- 1Center of Excellence for Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases in Animals, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

- 2The International Graduate Course of Veterinary Science and Technology, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

- 3Department of Veterinary Public Health, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

Feline coronavirus (FCoV) is a significant pathogen that infects the feline population worldwide. FCoV can cause mild enteric disease and a fatal systemic disease called feline infectious peritonitis (FIP). In this study, a cross-sectional survey of FCoV in domestic cats from small animal hospitals in Thailand was conducted from January to December 2021. Our result showed that out of 238 samples tested for FCoV using 3’ UTR-specific RT-PCR, 18.7% (28/150) of asymptomatic cats and 25.5% (12/47) of cats with unknown status tested positive for FCoVs. Additionally, 51.2% (21/41) of cats with suspected FIP were found to be positive for FCoVs. Genotype identification using S gene-specific RT-PCR showed that all FCoV-positive samples (n = 61) were FCoV type I. This study obtained the whole genome sequences (n = 3) and S gene sequences (n = 21) of Thai-FCoVs. Notably, this study is the first to report the whole genome of Thai-FCoV. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that Thai-FCoVs were closely related to FCoVs from China and Europe. Additionally, the Thai-FCoVs exhibited specific amino acid substitutions (M1058L) associated with the pathotype switch. Recombination events were found to mainly occur in the ORF1ab and S gene regions of Thai-FCoVs. This study provides insights into the occurrence, genetic diversity, virulence amino acid mutations, and potential recombination of FCoVs in the domestic cat population in Thailand, contributing to our understanding of FCoV epidemiology.

Introduction

Feline coronavirus (FCoV) is an enveloped, non-segmented, single-stranded RNA virus that belongs to the family Coronaviridae and genus Alphacoronavirus. The viral genome consists of 11 open reading frames (ORFs) and encodes 11 proteins: Replicase 1a and 1b polyproteins (1ab), Spike (S), Envelope (E), Matrix (M), Nucleocapsid (N), ORF3abc and 7ab (1, 2). FCoVs can be classified into two pathotypes, feline enteric coronavirus (FECV) and feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), based on the pathogenicity (3). FECV usually leads to mild enteritis, while FIPV causes a systemic lethal disease known as feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) (4, 5). Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP) is usually characterized by protein-rich serous effusion in the body cavity and granulomatous inflammatory lesions in the internal organs (6). The switch from FECV to FIPV is not well understood, but previous studies suggested that mutations in the FECV genome may be responsible for the emergence of FIPV (3, 7–9). FCoV can also be genetically classified into two genotypes, FCoV type I and FCoV type II, based on structural differences in the S gene (10). Among the two genotypes, FCoV type I is more predominant than FCoV type II worldwide. While FCoV type II originated from a recombination between FCoV type I and canine coronavirus (CCoV) (11). Both FCoV genotype I and genotype II can cause FIP (12–15).

In Thailand, the first report of FCoV was documented in 2003 (16). It was documented that FCoV type I had a higher prevalence than FCoV type II, and mixed infection of both genotypes was also found (15). The sequence analysis on the ORF3abc, E, M, N, and 7ab genes of Thai-FCoVs was also documented (17). Currently, there are only 120 nucleotide sequences of certain genes (3abc, 7ab, S, E, M, N) of Thai-FCoVs available in the GenBank database. However, information on the whole genome and completed S gene sequences of Thai-FCoVs is still limited. Therefore, in this study, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of FCoV and characterized the whole genome, and completed S gene of Thai-FCoVs to obtain information on the genetic diversity of circulating Thai FCoVs. This study is the first to report the whole-genome characterization of Thai-FCoVs.

Materials and methods

Sample collection from domestic cats

In this study, we conducted a cross-sectional sample collection from 12 animal hospitals in Bangkok and the vicinity from January to December 2021. A total of 238 samples were collected from cats during hospital visits, including 197 rectal swab samples and 41 abdominal/thoracic fluid samples. The samples were collected from Bangkok (n = 133), Nonthaburi (n = 80), and Samut Prakan (n = 25). In this study, we collected rectal swab samples from asymptomatic cats (n = 150) and cats with unknown status (n = 47) (cats with various clinical signs, e.g., fever, diarrhea, vomiting, anorexia, coughing, and chronic diseases). We also acquired abdominal and/or thoracic fluid samples (n = 41) from cats suspected to have FIP, which developed effusions in the body cavity. Data related to the collection date, age, breed, sex, and clinical status of all animals were recorded. This study was conducted with approval from the Institute of Animal Use and Care Committee (IACUC# 2331076), and all procedures were completed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Molecular detection of FCoV

The samples, including rectal swab samples (n = 197) and fluid samples (n = 41), were subjected to RNA extraction using a magnetic bead-based automatic purification equipment of GENTi™ 32—Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction System (GeneAll®, Seoul, South Korea). Briefly, the rectal swab sample was vortexed for at least 15 s before removing the swab. Next, 7 μL of RNA carrier was added to the extraction tube, and 200 μL of sample was then added to the same tube. The RNA extraction was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted RNA was kept at −20°C until testing.

For the detection of FCoV, one-step RT-PCR was performed using primers targeting the 3’UTR region of the FCoV genome (10). Briefly, one-step RT-PCR was conducted in a total final volume of 25 μL comprised of 3 μL of template RNA, 1x reaction mix, 0.25 μM of each forward and reverse primer, 20 units of SuperScript III RT (Invitrogen, United States) and distilled water. The RT-PCR conditions included a cDNA synthesis step at 55°C for 30 min, an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, extension at 68°C for 30 s, and a final extension step at 68°C for 5 min. To confirm FCoV, 3 μL of PCR product was run on a 1.5% agarose gel with red safe. The expected size of the positive FCoV product was 223 base pairs.

Genotype identification and whole genome sequencing of FCoV

All FCoV-positive samples (n = 61) were subjected to genotype identification using S gene-specific RT-PCR as previously described (18). The PCR condition included a cDNA synthesis step at 55°C for 30 min, an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, extension at 68°C for 30 s, and a final extension step at 68°C for 5 min. The expected product size for FCoV type I and FCoV type II is 360 bp and 238 bp, respectively.

After genotyping, we selected 24 representative FCoV-positive samples based on the based on the date, location, and clinical status of the animal for whole genome and S gene sequencing. First, the RNA was subjected to cDNA synthesis with random hexamers using SuperScript™ IV Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After cDNA synthesis, the whole genome and S gene sequencing were performed using newly designed specific primers by Primer 3 plus and primer sets described previously (Supplementary Table S1) (19). The protocol used to amplify all ORFs of FCoV with Platinum™ Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR conditions included an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 30 s, 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s, an annealing step depending on the primer Tm for 30 s, and an extension step at 68°C for 1–2 min. A final extension step at 68°C for 7 min was included. The amplified PCR products were then pooled together and purified using NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up (MACHEREY-NAGEL™, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The whole genome and S gene sequencing were performed using an Oxford Nanopore rapid sequencing kit (SQK-RAD004) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In detail, first, to prepare the DNA library, 3.75 μL of purified PCR product was mixed with 1.25 μL of fragmentation mix (FRA) and incubated in a thermocycler at 30°C for 1 min, then at 80°C for 1 min, and finally cooled on ice. After that, 0.5 μL of rapid adapter (RAP) was added and incubated at 25°C for 5 min. To complete the DNA library loading, 15 μL of sequencing buffer (SQB), 10 μL of loading beads (LB), and 5 μL of nuclease-free water were added. The flow cell priming mix was prepared by the mix of 3 μL flush tether (FLT) with 117 μL of flush buffer (FB). For sequencing, 200 μL of flow cell priming mix was firstly loaded to the flow cell, and then 30 μL of prepared DNA library was followed, and the sequencing process was started through MinKNOW software. After sequencing, MinKNOW software was used to convert the data from Fasta 5 file format to Fastq file format. A minimum Q-score of 7 was used to filter out the low-quality sequences. The nucleotide sequences were assembled using de-novo assembly with Genome Detective web software1 and Qiagen CLC Genomics Benchwork version 20.0.4 software (QIAGEN, CA, United States).2 In this study, we have accomplished three whole genome sequences, nine complete S gene sequences, and twelve partial S gene sequences. The nucleotide sequences were submitted to the GenBank database under the accession # PP901870-PP901890 and PP908788-PP908790.

Phylogenetic and genetic analyses of Thai-FCoVs

The phylogenetic analysis involved comparing nucleotide sequences of each gene of Thai-FCoVs with reference nucleotide sequences of CoVs from the GenBank database. The reference CoVs were chosen based on their different geographical distributions and hosts. The phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA v.11.0.11 software with a neighbor-joining method and Kimura 2-parameter with 1,000 bootstrap replications (20). Thai-FCoV sequences from this study and reference CoV sequences were aligned using the ClustalW function. For each gene analysis, the nucleotide sequences of each gene of FCoV were used to generate the phylogenetic tree of the virus using MEGA v.11.0.11 software. For pairwise comparison, nucleotide sequences and amino acids of Thai-FCoVs were aligned with those of reference CoVs, and calculated using the pairwise distance function in MEGA v.11.0.11 software. For genetic analysis, deduced amino acids of Thai-FCoVs were aligned with those of reference CoVs using MegAlign version 5.03 (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI, United States) software.

Recombination analysis of Thai-FCoVs

RDP5 and Simplot v.3.5.1 programs were used to detect potential recombination events of Thai-FCoVs in this study. Only whole genome sequences were used for analysis. In brief, potential recombination events were identified using the RDP5 program, which included different methods with an acceptable p-value of 0.05 (21). Subsequently, the potential recombination breakpoints were further identified using the Simplot v.3.5.1 program using the bootscan function with the neighbor-joining model, 1,000 bootstrap replicates, and Kimura (2-parameter) distance model. A sliding window of 1,000 nucleotides and 200 nucleotide steps was used as the default settings (22).

Statistical analysis

The association of FIP-related clinical presentations and amino acid substitution at positions 1,058 and 1,060 of the fusion protein in S protein was performed using the chi-square test in IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29.0.1.0. A p-value of < 0.01 was considered statistically significant.

Results

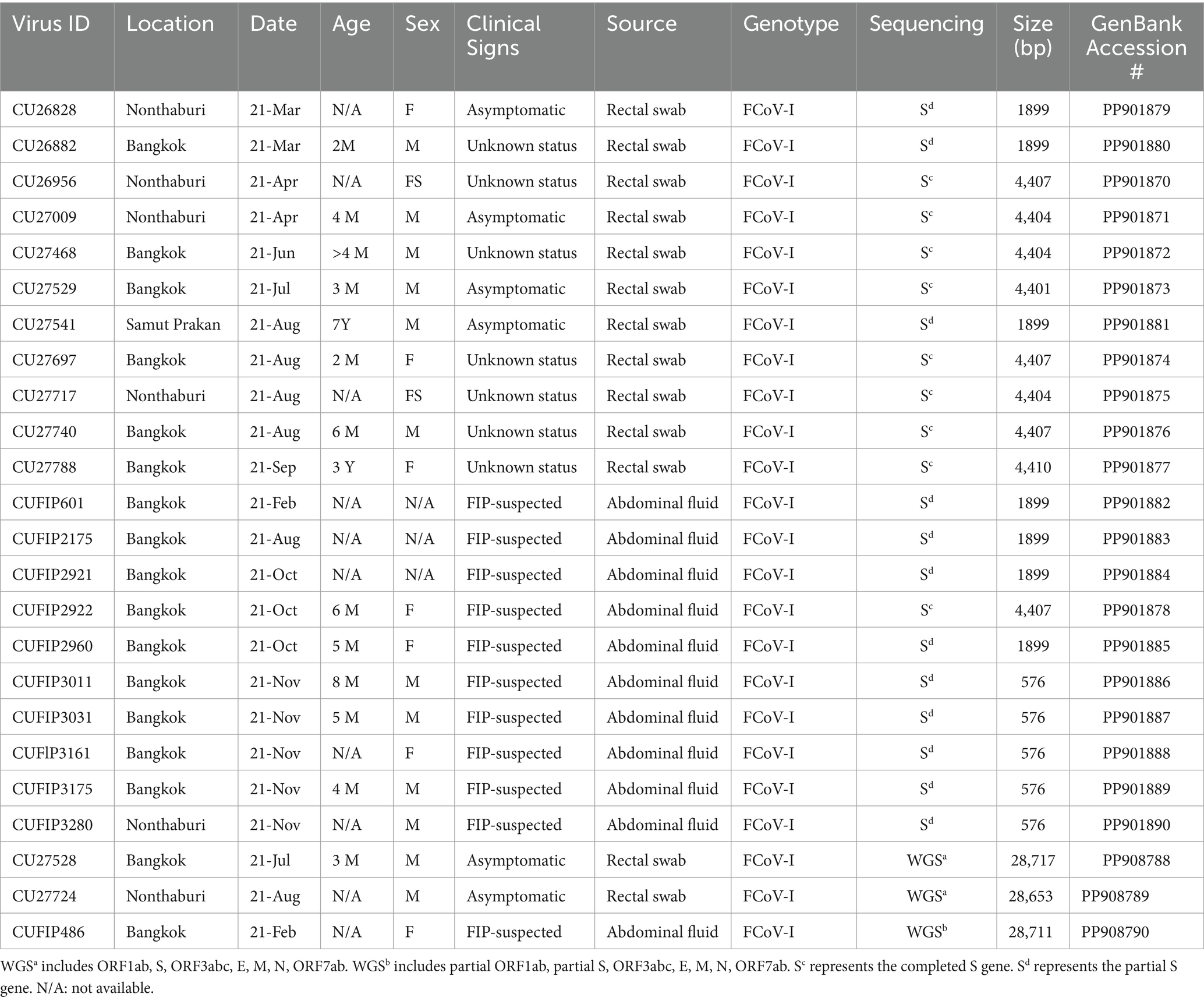

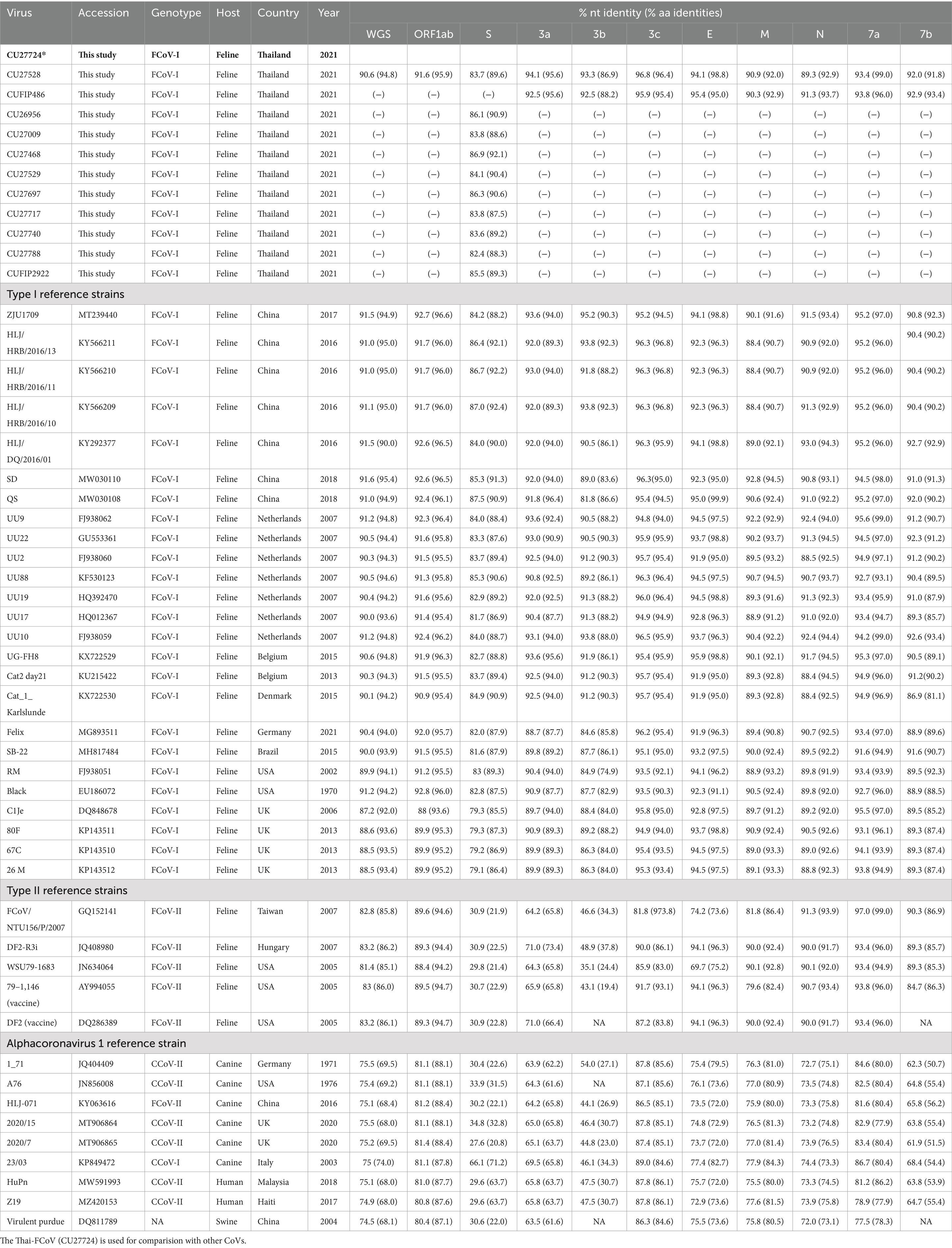

From January to December 2021, a total of 238 samples from domestic cats, including 197 rectal samples and 41 abdominal/thoracic fluid samples, were collected from 12 small animal hospitals in Bangkok, Nonthaburi, and Samut Prakan. In this study, the domestic cats were categorized into three groups based on their clinical status: asymptomatic cats, cats with unknown status (sick cats with general clinical signs), and FIP-suspected cats (cats with clinical signs and the development of effusion in the body cavity). The 238 samples were tested for FCoV using RT-PCR specific to the 3’UTR region, and 18.7% (28/150) of asymptomatic cats and 25.5% (12/47) of cats with unknown status tested positive for FCoVs. Meanwhile, 51.2% (21/41) of FIP-suspected cats were found positive for FCoVs (Table 1). The positive rates of FCoV in Bangkok, Nonthaburi, and Samut Prakan were 32.3% (43/133), 16.3% (13/80), and 20.0% (5/25), respectively. Cats younger than six months were more likely to be infected with FCoV (41.30%, 19/46) than adults and older, with a statistically significant (p-value < 0.01). While FCoV infection was slightly higher in male cats, 26.0% (32/123) than in female cats, but it was not statistically significant. Moreover, the FCoV positive rate was the highest in winter, with 29.51% (18/61) (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 1. List of samples collected and FCoV identification by location, age, sex, season, and clinical presentations in this study.

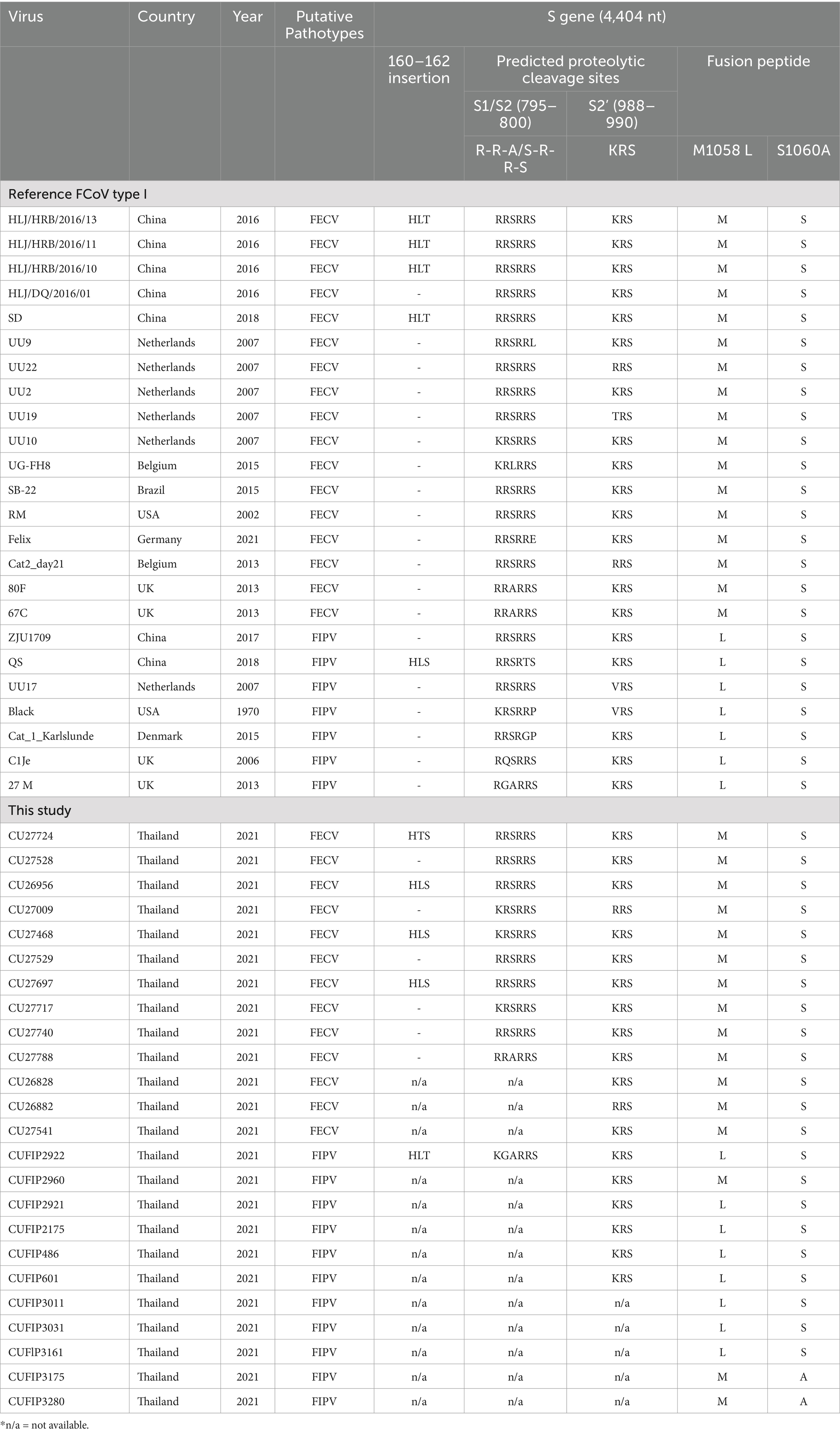

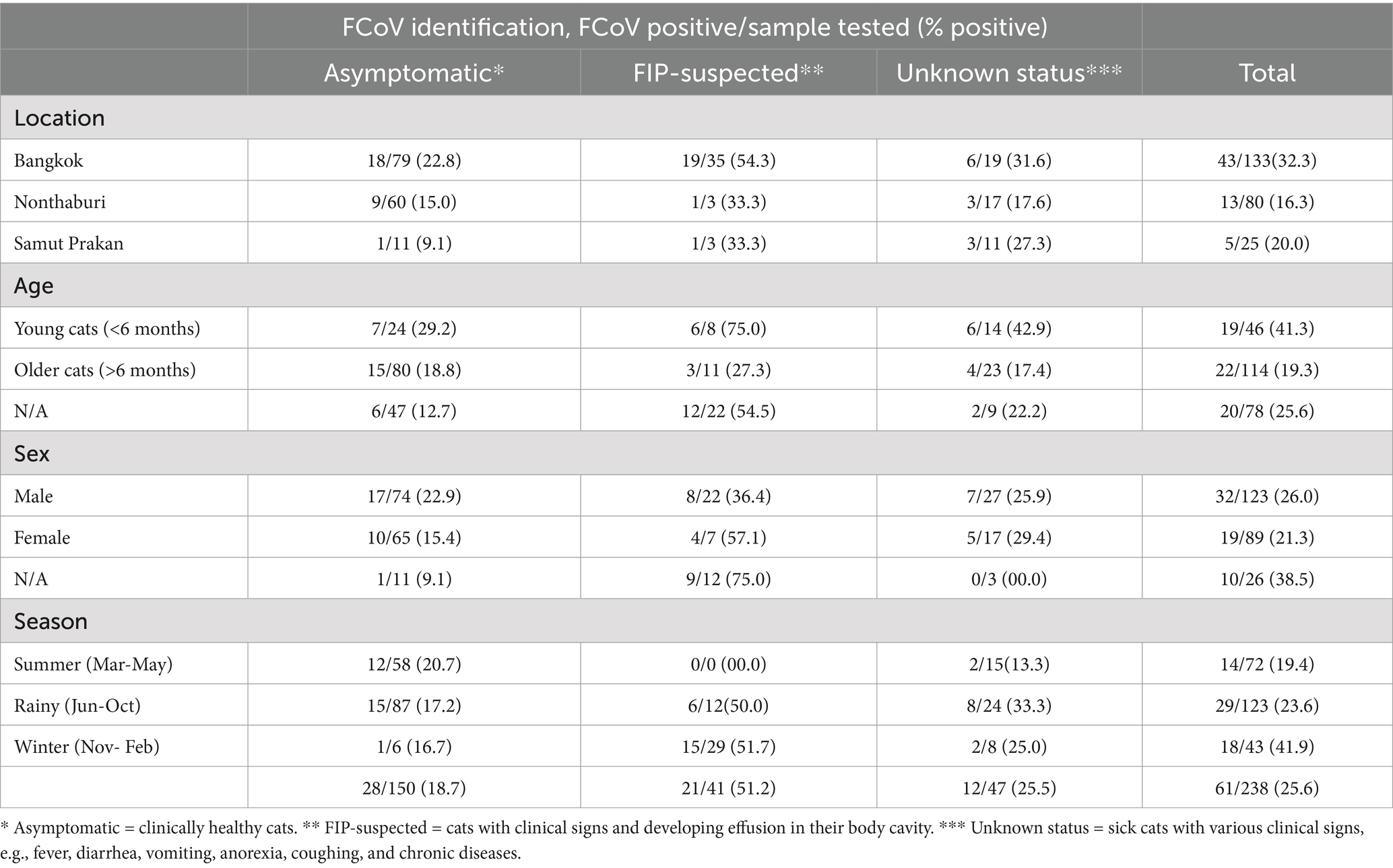

The genotype identification of FCoVs by the S gene-specific RT-PCR assay was performed. Our result revealed that all FCoV-positive samples (n = 61) were identified as FCoV type I (Supplementary Table S3). Of 61 FCoV-positive samples, 24 representative samples were selected based on the date, location, and clinical status of the animal. Then, the samples were subjected to genetic characterization by whole genome and S gene sequencing. In this study, 3 whole genome sequences (CU27724, CU27528, and CUFIP486) were obtained. In addition, completed and partial S gene sequences of representative FCoVs (n = 21) were obtained (Table 2). For pairwise comparison, Thai-FCoV (CU27724) had high nucleotide and amino acid identities to FCoV type I from China (strain SD, 91.6% nt identities, 95.4% aa identities), and the Netherlands (strain UU10, 91.2% nt identities, 94.8% aa identities). However, Thai-FCoV has low identities with FCoV type II from the USA (Vaccine strain DF2, 83.2% nt identities, 86.1% aa identities). Moreover, Thai-FCoV possesses 74.5–75.5% (nt identities) and 68.0–74.0% (aa identities) with the other reference Alphacoronaviruses (Table 3). For S gene analysis, identities within the Thai-FCoVs ranged from 83.6–86.9% nucleotide identities and 87.5–92.1% amino acid identities. While Thai-FCoV had high identities with FCoV type I from China (HLJ/HRB/2016/10, 87.0% nt, 92.4% aa), it possessed a remarkably low identity of 30.9% (nt) and 22.8% (aa) with the FCoV type II, vaccine strain (DF2) (Table 3).

Table 3. Pairwise comparison of whole genome nucleotide and amino acid sequences of Thai-FCoV (CU27724) with reference alpha coronaviruses.

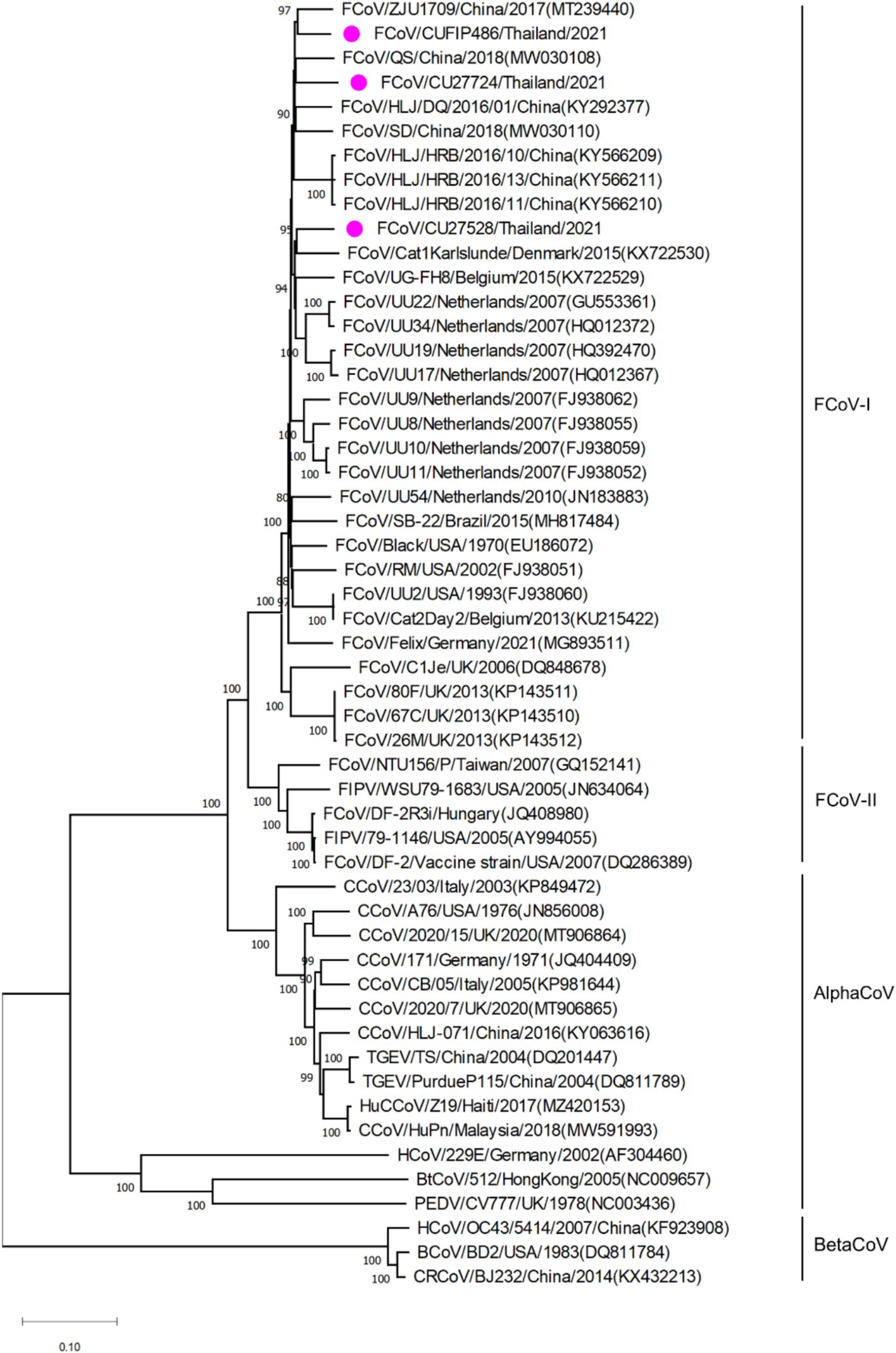

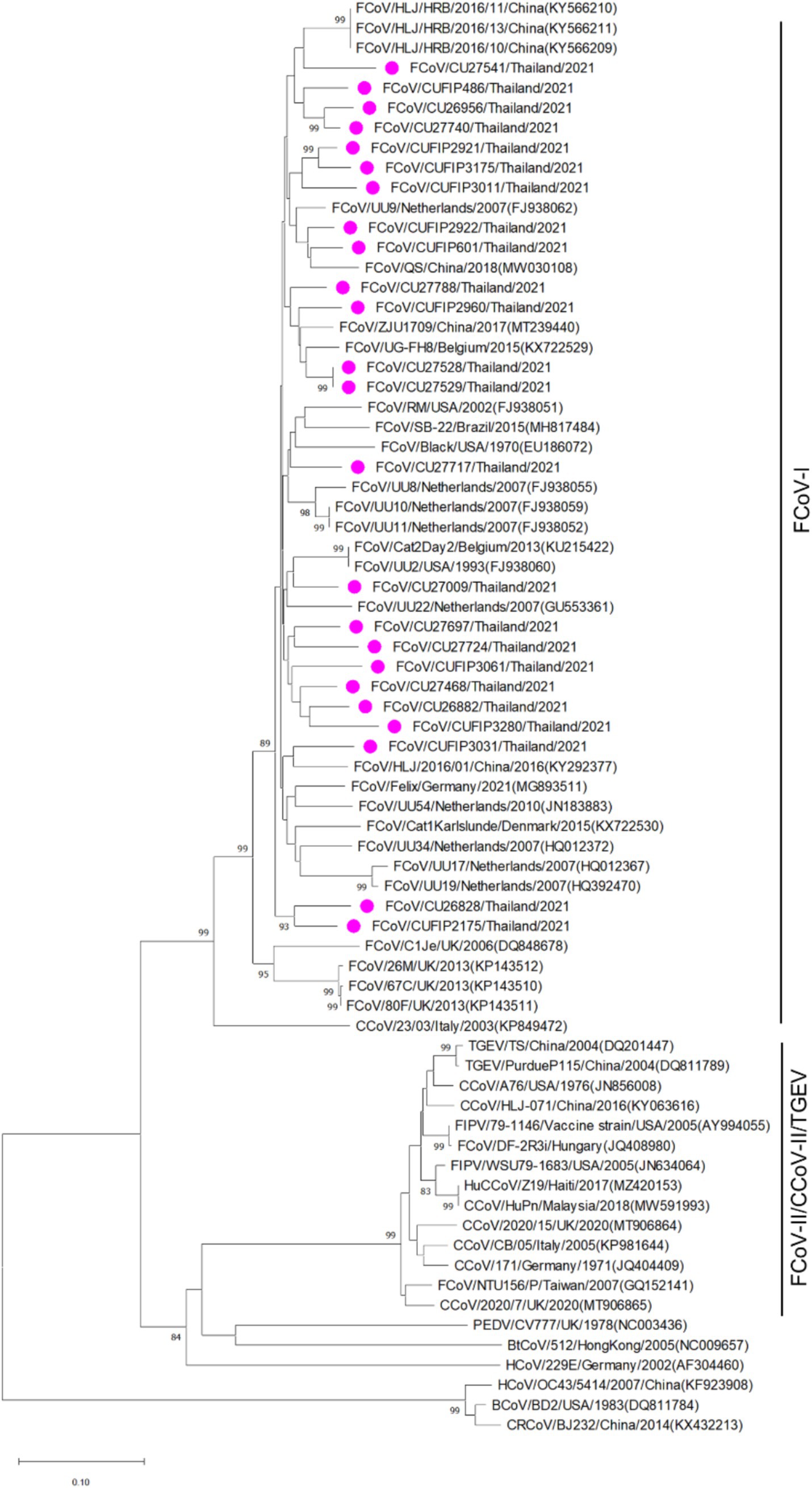

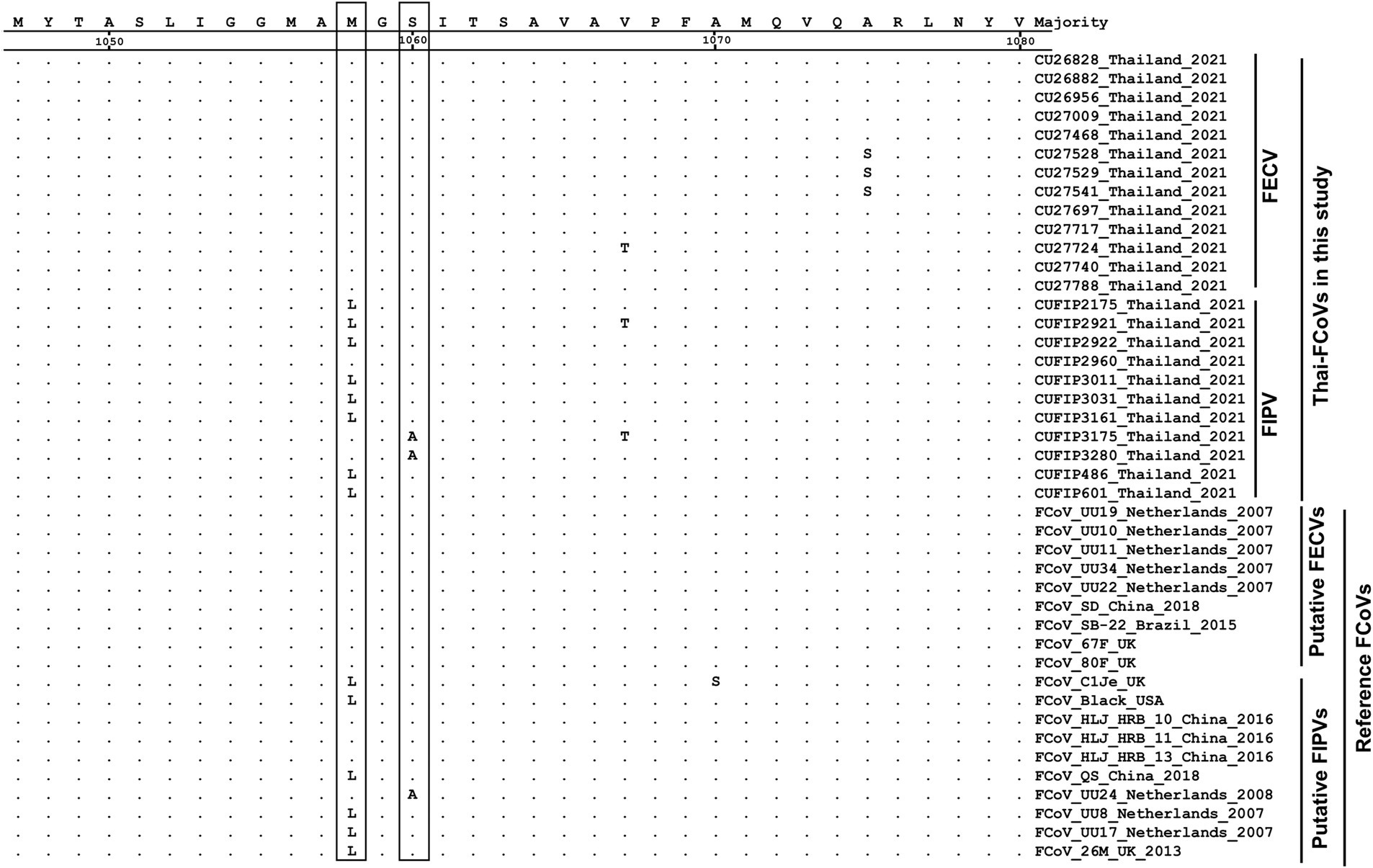

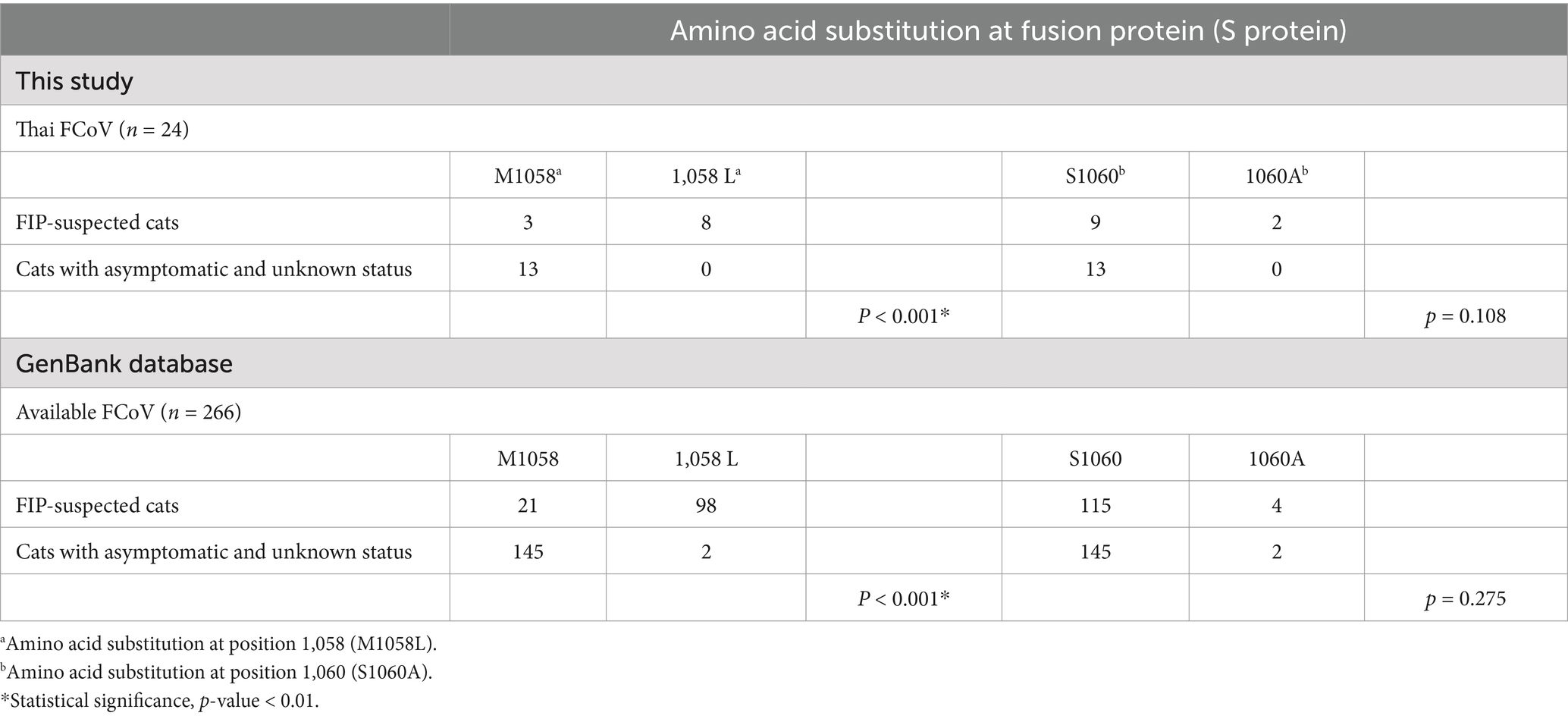

The phylogenetic tree of whole genome sequences of Thai-FCoVs (CU27724, CU27528, CUFIP486) showed that Thai-FCoVs belonged to FCoV type I. It is noted that the CU27724 and CUFIP486 were closely related to Chinese FCoV (QS and ZJU1709 strain), and the CU27528 was closely related to FCoV from Denmark (Karlslunde strain) (Figure 1). Phylogenetic analysis of the S gene showed that Thai-FCoVs (n = 24) were clustered with FCoV type I (Figure 2). Similar findings were observed in the phylogenetic analyses of each gene (ORF1ab, E, M, N, 7ab) (Supplementary Figures S1–S4). Based on the genetic analysis of the S gene, we analyzed two predicted proteolytic cleavage sites, S1/S2, and S2 regions (8, 9). For the S1/S2 region (R-R-S-R/A-R-S), all Thai-FCoVs contained R-R-S-R/A-R-S, consistent with the reference FCoV type I. In the S2 subunit region (K-R-S), all Thai-FCoVs contained K-R-S, which were identical to reference FCoV type I. It should be noted that our findings suggested that the amino acid residues in the predicted proteolytic cleavage sites are not associated with the transition between two pathotypes, and further analysis is needed. In this study, the putative fusion peptides (positions 1,058 and 1,060) were analyzed as in the previous study (7). All Thai-FCoVs obtained from the rectal swabs from asymptomatic cats or cats with unknown status (n = 13), also known as Feline Enteric Coronaviruses (FECV), exhibited a conserved methionine at amino acid position 1,058 (M1058). While 8 out of 11 Thai-FCoVs, obtained from the abdominal fluid of cats suspected to have Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIPV), showed an amino acid substitution to leucine at position (1,058 L). The association of FIP-suspected cases (FIPV) and genetic mutation at M1058L was statistically significant (p < 0.001). To expand this observation, we further analyzed 266 FCoV nucleotide sequences available in the GenBank database. The association of FIP-suspected cases (FIPV) and genetic mutation at M1058L (98 out of 119) was observed, with statistical significance (p < 0.001). It is noted that most Thai-FIPVs (except CU3175 and CU3280) and FIPVs in the GenBank database contained S1060 but were not statistically significant (Figure 3; Tables 4, 5).

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree based on whole genome of Thai-FCoVs and reference alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses. The rooted phylogenetic tree was constructed by using MEGA v.7.0 with a neighbor-joining algorithm with kimura-2 parameter model and bootstrap analysis of 1,000 replications. The bootstrap values are displayed next to the nodes. Pink circles indicate the whole genome sequence of Thai-FCoVs.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree based on the partial S gene of Thai-FCoVs and reference alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses. The rooted phylogenetic tree was constructed by using MEGA v.7.0 with a neighbor-joining algorithm with kimura-2 parameter model and bootstrap analysis of 1,000 replications. The bootstrap values are displayed next to the nodes. Pink circles indicate the partial S gene sequences of Thai-FCoVs.

Figure 3. Alignment of amino acids of S gene of Thai-FCoVs with reference FCoVs. The boxes indicate the amino acid substitutions suggesting hotspots for differentiation between two pathotypes.

Table 5. Analysis of the association of FIP-related clinical presentations and amino acid substitution at positions 1,058 and 1,060 of fusion protein (S protein).

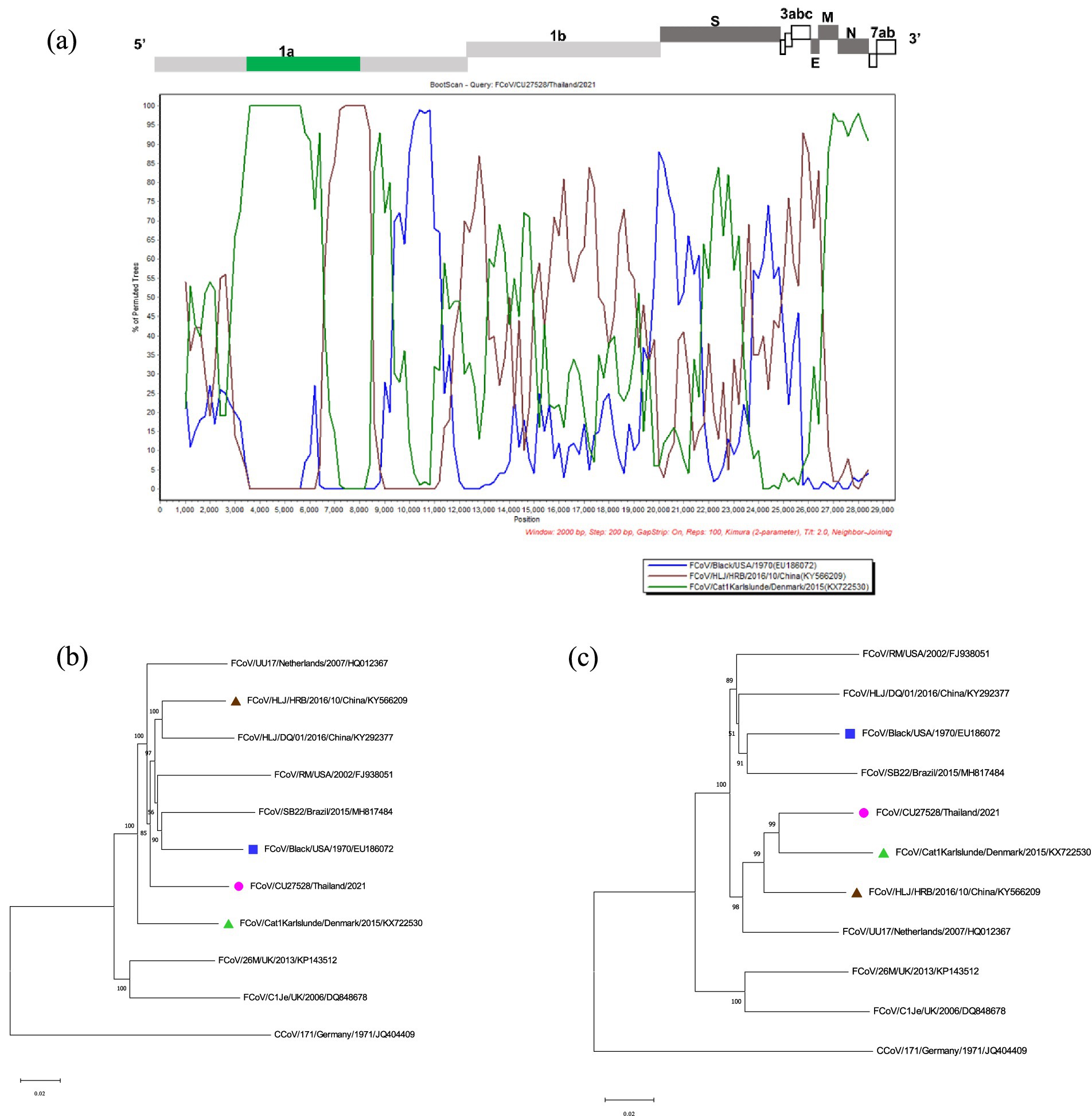

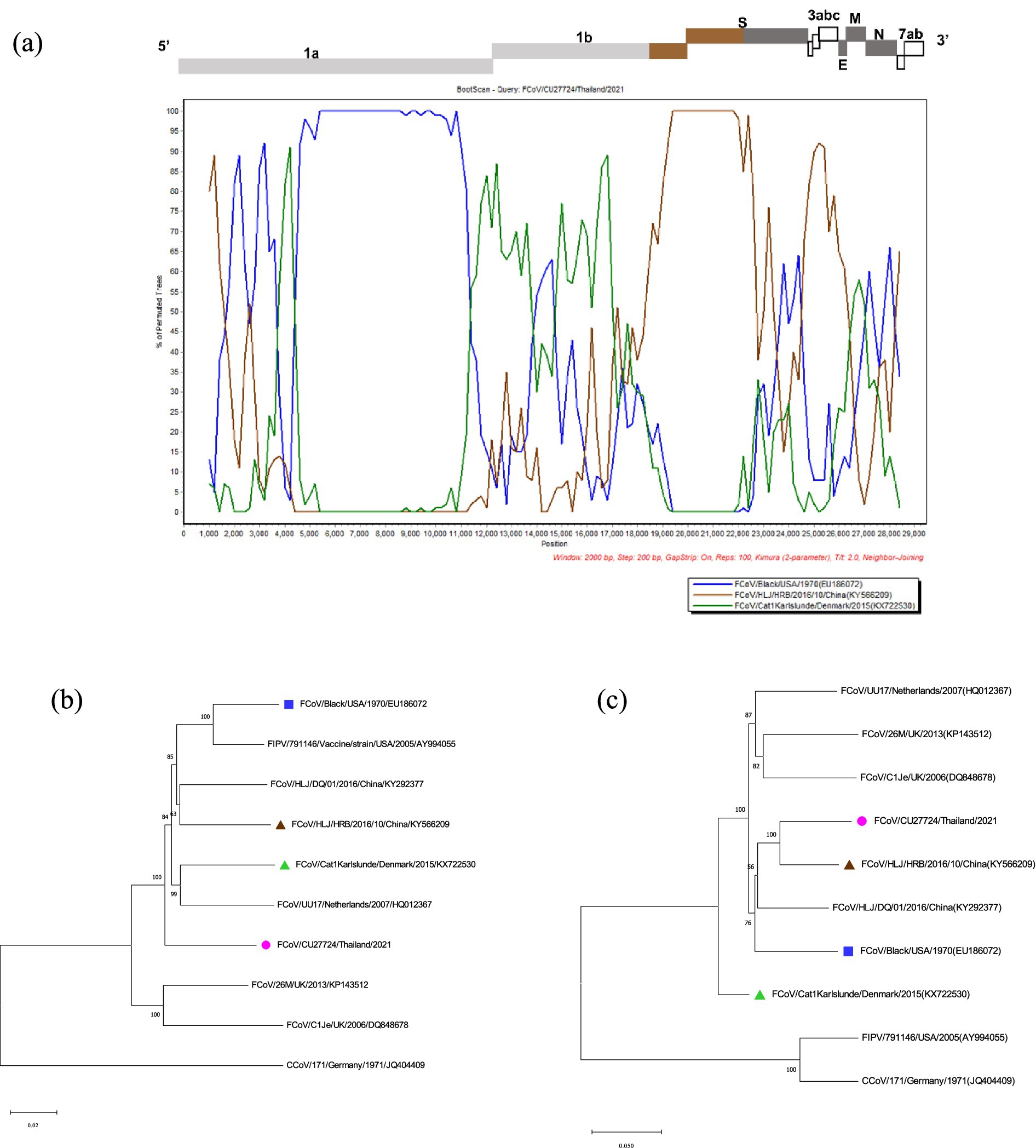

The potential recombination events were analyzed using the RDP5 and confirmed by the bootscan analysis of Simplot software (21, 22). The whole genome sequences of Thai-FCoVs (CU27528, CU27724) from this study were selected for recombination analysis. For CU27528, the recombination event was found at the ORF1ab gene with significant p-values (Figure 4). FCoV/Black/USA/1970 (Blue line) and FCoV/Cat1Karlslunde/Denmark/2015 (Green line) were identified as the major parent and minor parent, respectively. The Simplot results indicated that the majority of the genome of CU27528 is derived from FCoV/Black/USA/1970, except at nucleotide position 4,316–11,068, suggesting acquisition from FCoV, Karlslunde strain. The phylogenetic analysis also supported this recombination pattern (Figure 4). For CU27724, the recombination event was identified at the 3′ end of ORF1b and two-thirds of the S gene, with significant p-values (Figure 5). FCoV/Black/USA/1970 (Blue line) and FCoV/HLJ/HRB/10/China/2016 (Brown line) were identified to be the major and minor parent, respectively. The Simplot results showed that CU27724 contains most of its genome from the FCoV Black strain, except at nucleotide position 18,204–23,093, which was acquired from the FCoV Chinese strain. The phylogenetic analysis also supports this recombination pattern (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Results of recombination analysis of CU27528. (A) Bootscan analysis of Thai-FCoV indicates the recombinant CU27528. (B) The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the region derived from the major parent (C) The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the region derived from the minor parent. The pink circle in phylogenetic analysis indicates the Thai-FCoV strain, and the blue square and green triangle indicate the potential major parent strain and minor parent strain, respectively.

Figure 5. Results of recombination analysis of CU27724. (A) Bootscan analysis of Thai-FCoV indicates the recombinant CU27724. (B) The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the region derived from the major parent (C) The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the region derived from the minor parent. The pink circle in phylogenetic analysis indicates the Thai-FCoV strain, and the blue square and brown triangle indicate the potential major parent strain and minor parent strain, respectively.

Discussion

Feline coronavirus (FCoV) is a significant pathogen in wild and domestic cat populations. FCoV can cause mild enteritis to the fatal disease named feline infectious peritonitis (FIP). In Thailand, there have been only three reports of FCoVs, and information on the whole genome of this virus remains lacking (15–17). To our knowledge, this study is the first report on the whole genome characterization of feline coronavirus (FCoV) from cats in Thailand. Our study provided whole genome sequences and spike gene sequences of Thai-FCoVs and contributed to the expansion of genetic information of FCoVs to the scientific database.

In this study, we found FCoVs in 18.7% of asymptomatic cats, 25.5% of cats with unknown status, and 51.2% of FIP-suspected cats. A 51.2% of FIP-suspected cats tested positive for FCoV, which was higher than the reports from Korea (19.3%), Thailand (46.0%), and Turkey (37.3%) (15, 23, 24), but lower than the report in China (75.7%) (18). It is important to note that the high percentage of FCoV positive in FIP-suspected cats in this study may be due to the bias in sampling for testing FIP-suspected cases and diagnostic services. In this study, we observed that FCoV was more frequently detected in cats younger than 6 months old, consistent with previous studies. For example, studies in China and Japan reported that FCoV was mostly detected in younger cats (14, 18, 25, 26). However, a few reports from Australia, Hungary, and Malaysia suggested that FCoV infection was not related to age (27–29). In contrast, our results suggested that young age may be associated with the higher occurrence of FCoV in cats with statistical significance. Since FCoV was detected in cats of all ages, it is possible that some cats could be chronically infected and become asymptomatic carriers. In this study, FCoV infection in male cats was slightly higher than in female cats but not statistically significant, consistent with other studies (14, 30, 31). In this study, FCoV can be detected year-round and is more frequently found in the winter, suggesting a possible seasonal pattern of FCoV in cats but not statistical significance. However, there are some reports that FCoV was not related to the season (25, 32, 33). These data suggest that the association between age, sex, weather, and susceptibility/resistance to FCoV remains uncertain due to no statistical significance. Our study categorized cats into three groups based on their clinical status: asymptomatic cats, cats with unknown status (cats with other clinical symptoms), and FIP-suspected cats (cats with clinical signs and development of effusion in body cavities). Our results showed that FCoV could be detected in cats regardless of their clinical status, which is in line with previous studies (15, 18). Regardless of their clinical status, the consistent positive rate of FCoVs in cats indicates that asymptomatic cats could serve as reservoirs for susceptible animals. This finding raises concern about the prevention and control of the virus.

FCoVs can be classified into two distinct genotypes, FCoV type I and FCoV type II, based on genetic variations in the S gene (11). Our results showed that all positive samples were identified as FCoV type I, while FCoV type II could not be detected. Our finding aligns with a previous study in Thailand, supporting the predominance of FCoV type I in the country (15). In contrast, FCoV type II is less predominant in the field (34, 35). The phylogenetic tree of the whole genome also showed that Thai-FCoVs belonged to FCoV type I, and were closely related to FCoVs from China and Europe. This suggested that FCoV type I predominantly circulates in domestic cats in Thailand and shared common ancestors with FCoVs from China and Europe.

Previous studies have proposed that mutations in S genes, especially in the proteolytic sites in the S1/S2 subunit and S2 subunit, were responsible for the pathotype switch from FECV to FIPV and the development of FIP (8, 9). We also analyzed the two mutation sites for the pathotype switch. Our result showed that all Thai-FCoVs associated with asymptomatic animals or animals with unknown status (FECV) exhibited a conserved methionine at amino acid position 1,058 (M1058). On the other hand, 82.4% of Thai-FCoVs associated with FIP-suspected cases (FIPV) had a substitution M1058L, which was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Moreover, an analysis of 266 FCoV nucleotide sequences in the GenBank database showed similar results, supporting previous studies (8, 9). While this finding supports the potential link between the M1058L mutation and the transition from FECV to FIPV, other studies suggest that the M1058L mutation may be more related to systemic viral spread rather than a direct pathotype switch (36, 37). This highlights the need for further research to clarify the role of this mutation in FCoV pathogenesis.

Recombination serves as the major mechanism for the evolution and genetic diversity of RNA viruses (38). In this study, we analyzed the potential recombination events in Thai-FCoVs. The results showed that Thai-FCoV (CU27528) acquired its backbone from the Classical FCoV type I Black strain (FCoV/Black/USA/1970), and acquired a fragment in the ORF1a gene (position 4,316–11,068) from FCoV/Cat1Karlslunde/Denmark/2015. Moreover, Thai-FCoV (CU27724) is also likely to receive the majority of its genome from the Classical FCoV type I Black strain (FCoV/Black/USA/1970), where the recombination fragment in the 3′ end of ORF1b and one-third of the S gene (position 18,204–23,093) were derived from FCoV/HLJ/HRB/10/China/2016. This analysis revealed that the diverse FCoVs may have been circulating among domestic cats in Bangkok and the vicinity. Different FCoV strains can coexist and cause mixed infections under natural conditions, resulting in recombination. Thai-FCoVs may have originated from the same parental Black strain, which was isolated in the 1970s. However, Thai-FCoVs possessed different potential minor parents from Chinese and Denmark FCoVs, suggesting continuous evolution through recombination among different FCoV strains over time. The identification of FCoV recombination events in Thai-FCoVs from geographically distant strains, such as FCoVs from China, Denmark, and the USA, highlights the global spread of FCoVs in domestic cats. Recombination events can contribute to the emergence of FCoV strains with changes in virulence, transmission, and host range in the future.

In conclusion, we reported the first whole genome sequence of FCoVs in Thailand. This study provided the occurrence of FCoV in domestic cats in Thailand and identified an association between FCoV occurrence and age, sex, and seasonal variations. The predominant type of FCoV circulating in domestic cats in Thailand was FCoV type I. Thai-FCoVs were closely related to FCoVs from China and Europe. Most Thai-FIPVs exhibited amino acid mutation (M1058L), likely responsible for the pathotype switch. Recombination breakpoints were mainly observed in the ORF1ab and S genes of FCoVs. Our findings highlight the importance of routine surveillance and public education in monitoring, preventing, and controlling FCoVs in domestic cats.

Data availability statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained upon request. The nucleotide sequence data are available in the GenBank database, under accession numbers # PP901870-PP901890 and PP908788-PP908790.

Ethics statement

The animal studies were approved by the Institute for Animal Care and Use Protocol of the CU-VET, Chulalongkorn University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not obtained from the owners for the participation of their animals in this study because verbal consent was obtained from all pet owners for sample collection in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Author contributions

EP: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KC: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. CN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. EC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. YT: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. HP: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. HS: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. SC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. University supported the first author’s scholarship “the Graduate Scholarship Programme for ASEAN or Non-ASEAN Countries”. Chulalongkorn University provides financial support to the Center of Excellence for Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases in Animals (CUEIDAs) and One Health Research Cluster. The Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fund Chulalongkorn University; FF68 (HEAF68310011) supported this research. This project was partially funded by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT): NRCT Senior Scholar 2022 #N42A650553.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the “The Graduate Scholarship Programme for ASEAN or Non -ASEAN Countries,” Chulalongkorn University, for supporting the first author scholarship.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2025.1451967/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^https://www.genomedetective.com/app/typingtool/virus

2. ^https://digitalinsights.qiagen.com/products/qiagen-clc-main-workbench/

References

1. Bredenbeek, PJ, Pachuk, CJ, Noten, AF, Charité, J, Luytjes, W, Weiss, SR, et al. The primary structure and expression of the second open Reading frame of the polymerase gene of the coronavirus Mhv-A59; a highly conserved polymerase is expressed by an efficient ribosomal frameshifting mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. (1990) 18:1825–32. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.7.1825

2. Dye, C, and Siddell, SG. Genomic Rna sequence of feline coronavirus strain Fcov C1je. J Feline Med Surg. (2007) 9:202–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2006.12.002

3. Vennema, H, Poland, A, Foley, J, and Pedersen, NC. Feline infectious peritonitis viruses Arise by mutation from endemic feline enteric coronaviruses. Virology. (1998) 243:150–7. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9045

4. Tanaka, Y, Sasaki, T, Matsuda, R, Uematsu, Y, and Yamaguchi, T. Molecular epidemiological study of feline coronavirus strains in Japan using Rt-Pcr targeting Nsp14 gene. BMC Vet Res. (2015) 11:57. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0372-2

5. Wolfe, LG, and Griesemer, RA. Feline infectious peritonitis. Pathol Vet. (1966) 3:255–70. doi: 10.1177/030098586600300309

6. Robison, R, Holzworth, J, and Gilmore, C. Naturally occurring feline infectious peritonitis: signs and clinical diagnosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (1971) 158:981–6.

7. Chang, HW, Egberink, HF, Halpin, R, Spiro, DJ, and Rottier, PJ. Spike protein fusion peptide and feline coronavirus virulence. Emerg Infect Dis. (2012) 18:1089–95. doi: 10.3201/eid1807.120143

8. Licitra, BN, Millet, JK, Regan, AD, Hamilton, BS, Rinaldi, VD, Duhamel, GE, et al. Mutation in spike protein cleavage site and pathogenesis of feline coronavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. (2013) 19:1066–73. doi: 10.3201/eid1907.121094

9. Licitra, BN, Sams, KL, Lee, DW, and Whittaker, GR. Feline coronaviruses associated with feline infectious peritonitis have modifications to spike protein activation sites at two discrete positions. arXiv. (2014)

10. Herrewegh, AA, de Groot, RJ, Cepica, A, Egberink, HF, Horzinek, MC, and Rottier, PJ. Detection of feline coronavirus Rna in feces, tissues, and body fluids of naturally infected cats by reverse transcriptase Pcr. J Clin Microbiol. (1995) 33:684–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.684-689.1995

11. Herrewegh, AA, Smeenk, I, Horzinek, MC, Rottier, PJ, and de Groot, RJ. Feline coronavirus type ii strains 79-1683 and 79-1146 originate from a double recombination between feline coronavirus type I and canine coronavirus. J Virol. (1998) 72:4508–14. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4508-4514.1998

12. Benetka, V, Kübber-Heiss, A, Kolodziejek, J, Nowotny, N, Hofmann-Parisot, M, and Möstl, K. Prevalence of feline coronavirus types I and ii in cats with Histopathologically verified feline infectious peritonitis. Vet Microbiol. (2004) 99:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.07.010

13. Kummrow, M, Meli, ML, Haessig, M, Goenczi, E, Poland, A, Pedersen, NC, et al. Feline coronavirus serotypes 1 and 2: Seroprevalence and association with disease in Switzerland. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. (2005) 12:1209–15. doi: 10.1128/cdli.12.10.1209-1215.2005

14. Soma, T, Wada, M, Taharaguchi, S, and Tajima, T. Detection of Ascitic feline coronavirus Rna from cats with clinically suspected feline infectious peritonitis. J Vet Med Sci. (2013) 75:1389–92. doi: 10.1292/jvms.13-0094

15. Techangamsuwan, S, Radtanakatikanon, A, and Purnaveja, S. Molecular detection and genotype differentiation of feline coronavirus isolates from clinical specimens in Thailand. Thai J Vet Med. (2012) 42:413–22. doi: 10.56808/2985-1130.2419

16. Manasateinkij, W, Nilkumhang, P, Jaroensong, T, Noosud, J, Lekcharoensuk, C, and Lekcharoensuk, P. Occurence of feline coronavirus and feline infectious peritonitis virus in Thailand. Agric Nat Res. (2009) 43:720–6.

17. Tuanthap, S, Chiteafea, N, Rattanasrisomporn, J, and Choowongkomon, K. Comparative sequence analysis of the accessory and Nucleocapsid genes of feline coronavirus strains isolated from cats diagnosed with effusive feline infectious peritonitis. Arch Virol. (2021) 166:2779–87. doi: 10.1007/s00705-021-05188-7

18. Li, C, Liu, Q, Kong, F, Guo, D, Zhai, J, Su, M, et al. Circulation and genetic diversity of feline coronavirus type I and ii from clinically healthy and Fip-suspected cats in China. Transbound Emerg Dis. (2019) 66:763–75. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13081

19. Rozen, S, and Skaletsky, H. Primer3 on the www for general users and for biologist programmers. Bioinform Methods Prot. (1999) 132:365–86. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365

20. Tamura, K, Stecher, G, Peterson, D, Filipski, A, and Kumar, S. Mega6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. (2013) 30:2725–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197

21. Martin, DP, Varsani, A, Roumagnac, P, Botha, G, Maslamoney, S, Schwab, T, et al. Rdp5: a computer program for analyzing recombination in, and removing signals of recombination from, nucleotide sequence datasets. Virus. Evolution. (2021) 7:veaa087. doi: 10.1093/ve/veaa087

22. Lole, KS, Bollinger, RC, Paranjape, RS, Gadkari, D, Kulkarni, SS, Novak, NG, et al. Full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes from subtype C-infected Seroconverters in India, with evidence of Intersubtype recombination. J Virol. (1999) 73:152–60. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.152-160.1999

23. An, D-J, Jeoung, H-Y, Jeong, W, Park, J-Y, Lee, M-H, and Park, B-K. Prevalence of Korean cats with natural feline coronavirus infections. Virol J. (2011) 8:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-455

24. Tekelioglu, BK, Berriatua, E, Turan, N, Helps, CR, Kocak, M, and Yilmaz, H. A retrospective clinical and epidemiological study on feline coronavirus (Fcov) in cats in Istanbul, Turkey. Prev Vet Med. (2015) 119:41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.01.017

25. Pedersen, NC, Eckstrand, C, Liu, H, Leutenegger, C, and Murphy, B. Levels of feline infectious peritonitis virus in blood, effusions, and various tissues and the role of Lymphopenia in disease outcome following experimental infection. Vet Microbiol. (2015) 175:157–66. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.10.025

26. Taharaguchi, S, Soma, T, and Hara, M. Prevalence of feline coronavirus antibodies in Japanese domestic cats during the past decade. J Vet Med Sci. (2012) 74:1355–8. doi: 10.1292/jvms.11-0577

27. Bell, ET, Malik, R, and Norris, JM. The relationship between the feline coronavirus antibody titre and the age, breed, gender and health status of Australian cats. Aust Vet J. (2006) 84:2–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2006.tb13114.x

28. Kiss, I, Kecskeméti, S, Tanyi, J, Klingeborn, B, and Belák, S. Prevalence and genetic pattern of feline coronaviruses in urban cat populations. Vet J. (2000) 159:64–70. doi: 10.1053/tvjl.1999.0402

29. Sharif, S, Arshad, SS, Hair-Bejo, M, Omar, AR, Zeenathul, NA, and Hafidz, MA. Prevalence of feline coronavirus in two cat populations in Malaysia. J Feline Med Surg. (2009) 11:1031–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2009.08.005

30. Pesteanu-Somogyi, LD, Radzai, C, and Pressler, BM. Prevalence of feline infectious peritonitis in specific cat breeds. J Feline Med Surg. (2006) 8:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2005.04.003

31. Worthing, KA, Wigney, DI, Dhand, NK, Fawcett, A, McDonagh, P, Malik, R, et al. Risk factors for feline infectious peritonitis in Australian cats. J Feline Med Surg. (2012) 14:405–12. doi: 10.1177/1098612x12441875

32. Melnyk, V, Martyniuk, O, Bodnar, A, and Bodnar, M. Epizootological features of coronavirus infection in cats. Ukrainian J Vet Sci. (2022) 13:334–340. doi: 10.31548/ujvs.13(1).2022.52-60

33. Song, X-L, Li, W-F, Shan, H, Yang, H-Y, and Zhang, C-M. Prevalence and genetic variation of the M, N, and S2 genes of feline coronavirus in Shandong Province, China. Arch Virol. (2023) 168:227. doi: 10.1007/s00705-023-05816-4

34. Jaimes, JA, Millet, JK, Stout, AE, André, NM, and Whittaker, GR. A tale of two viruses: the distinct spike glycoproteins of feline coronaviruses. Viruses. (2020) 12:83. doi: 10.3390/v12010083

35. Pedersen, NC. A review of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection: 1963-2008. J Feline Med Surg. (2009) 11:225–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2008.09.008

36. Porter, E, Tasker, S, Day, MJ, Harley, R, Kipar, A, Siddell, SG, et al. Amino acid changes in the spike protein of feline coronavirus correlate with systemic spread of virus from the intestine and not with feline infectious peritonitis. Vet Res. (2014) 45:49. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-45-49

37. Jähne, S, Felten, S, Bergmann, M, Erber, K, Matiasek, K, Meli, ML, et al. Detection of feline coronavirus variants in cats without feline infectious peritonitis. Viruses. (2022) 14:1671. doi: 10.3390/v14081671

Keywords: cats, characterization, feline coronavirus, whole genome sequence, Thailand

Citation: Phyu EM, Charoenkul K, Nasamran C, Chamsai E, Thaw YN, Phyu HW, Soe HW, Chaiyawong S and Amonsin A (2025) Whole genome characterization of feline coronaviruses in Thailand: evidence of genetic recombination and mutation M1058L in pathotype switch. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1451967. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1451967

Edited by:

Tomomi Takano, Kitasato University, JapanReviewed by:

Manos Christos Vlasiou, University of Nicosia, CyprusSai Narayanan, Oklahoma State University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Phyu, Charoenkul, Nasamran, Chamsai, Thaw, Phyu, Soe, Chaiyawong and Amonsin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alongkorn Amonsin, QWxvbmdrb3JuLmFAY2h1bGEuYWMudGg=

†ORCID: Alongkorn Amonsin, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6769-4906

Eaint Min Phyu

Eaint Min Phyu Kamonpan Charoenkul1,3

Kamonpan Charoenkul1,3 Hnin Wai Phyu

Hnin Wai Phyu Han Win Soe

Han Win Soe Alongkorn Amonsin

Alongkorn Amonsin