- 1School of Psychology, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, United Kingdom

- 3School of Health in Social Science, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Introduction: Gang involvement poses serious risks to young people, including antisocial and criminal behaviour, sexual and criminal exploitation, and mental health problems. There is a need for research-informed development of preventive interventions. To this end, we conducted a qualitative study of young people’s responses to an educational virtual reality (VR) experience of an encounter with a gang, to understand young people’s decisions, emotions and consequences.

Methods: Young people (N = 24 aged 13-15, 11 female, 13 male) underwent the VR experience followed by semi-structured focus group discussions. Questions focused on virtual decision-making (motivations, thoughts, feelings, consequences) and user experiences of taking part. Data were analysed using Thematic Analysis.

Results: Three themes were developed to represent how participants’ perceptions of the gang, themselves, and the context influenced virtual decisions. Social pressure from the gang competed with participants’ wish to stand by their morals and establish individual identity. The VR setting, through its escalating events and plausible characters, created an “illusion of reality” and sense of authentic decisions and emotions, yielding insights for real-life in a safe, virtual environment.

Discussion: Findings shed light on processes influencing adolescent decision-making in a virtual context of risk-taking, peer pressure and contact with a gang. Particularly, they highlight the potential for using VR in interventions with young people, given its engaging and realistic nature.

1 Introduction

Adolescence is a developmental period during which major biological and psychosocial changes take place including puberty, social reorientation toward peers, transition to autonomy, and a developmental peak in risk-taking behaviour (Adams and Berzonsky, 2003; Steinberg, 2008; Duell et al., 2018; Nelson et al., 2005). These adolescent changes coincide with a developmentally heightened risk of antisocial and criminal behaviour (Landsheer and Dijkum, 2005; Grigorenko, 2011). Notably, the rate and severity of crime committed during adolescence is predictive of future offences (Overbeek et al., 2001). We need better understanding of the processes and individual decision pathways by which adolescents become involved in antisocial and criminal behaviour, in order to develop better intervention strategies.

What are the factors that determine a young person’s risk and degree of involvement in antisocial/criminal behaviour? Research has proposed a multitude of factors operating at the level of society, community, immediate social contacts, and the individual (Mak, 1990). In the current paper, we focus on individual factors and processes, and their interaction with the immediate peer group, taking into account community-level context in the West Midlands region of the United Kingdom.

1.1 Youth involvement in gangs

Recent statistics indicate high reported rates of violent crime amongst young people in the United Kingdom. In 2021, West Midlands Police reported the highest rate of knife offences nationally (156 per 100,000 population), of which 18% were committed by adolescents (aged 10–17) (Allen and Harding, 2021). A substantial proportion of this violent criminal behaviour takes place in a context of gangs, characterised as “relatively durable, predominantly street-based groups of young people who see themselves (and are seen by others) as a discernible group, engage in criminal activity and violence, lay claim over geographical and/or illegal economic territory, have some form of identifying structural feature, and are in conflict with other gangs” (Home Office, 2015, p. 2). The presence of gangs in a local community poses substantial risks to young people, including a higher likelihood of criminal and sexual exploitation, violence, and substance abuse (Krohn et al., 2011; Moyle, 2019; HM Government, 2022). According to a recent report, more than 300,000 10–17-year-olds in the United Kingdom know a gang member (Children’s Commissioner, 2019). Typically, the most vulnerable children (e.g., looked-after, poorer socioeconomic backgrounds) are at most risk from gangs (Home Office, 2018), which deliberately recruit from within this age range (Children’s Society, 2022). Exposure to the risks associated with gang involvement as a young person are associated with mental health problems, victimization and future criminality (Wood and Dennard, 2017; Moyle, 2019; Frisby-Osman and Wood, 2020). This provides a strong rationale for conducting research on this topic.

In addition to the above-mentioned community-level processes and associated risk factors, an array of individual cognitive and social developmental mechanisms are thought to contribute to a young person’s trajectory of involvement in antisocial and criminal behaviour. Here, we focus on factors including the formation of individual and social identity, susceptibility to peer influence and morality/moral development.

1.2 Identity formation and peer groups

The formation of individual and social identity is an important component of adolescent development (Grigorenko, 2011). Whilst the development of personal identity involves individuation and independence, social identity development requires a sense of belonging within social groups (Tajfel, 1982; Benish-Weisman et al., 2015). The tension between personal and social identity is said to present a developmental challenge for adolescents (Kroger, 2005). During adolescence, peer groups are especially salient for social identity and fulfilment of belongingness (Newman and Newman, 1976). Individuals form positive evaluations of groups to which they belong (Tajfel, 1979), which may influence behaviour within social groups, potentially via peer socialization and social influence processes (Brechwald and Prinstein, 2011). Susceptibility to peer influence peaks in mid-adolescence across risk-taking, prosocial and neutral contexts (Steinberg and Monahan, 2007; Knoll et al., 2015; Foulkes et al., 2018). This susceptibility may contribute to adolescents’ greater tendency to take risks and commit crime in groups (rather than alone) (Zimring, 1998), and drive additional associations between peer-related factors (e.g., attitudes favourable to antisocial behaviour, interactions with deviant peers) and adolescent antisocial behaviour (Forsyth et al., 2018). As such, a young person’s perceptions of their identity in relation to that of a salient peer group, and processes of individuation vs. social influence, are potentially relevant for understanding adolescent decisions around risk-taking, gangs and antisocial/criminal behaviour.

Another facet of identity, and one which plays a role in individual decision-making, is morality (Tangney et al., 2007). Individuals hold moral standards comprising universal and culture-specific moral rules. These translate to moral behaviour in varying degrees depending on individual and social contextual factors. In a peer group setting, interpersonal negotiation and diffusion of responsibility can limit the capacity to act in accordance with one’s moral standards. Conversely, experiencing consequential or anticipatory moral emotions such as guilt strengthens the link between moral standards and moral behaviour (Tangney et al., 2007). During adolescence, moral emotions continue to develop (Malti, 2013; Malti et al., 2013; Krettenauer et al., 2014). In one adolescent study, experiencing guilt (as opposed to shame) was associated with lower aggression, greater empathy, and increased propensity to take responsibility (Stuewig et al., 2010). Furthermore, low levels of morality regarding attitudes towards violence and criminality in adolescence are associated with antisocial behaviour and delinquent peer associations (Tarry and Emler, 2010; Chrysoulakis, 2020). However, this can also be explained by moral disengagement theory, which suggests that to commit offending behaviour (e.g., violence) in a gang, individuals detach the moral element from the act itself to rationalise their actions (Bandura, 2006). This is a particular problem within street gangs, where the context can increase the likelihood of moral disengagement (Niebieszczanski et al., 2015). According to social contagion theory, this is due to the contagious nature of gang violence from one gang member to another which sustains gang membership (Tsvetkova and Macy, 2015; Brantingham et al., 2021).

To summarise, converging evidence indicates that cognitive and social developmental factors, such as individual and social identity, peer influence, and moral emotions, may play a role in adolescent decision pathways to antisocial and criminal behaviour. As such, this is relevant within the context of the current research, in which we explore young people’s decision-making in a virtual gang scenario.

1.3 Current interventions for gang involvement

The current study explores a novel addition to existing school-based interventions around antisocial/violent behaviour in the context of gangs. Previous preventive interventions targeting young people at risk of gang membership tend to comprise educational programmes in which young people can have open conversations with peers and trusted adults (e.g., charity workers, police officers), and be challenged on their existing beliefs about gang membership (HM Government, 2015). An example of this is the G.R.E.A.T. programme (Gang Resistance Education and Training Program) which was implemented and evaluated in the US with two key goals: a) preventing gang membership and other forms of violence, and b) building positive relationships with the police (Esbensen et al., 2011). The programme documented significant improvements in reducing gang membership in the US (Esbensen et al., 2011), and was later adapted and evaluated in the United Kingdom as the Growing Against Gangs and Violence (GAGV) programme (Densley et al., 2017). However, no significant programme effect was found in the United Kingdom (Densley et al., 2017). Issues around young people’s involvement in gangs and associated antisocial/violent behaviour remains a pressing issue within the United Kingdom, highlighting a need for research to support and contribute to the evidence base around novel interventions (e.g., Wood, 2019).

The current study investigated a virtual reality (VR) experience designed to address issues around risk-taking, peer pressure, gang involvement and violent/antisocial behaviour among young people, developed via a theatre-in-education (TiE) approach.

1.4 Theatre-in-education approach

Theatre-in-education (TiE) uses performances, workshops and role play to explore challenging, sensitive topics with children and adolescents (Jackson and Vine, 2013; Wooster, 2016). As an interactive method of education, it allows individuals to engage in their own autonomous learning, visualising and responding to the experience and forming emotional connections to characters (Krahe and Knappert, 2009; Jackson and Vine, 2013). Arguably, TiE’s most effective feature is interactively involving young people in the intervention (e.g., making decisions, interacting with characters; Jackson and Vine, 2013). A body of research including randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews indicates effectiveness of TiE interventions on topics including child sexual abuse and mental health, demonstrating increases in risk perception and knowledge gain for adolescents (Fryda and Hulme, 2015; Krahe and Knappert, 2009; Rousseau et al., 2014). Moreover, recent studies reported positive findings following a school-based TiE programme focusing on two similarly complex topics, specifically child sexual exploitation and abuse (CSEA) and child criminal exploitation (CCE; May et al., 2021; Swancott et al., 2023). This prior TiE programme included a live theatre performance by actors followed by an interactive workshop. Adolescent participants reported that the performance was impactful for them, and that they felt more aware of exploitation and had an increased understanding of the topic as a result of attending the programme (May et al., 2021). As such, the TiE approach has documented potential for actively engaging young people on potentially difficult, challenging topics.

1.5 Current research

A key TiE method that is used increasingly in recent years and incorporated into the novel ‘tech-in-education’ sector is virtual reality (VR). VR is defined as “the use of computer modelling and simulation that enables a person to interact with an artificial three-dimensional visual or other sensory environment” (Halldorsson et al., 2021, p.585). Interactive VR in particular lends itself well to the interactive nature of TiE, as participants make decisions which may change the course of the experience (cf. Boal, 1993; P. Hyde, personal communication, February 2022).

Research highlights a wealth of advantages to using VR, including positive effects on learning, motivation, and enjoyment (Kavanagh et al., 2017). VR can be used to enable participants to experience life-like situations that would be too dangerous to undertake in real life (Abdul Rahim et al., 2012), with resultant learning and insight that translates to the real world (Xie et al., 2021). Furthermore, compared with classic TiE methods, VR offers increased capacity for flexible, consistent and widespread delivery without the need for live actors. Moreover, studies have supported VR use in sophisticated social environments (Kozlov and Johansen, 2010; Haddad et al., 2014), showing promising findings regarding individuals’ understanding of their decisions. Although VR use is less well documented in adolescent compared to adult populations, evidence indicates impressive completion rates and ability to evoke authentic emotions, including empathy and the moral emotion guilt (Barreda-Angeles et al., 2021; Halldorsson et al., 2021). The current study investigated adolescents’ decision-making and emotional responses to an immersive VR experience of gang involvement and antisocial behaviour. To our knowledge, this is the first virtual reality intervention used in schools to address gangs and violence, and the first to be evaluated within the academic literature.

In conducting the current study, we aimed to address some limitations documented in prior VR research. It has been noted that VR studies need clearer theoretical grounding and provision of methodological detail (Halldorsson et al., 2021). Other studies highlight software usability issues, including poor interaction quality and readability (e.g., Hseih et al., 2010); although this limitation may predominantly apply to non-immersive VR, with immersive VR using headsets resulting in a more compelling experience (e.g., Halldorsson et al., 2021). The current VR programme is informed by psychological theory of adolescent risk-taking and was developed in a research-informed, participatory manner to overcome the previously mentioned limitation (see Method section for a more detailed description). There is scope to expand research in this area, particularly in the context of methodology, experiences of VR and adolescent populations.

The aim of the current study was to explore adolescents’ experiences of risk-taking and decision-making during a virtual encounter with a potential gang developed using a TiE approach (Round Midnight Ltd, 2019). Live-action footage was used to simulate a naturalistic environment and characters, while VR headsets increased immersion (Sütfeld et al., 2017). The VR format was interactive, such that participants were able to make decisions and interact with the virtual characters, applying the most effective features of TiE (Jackson and Vine, 2013). We explored the experiences of adolescents interacting with this immersive VR. A qualitative approach to data collection was used to understand participants’ thoughts, feelings and experiences in depth. Data were gathered via focus group discussions, a format that allows participants to build upon and reflect on each other’s contributions, increasing data richness (Braun and Clarke, 2013). Finally, the study sought to overcome some prior limitations in VR, including the lack of sufficient methodological detail on the VR experience. In order to answer the overall research question of “What are young peoples’ experiences of a VR encounter with a gang, in terms of decisions, emotions and consequences?”, the study aimed:

1) To elicit young people’s accounts of their decisions in a virtual context of risk-taking, gang involvement and antisocial behaviour, including motivational, social and emotional factors and consequences, using a qualitative (focus group) design;

2) To explore the VR experience as an educational intervention tool to promote young people’s discussion and reflection on issues with real-world relevance, i.e., risk-taking, gang involvement and antisocial behaviour; and

3) To investigate young people’s experiences of interacting with the VR, including featured characters and events, and the virtual as opposed to real-world setting.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants and recruitment

The present study recruited 24 adolescents aged 13–15 years (11 female, 13 male) from four state secondary schools in the West Midlands. Schools were selected based on current contact with our TiE partner Round Midnight Ltd. and local relevance of issues featured in the VR experience. The resultant sample was drawn from predominantly mixed or low socioeconomic central and suburban areas within the West Midlands conurbation. Participating schools distributed information sheets and parent/guardian consent forms to pupils. Parent/guardian consent and participant assent were obtained. The study was granted ethical approval by the University of Birmingham Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Ethical Review Committee (ERN 19-1099) and researchers adhered to the British Psychological Society’s (2021) Code of Ethics and Conduct.

2.2 Materials

2.2.1 The virtual reality experience

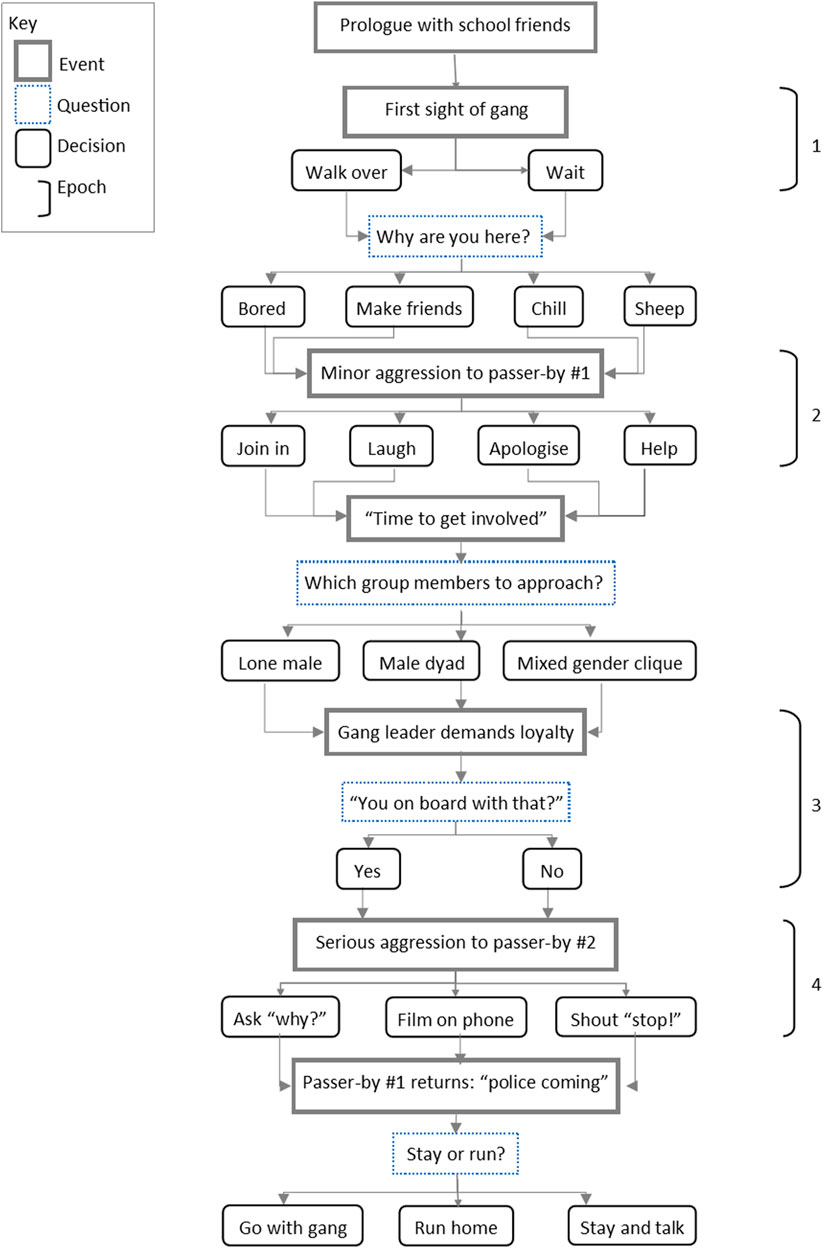

“Virtual_Decisions: GANGS” is an interactive, immersive VR experience developed by West Midlands-based creative arts and tech-in-education company Round Midnight Ltd. It is used to facilitate school workshops discussing personal, social and health education (PSHE) topics, such as youth violence/gang behaviour, risk-taking and peer pressure. The VR experience was created using Unity, a cross platform game engine developed by Unity Technologies (https://unity.com/). Through the VR experience, participants are placed in a live-action scenario involving a simulated encounter with a potential gang (see Figure 1). This takes place via an 8-min interactive live-action audio-visual experience delivered via Oculus Go and Oculus Quest 2 headsets providing an immersive 180-degree interactive experience. Sound input is received via headphones and participants navigate through the experience, making decisions by moving their head to navigation targets shown on-screen. Specifically, in the VR scenario, participants make decisions about who to speak to, what to say and their level of involvement in two escalating acts of antisocial behaviour enacted toward passers-by. Main events, decision points and decision options are depicted in Figure 2. Some decisions impact the events experienced (e.g., which group members to approach, see Figure 2), but the overall structure of events remains the same. The semi-structured interview guide focused on epochs 1–4 depicted in Figure 2, with participants free to discuss any part of the experience. In line with the aims of the current study, we did not record participant decisions on the VR headsets.

FIGURE 1. (A) The virtual reality set-up experienced by participants. Photo credit: © Round Midnight Ltd. Reproduced with permission. (B) Youth actors portraying gang members within Round Midnight’s Virtual_Decisions: GANGS interactive virtual reality experience. Photo credit: © Round Midnight Ltd. Reproduced with permission.

FIGURE 2. Summary of main events and decisions in Virtual_Decisions: GANGS (Reproduced with permission from Round Midnight Ltd, 2019). The term ‘sheep’ refers to someone who is easily influenced and follows the crowd.

In terms of the acts of antisocial behaviour depicted in the VR, in the first of these, the participant witnesses the group intimidating a passer-by (by not allowing them to pass, taking an item out of their shopping bag and throwing it between the group, then returning it and letting the passer-by leave). In the second, more serious, act of antisocial behaviour, the group intimidates two passers-by (a young couple) by shouting at them, approaching them, getting physically close to the young male and continuing to shout and jostle him, and subsequently the young male passer-by ends up on the ground being assaulted; however, what exactly this entails (i.e., assault via kicking/punching and/or use of weapons) is ambiguous as the action is partially obscured from view by the group members’ bodies.

Before starting the VR experience, the participant is told that they will be introduced to a ‘group’ that two of their former primary school friends now hang out with. This group (totalling 12 individuals) is not defined as a gang to participants, but typically, including in the current study, young people spontaneously use the term ‘gang’ to describe the group. The word ‘gang’ has more than one common usage. First, young people sometimes use the term to refer to a group of people hanging out together, without any criminal features. Second, the term gang (e.g., street gang, criminal gang) is used and defined as a group of three or more individuals where illegal activity is a core part of their group identity (Klein et al., 2001).

In Round Midnight’s “Virtual_Decisions: GANGS” educational programme, the VR experience is delivered within workshops and 12-part interactive curriculum created in conjunction with Manchester Violence Reduction Unit, led by experienced TiE facilitators, typically as a primary prevention strategy to discuss complex issues in a trauma-informed manner. However, for the purposes of conducting the current research study, we administered the VR experience and backstory, without the accompanying curriculum.

The involvement of Round Midnight in the research is summarised as follows. Round Midnight applied for and received funding from United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI) to develop a VR experience featuring a youth-relevant issue. They conducted extensive, iterative grassroots consultations with >1,000 young people via surveys, workshops, and theatre improvisations in order to select the topic (risk-taking behaviours) and develop the scenario and script. Partway through this process, the last author was approached to provide research consultancy input based on her expertise on the neuroscience/psychology of adolescent risk-taking. This input was incorporated as part of Round Midnight’s research and development process, specifically during script and character development. Round Midnight own and license the VR experience, and they made it available to the research team free of charge (along with a number of VR headsets) for the purposes of conducting this research. Finally, Round Midnight facilitated participant recruitment for the current study via their school contacts.

2.3 Procedure

2.3.1 Data collection

A total of six focus groups were conducted in school classrooms. Focus Groups 1, 2 and 5 (FG1, FG2, FG5) consisted of five participants and Focus Groups 3, 4 and 6 (FG3, FG4, FG6) consisted of three participants. In accordance with the preferences of each of the four schools, FG1 had one teacher present (seated at the back of the classroom); FG2, FG3 and FG4 had no member of school staff present; and FG5 and FG6 had a member of school staff present (seated at the back of the classroom). All focus groups were 45–60 minutes in duration, in accordance with school timetabling constraints. Participants sat in a circular formation around a cluster of desks with the two researchers. Due to changing COVID-19 restrictions, the first two sets of focus group participants sat two metres apart with face masks on, two metres away from the researchers. Subsequent focus groups sat within one metre of each other with no face masks, two metres away from the researchers, who wore face masks.

The researchers began each focus group by outlining the ‘backstory’ and context of the VR scenario which participants would enter virtually (an introduction to the group of people who two former childhood friends hang out with). Participants underwent the eight-minute VR experience individually. Immediately after, participants spent five minutes completing a short anonymous questionnaire which asked them to circle the decisions they made at each of the four key decision points shown in Figure 2, and to note an emotion they felt at the point of decision-making, intended as a memory and reflection aid. Participants were asked to pick a pseudonym out of a choice of name labels. The researchers explained the ground rules of the ensuing focus group discussions which followed a semi-structured topic guide (see Supplementary Material). The focus group discussions were led by one researcher and supported by the second researcher. Questions focused on participants’ decision-making during the VR experience as a whole and at the four key epochs shown in Figure 2, including motivations, thoughts, feelings, consequences, reflections, VR vs. real-world comparisons, and user experiences. The discussions were recorded using an encrypted Dictaphone.

2.4 Transcription

A professional transcription service transcribed the audio recordings verbatim and the transcripts were imported into a qualitative data analysis software program, NVivo20, to facilitate coding and analysis.

2.5 Analysis

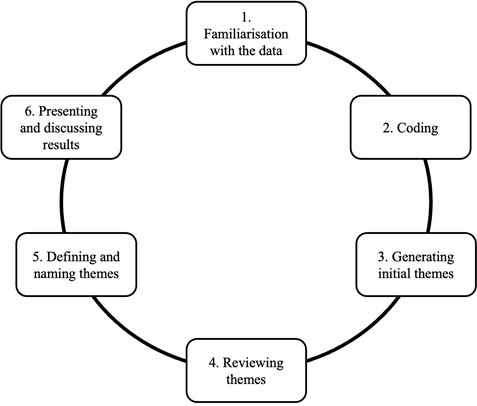

The researchers used a thematic analysis approach to analyse the focus group data. Thematic Analysis (TA) was chosen for its data-driven, flexible nature and ability to give a voice to participants, which is important for topics that have not yet been explored (Braun and Clarke, 2013). TA identifies and analyses patterns across the data, allowing themes to be developed which capture important aspects of the data in relation to the research question (Braun and Clarke, 2013). The researchers followed the six-phase process recommended by Braun and Clarke (2013) which is represented in Figure 3. The researchers kept a reflective diary during the process of collecting and analysing the data which encompassed their thoughts, feelings and other notable observations regarding each focus group.

FIGURE 3. Steps undertaken during the process of thematic analysis (based on the six phases of thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (2006); Braun and Clarke (2013).

The two researchers began the process of analysis independently by allocating and reading three transcripts each and coding them line-by-line using descriptive codes. Next, the two researchers independently identified relevant themes across their allocated transcripts. Following this, the two researchers met together to discuss the themes representing the whole dataset. They subsequently met with the supervisory team to discuss the themes in more depth, resolve any disagreement or discrepancies, develop overarching themes that represented the full dataset, and discuss interpretations of the data in relation to the theme development. This iterative process was repeated three times to identify themes and subthemes, discuss possible interpretations and organization of the data, and further develop themes relevant to the research questions. Finally, through this process, the final set of themes and subthemes were developed.

2.6 Epistemological position

TA is theoretically flexible which allows for a data-driven approach to analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2013). The researchers in the current study adopted a realist position, aiming to describe young people’s experiences and decision-making in the VR experience independent of pre-existing perceptions or theory. Furthermore, the researchers’ characteristics, role and influence in the focus group discussions, and later interpretation, was also reflected upon. Particularly, the researchers were both white, young, educated females. Some of these characteristics may have contributed to creating an informal, non-threatening and respectful environment in which participants felt able to share their experiences. On the other hand, this same set of characteristics may have limited participants’ ability to relate to the researchers or feel understood, reducing the information shared, or encouraging a set of desirable, rather than true, responses. The latter was also felt to be the case in the two focus group discussions in which a member of teaching staff was present. These possible influences have been considered and taken into account as part of making sense of the study’s findings.

3 Results

The present study considers young people’s accounts of the decisions they made, what motivated and influenced these decisions, how they felt, consequences, and VR vs. real-world comparisons, in a context of virtual risk-taking and peer pressure. The following findings are framed around individuals’ decisions to go with or against the group, and the emotions, perceptions and risks associated with these decisions.

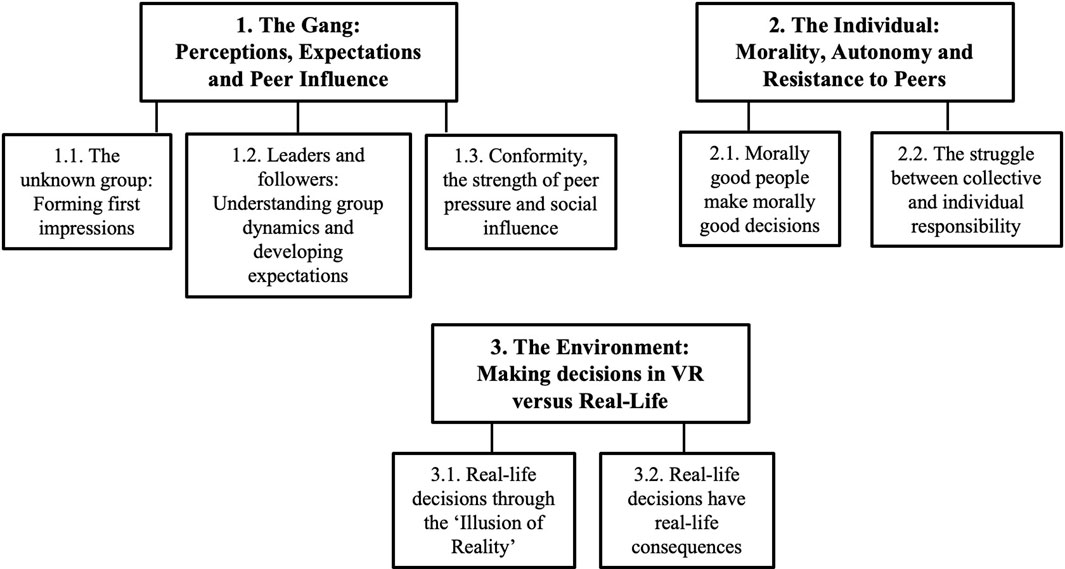

Most participants reported that they were willing to oppose the group in order to do the “right thing”. These decisions were primarily influenced by participants’ perceptions of themselves, the group and the situation. Three themes were developed encapsulating these influences on virtual decision-making: See Figure 4 1) “The Gang: Perceptions, expectations and peer influence” centres around participants’ perceptions of the group and its dynamics; 2) “The Individual: Morality, autonomy and resistance to peers” reflects the process of constructing an individual identity through decision-making; and finally 3) “The Environment: Making decisions in VR versus real-life” considers the characteristics of the VR experience and relationship to real-life decisions. Direct quotes from participants are presented to illustrate the three themes.

3.1 Theme 1. The gang: perceptions, expectations and peer influence

Descriptions about the group naturally emerged in discussions, highlighting its importance throughout the experience. This theme represents participants’ perceptions of the group and its influence on their decisions. Three main aspects were discussed: a) “The Unknown Group: Forming first impressions” considers the group’s features, b) “Leaders and followers: Understanding group dynamics and developing expectations” reflects on group dynamics, and 3) “Conformity, the strength of peer pressure and social influence” mainly centres around peer influence.

3.1.1 The unknown group: forming first impressions

All six focus groups reflected upon and contributed to explaining the features of the group. Since no prior information was provided about them, participants’ perceptions originated in initial impressions and developed during the experience. Initially, some participants considered the group to be “normal people […] they just looked like everybody that’s round here” (FG2), as well as thinking “they would probably be nice” (FG5). Instead, others assumed that “they were all like roadmen, women, people” (FG4) and that they would be bad from the start: “When I saw them, the first reaction that I had, I was like oh no, they’re bad people–they don’t have the good mindsets and stuff, they’re not good human beings.” (FG6). These initial differences across focus groups seemed to emerge as a result of participants relying on their own understanding and past experiences with similar people, groups, and situations.

As participants advanced through the experience, they formed impressions and expectations about the group: “I did expect something bad to happen, at the end, because of just like where they were, what they were doing and how big of a group it was” (FG2). By the end of the experience, all groups seemed to agree that “obviously, they’re bad people” (FG4) who were “horrible to anyone just because they feel like it, belittling others because they’re bored and feel like they’re better than everyone else” (FG3). Additionally, some hinted at the possibility that the group was a gang whose aim was “to recruit new people” (FG5):

“I think, by the body language and the way they acted within the groups, and I could hear what they were saying as well, I had an insight that they would probably be in some sort of (gang) sub-culture and they would probably encourage me to go into county lines and do criminal activities” (FG6).

In general, the group was perceived to be bad people, however, this label was not applied uniformly across the group members. Two characters in the story were introduced as participants’ former friends. Participants initially reported perceiving them as good and trustworthy people who were different from the group: “They didn’t seem like they’d associate with the rest of them (the group), but I thought that I could trust them, they seemed like decent” (FG4). In turn, their behaviour seemed to be rationalized “They might have felt pressured themselves, so they were just sticking with the majority and trying to blend in.” (FG1).

At its core, the mere notion of friendship, even if hypothetical, contributed to shaping participants’ perceptions and expectations differently. While their former friends were mainly considered good people going “with the wrong crowd” (FG1), the group was seen as bad people who “had lost their morals” (FG3).

3.1.2 Leaders and followers: understanding group dynamics and developing expectations

Participants’ descriptions of the group demonstrated their perceptions of gangs: the way they function, their structure and group dynamics. For them, the gang consisted of a leader whose role was primarily to control and intimidate the group: “By the way he acts, people are probably usually scared of him” (FG3), and members who “just followed their leader” (FG4) and “will do anything he says” (FG3).

This group dynamic meant that rather than being friends, the group was seen as unrelated people only coming together for violence: “you can just tell by the people that none of them are actually good mates. They’re just there for violence, something to laugh at.” (FG4). Therefore, there was no expectation that group members would support each other, but that each individual would protect their own interests:

“I don’t even think they were really caring for each other, to be honest, the way that they were, em, talking to each other and acting […] With groups like this, they are together, but then they tend to stab each other in the back quite quickly if the chance comes.” (FG2).

Due to the awareness of the type of group they might be, participants felt a sense of uncertainty and unease in terms of their behaviour. In particular, they expressed concern for how the group would react to them and how they would be treated: “I don’t know if they would use violence on you. I mean, I’ve seen it with other people, but I don’t know if they’d do it to someone else who was in the group with them” (FG4):

“I did feel slightly afraid, but that’s because […] I didn’t know how they would act. I did get a general idea of their personalities and what group they’re part of, but, how specifically they would act, I wouldn’t have known.” (FG6).

Given the possibility that the group might turn on them, the general agreement was that participants were expected to “just be a lapdog, just listen to whatever they say and do whatever they asked you to do” (FG1). For that reason, most participants believed they were expected to follow along and act like the rest of the group: “If they were fighting people, they’d want to see you fight as well” (FG5). Overall, awareness of group dynamics and behaviours shaped participants’ expectations, which then played a role in and affected the way they made decisions.

3.1.3 Conformity, the strength of peer pressure and social influence

Altogether, participants across the focus groups reported that perceptions and expectations of the group led them to feel pressured to conform “I laughed at them (passer-by #1) just because the rest of the group were laughing” (FG4). Most participants shared that they “did feel under pressure, but that’s mostly because, as an outsider from the group, they wouldn’t really let you in easily.” (FG6), or that they felt “under pressure because there was a lot going on and, you know, you could have made one wrong move and they might have targeted you.” (FG2).

Some participants, albeit in the minority, reported that they ended up going with the group. The motivations behind their decisions shifted throughout the scenario. At the beginning, participants who decided to follow the group were curious to “see what kind of friends they’ve (i.e., the former friends) made over the years” (FG6) since “if you like keep yourself aside from people, you’re just boring” (FG4), or they wanted to “fit in” (FG5).

As the experience progressed, the main reasons to follow the group were self-protection and need to not be “the odd one out” (FG4) or be targeted by the group: “I just… just said what he wanted to hear, so that, he wouldn’t do anything to me” (FG3). This appeared to be informed by their observations of group dynamics and expectations of how they should behave in the group.

By the end, some participants felt scared they would get into trouble, either with the group itself or the Police, given their involvement in the situation, and therefore decided to stick with the group: “Then, well I was going to go home, but then I went with the group because I don’t know, I didn’t really…” (FG1), “I didn’t want them to feel like I was [a] snitch so… and I didn’t want to go home, so just went with them” (FG5). Other participants who had initially wanted to know the group changed their minds and decided to separate from them at the end:

“I kind of wanted to go with them, at first, because I was very curious of like what it would actually be like to be part of like the group and the way it is. But in the end, I was just like, nah!” (FG2).

Altogether, this theme emphasises participants’ perceptions of the group’s features and dynamics, how this developed throughout the experience, and its influence on virtual decisions. Most participants acknowledged and recognised the role of social pressure.

3.2 Theme 2. The individual: morality, autonomy and resistance to peers

Despite participants’ awareness of peer pressure, the majority reported opposing the group in order to do the “right thing” and help the passers-by. This theme discusses the individual motivations behind participants’ decisions and consists of two subthemes, “Morally good people make morally good decisions” and “The struggle between individual and collective responsibility”.

3.2.1 Morally good people make morally good decisions

All participants expressed concern for their own and the group’s actions and how they were viewed by others. Participants’ own moral values were reported as one of the main driving forces behind their decisions: “At the end of the day, I still don’t know them, so I’m not going to go and agree with random people just to fit in. Obviously, I have my morals, and I intend to stand by them” (FG1).

Particularly, most participants valued doing the right thing, being a good person and being perceived as such: “Like, you’d feel like more bad of yourself because you weren’t like helping the people […]. And then (by helping) you won’t seem like as a bad person, basically” (FG5). For them, morality was not only seen as having the potential to influence their decisions, but also a reflection of “what type of person someone is, based on their actions and how they decide to… or what they decide to do in that situation” (FG3):

“It could also reflect the type of person you are because if you decide to, for example, record on your phone, I feel like you’d only do that just so you could fit in with the group, even if you know they are bad people, because everyone knows what’s right and wrong” (FG4).

As a result, the majority of participants constructed their own and the group’s identity around the morality of their decisions: “I just felt like saying it (saying sorry) because that’s just who I am” (FG2). This became the primary difference between them and the group: “You (participants) are good people, like they’re bad people” (FG5). For that reason, participants avoided following the group since that could “kind of corrupt” (FG3) them and make them “worse” (FG3). That is, they could lose their morals and identity in favour of those of the group: “I was a bit conscious about joining in the group because they could brainwash me against my morals and they could do things that I morally do not want to do” (FG6).

These discussions demonstrated participants’ awareness of the moral dilemmas they were presented with throughout the VR experience. For some, the moral complexity of the situation and the fact that “there’s not a wrong or right decision” (FG4) was highlighted. Others considered it a black-and-white distinction and saw themselves as either purely good or bad: “I’m still a bad person for being there” (FG4). Overall, for the majority of participants, morality represented a fundamental separation between them and the group as well as being the major driving force to oppose them.

3.2.2 The struggle between collective and individual responsibility

Throughout all focus groups, participants struggled to make sense of their position within the group and their role in the experience. On the one hand, participants emphasised that they were different from the group and that they were “just an outsider” (FG6); on the other hand, they felt part of the group and, to an extent, responsible for the group’s actions. This had implications for the decisions they made.

Given the fundamental differences participants perceived to exist between themselves and the group, the majority felt that they “just didn’t want to be involved” (FG3) from the start. Some participants reported acting in a way that would highlight these differences (“I was really out of place, so I wanted to make myself more out of place”, FG2), in order to separate themselves from the group: “They didn’t really allow me to join the group, and this is what I wanted to happen” (FG6):

“I knew straightaway that I didn’t want to be associated with them, so I knew that I would act in the way that I was…isolating myself from the group so they didn’t want to associate with me and that I didn’t want to associate with them. So, I wanted the first impression that I wasn’t a part of the group anyway and I wasn’t supposed to fit in there.” (FG4).

Equally, by opposing the group, participants wanted to reinforce that they had “the ability to choose (in the VR), even if it does feel like a bad idea” (FG6), and that they were making their “own decisions, not going along with what they (the group) are doing” (FG2). Despite wanting to assert their individuality, participants still struggled to reconcile the idea of not fitting in with the group with the fact that they were, on some level, involved with them. This can be seen throughout the focus groups, with participants reporting that they “felt guilty” (FG3) for being with the group, even if they did not partake in or agree with their actions: “I would feel bad for what they did to him, even though I am with the group in a way” (FG4). Some also reflected on the possibility of being perceived as guilty by the Police “because if they find your phone and search you, they have the evidence that you were there, and then you could be convicted for something” (FG1).

Participants appeared to attempt to resolve their internal conflict and alleviate their feelings of guilt by justifying their role and responsibility in the experience. Some felt that they had to take responsibility for and remain with the group “to say sorry on their behalf” (FG5), both to protect themselves and the passers-by:

“If I did leave as soon as I felt they were being aggressive and had the wrong attitude, then everything would have happened, but maybe it could have been worse because I wasn’t there to make the decisions that I made and I wouldn’t have distracted the group or told them to stop or said sorry to the man” (FG3).

Instead, others seemed to try to diminish their responsibility for and involvement in the situation: “I didn’t actually do anything wrong. I didn’t really help that much, like I wasn’t the one like standing in front” (FG2). Overall, this theme highlights how decisions were shaped by participants’ perceptions of themselves and their morality. In turn, through the choices they made and reflections on their role in the experience, participants constructed their identity and affirmed their autonomy and individuality.

3.3 Theme 3. The environment: making decisions in VR versus real-life

This theme discusses the influence of the setting in decision-making, both in terms of the particular scenario, characters and events, as well as the virtual as opposed to real-world setting. Two subthemes were developed to represent how the realism of the experience influenced decisions: “Real-life decisions through the “Illusion of Reality” and “Real-life decisions have real-life consequences”.

3.3.1 Real-life decisions through the “illusion of reality”

The VR experience presented an overarching scenario and series of events which for the majority of participants emulated real-life situations and elicited realistic emotions. Given the ‘illusion of reality’ created by the VR, participants were, to a certain extent, able to make decisions they felt would correspond to decisions in real life. Most conversations centred around the gang and the events. Specifically, participants talked about how the group reminded them of real-life gangs and how “some people do pressure you like that” (FG5):

“There are gangs and groups that do similar stuff to what’s happening in the VR. So it’s relatable and personal as well because I know that stuff like this happens” (FG4).

In turn, the escalating nature of the events and consequences were noted: “It just gets worse and worse as it goes on because you become more involved with the gang, making it worse for yourself” (FG1). This was seen as a realistic element that participants “could imagine […] happening in real life” (FG2), which in turn contributed to their immersion in the experience: “As you keep going, yeah, so you start thinking and it becomes more and more realistic with the decisions and stuff” (FG1). Additionally, the time-limited nature of making decisions was noted: “like real life–obviously you’re not going to have all the time in the world to make a decision” (FG1).

In some cases, a sense of familiarity with the events allowed participants to make decisions by drawing from their own experiences: “I based it off real-life experience with people like this, and I did what I would have actually done if I was in that situation” (FG2). Similarly, some participants considered how the VR element made the experience feel real: “You could still feel the emotions of what that person would be going through if they weren’t in the VR” (FG3). Therefore, by eliciting realistic feelings, the process of decision-making resembled how participants would act in real life: “Because it felt so real, I actually was able to answer with what I would have done in real life” (FG3). Overall, participants felt the VR experience had real-world authenticity. As one participant noted, this gave them “like an experience of what could happen if I was in that… a group like that” (FG3), which in turn permitted reflection on how they might react in comparable real-world situations.

3.3.2 Real-life decisions have real-life consequences

Participants discussed aspects of the VR experience that did not feel realistic, including aspects of the group and lack of real-life consequences. One of the elements noted to differ from real life was the group itself. A few participants suggested that some members of the group displayed unrealistic reactions and behaviours, as “no one would do that” (FG5), and that the characters seemed to “just act all like… hard” (FG4). Participants further commented that the decisions they made in the VR experience did not result in real-world consequences, and that they “just didn’t feel anything could happen really, because, at the end of the day it’s just virtual reality” (FG2):

“To be honest, in virtual reality, there isn’t that, do you know, that danger that’s in real life, so you feel a lot more, if you like, free with your decisions because there’s not going to be as heavy consequences. But in real life, obviously that danger is there, so when you make a decision, you’ve got to actually think about what could happen afterwards” (FG1).

Given the lack of real-life consequences, some participants reported that their decisions would have differed in real life: “I’d have done different things in real life” (FG5). Reflecting on this difference, the majority of participants noted that in real life they “wouldn’t have been in that group in the first place” (FG3) or that they “wouldn’t be there at all” (FG2). Overall, participants recognized that the difference in real-life consequences between VR and a comparable real-world scenario could result in different choices.

4 Discussion

The current study was conducted to investigate adolescent decision-making and risk-taking in a VR setting. Specifically, we considered the processes and elements shaping decisions in a context of risky and antisocial behaviour, gang involvement and peer pressure. Participants’ decisions and reflections, as well as group processes in the virtual gang and focus group discussion, will now be considered. Focus group discussions highlighted the complexity of the decision-making process and variety of responses among individuals. Often, discussions revolved around whether or not young people opposed the group in order to ‘do the right thing’ and help the passers-by. Participants discussed reasons and motivations for their decisions, including their perceptions of the group, themselves and the situation. Three themes were developed reflecting these aspects: 1) “The Gang: Perceptions, expectations and peer influence”; 2) “The Individual: Morality, autonomy and resistance to peers”; and 3) “The Environment: Making decisions in VR versus real-life”.

4.1 Morality

Participants’ wish to assist the passers-by (i.e., the victims of the group’s antisocial behaviour) was fundamentally motivated by morality. That is, participants wanted to do what was morally ‘right’. This is consistent with research highlighting adolescents’ higher propensity for morally vs. personally oriented decisions (Sommer et al., 2014). In the majority of cases, this was a product of participants’ moral reasoning and perspective-taking. Participants justified their decisions based on justice and the fairness of the group’s actions (Sullivan et al., 2008), potentially indicative of mature moral judgment (Myyrya et al., 2010), which is linked to less delinquent behaviour in adolescents (Lardén et al., 2006). Evidence indicates the developmental emergence of moral judgement is linked to cognitive development of perspective-taking (Myyrya et al., 2010). Participants showed preoccupation for how the victims would feel, and how they themselves would feel if they were in the victim’s situation, suggestive of empathy and perspective-taking.

Specifically, perspective-taking ability is related to moral emotions, such as empathetic concern for the victims (Eisenberg, 2000) and guilt, which is experienced as the result of a mismatch between an individual’s moral ideals and their actions (Stets and Carter, 2011). Both empathy and guilt seemed to be key drivers influencing participants’ moral decisions in the VR experience. Interestingly, this pathway from perspective-taking to moral-emotions to decision-making has been previously theorised as a deterrent of crime (Martinez et al., 2014). It was apparent that participants reflected upon and recognised the moral complexity and moral dilemmas they were presented with during the VR experience.

These reflections may have been especially facilitated by the approach utilised in the present study. First, the VR experience gave participants the possibility to experience different roles based on their decisions (e.g., be involved in antisocial behaviour, or risk becoming a target by speaking up for the passer-by) which may have facilitated their perspective-taking. Second, the focus group discussions exposed participants to different perspectives, experiences and decisions from fellow focus group members with, plausibly, varying levels of empathy, attitudes towards antisocial behaviour, and experience with gangs. Altogether, this may have encouraged a deeper level of reflection, emphasising perspective-taking and moral emotions, which ultimately should support participants to act in accordance with their moral values.

4.2 Moral identity

Another driving force behind participants’ decision to oppose the group and do the morally ‘right thing’ was that they considered it a direct reflection of the ‘type of person’ they were (Moshman, 2011). Hence, by acting morally, they asserted that they were a ‘good person’. This reflects how morality acts as a foundation for individual identity (Malti and Ongley, 2013). In effect, moral decisions in the VR experience served as self-verification that participants were ‘good people’ and became an opportunity to enhance their self-esteem since they acted according to their goals and values (Sullivan et al., 2008). Given the design of the study, it remains unclear whether moral identity was an already central and important consideration for participants when entering the VR. Yet, we still observed that discussions around morality naturally emerged within the focus group discussions. This suggests that the VR setting may have created the conditions to highlight moral considerations, with these becoming the basis for participants’ evaluations of themselves and the group, and ultimately influencing their decisions.

4.3 Perceptions of the group

The way participants perceived themselves also reveals a set of assumptions about the group. Upon completing the experience, most participants agreed that the group was a gang, who beyond getting involved in criminal activity was also characterised as seeking trouble. This coincides with the negative views about gangs and their behaviour expressed by young offenders, observed in other studies (Ashton and Bussu, 2020). For this reason, most participants ultimately preferred to avoid conflict with the group and tried to stick to their morals, thus reflecting their awareness that they could potentially be drawn into the gang if they became too involved (Kelly and Anderson, 2012).

Overall, this alludes to young people’s ability to recognise and understand group dynamics, gang norms and how peer pressure may present a pathway to gang involvement (Swetnam and Pope, 2001). Interestingly, as observed in the present and other focus groups, young people still understood that whilst they may have friends in a gang, that does not mean they also have to join (Annan et al., 2022). Beyond peer pressure, individual factors were recognised as important aspects contributing to gang involvement.

4.4 Autonomy vs. peer influence

Making decisions in the VR presented an opportunity for young people to assert their individuality and autonomy. By following their moral values and making morally motivated decisions, participants highlighted their separation from the group, who were seen as amoral. Since participants did not identify with the group, they were at pains to express that their decisions were independent, autonomous, and free from peer influence. Increased resistance to peer influence marks a key developmental transition in mid-to late-adolescence (Steinberg and Monahan, 2007), and is linked to lower engagement in externalising, delinquent and criminal behaviour (Allen et al., 2006; Walters, 2018).

Another driver of autonomy was the absence of virtual group membership or in-group identification. With the exception of the two ‘former school friends’, participants were informed that they were not previously acquainted with the virtual group and therefore did not (yet) belong to it. Subsequently, fundamental differences in moral values between the participant and group further reinforced their wish to remain aloof. Participants rejected the group’s identity and did not develop trust towards them, decreasing its potential to influence risk-taking behaviour (Vasquez et al., 2015; Cruwys et al., 2021).

Despite rejecting the group’s norms, social pressure was acknowledged by participants. Most reported feeling under pressure from the group, and were concerned by how the group would perceive and react to them. This is especially observed in participants’ wish not to be seen as a “snitch”, suggesting a subtle and potentially unacknowledged source of peer influence, albeit one that could arise in reference to group norms of the virtual and/or focus group (Clayman and Skinns, 2012). Considering participants’ attitudes and past experiences with gangs may shed light on the strength of peer vs. individual effects.

4.5 Cost/benefit analysis

The way adolescents reflected upon the risks presented during the VR experience played a role in their decisions. One theoretical approach by Furby and Beyth-Marom (1992) proposes that risk-taking involves choosing one of various alternatives, with all alternatives associated with some form of risk or potential loss. Decisions in the VR experience incorporated distinct types and severity of virtual risk, on a variety of timescales. For example, participants could choose between morally positive, societally-acceptable virtual decisions vs. amoral, dangerous actions which nevertheless safeguarded short-term status and personal safety (Duell et al., 2018). Participants’ decision-making involved evaluating the potential severity as well as the cost and benefits of each decision, which reflected their risk-perception (Graham et al., 2017). In the virtual setting, it appeared that participants were willing to oppose the group and incur personal risks to help the victims. Participants felt it was possible for them to disagree with the group with relatively few consequences, or leave the group altogether without repercussions. Therefore, the risks they could face for opposing the group were perceived as less severe than the risks of following the group. Partly, this may be related to adolescents’ lower aversion to ambiguity and uncertainty (i.e., adolescents are more willing to take risks if the outcome is unclear; Blankenstein et al., 2016). It may also reflect the VR setting, with minimal real-world consequences of opposing the virtual group.

4.6 Virtual vs. real world peer influence

The VR setting and its features can also explain how, despite peer pressure being recognised by participants, it did not eventually influence them to go with the group, but rather encouraged them to go against it. Particularly, the types of peers and peer relationships presented within the VR may have interacted with individual factors to influence participants’ decisions. First, research indicates that peer similarity, such as similar levels of delinquency, may account for peer selection and influence over time (Laninga-Wijnen and Veenstra, 2021). As participants were introduced in the VR scenario, they did not initially have enough information about the group to establish the presence of similarities. Instead, most seemed to highlight their dissimilarities, potentially accounting for participants’ decision not to befriend the group and limiting its influence. Furthermore, young people felt able to oppose the group given that there were no real-world consequences; and equally, there was no potential to gain real-life rewards, social or otherwise, from alignment with the virtual group (Chein et al., 2010). Instead, the researchers did observe group processes and peer influence during the focus group discussions, particularly in the form of group polarization and social desirability. The group norms appeared to mainly be of low tolerance to violence, which may have influenced participants to report similar decisions (de Boer and Harakeh, 2017). That is, some participants may have masked their true virtual decisions in order to conform to the focus group majority. This is a well-documented limitation of adopting a focus group format in research with adolescent participants (Adler et al., 2019). However, it also represents a strength and potential advantage of the group format of TiE workshops making use of the VR experience (Round Midnight Ltd, 2019): First, it may enable identification of individuals who are less resistant to peer influence (both positive and negative; i.e., a highly susceptible subgroup), by comparing focus group responses with decisions recorded on the VR headsets. Second, the group format of the TiE workshops may facilitate ‘positive’ peer influence via peer discouragement (Cavalca et al., 2013), with potential for real-world benefit.

4.7 Limitations and suggestions for future research

It is important to recognise that risk-taking and antisocial behaviour is often not a simple product of morality and peer influence. Indeed, it depends on additional individual, psychological and socio-cultural factors; for instance, a person’s willingness and predisposition to engage in antisocial behaviour, their position in the relevant social network (DeLay et al., 2022), and the presence of specific risk factors or neighbourhood characteristics. The present study focused on understanding individual reasons and motivations underlying virtual decision-making during the VR. These relied primarily on participants’ views and experiences. However, certain individual dimensions (e.g., participants’ levels of empathy or antisocial behaviour, past experiences with gangs, decisions made in the VR) were not objectively recorded during the study. These and other additional risk factors and moderators should be explored further in subsequent research, and when translating research findings into real-world interventions. This could serve two main purposes, namely, understanding the factors and mechanisms through which the intervention may be tackling antisocial behaviour and gang involvement, as well as identifying subgroups who may benefit more from the intervention.

4.8 Conclusion and practical implications

The VR experience provided an immersive, compelling environment for adolescents to gain first-hand ‘knowledge through experience’ of a virtual encounter with a gang. Young people reported authentic emotional responses, and many perceived the group, setting and events to be realistic. This provided an opportunity for young people to explore decision-making in a safe, virtual environment, an advantage that has been highlighted elsewhere (Sütfeld et al., 2017). Participants commented on the experience of events snowballing out of control, an insight with potential real-world value. A range of consequences was experienced, both virtual and external (i.e., threat of being targeted by the gang, getting in trouble with the police), and real and internal (i.e., experience of decisions shaping one’s identity, impact on self-esteem, experience of guilt by association, reflections on behaviour in a comparable real-world situation). Aspects of the VR experience promoted the ‘illusion of reality’, including context-realism and perspectival-fidelity (Ramirez and LaBarge, 2018; Slater, 2019). We propose that VR experiences such as this, delivered in an appropriately sensitive TiE workshop setting, provide a valuable learning experience for young people, stimulating discussion on sensitive, important topics. This is a promising avenue for research, primary prevention and early intervention which should be further explored in the future.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the focus group discussions represent personal perspectives and experiences of participants. It is therefore not deemed appropriate for the data to be made publicly available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author, SBH cy5idXJuZXR0aGV5ZXNAYmhhbS5hYy51aw==.

Ethics statement

The study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Ethical Review Committee at the University of Birmingham. The participants’ parents/guardians provided their written informed consent for them to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) and and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SBH and JAK conceived the study. All authors contributed to study design. DB and LS collected, coded and analysed the data with JAK providing guidance. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by a British Academy/Leverhulme Small Research Grant (SRG19\190169) supported by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy to SBH and JAK.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the essential contribution of Round Midnight Ltd. and, in particular, Phil Hyde and Sami Cornick for their role in this collaboration, and specifically for making Virtual_Decisions: GANGS available for research, equipment loan, technical expertise, facilitation of participant recruitment, opportunities to shadow VR-TiE workshops, and for innumerable helpful and interesting discussions along the way. We are tremendously grateful for the contributions of participating schools, teachers, parents/guardians and pupils, without whom this research would not have been possible. We hope this research contributes, in some small way, to addressing issues affecting your local communities and young people. We are grateful to Dr. Michael Larkin for helpful discussions around developing the semi-structured topic guide.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frvir.2023.1142241/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdul Rahim, E., Duenser, A., Billinghurst, M., Herritsch, A., Unsworth, K., Mckinnon, A., et al. (2012). “A desktop virtual reality application for chemical and process engineering education,” in Proceedings of the 24th Australian computer-human interaction conference (New York: Association for Computing Machinery), 1–8. doi:10.1145/2414536.2414537

Adler, K., Salanterä, S., and Zumstein-Shaha, M. (2019). Focus group interviews in child, youth, and parent research: An integrative literature review. Int. J. Qual. Methods 18, 7274. doi:10.1177/1609406919887274

Allen, G., and Harding, M. (2021). Knife crime statistics house of commons library. Avaliable At: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn04304/.

Allen, J. P., Porter, M. R., and McFarland, F. C. (2006). Leaders and followers in adolescent close friendships: Susceptibility to peer influence as a predictor of risky behavior, friendship instability, and depression. Dev. Psychopathol. 18 (1), 155–172. doi:10.1017/s0954579406060093

Annan, L. G., Gaoua, N., Mileva, K., and Borges, M. (2022). What makes young people get involved with street gangs in London? A study of the perceived risk factors. J. community Psychol. 50 (5), 2198–2213. doi:10.1002/jcop.22767

Ashton, S. A., and Bussu, A. (2020). Peer groups, street gangs and organised crime in the narratives of adolescent male offenders. J. Crim. Psychol. 10 (4), 277–292. doi:10.1108/jcp-06-2020-0020

Bandura, A. (2006). “Mechanisms of moral disengagement,” in Insurgent terrorism. Editor G. Cromer (London: Routledge), 85–115.

Barreda-Angeles, M., Serra-Blasco, M., Trepat, E., Pereda-Baños, A., Pàmias, M., Palao, D., et al. (2021). Development and experimental validation of a dataset of 360°-videos for facilitating school-based bullying prevention programs. Comput. Educ. 161, 104065. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104065

Benish-Weisman, M., Daniel, E., Schiefer, D., Möllering, A., and Knafo-Noam, A. (2015). Multiple social identifications and adolescents' self-esteem. J. Adolesc. 44, 21–31. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.06.008

Blankenstein, N. E., Crone, E. A., van den Bos, W., and van Duijvenvoorde, A. C. (2016). Dealing with uncertainty: Testing risk-and ambiguity-attitude across adolescence. Dev. Neuropsychol. 41 (1-2), 77–92. doi:10.1080/87565641.2016.1158265

Brantingham, P. J., Yuan, B., and Herz, D. (2021). Is gang violent crime more contagious than non-gang violent crime? J. Quant. Criminol. 37, 953–977. doi:10.1007/s10940-020-09479-1

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Brechwald, W. A., and Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. J. Res. Adolesc. 21 (1), 166–179. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x

Cavalca, E., Kong, G., Liss, T., Reynolds, E. K., Schepis, T. S., Lejuez, C. W., et al. (2013). A preliminary experimental investigation of peer influence on risk-taking among adolescent smokers and non-smokers. Drug alcohol dependence 129 (1-2), 163–166. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.09.020

Chein, J., Albert, D., O’Brien, L., Uckert, K., and Steinberg, L. (2010). Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain’s reward circuitry. Dev. Sci. 14 (2), F1–F10. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01035.x

Children’s Commissioner (2019). Children’s commissioner for england: Annual report and accounts 2019-20. Avaliable At: https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/occ-annual-report-and-accounts-2019-20.pdf.

Children’s Society (2022). Disrupting exploitation programme. Avaliable At: https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/what-we-do/our-work/child-criminal-exploitation-and-county-lines.

Chrysoulakis, A. P. (2020). Morality, delinquent peer association, and criminogenic exposure:(How) does change predict change? Eur. J. Criminol. 19, 282–303. doi:10.1177/1477370819896216

Clayman, S., and Skinns, L. (2012). To snitch or not to snitch? An exploratory study of the factors influencing whether young people actively cooperate with the police. Polic. Soc. 22 (4), 460–480. doi:10.1080/10439463.2011.641550

Cruwys, T., Greenaway, K. H., Ferris, L. J., Rathbone, J. A., Saeri, A. K., Williams, E., et al. (2021). When trust goes wrong: A social identity model of risk taking. J. Personality Soc. Psychol. 120 (1), 57–83. doi:10.1037/pspi0000243

de Boer, A., and Harakeh, Z. (2017). The effect of active and passive peer discouragement on adolescent risk taking: An experimental study. J. Res. Adolesc. 27 (4), 878–889. doi:10.1111/jora.12320

DeLay, D., Burk, W. J., and Laursen, B. (2022). Assessing peer influence and susceptibility to peer influence using individual and dyadic moderators in a social network context: The case of adolescent alcohol misuse. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 46 (3), 208–221. doi:10.1177/01650254221084102

Densley, J. A., Adler, J. R., Zhu, L., and Lambine, M. (2017). Growing against gangs and violence: Findings from a process and outcome evaluation. Psychol. violence 7 (2), 242–252. doi:10.1037/vio0000054

Duell, N., Steinberg, L., Icenogle, G., Chein, J., Chaudhary, N., Di Giunta, L., et al. (2018). Age patterns in risk taking across the world. J. youth Adolesc. 47 (5), 1052–1072. doi:10.1007/s10964-017-0752-y

Eisenberg, N. (2000). Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 51 (1), 665–697. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.665

Esbensen, F. A., Peterson, D., Taylor, T. J., Freng, A., Osgood, D. W., Carson, D. C., et al. (2011). Evaluation and evolution of the gang resistance education and training (GREAT) program. J. Sch. Violence 10 (1), 53–70. doi:10.1080/15388220.2010.519374

Forsyth, C. J., Dick, S. J., Chen, J., Biggar, R. W., Forsyth, Y. A., and Burstein, K. (2018). Social psychological risk factors, delinquency and age of onset. Crim. Justice Stud. 31 (2), 178–191. doi:10.1080/1478601x.2018.1435618

Foulkes, L., Leung, J., Fuhrmann, D., Knoll, L., and Blakemore, S-J. (2018). Age differences in the prosocial influence effect. Dev. Sci. 21 (6), e12666. doi:10.1111/desc.12666

Frisby-Osman, S., and Wood, J. L. (2020). Rethinking how we view gang members: An examination into affective, behavioral, and mental health predictors of UK gang-involved youth. Youth justice 20 (1-2), 93–112. doi:10.1177/1473225419893779

Fryda, C. M., and Hulme, P. A. (2015). School-based childhood sexual abuse prevention programs: An integrative review. J. Sch. Nurs. 31 (3), 167–182. doi:10.1177/1059840514544125

Furby, L., and Beyth-Marom, R. (1992). Risk taking in adolescence: A decision-making perspective. Dev. Rev. 12 (1), 1–44. doi:10.1016/0273-2297(92)90002-j

Graham, L., Jordan, L., Hutchinson, A., and de Wet, N. (2017). Risky behaviour: A new framework for understanding why young people take risks. J. Youth Stud. 21 (3), 324–339. doi:10.1080/13676261.2017.1380301

Grigorenko, E. L. (2011). Handbook of juvenile forensic psychology and psychiatry. New York: Springer Science and Business Media.

Haddad, A. D., Harrison, F., Norman, T., and Lau, J. Y. (2014). Adolescent and adult risk-taking in virtual social contexts. Front. Psychol. 5, 1476. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01476

Halldorsson, B., Hill, C., Waite, P., Partridge, K., Freeman, D., and Creswell, C. (2021). Annual research review: Immersive virtual reality and digital applied gaming interventions for the treatment of mental health problems in children and young people: The need for rigorous treatment development and clinical evaluation. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 62 (5), 584–605. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13400

HM Government (2015). Preventing youth violence and gang involvement. Avaliable At: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/418131/Preventing_youth_violence_and_gang_involvement_v3_March2015.pdf.

HM Government (2022). Safeguarding children and young people who may be affected by gang activity. Avaliable At: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/189392/DCSF-00064–2010.pdf.pdf.

Home Office (2018). Criminal exploitation of children and vulnerable adults: County lines guidance. Avaliable At: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/criminal-exploitation-of-children-and-vulnerable-adults-county-lines/criminal-exploitation-of-children-and-vulnerable-adults-county-lines.

Home Office (2015). Have you got what it takes? Tackling gangs and youth violence. Avaliable At: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/512203/gangs-youth-violencearchive.pdf.

Hsieh, M. S., Lee, F. P., and Tsai, M. D. (2010). A virtual reality ear ossicle surgery simulator using three-dimensional computer tomography. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 30 (1), 57–63.

Jackson, A., and Vine, C. (2013). Learning through theatre: The changing face of theatre in education. Oxford: Routledge.

Kavanagh, S., Luxton-Reilly, A., Wuensche, B., and Plimmer, B. (2017). A systematic review of virtual reality in education. Themes Sci. Technol. Educ. 10 (2), 85–119.

Kelly, S. E., and Anderson, D. G. (2012). Adolescents, gangs, and perceptions of safety, parental engagement, and peer pressure. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. health Serv. 50 (10), 20–28. doi:10.3928/02793695-20120906-99

Klein, M., Kerner, H. J., Maxson, C., and Weitekamp, E. (2001). The Eurogang paradox: street gangs and youth groups in the US and Europe. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Knoll, L. J., Magis-Weinberg, L., Speekenbrink, M., and Blakemore, S. J. (2015). Social influence on risk perception during adolescence. Psychol. Sci. 26 (5), 583–592. doi:10.1177/0956797615569578

Kozlov, M. D., and Johansen, M. K. (2010). Real behavior in virtual environments: Psychology experiments in a simple virtual-reality paradigm using video games. Cyberpsychology, Behav. Soc. Netw. 13 (6), 711–714. doi:10.1089/cyber.2009.0310

Krahé, B., and Knappert, L. (2009). A group-randomized evaluation of a theatre-based sexual abuse prevention programme for primary school children in Germany. J. Community & Appl. Soc. Psychol. 19 (4), 321–329. doi:10.1002/casp.1009

Krettenauer, T., Colasante, T., Buchmann, M., and Malti, T. (2014). The development of moral emotions and decision-making from adolescence to early adulthood: A 6-year longitudinal study. J. youth Adolesc. 43 (4), 583–596. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9994-5

Kroger, J. (2005). “Identity development during adolescence,” in Blackwell handbook of adolescence. Editors G. R. Adams, and M. Berzonsky (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.), 205–226. doi:10.1002/9780470756607

Krohn, M. D., Ward, J. T., Thornberry, T. P., Lizotte, A. J., and Chu, R. (2011). The cascading effects of adolescent gang involvement across the life course. Criminol. Interdiscip. J. 49 (4), 991–1028. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2011.00250.x

Landsheer, J. A., and Dijkum, V. C. J. (2005). Male and female delinquency trajectories from pre through middle adolescence and their continuation in late adolescence. Adolescence 40 (160), 729–748.