- 1Department of marketing, University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany

- 2Grenoble École de Management, Grenoble, France

The application of augmented reality (AR) is receiving great interest in e-commerce, m-commerce, and brick-and-mortar-retailing. A growing body of literature has explored several different facets of how consumers react to the upcoming augmented shopping reality. This systematic literature review summarizes the findings of 56 empirical papers that analyzed consumers’ experience with AR, acceptance of AR, and behavioral reactions to AR in various online and offline environments. The review synthesizes current knowledge and critically discusses the empirical studies conceptually and methodologically. Finally, the review outlines the theoretical basis as well as the independent, mediating, moderating, and dependent variables analyzed in previous AR research. Based on this synthesis, the paper develops an integrative framework model, which helps derive directives for future research on augmented shopping reality.

Introduction

The augmented reality (AR) technology supplements the real world with virtual elements. These supplements are often visual like in the mobile game Pokémon Go, where the digital Pokémons extend the physical environment (Hamari et al., 2019), but they could also address other senses like hearing, for example through interactive audio AR in participatory performance (Nagele et al., 2021), smelling in synesthetic visualization of odors with an odor detector (e-nose; Ward et al., 2020) or tasting by a pseudo-gustatory display (Narumi et al., 2011). Several reports have recently ranked AR as one of the top 10 technology trends (Marr, 2020; Samsung Business Insights, 2020). In a similar vein, the report of Euromonitor International describes “phygital reality” as a top 10 global consumer trend in 2021 (Westbrook and Angus, 2021). Phygital reality is understood as a hybrid bridging the physical and digital world regarding various aspects of human behavior, including living, working, and shopping. According to this report, half of the consumers younger than 45 years have used augmented reality and virtual reality in 2020 (Westbrook and Angus, 2021). Evidently, consumers are increasingly used to integrate this technology into their lives. For example, the Covid-19 pandemic caused lockdowns in 2020 and 2021, calling for social distancing in many countries. Technologies like video conferencing rapidly became widespread, shifting personal and business contacts to virtual rooms. With such developments boosting people’s view on technology (Hacker et al., 2020) and the fast diffusion of devices that principally enable AR-based applications, the relevance of the AR technology will continue to grow. This is particularly true as these mobile devices are often considered “constant companions” (e.g., smartphones or tablet computers). Accordingly, the AR market is expected to reach a US $75 billion in revenue by 2023 (vXchange, 2020) and the global AR and VR market revenue of US $161.1 billion by 2025 (Vynz Research, 2020). In their opinion paper, Dwivedi et al. (2021), p. 16) recently concluded that augmented reality is still in its infancy, but they forecast that it “will be as prevalent in the marketing of the future as the Internet is today”.

The AR technology has already entered the shopping world. Companies and retailers can feasibly apply AR in e-commerce and m-commerce (e.g., Javornik, 2016b; Baek et al., 2018; Beck and Crié, 2018). In these online retailing contexts, AR enables consumers to visualize or even virtually try-on products, such as apparel, eyewear, or cosmetics. AR-enabled virtual try-ons or virtual fitting rooms allow consumers to make better choices. As a positive side effect, this may eventually help decrease the excessive return rates of apparel ordered online (Narvar, 2017). AR can also be helpful in brick-and-mortar retailing (Hilken et al., 2018; Caboni and Hagberg, 2019), where the technology can enhance the physical products or shelves with digital information (e.g., van Esch et al., 2019; Wedel et al., 2020; Joerß et al., 2021).

As an umbrella term for AR applications in shopping and retailing environments, we coin the term augmented shopping reality (ASR). However, despite the aforementioned benefits and wide diffusion of AR-enabling devices, the diffusion of ASR is still in an early phase. According to a recent WBR (2020) insights report, only 1 out of 100 retailers is currently using AR. Many companies state that the lack of the ability to currently support these features is the main obstacle. Yet, most of the surveyed managers report that they plan to adopt the technology in the near future. Online sellers and offline retailers require more knowledge about how consumers react to the technology and how to design effective AR applications. For example, based on research insights, ASR could potentially be more effective in addressing different senses when utilizing the crossmodal design paradigm (Ward et al., 2021) which is known to influence decision processes (Deliza and Macfie, 1996) and perceived value (Teas and Agarwal, 2000). As another example, ASR could be more effective making use of the latest research findings on the design of AR information at the point of sale (Hoffmann et al., 2022). Academic ASR research is developing with tremendous speed, but the growing body of literature is very diverse and fragmented in that the extant studies cover different AR applications, shopping settings, and product categories, with each study putting the spotlight on a specific context. Also, the findings are published in different fields, such as business (e.g., Rauschnabel et al., 2018; Jessen et al., 2020; Smink et al., 2020), marketing (e.g., Hilken et al., 2017), retailing (e.g., Heller et al., 2019a,b; Pantano et al., 2017; Watson et al., 2020), information science (e.g., Huang and Liao, 2015; Brito and Stoyanova, 2018; McLean and Wilson, 2019), and psychology (e.g., Choi and Choi, 2020). Consequently, notable voids exist in the literature, among others, regarding whether or not AR taps the same or different ASR functionalities in e-/m-commerce and brick-and-mortar-retailing. Marketers need to know which ASR functionality they can use in which setting, for which product categories, and how they have to design the ASR for different applications. Another void emerges in how the cluttered empirical findings about user experiences, technology acceptance, marketing outcomes, etc. can be integrated into a general customer-centric framework to understand the whole customer journey. To resolve this confusion and provide scholars, managers and ASR designers with a cohesive understanding of the current state-of-art, a systematic integration is needed. To fill these voids, this paper synthesizes the relevant literature’s achievement, develops a new holistic theoretical framework by integrating past empirical findings and enhancing them based on conceptual works, and then outlines future trajectories and research directions.

The paper will answer the following research questions: 1) Are there contingencies between the different ASR functionalities (informing, visualizing, trying-on, and placing) and the context in which they are used, including the retailing channel, product category and AR device? 2) Which theories build the foundation for empirical AR research on consumer behaviors in ASR, and how can these partial explanations be integrated into a sound framework? 3) Which models of consumer behavior have been developed and empirically tested, especially for the different contexts of ASR? 4) Which methodologies have scholars applied, and which research methods are needed in the future given the more mature state of the field? 5) How can the formal functions of the predictor, mediator, and outcome variables of previous AR studies be organized, and which moderators and boundary conditions are relevant for developing one integrative framework model? 6) What are the research gaps in the consumer behavior literature on ASR, and which directions are most relevant for further investigations in this context?

We conduct a systematic literature review to assess the current state-of-the-art of ASR research. The review covers 56 papers, which report empirical studies on consumer behavior in ASR. In particular, we highlight which ASR functions (informing, visualizing, trying-on, and placing) are tested in shopping environments, such as e-commerce, m-commerce, and brick-and-mortar retailing. We systemize and integrate the theoretical basis and conceptual models explored in past research. Footing on this synthesis, the paper develops an integrative framework model that helps derive directions for future research on consumer behavior in ASR. For the first time, we critically review the methodological approaches of past papers and evaluate the research stream from a methodological point of view to provide recommendations for improving the quality of future research. The target audience of this systematic literature review is researchers in marketing, consumer behavior, retailing, media design, and computer science, as well as practitioners in these domains.

Defining augmented shopping reality

Augmented reality

The AR technology combines real and virtual objects in such a way that they appear to coexist in the same space (Azuma et al., 2001; van Krevelen and Poelman, 2010; Skarbez et al., 2021). To this end, the technology superimposes digital 3D objects in relation to objects in the analogue world on a screen or any other device display (Azuma, 1997). Furthermore, as a unique property of the AR technology, this augmentation of the real world occurs in real-time (Azuma, 1997; Carmigniani et al., 2011), such that users are able to interact with the virtual objects (Zhou et al., 2008). For these reasons, augmentation of the real world with a computer-generated layer and interactivity can be considered the two main features of augmented reality (Javornik, 2016a).

The technology, and thus the augmentation of reality, can be achieved on many different types of displays and devices. First, there are fixed interactive screens (e.g., virtual mirrors), computer monitors, and laptops. A second category is portable and handheld devices, such as smartphones, smartwatches, tablet computers, or even optical see-through glasses (Carmigniani et al., 2011; Kim and Hyun, 2016; Brito and Stoyanova, 2018). Mobile devices are omnipresent nowadays, so they likely boost the diffusion of AR in various settings, opening the technology’s untapped potential. The third category comprises displays of wearable technologies proximal to the user. These include head-mounted displays, such as smart glasses or helmets (e.g., Microsoft HoloLens), which overlay the user’s field of vision with digital objects (e.g., Brito and Stoyanova, 2018; Rauschnabel 2018; Rauschnabel et al., 2018). Finally, in the more distant future, the application of implanted devices, such as lenses, is highly probable (Flavián et al., 2019).

Different fields analyze AR and its practical applications. Research in information technology and computer science explores the technical and functional aspects of the AR technology, such as precise control or exact object positioning (Zhou et al., 2008; Carmigniani et al., 2011; Chae et al., 2018; Kytö et al., 2018). Scholars from different disciplines have also analyzed AR applications through the lenses of their fields, including medicine (Berryman, 2012; Vávra et al., 2017), psychology (Botella et al., 2005), education (Di Serio et al., 2013; Bower et al., 2014; Harley et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2017), gaming (Rauschnabel et al., 2017; Hamari et al., 2019), or tourism (Aluri, 2017; Chung et al., 2018; tom Dieck and Jung, 2018). In the business literature, the AR technology has been studied with a focus on production and industry 4.0 (Masood and Egger, 2019; Kaasinen et al., 2020) or advertising and branding (Hopp and Gangadharbatla, 2016; Mauroner et al., 2016; Yaoyuneyong et al., 2016; de Ruyter et al., 2020). In this paper, we focus on the applications in retailing environments. Virtual reality (VR) also provides innovative applications for marketing and retailing, and researchers have already analyzed these applications (Boyd and Koles, 2019; Herz and Rauschnabel, 2019; Hudson et al., 2019; van Berlo et al., 2021). However, in contrast to AR, VR creates a complete digital environment where users interact with virtual objects in real-time. AR superimposes computer-generated objects over the real world (Flavián et al., 2019). Therefore, this technology is highly interesting for retailing contexts, such as stationary retailing where AR can provide additional information to physical products or e-tailing where AR can help consumers virtually try-on products. Hence, we focus on AR in this paper.

Augmented shopping reality

AR can be incorporated in retailing settings in several ways, including but not limited to the functionalities of informing, visualizing, trying-on, and placing. We build our typology on prior research that has already suggested classifications of AR functionalities in general (e.g., Azuma, 1997) and in retailing contexts. For example, Tan et al. (2021) identified four uses of AR in retailing. However, these categories (entertain, educate customers, evaluate product fit, enhance the postpurchase consumption experience) describe how consumers use the AR technology, while our review will shift the focus on the technological design to disentangle the different functionalities and their uses. Prior research stressed that AR in shopping settings could be used to extend the product, the consumers’ body, and the consumers’ environment (Javornik 2016a; Hoffmann et al., 2022). Integrating these conceptual foundations, we propose that the AR technology can be used to enhance and support different steps in the customer journey, from searching information over visualizing products to virtually trying on products or virtually placing objects in the consumers’ environment. We accordingly claim that AR provides at least four main groups of functionalities in shopping and retailing settings; we label these ASR functions as informing, visualizing, trying-on, and placing. As a striking advantage of this typology, AR applications can be objectively assigned to the different categories based on their technological design.

Informing

The AR technology can be used to enhance physical objects (including products) with virtual information (Hoffmann et al., 2022). This function has been labelled ‘annotation’ by Azuma (1997) and is related to Tan et al.’s (2021) educate category. Tourism agencies use AR to deliver location-based information about sights, or museums provide details about exhibits (CorfuAR; Kourouthanassis et al., 2015). Star view apps (Night Sky, Sky View, Star Walk, etc.) are further examples of how AR can deliver context-specific information. In shopping contexts, retailers can apply AR in brick-and-mortar stores to supplement the physical environment with product information (Hilken et al., 2018), such as offering further details about books (Spreer and Kallweit, 2014) or food products (Joerß et al., 2021; Hoffmann et al., 2022). Virtual overlays concern the product or specific areas on the packaging and even entire shelves. The conveyed details can be technical details or information about the product origin, ingredients, allergy warnings, etc. As a unique benefit that sets AR systems apart from other traditional means of communication, the AR-enabled information can even provide personalized information (Hsu et al., 2021) without physically altering the product design or its packaging. This aspect is particularly interesting to physical stores because they operate under much stronger space-related constraints in terms of information presentation than do online or mobile shops. In this way, AR opens up virtually unlimited space in the digital world for physical objects at the point of sale. The technology provides shoppers with access to the required information exactly at the place and the time when they need it (Joerß et al., 2021; Hoffmann et al., 2022).

Visualizing

The visualization function allows users to see a virtual 3D model of a product or visualize specific aspects of it or certain benefits (Azuma, 1997). Users can interact with the model and turn it to view it from different angles or they might customize the size, colors, and shape. The function has been tested in empirical research, for example, regarding the mobile app of the German car magazine AUTO BILD that can be scanned to experience virtual context (Rese et al., 2017). Other studies tested AR applications to visualize shoes (Brito and Stoyanova, 2018) or mugs (Huynh et al., 2019).

Trying-on

Virtual try-ons allow users to augment themselves with virtual objects. Users of this type of AR application can choose a piece of apparel, shoes, eyewear, cosmetics, or watches and test these products on their own body or their own face in a virtual fitting-room or through a virtual mirror (e.g., Javornik, 2016b; Hilken et al., 2017; Poushneh and Vasquez-Parraga, 2017; Yim et al., 2017). In particular, sellers of apparel (e.g., Huang and Liao, 2015; Baytar et al., 2020), eyeglasses and sunglasses (e.g., Ray-Ban Virtual Try-On, Mister Spex), or cosmetics (e.g., Shiseido AR makeup mirror) have developed such virtual try-ons. This AR function is frequently applied in e-commerce and m-commerce to allow consumers try on products in the digital world where testing the product before ordering it is often not feasible or possible. As they help avoid suboptimal decisions, virtual try-ons may be one way to reduce the unreasonably high return rates of non-fitting products. Notably, even brick-and-mortar stores have adapted AR try-on applications, such as virtual mirrors on stationary wide-screen monitors for apparel (e.g., Yuan et al., 2021).

Placing

The AR function placing (also termed ‘environmental embedding’ by Hilken et al., 2017 or ‘evaluate’ by Tan et al., 2021) refers to the augmentation of the physical surrounding of the user with virtual elements. In shopping and retailing contexts, this application is frequently employed for home furniture (e.g., Javornik, 2016b; Heller et al., 2019a; Rauschnabel et al., 2019). Furniture planners (e.g., IKEA place, Cimagine) invite users to scan or click objects of the catalogue, website or app and place these elements virtually in their physical rooms. Furniture planners support consumers in imagining how these pieces of furniture would look in their rooms. Other applications are paintings (Mishra et al., 2021) or wall paint (Hilken et al., 2020).

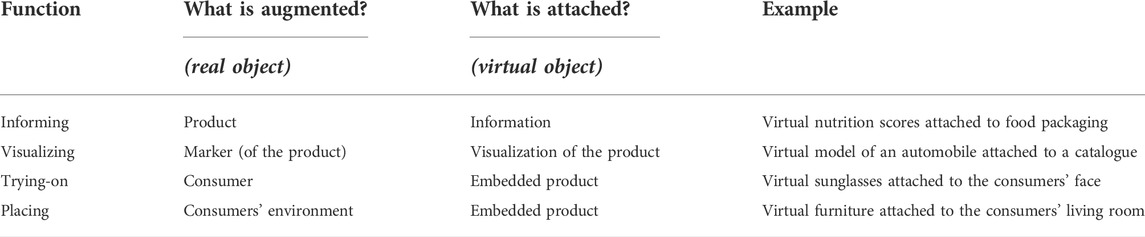

Summing up, in shopping contexts, these four AR functionalities differ primarily with regard to the object that is recorded by the device’s camera and which is augmented on the display (the product, a marker, the consumer, or the consumer’s physical surroundings). Secondly, the functionalities differ regarding the attached virtual objects (information, product visualization, and embedded product). Table 1 provides a systematic overview of these differences. Notably, the functions of trying-on and placing both involve a demonstration of the product (like visualizing) but embed the virtual product either in the image of the consumer (trying-on) or the environment (placing). For visualizations of these different functions, we refer readers to some of the empirical articles in our literature review that include pictures of the studied AR technology. For the function ‘informing’, for example, see the shopping apps used by Hoffmann et al. (2022), Figure 6, 7), Joerß et al. (2021), p. 520), or Speer and Kallweit. (2014), p. 22). For the ‘visualizing’ function, consider the CluckAR-app shown by van Esch et al. (2019), p. 39) or the AUTO BILD ad shown by Rese et al. (2017), p. 311). Examples for the ‘trying-on’ function are the Ray Ban Website for sunglasses or the Tissot Website for watches shown by Yim et al. (2017), p. 101). For the function ‘placing’, see the IKEA tool shown by Javornik. (2016b), p. 97).

Arguably, some functionalities may benefit specific product categories (e.g., trying-on for apparel, informing for food). Still, the product categories and functionalities are two distinct aspects that need to be considered separately. For example, AR can add product information to a sweater in a physical store (informing), can visualize the sweater in 3D based on a picture in a catalogue (visualizing), help consumers virtually try on the sweater in e-commerce (trying-on) or the technology can virtually put the sweater in the consumer’s wardrobe (placing).

Methods

Search strategy

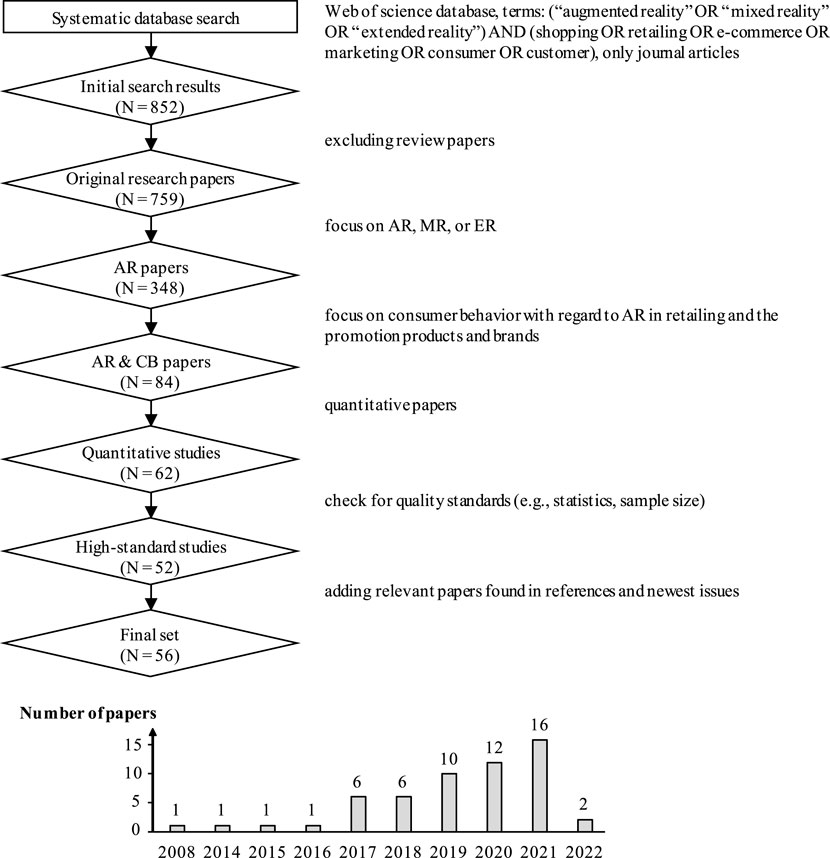

We conduct a systematic literature review to give an overview of the research in the field of consumer behavior in ASR (see Figure A1). We started with a systematic search process following the standard guidelines for systematic reviews (Moher et al., 2009; Palmatier et al., 2018; Snyder, 2019).

In a first step, we consulted the Web of Science database to search papers using the following terms: (“augmented reality” OR “mixed reality” OR “extended reality”) AND (shopping OR retailing OR e-commerce OR marketing OR consumer OR customer). We allowed only published journal articles. Our initial search resulted in 852 records, which were reduced to 759 when excluding review articles in the search mask (see Figure A1).

In a second step, we cleansed the set of papers following pre-defined criteria. We first inspected the title and abstract to include only relevant papers. If necessary, we read the papers to decide whether or not they are appropriate. Selecting only papers with a clear focus on AR, MR, or ER reduced the set of papers to 348. For example, we dropped articles covering the VR technology, but not AR (Hudson et al., 2019). We extracted 84 papers that focus on consumer behavior with regard to AR in retailing to promote products or brands. We excluded studies limited to the technological development, such as comparing different AR technologies. Given our scope on retailing and e-commerce, we also excluded papers on advertising and branding (e.g., Hopp and Gangadharbatla, 2016; Yaoyuneyong et al., 2016) or active catalogues (Rese et al., 2014). We further excluded research that does not model the consumer process (Tan et al., 2021). We kept only empirical studies with a quantitative methodology, leaving 62 papers. We decided to exclude research with a qualitative approach (e.g., Olsson et al., 2013; Scholz and Duffy, 2018; Romano et al., 2021) from our analysis because these papers cannot be integrated into our systematic reviewing approach. Still, we will use these papers to enrich the evaluation and interpretation of the state-of-the-art in the discussion section. Finally, we excluded papers that did not pass certain predefined quality standards (e.g., no statistical inference tests or very small sample sizes). After this cleansing process, the set was reduced to 52 suitable papers.

In a third step, we inspected the references of the various AR articles and the latest issues of journals that frequently publish AR-related articles in marketing and consumer research. We include four additional papers, ending up with 56 papers for our systematic literature review.

The papers are published in journals with a focus on Marketing, Retailing, Information Science, and Technology. The highest share of papers in the literature review was published in the Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services (17), followed by the Journal of Business Research (8), Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science (3), Journal of Retailing (2), Journal of Interactive Marketing (2), Psychology and Marketing (2), Internet Research (2), International Journal of Advertising (2), International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management (2), and Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management (2). Single papers were identified in several other outlets: Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Computers in Human Behavior, Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, Informatics, Information Technology and People, Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, International Journal of Information Management, International Journal of Semantic Computing, Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, Journal of Internet Commerce, Journal of Marketing Management, Technological Forecasting, and Social Change, and Transactions on Marketing Research. The number of papers increases in the last years (2008: 1, 2014: 1, 2015: 1, 2016: 1, 2017: 6, 2018: 6, 2019: 10, 2020: 12, 2021: 16, 2022: 2).

Data analysis

We divide the data analysis process into four thematic sections: applications, theories, consumer processing models, and methods. First, in terms of applications, we explore the contexts in which the AR technology is applied (e-/m-commerce vs. brick-and-mortar). We analyze for which product categories ASR is applied, which ASR functionality is relevant (informing, visualizing, trying-on, placing), and which devices are used (stationary monitors, PC/laptops, mobile device, or head-mounted and wearable devices). Second, we summarize the theoretical basis of the analyzed studies. Third, we identify the main components of the consumer research models that were addressed in the reviewed papers. These models can be formally decomposed into 1) predictors, 2) the mediator variables that capture the underlying process, 3) the outcomes, and 4) the moderator variables that capture relevant boundary conditions or contingencies. Beyond their formal position in the consumer-processing model, we systemize the variables with respect to their conceptual contribution. Specifically, we distinguish the two major categories that capture the defining properties of the AR technology, namely, augmentation and interaction. We also consider three categories that describe consumers’ mental processing (user experience, perceived user benefits, and concerns/barriers). The remaining categories refer to technology acceptance and consumption behavior. Finally, we examine the research methods (survey, experiments) and type of manipulation (if applicable).

Findings

Applications

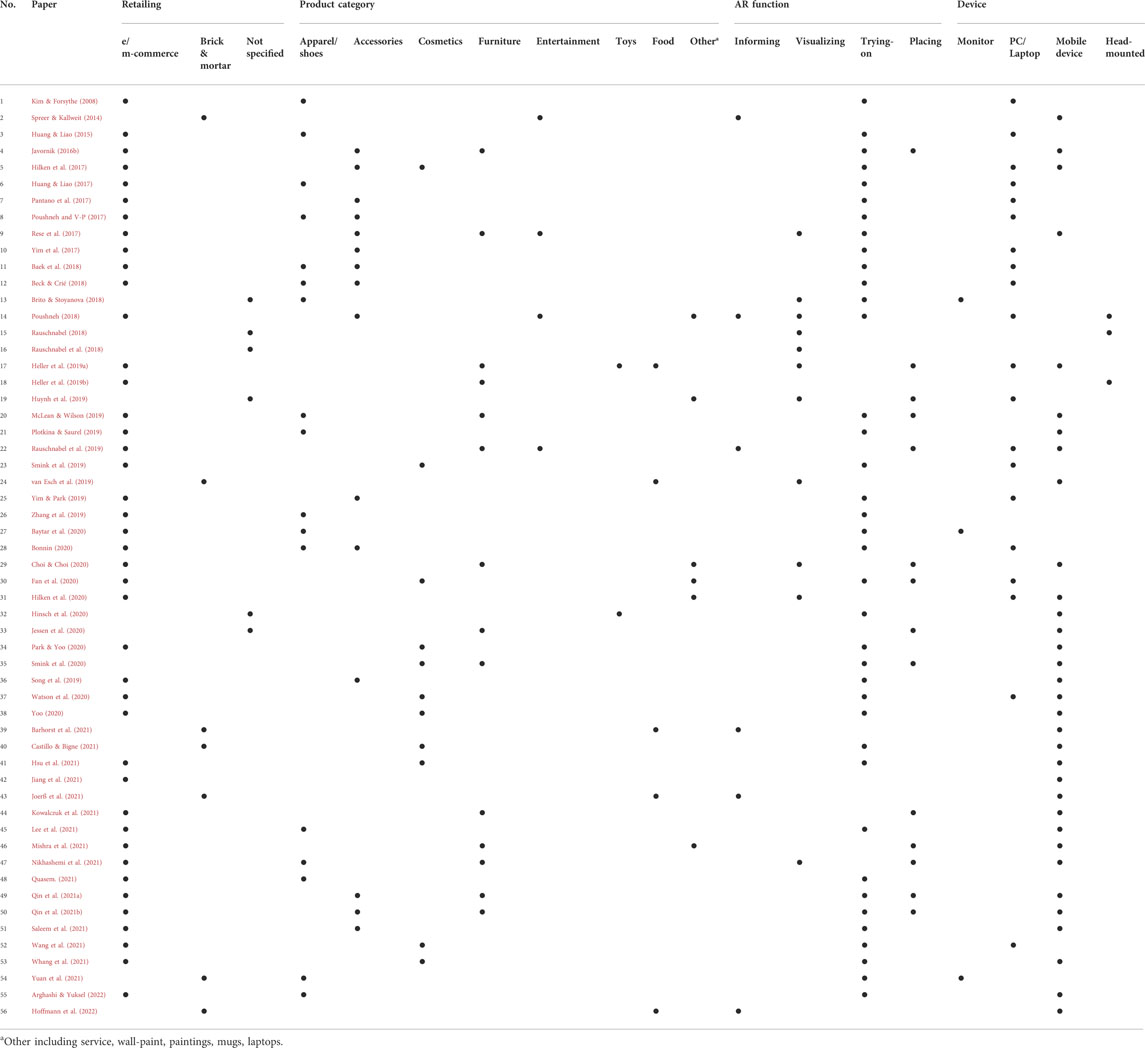

In the first step of the review, we examine how AR is used in retailing settings from the perspective of applications and functionalities. As outlined in Table 2, we consider various retail settings (e-/m-commerce vs. physical stores; Carboni and Hagbeg, 2019) as past research has not yet systematically compared these perspectives, which may enable and require different AR functionalities. We then investigate the product categories that have been researched so far. The categories are extracted through an inductive process while reviewing the literature. Next, we consider the AR functionalities building on the classification developed above (informing, visualizing, trying-on, and placing). Finally, we consider the AR devices, including monitors, PC/laptops, mobile devices, and head-mounted devices (Flavián et al., 2019). While assigning the reviewed articles to these categories is a rather descriptive process, we explore—for the first time in a systematic manner—the contingencies of the retailing setting, the product categories, the AR functions, and the applied devices.

In Table 2, we provide an overview of our coding of the current body of ASR research. About three-quarters of the reviewed studies address AR technologies in e-commerce or m-commerce (e.g., Javornik, 2016b; Baek et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2021). Only seven studies focus on the AR technology’s application in brick-and-mortar retailing (e.g., Joerß et al., 2021; Yuan et al., 2021; Hoffmann et al., 2022). Six studies focus neither on e-/m-commerce nor on physical retailing. These studies, for instance, consider more generally the use of AR glasses (e.g., Rauschnabel, 2018; Rauschnabel et al., 2018) or tangible (vs. gesture-based) interactions with an AR system (e.g., Brito and Stoyanova, 2018).

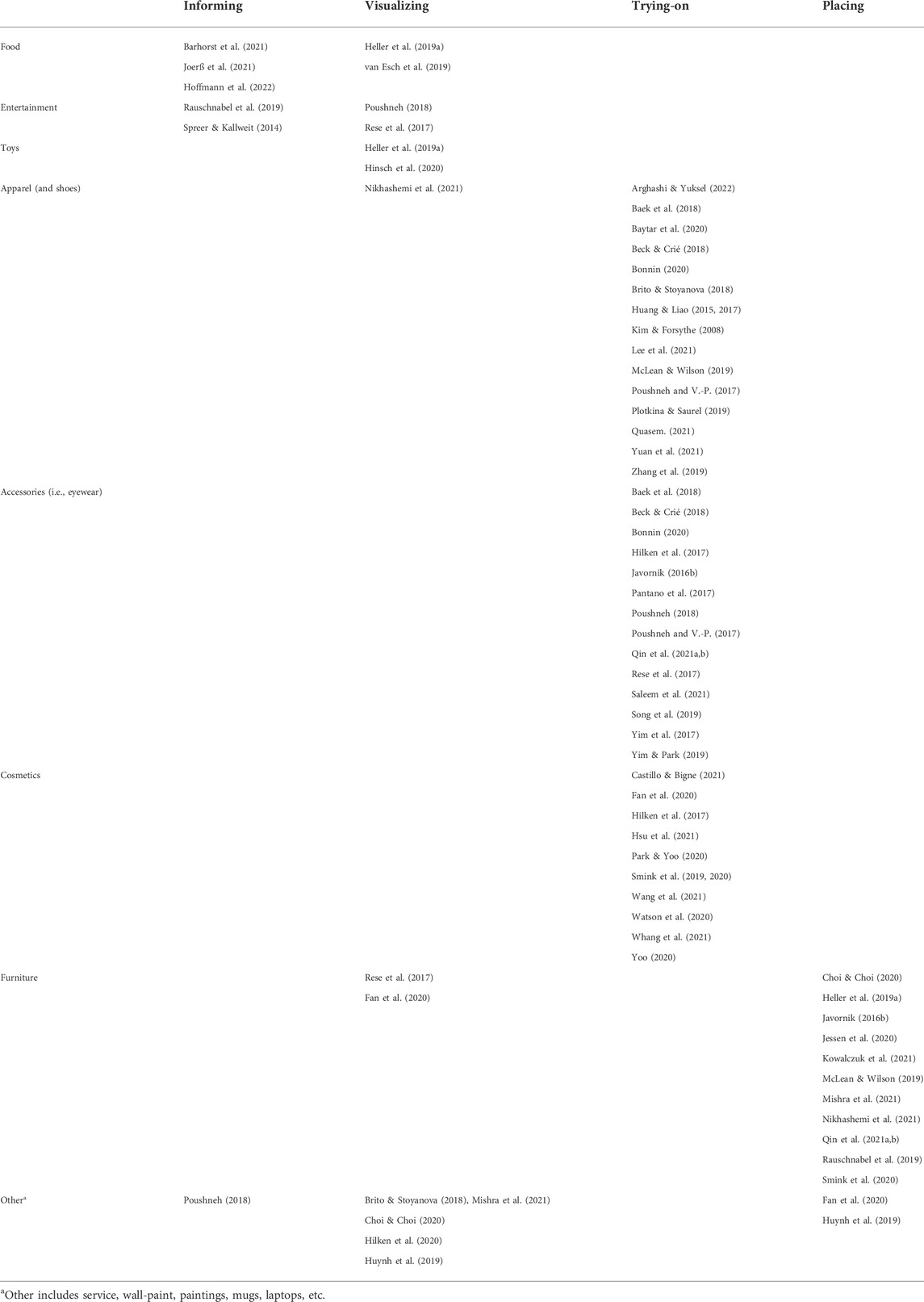

In Table 3, we detail the examined product categories and related AR functionalities, finding a systematic confound between the analyzed product category and the AR function. In particular, studies exploring the trying-on function often use existing virtual try-on-applications for apparel, accessories, or makeup. Likewise, several studies use existing furniture planners for virtually placing furniture in one’s own rooms at home.

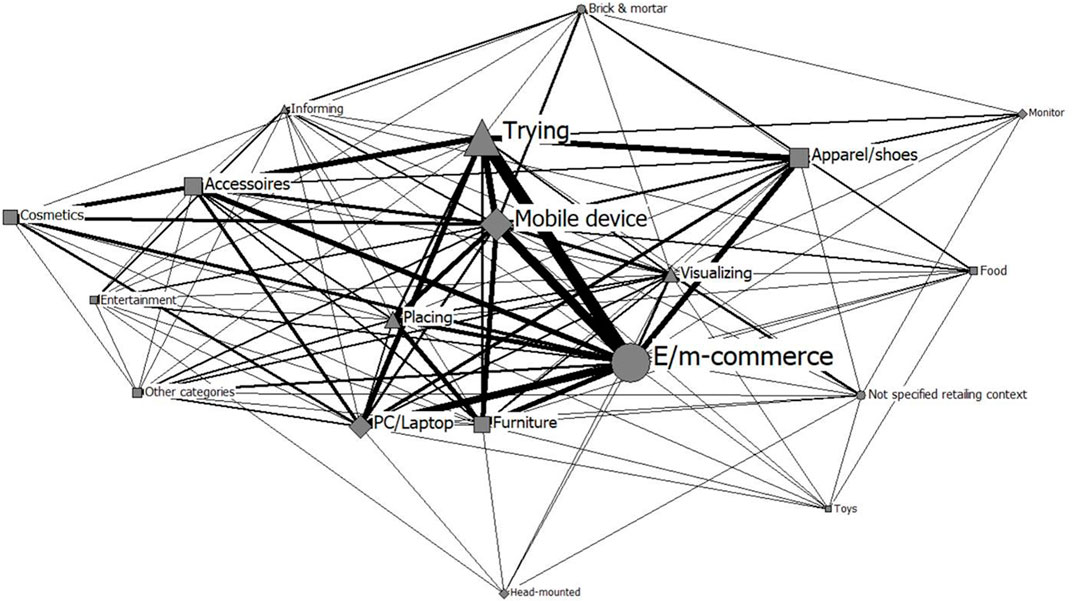

To visualize these results and illustrate how the various applications of AR in retailing are embedded in a broader network, we employed network analysis (Figure 1). Originally used to assess social networks (Hennig et al., 2012), this analytical technique recently became popular to conduct literature reviews (e.g., Hoffmann et al., 2020). This analysis visualizes contingencies, which enables us to identify gaps and it builds the foundation for developing our future research agenda. We converted our coding in Table 2 into a 19 × 19 matrix and used this as the starting point for the analysis. The diagonal of this matrix captures the total number of studies that explored this AR factor, while the non-diagonal elements reflect the frequency with which a pair of two factors was investigated in prior research. In the analysis, each AR factor is represented by a node, the size of which indicates the relative frequency with which this factor was studied in the literature. Occurrences of the factor with other AR-related factors in previous studies are illustrated by ties, the size of which indicates the frequency of their co-occurrence. Spatially close relationships in the resulting graphical network consequently indicate which AR factors were studied together in the current literature. More distant relationships concern factors that received less attention or were explored in isolation.

FIGURE 1. Network analysis of the AR-related factors studied in previous research. Notes. ● Type of retailing, ■ product category, ▲ AR function, ◆ device.

The complete graphical network is represented in Figure 1, showing that ASR is predominantly investigated in the e-commerce domain in order to try on (or test) products, both for mobile devices or traditional PC and laptops. Several strong ties with the trying-on function accordingly show that this AR function was primarily examined in the fashion industry, cosmetics, and accessories. Furniture is explored in regards to placing. A visual inspection further reveals that conveying information is an understudied functionality of AR. Likewise, the technology appears less central in traditional brick-and-mortar stores, such as enriching grocery purchases. Consequently, devices provided by the company—which may become increasingly relevant in physical shopping contexts like head-mounted displays—received much less attention than devices owned by the consumer. The frequency and diversity of the ties for computers and smartphones imply that research relying on these devices is already rich and heterogeneous but also hints at certain gaps in the literature that will be discussed in our research agenda in greater detail.

In sum, the visualization in Figure 1 depicts the contingencies among the product category, the AR functionality, the retailing channel, and the AR device. These contingencies plague the current body of empirical AR literature and thus reflect the practical challenges when conducting AR research in the past. Still, it is important to mention that different combinations are feasible that may provide so far untapped benefits. When the technological development and diffusion of AR devices (such as head-mounted displays) proceeds, novel applications will emerge and be the subject of research interest (e.g., shopping goods offered in brick-and-mortar stores can be virtually placed in the consumers’ house via head-mounted displays).

Theories

The current AR research relies on a rich fundament of well-established theories. Most of our analyzed studies draw on a sound theoretical basis. These papers’ research objectives largely determined the applied theoretical basis. As a general framework, some of them use the S-O-R model (Mehrabian and Russel, 1974). A large number of papers builds on the technology acceptance model (Davis. 1989) or its extensions (e.g., UTUAT) to explain the adoption of the AR technology. Others apply the information systems success model (DeLone and McLean, 1992). Research on the drivers of AR adoption and purchase intentions frequently adopts motivational theories, such as flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997), the theory of interactive media effects (Sundar et al., 2015), uses and gratification theory (Ruggiero, 2000), regulatory mode theory (Higgins et al., 2003), or self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci, 2000). Some AR studies specifically focus on the fact that consumers can observe themselves wearing products with the help of the technology. These studies rely on self-referencing (Rogers et al., 1977) and virtual liminoid (Jung and Pawlowski, 2014). Further articles consider whether and how consumers are able to imagine products or their placement better when supported by an AR tool. These papers build on mental imagery (Schifferstein, 2009) and situated cognition (Robbins and Aydede, 2009). For example, the situated cognition perspective posits that consumers more deeply process and remember information when this information is embedded in their environment (e.g., virtually placing furniture in their own living room) and when consumers interact with the information (e.g., actively controlling the angle of the 3D visualization; Hilken et al., 2017, 2018). Finally, some studies take into account the risks and barriers of AR adoption, building on equity theory (Adams, 1963) or the privacy calculus theory (Culnan and Armstrong, 1999).

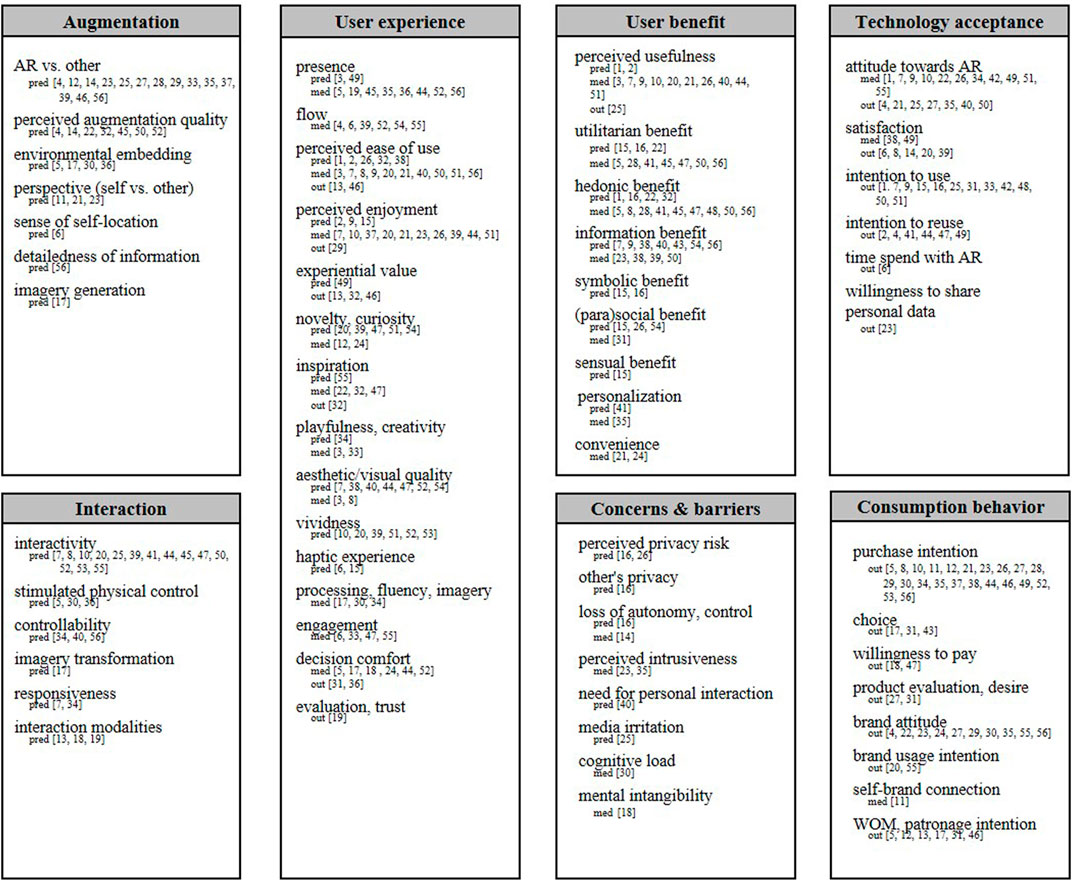

Consumer models

Past ASR research has been guided by different objectives, such as predicting customer experience, understanding technology adoption, or improving downstream marketing outcomes. Accordingly, the consumer models used so far are cluttered. In this section, we restructure the body of empirical literature systematically to depict the overlaps of the involved variables across the AR studies conducted in the different contexts. On this basis, we will then integrate these partial models.

First, we give an overview of the independent, mediating, moderating, and dependent variables in the consumer behavior models in ASR. The scopes of the different studies vary substantially. For example, while some papers seek to explain purchase intentions as the primary outcome (e.g., Baek et al., 2018; Fan et al., 2020), others focus on the perceived ease of use as the outcome variable (e.g., Mishra et al., 2021). Notably, some studies conceptualize ease of use as a predictor (e.g., Zhang et al., 2019), whereas others specify this as a mediator (e.g., Plotkina and Saurel, 2019) that translates into purchase intentions as the dependent variable. We will now discuss the function of different variables from the perspective of the individual studies (Are they predictors, mediators, moderators, or outcomes?) before we start reorganizing the variables into an integrative framework.

The predictor variables in the consumer models refer to the factors augmentation, interaction, user experience, user benefit, and concerns/barriers. In terms of augmentation, many studies compare an experimental treatment involving AR to a control group without AR, such as a traditional website of the same brand. Several studies measure the user’s perception of augmented quality as the predictor. In the interaction category, the variables interactivity and stimulated control are frequently analyzed. For user experience as a measured predictor variable, perceived ease of use, aesthetics or visual quality and perceived enjoyment are most often applied. User benefits are analyzed in terms of perceived usefulness, information quality as well as utilitarian and hedonic benefit. Perceived privacy risks are often conceptualized as concerns or barriers.

To explain the process and induced mechanisms when interacting with the AR technology, the extant studies specified mediator variables, which comprise the categories user experience, user benefit, concerns/barriers, and consumption behavior. In the user experience category, many studies capture perceived ease of use, perceived enjoyment and the feeling of spatial presence or telepresence as mediating variables. As user benefit, prior research modelled the perceived usefulness as well as the utilitarian and hedonic benefits. By contrast, perceived intrusiveness is a relevant concern or barrier that explains some users’ reluctance to adopt AR. The literature also suggests mediators that are not specific to the AR technology. This concerns consumption behavior, including brand-related variables like self-brand-connection or brand engagement.

The outcome variables of the consumer models include various aspects of user experience, technology acceptance, and consumption behavior. For user experience, relevant outcomes involve shopping enjoyment or a positive experience. The most widely analyzed variables of technology acceptance are attitude towards the AR and the intention to use it. With regard to consumption behavior, most researchers apply a measurement of purchase intention. Other relevant outcome variables in this category concern brand attitude and word-of-mouth.

Some studies also include moderating variables and boundary conditions that help understand when AR is effective and when not. Moderating variables include aspects of the product, such as product type (Poushneh, 2018; Rauschnabel et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2020; Mishra et al., 2021), product contextuality (Heller et al., 2019a), consumer’s brand attachment (Yuan et al., 2021), and price-value trade-off (Heller et al., 2019a). Other moderators relate to the national background (Pantano et al., 2017) or sociodemographics (Zhang et al., 2019). Some studies rely on consumer-centred moderators, including technology anxiety (Kim and Forsythe 2008), technology-as-solution-belief (Joerß et al., 2021), involvement (Kim and Forsythe 2008), AR familiarity/experience (Yim et al., 2017; Song et al., 2019; Bonnin, 2020), processing fluency (Hilken et al., 2017; Heller et al., 2019a), or assessment orientation (Heller et al., 2019b; Jessen et al., 2020) as moderators.

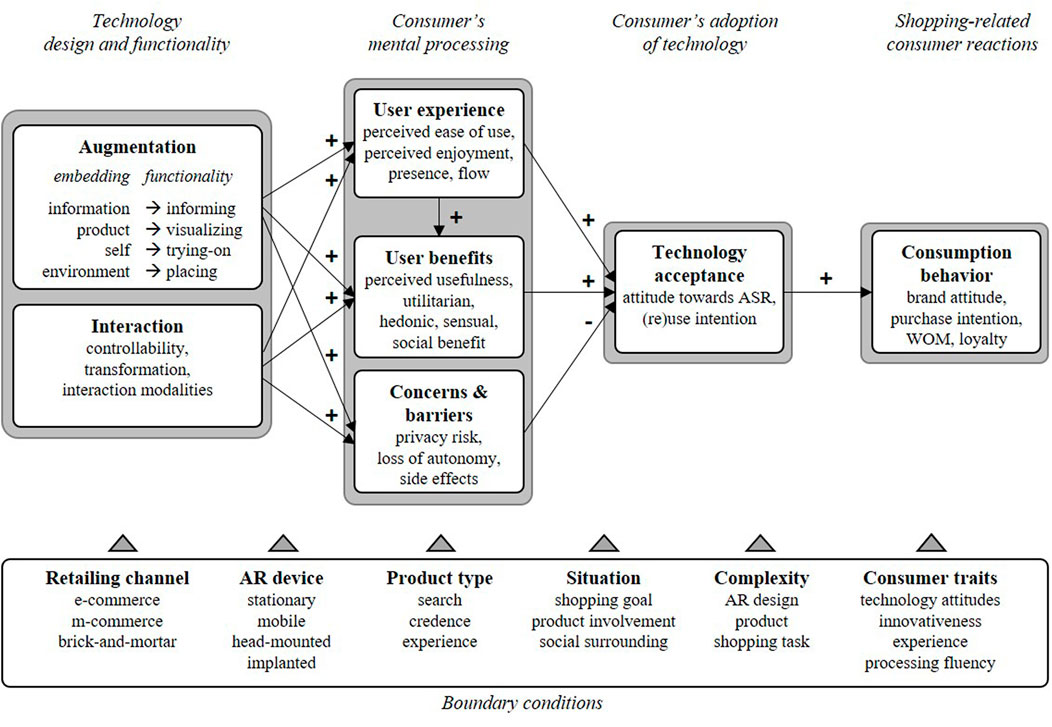

We have reorganized the variables in Figure 2 according to their theoretical function in the models (e.g., explaining user experience, technology acceptance, marketing outcomes, etc.). We also indicate whether these variables were initially featured as predictors, mediators, outcomes, or moderators. This re-organization of the variables builds the basis for our theory development towards an integrative consumer-processing model of the AR technology in shopping contexts.

FIGURE 2. Conceptually-structured overview of the researched variables. Notes. Superscripted numbers indicate the study number (see Table 2). Pred = variable used as a predictor variable in the cited study; med = variable used as a mediator in the cited study; out = variable used as an outcome variable in the cited study.

Method

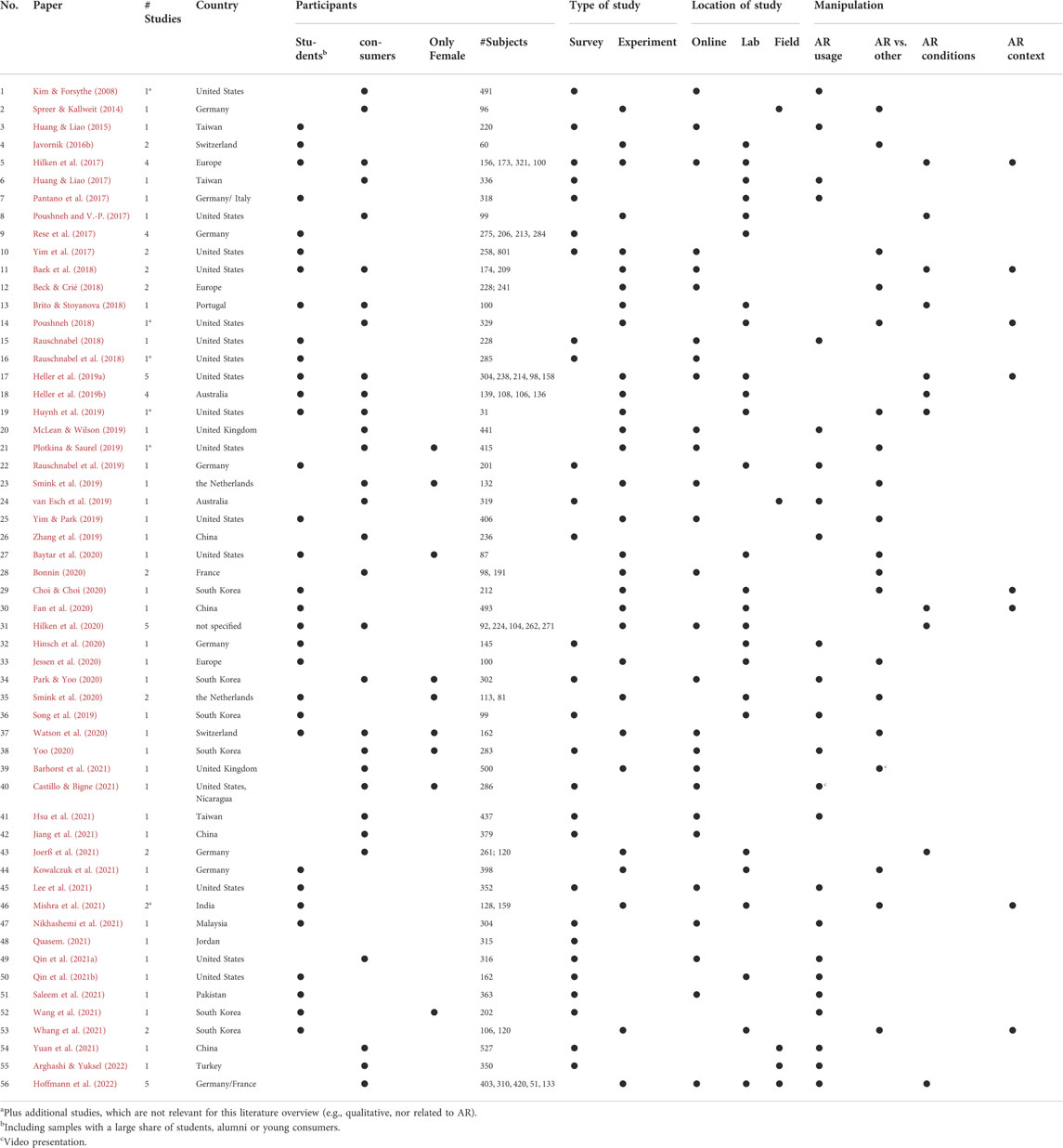

An overview of the methods applied in AR research is presented in Table 4. The 56 reviewed papers report 85 quantitative studies in total. As shown in Table 4, 31 papers report surveys and thus correlational data, while 30 papers report experiments. Note that two papers include both survey and experimental research. No clear dominance emerged for the mode of data collection, which happened both online (26 papers) and in the lab (25). Five papers even report evidence from field studies.

Researchers took different approaches to manipulate AR usage (Table 4). In the most straightforward approach (23 papers), the participants were asked to use an AR system before completing a survey (e.g., Huang and Liao, 2015, Huang and Liao, 2017; McLean and Wilson, 2019; van Esch et al., 2019; Park and Yoo, 2020). Typically, the participants were directed to an existing AR application and asked to download it on their smartphones. This is important to mention because these studies did not include a systematic experimental manipulation with different treatments and/or a control group. Hence, the evidence is of a correlational nature, which needs to be taken into consideration when drawing conclusions.

The second cluster of papers compared the AR system to another system, such as a website with AR and the same website without this technology (e.g., Javornik, 2016b; Yim et al., 2017; Beck and Crié, 2018; Bonnin, 2020; Watson et al., 2020). In their make-up study, Smink et al. (2019) compared the AR with pictures of the participants and pictures of a model. In a within-subject experiment, Baytar et al. (2020) compared physical try-on and then virtual try-on of apparel. Again, most of these studies made use of existing AR tools as the experimental treatment. It is important to distinguish this cluster of papers from the previous one because a systematic and standardized manipulation was, often, possible because several companies host a website where the AR condition can be switched on or off (virtual try-ons; e.g., Poushneh, 2018; Javornik, 2016b; Smink et al., 2019). Interestingly, some of these studies find that AR is superior, while others report the opposite (Plotkina and Saurel, 2019), which hints that AR effects are complex and contingent on several factors. For this reason, we will discuss the potential moderator variables later when we develop an integrative framework.

While the papers in the second cluster primarily focus on AR’s overall effectiveness compared to other communication modes, those of the third cluster zoomed in on the AR technology. These papers experimentally manipulated theoretically relevant aspects of the technology, such as the degree of interactivity (Poushneh and Vasquez-Parraga, 2017) and controllability (Hoffmann et al., 2022), markerless vs. marker-based interaction (Brito & Stoyanova, 2018), or the sensory control mode (Heller et al., 2019a).

Finally, some researchers ran multi-factorial experiments that manipulated various factors of the AR or one AR factor and a context factor. For example, Hilken et al. (2017) manipulated the stimulated physical control (low/high) and the environmental embedding (low/high). Baek et al. (2018) crossed the AR perspective (self-vs. other-viewing) and two levels of narcissism (high vs. low). Heller et al. (2019b) crossed imagery transformation (low/high) and embedding (low/high) as well as product contextuality (no/yes). Hoffmann et al. (2022) manipulated the AR controllability (low/high) and the AR information detailedness (low/high).

Theory development

Need and rationale of the integrative framework

Footing on the findings of our review, we now contribute to theory development for AR in retailing settings. Our review pinpoints that previous AR research relies on a solid fundament of well-established theories in the information systems domain, innovation management, and marketing (e.g., technology acceptance model). The field also borrows from related disciplines, such as communication science, social psychology, and cognitive psychology (e.g., uses and gratification theory, flow theory, situated cognition). This breadth and depth of the theoretical grounding attest to the different lenses through which the AR technology is already explored. However, our literature review revealed that the applied theoretical foundations are fragmented and often not AR-specific. This emphasizes the need to synthesize the fragmented theoretical basis and develop an AR-specific theoretical basis. Relatedly, ASR research should extend beyond studying the adaption-based factors and the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which is very useful to assess the usability and adoption of the technology but is also not specific to the two core constitutional properties of the AR technology, namely, augmentation and interactivity.

As another consequence of the specific foci, the literature review has revealed that scholars from the various fields adapt different theories with different constructs to explain AR effects. Psychological research is interested in the flow experience during AR usage, while innovation and technology management scholars often study technology acceptance as a relevant evaluation criterion and thus dependent variable. Notably, other disciplines are interested in the more downstream outcomes. Marketing and retailing scholars, for example, would conceptualize these variables as mediators that serve to explain the marketing-relevant variables, such as purchase behavior, loyalty, or word-of-mouth.

Against this background, we suggest an integrative framework. Inspired by similar attempts to integrate partial theories in other fields, such as wearable technologies (e.g., Kalantari 2017; Chuah, 2019), our theory development rests on a synopsis and refinement of extant work. We integrate conceptual works (Heller et al., 2019b; Caboni and Hagberg, 2019), qualitative research (Olsson et al., 2013; Scholz and Duffy, 2018; Romano et al., 2021), literature overviews (Bonnetti et al., 2018; Lavoye et al., 2021), and the relevant theoretical foundations. We substantiate this with our summary of empirical findings (Figure 2). We identify the most relevant aspects and integrate them into a new theoretical framework that serves as a guideline for AR research and practice in shopping contexts.

Based on our literature review, we detect several unresolved issues relevant to our theory development. The fragmentation of extant approaches stresses the need to integrate the partial theories and account for contextual aspects. While previous papers have either considered AR in e-commerce (e.g., Javornik, 2016b) or brick-and-mortar retailing (e.g., Joerß et al., 2021), our integrative model integrates findings from both perspectives and includes several moderator variables to account for boundary conditions. Second, as a major theoretical contribution, we distinguish between different features of AR in retailing settings, including informing, visualizing, trying-on, and placing. We detail the contingencies between these AR functionalities and other relevant variables, such as the shopping context, devices, product types, and customer benefit.

Given this holistic inclusion of different variable types, scholars can flexibly apply the framework to different settings. It is noteworthy that not every variable is relevant in every setting. Thus, the framework can be simplified and adapted to the specific context.

Suggestion of an integrative framework

Figure 3 presents the proposed integrative framework. The process-oriented model starts with the technology design. The next steps involve the consumer’s mental processing and adoption of the technology. This paper focuses on ASR, so the outcome variables involve shopping-related consumer reactions and moderators to understand the boundary conditions of the AR technology and its effects.

For the technology design, we follow previous conceptualizations and distinguish the two key properties of AR: augmentation and interaction (e.g., Azuma, 1997; Azuma et al., 2001; Javornik, 2016a). Augmentation concerns the question of which features are augmented and how they are embedded. Hence, we refer to literature that has focussed on the embedding of elements in AR (e.g., Hilken et al., 2017). Our model extends these approaches by including all the relevant aspects that can be augmented in shopping settings, including the information, the product, the self, or the environment. This distinction maps onto the ASR functions informing, visualizing, trying-on, and placing. Interaction refers to consumers’ ability to control the virtual elements, such as choosing additional information, transforming visual 2D or 3D elements, etc. This also includes the modalities of the interaction, such as touching, voice-based, or gesture-based.

In terms of consumer’s mental processing, three aspects should be distinguished: user experience, user benefits, and concerns/barriers. While positive user experience and perceived user benefits positively influence downstream variables, the concerns and barriers will hinder technology adoption, negatively impacting marketing outcomes. Core aspects of the user experience involve perceived enjoyment, spatial/telepresence, flow experience, and perceived ease of use. According to the technology acceptance model, user’s experience will also improve perceptions of user benefits (e.g., Huang and Liao, 2015; Pantano et al., 2017; Rese et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019). The user benefits of AR have initially been described as rather hedonic. However, with a more widespread use of AR as a serious tool that helps consumers make consumption decisions in today’s shopping environments, perceived usefulness and utilitarian aspects will become more relevant. This concerns information delivery, decision support or being a recommendation agent that simplifies consumers’ decisions. Further aspects include sensual and social benefits. Finally, as concerns and barriers to adopting the technology, the perceptions of privacy risks are relevant. Various sensors are active during the AR use (cameras, microphones, GPS information, tracking of the human/device interaction), so consumers’ privacy concerns are a critically relevant topic. Furthermore, there might be a perceived loss of autonomy or a sense of being manipulated, apart from feared side effects (e.g., the impact on the user’s physical or mental health or the implications for other consumers).

As downstream variables, the model includes the most relevant constructs from a marketing perspective, namely 1) whether consumers accept and adopt the technology and 2) whether using the technology alters marketing outcomes (e.g., purchasing). The technology acceptance includes, in particular, consumers’ attitudes towards ASR as well as the (re)use intention. The marketing outcomes include brand attitudes, purchase intentions, word-of-mouth, and loyalty.

Notably, the sequence of the model is not necessarily unidirectional. The user experience evaluation requires consumers first to try the technology (or at least observe others trying it), so user experience can also be conceptualized as a downstream variable in some cases. To avoid disproportionately inflating the framework’s complexity, we focus on the substantive perspective of retailing managers and a long-term perspective. From this perspective, the most relevant direction of the impact operates from the user experience via rational benefits/cost calculation to the technology attitude and ultimately the intention to (re)use the technology. This sequence matches the conceptual models of the previous studies that have already combined user experiences and/or user benefits with (re)use intentions (e.g., Pantano et al., 2017; Rese et al., 2017; Yim et al., 2017; Plotkina and Saurel, 2019; Smink et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019; Bonnin, 2020; Park and Yoo, 2020; Watson et al., 2020; Qin et al., 2021b; Lee et al., 2021).

The model also integrates six relevant categories of moderators and boundary conditions. These moderators have not yet been systematically tested, but they appear to be relevant based on our integration of past empirical works enriched with previous conceptual considerations (Flavián et al., 2019) and qualitative studies (Olsson et al., 2013; Scholz and Duffy, 2018; Romano et al., 2021). First, the retailing channel is an important boundary condition of consumers’ processing of the ASR (Hilken et al., 2018; Caboni and Hagberg, 2019). Our review revealed that the ASR functionality is contingent on the retailing channel. In e- and m-commerce, visualizing and virtual try-ons are important functions. In brick-and-mortar retailing, the ability to provide more product information seems more relevant. Second, how consumers process the ASR will further depend on aspects of the technology, such as the AR device that overlays the physical world with virtual information. Consumers may react differently depending on whether the information is displayed on a stationary monitor (e.g., “magic mirror”), handheld-mobile device, wearable and head-mounted devices, or even implanted lenses (Flavián et al., 2019). Third, the user benefit and usefulness of the ASR functionality (informing, visualizing, trying-on, placing) are contingent on the product type. Products with search, credence, and experience qualities require different treatments (Girard and Dion, 2010). Fourth, the shopping situation is important too (Olsson et al., 2013). Relevant aspects are the shopping goal, product involvement, and the social surrounding (private or public shopping in e-commerce or brick-and-mortar retailing). Fifth, complexity is an interesting moderator as past research has shown that, in digital contexts, consumers prefer medium degrees of complexity (Geissler et al., 2001; Mai et al., 2014) because fewer complexity evokes boredom, while higher levels evoke the feeling of being overwhelmed. Complexity may hence evoke a curvilinear moderating effect on several variables included in our processing model, such as the perceived ease of use, perceived enjoyment, loss of autonomy, presence, and flow. Scholars and ASR designers need to find the optimal degree of complexity for the AR design, product, and shopping task. Finally, the AR effects depend on consumer traits, such as technology attitudes, innovativeness, AR experience, and processing fluency.

Research agenda

ASR researchers can take the suggested framework (Figure 3) as orientation when developing new study designs. Based on our review and the synthesis of the analyzed literature, we propose directions for future research. Moreover, our literature review points to notable methodological limitations and gaps in the research landscape that need to be addressed.

Ten recommendations for future ASR research

First, most empirical studies in our literature review were conducted in e-commerce and m-commerce settings where websites were enriched by AR (e.g., Beck and Crié, 2018; Yim and Park, 2019). Only few papers consider ASR in brick-and-mortar stores (e.g., van Esch et al., 2019; Joerß et al., 2021; Hoffmann et al., 2022). This limited focus on digital environments may stem from the wide use of AR in these environments and, thus, the ease of studying them. Still, a rapidly growing number of AR apps exist for physical environments and deserve much greater attention. Our review has shown that the application and effectiveness of AR in shopping environments are highly contextualized and depend on the specific AR functions, devices, product types, and so forth. So far, researchers have adopted theories fitting the particular context in which they conduct their AR studies. Most retailing studies focus on the hedonic benefits of the try-on function, while the benefits of placing and visualizing are less explored. Arguably, the AR function ‘informing’ is more relevant for utilitarian benefits (Hoffmann et al., 2021). However, AR-specific theories for information processing have not yet been applied, so more research is needed to fill this void. Ideally, studies should explicitly model the retailing channel as a moderating variable. In e-commerce, for example, the virtual try-on function is greatly valued for certain products (e.g., apparel, accessories, or cosmetics) and can create hedonic benefits for shoppers. Still, theories that explain consumer reactions in these contexts (e.g., via flow experience) cannot necessarily explain consumer reactions to AR-delivered information functions through mobile applications for groceries in brick-and-mortar settings (e.g., Joerß et al., 2021). Here, utilitarian benefits (e.g., transparent and trustworthy information) may be more important in the consumer’s decision-making compared to hedonic benefits and flow experiences.

Second, and related to the previous direction for future research, the AR practice and research in shopping contexts has not yet made full use of AR’s vast range of functionalities. We outlined that the four functionalities informing, visualizing, trying-on, and placing are most relevant for shopping contexts. So far, we see that informing is mainly used for food products in brick-and-mortar contexts, while trying-on and placing are more frequently used in studies on e-commerce. Trying-on is applied for product categories, such as cosmetics, apparel, or glasses, whereas placing is used for furniture or wall paint. Evidently, the AR functions are more flexible, so scholars and practitioners should consider different configurations of AR functionalities in combination with certain product categories and retailing channels.

Third, more research on the role of the AR-enabling device is needed. Mobile devices, like tablets and smartphones, are already widespread and common in use. While the current theoretical approaches apply to these devices, other devices like head-mounted displays, AR glasses, or even AR lenses are still unusual in real-life, everyday applications. Nonetheless, the diffusion of such devices may intensify, and managers need to know how consumers respond to such devices and whether they use them to facilitate their judgments and shopping decisions in online and offline contexts. In addition, nuanced explanations are needed given the differences across devices, including the control function (e.g., haptic or voice), the need to use hands (smartphones vs. glasses), or the ability to move around (PC vs. helmet). For instance, location-based AR-effects (shopping guide in the supermarket, mall) should be embedded in future ASR-specific theories.

Fourth and related to the previous aspect, augmented information can be conveyed through different modalities that address different senses, including visual formats (e.g., images, labels), audio formats (e.g., music, voice), audio-visual formats (videos), and 2D or 3D visualizations (e.g., Azuma, 1997; Javornik, 2016a; Brito and Stoyanova, 2018). Marketing research has mainly considered visual augmentations but largely neglected other modalities. Exceptions are Brito and Stoyanova (2018) testing markerless or gesture-based interactions, Huang and Liao (2017) considering haptic imagery, and Heller et al. (2019b) comparing touch control vs. voice control (Heller et al., 2019b). More research spanning a more comprehensive array of presentation modes and interaction forms is necessary to prepare the application of advanced technologies in the future.

Fifth, ASR research should also take into account systematic differences among product types, for example, by distinguishing search, experience, and credence goods. For some goods, hedonic experiences through AR usage might entertain consumers (e.g., entertainment products, cosmetics), but information and more utilitarian aspects should be relevant in other consumer decisions or purchases. This distinction is relevant because experiential and materialistic purchases are motivated in distinct ways (Gilovich et al., 2015), so the various AR-functionalities should be differentially relevant too. Further theory development should also include value theories that distinguish, for example, functional, hedonic/experiential or social values that are enjoyed while using AR (Hilken et al., 2020). Deeper theoretical considerations of the consumers’ decision modes (extensive, limited, habitual, impulsive) may further help understand how beneficial consumers experience the AR support to be. Future advances may also need to be able to explain ASR effects at different stages of the customer journey (e.g., Jessen et al., 2020). Findings of stage-specific effects in other domains (Mai et al., 2021) imply that the AR-functionalities may be differently relevant across the various consumption stages. For example, while the hedonic experience may motivate users to use the AR technology in the first place, the more utilitarian benefits that materialize with each purchase may become the driving force to encourage continued use of the technology in shopping environments. Future ASR research may therefore require multi-stage theories.

Sixth, more contextual and situational factors should be taken into account too. Consumers’ mood, time pressure, or the presence of other consumers may determine whether (or not) consumers are willing to make use of AR. Plausibly, consumers rely on the AR technology when they have time for their shopping but abandon it when being under pressure or in more stressful shopping environments (Hoffmann et al., 2022). Such knowledge would be important because the technology should unfold its benefit of being a tool or a recommendation agent, especially under such suboptimal conditions. Additionally, when used with mobile devices (smartphones or tablets), the AR technology can also integrate location-based information (Reitmayr and Drummond, 2006). This is already implemented in tourism apps and may likewise be beneficial in other marketing applications. Furthermore, contextual information might be available from other modalities, such as haptic and olfactory information. Future studies should consider such cross-modal effects.

Seventh, our synopsis of past research in the framework model shows that research explaining the (re)use intention of ASR has quite matured, and there are also indications of positive influences on some downstream variables once consumers start using ASR. However, a lack of research persists on how ASR usage translates into marketing outcomes, such as brand image, (re)purchase intention, or word of mouth. We call for more research on the mediating variables and the specific boundary conditions. For example, the ethnographic study by Scholz and Duffy (2018) reveals that ASR can create a more intimate brand-customer relationship. Future research may build on this finding to delve deeper into how ASR can shape brand image, customer-brand relationship, and brand equity. The qualitative research of Romano et al. (2021) has demonstrated that ASR affects users’ consideration and their choice set. Accordingly, more insights into the decision process are needed.

Eighth, since ASR is a relatively young domain, the longitudinal perspective is still missing but very promising. Future research could start, for example, by investigating the adaptation and learning processes of AR users. Although several purported benefits of the technology are supported by empirical evidence, the question remains to be answered as to whether consumers integrate the technology into their daily shopping routines (and if so, how they do this). For example, do consumers consider ASR only as a toy that creates entertaining and hedonic benefits at the moment but which can wear out quickly? Or will ASR—with greater diffusion and familiarity—become a tool that consumers use for information and utilitarian needs on a regular basis? Scholars should therefore study habituation and even potential wear-out effects. Another interesting development, which may become more widespread once the technology has further evolved, is the extension or even substitution of physical products by virtual products as discussed by Rauschnabel (2021) and Dwivedi et al. (2021).

Ninth, it is principally possible to contextualize, customize, and personalize the AR information for increasing convenience and consumer benefit (e.g., Huynh et al., 2019; Hsu et al., 2021; Nikhashemi et al., 2021). However, data privacy and security are crucial topics that deserve attention (Hilken et al., 2017; Inman and Nikolova, 2017; Rauschnabel et al., 2018; Smink et al., 2019). Future AR research should explore the perceived intrusiveness, loss of autonomy, the willingness to share personal data (i.e., regarding facial recognition or location-based information for personalization), and whether consumers are willing to use ASR apps on their personal smartphones or other devices. Some studies have already relied on equity theory (Adams 1963) to understand how customers balance augmentation quality and the privacy of personal information (Poushneh 2018), but more insights are needed to manage this issue better.

Tenth, research on ASR will be an ongoing process as the technology evolves rapidly. Similarly, organizational and legal conditions will change. Marketing and retailing literature should monitor, for example, which devices are the prime candidates for ASR in future business environments. Also, more experimental technological solutions should be explored, such as lenses or implants, and how consumers will respond to these developments. Likewise, insights are needed into how AI, big data, and machine learning alter the information provided via ASR. Especially concerning consumer trust, knowledge is sparse about who should provide the ASR information (producer, retailer, NGOs, other consumers).

Limitations and methodological aspects

First, a vast majority of the current ASR research explores the effectiveness of the technology (contrasting AR to other technologies) and zooms in on specific properties. However, no study has tackled the factors leading to actual purchase behavior. Therefore, future research should shift the focus more strongly on real purchases (consumer perspective) and actual sales (company perspective, e.g., Tan et al., 2021), both in e-commerce and brick-and-mortar stores. Obtaining purchase data in the field will help corroborate the ecological validity of previous findings and provide a more precise estimate of the AR technology’s impact in real shopping environments.

Second, the research designs in the AR literature have certain limitations regarding the sampling. Many studies employ nonsystematic sampling procedures, such as convenience sampling or snowballing, for recruiting participants. Several studies also take advantage of university participation pools. This may be explained by the fact that current designs emphasize internal validity, but external validity should be taken into focus too. As a result of previous sampling procedures, our state of the knowledge is often based on studies with students and younger consumers who are often technology-affine and open to digital solutions. However, older individuals are also very relevant in digital and physical environments. In a similar vein, education levels are typically higher for student samples. A gender bias might also arise and distort our conclusions about ASR. Due to the focus on virtual try-on for apparel and cosmetics, nine of the 56 studies (16%) include female participants only and some other studies include substantially more female than male participants. Considering these specifics and the lack of representativeness, AR research should be complemented by studies in the field that put greater emphasis on external and ecological validity.

Third, this literature review shows that the number of quantitative empirical studies analyzing consumer behavior in ASR is steadily growing. Meta-analyses could provide a valuable approach to integrate findings and estimate general effects and moderations. Yet, quantitative meta-analyses require a small set of pre-defined predictors and outcome variables. Our review reveals that prior studies included about 40 different predictor variables and about 30 different outcome variables (plus about 40 mediating variables). This variety reflects that ASR researchers tried to explain different outcomes (e.g., user experience, technology acceptance, shopping and patronage behavior), and they used very diverse theories to explain these outcomes (e.g., TAM, flow, Uses and Gratifications etc.). Our approach of structuring the literature and integrating different models into a more comprehensive model hopefully sets the stage for future meta-analyses.

Conclusion

Reviewing and synthesizing a comprehensive set of empirical papers on ASR reveals a growing interest in this technology in both research and practice. Prior research efforts have been devoted to consumers’ experience with AR, acceptance of AR, and behavioral reactions to AR in various online and offline retailing settings. However, our literature review also revealed that large differences exist in the studied AR devices, the AR functionalities, and the addressed consumer reactions. It is therefore not surprising that the literature is highly fragmented. The integrated framework developed in this paper can help researchers to approach ASR and its effects holistically as well as to explore the relevant moderators that cause different effects in different situations. However, more research is needed on these moderators, in particular, and the effects of context (e.g., with regard to the devices, addressed senses, retailing channels, shopping goals, product categories, etc.). From a methodological point of view, more laboratory and field experiments are needed to learn more about the causal effects of different ASR designs. The present literature review and the outlined research directions will hopefully guide scholars and provide knowledge to optimize future ASR, being beneficial for both retailers and customers.

Summary statement of contribution

The growing literature on consumer behavior in augmented shopping reality (ASR) is highly fragmented as scholars focus on different retailing settings, products categories, AR functions, and AR devices, using different methods. Our systematic literature review synthesizes the knowledge and critically discusses the empirical studies, both conceptually and methodologically. In addition, the paper develops an integrative framework model, which helps derive directives for future research on consumer behavior in ASR.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are cited in the text and reference list, further inquires can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SH and RM contributed to conception and design of the study. SH conducted the literature research and review and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SH and RM contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) within the funding programme Open Access-Publikationskosten.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, J. S. (1963). Towards an understanding of inequity. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 67 (5), 422–436. doi:10.1037/h0040968

Aluri, A. (2017). Mobile augmented reality (MAR) game as a travel guide: Insights from pokémon GO. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 8 (1), 55–72. doi:10.1108/jhtt-12-2016-0087

Arghashi, V., and Yuksel, C. A. (2022). Interactivity, inspiration, and perceived usefulness! How retailers’ AR-apps improve consumer engagement through flow. J. Retail. Consumer Serv. 64, 102756. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102756

Azuma, R. T. (1997). A survey of augmented reality. Presence. (Camb). 6 (4), 355–385. doi:10.1162/pres.1997.6.4.355

Azuma, R. T., Baillot, Y., Behringer, R., Feiner, S., Julier, S., and MacIntyre, B. (2001). Recent advances in augmented reality. Washington, DC: Naval Research Lab.

Baek, T. H., Yoo, C. Y., and Yoon, S. (2018). Augment yourself through virtual mirror: The impact of self-viewing and narcissism on consumer responses. Int. J. Advert. 37 (3), 421–439. doi:10.1080/02650487.2016.1244887

Barhorst, J. B., McLean, G., Shah, E., and Mack, R. (2021). Blending the real world and the virtual world: Exploring the role of flow in augmented reality experiences. J. Bus. Res. 122, 423–436. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.041

Baytar, F., Chung, T., and Shin, E. (2020). Evaluating garments in augmented reality when shopping online. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 24 (4), 667–683. doi:10.1108/jfmm-05-2018-0077

Beck, M., and Crié, D. (2018). I virtually try it … I want it ! Virtual fitting room: A tool to increase on-line and off-line exploratory behavior, patronage and purchase intentions I want it! Virtual fitting room: A tool to increase online and offline exploratory behavior, patronage and purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consumer Serv. 40, 279–286. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.08.006

Berryman, D. R. (2012). Augmented reality: A review. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 31 (2), 212–218. doi:10.1080/02763869.2012.670604

Bonetti, F., Warnaby, G., and Quinn, L. (2018). “Augmented reality and virtual reality in physical and online retailing: A review, synthesis and research agenda,” in Augmented reality and virtual reality. Editors T. M. Jung, and C. tom Dieck (Springer), 119–132.

Bonnin, G. (2020). The roles of perceived risk, attractiveness of the online store and familiarity with AR in the influence of AR on patronage intention. J. Retail. Consumer Serv. 52, 101938. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101938

Botella, C. M., Lizandra, M. C. J., Baños, R. M., Raya, M. A., Guillén, V., and Rey, B. (2005). Mixing realities? An application of augmented reality for the treatment of cockroach phobia. Cyberpsychology Behav. 8 (2), 162–171. doi:10.1089/cpb.2005.8.162

Bower, M., Howe, C., McCredie, N., Robinson, A., and Grover, D. (2014). Augmented reality in education–cases, places and potentials. Educ. Media Int. 51 (1), 1–15. doi:10.1080/09523987.2014.889400

Boyd, D. E., and Koles, B. (2019). Virtual reality and its impact on B2B marketing: A value-in-use perspective. J. Bus. Res. 100, 590–598. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.06.007

Brito, P. Q., and Stoyanova, J. (2018). Marker versus markerless augmented reality. Which has more impact on users? Int. J. Human–Computer. Interact. 34, 819–833. doi:10.1080/10447318.2017.1393974

Caboni, F., and Hagberg, J. (2019). Augmented reality in retailing: A review of features, applications and value. Int. J. Retail Distribution Manag. 47 (11), 1125–1140. doi:10.1108/ijrdm-12-2018-0263

Carmigniani, J., Furht, B., Anisetti, M., Ceravolo, P., Damiani, E., and Ivkovic, M. (2011). Augmented reality technologies, systems and applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 51 (1), 341–377. doi:10.1007/s11042-010-0660-6

Castillo, S. M. J., and Bigne, E. (2021). A model of adoption of AR-based self-service technologies: A two country comparison. Int. J. Retail Distribution Manag. 49 (7), 875–898. doi:10.1108/ijrdm-09-2020-0380

Chae, H. J., Hwang, J. I., and Seo, J. (2018). “Wall-based space manipulation technique for efficient placement of distant objects in augmented reality,” in Proceedings of the 31st Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, 45–52.

Chen, P., Liu, X., Cheng, W., and Huang, R. (2017). A review of using Augmented Reality in education from 2011 to 2016. Innovations Smart Learn., 13–18.

Choi, U., and Choi, B. (2020). The effect of augmented reality on consumer learning for search and experience products in mobile commerce. Cyberpsychology, Behav. Soc. Netw. 23 (11), 800–805. doi:10.1089/cyber.2020.0057

Chuah, S. H. W. (2019). Wearable XR-technology: Literature review, conceptual framework and future research directions. Int. J. Technol. Mark. 13 (3-4), 1–259. doi:10.1504/ijtmkt.2019.10021794

Chung, N., Lee, H., Kim, J. Y., and Koo, C. (2018). The role of augmented reality for experience-influenced environments: The case of cultural heritage tourism in Korea. J. Travel Res. 57 (5), 627–643. doi:10.1177/0047287517708255

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Culnan, M. J., and Armstrong, P. K. (1999). Information privacy concerns, procedural fairness, and impersonal trust: An empirical investigation. Organ. Sci. 10 (1), 104–115. doi:10.1287/orsc.10.1.104

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 13 (3), 319–340. doi:10.2307/249008

de Ruyter, K., Heller, J., Hilken, T., Chylinski, M., Keeling, D. I., and Mahr, D. (2020). Seeing with the customer’s eye: Exploring the challenges and opportunities of AR advertising. J. Advert. 49 (2), 109–124. doi:10.1080/00913367.2020.1740123

Deliza, R., and MacFie, H. J. (1996). The generation of sensory expectation by external cues and its effect on sensory perception and hedonic ratings: A review. J. Sens. Stud. 11 (2), 103–128. doi:10.1111/j.1745-459x.1996.tb00036.x

DeLone, W. H., and McLean, E. R. (1992). Information systems success: The quest for the dependent variable. Inf. Syst. Res. 3 (1), 60–95. doi:10.1287/isre.3.1.60

Di Serio, A., Ibáñez, M. B., and Kloos, C. D. (2013). Impact of an augmented reality system on students’ motivation for a visual art course. Comput. Educ. 68, 586–596. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.03.002

Dwivedi, Y. K., Ismagilova, E., Hughes, D. L., Carlson, J., Filieri, R., Jacobson, J., et al. (2021). Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 59, 102168. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102168

Fan, X., Chai, Z., Deng, N., and Dong, X. (2020). Adoption of augmented reality in online retail-ing and consumers’ product attitude: A cognitive perspective. J. Retail. Consumer Serv. 53 (2), 101986. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101986

Flavián, C., Ibáñez-Sánchez, S., and Orús, C. (2019). The impact of virtual, augmented and mixed reality technologies on the customer experience. J. Bus. Res. 100, 547–560. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.050

Geissler, G., Zinkhan, G., and Watson, R. T. (2001). Web home page complexity and communi-cation effectiveness. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2 (2), 1–48. doi:10.17705/1jais.00014

Gilovich, T., Kumar, A., and Jampol, L. (2015). A wonderful life: Experiential consumption and the pursuit of happiness. J. Consum. Psychol. 25 (1), 152–165. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2014.08.004

Girard, T., and Dion, P. (2010). Validating the search, experience, and credence product classification framework. J. Bus. Res. 63 (9-10), 1079–1087. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.12.011

Hacker, J., vom Brocke, J., Handali, J., Otto, M., and Schneider, J. (2020). Virtually in this together–how web-conferencing systems enabled a new virtual togetherness during the COVID-19 crisis. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 29 (5), 563–584. doi:10.1080/0960085x.2020.1814680