- Department of Pedagogical Theories and Practices, Center of Research and Social and Educational Action, Federal University of São Carlos, São Carlos, Brazil

Women and men, young, and adult, who have reached youth or adult life without elementary schooling, are part of an important and vulnerable group in Latin America, as for instance Brazil. Integrating the studies that seek to contribute to a qualitative change in Brazilian Adult Education, as a means for overcoming inequalities and in support of most vulnerable groups within the population, this article regards the case of the first Adult Education School in Brazil to transform into learning community. The research was developed between 2014 and 2016 and refers to a qualitative case study using the communicative approach, guaranteed by the use of the Communicative Methodology. Data was collected using four techniques pertaining to the Communicative Methodology: communicative in-depth interview with the school's Adult Learning and Education coordination; communicative daily-life story with students and volunteers; communicative focus groups with students, volunteers, and teachers; and communicative observation in Successful Educational Actions. The results indicate transformative and excluding elements that emerged in the following categories: the school's characteristics studied, work and life conditions and access to schooling and continuity in school, and interaction within the learning community. Comparing the results that indicate positive aspects of the Adult Learning and Education school transformed into learning communities to results in other studies about other successful Adult Learning and Education schools in Brazil, it can be established that they coincide in some aspects and go beyond in others. Although coincidence between studies was observed, they were more intensely noticed in the learning community regarding the following aspects: (a) school management oriented toward learning, with contact mechanisms with students that began missing classes, (b) appreciation, from the school staff, of teaching and learning processes, specially reading and writing, (c) a welcoming environment, bonding between professionals and students, and high expectations toward students. As for the elements identified in the learning community which were not found in the other Brazilian studies, they were: (a) enrollment increase over time and decrease in student dropout rates throughout the year, and (b) overcoming dramatic situations experienced in the neighborhood and in the school that could initially lead to school dropout.

Introduction

Women and men, young and adult, who have reached youth or adult life with no elementary education, comprise an important vulnerable group in different places worldwide (Akello et al., 2017; Boyadjieva and Ilieva-Trichkova, 2017). In the case of Brazil, inequalities affect more the black population of the country, concerning several social rights (De Haan and Thorat, 2012; Andrews, 2014), such as in the labor market (Chadarevian, 2011), infant mortality (Wood et al., 2010), health care (Chadarevian, 2011), access to schooling (De Carvalho and Waltenberg, 2015), and violent death of young people (Brasil, 2017). Concerning the group of black women, they are the ones that receive the lowest salaries for the same jobs carried out by black men, white women and white men, whose wages have been increasing (Ipea-Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada, 2015).

Although the country is a signatory to the Education for All commitments proposed in Dakar in 2000, and in the following 15 years it has made important efforts to increase the offer of Adult Education (hereafter AED), through programs, projects, funding and in-service teacher training (Brasil, 2014a), such efforts were neither continuous nor sufficient (Pierro and Haddad, 2015). As of 2016, with the financial crisis and the government's disinvestment in social policies and educational policies of AED, the living and working conditions of the young and adults with low schooling deteriorated, as well as vacancies in adequate places, times and mechanisms of education access and permanence (Gomes et al., 2017). In that year, the country registered a total of 11.8 million illiterate youths and adults, representing 7.2% of the country's population; however, only 6,28,393 enrollments in literacy and initial schooling were made (primary education) (Ibge – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2017), which demonstrates the insufficiency of the educational policies established by municipal, state and national governments.

Even though AED as formal non-literate adult education in Brazil had started in a period when it still was a Portuguese colony, reaching throughout the country once it gained independency, it was only during the twentieth century, with the growing industrialization in Brazil, that formal non-literate adult education gained greater relevance. In the context of industrial expansion, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Paulo Freire's adult literacy experience gained national and international visibility. In 1964, though, with the military coup d'etat, Paulo Freire was sent to exile, and began his journey around the globe in which he developed the theory that turned him into global reference. Meanwhile, in Brazil, his propositions suffered strict censorship. Adult education during the military dictatorship was strictly directed toward labor educational, leaving aside the humanizing contributions from Freire (Friedrich et al., 2010). With the political re-opening and democratic reuptake in the 1980s, Brazil was able to approve a new constitutional letter, the 1988 Constitution, making it possible to re-start discussing formal adult education. Di Pierro et al. (2017) state that in the 1990s legislation and public policies AED was kept aside regarding governmental funding. In the following decade, though, such funding disadvantage was corrected through the National Basic Education Fund (Fundeb).

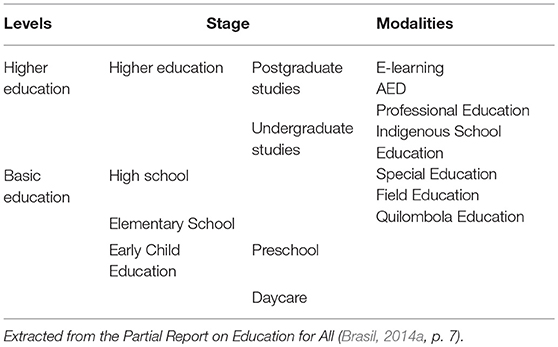

Currently, even with a more proper student funding, Brazilian AED is configured as an appendix to each school level in basic education, as drawn in Table 1, extracted from UNESCO's report (Brasil, 2014a). It can be of a labor education character, or have a compensatory education character for those who have not had proper education in childhood or adolescence. The idea of lifelong education presented in international educational documents still has not come to be in Brazil. Few are the school oriented toward adequate AED, as highlighted by Di Pierro et al. (2017). Most AED vacancies is still offered on the evening, making use, in the third shift, of buildings utilized by children or teenagers during the morning and afternoon shifts.

Another element emphasized is that through government measures taken in previous years, the Brazilian educational legislation has stipulated that the student's minimum age for enrollment in an AED class is 15 years of age, which has led and encouraged young people with low learning or inadequate behavior in regular schools to migrate to the AED modality.

This measure has altered the configuration of the clientele that predominantly composes the AED classrooms: in 2016, 52.4% of enrollments, both at the most basic levels of schooling and at the secondary level of AED, were young people 15–24 years of age (Inep - Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira, 2017).

Even with the sensible limitations faced by AED system in Brazil, finding quality condition and offer is a fundamental element for quality of life improvement of people and democracy in a country, as indicated in different by international organs and researchers from different areas. A recent Unesco - United Nations Educational Scientific Cultural Organization (2016) reaffirms the positive effects of AED on health and general well-being, on employment and the labor market, and on the social, civic and community life of people and countries. Following the worldwide trend, in Brazil, it is also observed that the more progress is made in schooling levels, the more positive outcomes are observed in employment and access to income (Salvato et al., 2010). In the health area, for example, in the case of women, lower schooling is directly related to the rate of early pregnancy, as well as to infant mortality in their homes (Brasil, 2014b). Thus, although determinants such as racism and sexism are decisive factors in the structure of wage, income and mortality inequalities in the country (Ipea-Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada, 2015), the increase in schooling reveals greater protection for citizens.

Integrating the studies that seek to contribute toward a qualitative change in Brazilian AED, as a means to overcome inequalities and to support the most vulnerable groups within the population, this article regards the case of the first AED school in Brazil to transform the learning community (hereinafter LCS). The transformation of schools into LCS has demonstrated to be an effective alternative toward high-quality education (efficacy), for all (equity), in an atmosphere of solidarity (social cohesion) (Flecha and Soler, 2013).

Having originated in Spain, the project of transforming schools into LCS was generated within the context of AED. In that country, since the 1980s, there is legislation granting specificity to AED, articulating it with the people's participation through neighborhood associations (Di Pierro, 2000; Flecha and Mello, 2012). In Brazil, despite the achievements, AED suffers from instability, as do the other educational modalities, since it receives quite disperse and peripheral attention of funding policies, infrastructure, and teacher education, and its implementation depends on the successive governments. In face of this situation, the aim of the present study was to analyze if the transformation of AED modality in Brazilian schools into LCS is an effective answer to many daily challenges faced by the teachers and students, presented as an immediate alternative for improving students' learning, interaction, and participation. The results presented in this paper are part of the research “Transformation of AED into Learning Community,” funded by the National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovations, and Communications of Brazil and developed between the years 2014–2016.

Transformation of Schools Into Learning Community Schools (LCS)

LCS is a project of cultural and social transformation of the school, aimed at achieving maximum instrumental learning for all students, with respectful social interaction regarding diversity among everyone (Elboj et al., 2002). The project was conceived and developed by the Community of Research on Excellence for All (hereinafter CREA), an international community based at the University of Barcelona (hereinafter UB) in Spain, based on a series of studies that sought evidence on educational actions that guarantee school success, with equity and solidarity (Flecha and Soler, 2013; Ríos et al., 2013). The project resulted from the analysis of the current social context, which included elements such as the information society, globalism, the dialogic turn, loss of power of traditional authorities, reflexive modernity, and risk society (Aubert et al., 2016). In such a context, communication and implementing agreements between the subjects are central elements for transforming inequalities, with human agency as the engine of transformation. Dialogued joint consensus-based action between different subjects is what creates the conditions for overcoming barriers that the subjects encounter in the path they chose to trail.

Faced with this context, new educational and organizational needs are presented to the subjects and the institutions. Knowledge and skills that guarantee that the subjects have access, treatment and use of information, such as reading and writing, languages, and mathematics are fundamental, as well as access to knowledge on managing new communication and information technologies (Aubert et al., 2016). In addition, transforming information into knowledge in a reflexive and critical manner is essential for generating self-protection, for creating alternatives for the individuals and for their groups. The current context is characterized by the construction of one's own trajectories and identities. In it, it is necessary to appreciate the interactions based on the diversity as a source of knowledge, listening to different perspectives, both convergent and divergent, dialoguing, and discussing them. As for the institutions, promoting public discussions and establishing consensus is an urgent demand, since constraints and coercions are increasingly rejected by the subjects. In short, it is a challenge for the institutions and in particular for schools to create environments in order to exchange and construct knowledge and interaction, in discussions that are free from coercion. The concept of dialogic learning and the process of transforming schools into LCS were generated by CREA/UB in view of such challenges.

Dialogic Learning

Flecha (1997) called “Dialogic Learning” a global and valid concept for a wide range of educational contexts, from childhood to the last adult stage. This concept is related to how learning is conceived. It is composed of principles that are expressed in the theoretical formulations that allow describing what, in practice, is a unit. Among several CREA productions, the principles of dialogic learning can be found in Flecha (1997) and Aubert et al. (2016). They are: egalitarian dialogue, cultural intelligence, transformation, instrumental dimension, creation of meaning, solidarity, and equality of differences. In dialogic and transformative perspective of education, Dialogic Learning includes the extensive production of Paulo Freire, articulating it with theories that strengthens action in life committed to democracy and social justice. Some of such authors included in both CREA's publications mentioned are Habermas, Chomsky, Vygotsky, Bakthin, Bruner, Rogoff.

Taking Paulo Freire's (1987) dialogic action theory as starting point, egalitarian dialogue presupposes that the speeches and propositions of each participant in the dialogue are accepted because of the arguments presented and not of the positions occupied by the subjects who articulate them (age, profession, gender, social class, educational level, group of origin). This means that power lies in the argumentation, understood as the presentation of reasons with claims of validity (Habermas, 1987). Each one presents their arguments based on what they know and what they think, and, in the dialogue, new understandings and consensuses are built for the benefit of effectiveness, equality and social cohesion. Dialogue is seen as a widely recognized learning tool in education. Aubert et al. (2016) refer to Bruner and Dewey as a way of exemplifying such recognition. They also indicate the contributions of Vygotsky, Freire, and Bakthin regarding the role of dialogue in learning.

In order to establish dialogic learning, communicative skills must be used in the family environment, in school, leisure time, and community, by means of critical and reflective participation in society. Thus, another concept arises: that of cultural intelligence. Based on the definitions of practical intelligence and academic intelligence, CREA developed the concept of cultural intelligence (Flecha, 1997). Cultural intelligence is people's ability to act in different contexts and transposing knowledge into new contexts, learning to move, to decide, to behave in a new environment. In the same group, each person can present, through dialogue, different ways of thinking and putting themselves in front of situations, constructing together greater understanding and alternatives (Aubert et al., 2016).

By sharing different points of view and ways of analyzing and solving situations, through a dialogue guided by the validity of the arguments, a process of change with two communicable directions is necessarily established: an internal transformation in each participant and external transformation, sought for the benefit of all. Both internal and external transformation demand the commitment of each person with what Freire (1987) called true word, that is, beyond reflection, true word demands from the subject that their action in the world must be consequent and coherent with what they are pronouncing. In Flecha (1997) and Aubert et al. (2016) it is clear how they articulate into such Freire's theoretical proposition Vygotski's (2008) concepts of interaction and zone of proximal development and Mead's (2010) concept of self. In that above-mentioned transformation process, Flecha (1997) and Aubert et al. (2016) highlight the access to instrumental knowledge is a necessity for life in the Information Society and the transformation of the surroundings. This is the instrumental dimension of dialogic learning.

In the instrumental dimension, the presence of the previous elements is evident: an equal dialogue is also proposed in the field of what is to be learned, since it is understood that everyone can present different knowledge in the process, given their cultural intelligence, in a dialogue that aims for and promotes personal and social transformation. Each person becomes the protagonist of their learning process, as well toward the school and its environment. Thus, the other three principles of dialogic learning can be seen in motion: creation of meaning, solidarity, and equality of differences.

In a society in which social change is a constant, there can be a climate of loss of meaning. The proposed participation in dialogic learning is an important tool in the creation of meaning by people for them to conduct their own lives. Faced with the numerous possibilities of choosing how to live, it is difficult to have a single project for all people or collectively, and it is equally difficult for the school to know which values to establish. Thus, the creation of meaning by the people and the group is fundamental in order to propose in the egalitarian dialogue, by means of dialogical learning. In this creation of meaning each person can examine the possibilities, critically reflect on them and make their choices.

Solidarity thus becomes an element of dialogic learning, from person-to-person interaction, as well as from people who are in solidarity with groups inserted in a situation of social exclusion. Flecha (1997) points to the difference between solidarity as participation in the search for transformation and construction of meaning, and solidarity tourism, in which people participate for their self-promotion.

Egalitarian dialogue, cultural intelligence, transformation, the instrumental dimension, the creation of meaning and solidarity are also associated—and integrated—in dialogic learning, by the principle of equality of differences, as shown in the following rationale. By proposing, through cultural intelligence, participation in egalitarian dialogue, thus contributing to the transformation of the school and its surroundings, benefitting the access to instrumental knowledge, creating new meanings for the life of each person and at the same time for all, in a process of constructive solidarity of alternatives, we also seek the equal right to choose a way of life and, therefore, to assume the differences. Through dialogic learning, each person builds new perceptions about life and the world and, reflecting on their culture and that of others, they can choose with greater freedom their way of living and interacting, as well as develop awareness that this process occurs with other people, thereby creating respect for different ways of life.

Creation and Validation of the Process to Transform Schools Into LCS

The process of transforming schools into LCS began in the 1990s (Morlà, 2015), based on the application of evidence-based practices at the Verneda de San Martí School of Adult Education (Sánchez-Arouca, 1999; Tellado et al., 2013), in Barcelona/Spain. Shortly thereafter, it was transferred to primary and secondary schools for children and young people. The series of research carried out for the design and diffusion of schools such as LCS culminated in the research titled INCLUD-ED—Strategies for inclusion and social cohesion in Europe from Education (Flecha, 2015), carried out by CREA, between 2006 and 2011, with the participation of different European countries (Gatt et al., 2011). From the INCLUD-ED research, the concept of Successful Educational Actions (hereafter SEA) was reached, which are those that guarantee school success and contribute to social cohesion in all the contexts in which they are implemented. Thus, the concept of SEA differs from the concept of best practices, whose success depends on the framework in which these practices are implemented (Flecha, 2015). During the INCLUD-ED research, SEAs that already comprised the design of transforming schools into LCS since its origin were validated, with the involvement of families in the life of the school and the learning activities inside and outside the classroom and others that were established (Flecha, 2015).

In LCS, the involvement of families and volunteers in the life of the school concerns their participation in education, training, and decision-making, along with the professionals and students. Participation occurs from the beginning of the transformation process of the school, during the succeeding phases and in the monitoring and evaluation of all the work after the school has already become a LC school (Ríos et al., 2013; Braga and Mello, 2014).

The first phase of transformation is called sensitization. In it, school professionals, students' families and other educational agents in the local community are presented with the theoretical bases and the SEAs that will comprise the interactions and activities in the school. With the necessary information, the professionals of the school and the other educational agents of the community are in charge of the decision-making of rather transforming, or not, the school into LCS. If the positive decision is made, the next phase begins. It is the dream phase: the students and their family members, teachers and other educational professionals, and the other educational agents from the local community envision the school they want for everyone. After that, the priority selection phase follows: a mixed commission is then set up, composed of teachers, family members, students and members of the surrounding community, to select priorities from the dreams and analysis of the available and necessary resources. The same mixed commission organizes an action-planning assembly with everyone, for the launching of the learning-aimed SEA (Elboj et al., 2002; Mello et al., 2012).

With the school transformed into a LC school and the project already underway, the families will integrate the mixed commissions, always with the presence of different agents of the community, who will take care of executing the prioritized actions and the dreams of the transformation phase, planning, executing, and evaluating the actions, together with the members of other commissions (Flecha et al., 2009).

One or more times a week, family members and other members of the local community can volunteer in interactive groups in the classroom. Interactive groups are organized in all subjects, taking into account the maximum diversity among students in each group. Each group receives a volunteer to encourage interaction among students to solve problem situations and exercises proposed by the teacher based on the subjects they are studying in class. By rotating between four and five activities, lasting 15–30 min each, students in each group are encouraged to respect each other; to explain to each other the content of the activity, asking questions to each other and supporting each other in the learning activity. For approximately one and a half hours of work, students develop concentration and learning in a dialogical way. To carry out their work, the volunteers are guided by the teacher (Mello, 2012; Valls and Kyriakides, 2013).

In the classroom, family members and others in the surrounding community can also voluntarily follow up the realization of dialogic literary gathering, which imply shared reading of universal classical literature among students, based on egalitarian dialogue; each student reads in advance, at home or at school outside class, a passage previously agreed among them, and highlights at least one paragraph that has caught their attention. When reading their highlight to the class, each student argues their choice, relating it to thoughts, knowledge, experiences; from the highlighted extract, other participants sign-up to share their thoughts, knowledge, and experiences evoked in the reading and dialogue. The dialogic literary gathering can be conducted by the classroom teacher, by community volunteers or by a student; family members and community members can also participate in the dialogue simply to support students who are still in the initial stages of learning and to share their ideas (Pulido and Zepa, 2010).

The same type of support dynamics offered by family members and other volunteers in the interactive groups, or in dialogic literary gatherings in the classroom, can also be conducted in spaces of extended study time, as for instance the tutored library. Relatives and other agents of the surrounding community, outside the classes, stimulate study, and interactions among students, focusing on investing time in reading, listening to students reading and reading with them, and favoring relationships between students and favoring the students' knowledge (Flecha et al., 2008).

In LCS, formative spaces are also created for the families, like dialogic literary gatherings between mothers, computer classes, and assisting other needs of that community. By engaging in their own development, family members deepen their relationships with schooling and the learning process of other members of their family, strengthening their ties and motivations with the school (De Botton et al., 2014).

Families and other members of the surrounding community will also take part, with a professional from the school and students, in a mixed commission responsible for starting the dialogue and preparing guidelines for the interactions, for following up its effectiveness and for evaluating the pertinence of its continuity or the need for change in cases of overcoming and preventing conflicts in school. This is the SEA called dialogic model of conflict prevention. In addition to the disciplinary model and the conflicts mediator model, the dialogic model is a community model of conflict prevention, involving students, families, teachers, and other educational agents in the dialogue process. In a small mixed commission, a dialogue is held at each class until a base proposal is reached, which is held in a meeting of students, teachers, and family members, reaching a consensual directive of living together among all (Oliver, 2014).

Finally, for a school to be transformed and maintained as LCS, producing and articulating effectiveness, equity, and social cohesion, it is important that the professionals working in it meet the criteria using the study and dialogue between them regarding the best theories and the productions based on scientific evidence. Also, that they focus on promoting high quality education for all without breaking with the development of cultivating feelings of solidarity and friendship in each person. The successful educational action validated by the INCLUD-Ed research for this purpose was the dialogic pedagogical gathering. Among colleagues from one or more schools, who wish to achieve such a work, periodic meetings may be held where they can share the reading of scientific articles, or dialogic based books. Such meetings promote an opportunity to jointly consider the transfer of knowledge to pedagogical practices. It is necessary to overcome practices based on opinions and to invest in practices with scientific basis (Flecha and Puigvert, 2005; Garcia- Carrion et al., 2017).

Educational participation of the community, interactive groups, dialogic literary gathering, tutored library, educating the family, dialogic model of overcoming, and preventing conflict and dialogic pedagogical gathering are the SEAs carried out in LCS. These SEAs were validated in the INCLUD-ED research, which showed that in different contexts (schools from 14 different countries participated) and with different vulnerable social groups, they have promoted the best results in terms of efficacy, equity and social cohesion (Flecha, 2015, 2017).

The Transformation of Schools Into LCS in Brazil

Brazil was the first foreign country, considering Spain as the cradle of transforming schools into Learning Communities, to disseminate, implement, monitor, and study the results of transferring the transformation of learning communities to a different national context from where the proposal was created. The transferring process began on the year 2001, when Mello (2002) started a post-doctoral stay in CREA/UB/Spain, in search of theories and practices they could help to better qualify Brazilian teacher education. Mello (2002) was a researcher at Federal University of São Carlos, in the state of São Paulo, and, at the same time, conducted in-service teacher education in public elementary schools in the city of São Carlos. Throughout the post-doctoral stay in CREA/UB, between 2001 and 2002, Mello studied the Spanish context and its educational legislation, as well as dialogic learning, school transformation into LCS and the communicative research methodology developed by the CREA/UB team (Flecha, 2017).

In 2001, at the beginning of the postdoctoral stay, in addition to the Verneda School of Adult Education in Sant-Martí, there were four elementary schools in Spain that were LCS. During the postdoctoral period, Mello (2002) made observations, analyzed documents and interviewed professionals, volunteers and students from the five schools. In this period, another three elementary schools joined the project in different regions of Spain, which were included in the field research that was being developed by her. At the end of 8 months of data collection, comparing the context and legislation of the two countries (Brazil and Spain), and analyzing the field research results, she concluded that there were sufficient elements that would justify the development of a pilot proposal in Brazil (Mello, 2002; Mello and Elboj, 2004).

From the observation of the success achieved by LCS in the Spanish context, its effectiveness had to be verified in the Brazilian context. Back in Brazil, in June 2002, Mello (2002) created the Nucleus of Research and Social and Educational Action (NIASE), associating it to the Federal University of São Carlos.

From the joint studies with the new members of the research group in 2003, NIASE team set out to transform schools into LCS. Over time, the team expanded, receiving new university professors, as well as undergraduate and graduate students. In addition to the university extension work, the LCS implementation channel in Brazil, NIASE team also began to research these topics in the Brazilian context, focusing mainly on the study of the effectiveness and transferability of LCS to the country (Constantino et al., 2011).

In 2003, after taking notice of the project, a municipal school of the city was the first to choose to undergo the transformation process. After the sensitization phase, managers, teachers and student's family members approved the transformation of the school into LCS. Then, everyone envisioned the school they wanted, and soon the project was set in motion. Mixed commissions were set up at the school to lead the transformation. The library was opened at lunchtime and after school as extended study time, being tutored by family and university students. A neighborhood resident, an Information Technology student and a university professor began voluntarily offering computer classes to the family members of the children, while the children were in the tutored library.

In the space and time of the tutored library, between afternoon classes and evening classes, a dialogic literary gathering began for the group of adults who studied there. They read classical literature, highlighting pieces they would like to share with their colleagues, relating these parts to their own lives. In the children's classrooms, once a week, on a set day, for an hour and a half, the teachers organized interactive groups, counting on the volunteers to conduct dialogues with the children in heterogeneous groups, focusing on accomplishing an assignment already studied. Concomitantly, the research group began to focus on studies to evaluate the effectiveness of transforming the Brazilian school into LCS. After 2 years, the school had expanded its respect and recognition to the surrounding community and families, and the quality of internal relationships had improved among all educational agents and students; it also improved everyone's instrumental learning (Braga, 2008). The results led two other schools in the municipality to transform into LCS (Mello, 2005; Mello and Larena, 2009).

With the three schools transformed and operating as LCS, in order to verify the joint data of the three schools and to compose indicators for the implementation of LCS in Brazil, NIASE proposed a large research project, financed by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) and by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). The objective was to analyze the effects of transforming the schools into LCS, both in the context of the students' school learning, as well as in the schools' socializing environment, considering their different contexts and demands (Mello, 2007).

For 2 years, the research focused on each educational activity developed in the schools (interactive groups, dialogic literary gathering, mixed commissions, education of families, and tutored library), as well as their results. With very different clienteles and demands, it was concluded that their implementation in the three different contexts was feasible and effective, producing quality learning for all students, with an improved environment of interaction among all educational agents and students (Braga and Mello, 2009; Mello, 2009; Mello et al., 2012). The transferability and the effectiveness of transforming the schools into LCSs in Brazil were verified.

In 2010, a fourth Brazilian school asked NIASE/UFSCar for LCS training. It was a school with more than a thousand students, distributed in three shifts: morning, afternoon and night. It was a regular elementary school that during the day held classes for children and adolescents and at night young and adult students in the AED modality of initial schooling. After sensitizing the team of school professionals, an unusual decision was reached: the teachers responsible for the daytime classes of children and adolescents decided that they did not want to transform the school into LCS, while the teachers and managers of the evening AED unanimously decided to change the education modality.

With the argument that the AED was already handled by managers, teachers, and students of the daytime period as a separate school, apart from the rest, AED teachers convinced the team of NIASE/UFSCar researchers to conduct the school transformation only for the night period. It would be the first experience in Brazil of transforming AED into LCS. In a structural situation very different from Spain, AED of Brazil faces, as seen in the introduction of this paper, quite adverse conditions. From 2011 to 2013 the transformation was gradually taking place. From 2014 to 2016, the research presented here was carried out on the transformation of AED into LCS in Brazil.

The Study

Objectives

As already mentioned in the introduction of the paper, the general objective presented here was to analyze if and how the transformation of AED modality in Brazilian schools into learning communities is an effective answer to many daily challenges faced by the faculty and students in those schools, presented as an immediate alternative for improving students' learning, interactions, and participation.

The specific objectives of the study were:

- Demonstrate the transformative aspects and the exclusionary aspects faced by professionals, volunteers, and students of AED in Brazil, regarding students' learning, interactions and participation when a modality is transformed into an LCS;

- Compare results referring to students' learning, interactions and participation reached by the AED school transformed into LCS to results presented by previous literature that has studied successful AED schools in Brazil.

Methods

In addition to the literature review on AED and SLC, we carried out a bibliographic research about successful practices developed in Brazilian AEDs, to use them as a comparison parameter with what we would find in field research. We searched for articles in the international Scopus database and in the Latin American Scielo database, with no beginning date indicated, but that had been published by 2016. In Scielo database, based on the descriptors “AED AND efficacy”; “Youth AND Adult Education AND efficacy”; “Youth AND Adult Education AND interactions,” “AED AND interactions,” we found 14 articles. After reading all the abstracts, only one (Silva et al., 2012) fit the inclusion parameters we had adopted: to approach an empirical study aimed at analyzing successful AED practices in Brazil, with regard to student learning and social interaction among everyone in school.

In the Scopus database, based on the descriptors “Adult Education AND Brazil” and “Adult Learning AND Education AND Brazil,” we found 59 articles. After reading the abstracts, none fit the inclusion parameters adopted. Thus, the comparison between the results from field research that we developed and other experiences of successful AED practices in Brazil was restricted to the article by Silva et al. (2012).

As for the field research, it was developed in the years 2014, 2015, and 2016 and refers to a qualitative case study (Yin, 1994), given its singularity: it is the first AED segment that has become a learning community in Brazil. In addition, this case study may offer elements that help provide alternatives to overcoming the limitations of the AED school in structurally disfavored contexts. Specifically, it was a case study using the communicative approach, guaranteed by the use of Communicative Methodology (Gómez et al., 2006).

The Communicative Methodology is based on the contributions of Social Sciences about the dialogic turn in society, which refers to dialogue as the main means of understanding and transforming reality (Habermas, 1987; Giddens, 1991; Beck, 1992; Elster, 1998). Thus, in order to better capture reality, it is necessary, in addition to the researchers' perspective, to bring all the voices of people who experience a certain reality. In the Communicative Methodology, in an intersubjective dialogue, researchers and participants analyze the data collected in an egalitarian dialogue. There is the triangulation of data to overcome analytical biases or mistakes, in addition to comparing data from different data collection techniques, also through the intersubjective dialogue between researchers and participants at the end of the analyses.

Another characteristic of the Communicative Methodology is that it is directed toward social transformation, therefore it is not limited to describing and analyzing reality, but also analyzes how reality can be transformed within the analyzed context, overcoming obstacles to social equality (Gómez et al., 2011). Thus, it is a methodology especially in line with the development of research related to vulnerable groups, allowing the transformation of the exclusionary conditions during the research process itself (Flecha and Soler, 2013). The Communicative Methodology is operationalized through communicative techniques of data collection and analysis, involving researchers, and participants throughout the research process (Gómez et al., 2011).

Local, Participants, and Ethics Statement

The school that took part in the research is located in the city of São Carlos, inner state of São Paulo. The neighborhood was stablished in the mid-1990s, in a geographically isolated region. A businessman of the city, in order to induce urbanization of the area and consequently rise in prices of such area, which was his property, stimulated the migration of families originated in different states of the country. People who set their houses and built the neighborhood had low formal educational level, or no formal education whatsoever. The history of its residents is of low employment rates or low paying jobs, informal jobs and lack of basic sanitary and social rights.

The school serves as reference to the neighborhood. Before becoming LCS, the AED already show high cohesion and commitment between their professional team. The choice for becoming a LC was made in order to overcome problems that already had been troubling the team: conflicts between young and adult students, hostility of young men toward transgender students, dropout rates along the year and low learning levels. for the research, the school was nicknamed “Walker” School, in order to keep the identity of its participants.

As previously mentioned, AED “Walker” School become a LCS in 2011, slowly implementing the SEAs. Data collection was implemented in the years 2014, 2015, and 2016.

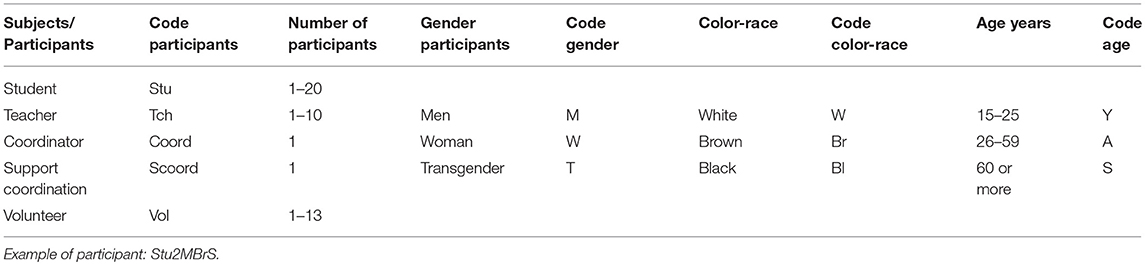

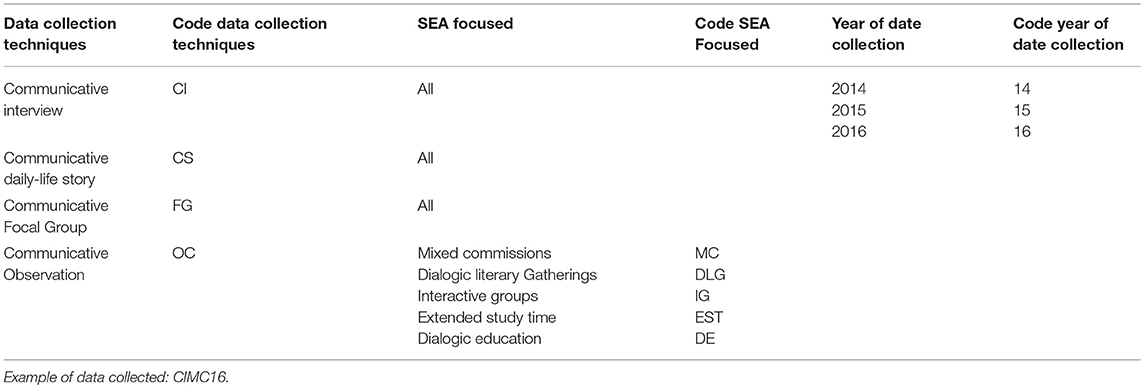

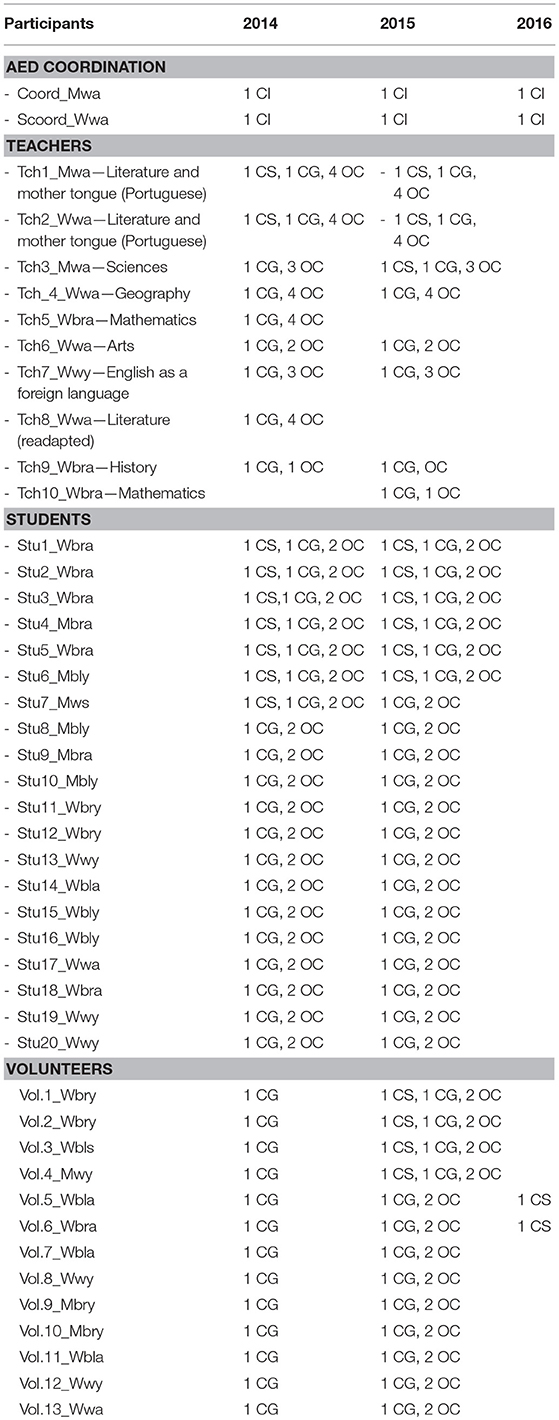

The participants in the research were the pedagogical coordinator of the AED, the supporting teacher of AED, 10 teachers of different subjects, 20 students of different classrooms, and 13 volunteers who were residents in the surroundings of the school (8) or doctoral students in a local university (5). In 2014 and 2015, an approximate total of 100 students were observed during practical activities, but in the present article the focus is on the direct testimony of the informants as well as on situations in which they were present, in order to provide a more in-depth of the observations. In Table 2 the encoding used to identify participants is displayed. In Table 3, the practical activities focused on the research is organized, and in Table 4 both participants and practical activities in which the data collection was performed are gathered.

Table 4. Direct participants in the research and data collection techniques in which they took part.

Providing more details about the participants on the research, it can be stated that among the 14–16 professionals that were employees in the school each year, including the coordinator and the coordination assistant, 8 were permanent (3 men and 5 women). The remaining professionals that participated in the research, 4 of them were newly hired in the school and had not yet gained stability in the job. Regarding the participating students, 14 were female and 6 were male, all of whom were in more advanced levels, which means they already knew how to read; 9 of them were older than 25 years and 11 were between 15 and 24 years old. Regarding the volunteers, only those who had a more constant participation in school activities took part in the research, i.e., those that continued participating from 1 year to the other, accounting for 10 women and 3 men of different ages. It is important to highlight that all of the participating teachers were white, while the vast majority of volunteers and students were brown or black and were residents in the school's neighborhood. Comparing the different composition of the different groups that participated in the research, we can affirm that it was representative of the entire school population, as well as of the proportions of blacks and whites, women and men, young and adults within the Brazilian AED scenario.

In accordance to the ethical aspects of the research, the project was approved by the National Commission of Ethics in Research (CONEP)—Brazil—and, aware of the objectives and purposes of the study, the participants signed a free and informed consent form. The written informed consent was obtained from all adult participants and from the parents/legal guardians of all non-adult participants.

Data Collection Techniques

In the referred case study, data was collected by means of four techniques pertaining to the Communicative Methodology: communicative in-depth interview with the school's AED coordination; communicative daily-life story with students and volunteers; communicative focus groups with students, volunteers, and teachers; and communicative observation in Successful Educational Actions (mixed commissions, dialogic literary gatherings, interactive groups, and learning time extension—tutored library and language and computer classes).

As previously mentioned, Table 3 displays the data collection techniques used, the SEAs in which the observations were made and the years of the data collection. In 2014 and 2015, the data collection was carried out at the end of the school year, so that the participants could have a global view of the process. In 2016, the data were complemented with the interviews of two volunteers and the general coordinator and a support coordinator of the AED at the school.

All data collection was carried out in the school before the beginning of class (interviews, communicative daily-life story and focus groups), or in the period during the classes (case of communicative observations). For each data collection situation, the researchers communicated to the group how the collection technique and the open questions to be used in the dialogue would work. The issues focused on obstacles and aspects conducive to schooling and learning and recommendations to overcome the obstacles encountered. The activities were recorded in audio and video, later transcribed, and subsequently organized by the researchers.

Data Organization and Analysis Techniques

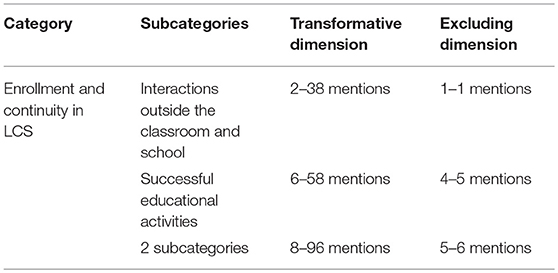

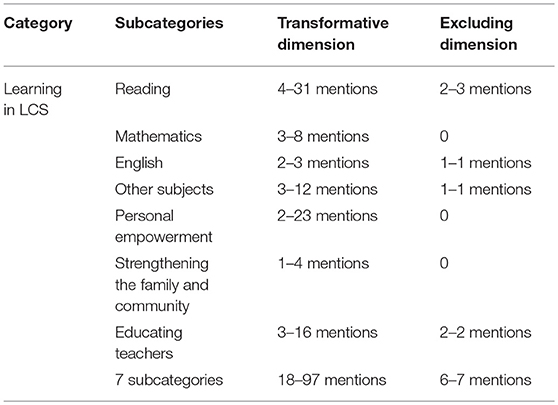

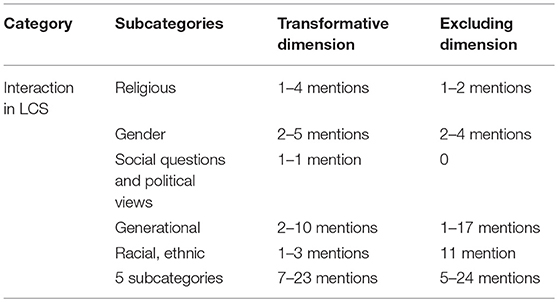

Due to its transformative structure, in the Communicative Methodology, the organization and data analysis are in two axes: the exclusionary dimension and the transformative dimension. In this research, the exclusionary dimension is composed by elements that prevent institutions and subjects from achieving the necessary instruments for exercising social equality; the transformative dimension is composed by elements that are conducive to such access. Data analysis was conducted around three categories in accordance to the research objectives. Within each category, subcategories emerged from the dataset. Data was organized into the categories and subcategories regarding their exclusionary or transformative character, recording the number of times they were mentioned by the participants. Table 5 illustrates how the elements and the frequency in which they were mentioned were allocated in the research.

Table 5. Example of date organization in categories, subcategories, elements and mentions for transforming elements and exclusionary elements.

On the analysis of the data, at the same time of their collection, the researchers have already been expressing to the participants the analyzes based on the dialogical theories and incorporating in their annotations arguments and interpretative disagreements expressed by the participants. Subsequently, with all data collected, the researchers conducted the analyzes, producing more interpretations. Finally, in a meeting scheduled for that purpose, the researchers discussed their interpretations with the group of participants that remained in the school at 2016, when the final interpretative dialogue about the dates was concluded and put into consensus; attended this final meeting: the coordinator, the coordination assistant, two Portuguese language teachers, five students and five volunteers.

Results

The results are here presented in three categories: enrollment and continuity in the LCS, learning in the LCS and interactions within the LCS. In each of the categories, we present the organization of subcategories, of elements and of the frequency that they were mentioned into the exclusionary and the transformative dimensions. We sought to illustrate through comments from the participants or observational data what students, teachers, coordinators and volunteers indicate regarding the analyzed categories. The aim is to provide broad data and analyses that demonstrate the potentiality of the transformation of AED for the transformation of young and adult students' relationships and learning.

Enrollment and Continuity in LCS

Different from the national dropout trend throughout the year of AED classes, in the “Walker” School, in 2014, the increase in enrollment in the AED modality was remarkable throughout the year. The daily-life story and discussion groups with students revealed that the presence of volunteers in the school and the recognition by the students were decisive factors in that they were learning more than in the past, whether they were studying in another school or at this school before it transformed into LCS. The transformation into LCS brought new elements to the “Walker” School, concerning interactions and learning, determining the continuity of students in school as shown in Table 6.

In the case of students, the communication between neighbors and friends in the neighborhood about what was happening at school was a factor that encouraged and stimulated more people to look for the AED of the “Walker” School and which caused enrollments to increase throughout 2014. Then, what was experienced in the school's successful educational actions was reason to remain in the school, lowering the dropout rates. The testimony of one of the students, who looked for the school because he wanted to know what dialogic literary gathering was, is an example of this type of situation:

“He [my neighbor] was talking about the dialogic literary gathering, I had no idea what it was, then my neighbor said, “next week there's going to be a dialogic literary gathering,” I kept on thinking about that, “our dialogic literary gathering” then I said: “I'm going to see what it is.” Then, that big room, [makes a gesture drawing a circle in the air, referring to the circle formed for the dialogue about the text shared in the DLG]…The group, each one reading a sentence…there are people who have a hard time reading, but we have to understand the other person's problem and show respect: “it's ok, you can do it,” the teacher said. The group would say: “Take it easy that you can do it.” There were so many different subjects I had never heard about, that I was listening and I thought it was very important! It's really cool…something I had never thought of, that I had never seen and didn't know what it was!” (Stu9_M.br.a._GC_2014)

In addition to staying in school, this man invited his wife to attend classes. She started coming with him.

About school continuity, another student commented on the interactive groups as the reason why she stayed in school:

“For me, I wanted the interactive group every day in all subjects because we learn a lot more. The volunteers help, ask, help people teach themselves. Things I could not understand before, that didn't fit into my head, now I learned. The student explains, the volunteer asks and the teacher walks over to the desks. I always thought about dropping out…illness in the family, work, problems…But I thought about the [interactive] groups and I came. I did not miss many classes and now I'm going to graduate.” (Stu3_W.br.a._GC_2014).

The mixed commissions, as successful educational activities involving the decision-making and evaluative participation of the community in the life of the school, were a privileged place to discuss the attraction of new students as a guarantee of their continuity in their studies.

The communicative encounters observed in 2014, for example, explicitly dealt with challenges to be overcome in the AED in general and in that particular community, making a dialogic recreation of successful educational actions through the dialogic contract of transforming the school (Padrós et al., 2011). One of the actions agreed upon and undertaken by the mixed commissions was proposed and developed by women, students and volunteers living in the neighborhood, raising the problem that many women in the neighborhood, mothers of small children, do not have a place to leave their children while they go to class at night. In a dialogue held between all those present (students, volunteers, teachers, coordinators), they decided to mobilize volunteers who could develop activities with the children in the school cafeteria during their mothers' night classes. Thus, they got volunteers who, during the night period, began to support the children's school tasks, a capoeira master from the neighborhood who came to give classes to the children, and also students from the neighborhood high school who promoted a movie session followed by dialogues with the children. This allowed several women, who had dropped out of school, to return to school; others who were not yet students found out through the neighbors that there were such possibilities, and they enrolled for the first time.

Another action undertaken by the mixed commissions of 2014 was the creation, in 2015, of extended study time: 1 h before the beginning of classes, from 6 to 7 p.m., computer classes and groups to train reading and to study mathematics were offered in the tutored library (TL) and the English class group. These activities were open to students, their families and other people in the neighborhood (OC_14; OC_15).

The transformation of the conditions of entrance, continuity and participation in the school in the AED modality is evident from the school transformation into a LCS and the forms of participation that it promotes, coinciding with previous researches that verify such transformation (Diez et al., 2011; Braga and Mello, 2014; Garcia and Ríos, 2014).

But in addition to these actions, both in 2014 and 2015, the interviews from the testimonials, the Communicative daily-life stories and communicative focus groups revealed that two other elements were key to enrollment, continuity or return to school: the effective learning of contents and the atmosphere of solidarity in the school, both promoted by the SEAs developed in the LCS.

Regarding the elements indicated by the research participants as excluding elements, the references made were the following: when there are still conflicts between young people and adults in school, when teachers do not prepare the activities of the interactive groups within the allocated time frame, when some student disrespects a volunteer, or when a volunteer is not well-advised on how to perform the activity (GC_Tch_2014; GC_Stu_2014).

Learning in a LCS

Learning in the LCS of the AED of the “Walker” School, based on the students, teachers and volunteers, takes place in three different areas: one related to instrumental learning, concerning skills and knowledge related to teaching subjects such as reading, mathematics, English as foreign language, science, history, geography, and the arts; another concerning the skills and attitudes that strengthen the individual in the world, helping them to strengthen their families and the surrounding community, transforming situations, and, the last one, related to teacher training. Data are displayed in Table 7.

Regarding instrumental learning, learning how to read through moments of dialogic reading, as in the Dialogic Literary Gathering, the Tutored Library, the Interactive Groups, was frequently highlighted by students, teachers, and volunteers as educational actions that generate learning of instrumental aspects as well as of reading the world, coinciding with the results found in other studies (Flecha et al., 2008; Pulido and Zepa, 2010; Serrano and Mirceva, 2010; Mello et al., 2012). Expanding vocabulary, reading fluency, content comprehension, broadening the reading of the world were elements highlighted by all (GC_Tch_2014, GC_Tch_2014, GC_Stu_2014, GC_Stu_2015; GC_Vol_2014; GC_Vol_2015; Stu.3_W.br.a._ RC15; Stu.4_M.br.a._RC15; Vol.5_W.bl.a._RC16; Vol.6_W.br.a._RC16). The references to exclusionary elements concerned the lack of classical books for all students, and the little participation of some participants during the dialogic literary gatherings, not contributing to the themes discussed.

Mathematics learning had eight references to the three transformative elements brought in through the interactive groups: losing the fear of numbers, learning to think, and learning to move from “counting numbers in the mind” to learning to count using paper. (GC_Stu_2014, GC_Stu_2015), coinciding with research carried out in the Spanish context (Díez-Palomar et al., 2010).

Related to the interactive groups, the type of learning and interaction promoted by this successful educational action coincides with previous research carried out in Spain (Valls and Kyriakides, 2013) and in Brazil (Mello, 2012). In the case of the AED in the “Walker” School, the effect on students' learning and self-esteem is illustrated by the following statement:

“I was a janitor here [at the “Walker” School], and I did not want to study because I had little time, but I ended up wanting to study because I saw that the [interactive] group helped a lot and I saw that folks really learned there. (…) when there is this group that comes to help us, it's better, because communication, dialogue with each other is very different, I was really encouraged, I learned, thank God, my grades improved.” (Stu.5._W.br.a._GC14).

English as foreign language classes were highlighted as a benefit to understanding music and posters, as well as developing interest in other languages; but a participant indicated that another group should be created for those who had already completed the initial class, otherwise their learning would not advance (GC_Stu.5_W.br.a._2014). Among the other subjects, the interactive groups were again highlighted as a way to realizing a dream of teaching and learning sciences by conducting experiments, developing geography classes using computers, and learning history through dialogue and reflection (GC_Tch4.W.w.a._2014).

In the interactive groups, the exclusionary element mentioned concerns the inappropriate behavior of a young volunteer that could impair student learning, that included lack of attention in conducting activities and harassment of young girls (GC_Tch_2015).

In terms of the learning attitude regarding the world and personal attitudes, family and community empowerment, both students and volunteers from the surrounding community have often mentioned processes benefitted by their participation in successful educational activities. A 15-year-old girl, a former daytime student at the school said:

“I think it's important to be part of the volunteer work, because it's cool, we are more interested in the lesson, you can talk to the students, there are also students who come here to talk to us, to say hello. The teachers help us, there are lessons that I can't even remember, the teachers then explain. There is a lot. My sister has already been a volunteer with me, we have already participated in almost everything, we participated in everything here in school, I really liked it, and God willing next year I'll be here again.” (Vol.1_W.br.y._GC15)

The volunteers' learning, both in content and in their attitude toward the situations revealed in this research, coincide with research results carried out in Brazil with volunteers from children's schools, that is, that there are benefits and personal learning for the volunteers (Mello et al., 2012).

With regard to teacher training, training in successful educational activities was pointed out as a differential for improving the quality of knowledge and activities in school and in the profession. The format of dialogic pedagogical gathering and workshops of interactive groups and of teacher and volunteer groups deepen teacher knowledge. The turnover of teachers and the lack of interest of a new teacher who arrives at the school, about knowing the successful educational actions, are obstacles to the success of students' learning (GC_Tch4; GC_Tch8).

LCS Interaction

Learning and interacting in a LCS were two categories that appeared in the data in a very coherent manner, although with certain particularities. Learning is possible because solidarity is established among the LCS participants, improving interaction among all. Nevertheless, there were themes regarding interaction that were emphasized. The principle of equality of differences, which presupposes egalitarian dialogue among the different so that everyone can learn and consensus regarding the actions, was a strong axis perceived, considering: different religions, the presence of homosexual, and transgender students in school, different political views, interaction between young people and adults, machismo, and racism. Table 8 shows the frequency of references to those elements that appeared in the Communicative daily-life stories, in the focal groups or in the interviews referring to these subcategories.

As for religion, at school, there often had been clashes between people of different faiths. After being transformed into a LCS, where the moderations and activities are guided by the principles of dialogic learning, the reports of students indicate that interaction has improved; in the direction of a “new multicultural laity” (De Botton and Pulido-Rodríguez, 2013), each person explains their own view and others ask what they do not understand and then expose their point of view with respect; but there are still some in school who are intransigent and who close themselves to different religious views and choices that are different from the ones they hold. This was also pointed out about gender diversity, that is, issues regarding gays, lesbians and transgender students in the school.

The following transcript of a part of a communicative observation from the Dialogic Literary Gathering, with the book “The Metamorphosis,” by Franz Kafka, illustrates what is stated here.

The teacher begins the meeting by indicating where the discussions had stopped at the previous meeting: the comparison one participant made between the family relationship with Gregor, the character who becomes an insect, and that of a friend of hers with a homosexual grandson. The participant then narrates the following:

“It was me. That's what I experienced. I went to my friend's house and in the circle we formed in the backyard of her house, her grandson appeared dressed as a woman and asked to be blessed: “Bless me grandmother.” She humiliated the boy, saying that he was no longer her grandson, that a man dressed as a woman was a sin. I thought what she did was awful. He has the right to choose. The family has to understand!” (Stu1._W.br.a._OC_DLG _2015).

As the conversation continued, another lady asks to speak and says:

“But it's in the bible, it's a sin for a man to want to be a woman. I would not accept it! It's a sin!” (Stu2._W.br.a._OC_DLG _2015).

Then a young man asks to be heard and argues:

“I talked about this with a friend the other day. I'm not gay and I'm not encouraging anyone, but if I have a son or daughter who is gay or lesbian, I will not expel them from the house, I will support them!” (Stu6._M.bl.y._OC_DLG _2015).

And addressing Stu.2, he asks, “If your son or daughter were gay, would you expel him or her from your house? I would like to understand this.” (Stu6._M.bl.y._OC_DLG _2015). After thinking about it, Stu6. replies, “No, I would not” (Stu2._W.br.a._OC_DLG _2015).

The teacher (Tch1_M.w.a_OC_DLG_2015) who was mediating the DLG asks if the students had the opportunity to search, to look for information about the doubt they had at the previous meeting about whether being gay is a choice, or sexual orientation. Faced with the negative reaction of the class, he says that he researched this and that he brought material organized by the LGBT movement of the city and asks if he can read the passage that refers to such a doubt. The group consents and listens to the reading. (OC_DLG _2015).

Thus, in an egalitarian dialogue, seeking the instrumental dimension of learning about the themes, the students are educated in the interaction between what is different. Successful educational actions, based on the principles of dialogic learning, create a space for respectful and profitable interaction, that is, one that promotes learning, reflection and transformation. In both the above topics and in the questions of generational, gender, cultural, political-partisan differences, dialogues are established. No one needs to agree with the other, but they must consider that the other can think and live different from how they live or think; the ethical limit of differences in dialogic learning is found in human rights (Valls and Munté, 2010).

In face of age-related, sexist, homophobic or racist prejudice that occurs in school, even after its transformation into LCS, the general coordinator explains that talks directly with the aggressor and limits his or her actions in this respect (GCoord._M.w.a_ CI_15). An example of intervention was observed by the research team when, in 2014, one of the students (Stu7_M.w.s_14) in the interactive groups refused to sit in the groups that included a young black female volunteer (Vol.5_W.bl.y), because for him, “a black and young woman would know nothing.” Faced with the racist act, the general coordinator had a conversation with this student indicating that it was racism and that this was inadmissible (OC_2014). During this period, an intervention of a volunteer of the neighborhood (Vol.3_W.bl.a.) was carried out with this man (Stu7_M.w.s), in a mixed commission meeting: Stu_7.M.w.s claimed that adult men should beat youngsters who fooled around in class so they would should a better behavior; Vol.3_W.bl.s. intervened to indicate that conflicts should be handled through dialogue, not violence. And the discussion moved on for the next argument (OC_2014).

In the communicative interview held in early 2016, the general coordinator of the AED at the “Walker” School, when reviewing the previous year and thinking about the planning for the new year, indicated that the dialogic model of conflict prevention and resolution (Oliver, 2014) would have to be put into operation (GCoord._M.w.a._CI.16).

As a final result of the research, at the end of the process of dialogical analysis extracted from the data, it can be stated that teachers, students and volunteers approved and recommend the transformation of the AED into LCS, confirming the advances made possible by the successful educational actions in LCS.

AED teachers from the “Walker” School, students and volunteers that participated in the research agree that LCS and SEAs apply perfectly to the context of school and Brazil and recommend that other schools should be transformed. Volunteers and students are unanimous in this statement and also point out that elementary schools and high schools also need to be transformed to improve and guarantee a high-quality learning environment for all (GC_Tch_2014, GC_Tch_2015, GC_Stu_2014, GC_Stu_2015, GC_Vol._2014, GC_Vol._2015).

In the case of teachers, they add that in the process of expansion and transformation of schools as LCS in Brazil, educators, governments and researchers must:

“- Ensure that teachers understand how the community participates in school life;

- Explain in detail that it is not an imposed or fragmented project. Teachers have to really want to transform the school;

- Explain that the participation of volunteering lies within another meaning from that advertised by the media in the country, that is, in learning communities, volunteering helps to generate a sense of community awareness and a learning possibility; it energizes, it does not teach; it does not replace the teacher or other professionals;

- Promote volunteer training and that the teacher guide their participation appropriately;

- Training workshops for AEE, for teachers, volunteers and students;

- Create a database of activities for interactive groups and interaction forum involving the teachers of learning communities;

- Direct support from the coordination in the classroom to show how to implement SEAs.” (GC_Tch_2014).

In short, as it can be seen, the transformation of the AED segment into LCS is confirmed as a proposal that generates learning, motivation and a positive environment in school, articulating different expectations of adult life. The transfer of practices based on scientific evidence, while meeting the objective of effectiveness, fairness and solidarity in the humanities, is not only desirable, but also possible.

Discussion

As it had already being found in previous research conducted by NIASE/UFSCar in Brazilian schools for children and adolescents that were transformed into LCS, the effectiveness of LCS for AED in the Brazilian context was supported. In the AED, recreating the LCS transformation and development processes was done through meeting the previous knowledge about the SEAs, identified and endorsed by the international scientific community, to the knowledge and needs expressed by the groups involved, looking into how to develop the activities within that specific context in order to improve the living conditions of the community involved. Among different agents (students, community, teachers, managers, researchers), the different voices speak for themselves and, in an egalitarian dialogue, establish the best ways to achieve the desired ends, that is, teleological action is mediated by communicative action, as discussed by Habermas (1987) in his Theory of Communicative Action. The dream phase allows an abundance of goals aimed at maximum learning by everyone and the improvement of interactional diversity; the selection phase of priorities and planning ensures to establish the agreements regarding the steps and way forward; the mixed commissions carry out the monitoring, evaluation and redirection, if necessary, of the action plan directed toward the dreams. Such a process of permanent dialogue between the voices of the community, the phases of transforming the school into LCS and the Successful Educational Actions are referred to as the dialogic contract of transformation (Padrós et al., 2011).

Both the increase in enrollments and the decrease in dropout rates recorded during the years studied in the AED of the “Walker” School were possible because the school performed SEAs and was a LCS. To that end, the participation of the community and students was fundamental in the evaluation, educational and decision-making processes, as designed in the SEAs and in the process of transformation and maintenance of a LCS.

In the mixed commissions, the students, together with volunteers and teachers, were able to evaluate the problems they faced at this time and, in consensus, generate actions to confront them. In the dialogic literary gathering groups, in the interactive groups and in the extended study time, students found support from teachers and volunteers and constituted solidarity and respectful interaction among everyone.

The transformation principle, that integrates the dialogic learning concept, must also be highlighted. As an element of external transformation, i. e., the transformation of the surrounding and the interactions, the transformation in the quality of the interactions between family and within school is present in the testimonies of the different participants. Respect to diverging thinking, solidarity toward others, improvement of service and of activities in school are good examples of it. Having volunteers offering activities to female students' children, provided these women the opportunity to resume studying. Mixed commissions were privileged situations to observe external transformation. Through egalitarian dialogue and pursuit for the validity of arguments, it was possible to observe what Freire (2001) describes as transforming challenges into possibilities.

It was also possible to observe internal transformation, i.e., the one that occurs within each person, changing what they used to think and feel, turning themselves more aware of the inequalities and differences, and behaving more coherently toward the construction of a world that overcomes inequalities and violence. The dialogues witnessed in the dialogic literary gatherings referred to deep self-reflection related to themes such as gender violence, racism and religious tolerance. However, it was in the interactions, in Dialogic Literary Gatherings as well as in other SEAs, that it was possible to observe the development of respectful posture and listening attitude, of courage to read out loud in front of others, of solidarity and care toward people.

One aspect that is of high importance to consider in this topic is that not everyone who was observed and listened to have changed their racist, violent and excluding beliefs, as was the case of Stu_7M.w.s. In his communicative daily-life story, it was possible to observe that his former life in the condition of homelessness had been of great suffering and exclusion, and seemed to drive him to wish doing to others the same cruelty of which he himself had been a victim in his youth. The time he had been in the school seemed insufficient to mobilize in him other possibilities of feelings, thoughts and action. Nonetheless, the boundaries stablished by the professionals, the students and the volunteers for his speech of racism, homophobia and against the younger students. We should not wait for everyone to have changed before we can socially stablish the limits for shared living, mainly since, as pointed out by Vygotski (1995), intrapersonal development depends on the interpersonal interactions. Therefore, changing the interactive context is the chance to change thought and feeling.

Given what has been so far exposed, we can state that the transfer of LCS to the AED modality in Brazil is possible and produces the necessary results. The presence of the voice of all educational agents in deliberately designed, studied, and proven processes highlights the dialogic contract of transformation (Padrós et al., 2011) as an instrument that associates science and dreams; global and local; universal and particular, elements that are present in the current context.

Conclusion

The study presents elements for the comprehension and analysis of how the transformation of AED modality into LCS, and the development of SEAs within them, can provide effective support for the improvement on students' learning and interaction between all, guaranteeing participation and continuity of young and adult learners in school. Efficacy and social cohesion clearly emerged in the data as factors promoted by LCS and SEAs. Regarding equity, considered to be a learning improvement by all students, considering specifically individuals from historically excluded groups, it was also successful, for guaranteeing learning for youth and adults. However, regarding blacks and women, two of the groups most affected by inequality in Brazil, it is necessary to conduct future research in order to compare the performance of all the classes to verify if equity is achieved.

We consider that the findings are, on the one hand, highly dependent on the specific context of “Walker” School, considering the atmosphere stablished between the team of professionals in AED, but on the other hand, there are signs that the dynamics provided by the SEAs was what permitted the improvement in participation, learning and interaction between all in the school. As mentioned before, the professional team ate the school was already united prior to the transformation into LCS, what certainly favored such transformation and the implementing of SEAs. As a consequence of implementing those actions, it was possible to observe an increase in enrollment, a decrease in dropouts and conflicts and a successful management of difficult situations experienced in the school. Such findings coincide with those encountered in children LCS in Brazil (Mello et al., 2012).

Comparing the results that indicate positive aspects of the AED transformed into LCS to results in other studies about other successful AED schools in Brazil (Silva et al., 2012) it is possible to affirm that they coincide in some aspects and that they go beyond others.

Though coincidence between studies was observed, they could be more intensely noticed in the learning community regarding the following aspects: (a) school management oriented toward learning, with contact mechanisms with students that began missing classes, (b) appreciation, from the school staff, of teaching and learning processes, specially reading and writing, (c) a welcoming environment, bonding between professionals and students, and high expectation toward students.

As for the elements identified in the LCS which were not found in the other Brazilian studies, there were: (a) increase in enrollment over time and decrease in student dropout rates over the school year, and (b) overcoming dramatic situations experienced in the neighborhood and in the school that, at first, could lead to school dropout.

If we compare the data to those presented by Di Pierro et al. (2017) regarding AED-exclusive schools in the state of São Paulo, we can find even more reasons to argue in favor of the transformation of AED into LCS. The AED-exclusive schools analyzed by Di Pierro et al. (2017) present several advantages related to the available structure, such as more hours for the teachers to stay in the school, activities offered all throughout the day and evening and more adult-appropriate organization of environments and materials. Nonetheless, such schools still face a restricted participation of students in decision-making processes. The authors point out that “there is practically no participation of students in the centers' management” and that, although each of the four AED centers is in a different stage of development, it is possible to affirm that “the pedagogical practices are typical of what Freire called banking model of education” (Di Pierro et al., 2017, p. 133)