94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Virtual Real., 28 September 2021

Sec. Virtual Reality and Human Behaviour

Volume 2 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frvir.2021.646930

This article is part of the Research TopicEditors Showcase: Embodiment in Virtual RealityView all 10 articles

Loup Vuarnesson1,2*†

Loup Vuarnesson1,2*† Dionysios Zamplaras1,3*†

Dionysios Zamplaras1,3*† Julien Laroche4,5

Julien Laroche4,5 Joseph Dumit6

Joseph Dumit6 Clint Lutes7

Clint Lutes7 Asaf Bachrach5,8‡

Asaf Bachrach5,8‡ Francois Garnier1‡

Francois Garnier1‡Shaping both the environment and the embodiment of the users in that virtual world, VR offers designers and cognitive scientists the unprecedented potential to virtually explore a vast set of interactions between persons, and persons and their environment. By design, VR tools offer a formidable opportunity to revisit the links between body movement and lived experiences, and to experiment with them in a controlled, yet engaging and ecologically valid manner. In our multidisciplinary research-creation project we ask, how can we design (virtual) environments that specifically encourage interactions between multiple persons and that allow designers, scientists, and participants (users or “immersants”) to explore the very process of interaction itself? Building on our combined experience with dance improvisation research and interactive virtual spatial design, we document a multi-user VR experience design approach we name Shared Diminished Reality (SDR), where immersants are co-present and able to move together while their bodies and the environment are represented in a minimalist way. Our working hypothesis is that non-anthropomorphic embodiment of oneself and one’s partner(s), combined with open-ended exploration, focuses the user’s attention on the quality of the interaction and encourages playfulness and creativity. We present the articulations VR platform and its design history, as well as design evaluations of SDR in a laboratory setting and through a mixed reality performance, interrogating the impact of our minimalist approach on user experience and on the quality of the interaction. Our results suggest that minimizing (self and other) representation in Shared Diminished Reality positively impacts relational dynamics, induces playful creativity, and fosters the will to move and improvise together.

The question of embodied interactions has emerged as a central theme in the cognitive sciences, robotics, and related fields, extending older philosophical preoccupations. Philosophers from Bergson (1939) and Merleau-Ponty (1945), to Noë (2012) and Manning (2009) have indeed insisted on the role of bodily actions in the construction of space and perception more generally. According to the enactive cognition stance, how we move in our environment and how we experience it as a world is a circular, co-constitutive process (Merleau-Ponty 1945; Varela et al., 1991). In other words, we realize the world by interacting with it, and by realizing the world, we realize ourselves: we are present (Manning, 2009; Noë, 2012).

The recent and growing development of virtual reality (VR) tools allows us to design new lived worlds: to construct and visit new spaces, to try new practices, and to interact with new contexts. Shaping both the environment and the embodiment of the users in that virtual world, VR offers designers and cognitive scientists the unprecedented potential to explore virtually a vast set of interactions between persons and their environment, new ways to be present to oneself, to the world, and to others.

By design, VR tools offer a formidable opportunity to revisit the very link between body movement and lived experiences and to experiment with it in a controlled, yet engaging and ecologically valid manner. In this context of application, the design of the environment is usually under focus, allowing researchers to experiment with how subjects interact with the features of the virtual environment. Yet, a more recent focus in cognitive sciences research and experience design in VR (Greenwald et al., 2017; Wienrich et al., 2018) concerns the interaction between persons, giving a central role to relationality itself (De Jaegher et al., 2010; Laroche et al., 2014). Indeed, when the couplings between perception and action of two or more persons become intertwined, the dynamics of bodily interactions give rise to the experience of being “co-present” (Froese et al., 2014a; Froese et al., 2014b). For Manning (2009), “relational movement” (the way we move in relation with other bodies/selves) underlies our own sense of self (“bodying”) and our being in the world (“worlding”). By interacting and moving together, we participate in each other’s experiences and sense-making (De Jaegher and Di Paolo, 2007). In other words, the way our lived experiences become meaningful, and our world imbued with sense emerges from our active bodily encounters with our environment, and especially with others (McGann and De Jaegher, 2009).

How can we design (virtual) environments that encourage interactions between multiple persons and that allow designers, scientists, and participants (users or “immersants”) to explore the very process of interaction itself? A number of members of the research project previously addressed the formal study of open-ended interpersonal interaction by designing GIGs, an acronym for (in person) Group Improvisation Games. This consists in bringing groups of participants to explore their reciprocal interactions and to do so freely within a simple set of constraints (Himberg et al., 2018). How can VR support and contribute to the improvement of the methodological set-ups employed in this kind of research? And, in turn, how can this line of research inform multi-person VR design? In this study, we propose to use the tools of VR to control and manipulate the coupling between perception and joint action and thereby evoke differential affective experiences. For this purpose, we propose a conceptual framework we name “shared diminished reality” (SDR). In this framework, inspired by the cross-perceptual paradigm (Auvray et al., 2009), immersants are co-present and able to move together, but their bodies and the environment are represented in a minimalist way. This allows the user to focus his/her attention on experiencing the interaction itself and allows the designers or scientists to track the core dynamics of the interactions between participants.

In order to present the SDR framework, we first review the potential of VR for the scientific and artistic research around movement and in particular relational movement, focusing specifically on what we consider minimalist designs. We will then turn to the interdisciplinary design and design-history of our shared VR platform (Articulations) which represents an attempt at instantiating SDR. In this study, Articulations serves as both a theoretical object through which to reflect on SDR and an empirical testing ground of its art-science potential. In the second part of the study, we report two forms of design evaluation, one as cognitive science research (the “laboratory installation”) and the other in the “practice as research” tradition (the “research-creation installation”).

The increase in computer graphic capacities and the rise of immersive technologies in recent years have brought about the conception of new tools for the in-depth observation, study, and manipulation of the mechanisms of bodying and worlding. VR provides the capability of creating custom experimental installations where the environment, our own appearance, and the presence or representation of others, can all evolve and adapt dynamically to (joint) behaviors while carefully controlling actionperception coupling parameters.

VR has seen its scientific use spread and is considered by now as “valid and highly ecological without compromising experimental control” (Loomis et al., 1999). It has been used in a wide variety of fields including psychology, anthropology, ergonomy, neurosciences, both as an experimental tool and as a therapeutic application (Okun 2017), particularly in the treatment of mental illnesses (Freeman et al., 2017; Wiederhold and Riva, 2019; Ascone et al., 2020). It has been applied to the study of the psycho-affective dimensions of art and mediated communication (Quesnel et al., 2018), and in the exploration of social mechanisms at play during an interaction, such as body mimicry (Forbes et al., 2016), or feeling of copresence (Garnier et al., 2017).

Interestingly, one of the first experiments to validate the potential of VR as an experimental paradigm targeted body ownership (Slater et al., 2010). The “rubber hand illusion” experiment (Botvinick and Cohen, 1998) has shown that visuotactile stimulation gives the illusion of embodiment with a substitute hand. Such embodiment techniques have been shown to result in the illusion of body ownership over the surrogate body–whether a physical manikin body (Petkova and Ehrsson, 2008) or a virtual body (Slater et al., 2010). The very sense of self can be altered when inhabiting an artificial envelope. Numerous studies (De la Peña et al., 2010; Banakou et al., 2013; Kilteni et al., 2013; Peck et al., 2013; Lugrin et al., 2016) observed how users’ virtual appearances can affect their thinking, feeling, and acting. For example, Banakou et al. (2018) explored how switching between bodies can help the user to work on personal issues from an outside point of view. Yee and Bailenson (2007) provided evidence for what they named “Proteus effect”: how the participant avatar’s appearance affects the participant’s behavior, during virtual experience but also following it. Gonzalez-Franco et al. (2020) showed evidence of the “self-avatar follower effect”, demonstrating how an avatar can induce movement from its user by creating small gaps between the virtual and physical bodies. When it comes to social interaction in VR, Nowak and Biocca (2003) showed that the degree of empathy that immersants express for each other isn’t correlated to the anthropomorphism of the avatars. Rather, the willingness to contribute to a group task as well as the performances obtained are more linked to visual similarities between participants and self-identification (Wallace and Maryott, 2009; Van der Land et al., 2015). This tendency has been used as a narrative argument in the popular video game Journey (2012), where players are immersed into a solitary experience in a vast landscape and may get a strong feeling of copresence after the unexpected appearance of another similar avatar to collaborate with. More generally, anthropomorphism often leads to expectations that can’t be met, while iconic representations may lead to more excitement (Nowak and Biocca, 2003).

Along similar lines, anthropomorphic cues are not necessary for copresence to emerge. For example, Froese et al. (2014a), Froese et al. (2014b) used Lenay and others’ “cross-perceptual paradigm” (Auvray and Rohde, 2012), where sensory information about the other is reduced to a very minimal representation: pairs of participants explore a one-dimensional space with their finger on which they received a tactile stimulation whenever another entity (the partner, a lure following the partner at a constant distance, or a static object) was present in their receptive field. This minimal sensorimotor structure was sufficient enough to bring about collective dynamics between human partners and participants. Indeed, Auvray et al. (2009) showed that even when participants could not consciously differentiate between the (responsive) partner and the (non-intentional and sensory deprived) lure, they were attracted by each other’s movement so that they spent more time interacting with each other than with the lure (in other words, they found each other collectively before each could find the other). When participants were invited to cooperate to find each other and co-regulated their interaction, they were able to recognize the other during these minimal interactions, and the feeling tended to be mutual [Froese et al. (2014a), Froese et al. (2014b)].

VR can propose either a modelization of the real world based on an environment which imitates or mirrors the real world or the creation of an artificial environment which does not correspond to anything which exists (Fuchs et al., 2006). It almost always also reduces or diminishes the richness of perceptual information, by design or by the limitations of the current technology. We find that this potential of VR to reduce, simplify, prune, or limit the perceptual field and the sensorimotor contingencies of the experiencer echoes a fundamental aspect of both art-making and experimental science.

The tendency towards abstraction1 and minimalism2 is indeed one of the major characteristics of artistic practice in the 20th century and can be found in a variety of artistic fields and media, be it visual, sound, or movement arts (such as dance or theatre). Similarly, a basic property of any experimental apparatus is to abstract away multiple features of the real world in order to be able to isolate the effect of specific factors or their interactions. Learning from minimalist art and science making, we suggest that the reduction or simplification of sensory data in immersive VR is a design feature rather than a problem to overcome.

As an important emerging medium within the digital arts, VR challenges our perception of space, time, and self for narrative and esthetic purposes. Through the use of graphic enhancement and motion capture, numerous contributions in dance and other interactive art have explored, through abstraction, the materiality of bodies themselves. Bodies can appear as made of smoke, sand, dismembered, or decomposed. In “Ballet Rotoscope” (Euphrates, 2011), the Japanese collective decomposes the movement of a ballerina and alternatively replaces it by trails drawn by her hands, or by bounding boxes. In “Co:lateral” (Barros and Moura, 2016–2019) and “Unnamed Sound Sculpture” (Franke, 2012), the body textures are made of shades, sparky particles, and smoke, making the movement and the body limits blurrier. In “CLINAMEN” (Arcier, 2020), three dancers are composed of multiple spheres, moved by randomly placed movement trackers on their whole bodies. Bodies are mixing, making it harder to differentiate one from another. In these artworks, dancers’ expressivity remains perceivable through the abstracted qualities of motion, and through their appropriation of space.

These experiences and artworks demonstrate how VR design choices impact the way we build our representation of the world. Digital paradigms can also affect our sense of self and allow one to play with the contours of otherness, and limits of human-like entities. In “Body Remixer” (Desnoyers-Stewart et al., 2020), several users see their own silhouettes displayed as particles on a wall, and a single user experiences the scene through a VR headset. In “Your Place And Mine” (Sra et al., 2018), the authors explore the idea of moving and dancing simultaneously in different locations, embodied into realistic human avatars. In “Spheres, a Dance for Virtual Reality”, Neville (2019) adds the idea of haptic connexion to others. A single participant interacts in VR with abstract silhouettes, and some luminous spheres are connected to their hands. When they enter in contact, the participant feels a vibrating feedback from the controllers. Some VR platforms now allow multiple users to dance together with different levels of avatar realism (DanceVR, WaveVR, VRChat). While the user can only control the hands and head of the avatar (no foot tracking), the rest of the body is animated in either autonomously or in a concordance with the tracked members. Taken together, this corpus exemplifies that more than being a technical constraint, the idea of reducing the set of perceptive information coming from our own body and from social interaction offers new directions for inquiry and artistic creation.

Building on these ideas, in January 2019, we initiated the Articulations project, a collaboration between the virtual spaces design research group at the ENSADLab and the ICI project (Himberg et al., 2018) research group interested in the study of interaction through joint dance improvisation. The project led to several public presentations as well as the formalization of a concept that we call Shared Diminished Reality (SDR). We next discuss the platform and its design process, and then propose a formalization of SDR and two different evaluations of our approach.

Financed by the new ArTec graduate school (http://eur-artec.fr/), the Articulation project stands at the tangential point between the artistic and scientific practices, exploring what minimalistic body representation in VR can offer, both as an artistic material and a research tool (Figures 1, 2). The initial idea of this research was to study interpersonal dynamics and the emergence of autotelic creative behaviors through the abstracted representation of movement and bodies, made possible by the use of virtual reality.

The operating principle of the project was to foster a real-time innovation dynamic between the artists, the scientists, and the designers through constant iteration between interface development and technological improvements. The process included in-group residencies and workshops, structured experimentations, and performances open to the public.

In the three residencies that took place in 2019, we invited the team and various guests – artists, cognitivists, philosophers, anthropologists, designers – for a collaborative experience, letting everyone’s domain of knowledge or practice influence the design process. Immersing ourselves in a shared virtual reality scene, we explored what seemed relevant, avoidable, and essential to let a playful sense of self emerge.As questions and suggestions arose about the virtual surroundings and the form of the avatars, we took advantage of the quick editing capacity of VR, manipulating at will the reduced bodies and environment appearances. Designing through experience, as well as through debriefing and sharing, we sought to reach a balance between shaping a comfortable visual experience and keeping a relatively abstract scene that would let us explore how body diminution influenced our willingness to engage in the virtual relationship.

The creative residencies also allowed us to collectively formulate hypotheses we then tested more formally during a series of public sessions and open-ended aesthetic insights that led to the development of a VR dance performance. Collectively, they led us to the development of the Articulations platform: a minimalist environment where subjects interact in a minimalist manner.

In this platform, participants are equipped with virtual reality helmets and two wrist trackers. Once immersed, they see two spheres representing their own hands that move in accordance with their movements. When the scenario is started, the other participant appears, consisting of three spheres representing the positions of their hands and head (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Several changes in the environment and the appearance of the participants can be automated or manually controlled by the team via an external interface.

The design goal was to play with the perception of oneself, of the other, or of movement itself, in time and space and how such changes influence the feeling of being independent or the sense of togetherness. Considering the research on Proteus effect (Yee and Bailenson, 2007) and how avatar representation can influence how users behave, spheres were chosen as the embodiment shapes. Through our own experience, we believed that this design simplicity would allow our users to approach the experience with a playful spirit and with less aprioris.

The virtual environment itself was chosen to provide a good balance between minimalism and comforting surroundings. The wide blue sky, the natural-like lighting, and the marble floor offer something rich enough to arouse the desire and confidence to explore while focusing the user’s attention on the interaction with the other or with the behavior of one’s avatar.

The platform was also designed in a way to enable us to experiment with various changes, either on the environment itself or on the user’s perception of self or other representation. For example, at times during the experience, participants could notice the addition of a mirror (Figure 5) that would help them to interact while seeing their own reflection. They could also see the colors of their own or the other participants’ spheres change (Figure 6). They would also experience the extension or reduction of the perceived size of arms by offsetting the sphere position, and even making them invisible overall. Lastly, there was the possibility to add or replace the spheres with other aesthetic features, such as particle systems’ emitters whose behavior would change according to movement qualities or generative virtual shapes that would interconnect visually the movements of both participants. Some of these changes in the visual scene or feedback embodied the questions or research hypothesis that guided, or emerged, during the different phases of this project.

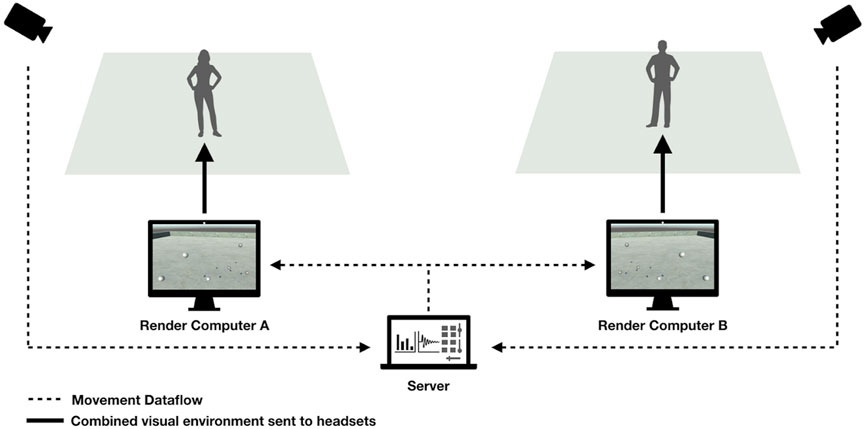

In terms of software, the Articulations project provides a multiuser virtual platform, with a networked clientserver architecture (Figure 7), all developed using the Unity3D platform.

FIGURE 7. Illustration of the Articulations basic technical setup. Additional “viewer” devices can be connected to the server.

For the first exploratory phase of the development, additional tools, plugins, and frameworks provided by the Unity 3D community were used. This allowed us to quickly prototype a serverclient architecture of a virtual multiuser environment. This first version was developed in order to conduct experiential sessions during the team’s first residency, which took place in Meriel, France, in May 2019. This prototype allowed for up to four users, using the HTC Vive, to be simultaneously immersed inside the same virtual environment (VE) through a network of clients.

Each user was represented with three spheres, initially two of the same size for the hands and one third, bigger, for the head. The larger head sphere integrated a black rectangular shape where the user’s face would be, in order to indicate the head’s orientation. The hand spheres were driven by the Vive controllers. The goal of these sessions was to experiment with the appearance of the avatar, as well as to better define the needs in terms of environment and interaction design. During the residency, interdisciplinary discussions led to eliminating the difference between the spheres so the head and the hands were the same size, and no head orientation was shown. This minimalism decreased the anthropomorphism and seemed to increase the playfulness of the encounters. Based on feedback from the Meriel residency, the second phase of the project was launched. It was decided to opt for a custom-developed OSC-based client/server system3, which would allow us to better handle the connections and the interactions implemented, and also render our platform-independent from third-party developers. This is of great importance, as Articulations is a research project and parts of it are intended to be eventually made open source, so that other researchers can further contribute to its evolution.

The architecture allows for a single server to host multiple clients which are assigned roles. The two main clients are the immersed participants while other clients can connect, assigned the role of a viewpoint. The server handles the evolution of the VE and the multiple conditions that are implemented in the form of scenarios. The server is in charge of creating data files to store all the information during each session, such as date and time, the conditions used, the duration, as well as the position and rotation of all the tracked body parts of each client.

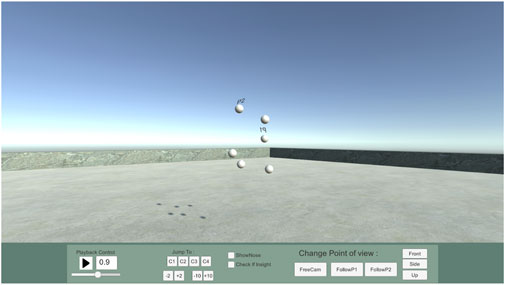

A separate interface was designed for the viewpoint clients, which allows them to either mirror the viewpoint of one of the main clients or manipulate a virtual camera to navigate the VE. A viewpoint client cannot alter the session and is not visible by the main clients. The viewpoint client (Figure 8) was conceived for three potential purposes: having a rendition of the virtual scene projected on a screen, in order to give the audience a third-person point of view; tracking an external tablet that would serve as a virtual camera with the possibility to move freely into the physical space, and allowing participants to do a post-experiment reviewing and commentary of their performance.

FIGURE 8. The user interface named as the “Viewer”, where one can watch a live or past performance from a third point of view.

The environment can evolve on demand: from a minimalist arena to a dance studio, or to more artistic landscapes. The ambient light, symbolized by a Sun, can go from deep night to full daylight, its intensity varying according to the time of day chosen. A mirror (an optional feature that played an important role in our experimentations) allows participants to see what they look like and how their movements appear (both individually and as an ensemble).

A critical aspect of the installation design, whose importance we came to appreciate more fully through experimentation, is the mapping between the physical and virtual localization of the two movers in space.

In the first prototype we developed (on the left in Figure 9), the physical action space and virtual space were superposed. This choice was motivated both by an implicit heuristic of the research team to maximize the overlap between the virtual and physical interaction and technical limits of the tracking devices. The size of the virtual space and the location of the avatars in it were identical to the physical space (participants could physically touch each other) and so the participants were offered a partially coherent visual, tactile, and auditory experience. However, since the avatars only represented three points on the body, the rest of the body was invisible (partially dematerialized), generating surprising (and potentially dangerous) collisions in the physical space.

For technical reasons (helmet cables getting intertwined) and to avoid recurring collisions between the subjects, it was decided to separate the respective positions of the participants, distancing them from one other physically, while keeping a face-to-face position in the virtual visual space (on the right in Figure 9). The new arrangement thus produced a different mapping between visual, haptic, and auditory feedback. The body of the other was visually dematerialized. This dematerialization was confirmed by the absence of haptic contact. The distancing attenuated auditory cues from the partner, which also reduced and altered the verbal interactions.

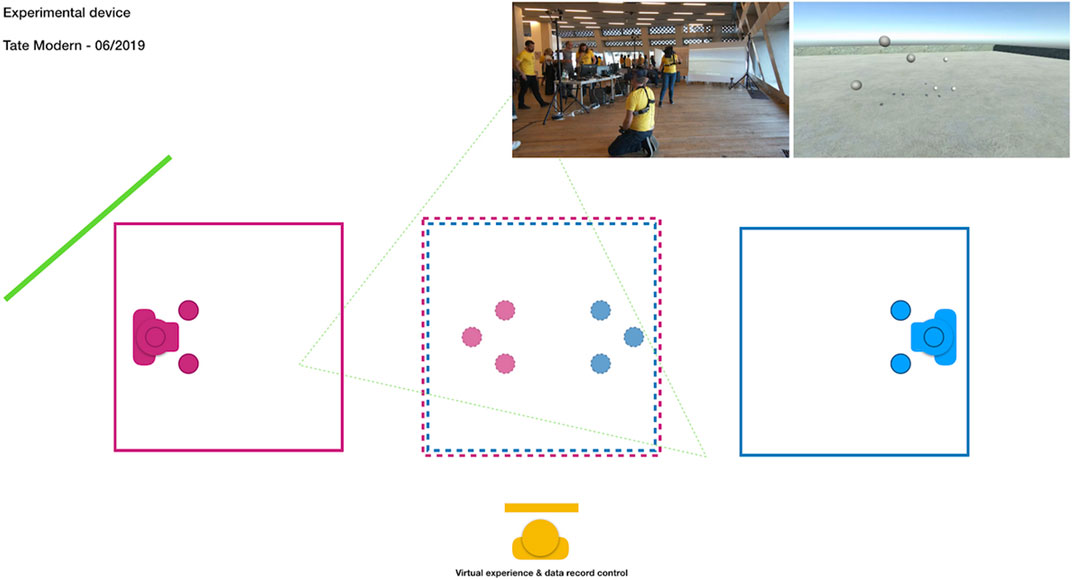

For the public event that took place in the Tate modern museum in June 2019, we made use of the wireless Vive set-up for the first time. This setup allowed for lighter and freer movements by the participants but required total separation of their physical positions (Figure 10). The total decoupling of the visual spheres from the physical position of the partner’s body prevented many participants (naive regarding the workings of the platform) from making the connection between their physical partner and the 3-sphere avatar. Similarly, for an outside observer, it became harder if not impossible to “read” the mapping between the physical and virtual interactions. The same spatial configuration was later used for an experimental session in the Pouchet CNRS center in Paris.

FIGURE 10. Spatial configuration used during the workshop at the Tate Modern in June 2019. The green triangle represents the viewpoint of the camera projecting a 2D representation of the experience on a screen (the green bar).

Through our research-creation process, we found that dissolving (the experience of) humanness by minimizing the visual perception of one’s self and one’s partners seemed to enhance creativity and expressivity.

Deprived of most usual communication clues and with diminished environmental distraction, participants dynamically engaged in responsive interaction and deployed rich ingenuity in creating a shared vocabulary through abstract movement. In line with Heider and Simmel (1944) and Lenay’s group (Auvray et al., 2009; Deschamps et al., 2012), we observed how simple objects in movement can convey emotion, and be the basic building blocks of a relationship as long as we find in the moving object a sense of “otherness”. From an experience design perspective and in dialogue with cognitive science, art performance, anthropology, and sociology, we would like now to summarize how these observations address the design research field, by formalizing them into a more general concept that addresses inter-relational dynamics through abstraction in VR. We call it Shared Diminished Reality (SDR), recognizing that shared VR requires only minimal design features, and this may be ideal in foregrounding interactive copresence in a shared space.

As we discussed above, VR always diminishes the users’ experience of their own body and the environment. By removing their bodies, we, as designers, modify their bodying experience with the world, and therefore their sense of being and presence. The SDR perspective builds on this fundamental aspect of VR to explore new paradigms of interaction at the frontiers of humanness and relationship by tweaking bodily appearances and expressive channels. New behaviors emerge through these virtual interactions, with which users compose relations and experiences.

Virtual bodying is afforded/made possible as long as users are able to easily feel present. Sense of presence, as a concordance of senses of agency, self-location, and body-ownership (Kilteni et al., 2012), may be reached as long as the virtual world’s rules are understood and integrated. In a Diminished Reality design, one aims at offering the minimal set of information allowing for rapid and intuitive self-location and self-motion perception (Lopez et al., 2015). However, the affordances of the environment (what one can do or how one can interact with it) should be minimized. The proximal or action space of the user should remain purposefully empty. When alone in the diminished environment, after a few seconds of uncertainty, the user has “figured out” their location and organization in space. However, when Diminished Reality is “shared”, body-ownership, agency, and ultimately the sense of presence emerge through interaction with another. Making Sense (of self and the world) becomes inherently relational, fostering the necessity to engage with the other. The user’s (re)actions create differences that are used dynamically as affordances for the sense-making by the other (De Jaegher and Di Paolo, 2007; Kimmel et al., 2018).

SDR is therefore a framework for designing multi-user experiences, where the main goal is to find the right balance between removing as many bodily and environmental affordances as possible while providing the minimum needed to allow a sense of (co)presence, expressivity, and interaction. We consider that balance as central in shared VR, and decisive to give our users a space to let (collective) creative flow happen (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997). SDR proposes to shape the channel of interaction in order to make the (shared) sensory-motor loop lighter and more transparent to the users and researchers.

In Articulations, our goal was to focus on the observation of shared movement and the emergence of collective creative flow. In phase with the enactive literature and priming effects that are operant also in the virtual, the world was carefully shaped with a naturalistic open sky and a vast floor, showing clearly that nothing in the global environment had to be figured out. Making use of smooth spheres as avatars, the bodies remained minimized to very basic information. We invited the users to freely explore the environment. There was no “task” or goal to be accomplished, leaving the users to (co)create their own experience. Finally, to minimize the presence of technology, we chose to replace the cable with a Wifi adapter, and the controllers with trackers placed on their wrists that gave our users the ability to move into the scene with less attention regarding the hardware and keeping their hands free, concentrating on inhabiting the interactional scenario. Everything was designed to keep the focus on movement relationalities.

The Articulations experience has been created through interdisciplinary innovation. A critical component in such a process is the (collective) evaluation of “working hypotheses” regarding the effect of certain parameters on user/“in-world” experience leading to design choices. Design evaluation is in reality an ongoing dimension of the design process itself. However, in a design research process, there are “major” moments where intuitions, ideas, observations, or accidents/surprises that emerged during the design process inform a more formal evaluation step. We present this evaluation step of the platform and the SDR framework it embodies two distinct epistemological forms:

A “laboratory” installation for movement interaction studies: An installation that takes the form of a laboratory experiment, allowing us to collect both real-time kinetic data and post-experience subjective reports. The installation is used to test specific hypotheses or answer specific questions. Below, we briefly discuss an experiment that used kinetic data to test our hypothesis that reduced visual feedback of one’s own body increases interpersonal coordination. We will then turn to the analysis of user reports in order to evaluate whether SDR design brings about a creative attitude in participants, a meaningful relational experience between them, and the experiential effects of the minimalist body representation, minimalist decor, and open-ended scenario/invitation.

- A “research-creation” installation that made use of a performative form based on the dematerialization of bodies in dance. Research-creation process evaluates a proposition in terms of whether it continually generates new questions. Through the creation process that we report here, new questions emerged about the potential of the hybrid virtual-physical space as “mixed reality”.

Below, we discuss these two forms separately. However, it is important to keep in mind that in practice, the different installations are not separate but interwoven and interconnected.

One of the original motivations for the Articulations project was the creation of a VR framework that allows for an ecological but controlled study of movement interactions. This section presents a brief summary of an experiment that allowed us to collect meaningful data on relational movement followed by detailed evaluation of the quality of user experience in SDR based on analysis of questionnaire and interview data. The full description of the protocol and the exploration of movement data are not covered here and may be found in another paper (Laroche et al., accepted).

To evaluate the potential of SDR as a fruitful context for the acquisition and the quantification of movement interactions data, we organized a number of public sessions that were conceived as ecological laboratory experiments making use of the Articulations platform. A total of 42 participants were invited to explore the Articulations world in dyads (as described above)4. In the spirit of SDR design, there was no task or goal beyond autotelic exploration. Even though both participants were briefed about the experiment at the same time and started the experiment in the same room, their copresence in the virtual environment was not made explicit before the experience. As we mentioned earlier, one of the consequences of the reinforced dematerialization of the bodies through spatial dislocation was that, if they were not warned, the participants did not immediately know the other spheres to be the physical partner. Without the ability to use voice, facial expression, limbs, fingers, or even orientation of the spheres as communication cues, participants needed to invent gestural strategies to dynamically figure out what relational situation they were in, and to potentially realize that another human inhabited the other spheres. In any case, this situation entailed a very playful exploration.

Since our system allows us to synchronously track the motion of the (2 × 3) spheres, we can extract kinematics features (e.g. pace or intensity of movements, or similarity across partners) in different conditions (e.g. seeing one’s own hands or not) and relate their variation to first-person experiences reported by the participants. For example, we have shown that losing the vision of one’s own hands increases the coordination of hand’s motion across partners and that those who felt closer to their partner in that condition had more similar displacements in space to that partner (for more detailed, see Laroche et al., accepted). The ability of the experimental setup in that experiment to produce meaningful cognitive science results demonstrates the potential of the Articulation device (and more generally Diminished Reality) as an experimental paradigm.

Here, we focus on the SDR experiential reports by users. These allow an expansion of the meaning of VR experiences and new important distinctions for future experimental design. The protocol and the observations described below come from a second experimental session (October 2019) performed in the Pouchet CNRS center in Paris. After each dyad completed their 12 min of improvisation (similar to the protocol used in the Tate), we proceeded to solicit their experiential reports in three stages. First, a pre-recorded message, played through the headset’s headphones, prompted participants to verbally report their feelings while still navigating the same virtual environment with their own avatar, yet in absence of their partner’s. They were asked to report their experience of the moment, as well as the changes they notice compared to the beginning of the experience, or anything else they wanted to share about the experience itself. After the headsets were taken off, the participants were accompanied to a small room where they completed a questionnaire (individually). The questionnaire was composed of a quantitative section (the participant was asked to indicate their adherence to 26 different assertions regarding the experience: from 0: not at all to 6: strongly adhering), and a section with open questions allowing for personal elaboration. Once the questionnaires were completed, the two participants were interviewed, together, by two team members (an anthropologist and a psychologist) following a semi-structured protocol.

The choice and wording of assertions were grounded in reports collected from the users of the installation during the previous experimentations and collective retreats. Reviewing the answers to the questionnaires and the transcripts of the conversations from these earlier events, we identified and collected statements that addressed specific aspects of the personal experience most relevant to our research interest (relational movement, bodying, immersion). Importantly, we formulated the questionnaire by staying as loyal as possible to the wording from the first-person experiences, reformulating them only when in need to precise, clarify, or stylistically adjust the language5. Adhering to the verbal descriptions provided by the participants themselves was fundamental to keep away from our abstractions and expectations and to address the subjective experiences directly.

The 26 assertions in the questionnaire could be split into three overlapping categories (Table 1). 1) Assertions regarding the virtual environment and the degree of engagement in the experience (ex: “I found the virtual space silent and seductive”), 2) assertions regarding the participants’ experience of their own body and movement (e.g. “I had a pleasant sense of lightness”), 3) assertions regarding the relationship to the other avatar/participant (e.g. “my movements were motivated by what I thought the other person could see”). Six of the assertions focused on the specific modulations introduced during the experience (ex: “I did not pay attention to the reflection of our movements in the mirror”). The list of assertions was composed of positive and negative formulations and of evaluations associated with positive and negative valence. The ratings of the six assertions regarding the specific modulations were used as factors in the analysis of the quantitative data (Laroche et al., under review). Here, we will focus on the rating of the assertions concerning the globality of the experience, proceeding by category. For each category, we will point out assertions on which there was a relative agreement across participants (defined as a mean score higher than 3.5 or lower than 2.5, with standard deviation lower than 2, cf highlighted rows and whiskers in Table 1 and Figure 11) and will provide related qualitative statements produced by participants during the monologue or interviews.

FIGURE 11. Quantitative results of post-experiential questionnaires. Highlighted whiskers correspond to the highlighted assertions in Table 1, and orange lines represent the means.

Overall, participants found that the minimal aspect of the virtual environment was inviting (A9 m = 4.48, sd = 1.47) and enhanced their curiosity and creativity (A23, m = 4.38, sd = 1.6). Overall, the immersion experience was not disturbed by elements of the “real world” (A11, m = 1.55, sd = 1.23). The absence of a pre-specified goal or instructions regarding “what to do” did not hinder the experience (A32, m = 1.79, sd = 1.83). In the interviews, the term “silence” and the minimal aspect of the design came up a number of times:

“The silence was so deep that I could imagine wind just in my head, moving my hair, probably it was by hearing my own breathing.” (P30)6

“The fact that the environment was so minimalist allowed me to avoid parasitic variables to the experience so in my mind there is nothing to add.” (P11)

Several participants shared that the experience produced a “sensation of freedom” (P36, P43). Being immersed and totally engaged with the experience, participants had a sense that time was slowing down:

“Time seemed to pass much more slowly, I was thinking of nothing but the problem of the “spheres” in front of me.” (P23)

Immersion in the experience could be so strong as to attenuate participants’ interoceptive awareness:

“the feelings of the heat and exhaustion I accumulated while moving in this machine-heated room came to my awareness only at the moment I took off the headset.” (P23)

This last comment highlights how VR immersion can have a powerful impact on one’s experience of their own body and movement. A theme we turn to next.

In the questionnaire, participants reported a sensation of lightness (A34, m = 4.28, sd = 1.56), once again suggesting an important impact of the immersive VR experience on their interoceptive and kinesthetic awareness and body image. This theme appeared also in the interviews:

“I still remember the first 20 s when I was learning to use the space, to use the absence of my “body” and the transition in which I become immaterial. This condition is a bit weird, because I felt myself closer to the ground than I used to be.” (P30)

One participant related this sense of lightness, or absence of a relationship to the floor (gravity), to a more fluid experience of their movement:

“No connection to the ground, allowing for a more fluid movement.” (P29)

The minimal visual body representation heightened the kinesthetic quality of self-awareness:

“My body mass didn’t exist, only my movement.” (P43)

“The opening of my movements towards a space that is larger, a more elastic feeling and warmth, a kind of inner energy.” (P20)

Our questionnaires did not contain assertions concerning transformation or alteration of self-identity, but in the interview, this theme came up regularly:

“I understand myself better, it is clearer.” (P52)

“I adopted and accepted the idea of being just 3 balloons, and I decided to feel myself fragmented.” (P30)

“It is an experience that has awakened in me completely new sensations and emotions in relation to my body and its movements and its relationship to others.” (P44)

As the last quote suggests, the experience of one’s body and one’s movement was intrinsically intertwined with the presence and experience of the “other” (spheres of partner) or the relationship. We turn to the relational dimension of the experience next.

It is interesting to note that most participants were not immediately aware that the “other” three spheres in the virtual environment were the avatars of their physical partner and that some realized it only later during the interview. Despite this fact, participants did report an important positive impact of the other spheres and the relationship with them on their experience. Participants overall agreed with the assertion that the presence of the other amplified their movements and creativity (A22, m = 3.7, sd = 1.8). In the interviews, a variety of relational experiences were shared:

“Here, I discover this great satisfaction of being followed or chased around. This is the main thing that I learned about myself.” (P47)

“This ‘innocence’ makes me say (to myself), be careful, in your relationships, be vigilant.” (P13)

“[I found out] That I’m a very solitary person because I didn’t notice the movement of my partner and I was happy being on my own.” (P27)

“I took it as a game, where the balls ask me for things I have to give, and then I realized it was the other.” (P31)

For some, the minimal body representation of the partner limited their ability to “read” them and interact:

“It is very difficult to interpret the behavior and intentions of the other subject only through the movement of the three spheres.” (P15)

“It is by the direct experience of a body that I can represent it independently of any other virtual parameter (space, volume, temporality, movement).” (P46)

Overall, the combined feedback from the questionnaires and interviews suggests that participants were immersed in, receptive to, and inspired by the minimalist design of the environment. This extends to the “minimalist” design of the scenarios. The absence of a specific goal, explicit task, or instructions of “what to do” did not inhibit the movement or creativity of the participants but actually enhanced it. While the minimalist avatars made it more difficult for some to interact with their partners, they did alter body perception in interesting and novel ways, destabilized perceptual “habits”, and increased awareness to one’s own movement and to that of the partner. In particular, many participants did not recognize the avatars as their human partners at least for some of the experience, and as a consequence could experiment relationality outside the habitual social sphere. Importantly, we found that the relation had an impact on the experience of the virtual environment in a subtle but significant way.7

As a research-creation project, Articulations focus on the collaboration between artists and scientists as a means of discovering new questions pertinent to each of them. For scientists, this means learning how, for example, dancers engage with and explore the embodiment potential of VR in ways that non-dancer participants or researchers do not (the latter are more semiotic/signaling in their practice) leading to the creation of new forms of measurement (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994). At the same time, artists explore platforms like Articulations in order to develop new practices of artistic expression, including designing new sensations, through the creation of artworks. The collaborative participatory design brings about the creation of new concepts that dialogue with the emergent questions from the collaboration.

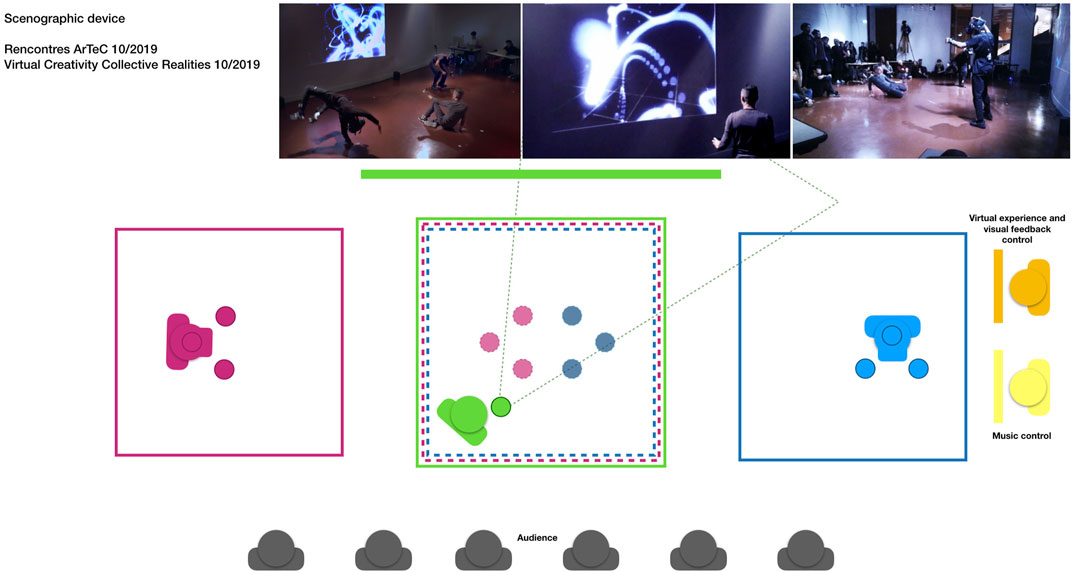

In the process of designing a performative version of the Articulations project, two performers and the choreographer Clint Lutes explored the possibilities offered by this new paradigm, in search of new forms of mediation through the dematerialization of bodies. The resulting performance was presented to the public twice, once during the Artec “portes ouvertes” presentation in the Center of Arts at Enghien-les-bains and the second time alongside of other performances presented in the scope of the “Virtual Creativity, Collective Realities” symposium which took place in the ENSAD in Paris (Figure 12).

FIGURE 12. Articulations Performance at École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, salle Rotonde (13–11–2019) with the choreographer Clint Lutes, the dancers Nassim Baddag and Sofian El Boukhari, the VR stage managers Dionysios Zamplaras and Loup Vuarnesson and the musician Baptiste Morin.

In this section, we will describe the creation process and the performance setup and timeline, accompanied by observations made by the performers and by observing team members. We will attempt to make visible how these different experiences brought about questions and hypotheses opening up new fields of research, some of which are currently being explored by our project team.

As previously stated, our research and design processes included three interdisciplinary workshops as well as three residencies that nourished both the theoretical and artistic approaches to the Articulations platform. Some of these sessions included the participation of several guests who were affiliated with dancing in various ways, either as professional dancers themselves or as non-professional practitioners of other movement or dance-related activities. It soon became clear to our research team that people with such a background not only perceive and experience the platform in another way but also reveal a certain performative aspect to those who are observing them. Thus, the idea of creating a spectacular form of the platform through a performance emerged.

One of the values of the design process of a performance is that the artists push the scientific researchers to test the limits of the platform. The performance creation process not only helped guide platform innovations but also created a common vocabulary between observers/researchers and the dancers/immersants. This allows for both scientific research design and performative design to converge towards a research-through-creation procedure, based on an ongoing interdisciplinary dialogue that ensures clarity for those members of the team unfamiliar with either design perspective.

The collaborative conception and design processes with the team and other researchers helped fuel ideas concerning the possibilities of the setup and interactions, as well as having feedback as to what they were seeing and sensing when watching the others in immersion. These experiences informed how we imagined the audience would react as the performance unfolded and how to best frame the actions so that they would best be perceived by the audience.

One important goal was conceiving a performance, revealing the inner working of our research, that was engaging, personable, accessible and that reduced the sense of distance that can occur due to barriers imposed by the elaborate technological setup.

Since the Articulations platform was originally conceived and developed to immerse participants inside a virtual environment, using it in the context of a public performance presented a number of challenges at many levels: technical, visual, stenographic, and dramaturgic. Both the choreography and the performance were then conceived in a way to address these challenges and produce a shared experience between immersants and audience.

One fundamental difference in experiential design between the “laboratory” installation and the “research-creation” installation was that in the latter, the audience had to be able to perceive the virtual space shared by the dancers and understand their actions and choices. The virtual reality experience had to become a mixed reality experience. Whereas in the “laboratory” installation, this virtual space was only addressed to the performer and therefore had no need to be perceived in the physical space; in the “research-creation” installation, it was essential to materialize their presence on stage for the audience.

Through the evolution of the platform’s design, the physical spaces of the participants became non-overlapping. In the first version, the participants could physically touch and collide (Figure 9). In the more advanced versions of the design (Figure 10, Figure 13), each of the dancers occupied a separate physical space. The physical space in between the spaces of each dancer (see Figure 13-green square) persisted however as a fictitious interaction zone. The technical platform itself was modified in order to present the performers executing choreography in the physical space, while sharing feedback from the virtual environment with the spectators, transforming their virtual experience into a shared one, by projecting the virtual world inside the performance’s physical space.

FIGURE 13. Research-creation installationThe red and blue zones are the action spaces of the two dancers, whereas the green zone is the Mixed reality spacethe mediator’s action space superimposed on the virtual space merging the presence of the dancers.

Two of the performers, whose practice is based in hip-hop movement language, were outfitted with virtual reality headsets. The choreographer opted to have the dancers engaging in a casual conversation throughout the performance, as if they were discovering at the moment the virtual environment and the possibilities of moving within it. This sort of low-key discussion invites the audience to understand the actions happening on stage and observe the performers and the setup. The fact that the dancers are wearing masks helps the audience to feel comfortable with this rather informal and intimate setting as it counters the fear of a reciprocated gaze. The choreographic language was a mix of hip-hop and contemporary dance that moved in and out of unison movement accompanied by custom created music.

This performance came out of our research-creation process, echoing many of the themes addressed experimentally elsewhere. While we didn’t conceive it as an experiment, testing hypotheses, it brought new insights and new questions to address in future research.

The whole performance was filmed, and we will now provide an analysis of the performance video-capture, attempting to formulate some of these emerging themes in the form of new questions. A part of this material has been published as a video of 11′30″ on Vimeo at: https://vimeo.com/392659020

Part 1: The presence/appearance on stage of a non-immersed “mediator” (00:00).

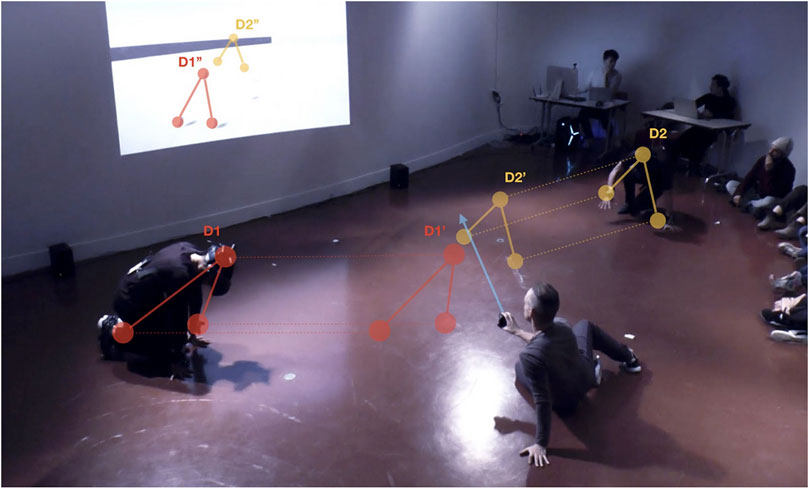

Upon the arrival of the audience, the performance team is already on stage: the dancers, the choreographer, the musician as well as the virtual experience designers. The dancers are already equipped with the VR headsets, which isolate them visually. Indeed, they will not make eye contact with the public until the end of the performance8. During the first minute, each dancer explores his own physical space, a square of 4 × 4 meters, inside which he can freely move. While both are physically located in separate squares, inside the virtual space, they can perceive each other as being in the same square. This virtual square is mapped to a physically empty space between them, but this cannot be perceived by the public. Inside this environment, they are represented each as a form composed of three spheres. They follow each other, crouch together. (00:38) With the help of a tracker, held in his hand, the choreographer controls the position of a virtual camera. Moving around the physically empty space between the dancers, the choreographer “reveals” to the public, through a video projection, the virtual space that is shared by the dancers and that is materialized in the center of the scene. (01:08)9.

To what extent are spectators able to map, in real time, the disparate movement of both dancers in the physical space to the empty physical space between them? Is a presence of a person/a physical gesture (the mediator/the tracking) necessary for this mapping to be successful? What is the lived quality of this mixed-reality space for the spectators and the choreographer?

Part 2: Modification of the perception of the corporeal dimensions (01:54).

The virtual experience designers modify the distance between the virtual spheres and the arms of the dancers, provoking a sensation of lengthening of the forearms. They start exploring their newly found virtual geometry of the body. The nature of their movements seems to be changing accordingly, and the gestures becoming slower, more amplified. The performers start describing their experience out loud.

Does the augmentation in perceived body size bring about an influence in the breadth and speed of movement? How could such an effect be used in future VR installations? Do spectators share the sensation/perception of the dancers’ virtually augmented bodies?

Part 3: Modification of self-appearance feedback in shared VR and impact (02:25).

The virtual experience designers make the spheres representing each dancer’s respective hands disappear, which surprises them and makes them feel puzzled and upset. They start to wave and mimic each other, in search of an affirmation of their self-existence in the virtual space. Then, they seem to “forget” their arms, making a few gestures with increased (full body) displacement in space. When the hands reappear, they thank the designer loudly, while checking if everything is indeed back to its normal state.

To what extent the absence of visual feedback of manual gestures modifies our peripersonal space and its distinction to the extrapersonal space? Can the absence of feedback stimulate the will to coordinate with the partner? Can spectators perceive the performer’s disorientation when its cause is invisible to them?

Part 4: Asymmetric mapping and the introduction of a virtual interconnected object (03:55).

The choreographer removes one of the trackers from the arm of the performers and places it instead on the ankle. The virtual experience designers change the visual setup by adding a flexible and modulable 3 days shape which connects the two dancers. This ladder-like shape gets twisted and torn apart by their movements. The dancers explore their influence over the shape and then fall into a playful dialog by acting one after the other on its deformation. The addition of the virtual connection between the dancers transforms the quality of the physical empty space between them which now becomes more vibrant and tensional.

How does the asymmetric body representation affect the movement of the dancers? Are spectators still able to perceive a coherent moving body via the projected image? Does a virtual object interconnecting the performers reinforce the perception of a mixed reality space for the audience?

Part 5: Movement tracing and 3D drawing (06:12).

The virtual spheres are replaced by glowing ones, capable of producing trails once they move. The dancers begin familiarizing themselves with this new self-representation and the tracing of their movements. One draws a trace; the partner takes a look at it and then joins10. (08:06) The trails persist more and more, eventually sculpting a form. Each dancer looks at it, completes it, and interacts with it. When they stop moving, the form vanishes progressively. The choreographer doesn’t film the dancers anymore but tries to find a right angle to make visible this co-created form on the screen for the public11.

When does a movement trace remain associated with the movement and when does it start to be part of the environment? Does such a fusion of movement and environment foster new levels of complex creativity for the performers and is it perceivable by the audience?

An important innovation that emerged through the collaborative process was the turning of this fictitious space into a mixed reality zone inhabited by the virtual presence of the two dancers and the physical presence of a third performer, a mediator embodied by the choreographer who was not wearing a headset, and who served as a bridge between spectator and performance space. In the version depicted in Figure 6, the fictitious zone was geometrically located halfway between the zones of the two dancers. We realized this virtual space would remain an abstraction for the audience if it was not actualized by a presence on stage (Figure 13-green figure). Thus, a “mediator” was necessary to make the link between these two realities: that of the real bodies of the two dancers on stage and that of their fusional and dematerialized presence in the virtual space (Figure 14).

FIGURE 14. Picture from the ENSAD performance in Paris. D1 and D2 show the sensor positions of the two performers on the stage; D1′ and D2′ simulate the positions of the performers in the virtual shared space; D1″ and D2″ show the performers position in the virtual space, on a projected picture framed by the choreographer.

Working closely together with the choreographer, the designers added the ability to use a tracked VR sensor coupled with a virtual camera, as part of the performance, in which the mediator could simultaneously be on stage as a participant “filming” the avatars of the immersed performers and their interactions inside the virtual environment. The camera’s output was then projected live on a screen behind the performers, directing the gaze of the audience to the performers’ movements in the live space, to their virtual interactions, and to the emerging relationalities in space/time. At the same time, the mediator used light touch to provide the two immersed dancers a link to the physical reality.

This mixed-reality shared experience is formed by multiple elements deriving from different dimensions, the physical space that includes the performers and the public, and the virtual environment that is being actualized through the performers’ gestures and interactions. Rather than conceiving the virtual and the physical as two discrete realities, the mediator’s presence turns them into a “continuum” along which he seamlessly moves to provide glimpses of the events happening in another dimension.

The notion of the continuum finds its origin in the work of Paul Milgram and his research team (Milgram and Kishino, 1994). In their work, they introduced the concept of the reality-virtuality continuum. They proposed the concept of a virtuality continuum in the context of visual displays, but their ideas have since been adopted and extended to fit all domains of research around virtual and mixed reality, whether scientific or artistic (Georgakopoulou et al., 2019).

In their publication “Enabling a continuum of virtual environment experiences”, Davis et al. (2003), inspired by Lewis Carroll’s book, “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, attempt to extend the concept of the continuum. They are referring to the story as a metaphor for moving through various dimensions of reality. At the beginning of the story, Alice meets the White Rabbit, a creature from another dimension. At this point, they propose, the rabbit is part of Alice’s reality, and at the same time, it doesn’t belong there, thus augmenting her reality. We argue that in fact, the rabbit is very much part of Alice’s reality as well as part of another reality. He is able to inhabit and seamlessly move through the different dimensions.

The rabbit then acts as an interface, an intermediate, guiding Alice through immersion. Their meeting is a key point to the story, as it marks the moment where her reality becomes augmented by the presence of an element of another reality. Much in the same way in our case, during the performance, the third performer becomes the White Rabbit, assuming the role of a mediator between the multiple dimensions, while his presence augments the audience’s reality.

The recent emergence of shared VR has challenged designers to conceive enjoyable and satisfying experiences of free, creative joint exploration. Interacting in space through movement offers new paradigms for interaction design. In this article, we proposed the notion of Shared Diminished Reality as a design guideline for such development and presented a concrete project (Articulations) that instantiates this approach. Through our work on Articulations, we observed how letting abstracted bodies move and interact in a minimal environment without a predefined goal can result in the creation of singular and intimate expressive patterns.

The design of the platform was carried out by the iteration of experiments: collective embodied hypothesis generation, prototype design, and experiential evaluation. A good example of the potential of this approach is the evolving mapping between the physical and virtual spaces. In the original design, bodies were partially dematerialized (only certain body parts were co-localized with the avatar). We then found that it was necessary to create a physical distance between users to avoid collisions between the parts of the user’s physical bodies not visible in the experience. Furthermore, the partial dematerialization produced a strange sense of incoherence between the virtual physical copresence. The distancing resulted in a full dematerialization of the haptic presence of the other body during the VR experiment and a liberation of the users’ gestures and imagination. The distancing of the subjects has also de-anthropomorphized the experience of the “other”, as the users are no longer a priori aware that they are in the presence of the representation of another person.

The effect of SDR was evaluated using movement quantification, and experiential reports as well as the mapping between them. In turn, the mixed space (empty physical space inhabited by virtual movement) that resulted from the design process itself inspired the scenographic and dramaturgical development of a live audience performance.

Analysis of the kinetic data (Laroche et al., accepted) provides evidence for the impact of diminished reality on behavior. These results also point to the more general potential of SDR for scientific research on interaction. In the post-experience questionnaires and interviews, participants reported finding the simplicity of the virtual environment calming, appealing, freeing, curiosity inducing, and socially creative. They were moving and co-creating their own interactional rules, even though the nature of the “other” spheres was not always clear as to whether it was human or digitally generated. The user’s usual sense of self was altered by the minimalism of their own appearance while their visual similarity fostered a social encounter that made them improvise together.

Future studies should examine how these minimalist interactions interplay with the constant storytelling activity of humans. Our initial interviews with participants revealed the extent to which their perceptions, experience of the environment and others, and their emergent behavior are co-shaped by the stories they are telling themselves about what is happening. This suggests that open-ended experimental arrangements can reveal a deep flexibility of cognitive mechanisms that will be missed in less open-ended ones.

The participants’ behavior and post-experience reports regarding their interaction with the minimalist design can inspire new forms of interfaces and virtual agents. By carefully attending to relational movement, immersive experiences can become more social, but without the overdetermination of typical anthropomorphic avatars.

In the performative installation, the physical distancing allowed the dancers to explore new choreographic forms playing on the entanglement and fusion of dematerialized bodies in the VR space.

The dancers’ distancing also had an effect on the scenography, creating a median space locating the virtual reality zone on the stage. This zone, inhabited and actualized by the choreographer, transformed the VR experience into a mixed reality experience for the spectators and dancers. The choreographer’s role then became that of a mediator, an active passer between the virtual experience and the physical stage experience.

Interdisciplinary art-science labs are able to create innovative approaches to VR precisely by including multiple voices in all aspects of design, and by foregrounding play and performance as necessary aspects of this innovation. Our transdisciplinary approach offered us a way to conceive an experiment that is pertinent in each of these fields separately. Our platform, and its extension to the concept of Shared Diminished Reality, is the very result of the workshops and residencies, where we tried to express and adapt our concerns through the language of different research fields.

One important value of the hybrid research-creation procedures, such as the performance design of the Articulations platform, is in allowing for the emergence of a research through the creation process. This particular form allowed for extended experimentation with features and ideas that have occurred through the previous phases of the Articulations project. For example, the recording camera feature of the performative platform was an idea that has been put forth in the earlier stages of our project, long before the conception of the performance itself. In turn, the experience gathered through the performance will nourish the design of the Articulations project in its later phases.

By creating interdisciplinary art-science labs, practices of playful variation are brought into direct dialogue through scientists designing experiments, designers creating virtual environments, and artists designing experiences iteratively. Each member brings not only new questions about what can be done with technology but also brings their values, including different notions of fun, engagement, challenge, and novelty. This is similar to the video game industry, where players often reinvent games through the ways in which they play creatively with glitches, “mod” the games, and play new games on top of the apparent game (Boluk and LeMieux, 2017). These emergent practices often seed the next wave of games. Similarly, artists and dancers reinvent media such as virtual reality through engaging the technology within a frame of play and asking new questions (Kozel, 2007).

The Articulations platform was developed with and for dancers. This was both a strength and a limitation. It emphasized the creation of an environment that invites interactive movement exploration without verbal language. Choreographers, for instance, noticed things about distracting environmental features, and interpersonal signaling constraints that no one else did. Similar contributions were made by visual artists, programmers, anthropologists, and psychologists in the lab. The challenge of creating a performance tested the improvisational abilities of all the team members, while also providing a discrete goal to have a production-ready system. It sharpened the environmental design, the interactive formats, and the experimenters’ awareness of the experience of being in diminished reality.

The way we shaped our experimentation protocol is also something that goes beyond our usual work habits. The questionnaires and interviews were designed based on how we, virtual reality designers, sociologists, anthropologists, dancers, and cognitivists, had each gathered behavioral data within our own disciplinary frames. Concepts such as presence, sense of self, bodying, worlding, each have their own literature and references in our fields, but this confluence allowed us to stand at the crossroads of them, allowing each of us to learn new things that we can return to our fields with, what Cohen-Cole describes as the interplay between interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary (Cohen-Cole, 2007).

Shared Diminished Reality emerged from an interdisciplinary research-creation process between the laboratory and performances. By aesthetically abstracting the gesture from other forms of communication, it highlighted and confirmed the semantic and emotional power of the gesture and its central role in interpersonal communication. Scaffolding shared experiences, built on users’ emergent gestural vocabulary, seem to be an interesting lead to follow.

In our ongoing and future research, SDR remains an interesting framework to explore, both in the scientific and artistic fields. Extending our inspiration from the cross-perceptual paradigm, we plan to further investigate the SDR influence on coordination and collaborative strategies. Playing with the seams of shared mixed-reality spaces is also something we look to build upon in upcoming research-creation workshops. On the technical side, we are working at converting the platform to a more open and accessible multi-user mixed reality environment that can serve as a quick prototyping tool.

Virtual reality is certainly an art of the gesture, of the act in becoming, and this new artistic form is fully in line with the continuity of living art such as dance or improvisational theater, as much as the arts of temporal storytelling such as cinema.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

LV and DZ have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship; AB and FG share last authorship.

This work has been supported by funding provided by the French national agency of research through the program “Investissements d’avenir” (reference ANR-17-EURE-0008).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1See the artists, Vassily Kandinsky, Kasimir Malevitch, Robert Delaunay, Piet Mondrian.

2See the artists, Frank Stella, Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin.

3We chose OSC as it is a widely used protocol in the field of digital art, making it easy to handle data exchange even for non-expert coders and artists. Furthermore, the whole data encapsulation system is pretty simple and straightforward, making it simpler to build a customizable and flexible networking system.

4All participants provided written informed consent according to institutional guidelines of the local research ethics committee (in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki).”

5Further explanation on how the questionnaire was designed can be found in Laroche et al. (accepted).

6Each comment is associated to a Participant ID, such as P30.

7With respect to the concept of “shared VR”, one subtle but important finding in the analysis of the questionnaire regards the interdependence between one’s experience of the virtual environment and the dyad. We looked for assertions for which the responses of the two partners correlated significantly. We found that was the case for one assertion: “I found this minimalist and silent environment inviting” (r = 3.27, p = 0.032). A possible interpretation of this correlation is that one’s experience of the virtual environment was affected by and/or affecting the experience of her partner.

8Nassim Baddag, dancer: “I was rather surprised by the immersive technology and the effects […] I most certainly retain the impression I had when I removed the headset at the end of the performance, discovering the audience, the room, the “real life”.” Sofian El Boukhari, dancer: “The presence of the choreographer was not disturbing, rather helpful in orienting us temporally during the performance. Regarding the audience, it was rather motivating knowing their presence but seeing them only after the performance.”

9Clint Lutes, choreographer: “As I myself was also performing, I needed to take time to understand my own role, which was different from the two hip-hop dancers. Using this device (the handheld tracker) I moved around the other dancers and filmed what they were experiencing visually. So my role as choreographer and dancer merged in a sense with the role of mediator: not only was I mediating my ideas as a choreographer to the dancers who would perform, I was also mediating their experience with my own body and video camera to the audience.”

10Sofian El Boukhari, dancer: “The minimalist appearance can potentially allow for an exploration of other movements by designing forms.”

11Clint Lutes, choreographer: “What I found was that I was often filming what was happening between the dancers, the resulting effects of their interactions. I feel as if this key element of showing the space between the performers, highlighting the spaces around us, and directing the visual attention of the audience members will have an interesting effect on how I create work in the future. It will be interesting to continue working on how to open spaces (visually, or for reflection, physically...) and allow the audience’s gaze to wander to various elements rather than attempting to provide a clear focal point.”

Ascone, L., Ney, K., Mostajeran, F., Steinicke, F., Moritz, S., Gallinat, J., and Kühn, S. (2020). “Virtual Reality for Individuals with Occasional Paranoid Thoughts,” in Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Association for Computing Machinery), 1–8. doi:10.1145/3334480.3382918

Auvray, M., Lenay, C., and Stewart, J. (2009). Perceptual Interactions in a Minimalist Virtual Environment. New ideas Psychol. 27 (1), 32–47. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2007.12.002