- 1Department of Ecology and Diseases of Zoo Animals, Game, Fish and Bees, University of Veterinary Sciences Brno, Brno, Czechia

- 2Department of Veterinary Sciences, Faculty of Agrobiology, Food and Natural Resources/CINeZ, Czech University of Life Sciences, Prague, Czechia

- 3Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria

- 4Institute of Vertebrate Biology, Czech Academy of Sciences, Brno, Czechia

Introduction: The epidemiology of filarial infections is a neglected area of bat research, with little information on filarial species diversity, life cycles, host ranges, infection prevalence and intensity, parasite pathogenicity, or competent vectors. Furthermore, molecular data for filarial worms are largely lacking.

Methods: Here, we examined 27 cadavers of parti-colored bat (Vespertilio murinus) from Czech rescue centers for filarial infection using gross necropsy. We also used nested polymerase chain reactions targeting partial mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) partial gene to detect and genotype filarial parasites within organs, and ectoparasites of V. murinus from Russian and Slovak summer bat colonies. Samples with mixed filarial infections were cloned to extract separate sequences. The COI gene sequences were then subjected to phylogenetic analysis and a phylogenetic tree constructed. Adult filarial worms were also screened for the bacterial symbiont Wolbachia, using a standard PCR targeting the partial 16S rRNA gene.

Results: Two filarial nematode species were identified in single and mixed V. murinus infections, Litomosa sp. and a species of Onchocercidae. Adult Litomosa sp. nematodes were only recorded during necropsy of the abdominal, thoracic, and gravid uterine cavities of four bats. Molecular screening of organs for filarial DNA revealed prevalences of 81.5, 51.9 and 48.1% in Litomosa sp., Onchocercid sp. and co-infected bats, respectively. Adult Litomosa sp. worms proved negative for Wolbachia. The macronyssid mite Steatonyssus spinosus, collected in western Siberia (Russia), tested positive for Onchocercid sp. and mixed microfilarial infection.

Discussion: Our results revealed high prevalence, extensive geographic distribution and a potential vector of filarial infection in V. murinus. Our data represent an important contribution to the field of bat parasitology and indicate the need for a taxonomic revision of bat-infecting filarial nematodes based on both morphological and molecular methods.

1 Introduction

Filarial nematodes are thread-like vector-borne parasites of medical and veterinary importance (1). To be able to reproduce, adults of both sexes must occur within their definitive vertebrate hosts. Gravid females are ovoviviparous, meaning that they release larvae (microfilariae) that spread through tissues and/or enter lymphatic and blood circulation (2). Transmission between hosts occurs after the microfilariae are ingested by a competent arthropod vector, and develop into L3 larvae to become infective (3). Filarial worms are commonly long-lived and many species show low pathogenicity, causing non-life-threatening infections in animals. However, there are a few exceptions, such as the canine heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis), which causes cardiopulmonary infection (1). Furthermore, filarial infections can be difficult to detect at their predilection sites and may be overlooked in asymptomatic individuals (4).

While filariae are somewhat neglected as chiropteran parasites, the two best-known onchocercid nematodes of bats are of the genera Litomosa and Litomosoides (5, 6). Two species have been identified in the parti-colored bat (Vespertilio murinus), Litomosa ottavianii (7) and Litomosa vaucheri (8). While L. ottavianii was described morphologically based on a few dozen females and males collected from V. murinus and common bent-wing bats [Miniopterus schreibersii (7)]; L. vaucheri is known only as a single intact female and as an anterior and posterior fragment of a female, both specimens without microfilariae, from V. murinus (8). Litomosa ottavianii have also been reported from greater horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) in Serbia (9). Identified as Litomosa sp. using a molecular assay targeting the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1, filarial adults have recently been detected in the peritoneal cavity of a male V. murinus (10). Interestingly, microfilariae were present in both the semen and the testes of this bat. However, argasid mite larvae parasitic on the bat proved negative for filarial DNA, meaning that its arthropod vector remains to be identified. As morphological characteristics suggested a novel filarial species, and a full description of this new species has yet to be made (10), it has not yet been possible to link morphological and molecular identification in this case.

Many onchocercid nematode species co-evolved with the intracellular bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia, which plays an essential role in their biology and may be a target for anti-filarial drug treatment (11, 12). However, adult Litomosa worms from the peritoneal cavity of the parti-colored bat tested negative for Wolbachia (10).

To date, nothing is known about the epidemiology of filarial infections in V. murinus (10). Here, we utilized cadavers of V. murinus obtained from Czech wildlife rescue centers, along with macronyssid mites collected from V. murinus captured in a Russian summer bat colony, to examine filarial infection prevalence and distribution in the host body. Alongside necropsy, we used DNA-based tools to detect and genotype filarial parasites, their bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia, and to identify their potential natural vector. Given the necessity of increasing DNA amplification sensitivity, we developed a novel nested polymerase chain reaction (nested-PCR) assay for detection of filarial infection in bats. We then predicted host sex-related differences in infection prevalence in V. murinus bats based on different roosting abundances of female and male colonies.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sampling of bat cadavers and ectoparasites

Between 2010 and 2015, a total of 27 Vespertilio murinus cadavers were obtained from wildlife rescue centers around the Czech Republic (synanthropic habitats of the cities Prague) (50°5′15″N, 14°25′17″E), Brno (49°11′43″N, 16°36′30″E), Melnik (50°21′2″N, 14°28′27″E), Mnisek pod Brdy (49°52′0″N, 14°15′43″E). The cadavers were dissected and individual organ samples (testes, heart, spleen, kidneys, liver) and any adult worms found in the body cavities were removed and stored in 70% ethanol for further analysis. The examination of the bat cadavers did not reveal any ectoparasites. In contrast, live bats from Russia and Slovakia were examined only for ectoparasites, without the possibility of obtaining dead bats or other samples.

Ectoparasites of V. murinus were obtained from seven bats sampled from summer roosting colonies in Russia (Lukashino, western Siberia (57°19’N, 64°59′E), natural habitat; city of Voronezh (51°40′18″N, 39°12′38″E), southern Russia, synanthropic habitat) in 2018 to 2019, and Slovakia (Cierny Balog (48°44′50″N, 19°39′22″E), natural habitat) in 2022, the ectoparasites being removed with forceps and fixed in 70% ethanol for further analysis. In all cases, the bats were released close to their roosting sites immediately after sampling.

All 35 ectoparasites collected from the bats were determined based on morphological characteristics (13–16), and were represented by mites Steatonyssus spinosus (n = 27) and Steatonyssus sp. (n = 2), flea Ischnopsyllus obscurus (n = 5), and tick Carios vespertilionis (n = 1). The ectoparasites were then grouped into nine pooled samples according to their species and bat origin, five representing S. spinosus, two I. obscurus, one C. vespertilionis, and one comprising Steatonyssus sp.

2.2 DNA isolation

DNA was extracted from adult filarial worms, bat tissue (testes, heart, spleen, kidneys, and liver) and ectoparasites using the NucleoSpin® Tissue Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. An Implen NanoPhotometer (Implen, Germany) was used to evaluate the quantity and quality of isolated DNA by calculating the absorbance ratio at 260 nm and 280 nm. The DNA samples were then stored at −20°C until further use.

2.3 Molecular assays for detection of filariasis and Wolbachia screening

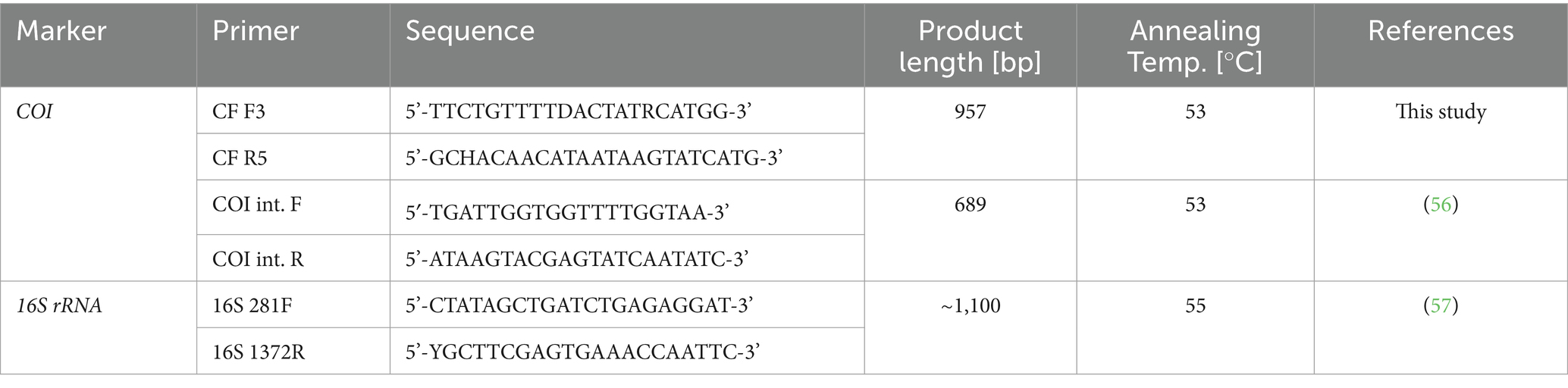

Two PCR sets were used in this study: a nested-PCR targeting the partial gene of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI), used for the detection and identification of filarial nematodes, and a standard PCR targeting the partial 16S rRNA gene, used for the detection of Wolbachia endosymbionts in the DNA obtained from adult worms (n = 5). Both rounds of nested-PCR targeting COI were prepared in a total volume of 20 μL, comprising 10 μL of Phusion Green Hot Start II High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), 0.5 μM of each primer (see Table 1), 2 μL of template DNA, and 6 μL of PCR grade water. The PCR targeting the 16S rRNA gene was performed at a total volume of 25 μL, comprising 12.5 μL of Super-Hot Master Mix 2x (Bioron GmbH, Germany), 0.4 μM of each primer, 9.5 μL of PCR water, and 1 μL of template DNA. For further details on the primers and PCR protocols, see Table 1.

All PCR reactions were performed using a MJ Mini™ Personal Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA), with a negative (PCR grade water) and positive (DNA isolated from Dirofilaria repens) control included in each run. The obtained PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with Serva DNA Stain G (Serva, Germany) under UV light. All PCR products of appropriate size were purified using the NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany), and then commercially sequenced using Sanger sequencing (SEQme s.r.o., Czech Republic). The obtained sequences were then aligned with available sequences in the GenBank database1 using MegaBLAST, and edited using Geneious Prime software (Biomatters Ltd., New Zealand).

2.4 Cloning

Samples showing filarial co-infection (represented by mixed chromatograms) were cloned using the Zero Blunt™ TOPO™ PCR Cloning Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) to extract separate sequences for both target organisms. Obtained plasmid DNA was purified from the bacterial culture using the GenElute™ Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), and then sequenced using universal T7/SP6 primers.

2.5 Phylogenetic and statistical analysis

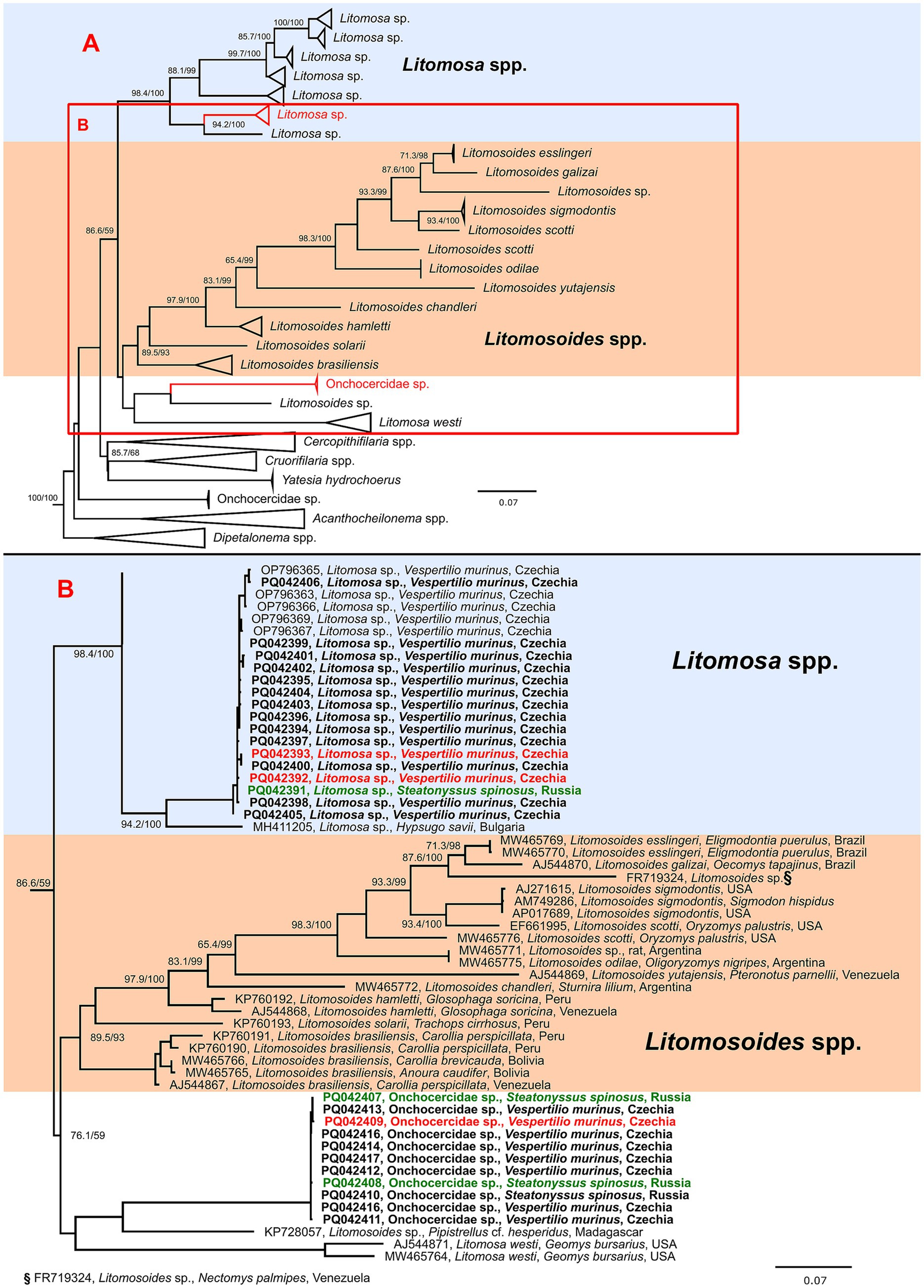

Two phylograms of the COI gene were constructed. First, a phylogenetic tree covering the entire superfamily Filaroidea was built to confirm and specify the identity and phylogenetic position of the sequences from the present study. Based on this phylogeny, a detailed analysis of Litomosa spp., Litomosoides spp., and closely related genera was performed. For the initial analysis, all unique COI sequences longer than 300 bp available in the GenBank database were used, while representative sequences were used to construct the second phylogeny (for further details on the phylogenetic analysis, including number of sequences used, algorithm used, length of final alignments and evolution models chosen, see Figure 1; for a more detailed representation of the phylogenetic analysis with all sequences used, see Supplementary Figure S1) All phylogenies were inferred by IQ-TREE version 1.6.12 (17) and the best-fit evolution model selected based on the Bayesian information criterion, computed and implemented using ModelFinder (18). Branch supports were assessed by ultrafast bootstrap (UFBoot) approximation (19), and the Shimodaira-Hasegawa-like approximate likelihood ratio test (SH-aLRT) (20). Trees were then visualized and edited in FigTree v1.4.42 and Inkscape 1.3.3

Figure 1. Schematic representation of a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on the cytochrome oxidase c subunit I (COI) gene sequences of genera closely related to Litomosa and Litomosoides spp. (A) with detailed phylogeny of part of Litomosa spp., Litomosoides spp. and related clade containing Onchocercidae sp. (B). The final length of the alignment was 638 bp and contained 182 sequences (27 originating from this study). The tree was constructed using the evolution model TIM3 + F + I + G4. Three sequences of Breinlia robertsi used as an outgroup are not shown. Sequences from this study are marked in bold and clones originating from the same sample are shown in matching colors (red or green). The scale bar indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. Sequences are labeled with accession number, species, host and country of origin (where available). Bootstrap values (SH-aLRT/UFB) above the 80/95 threshold are also displayed.

Prevalence of filarial infection was compared by testing the difference between two proportions, the Chi-square test being used to detect patterns of filarial infection distribution in all tissues excluding testes.

3 Results

3.1 Filariae in Vespertilio murinus bats: sequencing, genetic diversity, and phylogenetic analysis

Overall, 52.8% (66/125) of V. murinus tissue samples, 100% (5/5) of adult worms, and 44.4% (4/9) of ectoparasite-pooled samples proved positive for filariae using nested-PCR targeting partial COI. The PCR positive samples were successfully sequenced, with a total of 27 unique sequences obtained. According to BLAST analysis, 34 samples were identified as Litomosa sp., with the closest match being sequences of Litomosa sp. isolated from V. murinus in our previous study Pikula et al. (10; 98.7–100% identity, OP796365-71, Czech Republic), while 17 samples showed highest similarity to the Eufilaria sylviae sequence isolated from Sylvia borin (86.9–87.1% identity, MT800770, Lithuania), and were named as Onchocercid sp., i.e., an unspecified species of the family Onchocercidae. While sequence homology in Litomosa sp. ranged from 98.6 to 99.9%, the Onchocercid sp. sequences showed even higher similarity, ranging from 99.5 to 99.9%. The remaining 24 samples were identified as mixed infections with both the above-mentioned species based on analysis of mixed chromatograms. This was supported by cloning of two samples that showed mixed chromatograms (one from bat tissue, one from an ectoparasite) producing clean chromatogram sequences for both species.

All unique nucleotide sequences of the COI gene produced in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers PQ042391-417, with numbers PQ042391, PQ042407 and PQ042408 for the Onchocercid sp. sequence, and numbers PQ042392, PQ042393, and PQ042409 for the Litomosa sp. being obtained from co-infected S. spinosus and V. murinus characterized by cloning and all others using nested-PCR.

Phylogenetic analysis of the COI of available Filaroidea sequences clearly showed that the sequences obtained in this study clustered with bat infecting genera of Litomosa and Litomosoides (data not shown). In the detailed phylogeny, the Litomosa sp. sequences formed a highly supported clade with Litomosa sp. from our previous study (10), while the sequences labeled as Onchocercidae sp. formed part of a cluster clade separate from Litomosa spp. and Litomosoides spp. composed of sequences from Litomosa westi and an unnamed Litomosoides sp. (Figure 1). As support for the branches for this species was not high, we could not place it in either Litomosa or Litomosoides.

3.2 Prevalence and distribution of filarial infection in Vespertilio murinus

Only four of the 27 vespertilionid bats tested (males n = 3, females n = 1; 14.8%) hosted adult filarial nematodes based on visual inspection during dissection. In total, we found 11 adult worms in the abdominal and thoracic (one case) cavities, ranging from one to four worms per bat. Five worms were tested (the rest being saved for future morphological analysis), and were genetically determined as Litomosa sp. (OP796365-71) with at least 99.6% identity. Two adult filarial worms were found within the uterine cavity of a mid-gestation pregnant female. Both uterine and fetal thoracic tissues tested positive by nested-PCR. None of the adult worms in this study were genetically identified as Onchocercid sp. All adult Litomosa sp. worms found in the body cavities of bats (n = 5) proved negative for presence of the bacterial symbiont Wolbachia.

Combined molecular screening for presence of microfilariae and adult nematodes revealed 85.2% of V. murinus as positive, with all bats with adult worms positive for the molecular presence of microfilariae. Prevalence of filarial larval infection was significantly higher than infection with adults (Difference test, p < 0.001). Molecular analysis of tissues revealed a prevalence of 81.5% (22/27) for Litomosa sp. and 51.9% (14/27) for Onchocercid sp., with Onchocercid sp. always present in bat bodies as a co-infection with Litomosa sp. (with one exception) at significantly lower prevalence (Difference test, p < 0.05).

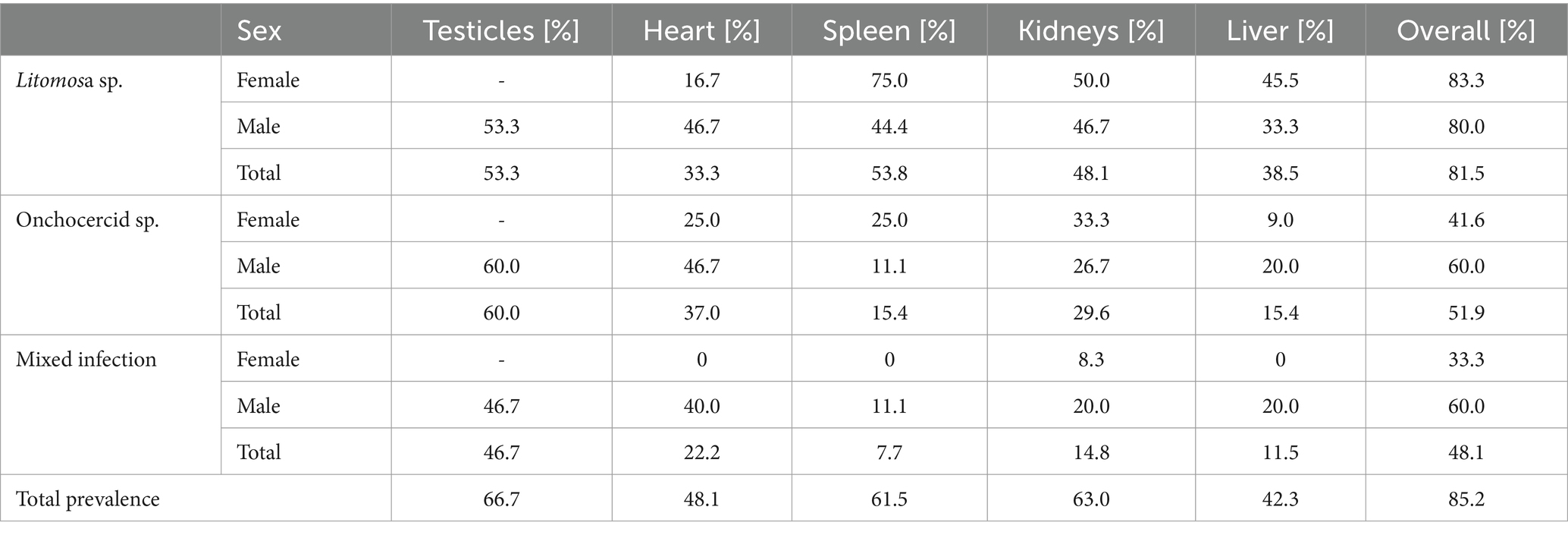

The difference in microfilarial infection prevalence between males (80.0%) and females (91.7%) was not significant (Difference test, p = 0.395), even when examining individual filarial species (Litomosa sp. p = 0.551, Onchocercid sp. p = 0.130). Tissue analysis indicated parasites distributed throughout the body, i.e., presence of circulating microfilariae of both species, whether individually or as a mixed infection, was confirmed in all tissue types (see Table 2), usually affecting multiple organs of each individual and in all possible combinations. There was no significant difference in the distribution of filarial species in the various organs (χ2 = 10.625, p = 0.101). In addition, we tested the presence of microfilariae in the testicles of males and found a prevalence of 66.7%.

Table 2. Prevalence of filarial infection in organs of Vespertilio murinus bats (females n = 12, males n = 15).

3.3 Identification of a potential vector mite

According to the nested-PCR analysis, microfilarial infection was limited to the ectoparasite S. spinosus, with four samples positive, the other pooled samples all proved negative. Three of the positive pooled samples harbored Onchocercid sp. DNA, and one showed mixed filarial infection. Molecular cloning of the latter sample confirmed simultaneous occurrence of both Litomosa sp. and Onchocercid sp. All positive pooled samples originated from Russia (Lukashino region, Western Siberia). Both negative pooled samples of I. obscurus were collected from the same bats as the two pooled samples of S. spinosus that proved positive for microfilariae.

4 Discussion

4.1 Filariae in Vespertilio murinus bats: sequencing, genetic diversity, and phylogenetic analysis

More than 20 species of Litomosa parasite have been described, seven of which have been recorded in European bats (though some have only been reported once), i.e., L. aelleni in Switzerland, L. vaucheri in Switzerland, L. dogieli in Europe, L. filaria in Europe, L. beshkovi in Bulgaria, L. ottavianii in Italy, and L. seurati in North Africa and southern France (21). However, these species have only been described morphologically, and molecular data on filarial nematodes of European bats remains scarce. Apart from the Litomosa sp. reported in our previous study (10), only one other Litomosa sequence has been reported from a European bat (MH411205; Hypsugo savii, Bulgaria). Our phylogenetic data revealed that the parasites recorded in our samples were closely related species and were unequivocally members of the genus Litomosa. The second species reported, here named Onchocercidae sp., formed part of a separate cluster, distinct from other Litomosa and Litomosoides spp., containing sequences of Litomosa westi (a parasite of Geomyid rodents in North America) (22) and an undescribed Litomosoides (KP728057, Pipistrellus cf. hesperidus, Madagascar). However, branch support was not high, and the cluster clearly changed position in different phylogenies (data not shown). Low bootstrap support, together with the absence of adult worms, did not allow us to firmly place the detected species within the filarial nematode taxonomy. Furthermore, the mentioned sequence of Litomosoides sp. (KP728057) was obtained from microfilariae, and no adult worms were ever found, meaning it could not be reliably assigned to Litomosoides spp. (5). Taken together, this suggests that there may be at least one other genus closely related to the genera Litomosa and Litomosoides. More molecular studies are needed to confirm possible new genera of bat-infecting filarial nematodes.

The distribution of V. murinus is quite extensive, ranging from Central Europe to Mongolia and Eastern Russia (23). Interestingly, while our necropsied bat samples originated from the Czech Republic and the S. spinosus mites positive for both detected parasites were collected in west Siberian Russia, we failed to detect any significant difference in relation to geographic origin of the sequences, with all samples clustering together in both parasites. This suggests that both parasites might be widespread and, consequently, their vector (or vectors) is also likely to be widespread (24). A similarly wide distribution range was also observed in Dirofilaria repens and D. immitis, filarial nematodes that affect dogs and other carnivores such as cats, wolves and foxes, where its distribution can be at least partially attributed to dog movements (25). Our study species, V. murinus, is a long-distance migrant capable of flying more than 1,500 kilometers southwest or southeast between its winter and summer roosts in regions with milder climates (26). Consequently, infectious agents can be spread via yet unknown vector between different locations over a wide geographic area. This species-specific aspect of the host bat species may also influence the parasite’s prevalence, with differing abilities of bat species to move between habitats resulting in greater or fewer encounters with each other and with blood-sucking vectors that may only be present in certain regions or habitats (27).

4.2 Prevalence and distribution of filarial infection in Vespertilio murinus

In filarioid nematodes, larvae released from females enter the host’s lymphatic system and blood vessels as microfilariae. At this point, they are ready to be ingested by an ectoparasitic vector, in which they develop into infective L3 larvae that can then infect a new host as it feeds on another bat. In the new host, they continue development into L4 larvae, migrating through the bat’s body to their definitive site of maturation and dwelling (28, 29). As the molecular detection method used in the present study is not able to distinguish different larval stages, tested organs and mites could theoretically be positive due to different filarial developmental stages. There also appears to be no single target organ providing higher probability of microfilarial detection in V. murinus. Instead, the overall prevalences documented (i.e., ~82% Litomosa sp., ~52% Onchocercid sp., ~48% mixed infection) suggest the common occurrence of these parasites throughout V. murinus. Discrepancies in infection prevalence based on presence of adult worms and/or molecular larval detection may result from the difficulty of finding the minute thread-like filarial nematodes during dissection, differences in infection stages between individual bats, and differences in survival of microfilarial and adult nematodes within the host body (30).

Findings of 11 Litomosa sp. worms in the present study agree with the previous knowledge that adult filarial worms are typical cavity dwelling nematodes of small mammals, including bats (21, 31–37). However, they may also be parasites of subcutaneous tissues (28).

Unfortunately, we were not able to find adult Onchocercid sp. worms in this study, and the site where to look for these parasites remains elusive. Nevertheless, careful techniques of microdissection and microscopic tissue squash and wet mount examination should be used during bat necropsies in the future. Interestingly, two adult Litomosa sp. worms were discovered inside the uterus of a pregnant V. murinus female, and fetal tissues were also positive for filarial DNA in this case, meaning that the Litomosa sp. microfilariae can pass through the uterine wall and placenta (38–40). High ectoparasite loads and abundant bat aggregations typical for bat nursery colonies (41) may further increase opportunities for vector-borne cycling based on bat offspring infected transplacentally, similar to canine puppies (42), possibly contributing to the observed high filariasis prevalence.

Based on our previous finding of microfilariae in the bat’s semen (10) suggesting polygynous mating of V. murinus as a possible route of microfilarial transmission of the Litomosa sp. nematode, we expected host-sex differences in the infection prevalence (43). Likewise, some other aspects such as the social behavior of host males segregating from females for most of the year and their territorial individual roosting could influence the risk of filarial infection (44). However, this prediction of host-sex-related differences was not confirmed. As shown in Table 2, testicular tissues were rather commonly positive (~67%) for single and mixed microfilarial infections by both parasite species detected in the present study. It remains unclear whether this transmission of microfilariae occurs and to what an extent, and whether it decreases semen quality and challenges the success of reproductive events in females after mating (10). An alternative route of pathogen transmission could be advantageous, for example, during the period of limited exposure to arthropods (45–47) which are an essential part of the life cycle of filarial nematodes (30).

Since filarial nematodes can contain Wolbachia endosymbionts, we investigated their presence in adult worms using PCR screening. Interestingly, Wolbachia was not detected in Litomosa sp., despite claims that it is essential for the biology of its filarial host e.g., (see Casiraghi et al.) (11) and it having been confirmed in other species of the genus, e.g., L. westi from rodents (12) and most species of Litomosoides parasitising bats or rodents (36). However, data obtained both in this study and in Madagascar (21) show that L. westi is phylogenetically different from other known Litomosa parasites; a feature also supported by the lack of Wolbachia endosymbionts in our bat-infecting parasite. Support for the loss of Wolbachia during filarial evolution is growing (36); for example, our own findings of absence are consistent with results for L. chiropterorum (36) and the single species Litomosoides yutajensis (12). A possible explanation may be secondary loss during evolutionary development in some filarial nematode species (1). In any case, distribution of Wolbachia within the Onchocercidae appears to be inconsistent, and even among closely related filarial nematodes, the picture remains complicated.

4.3 Identification of a potential vector mite

Very little is known about the filarial nematode life-cycle transmission phase in bats, and their invertebrate vectors are poorly understood (5). Bats host a wide variety of ectoparasites (45, 48), including those that we tested using molecular methods, i.e., fleas (Siphonaptera: Ischnopsyllidae), ticks (Ixodida: Argasidae: Carios), and mites of the genus Steatonyssus (Mesostigmata: Macronyssidae). In this study, we showed that only S. spinosus mites were positive for presence of microfilarial DNA. As fleas collected from the same individual tested negative, this suggests that S. spinosus may be a potential vector. This may be supported by previous suggestion that mites of the order Mesostigmata may be potential vectors of larval filariae stages (36), while macronyssid mites are thought to be a vector of Litomosoides in rodents, marsupials and bats (33, 49, 50). This hypothesis of transmission by macronyssid mites is also supported by experimental introduction of Ornithonyssus bacoti onto the microfilaraemic Parnell’s mustached bat (Pteronotus parnellii) (34) and the Jamaican fruit bat (Artibeus jamaicensis) (30). The most common ectoparasite of V. murinus, S. spinosus, is recorded throughout most of the species’ range (16, 51, 52) and is characterized by a high degree of adherence to the host and relatively strong host specificity (51). They parasitise their hosts in the summer roosts (47), with some species becoming permanent parasites (53). Moreover, a related Steatonyssus species, S. periblepharus, has recently been suggested as a novel potential vector of the bat parasite Trypanosoma dionisii (54). Interestingly, such wing membrane mites may also serve as vectors of some other infectious agents, such as the white-nose syndrome fungus (55). Nevertheless, the sole presence of DNA in S. spinosus does not prove that this ectoparasite serves as a vector of the detected parasites, and experimental studies are needed to assess its role in the epidemiology of bat infecting filarial nematodes.

5 Conclusion

We detected highly prevalent single and mixed infections with two filarial species in V. murinus. The first parasite, identified as Litomosa sp., has already been reported in our previous study (10), while the second could only be characterized as a species of the Onchocercidae family using molecular methods as adult worms were not discovered during necropsies of bat cadavers. Phylogenetic analysis of parasite COI sequences originating from bats sampled in the Czech Republic, and from S. spinosus mites collected on V. murinus in Russia, suggests extensive spatial distribution of both filarial species. As S. spinosus mites tested positive for microfilarial DNA of both parasitic worms, these mites may serve as vectors for these filarial infections. Our data strongly suggest that a taxonomic revision of bat-infecting filarial nematodes is needed.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in the GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) under accession numbers PQ042391-417.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because the research involved only cadavers of bats.

Author contributions

SB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. OD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HD: Writing – review & editing. MN: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. VP: Writing – review & editing. KZ: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported through Project IGA 224/2024/FVHE at the University of Veterinary Sciences Brno. The funder had no role in the study design, data analysis, the decision to publish or the preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kevin Roche for correction and improvement of the English text. Many thanks also go to Maria V. Orlova and Oleg L. Orlov (Tyumen State University, Russia) for help with sampling and morphological determination of ectoparasites.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2025.1546353/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1. Morales-Hojas, R. Molecular systematics of filarial parasites, with an emphasis on groups of medical and veterinary importance, and its relevance for epidemiology. Infect Genet Evol. (2009) 9:748–59. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.06.007

2. Cross, JH. Enteric nematodes of humans In: S Baron, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th ed. Galveston, TX: University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (1996)

3. Mäser, P. Filariae as organisms In: R Kaminsky and TG Geary, editors. Human and Animal Filariases. 1st ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley (2022). 17–32.

4. Evans, C, Pilotte, N, Williams, S, and Moorhead, A. Veterinary diagnosis of filarial infection In: R Kaminsky and TG Geary, editors. Human and Animal Filariases. 1st ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley (2022). 125–59.

5. Ramasindrazana, B, Dellagi, K, Lagadec, E, Randrianarivelojosia, M, Goodman, SM, and Tortosa, P. Diversity, host specialization, and geographic structure of filarial nematodes infecting Malagasy bats. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0145709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145709

6. Rendón-Franco, E, López-Díaz, O, Martínez-Hernández, F, Villalobos, G, Muñoz-García, CI, Aréchiga-Ceballos, N, et al. Litomosoides sp. (Filarioidea: Onchocercidae) infection in frugivorous bats (Artibeus spp.): pathological features, molecular evidence, and prevalence. TropicalMed. (2019) 4:77. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed4020077

7. Lagrange, E, and Bettini, S. Descrizione di una nuova filaria, Litomosa Ottavianii Lagrange e Bettini, 1948, parassita di pipistrelli. Riv Parassitol. (1948) 9:61–77.

8. Petit, G. On filariae of the genus Litomosa, parasites of bats. Bulletin du Muséum national d’Histoire Naturelle, a (Zoologie, Biologie et Écologie Animales) (1980) 2:365–74. doi: 10.5962/p.283844,

9. Horvat, Ž, Čabrilo, B, Paunovic, M, Karapandža, B, Josipovic, J, Budinski, I, et al. The helminth fauna of the greater horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) (Chiroptera: Rhinolophidae) on the territory of Serbia. Biologia Serbica. (2015) 37:64–7. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299918658_The_helminth_fauna_of_the_greater_horseshoe_bat_Rhinolophus_ferrumequinum_Chiroptera_Rhinolophidae_on_the_territory_of_Serbia

10. Pikula, J, Piacek, V, Bandouchova, H, Bartlova, M, Bednarikova, S, Burianova, R, et al. Case report: filarial infection of a parti-coloured bat: Litomosa sp. adult worms in abdominal cavity and microfilariae in bat semen. Front Vet Sci. (2023) 10:1284025. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2023.1284025

11. Casiraghi, M, McCall, JW, Simoncini, L, Kramer, LH, Sacchi, L, Genchi, C, et al. Tetracycline treatment and sex-ratio distortion: a role for Wolbachia in the moulting of filarial nematodes? Int J Parasitol. (2002) 32:1457–68. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00158-3

12. Casiraghi, M, Bain, O, Guerrero, R, Martin, C, Pocacqua, V, Gardner, SL, et al. Mapping the presence of Wolbachia pipientis on the phylogeny of filarial nematodes: evidence for symbiont loss during evolution. Int J Parasitol. (2004) 34:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.10.004

13. Orlova, MV, Orlov, OL, Kazakov, DV, and Zhigalin, AV. Approaches to the identification of ectoparasite complexes of bats (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae, Miniopteridae, Rhinolophidae, Molossidae) in the Palaearctic. Entmol Rev. (2017) 97:684–701. doi: 10.1134/S001387381705013X

14. Beĭ-Bienko, GIA, Bykhovskiĭ, BE, and Medvedev, GS. Zoologicheskii institut (Akademiia nauk SSSR). Keys to the insects of the European part of the USSR: Diptera and Siphonaptera, vol. 2. Leningrad: Nauka (1970).

15. Estrada-Peña, A, Mihalca, AD, and Petney, TN. Ticks of Europe and North Africa. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2017).

16. Orlova, M, Stanyukovich, M, and Orlov, O. Gamasid mites (Mesostigmata: Gamasina) parasitizing bats (Chiroptera: Rhinolophidae, Vespertilionidae, Molossidae) of Palaearctic boreal zone (Russia and adjacent countries) (2015).

17. Nguyen, LT, Schmidt, HA, Von Haeseler, A, and Minh, BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. (2015) 32:268–74. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300

18. Kalyaanamoorthy, S, Minh, BQ, Wong, TKF, Von Haeseler, A, and Jermiin, LS. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods. (2017) 14:587–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285

19. Minh, BQ, Nguyen, MAT, and Von Haeseler, A. Ultrafast approximation for phylogenetic bootstrap. Mol Biol Evol. (2013) 30:1188–95. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst024

20. Guindon, S, and Gascuel, O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. (2003) 52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520

21. Martin, C, Bain, O, Jouvenet, N, Raharimanga, V, Robert, V, and Rousset, D. First report of Litomosa spp. (Nematoda: Filarioidea) from Malagasy bats; review of the genus and relationships between species. Parasite. (2006) 13:3–10. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2006131003

22. Jiménez, FA, Notarnicola, J, and Gardner, SL. Host-switching events in Litomosoides Chandler, 1931 (Filarioidea: Onchocercidae) are not rampant but clade dependent. J Parasitol. (2021) 107:320–35. doi: 10.1645/20-35

23. Brabant, R, Laurent, Y, Lafontaine, RM, Vandendriessche, B, and Degraer, S. First offshore observation of parti-coloured bat Vespertilio murinus in the Belgian part of the North Sea. Belgian J Zool. (2020) 146:40. doi: 10.26496/bjz.2016.40

24. Orlova, MV, and Orlov, OL. Attempt to define the complexes of bat Ectoparasites in the boreal Palaearctic region/Попытка выделения комплексов эктопаразитов летучих мышей бореальной Палеарктики. Vestnik Zoologii. (2015) 49:75–86. doi: 10.1515/vzoo-2015-0008

25. Genchi, C, and Kramer, L. Subcutaneous dirofilariosis (Dirofilaria repens): an infection spreading throughout the old world. Parasites Vectors. (2017) 10:517. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2434-8

26. Hutterer, R, Ivanova, T, Meyer-Cords, CH, and Rodrigues, L. Bat migration in Europe. A review of banding data and literature. Bonn: Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (2005).

27. Avila-Flores, R, and Fenton, MB. Use of spatial features by foraging insectivorous bats in a large urban landscape. J Mammal. (2005) 86:1193–204. doi: 10.1644/04-MAMM-A-085R1.1

28. Bouchery, T, Lefoulon, E, Karadjian, G, Nieguitsila, A, and Martin, C. The symbiotic role of Wolbachia in Onchocercidae and its impact on filariasis. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2013) 19:131–40. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12069

29. Hoffmann, W, Petit, G, Schulz-Key, H, Taylor, D, Bain, O, and Le Goff, L. Litomosoides sigmodontis in mice: reappraisal of an old model for filarial research. Parasitol Today. (2000) 16:387–9. doi: 10.1016/S0169-4758(00)01738-5

30. Bain, O, Babayan, S, Gomes, J, Rojas, G, and Guerrero, R. First account on the larval biology of a Litomosoides filaria, from a bat. Parassitologia. (2002) 5:89–92. doi: 10.1007/0-306-47661-4_3

31. Brant, SV, and Gardner, SL. Phylogeny of species of the genus Litomosoides (Nematoda: Onchocercidae): evidence of rampant host switching. J Parasitol. (2000) 86:545–54. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0545:POSOTG]2.0.CO;2

32. Conga, DF, Araújo, CY, Souza, NF, Corrêa, JT, Santos, JB, Figueiredo, EC, et al. Cerebral filariasis infection with Litomosoides in Molossus barnesi (Chiroptera: Molossidae) in the Brazilian eastern Amazon, with comments on Molossinema wimsatti Georgi, Georgi, Jiang and Fronguillo, 1987. Parasitol Res. (2024) 123:125. doi: 10.1007/s00436-024-08139-8

33. Guerrero, R, Martin, C, Gardner, SL, and Bain, O. New and known species of Litomosoides (Nematoda: Filarioidea): important adult and larval characters and taxonomic changes. Comp Parasitol. (2002) 69:177–95. doi: 10.1654/1525-2647(2002)069[0177:NAKSOL]2.0.CO;2

34. Guerrero, R, Martin, C, and Bain, O. Litomosoides yutajensis n. sp., first record of this filarial genus in a mormoopid bat. Parasite. (2003) 10:219–25. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2003103219

35. Gupta, SP, and Trivedi, KK. Nematode parasites of vertebrates. On two new species of the genus Litomosoides chandler 1931 (family: Dipetalonematidae Wehr, 1935) from microbats of Udaipur Rajasthan, India. Riv Parassitol. (1989)

36. Junker, K, Barbuto, M, Casiraghi, M, Martin, C, Uni, S, Boomker, J, et al. Litomosa chiropterorum Ortlepp, 1932 (Nematoda: Filarioidea) from a south African miniopterid: redescription, Wolbachia screening and phylogenetic relationships with Litomosoides. Parasite. (2009) 16:43–50. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2009161043

37. Notarnicola, J, Ruíz, FAJ, and Gardner, SL. Litomosoides (Nemata: Filarioidea) of bats from Bolivia with Records for Three Known Species and the description of a new species. J Parasitol. (2010) 96:775–82. doi: 10.1645/GE-2371.1

38. Anosike, JC, Onwuliri, COE, and Abanobi, OC. Suspected case of transplacental transmission of Wuchereria bancrofti microfilariae. Med J Indones. (1994) 16:16. doi: 10.13181/mji.v3i1.936

39. Eberhard, ML, Hitch, WL, McNeeley, DF, and Lammie, PJ. Transplacental transmission of Wuchereria bancrofti in Haitian women. J Parasitol. (1993) 79:62–6. doi: 10.2307/3283278

40. Haque, A, and Capron, A. Transplacental transfer of rodent microfilariae induces antigen-specific tolerance in rats. Nature. (1982) 299:361–3. doi: 10.1038/299361a0

41. Zahn, A, and Rupp, D. Ectoparasite load in European vespertilionid bats. J Zool. (2004) 262:383–91. doi: 10.1017/S0952836903004722

42. Todd, KS, and Howland, TP. Transplacental transmission of Dirofilaria immitis microfilariae in the dog. J Parasitol. (1983) 69:371. doi: 10.2307/3281237

44. Wilson, DE, and Mittermeier, R. Bats. Handbook of the mammals of the world. 9th ed. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions (2019). 1008 p.

46. Haitlinger, R. Pasożyty zewnętrzne nietoperzy Dolnego Śląska. IV. Macronyssidae, Dermanyssidae, Veigaiaidae (Acarina). [external parasites of bats of lower Silesia. IV. Macronyssidae, Dermanyssidae, Veigaiaidae (Acarina)]. Wiad Parazytol. (1978) 24:707–18.

47. Rybin, SN. Гамазоидные клещи рукокрылых и их убежищ в южной Киргизии [Gamasoid mites of bats and their roosts in southern Kirghizstan]. Parasitologiâ. (1983) 17:355–60.

48. Ivanova-Aleksandrova, N, Dundarova, H, Neov, B, Emilova, R, Georgieva, I, Antova, R, et al. Ectoparasites of cave-dwelling bat species in Bulgaria. Proc Zool Soc. (2022) 75:463–8. doi: 10.1007/s12595-022-00451-4

49. Bain, O. Evolutionary relationships among filarial nematodes. The Filaria In: World class parasites, vol. 5. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers (2002). 21–9.

50. Costa, TF, Coutinho, DJB, Simas, AKSM, Santos, GVD, Nogueira, RDMS, Costa, FB, et al. Litomosoides brasiliensis (Nematoda: Onchocercidae) infecting chiropterans in the legal Amazon region, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. (2022) 31:e011722. doi: 10.1590/s1984-29612022059

51. Orlova, MV. Ectoparasites of the particolored bat (Vespertilio murinus Linnaeus, 1758, Chiroptera, Mammalia) in the Urals and adjacent regions. Entmol Rev. (2013) 93:1236–42. doi: 10.1134/S0013873813090169

52. Orlova, MV, Kazakov, DV, Orlov, OL, Mishchenko, VA, and Zhigalin, AV. The first data on the infestation of the parti-coloured bat, Vespertilio murinus (Chiroptera, Vespertilionidae), with gamasid mites, Steatonyssus spinosus (Mesostigmata, Gamasina, Macronyssidae). Rus J Theriol. (2017) 16:66–73. doi: 10.15298/rusjtheriol.16.1.06

54. Malysheva, MN, Ganyukova, AI, Frolov, AO, Chistyakov, DV, and Kostygov, AY. The mite Steatonyssus periblepharus is a novel potential vector of the bat parasite Trypanosoma dionisii. Microorganisms. (2023) 11:2906. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11122906

55. Lučan, RK, Bandouchova, H, Bartonička, T, Pikula, J, Zahradníková, A, Zukal, J, et al. Ectoparasites may serve as vectors for the white-nose syndrome fungus. Parasites Vectors. (2016) 9:16. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1302-2

56. Casiraghi, M, Anderson, TJC, Bandi, C, Bazzocchi, C, and Genchi, C. A phylogenetic analysis of filarial nematodes: comparison with the phylogeny of Wolbachia endosymbionts. Parasitology. (2001) 122:93–103. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000007149

Keywords: Vespertilio murinus, onchocercid filarial nematode, Litomosa, vector-borne parasites, Steatonyssus spinosus mite, Wolbachia

Citation: Bednarikova S, Danek O, Dundarova H, Nemcova M, Piacek V, Zukalova K, Zukal J and Pikula J (2025) Filariasis of parti-colored bats: phylogenetic analysis, infection prevalence, and possible vector mite identification. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1546353. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1546353

Edited by:

Vikrant Sudan, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, IndiaReviewed by:

Jana Kvicerova, University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice, CzechiaMartin Ševčík, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Slovakia

Copyright © 2025 Bednarikova, Danek, Dundarova, Nemcova, Piacek, Zukalova, Zukal and Pikula. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ondrej Danek, ZGFuZWtvQGFmLmN6dS5jeg==; Jiri Pikula, cGlrdWxhakB2ZnUuY3o=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Sarka Bednarikova

Sarka Bednarikova Ondrej Danek

Ondrej Danek Heliana Dundarova3

Heliana Dundarova3 Jan Zukal

Jan Zukal Jiri Pikula

Jiri Pikula