94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 26 March 2019

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 4 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00022

This article is part of the Research TopicMentoring and Crossing the Theory/Practice DivideView all 3 articles

Preparing pre-service teachers to become effective future educators has become increasingly complex in an environment of rapid change, economic uncertainty, technological advancements, and cultural diversity. Contemporary initial teacher education is evolving and adapting to the changing organizational environments and cultures in organizations who partner in equipping pre-service teachers to become knowledgeable, innovative, and professional in their teaching and skilled in effectively connecting, interacting, and collaborating in professional communities. Professional experience placements provide pre-service teachers with the opportunity to participate in teaching in real-world settings guided by experienced teachers and supported by university supervisors; however, the diverse approaches to professional experience adopted by educational organizations, influence pre-service teachers' experiences, and outcomes. Cultural and socio-economic factors across different sites also impact on the outcomes of students' professional experience due to variations in the organizational culture and settings. In this paper we explore the evolution of professional experience from traditional to contemporary, the role of the third space in professional experience, and the complexities in developing a unified approach in universities and early childhood sites/schools, organizations that have very different cultures yet are committed to developing effective teachers. We highlight the advantages of adopting a learning community model for professional experience in which mentoring is central to success. A theory-based model of professional experience, 3PEx, based on a learning community approach and the merging of cultures in professional experience and learning contexts, is introduced. This model is informed by the literature and results of a recent study of professional experience in a university reimagining initial teacher education to meet contemporary standards. The challenges of achieving cultural change in the professional experience arena are explored, and a range of strategies suggested that can lead to a deeper understanding of the cultural landscape and the needs of pre-service teachers in their transition to teaching.

The evolution of pre-service teacher education and professional experience over the last two decades is linked with a vast number of changes in teaching and learning approaches, educational technologies and innovative learning design, and is influenced by the development of new educational policy and quality standards established to meet the expectation of high quality graduates (Darling-Hammond, 2006; McLoughlin and Nagabhushan, 2014; Adamson and Darling-Hammond, 2015; Le Cornu, 2015). Teacher education currently takes place in a complex ever-changing environment that is affected by policy reform, recurrent organizational restructuring, increased cultural diversity in the population and growing economic pressures (Stephenson and Ling, 2014; Fitzgerald and Knipe, 2016). However, recent changes have also created opportunities for enhancing the learning experience with technological advancements expanding communication, interaction, and providing an abundance of resources and prospects for authentic learning and creativity in learning and teaching (Andreas, 2015; Adams Becker et al., 2017; Freeman et al., 2017; EDUCAUSE, 2018). When organizational environments change, consequently this also brings changes to both school and university cultures and the professional communities in which pre-service teachers interact to develop their capabilities as teachers (Ingvarson et al., 2014; Masters, 2016).

Professional experience placements are a key aspect of pre-service teachers' preparation for teaching while completing university-based teacher education courses. These authentic experiences give students opportunities to engage in teaching in real-world school settings with the guidance and support of mentor-teachers, peer mentors, and university supervisors. In the professional experience setting, pre-service teachers first encounter the differences in how educational organizations, universities, schools, and prior to school settings, approach professional experience noting divergences in the organizational cultures, variations in socio-economic and cultural settings, and contrasts in the backgrounds of pre-service teachers, school and university staff, and the learners in the schools (Rowan et al., 2017). Professional experience is also influenced by a wide range of factors dictated by organizations, through their philosophical approaches to professional experience and their specific settings and cultures, but likewise by the factors that vary for each pre-service teacher such as their own cultural make-up defined by their background, past experience, motivations, and expectations. The combined impact of all of these factors can influence pre-service teachers' outcomes and therefore a deeper understanding of the cultural landscape in the school settings can provide student teachers with an awareness and adaptability that will assist them in the transition to the workplace (Reese, 2012).

In a time where university-based teacher educators are challenged by competing priorities related to research expectations and teaching workloads, the need to strengthen the professional experience partnerships in programs can be challenging. Changing the culture toward contemporary professional experience and the role of mentoring and peer mentoring is explored in this paper. Finally, a conceptual model of the Third Space in Professional Experience (3PEx), informed by the literature, is provided which illustrates the complex interplay of factors in professional experience settings.

The literature on professional experience documents a gradual evolution from traditional apprenticeship approaches to more contemporary models of professional experience (Le Cornu and Ewing, 2008; Le Cornu, 2016a). However, the extent of change from traditional to contemporary requires both philosophical and cultural shifts in our institutions and a common understanding and unified approach for a way forward appears to be elusive, particularly as much of the professional experience takes place in what has been described as the “third space” and the challenges extend beyond university and schools (Williams, 2014).

The literature refers to a wide range of approaches to professional experience with different rationales, goals, and activities (Cohen et al., 2013; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Payne and Zeichner, 2017). Le Cornu and Ewing (2008) have reviewed the multitude of professional experience approaches and identified three main orientations to professional experience: (1) the Traditional Teaching Practice Model, (2) the Reflective Teaching Practicum Model, and (3) the Learning Community Professional Experience Model, as described below.

The traditional model, described as a “teaching practice model,” where the focus is mainly on acquiring technical teaching skills with students observed by practice supervisors (experienced, practicing teachers). In this model, theory components are acquired at university and practice teaching occurs in schools and supervisors assess pre-service teachers' progress. Traditional approaches to professional experience, as described by Zeichner (1983, p. 5), follow a behavioristic master-apprentice paradigm where good teachers transmit “cultural knowledge” to novice pre-service teachers. In the traditional approaches, professional experience aims to provide a bridge between theory and practice and pre-service teachers are required to master technical skills of teaching and develop skills in instruction (Le Cornu and Ewing, 2008). However, research has shown that the traditional approaches to professional experience generally provide insufficient integration of theory and practice and have been criticized for resulting in a lack of classroom readiness in early career teachers (Zeichner, 1990; Brady et al., 1998; Korthagen and Kessels, 1999; Allen, 2009; Grudnoff, 2011; Allen and Wright, 2014; Craven et al., 2014).

The reflective model is usually found in the form of the “teaching practicum,” with a focus on professional decision-making and providing opportunities for reflection on practice (Zeichner, 1990, 1992). This approach promotes constructivist views on learning and teaching and can be described as a practice mentoring model where pre-service teachers are guided by practice supervisor-mentors.

The reflective model moves beyond attaining technical skills in the master-apprentice model to a more holistic approach to teaching including the consideration of different social contexts and the moral and ethical challenges in teaching, with a move away from the hierarchical supervising power structure present in traditional model thus giving the students more autonomy and control of their learning experience (Le Cornu and Ewing, 2008). In this model pre-service teachers are required to engage in deep reflection, not only about their teaching and teaching strategies, but on wider educational issues including consideration of their own beliefs and practices and the institutional and social context of learning (Dobbins, 1996a).

The learning communities model is guided by constructivist theories and is conceptualized as professional experience where all parties collaborate to achieve the required outcomes by engaging in reciprocal working and learning relationships with pre-service teachers, colleagues and peers, mentor-teachers, and university teacher educators with the focus on sharing and collaborating to achieve optimal outcomes for all (White et al., 2010). The learning communities model, informed by the work of Lave and Wenger (1991) and Wenger (1998), builds on the reflective model extending it from an individual focus to a shared community focus where pre-service teachers participate in a collaborative and supportive community of learners acknowledging the collaborative nature of the teaching profession (Le Cornu and Ewing, 2008). A shared community focus would ideally be underpinned by the presence of a Community of Practice (CoP). Wenger (1998) describes three key dimensions of CoP which include: (1) mutual engagement, formed by working together and developing a sense of belonging, (2) joint enterprise involving a common purpose and shared community values and visions, and (3) a shared repertoire through negotiating a shared purpose, goals, and accountability. According to Johnson et al. (2015) it is important for a learning community to build a culture of belonging which promotes a sense of belonging and social connectedness in its participants. The key to achieving such a sense of community is through authorities, school leaders, and communities developing strategies that:

• Practice affirmation;

• Recognize and value diverse perspectives, practices, and backgrounds;

• Foster trust and goodwill;

• Minimize isolation; and

• Take collective responsibility for teacher well-being and safety (Johnson et al., 2015, p. 57).

The Learning Community can also include influences beyond those directly associated with university and teaching such as the wider community and service organizations (Harfitt, 2018); however, this was beyond the scope of the study on which the 3PEx model is based and therefore excluded from the model at this time.

The implementation of a learning community model in professional experience can vary in structure and practices according to White et al. (2010) but at the center of this model is the formation of collaborative “learning partnerships” with reciprocal working and learning relationships involving teacher educators, mentor-teachers and other educational site staff, and establishing peer support and mentoring learning partnerships with other pre-service teachers. Peer mentoring can be achieved through the formation of face to face “learning circles” or social media groups in which pre-service teachers engage in a professional dialogue and share their learning experiences. White et al. (2010) suggest that such partnerships encourage reflection and help in developing resilience with pre-service teachers becoming more responsible for their own learning and also for contributing to the learning of their peers. The learning community model also involves the strengthening of partnerships at the school-university level with more collaboration and better working relationships. The boundaries of a learning community can also vary. For example, for some higher education institutions (HEIs) the definition of community extends beyond the university and school/early childhood site settings with pre-service teachers engaging in service learning and experiential learning with work experience or field placements in non-governmental community organizations designed to broaden pre-service teachers' horizons and provide greater awareness in areas such as literacy and literacy pedagogy (Brayko, 2013; Harfitt, 2018).

The Reflective and Learning Community professional experience models can be considered the contemporary ideals in professional experience; however, for many institutions these are still aspirational models with elements of reflection and learning communities being implemented in professional experience settings that are mostly traditional in philosophies and operational processes. Changes to initial teacher education and professional experience design cannot be done in isolation and must be done as a collaborative endeavor involving the partner institutions and the teaching and support staff (Grudnoff, 2011). The concept of Professional Development Schools (PDS), as described by Darling-Hammond (2014), can serve as an example of an implementation of the learning community professional experience model as PDSs endeavor to implement strong models of practice and collaboration sharing cultural norms and practices to advance both teaching and educational research.

However, the challenges in adopting new practices in professional experience are multifaceted involving changes not only at institutional levels, but also in the culture of the workplaces and in the learning community, where much is quite intangible, unformalized, and occurring in the “Third Space” in teacher education as discussed in the next section.

Traditionally, initial teacher education for pre-service teachers was assumed to take place in two spaces: the formal teaching environment at university or college and the professional experience placement sites within the school/early childhood environment. However, a number of educators (Cuenca et al., 2011; Williams, 2013, 2014; McDonough, 2014) have adopted Bhabha's concept of the “third space” (Bhabha, 1990) to describe and identify a third space in pre-service teacher education, the space in which pre-service teachers work with professional experience supervisors, teachers/mentors, and others negotiating complex multidimensional relationships (e.g., pre-service teacher and school teacher, pre-service teacher, and professional experience university supervisor, pre-service teacher, and students/children in their classes) within institutional learning environments that may have profoundly different working cultures and physical environments. According to Sinclair et al. (2005) pre-service teachers negotiate through “multiple realities” while on professional experience where they reconcile the differences between university and school, and theory and practice and negotiate through their preferred realities of teaching and what is actually possible in practice.

In effect, a merging of cultures in contemporary professional experience takes place in this third space where university, school, and related communities (students, parents, and wider community) meet and the organizational cultures, individual, and community cultures overlap. Williams (2014) highlights the challenges faced by university-based teacher educators (university supervisors) in the third space between universities and schools/early childhood sites while supervising and mentoring pre-service teachers and working with site-based supervisor/mentoring teachers. In these complex environments with changing perspectives on learning and teaching one of the main challenges is the negotiation of problematic and finely balanced relationships. According to Williams (2014, p. 4) there are three essential dimensions of teacher educator learning and practice in the third space including: “(a) managing shifting conceptions of their professional identities as teachers and teacher educators, (b) identifying changing perspectives on teaching and learning, and (c) negotiating complex and sometimes difficult professional relationships.”

To support the theory-based notion of the third space in professional experience settings, Williams (2014) draws on the work of Engeström (2004) who, with an activity theory perspective on learning, describes the horizontal movement between sites of professional practice with learning taking place at each site and in the “in between space” where the two sites overlap and interact resulting in the formation of “hybrid solutions” based on negotiations taking place in each context and the shared space (Engeström et al., 1995). The complexity of the required negotiation in the third space is further highlighted by Korthagen et al. (2006) who propose that the teacher educator (University Supervisor) holds three different perspectives simultaneously: that of the pre-service teacher, the supervisor/mentor teacher, and the teacher educator. The supervising educator needs to reconceptualize their own identity to act as a mentor, rather than an expert who offers solutions, as their role is to guide pre-service teachers toward finding context specific solutions and developing their own decision-making skills.

Taylor et al. (2014) also describe the need for continual negotiation and reflection by teacher educators working in the dynamic third space environments of pre-service teacher education where developing collaborative relationships with teachers is essential to facilitate reciprocal teaching and learning. Similarly, McDonough (2014) documents the tensions of working in the third space as a teacher educator and working in a hybrid role encompassing multiple identities including that of a teacher, supervisor and mentor. Common elements recognized in the literature are descriptions of the complexity, messiness and continually adapting environments and interactions in the third space of teacher education which require educators to experiment, take risks, and transform their practice.

The range of cultural challenges awaiting pre-service teachers in practice are diverse and may depend on the location and demographics of schools. A recent study by Rowan et al. (2017, p. 87) identified that early career teachers in Australian contexts were particularly challenged in practice with their lack of preparedness to teach and support culturally, linguistically, and socio-economically diverse learners, students with disabilities, and students from Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander families. Hence, the time spent in professional experience must provide pre-service teachers with a broad range of teaching challenges and opportunities for reflection and consultation with mentors. This brings to the forefront the need for a different approach to professional experience other than the traditional apprenticeship model with the requirement to be able to be responsive to unique situations, school cultures, student demographics and cultures, and be able to access support and advice from a wide range of experts with a broad range of perspectives.

As one of the main purposes of professional experience placements is to provide opportunities for effective integration of theory and practice in real-world teaching settings, insufficient integration of theory, and practice is recognized as a significant issue to overcome in professional experience programs (Allen and Wright, 2014). For example, a study by Grudnoff (2011), based in a New Zealand educational context, gathered pre-service teachers' perceptions of how their professional experience placement prepared them for the transition from initial teacher education to full-time teaching. The pre-service teachers reported a mismatch between theoretical preparation and practice and demonstrated a degree of “transition shock” (Corcoran, 1981) when they enter the workplace as an early career teacher. Although there were aspects of the practicum that helped their transition to teaching, there were areas they felt where they were inadequately prepared for the intricacies of the real-life teaching environment. Adding to the problem, in the professional experience placements pre-service teachers often missed out on opportunities to experience the full complexity of being a teacher, including the scope and demands of the role at both the school and classroom levels. The outcomes of the Grudnoff (2011) study highlighted the importance of professional experience for transitioning pre-service teachers to classroom teaching and for connecting theory and practice, but also identified that there still remained a need to bridge a theory-practice gap and for further development of realistic expectations for the profession in terms of workload issues and the differing workplace cultures (Grudnoff, 2011, p. 232).

An important question relating to the theory practice nexus is: where do pre-service teachers acquire their theoretical and practical knowledge? Traditionally, the assumption was that the theoretical components are acquired at university, whilst the practical aspects are experienced in the school/early childhood environment. In initial teacher education of the 21st century such delineations are no longer true with both elements of theory and practice being embedded in pre-service teachers' university studies and the practical site experience. For example, Whatman and MacDonald (2017, p. 4) established in the key findings of a recent NZ Council for Education Research review of high quality practica that “the knowing and the being, practicing and learning of a beginning teacher cannot be separated into different sites for learning but will most profitably come together when learning is embraced in a range of contexts that cohere.” Whatman and MacDonald (2017, p. 5) further state that notions of a theory-practice divide are unhelpful and learning in initial teacher education should be reconceptualized to integrate learning and overcome barriers with the help of online learning platforms and shared portfolios for a shared understanding of purpose and pre-service teacher assessment.

Le Cornu and Ewing (2008, p. 1810) encourage a move toward a learning community model in professional experience to enable pre-service teachers to work with their peers and mentor-teachers in more collegial ways and to foster capabilities in critical reflection. They suggest that fostering a lifelong engagement in learning communities will encourage pre-service teachers to actively engage with other professionals and become responsible for their own ongoing learning and development. Mentoring in professional experience is highly valuable especially when coupled with opportunities for pre-service teachers to critically reflect on their teaching experience (Le Cornu and Ewing, 2008; Ambrosetti and Dekkers, 2010; Arshavskaya, 2016) and mentoring and support through a learning community that extends beyond professional experience for pre-service teachers through to early career teaching is highly desirable (Kelly et al., (2014).

The role of mentor can be facilitated by supervising teachers and the university supervisors, however, Ingvarson et al. (2014) stress that it essential for success that mentors are carefully selected and provided with professional development in mentoring. Ambrosetti and Dekkers (2010) define mentoring in a pre-service teacher education context as:

“Mentoring is a non-hierarchical, reciprocal relationship between mentors, and mentees who work toward specific professional and personal outcomes for the mentee. The relationship usually follows a developmental pattern within a specified timeframe and roles are defined, expectations are outlined and a purpose is (ideally) clearly delineated” (p. 52).

Nevertheless, there can be challenges in achieving the type of “non-hierarchical” reciprocal relationship described by Ambrosetti and Dekkers (2010) in professional experience settings where the mentor is in a supervisory role and responsible for assessing the pre-service teacher. In professional practice mentoring by a supervising teacher can be successful and supportive but in some cases tensions may exist. Hudson and Hudson, (2018 p. 26) identified three types of tensions present in pre-service teacher mentoring (1) personal issues, including incompatibility, and personality differences, (2) pedagogical issues including lack of pedagogical or content knowledge, behavior management, or variations in teaching styles and (3) a range of professional issues such as conflicts around social media use. A number of mentoring models and standards in teacher education are now being developed and formalized in Australia, but largely mentoring processes have not be standardized across all states (Sempowicz and Hudson, 2012; State of Victoria Department of Education Training., Hudson and Hudson, (2016). A particular difficulty for pre-service teachers, which may adversely affect their progress, is in dealing with the presence of unstated requirements or mentor-teachers' values that are in conflict with the professional ideals expected in the workplace (Buckworth, 2017).

Johnson et al. (2015) define school culture as the diverse values, beliefs, norms, assumptions, behaviors, and relationships that characterize the daily rituals of school/early childhood center life. The culture of the university and school/early childhood environments can be quite diverse, including the cultural perspectives, values, and expectations of their staff (Rowan et al., 2017). Pre-service teachers may also have a cultural perspective that contrasts with the cultures of the university and sites. This is particularly of relevance in the case of international students for whom the culture of schooling in Australia is new and may be quite different to their own schooling experience (Bahr et al., 2011).

The complexity of this merging of cultures can create a rich learning environment and a blending of perspectives promoting creativity and deep learning, but can also result in misunderstandings and conflict if such diversity in perspectives is not embraced and supported in the learning community. According to Groundwater-Smith et al. (2010) schools are complex interpersonal workplaces with an array of roles and interactions as such are rarely unproblematic particularly for the pre-service and beginning teachers. Within the school/early childhood site community complex group and personal dynamics are continually underway and to be successful the pre-service teachers need to develop an understanding of the culture of the context of their professional experience with support from the wider learning community.

A study conducted in 2017, at a Faculty of Education in an Australian University, aimed to capture teacher educators' perceptions of the importance of professional experience in initial teacher education. Teacher educators in this study were university-based, often with an academic workload inclusive of research outcomes, teaching responsibilities, and community engagement. Their role had predominantly been to support pre-service teachers while out on placement, but this had devolved to occurring mainly when challenges and issues arose, in a reactive manner.

The context of the study was a Faculty undergoing significant change related to professional experience due to a professional experience review and new Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) program standard requirements linked to course accreditation. The professional experience component of teacher education programs has been implemented in its traditional form of the “Teaching Practicum” or “Field Experience” and prior to 2016, had been referred to in this university as Field Experience. Supervising teachers in schools manage 100% of assessment in relation to the achievement of a pre-service teacher while in the classroom. University based teacher educators were typically only contacted if pre-service teachers were at risk of failure or were experiencing other challenges. A review of Field Experience in the Faculty of Education was conducted by an external expert in 2016 and recommendations were provided. In the report, Le Cornu (2016b) identified six areas of focus:

1. Addressing the nomenclature (field experience vs. Professional experience);

2. Key teaching and learning issues to be addressed;

3. Management of professional experience to include specific roles for optimal functioning;

4. The need for both academic teacher educators and faculty leadership roles to value the vision;

5. Professional learning to be provided for faculty of education teacher educators; and

6. Targeted professional learning for all staff supervising pre-service teachers.

The focus on strengthening partnerships between stakeholders has been a national focus in Australia, which was raised explicitly in 2014 through the Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (Craven et al., 2014). Craven et al. (2014) identified a number of recommendations for improving initial teacher education by re-examining the theory and practice components of initial teacher education, in particular pedagogical approaches, subject content knowledge, and professional experience. This led to an extensive review of initial teacher education, particularly focusing on the preparedness of pre-service teachers. Updated accreditation requirements for initial teacher education programs were released in 2015 in Australia by the governing body, AITSL, as a result of this review. Within the program standards, Standard Five relates specifically to professional experience (The Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, 2011). Standard Five requires professional experience programs to be conducted within formal partnership agreements between educational providers and schools, requiring these to be relevant to a classroom environment and include no fewer than 80 days in undergraduate teacher education programs and 60 days in graduate-entry programs.

Initial teacher education is a tightly regulated space in Australia, but amidst all the regulations and requirements it is important Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) do not lose sight of the core component of pre-service teacher education which is professional experience and the opportunities for real-world engagement, professional learning, and development that this allows pre-service teachers.

Given the extent and impact of these recommendations and changes, it was necessary to establish how teacher educators, in a Faculty that was reimagining initial teacher education to meet contemporary standards, saw the purpose of professional experience, and how these views were reflected in practice. The key research questions for the study were:

1. What are Faculty of Education teacher educators' views on the purposes of Professional Experience in Initial Teacher Education?

2. How do these views impact on the role and work of professional experience in the Faculty?

The study was guided by a mixed-method research methodology informed by Tashakkori and Teddlie (2010). The study involved two phases of data collection, however this paper reports on the findings of Phase One in line with its explicit focus on cultural change in professional experience. In Phase One, data were collected via an anonymous interactive survey which included a central question in Part 1, based on diamond ranking of 11 purposes of professional experience from most important to least important. The diamond ranking strategy is a commonly used tool in Australian classrooms. Participants were provided with a series of statements and are instructed to rank each statement and arrange them in a diamond formation. Teacher educators must place the statement with the highest priority at the top of the diamond formation and the least important statement at the bottom. The second, third and fourth rows of the diamond consist of statements that are ranked with descending priority, with each row having two, three and two statements, respectively. In the second part of the survey, there were four text response questions to ascertain the reasoning behind the ranking choices made in Part 1 (Part 1 and Part 2 shown in Appendix 1), as well as an open-ended question. The survey was completed by 30 teacher educators (n = 30) in the Faculty. Results of the diamond ranking of the purposes of professional experience in Part 1 are shown Figure 1.

As shown in Figure 1 the highest-ranking purposes were A. Practicum aids student teachers to put theory into practice and H. Practicum enables student teachers to meet real learners and real situations, both reflecting the Faculty emphasis on real-world teaching and authentic learning contexts. However, while the Faculty has been investing in strategic approaches to reframe the culture of the professional experience, this data showed that teacher educators ranked items most closely related to the learning community approach relatively low. The purpose D: Practicum enables student teachers to become part of a professional community ranked eight from teacher educator participants (one being the most important and ten being the least important). Purpose F: Practicum encourages student teachers to engage in reflective practice ranked four by teacher educators. These findings are important given the investment in program changes and strategic initiatives the Faculty is making toward the professional community approach for professional experience. These findings would suggest that as a result of these views, the success in transitioning to a community model and the attempted reculturing of professional experience will take time to change habits and behaviors embedded in a traditional view of the “teaching practice model.”

As described earlier there are three orientations to professional experience, a traditional teaching practice approach (often referred to as an apprenticeship model), a reflective approach and a learning community model (Le Cornu and Ewing, 2008). The institution in this study, in light of contemporary changes and standards related to professional experience in initial teacher education, recognized that it was necessary to move away from the traditional model toward the professional learning community model, which also encompasses a reflective approach. However, through the implementation, it became apparent from the participants of the study that it was not always perceived by teacher educators as being realized in practice. Survey data from Phase One indicated that participants viewed aspects of community and philosophy to be least important factors of engaging in the practicum experience and reflective practice lower than may be anticipated (Figure 1). In this case, the more traditional view of teacher education, where theory occurs at university and the practice occurs in the classroom is still held.

The importance of reflection was noted in the qualitative data by one participant, who noted:

I guess the whole idea of being reflective and reflexive is, I think, very important for professional decision-making. I would argue that there has to be a certain dimension of reflexivity related to knowledge context and knowledge, ways of knowing. But I think that can be done in a community of learners very effectively, so it becomes more of a dialogic framework for supporting that reflection and reflexivity. So, it kind of takes reflexivity out of the intra person or domain and into that group dialogic position.

Another participant then commented on this:

That would be ideal, to have this more of a dialogic approach, I think, to allow for those things to occur. But in reality, there's a power imbalance, I think, between the supervisors and the students that's typically an apprenticeship model that actually they're exposed to straightaway. It would be lovely ideally to reverse that …I think we're a long way from that.

From the qualitative data, it became apparent that the traditional apprenticeship model is current practice and at the forefront of people's minds as they discuss professional experience. This apprenticeship model is perpetuating the theory/practice divide that is prevalent in the initial teacher education literature, where it is perceived that theory happens at university and the practice happens during professional experience at sites and the two are not explicitly connected:

You don't have to go into too many schools to find a teacher who will say this [schools] is where the real stuff happens. It's not happening at universities. Then students are getting there and working with teachers like that, obviously that's a stereotype and it's not true in every case, but it still exists. I think we have to be careful about what happens in our teacher preparation courses to ensure that we're not continuing that, that we're trying to bridge that link between practice and theory and making sure that we can support them in that.

The practicum assessment model used in this institution could be seen to perpetuate the divide between theory and practice, university, and schools/early childhood sites. The qualitative data indicated the complexity of supervising teachers undertaking the assessment of the pre-service teachers, without input from the university or a moderator while on professional experience. This participant acknowledged there needs to be a shared responsibility of assessment between teacher educators and supervising teachers:

Also, we have teachers assess the students. We're teaching the students up to a point, you go to a school, and all of a sudden, we're not assessing them; we hand that over to the teachers. We haven't talked to the teacher to say this is what we expect for that sort of assessment to happen. So, there's a real gap in between what happens here and our expectations and school expectations, what they want to happen and how they would assess students

It becomes apparent when examining staff perceptions of the purpose of professional experience and how this is enacted in practice, that teacher educators need to understand the reasons behind the necessity for change toward the professional learning community model. The model that is proposed in this paper, is critical in addressing this understanding and communicating the purpose for change. The model assists in understanding the complexity of professional experience in involving all stakeholders to enhance the quality of pre-service teacher graduates.

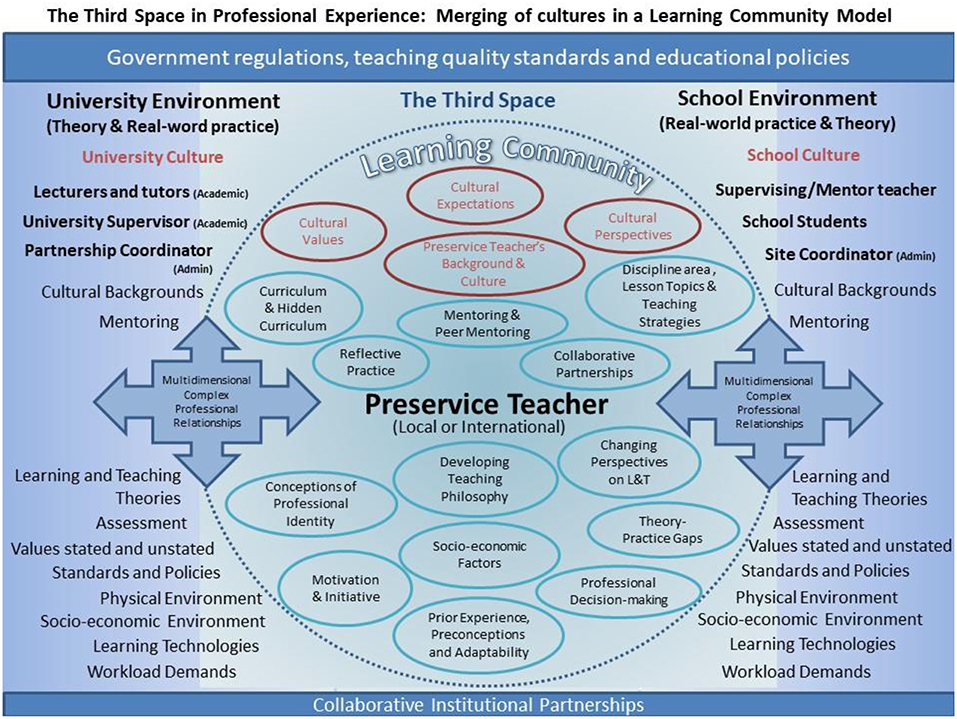

Guided by the literature, and more specifically by the work of Le Cornu and Ewing (2008) and Williams (2013, 2014), together with the findings from this study, we propose the following Learning Community model encompassing the Third Space in Professional Experience (3PEx) (Figure 2). This model illustrates the complexity of the factors involved in professional learning experience and includes cultural aspects and other elements that impact on pre-service Teachers, university supervisors, supervising/mentor-teachers, and support staff whilst negotiating multidimensional professional relationships. By making the individual aspects explicit, it is then possible to address and explore the various facets of professional experience and their interactions with one another.

Figure 2. The Third Space in Professional Experience (3PEx): merging of cultures in a learning community model.

The 3PEx model (Figure 2), developed with reference to the work of Williams (2014) and Engeström (2004), illustrates the horizontal movement between the professional practice sites of university and schools/early childhood sites with the university environment shown on the left side, the school/early childhood environment on the right side of the model and in the “in between space” in the middle is the Third Space linking the two. The Learning Community, as referred to in the literature by Le Cornu and Ewing (2008), is represented in the model by a circle which spans across all environments and the third space, and defines the virtual and physical dimension in which the pre-service teacher interacts and develops as a professional through complex multidimensional professional relationships. Drawing on the work of Whatman and MacDonald (2017) the 3PEx model shows the integration of theory and practice as present in all contexts and learning and teaching theory and practice are listed in both the university and school/early childhood site aspects of the model and ideally would be integrated throughout the pre-service teachers' learning processes in all contexts. Unlike the traditional assumptions that theoretical knowledge is acquired in university settings, the 3PEx model aims to show that theory and practice is being addressed throughout the pre-service teacher's development in all spaces, and particularly in the third space, whether in the university classroom, the school/early childhood environment or whilst interacting in the learning community. This model will assist in articulating the value of the collaborative institutional partnerships in framing the learning community, where cultures of each partner must coincide to support pre-service teachers in their practice.

The Learning Community, shown as a central feature in the 3PEx model, forms to support the negotiation of interactions in the third space in an area of overlap, where the pre-service teachers, university supervisors, mentor-teachers, and support staff all interact and the merging of university and school/early childhood environments and cultures occurs. The model shows that the context of these interactions may be guided by government regulations, teaching quality standards, and educational policies (noted at the top of the diagram) and the process is underpinned by collaborative institutional partnerships (noted below in the diagram) working toward a common goal of fostering the development of high-quality teachers.

In the 3PEx model it is expected that engagement and participation in the learning community would be promoted and supported by institutional leaders, teachers, mentors and supervisors. A critical aspect of the 3PEx model is the merging of the diverse organizational cultures of the university and schools/early childhood sites with the pre-service teachers' cultural perspectives, values, and expectations in the learning community. The relationships in this community are complex multi-faceted and multi-layered and involve pre-service teachers and school/early childhood teachers, supervising teachers, mentor-teachers, school students, administrators, and parents (Johnson et al., 2015). The 3PEx model is based on a culture of inclusion and belonging, valuing multiple perspectives, and assumes that all parties aim to create the best possible learning environment and achieve good outcomes, while acknowledging cultural differences and overcoming the challenges of different organizational cultures.

Different socio-economic settings and the cultural contrasts between private and public schools produce different learning community contexts which can change the nature of the professional experience. Pre-service teachers may find that the learning communities they encounter in different professional experience settings can offer vastly different levels of support which could be augmented by an independent online community designed to support knowledge-sharing whilst at university and beyond (Kelly et al., 2014). Early childhood pre-service teachers also encounter both prior to school and school settings where routines and expectations can be vastly different. Therefore, we propose that the learning community also has a virtual dimension that extends beyond the physical environments and that such virtual learning and support communities should ideally be utilized beyond university studies as professional support communities.

The merging of cultures is not without challenges, particularly as success can be dependent on interpersonal relationships and mutual understanding. Pre-service teachers enter the education community with many preconceptions of teaching and the teacher's role and will have to confront these ideas in practice; and in interactions one or more parties will need to change or moderate their beliefs and practices (Minor et al., 2002). Achieving cultural acceptance may involve actively challenging prior beliefs and assumptions which is suggested as best practice by Ingvarson et al. (2014), namely by providing “explicit strategies that help students to (1) confront their own deep-seated beliefs and assumptions about learning and students, and (2) learn about the experiences of people different from themselves” (Ingvarson et al., 2014, p. x).

In the 3PEx model, we acknowledge the presence of both the formal curriculum and hidden curriculum in professional experience settings. Pre-service teachers will be introduced to the formal curriculum which can vary by disciplines and usually has an associated culture, for example, the culture of science teaching. However, the hidden curriculum is the less obvious element. According to White et al. (2010) when introducing the notion of learning communities the “hidden curriculum” of professional experience must not be overlooked. The hidden curriculum is represented in the interpretations of the content of messages transmitted both in formal content and in social contexts and these interpretations can be misaligned in practice leading to potential confusion for student teachers (Dobbins, 1995; White et al., 2010). This can occur, for example, where pre-service teachers encounter widespread school practices that do not reflect the school's behavior management policies or guidelines, or where the school philosophy on inclusion and cultural diversity is not carried through into the classroom environment. Such dissonance can be present in the teaching and assessment practices of groups and individuals that the pre-service teacher is required to work with, yet rarely confronted or addressed. The presence of the hidden curriculum in both teaching and professional experience is an aspect of professional experience pre-service teachers should be aware of and learn to identify.

The mentoring and peer mentoring aspects of professional experience in the 3PEx learning community model are based on an assumption that both university and school/early childhood site staff undertake mentoring roles and pre-service teachers engage in peer mentoring with a collaborative and inclusive focus. As suggested by Le Cornu and Ewing (2008), the collegial approach to working with peers, mentor-teachers, and university supervisors in learning communities supports pre-service teachers in becoming self-directed in their learning and development and capabilities in critical reflection and reflective practice. Hence peer mentoring also features in the model as a central aspect of the learning community as it is vital to encourage pre-service teachers to foster life-long collaborative mentoring relationships with their colleagues and peers. Peer mentoring can be provided by other pre-service teachers or by learning community members, ideally in collaborative and supportive face to face or online environments with suitable resources and training (Kelly et al., 2014; Arshavskaya, 2016).

As noted in the literature, the non-hierarchical, and reciprocal nature of mentoring can be at odds with the traditional supervisory and assessment focused roles of the university supervisor and mentor-teachers, therefore in contemporary professional experience roles should be formally redefined as mentoring roles and professional development in the skills of mentoring undertaken (Ambrosetti and Dekkers, 2010). Thus, the mentor reconceptualises their identity from that of a supervisor and expert to a mentorship role.

According to Zeichner (2010), the disconnect between university and school-based components of initial teacher education can be addressed in the third hybrid space, and this should ideally by supported by strong university and school partnerships (Allen et al., 2013). In the third space the concept of “leveling” can take place where individuals can surrender their professional status and engage and interact as equals (Zeichner et al., 2015; Payne and Zeichner, 2017).

Consequently, an essential element in implementing innovation in professional experience are collaborative university and school/early childhood site partnerships, and strengthening existing and developing new university-site partnerships is an ongoing requirement (Allsopp et al., 2006; McLoughlin and Nagabhushan, 2014). According to Allsopp et al. (2006), for partnerships to be effective both the sites and universities must engage in reciprocal working and learning relationships, be open to new goals and operating structures and be willing to redefine existing roles. Where partnerships are established based on common needs and interests between universities and schools/early childhood centers the result can benefit not only the pre-service teachers, but provide professional development opportunities for university and site staff. An effective partnership arrangement, where there is a mutual understanding of operational and pedagogical goals, a focus on situated learning and genuine reciprocity in the third space can support pre-service teachers in their development from a university student to a professional (McLoughlin and Nagabhushan, 2014). The successful partnership achieves this by providing pre-service teachers with immersive authentic learning experiences in real-world settings and participation in a professional community with just in time support. Professional Development Schools modeling collaborative community-based approaches have been widely implemented with varying levels of success in the US (Darling-Hammond, 2014). Other international examples of effective partnership approaches show collaborative arrangements that offer mutual benefits including status through affiliation. For example, in Norway such partnerships involve “university schools” similar to “university hospitals” where staff have dual roles working in both the school and the university, undertaking joint research projects with shared resourcing (Lund and Eriksen, 2016; Smith, 2016). An alternative Norwegian approach documented by Smith (2016) has universities offering 3-year partnerships with mutual commitments with “partner schools.” These collaborative arrangements include providing accredited mentor training for school teachers who will mentor the pre-service teachers and 2-day seminars for school principals and coordinating mentors. Both approaches require a longer-term commitment to achieving shared goals and positive outcomes for all parties involved. Similarly, Finnish models of university-school cooperative partnerships center on research-based teacher education and the integration of theory and methodology throughout the course with teaching practicum taking place in affiliated Teacher Training Schools that are governed by the universities (McLoughlin and Nagabhushan, 2014). The Finnish approach to teacher education also emphasizes collaborative community research-based professional learning from initial teacher education with ongoing academic development throughout the teacher's career (Niemi, 2015).

Many of the factors present in the professional learning community in the 3PEx model concern the ongoing development of the pre-service teacher, such as their professional identity and teaching philosophy. The professional experience component of an initial teacher education course is where pre-service teachers have an opportunity to engage with real-world teaching environments and put into practice their professional knowledge and decision-making in an, ideally, supportive environment. Individual pre-service teachers bring into the professional experience arena their prior experience, preconceptions, motivation, initiative, and adaptability. Throughout their study and professional experience opportunities pre-service teachers develop their teaching philosophy which will continue to develop throughout their teaching careers. While in the professional experience settings pre-service teachers manage shifting conceptions of their professional identities, change perspectives on teaching and learning and continually participate in complex professional relationships (Williams, 2014) much of which occurs in the third space. According to Dobbins (1996b), fostering pre-service teacher self-efficacy is important in achieving the educational potential of professional experience and therefore professional experience should be based on a belief of affirmation of self for the pre-service teacher instead of creating self-doubts and therefore professional experience needs to be based on the notions of empowerment, collaboration, and reflection. The role of the learning community is to support the development of personal and professional qualities required by a pre-service teacher in their professional career.

Preparing pre-service teachers for a career in teaching requires the development of lifelong learning skills and the ability to adapt to changing perspectives on learning and teaching across the educational landscape and in their specific discipline areas. Learning and teaching in the 21st century is guaranteed to continue to evolve and change and the ability to continue to grow professionally and academically will be a valuable asset for all future career teachers. Starting their careers with supportive professional learning community and ongoing interaction and contribution in such a community will improve their experience of teaching and allow them to contribute to the development of the next generation of teachers.

We propose that professional experience in alignment with new regulations include:

• Awareness of the third space;

• Better theory practice integration;

• Stronger partnerships with schools and communities;

• Awareness of the merging of cultures in each professional experience setting.

Contemporary models of initial teacher education and professional experience documented in the literature center on strong institutional partnerships, extensive collaboration, and community-based approaches. The research documented in this paper highlights the difficulties in transitioning from long-established traditional models of initial teacher education and professional experience toward the contemporary community-based approaches. Such changes are influenced by policies and standards, funding models, institutional approaches and cultures, traditional teaching and learning approaches, high workloads, and outdated understandings of the division of theory and practice. In the professional experience arena of initial teacher education, a merging of cultures takes place in a third space which is usually undocumented, fluid and specific to contexts. In order to meaningfully shift the culture of professional experience it is important to identify the factors or groups of factors that are critical to fostering a learning community approach in professional experience. The purpose of the 3PEx model introduced in this paper is to map and make explicit the factors at play in the third space in professional experience in the learning community, university, and school environments.

Learning community factors identified were:

1. Cultural values, expectations, and perspectives

2. The pre-service teachers' background and cultures

3. The curriculum and hidden curriculum

4. Reflective practice

5. Mentoring and peer mentoring

6. Collaborative partnerships

7. The discipline area, lesson topics, and teaching strategies

8. Conceptions of professional identity

9. Developing a teaching philosophy

10. Changing perspectives on learning and teaching

11. Theory-practice gaps

12. Motivation and initiative

13. Prior experience, preconceptions, and adaptability

14. Professional decision-making

15. Socio-economic factors

1. University culture

2. Lecturers and tutors (academic)

3. University supervisor (academic)

4. Partnership coordinator (admin)

5. Cultural backgrounds

6. Mentoring

7. Learning and teaching theories

8. Assessment

9. Values stated and unstated

10. Standards and policies

11. Physical environment

12. Socio-economic environment

13. Learning technologies

14. Workload demands

1. School culture

2. Supervising mentor teacher

3. School students

4. Site coordinator (admin)

5. Cultural backgrounds

6. Mentoring

7. Learning and teaching theories

8. Assessment

9. Values stated and unstated

10. Standards and policies

11. Physical environment

12. Socio-economic environment

13. Learning technologies

14. Workload demands

In addition to these factors, the multidimensional, complex professional relationships that exist between the key players and stakeholders are acknowledged.

While the university in this study has invested significant resources in leadership, innovation, and policy renewal to assist with changing culture, it can be seen from the findings of the research study described in this paper that staff perceptions still include traditional mindsets that support the traditional practicum approach. Is the culture shift the greatest challenge? Is the problem in getting school/early childhood teachers, supervising lecturers, mentors, and support staff who have workload and time pressures to be present in these important conversations and a willingness to accept the joint responsibility for implementing contemporary models? Another consideration may be the shortage of Australian schools with capacity to be innovative professional experience sites. Are there enough incentives or professional rewards for schools/early childhood staff to engage in developing pre-service teachers? This research indicates that it may be difficult to achieve a culture shift while staff find it problematic to move away from the traditional practicum apprenticeship-based models. It may be difficult because in contexts with limited resources we try to implement innovations while in practice and operationally through administration traditional approaches continue to take place.

Do we learn from international models and are we able to move toward such models in our society increasing the status of initial teacher education and the institutional commitment to working partnerships between schools/early childhood sites and universities? Perhaps some of the solutions can be seen in the successes in international contexts such as the “university schools” and “partner schools” in Norway and Finland, referred to in this paper, where there is a national commitment toward supporting innovation in teacher education and suitable resourcing for large scale collaborative endeavors. International examples from Finland and Norway suggest a closer affiliation between universities and schools with shared teaching and research outcomes provides the basis for developing teaching expertise and a collaborative community approach to achieving advancements in both curriculum development and research.

We must acknowledge that the community model approach also needs to be supported by suitable online community infrastructure and participants, both staff and pre-service teachers, will require the skills to effectively use any such systems. Initially this may involve the implementation of a contemporary community-based model of professional experience at school/early childhood sites that support the learning community philosophy and by creating opportunities for teaching and academic staff who wish to engage in innovative approaches to professional experience to apply to participate. Successful working models will provide examples of best practice which can be replicated at other sites.

Another approach is to achieve change through extensive professional learning programs with ongoing mentoring and close monitoring and evaluation of thorough observation and reflective practice allowing teachers and mentor supervisors to gradually transition from the long-established practices toward the collaborative community models.

In conclusion, there is a clear need for successful models of partnerships, working collaboratively, developing communities, lifelong learning, and support to prepare high quality teaching graduates. We envisage that the 3PEx model introduced here may provide a starting point for further research, wider discussion, and analysis of the issues in implementing a learning community model of professional experience in initial teacher education.

The data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Human subjects were included and the research was approved by the QUT University Human Research Ethics Committee.

EC, RM, and TB contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Adams Becker, S., Cummins, M., Davis, A., Freeman, A., Hall Giesinger, C., and Ananthanarayanan, V. (2017). NMC Horizon Report: 2017 Higher Education Edition. Texas, TX: The New Media Consortium.

Adamson, F., and Darling-Hammond, L. (2015). “Policy Pathways for Twenty-First Century Skills,” in Assessment and Teaching of 21st Century Skills: Methods and Approach, eds P. Griffin and E. Care (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 293–310. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9395-7_15

Allen, J. M. (2009). Valuing practice over theory: how beginning teachers re-orient their practice in the transition from the university to the workplace. Teach. Teacher Educ. 25, 647–654. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2008.11.011

Allen, J. M., Ambrosetti, A., and Turner, D. (2013). How school and university supervising staff perceive the pre-service teacher education practicum: a comparative study. Aust. J. Teacher Educ. 38, 108–128. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2013v38n4.9

Allen, J. M., and Wright, S. E. (2014). Integrating theory and practice in the pre-service teacher education practicum. Teacher Teach. 20, 136–151. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2013.848568

Allsopp, D. H., DeMarie, D., Alvarez-McHatton, P., and Doone, E. (2006). Bridging the gap between theory and practice: connecting courses with field experiences. Teacher Educ. Q. 33, 19–35.

Ambrosetti, A., and Dekkers, J. (2010). The interconnectedness of the roles of mentors and mentees in pre-service teacher education mentoring relationships. Aust. J. Teacher Educ. 35, 42–55. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2010v35n6.3

Andreas, S. (2015). “Schools for 21st-century learners: strong leaders, confident teachers, innovative approaches,” in International Summit on the Teaching Profession: OECD Publishing. Avilable online at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/9789264231191-en

Arshavskaya, E. (2016). Complexity in mentoring in a pre-service teacher practicum: a case study approach. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 5, 2–19. doi: 10.1108/IJMCE-07-2015-0021

Bahr, N., Kidman, G, Adie, L., Barton, G., Campbell, M., Crosswell, L., et al. (2011). The Field Experience Report: Improving Success (Internal Report). Brisbane, QLD: Queensland University of Technology (QUT).

Bhabha, H. (1990). “The third space,” in Identity, Community, Culture, and Difference, ed J. Rutherford (London: Lawrence and Wishart),207–221.

Brady, L., Segal, G., Bamford, A., and Deer, E. C. (1998). Students' perceptions of the theory/practice nexus in teacher education. Educ. Pract. Theory 20, 5–16.

Brayko, K. (2013). Community-based placements as contexts for disciplinary learning: a study of literacy teacher education outside of school. J. Teacher Educ. 64, 47–59. doi: 10.1177/0022487112458800

Buckworth, J. (2017). Unstated and unjust: juggling relational requirements of professional experience for pre-service teachers. Asia-Pac. J. Teacher Educ. 45, 369–382. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2017.1335853

Cohen, E., Hoz, R., and Kaplan, H. (2013). The practicum in preservice teacher education: a review of empirical studies. Teacher Educ. 24, 345–380. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2012.711815

Corcoran, E. (1981). Transition shock: the beginning teacher's paradox. J. Teacher Educ. 32, 19–23. doi: 10.1177/002248718103200304

Craven, G., Beswick, K., Fleming, J., Fletcher, T., Green, M., Jensen, B., et al. (2014). Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers, Report of the Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG), Department of Education, Australia. Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG), Department of Education, Australia.

Cuenca, A., Schmeichel, M., Butler, B. M., Dinkelman, T., and Nichols, R. J. (2011). Creating a third space in student teaching: Implications for the university supervisor's status as outsider. Teach. Teacher Educ. 27, 1068–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.05.003

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Constructing 21st century teacher education. J. Teacher Educ. 57, 300–314. doi: 10.1177/0022487105285962

Darling-Hammond, L. (2014). Strengthening clinical preparation: the holy grail of teacher education. Peabody J. Educ. 89, 547–561. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2014.939009

Darling-Hammond, L., Campbell, C., Goodwin, L. A., Hammerness, K, Low, E. L., McIntyre, A., et al. (2017). Empowered Educators: How High-Performing Systems Shape Teaching Quality Around the World. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Dobbins, R. (1996a). The challenge of developing a ‘Reflective Practicum’. Asia-Pac. J. Teacher Educ. 24, 269–280.

Dobbins, R. (1996b). Student teacher self-esteem in the practicum. Aust. J. Teacher Educ. 21, 16–28. doi: 10.14221/ajte.1996v21n2.2

EDUCAUSE (2018). NMC Horizon Report Preview 2018 Higher Education Edition. EDUCAUSE& New Media Consortium.

Engeström, Y. (2004). New forms of learning in co-configuration work. J. Workplace Learn. 16, 11–21. doi: 10.1108/13665620410521477

Engeström, Y., Engeström, R., and Kärkkäinen, M. (1995). Polycontextuality and boundary crossing in expert cognition: learning and problem solving in complex work activities. Learn. Instruc. 5, 319–336. doi: 10.1016/0959-4752(95)00021-6

Fitzgerald, T., and Knipe, S. (2016). Policy reform: testing times for teacher education in Australia. J. Educ. Adm. Hist. 48, 358–369. doi: 10.1080/00220620.2016.1210588

Freeman, A., Becker, A. S., Cummins, M., Davis, A., and Hall Giesinger, C. (2017). NMC/CoSN Horizon Report: 2017 K-12 Edition. Austin, TX: The New Media Consortium.

Groundwater-Smith, S., Ewing, R., and Le Cornu, R. (2010). Teaching: Challenges and Dilemmas. Melbourne, VIC: Cengage.

Grudnoff, L. (2011). Rethinking the practicum: limitations and possibilities. Asia-Pac. J. Teacher Educ. 39, 223–234. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2011.588308

Harfitt, G. (2018). The role of the community in teacher preparation: exploring a different pathway to becoming a teacher. Front. Educ. 3:64. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00064

Hudson, P., and Hudson, S. (2018). Mentoring preservice teachers: identifying tensions and possible resolutions. Teacher Dev. 22, 16–30. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2017.1298535

Ingvarson, L., Reid, K., Buckley, S., Kleinhenz, E., Masters, G., and Rowley, G. (2014). Best Practice Teacher Education Programs and Australia's Own Programs. Canberra, ACT: Department of Education.

Johnson, B., Down, B., Le Cornu, R., Peters, J., Sullivan, A., Pearce, J., et al. (2015). Early Career Teachers: Stories of Resilience. Singapore: Springer.

Kelly, N., Reushle, S., Chakrabarty, S., and Kinnane, A. (2014). Beginning teacher support in Australia: towards an online community to augment current support. Aust. J. Teacher Educ. 39, 68–82. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2014v39n4.6

Korthagen, F., and Kessels, J. (1999). Linking theory and practice: changing the pedagogy of teacher education. Educ. Res. 28, 4–17. doi: 10.3102/0013189X028004004

Korthagen, F., Loughran, J., and Russell, T. (2006). Developing fundamental principles for teacher education programs and practices. Teach. Teacher Educ. 22, 1020–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.022

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Le Cornu, R. (2015). Key Components of Effective Professional Experience in Initial Teacher Education in Australia. A paper prepared for the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), Melbourne, Australia.

Le Cornu, R. (2016a). Professional experience: learning from the past to build the future. Asia-Pac. J. Teacher Educ. 44, 80–101. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2015.1102200

Le Cornu, R. (2016b). Review of Field Experience in the Faculty of Education at Queensland University of Technology (Internal Report). Brisbane, QLD: QUT.

Le Cornu, R., and Ewing, R. (2008). Reconceptualising professional experiences in pre-service teacher education reconstructing the past to embrace the future. Teach. Teacher Educ. 24, 1799–1812. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2008.02.008

Lund, A., and Eriksen, T. (2016). Teacher education as transformation: some lessons learned from a center for excellence in education. Acta Didact. Norge 10, 53–72. doi: 10.5617/adno.2483

Masters, G. (2016). “Policy insights,” in Five Challenges in Australian School Education, Vol. 5, Camberwell, VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER).

McDonough, S. (2014). Rewriting the script of mentoring pre-service teachers in third space: exploring tensions of loyalty, obligation and advocacy. Stud. Teacher Educ. 10, 210–221. doi: 10.1080/17425964.2014.949658

McLoughlin, C., and Nagabhushan, P. (2014). “Global examples of approaches to teacher education in the 21st century: creating theory-practice nexus through collaboration,” in Professional Development and Workplace Learning: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications, ed M. Khosrow-Pour (Hershey, PA: Information Resources Management Association), 237–257. doi: 10.4018/978-1-4666-5990-2.ch010

Minor, L. C., Anthony Onwuegbuzie, J., Ann Witcher, E., and Terry James, L. (2002). Preservice teachers' educational beliefs and their perceptions of characteristics of effective teachers. J. Educ. Res. 96, 116–127. doi: 10.1080/00220670209598798

Niemi, H. (2015). Teacher professional development in Finland: towards a more holistic approach. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 7, 279–294. doi: 10.25115/psye.v7i3.519

Payne, K., and Zeichner, K. (2017). “Multiple Voices and Participants in Teacher Education,” in The SAGE Handbook of Research on Teacher Education, eds D. J. Clandinin and J. Husu (London: SAGE Publications Ltd), 1101–1116.

Reese, M. (2012). Factors Facilitating or Constraining the Fieldwork Practicum Experience for Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Student Teachers in Queensland Schools. Professional Doctorate thesis, Faculty of Education, Queensland University of Technology.

Rowan, L., Kline, J., and Mayer, D. (2017). Early career teachers' perceptions of their preparedness to teach diverse learners: insights from an Australian research project. Aust. J. Teacher Educ. 42, 71–92. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2017v42n10.5

Sempowicz, T., and Hudson, P. B. (2012). Mentoring preservice teachers' reflective practices towards producing teaching outcomes. Int. J. Evid. Based Coach. Mentor. 10, 52–64.

Sinclair, C., Munns, G., and Woodward, H. (2005). Get real: making problematic the pathway into the teaching profession. Asia-Pac. J. Teacher Educ. 33, 209–222. doi: 10.1080/13598660500122157

Smith, K. (2016). Partnerships in teacher education: going beyond the rhetoric, with reference to the Norwegian context. Center Educ. Policy Stud. J. 6, 17–36.

State of Victoria Department of Education and Training. (2016). “A reflective guide to mentoring and being a teacher-mentor,” in (Melbourne, VIC: Early Childhood and School Education Group, Department of Education and Training). Available nline at: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/school/teachers/profdev/Reflectiveguidetomentoringschools.pdf

Stephenson, J., and Ling, L. (eds.) (2014). Challenges to Teacher Education in Difficult Economic Times. Abigdon: Routledge.

Tashakkori, A., and Teddlie, C. (eds) (2010). SAGE Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioural Research, 2nd Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Taylor, M., Klein, J. E., and Abrams, L. (2014). Tensions of reimagining our roles as teacher educators in a third space: revisiting a co/autoethnography through a faculty lens. Study. Teacher Educ. 10, 3–19. doi: 10.1080/17425964.2013.866549

The Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (2011). Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. Canberra, ACT: Education Services Australia.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity, Learning in Doing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Whatman, J., and MacDonald, J. (2017). High Quality Practica and the Integration of Theory and Practice in Initial Teacher Education: A Literature Review Prepared for the Education Council. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER). Retrieved from https://educationcouncil.org.nz/sites/default/files/Practica_Review_Summary_Report.pdf

White, S., Bloomfield, D., and Le Cornu, R. (2010). Professional experience in new times: issues and responses to a changing education landscape. Asia-Pac. J. Teacher Educ. 38, 181–193. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2010.493297

Williams, J. (2013). Boundary crossing and working in the third space: Implications for a teacher educator's identity and practice. Stud. Teacher Educ. 9, 118–129. doi: 10.1080/17425964.2013.808046

Williams, J. (2014). Teacher educator professional learning in the third space: implications for identity and practice. J. Teacher Educ. 65, 315–326. doi: 10.1177/0022487114533128

Zeichner, K. (1983). Alternative paradigms of teacher education. J. Teacher Educ. 34, 3–9. doi: 10.1177/002248718303400302

Zeichner, K. (1990). Changing directions in the practicum: looking ahead to the 1990s. J. Educ. Teach. 16, 105–132. doi: 10.1080/0260747900160201

Zeichner, K. (1992). Rethinking the practicum in the professional development school partnership. J. Teacher Educ. 43, 296–307. doi: 10.1177/0022487192043004009

Zeichner, K. (2010). Competition, economic rationalization, increased surveillance, and attacks on diversity: Neo-liberalism and the transformation of teacher education in the U.S. Teach. Teacher Educ. 26, 1544–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.06.004

Zeichner, K., Payne, A. K., and Brayko, K. (2015). Democratizing teacher education. J. Teacher Educ. 66, 122–135. doi: 10.1177/0022487114560908

Keywords: mentoring, teacher education, theory and practice, collaboration, third space, professional experience, professional community, culture

Citation: Broadley T, Martin R and Curtis E (2019) Rethinking Professional Experience Through a Learning Community Model: Toward a Culture Change. Front. Educ. 4:22. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00022

Received: 24 October 2018; Accepted: 04 March 2019;

Published: 26 March 2019.

Edited by:

Gary James Harfitt, The University of Hong Kong, Hong KongReviewed by:

Jessica Erin Charles, Bank Street College of Education, United StatesCopyright © 2019 Broadley, Martin and Curtis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tania Broadley, dGFuaWEuYnJvYWRsZXlAcXV0LmVkdS5hdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.