- 1Department of Applied Animal Science and Welfare, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Umeå, Sweden

- 2Institute of Biotechnology, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- 3Arid Land Research Center, Tottori University, Tottori, Japan

- 4Shikoku Center, Japan International Cooperation Agency, Tokyo, Japan

This study continued the in vitro screening of locally available ruminant feedstuffs for optimum nutrient composition and low methane (CH4) production in Ethiopia. The best bet feeds from the in vitro study, hereafter called the test feeds, include dried leaves of Acacia nilotica, Ziziphus spina-christi, and brewery spent grains (BSG). The study involves four treatments: Control, Acacia, BSG, and Ziziphus; each treatment provided an equivalent crude protein and estimated enteric CH4 emissions using Modeling and a Laser CH4 detector (LMD). The experiment was designed as a randomized complete block, using initial weight as the blocking factor for 21 yearling castrated Menz sheep. The study spanned 90 days, and digestibility trials were carried out following a month of the feeding trial. The control group exhibited a significantly (p < 0.001) lower dry matter intake (DMI) compared to the test feed group, which had a higher intake, particularly in the Ziziphus group. However, the Ziziphus group demonstrated significantly (p < 0.01) lower CP digestibility than the other groups. The test diet also led to a significantly (p < 0.001) higher weight gain. Notably, the Ziziphus group demonstrated superior performance in weight change (BWC), final body weight (FBW), and average daily gain (ADG). Similar results were observed for CH4 production (g/day), CH4 yield (g/kg DMI), and CH4 intensity (g CH4/kg ADG) using both CH4 measuring methods. The CH4 emission intensity was significantly (p < 0.04) lower in the test feed groups than in the control group. The control group emitted 808.7 and 825.3 g of CH4, while the Ziziphus group emitted 220 and 265.3 g of CH4 per kg of ADG using the Modeling and LMD methods, respectively. This study indicates that LMD could yield biologically plausible data for sheep. Although the small sample size in the Ziziphus group was a limitation of this study, leaf meals from Ziziphus spina-christi and Acacia nilotica, which are rich in condensed tannins (CTs), have resulted in considerable weight gain and enhanced feed efficiency, thereby making these leaf meals a viable and sustainable feed option for ruminants in Ethiopia.

1 Introduction

In Ethiopian farm households, financial income from sheep and goat production constitutes 40%, which also equates to 19% of the subsistence food value from all livestock production and 25% of the country’s domestic meat consumption (1, 2). Small ruminants also contribute about 2% of the national gross domestic product (GDP) (3). Ethiopia claims an estimated 38 million sheep, 99.6% of which are indigenous breeds. The country also supports 14 traditional sheep-breeding communities (4, 5).

The scenario of sheep production in Ethiopia relies on low input systems such as poor quality and quantity of feed resources, lack of appropriate feeding system, poor production and reproduction traits, and low productive and reproductive performance. This low-productivity production system uses more energy to produce each unit of animal product than those with high-productivity. The low-input system is responsible for the bulk of CH4 emissions (6). Based on CSA (4) report, grazing is the primary type of feeding (57.8%), followed by crop residue (29.8%). Hay and by-products comprise about (6.7%) and (1.5%) of the total feeds, with the remaining (4.2%) other feed types, such as improved forage.

Ruminants that consume low-quality feed are known to produce more CH4 per unit of product compared to those on higher-quality diets (7). As a result, animal nutritionists are urged to investigate alternative feed resources that can be integrated with existing dietary components to lessen CH4 emissions while maintaining productivity (8). Enhanced feeding could significantly improve ruminants’ digestive efficiency and lower CH4 emissions by as much as 50% per unit of feed intake (9). In Ethiopia, some of the top feed sources with low CH4 yields include Acacia nilotica (L.) (6.6 g/kg DM), Ziziphus spina-christi (7.8 g/kg DM), and BSG (8.1 g/kg DM) (10).

This study sets out to assess locally available feed that improves the feeding value of the existing feed resource, increases or maintains animal productivity, and reduces CH4 intensity (i.e., g CH4/kg product) in the local Menz sheep breed in Ethiopia.

The selection criteria for test feeds in this trial were based on the in vitro output, focusing on low CH4 yield and optimal nutritional content from feed sources available locally in Ethiopia (10). Therefore, the study’s objective was to evaluate the effects of best-bet feeds on enteric CH4 emissions, weight gain, digestibility, and methane emission in local Menz sheep breeds. This research supports the country’s goal of adopting climate-smart agriculture within the livestock sector (11).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

The experiment was conducted at Debre Berhan Agricultural Research Center (DBARC). The experiment site is located in the central Highlands of Ethiopia about 120 km northeast of Addis Ababa, at an altitude of 2,800 m above sea level. The geographical location of DBARC is from 09°35′ 45″ to 09° 36′ 45″ north latitude and 39° 29′ 40″ to 39°31′ 30″ east longitude.

2.2 Experimental animals and management

Twenty-one yearling Menz sheep with a mean initial live body weight of 22.7 ± 1.7 kg (mean ± SD) were purchased from a nearby local livestock market. All sheep purchased were Burdizzo castrated and vaccinated for pasteurellosis, sheep pox, and anthrax during a 15-day quarantine period. In addition, both internal and external parasites were treated with ivermectin.

2.3 Experimental feed preparation and feeding

The three test feeds in this experiment include BSG, dried leaves of Acacia nilotica, and Ziziphus spina-Christi.

Acacia nilotica and Ziziphus spina-christi leaves were harvested from Debre Berhan University research site and farmers’ trees in Showarobit. The branches were pruned and placed on a canvas to sun dry. Afterward, the leaves were removed by gently striking the branches with sticks. The BSG was obtained from Dashen Brewery factory and sun-dried on a canvas floor. The bulk of the dried foliage and BSG were stored in jute bags for subsequent feeding experiments. The other feed ingredients used for the experiment were Wheat bran (WB), Niger seed cake (NG), and salt lick. Control diet constituted only WB and NG. Supplements were divided into two halves and provided at 8:30 h and 14:00 h. Additionally, grass hay, dominated by Andropogon amethystinus Steud hay, was chopped manually and fed ad libtum along with salt lick as a basal diet to all animals. Water was available freely, daily feed offered, and refusals were recorded.

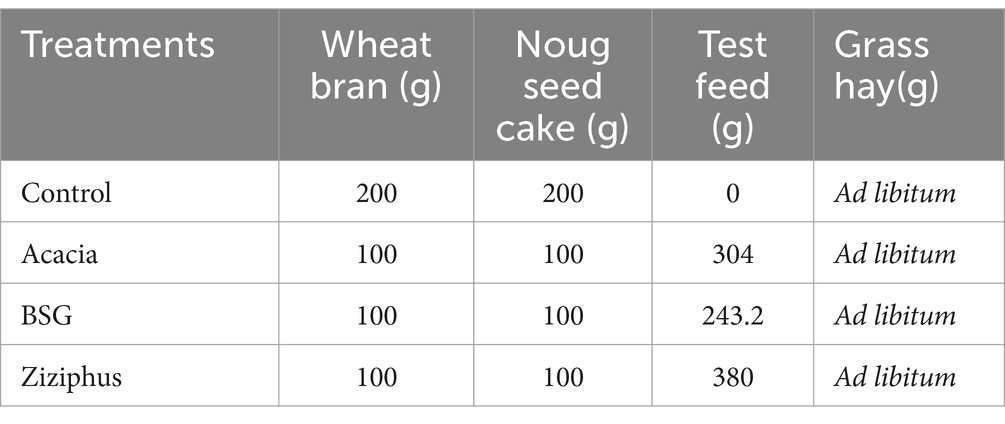

2.4 Experimental treatments and design

The treatment feeds were calibrated such that the test feeds contained equivalent amounts of crude protein to the control diet. The feeding experiment was conducted using a randomized complete block design for 90 days. Six animals were assigned to each treatment, except for the Ziziphus group, which had only three animals due to a shortage of Ziziphus spina-christi at the time of the experiment. A possible limitation of the study is that only three sheep were used for the Ziziphus group, and one animal from the BSG group had to be dropped due to a sudden unexplained drop in intake.

2.5 Data collection

2.5.1 Feed intake measurement

The diet offered, and orts were recorded daily for each animal to measure DMI. Representative samples of feed offered per batch and refused per animal were collected every 3 days to determine dry matter.

2.5.2 Live weight measurement

Initial body weight was measured by taking the mean of two consecutive weights after overnight fasting before the beginning of the actual feeding trial and every 15 days thereafter using hanging digital balance with 10 g graduation.

2.5.3 Apparent digestibility trial

At 31 days of the feeding trial, animals were fitted with fecal collection bags for digestibility study for 10 consecutive days, where the first 3 days were used as adaptation and the remaining 7 days as sampling. All the daily fecal outputs were collected, weighed, and recorded for each animal, and a sub-sample of approximately 100 g was taken from each animal after thorough mixing and stored at - 20°C. The frozen daily fecal output was thawed, pooled for the sampling days per animal and treatment, and dried at 65°C for 72 h. Dried samples were ground to pass through a 1 mm sieve and stored in a plastic bag for chemical analysis.

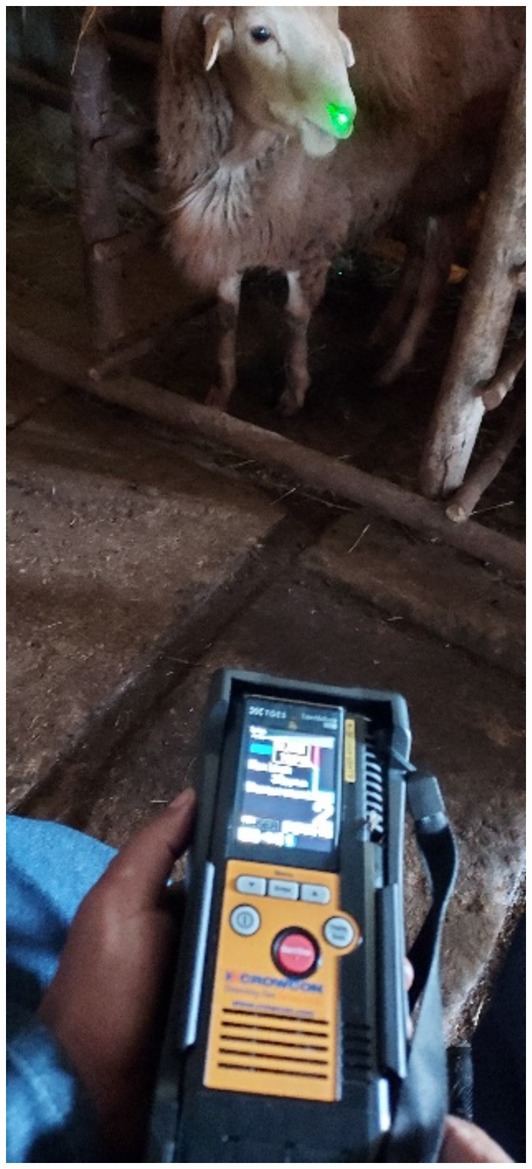

2.6 Enteric CH4 measurements

In the final week of the experiment, a portable laser CH4 detector LMD (Crowcon Detection Instruments Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), was utilized for three consecutive days before and after the morning and evening feedings. The concentration of CH4 was measured by directing a green laser beam toward the nostrils of the sheep for 3 continuous minutes to estimate the CH4 concentration at 1 m from the resting animal in their feeding pen (Figure 1). The LMD was linked to a tablet with the GasViewer app through Bluetooth for data export and storage. The LMD’s output is a time series of CH4 emission values from a single animal, encompassing both eructation and respiration, indicative of the respiratory cycle. The nonlinear generalized reduced gradient (nonlinear GRG) method in Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) was employed for calculating eructation and respiration, as documented by Kobayashi et al. (12). The CH4 levels, recorded in parts per million (ppm), were then converted to grams per day using a formula adapted from Lanzoni et al. (13), specifically tailored for sheep.

Where, V represents the tidal volume (which is 12 mL/kg body weight); R denotes the respiratory rate (resting respiratory rate of sheep ranges from 16 to 34 breaths per minute according to Reece et al. (14), and an average of 25/min is used); α is the conversion factor for (CH4 0.000667 g/mL); and, β denotes factor representing the dilution correction, (which accounts for the discrepancy between breath and total methane production in sheep and typically assumed to range from 5 to 8, with an average value of 6.5 being adopted). The value 1,440 represents the number of minutes per day. The CH4 average utilized in this study represents the mean of peaks and troughs, aiding in capturing each respiratory cycle (15). In addition, the current dilution factor assumed the difference in tidal volume, CH4 production, and respiratory rate between sheep and large ruminants.

In addition, enteric CH4 emissions were estimated using a model developed from an intercontinental database (16). Using the following formula:

Where DMI denotes dry matter intake, OMD denotes organic matter digestibility, and BW denotes body weight.

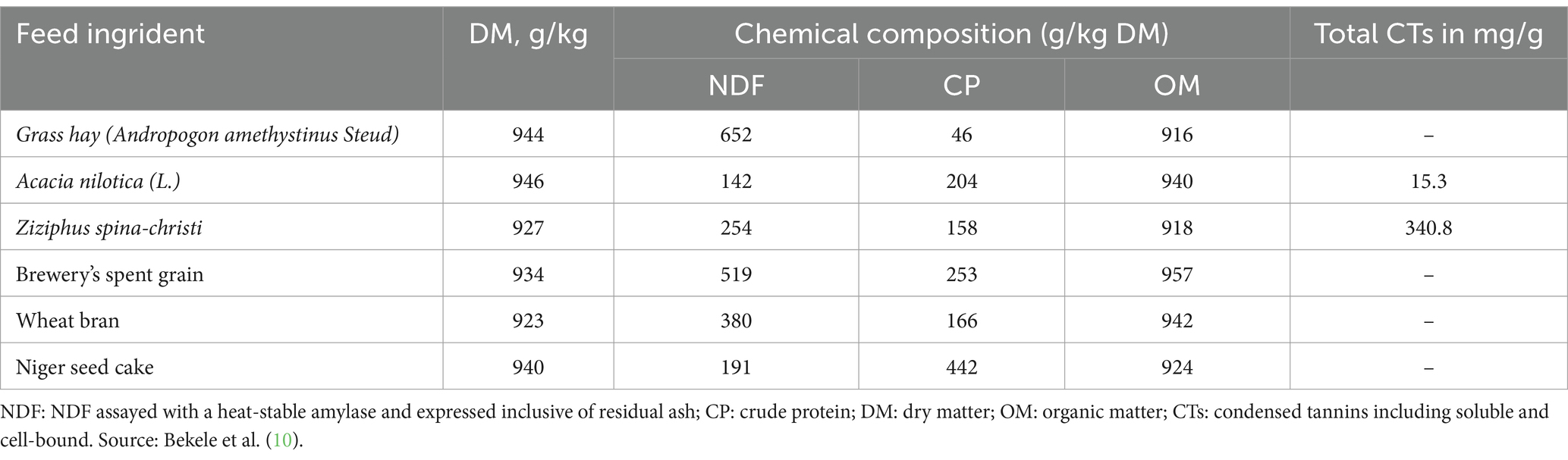

2.7 Chemical analysis

The chemical composition of the feed ingredients is presented in (Table 1) and the proportion of the treatment feed ingredients (Table 2). A detailed procedure, including in vitro CH4 yield and condensed tannin content (CTs), of the test feed can be found in Bekele et al. (10).

2.8 Calculations for derived values

Daily feed intake (g/d) of both supplement and basal feeds was determined by the difference between the amount of feed offered and its constituents (OM, CP, NDF) and refusal on a dry matter basis.

The average daily live weight gain (ADG, g/d) was calculated by subtracting initial weight from final weight and dividing by the days of feeding.

Apparent total tract digestibility coefficients of feed DM and its nutrients were calculated from the ingested and excreted amounts in the feces of each component.

Additionally, calculations were performed to derive data for protein efficiency ratio (PER) and CH4 emission intensity from the literature that did not provide direct values.

2.9 Data analysis

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) for data on feed intake, body weight change (BWC), and digestibility was conducted using R version 4.3.0 (17). Initial body weight (IBW) served as a covariate in the statistical analysis of ADG, BWC, and final body weight (FBW). This was performed using the ‘lm’ function with the following model:

Where

Yij is an observed variable for the ith treatment, jth block. μ is the overall mean, Ti is ith treatment, Bj is jth block, and eij is the residual error for the ith treatment and jth block. The results were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. Duncan’s Multiple Range Test method was employed for post hoc analysis. Simple linear regression analysis was also performed using the “ggscatter” function from the “ggpubr” package.

3 Results

3.1 Feed intake and apparent digestibility

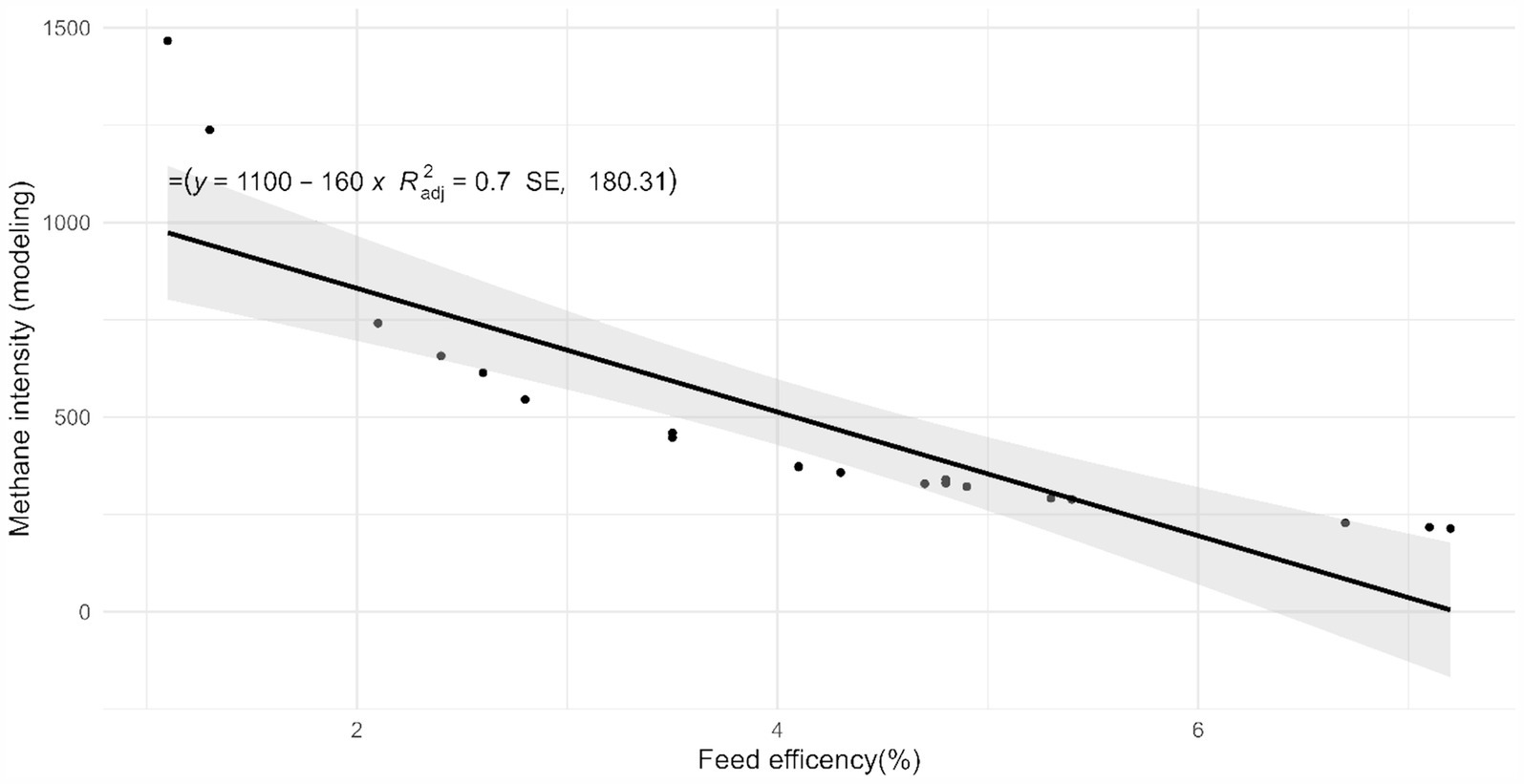

The Ziziphus group demonstrated significantly (p < 0.001) higher DM and OM intake than others, while the BSG group showed the highest NDF intake. Additionally, the Ziziphus group exhibited the lowest CP digestibility (Table 3).

Table 3. Dry matter, nutrient intake (g) and digestibility coefficient of Menz sheep fed natural pasture hay as a basal diet and supplemented with control and test feed.

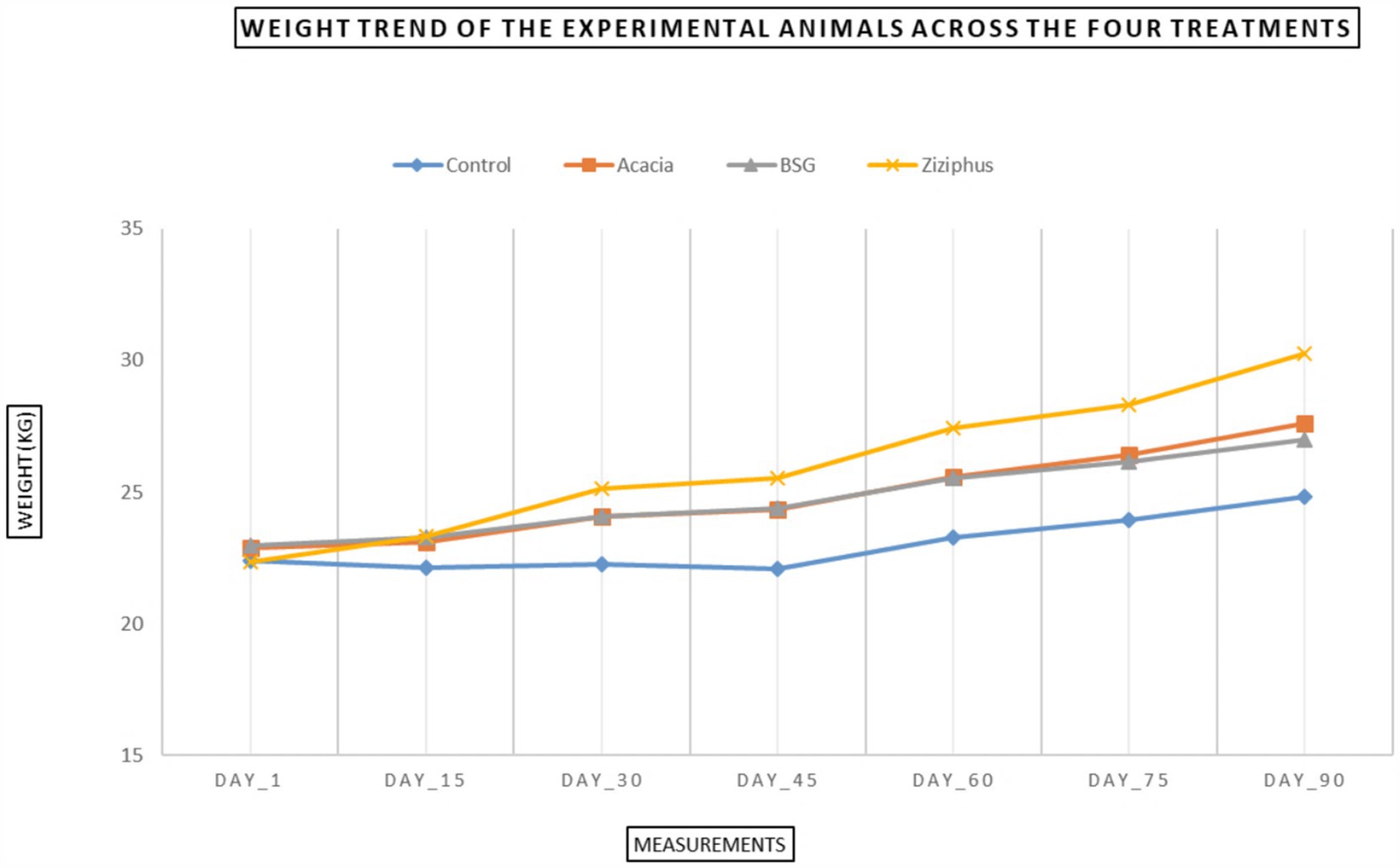

3.2 Body weight change

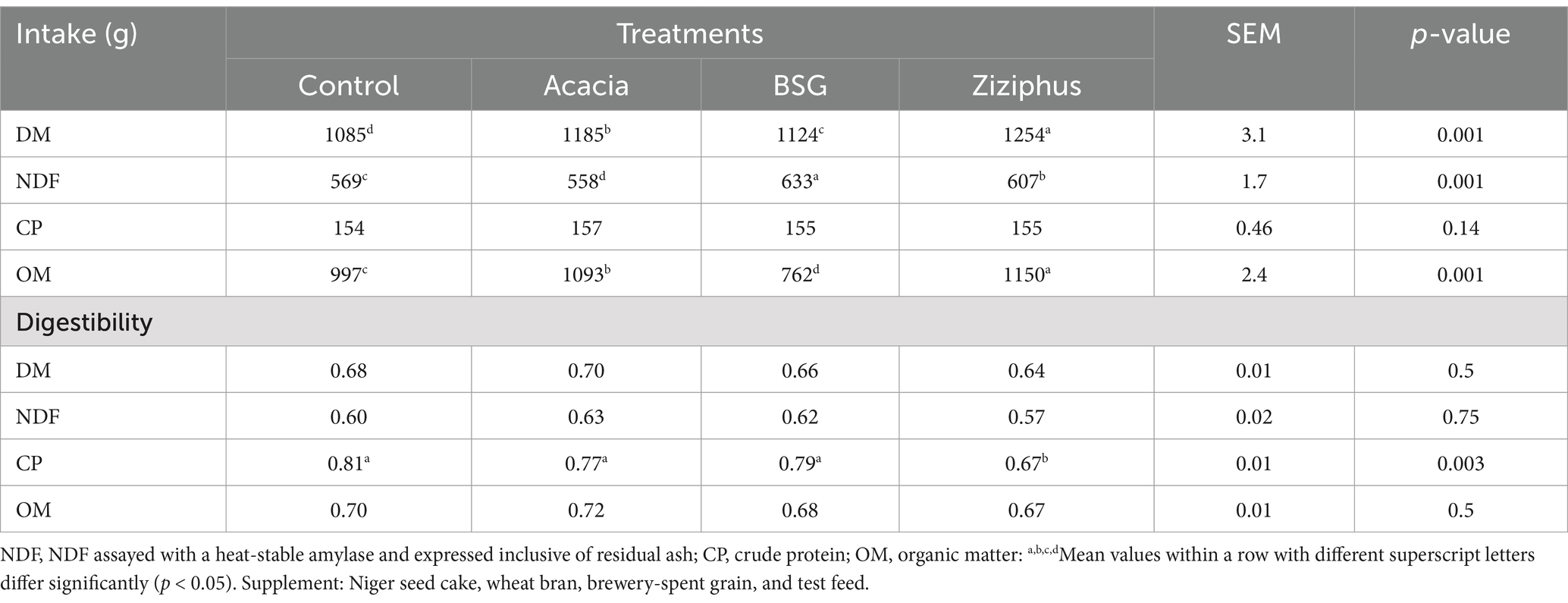

The test diet groups resulted in significantly more ADG than the control group (Table 4). Among the treatments, the Ziziphus group showed significantly (p < 0.001) the highest ADG, FE, and PER. Additionally, sheep fed with dried leaves (Ziziphus and Acacia groups) had significantly higher ADG than those solely on agro-industrial by-products (BSG and Control groups), as shown by the weight trend in Figure 2.

Table 4. Body weight change, feed efficiency and protein efficiency ratio of Menz sheep fed natural pasture hay as basal diet and supplemented with control and test feed.

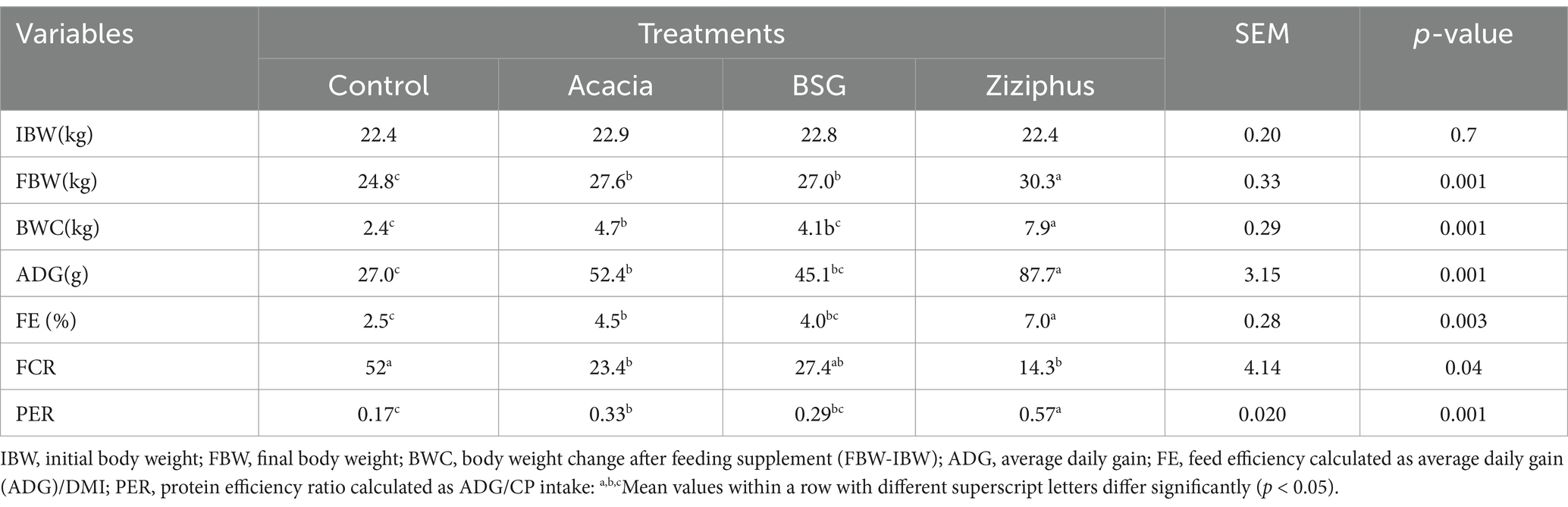

3.3 Enteric CH4 emission

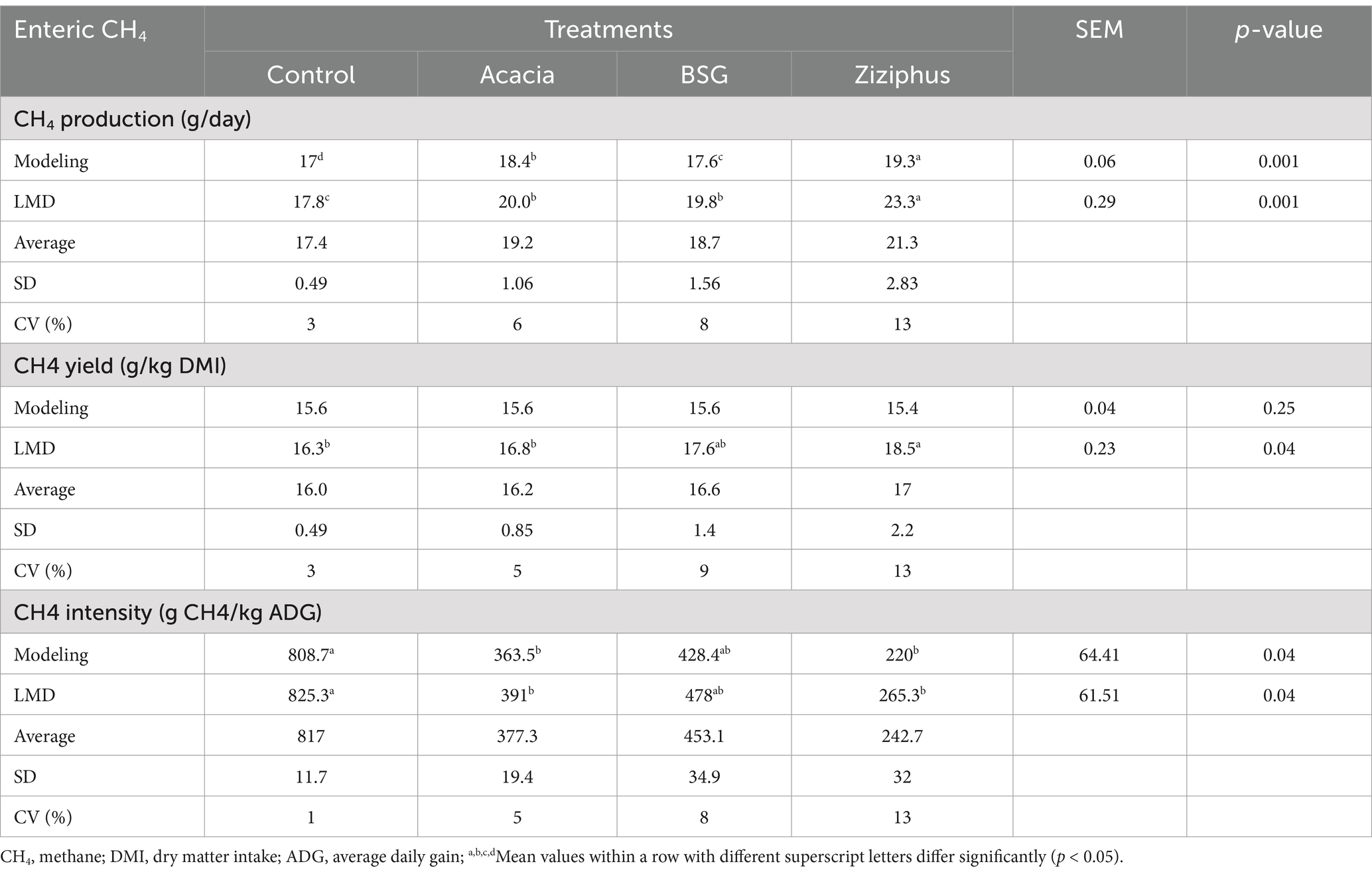

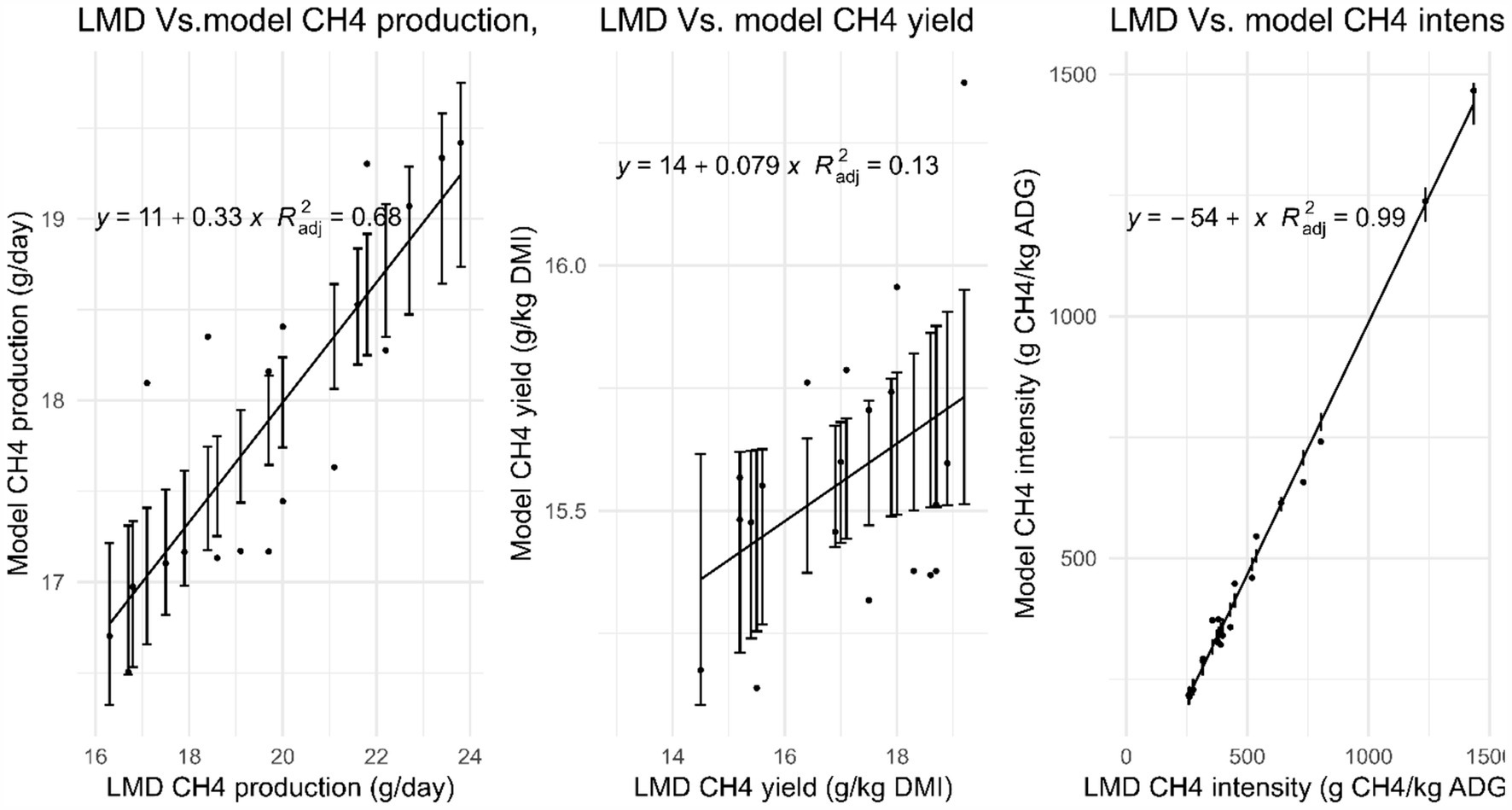

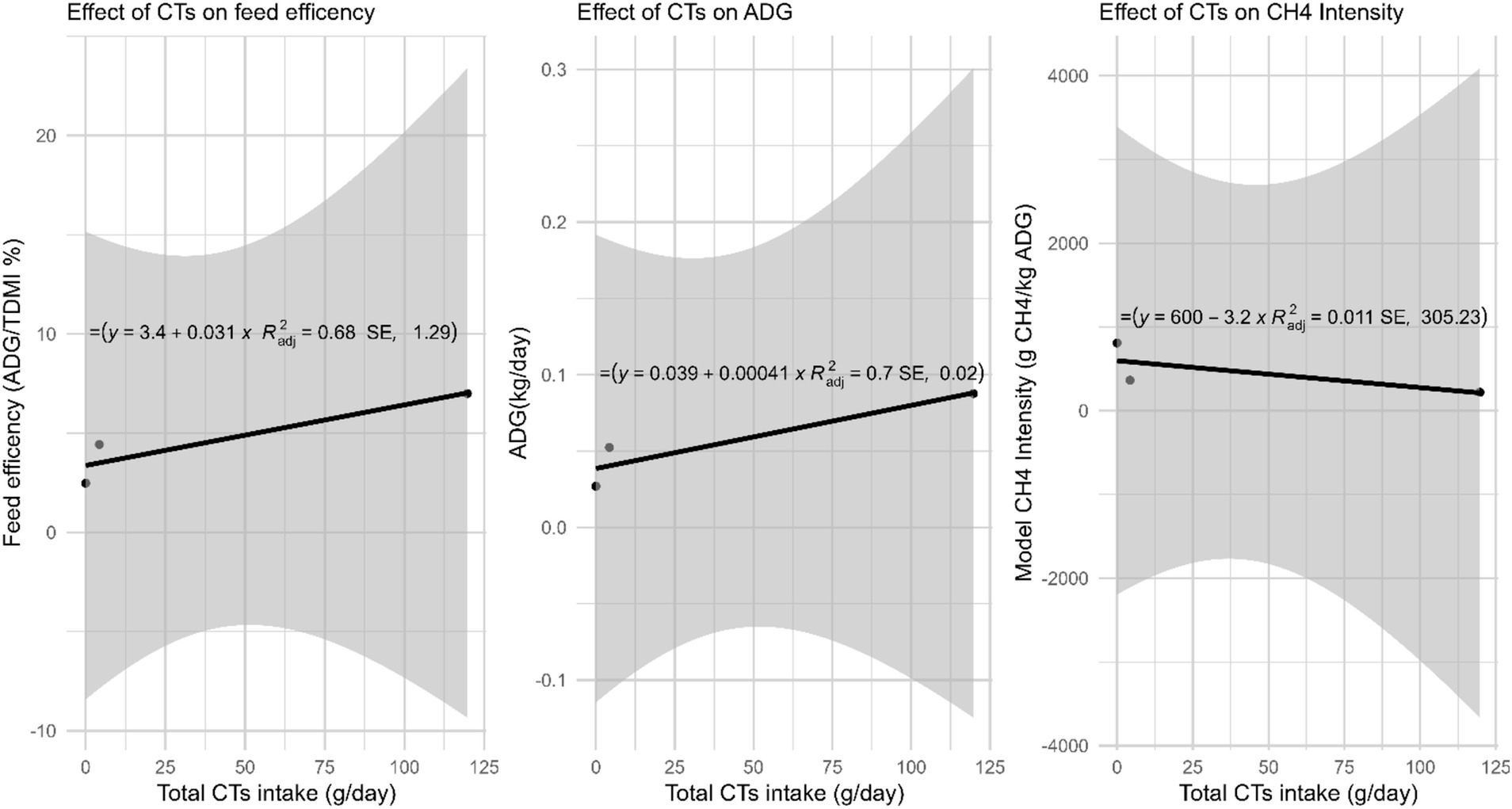

Table 5 presents the estimated enteric CH4 emissions derived from modeling and LMD methods. The Ziziphus group recorded the highest CH4 production yet the lowest CH4 intensity among all treatment groups. Conversely, the control group had the lowest CH4 production but the highest CH4 intensity according to both methods. The results from the LMD and modeling were consistent across treatments, showing a strong correlation between CH4 production and intensity, as evidenced by high (R2adj = 0.68–0.99), as depicted in Figure 3. This study found that feed efficiency (FE) significantly influenced CH4 intensity, and the effect of FE on CH4 intensity was greater than that of CT intake. The optimal R2adj value for FE was 0.70 (Figure 4), whereas the R2adj for total CT intake was only 0.011 (Figure 5).

Table 5. Enteric CH4 production, yield, and intensity of Menz sheep fed natural pasture hay as basal diet and supplemented with control and test feed using modeling and laser CH4 detector methods.

Figure 3. Relationship between enteric CH4 emissions measured by LMD Vs. Modeling from local Menz sheep breed in Ethiopia.

Figure 5. The effect of CTs intake on feed efficiency, average daily gain and CH4 intensity of Menz Sheep (Average of FE, ADG and CH4 intensity from modelling and total CTs values were used from Control, Acacia and Ziziphus group to construct the scatter plot).

Figure 5 illustrates the impact of CTs on FE, ADG, and CH4 intensity. An incremental increase in total CT intake correlates with a 0.031% increase in FE and a 0.41 g/d rise in ADG. Moreover, CH4 intensity is reduced by 3.2 grams per day.

4 Discussion

In this in vivo study, we employed modeling and LMD methods to estimate enteric CH4 emissions. Furthermore, the trial results indicated that CT intake affects ADG, FE, and CH4 emissions. In addition, FE had a notable effect on weight gain and CH4 intensity.

4.1 Feed intake and apparent digestibility

The experimental diet, designed to be iso-nitrogenous, led to a notably higher consumption of Ziziphus spina-christi dried leaves in the Ziziphus group. Consequently, this group showed a significantly (p < 0.001) greater supplement and total DMI. This is attributed to the bulkiness of Ziziphus spina-christi compared to the other treatment groups.

The research indicated that there were no significant differences (p > 0.05) in the intake of crude protein (CP) among the treatment groups, and the average daily consumption of CP met the satisfactory levels as defined by Kearl (18) and NRC (19). Nevertheless, OM, FE, and PER were significantly (p < 0.001) higher in the Ziziphus group compared to other treatments. The protein efficiency ratio in this study ranged from 0.18 to 0.57, which is lower than the ratios found in afar sheep fed varying levels of Brassica carinata cake (0.65–0.83) (20) and Menze sheep supplemented with tagasaste leaves (0.73 to 0.91). However, the Ziziphus group showed a comparable PER value to goats supplemented with Ziziphus spina-christi leaves in Ethiopia (21).

The higher PER in the Ziziphus group may be attributed to the higher levels of bypass protein available. Valizadeh et al. (22) observed that lambs fed with low, medium, and high levels of bypass protein exhibited increased ADG and PER proportional to the bypass protein levels. Additionally, the notable PER in the Ziziphus group could stem from the increased DMI, and the beneficial effects of tannins on nitrogen utilization efficiency. Orzuna-Orzuna et al. (23) reported that in ruminants, dietary supplementation of CTs enhances the efficiency of ingested feed by increasing the duodenal flow of microbial protein and amino acids without losses in the rumen (24, 25). Protein Efficiency Ratio measures the nutritive value of protein sources. The higher the PER value of a protein, the more beneficial it is to the animal. It is also the easiest method of assessing the quality of proteins (26).

The group fed with Ziziphus exhibited significantly (p < 0.01) lower CP digestibility when compared to other groups. This difference is likely attributed to the high levels of CT present in the Ziziphus group. Kumar (62) noted that condensed tannins significantly affect digestibility, yet the influence of CT on rumen digestion differs depending on their concentration, type, and activity. Additionally, except for BSG, agro-industrial by-products typically have low fiber content and high digestibility, as noted by Mengistu et al. (27).

4.2 Body weight change

Supplements sourced from indigenous plants significantly (p < 0.001) enhanced BWC and ADG compared to the Control and BSG groups. This effect may be attributed to the beneficial role of secondary plant metabolites such as CTs (28). Min et al. (29) noted that moderate levels of tannins in forage legumes offer multiple benefits for ruminants, such as improved growth rates. Reducing rumen forage protein degradation due to reversible binding to these proteins and reducing the populations of proteolytic rumen bacteria increases essential amino acid absorption from the small intestine.

In the current in vivo study, the ADG ranged from 27 g/day for the control group to 87 g/day for the Ziziphus group. This resulted in a corresponding WC of 2.4 kg to 7.9 kg, respectively, over a period of 90 days during the feeding trial. The Ziziphus group showed superior results compared to similar research conducted elsewhere in Ethiopia. For example, Hailecherkos et al. (30) found that supplementing tree lucerne (Chamaecytisus palmensis) dried leaves or concentrate mixture to Washera sheep resulted in an ADG of 51.1 to 82.2 g/day. Worku et al. (31) reported that supplementing Kafa sheep with rice bran, Sesbania (Sesbania sesban) leaf, and their mixtures resulted in an ADG of 42.4 to 86.1 g/day. Kokeb et al. (32) found that supplementing Dorper-Menz crossbred sheep fed with local brewery by-product (Atella) and concentrate mixture led to an ADG of 42.2 to 73.2 g/day. Bonsi et al. (33) studied the effect of protein supplement sources (cottonseed cake, sundried leaves of Leucaena leucocephala, and sundried leaves of Sesbania sesban) on Menz sheep and found an ADG of 32.6 to 62.9 g/day. Our findings showed lower results compared to Ali et al. (34), who reported an ADG of 46.7 to 190 g/day for Bati goat breeds in Ethiopia when supplemented with sun-dried Ziziphus spina-christi. Mangara (35) also observed superior weight gain in goats fed with Ziziphus spina-christi than those fed with Combretum adenogonium. The enhanced performance of the Ziziphus group may be attributed to its high CT content (10). Basyony et al. (36) suggested that Ziziphus spina-christi leaves could be used as a natural growth promoter in rabbit diets. Its active ingredients have been shown to have antibacterial and antifungal properties (37).

4.3 Enteric CH4 emission from sheep

Several methods have been developed to measure CH₄ emissions from ruminants. All methods have different scopes of applications, advantages, and disadvantages, and none of them is perfect in all aspects. Respiration chambers yield the most accurate measures of total enteric CH4 emissions from ruminants. Modeling and LMD are non-invasive, non-contact, user-friendly, and cost-effective methods compared to the respiration chamber, rendering them suitable for resource-constrained countries such as Ethiopia (38–40).

4.3.1 Methane production

Comparable results were observed from the LMD values and reports of other studies using respiration chambers. For instance, Pelchen and Peters (41) found 22.2 g/day from 1,137 sheep observations under various feeding conditions. Pinares-Patiño et al. (40) reported 22.7 g/day in sheep-fed grass and 18.6 g/day in those fed pellets. The CH4 production from modeling in our study was lower than that reported by Belanche et al. (16), which was 19.9 g/kg of sheep from an intercontinental database. However, it was higher than Amaral et al. (42), who reported 10.9–15.5 g/day for sheep grazing on pearl millet swards, measured using the sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) tracer technique. Chagunda et al. (43) reported that ruminating cows produced higher CH4 production using LMD than estimated by empirical modeling, which aligns with our findings. In a separate study, Chagunda et al. (44) found that LMD measurements showed higher means and variation than those taken from metabolic chambers in sheep and cattle. However, the trend of the measurements from the LMD and the metabolic chamber was similar. Therefore, LMD could be a plausible technique for CH4 emission studies in Sheep if a large number of animal data is taken.

This study observed that higher total intake relates to increased CH4 production in both CH4 estimation methods. According to Gebbels et al. (45), the main factor leading to increased net CH4 emissions in sheep meat and wool enterprises is the rise in total feed intake. In line with this, Patra et al. (46) identified feed intake as the most significant predictor of CH4 production in sheep. Belanche et al. (16) also highlighted the importance of DMI for predicting enteric CH4 emissions in sheep where DMI alone explains 80–91% of the variation in CH4 production in sheep (47). Consistent with our findings on identifying treatment differences using LMD methods, Kang et al. (48) also detected variations in CH4 emissions from cattle based on forage intake levels utilizing the LMD method. They recommended its application for assessing the effects of dietary treatments on CH4 concentrations in cattle.

4.3.2 Methane yield

CH4 yield reflects the methanogenic potential of the digestive process and correlates with CH4 production (49). In the current study, the LMD CH4 yield ranged from 16.3 to 18.5 g CH4/kg DMI, the highest observed in the Ziziphus group. The higher CH4 yield in the Ziziphus group may stem from variations in the feed’s chemical composition and degradability (50, 51). Starsmore et al. (52) stated that DMI influences CH4 emissions. Higher DMI provides more material for fermentation in the rumen, which is positively linked to CH4 emissions.

Washaya et al. (53) fed Xhosa lop-eared goats in South Africa a forage having secondary metabolites such as tannins, phenolic, and saponins and measured the CH4 using LMD and found CH4 yield of 12.6 to 13.1 g/kg DMI. Waghorn et al. (54) conducted indoor trials with sheep in metabolism crates and observed CH4 yields ranging from 11.5 g CH4/kg DMI with lotus to 25.7 g CH4/kg DMI with pasture. The current in vivo study contradicted our previous in vitro findings, showing a low CH4 yield from the indigenous plant feed source (10). Any in vitro methodology and batch culture are handy when evaluating treatments, feeds, or additives. They provide a quick response to elucidate a treatment’s potential impact on fermentation. However, they cannot necessarily be directly applied to make assumptions of responses in vivo (55). The most accurate way to evaluate the nutritional value of any feedstuff is to feed it to the appropriate class of animal using feeding trials, which is the standard measure of digestibility (56).

4.3.3 Methane emission intensity

Methane intensity strongly depends on milk or meat production output (49). Savian et al. (57) and Silva et al. (58) observed that CH4 emissions intensity from grazing sheep varied from 159 to 285 g CH4/kg ADG, and from young bulls consuming soybean lipids, it ranged between 105 to 169 g CH4/kg ADG, respectively, as measured by the SF6 tracer technique. El-Zaiat et al. (59) also observed a range of 93 to 131 g CH4/kg ADG in lambs supplemented with encapsulated nitrate and cashew nutshell liquid, using open-circuit respiration chambers for measurement.

The higher CH4 emission intensity observed in our study could be attributed to the lower fattening efficiency of the Menze breed. Indigenous sheep breeds in Ethiopia, particularly the Menz breed, are often regarded as low-producers, with the Menz breed being notably slow-growing (60). Kurihara et al. (61) highlighted the variation in CH4 emission intensity associated with live weight gain, diet quality, and fattening efficiency.

5 Conclusion

In this research, the test feed outperformed the control group in terms of body weight gain and CH4 emission intensity in sheep. The Ziziphus group notably showed a significantly greater increase in final body weight. The average enteric CH4 emission, as measured by the two methods, displayed concordance in all CH4 variables, such as CH4 production and CH4 intensity, as evidenced by strong R2. A laser CH4 detector could potentially estimate CH4 in sheep where there is no access to other measurement equipment. It is also a friendly and economical method for estimating CH4 in a country like Ethiopia. Methane emission intensity is the ideal variable related to the fattening efficiency of the sheep. Furthermore, possibly due to secondary metabolites such as CTs, the Acacia and Ziziphus groups exhibited optimal body weight gain in sheep compared to the control diet, suggesting their suitability for sustainable ruminant production in tropical regions. This study identified that the indigenous Menz breed sheep have low fattening efficiency, highlighting the need for breed improvement. In our results, feed efficiency promotes better weight gain, which leads to lower CH4 per unit of average daily gain. In conclusion, supporting research and extension services to promote the utilization of leaf meals in the diet of ruminant livestock is a sustainable feeding option in Ethiopia.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Brook Lemma Addis Ababa University, Tesfay Tessema Addis Ababa University, Addis Simachew Addis Ababa University. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

WB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. AZ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AS: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. NK: Data curation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), Sweden, funded this research (project number: 23663000).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their profound gratitude to the Debre Berhan Agriculture Research Center for using their feeding trial barn. Special appreciation is extended to farm attendants Zebene and Hailu, as well as Derib and Tamiru, for their technical support. We are immensely thankful for the support from the African Dairy Genetic Gains Project Selam Meseret for granting access to the LMD machine. Special thanks are also due to Shigidef Mekuriaw for the analysis of LMD data. We sincerely thank the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for their financial support of this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Hirpa, A, and Abebe, G. Economic significance of sheep and goats In: RC Merkel, editor. Yami, A. Addis Ababa: Sheep and goat production handbook for Ethiopia, Ethiopian Sheep and Goat Productivity Improvement Program (ESGPIP) (2008). 1–4.

2. Shapiro, BI, Gebru, G, Desta, S, Negassa, A, Nigussie, K, Aboset, G, et al. Ethiopia livestock sector analysis. ILRI Project Report. Nairobi, Kenya: International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) (2017).

3. Jemberu, WT, Li, Y, Asfaw, W, Mayberry, D, Schrobback, P, and Rushton, J. Population, biomass, and economic value of small ruminants in Ethiopia. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 9:972887. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.972887

4. CSA (Central Statistical Agency) (2022). Agricultural sample survey. Volume II. Report on livestock and livestock characteristics (private peasant holdings), Statistical Bulletin, 594. Addis Ababa. Available at: http://www.statsethiopia.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/6.The_6_2014_AGSS_2014.LIVESTOCK-REPORT_Final-3.pdf (Accessed May, 7, 2024).

5. Gizaw, S, van Arendonk, JAM, Komen, H, Windig, JJ, and Hanotte, O. Population structure, genetic variation and morphological diversity in indigenous sheep of Ethiopia. Anim Genet. (2007) 38:621–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2007.01659.x

6. Gerber, P.J., Steinfeld, H., Henderson, B., Mottet, A., Opio, C., Dijkman, J., et al. (2013). Tackling climate change through livestock: a global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Available at: https://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3437e/i3437e00.htm

7. Gaviria-Uribe, X, Bolivar, DM, Rosenstock, TS, Molina-Botero, IC, Chirinda, N, Barahona, R, et al. Nutritional quality, voluntary intake, and enteric methane emissions of diets based on novel Cayman grass and its associations with two leucaena shrub legumes. Front Vet Sci. (2020) 7:579189. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.579189

8. Baruah, L, Malik, PK, Kolte, AP, Dhali, A, and Bhatta, R. Methane mitigation potential of phyto-sources from Northeast India and their effect on rumen fermentation characteristics and protozoa in vitro. Vet World. (2018) 11:809–18. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2018.809-818

9. Leng. The impact of livestock development on environmental change In: S Mack, editor. Proceedings of the FAO expert consultation held in Rome. Italy: (1990)

10. Bekele, W, Huhtanen, P, Zegeye, A, Simachew, A, Siddique, AB, Albrectsen, BR, et al. Methane production from locally available ruminant feedstuffs in Ethiopia – an in vitro study. Anim Feed Sci Technol. (2024) 312:115977–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2024.115977

11. Tesfaye, L., Alemayehu, S., Jalango, D., Karanja, S., Magambo, G., Ghosh, A., et al. (2023) Climate-smart agriculture investment plan for Ethiopia. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/145352

12. Kobayashi, N, Hou, F, Tsunekawa, A, Yan, T, Tegegne, F, Tassew, A, et al. Laser methane detector-based quantification of methane emissions from indoor-fed Fogera dairy cows. Anim Biosci. (2021) 34:1415–24. doi: 10.5713/ab.20.0739

13. Lanzoni, L, Chagunda, MGG, Fusaro, I, Chincarini, M, Giammarco, M, Atzori, AS, et al. Assessment of seasonal variation in methane emissions of mediterranean buffaloes using a laser methane detector. Animals. (2022) 12:3487. doi: 10.3390/ani12243487

14. Reece, WO, Erickson, HH, Goff, JP, and Uemura, EE. Dukes' physiology of domestic animals. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons (2015).

15. Sorg, D, Difford, GF, Mühlbach, S, Kuhla, B, Swalve, HH, Lassen, J, et al. Comparison of a laser methane detector with the GreenFeed and two breath analysers for on-farm measurements of methane emissions from dairy cows. Comput Electron Agric. (2018) 153:285–94. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2018.08.024

16. Belanche, A, Hristov, AN, Van Lingen, HJ, Denman, SE, Kebreab, E, Schwarm, A, et al. Prediction of enteric methane emissions by sheep using an intercontinental database. J Clean Prod. (2023) 384:135523–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135523

17. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical. Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2023).

18. Kearl, L.C. (1982). Nutrient requirements of ruminants in developing countries. PhD Dissertations, Utah State University.

19. NRC. NRC (National Research Council), 2001. Nutrient requirements of small ruminants. Washington DC, USA: National Academy Press (2001).

20. Bekele, W, Assefa, G, and Urgie, M. Feeding detoxified Ethiopian mustard (Brassica carinata) seed cake to sheep: effect on intake, digestibility, live weight gain and carcass parameters. Sci J Anim Sci. (2016) 5:346–52. doi: 10.14196/sjas.v5i9.2311

21. Weldemariam, B, Melaku, S, and Tamir, B. Supplementation of Ziziphus spina-christi, Sterculia africana and Terminalia brownii to Abergelle kids fed hay: effects on feed intake, digestibility and post-weaning growth. Livest Res Rural Dev. (2014) 26:157.

22. Valizadeh, A, Kazemi-Bonchenari, M, Khodaei-Motlagh, M, Moradi, M, and Salem, A. Effects of different rumen undegradable to rumen degradable protein ratios on performance, ruminal fermentation, urinary purine derivatives, and carcass characteristics of growing lambs fed a high wheat straw-based diet. Small Rumin Res. (2021) 197:106330. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2021.106330

23. Orzuna-Orzuna, JF, Dorantes-Iturbide, G, Lara-Bueno, A, Mendoza-Martínez, GD, Miranda-Romero, LA, and Hernández-García, PA. Effects of dietary tannins’ supplementation on growth performance, rumen fermentation, and enteric methane emissions in beef cattle: a Meta-analysis. Sustain For. (2021) 13:7410. doi: 10.3390/su13137410

24. Patra, AK, and Saxena, J. Exploitation of dietary tannins to improve rumen metabolism and ruminant nutrition. J Sci Food Agric. (2021) 91:24–37. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4152

25. Subba, DB. Tree fodders and browse plants as potential nutrient suppliers for ruminants In: SP Neopane and RC Khanal, editors. Proceedings of the 3rd national workshop on livestock and fisheries research. Kathmandu, Nepal: Nepal Agricultural Research Council (1999). 97–109.

26. Lamb, MW, and Harden, ML. Protein as a source of amino acids In: The meaning of human nutrition. The Meaning of Human Nutrition: Elsevier (1972). 153–91.

27. Mengistu, A, Kebede, G, Feyissa, F, and Assefa, G. Review on major feed resources in Ethiopia: conditions, challenges and opportunities. Acad Res J Agri Sci Res. (2017) 5:176–85.

28. Cannas, A. Tannins: Fascinating but sometimes dangerous molecules. NY, USA: Cornell University (2008).

29. Min, B, Barry, T, Attwood, G, and McNabb, W. The effect of condensed tannins on the nutrition and health of ruminants fed fresh temperate forages: a review. Anim Feed Sci Technol. (2003) 106:3–19. doi: 10.1016/S0377-8401(03)00041-5

30. Hailecherkos, S, Asmare, B, and Mekuriaw, Y. Evaluation of tree lucerne (Chamaecytisus palmensis) dried leaves as a substitution for concentrate mixture on biological performance and socioeconomic of Washera sheep fed on desho grass hay. Vet Med Sci. (2021) 7:402–16. doi: 10.1002/vms3.376

31. Worku, A, Animut, G, and Urge, M. Supplementing rice bran, Sesbania (Sesbania sesban) leaf and their mixtures on digestibility and performance of Kafka sheep fed native grass hay. Int J Agric Sci Res. (2015) 4:57–66.

32. Kokeb, M, Mekonnen, Y, and Tefera, M. Feed intake, digestibility and growth performance of Dorper-Menz cross bred sheep fed local brewery by-product (Atella) and concentrate mixture at different levels of combination. Afr J Biol Sci. (2021) 3:33–41. doi: 10.33472/AFJBS.3.4.2021.33-41

33. Bonsi, M, Tuah, A, Osuji, P, Nsahlai, V, and Umunna, N. The effect of protein supplement source or supply pattern on the intake, digestibility, rumen kinetics, nitrogen utilisation and growth of Ethiopian Menz sheep fed teff straw. Anim Feed Sci Technol. (1996) 64:11–25. doi: 10.1016/S0377-8401(96)01048-6

34. Ali, A, Tegegne, F, Asmare, B, and Mekuriaw, Z. On farm evaluation of sun-dried Ziziphus spina-christi leaves substitution for natural pasture hay on feed intake and body weight change of Bati goat breeds in Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. (2019) 51:457–63. doi: 10.1007/s11250-018-1712-6

35. Mangara, J.L.I., (2018). Evaluation of the nutritive value of selected indigenous tree browses as feed for ruminant livestock in South Sudan. Doctoral dissertation. Egerton University

36. Basyony, M, Elsheikh, H, Abdel Salam, H, Mohamed, K, and Zedan, A. Utilization of Ziziphus spina-christi leaves as a natural growth promoter in rabbit’s rations. Egypt J Rabbit Sci. (2017) 27:427–46. doi: 10.21608/ejrs.2017.46666

37. Abdel-galil, FM, and El-Jissry, MA. Cyclopeptide alkaloids from Zizyphus spina-christi. Phytochemistry. (1990) 30:1348–9. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)95238-5

38. Bekele, W, Guinguina, A, Zegeye, A, Simachew, A, and Ramin, M. Contemporary methods of measuring and estimating methane emission from ruminants. Methane. (2022) 1:82–95. doi: 10.3390/methane1020008

39. Garnsworthy, PC, Difford, GF, Bell, MJ, Bayat, AR, Huhtanen, P, Kuhla, B, et al. Comparison of methods to measure methane for use in genetic evaluation of dairy cattle. Animals. (2019) 9:837. doi: 10.3390/ani9100837

40. Pinares-Patiño, C, McEwan, J, Dodds, K, Cárdenas, E, Hegarty, R, Koolaard, J, et al. Repeatability of methane emissions from sheep. Anim Feed Sci Technol. (2011) 166-167:210–8. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2011.04.068

41. Pelchen, A, and Peters, K. Methane emissions from sheep. Small Rumin Res. (1998) 27:137–50. doi: 10.1016/S0921-4488(97)00031-X

42. Amaral, G, David, D, Gere, J, Savian, J, Kohmann, M, Nadin, L, et al. Methane emissions from sheep grazing pearl millet (Penissetum americanum (L.) Leeke) swards fertilized with increasing nitrogen levels. Small RuminRes. (2016) 141:118–23. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2016.07.011

43. Chagunda, M, Ross, D, and Roberts, D. On the use of a laser methane detector in dairy cows. Comput Electron Agric. (2009) 68:157–60. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2009.05.008

44. Chagunda, M, Ross, D, Rooke, J, Yan, T, Douglas, JL, Poret, L, et al. Measurement of enteric methane from ruminants using a hand-held laser methane detector. Acta Agric Scand A Anim Sci. (2013) 63:68–75. doi: 10.1080/09064702.2013.797487

45. Gebbels, J, Kragt, M, Thomas, D, and Vercoe, P. Improving productivity reduces methane intensity but increases the net emissions of sheep meat and wool enterprises. Animal. (2022) 16:100490. doi: 10.1016/j.animal.2022.100490

46. Patra, AK, Lalhriatpuii, M, and Debnath, BC. Predicting enteric methane emission in sheep using linear and non-linear statistical models from dietary variables. Anim Prod Sci. (2016) 56:574. doi: 10.1071/AN15505

47. Muetzel, S, and Clark, H. Methane emissions from sheep fed fresh pasture. N Z J Agric Res. (2015) 58:472–89. doi: 10.1080/00288233.2015.1090460

48. Kang, K, Cho, H, Jeong, S, Jeon, S, Lee, M, Lee, S, et al. Application of a hand-held laser methane detector for measuring enteric methane emissions from cattle in intensive farming. J Anim Sci. (2022) 100:skac211. doi: 10.1093/jas/skac211

49. Fresco, S, Boichard, D, Fritz, S, Lefebvre, R, Barbey, S, Gaborit, M, et al. Comparison of methane production, intensity, and yield throughout lactation in Holstein cows. J Dairy Sci. (2023) 106:4147–57. doi: 10.3168/jds.2022-22855

50. Benchaar, C, Pomar, C, and Chiquette, J. Evaluation of dietary strategies to reduce methane production in ruminants: a modelling approach. Can J Anim Sci. (2001) 81:563–74. doi: 10.4141/A00-119

51. Blümmel, M, Aiple, P, Steingaβ, H, and Becker, K. A note on the stoichiometrical relationship of short chain fatty acid production and gas formation in vitro in feedstuffs of widely differing quality. Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. (1999) 81:157–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0396.1999.813205.x

52. Starsmore, K, Lopez-Villalobos, N, Shalloo, L, Egan, M, Burke, J, and Lahart, B. Animal factors that affect enteric methane production measured using the GreenFeed monitoring system in grazing dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. (2024) 107:2930–40. doi: 10.3168/jds.2023-23915

53. Washaya, S, Mupangwa, J, and Muchenje, V. Chemical composition of Lablab purpureus and Vigna unguiculata and their subsequent effects on methane production in Xhosa lop-eared goats. S Afr J Anim Sci. (2018) 48:445–58. doi: 10.4314/sajas.v48i3.5

54. Waghorn, GC, Tavendale, MH, and Woodfield, DR. Methanogenesis from forages fed to sheep. Proceed NZ Grassland Assoc. (2002) 64:167–71. doi: 10.33584/jnzg.2002.64.2462

55. Vinyard, JR, and Faciola, AP. Unraveling the pros and cons of various in vitro methodologies for ruminant nutrition: a review. Transl Anim Sci. (2022) 6:txac130. doi: 10.1093/tas/txac130

56. Olubunmi Olowu, O, and Yaman, S. Feed evaluation methods: performance, economy, and environment. Eurasian J Agric Res. (2019) 3:48–57.

57. Savian, JV, Neto, AB, De David, DB, Bremm, C, Schons, RMT, Genro, TCM, et al. Grazing intensity and stocking methods on animal production and methane emission by grazing sheep: implications for integrated crop–livestock system. Agric Ecosyst Environ. (2014) 190:112–9. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2014.02.008

58. Silva, RA, Fiorentini, G, Messana, JD, Lage, JF, Castagnino, PS, San Vito, E, et al. Effects of different forms of soybean lipids on enteric methane emission, performance and meat quality of feedlot Nellore. J Agric Sci. (2018) 156:427–36. doi: 10.1017/S002185961800045X

59. El-Zaiat, HM, Araujo, RC, Soltan, YA, Morsy, AS, Louvandini, H, and Pires, AV. Encapsulated nitrate and cashew nutshell liquid on blood and rumen constituents, methane emission, and growth performance of lambs. J Anim Sci. (2014) 92:2214–24. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-7084

60. Tibbo, M., (2006). Productivity and health of indigenous sheep breeds and crossbreds in central Ethiopian highlands. Doctoral dissertation, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Available at: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/b5a3c464-01ca-42bd-8169-edc3abba4904/content (Accessed May, 7, 2024).

61. Kurihara, M, Magner, T, Hunter, RA, and McCrabb, GJ. Methane production and energy partition of cattle in the tropics. Br J Nutr. (1999) 81:227–34. doi: 10.1017/S0007114599000422

Keywords: condensed tannins, laser methane detector, local sheep, methane emission, modeling, protein efficiency ratio, Ziziphus spina-christi

Citation: Bekele W, Zegeye A, Simachew A and Kobayashi N (2025) Effect of best bet methane abatement feed on feed intake, digestibility, live weight change, and methane emission in local Menz breed sheep in Ethiopia. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1538758. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1538758

Edited by:

Valiollah Palangi, Ege University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Muhammad Jabbar, Cholistan University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, PakistanMoyosore Joseph Adegbeye, University of Africa, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

Copyright © 2025 Bekele, Zegeye, Simachew and Kobayashi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wondimagegne Bekele, d29uZGltYWdlZ25lLmJla2VsZUBzbHUuc2U=

Wondimagegne Bekele

Wondimagegne Bekele Abiy Zegeye

Abiy Zegeye Addis Simachew

Addis Simachew Nobuyuki Kobayashi

Nobuyuki Kobayashi