- 1Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, Morgridge College of Education, University of Denver, Denver, CO, United States

- 2Educational Leadership and Foundations, Curry School of Education, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, United States

For over 30 years, proponents of district effectiveness have promoted a fairly consistent set of key practices to enable district-wide improvement; yet, the state of district effectiveness has changed very little. This paper examined three decades of research on district practices associated with school performance and student achievement to gain a better understanding of the utility of this research-base in fostering district improvement. This study used a sample of 98 peer reviewed journal articles, reports, books and book chapters, and working papers to explore (1) patterns in the research design by categorizing research types and reporting sampling methods, such as sample size and sample type; (2) patterns of district characteristics in the sample by looking at types of districts, documenting urbanicity, looking at student enrollment, and discussing the socio-economic status of the student population; and (3) patterns of authorship and research productivity by surveying the concentration of authors and determining the proliferation of data sets. Importantly, this analysis found the research base on district practices to be too limited to serve as a comprehensive guide for stakeholders at various levels of the system seeking to support district improvement. We argue that the research base is too narrow and only applicable to certain types, locations, and size of districts. Furthermore, most of the studies take place in urban districts undergoing reform, which is not generalizable to most of the districts in the United States-largely smaller, rural districts. Lastly, when you consider the authorship of these studies, the base gets even narrower, as many authors produced multiple papers from one research study; one the other hand, the remaining studies seem to be from scholars who do not consider district effectiveness as their primary research interest. In order to better understand what district practices are most effective at promoting the ability of a district to achieve the mission of delivering high quality and equitable educational experiences for each student, we make recommendations for future research.

If They Knew Then What We Know Now, Why Haven't Things Changed?

Since the 1980s, federal and state governments have placed increased pressure on schools, teachers, and leaders to enhance student achievement. Students have been graded; educators have been graded; and schools have been graded. Districts, thus far, have averted the scrutiny devoted to buildings and classrooms. Nonetheless, a significant amount of attention has been paid to district effectiveness. Indeed, nearly a hundred journal articles published over a 30 year span of time detail the structures and practices of effective districts, contributing to a general agreement that district structures and practices matter and that there is a set of best practices for facilitating district improvement (Hightower, 2002; Anderson and Young, 2018).

Collectively, the body of research on district effectiveness has attempted to answer the following two questions. (1) Do school district practices and structures matter for school performance and student achievement? (2) If so, what district practices and structures matter for effective schools and student achievement? A preliminary examination of the literature on school district effectiveness revealed a significant amount of consistency among key findings related to district practices. Taken together, the literature suggests a framework for district effectiveness (Anderson and Young, 2018). This paper is part of a collection of three complementary papers, published separately due to the extensive content. Collectively, the three papers provide significant insight into the content and condition of research on district effectiveness. One paper provides an explanation of the framework, indicating the distribution of support for each feature of the framework. A second paper examines the research findings in greater detail, noting patterns in the findings across studies, contexts, and time periods. This third paper provides a close examination of methods and data sources and raises important questions about quality, robustness, and applicability.

What is District Effectiveness?

The notion of district effectiveness emerged from the school effectiveness literature of the 1980s (Brookover, 1979; Edmonds, 1979; Venezky and Winfield, 1979; Glenn and McLean, 1981; Bossert et al., 1982; Purkey and Smith, 1983; Rowan et al., 1983; Cuban, 1984; Hallinger and Murphy, 1986). This research established the characteristics of effective schools, particularly school-level organizational factors and classroom-level processes that set effective schools apart from less effective schools. The purpose of this scholarship was to identify model school-level practices that could inform efforts to increase the overall effectiveness of schools.

Since the 1980s, consensus has developed around the school and classroom characteristics necessary for effective schools. The same cannot be said for beliefs about the districts' role in supporting school or classroom level effectiveness. In fact, scholarship characteristic of this time period tended to either ignore the role of districts in supporting school effectiveness or suggest that decision making authority, control of resources, instructional purview, and accountability for student learning be placed at the school level (Chubb and Moe, 1990; Malen et al., 1990; Hallett, 1995; Elmore et al., 1996; Goertz et al., 2001). With the increase of federal accountability and the growing focus on reform in the late 1990s, this situation changed significantly and attention shifted back to the district's role in supporting school effectiveness and student learning.

Previous researchers have defined district effectiveness in terms of the policies, practices, and characteristics of districts that enhance high quality instruction intended to ensure better student learning and outcomes for all students (Hallinger and Murphy, 1986; Peterson et al., 1987; Elmore and Burney, 2002; Hightower, 2002; Togneri and Anderson, 2003; Iatarola and Fruchte, 2004; Dailey et al., 2005; Rorrer et al., 2008; Bottoms and Fry, 2009; Leithwood, 2010). Based on school effectiveness research of Cuban (1984) and Rowan et al. (1983), Hallinger and Murphy (1986) defined district effectiveness as the practices and characteristics associated with important student outcomes, specifically “the basis of their ability to promote high levels of student achievement on standardized tests (aggregated to the district level) after controlling for socioeconomic status, previous achievement, and language proficiency” (p. 175). Additional research explored effectiveness by concentrating on the districts role in marshaling and coordinating operations and resources to encourage high quality instruction (e.g., Peterson et al., 1987; Iatarola and Fruchte, 2004).

Building on definitions of district effectiveness that are tied to student learning outcomes, Rorrer et al. (2008) identified effective district practices as those focused on increasing student outcomes with the intention of enhancing equity. This notion of increasing equity is also present in a foundational review by Leithwood (2010) defining effective districts as those most successful in closing the achievement gap. District effectiveness research also focuses on the district's role in initiating and monitoring reform to raise student achievement (Hightower, 2002; Dailey et al., 2005; Bottoms and Fry, 2009) and in supporting continuous improvement and school reform (Elmore and Burney, 2002).

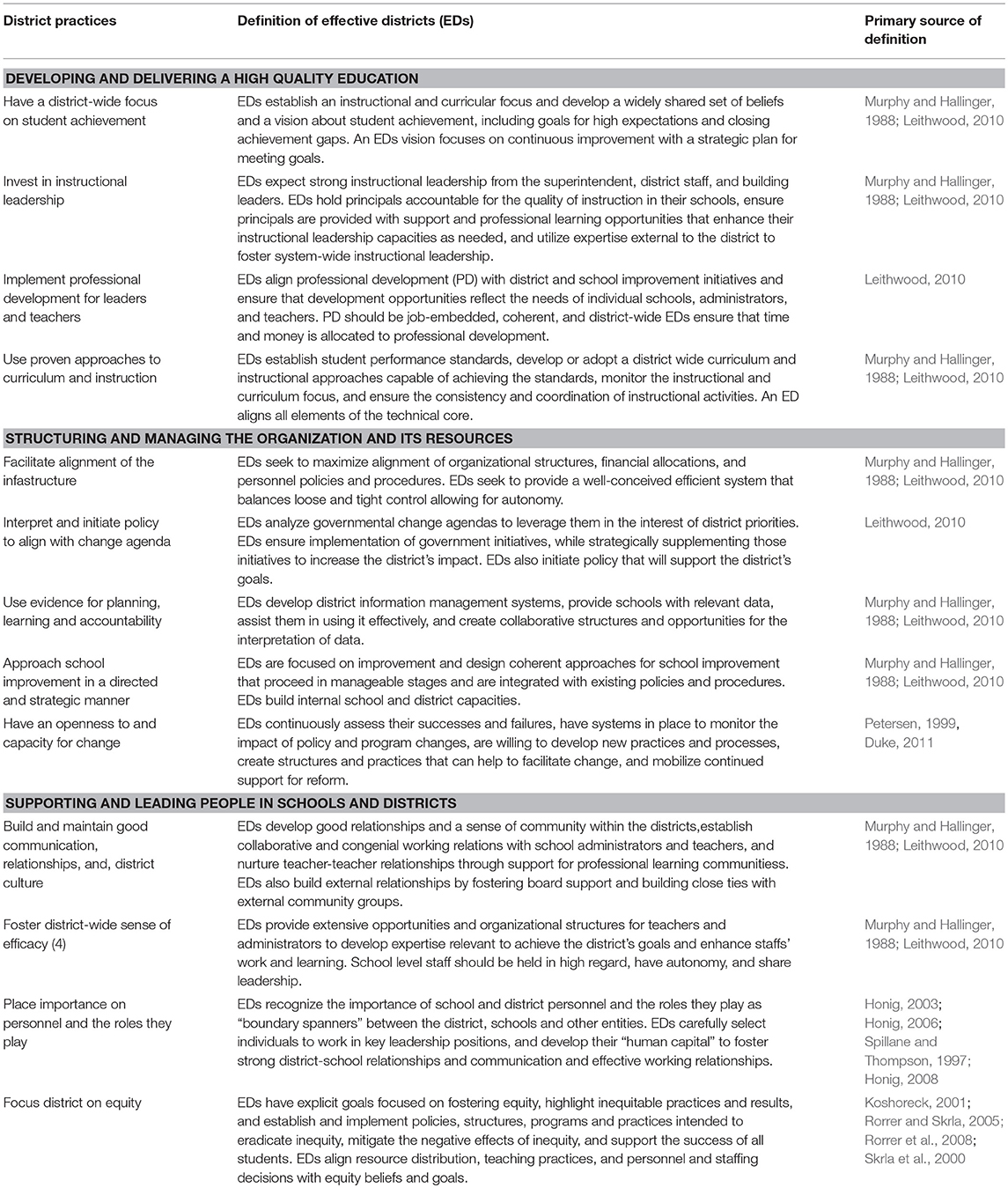

Based on the above literature, the definition of district effectiveness operating in this review of research includes the presence of practices that promote the ability of a district to achieve the mission of delivering high quality and equitable educational experiences for each student. These practices have organized into three domains, (a) focusing on supporting and leading people who work in schools and districts, (b) structuring and managing the organization and its resources, and (c) developing and delivering a high quality education. Each of these practices is delineated in the following district effectiveness practices framework.

Two seminal pieces of research provided a strong anchor for this district effectiveness framework, the first published by Murphy and Hallinger in 1988 and the second published by Leithwood in 2010. Murphy and Hallinger's (1988) Characteristics of instructionally effective school districts, an exploratory study involving interviews with superintendents from 12 effective districts in California, was designed to identify a set of district characteristics that led to greater school effectiveness. Murphy and Hallinger divided their findings into major characteristics and practices, which included (a) characteristics of curriculum and instruction (goal driven, established instructional and curricular focus, consistency and coordination of instructional activities); (b) climate factors (productivity focus, improvement focus, problem-solving focus, instrumental orientation, internal focus); (c) conditions (labor peace, board support, and community acceptance); (d) monitoring of instructional and curricular focus; (e) organizational dynamics (rationality without bureaucracy, structured district control with school autonomy, systems perspective with people orientation, strong leadership with active administrative team); and (f) strong instructional leadership from the superintendent.

The second study published over 20 years later by Leithwood (2010) was titled, Characteristics of effective districts. For this study, Leithwood conducted an extensive review of research. His 10 characteristics included the practices highlighted by Murphy and Hallinger (1988), though he used different language to describe them. Leithwood's characteristics included (a) building and maintaining good communications and relations, learning communities, and district culture; (b) facilitating infrastructure alignment; (c) fostering a district-wide sense of efficacy; (d) having a district-wide focus on student achievement; (e) investing in instructional leadership; (f) targeting and phasing in an orientation to school improvement beginning with interventions on low performing schools/students; (g) using evidence for planning, organizational learning, and accountability; and (h) using proven approaches to curriculum and instruction. In addition to confirming the findings of Murphy and Hallinger, Leithwood emphasized two new practices: (a) engaging strategically with the government's agenda; and (b) implementing district-wide, job embedded professional development.

Supplementing the practices identified in both Murphy and Hallinger (1988) and Leithwood (2010) are three additional practices supported by empirical evidence: (a) focusing on equity; (b) having an openness to change; and (c) placing importance on the individual. These 13 practices fit into three domains found to increase effectiveness, as defined by a focus on student learning and instructional outcomes. These include developing and delivering a high quality education, structuring and managing the organization and its resources, and supporting and leading people in schools and districts. All 13 practices and the accompanying definitions are included in our Framework for District Effectiveness (Anderson and Young, 2018) as captured in Table 1. The 13 practices succinctly summarize the findings of the research base.

Why Aren't More Districts Adopting Effective Practices?

Importantly, most of the district practices highlighted as essential for fostering school level effectiveness are virtually the same today as they were 30 years ago. Given the high level of agreement within the literature concerning effective district practices as well as the consistency of such findings overtime, we asked ourselves why so many districts continue to struggle. That is, if we know so much about the practices of effective districts, then why aren't more districts becoming increasingly effective? The answer to this question may be related to research translation and dissemination (i.e., perhaps research hasn't been effectively translated for use or disseminated in appropriate ways). Alternatively, the answer may rest with research utilization (i.e., perhaps research findings simply aren't being used by district staff). It is also possible that there is something about the research base that makes the findings difficult or inappropriate for widespread use.

Of the three explanations offered above, it is the third that we found most interesting and served as launching point for our research review. Three decades have passed since the first major study was published on district effectiveness (Murphy and Hallinger, 1988); the time seems fitting for a status check. The purposes of this article are twofold (a) to examine the methods, samples and designs of the studies making up the body of research on effective district practices; and (b) to assess the potential limitations of the research base for informing school district policy and practice. To address these purposes, this study involved an exhaustive search of research on district effectiveness published in the last 30 years.

Periodic reviews of research on various aspects of educational reform are both useful and necessary. Reviews are useful in that they provide a window on the state of knowledge in the field; they are also necessary for evaluating the quality and consistency of the evidence as well as the utility of approaches and methodologies central to the investigations (Lather, 1999; Boote and Beile, 2005; Hallinger, 2013). It is our intent to offer an informed assessment of the guidance provided by the literature on district practice and to provide insight into productive directions for future research.

Methods

In this section we explicitly delineate the search criteria, data extraction and treatment, and analytical procedures used in this review of research. Importantly, the methodology used for this exploratory review of research on district practices was shaped by the following three goals: to examine patterns among the research findings produced over the last 30 years, to examine patterns among the methods, sample and designs of the research studies; and to assess the utility of the recommendations offered through this literature base for promoting district effectiveness in varying contexts. Within this paper, we present, in detail, our findings related to the second and third goals.

The first stage of our research project was to establish a database of published research that reflected the above three goals. Our second step consisted of examining and comparing the studies included in our database with regard to their methods, samples and research designs. Our third step included the development and use of a framework for examining the patterns among the research findings (Anderson and Young, 2018). A fourth step was an exploration of how studies in our database were used in subsequent district effectiveness literature. Finally, we examined our data within and across stages to draw out pertinent findings, implications and recommendations.

Search Procedures

When we began our project, the focus of our research review was on district structures and practices. As such, we identified literature to include in the review using the search terms, “district practices” and “district structures.” We searched the Google Scholar site as well as seven Ebsco Databases related to education accessed through our University library system. These included (a) Education Full Text (H.W. Wilson), (b) Education Index Retrospective: 1929–1983 (H. W. Wilson), (c) Education Research Complete, (d) ERIC, (e) Index to Legal Periodicals & Books Full Text (H.W. Wilson), (f) Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, and (g) SPORTDiscuss with Full Text.

An initial list of possible references was created from the results of the above searches. Subsequently, we examined the literature cited in these initial references for additional pieces to include in our review. Publications that were cited in two or more of our original sources were added to the list. This process continued until the list of articles reached saturation, and we found no new publications matching our search criteria. We then limited our database to articles published within the last 30 years, given that the majority of work focused on district structures and practices was published during this period.

For this review we examined a wide range of possible sources, including both empirical and conceptual scholarship, in an effort “to identify all potentially relevant studies” (Hallinger, 2013, p. 8). The total number of articles, reports, and books making up our original database for this review was 237. The database was subsequently reduced following a closer review of each publication and a comparison to our Framework for District Effectiveness, defined in Table 1 (Anderson and Young, 2018).

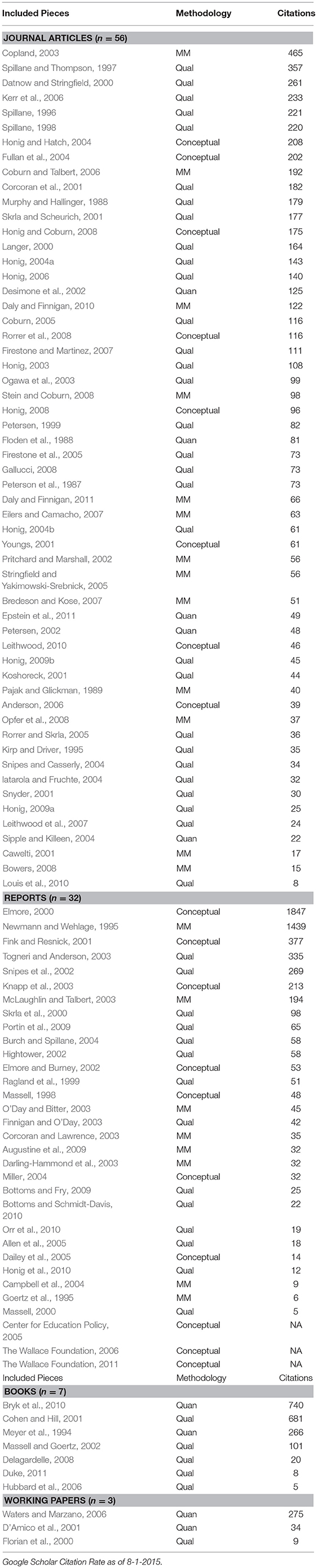

The final database for our review consisted of 98 sources. Our database included journal articles, reports, books, book chapters, and working papers/conference papers, though the majority (approximately 57%) consisted of peer-reviewed journal articles. Fifty of the sources (approximately 51%) were qualitative, 18 were conceptual (approximately 18%), 21 utilized mixed methods (approximately 21%), and 8 were quantitative studies (approximately 8%). The conclusions made within this review are directly linked to this sample of studies. The full list of publications, by publication type, citation count and methodology is provided in Table 2. In the following subsection we provide a brief overview of each of these publication categories.

Journals

In academic publishing, peer-reviewed journal articles exemplify the most rigorous practices in the field. Before an article is deemed appropriate for publication, the piece undergoes a review process to ascertain its accuracy and quality, to assess the validity of the research methods and analytical procedures, and to determine its contribution to the existing body of knowledge in a given field. Fifty-six of the studies included in our database were published in academic journals. Over half of these articles were published in six journals. Specifically, we included seven articles from Educational Administration Quarterly, six articles each from two journals (American Educational Research Journal, Educational Policy), five articles from two journals (American Journal of Education, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis,) and four articles from Leadership and Policy in Schools. Four additional journals contained two articles (Educational Policy Analysis Archives, Educational Leadership, Education and Urban Society, Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk). The remaining 15 articles were pulled from journals with only one relevant published source. A specific list of journals is provided in a companion article (Authors, under review) or can be obtained from the reference section.

Reports

Research published in reports may utilize methods similar to those used in journal articles, but there are several important differences. First, the research shared in reports is often conducted or sponsored by private organizations with interests that may influence how and which data is reported (Welner, 2010). Additionally, reports tend to allocate less space to methods sections, and thus provide less transparency in this regard. Lastly, reports rarely undergo a blind, peer-reviewed process, which makes it more difficult for readers to ascertain the validity and reliability of the research findings. Nonetheless, the most highly cited publication included in this review, Elmore (2000), was a report with a total of 1,847 citations.

The reports included in this review were published by a variety of centers, both university-based and private. Fourteen of the studies were conducted or sponsored by university-based educational research centers. The remaining reports were produced by privately funded centers with a concentration on educational research. The Wallace Foundation produced eight of the reports (The Wallace Foundation, 2006, 2011; Augustine et al., 2009; Bottoms and Fry, 2009; Portin et al., 2009; Bottoms and Schmidt-Davis, 2010; Honig et al., 2010; Orr et al., 2010). Additionally, five of the reports were published by independent centers focused on educational research, such as the American Institutes for Research. Three studies came from regional educational research centers, such as the Mid-continent Research for Education and Learning. Finally, two reports were produced by policy organizations, such as the Center for Education Policy.

Books and Book Chapters

Books in this review generally reflected one of two formats, either a summary of a body of research or a presentation of results from one research study or a collection of results from closely related studies. Single-authored books generally provided a synthesis of current literature or understandings developed by the author over a course of their career. Several of the books and chapters in this review present original research. Two of the books (Cohen and Hill, 2001; Hubbard et al., 2006) and one chapter (Massell and Goertz, 2002) summarized research on school reform, and one book chapter focused on district organizational theory (Meyer et al., 1994). The variety of book publishers operating today makes an assessment of quality daunting; however, according to Association of College and Research Libraries, university presses continue to rank highest for quality. Among the nine books and book chapters included in this review, four were published by university presses two were published by Routledge one was published by SAGE, one was published by Rowman and Littlefield, and one was published by the RAND corporation.

Working Papers

We included three working and conference papers in our review. Although these pieces did not undergo peer-review, they were cited in several comprehensive research reviews and journal articles. Two of the research reviews included in our database cited two of the conference papers (Florian et al., 2000; D'Amico et al., 2001). The working paper, a metanalysis of research on district effectiveness, was cited by 275 publications (Waters and Marzano, 2006). As noted above, we sought to include as much of the scholarship relevant to our research questions as possible. Despite our efforts to undertake an exhaustive review, we are aware that we may have missed relevant publications. Still, we are certain our search more than adequately represents the existing research base between 1985 and 2014.

Data Extraction and Treatment

Data extraction and treatment involved excerpting information from each of the pieces of scholarship included in our database and organizing them into an excel chart. The chart included the following categories: (a) additional notes, (b) argument/ questions, (c) citations, (d) connections, (e) district characteristics, (f) Framework for District Effectiveness theme/s (Anderson and Young, 2018), (g) methodology, (h) participants/study sample, (i) publication author/s, (j) publication findings, (k) publication source, (l) publication title, and (m) publication type. The articles were reviewed to gather information for each cell. In some cases, information was directly extracted (e.g., research questions, descriptive information), whereas in other cases, information was summarized (e.g., ascertaining connections to other research). Additionally, we made judgments about each publication, such as which Framework for District Effectiveness practice(s) (see Table 1) best represented the findings of the research. Finally, we gathered citation information from Google Scholar for each publication.

We reduced the number of sources included in our database by reviewing each source twice or more to ensure accurate data extraction. Then, we eliminated sources that did not fully satisfy our review criteria. The research must have (a) examined either district practices or district structures; (b) focused on district effectiveness; (c) been published during or after 1985; (d) resulted in an empirical study, a review of empirical research, or a conceptual piece that referenced key empirical pieces; and (e) taken place within the United States. This process resulted in the reduction of our original 237 sources to a final count of 98. The most common reason for removing a source from our database was its lack of relevancy to district effectiveness.

In addition to the above steps, it is important to share two additional pieces of information. First, our database initially included research focused on district structures. However, analyses of this data set yielded no significant relationships related to our research questions, and, as a result, those publications were part of the 139 removed from our database and analyses. Second, an additional goal of our larger project was to review the nature of the findings produced over the last 30 years. This analysis was conducted and resulted in significant findings. These findings are incorporated into a separate publication (Authors, Under Review).

Data Evaluation and Analysis

Once we developed an initial database of information in our excel file, we were able to consider a number of questions about the nature of this research base. Our inquiry unfolded in an iterative fashion as we explored the data. A primary goal of this review was to carefully examine the nature of the research comprising this knowledge base. Thus, our analysis involved a close examination of research purpose, designs, methods, and sample. First, we divided the studies into four research types: (a) conceptual, (b) mixed methods (c) qualitative, or (d) quantitative. The category “conceptual” included research reviews, research summaries, framework building, and policy reports. Second, we divided the publications into five categories of publication types: journal articles, reports, books/book chapters, and unpublished/working papers.

Subsequently, the studies were examined to see how the districts were chosen; for instance, were they purposeful samples chosen for a specific reason or convenience samples chosen for their availability or locale. We then determined what perspectives (e.g., district personnel, building leaders, teachers, etc.) were included in the sample. Next, we explored the sample sizes of each study, the number of districts included in a given study, as well as the geographic locations, size, and types of districts included in each study. We also examined the concentration of study authors and citations. These data were then explored for patterns and trends. Lastly a number of tables and graphs were created in order to organize, analyze, and display the data.

Results

In this paper, we address the second of our research goals: to examine patterns among the methods, sample and designs of the research studies produced over the last 30 years. Below, we share the findings resulting from our examination in six major sections, reflecting the steps of our analysis. The first section presents our categorization of the studies into four research types: (a) conceptual, (b) mixed methods (c) qualitative, or (d) quantitative. The category “conceptual” included research reviews, research summaries, and conceptual work and policy reports. The second section focuses on site selection, participant selection and sampling decisions for each study. In particular, we identified whose perspectives (e.g., district personnel, building leaders, teachers, etc.) were included in the sample. The third section shares our findings regarding sample size (i.e., the number of informants included in each study) and the number of districts included in a given study. The fourth section focuses on district characteristics. Specifically, for each study we examined the type of district(s) included in the study (i.e., urban, suburban, rural, undergoing reform, etc.), the districts' reform status, the districts' student enrollment, and the socioeconomic status of the districts' student population. Part of this step involved examining how the districts were chosen; for instance, were they purposeful samples chosen for a specific reason or convenience samples chosen for their availability? The fifth section presents the geographic distribution of the districts across the United States. The sixth section focuses on how many of the publications included the same authors and/or the same data sets. Finally, the seventh section presents patterns in the database in terms of date of publication. These findings provide the basis for our discussion and conclusions concerning the utility of the research base to serve as a comprehensive guide for supporting district effectiveness.

Research Type

Qualitative

The methodology employed in a study determines the generalizability of the findings to other settings. The majority of research included in this review (i.e., 50 of the 98 publications) employed a qualitative design, primarily a case study model. Thirty of these studies were published in peer-reviewed articles, 14 in reports, five in books or book chapters, and one was a working paper.

Qualitative research is meant to capture a phenomenon in a specific context by focusing on the interaction of the people and organizational structures (Maxwell, 2005). It allows the researcher to gather evidence with practical and functional uses (Stake, 1995). Despite the many benefits of qualitative research, however, findings from individual qualitative projects are time and context bound; they are not generalizable beyond the sites included in any given project (Maxwell, 2005). Although the findings gleaned from single case studies can be aggregated and used for theory building, they are often misused and presented as evidence of generalizable practices, trends or solutions. Indeed, this was the case in a number of the district effectiveness research reviews, which relied heavily on qualitative research studies.

Although the question of selection will be considered in greater detail in a later section, three issues are worth noting here. First, the majority of studies used a sample consisting of between one and five schools or districts for comparison. Second, it appears that the districts were chosen largely because they were undergoing a reform effort, a selection decision with implications for generalizability. That is, the findings from a study focused on districts undergoing reform, will be more useful to districts in similar situations and less useful for an average district seeking to become more effective. Finally, all but a few of these studies were conducted in urban districts, which compounded by the use of qualitative methods, further limits the researcher from being able to make claims that study findings and recommendations can be “taken to scale” by policy makers or district leaders.

Quantitative

Quantitative findings can be generalized if a study uses appropriate sampling procedures. Nine of the studies were quantitative, with five of those publications appearing in a peer-reviewed journal. The five journal articles represented a broad swath of districts, with one study exploring 400 districts (Desimone et al., 2002) and one exploring 121 of 643 districts in one state (Sipple and Killeen, 2004). Three studies included districts in five to 30 states (Floden et al., 1988; Petersen, 2002; Epstein et al., 2011). In the study conducted by Sipple and Killeen (2004) and Desimone et al. (2002), the researchers examined the implementation of external policy reforms driven by accountability. Two of the quantitative publications were working papers (D'Amico et al., 2001; Waters and Marzano, 2006) and two appeared in books (Meyer et al., 1994; Bryk et al., 2010).

Mixed Methods

Twenty-one of the studies in this review used a mixed methods approach. Eight of these studies were published as reports and 13 were published in peer-reviewed journals. Of the 98 publications included in our database, several of the mixed methods studies provided the most in-depth evidence in support of the Framework for District Effectiveness themes (Anderson and Young, 2018). Furthermore, these pieces were distinctive given their sampling procedures or research design.

To illustrate, four of the mixed method studies used sampling procedures that ensured strong external validity. In one study, Leithwood et al. (2007) conducted an extensive mixed-methods project including 45 randomly sampled districts in nine states. Data for this analysis was gathered from 31 principals, who were interviewed during the first round of site visits conducted within a subset of 18 districts. Interviews sought to explain what school district conditions principals perceived to influence their sense of efficacy.

The Pritchard and Marshall (2002) study explored professional development practices in what the authors identified as “healthy” vs. “unhealthy” districts. These researchers conducted a 4-year study using 18 districts from 11 states in three parts of the U.S., randomly sampled from urban, rural and small towns. Along with extensive interviews of central office administrators, principals, and teachers, Pritchard and Marshall administered the Organizational Health Scale to all participants and collected 3,000 essays written about the schools from students in grades four and 11.

In another study with strong external validity, Opfer et al. (2008) sought to explore the effects of high stakes accountability in six states on district practices. Opfer et al. used purposeful random sampling to select 24 schools from districts in each of the six states to participate in a survey on district practices. For each state, six schools were drawn from each of the following four types of districts: districts with both high and low performing schools, districts with low performing but no high performing, districts with high performing but no low performing school, and districts with neither high performing nor low performing schools.

Another distinguishing characteristic of several of the mixed methods studies was the research design. Specifically, the studies reflected rigorous design models allowing for a deep understanding of research sites (e.g., including a wide range of participants or data sources to triangulate findings). For example, Bowers (2008) used multiple regression to identify a school within a mid-Western district demonstrating the largest positive difference in test scores within the state. His case study of the school and district included interviews with 59 individual teachers, eight principals, two assistant principals, six instructional facilitators, and 11 central office personnel. Additionally, he conducted three interviews each with the superintendent and assistant superintendent. The triangulation of perspectives within this study, from various levels of the system, ensured a more representative set of views.

Furthermore, Ogawa et al. (2003) conducted a longitudinal case study of a purposefully selected district designed to understand how and to what extent the standards-based curriculum shaped the instructional practices of teachers. They selected the district based on its adoption of a standards-based strategy that included both specific, local standards and a criterion-referenced test directly linked to standards. Over the course of the four-year study, they interviewed central office staff, principals, and teachers on multiple occasions. By spending a longer period of time and by collecting information from multiple sources, these researchers presented understandings that may be transferable to other similar districts.

Conceptual

For this review, we identified 18 conceptual pieces. These pieces are reviews and syntheses of the literature base on district practices and were included for two reasons. First, these reviews encompass a broad range of research and second, reviews of this nature are often relied upon by other scholars to map a particular area of a research base. The pieces we reviewed for this study included papers that discussed frameworks or theories applicable to districts and their schools (Honig and Hatch, 2004; Honig, 2008), summaries or reviews of current research (Youngs, 2001; Elmore and Burney, 2002; Fullan et al., 2004; Dailey et al., 2005; Anderson, 2006; The Wallace Foundation, 2006, 2011; Rorrer et al., 2008; Leithwood, 2010), or reports that summarized existing research and used those summaries to make suggestions for practitioners or policy makers (Massell, 1998; Elmore, 2000; Fink and Resnick, 2001; Knapp et al., 2003; Miller, 2004; Center for Education Policy, 2005). Some of these publications, for example the two The Wallace Foundation reports 2006; 2011, are described in a previous section.

Within this set of publications, we identified five reviews of previous research that met the criteria for inclusion in our database. These pieces varied in their breadth of focus and purpose. Taken together, these five reviews incorporated a large volume of empirical, theoretical and policy literature. However, whether researchers, practitioners or policy makers can reliably use all of these pieces for further inquiry or action is questionable.

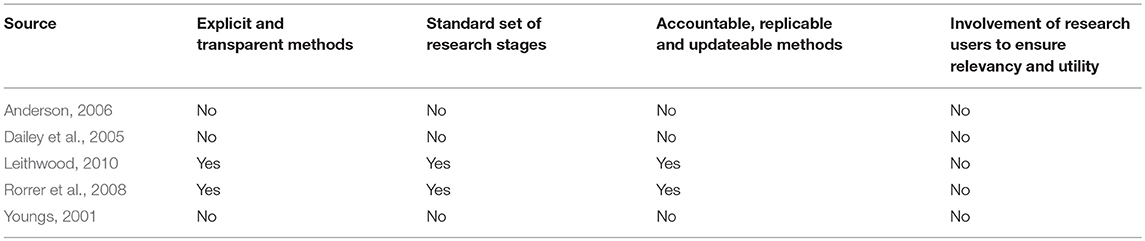

According to Hallinger's (2013) exemplary research review analytical rubric, key features of systematic reviews include (1) explicit and transparent methods, (2) a standard set of research stages, (3) accountable, replicable and updateable methods, and (4) involvement of research users to ensure relevancy and utility. None of the research reviews included in our database were featured in Hallinger's analysis of reviews of research in educational leadership; however, his rubric provides a useful tool for evaluating such scholarship. Using Hallinger's rubric, we found that only two of the five reviews met three of the four criteria for exemplary reviews. These findings are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3. Evaluation of conceptual reviews (based on Hallinger, 2013).

The Anderson (2006) piece is a working paper that looked at findings related to the role districts played in reform, specifically those studies highlighting strategies implemented to improve student learning, challenges districts faced when implementing strategies, and impact of the strategies on teaching and learning (p. 5). This paper did not include an explicit methods section. As a result, the piece would not qualify as an exemplary review.

The Dailey et al. (2005) review was conducted by the American Institutes for Research (AIR) and was intended to answer the question, “What does the research and public policy literature suggest about (a) the components of high-performing, high-poverty school districts and (b) the strategies that help districts move toward effectiveness?” (p. 1). In a brief methods section, the researchers suggested that they prepared a bibliography based on “input of experts both internal and external to AIR,” including policy papers, advocacy statements, and academic research and subsequently determined which sources seemed most relevant (Dailey et al., 2005, p.2). Three other pieces of information were useful in determining the quality and nature of the review. First, the authors suggested that the bibliography grew but do not explain how. Second, the methods section suggested that the authors chose to use newer research, but then also used existing literature reviews as secondary sources to include older sources as evidence. Third, Dailey et al. explicitly characterized their review as descriptive and noted that they did not examine the quality of the research included in their review.

Youngs (2001) review focused specifically on how the district and state influence professional development and school capacity. He did not include a method section in the review; rather, he explained that he chose to focus on four reform efforts centered around professional development, specifically teacher networks in California, literacy reform in New York City's District 2, student assessment systems in Kentucky and Maryland, and school improvement (SI) plans in South Carolina (Youngs, 2001, p.282). Youngs did not provide a clear rationale for how he selected those four reform efforts or the related research base.

The Leithwood (2010) review, which informed the Framework for District Effectiveness guiding this review, clearly laid out selection criteria, search procedures, and a plan for analysis. For example, a requirement for inclusion was defining district performance in terms of student achievement and either providing original evidence linking achievement variables to one or more of the characteristics or building on original research about high-performing districts. Also, it is important to reiterate Leithwood's acknowledgment that his review frequently cited the Rorrer et al. (2008) review, and drew many of the same conclusions, while answering a more broadly defined research question concerning the characteristics of effective districts.

Lastly, the Rorrer et al. (2008) review used a narrative synthesis methodology developed by Mays et al. (2005) applying six iterative stages for systematic reviews to explore the district role in systemic reform. Mays et al.'s stages include (1) identifying a focus, (2) narrowing the question, (3) selecting studies, (4) extracting data and appraising quality, (5) conducting the synthesis, and (6) reporting the results (Rorrer et al., 2008, p. 310–311). Rorrer et al.'s methods were the most explicit of the five literature reviews included in our dataset. The authors discussed their rationale for including certain pieces and provided the search terms and databases that were used to identify and cull the literature. Their review met the majority of the exemplary review requirements put forth by Hallinger (2013) and would be the easiest to replicate, making it the most empirically sound review to be conducted on district effectiveness to date.

In addition to looking at the nature of the five reviews, we also examined how these conceptual pieces were used within subsequent literature. As demonstrated in Table 2, each of these reviews have been cited, regardless of the clarity of the methods used to conduct the review. Perhaps more significantly, although conceptual pieces can be useful in summarizing and framing thinking about a problem or policy question, these publications can be used inappropriately. In regards to the five conceptual pieces under examination here, we found that several were used as primary sources of evidence of a theme or concept in subsequent publications.

Sample Participants

In addition to examining each study with regard to research type, we considered the breadth of perspectives included in each of the pieces. We found that the majority of empirical research studies of effective district practice included data drawn from multiple stakeholder communities. Specifically, 59 studies solicited information from school level leaders and 60 studies solicited information from district level administrators. In over half of the studies, the researchers included both levels of leadership in the study. The next largest group to be represented in the studies was teachers. Forty-six of the studies included teachers' perspectives and a smaller portion of studies included school board members, parents, community members and other stakeholders as informants.

The informants included in the studies we reviewed appeared appropriate, given the focus of the research and research questions posed. For example, teachers were commonly asked about the influence that district policy had at the student level. A smaller portion of studies included school board members as informants (n = 18). In the majority of studies school board members were included because the study focused on the work of the school board. In a limited number of studies school board members were included to provide an additional viewpoint on district effectiveness, to supplement the feedback from the principal or superintendent.

Sample Size

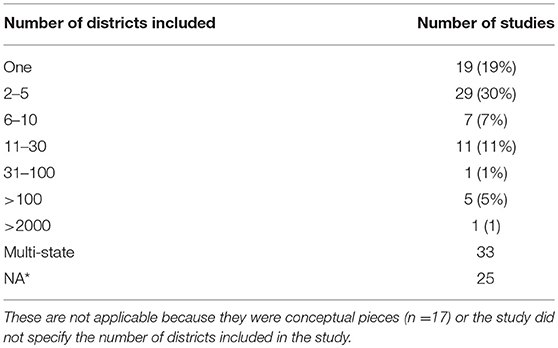

All but a few of the studies included in our database had rather small sample sizes, which further limits the transferability of research findings on district effectiveness. Only ten of the studies could be considered large in scale, with seven of the studies including more than 100 districts and three studies incorporating data from over 2,000 districts. As noted in a previous section, small-scale case studies and comparative case studies dominate the research base on district effectiveness. The majority of the studies we examined included less than five districts, with 19 encompassing only one district. Twenty-nine studies focused on two to five districts, seven of the studies included between six and ten districts, eleven of the studies collected data from between 11 and 30 districts, and one included between 31 and 100 districts in their research. Table 4 displays the number of studies reviewed for this project that included a given number of districts as well as the number of studies that included districts from more than one state.

Most of the qualitative studies focused on a small number of schools or districts, several explored a larger set of districts, increasing the applicability of their findings. For example, Langer (2000) conducted one of the most in depth qualitative studies included in this review. Over the course of 5 years, he collected data on school level conditions fostered by the district from 14 schools identified as “beating the odds,” and 11 schools achieving “typical” results. Also using qualitative methods, Bredeson and Kose (2007) conducted surveys and interviews with 400 superintendents in one state to better understand the actions of superintendents in response to reform. Finally, Datnow and Stringfield (2000) used data collected by the Systemic and Policy Research Team from 16 multi-year projects and 300 case studies. The 316 studies included in their database explored how districts and schools supported consistent and reliable reform.

Several studies used survey data to collect information from a broader range of participants. In the largest and most expansive study, Epstein et al. (2011) used survey data to collect information from 407 schools in 24 school districts in 15 states. The focus of their research was district and school conditions that fostered the role of family and community involvement in schools. Their data set also allowed them to compare data on schools that had consistent district leadership over a three-year time span with schools that did not. Additionally, Desimone et al. (2002) used telephone surveys to examine the professional development activities of 363 districts over a ten-year period, from July 1997 to December 1998. Using a much smaller sample, Floden et al. (1988) surveyed teachers in 20–30 districts in New York, California, Florida, South Carolina, and Michigan, concerning the role school level leaders and staff played in instructional leadership. Due to the larger sample sizes included in these studies, their findings may be applicable to other contexts.

Research on a Single District

Importantly, a striking number (n = 19) of the publications are based on data gathered within a single urban district. We provide four examples of this below. First, Snyder (2001) studied the New Haven Unified School District, which includes a majority of low-income schools with high achievement. Second, Stringfield and Yakimowski-Srebnick (2005) conducted a longitudinal study (1992–2003) of the Baltimore City Public School system, which is a large, high-poverty, urban school system. The researchers examined student achievement trajectories through three phases of federal and state initiated accountability reforms and used 6 years of student-level quantitative data to further explore the relationship. Third, Gallucci (2008) studied how a reforming urban school district located in the Pacific Northwest developed capacity to respond to policy and how teachers were supported in making the necessary changes in their instructional practice. His case study included district leaders, central office leaders, consultants, and school-based staff. Finally, Eilers and Camacho (2007) conducted a two-year case study of a high achieving elementary school located within an urban district that served disadvantaged children. Using a social systems context approach, they sought to describe the district leadership factors that contributed to an increase in student achievement.

Research on Several Comparison Districts

Other studies (n = 54) included comparison school districts. We mention four in this section. First, Iatarola and Fruchte (2004) conducted a qualitative comparison study of two high- and two low-performing New York City area districts to explore the conditions and practices that make districts more or less effective. Their data was drawn primarily from interviews with principals. Second, Snipes and Casserly (2004) conducted case studies of four large urban districts showing improvement including Charlotte-Mecklenberg, Houston, Sacramento City, and New York City. Cawelti (2001) studied six high achieving, low-income urban districts chosen from a sample of 80 urban districts that were part of the School District Effectiveness Study (SDES). Finally, Burch and Spillane (2004) conducted research for the Cross-City Campaign for Urban School Reform to highlight the importance of district-school interactions in the implementation of instructional improvement initiatives, especially through the roles of mid-level management. The study included interviews with 55 mid-level district staff and 59 individuals playing formal leadership roles within schools from three urban districts (Chicago, Milwaukee, and Seattle), all of which were undergoing reform efforts focused on decentralization.

District Characteristics

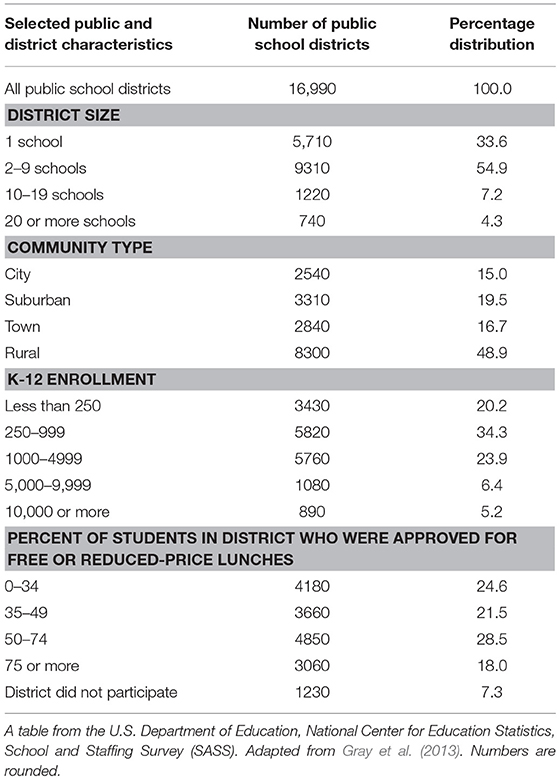

In addition to considering the number of districts included within studies of district effectiveness, it is important to consider the characteristics of the districts. Although a small percentage of the empirical studies in our database provided little or no demographic information about the district(s) included in their projects, most provided information on the location, size and reform status of the district. In the following subsections, we describe the empirical scholarship included in our dataset in terms of urbanicity, student enrollment size, percentage of students receiving free and reduced lunches, and the district's reform status. In order to for the findings from a study to be generalizable across a variety of district types, the study would need to include a variety of school districts types (e.g., rural, suburban, town, urban), districts of different sizes, and districts from geographically diverse states or regions.

Research in Urban Settings

We found that the majority of studies on district effectiveness were conducted in urban districts that were undergoing some kind of reform. In fact, of the publications included in this review, fifty-five of the sites were selected specifically because they were urban contexts. The remaining studies, which represent a majority of the articles in our dataset, focused on urban areas. Of these urban-based studies most described the districts as high-poverty and a handful described their sites as both high poverty and high achieving districts. Although studies of district effectiveness in complex urban systems contribute in important ways to the knowledge base on district effectiveness, it is essential to keep in mind that urban districts do not represent the vast majority of districts in the United States. Nor do the experiences of urban districts with reform or effectiveness accurately reflect those of non-urban districts.

Research in Non-urban Settings

Only one study purposefully selected a suburban district, one study selected four smaller districts, and four studies had a mixed sample of urban, suburban, and rural schools. Kirp and Driver (1995) conducted the only study in our database that explicitly selected a non-urban site. Their case study of a suburban school district in California explored the intersection of state and federal policy and local demands. Moreover, Louis et al. (2010) explored the role of the power structure, the state of networking, and the concept of loose coupling to examine how four smaller districts interpreted their relationship with state policy expectations. Explorations of more “typical” districts were severely limited in comparison to the evidence provided from large urban districts in need of full-scale improvement.

According to the data displayed in Table 5, which is drawn from the 2007 to 2008 School and Staffing Survey (SASS), only 13% of the districts in the U.S. are considered urban, meaning that 87% are rural (48%), suburban (21%) or town-based (18%). Of a total of 16,330 public school districts, the majority of districts (5, 210), or almost a third, encompass only one school, and only 750 districts, or five percent, contain 20 or more schools.

District Enrollment

Another distinguishing district characteristic is total student enrollment. According to data from the 2012 to 2013 school year, the majority, 34.3% of districts in the U.S. enroll between 250 and 999 students with 23.9% of districts enrolling between 1,000 and 4,999 students. Only 890 districts (5.2%) have 10,000 or more students. However, the majority of published research studies on district effectiveness were conducted in urban districts large student enrollments, such as (1) New York City, with a student enrollment of 995,336; (2) Chicago with a student enrollment of 405,644; (3) Houston, with a student enrollment of 204, 245; (4) Dallas, with a student enrollment of 157,162; (5) San Diego, with a student enrollment of 131,785; (6) Baltimore, with a student enrollment of 104,160; (7) Ft. Worth, with a student enrollment of 81,651; (8) Milwaukee, with a student enrollment of 81,651; (9) Boston with a student enrollment of 56,037; (10) Sacramento, with a student enrollment of 47,897; and (11) Seattle, with a student enrollment of 47,735. These enrollment numbers are far greater than 10,000 students, making them outliers as opposed to representative of most districts in the U.S.

Socioeconomic Status

Many of the urban districts represented in articles included in our database (n = 10) were also identified as high poverty. According to the SASS data, 3,060 (18%) of school districts had approved 75% or more of the students for free and reduced lunch, which is a standard measure of the poverty level in a school community. Only 28.5% of districts in the U.S. have a free and reduced lunch percentage of over 50%. These high poverty schools are usually located in both urban and rural areas, which are not differentiated in these SASS findings, however, districts with large portions of low-income students are not representative of the majority of the total districts in the United States.

Reform Status

Several studies did not identify district type but did suggest the existence of a reform effort in the focus districts. In total, sixty of the sites examined in the studies included in this review focused on districts undergoing a reform, most likely as the result of sanctions from accountability measures. Importantly, districts undergoing reform are in extreme states of change and may not reflect the practices needed to maintain an effective district when not facing large-scale reform efforts

An example includes the work of Peterson et al. (1987) who performed an exploratory study on the types of control and organization mechanisms in 12 school districts in one state. Similarly, Pajak and Glickman (1989) also did not identify the district type, but they did provide insight into the reform status of the district. Specifically, they explored the dimensions of school district improvement through a comparative case study of three Georgia districts that had demonstrated improvement in student achievement over 3 years.

Geographic Distribution

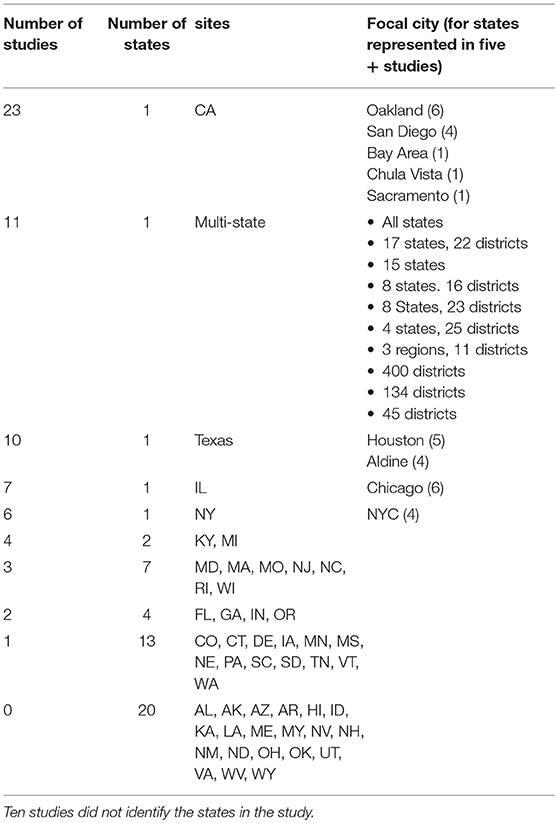

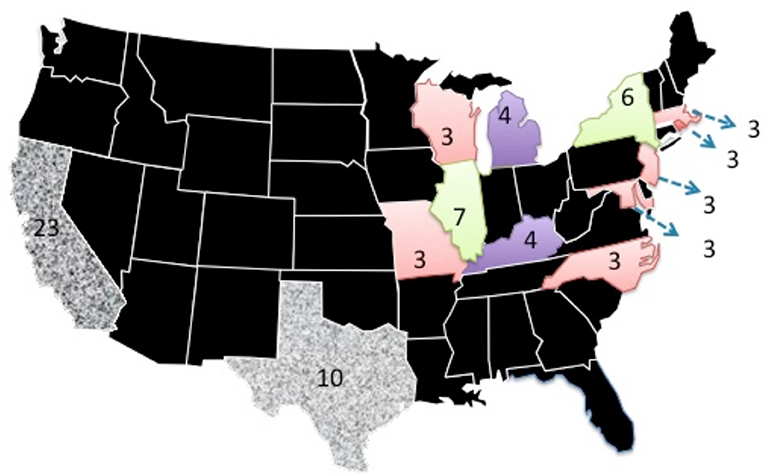

In addition to the district characteristic trends presented in the above section, we found that the studies making up the research base on effective district practice are concentrated in certain states and regions. Table 6 captures the number of studies that took place three or more states or regions. Twenty of the Fifty states were not included in any of the publications making up the base of knowledge on effective school districts. Additionally, 13 of the states and two regions, the South and the West, were represented in only one study, and four states were included in only two publications. Seven states and the Midwest region were included in three pieces. Two states were in four studies.

Furthermore, four states were heavily represented in the research base. Twenty-three studies included districts from the state of California, thirteen of which were located in urban areas, particularly Oakland and San Diego. Table 6 also captures this data. Ten pieces included sites from Texas, with three publications included finding from the same study of four Texas districts. Five of the reviewed pieces included Houston, a major urban area, and four included Aldine ISD, a district north of Houston serving students from the surrounding area. Seven studies included the state of Illinois, with six of them explicitly mentioning Chicago, and six studies included the state of New York, with four of the publication focusing on New York City. Finally, there were 10 studies that did not provide identifying information about the sample in order to ensure anonymity, three studies mentioned that the districts were from the South or West and four studies identified the sample as coming from the Midwest.

Eleven studies had large samples encompassing multiple states. Starting with the largest, one study included data from all the states, two studies included between 15 and 20 states, and two studies included a sample of eight states. The remaining studies included fewer than four states. Three studies mentioned including between 45 and 400 districts from multiple states. In order to better understand, the imbalance of geographical representation, Figure 1 displays all the states included in three or more of the publications from the sample for this review. Most of the Midwest, West and Deep South were not considered within the literature on district effectiveness. The urban areas on the northeastern seaboard and in the Great Lakes region as well as the states of California and Texas dominate the research base.

Concentration of Authors and Data Sets

In addition to mapping the geographic distribution of the studies, we also examined the contribution of individual and teams of scholars. We found a concentration of influence by several authors, many of whom published multiple papers on the topic of district effectiveness using the same dataset. There were 166 total authors included in our database (n = 98 sources). A large number of authors, 132 to be exact, participated in just one publication as either an author or co-author. Their contributions represented 53 sources of the 98 in the database, which is approximately 55%. In contrast a significantly smaller number of authors (n = 33) contributed to the remaining 45 sources. Specifically, 22 contributed to two pieces, six contributed to three pieces and five contributed to four pieces. Finally, one author, Honig, published the greatest number of studies, with 10 publications. We provide a closer examination of the authors contributing to four or more pieces in the following paragraphs.

Honig's contributions (nine journal articles and one report) represent over 10% of the pieces included in our database. Of the ten pieces of scholarship that she published on district effectiveness, seven were empirical. Six of which were single-authored pieces (Honig, 2003, 2004a,b, 2006, 2009a,b) and one was a co-authored piece (Honig et al., 2010). This body of research represents several longitudinal, comparative case studies within two school districts, Oakland, California and Chicago, Illinois. The remaining pieces published by Honig were conceptual (Honig and Hatch, 2004; Honig, 2008; Honig and Coburn, 2008). Only one of Honig's publications was published as a report (Honig et al., 2010); the rest were published in peer-reviewed journals. Thus, nine of the 57 journal articles included in our database (20%) and a quarter of the qualitative research studies included in our database, were authored by Honig and drawn from the experiences of two urban school districts.

The next highest number of publications represented in our database by author was four. Five authors contributed to four publications on effective district practices, including Anderson, Coburn, O'Day, Skrla, and Spillane. In most cases, their research was carried out with a colleague or team of colleagues. Three of Anderson's publications (Togneri and Anderson, 2003; Leithwood et al., 2007; Louis et al., 2010) were the result of collaboration. O'Day worked on research teams that published three policy reports (Goertz et al., 1995; Finnigan and O'Day, 2003; O'Day and Bitter, 2003; Dailey et al., 2005). Three of Coburn's pieces were co-authored (Coburn and Talbert, 2006; Honig and Coburn, 2008; Stein and Coburn, 2008). All of Skrla's pieces (Skrla et al., 2000; Skrla and Scheurich, 2001; Rorrer and Skrla, 2005; Rorrer et al., 2008) were co-authored, and two of Spillane's pieces were co-authored (Spillane and Thompson, 1997; Burch and Spillane, 2004).

In some cases collaboration involved the examination of a set of ideas or concepts across studies or contexts, whereas in others it involved deeper examinations of a single dataset or district context. Coburn's publications, for example, are based on four distinct projects. In the first study, Coburn (2005) conducted a cross-case study of “non-system” actors. In a second co-authored piece, Coburn and Talbert (2006) examined teachers from eight of an urban district's poorest schools to determine how the teachers and central office made sense of evidence based instruction. A third study, (Stein and Coburn, 2008), involved a longitudinal examination of two urban districts. Coburn's most recent publication (Honig and Coburn, 2008) was conceptual.

Skrla's contributions involved three interrelated studies. Skrla et al. (2000), as discussed previously, involved case studies in four large Texas school districts. Skrla and Scheurich (2001) and (Koshoreck, 2001) also published papers from this study. Spillane's contributions involved several distinct studies as well. Adding to the body of research focused on urban districts undergoing reform, Spillane (1996) presented case studies from two school districts in Michigan that were responding to accountability measures. Spillane (1998) looked at the role that districts played in implementing reading accountability measures in their schools. Similarly, Spillane and Thompson (1997) conducted case studies in nine school districts focusing on effective instructional reform.

In contrast, among the other authors contributing two or three pieces of scholarship on district effectiveness, the majority appeared to be based on either the same data set or multiple studies conducted in the same district or set of districts. For example, Petersen (1999) conducted an exploratory case study of superintendents, their principals and members of their boards of education in five California districts, and then conducted a companion study in the same five districts, administering the Instructional Leadership Personnel Survey (ILPS) to principals and school board members (Petersen, 2002). Similarly, Firestone, Firestone et al. (2005) and Firestone and Martinez (2007) were both based on data from three large urban districts in New Jersey.

Research Publication Dates

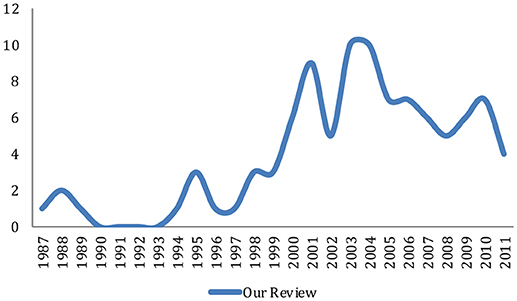

In order to better understand the nature of the literature included in our dataset, we conducted an exploration of the literature base over time, looking for trends that might align with the broader education and policy contexts. We first examined when each piece of literature included in our database appeared and grouped them by year. We then conducted a similar analysis with the literature associated with each of the thirteen Framework for District Effectiveness themes (Anderson and Young, forthcoming).

When looking at the trend over time for the total articles and reports culled for this review, it becomes clear that the field took greater interest in the practices of effective districts after the year 2000, with a peak of 19 studies published between 2003 and 2004. This trend is clearly demonstrated in Figure 2. A closer examination of these studies revealed that much of the reported data was collected between 1999 and 2003, at the start of the new federal policy of No Child Left Behind, which went into effect in 2001. Since the introduction of accountability-based policies, district research has maintained a higher level of research interest. However, after 2011 there has been a noticeable decline in published research focused on district practices, with no pieces deemed appropriate for inclusion in this review from the years 2012 or 2013. Figure 2 illustrates these publication trends, highlighting patterns of increase, decline and lack of publication activity.

Discussion

According to the SASS data presented above (2011–2012), there are 16,990 public school districts in the United States. Due to the uneven nature of district and state data systems, it is hard to determine exactly how many districts are struggling and how many are excelling. However, according to the US Department of Education, there are a number of districts that are failing to provide high quality instructional learning experiences for all students (United States Department of Education, 2015). As we asked in the introduction to this manuscript, “If we know so much about the practices of effective districts, why aren't more and more districts becoming increasingly effective?” Without a doubt, there are no simple answers to this question. In this paper, we suggest that part of the reason lies with the research base on effective district practices. Taken as a whole, our analysis found the district practices' research base to be too limited to serve as a comprehensive guide for stakeholders at various levels of the system seeking to support district improvement, particularly stakeholders working to improve the effectiveness of non-urban districts.

An alternative explanation for why the research isn't having a greater impact on the success of districts is that it is not accessible to district leaders. Many practitioners do not have access to peer-reviewed journal articles or the knowledge of which organizations produce high quality research reports ostensibly limiting the reach of these findings into the field. There are limited choices for accessing research findings beyond these two sources. Although we believe the research utilization process is an important and relevant concern and necessary to ensure evidence-based practice in districts, we do not think this is the only explanation. This research is available to the National Policy Boards for Educational Administration (NPBEA) who commission the development of standards for accrediting educational leadership programs as well as professors of educational leadership who are determining the curriculum used to prepare district level leaders. At a minimum, this research should be influencing district effectiveness through the preparation of leaders.

This paper examined three decades of research on district practices associated with school performance and student achievement to gain a better understanding of the utility of the research-base in fostering district improvement in a variety of contexts. We examined the methods, samples, and designs of the effective district research base and to assess the appropriateness of the research base for informing school district policy and practice. Specifically, we explored (1) patterns in the research design by categorizing research types and reporting sampling methods, such as sample size and sample type; (2) patterns of district characteristics in the sample by looking at types of districts, documenting urbanicity, looking at student enrollment, and discussing the socio-economic status of the student population; and (3) patterns of authorship and research productivity by surveying the concentration of authors and determining the proliferation of data sets. Within the following paragraphs we discuss key findings and their implications for research and practice.

Although the literature on school district effectiveness revealed a significant amount of consistency among key findings related to district practices, one of our key concerns was if the findings were generalizable. Given that 50 of the 98 publications in our database employed a qualitative design, we explored whether the findings from these studies could be aggregated. We found that the majority of these studies were conducted in urban districts that were undergoing reform, and that they tended to focus on a narrow band of district practices (e.g., managing and preparing people and the organization and making decisions regarding instructional standards and practices). As such, the results of these studies have the potential to inform the work of like districts around a particular set of findings (Stake, 1995).

Whether findings from these qualitative studies are discussed in sufficient detail to inform district practice, is an important question. Our general assessment is that more research is needed that is specifically designed to provide detailed accounts of the 13 effective practices across a variety of district contexts. The literature reviews of effective district practices included in our database do not describe the district practices in detail, which may suggest that those authors also found the research-base to be lacking sufficient detail. Nonetheless, the practices identified in these reviews have been used often in subsequent research studies and reports as either an organizing framework or misrepresented as evidence of generalizable practices, trends or solutions.

Of the remaining empirical research projects included in our database, nine were quantitative and 21 used mixed-methods. The latter provided the most in-depth evidence in support of the Framework for District Effectiveness, though all 30 used research designs that supported generalization. Like the qualitative studies discussed above, it appears that many of the districts included in the quantitative and mixed methods studies were chosen largely because they were undergoing a reform effort, a selection decision with implications for generalizability. That is, the findings from a study focused on districts undergoing reform, will be more useful to districts in similar situations and less useful for an average district seeking to become more effective. It also raises questions about where the practices of districts undergoing reform should be characterized as “effective.” Similarly, only 13% of the districts in the U.S. are considered urban, yet all but a few of the studies included in our database were conducted in urban districts. Further compounding sampling issues, most of the samples included not only large urban districts but also identified them as high poverty. Urban settings, particularly high poverty districts, differ in significant ways from suburban, small city and rural districts, and the vast majority of school districts in the United States are small and rural.

Additionally, the districts included in the research, whose exact geographic location was mentioned, come from a relatively small portion of states. Thirty-three of the studies' samples included districts from multiple states; however, the database relies on districts from only 60% of the 50 states. Of those 30 states included in the studies, 46 (47%) of the studies come from four states (CA, TX, IL, NY). These facts, complicated by the popular use of qualitative methods, further limits the ability to take study findings and recommendations “to scale” by policy makers or district leaders. It also points to the need for district research in non-urban settings.

With regard to sampling, only 10 studies had a sample size over 100 districts and 48 studies (49%) had samples that included less than five districts. Nineteen of the studies were based on data gathered within a single district. Furthermore, very few of the studies collected longitudinal data, with the majority of the studies collecting data for 1–2 years. Within the districts studied, however, data was collected from multiple stakeholder communities and the perspective of school and district leadership was equally and strongly represented within all 98 studies included in this report. By gathering input from school-based and district-based employees and other key stakeholders, the studies were able to demonstrate a degree of consensus concerning the practices supporting district effectiveness.

Taken individually, these research studies, which appear to be methodologically sound, provide helpful insight into the work of the districts that were studied. However, the ability to use this body of literature collectively to inform practice or policy is inhibited by the fact that the studies represent a fairly narrow band of district types and focus on different aspects of district effectiveness. The studies do not cohere strongly as a collective. Two areas with the greatest number of research evidence include “managing and preparing people and the organization” and “making sound decisions regarding instructional standards and practices.” With few exceptions, such Honig's work on boundary spanners, the findings of this research base provide more guidance for future areas of research than for planning, practice or policy.

The contributions that scholars like Honig (2003, 2004a,b, 2006, 2008, 2009a,b) have made to knowledge development in this area is significant, both in terms of their specific research findings but also due to their persistent focus on issues concerning effective district practices. Few scholars come close to contributing the number of empirical publications that Honig has produced thus far on district effectiveness. In fact, there has been thin engagement by the remaining authors with 80% of the authors that either authored or co-authored appearing on only one district effectiveness publication. Yet, their contributions represented half (53/98) of the database. Although the one piece might be a helpful contribution, it raises questions concerning their familiarity with the existing literature and how their work contributes to that work, whether district effectiveness was the original focus of their research, as well as their level of commitment to understanding district effectiveness.

On the other hand, it is also concerning that several authors, who published multiple papers on the topic of district effectiveness used the same dataset for all or most of their publications. The concentration of authors is to be expected, as it provides the field with experts to whom the field can look for insight, when much of the literature from a given author is based on one or two data sets, many of which focus on a narrow band of districts (i.e., urban districts undergoing reform), but it limits the robustness of the literature base.

It is extremely likely that the availability (or lack) of research funding has significantly influenced many of the trends discussed above. First there is limited federal and foundation grant funding available to research district practices, and second, the funding that has been available has been targeted at large urban districts and districts undergoing reform. In the absence of funding, the large number of small-scale qualitative studies isn't surprising.

Although researchers have consistently produced scholarship on district practices over the last 30 years and the consistency of their findings indicate a framework for effective district practice, significant limitations in the methods, samples and designs of this research base reduce its value for guiding practice in the majority of districts. The greatest strength of the research base on district effectiveness is that the findings are most applicable for urban districts undergoing reform, which is an important area of need. Although urban districts represent a small percentage of districts, large, urban districts serve the majority of students in the US, which makes a focus on knowledge development on urban settings an important undertaking. The large districts that were the most frequently studied are also often those most in need. On balance, we still know very little about rural and small districts because these districts are not well represented in the research base. Furthermore, we know little about how district effectiveness changes over time, and what we do know about effective district practices is at a very general level. As noted above, an examination of the research base on effective district practices provides more guidance for future areas of research than for planning, practice, or policy.

Conclusion

When we began this work, we sought an understanding of district effectiveness. We looked to the research base for guidance on how districts support school improvement, and although we did find a commonly agreed upon set of practices associated with effective districts, we also found a number of troubling trends in the research base. Based on our review, we argue that findings from the research base on effective district practices are not generalizable to all contexts. Indeed, one size is not likely to fit all. The lack of representation of the majority of United States' districts in the research base suggests that policy makers and central office staff must be cautious when considering the applicability of research recommendations to their specific district contexts.