- Nucleus of Investigation and Social and Educational Action, Center of Education and Human Sciences, Federal University of São Carlos, São Carlos, Brazil

The study aimed to provide scientific evidence to support school actions for the prevention of gender-based violence (GBV), specifically in the Brazilian context. Brazil presents high GBV indexes, ranking fifth in the world in femicide. With regard to violence in school, girls are the main victims of sexual-based violence and GBV. Preventive actions must be taken to avoid such occurrence. Searches conducted in Brazilian scientific databases retrieved no review of research on GBV prevention, so we conducted a thorough review of the topic, encountering a small number of articles in Brazilian databases. National and international scientific productions on the theme were compared to identify if the low production is characteristic only in Brazil or in the international context as well. Searches were conducted in Brazilian and international databases using GBV and school-related descriptors. A national data search retrieved 431 entries, while 222 papers were obtained in the international literature. The inclusion criteria for the analyses was the mention, in the abstract, of any form of action within school addressing GBV prevention. This screening selected 11 studies in the Brazilian databases and 30 articles in the international literature. Transformative or exclusionary elements were identified in the texts, focusing on different school levels and also lawmaking. Because of restrictions imposed by the data set, a descriptive analysis was conducted. In the international literature, it was possible to identify that recent research has been analyzing actions developed in schools aiming for GBV prevention and some of their impacts. Brazilian literature has been focusing primarily on describing actions rather than evaluating their impacts or describing GBV prevalence. The targeted population includes teachers, sports coaches, male and female students of different educational levels, whole school community, family, and surrounding communities. The actions described in the international dataset are most frequently conducted in an extracurricular context and are primarily focusing on raising awareness about GBV and on providing information. The Brazilian studies indicate few actions conducted within the school. The analysis indicated characteristics in school-actions that contribute to preventing and overcoming GBV, such as working with the whole school community, empowering women and strengthening egalitarian masculinities, bystander training, and implementing laws and policies.

Introduction

The study initially aimed to characterize Brazilian scientific production regarding schools' educational actions to prevent gender-based violence (GBV), in order to provide a synthesis of such production. Upon finding only a small amount of scientific articles in Brazilian databases (n = 6), we considered it necessary to compare such findings with international research to identify whether the theme is understudied only nationally or worldwide too. Hence, we included a second objective to this study, which was to compare research available in Brazilian databases and in international ones about the theme in order to situate the Brazilian production in the wider context and indicate possibilities of action, evidencing transformative elements identified in the literature. We also present the needs of scientific knowledge for the proposition, implementation, and evaluation of possible actions in the Brazilian educational contexts.

The demands arise from data showing the high amount of people, mainly women, who suffer because of gender-based and sexual violence around the world and in Brazil. In 2013, according to World Health Organization research on violence against women, 35% of women worldwide suffered sexual violence from partners or non-partners, and 38% of women's murders were committed by intimate partners (World Health Organization–W.H.O., 2013), configuring a problem of epidemic proportions.

In Brazil, in 2015, the map of violence highlighted the increase in the number of deaths of women in the country and indicated that Brazil ranks 5th in the world in femicide (Waiselfisz, 2015). This fact becomes more worrisome when we consider that since 2006 the country has a law that was acknowledged as a milestone in the fulfillment of international and constitutional guarantees on women's rights (Barsted and Pitanguy, 2011). Law 11,340/06 (Brasil, 2006), known as the Maria da Penha Law, makes explicit the criminalization of violence against women, creates mechanisms to prevent family violence and domestic violence against women, and guarantees the protection of women and their children to prevent and preclude violent situations. Even though over a decade has passed since this law's approval, the number of women killed because of gender violence remains staggering, and grows across the country (Waiselfisz, 2015).

Also in 2015, the Enóis - Inteligência Jovem Institute, in partnership with the institutes Vladimir Herzog and Patrícia Galvão, conducted a survey of more than 2,300 women aged 14 to 24 years in different Brazilian states. The research results show that 41% of the interviewees have already suffered physical aggression and, within those, 51% were assaulted by a relative, 38% by a partner, 23% by a colleague, 3% by a school teacher, or 3% by a boss or colleague, and 3% by unknowns (ÉNOIS Instituto, 2015). Focusing on youth, a research conducted by the Avon Institute in 2014, with more than 2,000 youths aged 16 to 24 years, revealed that 66% of women had experienced some type of violence or partner control, and that 55% of men had committed violence against their companions (AVON Instituto Data Popular, 2014).

Globally, researchers and international organizations have indicated that violence is reflected directly within the school setting and that girls form one of the groups that is most vulnerable to violence, along with the LGBT population, immigrants, and people with disabilities or those that differ from the local standard (Unicef, 2012; Duque and Teixido, 2016; UNESCO-United Nations Scientific Educational, 2017).

United Nations Children's Emergency Fund - (Unicef, 2012), highlights the importance of combating violence against children and adolescents and lists the forms of school violence that have been denounced: “bullying, sexual and GBV, physical and psychological violence, and violence that includes a dimension external to schools, such as gang culture-associated violence, weapons and fighting” (Unicef, 2012, p. 5). It also indicates that girls are at a higher risk of gender and sexual violence1, and boys are at higher risk of victimization by physical violence. As previously highlighted, boys also suffer GBV in school, especially those who are identified by others or self-identified as homosexual. The students identified as the most vulnerable to bullying are those of low-income or ethnic, linguistic, and cultural origins other than the “standard” in a region (UNESCO-United Nations Scientific Educational, 2017).

UNESCO-United Nations Scientific Educational (2017) highlights some important aspects of the issue, stressing on the fact that girls are the most affected among the victims:

Specific data on sexual violence in and around the school setting is limited, since many victims are hesitant to report acts of sexual violence for fear of being shamed or stigmatized or because they are concerned that they will not be believed or will face retaliation from their aggressor or aggressors. Nevertheless, available figures suggest that sexual violence and abuse in schools, perpetuated by staff and by other students, is a reality for many students, particularly girls (p. 9).

It is worth noting that in schools, the main form of violence that can be observed is bullying, which can be defined as a form of violence constantly repeated, with unequal power relations (Olweus, 2013). According to (Unicef, 2012):

The most common form of bullying is verbal, which, if left unchecked, can also lead to physical violence. The Study underlines that almost all bullying is sexual or gender-based in nature, aimed at putting pressure on children to conform to cultural values and social attitudes, especially those that define perceived masculine or feminine roles (p. 5).

Hence, it can be stated that school is a space where violence also takes place. But, it also is a space where education about violence and actions to prevent and overcome violence can be addressed and potentialized. Recent research has been dedicated directly to the education about GBV and the development of actions to overcome GBV.

School and the Prevention of Gender Violence and Overcoming Gender Violence

Considering these elements and research on school violence in Brazil, research on violence in schools has mapped its occurrence, as the literature review conducted by Nesello et al. (2014) states, “The existence of violence in the school was reported by 83.4% of the students and 87.3% of the teachers” (Nesello et al., 2014, p. 123). According to these authors, sexual violence has little space in research on violence. Abramovay et al. (2016) point out that more than 70% of the students consider that there has already been some form of schooling in the five most violent capitals of the country, of school violence, and 42% say they have already been beaten at school. The main forms of violence pointed out by them were as follows: “thefts and robberies (19%); other students (12%); threats (12%); cyberbullying (7%); and teachers (7%), while the other types of violence in the total number of schools would not reach 5% ”(Abramovay et al., 2016, p. 33).

The seriousness of the problem of violence in the school environment deserves to be highlighted; since, in addition to being constant, as indicated by research on bullying, for example, it has serious consequences such as decrease in academic indexes, dropping out of school, more interpersonal difficulties, depression, anxiety, and suicide (Unicef, 2012; Duque and Teixido, 2016; UNESCO-United Nations Scientific Educational, 2017). In addition, low reporting rates may indicate that, like in universities (Valls et al., 2009), schools fail to sustain means to encourage victims to report and even hinder both actions for victim support and development of preventive programs, since there is little knowledge of the extension of gender violence in educational institutions.

For these reasons, the incorporation of violence prevention in school actions is necessary, but also, because school is one of the main socialization environments for children and young people. As Gómez (2004) points out, the socialization of children and young people initially occurs in the family group, but it also includes the peer group, media, cultural groups, and school.

Research dedicated to understanding the phenomenon, and mainly to overcome it, points to the importance of violence prevention in the first years of school, focusing on the reduction of student aggressiveness, and the importance of community participation in the development of strategies to prevent and overcome violence at school (Tremblay et al., 2008; Oliver, 2014); strengthening of school management and peer group in the development of actions (Duque and Teixido, 2016); and, when it comes to universities, institutional actions in support of victims and receiving complaints (Oliver and Valls, 2004; Rosa et al., 2008).

Ríos (2009) points out that school is an important socialization agent for individuals. Therefore, it can also be an important place for preventing and overcoming violence, once it provides diverse relationships and interactions in which the teacher can act directly in appreciation and consolidation of less violent relations, lessening gender stereotypes. But for this, teachers need to be prepared to work for the prevention and eradication of gender violence, as highlighted by Aguilar et al. (2009); Botton et al. (2012); and Bujosa et al. (2012).

As Gómez (2004) indicates, the primary socializing agents for children are as follows: firstly, family then peer group, school, and media. Thus, the issue of overcoming and preventing GBV should not be restricted to school. The approach should consider the surrounding community as one of the main elements in prevention, mainly because of the importance it has in the socialization of young people. Thus, the articulation between school, families, and the surrounding community strengthens the power of actions for violence prevention in the process of socializing in children and youth.

Considering the fact that, worldwide, in gender violence, whether against women or against LGBT identities, actions are mostly carried out by men; the discussion about masculinities assumes an important place in understanding the phenomenon but also in preventing and overcoming it. The attraction for masculinity models also becomes key in this process.

The violent behavior of men relates to what Flecha et al. (2013) describe as a model of traditional dominant masculinity (TDM). The authors demonstrate that masculinity models are directly related to gender violence, and for the authors, the traditional dominant model contributes to the increase in gender violence.

The TDM model is characterized by unequal values, postures, and behaviors, specifically disdain and violence in relationships (Flecha et al., 2013). Studies such as those of Castro and Mara (2014) that address attraction and the relation with the traditional dominant model that presents violent characteristics and of A. Flecha et al. (2010), which relates the hegemonic model of masculinity to gender violence, emphasize the importance of rethinking masculinity in order to prevent gender violence. Padrós (2012) emphasizes that adolescents are attracted to the traditional dominant model and that is why it is necessary to rethink masculinity.

Gómez (2004) had already addressed the issue of sexual attraction highlighting violence and disdain as relevant factors in understanding people's motivations in their love choices:

To this we must add that socialization agents, with the media in leadership, are promoting a kind of relationship based on “instinctive” and “chemical” attraction looking at those who are “good” and “hard” facilitating contempt, indifference and ill-treatment (Gómez, 2004, page 1312).

His approach highlights the importance of reviewing the form of socialization carried out in school, seeking the transformation of affective-sexual relations. For this reason, Flecha et al. (2013) continued the discussion, addressing the traditional dominant model already presented: the traditional oppressed model and the new masculinities, the latter being a model that prevents gender violence. Traditional oppressed masculinity is the model in which men are socialized not to be aggressive, not sexist, and as people who take care of the house, but however, are not attractive and, for this, end up being oppressed by the traditional model of masculinity and do not succeed in affective-sexual relations.

On the other hand, in the model of new alternative masculinities, which seeks to unite passion and desire with the language of ethics, a man aims to be a person with values: not aggressive and not sexist. This model has three fundamental characteristics: self-confidence, strength, and courage that are necessary to oppose the traditional dominant model and the explicitness of the rejection of the double moral. Self-confidence helps men to assert themselves and to contribute to others by becoming more attractive. It is a fundamental point for there to be no hierarchy of masculinity. Strength and courage help new alternative masculinities to express and reject the traditional dominant model, reject violence as a way of acting, and reject the oppression of other models of masculinity. Finally, the alternative model must demonstrate consistency in his actions in advocating for the end of violence against women in groups or in public and also be attractive and egalitarian in his day to day life, not relating to women who treat him poorly or reject “For NAM men, fighting to end with violence against women involved in DTM and being strong in order to construct egalitarian relationships with egalitarian women” (Flecha et al., 2013, p. 105).

Thus, from the model of new alternative masculinities, it is possible to visualize models of masculinities that are egalitarian and that promote the fight to end violence against women. Vidu et al. (2017) emphasize the importance of the concept of “survivors first,” which refers to the importance of considering victims as being a priority in any process that is related to breaking the silence. In all situations, the victims have to be in the first place, and it is not possible to accept any kind of violence. Thus, the importance of the spectator's action in cases of violence, according to scientific evidence, is given as follows:

The powerful meaning of bystander intervention stresses the importance of empowering “bystanders.” According to scientific contributions that have shed light on the crucial role of the Friends of survivors (Banyard et al., 2010), one in three women in college and one in five men have friends who have been told that they were victims of an unwanted sexual experience during their college years. If they do not feel empowered, they will likely not support the victims they may know, which limits the potential for bystander intervention to occur (Vidu et al., 2017, p. 7).

The above-mentioned studies point to pathways in relation to violence prevention, which may guide teacher training as well as the actions of teachers throughout the educational system. But, have actions of this nature been produced in schools and disseminated in a significant national and international context? Have these actions been effective in preventing and overcoming GBV? Faced with these questions, in this article, we address the issue of gender violence against women, focusing on the Brazilian literature on preventive actions in school, and raise relevant indicators in international production that can serve as a contribution to the actions developed in Brazil. In this way, the aim of the present study is to provide scientific evidence that can base school actions for the prevention of GBV, specifically in the Brazilian context, based on the actions that are developed in the national and international contexts.

More specifically, we first seek to characterize the national scientific production about school educational actions for the prevention of GBV and then compare it with the international literature on the subject, in order to locate Brazilian production, indicate possibilities for action, and to point out demands for the scientific knowledge production on proposing, implementing, and evaluating possible actions in schools in the Brazilian contexts.

Method

The research presented here involved a literature review at national (Brazil) and international levels, without a delimitation of the publication date. The searches were conducted between October 2017 and December 2017. The Flow Diagram for the search conducted on the databases and selection of papers is available in the Supplementary Material.

At the national level, the searches were conducted on the Brazilian online libraries BVS-Psi, Scielo, Bank of Thesis and Dissertations of CAPES3, and Brazilian Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations, which are the main and most recognized scientific databases in the country. The terms used for the search were the Portuguese expressions for “‘gender violence’ AND ‘school”’ and “‘violence against women’ AND school.” In this search, 431 entries were obtained.

At the international level, the search was conducted both in Web of Science and Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) websites for the terms “‘gender-based violence’ AND school AND intervention,” “‘violence against women’ AND school AND intervention,” “‘gender-based violence’ AND school AND prevention,” “‘violence against women’ AND school AND prevention,” “‘gender-based violence’ AND school AND program,” and “‘violence against women’ AND school AND program.” Since some articles known by the researchers were not retrieved, a new search was conducted on Web of Science using the terms “‘gender violence’ AND school AND prevention,” “‘gender violence’ AND school AND intervention,” “‘gendered violence’ AND school AND intervention,” and “‘gendered violence’ AND school AND prevention.” Language constraint was not applied, but all articles obtained presented an English language abstract. A total of 222 articles were retrieved. These sources were chosen because of their recognition in the international scientific community.

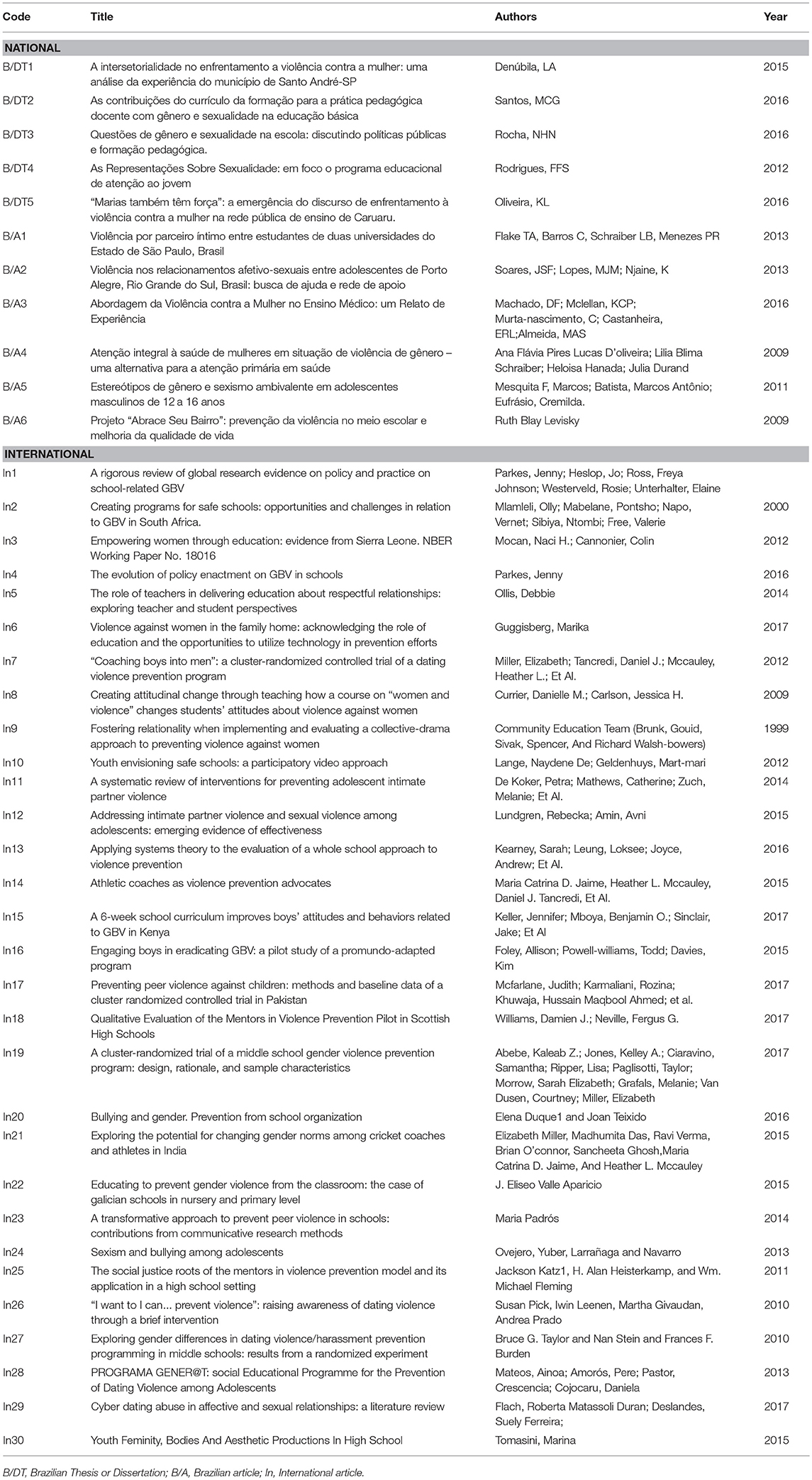

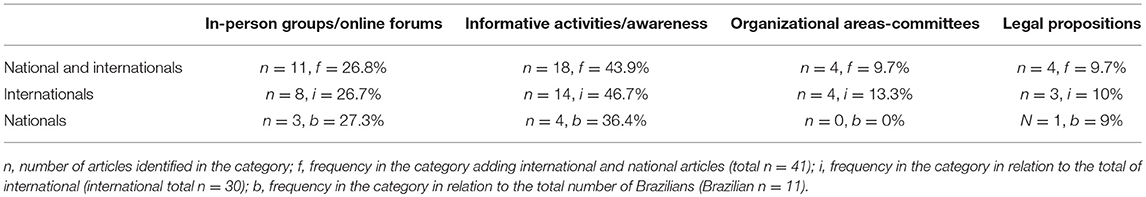

From the total number of texts obtained, only the papers that mentioned, in the title, abstract, or keywords, some type of action developed in schools aimed at the prevention of gender violence were selected. For the international articles, only those published in scientific journals were selected, while manuals, reports, and newsletters were excluded. The Brazilian dataset also included papers that failed to directly address actions in school, but which mentioned the relationship between school and GBV. From these procedures, we reached a total of 5 theses and dissertations and 6 articles in the national scope and 30 articles in the international scope, totaling 41 works comprising the period between 1999 and 2017. The papers were coded and can be checked in Table 1 where the code used for each paper and the complete references are given. Texts from the international dataset are indicated with the prefix code In-, the Brazilian thesis and dissertations are indicated by the prefix B/DT, while the Brazilian articles are indicated by the prefix B/A.

The difference between the searches conducted in the Brazilian and the international databases was due to the number of papers obtained in each. The Brazilian search retrieved a total of 11 studies (including journal papers and thesis and dissertations), while the international search retrieved a total of 30 papers. For this reason, we opted to include the dissertations and theses from the Brazilian production. The difference in the quantities will not be explored in the present paper, for it was not the scope of the study. It is important to state, though, that such a difference in search procedures could have an impact on the analysis.

As the number of papers found was not expressive and were greatly diverse (regarding participants, methods, interventions, impact assessment, etc), we opted to perform a descriptive analysis of the data. The only statistical procedure was the calculation of the distribution of some of the characteristics through simple percentage.

We opted to include secondary research (reviews), studies that failed to implement, in fact, an intervention and those that failed to perform an assessment of the direct impacts of interventions. The choice to maintain such papers was because of the recognition of a lack of research that aims to perform such measurements as well as of the difficulty in defining what effects should be assessed or how to propose a standardization for intervention research on the recent theme. The manner in which we conducted the present research provides parameters for the proposition of possible successful interventions. It must be highlighted that there is indeed little research on practices regarding the prevention of gender violence in schools, and because of this, the identification of good or best practices and especially successful is difficult. In other words, the characteristics of the data obtained prevented the adoption of protocols for conducting systematic reviews such as those described in the Campbell Collaboration and others.

According to Mertens (2015) and Creswell's (2012) proposition on conducting literature reviews, the categories emerged from the reading of the texts, instead of pre-defined categories. For the analysis of the texts, a grid of analysis was constructed in which the following were identified: the type of research carried out (bibliographic, action-research, experimental, etc.); the objective of the paper; the characteristics of the actions described in the paper; the target population of these actions; the types of research methods used; the obtained results; and the indicated aspects that contribute to the overcoming of GBV (transformative dimension) and aspects identified as barriers to this overcoming (exclusionary dimension), as described in Gómez et al. (2006) and Gómez et al. (2013) when describing the Critical Communicative Methodology.

Initial criteria were proposed for the categorization of different elements in the papers. In order to increase agreement between researchers in data collection and analysis procedures, an initial analysis was performed with a sample of the data divided among three of the researchers. Based on the agreement between them in the pre-analysis, the initial criteria were reevaluated and additional criteria were proposed. In cases where any one of the researchers was in doubt with the categorization of the papers, the other researchers were consulted and the analytical consensus was reached.

In order for a certain aspect mentioned in the paper to be considered transformative, it was necessary for it to present evidence in the data of this contribution, either by the explicit reduction of violence or by the promotion of contributing elements and theoretical basis. Exclusionary aspects were those that had a relationship mentioned in the literature with the increase or continuity of gender violence. After identifying such elements (exclusionary and transformative), they were grouped according to similarities: texts that indicated the same transformative elements were grouped together, and the same was done for the exclusionary elements.

Results

Having the texts analyzed according to the categories that emerged from their contents, we were able to compare the Brazilian and international productions and to describe the transformative and exclusionary elements for the topic. The elements that emerged from the analysis of the publications were as follows: study objective; the characteristics of the actions described in the paper; target population; type of research; and results of the interventions.

About the Objectives of the Papers

The objectives of the various papers were grouped into four categories, described below. This grouping was proposed from the identification of coincident elements in the objectives described, although there were differences in their writing. Some of the papers presented more than one objective, so they were classified in more than one category (namely, In2, In6, In9, In20, In28, In29).

(a) To evaluate the results of actions/programs/projects: 19 papers (In2, In3, In7, In7, In9, In9, In13, In14, In15, In16, In17, In18, In23, In25, B/DT2, B/DT5, B/A2) are related to the evaluation of existing programs, that is, verifying their impacts and success in overcoming GBV or in elements related to this overcoming. Such evaluation was the objective most frequently cited in the papers (n = 19, 46.3%). It is important to emphasize that these evaluations were of different natures, such as reports of how the participants felt (In30), agreement with myths about rape (In29), perception of reduction in the number of occurrences of gender violence (In54), or ability to identify actions such as gender violence (In54).

(b) To evaluate the prevalence of GBV or an indicative (bias) of the problem: 10 studies (In6, In10, In19, In21, In22, In24, In28, In29, In30, B/A1, B/DT4, B/DT5) verified the situation of gender violence in certain places, the call signs of the situations, and the macho beliefs of a particular population but failed to highlight proposals for solving the problem. This goal was the second most frequently cited (n = 12, or 29.3%).

(c) To describe actions/programs/projects to overcome GBV: works that were dedicated to describe programs, projects to overcome violence, or only some actions (In2, In6, In9, In12, In20, In28, In29, B/A3, B/A4, B/A6). This category of objectives was present in a total of 11 (n = 11) papers, and it is the third most frequent category.

(d) Analyze the available knowledge (literature reviews…): six papers (In1, In4, In11, In20, B/A3, and B/DT3) aimed at reviewing the literature, either on the analysis of prevention programs or on the knowledge produced on this matter, totaling 14.6% of the papers analyzed.

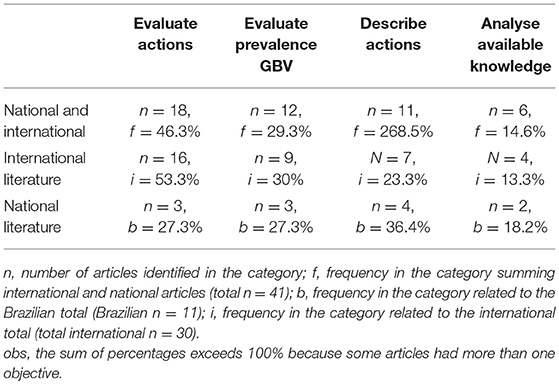

These categories allowed to verify the Brazilian and international contributions in relation to the preventive studies of gender violence. The distribution of the articles in relation to the objectives is shown in Table 2 below.

Considering the data presented, it is possible to state that the objectives of the papers mainly focused on evaluating the results of GBV prevention actions and programs. The next most frequent objectives were the assessment of GBV prevalence and the description of programs and actions. If we separate the analysis between national and international literatures, it can be observed that over half of the papers in the international literature aimed at evaluating the effects of GBV prevention actions.

In the Brazilian literature, a more even distribution in the categories was observed, with a slight majority of the studies aiming at describing the prevention actions. This indicates a significant difference in the comparison between the national and international literatures in favor of the second one.

About the Characteristics of the Actions

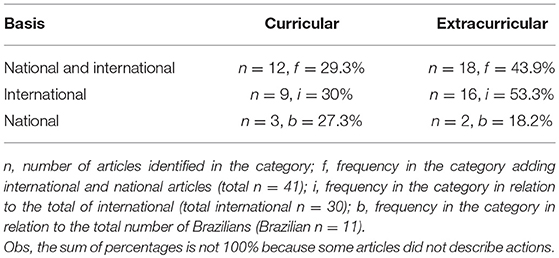

In the category “Description of actions,” the characteristics of the activities described in the papers can be grouped, that is to say, to the scope in which they were implemented (curricular or extracurricular) or to the format of the activities (In-person groups/online discussion forums; Training and information activities/Awareness; organizational areas —committees—legal propositions/public policies, such as laws or institutional structuring and policies). It is important to emphasize that the sum of the articles in the categories exceeds the total of articles and the relative percentages exceed 100%, because some articles described the accomplishment of actions in different formats. Also, some of the articles indicated that no intervention actions had been carried out because they were exploratory, preparatory to future program implementation or to review the literature.

Scope

This category is related to the school activities that are present in the school curriculum and the activities that are carried out in the school, but which occur at other times and are not directly linked to the curriculum. Twelve (n = 12) articles were used to analyze curricular activities (In8, In11, In13, In15, In19, In20, In23, In27, In28, B/DT2, B/DT5 and B/A3), and seventeen (n = 17) articles were dedicated to the analysis of extracurricular activities (In2, In5, In7, In9, In10, In11, In13, In12, In14, In16, In17, In18, In20, DT5), as can be seen in Table 3.

As it can be observed, considering all the studies, the activities were mainly developed in an extracurricular context. When separating Brazilian and international productions, it is possible to observe that in the international scope, most of the works dealt with extracurricular actions (n = 17, or 56.6% of international ones) in comparison with curricular actions (n = 7, or 23.3%). It can be emphasized that only five studies (In1, In21, In22, In24, and In30) failed to address preventive actions or 16% of international productions.

At the national level, curricular actions (n = 3, or 27.3%) were more frequent than those conducted in an extracurricular context (n = 2, or 18.2%). However, it is important to emphasize that, considering that these are the possibilities of action in school, they refer, together, to only 45% of the works at the national level, which means that most of the works carried out actions in other spheres (B/DT1 and B/A4) and public policies (B/DT3) or fail to describe actions (B/DT4, B/A1, B/A2, B/A5, or 36% of national literature).

Activity Format

This item referred to the characteristics of actions taken to prevent GBV and whether they were more participatory, such as group discussions, or a more informative character in order to disseminate knowledge (such as campaigns on specific dates, lectures, pamphlets, etc), as shown in Table 4.

In-person Groups/Online discussion forums: refers to the format used to carry out prevention or research activities on the topic. Papers in which actions aimed at discussing the GBV situation and its prevention through discussion groups or face-to-face forums, as well as those carried out online, fall into this subcategory (In6, In7, In10, In11, In12, In18, In19, In28, B/DT3, B/DT5, and B/A6). There were 11 articles or 26.8% of the total articles.

Informative activities: this subcategory refers to the papers that presented informative and awareness raising actions about GBV; that is, the format failed to have an action developed in the GBV practice but only had the education of people as the identification of types of violence or elements of gender inequality, in activities such as lectures or theatrical performances. The actions were described in 18 papers (In2, In5, In7, In8, In9, In11, In18, In19, In20, In25, In26, In27, In28, In29, B/DT1, B/DT5, B/A4, B/A6) or 43.9% of the total.

Organizational levels

This subcategory refers to actions related to the organization of committees or commissions in school that coordinate GBV prevention actions. These actions were present in four articles (In4, In20, In23, and In29), totaling 9.7% of the studies analyzed.

Legal propositions

Legal propositions refer to works that describe the implementation of laws and public policies, analyzing their effects or describing them. In this work, we identified four actions (In2, In3, In4, B/DT1).

Considering the data presented above, most of the papers (18 articles, or 43% of the works) present actions that focus on awareness and informative activities and more often in the extracurricular context (n = 18, or 43% of articles). With regard to the national work, the data point out that there are also a greater number of works in the subcategory of awareness and formative and informative activities (n = 4).

Target Population

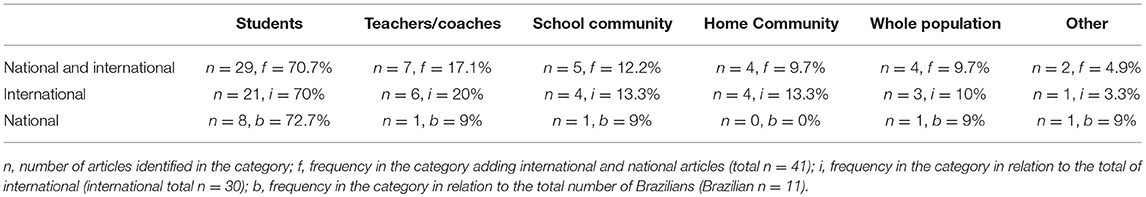

Initially, this item was analyzed aiming to identify the target population of the actions developed within the projects of prevention of gender violence. It should be noted, however, that some of the articles analyzed failed to present intervention actions. In these cases, the research participants were considered as the target population. In this way, we identified seven population groups, described below, and sometimes the same work was focused on more than one population. The frequency of populations in the papers are described in Table 5.

Students were the most frequent target population of the actions described in the papers, present in 29 of them (In1, In5, In7, In8, In9, In10, In11, In12, In13, In15, In16, In17, In18, In18, In19, In21, B/A2, B/A3, B/A5, B/DT2, B/ DT3, B/DT 4, B/DT5) or 70% of studies. The educational levels to which they belonged ranged from kindergarten (e.g., In22) to university level (e.g., In8). There was also wide variation regarding nationality, ethnic origin, and educational context (e.g., Pakistan In17, Scotland In18, South Africa In2, Liberia In4, Brazil (B/DT,B/A), USA In7, India In21, Sierra Leon In3). There were also papers focusing on both male and female students (e.g., In 12). They also worked on issues of self-protection for girls (e.g., In3, and In12), as well as interventions for active viewers (e.g., In27) and construction of nonviolent models (e.g., In27).

Among the students, there were studies focusing on the general population of students in a given school (e.g., In20), as well as some with specific populations, such as athletes (e.g., In21) and theater groups (e.g., In9 and B/DT5).

Among works aiming at actions with students, eight were Brazilian productions (B/A1, B/A2, B/A3, B/A5, B/DT2, B/DT3, B/DT4, B/DT5) that accounted for 72% of the Brazilian studies. Similarly, studies with this population totaled 70% (n = 21) of international studies.

Teachers/Coaches

Some of the actions or surveys focused on the teacher or the coach. These two groups were categorized together by representing people who are not peers of the students and represent some role of authority and teach the youth with whom they work. This was the second most frequent population in the works with a total of seven works (In, In5, In6, In14, In19, In21, and B/DT2) or 17% of the works. Only one Brazilian study approached this population (B/DT2).

School community

This category refers to studies that present actions aimed at the school community as a whole, not just specific actions with students or teachers. They involve practices and research that included actions with teachers, students, managers, employees, relatives, volunteers, etc. Studies of this category totaled 12% (n = 5) of the papers analyzed, four in the international scope (In1, In13, In21, and In23) and one in the national scope (B/A6).

The entire population

These studies included those that refer to intersectoral government laws and programs aimed at benefiting the entire population of a territory (country, state, or municipality). Four (n = 4) studies presented this approach, three international (In2, In3, and In4) and one national (B/DT1).

Families or communities: refer to studies that focus on the action of the students or the community (neighborhood, community centers, etc.) in which the students live. Four studies fell into this category, all at the international level (In1, In12, In13, and In17). It is important to note, however, that a review study (In4), when analyzing several actions developed in three different countries, indicates the existence of community programs developed in Brazil, aiming at the prevention of violence in general but also includes elements of prevention of gender violence.

Others

Three studies were identified in this category. One of them addressed the role of the public health care system staff in Brazil (B/A4), another one interviewed school managers (In22), and the third study failed to clearly indicate the study's target population (In29).

It is important to emphasize that several studies have worked with more than one target population, including teacher-student (In5, In19, In21, and B/DT2), family/community-student (In12 and In17), and the entire community-family-students (In 13).

Type of Research

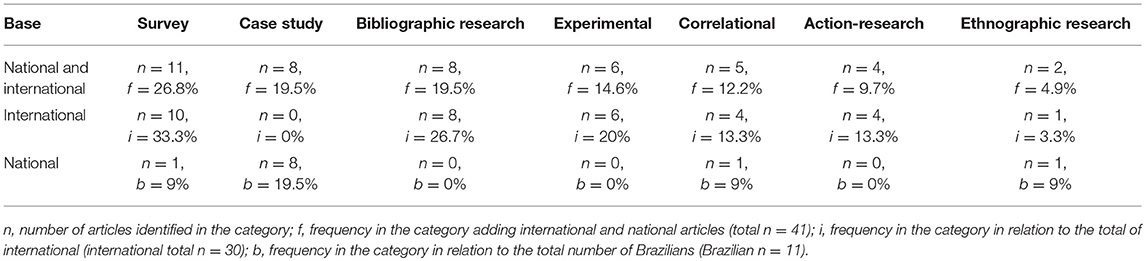

This section seeks to describe the research designs used in the articles, based on the descriptions by Mertens (2015) and Creswell (2012). It is important to emphasize that this categorization is made from the analysis of some elements described in the methods or procedures mentioned in the studies, and it is possible that other names could be assigned to the described procedures. It is also emphasized that some studies that were analyzed may present another terminology for the research designs and that some of the works failed to present discriminated Method sections, which were then inferred from their introduction or results. The use of seven different designs was identified: bibliographic research, correlational research, action research, survey, case study, experimental research, and ethnographic research. The number of articles using each method and the proposal to which they relate are described in Table 6 below.

Surveys were the most frequent design used in 11 studies (In13, In14, In15, In16, In 18, In 19, In 21, In 22, In 28, B/A1, and B/A1), totaling 26% of the papers. This type of design is commonly used for the purpose of describing some characteristic of a particular sample or population, such as attitudes toward a theme, behaviors, opinions, etc. (Creswell, 2012). This type of research has a descriptive function and fails to seek to establish causal or correlational relationships.

The second most frequent type of research was the case study (n = 8, 19%), but it was only identified in the Brazilian studies (B/A3, B/A4, B/A6, B/DT1, B/DT2, B/DT3, B/DT4, and B/DT5) and not in international studies. This type of research is not characterized by the techniques and tools used but by the object of study, referring to a case, a particular instance of events, or phenomena (Mertens, 2015) and aims to “gather comprehensive, systematic and in-depth on each case of interest” (Patton, 2002, p. 447). As Fonseca (2009) indicates, the case must represent more than itself, providing information about a phenomenon. As Creswell (2012) suggests, the knowledge gained through case studies should not be viewed as universal or readily generalizable, given the particularities of its context.

Eight articles (In1, In2, In4, In8, In11, In12, In20, and In29) (19%) were identified as bibliographic searches. It can be defined by the data source and not necessarily by a method. They are studies that obtain the information through sets of bibliographical productions (documents, laws, scientific articles, books, etc). They may have different objectives, among them, revisions of scientific literature aim to identify the scientific knowledge available on a given topic. The present research, for example, characterizes this design. This type of research was absent in the national production, that is, all the studies that used this design were obtained in the international bases.

It was possible to observe that 14.3% of the studies (n = 6) used experimental designs (In7, In8, In13, In17, In26, and In27), which included single subject surveys, single-group, quasi-experimental models, etc. Correlational studies were classified in their own category, because they did not have manipulation of variables by the researchers. It is also possible to emphasize that this design was only identified in the international literature.

Correlational studies are defined by using statistical models that evaluate how statistically the variation in one characteristic of the phenomenon is associated with variation in another characteristic. There is no manipulation of variables but there are observed variations in them; therefore, it is not possible to establish causal relation between them. This design was identified in five studies (11.9%), four at the international level (In6, In24, In25, In3) and one at the national level (B/A5).

The action-research design was used in four surveys (n = 4, 9.7%), all international (In5, In9, In10, In23), characterized by performing a survey on specific practical issues, aiming at its change and improvement. In this type of research, there is a direct participation of the researcher, and it aims at the improvement of some practices.

The use of ethnographic research (In30 and B/DT5), characterized by a holistic approach to portray the daily experiences experienced by the subjects, was also identified, seeking to reveal how the person structures and describes their world (Mertens, 2015). In this way, it is strongly related to the subjects' routine, accompanying them in their natural environment.

As can be seen, there is a significant difference in the methods implemented in the research when comparing Brazilian and international literatures. In the latter, there was a greater variation in the types of research developed, while in the national production there was a clear predominance of the case studies.

Results of Interventions

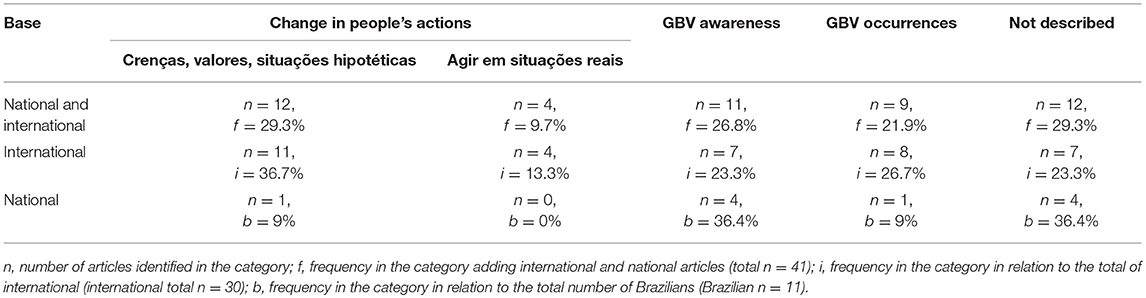

From the descriptions of the actions in the studies, it was sought to identify if they indicated the results obtained with their implementation. The types of results described were then categorized into four main categories: change in people's actions; awareness of people; change in some type of record of occurrences of gender violence; and if there was no description of results, although there was some intervention described. It is important to emphasize that some of the studies failed to describe GBV prevention actions (B/A1, B/A2, B/A5, In13, In19, In21, In24, In28, In29, and In30). The results obtained are described in Table 7 below.

Most of the studies (n = 14, or 34%) described the results regarding some change in participants' actions. This category has been divided into two subcategories. In the first one, with a total of 12 searches (B/DT2, In1, In3, In4, In7, In8, In10, In10, In12, In14, In16, In25, and In26), the changes refer to beliefs, hypothetical situations, and values or answers to questions about how they assess GBV situations, how they would act if they witnessed violence, etc. Of these, only one was identified in the Brazilian literature (B/DT2). In the second one, with six works (B/A4, In1, In7, In12, In14, and In18), they refer to concrete actions of the participants (they report reducing commitment, reporting situations in which they witnessed and intervened, etc.).

The second most frequent type of result was the participants' awareness of GBV, which included being able to define or identify certain actions as GBV, to recognize the existence of GBV. It was observed in a total of eleven studies (B/A3, B/DT1, B/DT3, B/DT5, In1, In5, In9, In10, In18, In23, and In26). It should be noted that most of the Brazilian studies (n = 4, or 36% of them) present results in this category. If studies that fail to describe actions (n = 3) were excluded, and therefore there would be no results to be discussed, the total Brazilian production of awareness would be 57%.

The third most frequent category was the change in the occurrence of gender violence, which included reports of people or records of GBV situations and reports of victimization. It was observed in eight (n = 9, or 22%) studies (B/A6, In1, In4, In11, In15, In17, In20, In23, In27), of which only one was national (B/A6). Considering that the present study sought to identify preventive practices of gender violence, results in the occurrence of GBV are of great relevance for the evaluation of the described practices. Similarly, one study describes that no changes were observed (B/DT4), which is also important to be analyzed.

Studies that failed to describe the results obtained with actions totaled two studies (In2 and In6). It should be emphasized that they failed to describe the results obtained, although preventive actions are described.

In line with what was previously stated in the Method section, the results that were presented reflect some of the methodological limitations in the review. The difficulty in comparing the texts, considering the diversity between papers, can be pointed out as one of the present study's limitations. The papers show a great diversity in methods and actions, and, because of that, we opted to establish descriptive categories in order to propose a primary analysis of the theme.

Discussion

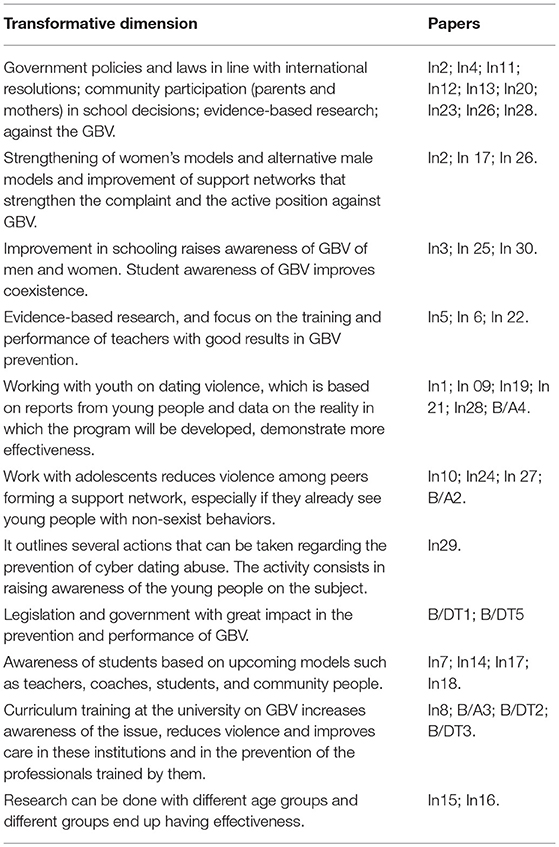

From the analysis of the data, it is proposed to discuss the results obtained in two axes. In the first one, we sought to identify transforming elements in the analyzed research, that is, elements identified in the surveys that contribute to overcoming gender violence, to proposing preventive actions of gender violence, and to producing knowledge that favors them and exclusionary elements identified in them, that is, those pointed out in research as related to the maintenance and aggravation of gender violence or its consequences. In the second axis, we aim to discuss the differences and similarities identified between national and international productions, seeking to identify how to advance in the production of knowledge and conduct of preventive practices. These elements were obtained from the papers through questioning: what elements do the papers present to contribute to the prevention or maintenance of gender violence?

Considering the previous question, the analysis of the texts was conducted and the transformative and exclusionary elements were identified; after that, the themes identified were grouped in the following tables.

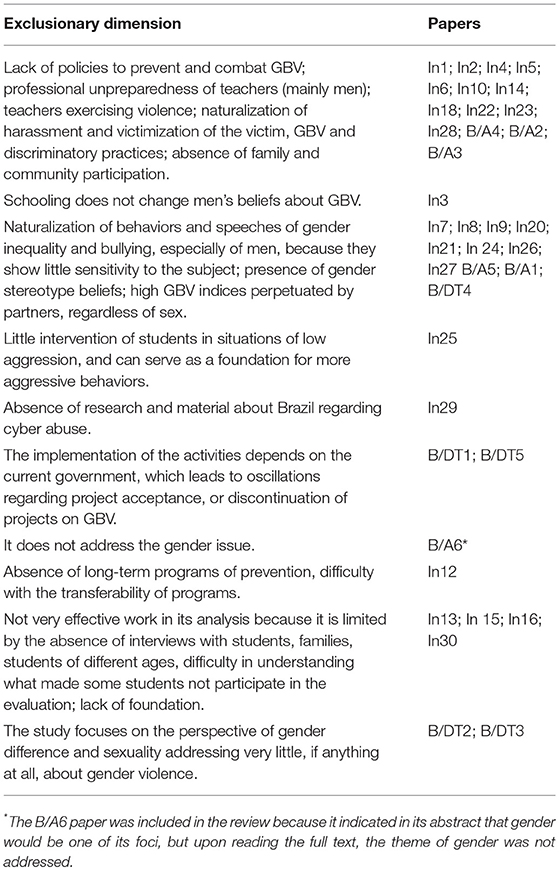

Exclusion and Transformation

Table 8 presents a summary of the exclusionary dimensions indicated by the articles and in which we seek to identify convergences between the elements pointed out in several studies.

The results pointed out transforming elements present in different analyzed researches. Table 9 summarizes the transforming elements and the researches in which it was possible to identify them.

The results indicate several factors in the analyzed studies that contribute to the overcoming of gender violence in the case of transforming elements and to understand the elements that impede the transformation, i.e. the excluding elements. In the analysis, the great majority of the elements are present in both the Tables 8, 9. Thus, we chose to carry out the discussion of both the elements together.

The papers presented relevant transformative or excluding elements related to government policies to prevent and combat GBV, teacher training, naturalization of or critique to practices of harassment, and family participation in schools.

Among these highlighted elements, some are crucial to working toward the prevention of GBV. The professionals who work in school must be well prepared for recognizing and acting in the prevention and combat of GBV. Current literature indicates that the risk of gender violence victimization is highly related to past experiences, mainly to have suffered violence in the first affective and sexual relationships (Gómez, 2004; Flecha, 2012); for this reason, teachers' performance may be fundamental for the prevention of violence given the proximity to children and teenagers starting their first affective experiences.

The same formative aspect of education can be regarded when focusing on the young population, who, especially in adolescence, are strongly influenced by their peers and role models. In this sense, international literature analyzed in the present study indicated the success of actions that focus on the education of individuals who can become role models and influence the behavior of others to act in a non-violent and more egalitarian way (Katz et al., 2011. Thus, working with athletes, coaches, and tutors with more egalitarian actions makes a great contribution to overcoming gender violence. These studies point to models and interactions that reach out to the students and go in the same direction as signaled by Flecha et al. (2013) about the need to overcome the division between the language of ethics and the language of desire when proposing actions for preventing and overcoming gender violence.

Thus, from the model of new alternative masculinities, as highlighted earlier, it is possible to visualize models of masculinities that are egalitarian and that contribute to the fight against GBV. In that sense, it is possible to envisage models that are not violent and that can be valued in school interactions, between male or female, teachers, coaches, employees, students, etc., valuing egalitarian models. These actions were pointed out as transformative in the texts analyzed, that is, proposals that are being implemented and analyzed in the international studies.

In relation to the Brazilian production, the papers only address informative aspects when discussing the curricular training on gender, as is the case in studies B/DT2, B/DT3, and B/A3; however, these discussions only address the aspects related to sexuality and not gender violence, failing to present results in terms of behavior changes. These three papers were characterized as case studies; although one of them was focused on evaluating actions and results, the other two were aimed at evaluating available knowledge and describing some prevention action. Since these papers focused mainly on sexuality, such an element was considered as one of the exclusionary aspects, which bar the transformation, mainly for neither addressing gender violence nor discussing its prevention.

In relation to the valorization of egalitarian models of femininity and masculinity, it was highlighted in the studies, being considered a transformative dimension; several authors and research point to something that contributes to overcoming gender violence (Ríos, 2009; Katz et al., 2011; Flecha et al., 2013; Castro and Mara, 2014), especially in the research related to coaches' performance that highlights a change in the naturalization of violent attitudes of boys toward girls, leading them to more respectful interactions (Jaime et al., 2015).

Another key element in the debate on preventing and overcoming gender violence is the construction of a support network and a culture of non-tolerance toward GBV. In this sense, actions aimed at training various actors to act against violence have obtained positive results in this overcoming, as is the case in articles In2 and In4. In this regard, one of the Brazilian papers discusses the topic B/A2 and points out the importance of network formation for GBV prevention, in addition to emphasizing that this helps transform youth' relations.

It is important to highlight the positive results obtained in studies that implemented actions for training active intervention of spectators in GBV situations, manifesting themselves in opposition to violence and in favor of the victim, even in situations of low violence. The action must be in all cases and even those of low violence, since they can generate more situations with increasing levels of violence against the victim thus perpetuating violence as previously highlighted in relation to the importance of bystander (Vidu et al., 2017). In relation to this specific topic, there is no data in the national texts, only the work B/A2 reports something in this sense when talking about networks.

With regard to legislation, the national papers address the theme in papers B/DT1 and B/DT5, highlighting the importance of the existing laws, law 11340/2006—Maria da Penha and law 13.104/2015—femicide, and of the importance of the State to manage policies of action against gender violence. However, they also indicate the discontinuity of the work that occurs when another party takes over the executive position, directly influencing the way the laws are implemented.

In this way, the elements presented in Tables 8, 9 provide scientific evidence that can base school actions for the prevention of gender violence, specifically in the Brazilian context, based on the actions that are developed in the national and international contexts, because they are the result of research that presented, with its preventive work, positive results in relation to prevention work.

International and National Scientific Production

In this section, the data obtained from the analysis of the Brazilian and the international datasets are compared and discussed in order to identify gaps and perspectives for future research.

With regard to the objectives of the studies analyzed, it is possible to notice that, when dealing with preventive actions of gender violence, with a specific focus on school, the international scientific production has prioritized the evaluation of the effects of the proposed actions. Contrastingly, in Brazil, there are still few publications in the national scope in which the objective is the evaluation of preventive actions in the school context. In this sense, most of the production is focused on the description of the prevalence of GBV or on the description of actions without, however, aiming to evaluate its results. As pointed out in INCLUDED (2012), a study that aimed at identifying actions for inclusion and social cohesion, the educational space is of great relevance for overcoming inequalities. Thus, it indicates the need to produce scientific knowledge about school actions that prevent and reduce violence specifically in the Brazilian context.

If we link the analysis of the objectives with that of the results described in the articles (including both Brazilian and international ones), it can be seen that most of them refer to changes in people's actions regarding gender violence. This data is consistent with the objectives proposed in the articles, since the analysis of the results of preventive actions is expected to lead to an observation of changes in the actions of the population.

In the Brazilian context, however, the results of the described actions referred more often to the “awareness” about the matter and not necessarily to a change in the actions of the individuals. Although awareness about the origins and characterization of gender violence may be necessary for its overcoming, it is important that, when evaluating intervention actions, its effects in terms of the actions of those who participate in it are observed. The predominance of “awareness” as the observed result of interventions instead of a change in people's actions is consistent with the greater frequency of reported objectives being “to describe actions and prevalence of violence” than to evaluate actions.

Also, with regard to the data related to the results of the actions (including Brazilian and international productions), we emphasize that most of them counted on the evaluation of beliefs, conceptions about GBV, or hypothetical situations. With regard to the data on change in concrete actions (not to harass, to intervene in real situations of GBV), it was less frequent. Another difficulty to be overcome is expressed by the fact that there are few studies in which the results were evaluated in terms of change in the incidence of GBV, which should be seen as the ultimate and primary objective of GBV prevention actions.

Another significant difference between national and international productions was the methods used. Surveys at the international level drew on diverse designs, including surveys, experiments, and correlational research, seeking to identify relationships between preventive practices and their effects. In the Brazilian production, there was a strong predominance of the case study design. This type of research allows in-depth and detailed knowledge of cases that may represent a phenomenon, provide indicative information for future research, or represent some exceptions. On the other hand, case studies are insufficient to provide broad generalizations of their results (Creswell, 2012; Mertens, 2015). In this sense, the need to conduct larger studies in the national context with objective evaluations regarding the results of preventive actions as well as the use of methods that more objectively evaluate changes and the relationships with the implemented actions may be indicated.

The analysis of the articles allowed to identify that the population for whom preventive actions are most frequently developed are students at different educational levels. In addition, conducting activities with other people involved in the prevention of gender violence was also identified, and in many cases, even when implementing actions with students, actions were also included with other actors, such as family members, teachers/coaches, and the school community.

With regard to the actions implemented, it is important to highlight how a small part of the Brazilian production described actions implemented in the school context (only present in 45% of the studies). This proportion is justified by the fact that studies that involved other areas, but that mentioned the school context in any way, were included in the analysis. This inclusion was due to the fact that, when searching exclusively for papers with preventive actions of gender violence in the school environment, few studies were found. Nevertheless, there was a significant number of papers that failed to describe intervention actions (36% of the Brazilian works). Those papers that implemented any action were mostly of an informative nature, being in agreement with the previously described analysis on the greater frequency of objectives related to the description of actions and evaluation of the prevalence (and not evaluation of the effects) and more frequent results related to the awareness about the violence than of change of people's actions.

Limitations

In this initial study, based on the analysis of the Brazilian and international productions on the theme of gender violence prevention in schools, the small amount of national papers in journals (n = 6) led us to incorporate the analysis of theses and dissertations (n = 5) to the study, which was not made with international theses and dissertations. This non-inclusion was due to the great volume of the international production (n = 222) that would demand a longer dedication of the research team, which will be conducted in the future. The impact of such differentiation was a restriction to some comparison aspects between was is being produced around the world and in Brazil. With regard to preventive actions in school, per se, no Brazilian papers were found.

Another limitation to the research occurred because of the absence or low occurrence, of impact assessment of the interventions implemented in schools. Even international studies that do conduct interventions in the school context rarely evaluate the impact on violence perpetration or victimization, even less on a follow-up stage. Therefore, even though transformative elements could be identified in many papers, it is difficult to evaluate if they do translate into practice.

Conclusions

GBV continues to be a problem of epidemic proportions, victimizing thousands of people every day around the world. It presents itself with several faces and can be of a psychological, material, sexual, or physical nature and is present in affective relationships, friendships, work, in the street, and at school. Overcoming GBV is a pressing issue, and the present study has sought to contribute in the extent that it aimed to provide scientific evidence that can base school actions for the prevention of GBV, specifically in the Brazilian context, from the actions that are described in the scientific literature both from the national and international contexts.

For achieving the proposed goals, bibliographical research was conducted in national and international scientific databases searching for papers that addressed actions of prevention of GBV conducted in the school context. Analysis of several elements of the articles was conducted in order to identify those that contribute to overcoming gender violence and those that maintain it. In addition, national and international literatures were also analyzed in order to identify differences and suggestions of continuities and improvements of the national scientific production.

The results indicate that, besides the fact that such production is scarce, Brazilian production is closely linked to actions to raise awareness about or to analyze of the prevalence of gender violence; few actions have been described in the national scientific production. Moreover, few of these articles seek to evaluate the impacts of these actions in terms of changing the behaviors of the population with whom they work. Finally, most of the Brazilian studies were carried out through case studies, which allow a thorough knowledge of the reality studied and the relationships established by the people in the analyzed context but hamper generalizations of their data and more comprehensive knowledge of the impacts of preventive actions of gender violence. Thus, it indicates the need to produce national knowledge that allows a more comprehensive and varied knowledge about the preventive actions of gender violence. In addition, data on the effects of these actions are analyzed, mainly in terms of changes in concrete actions of the target population and of occurrences of GBV in school and beyond.

In another sense, the international scientific production has sought to analyze the impacts of the various school actions described, mainly in terms of changes in beliefs and values expressed by the target population of the actions. It has also sought to identify, although in a smaller volume, changes in concrete behaviors of this population. To this end, a variety of methods have been implemented including experiments, action research, and ethnography. It is worth mentioning, as a recommendation for future productions, to analyze, in addition to the changes in the behavior of the target population of the actions, changes in the occurrence of gender violence.

Some of the elements identified as relevant to overcoming gender violence are as follows: the creation and implementation of specific laws, the preparation of teachers and professionals for the subject, the creation of support networks among students, the strengthening of egalitarian models of relationship, the strengthening of people as active spectators, the implementation of evidence-based scientific actions, interaction with different groups (students, teachers, families) in an integrated way, acting at various school levels, inserting training on gender violence in the university curricula, actions directed directly at the male population, investing in preventive actions and not just remediation, and implementing longer-term studies.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception of the study. BP, DB, and EG contributed to the design of the study, conducted data collection, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and wrote sections of the manuscript. DB organized the database. BP and EG conducted data analysis. BP, EG, DB, and RdM contributed to the discussion of the data. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer MP and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2018.00089/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Brazilian Law 11340/2006, that regulates denouncement and punishment of violence against women defines sexual violence as “any conduct that forces a woman to witness, maintain or participate in unwanted sexual relation by the use intimidation, threat, coercion or use of strength; that lures a woman into commercializing ou utilizing in any manner, her sexuality; that impedes her of using any contraceptive method or that forces her into marriage, pregnancy, abortion or prostitution, through the use of coercion, blackmail, bribery or manipulation; or that limits or nullifies the exercise of her sexual and reproductive rights”; and gender violence as “violence suffered by the fact of being a woman, regardless of race, social class, religion, age or any other condition, product of a social system that subjects the feminine sex” (Brasil, 2006, p.19-20).

2. ^“A esto hay que añadir que los agentes de socialización, con los medios de comunicación a la cabeza, están promocionando un tipo de relaciones basado en la atracción “instintiva” y “química” que busca a las que están “buenas” ya los “duros”, facilitando los desprecios, indiferencias y maltratos.” (Gómez, 2004, p. 131).

3. ^CAPES - Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - is a foundation of the Ministry of Education, and it plays a fundamental role in the expansion and consolidation of stricto sensu (master's and doctorate) postgraduate programs nationwide.

References

Abramovay, M. G. C., Luciano, A. P. S., and Cerqueira, M. (2016). Diagnóstico Participativo Das Violências Nas Escolas: Falam Os Jovens. Rio de Janeiro: Flacso. Available online at: http://flacso.org.br/files/2016/03/Diagn%C3%B3stico-participativo-das-viol%C3%AAncias-nas-escolas_COMPLETO_rev01.pdf

Aguilar, R. C., Alonso, O. M., Melgar, P., and Molina, S. R. (2009). Violencia de Género En El Ámbito Universitario, Medidas Para Su Supoeración. Revista Interuniversitaria de Pedagogía Social 16, 85–94.

AVON Instituto and Data Popular (2014). Violência Contra Mulher: O Jovem Está Ligado? Available online at: http://agenciapatriciagalvao.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/pesquisaAVON-violencia-jovens_versao02-12-2014.pdf.

Barsted, L., and Pitanguy, J. (2011). O Progresso Das Mulheres No Brasil 2003-2010. ONU Mulheres. Rio de Janeiro: CEPIA; ONU Mulheres. Available online at: http://onumulheres.org.br/wp-content/themes/vibecom_onu/pdfs/progresso.pdf

Botton, L. D., Puigdellívol, I., and De Vicente, I. (2012). Evidencias científicas para la formación inicial del profesorado en prevención y detección precoz de La violencia de género. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación Del Profesorado 73, 41–55.

Brasil (2006). Lei Maria da Penha: Lei no 11340, de 7 de agosto de. que dispõe sobre mecanismos para coibir a violência doméstica e familiar contra a mulher. Brasília: Câmara dos Deputados, Edições Câmara 2010, 34.

Bujosa, M. C., Beneira, R. M. A., and Grande, M. D. P. (2012). Luces y sombras En La formación sobre prevención y violencia de género valoración y percepción del profesorado, estudiantado y movimientos sociales. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación Del Profesorado 73, 57–74.

Castro, M., and Mara, L. C. (2014). The social nature of attractiveness: how to shift attraction from the dominant traditional to alternative masculinities. Int. Multidiscipl. J. Soc. Sci. 3, 182–206. doi: 10.17583/rimcis.2014.1173

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th Edn. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Duque, E., and Teixido, J. (2016). Bullying y Género. Prevención desde la Organización Escolar. Multidiscipl. J. Educ. Res. 6, 176–204. doi: 10.17583/remie.2016.2108

ÉNOIS Instituto (2015). Menina Pode Tudo. Available online at: http://www.agenciapatriciagalvao.org.br/dossie/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/ENOIS_meninapodetudo2015.pdf

Flecha, A. (2012). Educación y Prevención de La Violencia de Género En Menores. Multidiscipl. J. Gender Stud. 1, 188–211. doi: 10.4471/generos.2012.09

Flecha, A., Melgar, P., Oliver, E., and Pulido, C. (2010). Socialización preventiva en las comunidades de aprendizaje. Prev. Soc. Learn. Commun. 67, 89–100.

Flecha, R., Puigvert, L., and Ríos, O. (2013). The new alternative masculinities and the overcoming of gender violence. Int. Multidiscipl. J. Soc. Sci. 2, 88–113. doi: 10.4471/rimcis.2013.14

Fonseca, C. (2009). Quando Cada Caso NÃO é um Caso: Pesquisa Etnográfica e Educação. Revista Brasileira De Educação, 10, 58–78.

Gómez, A., Elboj, C., and Capllonch, M. (2013). Beyond action research: the communicative methodology of research. 6, 183–97. doi: 10.1525/irqr.2013.6.2.183.183

Gómez, J., Latorre, A., Sánchez, M., and Flecha, R. (2006). Metodologia Comunicativa Critica. Barcelona: El Roure.

INCLUDED (2012). Final Includ-ed Report Strategies for Inclusion and Social Cohesion in Europe From Education. Available online at: http://creaub.info/included/wpcontent/uploads/2010/12/D25.2_Final-Report_final.pdf (Acessed Feb, 2017).

Jaime, M. C. D., McCauley, H. L., Tancredi, D. J., Nettiksimmons, J., Decker, M. R., Jay, G., et al. (2015). Athletic coaches as violence prevention advocates. J. Interpers. Viol. 30, 1090–1111. doi: 10.1177/0886260514539847

Katz, J. H., Heisterkamp, A., and Fleming, W. M. (2011). The social justice roots of the mentors in violence prevention model and its application in a high school setting. Viol. Against Women 17, 684–702. doi: 10.1177/1077801211409725

Mertens, D. (2015). Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Sage.

Nesello, F., Lopes, F. S., Santos, H. G., Andrade, S., Maffei, M. A. E., and González, A. D. (2014). Características da violência escolar no Brasil: revisão sistemática de estudos quantitativos. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Materno Infantil 14, 119–136. doi: 10.1590/S1519-38292014000200002

Oliver, E. (2014). Zero violence since early childhood: the dialogic recreation of knowledge. Qual. Inquiry 20, 902–908. doi: 10.1177/1077800414537215

Oliver, E., and Valls, R. (2004). Violencia de Género : Investigaciones Sobre Quiénes, Por Qué y Cémo Superarla. Barcelona: El Roure.

Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: development and some important challenges. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 751–780. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516

Padrós, M. (2012). Attractiveness male models in adolescence. Masculinities Soc. Change 1, 165–83. doi: 10.4471/MCS.2012.10

Ríos, O. (2009). Socialització De Gènere: La Construcció De La Masculinitat a L'Escola. Barcelona: Universitat De Barcelona Departament.

Rosa, V., Puigvert, L., and Duque, E. (2008). Gender violence among teenagers: socialization and prevention. Viol. Against Women 14, 759–85. doi: 10.1177/1077801208320365

Tremblay, R. E., Gervais, J., and Petitclerc, A. (2008). Early Learning Prevents Youth Violence. Montreal, QC. Available online at: http://www.excellence-earlychildhood.ca/documents/tremblay_aggressionreport_ang.pdf

UNESCO-United Nations Scientific and Educational, and Cultural, O.rganization. (2017). School Violence and Bullying: Global Status Report. Paris. Available online at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002469/246970e.pdf

Unicef (2012). The State of the World's Children 2012: Children in an Urban World. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/iran/SOWC_2012-Executive_Summary_EN_13Mar2012.pdf

Valls, R., Torrego, L., Colás, P., and Ruiz, L. (2009). Prevención de la violencia de género en las universidades: valoración de la comunidad universitaria sobre las medidas de atención y prevención. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Prof. 23, 41–57. Available online at: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/274/27418821004.pdf

Vidu, A., Valls, R., Puigvert, L., Melgar, P., and Joanpere, M. (2017). Second order of sexual harassment -SOSH. REMIE Multidiscipl. J. Educ. Res. 7, 2014–2862. doi: 10.17583/remie.2017.2505

Waiselfisz, J. (2015). Mapa Da Violência 2015 - Homicídio de Mulheres No Brasil. Vol. 1. Brasília: Flacso. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

World Health Organization–W.H.O. (2013). Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-partner Sexual Violence. Geneva. Available online at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85239/1/9789241564625_eng.pdf?ua=1

Keywords: gender-based violence, school, gender-based violence prevention, intervention, violence against women

Citation: Prezenszky BC, Galli EF, Bachega D and de Mello RR (2018) School Actions to Prevent Gender-Based Violence: A (Quasi-)Systematic Review of the Brazilian and the International Scientific Literature. Front. Educ. 3:89. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00089

Received: 06 June 2018; Accepted: 21 September 2018;

Published: 01 November 2018.

Edited by:

Isabel Menezes, Universidade do Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Marta Pinto, Universidade do Porto, PortugalCinzia Albanesi, Università degli Studi di Bologna, Italy

Copyright © 2018 Prezenszky, Galli, Bachega and de Mello. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bruno C. Prezenszky, YnJ1Y29ycHJlQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Bruno C. Prezenszky

Bruno C. Prezenszky Ernesto F. Galli

Ernesto F. Galli Denise Bachega

Denise Bachega Roseli R. de Mello

Roseli R. de Mello