- Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning, Deakin University, Geelong, VIC, Australia

The notion of “transparency” has been extensively critiqued with respect to higher education. These critiques have serious implications for how educators may think about, develop, and work with assessment criteria. This conceptual paper draws from constructivist and post-structural critiques of transparency to challenge two myths associated with assessment criteria: (1) transparency is achievable and (2) transparency is neutral. Transparency is interrogated as a social and political notion; assessment criteria are positioned as never completely transparent texts which fulfill various agendas. Some of these agendas support learning but this is not inevitable. This conceptual paper prompts educators and administrators to be mindful about how they think about, use, and develop assessment criteria, in order to avoid taken-for-granted practices, which may not benefit student learning.

Introduction

In higher education, it is generally considered desirable for assessment criteria to be “transparent” (Jackel et al., 2017). In this sense, transparency means that educators are explicit about their expectations for assessment and students therefore can see what it is they need to achieve. For many, a significant reason for providing transparent criteria is to help students learn. Jonsson (2014, p. 840) summarizes this approach as: “Student awareness of the purpose of the assessment and assessment criteria is often referred to as transparency … in order to educate and improve [a] student's performance, all tasks, criteria and standards must be transparent to both students and teachers.” [italics ours] However, transparency as a concept may be more than it seems. The complexities and nuances of the transparency agenda have been explored and critiqued with respect to higher education in general (Strathern, 2000; Brancaleone and O'Brien, 2011; Jankowski and Provezis, 2014) and assessment in specific (Orr, 2007), primarily through a post-structural lens. To the best of our knowledge, this previous work has not directly concerned the transparency of assessment criteria. In landscapes where the use of rubrics have become taken-for-granted, it is worth interrogating more closely some of the underpinning assumptions around transparency of assessment criteria.

This paper seeks to overturn myths associated with transparency of assessment criteria. We challenge the notion that transparent assessment criteria are (a) possible and (b) an unqualified good. While we draw from published critiques of transparency, we are not calling for wholesale abandonment of explicating criteria in text; we acknowledge that the notion of transparent assessment criteria serves valuable purposes in making teachers accountable and in providing direction for students. Rather, we suggest that the way transparency is enacted in assessment criteria in the daily practice of university teaching and learning, may not take account of its limitations. To make this argument, we outline the general landscape of written assessment criteria in higher education. We then problematise the notion of transparent assessment criteria, with particular attention to these two myths. Our arguments are illustrated with a critical examination of a bioethics rubric. We do not choose this example to highlight flaws with a particular rubric design, but to illuminate how the notion of transparency might lead to poor use of rubrics. Finally, we explore implications by offering some considerations for educators, managers and quality improvement staff when developing or working with rubrics.

Written Assessment Criteria in Higher Education

In higher education, transparency of assessment criteria is part of a larger movement from assessment being “secret teachers' business” to something that is made public to students and the wider community (Boud, 2014). In particular, tertiary institutions in countries such as Australia and the United Kingdom have moved to the explicit articulation of course and unit learning outcomes. Assessment and associated criteria present a means for assuring that the students can meet these learning outcomes. This is part of a significant change in assessment practice, whereby students are graded against a standard rather than against each other (Sadler, 2009).

University assessors judge student work against a series of criteria (Sadler, 2009), which reference academic standards. In order for assessment criteria (or standards) to be “transparent,” they are recorded, generally in writing, and shared between students, educators and administrators. Increasingly, explicit written assessment criteria take the form of rubrics; these are a pervasive presence in the higher education literature (Dawson, 2015). This literature suggests that: students like the provision of rubrics (Reddy and Andrade, 2010); students consider them helpful (Reddy and Andrade, 2010); and that rubrics may improve learning (Panadero and Jonsson, 2013). From a student perspective, teachers sharing these types of written expressions of assessment criteria are the primary means of coming to know the standards for the course or unit. Reading the rubric may be the only time a student will engage or think about the quality of what they are trying to achieve.

In summary, assessment criteria provide judgement points for an assessment task, drawing from academic standards. Through written form such as rubrics, educators seek to make assessment criteria “known” to students. This is also intended to have educative effects on the students and build their awareness of the standard. The written assessment criteria are therefore the focus of this paper, as they are both a ubiquitous part of practice and the means whereby educators seek to achieve “transparency.”

Transparency is Taken-For-Granted

The taken-for-granted benefits of transparent standards and criteria are a “normalized discourse” in higher education (Orr, 2007, p. 646). For example, a 2017 literature review of higher education assessment notes: “… when [standards] are clearly articulated, and when students engage with them, performance standards help improve transparency of assessment and student learning…” [italics ours] (Jackel et al., 2017, p. 18). Likewise, (Rodríguez-Gómez and Ibarra-Sáiz, 2015, p. 4) describe transparency as a foundational principle for assessment, noting: “Assessment is carried out against a set of transparent rules, standards and criteria which guide students to achieve the required learning outcomes…” [italics ours]. It can be seen from this phrasing that transparency is regarded as a general good. Indeed, transparency is paired with learning as a desirable outcome. And, it could be argued, why not? As mentioned, there is evidence that clear criteria encapsulated in rubrics help both educators' communication of the standards and students' learning (Reddy and Andrade, 2010; Panadero and Jonsson, 2013; Jonsson, 2014). So then, why should we question it? Does it not benefit ourselves and our students to clearly articulate what it is they are supposed to do?

We suggest that by thinking more deeply about transparency, we can improve the way we use assessment criteria in our teaching. There is significant post-structural critique regarding the discourse of transparency, indeed transparency has already been problematized with respect to assessment and higher education (Orr, 2007; Jankowski and Provezis, 2014). Likewise there has been extensive acknowledgements of the inherent challenges of being explicit (O'Donovan et al., 2004; Sadler, 2007; Torrance, 2007). However, experienced educators are not necessarily aware of this literature when they work with standards or criteria (Hudson et al., 2017). We think it is therefore necessary to interrogate the taken-for-granted nature of transparency with specific reference to assessment criteria.

We challenge two myths about transparency in order to help express assessment criteria more productively. The first myth is that transparency is achievable and the second is that transparency is neutral.

Myth 1: Transparency is Achievable

Possibly the most pervasive assumption about any form of transparency is that it makes everything visible, like shining a light into a dark room. This may mean that when academics invoke transparency with respect to assessment criteria, they sometimes assume that there are objective standards, which can be precisely and accurately described. Academic standards, however, have been acknowledged to be social constructions, which have a “necessarily elusive and dynamic nature … continuously co-constructed by academic communities and ferociously difficult to explain to a lay audience.” (Bloxham and Boyd, 2012, p. 617). Already this notion of dynamic and tacit standards necessarily challenges the notion of making everything visible. While it could be argued that written assessment criteria is a means of making our social truths explicit, this seems to somewhat miss the point. We think there are other, more complex forces at work. We offer three arguments that suggest that rubrics and similar can never make everything visible.

1) There is knowledge that cannot be expressed

One of the most common challenges in writing assessment criteria is capturing holistic tacit knowledge; and many argue that this knowledge is impossible to capture explicitly (O'Donovan et al., 2004; Orr, 2007; Sadler, 2009; Bloxham and Boyd, 2012; Bloxham et al., 2016; Hudson et al., 2017). Any expression of standards and criteria necessarily simplifies and clarifies the complex nature of work, in order to communicate it. That is, by capturing knowledge in words, we lose some sense of it. O'Donovan et al. (2004) describe how they once believed that: “making assessment criteria and standards transparent … could be achieved fairly simply through the development and application of explicit school-wide assessment criteria and grade descriptors.” (O'Donovan et al., 2004, p. 327) However, they came to learn that tacit knowledge was impossible to pin down, despite considerable effort.

2) Transparent criteria are in the eye of the beholder

We suggest that if academic standards are socially constructed and based on tacit, dynamic knowledge, then how these standards are perceived and how the knowledge is understood, depends on an individual's social history and standing. This applies equally to assessment criteria. As Jankowski and Provezis (2014, p. 481) note: “ …the request for assessment information to be transparent is challenging because employers, students, institutions and policy makers have different understandings of … what it means to be transparent. In other words, what may be transparent for one group may not be for another.” This comes to a matter of interpretation whereby we bring our frames of reference to make sense of criteria (Tummons, 2014).

How students make sense of criteria may inform their perspective as to what constitutes “transparent” criteria. A study of students' perspectives of assessment criteria suggests students have divergent ways of engaging with criteria (Bell et al., 2013). On the one hand, there were those students who wished to use the rubric as a recipe; and on the other, there were those who embraced a more complex idea of standards, closer to an educator's perspective. These two groups spoke about how they interacted with the written assessment criteria in very different ways. We suggest that for some students, the notion of transparency related to the assignment, and for other students, transparency related to the underlying standards.

Moreover, the written expression of the criteria can be interpreted in diverse ways, depending on how much the student already knows. Often students, as novices in the field, may not be able to make sense of the language used in rubrics or similar as they do not have the necessary repertoires of understanding (which may be developed during their studies). In other words, students' ability to “see through” to the assessment criteria, depends on their a priori knowledge; what is transparent for an expert may be opaque to the student. How much a rubric can prompt understanding and learning is therefore dependent on the student as much as the transparency of the written criteria.

3) Making some criteria transparent makes other criteria opaque

Strathern's (2000) critique of transparency of audit in higher education asks the question: “what does visibility conceal?” This is one of the key challenges to transparency: you cannot make a choice about what you say, without making a choice about what you do not say. The text of any written assessment criteria suggests that particular forms of knowledge are particularly important: students should be paying attention to this. In doing so, without mentioning it, they direct students' attention away from that. So the whole notion of transparency must inevitably be based on highlighting some things and obscuring others. To use post-structural language, making assessment criteria transparent both legitimizes and delegitimizes particular forms of knowledge. We suggest this indicates that transparency is not neutral—and this is exactly the point that is explored within our next myth.

Myth 2: Transparency is Neutral

Orr (2007) argues that the discourse of assessment in higher education is mostly rooted in positivism, with its emphasis on attainment of measurable standards that are constant over time. “Transparency” stems from this discourse, which is underpinned by the notion that standards are knowable, expressible and measurable; we have previously described flaws in this perspective. Alternative discourses position assessment as a socio-political act (Orr, 2007; Raaper, 2016). The transparency movement can therefore be seen as part of a political system. This is not in itself “bad;” after all, the need for transparency is what prevents our assessments from being “secret” (Boud, 2014) and assessors from abusing their authority (Raaper, 2016) as well as offering students a more equal footing (Ajjawi and Bearman, 2018). However, this is also a system where teachers feel pressurized and constrained by assessment (Raaper, 2016) and students “game the system”(Norton, 2004).

We suggest that it is worth being cautious about seeing transparency as a benefit in and of itself. Neoliberal critiques suggest that “transparency” can also be considered a form of scrutiny (Strathern, 2000). As mentioned above, we do not see “scrutiny” as an evil or even a necessary evil; scrutiny also ensures that assessments are not deliberately obscured and abused. However, we propose that various groups can use the sharing of written assessment criteria to fulfill diverse agendas and this use of transparent written criteria can be seen as a form of control. Hence it is worth asking: which agendas do the written criteria serve? We provide three ways of viewing transparent assessment criteria, which challenge their apparent neutrality.

1) Transparent assessment criteria as governance

For some, the very notion of transparency can be seen as contributing to a system that seeks to commodify and control education (Brancaleone and O'Brien, 2011). From this view, transparency enacted through written assessment criteria permit institutions to enforce governance. By ensuring assessment criteria are visible, institutions have a means to control teachers and teaching (Jankowski and Provezis, 2014). We suggest that this may lead to positive learning outcomes, as transparent criteria allow courses, faculties and institutions to ensure that standards are met. However, it may also lead to problems with teaching and therefore, learning. For example, in an attempt to secure comparability and equity, the same rubric may be used across different tasks in a course or unit or even an entire discipline. Attempts to provide these comparable criteria can sometimes produce deep frustration from assessors, lecturers and students if the generic approaches do not capture the nuance of the task at hand. Hudson et al. (2017) describes the need for “conceptual acrobatics,” where teachers' professional judgements about what to address at a particular time with particular students is in conflict with “transparent” and therefore pre-set learning outcomes. This illustrates how, on occasion, a desire for comparable and transparent standards might lead to the de-professionalization of teaching.

2) Transparent assessment criteria as a means of student control (and control of students)

Written assessment criteria allow the “secret assessment business” to become shared and public. In this way, making assessment criteria transparent cedes control of assessment to students. This is generally a good thing: through reading and working with rubrics or similar, students become able to form their own perspectives on why and how their work meets the standard. Ideally, we embrace this and allow students to co-construct rubrics with teachers. In this process, students and teachers work together to express the criteria by which work will be judged (Fraile et al., 2017). We would regard this as an example of where transparent assessment criteria is beneficial to learning.

The students themselves can use the written criteria to control their own experiences. Many students seek to use the written criteria to pass the assessment rather than learn (Norton, 2004; Bell et al., 2013). Academics are all familiar with students who come, checklist in hand, saying “why did I get this mark?” Sometimes this is valuable, and sometimes students are arguing the letter rather than the spirit of the text. This is another consequence of seeking transparency, which is not necessarily aligned with learning, but which illustrates how visible assessment criteria give control to students.

However, seeking transparency may also prompt educators to tightly specify levels of achievement; in some instances, this may be a misguided attempt to control students' outputs in a way that helps them meet the criteria, but not necessarily learn (Torrance, 2007). The danger here is that seeking transparency is conflated with reductiveness: “fine-grained prescription, atomised assessment, the accumulation of little ‘credits' like grains of sand, and intensive coaching toward short-term objectives, are a long call from the production of truly integrated knowledge and skill.” (Sadler, 2007, p. 392) We do not suggest reductive expressions of criteria are necessarily the result of making assessment “transparent,” but that they remain a possibility (and thus, frequently, a reality).

3) Transparency controls how students see knowledge

As mentioned, the standards to which our criteria refer, can be considered social constructs. They shift and change over time. By invoking transparency as simply “seeing through,” we may inadvertently create the notion that criteria are fixed, durable and objective (Ajjawi and Bearman, 2018). However, this is not the case: we have already described how some forms of knowledge are permitted whilst others are constrained. This is not a good or bad thing in itself, although it can lead to both desirable and undesirable outcomes. For example, in the 1800s, the gold standard for being a lawyer might have included being a man from a certain class. No matter how clear or transparent the criteria, these standards would not be defendable in our current day and age. Equally, our 2018 criteria may reflect unconscious social attitudes of our era. On the other hand, criteria can deliberately try to drive social change. For example, medical curricula that have holistic criteria around professionalism may deliberately be seeking to change the discourse around what it means to be “a good doctor.”

Our discourses of transparency may also affect how students see knowledge. Saying that our assessment criteria are “transparent” reveals how we understand knowledge itself, or our epistemic beliefs, and therefore power. From an educational perspective, what we want to avoid, is giving our students the sense that knowledge is fixed and stable. Higher education aspires to develop students' personal epistemologies (Hofer, 2001), so that students can come to understand multiple views and the dynamic nature of knowledge. How we talk about our assessment criteria and enact transparency may influence how our students come to understand what knowledge means.

What The Myths of “Transparency” Mean on the Ground: the Bioethics Rubric Example

Taken together, we have mounted a case that transparent assessment criteria are not true reflections of some kind of objective truth but texts that are necessarily open to interpretation and which allow control and scrutiny. We use an extract from a bioethics rubric (Hack et al., 2014; Hack, 2015) to explore how these critiques of transparency collide with the “taken-for-granted” nature of transparent assessment criteria. That is, we look at the tensions between a socio-political frame and assessment criteria as explicit guidance from teachers to learners about the assessment requirements.

The Sample Rubric

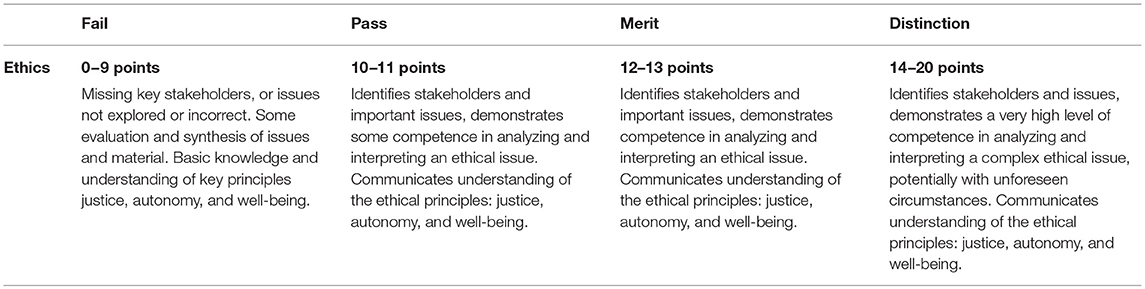

For this purpose, the sample rubric is not intended to illustrate outstanding or particularly poor practice. Rather, it represents an “on the ground” illustration of a thoughtfully written assessment criterion—typical of many rubrics. The whole (originally co-constructed) rubric is available through a Creative Commons license (Hack, 2015). We present one row—“ethics”—in Table 1. It relates to the following assignment brief: “Prepare a critical examination of the key issues on a current topic in medical or health science which raises ethical issues. You should draw extensively on the literature to present: an introduction to the technology or science that underpins the issue, the key ethical aspects with reference to ethical theory, the implications for policy decisions, practice and/or regulatory frameworks.”(Hack et al., 2014) The following analysis illustrates how these different notions of transparency are enacted within this small piece of text, and from this, we draw out implications for learning and teaching. We have deliberately chosen a row pertaining to a complex aspect of the task.

Table 1. Sample row from bioethics rubric reproduced from Hack (2015).

Illustration of the Arguments

In the following sections, we draw out and illustrate how the text of this rubric supports our earlier contentions. Italics indicate the key arguments as discussed in previous sections.

The assumption underpinning the notion of transparent assessment criteria is that, by educators expressing what students need to achieve, students will come to know the standards behind the criteria and hence be able to improve their performance on the assessment task (i.e., “see through” the criteria to the standards). At broad brushstroke, this co-constructed written criterion (Table 1) may meet this aim. However, there are several different sorts of complex knowledge that are necessarily simplified and represented in this text. There are references to “ethical issues” and “key principles of justice, autonomy and well-being,” which pertain to the content knowledge of the course. There are verbs that articulate the type of generic intellectual acts that students are supposed to achieve, such as “synthesise” and “evaluate.” There are also descriptors of the expected standard: “basic,” “some competence” and “very high level of competence.” All these different elements come together in the statement “demonstrates some competence in analyzing and interpreting an ethical issue.” This statement contains a great deal of tacit knowledge. In other words, while the rubric comes to some sense of what is intended, it does not (and cannot) explicate it entirely as it contains knowledge that is not documentable. This has been noted beforehand (O'Donovan et al., 2004; Sadler, 2007) but it is worth repeating as the literature shows that educators can make the assumption (O'Donovan et al., 2004; Hudson et al., 2017) that: (a) if it is in the rubric, then assessors and students should know what is expected and b) if they expend enough energy on explicating it, then there will be clarity about the standards. However, these are part of the myth of transparency being achievable. Others have suggested useful means to support students to come to know standards beyond telling, such as the use of exemplars (Carless et al., 2018). Likewise, the act of co-construction comes a long way toward addressing “knowing” that isn't the same as “making transparent.”

Exemplars, co-construction and other pedagogical supports can also help with challenges resulting from transparency being in the eye of the beholder. Let us consider a statement from the distinction column in Table 1: “…demonstrates a very high level of competence in analyzing and interpreting a complex ethical issue, potentially with unforeseen circumstances.” So, for the educator, the rubric expresses a general (but not complete) view of what they are expecting. For one student, with a good repertoire of ethics and a particular set of epistemic beliefs, this rubric may fulfill some educative purpose. That is, through reading the rubric, they may learn that part of ethical issues is trying to forecast “unforeseen circumstances.” On the other hand, a student who is more novice may struggle to grasp what an “unforeseen circumstance” might even be. Similarly, “a high level of competence” may mean entirely different things to different people depending on their own competence in the area (Kruger and Dunning, 1999). The most significant implication of assessment criteria being read differently by different people, is that written criteria are best understood by those who already have the knowledge to fulfill the requirements. In other words, those who most need to learn what the standards are, are likely more mystified by assessment criteria than those who already have a grasp of the course content. This again returns to the point that providing the rubric is insufficient: the concepts within it must be supported by the rest of the curriculum as well as assessment artifacts such as exemplars. In our particular example, the rubric is co-constructed: in this way, students and staff jointly contribute to the tacit understandings underpinning the rubric and so come to a shared view of the expectations set by the assessment criteria. However, this only mitigates the challenge for those immediately involved in the construction, it does not remove it.

We have suggested that assessment criteria always operate in a broader social landscape. For example, from a content perspective, these assessment criteria legitimate a certain view of ethics. The decision to focus on “justice, autonomy, and well-being” and not other ethical frameworks may be an appropriate educator choice against the curricula, but what is being excluded is not captured within the written criteria and hence is made invisible. Similarly, the assessment—and the criteria—emphasize an academic discussion, not a personal reflection or some other mode of expression. Again, this legitimizes the academic form and delegitimizes the alternatives. We do not suggest that there is anything wrong with this—indeed it is inevitable—but to make the point that making some criteria transparent, makes other criteria opaque. Once again this comes to the point that transparency is not achievable, but it also underlines our argument that transparency is not neutral.

We now turn to a more political frame. Drawing again from our illustration in Table 1, we seek to explore transparency as governance. There are many ways in which assessment criteria like these permit control and scrutiny of teacher activity. For example, this row in the rubric could be provided in an audit as evidence of meeting requirements to teach bioethics. As another example, institutional policy might dictate that changes to units of study, often including rubrics, must be submitted to scrutiny by committee almost a year in advance to ensure they represent the university sanctioned standards and thereby limiting teacher' agility and control. Rubrics also work as coordinating agents across classes, students and teachers—to ensure consistency. While this consistency is at best fleeting (Tummons, 2014), the rubric may limit the ability of teachers to modify assessment criteria to incorporate discussions with a particular cohort. This is not to say that all control and scrutiny leads to negative consequence. Moderation relies on these types of rubrics to coordinate and control grading processes. If this rubric was used to promote a discussion of what educators regarded as meeting the “distinction” criteria across the teaching team, then we would see this as a valuable form of governance, which ultimately leads to better teaching and learning. Note that there is an overlay between transparency as governance and the recognition that some knowledge is not documentable. If institutions believe that transparency is achievable, then this may create tensions in how the assessment criteria are used for governance.

While transparent assessment criteria may provide a means for institutional “scrutiny” and “control,” they also allow student control and control of students, depending on the broader institutional context. In our example, as a co-constructed rubric, students necessarily have some control over these criteria; it promotes their ownership and investment as well as their understanding. Key terms, such as “stakeholders” and “ethical issues” are likely to have been discussed and possibly argued for. As mentioned, they also can use these criteria to query grades (“I have ‘demonstrated some competence in analyzing and interpreting an ethical issue' why aren't I passing?”).

However, assessment criteria equally control students. As is illustrated by our one row from the rubric, they highlight what the student should privilege. What is now deemed important in the assignment are: discussion of stakeholders, analysis and interpretation of ethical issues; and communication of “understanding” ethical principles. Students will now fulfill this. This is not necessarily problematic—indeed it is arguably the point of education—but it may become so if the assessment criteria are prescribed so tightly, they become a recipe book. For example, in our illustrative bioethics assignment, it would be entirely counterproductive to replace this rubric with a series of very tight criteria regarding analysis of a complex ethical issue; the point of learning ethical thinking is to manage complex nuance. We would suggest that, outside of particular focussed skills such as resuscitation or pipetting, analytical (atomised) written criteria should allow students to make their own meanings, and develop their own judgements about what constitutes quality. Another means whereby a rubric may control students, is if it is provided to students with minimal explanation, then feedback returned to students again with minimal explanation, simply using the text in the rubric. In these circumstances, students are primed to explicitly follow the rubric thus limiting creativity and exploration of other forms of ethical practice. Here the use of the rubric is inadvertently controlling how students see knowledge.

In our view, our illustrative rubric mostly supports a dynamic view of knowledge. The process of co-construction reveals the dynamic nature of criteria, which are devised and developed through consensus and discussion. Moreover, the verbs “communicates,” “analyses” and “interprets” positions knowledge as constructed rather than “hard facts.” On the other hand, the language of this criterion does present some absolutes. For instance, it subtly but distinctly privileges “justice, autonomy and well-being” as “the” ethical principles; whether they are or not is not the question at hand. What we are underlining is that the text suggests that a framework is fixed and durable. In short, written criteria contain subtle (and not so subtle) messages about the nature of content knowledge in specific and epistemology in general, and that as educators we should try and take account of this.

Implications of the Illustrative Example

This examination of a small sample of text shows that a single row in the rubric can fulfill one part of the transparency agenda—by ensuring that educators' broad expectations are communicated to students and students come to some understanding of the underlying standards. This can be done without “complete” transparency; the text is not completely explicit, and nor does it need to be. However, from a socio-political perspective, the rubric is doing so much more. It allows institutions, educators and students to control each other. This is not necessarily a bad thing, what we suggest is critical is that educators (and ultimately students) be more aware of how objects such as rubrics operate within the educative space. The overall implication is that it may be more useful for educators to think about how the criteria will be used and by whom, when they are considering how the written criteria reflect the tacit standard. In other words, how will students (and teachers) “see with” the criteria, rather than “see through” them.

From “Seeing Through” to “Seeing With”

We have mounted a case against a simplistic understanding of assessment criteria that sees transparency as an unqualified good. We suggest that discourses and processes of transparency are not a matter of expressing with greater clarity. Instead, written assessment criteria form part of a much larger social and political landscape. “Making transparent” is neither neutral, nor in fact, possible. So what does all this mean for assessment practice?

There are considerable implications for how we develop and use assessment criteria. The first inference is that educators can reflexively consider their own views of assessment criteria and transparency, and how these are reflected (or not) in what they do. To give an example of this type of reflexive thinking, we will describe what we ourselves as educators see as desirable. We would like our assessment criteria to allow our students to make their own meanings about work in relation to holistic dynamic standards (Ajjawi and Bearman, 2018). We design processes to incorporate the written assessment criteria into teaching, building on all the tasks (and associated feedback opportunities) that we have provided during teaching, such as through formative self and peer assessment. At the same time, we want written assessment criteria to provide ourselves, our fellow markers and our students, a shared sense of what we think is good work. We also want to open ourselves to the opportunity for our students to teach us about the standards, not just the other way around. To this end, we want ourselves and our students to “see with” criteria, not “see through” them.

Ways to achieve our aspirational use of assessment criteria are already described within the literature (e.g., Norton, 2004; O'Donovan et al., 2004). Sadler (2009) writes: “Bringing students into a knowledge of standards requires considerably more than sending them one-way messages through rubrics, written feedback or other forms of telling. It requires use of the same tools as those employed for setting, conveying and sharing standards among teachers: exemplars, explanations, conversation and tacit knowing.” (Sadler, 2009, p. 822) While these dialogs are how expert educators help their students make meaning of standards, these clearly are not the same as “seeing through” to the criteria. Designing activities for students to “see with” criteria, (i.e., the pedagogical activities that support a rubric), goes a long way toward the development of a shared understanding of the standards for an assessment.

We also recognize that the pragmatics of assessment design may mean that control over assessment tasks and associated criteria may not be possible (Bearman et al., 2017). However, even in the most constrained of circumstances, educators (and students) can discuss their criteria with both students and colleagues. With respect to students, the explanation of the criteria can be important for “transparency” (Jonsson, 2014), and may provide an opportunity to enhance or adjust already established tasks and rubrics. With respect to colleagues, it can highlight the role the criteria take in shaping and controlling student and educator behavior. It is easy to fall into assessment practices that are the “way things are done around here”(Bearman et al., 2017). Critically examining the words for taken-for-granted assumptions may be one way to ensure we do not automatically continue unproductive practices.

To this end, we suggest three framing questions by which educators can approach assessment criteria. These allow them to align with the transparency discourses but also allow them to think more deeply about what “being transparent” might entail. Questions to guide educators are:

1) What is my agenda with the text of this criteria and what other agendas might these written criteria serve?

2) What might be learnt from these written criteria about the nature of knowledge?

3) By what means (e.g., activities, assessment designs, dialogs) will students be given the opportunity to “see with” written criteria?

These questions do not seek to make assessment criteria “transparent” but provide a process to challenge assumptions and promote student benefit. Through this, educators may find a means to adapt notions of “transparency” to their own contexts.

There are also more radical implications of this work. If transparency is unattainable, then reflexivity, criticality and co-construction are necessarily implied when shifting to “seeing with” rather than “seeing through.” Quality assurance processes could seek to explore the educational processes built in and around the assessment criteria, rubrics and standards. From this perspective, written assessment criteria should be accompanied by co-constructive processes that involve discussion of quality, the use of exemplars, and nested formative tasks with dialogic feedback processes that help develop shared understandings of the standards. These processes become the markers of a quality learning and teaching design rather than the presence or otherwise of a rubric (or similar). Similarly, quality assurance processes could favor dialog with staff about the intended and unintended consequences of how such processes play out on the ground—therefore informing future design in a collaborative way. Further, from a political perspective, managers need to attune to the ways in which rubrics can act as disciplinary tools—for example when certain forms are mandated without discussion and where the form the rubric takes to honor consistency trumps professional judgement on the ground. Reflexivity by managers is needed to acknowledge the level of control as well as criticality and humility to question whether such control does in fact lead to better educational processes or merely reduces perceived variability. These implications have real consequences for institutions including an imperative for staff time to be allocated to designing interactive forms of education rather than transmissive ones that aim to do more with less.

Conclusions

This paper has explored the nature of transparency with respect to assessment criteria. We have drawn from others' critiques of transparency and assessment criteria to present a case for educators to think about transparency differently. We suggest that transparency is neither bad nor good, but is a socio-political construction. Therefore, assessment criteria can never be truly transparent, nor would we want them to be. Instead, we may want to ask ourselves: What agendas can assessment criteria serve? How do they direct the students and ourselves? What do they hide?

Author Contributions

MB and RA both contributed to the ideas underpinning this article. MB wrote the primary draft. RA contributed additional text and both revised for important intellectual content.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Ajjawi, R., and Bearman, M. (2018). “Problematising standards: representation or performance?,” in Developing Evaluative Judgement in Higher Education: Assessment for Knowing and Producing Quality Work, eds D. Boud, R. Ajjawi, P. Dawson, and J. Tai (Abingdon: Routledge), 41–50.

Bearman, M., Dawson, P., Bennett, S., Hall, M., Molloy, E., Boud, D., et al. (2017). How university teachers design assessments: a cross-disciplinary study. High. Educ. 74, 49–64. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0027-7

Bell, A., Mladenovic, R., and Price, M. (2013). Students' perceptions of the usefulness of marking guides, grade descriptors and annotated exemplars. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 38, 769–788. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.714738

Bloxham, S., and Boyd, P. (2012). Accountability in grading student work: securing academic standards in a twenty-first century accountability context. Br. Educ. Res. J. 38, 615–634. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2011.569007

Bloxham, S., den-Outer, B., Hudson, J., and Price, M. (2016). Let's stop the pretence of consistent marking: exploring the multiple limitations of assessment criteria. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 41, 466–481. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1024607

Boud, D. (2014). Shifting views of assessment: from secret teachers' business to sustaining learning,” in Advances and Innovations in University Assessment and Feedback, eds C. Kreber, C. Anderson, N. Entwhistle, and J. McArthur (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh), 13–31.

Brancaleone, D., and O'Brien, S. (2011). Educational commodification and the (economic) sign value of learning outcomes. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 32, 501–519. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2011.578435

Carless, D., Chan, K. K. H., To, J., Lo, M., and Barrett, E. (2018). “Developing students' capacities for evaluative judgment through analysing exemplars,” in Developing Evaluative Judgment in Higher Education: Assessment for Knowing and Producing Quality Work, eds D. Boud, R. Ajjawi, P. Dawson and J. Tai (London: Routledge), 108–116.

Dawson, P. (2015). Assessment rubrics: towards clearer and more replicable design, research and practice. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 42, 347–360. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1111294

Fraile, J., Panadero, E., and Pardo, R. (2017). Co-creating rubrics: the effects on self-regulated learning, self-efficacy and performance of establishing assessment criteria with students. Stud. Educ. Eval. 53, 69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.03.003

Hack, C. (2015). Analytical rubrics in higher education: a repository of empirical data. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 46, 924–927. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12304

Hack, C., Devlin, J., and Lowery, C. (2014). Analytical rubrics: a repository of empirical data. doi: 10.13140/2.1.4647.7766

Hofer, B. K. (2001). Personal epistemology research: implications for learning and teaching. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 13, 353–383. doi: 10.1023/A:1011965830686

Hudson, J., Bloxham, S., den Outer, B., and Price, M. (2017). Conceptual acrobatics: talking about assessment standards in the transparency era. Stud. High. Educ. 42, 1309–1323. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1092130

Jackel, B., Pearce, J., Radloff, A., and Edwards, D. (2017). Assessment and feedback in higher education: a review of literature for the higher education academy.

Jankowski, N., and Provezis, S. (2014). Neoliberal ideologies, governmentality and the academy: an examination of accountability through assessment and transparency. Educ. Philos. Theory 46, 475–487. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2012.721736

Jonsson, A. (2014). Rubrics as a way of providing transparency in assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 39, 840–852. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2013.875117

Kruger, J., and Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 77, 1121–1134. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Norton, L. (2004). Using assessment criteria as learning criteria: a case study in psychology. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 29, 687–702. doi: 10.1080/0260293042000227236

O'Donovan, B., Price, M., and Rust, C. (2004). Know what I mean? Enhancing student understanding of assessment standards and criteria. Teach. High. Educ. 9, 325–335. doi: 10.1080/1356251042000216642

Orr, S. (2007). Assessment moderation: constructing the marks and constructing the students. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 32, 645–656. doi: 10.1080/02602930601117068

Panadero, E., and Jonsson, A. (2013). The use of scoring rubrics for formative assessment purposes revisited: a review. Educ. Res. Rev. 9, 129–144. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2013.01.002

Raaper, R. (2016). Academic perceptions of higher education assessment processes in neoliberal academia. Crit. Stud. Educ. 57, 175–190. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2015.1019901

Reddy, Y. M., and Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 35, 435–448. doi: 10.1080/02602930902862859

Rodríguez-Gómez, G., and Ibarra-Sáiz, M. S. (2015). “Assessment as learning and empowerment: towards sustainable learning in higher education,” in Sustainable Learning in Higher Education, eds M. Peris-Ortiz and J. M. Merigo Lindahl (Springer), 1–20.

Sadler, D. R. (2007). Perils in the meticulous specification of goals and assessment criteria. Assess. Educ. Princip. Policy Pract. 14, 387–392. doi: 10.1080/09695940701592097

Sadler, D. R. (2009). Grade integrity and the representation of academic achievement. Stud. High. Educ. 34, 807–826. doi: 10.1080/03075070802706553

Strathern, M. (2000). The tyranny of transparency. Br. Educ. Res. J. 26, 309–321. doi: 10.1080/713651562

Torrance, H. (2007). Assessment as learning? How the use of explicit learning objectives, assessment criteria and feedback in post-secondary education and training can come to dominate learning. Assess. Educ. Princip. Policy Pract. 14, 281–294. doi: 10.1080/09695940701591867

Keywords: assessment criteria, Transparency, higher education, standards, rubrics

Citation: Bearman M and Ajjawi R (2018) From “Seeing Through” to “Seeing With”: Assessment Criteria and the Myths of Transparency. Front. Educ. 3:96. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00096

Received: 01 May 2018; Accepted: 18 October 2018;

Published: 05 November 2018.

Edited by:

Anders Jönsson, Kristianstad University, SwedenReviewed by:

Sue Bloxham, University of Cumbria, United KingdomGavin T. L. Brown, University of Auckland, New Zealand

Copyright © 2018 Bearman and Ajjawi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Margaret Bearman, margaret.bearman@deakin.edu.au

Margaret Bearman

Margaret Bearman Rola Ajjawi

Rola Ajjawi