- Deparment of Psychology, School of Education and Psychology, University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain

The advent of affordable, high-quality virtual reality (VR) devices has revolutionized experimental research in cognitive psychology and neuroscience, offering more immersive and naturalistic environments for studying skills like spatial navigation. However, the increased incidence of cybersickness in VR may compromise its advantages, necessitating appropriate tools to assess this phenomenon and understand its impact on experimental outcomes. Despite the growing use of VR in research, there is a lack of consensus on the most effective methods for measuring cybersickness across different experimental modalities and over time. Here, we compared two cybersickness assessment tools: the widely-used Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ) and the more recent Cybersickness in VR Questionnaire (CSQ-VR). Using a maze navigation task, we examined how cybersickness is modulated by modality (Desktop vs. VR) and habituation (decrease in cybersickness between morning and afternoon sessions) in a gender-balanced, young Spanish sample (n = 26) with a within-subjects design. We also investigated potential predictors of cybersickness related to the task and individual differences. Our results demonstrate high internal consistency for both tools, performing particularly well in VR, and SSQ showing higher reliability in Desktop conditions. Robust mixed factorial analyses revealed small to moderate effects of modality (VR > Desktop) and habituation in both SSQ and CSQ-VR scores. Robust regression analyses indicated that SSQ scores were predicted by modality and habituation, while CSQ-VR scores were mainly predicted by modality and VR experience. These findings highlight that: 1) both SSQ and CSQ-VR are reliable tools for assessing cybersickness during navigation tasks, especially in VR; 2) VR-induced cybersickness decreases with task repetition without apparent impact on performance; and 3) other performance and individual differences do not predict cybersickness. Our study provides valuable insights for optimizing VR task design in experimental settings, contributing to the broader field of VR-based research methodology in cognitive science.

1 Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) used for the study of human cognition has gained significant traction in recent years (Kourtesis et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021), increasingly replacing traditional desktop or paper based solutions. This shift has been largely facilitated by the development and widespread availability of affordable VR systems. The growing preference for VR in navigational research in particular, is well-founded, as VR environments offer more naturalistic and ecologically valid settings for spatial navigation studies. Studies have shown that VR can provide a higher degree of environmental realism, allowing for more accurate representations of real-world spaces and potentially leading to more generalizable results, along with spatial learning and transfer to the real world (Hejtmanek et al., 2020). VR features such as a wider field of view, greater sensorimotor affordances or the possibility of locomotion (natural walking, joystick or gesture-based movement) promote a more embodied form of spatial navigation (Jeung et al., 2023) not available in desktop setups. This form of embodiment along with rich and interactive environments, combined with the ability to manipulate and control environmental variables with precision, enable experiences that more closely mimic real-world navigation experiences, making VR an attractive tool for spatial cognition research.

However, contrary to what one would expect, studies comparing task performance between VR and desktop setups have often found no significant differences in navigational efficiency or spatial learning outcomes (Carbonell-Carrera et al., 2021; Clemenson et al., 2020; Hejtmanek et al., 2020; Feng et al., 2022; Zisch et al., 2024). Other studies show mixed results, where VR might indeed improve navigation (Ruddle and Lessels, 2006), while in some other cases, desktop interfaces have even outperformed VR in certain spatial learning tasks, particularly when ambulatory locomotion is restricted in VR setups (Zhao et al., 2020; Srivastava et al., 2019). A possible explanation for these inconsistent findings is the higher incidence of cybersickness in VR environments (Yildirim, 2020; Sharples et al., 2008; Rebenitsch and Owen, 2016).

Cybersickness (CS) is a well-documented phenomenon in VR environments, characterized by symptoms such as nausea, disorientation, and discomfort. It is highly prevalent, with studies reporting that up to 60 percent of users experience symptoms within 10 min of VR exposure (Garrido et al., 2022; Mittelstaedt et al., 2018). A leading explanation is the sensory conflict theory, which posits that the mismatch between visual motion cues (vection) and the absence of corresponding physical movement leads to discomfort (Reason, 1978; Keshavarz et al., 2015), particularly in stationary navigational tasks where users perceive movement without actual locomotion. The evolutionary hypothesis complements this by suggesting that such sensory conflicts mimic the effects of neurotoxins, triggering protective physiological responses like nausea to expel perceived toxins (Treisman, 1977) or even a “defensive hypothermia” (Nalivaiko et al., 2014). Additionally, the postural instability theory attributes CS to difficulties in maintaining postural control, with prolonged instability during VR exposure exacerbating symptoms (Riccio and Stoffregen, 1991). These theories likely interact, highlighting the complex interplay of perceptual, physiological, and motor factors in cybersickness and underscoring the need for integrative mitigation strategies.

Several studies have shown the negative impact of cybersickness on cognitive and motor task performance while in VR (Voinescu et al., 2023; Sepich et al., 2022; Kourtesis et al., 2023a), including spatial learning and navigation tasks. Research has shown that cybersickness can lead to decreased spatial orientation abilities and impaired navigation performance in virtual environments (Maneuvrier et al., 2023), as well as limit the duration of VR experiences (Martirosov et al., 2022). This decline in performance can potentially compromise the validity and effectiveness of VR-based spatial cognition studies.

Several factors modulate cybersickness intensity in navigational tasks. Task design elements such as duration of exposure, movement speed, and locomotion type play crucial roles. For instance, longer exposure times and faster movement speeds in virtual environments tend to exacerbate cybersickness symptoms (Dużmańska et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2020). Regarding locomotion type, while joystick-based movement or teleportation tend to induce higher levels of cybersickness (Clifton and Palmisano, 2020; Buttussi and Chittaro, 2018) room-scale or natural walk, elicits low levels of cybersickness at the expense of having to have enough physical space to walk around (Mayor et al., 2021). Individual factors also contribute to cybersickness susceptibility, with prior gaming experience generally associated with reduced symptoms, while individuals prone to motion sickness typically experience more severe cybersickness (Kourtesis et al., 2024).

A habituation effect can be found after repetitive exposure to VR, where cybersickness symptoms reduce over time (Gavgani et al., 2017; Dużmańska et al., 2018). However, this reduction might not generalize to different tasks or games (Palmisano and Constable, 2022). These findings are particularly important for longitudinal studies, where different levels of cybersickness—and their effects on the task—can be expected, but also for the case of participants with no prior VR experience, who tend to experience more severe symptomatology (Luong et al., 2022) and may benefit from “pre-exposition” to VR prior to the task (Domeyer et al., 2013).

When comparing cybersickness between desktop and head-mounted display (HMD) VR setups, studies have consistently found higher incidences and more severe symptoms in VR environments (Martirosov et al., 2022; Yildirim, 2020; Sharples et al., 2008). Researchers attribute this difference to the increased immersion and wider visual field of view in VR, which can intensify vection and sensory conflicts. However, the extent of this difference can vary depending on the specific task design and individual user characteristics.

Given these findings, it is crucial to consider cybersickness when designing navigational tasks in VR. Researchers should carefully balance the need for ecological validity with the potential for cybersickness, implementing appropriate measurement tools and mitigation strategies to assess and reduce its impact on performance. By accounting for cybersickness, researchers can better isolate the effects of their experimental manipulations from those induced by discomfort, leading to more reliable and valid results and interpretations in spatial cognition studies.

The Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ) (Kennedy et al., 1993) has long been the most widely used tool for measuring cybersickness in both virtual reality and desktop setups. Its widespread adoption has allowed for comparisons across different studies and experimental conditions. However, in recent years, the psychometric properties of the SSQ have been questioned, particularly when applied to VR environments (Sevinc and Berkman, 2020; Bimberg et al., 2020; Kourtesis et al., 2023b). Critics argue that the SSQ, originally designed for flight simulators, may not adequately capture the unique aspects of cybersickness experienced in VR settings, such as HMD ergonomics.

To address these limitations, researchers have developed VR-specific alternatives. One such tool is the Virtual Reality Sickness Questionnaire (VRSQ) which was derived from the SSQ and introduced as a more targeted tool for assessing cybersickness in VR environments (Kim et al., 2018). More recently, Kourtesis et al. (Kourtesis et al., 2019; 2023b) developed the Cybersickness in Virtual Reality Questionnaire (CSQ-VR), which has shown superior psychometric properties compared to both the SSQ and VRSQ. The CSQ-VR has even been used in conjunction with physiological measures, such as pupil size, which has been found to be a significant predictor of cybersickness (Kourtesis et al., 2024).

It is crucial to use the appropriate tool for the specific task modality, whether it be VR or desktop-based. Using a VR-specific questionnaire like the VRSQ or CSQ-VR for VR tasks, and the SSQ for desktop setups respectively, may ensure a more accurate measurement and interpretation of cybersickness symptomatology. This precision is key for exploring how cybersickness influences task performance and for making valid comparisons across different experimental conditions. By employing the most suitable assessment tool, researchers can better isolate the effects of cybersickness and other experimental variables on navigational performance and other cognitive processes, leading to more reliable and actionable insights in spatial cognition studies.

In light of the growing use of VR in spatial navigation research, it is important to understand the impact of CS on task performance and user experience. While VR offers enhanced immersion and ecological validity for navigational tasks, it also presents challenges related to CS that are less prevalent in traditional desktop setups. The literature highlights the complex interplay between task modality, CS intensity, and performance outcomes in spatial cognition studies. Furthermore, the measurement of CS itself has evolved, with new VR-specific tools challenging the long-standing dominance of the SSQ. Given these considerations, our study aims to address critical gaps in understanding CS in navigational tasks across different visual immersion modalities, explore potential habituation, performance and individual effects, and evaluate the efficacy of two CS measurement tools. This research will contribute to developing more robust methodologies for VR-based spatial cognition studies and inform best practices for mitigating CS in experimental designs.

By using a controlled within-subject (modality-randomized, and sex-balanced) design, we focus on the following objectives: 1) to study how task performance in a virtual maze task (VMT) is modulated by immersion level (Desktop vs. VR) and to assess learning effects between two same day sessions (AM vs. PM); 2) to compare the psychometric properties of the SSQ and the CSQ-VR for the VMT in both Desktop and VR modalities; 3) to examine the impact of immersion level and the presence and extent of habituation (AM vs. PM sessions) in a VMT on perceived CS scores (SSQ and CSQ-VR); and 4) to explore the relationship between CS scores and individual predictors (demographic, VMT-related variables).

Based on previous findings, we hypothesize that (1) performance in the VMT will not differ between modalities while observing intraday learning; (2) the CSQ-VR will show better psychometric properties compared to the SSQ in assessing CS for the navigational task in the VR modality; (3) exposure to the VMT in the VR modality will lead to higher CS scores compared to Desktop; (4) a habituation effect to CS will be observed in both Desktop and VR modalities; and (5) higher CS scores will be associated with lower performance in the navigational task in both modalities. These objectives and hypotheses aim to contribute to understanding cybersickness in navigational tasks across different modalities and the effectiveness of various assessment tools, ultimately informing the design of more comfortable and effective VR experiences.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

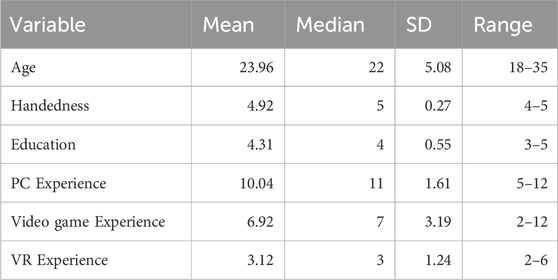

This study was approved by the University of Navarra Ethics Committee (project ID: 2022.090mod). To be eligible for the study, participants had to be between 18 and 35 years old and not have a history of neurological or psychiatric diagnoses. As part of our demographics questionnaire, we were interested in asking about sex, education (5-item Likert scale), handedness (5-item Likert scale) and experience using a computer, playing video games and VR. Experience was measured by adding the scores from two question (6-item Likert scale) assessing skill and frequency when using such devices, as done in previous studies (Kourtesis et al., 2023b; a). Our sample (Table 1) included a total of 26 participants including 13 females (13 males) with a mean age of 23.96 (SD = 5.08) years old. They were all mostly right-handed (24 use always their right hand) and highly educated (most have completed or are studying a university degree). Participants reported extensive PC use, with a mean score of 10.04 out of 12 (median 11). Video game experience was moderate, averaging 6.92 out of 12 (median 7), with a wide range from 2 to 12. VR experience was relatively low, with a mean of 3.12 out of 12 (median 3), ranging from 2 to 6.

2.2 Hardware

Our VR setup included a Meta Quest 2 head mounted display (HMD) with a horizontal field of view (FOV) of 89

2.3 Materials

2.3.1 Virtual maze task

The Virtual Maze Task (VMT) presented in this study is a reproduction of a 3D maze used in prior research (Murphy et al., 2018; Wamsley et al., 2016; Stamm et al., 2014) but now adapted for its use on both Desktop and VR. In short, it consists of alleys, squares and dead ends filled with two types of landmarks (palm trees and floor lights, see Figure 1). Participants move from an egocentric point of view (arrow keys for Desktop; head movement and right control trigger to move forward for VR). The main objective is to exit the maze as quickly as possible. First, participants go through a 5-min Adaptation phase where they are put in a smaller environment for them to learn the controls and familiarize themselves with the maze and landmarks. Then, for another 5 min, the participants go through the Training phase, where they spawn next to the exit and are instructed to explore the maze and try to learn the route that leads to the exit. Finally, participants attempt to exit the maze in 3 trials during the Trial phase. In each trial, participants spawn at one of the three starting points in a counterbalanced fashion (starting points are equidistant from the exit, see Supplementary Figure S1). Each trial was concluded when participants found the exit door or when the time limit of 10 min was reached. Including all phases, each session could last up to 40 min. A video demonstration is available online1 and in the Supplementary Material. For a more detailed description of the VMT, please refer to (Eudave et al., 2023).

Figure 1. Virtual Maze Task. Top left: layout (top-view) of the rendered 3D maze (participants were not shown this image). Top right: In-game egocentric (first person) view of the VMT showing the two types of landmarks (palm tree and floor light) and the exit door. Bottom left: VR modality. Bottom right: Desktop modality.

In both sessions, performance metrics associated with the VMT were assessed using three measures: completion time (measured in seconds to reach the exit), distance traveled (measured in units to reach the exit), and speed (measured as distance traveled divided by completion time), assessed for each of the three trials.

Since continuous locomotion techniques with mismatched stimuli (e.g., joystick-based movements) tend to cause higher scores in CS while in VR (Caserman et al., 2021), we employed two techniques that have been proven to reduce, at least partially, symptoms of CS (Lin et al., 2020; Rouhani et al., 2024; Groth et al., 2021). Peripheral blurring and field of view (FOV) occlusion were implemented in the VR modality during rotations and translational movement, adjusted according to the intensity and duration of movement, with greater blur and occlusion applied during rapid rotations and/or forward movement. Only peripheral blurring was applied to the Desktop modality.

2.3.2 Simulator sickness questionnaire

The Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ) is a self-report questionnaire originally designed to assess simulator sickness, a phenomenon with symptoms similar to motion sickness, but often less severe and triggered by elements of visual displays and sensory conflicts not typically present in real-world environments that cause motion sickness. The SSQ was adapted from the Pensacola Motion Sickness Questionnaire (MSQ), a tool used to measure motion sickness in various settings, including flight simulators (Kennedy et al., 1993).

The SSQ consists of 16 symptoms that are grouped into three categories: Nausea, Oculomotor, and Disorientation. After experiencing a virtual environment, participants rate the severity of each symptom on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not experienced) to 3 (severe). To determine the severity for each category, the responses for corresponding symptoms are summed and then multiplied by a predefined scaling factor for each subscore. A total score is calculated by summing the weighted subscores of all three categories. For our sample, a Spanish-adapted version of the SSQ was used (Campo-Prieto et al., 2021). The questionnaire, along with the formulas used for calculating scores, can be found in the Supplementary Material.

2.3.3 Cybersickness in VR questionnaire

The Cybersickness in VR Questionnaire (CSQ-VR) is a tool designed to measure the presence and intensity of cybersickness symptoms experienced in virtual reality (VR) (Kourtesis et al., 2023b). The CSQ-VR is an adapted and enhanced version of the VR Induced Symptoms and Effects (VRISE) section of the Virtual Reality Neuroscience Questionnaire (VRNQ) (Kourtesis et al., 2019).

The CSQ-VR is a 7-point Likert scale consisting of six questions that assess three types of cybersickness symptoms: Nausea, Vestibular, and Oculomotor. Each symptom category has two corresponding questions. Participants rate the presence and intensity of each symptom on a scale ranging from “1 - absent feeling” to “7 - extreme feeling”. The CSQ-VR produces a total score, which is the sum of the three subscores, with a maximum score of 42 (14 for each subscore).

Since the CSQ-VR is not available in Spanish, we followed the recommendations from the International Test Commission (ITC). First, two independent translators fluent in both English and Spanish (native) translated the questionnaire from Spanish to English, and then compared and reconciled differences between them. This version was reverse-translated by two different translators, who were fluent in both languages, and native English speakers. This version was compared to the original English version to identify discrepancies or nuances that may have been lost or altered in translation. Finally, a committee formed by the translators and authors of this paper reviewed the translated and back-translated versions to ensure semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence between the original and adapted versions. The resulting Spanish adaptation of the CSQ-VR is available in Supplementary Material.

2.4 Experimental design

This study employed a 2 × 2 within-subjects design with Modality (Desktop vs VR) and Session (AM vs PM) as repeated measures. In each session, participants completed three trials of the VMT. For each session, performance metrics were averaged from the three trials, whereas cybersickness (CS) measures were evaluated by using the difference between POST and PRE VMT exposition scores on the SSQ and CSQ-VR, respectively (e.g., to account for non-experimental CS symptoms). This design allowed for the analysis of modality effects, spatial learning (via performance variables), and CS habituation over time, assessed by two different tools.

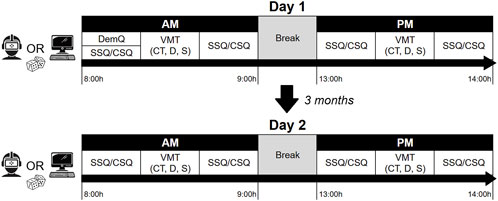

2.5 Procedure

For each participant, the study spanned 2 days (Day 1 and Day 2, one for each modality), each with two (AM and PM) sessions. Participants were pseudorandomly assigned to either the Desktop or Virtual Reality (VR) modality of the VMT using stratified permutation block randomization to ensure an equal number of participants started with the VR/Desktop modalities and that male and female participants were equally distributed. Ultimately, 14 participants began with the VR modality, and 12 began with the Desktop modality. On Day 1, participants arrived at 8:00 AM for the morning (AM) session. After providing informed consent, they completed a demographics questionnaire and the PRE assessments of SSQ and CSQ-VR. POST-assessments of SSQ and CSQ-VR were completed after the VMT. The afternoon (PM) session occurred at 1:00 PM, following the same procedure without the demographics questionnaire. Each session lasted approximately 45 min. Day 2, conducted 3 months later to prevent learning transfer, followed the same procedure with the alternate modality (Desktop or VR). The entire protocol is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Experimental procedure. Modality was pseudorandomized on Day 1. AM, Morning session; PM, Afternoon session; DemQ, demographics questionnaire; SSQ, Simulator Sickness Questionnaire; CSQ-VR, Cybersickness in VR Questionnaire; VMT, Virtual Maze Task; CT, Completion time; D, Distance; S, Speed.

2.6 Data analysis

All the statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.1.1 (R Core Team, 2021). First, we obtained the descriptive indicators (mean, median, SD, range) of performance metrics and CS information related to the VMT of the sample. To assess for internal consistency in CS scores, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were obtained from SSQ and CSQ-VR total score and subscores for each modality and session. As the SSQ is considered the gold standard, evidence of convergent validity of the Spanish-adapted version of the CSQ-VR was assessed using Spearman’s correlation analyses with the SSQ scores. The temporal stability of measures was analyzed by calculating the Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) between Day 1 and Day 2 morning’s PRE assessments.

Considering the distribution of the dependent variables, non-parametric (robust) statistical analyses were employed for hypothesis testing. First, we used robust mixed factorial analyses to assess the effect of Modality (Desktop vs VR) and Session (AM vs PM) on VMT performance metrics (completion time, distance traveled, and speed), and on CS symptoms (SSQ and CSQ-VR total and category scores) by using the WRS2 (Mair and Wilcox, 2020) package. For each dependent variable, we conducted 2 × 2 within-subjects analyses using the bwtrim function. This function performs robust repeated-measures ANOVAs using trimmed means, which are less sensitive to extreme values compared to traditional approaches. The lincon function was used for post hoc pairwise comparisons, which was one-sided for the CS analyses, under our hypothesis (VR

To identify the best predictors of CS (measured by the SSQ and CSQ-VR) associated with the VMT while considering the within-subject design of the study, Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) with a Tweedie distribution and a log link function were set using the glmmTMB (Brooks et al., 2017) package. Categorical predictors (e.g., modality, session, gender) were converted to factors for proper models’ handling. Continuous predictors such as age, distance, speed, and time were standardized (mean-centered and scaled) to improve model convergence and interpretation. A full GLMM was fitted for each dependent variable using a Tweedie distribution. The Tweedie distribution was chosen in these models to account for the right-skewed distribution of SSQ and CSQ-VR total and sub-factor scores. The models’ formula incorporated the main effects of Modality, Session (fixed factors), and additional individual variables such as age, gender, handedness, education, PC, VR, and video game experience, and performance variables (completion time, distance, and speed). A random intercept for participants was included to account for within-subject variability. A null model, including only the intercept and the random effect of participants, was used as a baseline for the models’ comparison. The full model was compared to the null model using a likelihood ratio test, proving whether the inclusion of predictors significantly improved the model fit. All models were evaluated using AIC, BIC, and R2 values. AIC and BIC were used to assess the goodness of fit, with lower values indicating better models. Marginal and conditional R2 values were calculated to explain the variance attributable to fixed effects. Significant predictors (p-value

3 Results

3.1 Performance metrics

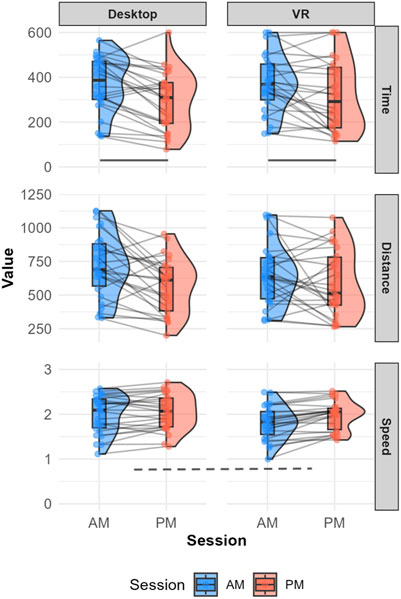

In an average across modalities and sessions, participants’ completion time was between 296 and 373 s (5–6 min), traveling a distance between 567 and 719 in-game meters at a speed of 1.81–2.05 m/s. These parameters are similar to those obtained in previous studies using the VMT (Wamsley and Stickgold, 2019; Wamsley et al., 2016; Nguyen et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2018), especially after considering that our study included subjects with no video game experience (exclusion criteria in some of these studies). A summary of performance-associated values across Desktop and VR modalities and AM and PM sessions can be found in Figure 3 and Supplementary Tables S1, S2.

Figure 3. Comparison of performance metrics (Completion time, Distance, and Speed) between Modality (Desktop and VR) across morning (AM) and afternoon (PM) sessions. Each plot displays the distribution of values for the respective metric using both box plots and density curves, with individual data points connected between sessions. Dashed line: Significant main effect of Modality. Solid line: Significant main effect of Session.

Regarding completion time, factorial analysis showed a significant main effect of Session, with neither main effect of Modality nor Modality*Session interaction. Post-hoc analyses revealed that participants took significantly more time to complete the task during the AM session compared to the PM session (psihat = 84.779, 95% CI [20.473, 149.083], p = 0.011), with an estimated difference of about 85 s, resulting in a small (delta = 0.283, 95% CI [0.077, 0.466]) effect of Session.

Factorial analysis of distance showed an effect of Session that was not statistically significant, but approached statistical significance (p = 0.0517). No significant effects were observed for Modality or the Modality*Session interaction.

Factorial analysis of speed revealed a significant effect of Modality, without effect of Session nor Modality*Session interaction. However, post hoc analyses indicated that the difference between Modality conditions was non-significant. This result suggests that while there was a trend towards higher speed on Desktop compared to VR, it did not reach the conventional threshold for statistical significance.

In summary, performance metrics results suggest no differences between modalities but a small but significant difference in completion time between AM and PM sessions, suggesting that learning might occur already after the first session.

3.2 Cybersickness measures

Visual inspection of item, category, and total score distributions revealed heavy right-tailed distributions for all items and sub-factors in both tools, modalities, and sessions. This suggests that most participants had no or low CS symptom intensity after the VMT exposition (see Supplementary Figures S2–S5).

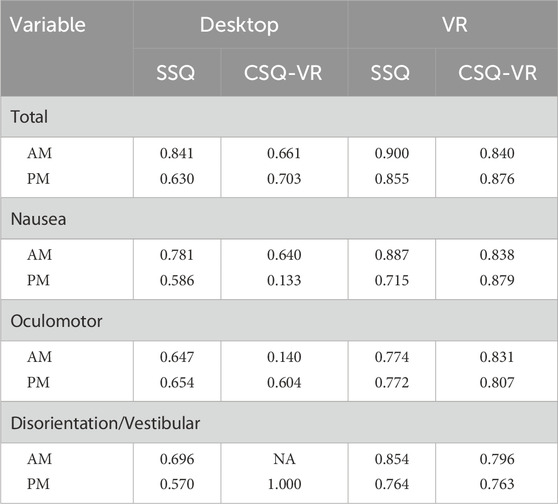

3.2.1 Reliability

The internal consistency of CS tools for both modalities and sessions are reported in Table 2. Desktop SSQ scores mostly showed values of internal consistency close, but below the recommended standard [Cronbach’s alpha

Significant high correlations between tools were found in all total score and subscores, except for PM’s Nausea and Disorientation/Vestibular in the Desktop modality (Supplementary Table S7). Additionally, significant ICC were found only for the SSQ in total, Nausea and Oculomotor subscores (Supplementary Table S8). In summary, VR scores show acceptable internal consistency in both tools, with Desktop in the SSQ showing slightly lower alpha values, while probably not being as reliable in the CSQ-VR. We also found evidence of convergence between both tools and 3-month temporal stability was only found in the SSQ total, Nausea, and Oculomotor subscores.

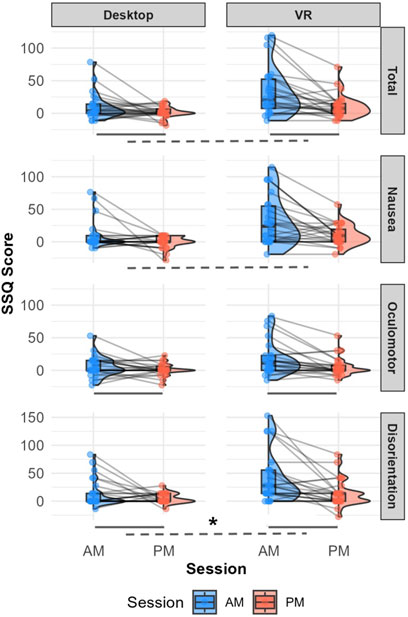

3.2.2 Effect of modality and session on SSQ

In general, SSQ total score and subscores were always higher in POST exposure, a difference that diminished between the morning and afternoon sessions. VR modality showed higher scores, similar to those found in other studies using navigation in VR, but also showed reductions in the afternoon session. A summary of PRE-POST scores across modalities and sessions can be found in Supplementary Table S3.

For total SSQ scores (Figure 4), the factorial analysis showed significant effects of Modality and Session, while the interaction between Modality and Session was marginally non-significant (Supplementary Table S4). Post-hoc comparisons indicated that VR elicited significantly higher total SSQ scores than Desktop condition (psihat = −10.519, 95% CI [−17.602, −3.435], p = 0.002; delta = −0.344, 95% CI [−0.532, −0.124]). Additionally, participants reported significantly higher total SSQ scores in the AM compared to the PM session (psihat = 8.766, 95% CI [1.22, 16.311], p = 0.012; delta = 0.283, 95% CI [0.06, 0.48]).

Figure 4. Comparison of SSQ total and factor scores between Modality (Desktop and VR) across morning (AM) and afternoon (PM) sessions. Each plot displays the distribution of values for the respective metric using both box plots and density curves, with individual data points connected between sessions. Dashed line: Significant main effect of Modality. Solid line: Significant main effect of Session. Asterisk: Significant Modality × Session interaction.

At the category level, the Nausea subscore analysis revealed a significant effect of Modality, with VR resulting in significantly higher Nausea subscores than Desktop, with a small effect size. For the Oculomotor subscore, significant main effects were found for both Modality and Session. Post-hoc comparisons showed that Modality was not statistically significant, but significantly higher Oculomotor subscores were observed in the AM compared to the PM session. The Disorientation subscore analysis yielded significant main effects of Modality and Session and a significant Session*Modality interaction. Specifically, PM decreases in disorienting symptoms were greater in VR than in Desktop.

These results suggest that the habituation effect (PM < AM) is mostly influenced by oculomotor symptomatology, and VR increases in SSQ scores are related to all subscores.

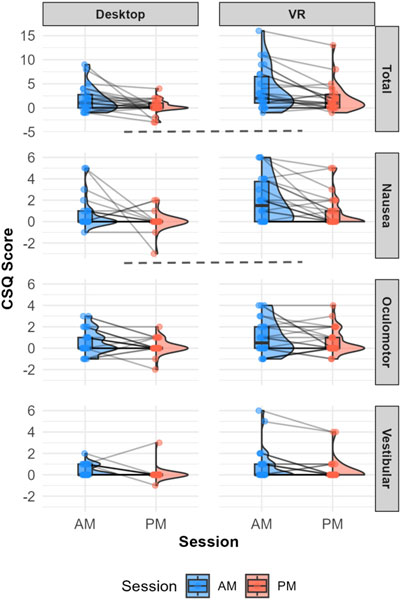

3.2.3 Effect of modality and session on CSQ-VR

As with the SSQ, CSQ-VR scores and subscores were always higher POST exposure, and in the VR modality. However, while present, afternoon reductions across modalities were more nuanced, being relatively smaller when compared with the SSQ. While the CSQ-VR has not been utilized to examine CS in other navigation tasks, values obtained here are lower than those registered in a CS-inducing VR experience (Kourtesis et al., 2023b). A summary of PRE-POST scores across modalities and sessions can be found in Supplementary Table S5 and Figures 4, 5.

Figure 5. Comparison of CSQ-VR total and factor scores between Modality (Desktop and VR) across morning (AM) and afternoon (PM) sessions. Each plot displays the distribution of values for the respective metric using both box plots and density curves, with individual data points connected between sessions. Dashed line: Significant main effect of Modality and post hoc (VR

Factorial analysis of the CSQ-VR total score revealed a significant effect of Modality on participants’ reported symptoms (Figure 5; Supplementary Table S6). Post-hoc comparisons indicated VR condition elicited significantly higher total CSQ-VR scores than Desktop (psihat = −1.187, 95% CI [−2.151, −0.224], p = 0.0084; delta = −0.336, 95% CI [−0.516, −0.127]).

Examining the CSQ-VR subscores, only the Nausea subscore analysis revealed a significant main effect of Modality. Post-hoc comparisons showed significantly higher Nausea subscores in the VR condition, with a medium effect size. For the Oculomotor and Vestibular subscores, no significant main effects or interactions were found.

These results indicate that only Modality (VR

3.3 Predictors of cybersickness measures during spatial navigation

In our study, we employed GLMMs to investigate the factors influencing cybersickness symptoms measured by the SSQ and CSQ-VR. The models included fixed effects for Modality, Session, and their interaction, along with relevant covariates (individual and performance variables), where random intercepts for participants were included to account for repeated measures.

Results revealed that only three out of eight dependent variables were consistently predicted in these models (Supplementary Table S9). Specifically, Modality (VR) and Session (PM) were significant predictors of the SSQ total score, explaining approximately 26.5% of the variance in the outcome. Modality alone accounted for 15.1% of the variance in total SSQ, whereas Session accounted for 13.9%. The SSQ Oculomotor subscore was also significantly predicted by Modality, explaining 6.6% of its variance, indicating that VR modality led to significantly higher SSQ oculomotor symptoms compared to Desktop. Finally, Modality (VR) and VR experience were found to predict CSQ-VR Nausea subscores, explaining 20.3% of their variance. For further information, pair-wise correlations between predictors and predictive variables are available in Supplementary Figure S6.

Considering the impact of Modality and Session on SSQ and CSQ-VR total scores, separated exploratory models were established to examine their impact (that is, by modeling their separated effects and their interaction with predictors, and comparing this result against a model without modeling interaction). This exploratory analysis did not result in a significantly better fit in the models with interactions, suggesting that Modality and Session did not have a moderating effect over one or more of the predictor variables on CS scores.

4 Discussion

This study examined how cybersickness in a navigation task is modulated by task performance, task design choices (modality, repetition) and individual differences. Our goal was to delineate the advantages and challenges of transitioning traditionally Desktop-based navigation tasks into VR environments.

In terms of Performance, participants in the Desktop modality showed an overall slight increase in speed while moving in the VMT, along with improved completion times in the PM session. Both the SSQ and CSQ-VR questionnaires demonstrated good internal consistency, especially in the VR condition. However, this consistency tended to decrease with continued administrations. Participants generally experienced higher cybersickness -as measured by both the SSQ and CSQ-VR-in the VR condition, with participants showing habituation to the task and significantly experiencing less CS in the PM session.

4.1 Navigating is slower in VR, and completion times improve between sessions

The analysis of performance metrics revealed small but statistically significant effects of Modality and in intraday learning. When in VR, participants moved slower than those in the Desktop modality. However, there was no advantage of using VR in terms of completion time or distance, metrics frequently used to measure wayfinding or navigational ability, despite displaying a more naturalistic environment. This is consistent with several other studies showing that neither spatial orientation (Carbonell-Carrera et al., 2021), wayfinding (Feng et al., 2022) or spatial learning (Zhao et al., 2020; Srivastava et al., 2019) are improved when using VR. Perhaps VR’s benefit for navigation, or spatial learning more generally, resides in its ability to transfer learning to the real world (Hejtmanek et al., 2020; Clemenson et al., 2020; Mayrose and Maidenbaum, 2024; Khan et al., 2024). Additionally, VR allows examination of how body-based cues, natural locomotion or other locomotion-related behaviors like eye-gaze or head movements (not possible with Desktop experiences) improve navigation (Huffman and Ekstrom, 2021).

On the other hand, participants were faster in finding the maze’s exit during the afternoon session compared to the morning sessions. This indicates that learning took place over trial repetition, influencing how long participants took to complete the task. This difference, while consistent, was relatively small in magnitude. However, this gain in completion time did not come with significant decreased distance and increased speed over time. The observed improvement in completion times was comparable to findings from studies that have used the VMT with a similar experimental setup (Wamsley and Stickgold, 2019; Wamsley et al., 2016; Nguyen et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2018), suggesting that our adaptation of the VMT may be capable of measuring the same construct as in the original maze, but now also in VR.

4.2 Just like the SSQ, the CSQ-VR is a valid and reliable tool to measure cybersickness in spatial navigation, but only in VR

One strength of our study lies in its thorough psychometric evaluation of both SSQ and the CSQ-VR. By demonstrating high internal consistency in VR conditions, particularly with the SSQ, the findings underscore the reliability of these tools in capturing CS symptoms in immersive environments. However, we identified a key limitation in the reduced reliability of both tools when applied in Desktop conditions. The reduced variability in item scoring (due to less CS) led to lower reliability in both tools, especially for the CSQ-VR. Additionally, while both tools showed high convergence between them, only the SSQ revealed temporal consistency in their measurements.

This has implications for the experimental design of CS-inducing tasks or virtual experiences. When studying CS and its effects in a given task, we suggest that, if the researcher’s goal is to compare findings to a large body of existing literature, do a longitudinal study or examine if/how CS is associated with other individual or task-related variables, the SSQ might be more appropriate. Although the SSQ could be enhanced by changing its factor structure (Bouchard et al., 2021; Bruck and Watters, 2011) or by incorporating VR-related discomfort items [digital eye-strain, ergonomics (Hirzle et al., 2021)] it remains a valuable and informative tool for quantifying cybersickness, especially when researchers prioritize consistent administration and scoring methods, and interpret the results with caution.

However, if the researcher’s focus is on the bare detection of VR-specific symptoms, ease of administration, and interpretation, the CSQ-VR might be the better choice. Another advantage of this tool’s format is that it can be administered in real-time while immersed in a VR experience (Kourtesis et al., 2023b). This can potentially provide a more accurate measurement of CS without overly impacting the flow of the VR task or experience. It is important to remember that the CSQ-VR is a relatively new tool and requires further validation across diverse VR applications, settings and user populations.

4.3 VR induces more intense symptoms of CS and habituation is present in both modalities

As expected, the VR modality elicited higher cybersickness scores in the VMT. This finding aligns with studies comparing cybersickness across different display systems consistently show that VR headsets, particularly HMDs, induce more severe symptoms than desktop setups or less immersive VR systems. The increase in our study’s total SSQ scores and subscores in the VMT in VR are similar to those reported in similar navigational tasks (Aldaba et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2020; Venkatakrishnan et al., 2024a) or tasks where locomotion was controlled using a joystick (Saredakis et al., 2020), as it was in our experiment. This is likely due to the heightened sensory immersion and greater potential for sensory conflicts inherent in VR technology. The VMT, involving virtual forward movement to navigate a virtual maze while seated, likely exacerbated these sensory conflicts, as discrepancies between visual and vestibular cues are known to be major contributors to cybersickness, particularly nausea and disorientation. This interpretation is supported by the significant main effect of Modality on the Nausea and Disorientation subscores, indicating a pronounced impact of these symptom categories when navigating in VR. The CSQ-VR showed a similar pattern, where an increase in overall CS in the VR modality appears to be mostly determined by an increase in nausea symptoms.

We found that both VR and Desktop modalities showed a habituation effect. Lower cybersickness SSQ total scores were reported in the PM session compared to the AM session, mainly driven by a decrease in oculomotor symptoms. Consistent with previous research and corroborated by our findings, it is possible that simply repeated exposure allows the nervous system to adapt to the sensory conflicts that initially trigger CS symptoms (Dużmańska et al., 2018), in this case, ameliorating symptoms like eye-strain, fatigue or headache. These findings reinforce the idea that, to reduce CS incidence, researchers should consider incorporating repetition through task acclimation (Domeyer et al., 2013). By using an acclimation session, participants (especially those VR-naive) gradually get exposed to sensory conflicting stimuli (i.e., vection) and help reduce CS symptoms. While our study demonstrated that habituation is possible within the same day, this process might benefit from a longer delay between sessions or time with no exposure between acclimation and the actual task (Howarth and Hodder, 2008; Domeyer et al., 2013). However, depending on the procedure or task design, this implementation might not be cost-effective (Keshavarz et al., 2015).

Unlike inter-modality effects between tools, habituation effects could not be replicated when assessing CS with the CSQ-VR. These results showed a trend towards significance but remained statistically non-significant, possibly due to differences in the item-content relative to the VMT. Additionally, we encourage researchers to use non-parametric (robust) tools, since the distribution of CS scores, when collected in a similar experiment -and not aiming to purposefully induce CS-, would be right-tailed (i.e., most participants registering lower scores) and depending on the task, wildly variable. The use of common, linear tests in such cases may lead to many statistically significant, but potentially inflated and biased results.

4.4 Cybersickness in the VMT is best (and only) explained by modality and habituation

The goal of prediction analyses was to evaluate how fixed effects (Modality and Session), along with task performance and individual differences variables, influence CS scores. This was done to robustly assess what factors need to be taken into account to avoid CS when designing a VR navigation task.

In the SSQ, Modality (VR) and Session (PM) explained around 25 percent of the variability in our task, with performance and other individual differences not contributing to the models’ improvement. This is contrary to our hypothesized drop in task performance with higher CS symptomatology. However, it is important to note that participants improved in completion times across modalities, that is, despite higher CS when navigating in VR. While this might be task dependent, these findings contradict what other studies have found, showing that video game or VR experience major factors in CS incidence (Chang et al., 2020). Possibly, a predictive analysis of symptomatology differentiating by modality could facilitate the identification of other predictors, especially in VR.

The CSQ-VR Nausea subscore was best predicted by Session (PM) and higher VR experience. This result, opposed to findings in previous studies, might be related to variable definition. Upon inspection, VR experience, a compound score including VR use and perceived skill, show discrepancies in some participants. For example, very low or no use of VR, but moderate VR perceived skill, leading to increased VR experience values.

Finally, we believe it is necessary to consider the impact of the difference between the analytical methods employed in the literature to assess, model, and predict CS symptomatology, as well as the specific task type of CS symptomatology exposure.

5 Limitations

This study contains several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, our sample size was relatively small, consisting of 26 participants. While this study’s design is within-subjects, a larger sample would provide more statistical power and increase the generalizability of the findings. Also, our convenience sample focused on a specific demographic, namely, Spanish, highly educated, young adults with prior experience with technology. This may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations. While the study compared two commonly used cybersickness questionnaires (SSQ and CSQ-VR), other assessment tools exist that might provide additional insights or capture different aspects of cybersickness. Additionally, we only measured CS before and after task execution, not during. This limitation in capturing the temporal profile of CS while performing the VMT could be particularly significant for VR-naive participants. Incorporating objective measures like physiological data (e.g., heart rate variability, electrodermal activity), behavioral tracking (e.g., eye movements, postural sway) or electroencephalography (EEG), alongside subjective questionnaires, could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the physiological underpinnings of cybersickness.

The VMT included specific mitigation techniques such as peripheral blurring and field of view occlusion during movement, which might have influenced the reported levels of cybersickness. Our aim was to reduce high CS in the task detected during pilot testing; however, it remains unclear to what extent these techniques contributed to the observed habituation effects in the VR modality. Future studies could systematically investigate the effectiveness of different mitigation strategies on cybersickness and habituation (Rouhani et al., 2024; Chardonnet et al., 2021; Venkatakrishnan et al., 2024b). Also, FOV occlusion was applied to the VR modality, but not to Desktop to avoid reducing its already limited FOV. This difference in FOV might have impacted task performance across modalities. Finally, our evaluation might not generalize to other tasks outside the VMT, which was designed with a specific purpose (to measure spatial learning after sleep).

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the complex interplay between cybersickness, task performance, and modality in virtual navigation tasks. Our findings demonstrate that while VR environments offer enhanced immersion, they also induce higher levels of cybersickness compared to desktop setups. However, we observed significant habituation effects, suggesting that repeated exposure may mitigate these symptoms over time. Both of these effects are large and are the main contributors for explaining CS variability. The psychometric evaluation of the SSQ and CSQ-VR revealed strengths and limitations of each tool, highlighting the importance of choosing appropriate assessment methods based on research goals and experimental design. These results have important implications for both research methodology and practical applications in VR-based spatial cognition studies. They underscore the need for careful consideration of cybersickness when designing and interpreting experiments involving virtual navigation tasks. Future research should focus on larger, more diverse samples, incorporate a wider range of assessment tools including objective physiological measures, and systematically investigate the effectiveness of various cybersickness mitigation strategies. By addressing these areas, we can further refine our understanding of cybersickness in virtual environments and develop more robust, comfortable, and effective VR experiences for both research and real-world applications.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee, University of Navarra. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LE: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. MM: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank R. Wakefield for her help coordinating the translation/adaptation process of the CSQ-VR.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used in this manuscript to improve readability based on the authors’ original text.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frvir.2025.1518735/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1https://youtu.be/uAt-nu5dCaE?si=l4SKjaaNs8J7gBto

References

Aldaba, C. N., White, P. J., Byagowi, A., and Moussavi, Z. (2017). “Virtual reality body motion induced navigational controllers and their effects on simulator sickness and pathfinding,” in 2017 39th annual international Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and biology society (EMBC) (Seogwipo: IEEE, 4175–4178). doi:10.1109/EMBC.2017.8037776

Bimberg, P., Weissker, T., and Kulik, A. (2020). “On the usage of the simulator sickness questionnaire for virtual reality research,” in 2020 IEEE conference on virtual reality and 3D user interfaces abstracts and workshops (VRW) (Atlanta, GA: IEEE), 464–467. doi:10.1109/VRW50115.2020.00098

Bouchard, S., Berthiaume, M., Robillard, G., Forget, H., Daudelin-Peltier, C., Renaud, P., et al. (2021). Arguing in favor of revising the simulator sickness questionnaire factor structure when assessing side effects induced by immersions in virtual reality. Front. Psychiatry 12, 739742. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.739742

Brooks, M. E., Kristensen, K., van Benthem, K. J., Magnusson, A., Berg, C. W., Nielsen, A., et al. (2017). glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J. 9, 378–400. doi:10.32614/RJ-2017-066

Bruck, S., and Watters, P. A. (2011). The factor structure of cybersickness. Displays 32, 153–158. doi:10.1016/j.displa.2011.07.002

Buttussi, F., and Chittaro, L. (2018). Effects of different types of virtual reality display on presence and learning in a safety training scenario. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 24, 1063–1076. doi:10.1109/tvcg.2017.2653117

Campo-Prieto, P., Rodríguez-Fuentes, G., and Cancela Carral, J. M. (2021). Traducción y adaptación transcultural al español del Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (Translation and cross-cultural adaptation to Spanish of the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire). Retos 43, 503–509. doi:10.47197/retos.v43i0.87605

Carbonell-Carrera, C., Saorin, J., and Jaeger, A. (2021). Navigation tasks in desktop VR environments to improve the spatial orientation skill of building engineers. Buildings 11, 492. doi:10.3390/buildings11100492

Caserman, P., Garcia-Agundez, A., Gámez Zerban, A., and Göbel, S. (2021). Cybersickness in current-generation virtual reality head-mounted displays: systematic review and outlook. Virtual Real. 25, 1153–1170. doi:10.1007/s10055-021-00513-6

Chang, E., Kim, H. T., and Yoo, B. (2020). Virtual reality sickness: a review of causes and measurements. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 36, 1658–1682. doi:10.1080/10447318.2020.1778351

Chardonnet, J.-R., Mirzaei, M. A., and Merienne, F. (2021). Influence of navigation parameters on cybersickness in virtual reality. Virtual Real. 25, 565–574. doi:10.1007/s10055-020-00474-2

Clemenson, G. D., Wang, L., Mao, Z., Stark, S. M., and Stark, C. E. L. (2020). Exploring the spatial relationships between real and virtual experiences: what transfers and what doesn’t. Front. Virtual Real. 1, 572122. doi:10.3389/frvir.2020.572122

Clifton, J., and Palmisano, S. (2020). Effects of steering locomotion and teleporting on cybersickness and presence in HMD-based virtual reality. Virtual Real. 24, 453–468. doi:10.1007/s10055-019-00407-8

Domeyer, J. E., Cassavaugh, N. D., and Backs, R. W. (2013). The use of adaptation to reduce simulator sickness in driving assessment and research. Accid. Analysis and Prev. 53, 127–132. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2012.12.039

Dużmańska, N., Strojny, P., and Strojny, A. (2018). Can simulator sickness Be avoided? A review on temporal aspects of simulator sickness. Front. Psychol. 9, 2132. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02132

Eudave, L., Martínez, M., Valencia, M., and Roth, D. (2023). Registered report: evaluation of spatial learning and wayfinding in a complex maze using immersive virtual reality. Peer Community Registered Rep. doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/J8QFV

Feng, Y., Duives, D. C., and Hoogendoorn, S. P. (2022). Wayfinding behaviour in a multi-level building: a comparative study of HMD VR and Desktop VR. Adv. Eng. Inf. 51, 101475. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2021.101475

Garrido, L. E., Frías-Hiciano, M., Moreno-Jiménez, M., Cruz, G. N., García-Batista, Z. E., Guerra-Peña, K., et al. (2022). Focusing on cybersickness: pervasiveness, latent trajectories, susceptibility, and effects on the virtual reality experience. Virtual Real. 26, 1347–1371. doi:10.1007/s10055-022-00636-4

Gavgani, A. M., Nesbitt, K. V., Blackmore, K. L., and Nalivaiko, E. (2017). Profiling subjective symptoms and autonomic changes associated with cybersickness. Aut. Neurosci. 203, 41–50. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2016.12.004

Groth, C., Tauscher, J.-P., Heesen, N., Castillo, S., and Magnor, M. (2021). “Visual techniques to reduce cybersickness in virtual reality,” in 2021 IEEE conference on virtual reality and 3D user interfaces abstracts and workshops (VRW) (Lisbon, Portugal: IEEE), 486–487. doi:10.1109/VRW52623.2021.00125

Hejtmanek, L., Starrett, M., Ferrer, E., and Ekstrom, A. (2020). How much of what we learn in virtual reality transfers to real-world navigation? Multisensory Res. 33, 479–503. doi:10.1163/22134808-20201445

Hirzle, T., Cordts, M., Rukzio, E., Gugenheimer, J., and Bulling, A. (2021). “A critical assessment of the use of SSQ as a measure of general discomfort in VR head-mounted displays,” in Proceedings of the 2021 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (Yokohama Japan: ACM), 1–14. doi:10.1145/3411764.3445361

Howarth, P. A., and Hodder, S. G. (2008). Characteristics of habituation to motion in a virtual environment. Displays 29, 117–123. doi:10.1016/j.displa.2007.09.009

Huffman, D. J., and Ekstrom, A. D. (2021). An important step toward understanding the role of body-based cues on human spatial memory for large-scale environments. J. Cognitive Neurosci. 33, 167–179. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_01653

Jeung, S., Hilton, C., Berg, T., Gehrke, L., and Gramann, K. (2023). “Virtual reality for spatial navigation,” in Virtual reality in behavioral neuroscience: new insights and methods. Editors C. Maymon, G. Grimshaw, and Y. C. Wu (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 103–129. doi:10.1007/7854_2022_403

Kennedy, R. S., Lane, N. E., Berbaum, K. S., and Lilienthal, M. G. (1993). Simulator sickness questionnaire: an enhanced method for quantifying simulator sickness. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 3, 203–220. doi:10.1207/s15327108ijap0303_3

Keshavarz, B., Riecke, B. E., Hettinger, L. J., and Campos, J. L. (2015). Vection and visually induced motion sickness: how are they related? Front. Psychol. 6, 472. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00472

Khan, O., Nguyen, A., Francis, M., and Kim, K. (2024). “Exploring the impact of virtual human and symbol-based guide cues in immersive VR on real-world navigation experience,” in 2024 IEEE conference on virtual reality and 3D user interfaces abstracts and workshops (VRW), 883–884. doi:10.1109/VRW62533.2024.00238

Kim, E., Han, J., Choi, H., Prié, Y., Vigier, T., Bulteau, S., et al. (2021). Examining the academic trends in neuropsychological tests for executive functions using virtual reality: systematic literature review. JMIR Serious Games 9, e30249. doi:10.2196/30249

Kim, H. K., Park, J., Choi, Y., and Choe, M. (2018). Virtual reality sickness questionnaire (VRSQ): motion sickness measurement index in a virtual reality environment. Appl. Ergon. 69, 66–73. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2017.12.016

Kourtesis, P., Collina, S., Doumas, L. A., and MacPherson, S. E. (2021). Validation of the virtual reality everyday assessment lab (VR-EAL): an immersive virtual reality neuropsychological battery with enhanced ecological validity. J. Int. Neuropsychological Soc. 27, 181–196. doi:10.1017/S1355617720000764

Kourtesis, P., Collina, S., Doumas, L. A. A., and MacPherson, S. E. (2019). Validation of the virtual reality neuroscience questionnaire: maximum duration of immersive virtual reality sessions without the presence of pertinent adverse symptomatology. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 13, 417. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2019.00417

Kourtesis, P., Linnell, J., Amir, R., Argelaguet, F., and MacPherson, S. E. (2023a). Cybersickness, cognition, and motor skills: the effects of music, gender, and gaming experience. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 29, 2326–2336. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2023.3247062

Kourtesis, P., Linnell, J., Amir, R., Argelaguet, F., and MacPherson, S. E. (2023b). Cybersickness in virtual reality questionnaire (CSQ-VR): a validation and comparison against SSQ and VRSQ. Virtual Worlds 2, 16–35. doi:10.3390/virtualworlds2010002

Kourtesis, P., Papadopoulou, A., and Roussos, P. (2024). Cybersickness in virtual reality: the role of individual differences, its effects on cognitive functions and motor skills, and intensity differences during and after immersion. Virtual Worlds 3, 62–93. doi:10.3390/virtualworlds3010004

Lance, C. E., Butts, M. M., and Michels, L. C. (2006). The sources of four commonly reported cutoff criteria: what did they really say? Organ. Res. Methods 9, 202–220. doi:10.1177/1094428105284919

Lin, Y.-X., Babu, S. V., Venkatakrishnan, R., Venkatakrishnan, R., Wang, Y.-C., and Lin, W.-C. (2020). “Towards an immersive virtual simulation for studying cybersickness during spatial knowledge acquisition,” in 2020 IEEE conference on virtual reality and 3D user interfaces abstracts and workshops (VRW) (Atlanta, GA, USA: IEEE), 624–625. doi:10.1109/VRW50115.2020.00163

Luong, T., Plechata, A., Mobus, M., Atchapero, M., Bohm, R., Makransky, G., et al. (2022). “Demographic and behavioral correlates of cybersickness: a large lab-in-the-field study of 837 participants,” in 2022 IEEE international symposium on mixed and augmented reality (ISMAR) (Singapore, Singapore: IEEE), 307–316. doi:10.1109/ISMAR55827.2022.00046

Mair, P., and Wilcox, R. (2020). Robust statistical methods in r using the wrs2 package. Behav. Res. Methods 52, 464–488. doi:10.3758/s13428-019-01246-w

Maneuvrier, A., Nguyen, N.-D.-T., and Renaud, P. (2023). Predicting vr cybersickness and its impact on visuomotor performance using head rotations and field (in)dependence. Front. Virtual Real. 4. doi:10.3389/frvir.2023.1307925

Martirosov, S., Bureš, M., and Zítka, T. (2022). Cyber sickness in low-immersive, semi-immersive, and fully immersive virtual reality. Virtual Real. 26, 15–32. doi:10.1007/s10055-021-00507-4

Mayor, J., Raya, L., and Sanchez, A. (2021). A comparative study of virtual reality methods of interaction and locomotion based on presence, cybersickness, and usability. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 9, 1542–1553. doi:10.1109/TETC.2019.2915287

Mayrose, L., and Maidenbaum, S. (2024). “Comparatively testing the effect of reality modality on spatial memory,” in 2024 IEEE conference on virtual reality and 3D user interfaces abstracts and workshops (VRW), 925–926. doi:10.1109/VRW62533.2024.00259

Mittelstaedt, J., Wacker, J., and Stelling, D. (2018). Effects of display type and motion control on cybersickness in a virtual bike simulator. Displays 51, 43–50. doi:10.1016/j.displa.2018.01.002

Murphy, M., Stickgold, R., Parr, M. E., Callahan, C., and Wamsley, E. J. (2018). Recurrence of task-related electroencephalographic activity during post-training quiet rest and sleep. Sci. Rep. 8, 5398. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-23590-1

Nalivaiko, E., Rudd, J. A., and So, R. H. (2014). Motion sickness, nausea and thermoregulation: the “toxic” hypothesis. Temperature 1, 164–171. doi:10.4161/23328940.2014.982047

Nguyen, N. D., Tucker, M. A., Stickgold, R., and Wamsley, E. J. (2013). Overnight sleep enhances hippocampus-dependent aspects of spatial memory. Sleep 36, 1051–1057. doi:10.5665/sleep.2808

Palmisano, S., and Constable, R. (2022). Reductions in sickness with repeated exposure to HMD-based virtual reality appear to be game-specific. Virtual Real. 26, 1373–1389. doi:10.1007/s10055-022-00634-6

R Core Team (2021). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Reason, J. T. (1978). Motion sickness adaptation: a neural mismatch model. J. R. Soc. Med. 71, 819–829. doi:10.1177/014107687807101109

Rebenitsch, L., and Owen, C. (2016). Review on cybersickness in applications and visual displays. Virtual Real. 20, 101–125. doi:10.1007/s10055-016-0285-9

Riccio, G. E., and Stoffregen, T. A. (1991). An ecological theory of motion sickness and postural instability. Ecol. Psychol. 3, 195–240. doi:10.1207/s15326969eco0303_2

Rouhani, R., Umatheva, N., Brockerhoff, J., Keshavarz, B., Kruijff, E., Gugenheimer, J., et al. (2024). Tackling vr sickness: a novel benchmark system for assessing contributing factors and mitigation strategies through rapid vr sickness induction and recovery. Displays. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4790891

Ruddle, R. A., and Lessels, S. (2006). For efficient navigational search, humans require full physical movement, but not a rich visual scene. Psychol. Sci. 17, 460–465. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01728.x

Saredakis, D., Szpak, A., Birckhead, B., Keage, H. A. D., Rizzo, A., and Loetscher, T. (2020). Factors associated with virtual reality sickness in head-mounted displays: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14, 96. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2020.00096

Sepich, N. C., Jasper, A., Fieffer, S., Gilbert, S. B., Dorneich, M. C., and Kelly, J. W. (2022). The impact of task workload on cybersickness. Front. Virtual Real. 3, 943409. doi:10.3389/frvir.2022.943409

Sevinc, V., and Berkman, M. I. (2020). Psychometric evaluation of Simulator Sickness Questionnaire and its variants as a measure of cybersickness in consumer virtual environments. Appl. Ergon. 82, 102958. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2019.102958

Sharples, S., Cobb, S., Moody, A., and Wilson, J. R. (2008). Virtual reality induced symptoms and effects (VRISE): Comparison of head mounted display (HMD), desktop and projection display systems. Displays 29, 58–69. doi:10.1016/j.displa.2007.09.005

Srivastava, P., Rimzhim, A., Vijay, P., Singh, S., and Chandra, S. (2019). Desktop VR is better than non-ambulatory HMD VR for spatial learning. Front. Robotics AI 6, 50. doi:10.3389/frobt.2019.00050

Stamm, A. W., Nguyen, N. D., Seicol, B. J., Fagan, A., Oh, A., Drumm, M., et al. (2014). Negative reinforcement impairs overnight memory consolidation. Learn. and Mem. 21, 591–596. doi:10.1101/lm.035196.114

Torchiano, M. (2020). Effsize: efficient effect size computation. R. package. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1480624

Treisman, M. (1977). Motion sickness: an evolutionary hypothesis. Sci. New Ser. 197, 493–495. doi:10.1126/science.301659

Venkatakrishnan, R., Venkatakrishnan, R., Raveendranath, B., Canales, R., Sarno, D. M., Robb, A. C., et al. (2024a). The effects of secondary task demands on cybersickness in active exploration virtual reality experiences. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 30, 2745–2755. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2024.3372080

Venkatakrishnan, R., Venkatakrishnan, R., Raveendranath, B., Sarno, D. M., Robb, A. C., Lin, W.-C., et al. (2024b). The effects of auditory, visual, and cognitive distractions on cybersickness in virtual reality. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 30, 5350–5369. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2023.3293405

Voinescu, A., Petrini, K., and Stanton Fraser, D. (2023). Presence and simulator sickness predict the usability of a virtual reality attention task. Virtual Real. 27, 1967–1983. doi:10.1007/s10055-023-00782-3

Wamsley, E. J., Hamilton, K., Graveline, Y., Manceor, S., and Parr, E. (2016). Test expectation enhances memory consolidation across both sleep and wake. PLOS ONE 11, e0165141. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0165141

Wamsley, E. J., and Stickgold, R. (2019). Dreaming of a learning task is associated with enhanced memory consolidation: replication in an overnight sleep study. J. Sleep Res. 28, e12749. doi:10.1111/jsr.12749

Yildirim, C. (2020). Don’t make me sick: investigating the incidence of cybersickness in commercial virtual reality headsets. Virtual Real. 24, 231–239. doi:10.1007/s10055-019-00401-0

Zhao, J., Sensibaugh, T., Bodenheimer, B., McNamara, T. P., Nazareth, A., Newcombe, N., et al. (2020). Desktop versus immersive virtual environments: effects on spatial learning. Spatial Cognition and Comput. 20, 328–363. doi:10.1080/13875868.2020.1817925

Keywords: cybersickness, SSQ, CSQ-VR, virtual reality, VR, desktop, navigation

Citation: Eudave L and Martínez M (2025) To VR or not to VR: assessing cybersickness in navigational tasks at different levels of immersion. Front. Virtual Real. 6:1518735. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2025.1518735

Received: 28 October 2024; Accepted: 29 January 2025;

Published: 21 February 2025.

Edited by:

Stephen Palmisano, University of Wollongong, AustraliaReviewed by:

Matthew Coxon, York St John University, United KingdomRohith Venkatakrishnan, University of Florida, United States

Copyright © 2025 Eudave and Martínez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Luis Eudave, bGV1ZGF2ZUB1bmF2LmVz

Luis Eudave

Luis Eudave Martín Martínez

Martín Martínez