- 1Harvard University Extension School, Cambridge, MA, United States

- 2Faculty for Latin American Social Science Research, Quito, Ecuador

The learning sciences clarify how people learn best under which conditions and how human variability influences outcomes. Despite great advancements in some learning sciences over the past 30 years, there has been relatively little change in educational science, a sub-field of the learning sciences. To determine why knowledge from the learning sciences has not had a greater impact on educational policy, this study considered evidence from the learning sciences through a previously published systematic review of the literature followed by a Delphi panel of experts on the learning science (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2017). This was compared with a literature review of the trends in leadership decision-making models (data-based; context; distributed; transformative; goal-orientated, results-oriented) (Appendix A in Supplementary Material). This review found 30 current educational policies that contradict evidence from the learning sciences, suggesting a disconnect between educational science and other learning sciences. While there are some initiatives underway in a small number of educational leadership sectors to incorporate more learning science data into decision-making, it is not a norm. The current business-oriented model in educational policy design may explain this divide. The analysis of these results considers how switching from a business to a learning science model may result in different educational priorities. Such a vision offers a distinct and possibly more universally acceptable measure of “quality” education, detached from the immediate social and political goals and independent of the historical times in which they are taken. This paper suggests further research into this new learning sciences evidence-based framework on which educators base policy decisions.

Introduction

Educational Leadership

Public expectations of educational leaders have changed over the past 50 years (Hallinger, 2011). Educational administration has given way to a broader personal role for educational leaders though it continues to maintain the universal objective of free and equal education for all (Shields, 2017). This vision evolved in the United States from the 1960s and 1970s as schools sought out people with “courage, initiative and imagination,” (Broudy, 1962, p. 132) to the 1980s−2000s when the goal was to be caring (Beck, 1994), moral (Hodgkinson, 1991), and ethical (Beck and Murphy, 1994). Starting in the early 2000s educational leadership added on elements of social justice (Bogotch, 2002) and equity in leadership roles (Grogan and Shakeshaft, 2010). Beginning at the turn of the twenty-first. century, technology (Picciano, 2002) and innovation (Jackson and Kelley, 2002) were added to the growing list of educational policy objectives, as was a new value in international comparisons of school leadership and decision-making (e.g., Darling-Hammond et al., 2007).

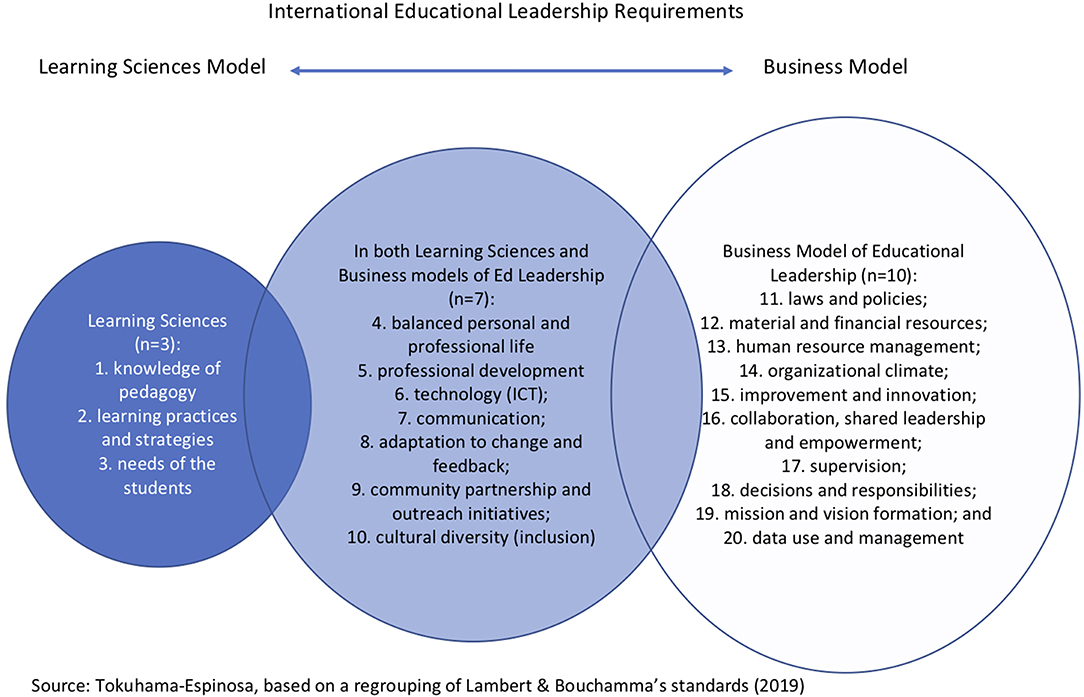

In a 2019 analysis of competency-based standards for school principals in Canada, Australia and the United States, Lambert and Bouchamma found that 85% of the measures that improved student success were similar or identical across countries, suggesting a shared vision of good leadership. These included 20 “professional behavioral standards,” only three of which came directly from the learning sciences (“knowledge of pedagogy/programmes [sic], “learning practices and strategies” and “needs of the students”). Ten of the 20 standards came directly from business models (laws and policies; material and financial resources; human resource management; organizational climate; improvement and innovation; collaboration, shared leadership and empowerment; supervision; decisions and responsibilities; mission and vision formation; and data use and management). The last seven standards can be found in both the learning sciences and business models of educational leadership (balanced personal and professional life [self and others]; professional development [self and others]; technology [ICT]; communication; adaptation to change and feedback; community partnership and outreach initiatives; cultural diversity [inclusion]) (Lambert and Bouchamma, 2019, p. 61). Other international comparisons similarly place educational leadership skills and behaviors into similar categories and suggest both a humanization of leaders in which personal investment into group dynamics is valued, as well a deeper reliance on data for decision-making (e.g., Amanchukwu et al., 2015).

Whereas, it was once thought that the role of principals and department heads was to manage (Grace, 2005), effective leaders are now asked to inspire and transform (Anderson, 2018). The current literature on educational leaders reflects their ever-growing areas of responsibility. On one end of the spectrum this spans from “instructional leadership” (e.g., Hallinger et al., 2015) in which school leaders are meant to drive better teaching initiatives (e.g., Smylie et al., 2016), social-emotional learning and wellness programs (e.g., Bryant et al., 2016), to the other end of the spectrum where they are also responsible for the design and maintenance of sustainable buildings (e.g., Veronese, 2012), and community outreach initiatives (e.g., Epstein, 2018).

To achieve this broad band of responsibilities special competencies are required. Some have researched how these competencies impact success through the effectiveness of different personality types or behaviors (e.g., Judge et al., 2002; Amanchukwu et al., 2015), or how theoretical models of leadership transpose onto school environments (Wang et al., 2017; Gumus et al., 2018). Only a handful of studies have considered the broad range of responsibilities and the difficulties of prioritizing them (e.g., Cheong Cheng and Ming Tam, 1997; Scheerens, 2012). The challenges of being a good educational leader grows with every new competency, which continue to be added to the profile over time and as the role of schools expands. That is, what was valued 50 years remains valued today, but along with those competencies are newly added responsibilities.

The complex nature of educational leadership can make it tempting to go “back to the basics” of good administrative skills and core management concepts. It can be argued that managing numbers is easier than managing people (Pfeffer and Veiga, 1999). Therefore, many find the decision of how to be a good educational leader easier when they lean toward the business and management side of their role than the educational side, meaning many schools are run more like businesses than places of learning (Senge et al., 2012; Onorato, 2013). The business or economic model of quality education celebrates the achievement of cost-effective practices (Levin and Belfield, 2015). As a public good that is almost always underfunded (Ikpa, 2016), many educational leaders feel that their role is to stretch each dollar as far as possible, which in many cases means favoring decisions in which budget items that provide a high level of impact at low cost are favored. Standardized testing is an example of an attractive decision which promises a lot with a relatively low investment (Dolton and Marcenaro-Gutierrez, 2016). Other researchers suggest, however, that education is not actually underfunded, but rather poorly managed (James, 2015), adding to the pressure on educational leaders to spend wisely. An international comparative study found that there is a global trend is the use of “market terminology in educational settings” and “increased accountability and responsibility for school leaders,” (Townsend, 2011, p. 93). There are many, however, who also see the importance and potential gains of embracing more complex models of educational leadership.

Pont, for example (Pont, 2013), describes both professional as well as behavioral standards of principals. In the professional standards he suggests five basic groupings: (a) prioritize guidance (e.g., mission, vision, innovation); (b) establish organizational conditions (e.g., material and financial resources); (c) develop self and others (e.g., professional development and human resource management); (d) exercise pedagogical management (e.g., use of relevant data, technology); (e) create harmony within the school (e.g., communication, organizational climate). In the behavioral standards, he suggests four groupings: (a) flexible management of change (e.g., adaptation to change and feedback); (b) communication; (c) values (e.g., decisions and responsibilities, cultural diversity); and (d) theory linked to practice (e.g., use of relevant data, results, and research). Pont's detailed work suggests that many educators are actively involved in trying to adapt to the growing list of responsibilities and several have managed to systematize the understanding of this range of tasks.

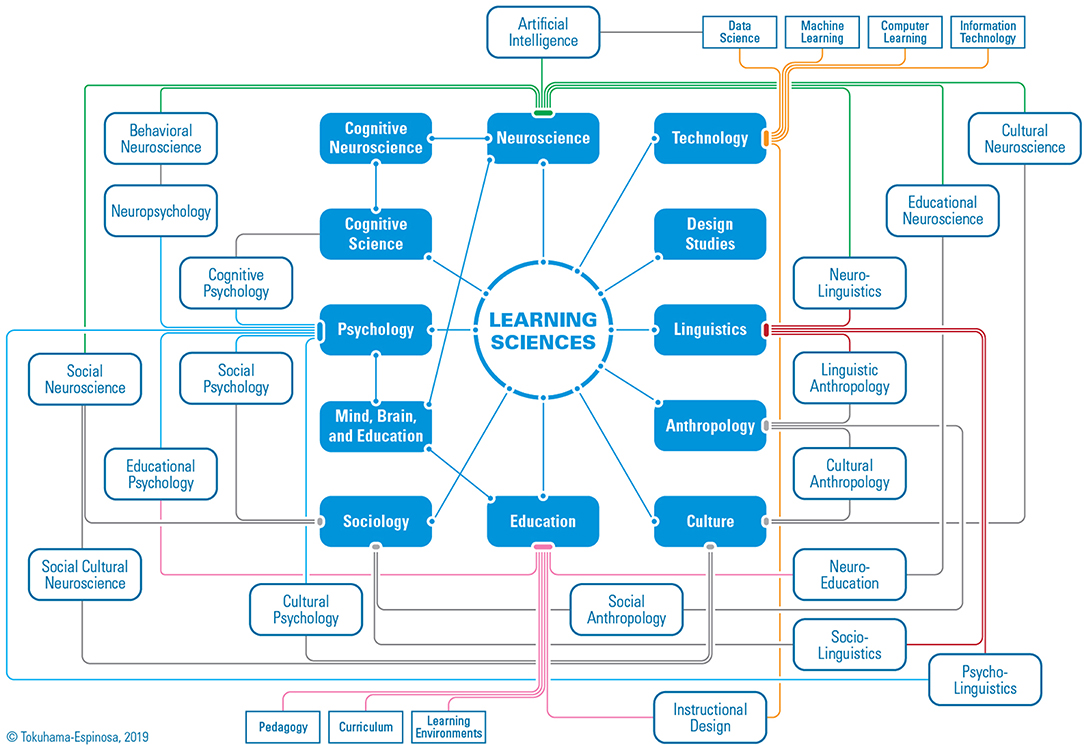

The Learning Sciences

The goal of the learning sciences is to, among other things, study how people learn best and under which conditions (Sawyer, 2005a). Originally called the “science of learning” and changed to the “learning sciences” after the Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences was revised in 2006, this field is really a collection of more than a dozen fields that share common foci on problems (Sawyer, 2008). The learning sciences include a wide range of fields such as neuroscience, psychology and education (Fischer et al., 2018), which grow independently but also collectively.

The new field of Mind, Brain, and Education science, founded in 2004 at the Harvard University School of Education, seeks to elevate teacher practice through greater professionalization (Fischer et al., 2007). In part, this is done by helping educators see their roles are equally important in resolving school challenges as that of neuroscientists and psychologists. Mind, Brain, and Education science is a sub-field of the greater learning sciences and responds to challenges on topics of equal concern to neuroscientists, psychologists and educators. For example, “motivation,” is studied by multiple learning sciences, but each with its own methods and units of analysis (neuroscientists study the brain, psychologist study the mind and educators study learners in classroom contexts). Mind, Brain, and Education science attempts to unify the collective knowledge on any one of these topics through translational research and/or unique methodologies. The logic of this approach is that it is more likely that a transdisciplinary vision of a problem in education will yield a better solution than a single discipline perspective (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2008).

There have been international recommendations, such as the OECD's expert panel on Pedagogical Knowledge and the Changing Nature of Teaching (Guerriero, 2017), and counsel from academia pushing educational leaders to consider “How Can the Learning Sciences (Better) Impact Policy and Practice?” (McKenney, 2018). Additionally, there have been two international Delphi expert panels which sought to gain consensus by learning scientists around the world about how educational leaders' work and teachers' new pedagogical knowledge should be shaped by a learning sciences knowledge base (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2008, 2017). These studies point to a consistent base of knowledge that should inform educational decisions and included a list of research, practice and policy goals that should guide educational decision-making processes (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2015, 2017). Only a small number of teacher colleges and policy makers, such as the Deans for Impact (2015), have actually incorporated learning sciences documentation into their decision-making practices, however. To better understand the slow uptake of information from the learning sciences into educational practice, this study sought to compare educational decision-making with evidence from the learning sciences to see where they differed and why.

Research Question

The primary research question of this study was How and to what extent do educational leaders take into consideration information from other learning sciences when making policy decisions?

Once answered, a new question emerged which was considered in the Conclusions: Can the learning sciences catalyze a change in educational policy priorities?

Materials and Methods

Materials

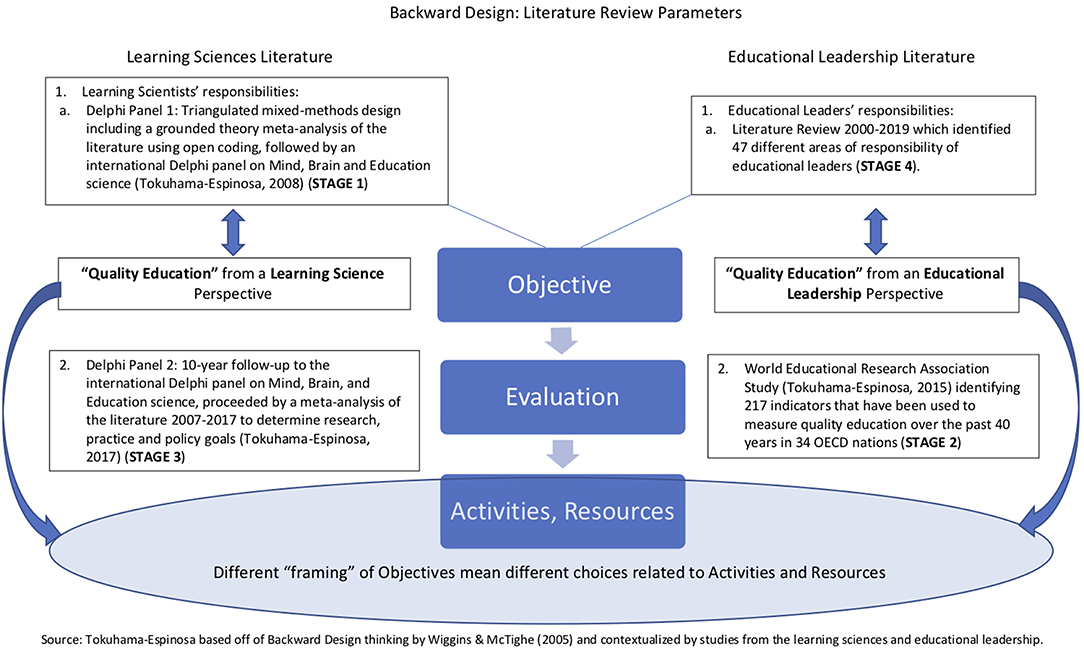

This study reports on the fourth of four stages of research, which is a comparative review of the literature from educational leadership and the learning sciences. The literature review specifically studied how decisions in favor of quality education are made from the educational leadership perspective as compared with the learning sciences perspective. The first stage of this research was a triangulated mixed-methods design including a grounded theory meta-analysis of the literature using open coding, followed by an international Delphi panel on Mind, Brain and Education science conducted by the author for her doctoral thesis (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2008). The second stage was conducted in 2015 which consisted of identifying 217 indicators that have been used to measure quality education over the past 40 years in 34 OECD nations (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2015) and how countries prioritized them based on individual choices including long- vs. short-term investments, budgetary restraints and political promises. This prioritization was used to identify key areas for educational leadership decision-making that were analyzed from both educational administrator perspectives and learning scientists' viewpoints. The third stage was a 10-year follow-up to the international Delphi panel on Mind, Brain, and Education science, proceeded by a meta-analysis of the literature 2007–2017 (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2017), the goal of which was to confirm learning science principles, tenets, neuromyths and research, practice and policy goals. This study along with the first Delphi in 2008 were used to establish the learning scientists' perspective. These background studies provided the platform upon which a comparison of the learning sciences could be made with educational leadership.

The literature review of this paper explores educational leadership research to determine areas of responsibility (Appendix A in Supplementary Material) based on key words used in meta-analyses over the past decade. Research was limited to studies for which there was free or open access or available through the Harvard Online Library (HOLLIS) and published between 2000 and 2019. This list was used to (a) appreciate the spectrum of responsibilities of educational leaders and (b) and compare it with the types of problems learning scientists research.

Methods

Backward Design

This literature review study applied Backward Design planning (objectives, evaluation, activities) (Wiggins and McTighe, 1998) to compare and contrast the ways educational leaders and learning scientists articulate problems, frame research questions and identify objectives. One hypothesis was that heuristics was responsible for both actors' decision-making frameworks.

Backward Design or Understanding By Design from the book title (Wiggins and McTighe, 1998) means beginning with the end in mind, which points to a clear path to success by marked stages of advancement. Backward Design is a planning mentality that was first introduced in the 1940s in business contexts (Tyler, 1949) and since the late 1990s in educational models (Wiggins and McTighe, 1998). In Backwards Design, users are prompted to first identify the objective. Second, they choose the evaluation method(s) that will best offer evidence of advancement toward that objective. Third and last, users are asked to select the activities which would most likely be able to generate the indicators for evaluation.

Wiggins and McTighe note that the most complicated aspect of Backwards Design is appropriately identifying the objective. It is for this reason that this study undertook a review of multiple literary sources to identify the collective agreement on objectives in education, rather than use a single perspective. Wiggins and McTighe note that identifying objectives individually can be deceptively illusive to educators. It is not uncommon to hear teachers declare an activity as an objective (“We will play a crossword puzzle” rather than “Students will improve their vocabulary”). Policy makers also mistakenly label global policy expectations as objectives (“Improve education”) without understanding that the precision with which they can identify the objectives, the easier it will be to both measure and plan activities around it. It is for this reason that meta-analyses and systematic literature reviews were used to identify the objectives of learning scientists and objectives of educational leaders.

The reference to “backwards” is that many educators and educational leaders complete this planning process in the opposite order. That is, it is not uncommon to find that teachers and educational policy makers execute activities/policies and then evaluate them, sometimes without ever considering how closely the objective matched the activity or the evaluation tool.

In business, leaders set a target objective (for sales, or growth in market share, for example). They then choose indicators for success (e.g., earned income or brand affiliation testimonies). Lastly, they select the best activities to reach the objective(s) (e.g., investing in advertising, interviews with product users, and so on). In education, leaders do much the same. Educational leaders identify objectives (e.g., equitable timetabling for teachers or improved test scores), select an evaluation method (e.g., satisfaction rates of teachers and number of hours assigned per person or additional time for student test preparation), then choose activities that help them reach their goals (e.g., buy a timetabling software and review prior years' planning or devise test preparation activities, and so on).

Learning scientists, on the other hand, generally have a more easily articulated objective: enhance learning. The International Society of the Learning Sciences (ISLS) found that learning scientists work at all levels of education and in multiple primary fields (see Figure 2). They also use multiple research tools, units of analysis (students, machines, testing data, and so on), modalities (face-to-face, online, blended), and in all contexts, formal and informal (Yoon and Hmelo-Silver, 2017). To clarify objectives, Nathan et al. (2016) suggested the learning sciences have grown thanks to the study of four aspects of learning: “(a) the design of learning environments and practices, (b) use-inspired basic research, (c) the use of authentic practices and settings to test hypotheses, and (d) an engineering ethos that envisions new practices and resources to support learning” (Yoon and Hmelo-Silver, 2017, p. 169). This suggests that with only slight variation and precision, learning scientists often express the same objective of “learning,” independent of the problem.

Determining the objective in Backwards design is complicated mainly due to the “framing” created by word choice (Nelson, 2011) and influenced by heuristics (Lockton et al., 2013). The precise articulation of objectives permits a clear and logical decision about the choice of evaluation tool and activities.

In summary, the current study consisted of a literature review of educational leaders' areas of responsibility based on publications between 2000 and 2019, which was compared with learning scientists' areas of responsibilities based on two Delphi panels on the learning sciences (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2008, 2017).

The evaluation of educational leader responsibilities was gauged by using the 217 indicators used to measure quality education by OECD member countries between 1975 and 2015 (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2015). The evaluation of the learning scientists' responsibilities was measured by using the second Delphi panel's stated research, practice and policy goals (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2017).

The results permitted the comparison and contrasting of the ways educational leaders and learning scientists approach the objective of quality education. This comparison identified 30 current educational policies that contradict evidence from neuroscience, psychology and other learning sciences, suggesting a disconnect between educational science and other learning sciences.

Theoretical Frameworks

This paper examined the contrasting views of educational leaders and learning scientists in their articulation and response to important topics in education including school start times, learning modalities, curriculum priorities, evaluation, teacher formation among others. To do so, two distinct theoretical frameworks were used: (a) Heck and Hallinger's Educational Leadership perspective; and (b) Sawyer's construct of the Learning Sciences, each of which is briefly described below.

Educational Leadership

Pont (2013), Lambert and Bouchamma (2019), and Heck and Hallinger (2005) divide leadership qualities into two categories: professional and behavioral. Heck and Hallinger (2005) summarize where there is consensus on the changing roles of educational leaders, as well as where there is continued debate:

First, today there is less agreement about the significant problems that scholars should address than in past years. Second, scholarly directions seem to be changing, as an increasing number of scholars are approaching educational leadership and management as a humanistic and moral endeavor rather than a scientific one. Third, although there are more diverse and robust methodological tools available for inquiry, programs of sustained empirical research are few in number. Fourth, a reluctance to evaluate the worth of contrasting conceptual and methodological approaches according to an accepted set of scholarly criteria leaves researchers, policy-makers and practitioners to fall back upon individual judgments of what is useful and valid knowledge. Finally, a lack of empirical rigor in the field continues to impact the development of a future generation of researchers (p. 229).

Based on Heck and Hallinger's work, this paper begins with five premises. First, there are diverse problems in education require leadership attention, and there is not always agreement on the priorities. Second, education is both a humanistic as well as scientific endeavor. Third, more diverse and robust methodological tools should be used in educational inquiry. Fourth, individual judgement is valid but should be informed by data. And fifth, empirical rigor should be improved in educational policy decisions.

The Learning Sciences

The theoretical framework for the learning sciences is derived from Sawyer's work (Sawyer, 2005a,b, 2008) as he has been one of the emergent field's best chronologists and has been featured as a main author in this field by the OECD and the Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences. Sawyer suggests that

Learning sciences is an interdisciplinary field that studies teaching and learning. Learning scientists study learning in a variety of settings – not only the more formal learning of school classrooms, but also the more informal learning that takes place at home, on the job, and among peers. The goal of the learning sciences is to better understand the cognitive and social processes that result in the most effective learning, and to use this knowledge to redesign classrooms and other learning environments so that people learn more deeply and more effectively…This new science is called the learning sciences because it is an interdisciplinary science; the collaboration among these disciplines has resulted in new ideas, new methodologies, and new ways of thinking about learning [bold by author] (Sawyer, 2008, p. 1).

A premise of this paper derived from Sawyer's work is on the role of researchers, teacher-practitioners and educational leaders as people who can leverage the new knowledge from the learning sciences to redesign learning.

Analysis

To analyze the comparison of the educational leadership objectives with learning science objectives, Tokuhama-Espinosa's decision-making process for the evaluation of quality education (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2015) was compared with the Delphi panel's 2017 delineation of goals for quality education (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2017).

The Evaluation of “Quality” in Education

A quote attributed to many people including Cameron (1963) is apropos in analyzing findings: “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.” There is a temptation in education to measure what is easily measurable, rather than identifying what may be the most important (Buros, 1977; Madaus and Stufflebeam, 1988; Coe and Fitz-Gibbon, 1998; Harvey and Newton, 2004; Ozga et al., 2011; Belfield and Brooks Bowden, 2019). This paper considers how educational decision-making often falls into the temptation of low-cost initiatives rather than framing decision-making around stated objectives using the learning sciences. This slant in favor of a business model of education is easily justified in the realm of economic planning, but becomes less defensible when framed in light of student learning objectives.

As Tokuhama-Espinosa found in a 2015 review of 40 years of literature on the evaluation of quality education, decision-makers “may resort to measuring easily available or less costly data, as opposed to appropriate data for their objectives” (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2015, p. 115). The 271 indicators used by OECD countries to measure quality indicators were divided into 11 categories, which were similar to the areas of responsibility mentioned by educational leaders: (a) Coverage; (b) Equality and Equity; (c) Retention, Completion and Staying Rates; (d) Standards; (e) Academic Achievement; (f) Teachers and Teaching; (g) Evaluation; (h) Finance; (i) Governance; (j) Family and Community; (k) Context (Culture, Legal, Demographic). Findings from the study showed that the “common or standard approach” of those responsible for educational quality was to identify quality education indicators by appraising “what is easily accessible, less costly, politically weighty, or recommended by large …organizations,” (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2015, p. 115) rather than to “find systematic, recurring reflective processes that respond to the many distinct aspects of indicator choice,” (p. 115). In the case of educational decision-makers at the school level, pressure to use evaluation tools is compounded by market forces (Burch, 2006) which sometime reveal a circular relationship between textbook publishers and testing companies (Saltman, 2016) and may all but ignore indicators for student success that do not lend themselves to a multiple-choice test (Duckworth et al., 2012). It is notable that educational leaders who prioritize student learning over economic thrift often have long-term payoffs at both the individual student level as well as at a macro level of regional, state or country benefits (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2010, 2015).

Results

Two important findings were made. First, priorities in educational leadership are not the same as priorities in the learning sciences as determined by the way each group frames educational problems or decisions. Second, what is deemed important by society, educational leaders, parents and students related to education may vary and is not always easy to measure.

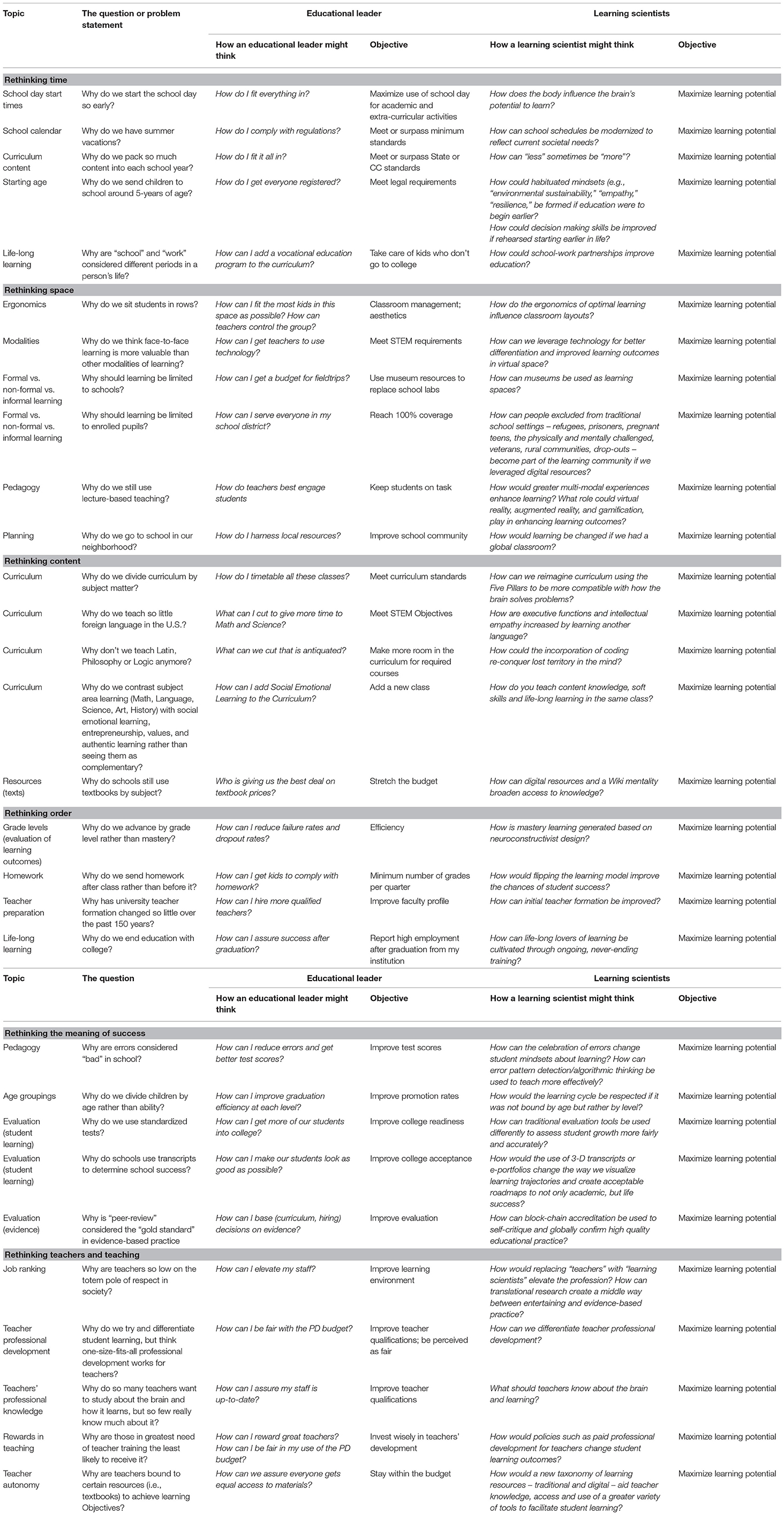

Problem Framing and Articulation

Educational leaders and learning scientists often see similar problems but articulate their research questions differently, leading to distinct ways of both measuring progress toward objectives as well as the choice of appropriate activities. For example, both learning scientists as well as educational leaders are concerned about the curriculum (e.g., Glatthorn et al., 2018; Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2019), the school calendar (e.g., Farbman et al., 2015; Finnie et al., 2018), and teacher training (e.g., Allen and Penuel, 2015; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017), but they approach these issues differently based on the words they use to state their objectives. The literature suggests at least 30 questions for which both educational leaders and learning scientists have conducted research and sought answers (see Table 1). Their approaches, however, were influenced by word choice and heuristics in how they framed the problems.

Table 1. How decisions in education would look if mind, brain, and education scientists ran schools.

Word Choice: Framing Questions to Identify Objectives

Fairhurst's “framing” technique presents problems or challenges as questions (Fairhurst and Sarr, 1996; Fairhurst, 2005). The ways these questions are articulated changes the decision that are reached (O'Keefe, 1988, 1997). For example, asking, “Why do so many minority students drop out of high school?” is different from “Why are Latinos less likely to graduate from high school?” Word choice triggers different heuristics, leading to distinct objectives, leading to different evaluation tools and subsequently, distinct activities.

Table 1 explains 30 different topics in education broken down into six groupings: (a) time; (b) space; (c) content; (d) order; (e) the meaning of “success”; and (f) teachers and teaching. Each table identifies the general topic, followed by a question or problem statement. After this question or problem statement there are two columns, one each for educational leaders and learning scientists. Below each is a question based on actual research studies that may run through the mind of each coupled with its matching objective.

The ways problems are articulated are shaped by at least three factors: (a) vocabulary (Dove, 2014), (b) heuristics and bias (De Martino et al., 2006), and (c) the professional vocabulary of one's field of formation (Loewenstein, 2014). Fairhurst points out that communication style and problem articulation are not merely surface decisions, but rather are deeply seeded in the ontological foundations of different types of thinkers. Because educational leaders and learning scientists frame problems differently, they see different objectives within each category. This results in different priorities in educational improvement initiative, which will be explored in the discussion.

Educational objectives are determined by the way problems are framed (van der Bijl-Brouwer, 2019). The results of the literature review on educational leadership make it clear that educational leaders are challenged by limitations in time and resources and the need to respond to multiple fronts simultaneously (Beyer, 2009). The results of the learning science literature indicate that the transdisciplinary views of “learning” is globally the objective of this field (e.g., Sawyer, 2005b; Fischer et al., 2018).

Identifying Important Problems in Education: Measurable vs. Important

Measurable

A second interesting result was that the literature review revealed that the 217 indicators mentioned in the 2015 study by Tokuhama-Espinosa was an accumulative list of all of the indicators used over a 40-year period by 34 OECD member countries. This means it reported what had been used but did not factor in potential question or problem statements posed by the larger community nor those posed by learning scientists. This suggests a disconnect between educational leaders' decision-making priorities and what both the general public and learning scientists consider worthy of resources.

While the “Top 10 Issues in Education” (Knowles, 2018; Chen, 2019; Rich, 2019) reported in the popular press are for the most part included in the indicators used by the OECD countries to measure quality—including hiring the right people to be teachers in the first place and supporting them to find professional success—some important indicators with a high potential to change educational outcomes were not measured by the OECD countries—such as how early bilingualism improved overall cognition or how later school day start times influenced learning outcomes.

The strong focus on measurable outcomes is rooted in data driven decision-making which prioritizes the quantitative (often short-term) aspects of quality education and often overlooks the qualitative (often long-term) aspects of quality education, which imbalances the evaluation of multiple indicators (Schintler and Kulkarni, 2014). Cost is often a factor in determining measurement indicators; budget restraints may push educational leaders to opt for evaluation tools that that thrifty rather than thorough or important.

Important

For example, school start times appears to have a major impact on student learning outcomes (Perkinson-Gloor et al., 2013) and was labeled important by both the public and by learning scientists but was not included in the list of indicators used to measure quality education. Similarly, the school calendar and specifically the long summer vacation was not mentioned as an indicator for school quality despite the evidence that it has a devastating impact on student learning (Alexander et al., 2007), especially those of lower social-economic background (Gershenson, 2013) who cannot afford to go to camps or other educational experiences (Fairchild and Boulay, 2002).

A third example comes from early childhood education. It has been known for the past 60 years that high quality early childhood education has a lasting impact on student learning outcomes (Pianta et al., 2016). Good early childhood programs also improve self-regulation skills (Montroy et al., 2016), which have greater impact than innate intelligence on academic success (Moffitt et al., 2011). It is also clear that strong early childhood education programs shape good nutritional habits (Schwartz et al., 2011), sleep habits (Cespedes et al., 2014), and social skills (Jones et al., 2015), among others.

A fourth and final example comes from bilingual education. Early biliteracy skills have been shown to mitigate the effects of poverty (Petitto and Dunbar, 2009), yet foreign language and bilingual programs are some of the first courses (along with physical education and the arts) to be cut from educational curricula to make room for more first language and math in order to respond to standardized tests (Crocco and Costigan, 2007). It is ironic that the enhanced executive functions from early bilingualism (Bialystok, 2018) which have a spillover effect in all other subject areas, is eliminated from some schools in order to try and improve learning which would naturally be enhanced by bilingual education.

The decision to choose indicators which are easily measurable over those that may be more important and potentially yield better educational outcomes will be explored in the Discussion section.

Discussion

The analysis and articulation of problems and proposed resolutions differs between educational leaders and learning scientists. While the two may share the initial problem statement, educational leaders and learning scientists relate them to different objectives, and consequently different evaluation methods activities. Setting objectives, deciding on evaluation criteria and choosing appropriate activities (Backward Design planning) take concentration and time (Davidovitch, 2013). Unfortunately school leaders' time-on-task is often spent in administrative meetings (Horng et al., 2010; Lunenburg, 2010) and in some cases, aimed at “putting out fires” or immediate problems in schools (Brauckmann et al., 2015) rather than strategizing on how to articulate and achieve broader learning objectives.

This suggests that the way problems are framed influences perspective-taking changes primarily in one of two ways. Either the understanding and articulation of the problem are changed by the heuristics of the end user (leader or scientist), or the choice of available evaluation tools drives the objective and not the other way around. This implies that there are four possible reasons why educational science has not yet considered itself a learning science: (a) Problem articulation, (b) priorities from the learning sciences not being on educational leaders' agendas, (c) the need to nudge educational leaders into the learning sciences, and (d) no natural access to learning science information on the part of educators. Each will be explained in more detail below.

Why Don't Educational Leaders Think Like Learning Scientists?

The findings suggests that the indicators currently used to make educational decisions by school leaders may be incomplete as they ignore much of the data from the learning sciences. Given the gravity of the stakes—quality education—it is important educational leaders take advantage of all of the information possible to make the best decisions in all areas of responsibility. This means that educational leaders may improve outcomes if they think more like learning scientists. Evidence from the literature indicates that there are at least four contributors as to why educational leaders do not normally consider these high impact decisions. Each of these reasons is followed by a hypothetical solution.

Problem Articulation

Contribution 1

An initial hypothesis as to why educational leaders do not think like learning scientists suggests that the problem is not only systemic in terms of professional access, but that it may also be a problem of semantics. The first contribution is that educational leaders and learning scientists articulate problems differently. That is, when asked, what is the objective? In Backward Design thinking, they would phrase and focus questions and problems with the lenses of their professions, blinding them to different perspectives.

While the use and the steps in Backward Design are the same for business leaders as for educational leaders, business leaders are often facilitated in their objectives by the quantitative nature of problem conception. That is, business goals tend to be less “messy” as they broadly focus on “clean” numbers (Mandinach and Jackson, 2012), whereas educational goals are complicated by multiple human variables. Educational leaders walk a fine line between the business objectives of efficiency, balanced budgets, satisfied workers, and so on, and educational objectives or quality teaching and learning and the human side of education (Daly, 2012).

The professional schizophrenia between efficiency and expediency on the one side and caring human investment on the other also explains why some educational leaders confound variables in decision making. For example, learning scientists know that test scores do not measure intelligence but rather sub-elements of limited aspects of intelligence. The complexities of human intelligence cannot be measured in a single test, no matter how comprehensive (Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2018). Ever since “intelligence” tests were conceived in the 1920s, the objective of improved “student learning outcomes” has used test scores, primarily in math and language, as a proxy for intelligence. Despite multiple detailed arguments to the contrary, the objective (learning) and the evaluation tool (multiple choice tests) do not align as Backward Design would suggest. However, it is very expedient to use a single tool such as a standardized test. Tests are also less costly, which explains why many educational leaders may be convinced of standardized test utility (Gipps, 2011). Mistakes stemming from the articulation of the problem explain why educational leaders and learning scientists reach different conclusions about standardized testing and other key decisions in school settings.

Not on the Radar

Contribution 2

Second, it has been suggested that the lack of attention toward some of the information from the other learning sciences, such as neuroscientific data about school start times or social-anthropological data about school calendars, is because these are not recurrent or annual leadership decisions (Robinson et al., 2008) and are simply not “on the agenda” or “the radar” due to time constraints (Maule et al., 2000). That is, the general day-to-day demands and the wide spectrum of responsibilities of educational leaders does not permit them the time to add in additional decisions that are not regularly attended to.

This could potentially be resolved by calling attention to the importance of these topics and their relatively weighty impact on student learning outcomes, including significant effect sizes reported in recent work by Hattie and Yates (2013) and others. Despite decades of evidence, however, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine suggests in their consensus study report, How People Learn II (2018) that educational leaders may be aware, they just do not prioritize these findings. This leads to a third hypothesis which is at the heart of leadership.

The Need for a Nudge

Contribution 3

Most humans conform to the status quo unless otherwise nudged (Thaler and Sunstein, 2009). Leaders tend to be the people who can do the nudging; however, this can go against some leaders' human nature. Some suggest that the lack of attention to these types of decisions is due to heuristics (Busenitz and Barney, 1997; Hafenbrädl et al., 2016). Humans do not pay attention or question school start times, school calendars, early childhood education policies or bilingual education because they presume if there was an important decision to be made, “everyone” would be talking about doing it (Kim and Gambino, 2016). It takes a truly bold leader to break from the pack and the risk-aversion that accompanies change. Most people are uncomfortable with “rocking the boat” or creating dissonance in the community, and therefore, safe inertia is prized over unstable change (Hayes, 2018).

To compound this challenge, some educational leaders may know about the evidence from the learning sciences but either are unwilling or unable to communicate it to their constituencies or do not have a built-in context through which to facilitate this data. This means that educational inertia is both a sin of inactivity as well as inability. In the first case, the leader is culpable of taking the path of least resistance and ignoring the information. In the second, however, leaders may be willing to try and nudge for change, but they may either not be good enough communicators of the message, or they may be faced with a more articulate resistance. For example, many educational leaders report that their attempts to change school start times or academic calendars was met with push-back from the community who “resisted change.” Rather than “power through” toward successful implementation, they bow to the pressure of a less informed community. Or, if they attempt to rebut the resistance and fail, it may be due to their lack of persuasive dialogue. Leadership requires perseverance as well as good communication (Marques and Dhiman, 2016), characteristics not always present in administrator profiles.

No Natural Access to Information

Contribution 4

A final contribution as to why educational leaders do not think about high-impact decisions as seen by learning scientists is that they are simply unaware they exist. Many from the learning science community believe educational leaders do not access the information or data they need to make decisions (Thomas et al., 2019), possibly because information from the learning sciences is not naturally shared with those in educational leadership (Morris and Sah, 2016).

Information on the learning sciences has slowly become more available to educators, however. Access has improved over the past two decades with the emergence of more frequent high-quality opportunities for professional development such as the International Mind, Brain, and Education conference, the Learning & the Brain conference and educational leaders themselves who seek out professional advice and consulting from learning scientists. The Deans for Impact, a consortium of teacher colleges in the U.S., published a basic guidebook on the learning sciences and motivates educational leader participation in academic programs that bridge administration and knowledge from the learning sciences (2015). New online communities, such as Nature Partner Journal's Science of Learning community and the journals Learning Sciences, Science of Learning, Mind, Brain and Education, and others seek to merge knowledge from educational sciences and other learning sciences such as neuroscience and psychology, for better decision making.

The existence of such resources, however, does not guarantee that educational leaders use them. This means that educational leaders should be more pro-active in exploring the other learning sciences until a natural conduit of information to and from each of the learning sciences is facilitated.

What Would Happen if Educational Leaders Thought More Like Learning Scientists?

These reflections beg the final question: What would happen if educational leaders could be more conscious of their heuristics and how they articulate problems, and consequently attempt to view problems within schools from a learning science perspective?

There have been many shifts in the role of educational leaders over the past 50 years. None perhaps is as challenging as bridging knowledge across disciplines. The slow uptake of information produced in the learning sciences into schools is testament to the complexity of transdisciplinary thinking (Fam et al., 2018). The mental reframing of problems to reflect a broader use of data from all of the learning sciences has the potential to significantly improve education and should, therefore, be considered by educational leaders.

This suggests that educational leaders must ask themselves whether they can see the forest for the trees. That is, what is the real objective of education? For many decades, the cost-effective model (Levin and Belfield, 2015), which has now been fueled by the data-driven model (Meyer et al., 2016), has steered leadership decisions in favor short-term economic indicators rather than long-term learning as the ultimate measure of “quality” and often without considering the roles of all actors involved (Levin and Datnow, 2012). If education is meant to produce human cogs in a societal wheel of progress in an efficient way, then we may already have the perfect system. However, if formal education conducted in schools is meant to maximize the potential of all students to learn, then perhaps we should start thinking more like learning scientists.

Conclusions

This study centered around the research question, How and to what extent does educational science take into consideration information from other learning sciences when making policy decisions? It was determined that policy decisions by educational leaders are complex, broad in their scope and have been studied by many researchers over the years in multiple context and with varying lenses (e.g., Darling-Hammond et al., 2007). Aside from the recommendations from the Deans for Impact (2015), however, the literature review of this study did not reveal consistent or systematic use of data from other learning sciences such as neuroscience by educational leaders. This means that the answer to the original research question is that many educational leaders do not take into consideration much of the information available from the other learning sciences when they make policy decisions, despite its availability. This is due to numerous factors, including problem articulation (semantics, heuristics), not being on educational leaders' radars due to other priority issues which are more familiar, the need for a nudge into the unfamiliar territory of the learning sciences, and that education about the learning sciences is not a “natural” part of educational leaders' typical formation. This clearly points to an explanation as to why educational science has lagged behind other learning sciences, and creates an interesting invitation to do so now.

After considering the results, this study suggests a new research question: Can the learning sciences catalyze a change in educational policy priorities? Which is explained below.

Can the learning sciences catalyze a change in educational policy priorities?

Educational leaders and learning scientists both contribute to the improvement of educational objectives in society but do so from distinct perspectives due to their academic formations and accompanying heuristics. Educational science is a sub-field of the learning sciences, yet few educators consider themselves scientists in this respect. The results of this study suggest that if educational leaders thought more like other learning scientists, priorities in educational policy decisions would change to privilege the important quality indicators in education rather than easily measurable or less costly indicators of student learning outcomes.

Some promising examples have been seen in international schools which have the luxury of applying learning science findings into real school settings. Punahou School's educational leadership team in Hawaii, for example, has made school policies on daily start-times, physical space and ergonomics, transdisciplinary thinking and mastery learning goals, and the planning of social-emotional integration policies a priority (McCaren, personal conversation May 2018) thanks to their learning science decision-making. The International School in Geneva has modified school policies in hopes of ensuring all education contributes to a life-long love of learning by articulating the ways “school” and “work” can and should be integrated (Hawley and David, personal conversation, June 2028). The International School of Bangkok has recently tried “flipping” their leadership meetings (sending video summaries before actually meeting) to leverage time for deeper and more personal exchanges and to make policy decisions after taking advantage of the social aspects of learning (Simmers, personal conversation, October 2019). A recent meta-analysis of K-12 schools that have moved to year-round schooling show modest but positively improved results (Fitzpatrick and Burns, 2019). Glen Whitman at the Center For Transformative Teaching has been training teacher leaders to understand the principles of learning science and to incorporate them into real classroom settings. His school, St. Andrew's Episcopal, assures that “100% of their teachers are trained in Mind, Brain, and Education science” before working with students. The Kamehameha Schools in Hawaii have also recently undergone a 2-year induction into the learning sciences and are now basing policy decisions on the learning sciences (Wong, personal conversation September 2019), including the decision to incorporate early bilingual education (Fields, personal conversation, October 2019).

While these examples are of privileged school systems, they nonetheless point to encouraging examples of better learning science decision making into educational leadership practice. Many of the low to no cost policy changes which rely on new teacher training for professional development possibilities have already been adopted by some teacher colleges (Deans for Impact, 2015) and thousands more educational leaders in the public school systems have been trained in conference formats such as Learning & the Brain and Mind, Brain, and Education (Kelleher and Whitman, 2018) and through programs like “BrainU” at the University of Minnesota (Dubinsky et al., 2013).

To reach the stage where educators begin to think more like learning scientists, several barriers will have to be overcome. Most importantly, access and integration of data from the learning scientists needs to be shared in a more systematic way with educators. Once available, this data must be communicated well to all actors in formal education. This in turn is dependent on broadening educational leaders' perspectives to include the semantics and heuristics of learning scientists, a choice left solely to the leaders themselves. It is also important to remember that the integration of the learning sciences alone will not cure all of the ills facing education. To respond more agilely to the challenges in education, a broader look across not only the learning sciences is needed, but also visionary perspectives from social and economic sciences as well.

Additional research will help advance the discussion around educational leaders in the learning science context. First, more research should be conducted to directly query actors about their views. How do educational leaders feel about the utility of the information coming from the other learning sciences? Do educational leaders consider that data from the learning sciences has a role to play in their decision-making processes, and if so, what is it? Second, there should be additional research as to the specific heuristics and semantics used in the different learning sciences to better understand the historical evolution of communication challenges. Third, more research is needed to identify additional areas that are of mutual concern to educational leaders and to learning scientists. Fourth, it is recommended that collaborative research efforts by educational leaders and learning scientists be conducted in order to cross-pollinate ideas for problem resolution. Such steps can potentially launch a shift in educational leadership and decision-making that is informed by the learning sciences, which would benefit both individuals and their communities.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

TT-E design, applied, summarized, analyzed and wrote the study, and its findings.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the following people for their time and energy toward the generation of this study, the lively debate and the on-going commitment to better educational practices. Thanks to the following for participating in the Delphi survey, offering to review findings, recommending panelists and/or for words of encouragement: Doris Alvarez, Eliot Berkman, Virginia Berninger, Jane Bernstein, Jeffrey Bowers, John T. Bruer, David Daniel, Bert DeSmedt, Stanislas Dehaene, Phil Fisher, Uta Frith, Howard Gardner, Walter Glannon, Ezequiel Gleichgerrcht, Usha Goswami, Ronald H. Grabner, Sonia Guerreiero, Mariale Hardinman, Takao Hensch, Paul Howard-Jones, Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, Jelle Jolles, Mary Layne Kalbfleisch, Johannes König, Iveta Kovalčíková, Abigail Larrison, Marilyn Leaske, Gigi Luk, Susan Magsamen, Pedro Maldonado, Richard Mayer, Bruce McCandliss, Renata Meneces, John Morrison, Eric Pakulak, Michael Posner, Sidarta Ribeiro, Vanessa Rodriguez, Todd Rose, Pankaj Sah, Daniel Schwartz, Jack Shonkoff, Beate Sodian, Elsbeth Stern, Michael Thomas, Nienke van Atteveldt, Judy Willis, and Patricia Wolfe. Thanks to Thomas Gorham, Julia Volkman, Juad Masters, Drew Nelson, Robert Murphy, and Curtis Kelly for their enthusiasm for this project and to Dee Rutgers for keeping me on a writing schedule.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2019.00136/full#supplementary-material

References

Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R., and Olson, L. S. (2007). Lasting consequences of the summer learning gap. Am. Sociol. Rev. 72, 167–180. doi: 10.1177/000312240707200202

Allen, C. D., and Penuel, W. R. (2015). Studying teachers' sensemaking to investigate teachers' responses to professional development focused on new standards. J. Teach. Educ. 66, 136–149. doi: 10.1177/0022487114560646

Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., and Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 30, 1–34. doi: 10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

Aloe, A. M., Amo, L. C., and Shanahan, M. E. (2014). Classroom management self-efficacy and burnout: a multivariate meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 26, 101–126. doi: 10.1007/s10648-013-9244-0

Amanchukwu, R. N., Stanley, G. J., and Ololube, N. P. (2015). A review of leadership theories, principles and styles and their relevance to educational management. Management 5, 6–14. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20150501.02

Anderson, M. (2018). Transformational leadership in education: a review of existing literature. Int. Soc. Sci. Rev. 93, 4. Available online at: http://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/issr/vol93/iss1/4

Angelle, P., and Teague, G. M. (2014). Teacher leadership and collective efficacy: teacher perceptions in three US school districts. J. Educ. Administr. 52, 738–753. doi: 10.1108/JEA-02-2013-0020

Beck, L. G. (1994). Reclaiming Educational Administration as a Caring Profession. Critical Issues in Educational Leadership Series. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Beck, L. G., and Murphy, J. (1994). Ethics in Educational Leadership Programs: An Expanding Role. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, Inc.

Bektas, F., Çogaltay, N., Karadag, E., and Ay, Y. (2015). School culture and academic achievement of students: a meta-analysis study. Anthropologist 21, 482–488. doi: 10.1080/09720073.2015.11891837

Belfield, C. R., and Brooks Bowden, A. (2019). Using resource and cost considerations to support educational evaluation: six domains. Educ. Res. 48, 120–127. doi: 10.3102/0013189X18814447

Beyer, B. (2009). An imperative for leadership preparation programs: preparing future leaders to meet the needs of students, schools, and communities. Int. J. Educ. Leaders. Prepar. 4:n1. Available online at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Bialystok, E. (2018). “Bilingualism and executive function,” in Bilingual Cognition and Language: The State of the Science Across Its Subfields, Vol. 54, eds D. Miller, F. Bayram, J. Rothman, and L. Serratrice (Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 283. doi: 10.1075/sibil.54.13bia

Blank, R. K., and De Las Alas, N. (2009). The Effects of Teacher Professional Development on Gains in Student Achievement: How Meta Analysis Provides Scientific Evidence Useful to Education Leaders. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers.

Bogotch, I. E. (2002). Educational leadership and social justice: practice into theory. J. Sch. Leaders. 12, 138–156. doi: 10.1177/105268460201200203

Boyce, J., and Bowers, A. J. (2018). Toward an evolving conceptualization of instructional leadership as leadership for learning: meta-narrative review of 109 quantitative studies across 25 years. J. Educ. Administr. 56, 161–182. doi: 10.1108/JEA-06-2016-0064

Brauckmann, S., Thiel, F., Kuper, H., Tarkian, J., and Schwarz, A. (2015). No time to manage? The trade-off between relevant tasks and actual priorities of school leaders in Germany. Int. J. Educ. Manage. 29, 49–765. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-10-2014-0138

Broudy, H. S. (1962). To regain educational leadership. Stud. Philos. Educ. 2, 132–158. doi: 10.1007/BF00375919

Bryant, P., Butcher, J. T., and O'Connor, J. (2016). Improving school leadership: the connection of transformational leadership and psychological well-being of the followers. Sch. Leaders. Rev. 11:6. Available online at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol11/iss2/6

Burch, P. E. (2006). The new educational privatization: educational contracting and high stakes accountability. Teach. Coll. Rec. 108, 2582–2610. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00797.x

Buros, O. K. (1977). Fifty years in testing: some reminiscences, criticisms, and suggestions. Educ. Res. 6, 9–15. doi: 10.3102/0013189X006007009

Busenitz, L. W., and Barney, J. B. (1997). Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making. J. Bus. Vent. 12, 9–30. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(96)00003-1

Cameron, W. B. (1963). Informal Sociology: A Casual Introduction to Sociological Thinking, Vol. 21. New York, NY: Random House.

Celio, C. I., Durlak, J., and Dymnicki, A. (2011). A meta-analysis of the impact of service-learning on students. J. Exp. Educ. 34, 164–181. doi: 10.1177/105382591103400205

Cespedes, E. M., Gillman, M. W., Kleinman, K., Rifas-Shiman, S. L., Redline, S., and Taveras, E. M. (2014). Television viewing, bedroom television, and sleep duration from infancy to mid-childhood. Pediatrics 133, e1163–e1171. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3998

Chen, G. (2019, February 21). 10 major challenges facing public schools. Public School Review [blog]. Retrieved from: https://www.publicschoolreview.com/blog/10-major-challenges-facing-public-schools (accessed July 24, 2019).,

Cheong Cheng, Y., and Ming Tam, W. (1997). Multi-models of quality in education. Qual. Assur. Educ. 5, 22–31. doi: 10.1108/09684889710156558

Coe, R., and Fitz-Gibbon, C. T. (1998). School effectiveness research: criticisms and recommendations. Oxford Rev. Educ. 24, 421–438. doi: 10.1080/0305498980240401

Crocco, M. S., and Costigan, A. T. (2007). The narrowing of curriculum and pedagogy in the age of accountability urban educators speak out. Urban Educ. 42, 512–535. doi: 10.1177/0042085907304964

Daly, A. J. (2012). Data, dyads, and dynamics: Exploring data use and social networks in educational improvement. Teach. Coll. Rec. 114, 1–38. Available online at: http://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentId=16811

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., and Gardner, M. (2017). Effective Teacher Professional Development. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

Darling-Hammond, L., LaPointe, M., Meyerson, D., Orr, M. T., and Cohen, C. (2007). Preparing School Leaders for a Changing World: Lessons from Exemplary Leadership Development Programs. School Leadership Study. Final Report. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Educational Leadership Institute.

Darling-Hammond, L., Wei, R. C., Andree, A., Richardson, N., and Orphanos, S. (2009). Professional Learning in the Learning Profession. Washington, DC: National Staff Development Council, 12.

Davidovitch, N. (2013). Learning-centered teaching and backward course design from transferring knowledge to teaching skills. J. Int. Educ. Res. 9, 329–338. doi: 10.19030/jier.v9i4.8084

Day, C., Gu, Q., and Sammons, P. (2016). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: how successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educ. Administr. Q. 52, 221–258. doi: 10.1177/0013161X15616863

Day, C., and Sammons, P. (2013). Successful Leadership: A Review of the International Literature. Reading: CfBT Education Trust.

De Martino, B., Kumaran, D., Seymour, B., and Dolan, R. J. (2006). Frames, biases, and rational decision-making in the human brain. Science 313, 684–687. doi: 10.1126/science.1128356

Devine, J. F., and Cohen, J. (2007). Making Your School Safe: Strategies to Protect Children and Promote Learning. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

DiPaola, M., and Hoy, W. K. (Eds.). (2015). Leadership and School Quality. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishers.

Dolton, P., and Marcenaro-Gutierrez, O. D. (2016). How to Get the Best Bang for Oyur Buck: The Relative Efficiency of Educational Systems: A Cross Country Prescriptive Analysis. Sussex: University of Sussex.

Dove, G. (2014). Thinking in words: language as an embodied medium of thought. Top. Cogn. Sci. 6, 371–389. doi: 10.1111/tops.12102

Dubinsky, J. M., Roehrig, G., and Varma, S. (2013). Infusing neuroscience into teacher professional development. Educ. Res. 42, 317–329. doi: 10.3102/0013189X13499403

Duckworth, A. L., Quinn, P. D., and Tsukayama, E. (2012). What no child left behind leaves behind: the roles of IQ and self-control in predicting standardized achievement test scores and report card grades. J. Educ. Psychol. 104, 439–451. doi: 10.1037/a0026280

Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., and Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. J. Manage. 38, 1715–1759. doi: 10.1177/0149206311415280

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., and Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 82, 405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., and Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 45, 294–309. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9300-6

Elbertson, N. A., Brackett, M. A., and Weissberg, R. P. (2010). “School-based social and emotional learning (SEL) programming: current perspectives,” in Second International Handbook of Educational Change, eds A. Hargreaves, A. Lieberman, M. Fullan, and D. Hopkins (Dordrecht: Springer), 1017–1032. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2660-6_57

Elias, M. J. (2009). Social-emotional and character development and academics as a dual focus of educational policy. Educ. Policy 23, 831–846. doi: 10.1177/0895904808330167

Epstein, J. L. (2018). School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Preparing Educators and Improving Schools. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429493133

Fairchild, R., and Boulay, M. (2002). “What if summer learning loss were an education policy priority,” in Presentation for the 24th Annual APPAM Research Conference, Vol. 9. Baltimore, MD.

Fairhurst, G. T. (2005). Reframing the art of framing: problems and prospects for leadership. Leadership 1, 165–185. doi: 10.1177/1742715005051857

Fairhurst, G. T., and Sarr, R. A. (1996). The Art of Framing: Managing the Language of Leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/53.21.2670

Fam, D., Neuhauser, L., and Gibbs, P. (Eds.). (2018). Transdisciplinary Theory, Practice and Education: The Art of Collaborative Research and Collective Learning. New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-93743-4

Farbman, D., Davis, J., Goldberg, D., and Rowland, J. (2015). Learning Time in America: Trends to Reform the American School Calendar: A Snapshot of Federal, State and Local Action. Washington, DC: Education Commission of the States.

Finnie, R. K., Peng, Y., Hahn, R. A., Johnson, R. L., Fielding, J. E., Truman, B. I., et al. (2018). Examining the effectiveness of year-round school calendars on improving educational attainment outcomes within the context of advancement of health equity: a community guide systematic review. J. Pub. Health Manage. Pract. 25:1. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000860

Fischer, F., Hmelo-Silver, C. E., Goldman, S. R., and Reimann, P. (Eds.). (2018). International Handbook of the Learning Sciences. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315617572

Fischer, K., Daniel, D., Immordino-Yang, M.-H., Stern, E., Battro, A., and Koizumi, H. (2007). Why mind, brain, and education? Why now. Mind Brain Educ. 1, 1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00006.x

Fitzpatrick, D., and Burns, J. (2019). Single-track year-round education for improving academic achievement in US K-12 schools: results of a meta-analysis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 15:e1053. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1053

Gayle, B. M., Preiss, R. W., Burrell, N., and Allen, M. (2009). Classroom Communication and Instructional Processes: Advances Through Meta-Analysis. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203933145

Gershenson, S. (2013). Do summer time-use gaps vary by socioeconomic status? Am. Educ. Res. J. 50, 1219–1248. doi: 10.3102/0002831213502516

Gipps, C. (2011). Beyond Testing: Towards a Theory of Educational Assessment. New York, NY: Routledge.

Glatthorn, A. A., Boschee, F., Whitehead, B. M., and Boschee, B. F. (2018). Curriculum Leadership: Strategies for Development and Implementation. New York, NY: Sage publications.

Grace, G. (2005). School Leadership: Beyond Education Management. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203974780

Grissom, J. A., Loeb, S., and Master, B. (2013). Effective instructional time use for school leaders: Longitudinal evidence from observations of principals. Educ. Res. 42, 433–444. doi: 10.3102/0013189X13510020

Grogan, M., and Shakeshaft, C. (2010). Women and Educational Leadership, Vol. 10. Nebraska: University of Nebraska by Wiley.

Guerriero, S. (Ed.). (2017). Pedagogical Knowledge and the Changing Nature of the Teaching Profession. Paris: OECD. doi: 10.1787/9789264270695-en

Gumus, S., Bellibas, M. S., Esen, M., and Gumus, E. (2018). A systematic review of studies on leadership models in educational research from 1980 to 2014. Educ. Manage. Administr. Leaders. 46, 25–48. doi: 10.1177/1741143216659296

Gurley, D. K., Anast-May, L., O'Neal, M., and Dozier, R. (2016). Principal instructional leadership behaviors: Teacher vs. self-perceptions. Int. J. Educ. Leaders. Prepar. 11:n1. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1103651.pdf

Hafenbrädl, S., Waeger, D., Marewski, J. N., and Gigerenzer, G. (2016). Applied decision making with fast-and-frugal heuristics. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 5, 215–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jarmac.2016.04.011

Hallinger, P. (2011). Leadership for learning: Lessons from 40 years of empirical research. J. Educ. Administr. 49, 125–142. doi: 10.1108/09578231111116699

Hallinger, P. (2014). Reviewing reviews of research in educational leadership: an empirical assessment. Educ. Administr. Q. 50, 539–576. doi: 10.1177/0013161X13506594

Hallinger, P., and Heck, R. H. (1996). Reassessing the principal's role in school effectiveness: a review of empirical research, 1980-1995. Educ. Administr. Q. 32, 5–44. doi: 10.1177/0013161X96032001002

Hallinger, P., and Heck, R. H. (1998). Exploring the principal's contribution to school effectiveness: 1980-1995. School Effecti. Sch. Improv. 9, 157–191. doi: 10.1080/0924345980090203

Hallinger, P., Wang, W. C., and Chen, C. W. (2013). Assessing the measurement properties of the principal instructional management rating scale: a meta-analysis of reliability studies. Educ. Administr. Q. 49, 272–309. doi: 10.1177/0013161X12468149

Hallinger, P., Wang, W. C., Chen, C. W., and Liare, D. (2015). Assessing Instructional Leadership with the Principal Instructional Management Rating Scale. Dordrecht: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-15533-3

Hammond, M. M., Neff, N. L., Farr, J. L., Schwall, A. R., and Zhao, X. (2011). Predictors of individual-level innovation at work: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 5, 90–105. doi: 10.1037/a0018556

Hanushek, E. A., and Woessmann, L. (2010). Education and economic growth. Econom. Educ. 8, 50–67. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.01227-6

Hanushek, E. A., and Woessmann, L. (2015). The Knowledge Capital of Nations: Education and the Economics of Growth. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/9780262029179.001.0001

Harvey, L., and Newton, J. (2004). Transforming quality evaluation. Qual. High. Educ. 10, 149–165. doi: 10.1080/1353832042000230635

Hattie, J., and Yates, G. C. (2013). Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315885025

Hauge, T. E., Norenes, S. O., and Vedøy, G. (2014). School leadership and educational change: tools and practices in shared school leadership development. J. Educ. Change 15, 357–376. doi: 10.1007/s10833-014-9228-y

Hayes, J. (2018). The Theory and Practice of Change Management. Hampshire,: Palgrave. doi: 10.1057/978-1-352-00132-7

Heck, R. H., and Hallinger, P. (2005). The study of educational leadership and management: where does the field stand today? Educ. Manag. Administr. Leaders. 33, 229–244. doi: 10.1177/1741143205051055

Horng, E. L., Klasik, D., and Loeb, S. (2010). Principal's time use and school effectiveness. Am. J. Educ. 116, 491–523. doi: 10.1086/653625

Jackson, B. L., and Kelley, C. (2002). Exceptional and innovative programs in educational leadership. Educ. Administr. Q. 38, 192–212. doi: 10.1177/0013161X02382005

Jackson, K. M., and Marriott, C. (2012). The interaction of principal and teacher instructional influence as a measure of leadership as an organizational quality. Educ. Administr. Q. 48, 230–258. doi: 10.1177/0013161X11432925

James, A. (2015). “Is education really underfunded in resource-rich economies? Evidence from a panel of US states,” in Working Papers 2015-01 (Ancorage, AL: University of Alaska Anchorage, Department of Economics).

Jones, D. E., Greenberg, M., and Crowley, M. (2015). Early social-emotional functioning and public health: the relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. Am. J. Pub. Health 105, 2283–2290. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302630

Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Ilies, R., and Gerhardt, M. W. (2002). Personality and leadership: a qualitative and quantitative review. J. Appl. Psychol. 87, 765–780. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.765

Kelleher, I., and Whitman, G. (2018). A bridge no longer too far: a case study of one school's exploration of the promise and possibilities of mind, brain, and education science for the future of education. Mind Brain Educ. 12, 224–230. doi: 10.1111/mbe.12163

Kim, J., and Gambino, A. (2016). Do we trust the crowd or information system? Effects of personalization and bandwagon cues on users' attitudes and behavioral intentions toward a restaurant recommendation website. Comput. Hum. Behav. 65, 369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.08.038

Knowles, E. (2018). Current Educational Issues. Leeds: University of Leeds. Retrieved from: https://www.prospects.ac.uk/jobs-and-work-experience/job-sectors/teacher-training-and-education/current-educational-issues (accessed July 24, 2019).,

Knox, J. A., and Anfara, V. A. Jr (2013). Understanding job satisfaction and its relationship to student academic performance. Middle Sch. J. 44, 58–64. doi: 10.1080/00940771.2013.11461857

Lambert, M., and Bouchamma, Y. (2019). Leadership requirements for school principals: similarities and differences between four competency standards. Can. J. Educ. Administr. Policy 188, 53–68. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1211689.pdf

Leithwood, K. (2012). The Ontario Leadership Framework 2012. Institute for Education Leadership. Retrieved from: https://www.education-leadership-ontario.ca/application/files/2514/9452/5287/The_Ontario_Leadership_Framework_2012_-_with_a_Discussion_of_the_Research_Foundations.pdf. (accessed November 20, 2019).

Leithwood, K., and Jantzi, D. (2008). Linking leadership to student learning: the contributions of leader efficacy. Educ. Administr. Q. 44, 496–528. doi: 10.1177/0013161X08321501

Levin, H. M., and Belfield, C. (2015). Guiding the development and use of cost-effectiveness analysis in education. J. Res. Educ. Effect. 8, 400–418. doi: 10.1080/19345747.2014.915604

Levin, J. A., and Datnow, A. (2012). The principal role in data-driven decision making: using case-study data to develop multi-mediator models of educational reform. School Effect. Sch. Improv. 23, 179–201. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2011.599394

Liebowitz, D. D., and Porter, L. (2019). The effect of principal behaviors on student, teacher, and school outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 89, 785–827. doi: 10.3102/0034654319866133

Lockton, D., Harrison, D., Cain, R., Stanton, N., and Jennings, P. (2013). Exploring problem-framing through behavioral heuristics. Int. J. Design 7, 37–53. Available online at: http://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/1291/1/Lockton%20Exploring%20Problem-Framing%20Through%20Behavioural%20Heuristics%202013.pdf

Loewenstein, J. (2014). Take my word for it: How professional vocabularies foster organizing. J. Profess. Org. 1, 65–83. doi: 10.1093/jpo/jot004

Lomos, C., Hofman, R. H., and Bosker, R. J. (2011). Professional communities and student achievement–a meta-analysis. Sch. Effect. Sch. Improv. 22, 121–148. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2010.550467

Lunenburg, F. C. (2010). The principal and the school: what do principals do? in National Forum of Educational Administration & Supervision Journal, Vol. 27. Washington, DC.

Madaus, G. F., and Stufflebeam, D. L. (Eds.). (1988). Educational Evaluation: Classic Works of Ralph W. Tyler. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. doi: 10.1007/978-94-009-2679-0

Mandinach, E. B., and Jackson, S. S. (2012). Transforming Teaching and Learning Through Data-Driven Decision Making. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press). doi: 10.4135/9781506335568

Marques, J., and Dhiman, S. (Eds.). (2016). Leadership Otday: Practices for Personal and Professional Performance. New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.4324/9781315695662

Maule, A. J., Hockey, G. R. J., and Bdzola, L. (2000). Effects of time-pressure on decision-making under uncertainty: changes in affective state and information processing strategy. Acta Psychol. 104, 283–301. doi: 10.1016/S0001-6918(00)00033-0

McKenney, S. (2018). How can the learning sciences (better) impact policy and practice? J. Learn. Sci. 1, 1–7. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2017.1404404

Meyer, E., Cahill, M., Subramaniam, M., and Stripling, B. (2016). “The promise and peril of learning analytics in P-12 education: an uneasy partnership?,” in IConference 2016 Proceedings. doi: 10.9776/16518. Available online at: https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/89459/Meyer518.pdf?sequence=1

Mills, L. B. (2009). A meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and effective leadership. J. Curric. Instr. 3:22. doi: 10.3776/joci.2009.v3n2p22-38

Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., et al. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 2693–2698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010076108

Montroy, J. J., Bowles, R. P., Skibbe, L. E., McClelland, M. M., and Morrison, F. J. (2016). The development of self-regulation across early childhood. Dev. Psychol. 52, 1744–1762. doi: 10.1037/dev0000159

Moriano, J. A., Molero, F., Topa, G., and Mangin, J. P. L. (2014). The influence of transformational leadership and organizational identification on intrapreneurship. Int. Entrepr. Manage. J. 10, 103–119. doi: 10.1007/s11365-011-0196-x

Morris, J., and Sah, P. (2016). Neuroscience and education: mind the gap. Austr. J. Educ. 60, 146–156. doi: 10.1177/0004944116652913

Murphy, J., Elliott, S. N., Goldring, E., and Porter, A. C. (2006). Learning-Centered Leadership: A Conceptual Foundation. Nashville, TN: Learning Sciences Institute, Vanderbilt University (NJ1).