mental health, interest and specialty, and academic workload [Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (MOE), 2013]. Against the background of China's long history of high-stakes examinations and contemporary policy priority in formative assessment (Xiao, 2017), primary schools are expected to effectively combine formative and summative assessments. According to English Curriculum Standards [Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (MOE), 2011], the priority of formative assessment is to encourage students' active participation in learning and to enhance students' self-confidence, while summative assessment is oriented to testing students' integrated language skills and ability to use language.

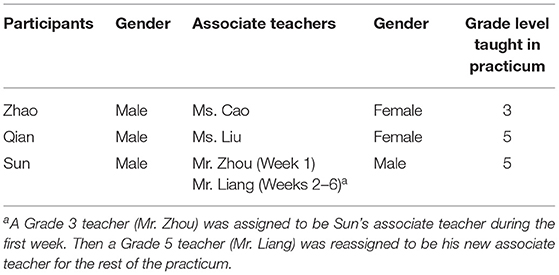

Altogether six pre-service teachers voluntarily participated in this study. During the practicum, they mainly observed the teaching of their associate teachers and taught a few lessons when ready. According to the schedule, the pre-service teachers did not engage in preparing students for high-stakes examinations such as the final exam. During our visits to the field school, we observed lessons of all six teachers, attended their group meetings, talked with them, and interviewed them, which ensured the collection of complete sets of data and a thorough understanding of their practicum experience. Due to space limitations, however, this study reports cases of three focal male participants, namely, Zhao, Qian, and Sun (all pseudonyms). The main reason for this selection is that the data from these three cases are the richest and the most representative among all six cases, which can adequately address the research questions. Demographic information about the three pre-service teachers and their associate teachers is provided in Table 1. Before the study commenced, ethical approval was obtained from the university, and written consent forms were obtained from the field school and the three participants.

Data Collection and Analysis

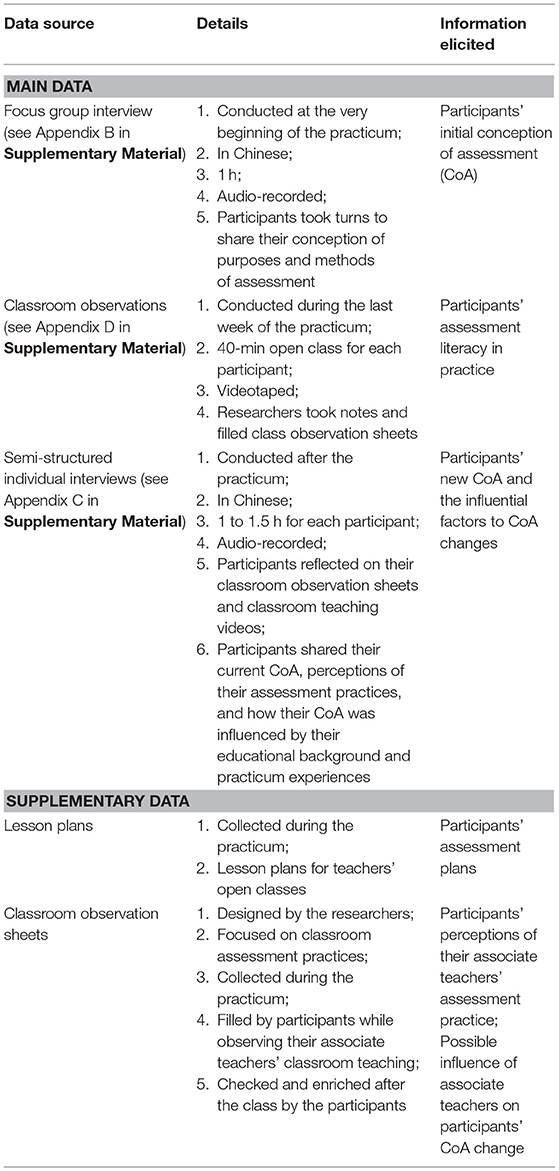

Table 2 specifies the data source, collection procedures, and information elicited from each set of data. At the beginning of the practicum, a focus group interview was conducted to understand participants' initial CoA. As an informal but structured group discussion, the focus group interview is more suitable for pre-service teachers who had only tacit knowledge about an insensitive but rarely discussed topic. After the practicum, individual interviews were conducted to explore their new CoAs and their influential factors. For participants who have accumulated enough experience of assessment during practicum, individual interviews would provide more opportunities for sharing their personal experiences and thoughts in detail without interruptions or intervention (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015; Salmons, 2015). It is also important to clarify that the supplementary data (i.e., classroom observations and documents) were collected not only to situate the present study in the context of CoA and assessment practice but also to tailor the individual interview protocol to participants [see data references in Appendix C (Supplementary Material)]. The triangulation of multiple data sources can warrant the reliability of the study and allow for a holistic and cohesive interpretation of participants' conceptions and practice (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015).

The analyses of data followed Merriam's (1998) case study analysis and Merriam and Tisdell's (2015) coding strategies. There were two stages of analysis: within-case analysis and cross-case analysis. For within-case analysis, we considered the cases individually, focusing specifically on their CoA before and after the practicum and the influential factors. During this stage, both open coding and axial coding were used for each set of data.

Classroom Observations and Documents

The analysis of the two sets of data followed five steps. First, we watched the videotapes, summarized the classroom activities, and enriched the class observation sheets with the aid of the researchers' field notes. Second, the summaries were scrutinized, from which assessment activities (e.g., feedback delivery) were extracted from the videotapes and then fully transcribed. Third, these transcripts, the original videotapes, and the classroom observation sheets were double-checked to avoid any possible loss of information. Fourth, open coding was employed to investigate the participants' assessment literacy enacted in practice. We then used axial coding to group the codes into categories (while also being open to other emerging/recurrent categories). Participants were invited to check and comment on these codes, categories, and quotes before the individual interviews. The refined categories include (a) course materials used in assessment activities; (b) features and purposes of assessment activities; (c) teacher questioning; (d) feedback delivery; and (e) students' participation and response. Last, this set of data was compared with the participants' lesson plans to identify whether there was any discrepancy between the pre-service teachers' plans and actual practices of assessment.

Focus Group and Individual Interviews

The audio recordings of these interviews were carefully transcribed verbatim in Chinese by the second author and then sent back to the participants for member checking. Then the modified transcripts were translated into English by the second author and later sent to the first author to check for any possible loss of meaning in the translation process.

The category construction process started with open coding, which was independently conducted by the two researchers. The unit of analysis was a sentence or group of sentences that informed a single meaning or message. Only those segments of the data identified as relevant to teachers' CoA or influential factors to CoA changes were considered in this process. Next, axial coding was employed to group the codes that emerged in this process. During the process of naming and categorizing codes, we referred to the prior literature and remained open to new codes and categories emerging from the data [see sample coding in Appendix E (Supplementary Material)]. Participants were also invited to conduct member checking. All coder disagreements were reconciled through discussion and negotiation until a consensus was reached. Six categories related to CoA changes emerged, and after being compared with prior studies, they were named as followed: (a) assessment purposes (Brown and Gao, 2015); (b) constructs in assessment criteria (Sun and Cheng, 2014); (c) feedback (Hattie and Timperley, 2007); (d) fairness in classroom assessment (Tierney, 2014); (e) student involvement in assessment (Xu and Brown, 2016); and (f) student engagement with assessment (Xu and Brown, 2016). Additionally, eight categories related to influential factors emerged, namely, (a) mentoring (Yuan and Lee, 2014); (b) classroom reality (Farrell, 2012); (c) school assessment culture (Myyry et al., 2019); (d) national assessment policy (Brown et al., 2011); (e) (anti-)apprenticeship of observation about assessment (Lortie, 1975; Moodie, 2016); (f) interaction with students (Ng et al., 2010); (g) school-based assessment practice (Zhang et al., 2018); and (h) teacher agency in assessment (Rogers and Wetzel, 2013). We then summarized all the categories from both the focus group interview and the individual interviews to analyze changes of each participant's CoA over the practicum.

Finally, we created case profiles for each participant by gathering all the coded data and corresponding categories. We then conducted a cross-case analysis to identify any similarities and differences within each of the categories of all the participants. Cross-case comparison was conducted to gain microlevel insights into pre-service teachers' CoA changing patterns and their influential factors.

Analytical results and further discussion are presented in the following sections. In the finding section, interview transcripts as the main data to trace CoA changes are verbatim quoted, whereas the observational transcripts and documents as the supplementary data are mainly knitted in our narratives (see data references). Data references2 are enclosed in square brackets to help differentiate them.

Findings

Findings reveal that all three pre-service teachers' CoAs experienced great changes during the practicum. In what follows, we will portray each case one after another, as individual variations of CoA changes are our salient findings. By the end of this section, we summarize the case evidence by generating the similarities among the cases for comparison.

Case 1—Zhao: A Low Starting Point and Limited Changes of CoA

Zhao was an underachieving student without much enthusiasm for teaching. His CoA changes were featured with a low starting point and limited development after the practicum. At the very beginning of the practicum, he had a shallow understanding of assessment:

I don't know assessment exactly. I only think of the University Comprehensive Evaluation3 that consists of test scores, conduct and discipline, extracurricular activities, volunteer activities, and so on. I mean it includes assessment of students' moral character (Zhao [FGI: LL64–69]).

Zhao's brief answer in this excerpt suggests that he was not yet ready to explicitly state his CoA. He seemed to be confused about what to include as assessment criteria. He intuitively made connections between his own assessment experience in the university and thus listed students' moral character as part of his understanding of legitimate constructs in assessment criteria.

Luckily, the practicum provided him with ample opportunities for reflecting on his CoA. One of the most frequently engaged assessment activities was marking student assignments. Taking up such a basic duty oriented him to think as an assessor:

I marked dictation sheets and exercise books every day. I get to know their mastery of certain knowledge dimensions … And I can judge from their degrees of completion whether students have a serious attitude toward learning (Zhao [II: LL53–62]).

Marking homework prompted Zhao to assess his students in an overall way. This excerpt suggests that the key information that Zhao had gleaned from students' homework included not only their academic achievement in comparison with the learning goals but also their attitudes toward learning—an important “academic enabler” (McMillan, 2001, p. 25) that can facilitate students' academic achievement. Zhao also realized that “direct observation” (DiPerna, 2006, p. 13) of student assignments can be an efficient way of assessing students' learning attitudes.

Another proof of his growing awareness of the assessor identity can be found in his newly developed CoA purposes:

For teachers, assessment helps them monitor student learning and locate deficiencies, which benefits teachers in adjusting teaching plans and facilitating teaching (Zhao [II: LL194–198]).

Obviously, the teaching-oriented purpose of assessment, that is, to diagnose and improve teaching efficiency, was a new addition to Zhao's CoA. The practicum seems to be a critical point from which Zhao started to consider assessment from a teacher's perspective and developed a more realistic understanding of assessment in the school context through observing his associate teacher's teaching:

There were more than 40 students in one class. While conducting classroom activities, students were likely to distract, leaving the class in disorder. At that time, my associate teacher would suddenly stop talking for a while. Then he praised or criticized a student, made comments on the discipline, or gave students instructions to keep quiet (Zhao [II: LL7–15]) … The teachers of that school scored students in groups based on their class participation, marked with strokes of the Chinese character “ (zheng)” on the blackboard, and gave rewards at the end of a semester. It helped enhance students' engagement and motivation (Zhao [II: LL109–116]).

(zheng)” on the blackboard, and gave rewards at the end of a semester. It helped enhance students' engagement and motivation (Zhao [II: LL109–116]).

If we compare Ms. Cao's (Zhao's associate teacher's) routine assessment practice (i.e., using feedback or instructions to maintain classroom discipline) with Zhao's newly developed conception, some connections can be found. In Zhao's newly developed conception, he perceived the combination of “direct observation” and brief “rating scales” (DiPerna, 2006, p. 13) as a common way of assessing student active participation in classroom instruction, another primary “academic enabler” (McMillan, 2001, p. 25). He also regarded tangible rewards as a “necessary” and “effective” reinforcement strategy to “enhance student engagement and learning motivation” (Zhao [II: LL17–20]).

Zhao's enhanced identity as a teacher assessor helped him not only to think critically of Ms. Cao's practice but also to reflect on his awful assessment experiences of being inappropriately assessed:

I saw the teacher criticize some naughty students in the class. It is not appropriate. I used to do a 20-min presentation which had no direct relation with pronunciation. However, my teacher commented on my pronunciation for half an hour just because I had some mispronunciations. I don't think it is appropriate. It would be better to discuss such problems in private and give negative feedback in written form (Zhao [II: LL131–140]).

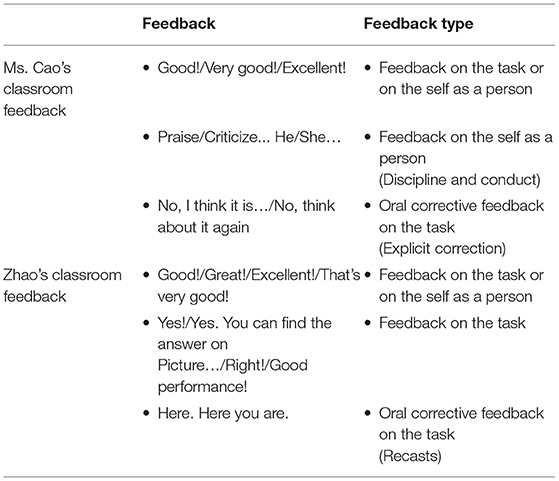

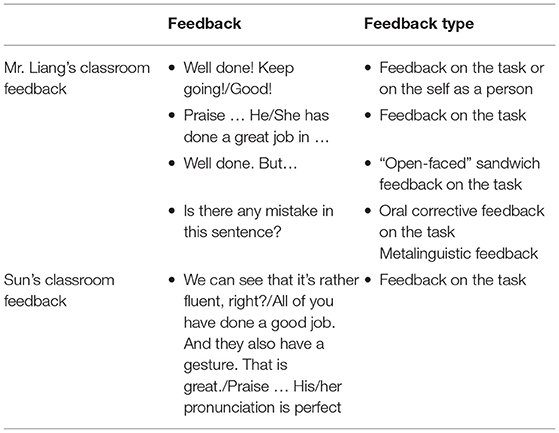

This reflection could be seen as Zhao's “anti-apprenticeship of observation” (Moodie, 2016, p. 29) in assessment. His university instructor had set a bad example in assessment that Zhao wanted to stay away. Although his instructor's assessment was unfair to Zhao, it was fortunate in the sense that this critical incident stimulated him to reshape his beliefs about alignment between feedback and assessment purpose, as well as about how feedback can be used in protecting students' self-esteem and motivation. Such reshaped beliefs were then fully enacted in his assessment practice in the practicum, particularly when he eventually got the chance to teach in the sixth week. Table 3 summarizes Zhao's feedback practices in the open class that we observed, as well as Ms. Cao's feedback practice that was recorded by Zhao.

A close reading of Table 3 reveals two interesting findings of Zhao's conception of feedback. First, his belief of feedback is consistent with his practice, although the effectiveness of his feedback practice is questionable. Given that he believed in the role of feedback in protecting students' self-esteem and motivation, he tended to deliver general and positive oral feedback (e.g., “Good!” “Great!” and “Excellent!”) (Zhao [CO]). However, such feedback failed in eliciting thinking, reflection or follow-up action (Carless, 2019) because it contained neither task-related information (e.g., correctness, neatness, and behavior) nor personal information (e.g., effort, engagement, and feelings of efficacy) (Hattie and Timperley, 2007).

Second, there is a misalignment between Zhao's and Ms. Cao's conceptions of feedback, which led to Zhao's calibrated feedback practice. While Ms. Cao believed that explicit correction and feedback on students' discipline and conduct can be used for classroom management, Zhao held the belief that feedback needs to serve its purposes of facilitating learning and protecting student self-esteem and motivation. Hence, instead of following Ms. Cao's feedback practice, Zhao gave oral corrective feedback through recasts, which are less effective in facilitating students' language learning than explicit correction (Lyster and Ranta, 1997; Yang, 2016) but could serve the purpose of protecting student self-esteem and motivation.

In addition to Ms. Cao's influence, Zhao's own assessment practice is found to exert a significant influence on his CoA changes in many dimensions, as the following reflection shows:

In my class, some students were unsatisfied because they were not invited to answer questions. Such a situation would not exist in my associate teacher's class. It would be better to give every student, at least every group, a chance to answer questions. Besides, the questions should be explicit, logical, otherwise, or students will not understand what they are expected to do. I think my assessment design was not good, because the questions were not logically linked to each other to achieve coherence (Zhao [II: LL147–153]).

Clearly, Zhao's reflective learning about the fairness in classroom assessment mainly derived from his practice in the open class and his observation of Ms. Cao's teaching. His conceptions of the fairness in classroom assessment consist of two dimensions. First, he believed that teachers' provision of equal opportunities to demonstrate learning is the prerequisite to achieving fairness in classroom assessment (Tierney, 2014). Second, he started to question his assessment design and realized that he had not designed logical and explicit questions that would help students understand the assessment criteria.

Compared with the effects of critical reflections on Zhao's CoA, the courses that he had taken in the teacher education program did not seem to play a part in reshaping his CoA. He even found it very difficult to retrieve assessment knowledge learned in the university courses. Hence, he decided to relearn it by searching for information on Baidu—a popular search engine in China. Meanwhile, he recalled how his university professor's view triggered him to relearn about assessment purposes:

Prof. Zhang explained that assessment that helps students reflect on and facilitate learning is formative assessment. (Zhao [II: LL40–41]) … So, I think the assessment purpose in primary schools is equivalent to that of formative assessment because there is little summative assessment in primary school. Even the final exams will be followed by comments on test items in the next semester to give students feedback, whereas the final exams in universities end with only GPA without follow-up actions to help students learn from the exams (Zhao [II: LL194–198]).

Through reflective learning and interaction with the university professor, Zhao relearned the purposes of formative and summative assessment. Although he developed his conception of how different levels of schooling are featured with different purposes of assessment, he mistakenly equated the formative use of summative assessment (Xiao, 2017) to formative assessment. Such misconception can be attributed partly to his inadequate assessment knowledge, lack of screening of online information, and his direct “borrowing” of the university professor's view without scrutiny.

To sum up, Zhao's CoA had changed from a relatively simple perception of constructs in assessment criteria to further understandings of assessment purposes, non-achievement factors as part of assessment criteria, fairness in classroom assessment, feedback delivery and questioning, and distinction of formative and summative assessment. His conception changes can be attributed to his assessment practice and reflection, the anti-apprenticeship of observation about assessment, his associate teacher's teaching, and mentoring from the university supervisor.

Case 2—Qian: A Medium Starting Point and Moderate Changes of CoA

Qian was a pre-service teacher motivated to teach and interact with students. In the focus group interview, Qian described assessment as followed:

Assessment refers to the comprehensive evaluation of students' academic achievement and moral character. … Homework marking, as a most traditional method of assessment, helps teachers gather information on students' mastery of knowledge, reflect on teaching, and then immediately adjust teaching plans (Qian [FGI: LL84–87]).

Qian's initial CoA purposes were multi-dimensional: (1) assessment for evaluating student learning; (2) assessment for diagnosing and facilitating teaching; and (3) assessment for measuring both academic achievement and moral character. These conceptions were formed through “years of learning experiences as students” (Qian [FGI: L91]) in schools and the university and further expanded during the practicum:

Assessment helps teachers gather information about students' mastery of knowledge and skills, locate difficulties in learning, help them correct mistakes to facilitate student learning. Assessment also helps teachers reflect on the teaching, and then adjust teaching plans. … It is very important for teachers to assess students' all-round ability in English listening, speaking, reading and writing rather than merely focusing on one aspect (Qian [II: LL184–189]).

This excerpt suggests that Qian's CoA purposes were furthered after the practicum. First, he knew more specifically how teachers may gain diagnostic information about student learning from assessment. Second, he emphasized the importance of assessing students' overall communicative competence without neglecting any of the specific language dimensions.

Besides, Qian's daily routine of marking student homework oriented him to pay attention to other non-achievement factors in addition to moral character:

I can know how well they understand and apply words, phrases, sentence patterns and grammar from their homework. I can see learning attitudes from the neatness of handwriting and whether they repeatedly making the same mistakes. … I can also see their learning habits. … Some students like scribbling in their exercise books. Others may like writing extremely small English words (Qian [II: LL268–282]).

Though Qian felt marking student homework was “mechanical and trivial” (Qian [II: L217]), he still valued it as a window through which students' learning attitudes and habits can be seen. Motivated by this conception, Qian endeavored to give detailed written corrective feedback on student homework:

If students made some grammatical errors in their homework, I would write “You should pay attention to this grammar point” at the bottom of the page. And I added the correct form of this grammar in detail. … When I saw scribbles, I couldn't help writing in big and red “Pay attention to your handwriting” (Qian [II: LL234–244]).

Qian believed that detailed written corrective feedback was “more useful than vacuous scores or grades” (Qian [II: L264]). This belief was enacted in his practice, eliciting different student responses:

When I was strolling in the classroom during recess, some students asked me about the grammatical errors for further explanation. Some even retorted with laughter: “But I think my handwriting is not bad.” Other students would just write down what they think of my feedback in their exercise books (Qian [II: LL245–251]).

Qian's interactions with his students helped him understand how his students took his feedback differently: some accepted it, asked for clarification, and acted on it; some refused to take it by defending for themselves; some others discussed with Qian about his feedback. Qian seized these opportunities to sustain feedback dialogues with his students, which may lead to fruitful learning outcomes by overcoming the limitations of one-way transmission of feedback and reconciling teachers' and students' different perceptions of feedback (Yang and Carless, 2013).

This alignment between Qian's conceptions and practice of feedback, however, was disrupted when he was confused by the feasibility of giving detailed written corrective feedback and thus consulted his associate teacher (Ms. Liu), who simply assigned letter grades without any written feedback:

I discussed with her how to correct homework more effectively. She suggested omitting detailed written corrective feedback, as there is not enough time for a teacher who shoulders heavy teaching duties to write corrective feedback for every student. But I think it depends on a case by case basis. … Maybe I will be a more efficient teacher soon. I can deal with it more quickly (Qian [II: LL344–352]).

Qian, with a critical mindset, did not follow Ms. Liu's “advice,” which can be attributed to three factors. First, Qian's firm beliefs in giving effective feedback mediated his uptake of external knowledge of feedback, as he stressed that “the advantages of students' active engagement with detailed written feedback outweigh the time constraint” (Qian [II: LL356–357]). Second, his own “creative and critical thinking developed in the university” (Qian [II: L171]) and awareness of the assessor identity prompted him not to follow in the footsteps of Ms. Liu. Third, while Ms. Liu generally preferred to assign grade without written feedback, she still granted Qian considerable autonomy by giving flexible suggestions rather than coercive orders.

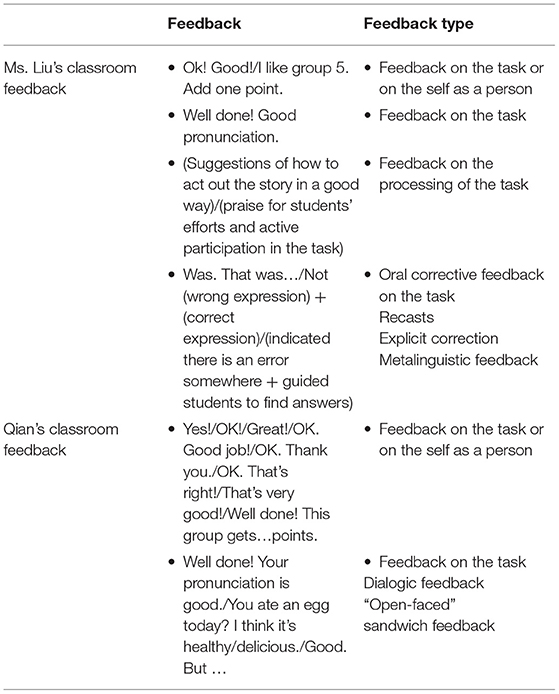

Despite her “advice” for not giving student detailed written feedback, Ms. Liu still played an exemplary role in delivering effective oral feedback on the processing of the tasks and the tasks themselves (Hattie and Timperley, 2007) (Qian [COS-1, 2, 3, and 5]). However, with the absence of discussion of effective oral feedback delivery between Qian and Ms. Liu, Qian's feedback practice was to a large extent confined to the delivery of positive and general feedback containing little information on the task (Table 4) (Qian [CO]).

Qian emphasized that “timely feedback was more effective than the delayed one” (Qian [II: L120]). Additionally, he tended to give oral corrective feedback in a euphemistic way, that is, giving “open-faced” sandwich feedback (positive comments followed by negative correction feedback) (Parkes et al., 2013), “to reduce the shock of negative feedback and protect students' learning motivation and self-esteem” (Qian [II: LL127–128]). However, Qian's understanding of the power of feedback was limited to how it may boost motivation and self-esteem, without an awareness of how different types of feedback may facilitate student learning to different degrees. Qian's inadequate knowledge and practice of feedback, as well as insufficient mentoring from Ms. Liu, may contribute to his partial understanding of feedback.

In summary, Qian enriched his conceptions regarding assessment purposes of facilitating both teaching and learning, non-achievement factors as assessment criteria, and significance of student engagement with the assessment. Besides, his conceptions of feedback had been both expanded and constrained. These conception changes could be attributed to Qian's assessment practice, critical thinking, reflection, interactions with students, and mentoring from his associate teacher.

Case 3—Sun: A Good Starting Point and Considerable Changes of CoA

Sun was a highly motivated pre-service teacher with relatively well-developed entry CoA. He stated his understanding of assessment purposes before the practicum:

The purposes of assessment are to reflect on and adjust (teaching and learning). For students, assessment serves for gathering evidence of learning. Then students can adjust his learning foci and strategies based on the feedback of assessment. And teachers should make use of the assessment from students and colleagues to adjust their teaching methods (Sun [FGI: LL20–23]).

Sun's intuitive CoA purposes can be broken into two dimensions. Assessment for teaching was understood as how assessment data from both students and colleagues can improve instruction, while assessment for learning was perceived as how students can benefit from assessment feedback. This commendable initial conception was later enriched in his practicum experience:

The purposes of assessment in primary schools include improving student learning motivation, learning attitudes, memory, and imitation. Because pupils are not so good at logical thinking, they mainly learned English listening, speaking, reading and writing through memorization and imitation (Sun [II: LL582–589]).

This excerpt suggests that the practicum experience helped Sun contextualize his CoA for learning in the primary school context, that is, various non-achievement factors that benefit student development constitute a large part of learning evidence (Cheng and Sun, 2015). It is not surprising that Sun gave priority to these non-achievement factors within the Chinese context, where learning is believed to be closely related to effort than ability (Wang, 2008). Regrettably, his understanding of the “ubiquity of assessment” (Sun [II: L596]) through both in-class assessment activities and after-class communication with students did not lead to his follow-up learning about how various assessment activities can be done more reliably and validly.

While conducting in-class assessment activities, Sun tried to engage students in assessment by conducting activities like conversation practice and role-play in his open class. He stated:

Assessment is not unilateral. It is a process of interaction. It is necessary for teachers to enhance students' engagement with assessment so that they can create active and positive classroom atmosphere, and take further actions to improve themselves (Sun [II: LL614–616]).

Sun highlighted the interactive nature of assessment and the value of students' agentic engagement. Although he made sense in terms of how teachers may use the assessment information to improve their teaching, he seemed to mistakenly consider assessment as a tool to live up classroom atmosphere. As a pre-service teacher, his dual roles as both a teacher and student granted him more opportunities to see the connection between teaching and learning. For instance, he found that the effectiveness of assessment depends on students' agentic engagement with it. His intuitive perception appears to be consistent with prior research (e.g., Winstone et al., 2017) that highlights the vital role of students' active engagement in feedback effectiveness.

To enhance students' engagement, Sun paid great attention to his interaction with students:

After communicating with students, I realized that students have different foci of attention in assessment. Teachers should consider students' varied needs. Otherwise, students may regard feedback as hollow words (Sun [II: LL285–288]).

This quote suggests that Sun's interaction with students may also play a role in his CoA because he started to consider student needs in assessment. His heightened awareness of student needs in feedback processes is important for promoting dialogic feedback and student learning (Yang and Carless, 2013).

To enhance student engagement with feedback, one of Sun's approaches was to involve students in peer assessment. He reflected on peer assessment as follows:

Peer assessment is more effective than teacher assessment in some circumstances because students value receiving peers' attention and acknowledgment. I observed that they usually gave brief and positive peer feedback such as “Good performance!” So, I decided to deliver guiding feedback first to elicit students' detailed peer feedback. (Sun [II: LL241–251]) … However, some students would give an inappropriate assessment of others' behavior, which could be misleading for students. I think primary school teachers should provide scaffolding for students to help them appropriately deliver peer assessment (Sun [II: LL254–258]).

This excerpt provides insights into how Sun's agency in assessment has played a role in CoA change through his reflective learning about assessment. First, he realized the importance of peer feedback in facilitating student learning (Cartney, 2010). Second, he saw the potential problems of peer feedback if not carefully designed and sufficiently supported (Ginkel et al., 2017). Third, his suggestion of teacher scaffolding of peer assessment highlights his understanding of the connection between teachers' and students' feedback literacy (Xu and Carless, 2017). Fourth, this connection needs to be addressed by developing student assessment literacy to enhance students' involvement in, and uptake of assessment (Carless and Boud, 2018).

Sun's conception of feedback was then also oriented toward enhancing students' uptake of feedback. After observing his associate teacher (Mr. Liang)'s class, Sun questioned his initial conception about giving general oral feedback (e.g., “Good job!” “Well done!”) (Sun [II: LL608–610]). Unlike Zhao and Qian, Sun “discussed a lot about feedback with Mr. Liang” who advised him to give “detailed feedback that meets student needs” (Sun [II: LL545–546]). Sun then took his advice in his practice, as observed in his open class (see Table 5) (Sun [CO]).

As Table 5 reveals, although his feedback only focused on the task being processed by the students, he endeavored to follow Mr. Liang's feedback practice which had a wider scope. Although Sun realized that it is important to give detailed and individualized feedback on both strengths and weaknesses, he did not have a chance to reflect on his feedback practice and improve it accordingly. Nevertheless, his repeated comment that “assessors should avoid vacuous compliments” (Sun [II: LL264, 269, 288, and 360]) is applaudable, indicating his enhanced conception about enabling students' uptake of feedback by giving students detailed feedback on the task rather than simply delivering vacuous and face-saving feedback.

Sun's CoA changes benefited from not only Mr. Liang's mentoring but also his own special experience of replacement of associate teachers:

Every experienced teacher has their own set of assessment patterns based on specific teaching contexts. Mr. Zhou focused on learning motivation and participation, while Mr. Liang focused on students' mastery of knowledge and skills. I mainly copied my associate teachers' assessment patterns because I haven't developed my own pattern. Of course, I will gradually develop my assessment pattern after entering the teaching profession (Sun [II: LL312–317]).

Luckily, the different assessment practices of the two associate teachers did not confuse Sun. On the contrary, this experience enhanced his understanding of the context-dependent and evolving nature of teacher assessment literacy. Sun reflected on the strengths of each associate teacher, as well as how he learned from them accordingly:

Mr. Liang laid more emphasis on developing my assessment literacy. He demonstrated assessment methods and skills in his class and shared assessment-related stories with me after class (Sun [II: LL276–280]).

His agency in learning about assessment as a teacher greatly contributed to his CoA changes. His agency can be seen not only in his high motivation to learn from his associate teachers but also in his constant readiness to learn from, and his reflexivity of, other teachers' and peer student teachers' assessment practices:

I heard that there was a teacher who directly told a parent that her child might had copied others' homework. However, the parent misunderstood the teacher and scolded the student for repeatedly copying others' work. The student felt he was put in the wrong and showed a growing antipathy toward learning. … Indirect feedback may lead to misinterpretation of original intention and put pressure on students worried about being snitched on. (Sun [II: LL84–93]) … One of my classmates in another field school spent a lot of money on buying gifts for students as rewards. I think it is neither necessary nor appropriate (Sun [II: LL553–555]).

This excerpt suggests that Sun refined his CoA through reflecting on others' assessment practice, such as effective communication of assessment results and ethical practice in assessment. His understanding of the uselessness of extrinsic rewards seems to echo Hattie and Timperley's (2007) finding concerning how extrinsic rewards provide little task information for student learning.

In short, Sun significantly expanded his CoA in terms of assessment purposes, constructs in assessment criteria, peer feedback, student involvement and engagement. Such CoA changes were a joint outcome of his strong agency in assessment, assessment practice, interactions with students, and his associate teachers' mentoring.

Summary of Findings

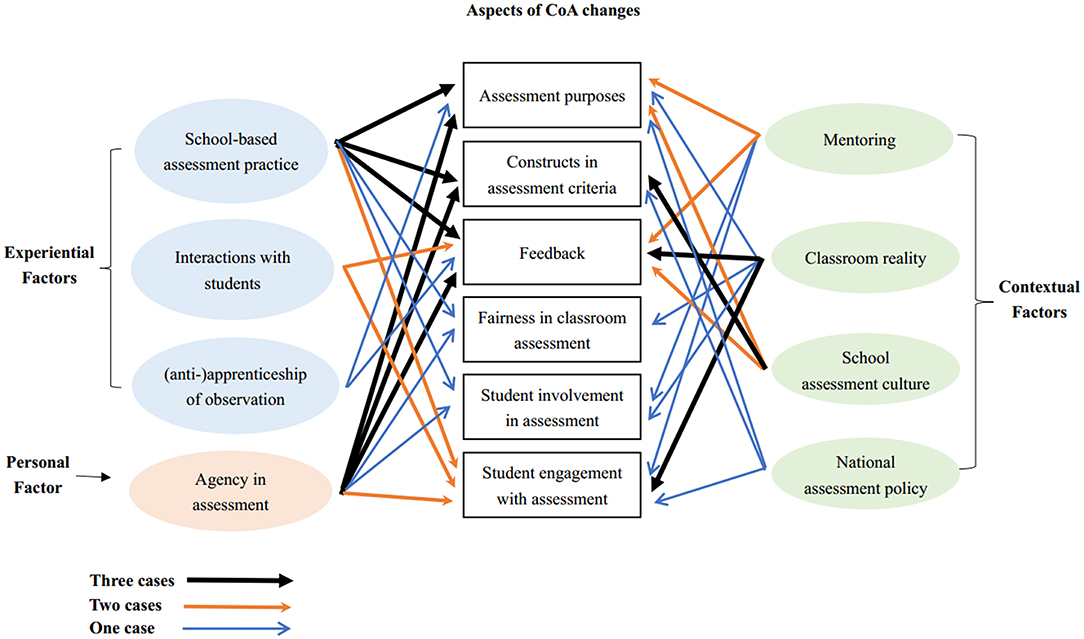

To sum up, the three teachers' CoA changes include (a) a more comprehensive understanding of assessment purposes; (b) a more realistic understanding of constructs in assessment criteria in primary schools; (c) a broader understanding of power and strategies of feedback; and (d) an emerging awareness of how to ensure fairness in classroom assessment, how to involve students in assessment processes, and how to enhance students' engagement in assessment. Findings also suggest that changes in the teachers' CoA vary across cases. A range of influential factors for these CoA changes were identified, including one personal factor (i.e., agency in assessment); three experiential factors which refer to individual pre-service teachers' experiences of training, language learning, teaching, and assessment [i.e., school-based assessment practices, interactions with students, and (anti-)apprenticeship of observation about assessment]; and two contextual factors which refer to people or external factors that influence pre-service teachers' CoA changes in the field school (i.e., mentoring from associate teachers and the university professor). Through cross-case analysis, the similarities and differences of the participants' varied conception change in different aspects of assessment and the influential factors are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Pre-service teachers' conception-of-assessment (CoA) changes and influential factors during practicum.

Discussion

Based on the summary of findings, our discussion mainly focuses on how pre-service teachers' CoA changes are diverse but limited, as well as how personal, experiential, and contextual factors have exerted differentiated influences on these CoA changes (see Figure 1).

Diverse but Limited CoA Changes During Practicum

The present study addresses the underexplored area of conception changes in assessment during practicum, and contributes to the scholarship of pre-service teachers' changing beliefs about teaching or learning (Lawson et al., 2015). As teachers' CoA serves as an interpretive framework of their assessment literacy in practice (Xu and Brown, 2016), findings of this study can advance our knowledge of how to enhance teacher assessment literacy and improve the effectiveness of classroom assessment.

Our findings highlight the long-neglected role of practicum in shaping pre-service teachers' CoA. Compared with results about how CoA changed through assessment courses (Smith et al., 2014; Levy-vered and Alhija, 2018), our study suggests practicum could be a more critical component of pre-service teacher education in shaping pre-service teachers' CoA. Although brief, practicum provides a real arena for prospective teachers to trial their conceptions and practices of assessment while being mediated by various factors.

One evident change of CoA is about assessment purposes. Findings show that the pre-service teachers initially perceived assessment as a tool for diagnosing and facilitating learning and for developing student moral character, partly echoing prior studies about Chinese teachers' CoA purposes (e.g., Chen and Brown, 2013). These partial CoA were partly due to the pre-service teachers' prior educational experience as students and to the time-honored moral purpose of assessment, which is endowed by the Confucian heritage cultures in China (Kennedy, 2016). When compared with prior finding about pre-service teachers' CoA being less harmful and more valid by the end of assessment courses (Levy-vered and Alhija, 2018), our finding suggests that practicum that exposed them to complex realities of assessment in authentic school contexts may have more value in terms of developing a more comprehensive understanding of how effective assessment can be worked out. During the practicum, the pre-service teachers realized that assessment serves for varying purposes such as classroom management and teaching facilitation. Their newly developed conception of the role of assessment in classroom management can be attributed to the large class size and student characteristics in primary schools. While large class size is reported as an obstacle to assessment for learning practice (Liu and Xu, 2017; Xu and Harfitt, 2019), our study suggests that it may serve as an accelerator that helps pre-service teachers think practically.

Besides, our findings suggest that practicum as a transitional period may not only familiarize pre-service teachers with teaching realities but also provide them with opportunities for gradually constructing the identity as assessors. This finding supplements prior findings which highlight an enhanced assessor's role after learning about various assessment issues in assessment courses (Deluca et al., 2013a; Levy-vered and Alhija, 2018). Our emphasis of the role of practicum in shaping student teachers' identity as assessors suggests the necessity of connecting assessment education with real school contexts, as school-based learning can exert a transformative influence on pre-service teachers' cognitive development (Stuart and Thurlow, 2000; Tang, 2004; Yuan and Lee, 2014).

Another significant change of CoA concerns with constructs in assessment criteria. During the practicum, the pre-service teachers added a series of “academic enablers” (McMillan, 2001, p. 25) (i.e., memorization, imitation, student engagement, learning motivation, attitudes, and habits) as non-achievement factors that are needed to be assessed as part of student learning. This finding corroborates Cheng and Sun's (2015) finding that Chinese teachers give priority to non-achievement factors. Besides, our study shows that pre-service teachers tend to consider abilities such as memorization and imitation in assessment, whereas Brown and Gao's (2015) study suggests that in-service teachers in China consider “comprehension, problem-solving, inquiry, and creativity” or “overall quality of students as humans” (p. 10). Such differences suggest that the non-achievement factors considered by Chinese teachers may vary across both career stages and school levels, with pre-service teachers thinking at a more micro level while their in-service counterparts focusing on more global and general issues.

Noticeable changes are also found in the pre-service teachers' conceptions of feedback. All the three pre-service teachers started the practicum with little understanding of feedback but gradually came to realize the importance and strategies of delivering effective and informative feedback through classroom observation and their own feedback practice. However, their feedback practices were found not to develop in alignment with these reshaped conceptions, for the case teachers frequently gave positive but irrelevant feedback on the tasks. Besides, the teachers' CoA changes concerning fairness in classroom assessment and students' involvement in and engagement with assessment are not prominent, although these two assessment dimensions are recognized as key components of classroom assessment theory and practice (Tierney, 2014; Rasooli et al., 2018) and teacher assessment literacy (DeLuca et al., 2016; Xu and Brown, 2016). The insufficient practice during the practicum might mainly account for the misalignment between the teachers' actual feedback practices and their reshaped CoA, as well as for the teachers' partial CoA changes. These findings echo the call for more school-based assessment practice during the practicum to help pre-service teachers to fully reshape and internalize CoA and to fill the gap between conceptions and practice of assessment (Cheng et al., 2010; Deluca and Klinger, 2010).

Differentiated but Complementary Influence of Experiential, Personal, and Contextual Factors

Insights into the influential factors are critical for facilitating CoA changes and teacher assessment literacy development. Our findings indicate that pre-service teachers' CoA changes during practicum were to a large extent influenced by their personal and experiential factors, whereas less supported by contextual factors.

First, the school-based assessment practices as an important experiential factor may greatly contribute to pre-service teachers' CoA changes in both positive and negative ways. Although brief, the 6-week practicum in this study provided various opportunities for pre-service teachers to engage in assessment-related activities, such as classroom observation, homework marking, and open class. These experiences could facilitate pre-service teachers in consolidating, expanding and changing their CoAs.

Another significant experiential factor could be the pre-service teachers' ongoing interaction with students, echoing prior findings of the role of the practicum community in prospective teachers' conception change (Stuart and Thurlow, 2000; Ng et al., 2010). The interaction may take various forms and play different roles, evidenced by Qian's emphasis on student responses and Sun's focus on student assessment needs. Our finding corroborates Yang and Carless' (2013) finding concerning the importance of building mutually trusting teacher–student relationships in enhancing students' uptake of effective feedback.

Our finding not only testifies to the roles of (anti-)apprenticeship of observation in constructing pre-service teachers' initial CoA (Levy-vered and Alhija, 2018) but also further clarifies how emotional experiences of the (anti-)apprenticeship of observation about assessment can positively or negatively influence their CoA development. Qian's case reveals that his experience of apprenticeship of observation has contributed to the formation of his multidimensional CoA purposes before the practicum. On the contrary, years of observational experience of their own teachers' assessment practice (e.g., Zhao's experience of receiving brief and positive feedback as a student) may also constrain pre-service teachers from critically reexamining their CoA and subsequently changing their practice (Xu and Brown, 2016), as evidenced by Zhao's practice of using positive feedback mainly to enhance students' self-esteem and learning motivation. Zhao's case also suggests that reflection on anti-apprenticeship of observation about assessment (i.e., his unpleasant experiences of being assessed in appropriately) could be triggered by the practicum experiences, which support pre-service teachers to critically reshape their CoAs.

Another important original insight generated from this study is the prominent role of teacher agency in assessment (i.e., awareness of assessment, reflection, and critical thinking) in positive CoA changes. Although previous studies have consistently emphasized the role that agency plays in teachers' cognitive development (Lasky, 2005; Yuan and Lee, 2014; Kayi-Aydar, 2015), our study argues for its critical role in enabling them to think and act like an assessor, which empowers them to resist conventional assessment practices and enact their own conceptions in practice (Xu and Brown, 2016). As evidenced by Sun's and Qian's cases, their agency in assessment may stem from their earlier experiences with assessment, their motivation for being a good teacher, and their critical thinking skills developed from years of learning. Without pre-service teachers' strong agency in assessment, the learning potential of school-based assessment practice cannot be tapped to its utmost. How pre-service teachers may benefit from the practice thus becomes random, depending on how facilitative the contextual conditions are and how agentic the pre-service teacher is. A positive example can be found in how Qian's conception about written feedback was strengthened through his active participation in marking student homework and providing written feedback, while a negative example can be found in how Qian's conception about oral feedback was constrained by insufficient reflection on oral feedback and inadequate mentoring. Although the process of how agency enabled pre-service teachers' identity construction was not explored in this study, the inextricable relationship between the two warrants further study.

Findings identify mentoring from associate teachers as a salient contextual factor for pre-service teachers' CoA change, echoing Yuan and Lee's (2014) finding. More importantly, we argue that the assessment literacy of associate teachers may grant or withhold opportunities for pre-service teachers to reexamine and change their CoA and to enhance assessment literacy development during practicum. Highly assessment-literate associate teachers can model effective assessment practice and provide explicit guidance to pre-service teachers concerning typical assessment procedures, methods, and strategies (Gao and Benson, 2012). Consistent with previous research suggesting associate teachers' involvement in pre-service teachers' lesson planning and preparation as well as post-class communication and discussion (Yuan and Lee, 2014), our data further reveal that such assistance and suggestions are usually limited to teaching and learning, with assessment being neglected and considered as a separate part from teaching and learning. Among the three cases, Sun's associate teacher, who was more assessment literate and motivated, did help Sun reshape his CoA and improve his assessment literacy through modeling and dialogue.

Findings also show that other contextual factors such as classroom realities, school assessment culture, and national assessment policy may place constraints on pre-service teachers' conception change concerning what they should do and what they should not do in assessment. In particular, the large class size (Xu and Harfitt, 2019), the deep-rooted routine practices in school assessment culture (Fuller et al., 2015), and the challenge of implementing formative assessment in a test-dominated Chinese context (Xiao, 2017) seem to have prompted the participants to reflect on their initial CoAs. Although these contextual factors seem to have constrained their classroom assessment practice, reflections on these constraints have raised their awareness concerning how to deliver effective feedback, how to achieve fairness in classroom assessment, and how to fulfill multiple assessment purposes in a large class. In other words, how pre-service teachers can mitigate such constraints might depend on their agency in assessment, as well as mentoring from their associate teachers and university professor. For example, while Zhao took the routine assessment activities (e.g., scoring groups' class participation on the blackboard and giving tangible rewards) for granted without querying their effects on student learning, Qian's and Sun's critical reflection of others' assessment practices helped reshape their conceptions concerning written corrective feedback and tangible rewards. Qian's and Sun's exercise of their agency in assessment enabled them to act like assessors: handling challenges brought by large classes, resisting ineffective routine practice rooted in school assessment culture, and reexamining their initial CoA concerning the effects of feedback.

Limitation, Implications, and Conclusion

This study explored how pre-service teachers' CoAs changed over practicum and what influential factors contributed to the changing process through a multiple-case study in China. The findings indicate that pre-service teachers developed more comprehensive and realistic CoAs during practicum. These CoA changes were influenced by various factors at personal, experiential, and contextual levels. These findings suggest that with adequate supporting conditions in place, pre-service teachers could benefit more from the practicum toward becoming assessment-literate teachers with refined CoA.

Admittedly, this study has a few limitations related to the research design. The focus group interview may not have fully extract each participant's initial CoA, although it was practical to implement when the participants had little knowledge of the topic at the start of the practicum. Besides, as the pre-service teachers did not have a chance to engage with exam-related activities during the practicum, the influence of high-stakes emanations on their CoA change has remained unexplored. Despite these limitations, some implications for teacher education can be drawn from our findings.

First, pre-service teachers need longer hours to be more fully engaged in assessment practice during practicum. Sufficient exposure to various assessment practices is a good starting point for pre-service teachers to engage in critical reflection on their CoAs, learn to confront the complexities and challenges of assessment practice, and (re)construct their identity as assessors.

Second, teacher educators and associate teachers are expected to collaborate to provide scaffolding for pre-service teachers to improve their assessment literacy and reshape their CoA. They also need to put in joint efforts to empower prospective teachers to question conventional practice and their mentoring. To achieve this, they could (a) grant pre-service teachers sufficient autonomy to trial their ideas; (b) help pre-service teachers fit in the field schools by informing them about the rules and regulations in the schools, subject matter, pupils' needs, and so on; (c) build “instructor-mediated reflection” (Moodie, 2016, p. 39) mechanism to help pre-service teachers reflect on their assessment-related experiences; and (d) improve their own assessment literacy to provide modeling.

Third, assessment-related training is suggested to include “critical reflection” components that allow pre-service teachers to critically examine their CoA, and in particular, influences of their (anti-)apprenticeship of observation on CoA. This is because an assessment course that only provides basic assessment principles is insufficient to help pre-service teachers develop their CoA and reexamine their apprenticeship of observation about assessment. To ensure sustainable assessment training which can effectively counterbalance the negative effects of anti-apprenticeship of observation, teacher agency needs to be prioritized as one of the goals of teacher training in assessment.

While generalization of the findings of this case study to other contexts should be cautious, future research needs to be conducted to understand how teachers' CoAs evolve along their professional trajectory through practicum into their first few years of teaching. Comparative studies concerning how different personal, experiential, and contextual factors may influence pre-service teachers' CoA changes in different school contexts are also needed.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Research Ethics in Social Science, Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong. All participants gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author Contributions

YX contributed to the conception and design of the work, data collection and analysis, and revision of the work. LH contributed to the data collection and analysis, drafting the work, and revision of the work.

Funding

Financial support for this study was provided by Guangdong University of Foreign Studies (Grant No. 19GWYJSCX-10).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2019.00145/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Moral character refers to the stable and consistent characteristics and inclination about moral principles and norms (New Century Chinese–English Dictionary, 2016).

2. ^The data references are specified as follows. CO stands for classroom observation, FGI for the focus group interview, II for the individual interviews, COS for classroom observation sheet, and LP for a lesson plan. The number(s) right after the data source abbreviations are the specific session within the data source. For example (Zhao [FGI: LL64–69]), indicates that the quote is from Zhao's responses in the focus group interview and in the lines of 64 to 69 of the transcripts. (Zhao [II: LL200–208]) indicates that the quote is from Zhao's responses in the individual interview and in the lines of 200 to 208 of the transcripts. (Qian [COS-1, 2, 3, 5]) refers to the first, second, third, and fifth classroom observation sheets filled by Qian.

3. ^University Comprehensive Evaluation: a scientific method of comprehensive quantitative evaluation of students' overall quality of morality, intelligence, physique, and aesthetics in contemporary colleges or universities.

References

Anderson, L. M., and Stillman, J. A. (2013). Student teaching' s contribution to preservice teacher development: a review of research focused on the preparation of teachers for urban and high-needs contexts. Rev. Educ. Res. 83, 3–69. doi: 10.3102/0034654312468619

Barcelos, A. M. F., and Kalaja, P. (2011). Introduction to beliefs about SLA revisited. System 39, 281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2011.07.001

Barnes, N., Fives, H., and Dacey, C. M. (2015). “Teachers' beliefs about assessment,” in International Handbook of Research on Teacher Beliefs, eds H. Fives and M. G. Gill (New York, NY: Routledge), 284–300.

Bonner, S. M. (2016). “Teachers' perceptions about assessment competing narratives,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment, eds G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York, NY: Routledge), 48–76.

Borg, S. (1999). Studying teacher cognition in second language grammar teaching. System 27, 19–31. doi: 10.1016/S0346-251X(98)00047-5

Boyd, A., Gorham, J. J., Justice, J. E., and Anderson, J. L. (2013). Examining the apprenticeship of observation with preservice teachers: the practice of blogging to facilitate autobiographical reflection and critique. Teach. Educ. Q. 40, 27–49.

Brookhart, S. M. (2011). Educational assessment knowledge and skills for teachers. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 30, 3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.2010.00195.x

Brown, G. T. L. (2011). “New Zealand prospective teacher conceptions of assessment and academic performance: neither student nor practicing teacher,” in Democratic Access to Education, eds R. Kahn, J. C. McDermott, and A. Akimjak (Los Angeles, CA: Antioch University Los Angeles, Department of Education), 119–132.

Brown, G. T. L., and Gao, L. (2015). Chinese teachers' conceptions of assessment for and of learning: six competing and complementary purposes. Cogent Educ. 2, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2014.993836

Brown, G. T. L., Lake, R., and Matters, G. (2011). Queensland teachers' conceptions of assessment: the impact of policy priorities on teacher attitudes. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.003

Brown, G. T. L., and Remesal, A. (2012). Prospective teachers' conceptions of assessment: a cross-cultural comparison. Spanish J. Psychol. 15, 75–89. doi: 10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n1.37286

Carless, D. (2011). From Testing to Productive Student Learning: Implementing Formative Assessment in Confucian-Heritage Settings. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203128213

Carless, D. (2019). Feedback loops and the longer-term: towards feedback spirals feedback spirals. Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. 44, 705–714. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1531108

Carless, D., and Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. 43, 1315–1325. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Cartney, P. (2010). Exploring the use of peer assessment as a vehicle for closing the gap between feedback given and feedback used between feedback given and feedback used. Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. 35, 551–564. doi: 10.1080/02602931003632381

Chen, J., and Brown, G. T. L. (2013). High-stakes examination preparation that controls teaching: Chinese prospective teachers' conceptions of excellent teaching and assessment. J. Educ. Teach. 39, 541–556. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2013.836338

Chen, J., and Brown, G. T. L. (2018). Chinese secondary school students' conceptions of assessment and achievement emotions: endorsed purposes lead to positive and negative feelings. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 38, 90–108. doi: 10.1080/02188791.2018.1423951

Cheng, L., and Sun, Y. (2015). Teachers' grading decision making: multiple influencing factors and methods. Lang. Assess. Q. 12, 213–233 doi: 10.1080/15434303.2015.1010726

Cheng, M. M. H., Cheng, A. Y. N., and Tang, S. Y. F. (2010). Closing the gap between the theory and practice of teaching: implications for teacher education programmes in Hong Kong. J. Educ. Teach. 36, 91–104. doi: 10.1080/02607470903462222

Deluca, C., Chavez, T., Bellara, A., and Cao, C. (2013b). Pedagogies for preservice assessment education: supporting teacher candidates' assessment literacy development, Teach. Educ. 48, 128–142. doi: 10.1080/08878730.2012.760024

Deluca, C., Chavez, T., and Cao, C. (2013a). Establishing a foundation for valid teacher judgement on student learning: the role of pre-service assessment education. Assess. Educ. Principles Policy Pract. 20, 107–126. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2012.668870

Deluca, C., and Klinger, D. A. (2010). Assessment literacy development: identifying gaps in teacher candidates' learning. Assess. Educ. Principles Policy Pract. 17, 419–438. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2010.516643

DeLuca, C., LaPointe-McEwan, D., and Luhanga, U. (2016). Teacher assessment literacy: a review of international standards and measures. Educ. Assess. Eval. Accountabil. 28, 251–272. doi: 10.1007/s11092-015-9233-6

Deneen, C., and Boud, D. (2014). Patterns of resistance in managing assessment change. Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. 39, 577–591. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2013.859654

Deneen, C. C., and Brown, G. T. L. (2016). The impact of conceptions of assessment on assessment literacy in a teacher education program. Cogent Educ. 3, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1225380

DiPerna, J. C. (2006). Academic enablers and student achievement: implications for assessment and intervention services in the schools. Psychol. Schl. 43, 7–17. doi: 10.1002/pits.20125

Farrell, T. S. C. (2007). Reflective Language Teaching: From Research to Practice. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2008). “Here's the book, go teach the class”: ELT practicum support. RELC J. 39, 226–241. doi: 10.1177/0033688208092186

Farrell, T. S. C. (2012). Novice-service language teacher development: bridging the gap between preservice and in-service education and development. TESOL Q. 46, 435–449. doi: 10.1002/tesq.36

Fuller, M., Henderson, S., and Bustamante, R. (2015). Assessment leaders' perspectives of institutional cultures of assessment: a Delphi study. Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. 40, 331–351. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2014.917369

Fulmer, G. W., Lee, I. C. H., and Tan, K. H. K. (2015). Multi-level model of contextual factors and teachers' assessment practices: an integrative review of research. Assess. Educ. Principles Policy Pract. 22, 475–494. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2015.1017445

Gao, X. A., and Benson, P. (2012). ‘Unruly pupils’ in pre-service English language teachers' teaching practicum experiences. J. Educ. Teach. 38, 127–140. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2012.656440

Gebril, A., and Brown, G. T. L. (2014). The effect of high-stakes examination systems on teacher beliefs: Egyptian teachers' conceptions of assessment. Assess. Educ. Principles Policy Pract. 21, 16–33. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2013.831030

Ginkel, S. V., Gulikers, J., Biemans, H., and Mulder, M. (2017). Fostering oral presentation performance: does the quality of feedback differ when provided by the teacher, peers or peers guided by tutor? Assess. Eval. Higher Educ.42, 953–966. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2016.1212984

Graham, P. (2005). Classroom-based assessment: changing knowledge and practice through preservice teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 607–621. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.05.001

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 81–112. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487

Hill, M. F., and Eyers, G. (2016). “Moving from student to teacher: changing perspectives about assessment through teacher education,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment, eds G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York, NY: Routledge), 103–128.

Izadinia, M. (2013). A review of research on student teachers' professional identity. Brit. Educ. Res. J. 39, 694–713. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2012.679614

Izadinia, M. (2016). Student teachers' and mentor teachers' perceptions and expectations of a mentoring relationship: do they match or clash? Profess. Dev. Educ. 42, 387–402. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2014.994136

Kayi-Aydar, H. (2015). Teacher agency, positioning, and English language learners: voices of pre-service classroom teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 45, 94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.09.009

Kennedy, K. J. (2016). “Exploring the influence of culture on assessment: the case of teachers' conceptions of assessment in Confucian heritage cultures,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment, eds G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York, NY: Routledge), 622–646.

Knapp, N. F. (2012). Reflective journals: making constructive use of the “apprenticeship of observation” in preservice teacher education. Teach. Educ. 23, 323–340. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2012.686487

Lasky, S. (2005). A sociocultural approach to understanding teacher identity, agency and professional vulnerability in a context of secondary school reform. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 899–916. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.003