95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 03 December 2018

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 3 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00103

This article is part of the Research Topic Minority Serving Institutions: Free Speech and Student Protest in the Era of Trump View all 5 articles

Higher education institutions across the country aim to contribute to students' ability to become active citizens. Civic engagement has long been an emphasis of higher education and has become a focal point from innovations such as the Carnegie Foundation's elective classification for community engagement and service-learning (Saltmarsh and Zlotkowski, 2011). Researchers have demonstrated that foundational values of democratic engagement including inclusiveness, relationships between students who engaged in cross-racial interactions, co-curricular activities and diversity experiences are related to higher levels of civic awareness and engagement (Bowman, 2011; Hurtado and DeAngelo, 2012). Furthermore, students who participated in protests were more likely to have complex thinking about democracy and awareness of global problems. Civic engagement is embedded in the history of minority student groups on college campuses, with their influence on increased access and resources, as well as their fight for more inclusive and productive campus environments (Abrego, 2008; Gasman et al., 2015; Borjian, 2018). Although civic engagement has been examined across various student groups, there is limited research on the impact of civic engagement at minority-serving institutions. This study uses a large-scale, cross-sectional approach to analyze college students' participation in civic engagement activities at 24 minority-serving institutions from 2013 to 2017 using data from the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE). Aspects of civic engagement examined include students' participation in events that address social or political issues, frequency of interactions with diverse others, participation in leadership and service-learning activities, and perceptions of their institution's contribution to their growth in areas such as becoming an informed and active citizen. Additionally, researchers explored students' ability to resolve conflicts that involve bias and prejudice and contribute to the well-being of their community; how frequently students inform themselves of state, national, or global issues; and how they may organize others around a common cause. The data led to the creation of three types of student activists. The results have implications for student affairs professionals, administrators, and faculty to redefine how students participate in civic engagement activities, to shape civic education experiences on their campus, and to help students learn how to find and use their voices.

Colleges and universities have long been sites for the cultivation and expression of civic skills and abilities. Formal civics education began as an integral part of the American curriculum, dating from the early years of the republic, followed by more active expressions of civic engagement including social organizing and protests that emerged on most colleges and universities during times of war and the civil rights movement. More recent expressions of civic engagement include the Black Lives Matter campaigns against systemic racism, and new levels of campus activism around issues of free speech and social justice leading up to and immediately following the 2016 national election. Students on college campuses throughout the country are inspiring and experiencing new forms of civic engagement.

Civic engagement goals for higher education are defined as assuring that students develop the combination of knowledge, skills, values, and motivation to make a difference in the civic life of their communities through both political and non-political processes (Ehrlich, 2000). Standards for civic engagement are reified in the elective Carnegie Classification for Community Engagement, which has identified 361 institutions for their commitment to community partnerships and for preparing educated, engaged citizens and addressing critical societal issues. Yet, calls for heightening the emphasis on civic outcomes and experiences have grown stronger since 2012 with the advent of the National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement (2012) (CLDE) release of A Crucible Moment: College Learning and Democracy's Future, which proffered a call for higher education to reclaim its civic mission and to make civic learning expected rather than optional. Although public colleges and universities have a special commitment to civic education, the history of Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs), which were established to address racial injustice and typically promote strong civic and service-oriented missions, makes them particularly important sites for studying civic engagement.

The historical mission of MSIs, combined with the increased push for civic outcomes and the current day, post-2016 national election racial climate, makes it more important than ever to examine the quality of civic engagement at MSIs. Understanding the extent to which students at MSI's are experiencing civic engagement activities, assessments of students' level of activism, and information about the relationship between civic participation and overall engagement in educationally effective practice, are important to the study of trends in civic education and to documenting the current state of the unique civic and service mission of MSIs. Understanding students' behavioral patterns as they relate to activism is critical in supporting their collegiate experience; University of Pennsylvania's Center for Minority Serving Institutions has forayed into this area by examining voter registration trends (Martinez and Hallmark, 2018). This study presents an exploratory study of MSI student participation in civic engagement activities using the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE)1, a large-scale, multi-year, quantitative dataset which includes 24 MSIs. To focus on the experiences of students at MSIs, we adopted a person-centered rather than a variable-centered approach (Malcom-Piqueux, 2015). We grouped students based on their level of engagement in a variety of civic-minded behaviors to create three distinct types of students at MSIs: Activists, Non-Activists, and Allies. We explore these student groups across varying types of minority serving institutions, examining their demographic and student characteristics, and finally looking at their engagement in other important educational experiences. More specifically, the study addresses the following research questions:

• How do students at MSIs engage in activist-based behavior?

• How does this activist behavior differ by student characteristics?

• How do these activist behaviors relate to other important forms of student engagement?

Each of the three student types had unique characteristics and behaviors based on how they engaged civically. Students exemplified different civic characteristics of mediating conflict, organizing around a collective cause, and capacity to inform themselves or others about an issue.

Higher education institutions across the country aim to contribute to students' ability to become active citizens. Civic engagement has long been an emphasis of higher education, and it has become a focal point from initiatives such as the Carnegie Foundation's elective classification for community engagement and service-learning (Saltmarsh and Zlotkowski, 2011). Researchers have identified that foundational values of democratic engagement including inclusiveness, relationships between students who engaged in cross-racial interactions, co-curricular activities and diversity experiences are related to higher levels of civic awareness and engagement (Bowman, 2011; Hurtado and DeAngelo, 2012). Furthermore, students who participated in protests were more likely to demonstrate complex thinking about democracy and awareness of global problems.

Civic engagement in higher education is an amorphous concept due to changing definitions over time and its inclusion of countless constructs (Jacoby, 2009; Woolard, 2017). Countryman (2012) specifically argues civic engagement should challenge students to contemplate the racial injustices in the United States, while Purce (2014) believes civic engagement is a broad habit that needs to develop within students through experiences interacting with the world around them. To see a variety of ideas about what it means to be civically engaged, look no further than the missions of higher education institutions, each espousing a unique way to cultivate civic engagement and citizenship. Ambiguity in defining civic education makes it difficult to create and promote experiences for students (Woolard, 2017). On the national front, both academic and student affairs organizations such as the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U), the American College Personnel Association (ACPA), and National Association of Student Personnel Administrators (NASPA) advocate for civic engagement at colleges and universities. Respectively, AAC&U's VALUE rubric for Civic Engagement was introduced to assess the level of students' civic learning and Learning Reconsidered beckoned professionals to create environments on campuses for civic participation (Rudolph, 1977; Keeling, 2004; Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2009) reminds us that the aim to develop students into contributing society members is not a new concept. Similarly, free speech movements and student activism on college campuses are not new occurrences (Council on Higher Education in American Republics, 1970; Downs, 2005; Ben-Porath, 2017; Chemerinsky and Gillman, 2017).

Colleges and universities are sometimes portrayed as metaphorical bubbles protected from the public sphere, yet they are often thrust in the spotlight of larger problems (Sampson, 1967; Canter and Englot, 2014). The free speech movement, for example, stems back to the 1960s when students took over control of a building on Berkeley's campus (Downs, 2005). Similarly, students at Alabama State University, an HBCU, found themselves at the center of federal court in Dixon v. Alabama (1961) for protests during the Civil Rights Movement; the outcome notably ending in loco parentis (Njoku et al., 2017). Although some causes or social issues may be specific to different institutions, there is a common theme across institutions of civic engagement being inspired by needs that appear to be unmet (Council on Higher Education in American Republics, 1970). There is a long-held debate over whether universities should allow student activism to propagate freely or if faculty and administrators should squelch it (Council on Higher Education in American Republics, 1970; Chemerinsky and Gillman, 2017). Free speech is seen by some as an excuse to demean and perpetuate the notion of the inferiority of marginalized groups while others believe it is a politically correct movement aimed to silence opposing views (Ben-Porath, 2017). Oftentimes the diversity movement and the free speech movement become intertwined, resulting in conflict. True diversity is sometimes seen as an acceptance of all differences yet political correctness forces the hands of administrators to develop policies counterintuitive to openness (Downs, 2005). In this way, institutions of higher education can perpetuate an oppressive culture limiting the experiences of students (e.g., institutions not allowing cheerleaders on football fields during the national anthem as they follow the controversial Colin Kaepernick protests by kneeling; Roll, 2017).

Factors that affect student unrest include the type of educational environment, individual student values, and history (Keniston, 1967). Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs) are a niche type of college or university with special missions and histories yet some of their characteristics, such as public or private control, also overlap with other institutional types (Jackson Mercer and Stedman, 2008). Federal legislation paved the way for Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs; Albritton, 2012) and Tribal Colleges or Universities (TCUs; Merisotis and O'Brien, 1998) while some MSIs earn the distinction through enrollment patterns. For example, Predominately Black Institution (PBIs) must serve at least 40% Black American students (US Department of Education, 2017), and Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs) must have at least 25% of their undergraduate population coming from Hispanic communities. MSIs are intended to have a strong connection to their purpose, often reflected in their missions. Regarding civic education, Jacoby (2009) stated institutions of higher education let their values guide their goals; “Faith-based institutions often gravitate to a social justice focus, while historically black institutions, community colleges, and urban universities may prefer a definition grounded in community partnerships or public problem solving” (p. 10).

Explorations of student engagement in educationally purposeful activities at MSIs has demonstrated positive and unique benefits (Bridges et al., 2008; Kuh, 2009). Students find staff at HBCUs and HSIs more supportive of their social needs than at Predominantly-White Institutions (PWIs) (Bridges et al., 2008). African American students at HBCUs reported their collegiate experience contributed to their civic engagement more so than their peers at PWIs (Bridges et al., 2008). However, research has shown only small differences between HSIs and PWIs for Hispanic or Latinx student experiences regarding student engagement (Bridges et al., 2008). When institutional efforts are channeled effectively toward educational practices, MSIs are beneficial for their students (Kuh, 2009). While engagement has been studied broadly at MSIs, little research has focused specifically on civic engagement.

Civic engagement is embedded in the history MSIs, and of minority student groups on college campuses. The push for equity of access and for resources as well as the fight for more inclusive and productive campus environments, has fostered activism at MSIs and among historically underserved students (Abrego, 2008; Gasman et al., 2015; Borjian, 2018). Although civic engagement has been examined across various student groups, there is limited research on the nature and impact of civic engagement at MSIs. MSIs have generally been understudied by researchers (Merisotis and O'Brien, 1998). Most research conducted on student-faculty interaction (Sax et al., 2005; Kim and Sax, 2009) and student activism has been based on PWIs (Keniston, 1967; Sampson, 1967). Because students are central to the function of colleges and universities, it is important to tell their stories. Specifically, students' role in civic engagement and activism, and for creating change makes it critical to understand the behavioral patterns of students as they relate to activism in their collegiate experience.

The data for this study come from the 2013 through 2017 annual administrations of the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE). NSSE asks about student engagement in various effective educational practices, perceptions of college environments, and how students spend their time in and out of the classroom. Participating institutions had the option to add brief item sets, called Topical Modules, to the end of their NSSE administration. This study focuses on the more than 12,000 first-year and senior student respondents from the 24 MSIs that elected to administer NSSE's Civic Engagement Topical Module between 2013 and 2017 The items in this set examined student participation in events that address social or political issues as well as students' experiences resolving conflicts that involve bias and prejudice and contributing to the well-being of their community.

A series of items from the Civic Engagement Topical Module, several demographic items, and select items from the NSSE core survey were the focus of this study. Items from the Civic Engagement module2 were combined to create three scales: (1) the Conflict Resolution scale that asked students about their ability to help resolve conflicts and bring together individuals of different backgrounds, (2) the Information/Knowledge scale that asked students about whether they had discussions and sought out knowledge about local, national or global issues, and (3) the Organizing scale that asked students about their experience with raising awareness of issues and organizing situations where various issues are addressed. Component items and scale details can be found in Table 1. Demographic variables of interest were racial/ethnic identification, gender identity, sexual orientation, disability status, class level, major field, and first-generation status. NSSE core survey variables of interest consisted of the scale measures Reflective & Integrative Learning, Collaborative Learning, Discussions with Diverse Others, Student-Faculty Interaction, Quality of Interactions, and Supportive Environment; and single items including, student involvement in service-learning and leadership opportunities; and student-perceptions of how their institution has contributed to their development of personal values and ethics, working with others, understanding people of diverse backgrounds, and being an informed and active citizen.

Students at 24 MSIs that participated in at least one NSSE administration between 2013 and 2017 were included in this study. The largest group of NSSE-participating MSIs were Hispanic Serving Institutions (17), followed by Historically Black Colleges/Universities (4). Additionally, the data included respondents from Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian-Serving (ANNH) institutions (2), Asian American Native American Pacific Islander-Serving Institutions (ANNAPISI) (2), a Predominantly Black Institution (PBI) (1), and a Native American-Serving Non-Tribal Institution (1). Three of the participating MSIs had more than one MSI designation. The majority of MSIs in the data are Master's Colleges and Universities and half are public institutions. This sample of MSIs is not representative of MSIs in the U.S., but provides relevant, available data to explore our question. Furthermore, due to the uneven numbers in each MSI category, only an analysis across all 24 MSIs was explored.

The student respondents in this study consisted of 4,818 first-year and 7,195 senior students who responded to the NSSE core items and the Civic Engagement Topical Module set. Around 69% of respondents identified as women, and 59% were first-generation students, with the average age of respondents being 26 (SD = 9.47).The largest racial/ethnic groups were White students (34%), Hispanic or Latino students (26%) and Black or African American (13%). The largest proportions of students majored in Business (19%), followed by 16% majoring in Health Professions, and 12% majoring in Social Sciences. One in ten (10%) respondents identified with having a diagnosed disability or impairment.

Due to the exploratory and introductory nature of our investigation into the civic engagement of students at MSIs, much of our analysis is descriptive. Also, akin to Malcom-Piqueux's (2015) person-centered approach to analysis, which approaches the study of individuals who share similar attributes or experiences by identifying qualitative differences among individuals in these shared categories, we first grouped students based on their participation in civic behaviors and then looked to see who comprised these groups. To answer our first research question about how students at MSIs engage in activist-based behavior, we first conducted a two-step cluster analysis. After an examination of percentile distributions and preliminary clusters of activist-based behavior, a three-cluster solution was selected. We then looked at how the proportions of these three groups of students varied at the 24 institutions included in our study. To answer our second and third research questions exploring how the characteristics of students varied in these three groups and how these groups engage in other ways, we examined descriptive results.

We found three distinct patterns of activist-based engagement amongst students at MSIs. Respondents who were high on all Civic Engagement scales were in cluster 1. We labeled this cluster Activists, as they are students who were highly engaged in civic activities. The second cluster, Non-Activists, was comprised of respondents who reported the lowest involvement in conflict resolution and being knowledgeable about civic engagement activities and with relatively low involvement in organizing civic engagement activities. We labeled the third cluster Allies, as it included respondents who were fairly educated about civic engagement information, high on conflict resolution but had the lowest involvement in organizing civic engagement activities. Overall, Allies made up the largest portion of students at MSIs (45.5%), followed by Non-Activists (30.8%) and then Activists (23.7%). See Table 2 for Civic Engagement scores for each of these groups.

We found, however, that there was a notable amount of variation in the proportions of these separate groups at individual campuses. The proportion of Activist students ranged from 17 to 40% of respondents at our 24 MSI institutions. Only two institutions (Institution 1 and 2) had more than a third of their students behaving as Activists. Proportions of students who engaged in Non-Activist behaviors ranged between one in five (20%) to half (48%) of students on the campuses studied. Similarly varied, students engaged as Allies ranged from 25 to 57% of students on MSI campuses. Four institutions (Institutions 10, 18, 20, and 21) had more than half of respondents who behaved as Allies. The three institutions (Institutions 22, 23, and 24) that had <20% Activists had at least 30% Non-Activist and Ally students. The two institutions (Institution 12 and 23) that had students exhibiting Non-Activist behavior above 40% had less than a quarter of respondents who behaved as Activists and low percentages of respondents who behaved as Allies. More information about the proportions of students in these civic-engagement related groups by individual institution can be found in Table 3.

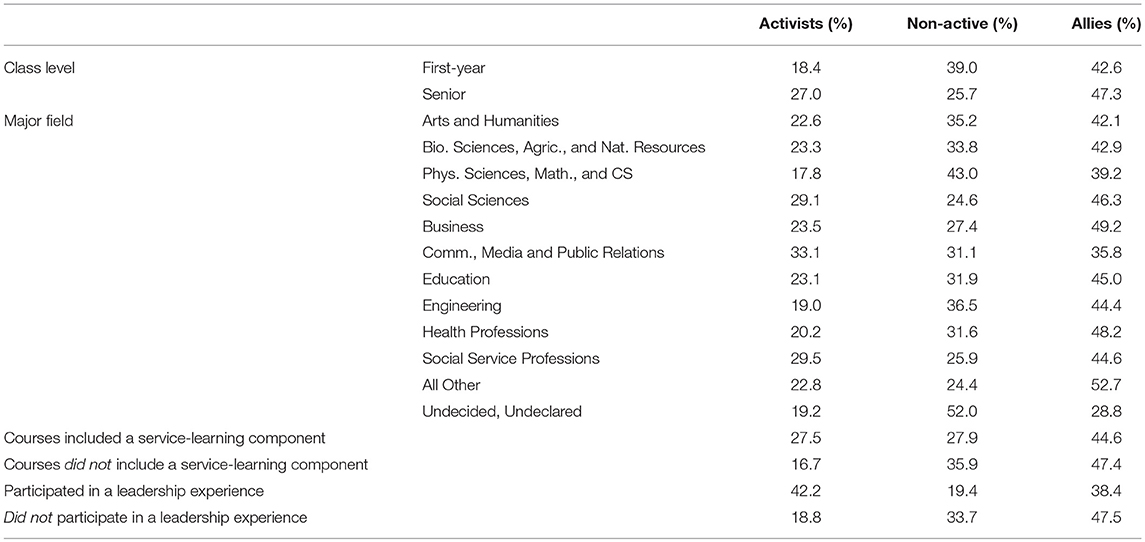

The demographic and student makeup of our three civic engagement groups differed in many notable ways. Around one-third of students who identified as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (38%), Black or African American (31%) or Other (31%) were Activists while large proportions of students identifying as White (49%), Multiracial (48%), or Hispanic or Latino (45%) were Allies. First-generation students were more likely to be Allies (45%) or Non-Activists (31%). Although students who identified as men or women were more likely to be Allies (42 and 47%, respectively), students who identified with another gender identity or preferred not to respond to the gender identity question were overrepresented as Non-Activists (38 and 42%, respectively). Straight students were most represented as Allies (42%), but LGBQ+ students were more evenly divided as Activists (24%), Non-Activists (37%), and Allies (35%). Students with a diagnosed disability or impairment were slightly more likely to be Activists (27%) than students without a diagnosed disability or impairment (23%). About half (47%) of seniors engaged in Ally behavior while less than one in five (18%) of first-years engaged in Activist behavior. Approximately one-third (33%) of students majoring in Communications, Media, and Public Relations were Activists, while two in five students (43%) majoring in Physical Sciences, Mathematics and Computer Science and over half (52%) of students with Undeclared/Undecided majors acted as Non-Activists. Large proportions of students majoring in Business (49%) and Health Professions (48%) were Allies. More details about the demographic and student characteristics of our three civic-engagement groups can be found in Tables 4, 5, respectively.

Table 5. Select student characteristics and experiential activities by civic engagement student groups.

Students who participated in leadership experiences were mostly notably represented as Activists (42%) and Allies (38%). Students who participated in a course that included a service-learning component were more likely to be represented as Activists (28%) than students whose courses did not include a service-learning component (17%). See Table 5 for more details about the proportions of our three civic engagement groups and those that participated in these two experiential learning opportunities.

Activists had higher mean scores on Reflective and Integrative Learning, Collaborative Learning, Discussions with Diverse Others, Student-Faculty Interaction, Quality of Interactions, and Supportive Environment. Non-Activists had the lowest means for these measures of engagement. Allies' scores were between these two groups. Similarly, Activists reported that their institution contributed more strongly to their skills and development in creating a personal code of values and ethics, working effectively with others, understanding people of other backgrounds, and being an informed and active citizen, followed by Allies, and leaving Non-Activists perceiving the lowest gains in these areas. See Table 6 for more details.

Institutions self-select participation in NSSE administrations and additionally opt to add Topical Modules such as the set of items studied here. As a result, there is some lack of generalizability in these findings given institutions' reasons for selecting the additional item set varies. Results from this study should not be generalized beyond this sample of MSIs and interpretations of these results outside of this context should be done with caution. As we saw in this study, there was a wide variety in the representation of civic-engagement groups across institutions, and there is likely a wide variety of variation in behavior within these groups. The variation among MSIs suggests there is value to exploring the campus context, but NSSE's data privacy agreements prevent us from identifying institutions to do this more in-depth study. Additionally, the collapsing of students into various identity groups, and similarly the aggregation of a greatly varied group of institutions, may further hide distinctions in student behaviors. Results may not necessarily apply to all subpopulations of students or all MSIs and this variation should be further examined in future research.

Civic engagement is a longstanding focus of higher education in the United States. Yet, more recent emphasis has focused on strengthening this civic mission, the assessment of civic engagement, and the educational benefits of these experiences. The civic engagement experience of students at MSIs are of particular interest given MSI's history of activism. Our study offers a glimpse of the civic engagement experience of students at MSIs, how these behaviors vary by student characteristics, and lends insight into the relationship between activist behaviors and other forms of student engagement.

Results of this exploratory study show a distinct pattern of civic behaviors among students at MSIs, suggesting three groups: Activists, Allies, and Non-Activists. We imagine Activists to be students who view themselves as champions of a cause, on the frontlines organizing events and informing others about issues. Allies excel at helping others resolve conflict, standing by the sides of their Activist peers, but they do very little of the organizing themselves. In contrast, Non-Activists are less likely to engage in social issues, yet are informed of social issues, but lack a notable amount of skill in conflict resolution. These three groups suggest distinct stories about the student experience with civic activities. The variation between MSIs is also worthy of notice. Several questions arise from this variation. Considering other findings on the effects of climate on different student populations at different types of institutions (i.e., Hurtado and Ponjuan, 2005; Garvey et al., 2015; Harris and BrckaLorenz, 2017), one might reasonably conclude that this variation is due to the campus environment. Several factors on a campus might lead to larger proportions of activists such as a high frequency of civic activities, including controversial speakers, injustice awareness events and protests for a cause, or faculty and staff support of civic engagement activities including community organizing or service-learning, and particularly, visible forms of campus and community action. Interaction with faculty can lead to positive outcomes for students in political engagement and cultural cognizance (Sax et al., 2005) and faculty also support students by strategizing with them and helping them navigate politics or create campus change (Kezar, 2010). Relating this literature to our study suggests that institutions with larger proportions of Activists may have more faculty and staff activists and administrators that support student ambitions or that greater numbers of faculty and staff find it important to mobilize students to action. Our finding about the variation between MSIs suggests there is value in conducting more in-depth examinations of the campus context and in particular, the relationship between faculty and staff support and civic engagement and activism.

One might further wonder about the “right mix” of these civic engagement groups. Institutions may want to consider what the right mix of civically engaged students would look like for their institution and then focus on providing students with the foundation for achieving those goals. It would be difficult to imagine institutions focused on creating civically responsible citizens hoping to maximize their proportions of Non-Activist behaving students. These students lagged behind their Activist and Ally peers most remarkably in conflict resolution. Institutions may want to first focus on ways to improve students' skills in resolving disagreements, pushing back on discrimination, leading inclusive groups, and contributing to the general well-being of others. The intentional design of learning experiences to, for example, foster students conflict resolution skills or capacity to address discrimination may well be outcomes that faculty and student affairs professionals could collaborate on to develop students' civic engagement competencies and to increase the proportion of Activists and Ally behaviors. Starting with a shift of students from Non-Activists to Allies could be one way to create communities where taking action for social and political issues is less necessary, or when necessary, is more supported. Given that the newest generation of students coming to our campuses are expecting activism to be part of their university experience (Kezar, 2010), institutions could be more intentional about creating educational experiences in and outside the classroom that are associated with the different types of civic engagement they hope to foster.

Seeing the variation of students within these groups additionally raises questions about the environment within major fields. Seeing larger proportions of Activists in fields such as Communications, Social Service Professions, and Social Sciences leads to more causal questions. We wonder if students who are more active in social and political causes are more likely to choose one of those major fields or if these major fields are inspiring more active behaviors. Larger proportions of Non-Activist students majoring in Physical Sciences and Engineering should spur these disciplinary fields to think about how conflict, discrimination, and non-inclusive spaces may negatively affect the students in their programs as well their capacity to address these issues in their future careers. It may be beneficial for these fields to consider how they might offer experiences associated with Activist or Ally groups, such as providing civic engagement activities and incorporating conflict resolution skills into courses, labs, or student clubs. Faculty members in fields characterized by fewer Activists or Ally behaviors might begin by exposing students to readings or speakers that reflect civic engagement in the major field, and or to design assignments that invite students to discuss or take a stance on a field-specific injustice.

Because the mission of MSI's focus on the well-being and development of racial/ethnic minority students, it was interesting to see that some students of color were largely represented as Non-Activists. Close to half of American Indian or Alaska Native and Asian students exhibited Non-Activist behaviors. Students of color have long been on the frontlines of activism in higher education, so this finding is worthy of further study. This finding could be a limitation of our data which did not allow us to explore MSIs beyond the broad category. Future research may want to investigate whether this is a finding based on cultural differences of these students or if the MSI environment is somehow creating this difference. Multiracial students were also notably low in their representation as Activists, but they behave more strongly as Allies than the American Indian, Alaska Native, or Asian students.

Students in our Activist and Allies groups were generally more engaged in a variety of forms of effective educational practice. These students are doing more to connect their learning to societal issues, reflect on their own views and the perspectives of others, and take courses that include community-based projects. They also interact more with people who are different from them, work more collaboratively with their peers, and have more frequent and meaningful interactions with faculty outside of class. These students feel that they have a better quality of interactions with a wide variety of people at their institution and generally feel more supported both academically and personally. Given that they more strongly attribute their growth in knowledge, skills, and development in a variety of ways to their institution, speaks highly to the idea that institutional environments have an impact on students' civic development. Additionally, this can influence the support MSI faculty and staff provide students in their activism efforts. If MSI faculty and staff are working to engage students at their institution, this can lead to students feeling supported enough to move through the activist categories. It is also important for MSI faculty and staff to be aware of the activist history at their institution to provide students eager to participate in activism a foundation from which to begin.

Student participation in leadership experiences has one of the most striking relationships with our civic engagement groups of all the other forms of engagement studied here. A very low proportion of students that had a leadership experience displayed Non-Activist behaviors while four in five students in a leadership experience behaved as Activists and Allies. Certainly, students inclined toward activity or interest in social and political causes would tend to take part in leadership experiences, but it is just as likely that these experiences encourage students to learn more about issues that affect others and give them the power to act. Institutions should find more ways to involve a variety of students in leadership experiences and help them to translate these skills into their future lives as active citizens.

The results of this study have implications for student affairs professionals, administrators, and faculty who are interested in assuring higher education's civic mission. Knowing more about the civic experiences and behaviors associated with three student types at MSIs could influence educators to refine educational offerings to support civic outcomes and to help students learn how to find and use their voices. Leveraging qualitative research to obtain personal narratives of the students could be a future direction for researchers. Given the history of activism and protest at MSIs, it is important to document the current state of students' civic engagement and to explore ways to more intentionally shape the learning environment to assure students graduate with the civic experience and skills required of active and informed citizens.

Electronic informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study and protocol were approved by Indiana University's Institutional Review Board.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. ^Survey Instrument. Available online at: http://nsse.indiana.edu/html/survey_instruments.cfm

2. ^Topical Module. Available online at: http://nsse.indiana.edu/pdf/modules/2017/NSSE_2017_Civic_Engagement_Module.pdf

Abrego, L. (2008). Legitimacy, social identity, and the mobilization of law: the effects of Assembly Bill 540 on undocumented students in California. Law Soc. Inq. 33, 709–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4469.2008.00119.x

Albritton, T. J. (2012). Educating our own: the historical legacy of HBCUs and their relevance for educating a new generation of leaders. Urban Rev. 44, 311–331. doi: 10.1007/s11256-012-0202-9

Association of American Colleges Universities (2009). Inquiry and Analysis Value Rubric. Available online at https://www.aacu.org/value/rubrics/inquiry-analysis

Ben-Porath, S. R. (2017). Free Speech on Campus. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Borjian, A. (2018). Academically successful Latino undocumented students in college: resilience and civic engagement. Hispanic J. Behav. Sci. 40, 22–36. doi: 10.1177/0739986317754299

Bowman, N. A. (2011). Promoting participation in a diverse democracy: a meta-analysis of college diversity experiences and civic engagement. Rev. Educ. Res. 81, 29–68. doi: 10.3102/0034654310383047

Bridges, B. K., Kinzie, J., Nelson Laird, T. F., and Kuh, G. D. (2008). “Student engagement and student success at historically Black and Hispanic-serving institutions,” in Understanding Minority-Serving Institutions, eds M. Gasman, B. Baez, and C. Sotello Viernes Turner (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press), 217–236.

Canter, N., and Englot, N. (2014). “Civic renewal of higher education through renewed commitment to the public good,” in Civic Engagement, Civic Development, and Higher Education, ed J. N. Reich (Washington, DC: Bringing Theory to Practice), 3–11.

Chemerinsky, E., and Gillman, H. (2017). Free Speech on Campus. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Council on Higher Education in American Republics (1970). Student Activism and Higher Education: An Inter-American Dialogue. New York, NY.

Countryman, M. J. (2012). “Diversity and democratic engagement: civic education and the challenge of inclusivity,” in Civic Provocations, ed D. W. Harward (Washington, DC: Bringing Theory to Practice), 47–50.

Downs, D. A. (2005). Restoring Free Speech and Liberty on Campus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Garvey, J. C., Taylor, J. L., and Rankin, S. (2015). An examination of campus climate for LGBTQ community college students. Commun. Coll. J. Res. Pract. 39, 527–541. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2013.861374

Gasman, M., Spencer, D., and Orphan, C. (2015). Building bridges, not fences: a history of civic engagement at private black colleges and universities, 1944–1965. Hist. Educ. Q. 55, 346–379. doi: 10.1111/hoeq.12125

Harris, J. C., and BrckaLorenz, A. (2017). Black, White, and Biracial students' engagement at differing institutional types. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 58, 783–789. doi: 10.1353/csd.2017.0061

Hurtado, S., and DeAngelo, L. (2012). Linking Diversity and Civic-Minded Practices With Student Outcomes: New Evidence from National Surveys. Available online at: https://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/linking-diversity-and-civic-minded-practices-student-outcomes-new

Hurtado, S., and Ponjuan, L. (2005). Latino educational outcomes and the campus climate. J. Hispanic High. Educ. 4, 235–251. doi: 10.1177/1538192705276548

Jackson Mercer, C., and Stedman, J. B. (2008). “Minority-serving institutions: Selected institutional and student characteristics,” in Understanding Minority-Serving Institutions, eds M. Gasman, B. Baez, and C. Sotello Viernes Turner (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press), 28–42.

Keeling, R. (ed). (2004). Learning Reconsidered: A Campus-Wide Focus on the Student Experience. ACPA - College Student Educators International and NASPA - Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education.

Kezar, A. (2010). Faculty and staff partnering with student activists: unexplored terrains of interaction and development. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 51, 451–480. doi: 10.1353/csd.2010.0001

Kim, Y. K., and Sax, L. J. (2009). Student-faculty interaction in research universities: differences by student gender, race, social class, and first-generation status. Res. High. Educ. 50, 437–459. doi: 10.1007/s11162-009-9127-x

Kuh, G. D. (2009). What student affairs professionals need to know about student engagement. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 50, 683–706. doi: 10.1353/csd.0.0099

Malcom-Piqueux, L. (2015). Application of person-centered approaches to critical quantitative research: exploring inequities in college financing strategies. N. Direct. Instit. Res. 2015, 59–73. doi: 10.1002/ir.20086

Martinez, A., and Hallmark, T. (2018). Spotlight on MSIs: Turning Student Activism into Votes. Available online at: https://cmsi.gse.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/MSIvote_2018.pdf

Merisotis, J. P., and O'Brien, C. T. (1998). Minority-Serving Institutions: Distinct Purposes, Common Goals. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement (2012). A Crucible Moment: College Learning & Democracy's Future. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Njoku, N., Butler, M., and Beatty, C. C. (2017). Reimagining the historically black college and university environment: exposing race secrets and the chains of respectability and othermothering. Int. J. Qualit. Stud. Educ. 30, 783–799. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2017.1350297

Purce, T. L. (2014). “The habit of civic engagement,” in Civic Engagement, Civic Development, and Higher Education, ed. J. N. Reich (Washington, DC: Bringing Theory to Practice), 13–17.

Roll, N. (2017). Retaliation for Taking a Knee? Available online at: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/10/12/cheerleaders-knelt-during-anthem-were-removed-field-next-week

Rudolph, F. (1977). Curriculum: A History of the American Undergraduate Course of Study Since 1636. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Saltmarsh, J., and Zlotkowski, E. (2011). Higher Education and Democracy: Essays on Service-learning and Civic Engagement. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Sax, L. J., Bryant, A. N., and Harper, C. E. (2005). The differential effects of student-faculty interaction on college outcomes for women and men. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 46, 642–657. doi: 10.1353/csd.2005.0067

Keywords: civic engagement, minority serving institution, student activism, free speech, student engagement

Citation: Fassett KT, Priddie C, BrckaLorenz A and Kinzie J (2018) Activists, Non-activists, and Allies: Civic Engagement and Student Types at MSIs. Front. Educ. 3:103. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00103

Received: 02 June 2018; Accepted: 12 November 2018;

Published: 03 December 2018.

Edited by:

Marybeth Gasman, University of Pennsylvania, United StatesReviewed by:

Sylvia Méndez-Morse, Texas Tech University, United StatesCopyright © 2018 Fassett, Priddie, BrckaLorenz and Kinzie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kyle T. Fassett, a2Zhc3NldHRAaXUuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.