94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Water, 11 March 2022

Sec. Water and Human Systems

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2022.834080

This article is part of the Research TopicWater-Gender-Migration: The Complex Nexus and InterlinkagesView all 6 articles

The Haudenosaunee or Six Nations (SN) is a matrilineal society sustained through reciprocal relationships with nature and all creation. Haudenosaunee hold a special relationship and responsibility with water, as it is the first environment of humans. Colonialism attacked Haudenosaunee land, women, children, and traditional ways of life. The Haudenosaunee were displaced from their land and were forced to migrate to a reserve. Colonial and capitalist agendas contaminated water leaving the Six Nations, Canada's most populated reserve, without clean running water and making SN women and children more vulnerable to water insecurity. The Ohneganos, an SN community project, is intersectional, and the intersectionality of health, culture and water identified maternal health as understudied in water insecurity research. Research on Indigenous mental health mainly focused on suicide and substance abuse and ignored the root causes of violent colonial structures and policies such as the Indian Act and residential schools. Our research suggests that gender, migration and water for Indigenous communities must be contextualized with larger violent colonial structures such as environmental racism and epistemic violence. Ohneganos research examines impacts of water insecurity on maternal health and co-developed design and implementation with Six Nations Birthing Center (SNBC). The SNBC's traditional Haudenosaunee health care practices shaped the research, revealing the critical importance of community-led research's efficacy. Haudenosaunee and anthropological research methods are employed to assess the impact of water insecurity on maternal mental health. The co-designed semi-structured interviews highlight the voices of 54 participants consisting of mothers (n = 41), grandparents (n = 10), and midwives (n = 3) of SN. Most participants expressed that the lack of clean water had profound impacts on mental health and had recurring thoughts about the lack of clean water in the SN community. Mental health issues, including depression and anxiety, were reported due to a lack of running water. Despite experiencing water insecurity, Haudenosaunee women demonstrate resiliency through culturally innovative adaptations to their changing environment.

Two-thirds of the world's population faces water scarcity, and more than two billion people live without adequate clean drinking water (WHO, 2017; Young and Miller, 2018; Tallman, 2019). There are well demonstrated adverse effects of water insecurity on human wellbeing, such as diarrheal diseases, dehydration, emotional stress, and physical violence (Wutich, 2009; Hanrahan et al., 2014; Bulled, 2016). Water insecurity is defined as a condition when unreliable, unsafe, and inadequate water jeopardies wellbeing (Weis et al., 2020, p. 65). Water insecurity is particularly a problem for Indigenous peoples. In Canada, the reservoir of the world's largest freshwater bodies, Indigenous communities have been experiencing water insecurity for decades. There are several long-term advisories where an entire generation grew up without access to clean water (Human Rights Watch, 2016). The Canadian government failed yet again to solve water issues in First Nations communities by March 2021, a promise and plan they made in 2015. There was a total of 160 long-term drinking water advisories on public water systems in First Nations communities, and by the fall of 2020, 60 (37.5%) remained in effect in 41 First Nations communities (Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, 2021). As of December 2021, there were still 42 long-term drinking water advisories on public water systems in 30 First Nations communities (Indigenous Service Canada, 2021). Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament (Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, 2021) demonstrated that the Indigenous Service Canada failed to provide necessary support to ensure safe drinking water in Indigenous communities. Six Nations (SN) of the Grand River community, the most populous reserve in Canada, do not have access to clean running water for decades. The Grand River is the water source for the SN community, which gets contaminated by commercial agriculture and landfill runoff along with capitalist development projects and industries. Although the federal government issues no long-term water advisory, SN experiences several boil water advisories (Duignan et al., in press). Most residents of the reserve depend on wells and cisterns that are old and contaminated. Many do not trust the water due to previous contamination and depend on purchasing water. Recent research at SN also reported E. coli and high levels of mercury in the water (Dupont et al., 2014; Baird et al., 2015; Duignan et al., in press).

Research has confirmed that women are most vulnerable to water insecurity (Fleifel et al., 2019; Pouramin et al., 2020; Dickin et al., 2021; Duignan et al., in press). For example, Duignan et al. (in press) demonstrated that Six Nations women faced health and social challenges more than men due to water insecurity. The Postpartum Period is particularly challenging for most women, and it becomes more challenging when there is a lack of clean running water to meet the necessities for mothers and their families. It is one more obstacle that many Six Nations mothers must constantly face. Besides essential hydration, water is critical to keep themselves, their families, and their homes clean. Bringing enough water home to accomplish this task is difficult for many SN families, especially single mothers with limited transportation. Many SN mothers live with a constant fear that child protective services may become involved, with the challenge of keeping children and homes clean adding to the threat. This alone causes immense worry and stress for SN mothers who do their best with limited access to water. SN mothers who bottle-feed require clean drinkable water to prepare powdered or liquid-based formulas as the ready-made formula is much more expensive. Water is essential for feeding their babies. As a result, SN mothers not only worry about running out of formula, but they also worry about running out of water to make the formula.

Water has critical spiritual roles during pregnancy and birth. Six Nations Birthing Center (SNBC) clients often use traditional medicines during postpartum. Clean-out medicines for mothers and babies and a traditional sitz bath are routinely used to aid postpartum healing and recovery. The medicines are boiled in large pots and require large amounts of clean drinking water. For clients with limited access to water, the Indigenous Midwives make the medicines at the center then bring them to the client's home. It is a cumbersome yet critical task for midwives who are already limited by time. A warm cedar bath relieves the mind and comforts the body when a client is emotionally distraught. Keeping a “good mind” during pregnancy is important due to a fundamental traditional belief that the unborn baby can sense and feel everything the mother is experiencing. Therefore, it is critical to clear mothers' minds of negative thoughts, fears, and grief. Many laboring women prefer to labor and even give birth in a warm relaxing bath. Water reduces pain by causing a deep level of relaxation during the birth process. It also reduces perineal tearing due to the improved elasticity of the skin. For women with a history of sexual abuse, this dramatically improves their overall birth experience. The pain and tearing from birth can often trigger past sexual trauma. A traumatic birth experience can cause women to relive past sexual abuse. Reducing those triggers and creating a positive birth experience through use of water can be very therapeutic and healing for women (see NIMMIWG, 2019; Martin-Hill et al., in press a,b). It can even mark the start of their recovery as they reclaim their sexuality and power.

Six Nations' displacement from their land and being confined on a reserve with poor infrastructure and contaminated water sources put them under a severe health threat. Environmentally, reserves were chosen in remote or infrastructurally poor areas. Polluting industries were built beside reserve lands, dumping toxic chemicals in the water (McGregor and Whitaker, 2001; White et al., 2012; Hoover, 2017; Waldron, 2018; Martin-Hill, 2021a), and thus threatening both water, animals and destroying Haudenosaunee food sources. Recent studies with Six Nations demonstrated that climate change is a health threat for people at Six Nations reserve (Deen et al., 2021). Water scarcity and contamination are one of the major factors of migration and forced displacement around the world (Parker et al., 2016; Miletto et al., 2017; Nagabhatla et al., 2020). Colonial policies such as Indian Act and residential schools worked to systematically displace Six Nations from their land and their traditional ways of life. Colonial and capitalist agendas not only contaminated water but undermined women's decision-making authority in their society and diminished their leadership responsibilities impacting their wellbeing. The Haudenosaunee people believe that there is a link between the violence against water and against Indigenous women (NIMMIWG, 2019; Martin-Hill et al., in press a,b). Arsenault (2021) argues that there is a direct link between water insecurity and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). Therefore, it is crucial to understand the impact of water insecurity on Haudenosaunee mothers through “the larger framework of cultural genocide, environmental ecocide, and racialized injustice (Martin-Hill et al., in press a,b).” Keeping that framework in mind, we adopted the concept of “Structural violence” and looked into the colonial history and assimilationist policies to understand the impact of water insecurity on Haudenosaunee mothers' mental health.

Located along the banks of the Grand River, Six Nations has 27,660 band members, 12,892 of whom live on the reserve (Six Nations, 2021; Six Nations of the Grand River Development Corporation, 2021) Six. Six Nations includes all Haudenosaunee Nations, also known as Iroquois (Six Nations, 2021). Originally there were five nations: Mohawk, Onondaga, Seneca, and Oneida; later, Tuscarora joined the Confederacy in 1722 (Barbeau, 1917; Hill, 2017). When the Europeans first encountered the Haudenosaunee, they occupied most of the Great Lakes to Carolina (Barbeau, 1917). Most New York State, Northern Ohio, Pennsylvania, Southern Ontario, and Quebec were part of Haudenosaunee traditional lands (MacDougall, 2005, p. 2-3).

Haudenosaunee means the “people of the Longhouse,” or “the people who build a house” (MacDougall, 2005, p. 2-3, Gonyea, 2014; Hill, 2017). Mohawk or Kanien'kehaka means “People of the Flint,” they are also known as Keepers of the Eastern Doors, “Oneida or Onayotekaono means” People of the Standing Stone, “Onondaga or Onundagaono, means” People of the Hills, “also means” Keepers of the Central Fire “Cayuga or Guyohkohnayoh means” People of the Great Swamp, “Seneca or Onondowahgah means” People of the Great Hill, “also known as” Keepers of the Western Door, “Tuscarora Skaruhreh means” The Shirt wearing people “(Ransom and Ettenger, 2001; Haudenosaunee Guide for Educators, 2009; Hill, 2017). Six Nations upholds their original teachings such as the Creation Story, the Kayaneren'kowa or the Great Law of Peace, the Niyorihwai:ke or Four ceremonies, and Ohenton Kariihwatehkwen or Thanksgiving Address (Hill, 2017). The creation story emphasizes connections between physical and spiritual worlds. Similarly, the Thanksgiving Address and ceremonies highlight the interdependence with all creations. The Great Law of Peace teaches Peace, Power, and Righteousness, emphasizing the importance of Ganikwi:yo or good minds in creating and maintaining Peace (Mann, 1997; Ransom and Ettenger, 2001; Hill, 2017). Like other Indigenous Peoples, Haudenosaunee believe that human wellbeing is achieved by maintaining a balanced and respectful relationship with all beings, including water (Anderson, 2010; McGregor, 2012). They connect the physical world, the Sky world, animals, and plants and maintain a non-hierarchical and sacred relationship with nature.

Haudenosaunee traditionally is a matrilineal society where women, especially clan mothers, are leaders in the society and make decisions about various issues, including war and adoption (Wagner, 2001; Martin-Hill, 2009). They select leaders and chiefs—a right and responsibility established through the Great Law of Peace (Martin-Hill, 2021b; Martin-Hill et al., in press a,b). Female lineage provided the foundation of the political, economic, and social structure of Haudenosaunee (Wagner, 2001). Children are valued and cherished and grow up under the collaborative care of clan mothers. In addition, Haudenosaunee women maintain a special relationship with water—a relationship started with the Sky woman falling into the water on turtles back, creating the Turtle Island (North America) (King, 2007; Hill, 2017). The Sky woman enabled life to flourish by spreading the mud on the turtle's back brought to her by beavers and muskrat from the bottom of the sea. The Earth is mother to Haudenosaunee as it sustains and generates life, and water is considered the “blood line” of the Earth (Cook, 2008). Water, land, and women carry special responsibilities toward upbringing and sustaining future generations. Haudenosaunee women protect and maintain a relationship with the land to protect their family and community. Thus, a profound relationship between women, land, and water is established. “From the bodies of women flows the generations' relationship both to society and the natural world. In this way, our ancestors said the Earth is our mother. In this way, we, as women, are Earth,” stated Katsi Cook to highlight the inseparable relationships between Haudenosaunee women and Earth (Cook, 2008, cited in Goodman, 2018; Martin-Hill et al., in press a,b). Colonial policies and structures attacked all three: women, water, and land.

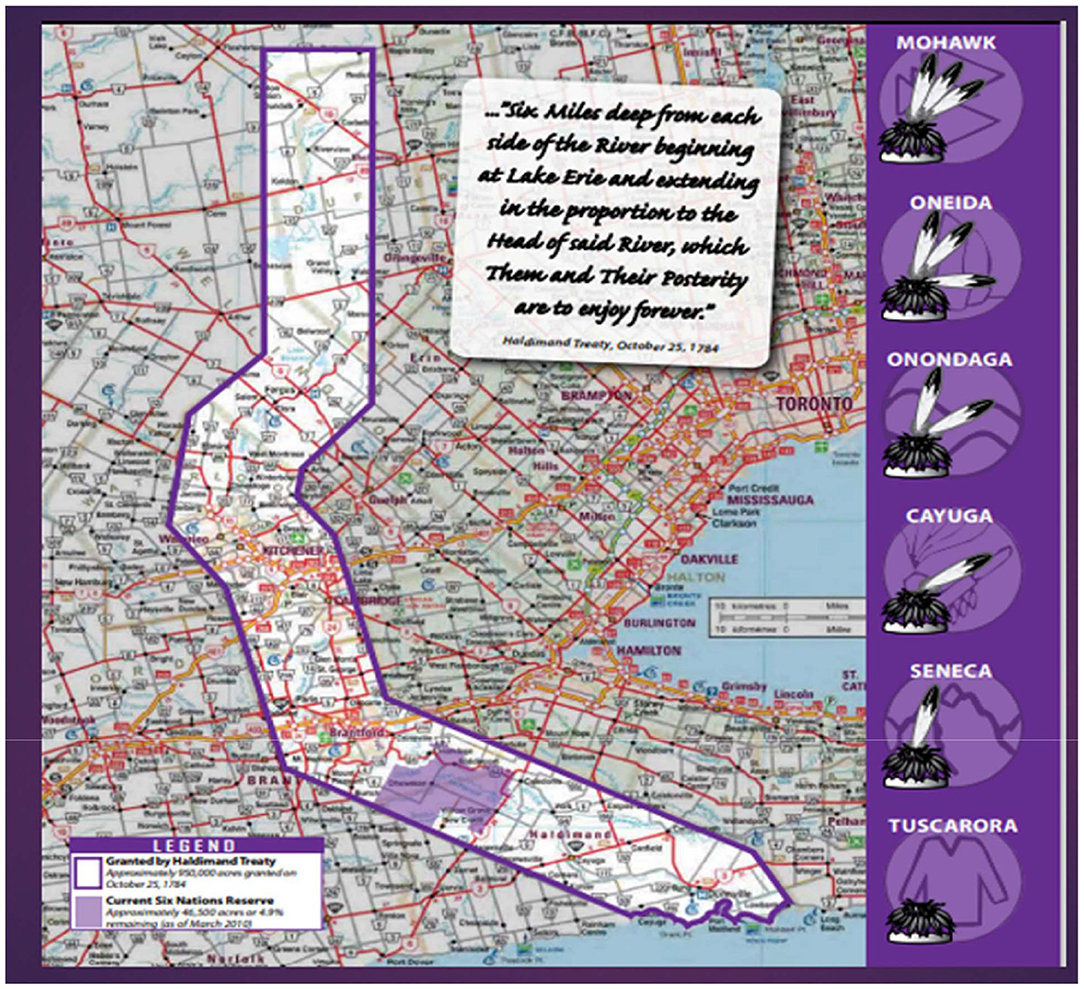

The Haudenosaunee made several treaties with the Europeans. The Kaswentha or the Two-row wampum and the Covenant Chain are notable. These treaties emphasized long-lasting friendship, separate sovereignty, and respecting each other without interference in each others' laws and ways of life (Ransom and Ettenger, 2001; Hill and Coleman, 2019). In the American Revolution, British colonizers broke the treaties and surrendered Haudenosaunee land in the Treaty of Paris without consulting them (McCarthy, 2016; Hill, 2017). As compensation General Frederick Haldimand offered six miles each side along the Grand River, which was 950,000 square kilometers (Six Nations Land Resources, 2008; McCarthy, 2016). Before the Haldimand Proclamation 1784, Six Nations' land right to the Grand River was also acknowledged in many treaties between Haudenosaunee and the Crown, such as the Albany treaty or Beaver Hunting Ground Treaty in 1701 (Hill, 2009; McCarthy, 2016). However, by the early 1800s, settler colonizers disposed of over 600,000 acres of Haudenosaunee land (Hill, 2009:485). Within only 63 years, the settler colonizers grabbed most of their lands and currently, only 4.8 percent of their land is remaining as Six Nations reserve (McCarthy, 2016) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The haldimand tract and six nations reserve. Used with permission from the Six Nations Land and Resources. (https://www.sixnations.ca/department/lands-and-resources).

Continuous displacement of the Haudenosaunee people from their land is still ongoing covertly and overtly. Contamination of water, confining the Haudenosaunee in a land with poor infrastructure and faulty water governance is all example of the structural violence of Haudenosaunee displacement. The 1492 Land Back Lane protest is a recent example of continuous land encroachment by settler colonizers, where without consulting with the Six Nations, 132 acres of Six Nations land in Caledonia was given to a housing development, the Douglas Creek Estates, to establish housing units which were hugely protested by Six Nations in 2006 and again in 2020 (McCarthy, 2016; Barrea, 2020).

This research is a part of Ohneganos - Indigenous Ecological Knowledge, Training, and Co-Creation of Mixed-Method Tools funded thorough the Global Water Futures (GWF). Ethics approval was obtained from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (HiREB) and the Six Nations Council Research Ethics Committee (SNCREC). Ohneganos research project adopted and applied Haudenosaunee traditional ecological knowledge and western science to co-create water quality tools and mixed methods tools designed with the Six Nations community (Martin-Hill et al., in press a,b). Ohneganos project emphasized “gender-nature” linkages where Haudenosaunee women played leadership roles from project conception to dissemination. Ohneganos' overarching goal has been to decolonize and co-develop innovative research methods. Reciprocity has been an important aspect, so both the community knowledge and science are mutually exchanged. Ohneganos promoted partnership with the Six Nations Birthing Center as humans' first environment is in water inside mothers' wombs (Cook, 2008; Goodman, 2018). In this research, we assess maternal health in relation to water, adopting Kaswenta or Two-Row Wampum principles in Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR). The Tow-Row Wampum treaty was established between the Haudenosaunee and the Europeans (Dutch). The Two-Row Wampum allows for creating a dialogical space across epistemologies by promoting equality and accepting heterogeneity (Hill and Coleman, 2019; Goodchild et al., 20211. The Six Nations Birthing Center (SNBC) led the research from the very conception and guided the research through unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic situations by administering phone interviews and midwife chart analysis. We utilized co-created semi-structured interview guidelines with Haudenosaunee story-telling methods. We listened to experiences and stories related to water from 41 mothers (age 19 to 51) who are clients of the SNBC, 3 midwives (age 34 to 65) trained in both Haudenosaunee and western medical models who work at the SNBC, and 10 grandparents (age 61 to 88) who volunteer as consultants at the SNBC to guide mothers through their traditional teachings and activities. Although, with the help of the midwives, we gathered quantitative data from all 41 clients to further assess the impact of water insecurity on mothers' health, only qualitative data related to mental health and water from 54 participants are utilized in this article.

All interviews were conducted, and tape recorded by SNBC maternity care worker, Janet Homer, who has established a relationship of trust with SNBC clients. The questions related to water quality, water uses, relationship between maternal health and water were asked. The First author transcribed all recorded interviews using qualitative data analyzing software NVivo. The first author then replayed and listened to the recorded interviews several times to rectify any mistakes that the software could not correct and ensure the participants' tone was honored in the transcriptions. The data were analyzed both manually and utilizing NVivo. All data were shared with the community partners for cross-validation. The community partner and the first author went back and forth to manually code major themes from the interviews. The interview data was also inputted in the NVivo to identify concepts and patterns and build analytical models. All related data were categorized under main themes identified with community partner such as the mental impact of water, emotional impact, and water quality in the SN community. The first author then reread the categorized data under each theme to validate and manually code the frequency for further analysis. We utilized critical medical anthropology and Indigenous scholarships to analyze our data.

Indigenous communities in Canada have large numbers of boil water advisories, have been experiencing a lack of clean drinking water in their communities for decades, and experience poor health with double the mental health issues of non-Indigenous people (Kirmayer et al., 2000; Khan, 2008; Nelson and Wilson, 2017). To understand why, we must understand violent structures of ongoing colonialism in Canada. The concept of structural violence was developed by sociologist Galtung (1969) and adapted in anthropology by physician and medical anthropologist, Farmer (1996, 2004). Farmer (2004) argued that violence built-into social, political, and economic structures is the root cause underlying the fact that the poor and marginalized are always the victims of avoidable illness and death and suffer the most. Anthropology as a discipline also served colonial agendas and contributed to the structural violence for Indigenous and non-western peoples (Clair, 2003; McCarthy, 2008). Indigenous scholars also argue that understanding maternal health issues would be incomplete without understanding colonial structural violence and colonial assimilationist policies (Mann, 2018; Martin-Hill et al., in press a,b).

Although we adopt the concept of structural violence, we move away from Farmer's deterministic conception as it implies universalism and fails to show how marginalized people participate, resist, and make meaning in the face of violent structures (Bourgois and Scheper-Hughes, 2004; Hannig, 2017). Farmer (2004) did not want to recognize Indigenous and marginalized people's resistance in shaping social structures as he considered them fruitless. However, research shows that people at the margin shape and impact the center; therefore, considering marginalized people's resistance and resilience is vital to understand the interplay between center and periphery (Das and Poole, 2004). Humans are not passive recipients of violence; humans are both resilient and fragile, and therefore a balanced study of both human vulnerability and resiliency is crucial (Scheper-Hughes, 2008).

Although many scholars from different disciplines have adapted the concept of resilience to understand the strengths in opposition to vulnerabilities, it is a prevalent and contested concept. Understanding resilience as bouncing back to the previous condition has been criticized, and instead, many proposed to see resilience as a process that encourages thriving through adversity (Kirmayer et al., 2009; Ungar, 2012; Barrios, 2014; Hansen, 2016). Researchers have argued that resilience is not just an individual capacity but can be found in family, culture and community (Stout and Kipling, 2003; Fleming and Ledogar, 2008; Kirmayer et al., 2009). In health research, resilience has been an important concept to look beyond metanarratives such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). For example, Scheper-Hughes (2008) demonstrates that people insist on their right to live even in a most challenging time. She demonstrated that people adopt different resilience strategies to cope with adversaries, such as humor. She calls them “everyday resilience” (Scheper-Hughes, 2008, p. 52). However, others have been more critical in using the concept of resilience. For example, Chandler (2014) argues that resilience is a form of neoliberal governmentality that enables and extends bio-political rules. Similarly, Barrios (2014) argues that the concept of resilience depoliticizes highly politicized things. Resilience theory's depoliticized nature erases the historical process that produces disaster and vulnerability (Barrios, 2014). As such, Barrios (2014) recommends that resilience must be polyvocal. It should also emphasize local knowledge and should not be a subject of neoliberal ideology.

Despite ongoing colonialism and continuous marginalization, Indigenous communities in Canada strived and did well (Kirmayer et al., 2009; Noronha et al., 2021). Indigenous resilience is land-based and rooted in traditional philosophies and cultures. Indigenous peoples focused on resiliency in youth for centuries and cherished them in various ways (Stout and Kipling, 2003). Community involvement in child-rearing, respect for age, wisdom and tradition, nature, generosity, cooperation, and patience are essential in nurturing resilience (Stout and Kipling, 2003, p. 23). The Haudenosaunee have upheld their traditions and teachings despite the ongoing colonial pressure of acculturation and assimilation (Shimony, 1994; Noronha et al., 2021). Kirmayer et al. (2009) demonstrated that availability and accessibility of several protective factors such as family, community, language, cultural identity, improved infrastructure with local control are crucial for Indigenous resiliency. According to Luthar et al. (2000), resilience factors can function in a number of ways: they can maintain a child's functioning under stress, protecting them as stress increases. A protective factor may also interact with stressors to create growth in a child exposed to adversity. The protective factors help maintain normative levels of competence in children exposed to multiple risks. Positive relationships with adults, mentors, and stable school environments also work as strong resilience factors (Lipman et al., 2002; Stout and Kipling, 2003). However, like Kirmayer et al. (2009) we also argue that impact of structural violence is crucial in understanding Indigenous resilience. In this paper, we focus on both structural violence and resilience to have a balanced analysis of the impact of water insecurity on maternal mental health.

In this section we draw from our ethnographic data (54 semi-structured interviews) to highlight the complex ways water insecurity affects Six Nations mothers' mental and emotional health. In our research, participants understood mental health not as an absence of illness but in relation to fundamental human rights such as water, food, shelter, access to land and water, access to traditional medicines, and raising kids with Haudenosaunee teachings. Further, mental health was understood with the ability of fulfilling their roles in raising kids as mothers and grandmothers, which resonates with Anderson (2011) findings. Anderson (2011) argued that health in Indigenous communities means carrying on responsibilities in various life stages.

Onkwehon:we (the original people) are at more risk than others because of their traditional relationship with water and living under ongoing colonization. Participants find that not having access to water affects their mental and emotional health more than others.

“Everybody should have a right to have clean water. So, knowing that just because you're a Native and you live on the reserve, and it's not [affects mental health].”

Participants mentioned that as Onkwehon:we, water insecurity put them at additional risks. To understand this statement, we need to understand Onkwehon:we people in the context of settler colonialism where residential school experiences, child welfare, missing and murdered Indigenous women, and land back struggles all take a mental toll on Indigenous people in general and Onkwehon:we /Haudenosaunee people in particular. Not giving access to water to Six Nations means further exercising continuous settler-colonial power and continuing dominations, discrimination, inequality, and demolishing traditional relationships with water and land. It could be read as a contemporary way of “killing an Indian in a child” by disrupting their traditional ways of living, creating barriers to be traditionally connected with water and ceremonies, and denying basic human rights—they all add to stress. As one participant explained:

“Mental health is a really big thing because a lot of people struggle with it within our community.” “[As] Onkwehon:we people, we already are at such high risk for mental health. And why not just add another thing to not clean water, you know? Water is a big gift given to us, and we don't have access [to it]. And I think it really affects your mind because you need water… and people take that for granted. [So] it truly affects your mental health because it's like, what can I really do? It is just the way it is and this makes me sad.”

Further, participants find that living in different water realities than their neighboring cities distinctively affects their mental health. Six Nations do not have access to clean drinking water on the reserve as their neighboring cities have. A water treatment plant was established in 2014, but only 12% of households are attached to the waterline (Public Works Report, 2019, cited in Martin-Hill et al., in press a,b). As a result, most people need to buy water for drinking and other daily uses. They believe tap water puts them at risk of various diseases such as skin rashes and even cancer. The Human Right Watch (2016) study that included Six Nations with other Indigenous communities in Ontario found cancer-causing Trihalomethanes and E. coli in their water.

Moreover, the struggle for ensuring access to clean water, which should be “basic human rights,” has been ongoing for decades in Six Nations so much so that many participants did not know if the water situation will be solved in their lifetimes or if their children and grandchildren will have access to clean water, water that city dwellers seem to take “for granted.” Water seems abundant in nearby cities where “you can turn on your tap for drinking water.” This reality of the cities came as a “cultural shock” to one client and felt “strange” by other clients. One participant stated that not having access to clean water affects both mothers' and babies' health in general and that people can be depressed, angry and even spiteful living in different realities with neighboring cities where residents do not have to stress out about the water. Participants pointed out that raising kids without water affect mothers' mental health:

“I think the poor quality of water would affect your mental health by just feeling frustrated that you're not able to have running water the same as other communities…[it] makes your life harder and causes more stress trying to raise your family without having running water. It would just constantly weigh on you mentally and cause more physical work for you at the end of each day.”

In a similar vein, a participant describes how not having running water adds extra stress to their already stressful life:

“It's whole different stress you know! Everybody has their daily stressors say, did I make enough supper for tonight or you know! But I think that having that additional stressor water…[which] is so essential to living can take a toll on your mental health for sure, to have an extra load that other people don't have to think about.”

It affects mental health and builds 'mom guilt,' leading to postpartum depression, stated a participant. A study in Nepal demonstrated a link between water insecurity and postnatal depression, arguing that worries, anxiety, and stress over clean water led to postpartum depression (Aihara et al., 2016). Although no link between water insecurity and postpartum depression among Indigenous women was investigated yet, research demonstrated that postpartum depression (PPD) and antenatal depression are higher in Indigenous women than non-Indigenous women in Canada (Bowen et al., 2008; Daoud et al., 2019).

However, despite the long struggle for clean water, one client thought Six Nations are in a better position and “one of the more fortunate one” than other Indigenous reserves in Canada struggling for clean drinking water.

“I've seen pictures on Facebook of that one reserve where they had no access to water and when they did turn the water on, and it was just brown. It just made me so sad. And I just feel like if I had water like that, I would feel depressed. I would feel very upset that not only is this what I'm drinking, but this is the water that I have to give to my children.”

In addition, participants believe that contamination and water insecurity affect them more due to their special relationship with water. Haudenosaunee people hold a special relationship with water from their creation story to pregnancy and childbirth and ceremonies. There is a sacred relationship between women and water. Therefore, not having access to clean water affects them much deeper than others. Other studies that focused on women and water insecurity found that women are more susceptible to water insecurity since they value water more (Baird et al., 2015). In a similar vein, Deonandan and Bell (2019) argued that since Indigenous women play crucial roles and responsibilities, environmental contamination affects them the most. Recent research with the SN community demonstrates that women are more concerned and anxious about water access and quality than men and that Six Nations women felt anger, frustrations and worries for not having access to clean drinking water (Duignan et al., in press; Martin-Hill et al., in press a,b). Some participants find water used for amusement in nearby cities, such as splash pads, is both wasteful and disrespectful to water. On the contrary, water in Haudenosaunee worldviews is given utmost respect through their Thanksgiving address and ceremonies and treated as medicine. And contaminated water, paradoxically, means both not being able to use it as medicine and being sick ingesting it. Further, food preparations in ceremonies become stressful due to lack of clean running water:

“…one of the big things in every ceremony like do we have water? do we have water to make corn mush, to make the soup, the strawberry juice? Those are, I guess I will say, the staple dishes of ceremony that you have to prepare on when it's your responsibility to prepare ceremony. And, you know, our Longhouse doesn't have running water. Like we have to carry jugs of water to our cookhouse every ceremony to make sure that they are there. Like that cost can build if you do not already have jugs. People were constantly donating money just for water… And not just any water, but the water that's for cooking, for drinking for the people so that ceremony can happen.”

Not having clean running water adds to the physical, financial, spiritual, and mental burden. What follows is a detailed discussion of how water insecurity affects SN mothers' mental health and their survival strategies or coping mechanisms with water insecurity.

Research that focused on the mental health of Indigenous and non-western women found stress, anxiety, and depression are most prevalent among women (Wutich and Ragsdale, 2008; Stevenson et al., 2016; Collins et al., 2019; Duignan et al., in press). Collins et al. (2019) reported severe stress related to water insecurity among pregnant and postpartum women in Kenya. Similarly, in our research, stress and anxiety were reported the most as the mental health impact of water insecurity. Not having clean water to drink, cook, and bathe negatively affects mental health, stated most participants.

“The thought of how I am gonna get the water…can be stressful… And we ran out [of water] one time, and it was really stressful just not to be able to really do anything, no bath or dishes. This causes stress and anxiety.”

Another participant explained that not having clean water makes her “motherlike stressed,” she stated,

“It is stressful not to have clean water or to run out of water. If we are trying to raise a family and we don't have those basic things that we need, then it becomes stressful, and it can cause anxiety.”

A grandmother echoed the same, stating,

“Just not even having good drinking water when your kids are little, and not being able to give them good drinking water, then it's going to affect you mentally because you can't give it to your kids.”

To the participants, this inaccessibility of clean water adds extra problems to Six Nations people on the reserve, especially mothers, which could be easily avoided. It could be read as structural violence that puts people in harm's way and causes avoidable disease, illness, and death (Farmer, 2004).

Water-related anxiety and stress were even higher when the province went to complete lock-down in March 2020, causing bottled water supply to be limited in the stores. While the toilet paper shortage for larger communities was highlighted in local and national newspapers, Indigenous communities like Six Nations were worried about water supplies. It also affirms different realities for Six Nations and its neighboring cities during the pandemic. The rhetoric of political parties, “we are all in this together,” remains shallow as it failed to capture different situations for Six Nations and other Indigenous peoples without clean water. Advice to frequently wash hands with soap and water comes as a joke for people without access to clean water. Six Nations mothers had to use more water to be as hygienic as possible during the pandemic. Not only do they have to make more trips to stores and spend extra money to get drinking water during the pandemic, but they also worry if there would be enough water to buy since water cases were sold within the limit. Participants who truck in their water often wait for days for the truck to come due to pandemics. These realities forced many participants to limit bathing and limit the amount and frequency of drinking water. A mother said when bottled water was on limit, she was anxious thinking,

“Is there going to be enough water [to buy] when we go to the store? We can get only one case today, but you know we'll have to make it last. So, then everybody is limiting themselves.”

Realities were not the same in the pandemic living in the same country despite politicians saying, “we all are in the same boat” Indigenous people's boat was different since they were still struggling to get a hold of water supplies. In addition to not socializing with extended family and community, participants reported that not having enough water was an essential thing that mothers and families in Six Nations had to worry about during COVID-19 pandemic.

Not having enough water forces people to limit their water intake, eventually causing them to be dehydrated and drained. Using tap water to cook and drink can make people “nauseous, sluggish, or irritable because of the chemicals that are put into the water or in their wells,” said one participant. A grandparent was concerned that not having clean water affects traditional upbringing, which holds a close relationship with water, as poor quality and contaminated water make them anxious and worried.

“I can't look after my grandchildren the way I know I'm supposed to with our medicine. I can't take them to more water areas and be sure of their safety because who knows what's in there, right?”

“Who knows what's in there” is expressed by several other participants. In this research, we learned that many could not fully trust the water they have even if they are connected to water line coming from the water treatment plant because they find the water “hard,” “smells strange,” or smells like chlorine or sulfur, and sometimes has an “odd color.” Also, participants reported that the source water, the Grand River, has “all the garbage” in it, and “all the chemicals are used to make the water look good” make them suspicious about the water quality. According to a grandmother, the nutrients in the water get destroyed by dumping garbage in the water and treating water to make it drinkable. She worried:

“It [water] doesn't have the nutrients that are actually in the water because water has nutrients in it, so with all the garbage that's in the water, like how can you know, how can that be healthy for anybody to drink?”

Another grandmother thought the same way and believed that something in the water causes short-term memory loss. That contaminated water or not having enough clean drinking water can cause short-term memory loss also supported by the Harvard School of Public Health (2021).

“…who knows what's in there, what is hidden in the water? I think a lot of times that's what causes short term memory loss… we don't have the best water here anymore like we used to, so things like that get a hold of their brain, and we don't know what it's doing to it,” said the grandmother.

Participants reported that not having access to clean water can affect clear thinking, as not having clean water to drink makes people dependent on “sugary” drinks, which cause diseases like diabetes, but it also affects clear thinking. “If you're consuming so much sugar and not having enough water, I think that affects your mind, not just your [physical] body [but] your whole body, like your mind, body, and spirit,” said a participant. Another client echoed the same, “you're probably not going to be able to think properly if your body is struggling to regulate itself, and that's what water does. It regulates your body, regulates your hormones. [If] you're not intaking a good quality of water, your mind is going to struggle. It's going to struggle to think clearly.” Similarly, according to another participant: “water that has something in it that shouldn't be, or you get too much of something that your body doesn't need with contaminations, then it can affect your mental abilities even just to think clearly.” To other clients, contaminated water poisons bodies and thus affects clear thinking. For some participants, contaminated water and water without proper nutrients can block clear thinking and interrupt connections with self and others:

“[If] we're drinking [contaminated] water, we're not going to see one hundred percent. We're not going to be happy one hundred percent; we're not going to be able to think clearly one hundred percent. We're not going to be connected the way we should with our body because our bodies are being poisoned, really.”

A grandmother shared the same and thinks not drinking enough water makes people forgetful. She shared her husband's experience who does not like to drink enough water,

“I don't know why he won't drink water. He will, once in a while. It seems like he doesn't remember things, or he gets forgetful, and I think it's because of that. I told him you gotta lubricate everything, you know, that way things start working in your body.”

Participants reported that added financial burden to access clean water affects mental health. They buy water to drink and fill in their cisterns and wells for other daily uses. As a result, they have to save and spend extra money on water which should be “available to all.” This avoidable financial burden that Six Nations are forced to pay affects their mental health. However, this extra cost for water is not affordable for many. As one participant client asked,

“What about those who are on welfare that doesn't have jobs or on disability and can't work? Where are they going to find the money? Because they're just barely getting by as it is, but now they need to go buy water on the side. How are they going to get the money for that? And who's going to help them if they can't get it? So that's very tampering.”

For Six Nations people, getting clean water is going the extra mile, both literally and financially. Traveling the distance to buy bottled water, arranging transport, and paying for gas add to the financial burden and ultimately affect mental health. To a client: “having to go extra mile to get clean water, you know, can be pretty tiring on you.”

Along with the financial burden, not having a support system to help access water causes anxiety. As one participant client shared her moments of anxiety:

“We have access to water in terms of drinking and cooking, but we have to truck our water to our house. You know, sometimes there's financial, sometimes it's an emotional barrier. My dad trucks our water and dumps it into our well, but he goes moose hunting like he's about to go moose hunting for 2 weeks. And you know if I run out of water while he's gone, that automatically I have to pay 80 dollars for somebody to conceal my well for me. And so there's always like you're constantly trying to make sure that you have enough for what you need it for you, and that can become a burden for me when I have a toddler, and I can't just go and truck water for myself using my dad's truck, right? So those kinds of things like for me is… mental and financial barriers when it comes to access to clean water.”

Further, not having access to clean water often impacts hygiene practices and affects confidence in public places, including Longhouses and schools. Participants mentioned how having a bath or doing laundry is not an option for many. According to a client, “a lot of people can't even save the money to do laundry, so showering sometimes is just beyond that person.” In addition, many people depend on other family members' houses for a shower, “it's the whole point of insecurity for a lot of people,” stated a client. A midwife of the Birthing Center confirmed the same for some of their clients' situations:

“…they might be struggling with even being able to have clean clothes, with being able to take a shower or to wash up, even washing their hands. They come in [at the Birthing Center]. They'll wash their hands really good because they don't even have water at home to do that.”

She helps client mothers by offering them to take a shower so that mothers feel better:

“On occasion, I've even let people take a shower [at SNBC], especially if they're at a birth…' Why don't you take a shower before you leave,' you know, like that kind of thing as well. And it makes a big difference for them. And they smile a lot bigger, and they feel a little bit more relaxed.” She concludes, “It's just a simple, basic thing, but it's something that's being robbed of our people.”

In total, 78% (n = 32) clients and 100 % grandparents (n = 10) think that water insecurity can affect emotional health along with mental health. They indeed think mental and emotional health goes “hand in hand.” However, more than 4% (n = 2) of clients did not think water could affect emotional health, and 17% (n = 7) of clients were unsure about the connection between water and emotional health. Clients who thought water affected emotional health reported themselves and their children being sad, upset, depressed, worried, and anxious. Emotional and mental health are connected and entangled. As one client said: “the emotional and mental health go hand in hand if one is off, the other one is going to be affected by it as well.”

Not having access to something as essential as water that should be considered human rights and available to everyone causes anxiety. Not just being able to provide water to their children affects mothers' emotional health. They get upset and worried about raising kids without clean running water.

“Just feeling like you can't provide something that is so common in other houses to your family. Just feeling like you can't provide for your children what they deserve and what is completely normal for everybody else [causes anxiety],” shared a mother.

Similarly, another mother shared,

“I would be sad, and I would feel really guilty and angry as well [that] I couldn't provide these what I consider to be basic needs, so emotionally it would cause a big strain.”

Many participants truck in their water, and if the water truck does not come as scheduled, that could force them to limit their water uses and causes anxiety: “if we are running low and the truck can't come for few days, it can be hard. It's like we have to really limit how much we are using. You know, it's hard to go to work…[if] you didn't get to have a good shower. It causes anxiety.” One client reported waiting as many as ten days before the water got trucked in. She could not shower for these ten days affecting her physical hygiene and mental health.

Some participants who had clean running water from the water treatment plant worried about their other family members, relatives, and community who do not have access to clean running water and are forced to use the water they cannot trust. For example, a participant with running water shared her worries about her mother using well water that she thinks could be contaminated: “this really shouldn't be a worry to have access to clean water, not when everybody else around us enjoys it abundantly.” Another participant explained that emotional wellbeing gets severely affected by “just having to go through this, you know, when I couldn't afford water. Like, we had to go without [water], and that was very emotionally stressful.”

To some participants, water is a source of emotional wellness, and if they do not get access to that water, their mental wellbeing gets negatively affected. When water is contaminated, polluted, scarce, limited and not trustworthy, it affects Haudenosaunee's traditional connections with water and affects emotional health. The connection with self and others and land and water gets disturbed. “If we're not feeling hundred percent, then we are not able to connect with our bodies a hundred percent, there is no way we will connect with people around us a hundred percent,” described a participant. A grandmother was worried about all the chemicals that are put in the water because “it changes the molecules in our bodies, you know, so you're more emotional; you get depressed,” she continues, “because they're not the natural order of the earth; they're affecting everything about us, our mental or emotional, our physical and our spiritual.”

Not only mothers, but the poor quality of water and not having enough clean water affects children's emotions. For example, a mother shared how being able to wash his face in the morning with fresh water makes a significant difference in her son's emotions:

“Simple bowl of water to wash your face in the morning really refreshes you! My boy has a lot of mental health issues. He suffers from depression, and he has these other issues going on with him, but if you don't use that water daily on his face, his body, he's in the emotional ride. I can see how the water can refresh him. He feels pretty good.”

Another client thinks there is a relationship between a teenage girl who is angry and does not have running water. A grandmother shared that looking at the contaminated water at the Grand River not only makes her upset that she could not raise her grandchildren in the environment she wants to, but the water in the Grand River makes her granddaughter sad for the fish and turtles.

“I feel bad for my grandchildren,” the grandmother said, “'cause they are growing up in a time where my granddaughter looked at the river [and] we have brown water. [I said] I never wanna eat anything from there. And then she was saying 'if it's not good for us, then what about those turtles?' so she thought about the turtles and the fish in there, she was sad!” she continues, “her childhood experience should be happy, right?” Not being able to raise grandchildren in the environment that she grew up with the connection to the environment that is healthy worries this grandmother. “That's how I grew up, as I was always taught to be connected to the environment. So that's what I try to provide, and then the environment is dying! So, you know, the emotional base, a positive base that she should have, isn't there!”

Despite the negative impact of water insecurity on mental health, Haudenosaunee women demonstrate resiliency and adopt various culturally innovative coping strategies in times of very limited to no access to clean water and to sustain good mental health. These strategies include rejuvenating their relationship with water, having family and communal support, and planning better. Research that focused on coping mechanisms in times of water insecurity also demonstrated that planning ahead of time, water sharing with neighbors and relatives, and having a strong family and community support have been effective coping mechanisms (Hanrahan et al., 2014; Brews et al., 2019).

While not having clean water made SN mothers stressed, depressed, and anxious, water is the place for many to go to relieve those stresses and anxieties and to heal. Going to the water to revive mental health has been significant for many participants.

“I grew up going down to the river. Anytime I was mad or sad…I would go to the river and let it wash that away. Wash the angry away. Wash that sad away.”

Many participants found water calming and helpful with mental health. As one participant shared how water helps them feel better and feel connected:

“I know a lot of people find going even to the ocean or to the Grand River is very calming. Like my husband, I can kind of understand why he loves to fish all the time because he says it's so peaceful and it is. And we're all together, and water is healing because if we're having a bad day, usually he says, oh, let's just go down to the river and we'll take the girls, and we'll have some fun and I think if that wasn't accessible, I would just feel like I'm almost trapped like you have no outlet to let things go… sitting near of the Grand River would just be so calming where if you needed that moment to reconnect yourself and to get in touch with your feelings, that would be the place to do it.”

In addition, participants find that having a support system within the family, community, and society ensures good mental health. “The stress of, like, just the way that we live our lives now and the hassle that affects our mental wellbeing… but it's so important to have community and a support system in times of stress,” said one participant. Participants mentioned extended family support to cope with limited or no access to water. For example, being able to use the kitchen or shower or laundry with other family members or having someone to buy water for the families who cannot or do not have transportation were mentioned as coping mechanisms.

Constant planning about water and water uses help them cope with limited water. “Well, you're constantly planning and trying to figure out that anxiety, your brain is just always in overdrive, trying to make sure that you have it [water] or that if you do not have it[water] which way that I can use it.” Stated one mother. Limiting bath and laundry, stocking up on water, giving kids the priority of water are some of the strategies mentioned by SN mothers.

One client said she must even plan her garden based on its need for water, “I have to consider how I can water the garden, how big of a garden, what kind of plant can I plant!” Another client said she even plans her stops and water uses on the road or going for a walk, “if I start to have a drink, where am I going to get more (laughter),” she adds, “you learn asking if you take a shower or save up money.”

A grandparent said collecting maple water is a way of planning too, “that's why they talk about these maple trees… when you tap those trees that supposed to be our water. That's one of the pure water sources, and that's why they always said that you collect that when it's that time of the year and because you don't know what's going to happen to the rest of our waters.”

Different programmes were mentioned as supporting mothers to ensure good maternal and mental health. Many expressed their satisfaction with the services provided by the Six Nations Birthing Center, especially when it comes to mental health, as their services are extended beyond births. Programs such as Mom and Tots and Childminding were mentioned to be helpful to care for mental health. Being able to be learning crafts with other moms while their children are being taken care of by the Birthing Center staff is considered necessary. “Just sit down and do something with other women…is critical or central to my mental health. Sometimes it is enough for you to know that you are not alone in terms of caring for your wellbeing and that of your child,” said one client participant. Some mentioned “mommy fitness” classes at Stoneridge daycare, which offers childcare when mothers can work out and feel physically and mentally sound. Some found programmes that teach participants to prepare and cook food for babies helpful for their mental health. The Six Nations Elected Council free water delivery during the pandemic proved to be a stress reducer for many participants who accessed it.

Ethnographic data on water insecurity and maternal mental health revealed three major points: (1), maternal mental health is holistic which is understood in relation to family, community, land, and water. (2) maternal mental health and water insecurity were contextualized in ongoing violent colonial structures; and (3) despite ongoing colonialism and severe water insecurity, Haudenosaunee mothers demonstrated resiliency by adopting various cultural strategies inspired by their traditional teachings.

Water insecurity profoundly affected SN mothers' mental health because of their holistic understanding of mental health and their traditional relationship with water. Ethnographic data reveals that, unlike western concepts, mental health was not understood as the mere absence of illness; instead, it was entangled with the health of family, community, environment, and water. Good mental health is defined by the absence of illness in the western concept, which is compartmentalized, individualistic, and inadequate to understand Indigenous mental health issues (Cardona et al., 2021). Conventional western knowledge reduced Indigenous mental health as 'problems' and often categorized Indigenous people as helpless, vulnerable, and passive (Kelm, 1998; Scheper-Hughes, 2008, p. 52; Simpson, 2008). In the name of managing mental health “problems” such as stress, depression, and PTSD, the conventional western methods perpetuated racism and discrimination and contributed to violent colonial structures (Kelm, 1998; Kirmayer et al., 2007; Stevenson, 2014). Academics played vital roles in constructing Indigenous people as pathologic, disordered, alcoholic, and vulnerable (Kelm, 1998; Waldram, 2004; Waldram et al., 2006). Recent research by critical medical anthropologists and Indigenous scholars has questioned the individualistic and universalistic understanding of mental health and demonstrated that mental health has various meanings in different cultures. These works have highlighted the importance of contextualizing illness and health in broader social, historical, economic, political, and colonial structures (Singer, 1989; Farmer, 1996, 2004; Farmer et al., 2006; Lavallee and Pool, 2009). In Indigenous societies, mental health is a part of holistic health and is interconnected with the natural environment and all creation (Martin-Hill, 2009; Howell et al., 2016; Freeman, 2019). For Haudenosaunee, mental health is embedded in their notion of Ganikwi: yo or good mind established in the Great Law of Peace. A good mind is achieved through living in peace, balance, and harmony with all creation (Noronha et al., 2021). Noronha et al. (2021) adapted the Haudenosaunee wellness model collected from the Kawenni:io/Gaweni:yo private school to demonstrate that for Haudenosaunee, both good mental health and resilience depend on a good mind, family, community, environment, and spirituality. Further, they demonstrated that mental health issues such as stress, anxiety, and depression are not universal, nor are their healings; instead, they vary in different cultures (Kleinman and Good, 1986; Kelm, 1998; Adelson, 2005). For example, spirit possession that could be understood in various medical terms such as schizophrenia or epilepsy is not pathology rather valued in many cultures (Fadiman, 1997; Seligman, 2005). Similarly, depression in Mohawk is Wake'nikonhrèn:ton, meaning “a mind spread out in the ground” describing a situation of mind and body disembodiment (Elloitt, 2019). It does not pathologize but expresses a particular situation in individuals.

Studies reported higher psychological distress in people living on-reserve (FNIGC, 2012). This is due to personal and interpersonal trauma (family violence, sexual exploitation), compounded by community trauma (intergenerational trauma), and the challenges of environmental stewardship responsibilities. For example, suicide rates increase with heightened anxiety concerning the impacts of climate change (Burke et al., 2018). Indigenous women, in particular, are at increased risk of mental health issues such as depression and anxiety (Oawis et al., 2020). Our research reveals that stress and anxiety are liked to water insecurity, as water insecurity causes financial burden, affects self-hygiene and self-esteem, and negatively impacts raising family and children. Western solutions have failed to meet the needs of Indigenous populations: the majority (72.3%) of FN youth do not utilize mental health services, with no differences between genders (FNIGC, 2012). The western individualistic healing approach that seeks to treat individuals outside of their family, community, and society has proven ineffective to Indigenous people (Kirmayer et al., 2000; Freeman, 2019). Research demonstrated that mental health for Indigenous people is better ensured within the context of community and family support and when seen holistically (Kirmayer et al., 2000; Martin-Hill, 2009). However, the holistic meaning may not be mutually understood. Our research shows that the sense of holism goes beyond physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual domains. In addition to ongoing colonialism, we, therefore, argue that mental health must be understood in connection to land, water, and the environment, as natural disasters, including water contamination, are symptoms of colonialism, western development policies, and structural violence (Barrios, 2014). Our participants described their water as “sick” and “unwell,” which made them sad and frustrated about themselves and about all the animals that live in and depend on the water. Research in non-western and Indigenous societies also demonstrated that people believe they are related to nature or the ocean and that their personal illness is just a reflection of what is happening in their environment, land, and water (Andrews, 2020). Both sufferings and healing for these participants then get interweaved with the suffering and healing of the water.

Mental health and water insecurity and their relationship were understood in the broader historical and colonial context, racist policies, and violent and unequal social structure. Water insecurity was understood as violence of basic human rights. SN mothers linked their mental health with land degradation, water contamination, loss of traditional knowledge and medicines, and traditional upbringing of children caused by colonial assimilationist policies such as the Indian Act and residential schools. Indigenous identity and their unique relationship as protector and spokesperson of water affected Haudenosaunee women and their health. Haudenosaunee women's voices were silenced throughout the colonial era through multiple agencies. Anderson (2011) demonstrates the significant role that colonial subjugation played in the loss of status and power experienced by Indigenous women, which in turn crippled or fragmented societal and family structures, including those affecting Indigenous women and their authority and responsibilities. The imposition of the Indian Act over the last 120 years, for example, is viewed by many First Nations women as immensely destructive to the family unit. Forcing patriarchal policies on extended families eroded Haudenosaunee women's authority and reproductive autonomy. Colonial assimilationist policies threatened the existence of Haudenosaunee by outlawing their ceremonies and criminalizing their traditional economic practices. Further, the Indian Act's discriminatory policies utilized science to codify Indigenous inferiority. It justified horrendous policies to sterilize women, remove children from homes, and ban customs and culture. Once the Indigenous attachment to lands was subverted, the next phase in securing the European occupation of Indigenous lands was sterilizing Indigenous women (Stote, 2015). Treatment of Indigenous women in the form of forced/coerced sterilization was also recognized by the United Nations as torture, as an act of genocide and a violation of human rights, medical ethics and reproductive rights (Stote, 2015; Collier, 2017; Patel, 2017). Stote (2015) argues coerced sterilization must be considered in relation to the larger goals of Indian policy — to gain access to Indigenous lands. Epistemic violence is deeply rooted in justifying horrendous actions toward Indigenous people, women, and, we would argue, their natural world (Stote, 2015).

The inability to raise children with traditional medicines and in connection to land and water was also linked to colonial policies such as residential schools. Indigenous children were forcibly put into residential schools where they were not allowed to speak their language or practice their traditions (Partridge, 2010; Wilk et al., 2017; Cowan, 2020). “Killing the Indian in a child” was the motto, but the recent finding of more than 1300 unmarked graves in just four of the 150 residential schools proves that children were killed in those residential schools. More than 4500 children's bodies were found, and the number is rising (Hopper, 2021; Voce et al., 2021). Stealing children from their mothers, families, and community is still going on in the name of child welfare. Indigenous children aged 0 to 4 are overrepresented in foster care (Danison et al., 2013). Studies demonstrated that women often refuse health care for themselves in fear of losing their children to foster care (Danison et al., 2013). With no clean running water, women and children's health gets severely impacted, especially mothers and grandmothers who want to fulfill their responsibilities by raising the children with traditional medicines or just providing the basic rights to their children.

However, despite water insecurity in their community, SN women are resilient and use various culturally appropriate ways to cope with water insecurity, such as reconnecting with water. Both Indigenous and medical anthropological research demonstrated that people are innovative, exercise their right to live and adopt various culturally appropriate resilience strategies (Stout and Kipling, 2003; Scheper-Hughes, 2008). The Haudenosaunee have a unique way of dealing with sorrow, sadness, or depression, which Hiawatha, one of the founders of the Great Law of Peace, taught when he used ceremony, beads and wampum to deal with his tremendous sadness and depression over losing his daughter (Haudenosaunee Guide for Educators, 2009). Hiawatha's way is still used in the Longhouse as a condolence ceremony to overcome the grief and continue living with hope and clear thinking. Sustaining reciprocal relationships with the natural spiritual world through kinship systems renewed through cycles of the ceremony is foundational to Indigenous communities' resiliency, including the Haudenosaunee. Ohen:ton Karihwatehkwen is an ancient practice of giving thanks through recital; speaking to the plants, animals, water, and the wind is a reminder of gratitude. Haudenosaunee values and worldview survived throughout the colonial era. To demonstrate the brilliance of Haudenosaunee female leaders, Louise McDonald re-introduced 'rites of passage' to restore knowledge, values, beliefs and families. The Tehtsitewa:kenrotka:we “Together we pull it from the earth again” Ohero:kon Rites of Passage core premise is revealing multiple layers of being as corn is revealed after husking. Ohero:kon, “under the husk,” is an educational, instructional and ritualized ceremonial process drawn from the Haudenosaunee Skyworld story known as the “Earthgrasper.” Restoring the roles of uncle and auntie mentorship has had significant impacts in healing families often torn apart through residential schools or child welfare removal of children from home. A significant outcome overall is building leadership skills, interpersonal relationships, and restoring the rightful position of women through training the boys in supporting and respecting women and peers. The mentorship of 'Uncles and Aunties' nurturing 'nieces and nephews' with land-based skills is an asset to the community, particularly maternal health and parenting. Our research demonstrates that in addition to family and community support, water itself is a source of healing. Water has been significant to reconnect with traditional teachings, rejuvenate, and guide future directions.

Most research on Indigenous mental health focused on suicide and substance use despite highlighting social determinants such as poverty, the Indian Act, colonialism, and residential school trauma (Nelson and Wilson, 2017). Focusing on symptoms, not the root cause, did little on critically questioning the violent structure; instead, it further brought Indigenous people under medical gaze. The intersectionality of culture, history, colonialism, and mental health remained a less developed area (Waldram, 2004), and women are not fairly represented in the research about Indigenous mental health (Adelson, 2005). Our research co-creates knowledge about the impact of water insecurity by contextualizing it in larger violent colonial and assimilationist policies and structures. Research on water insecurity is relatively new compared with research on food insecurity, especially with the development of the water insecurity scale in recent years (Bulled, 2016). Water insecurity research has been significant in demonstrating its devastating impact on people living with limited to no access to clean drinking water. Results highlighted women to be affected more than men as they have more responsibilities toward collecting and providing water for their families (Collins et al., 2019). Studies that focus on mental health has been limited but has nonetheless made a significant contribution to highlighting that water insecurity affects women beyond the physical level and causes emotional stress, depression, and violence (Arsenault, 2021). Our research demonstrates that Haudenosaunee women understand mental health to extend beyond the absence of illness and is viewed in relation to the larger natural environment and all creation, including water. Therefore, the condition of water such as polluted and contaminated Grand River made them sad and depressed. Not being able to use water as medicine or collect medicinal plants by the water and thinking about other animals that depend on water affected their mental health. Haudenosaunee women connects themselves with mother earth and water in emphasizing the importance of water for their overall wellbeing. In Haudenosaunee's understanding of health, mental health, nature, and water get intertwined. This understanding of mental health recommends a different kind of healing—a healing that interweaves with the healing of nature. The participants trace this sickness of water and illness in the family and community to ongoing colonialism. As such, water insecurity in SN and its impact cannot be understood in isolation from the ongoing colonialism, racism, and discrimination against Indigenous people in Canada. Participants emphasized that trust needs to be restored, and the government of Canada needs to be sincere about solving water problems to restore sound mental health for Six Nations mothers and children. Water security will eventually restore the health of whole community. Stress and anxiety over accessing clean water, along with memory loss, and loss of clear thinking was reported by Haudenosaunee women. Not having enough water to drink and for daily uses, not being able to provide clean water to kids, not raising children and grandchildren traditionally, experiencing disrupted traditional relations with water, and living under settler colonialism all affected SN mothers mental and emotional health. Despite severe water insecurity Haudenosaunee women remains resilient by maintaining the connections with land and water and having social, familial, and community support. They all help Haudenosaunee foster good mental health.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (HIREB) and Six Nations Council Research Ethics Committe (SNCREC). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

AS: conception, methodology, analysis, original draft writing, structuring, and reviewing and editing. JW: conception, methodology, and writing and reviewing. DM-H: conception, supervision, and writing and reviewing. LD-H: reviewing and editing. JH: interviews. All authors contributed to revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We would like to express our gratitude to the Global Water Futures (GWF) for funding the Ohneganos research project in collaboration with the Six Nations of the Grand River. We are thankful to all Ohneganos project team members, Six Nations Birthing Center (SNBC) team, Six Nations Health Services (SNHS), Six Nations Land and Resources. We would like to acknowledge the School of Graduate Studies (SGS), and Department of Anthropology, McMaster University for the fieldwork and travel Grant. We are thankful to Dr. Ellen Badone, and the two reviewers to help making the article better than its previous version.

1. ^Sultana, A., Martin-Hill, D. & Wilson J. (forthcoming). “Location work” through “partial connections”: Co-developing research using CBPR and Kaswenta (Two-Row Wampum) with Tsi Non: We Ionnakeratstha Ona: Grahsta at Six Nations of the Grand River.

Adelson, N. (2005). The embodiment of inequity: health disparities in aboriginal Canada. Canad. J. Public Health. 96, 45–61. doi: 10.1007/BF03403702

Aihara, Y., Shrestha, S., and Sharma, J. (2016). Household water insecurity, depression and quality of life among postnatal women living in urban Nepal. J. Water Health. 14, 317–324. doi: 10.2166/wh.2015.166

Anderson, K. (2010). Aboriginal Women, Water and Health: Reflections from Eleven First Nations, Inuit, and Metis Grandmothers. Prairie Women's Health. p. 1–32.

Anderson, K. (2011). Life Stages and Native Women: Memory, Teachings, and Story Medicine. Winnipeg, Manitoba: University of Manitoba Press.

Andrews, K. M. (2020). Catching air: risk and embodies ocean health among dominican diver fishermen. Med. Anthropol. Quart. 35, 64–81. doi: 10.1111/maq.12592

Arsenault, R. (2021). Water insecurity in ontario first nations: an exploratory study on past interventions and the need for indigenous water governance. Water. 13, 717. doi: 10.3390/w13050717

Baird, J., Plummer, R., Dupont, D., and Carter, B. (2015). Perceptions of water quality in First Nations communities: Exploring the role of context. Nat. Cult. 10, 225–249. doi: 10.3167/nc.2015.100205

Barbeau, C. M. (1917). Iroquoian clans and phratries. Am. Anthropol. 19, 392–402. doi: 10.1525/aa.1917.19.3.02a00050

Barrea, J. (2020). Beyond the barricades. CBC News. Available online at: https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/longform/1492-land-back-lane-caledonia-six-nations-protest (accessed January 21, 2022).

Barrios, R. E. (2014). ‘Here, I'm not at ease’: anthropological perspectives on community resilience. Disasters. 38, 329–350. doi: 10.1111/disa.12044

Bourgois, P., and Scheper-Hughes, N. (2004). Commentary on an anthropology of Structural Violence. Curr. Anthropol. 45, 317–318.

Bowen, A;, N., Stewart, M., Baetz, M., and Muhajarine, N. (2008). Antenatal depression in Socially high-risk women in Canada. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health. 63, 414–416. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.078832

Brews, A., Rosinger, A., Wutich, A., Adams, E., et al. (2019). Water sharing, reciprocity, and need: a comparative study of interhousehold water transfers in sub-Saharan Africa. Econ. Anthropol. 6, 228–221. doi: 10.1002/sea2.12143

Bulled, N. (2016). The effects of water insecurity and emotional distress on civic actions for improved water infrastructure in rural South Africa. Med. Anthropol. Quart. 31, 131–154. doi: 10.1111/maq.12270

Burke, M., Gonzalez, F., Baylis, P., Heft-Neal, S., Baysan, C., Basu, S., and Hsiang, S. (2018). Higher temperatures increase suicide rates in the United States and Mexico. Nat. Clim Change. 8, 723–729. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0222-x

Cardona, G. L., Brown, K., McComber, M., Outerbridge, J., Boyer, C., et al. (2021). Depression or resilience? A participatory study to identify an appropriate assessment tool with Kanien'kéha (Mohawk) and Inuit in Quebec. Soc. Psychiat. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 56:10,1891–1902. doi: 10.1007/s00127-021-02057-1

Chandler, D. (2014). Resilience: The Governance of Complexity. Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315773810

Clair, R. P. (2003). The Changing Story of Ethnography.in Robin Patric Clair ed. Expressions of Ethnography: Novel Approaches to Qualitative methods, State University of New York.

Collier, R. (2017). Reports of coerced sterilization of Indigenous women in Canada mirrors shameful past. CMAJ. 189, 1080–1081. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1095471

Collins, S. M., Owuor, P. M., Miller, J. D, Boateng, G. O., Wekesa, P, Onono, M, and Young, S, L. (2019). “I know how stressful it is to lack water!” Exploring the lived experiences of household water Insecurity among pregnant and postpartum women in western Kenya. Glob. Public Health. 14, 649–662. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2018.1521861

Cook, K. (2008). “Powerful like a river: reweaving the web of our lives in defense of environmental and reproductive justice,” in Original instructions: indigenous teachings for a sustainable future, ed K. N. Melissa.

Cowan, K. (2020). How residential schools led to intergenerational trauma in the canadian indigenous population to influence parenting style and family structures over generations. Canad. J. Family Youth. 12, 26–35. doi: 10.29173/cjfy29511