- 1Department of History, Geography and Philosophy, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA, United States

- 2Kathleen Babineaux Blanco Public Policy Center, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA, United States

- 3Department of Civil Engineering and Louisiana Watershed Flood Center, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA, United States

- 4Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, NOAA-University of New Hampshire Joint Hydrographic Center, Durham, NH, United States

Many communities across the USA and globally lack full understanding of the flood risk that may adversely impact them. This information deficit can lead to increased risk of flooding and a lack of engagement in mitigation efforts. Climatic changes, development, and other factors have expedited changes to flood risk. Due to these changes, communities will have an increased need to communicate with a variety of stakeholders about flood risk and mitigation. Lafayette Parish, Louisiana, USA, having recently experienced a major flood event (the 2016 Louisiana Floods), is representative of other communities experiencing changes to flood impacts. Using focus groups, this study delves into better understanding the disconnect between individual and community perceptions of flood risks, and how emerging hydroinformatics tools can bridge these gaps. Using qualitative analysis, this study evaluated the resources individuals use to learn about flooding, how definitions of community impact flood mitigation efforts, how individuals define flooding and its causes, and where gaps in knowledge exist about flood mitigation efforts. This research demonstrates that individuals conceive of flooding in relationship to themselves and their immediate circle first. The study revealed division within the community in how individuals think about the causes of flooding and the potential solutions for reducing flood risk. Based on these results, we argue that helping individuals reconceive how they think about flooding may help them better appreciate the flood mitigation efforts needed at individual, community, and regional levels. Additionally, we suggest that reducing gaps in knowledge about mitigation strategies and broadening how individuals conceive of their community may deepen their understanding of flood impacts and what their community can do to address potential challenges.

Introduction

Bridging the gap between individual perception of flooding and understanding of community risk is a significant challenge for flood managers, community leaders, and the public. This gap poses a sizable hurdle for improving overall community awareness and mitigation of flood impacts. Recent research indicates that disparate levels of risk perception (Lechowska, 2018; Wang et al., 2018; Verlynde et al., 2019) impact a community's ability to function cohesively including which decisions they should make to mitigate increasing flood risk. This can have important social and economic implications for the community in terms of which strategies are adopted to address flood mitigation. For example, a recent study reported high benefit-to-cost ratios when assessing different strategies for reducing flood damages in the United States by avoiding development in floodplains and investing in land acquisition and conservation practices, versus allowing development and paying for flood damages when they inevitably occur (Johnson et al., 2020). Similar assessments, when performed at a specific community scale, would provide valuable information to different stakeholders regarding their decisions in pursuing strategic flood reduction measures while simultaneously ensuring a progressive and sustainable economic growth in the future.

Individuals often have a tendency to underestimate risk for themselves and the potential impacts on their community (Filatova et al., 2011; Haer et al., 2020; Bakkensen and Barrage, 2021). This underestimation of risk negatively affects individuals' perspective on flood risk. Individual risk is often understood through the lens of whether a particular location flooded during a past flood of note, which translates into a misperception of binary risk (e.g., inside or outside of the flooded area). Economic and social linkages within a community can amplify flood impacts, making the actual risk more consequential than the sum of individual risks. For example, if one house is flooded, it may have a negligible effect on another family; however, if a whole neighborhood (or large section of a city) floods, businesses and employers' customers or workers are impacted. On the social side, flooding might cause strain on an individual's social network and place an obligation on individuals to provide support to the impacted areas. These additional levels of risk are typically unaccounted for in an individually-focused risk assessment that stops at the local scale (e.g., home, place of work, or immediate social circle) and are generally more difficult for individuals to assess accurately.

In addition to complications with individually focused risk assessment, individual risk is also nested within community risk. Currently, there is a lack of shared understanding and communication among stakeholders in many flood-prone communities (residents, governments, elected officials, developers, advocacy groups, and technical experts), which often lead to conflicting views on causes of flooding and which flood mitigation measures may be most effective (Bixler et al., 2021; Mostafiz et al., 2021; Wilson et al., 2021). Such conflicting views are manifest across different stakeholders within the community, including the public, government officials, engineers and planners, and as such will impact how the community moves forward with addressing flood risk. Some of these conflicting views have led to litigation within and between neighboring communities (Capps, 2022; KATC, 2022; Turk, 2022). The lack of shared understanding can impact the public's support (or lack thereof) for a viable mitigation project, or the likelihood of community members rallying behind a less effective project. Likewise, the public may not be adequately equipped with resources or information that allow them to communicate their needs to the engineers, planners, and officials who are ultimately responsible for designing and implementing certain projects. Typical examples of projects for which divergent views may arise are nature-based solutions for flood mitigation, versus other alternatives that include major structural and channel modifications (e.g., Kumar et al., 2021; Saad and Habib, 2021). Additionally, there are limitations to how individuals define community. If individuals view their community as only extending to their neighborhood, city, county (called “parish” in Louisiana), this limits their awareness and engagement with community flood risk and mitigation efforts.

Since the passage of the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968, efforts have been made to address the gaps between individual and community flood risk. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Flood Maps are the most well-known and utilized resource on flooding, yet they have limitations that reduce their usage and educational value. The new insurance pricing methodology, known as Risk Rating 2.0 (Federal Emergency Management Agency., 2020, 2022), is expected to bring new dimensions to how communities deal with floods. Using new data and modeling technologies, the Risk Rating 2.0 is intended to improve the accuracy of a property's flood risk profile, as opposed to an aggregated quantification that is currently followed. However, the new rating system is expected to result in dramatic premium increases for some areas of the US, which may further complicate community-level perceptions of flood risk (Littlejohns, 2019; National Association of Realtors, 2022).

This study focuses on better understanding the disconnect between individual and community perceptions of flood risks including: (a) divergent perceptions of flood risk and causes; (b) definition of community; (c) the needs and effectiveness of mitigation efforts; and, (d) the current limitations and availability of flood information and resources. The study also presents some insights on how emerging hydroinformatics tools including hydrodynamic modeling and geospatial visualization fused with socioeconomic data can bridge these gaps (Mostafiz et al., 2022). Flood risk communication engages individuals and communities in the process of mitigation and response to flooding. If individuals do not understand why or how individuals and communities are connected, they cannot fully understand how they should respond to extreme events or implement mitigation efforts to prevent these events. Improving the understanding of flood risk can help decision-makers (e.g., planners, developers) develop more effective flood risk mitigation strategies with enduring public support (Sadiq et al., 2019; Verlynde et al., 2019).

The study context: Lafayette Parish, Louisiana, USA

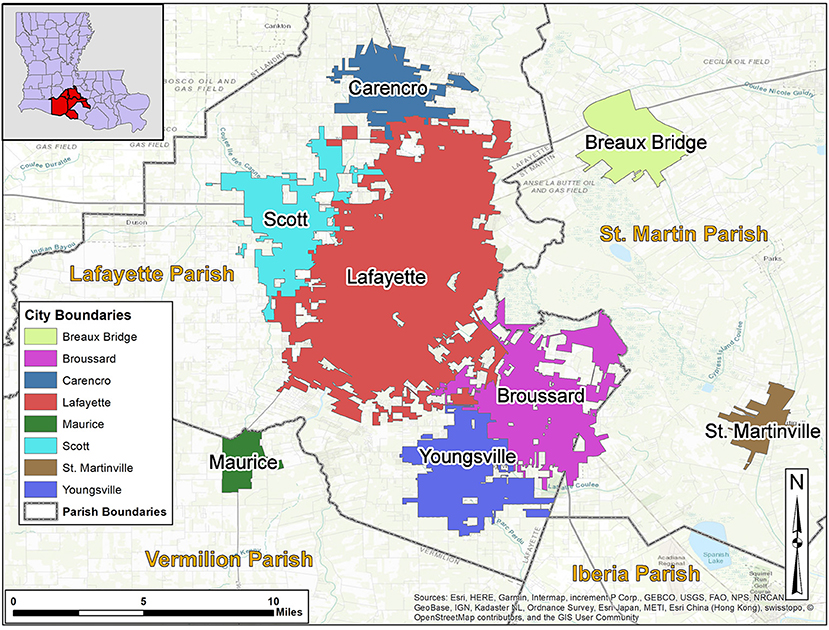

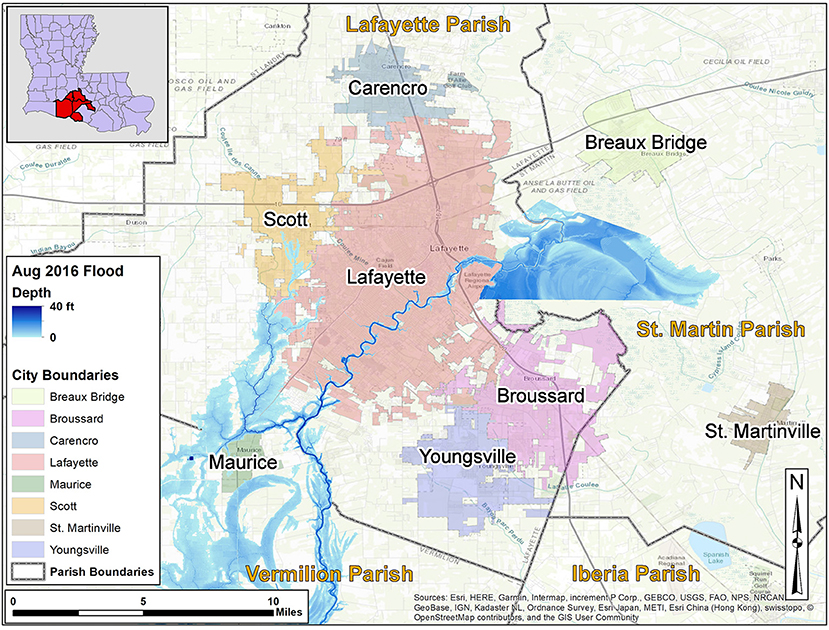

The area of interest in this project is Lafayette Parish (county) in south Louisiana, USA. This region has several urban centers, including the Cities of Lafayette, Scott, Youngsville, and Broussard (see Figure 1). The parish has a population of 126,143 with 55,440 housing units and a median housing value of $181,900 (US Census Bureau) and is home to 10,031 businesses with 131,571 employees and average annual pay of $48,448 (U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019). Lafayette Parish cities score low to medium-low on the Social Vulnerability Index.

Louisiana is historically prone to significant riverine and coastal flooding due to its position on the Gulf of Mexico and in relation to the Mississippi River and its tributaries and distributaries. Located 90 miles inland from the Gulf of Mexico, Lafayette Parish experiences occasional riverine flooding but rare coastal flooding, leaving the community to initially consider itself as a low-risk flood zone. The area is characterized by low gradient topography, which results in slow drainage patterns and repetitive flooding (Watson et al., 2017). Combined with the presence of large natural storage areas (e.g., swamps) the area witnesses complex flow regimes such as reverse flows and backwater effects (Waldon, 2018; Saad et al., 2021) that complicate the decision-making process about which flood mitigation measures to pursue and may lead to controversial views about effectiveness of such measures.

In August 2016, Lafayette Parish experienced a historic flood caused by a low-pressure system that resulted in up to 31.39 inches of rain in three days (Wright, 2016). The amount of water overwhelmed existent drainage systems, driving 10 major rivers in the region beyond flood stage, and roughly equaled three times the amount of water left behind by Hurricane Katrina (Samenow, 2016). Twenty-six of Louisiana's sixty-four parishes were declared federal disaster sites, including Lafayette Parish (Terrell, 2016; Louisiana Office of Community Development Disaster Recovery Unit., 2017; Federal Emergency Management Agency., 2020). Within the parish itself, significant flooding occurred to the City of Lafayette, outlying suburbs, and adjacent southern parishes (Heal and Watson, 2017). The 2016 Floods also drew attention to the connected nature of Lafayette Parish's watersheds, as communities downstream from the City of Lafayette faced challenges regarding the flow of water through the region (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. USGS August 2016 Flood Extent Map (Heal and Watson, 2017).

This historic flood continues to serve as a benchmark for flood-related risk assessments and mitigation strategies. It is also the primary metric used by individuals in the parish to assess their flood risk. In 2018, the City of Lafayette was selected to participate in the Mayors Challenge sponsored by Bloomberg Philanthropies which resulted in the community identifying flood risk as a primary challenge. This community exemplifies the experiences of other US communities that increasingly find themselves at risk due to flooding caused by climate and land use changes.

Methods

The overall goal of this study was to test research hypotheses on possible solutions for communities' inability to reach consensus on diagnosis of and shared vision for addressing flood risk at both the individual and community scales.

Our four primary hypotheses for this study were:

• There is a disconnect between individuals' understanding of their personal risk compared to their community risk.

• The lack of stakeholder understanding of flood risk as individuals (e.g., flooding of homes) and as a community (e.g., business interruptions) contributes to community disengagement from flood mitigation decision making, both at individual (e.g., buy flood insurance) and community levels (e.g., vote on stormwater fees).

• Gaps in flood communication between subject matter experts, policy makers, and the public create conflicting understandings about flood risk and the opportunities for mitigation.

• Current flood information tools do not adequately communicate flood risk to all stakeholders equally.

In order to test these hypotheses, we held a series of focus groups (eight in total) with community members of Lafayette Parish. Prior to each focus group, we circulated a pre-focus group survey that we used to jumpstart discussions in the focus groups.

The goal of the focus groups was to bring together Lafayette Parish residents and hear their perspectives on flood risk at both an individual and community level. We wanted to know whether residents understood their flood risk as connected to larger community flood risk or as solely an individualistic problem that affects them personally. We used a broad definition of flood risk and allowed participants to define what flood risk meant to them. Participants generally discussed flooding in relationship to their home or place of work, but some also discussed transportation systems, including the impact of flooding on their vehicles, commutes, and popular locales.

Our belief was that most community members would have some understanding of how their flood risk was tied to community flood risk, but that they may lack resources or information that fully illustrated their connectivity to the community as a whole. Therefore, we designed our focus group questions with an assumed baseline knowledge of individual flood risk, but a lesser knowledge of community flood risk and mitigation efforts or tools that demonstrate these factors. We share our belief here as a way of describing our own biases that may have influenced the lens we used for study construction and data interpretation. However, we cross-checked these beliefs through the use of an optional pre-focus group survey to gain some background knowledge on our assumed beliefs and to guide initial discussions. While the current study was conducted prior to the full rollout of the FEMA Risk Rating 2.0 system, and as such could not be addressed in our analysis, it is expected that the new system will bring further complexities on how communities perceive, plan and make decisions about their flood risk.

We also wanted to learn through our study which types of hydroinformatic tools and resources they currently use to help understand their flood risk (both individually and collectively) and ascertain which types of tools or resources they might want to better help them understand future flood risk. Included in our definition of hydroinformatic tools and resources are those that fuse heterogeneous information from multiple sources such as socioeconomic analyses, hydrodynamic modeling, and geospatial visualization.

Focus groups provide a semi-structured method for eliciting subject responses yet allow participants the opportunity to have unstructured dialogue on issues they felt were significant but might be overlooked in a more structured inquiry such as a survey (Krueger and Casey, 2014). Focus groups provide the opportunity to observe how community members communicate their understandings of flood risk and mitigation efforts to other community members (Krueger and King, 2005). This dialogue offered a way to analyze synergies between groups and individuals. It also illustrates the problems faced by communities in addressing flood risk at the community scale.

Description of focus groups

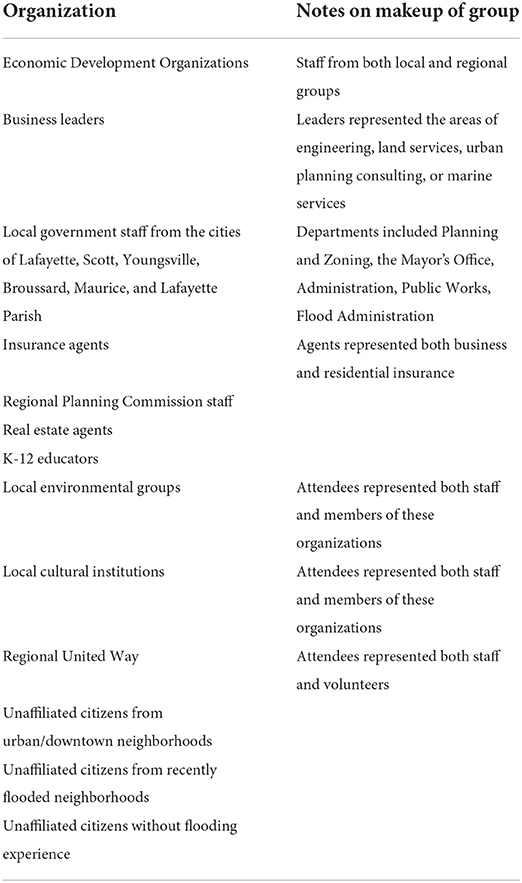

We conducted eight focus groups (~7–15 individuals/group) with members of the greater Lafayette Parish community described above. Prior to the focus groups, we circulated an optional 11-question survey to utilize in our focus group discussions (see Appendix). During the focus groups, discussions centered on what each group needs to better engage in flood mitigation and planning. To gauge the diversity of flooding impacts within the community, and based on input from the local government, we conducted focus groups for individuals in neighborhoods with repetitive flooding as well as those in neighborhoods with infrequent flooding. Participants included leaders from a variety of different groups (Table 1). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all focus group interviews were conducted virtually using Zoom. Our team had extensive experience during 2020 and 2021 conducting stakeholder focus groups using video conference tools (Habib et al., 2021). Focus groups were 1 h and 30 min in length and included a pre-survey of 5–10 min. All focus groups were held during daytime periods. Two focus groups were held over the noon hour, three were held on Friday afternoons near the close of business. While we did schedule an evening meeting, it was canceled due to lack of participant interest. Participants were not reimbursed for their time.

Study population

Our focus group interview study was approved by the University of Louisiana at Lafayette IRB on December 2, 2021. Focus group interviews were conducted between January and March of 2022. Our total focus group participant sample size was 60, of these 47 took the pre-survey. Participants received a link to the online pre-survey after indicating their interest in joining a focus group. A reminder about the pre-survey was sent again a day before the focus group. Most community members that participated in the focus group interviews were: (a) from Lafayette Parish, (b) interested in flood mitigation or related issues, (c) solicited through prior contacts with community outreach organizations or individuals, (d) or contacted using a snowball method of participant selection. While we did not request demographic or residency information from focus group participants, most community members indicated in the focus group discussions that they lived in Lafayette Parish. A small number shared that they were residents of parishes adjacent to Lafayette Parish. We did not ask participants why they chose to volunteer their opinion, but we noticed that most participants indicated their interest in flood mitigation or related issues. Additionally, while we did not track the age of our participants as a defined characteristic of our study, no members were under 18. Due to pandemic-era restrictions that required Zoom focus group discussions, technological challenges may have inadvertently limited access to our focus groups from those with digital literacy or connectivity barriers. While we attempted to reach out to community groups representing these populations to increase participation in later focus groups, our efforts were only minimally successful given the time restraints we had for our study.

Questions asked

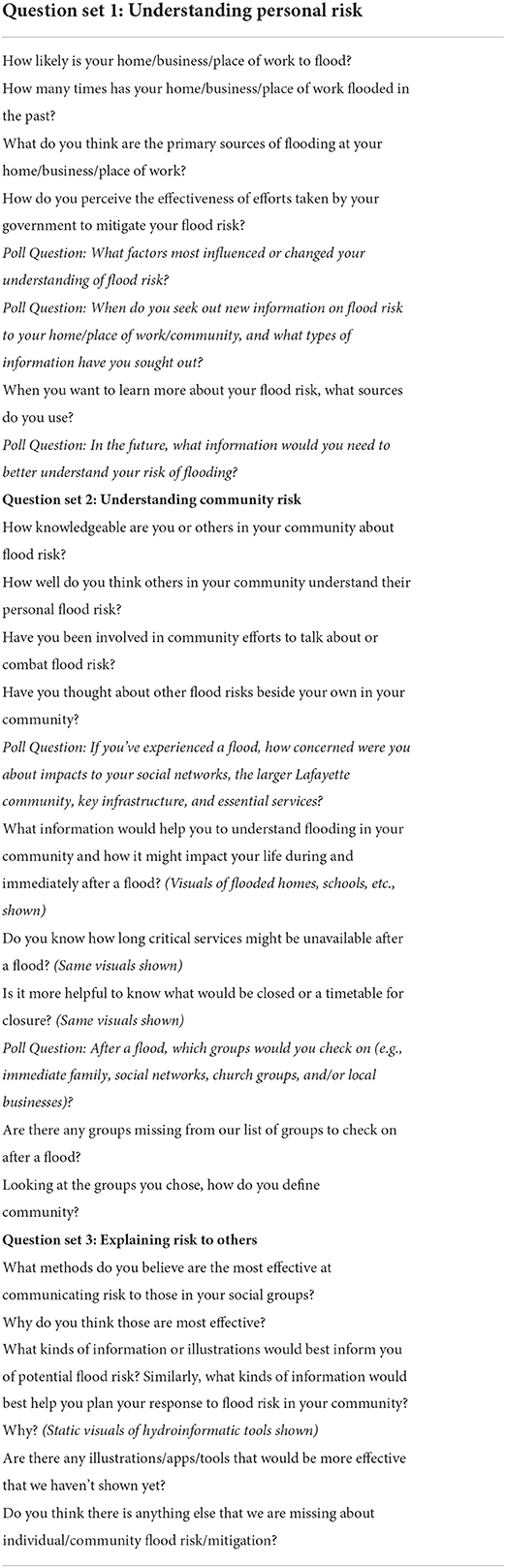

In our focus group interviews, we asked several questions related to our hypotheses (see Table 2 for an abbreviated list of questions; see Appendix for full list of questions). We also prompted participants with visuals (e.g., images of flooded cars and houses; road, gas station, and school closures; potential flood risk illustrations) pertaining to the questions asked and conducted polls to initiate discussion.

A pre-focus group survey was circulated to participants prior to the focus group, asking them to reflect on their perceptions of community and individual risk of floods to their properties, businesses, and Lafayette Parish. We also asked participants to gauge their level of understanding of risk factors for flooding. Finally, we asked participants about the number of repeated flood incidents they have experienced.

During the focus group, we grouped questions into three sections for discussion. The first set of questions reviewed participants' understanding of their individual risk to flooding at their home/business/place of work. We asked questions about the number of times they or their business/place of work had flooded and their knowledge of the reasons behind this flooding.

In the second portion of the focus group, we asked participants to reflect on their understanding of community risk for flooding. We first asked participants to define their community and the types of flood risk affecting it and other surrounding communities. We prompted them with Zoom polls that asked them which social groups and key locations they prioritize during and after a flood. We asked questions about participants' perspectives on the perceived effectiveness of their local and state government in addressing flood risk. We also asked about their knowledge of the reasons and frequency of flooding in their community, as well as how their community responded to flood risk or floods in the past.

In the third and final section of our focus group interviews, we asked participants what tools and resources they or others use to understand community and individual flood risk. One set of questions asked about the types of flood information systems that participants have used or continue to use to understand their flood risk. These included the flood information systems that have already been developed, either on a national scale by governmental (e.g., FEMA Flood Map) or non-governmental organizations (e.g., First Street Foundation's FloodFactor); or on a regional or local scale, even if they were in a preliminary stage (e.g., the Lafayette Consolidated Government drainage project portal). We also shared examples of flood information systems from other states (e.g., Texas Onion Creek Flooding Simulation and Texas Water Board Development Flood Decision Support Toolbox). We provided static visuals of some of these current tools and asked participants which illustrations they found most useful and why. Another set of questions asked participants about effective ways to communicate about tools, resources, or information related to flood risk and in which forums to provide this communication. For example, we asked participants whether social media, websites, or other media outlets were effective in expressing flood risk, or what other mechanisms of communication might be more effective in the future.

Analytical techniques and qualitative coding methods

For the pre-surveys circulated to participants of the focus groups, we shared the mean and distribution of specific answers in the pre-survey to prompt discussion among participants during group interviews. The results of the pre-surveys were included in the focus group notes (Saldana, 2021). All focus group interviews were recorded and fully transcribed using Zoom auto transcription or Trint transcription software. Transcriptions were cross-checked following transcription conventions by undergraduate research assistants to ensure the text accurately represented individual participants' thoughts in response to questions.

Informed by a grounded theory approach to qualitative research analysis (Strauss and Corbin, 1998), the research team used our data to inform our analysis process and outcomes. The research team began by collecting and collating detailed notes taken in two different ways during the focus groups. One set of detailed notes primarily tracked emphasis, intensity, and frequency of perspectives on questions and topics discussed. The second set of detailed notes focused on recording the technical details of hydroinformatic data usage and understanding. A final set of summary notes were created by the research team after the focus groups to collectively reflect on key themes and identify initial concepts for coding (Miles and Huberman, 1984).

Data were coded by hand (as opposed to using qualitative analysis software) using the coding scale developed through the reflective process described above. The first round of coding counted frequencies of particular themes such as Understanding of Flooding and its Causes (e.g., localized, person/work/community), Definition of Community (e.g., property, neighborhood, city, parish, watershed, state), Gaps in Knowledge About Mitigation Efforts (e.g., personal/government), and Resources Used to Learn About Flooding (e.g., tools/technology). After the first round of coding the research team met to discuss initial coded results and to collaborate to add data into more meaningful groups. At this time, the research team also incorporated deviant case analysis to make sure minority opinions from the focus groups were represented in the research (Kitzinger, 1995). A second round of coding more closely evaluated direct language used by participants to examine synergies between the themes identified in the first round of coding as well as select key quotations that represented emerging themes from the research findings. Throughout the coding process, the multidisciplinary research team met frequently to discuss how to use knowledge learned from the focus groups to develop preliminary tools to test in further field work with the community and to solidify research findings. The multidisciplinary nature of the research team produced meaningful discussion that informed the approach to coding.

Results

In reviewing the data collected from our focus groups and keeping in mind that the objective of this study was to evaluate how communities and individuals reach a shared vision of flood risk, we found that community members tend to discuss flooding and flood risk in relationship to themselves and their perceived view of community. This approach to thinking about flooding and flood risk shapes how they understand flooding and its causes, their definition of community, their gaps in knowledge about mitigation efforts, and the types of resources they use to learn about flooding.

Understanding of flooding and its causes

At the beginning of our focus groups, we briefly reviewed the results from our optional pre-focus group surveys. As we reviewed the results from the pre-focus group surveys, focus group participants were offered the opportunity to add their input to the pre-survey results (if they had not had a chance to fill out the pre-survey) and elaborate on their chosen selections in the survey. As they did so, participants discussed how they defined flooding and its causes. They also highlighted their experience with floods and how it relates to their knowledge about what causes flooding or lack thereof.

Participants cited the 2016 Floods as a catalyst that changed perception and understanding of flooding, with regards to either their own risk or the risk of others, stating so in 13 instances. In terms of experience, many Lafayette Parish residents confronted the realities of flooding for the first time in 2016. Others who did not flood, considered themselves or location relatively safe from future flooding. From either point of view, participants regarded 2016 as a metric by which to examine their risk moving forward. A participant noted “I just wonder... had we taken the survey prior to 2016 flooding and [then again] after, what the results would have been. Before that hundred year flood, I would've said low, but since our house experienced flooding, I said high” (Department of History, 2022g, 10:40). Another said: “It's kind of silly because I probably should have more knowledge about this, but in terms of my home, I guess I was thinking that well, in 2016, we didn't experience any flooding. So I guess that's why I said it was a pretty low chance of our home getting flooded” (Department of History, 2022a, 9:13).

The impact of the 2016 Floods forced individuals to think about flooding beyond their own property. One individual noted that they now pay more attention to the impact of flooding on manufacturing and oil and gas facilities in the region (Department of History, 2022b, 1:01:05). Manufacturing and oil and gas have historically been the predominant economic drivers for the Lafayette Parish region (Wagner and Barnes, 2022).

The 2016 Floods also highlighted the disparity in understanding how the management of water across the region impacts individual properties and the community. Drainage, inadequate channel capacity, and outdated and under-designed infrastructure were all issues brought up by participants as areas of misunderstanding when discussing causes of flood risk.

In discussing disparities in understanding the causes of flood risk, individuals also brought up that each person's definition of flooding often shapes their understanding of flooding and the narrative they use to describe community risk. It also impacts their willingness or desire to engage with flood mitigation efforts. As one participant noted, “Even though your house doesn't flood, our streets flood often” (Department of History, 2022d, 17:35). If you define flooding as risk to personal property (like a house), street flooding may not be a concern. In looking at flooding beyond just one's own property, the average Lafayette Parish resident must then reckon with the impact of flooding to others in their community as well.

Lafayette Parish residents noted that they also need to broaden their understanding of what causes flooding. Most participants mentioned development as the primary cause of increased flooding in their community. They also mentioned increased volume of flood water, outdated or inadequate infrastructure, lower elevation, and proximity to water. In conversations, however, individuals expressed doubts about which factor was most important. This also varied based on whether they were discussing flooding from the viewpoint of their personal property or at the community level. This variance highlighted the need for accessible information tools that consider local knowledge and historic data.

Definition of community

Much like participants noted the challenges of understanding the impact of flood events on their community, they also noted differences in how various groups defined their community (in relation to floods).

Flood events create moments for individuals to evaluate community risk and response. According to focus group participants, the 2016 Floods caused them to reflect on how flooding affects both themselves and their community. It also revealed differences in the way individuals defined their community. Some participants noted that their community was defined broadly, including those in their neighborhood, city, or parish. Others suggested that only those within their immediate proximity, such as their direct neighborhood or within their pre-existing social network, constituted their “community.” Thus, their understanding of flood impact was reliant on experience held by those groups. A participant noted, “If you've flooded, you know. You start paying attention. Or if you nearly flooded, you really start paying attention because you don't want it to happen again. Okay, so if you didn't flood. You know, you don't have interest in it, so you may not be paying that much attention” (Department of History, 2022b, 51:33). A participant in a separate group concurred, “I feel like we're just so tempted to think of it as a problem for the people who flooded” (Department of History, 2022f, 30:00).

Flood events also create moments of reevaluation of risk impact for both individuals and businesses. One focus group participant noted the impact of flooding on business owners, their workforce, and customers. While business owners experience damage to their property, they also experience problems with an impacted workforce and customers made up of individuals having to rebuild their own homes. As illustrated by the participant: “If you're a key employee for a business here in town and you got a chance to rebuild your house—which may take a year after a major flood like 2016—[the flood is] detrimental not only to your home, [but] to your business, enterprise, or even more” (Department of History, 2022b, 1:18:40).

This lack of awareness of the experiences of other groups creates a homogenized understanding of flood risk and experience in a community and serves as an obstacle to understanding the reasons for or importance of flood mitigation efforts. As a participant stated, “Unfortunately those people that are not subjected to [flooding]... don't really have the knowledge because they don't worry about it and [have not experienced it]” (Department of History, 2022c, 56:09). This homogenized understanding of flood risk and experience also lessens the awareness of experiences of already at-risk and under-resourced communities. Within the focus groups we saw the dichotomy and friction between different groups and their interests. See the excerpted exchange below from one of our focus group discussions of this topic.

Participant 1, representing a marginalized group in the City of Lafayette community, stated:

The building I live in is elderly, low income housing, and our fear, the fear that multiplies over time is […] the housing is allowed to deteriorate, more and more, [...] we become very worried that the next flood will be the one where they shut the place down and we have to go find somewhere else to live. Knowing how hard it is to find a place, an affordable place to live in Lafayette, it makes people willing to live with mold in their apartment and with their ceiling and walls falling, falling down because they really just don't want to lose a place to live because it might take a long time. It might take years to get another place to live (Department of History, 2022b, 1:07:50).

In response to Participant 1's comments, Participant 2 replied:

The poor, unfortunately, are going to be living in the lower areas—in more vulnerable areas for flooding to begin with. So that's a known fact. [...] You can't do anything about low income people renting properties in low areas. That's just going to happen (Department of History, 2022b, 1:08:56).

This exchange illustrates the differences in conceptions of community and acceptable levels of risk for those within and outside of an individual's defined social community.

In addition to complications raised by an individual's defined social community, very few participants saw their community extending beyond the geographic scope of the parish except when it negatively affected their own community. For example, the City of Lafayette's downstream suburbs of Youngsville and Broussard and the adjacent parishes of Vermilion and St. Martin complained of the excess runoff created by floodwaters in Lafayette Parish worsening flooding in their communities. This has unfortunately created animosity including lawsuits between some of these communities over flood mitigation efforts and understanding of flood risk (Capps, 2022; KATC, 2022; Turk, 2022). As noted by one participant:

There's a huge lack of understanding. There's a huge lack of trust between the parishes. I see this, you know, in communicating with these parish leaders. “We don't want Lafayette's water.” You know, I've heard that story a bunch of times from different parishes around us. Well, I'm sorry. If you happen to be south of Lafayette, you're going to get Lafayette's water no matter what. It just happens to flow that way. So why can't we work together to try to solve this problem? (Department of History, 2022b, 30:40)

All of these factors—the fragmentation in defining one's community, the exclusion of certain populations from the definition of community, and the complication in extending the definition of community to include larger geographic scopes of community—create obstacles in understanding the multifaceted problems that affect communities. These conflicting definitions of communities complicate the creation and implementation of effective flood mitigation strategies.

Gaps in knowledge about mitigation efforts

In focus group discussions, there were significant gaps in the knowledge about mitigation. Participants noted a perceived lack of understanding about what local governments, builders, and developers, and the state and federal governments were doing to mitigate flooding in Lafayette Parish and surrounding communities. Participants also self-identified their own knowledge gaps about what they could do personally to mitigate flooding and the causes of flooding.

Within discussions about the perceived lack of understanding about what local governments were doing to mitigate flooding, participants expressed concern about outdated and overextended infrastructure that they blamed for increased flooding. As one participant stated, “These roads and our infrastructure [are] built to withstand a certain kind of storm, [...] and so their capacity isn't designed to handle it. It's not like they're designed wrong, they're just no longer keeping pace with the rate of precipitation that we're experiencing today” (Department of History, 2022e, 33:53).

Another participant described how drainage frequently dominates conversations about flooding, sometimes at the risk of ignoring other flood mitigation opportunities:

[Y]ou just can't keep people from talking about drainage. Somehow, we have got to communicate that when you drain a property, that water doesn't just disappear. When you drain a property, you're draining it onto someplace else or into some stream. And it's very, very possible, and even likely, that when you do a project that reduces flooding on one property, you're going to increase flooding on other properties (Department of History, 2022c, 1:25:25).

A final concern raised by participants was the lack of knowledge and transparency about local flood mitigation projects developed by the local and federal governments. As stated:

There's not really much visibility of this. Because I think: “Are they doing anything to mitigate flood risk? Are they doing work, you know, drainage projects?” And I'm sure they are, but they're not really publicized. There's not a real, clear list of projects and what order they're going to be done in and how that priority was determined. How do you know who decides and how do they decide what projects are going to be the most immediate and which ones are going to be have to be done later? I don't know (Department of History, 2022b, 28:00).

While participants expressed concern about the lack of knowledge regarding projects run by governmental entities, they also raised concern about projects undertaken by private groups. Due to rapid development in the City of Lafayette and the exurban area, builders and developers were a primary focus of participants' anxiety about unknown outcomes of geographic expansion. The conflict between expanding local revenue and the ability to address mitigation was expressed by one participant when they said, “We can let a developer build a subdivision there, and all of a sudden we've got millions of dollars of tax base and all kind of revenues. [But] we need to really seriously look at what we're doing” (Department of History, 2022b, 24:10).

Even developers themselves raised concerns about communicating the efficacy of flood reduction projects and regulating development. As one developer put it:

All those subdivisions that are getting permitted now, they're developing under some of the strictest drainage requirements that we've ever had—[but] we're just continuing to make it harder and harder as a community to drain because just now that we have more and more development, more and more concrete, it's like we're doing smart things at like a micro level, but then at a macro level, I think we're still kind of missing the boat (Department of History, 2022f, 30:00).

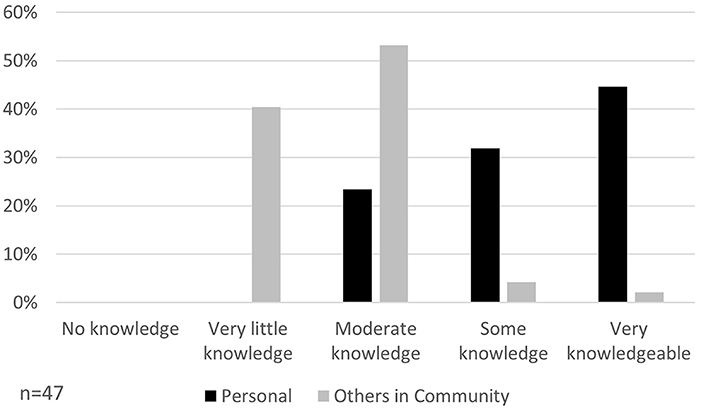

These gaps in knowledge about what larger entities such as governmental bodies are doing to mitigate flooding in the community also extend to conflicts in perceptions of what individuals can and should be doing to mitigate flooding. Whether justified or not, many Focus Group participants believed that they had a good grasp on how to address flooding, but more firmly believed their fellow community members' knowledge was limited. Seventy-seven percent of participants expressed in a pre-focus group survey that they felt somewhat or very knowledgeable about their own personal flood risk and how to mitigate it. In comparison, they stated that 94% of other community members had moderate or very little knowledge about flood risk and how to mitigate it (see Figure 3). In follow up focus group discussions, participants frequently expressed that rudimentary steps that could be taken to mitigate flooding on an individual level were often ignored or not met with immediacy. As one participant noted when reflecting on localized dumping and blockage of drainage systems, “If people understand that what they throw on the ground ends up in the waterway, maybe that would keep them from wanting to do that” (Department of History, 2022c, 1:16:00). Recent homebuyers and renters expressed a lack of clarity on what would happen with their property during flooding, which affected how they approached flood mitigation efforts personally. One participant stated, “Currently I'm renting, and I've been there for two and half years, but what happened five years ago, 10 years ago—I have no idea, so a lack of information for me is definitely part of it” (Department of History, 2022h, 13:08).

Participants also questioned if changes in flood risk were related to larger climatic shifts and to what degree this affects them locally. Discussions focused on rainfall amounts, storm intensity, and perceived knowledge of historic events. In discussing increased rainfall, participants were split on whether rainfall amounts have actually changed. As one participant stated, “[there has been] very little change from 1994 to 2020. The variation is only three or four inches here” (Department of History, 2022e, 38:48). They instead cited other factors as the cause for increased flooding. Meanwhile, another participant expressed, “I can definitely see a change in the intensity of storms and the amount of floods since I was a child up until I was an adult” (Department of History, 2022a, 24:43). Despite this split in the perception of changes in intensity, participants were hesitant to blame changes on climatic fluctuations. One argued, “When you start telling them ‘Okay, this is some of the problems' [They reply] ‘Oh, no. That's not the problem. The problem is climate change.' Well show me, okay?” (Department of History, 2022b, 57:30). Instead of accepting climatic change as a driver of increased flooding, participants were apt to divert the conversation back toward the impact of large scale development.

In addition to the lack of knowledge about individual actions to mitigate flooding and its causes, participants struggled to name tools or services that would help them adequately assess their own risk. This was congruent with the common theme that there is a tangible disconnect between citizens and the services that are meant to help them. Many participants either said they had very little understanding of their own flood risk or public mitigation efforts currently underway and directly expressed a desire for an open line of communication between flood professionals and citizens.

Often these knowledge gaps were a result of flood knowledge based on personal experiences rather than broader information tools. One participant stated, “Once you've experienced [flooding], you are much more cognizant in making decisions based on that” (Department of History, 2022g, 11:54). In contrast, participants who had not flooded were not incentivized to look for information about flood mitigation. One admitted, “For most people, unless you're directly affected by something, you just kind of disregard it, and that's been the case for me” (Department of History, 2022h, 1:03:09).

Resources used to learn about flooding

In our focus groups, community members identified hydroinformatic tools and technologies (e.g., geospatial data and model simulations, web-based flood portals, interactive visualizations), analytical information about flooding, as well as trusted individuals as their sources for how they conceptualize and respond to flood information.

FEMA Flood Maps are the most frequently used resources to learn about flooding. Participants mainly cited FEMA flood maps when discussing purchasing homes, rather than during a flood event. Even then, many were quick to point out that these maps are not always accurate, and that “the water is not just going to stop at jurisdictional boundaries” (Department of History, 2022a, 38:23) and “the flooding isn't just going to stop at an imaginary line on a piece of paper” (Department of History, 2022a, 1:13:06). Participant use of FEMA flood maps localizes their understanding of flood risk to their individual property and how it affects their insurance rates, rather than shed light on community-wide risks.

The use of trusted individuals was the second-most used resource to learn about flood risk. Trusted individuals could be found in person, via social media, and through personal or recommended connections. These trusted individual conversations provide direct insight into details not fully represented on flood maps such as the proximity of water to structures on a property or the depth of the expected water during an extreme storm (not just a historic one). They were frequently combined with the use of FEMA Flood Maps to broaden the understanding of flood risk. One individual noted: “I bought my house and just looked at the FEMA maps [...].” In contrast, this individual's friends generally “relied on their realtor for that kind of information” (Department of History, 2022c, 35:19). Another participant noted that they sought out additional information from a trusted source, “I attended a seminar about flood insurance just this week from a gentleman, an engineer out of Baton Rouge, just working with the insurance companies” (Department of History, 2022b, 1:10:26). At the same time, participants also cited social media and their social circles as sources for seeking information about flooding, indicating a level of community engagement. Resources intended to communicate flood risk (e.g., National Weather Service, FloodFactor) were underrepresented in participant responses.

After asking participants about their prior use of tools and resources, we demonstrated a few examples of current hydroinformatic tools and resources available from different flood-prone regions of the US. These included static maps of flooded areas, location of schools in reference to flood zones, demographic information for impacted community areas, static 3-D visuals of flooded bridges, and illustrations of potential flood depths within a structure or home. Participants enjoyed visually appealing tools and resources, one participant referred to this type of information as “eye candy.” Elaborating further, the participant stated:

[Although] I really like flood area maps [as] I think they provide very specific and very clean information, if you're trying to convince people like politicians or someone like me of something, […] a beautiful presentation with animations [showing water rising or bridges going underwater] adds to the power. [I]f it's prettier, it's going to be more convincing to me and to a lot of, I think, millennial folks who are used to pretty animations with all of their video games (Department of History, 2022b, 1:21:10).

Participants offered helpful feedback on which elements of the demonstrated tools and resources they reviewed. Generally they appreciated more visual illustrations with human-centered impact rather than ones that provided extracted numerical metrics but with fewer visuals. They also identified the potential for implementing these types of tools in their community and suggested groups that would benefit from using them. While our demonstrated examples did not include information about real-time warnings and flood depths, some participants expressed those would be useful features to have access to.

Demonstrating these examples also revealed other challenges in the community that were not necessarily met by highly detailed flood information tools and resources. As expressed by one participant in referencing the community's ALICE population, or those who are asset limited, income strained, and employed (United for ALICE, 2020):

In 2016, you know, a lot of our most economically distressed communities did not flood. [...] And so in our community, we have a lot of people in the ALICE population who don't think they're that much of a flood risk and they're not doing anything differently in their lives because they didn't flood in '16 and they've never flooded before. [... It] would take a real community education campaign with real resources behind it to get people to think differently about their relative risk and what, if anything, they need to do about it. [I think] they have so many, real daily stressors about how they're going to make their rent payment or how they're going to make their utility payment, or how they're going to pay for their school supplies for their kid, [that] if they didn't flood in 2016, you're not going to be able to get them to worry about it unless you've got some overarching story (Department of History, 2022f, 01:22:39).

Overall, the feedback provided about current hydroinformatic tools and resources demonstrated in the focus groups was positive, with participants expressing the desire for more tools and resources that further met their expressed needs as well as a larger communication campaign to share information about flood risk and mitigation.

Conclusions and recommendations

Through a set of focus groups with various stakeholders with the Lafayette Parish community, the current study examined how community members understand their flood risk, as individuals and as a community, how they define their community in the context of flood risk, and how they perceive the need and effectiveness of flood mitigation efforts within their community. One of the key results that the current study revealed is that community members tend to understand flood risk based on their personal experience with past flood events and may lack a sense of the complicated facets of flood risk at a community level. This individualized perception of flood risk is mostly attributed to the lack of understanding of the causes of flooding and the interconnected flood dynamics across their immediate geographic circles. An individual-centric perception has also led to a multitude of community challenges such as: lack of awareness of elevated risk of under-resourced groups within the community; exclusion of certain populations from the definition of community; lack of trust between different stakeholders within the same community and across neighboring communities; disparity in understanding how the management of flood water across the region impacts individuals and the community as a whole; and conflicting views on the most effective flood mitigation strategies and projects that the community should pursue to reduce flood risk and impacts.

Overall, our study can help flood managers and community leaders in framing how they address and communicate flood mitigation in their community. This research suggests that helping individuals reconceive how they think about flooding will help them understand the mitigation needed at individual, community, regional, and state levels. This includes helping individuals broaden how they describe community to deepen their understanding of flood impacts. This potentially broader understanding of flood risk could be especially helpful as FEMA rolls out Risk Rating 2.0. The results of our study suggest that efforts for enhancing flood risk understanding and engaging the community in flood risk mitigation should take into account the social and economic backgrounds of different sectors within the community. Discussions with focus group participants also indicate that there is a critical need to address the existing disconnect, and sometimes distrust, between the public and the ongoing efforts by local government (flood officials) as well as the engineering and research communities.

The perspective we found on flooding during our focus group conversations provides a useful framework for designing tools and resources that address flood risk. This framework would help community stakeholders understand flood risk and improve their engagement in mitigation efforts. Because people understand flooding in relation to themselves, community members often have an incomplete understanding of connected flood experience. Similarly, individuals view their personal and community's flood risk and mitigation efforts through the lens of past flood experience. This goes for both individuals and for developers looking to expand the built environment. By improving communication about the scale of flooding beyond a parcel to subdivision, city, or broader region it can change the narrative about flooding in a community. Understanding the limitations of individual and community perspective on flooding can help inform the development of tools to address known gaps.

Tools and technologies have already been identified as useful avenues for addressing these known gaps (Mäkinen, 2006; Voinov et al., 2018). However, as evidenced in our focus group discussions, participants identified only a few tools related to flood risk. Any existing tools were used infrequently and often relegated to single or case-specific use. To address this problem, we suggest the following:

• that future flood information tools offer more scalable options that illustrate flood risk at individual (e.g., home or business), community (e.g., neighborhood or city), multi-regional context (e.g., parishes/counties or watersheds), in addition to national context;

• that scalable options include both the inclusion of local historic events (which serve as reference points for a community) and simulated events at multiple levels of community impact (that represent known or concerning alterations affecting community risk like potential development and climatic fluctuations);

• that scalable options also provide comprehensive community perspectives in scaling that allow individuals to see flood events affecting them individually, their social networks, the city, parish, and linked communities (such as a watershed) to better represent the connected nature of flood experiences and their causal factors;

• that scalable options also include ways for people to visualize and expand their knowledge beyond and connected to their homes/businesses/places of work, including factors that most affect their day-to-day lives such as commuting routes impacted by localized flooding, school and business closures, and accessibility to key emergency resources such as hospitals so that there is an incentive for repeated use and thus greater possibility for continued learning opportunities.

These additions may propel community members to repeatedly engage with flooding tools, increasing the opportunity for flood managers and community leaders to build wider interest in flood mitigation efforts and needs. They also will help widen individuals' understanding of the problems faced by those experiencing flooding across and connected to their communities and expand ideas of personal responsibility in mitigating flood risk in a community.

We strongly believe that more effective flood information and resources delivered through hydroinformatics technology, education, and continued community conversations can address some of the issues raised by our focus group participants in this study and that these findings can be applied to other communities facing flooding. For these reasons, we are continuing to solicit additional help from our community in reviewing current and future hydroinformatics technologies through a series of workshops held between May and August 2022.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are approved by the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Institutional Review Board and will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study involved human participants and was reviewed and approved by the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent for participation was required and provided for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

EH, LS, SB, AO, and BM contributed to the study conception and development. LS and AO coordinated and facilitated the focus groups. LS, AO, and EW performed the data analyses. ME and EH developed the maps. EW and AO made the tables and figure. LS, AO, and EW wrote the manuscript draft. LS, AO, EW, and EH revised the manuscript based on reviewer feedback. LS, AO, EW, EH, SB, ME, BM, and TD contributed to data collection, initial discussions about collected data, and contributed to pre-submission manuscript revisions. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was financially supported by a National Science Foundation Smart and Connected Communities Planning Grant (Award# 2125472)and the Guilbeau Charitable Trust. The substance and findings of the work are dedicated to the public. The authors and publisher are solely responsible for the accuracy of the statements and interpretations contained in this publication. Such interpretations do not necessarily reflect the view of the NSF.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the community members and organizations who participated in and helped advertise the focus groups.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bakkensen, L. A., and Barrage, L. (2021). Flood Risk Belief Heterogeneity and Coastal Home Price Dynamics: Going Under Water? Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online at: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23854/w23854.pdf.

Bixler, R. P., Paul, S., Jones, J., Preisser, M., and Passalacqua, P. (2021). Unpacking adaptive capacity to flooding in urban environments: social capital, social vulnerability, and risk perception. Front. Water 3:728730. doi: 10.3389/frwa.2021.728730

Capps, A. (2022). Lafayette sues St. Martin, corps of engineers over vermilion river spoil banks removal. Daily Advertiser. Available online at: https://www.theadvertiser.com/story/news/local/2022/03/24/lafayette-sues-st-martin-over-vermilion-river-spoil-banks-removal/7146795001/ (accessed August 9, 2022).

Department of History Kathleen Babineaux Blanco Public Policy Center, and Louisiana Watershed Flood Center. (2022h). Flood Focus Group 8 on March 3, 2022. University of Louisiana at Lafayette: Lafayette, LA.

Department of History Kathleen Babineaux Blanco Public Policy Center, and Louisiana Watershed Flood Center.. (2022a). Flood Focus Group 1 on January 13, 2022. University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA.

Department of History Kathleen Babineaux Blanco Public Policy Center, and Louisiana Watershed Flood Center. (2022b). Flood Focus Group 2 on January 21, 2022. University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA.

Department of History Kathleen Babineaux Blanco Public Policy Center, and Louisiana Watershed Flood Center. (2022c). Flood Focus Group 3 on January 27, 2022. University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA.

Department of History Kathleen Babineaux Blanco Public Policy Center, and Louisiana Watershed Flood Center. (2022d). Flood Focus Group 4 on February 3, 2022. University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA.

Department of History Kathleen Babineaux Blanco Public Policy Center, and Louisiana Watershed Flood Center. (2022e). Flood Focus Group 5 on February 4, 2022. University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA.

Department of History Kathleen Babineaux Blanco Public Policy Center, and Louisiana Watershed Flood Center. (2022f). Flood Focus Group 6 on February 11, 2022. University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA.

Department of History Kathleen Babineaux Blanco Public Policy Center, and Louisiana Watershed Flood Center. (2022g). Flood Focus Group 7 on February 17, 2022. University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA.

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2022). Risk Rating 2.0: Equity in Action. Available online at: https://www.fema.gov/flood-insurance/risk-rating (accessed August 24, 2022).

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2020). Louisiana Severe Storms and Flooding: DR-4277-LA. Available online at: https://www.fema.gov/disaster/4277 (accessed August 9, 2022).

Filatova, T., Parker, D. C., and Veen van der, A. (2011). The implications of skewed risk perception for a Dutch coastal land market: insights from an agent-based computational economics model. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 40, 405–423. doi: 10.1017/S1068280500002860

Habib, E., Miles, B., Meselhe, E., and Skilton, L. (2021). Louisiana Watershed Initiative Storage and Management Plan, Produced for Louisiana Watershed Initiative (LWI) based on Focus Group Interviews with Those Leading Louisiana's 8 Watershed Regions 2020–2021. University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA.

Haer, T., Husby, T. G., Botzen, W. J. W., and Aerts, J. C. J. H. (2020). The safe development paradox: an agent-based model for flood risk under climate change in the European Union. Glob. Environ. Change 60:102009. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.102009

Heal, E. N., and Watson, K. M. (2017). Flood Inundation Extent and Depth in Selected Areas of Louisiana in August 2016. Little Rock, AR: U.S. Geological Survey Data Release ver 1.1.

Johnson, K. A., Wing, O. E. J., Bates, P. D., Fargione, J., Kroeger, T., Larson, W. D., et al. (2020). A benefit–cost analysis of floodplain land acquisition for US flood damage reduction. Nat. Sustain. 3, 56–62. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0437-5

KATC (2022). Judge Orders Drainage Work Halted Until Case is Settled. KATC. Available online at: https://www.katc.com/news/lafayette-parish/judge-orders-drainage-work-halted-until-case-is-settled (accessed August 9, 2022).

Krueger, R. A., and Casey, M. A. (2014). Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 5th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Krueger, R. A., and King, J. A. (2005). Involving Community Members in Focus Groups. Thousand Oakes, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Kumar, P., Debele, S. E., Sahani, J., Rawat, N., Marti-Cardona, B., Alfieri, S. M., et al. (2021). Nature-based solutions efficiency evaluation against natural hazards: modelling methods, advantages and limitations. Sci. Total Environ. 784:147058. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147058

Lechowska, E. (2018). What determines flood risk perception? A review of factors of flood risk perception and relations between its basic elements. Nat. Hazards 94, 1341–1366. doi: 10.1007/s11069-018-3480-z

Littlejohns, P. (2019). Risk Rating 2.0: What Impact will America's New Approach to Flood Risk Have? NS Insurance. Available online at: https://www.nsinsurance.com/analysis/risk-rating-2-0-impact/ (accessed August 30, 2022).

Louisiana Office of Community Development Disaster Recovery Unit. (2017). State of Louisiana Proposed Master Action Plan for the Utilization of Community Development Block Grant Funds in Response to the Great Floods of 2016. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana Office of Community Development. Available online at: https://www.doa.la.gov/media/hxjmbnxv/floods-master-action-plan_clean_06jan17.pdf.

Mäkinen, M. (2006). Digital empowerment as a process for enhancing citizens' participation. E-Learn. Digit. Media 3, 381–395. doi: 10.2304/elea.2006.3.3.381

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. (1984). Qualitative Data Analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Mostafiz, R. B., Bushra, N., Rohli, R. V., Friedland, C. J., and Rahim, M. A. (2021). Present vs. future property losses from a 100-year coastal flood: a case study of Grand Isle, Louisiana. Front. Water 3:763358. doi: 10.3389/frwa.2021.763358

Mostafiz, R. B., Rohli, R. V., Friedland, C. J., and Lee, Y.-C. (2022). Actionable information in flood risk communications and the potential for new web-based tools for long-term planning for individuals and community. Front. Earth Sci. 10:840250. Available online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feart.2022.840250 (accessed August 24, 2022).

National Association of Realtors (2022). NAR Myth Buster: FEMA Risk Rating 2.0. National Association of Realtors. Available online at: https://www.nar.realtor/flood-insurance/nar-myth-buster-fema-risk-rating-2-0 (accessed August 30, 2022).

Saad, H. A., and Habib, E. H. (2021). Assessment of riverine dredging impact on flooding in low-gradient coastal rivers using a hybrid 1D/2D hydrodynamic model. Front. Water 3:628829. doi: 10.3389/frwa.2021.628829

Saad, H. A., Habib, E. H., and Miller, R. L. (2021). Effect of model setup complexity on flood modeling in low-gradient basins. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 57, 296–314. doi: 10.1111/1752-1688.12884

Sadiq, A.-A., Tyler, J., and Noonan, D. S. (2019). A review of community flood risk management studies in the United States. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 41:101327. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101327

Saldana, J. (2021). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 4th Edn. London: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Samenow, J. (2016). No-name storm dumped three times as much rain in Louisiana as Hurricane Katrina. The Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/capital-weather-gang/wp/2016/08/19/no-name-storm-dumped-three-times-as-much-rain-in-louisiana-as-hurricane-katrina/ (accessed August 9, 2022).

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research: Second Edition: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Terrell, D. (2016). The Economic Impact of the August 2016 Floods on the State of Louisiana. Baton Rouge: Louisiana Economic Development. Available online at: https://gov.louisiana.gov/assets/docs/RestoreLA/SupportingDocs/Meeting-9-28-16/2016-August-Flood-Economic-Impact-Report_09-01-16.pdf

Turk, L. (2022). Lafayette's ‘new pace' of government lands its drainage strategy in court. The Current. Available online at: https://thecurrentla.com/2022/lafayettes-new-speed-of-government-has-its-drainage-strategy-in-court/ (accessed August 9, 2022).

United for ALICE (2020). On Uneven Ground, ALICE and Financial Hardship in the United States. Morristown, NJ: United Way of Northern New Jersey. Available online at: https://www.unitedforalice.org/Attachments/AllReports/2020AliceReport_National_Final.pdf (accessed September 2, 2022).

U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019). State and County Employment and Wages. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available online at: https://www.bls.gov/cew/data.htm

Verlynde, N., Voltaire, L., and Chagnon, P. (2019). Exploring the link between flood risk perception and public support for funding on flood mitigation policies. J. Environ. Plann. Manage. 62, 2330–2351. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2018.1546676

Voinov, A., Jenni, K., Gray, S., Kolagani, N., Glynn, P. D., Bommel, P., et al. (2018). Tools and methods in participatory modeling: Selecting the right tool for the job. Environ. Model. Softw. 109, 232–255. doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2018.08.028

Wagner, G., and Barnes, S. R. (2022). “The Economy of Louisiana,” in The Party is Over: the New Louisiana Politics, eds C. L. Maloyed and P. Cross (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press).

Waldon, M. G. (2018). High Water Elevations on the Vermilion River During the Flood of August 2016. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323108783_High_Water_Elevations_on_the_Vermilion_River_During_the_Flood_of_August_2016 (accessed September 1, 2022).

Wang, Z., Wang, H., Huang, J., Kang, J., and Han, D. (2018). Analysis of the public flood risk perception in a flood-prone city: the case of Jingdezhen City in China. Water 10:1577. doi: 10.3390/w10111577

Watson, K. M., Storm, J. B., Breaker, B. K., and Rose, C. E. (2017). Characterization of Peak Streamflows and Flood Inundation of Selected Areas in Louisiana from the August 2016 Flood. Little Rock, AR: U.S. Geological Survey. doi: 10.3133/sir20175005

Wilson, B., Tate, E., and Emrich, C. T. (2021). Flood recovery outcomes and disaster assistance barriers for vulnerable populations. Front. Water 3:752307. doi: 10.3389/frwa.2021.752307

Wright, P. (2016). Louisiana Flood by the Numbers: Tens of Thousands Impacted. The Weather Channel. Available online at: https://weather.com/news/news/louisiana-floods-by-the-numbers (accessed August 9, 2022).

Appendix

Keywords: flood mitigation, community engagement, risk perception, flood communication, focus groups, hydroinformatics tools

Citation: Skilton L, Osland AC, Willis E, Habib EH, Barnes SR, ElSaadani M, Miles B and Do TQ (2022) We don't want your water: Broadening community understandings of and engagement in flood risk and mitigation. Front. Water 4:1016362. doi: 10.3389/frwa.2022.1016362

Received: 10 August 2022; Accepted: 07 September 2022;

Published: 04 October 2022.

Edited by:

Irfan Ahmad Rana, National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST), PakistanReviewed by:

Scott A. Hemmerling, The Water Institute of the Gulf, United StatesRobert V. Rohli, Louisiana State University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Skilton, Osland, Willis, Habib, Barnes, ElSaadani, Miles and Do. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Emad H. Habib, ZW1hZC5oYWJpYkBsb3Vpc2lhbmEuZWR1

†These authors share first authorship

Liz Skilton

Liz Skilton Anna C. Osland

Anna C. Osland Emma Willis

Emma Willis Emad H. Habib

Emad H. Habib Stephen R. Barnes

Stephen R. Barnes Mohamed ElSaadani

Mohamed ElSaadani Brian Miles

Brian Miles Trung Quang Do

Trung Quang Do