95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Vet. Sci. , 25 September 2024

Sec. Animal Nutrition and Metabolism

Volume 11 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2024.1455029

This article is part of the Research Topic Crosslinking of feed nutrients, microbiome and production in ruminants View all 16 articles

Rui Zhang1,2,3

Rui Zhang1,2,3 Liwa Zhang1,2,3

Liwa Zhang1,2,3 Xuejiao An1,2,3

Xuejiao An1,2,3 Jianye Li1,2,3

Jianye Li1,2,3 Chune Niu1,2,3

Chune Niu1,2,3 Jinxia Zhang4

Jinxia Zhang4 Zhiguang Geng4

Zhiguang Geng4 Tao Xu1,2,3,5

Tao Xu1,2,3,5 Bohui Yang1,2,3

Bohui Yang1,2,3 Zhenfei Xu1,2,3*

Zhenfei Xu1,2,3* Yaojing Yue1,2,3*

Yaojing Yue1,2,3*Hybridization can substantially improve growth performance. This study used metagenomics and metabolome sequencing to examine whether the rumen microbiota and its metabolites contributed to this phenomenon. We selected 48 approximately 3 month-old male ♂Hu × ♀Hu (HH, n = 16), ♂Poll Dorset × ♀Hu (DH, n = 16), and ♂Southdown × ♀Hu (SH, n = 16) lambs having similar body weight. The sheep were fed individually under the same nutritional and management conditions for 95 days. After completion of the trial, seven sheep close to the average weight per group were slaughtered to collect rumen tissue and content samples to measure rumen epithelial parameters, fermentation patterns, microbiota, and metabolite profiles. The final body weight (FBW), average daily gain (ADG), and dry matter intake (DMI) values in the DH and SH groups were significantly higher and the feed-to-gain ratio (F/G) significantly lower than the value in the HH group; additionally, the papilla height in the DH group was higher than that in the HH group. Acetate, propionate, and total volatile fatty acid (VFA) concentrations in the DH group were higher than those in the HH group, whereas NH3-N concentration decreased in the DH and SH groups. Metagenomic analysis revealed that several Prevotella and Fibrobacter species were significantly more abundant in the DH group, contributing to an increased ability to degrade dietary cellulose and enrich their functions in enzymes involved in carbohydrate breakdown. Bacteroidaceae bacterium was higher in the SH group, indicating a greater ability to digest dietary fiber. Metabolomic analysis revealed that the concentrations of rumen metabolites (mainly lysophosphatidylethanolamines [LPEs]) were higher in the DH group, and microbiome-related metabolite analysis indicated that Treponema bryantii and Fibrobacter succinogenes were positively correlated with the LPEs. Moreover, we found methionine sulfoxide and N-methyl-4-aminobutyric acid were characteristic metabolites in the DH and SH groups, respectively, and are related to oxidative stress, indicating that the environmental adaptability of crossbred sheep needs to be further improved. These findings substantially deepen the general understanding of how hybridization promotes growth performance from the perspective of rumen microbiota, this is vital for the cultivation of new species and the formulation of precision nutrition strategies for sheep.

Hybridization is an important method of breeding sheep that can produce heterosis, resulting in a new breed that is stronger or performs better than its parents (1). Binary hybridization in the cultivation of new varieties of mutton sheep has been frequently reported in China (2). Even though three-way crossbreeding is commonly used in pig production and for developing new breeds (3, 4), relevant research is still in the early stages of selecting suitable species on mutton sheep industry (5). Compared with the former, the latter could effectively utilize the heterosis of three hybrid individuals, producing a significantly stronger effect. Hu is a native sheep breed with perennial estrus, high fecundity, high lactation, good parenting traits, and strong adaptability; therefore, they are often used as crossbreeding ewes for mutton sheep, however, their meat production rate and dressing percentage are unsatisfactory (6, 7). Poll Dorset is native to Australia and New Zealand, has the characteristics of fast growth, early maturity, and perennial estrus, and is considered the main parent for hybridization in the Chinese sheep breeding industry (8). Southdown is considered the best breed for meat quality in the United Kingdom due to its ideal meat structure, early maturity, easy breeding, good carcass quality, and dressing percentage > 55% (9, 10). Southdown and Poll Dorset are small sheep species that grow rapidly in the early stages and are suitable for producing high-grade fat lambs, which aligns with the current market demand for mutton in China. Therefore, we attempted to cultivate a new breed of sheep by using Poll Dorset and Southdown as sires, crossing them with Hu sheep, and monitoring the production traits of the F1 generation.

Growth performance is the main selection trait for breeding new sheep varieties. The rumen microbiota is associated with animal growth and health (11). The rumen is colonized by bacteria, protozoa, archaea, fungi, and viruses, which degrade complex plant fibers and polysaccharides to produce volatile fatty acids (VFAs), microbial proteins, and vitamins, in turn providing nutrients to meet host requirements for maintenance and growth (12, 13). Although diet plays a major role in shaping the gastrointestinal microbiota, recent evidence has revealed host genetics to be an important factor in determining the gut microbiota composition in cattle (13–15). However, research on the effects of host genetics on the rumen microbiota composition of hybridized sheep is limited.

Therefore, in this study, we hypothesized that rumen microbiota composition and function in sheep are affected by host genetics, affecting growth performance in turn. We assessed the rumen microbiota and metabolite profiles of different hybridized sheep raised in the same farm environment, aiming to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms from the perspective of rumen microbiota and thus provide a theoretical and practical basis for improving the growth performance of hybridized sheep.

This study was conducted at the Qinghuan Mutton Sheep Breeding Company in Huanxian County, Gansu, China from October 2022 to January 2023. The experimental design, procedures, and methods were approved by the Animal Administration and Ethics Committee of the Lanzhou Institute of Husbandry and Pharmaceutical Science of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science under permission number 2022–018 and followed the Chinese standards for the use and care of animals. Forty-eight approximately 3 month-old male ♂Hu × ♀Hu (HH, n = 16), ♂Poll Dorset × ♀Hu (DH, n = 16), and ♂Southdown × ♀Hu (SH, n = 16) lambs were selected and raised in a single pen under the same nutritional and management conditions for 95 days (including a 15 day pre-test period). Hu sheep were chosen from 216 approximately 3 month-old male lambs with an average body weight of 22.98 ± 6.37 kg, and F1 generation sheep of similar body weight were selected. Poll Dorset and Southdown sires (aged 31 months) generated from embryo transplantation and Hu sires (aged 24 months) were crossed with Hu ewes (parity one or two) by estrus synchronization and artificial insemination. The offspring (one, in case of twins) were confirmed to stem from different fathers. All sheep were fed the same total mixed ratio composed of oat hay (6.08% DM), Leymus chinensis (13.04% DM), corn silage (13.53% DM), corn (32.78% DM), megalac (6.08% DM) and grain mixtures (28.49% DM) twice daily at 08:00 and 15:00 (Supplementary Table S1). During the experimental period, all animals had access to feed and water ad libitum. Feed intake was recorded daily based on the feed offered and refusals to calculate the average dry matter intake (DMI). Body weight was recorded every 20 d using a digital livestock scale (TCS Electronic Platform Scale, Rongcheng, China) to calculate the average daily gain (ADG) and feed-to-gain ratio (F/G).

At the end of the experiment, seven sheep close to the average weight per group were selected and fasted for 12 h before harvesting. Harvesting was based on standard commercial procedures, individually restrained, exsanguinated, skinned, and gutted. Rumen tissue samples of approximately 2 cm × 2 cm were carefully separated from the left dorsal sac to fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) staining. Then, two portions of 5 mL rumen content were collected from each animal, transferred into a sterile tube, immediately frozen using liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for DNA and metabolite extraction. Another 15 mL rumen content was sampled and stored in a sterilized container at −20°C for evaluation of fermentation parameters. The rumen contents of all animals were collected from the left dorsal sac as a mixture of liquid and solid components. All samples were collected within 30 min of slaughter.

Rumen epithelial parameters, including papilla height, papilla width, and muscle thickness, were obtained using the H&E staining technique (16). The fixed rumen tissues were dehydrated in alcohol, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Then the cooling concretionary samples were sectioned at 5 μm thickness and mounted on glass slides. Paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed with xylene, passed through a graded ethanol series to remove the xylene, rinsed with distilled water, and stained with H&E. Subsequently, the paraffin was sealed with neutral gum after dehydration and immediately examined. Finally, two digital slides were acquired from each animal using a Slide Viewer device (3D HISTECH Ltd.) at two-fold magnification; then, five papillae (excluding damaged ones) were chosen randomly from each digital slide to measure papilla height using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States). Within those papillae measured for height, three different regions (apical, middle, and basal) were identified to measure papilla width. Each digital slide was divided into five equal parts to measure muscle thickness.

The pH of the rumen was measured immediately after the sheep were slaughtered using an Ark Technology PHS-10 portable acidity meter (Chengdu, China). The NH3-N concentration was determined by colorimetry. Briefly, 2 g of rumen content was accurately weighed and mixed with deionized water at a 1:5 ratio. The mixed solution was shaken for 1 h at 105 r/min and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C for 20 min. The supernatant was then passed through a 0.45 μm polymer fiber filter membrane and stored for further analysis. Subsequently, the NH3-N concentration was measured using a kit (Biosino Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and a microplate reader (DR-200BS; Hiwell-Diatek, Wuxi, China). VFA concentrations were measured as previously described (16). Briefly, rumen contents were centrifuged at 5,400 rpm for 10 min. We subsequently uniformly mixed 1 mL of the resulting supernatant and a 0.2 mL 25% metaphosphate solution containing 2-ethylbutyric acid as an internal standard in a new centrifuge tube. This reaction tube was then immersed in an ice bath (30 min) and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for another 10 min. The supernatant was passed through a 0.22 μm organic phase filter membrane and stored in 2 mL bottles for subsequent analysis. A gas chromatograph (GC 7890A; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States) fitted with an AT-FFAP capillary column (50 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 μm; Agilent Technologies) was used to determine VFA concentrations. The column temperature was maintained at 60°C for 1 min, raised by 5°C/min to 115°C, and increased by 15°C/min to 180°C. Notably, the detector and injector temperatures were 260°C and 250°C, respectively.

Total genomic DNA was extracted from rumen content sample using the E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit (Omega Biotek, Norcross, GA, United States). The DNA concentration and purity were determined using TBS-380 mini-fluorometer (Promega, Madison, WI, United States) and NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States), respectively. The DNA was fragmented to approximately 400 bp for paired-end library construction using a Covaris M220 (Gene Company Limited, Hong Kong, China). Metagenome libraries sequencing was performed using an Illumina NovaSeq 6,000 platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, United States).

Quality control of the metagenomic sequence reads was performed using the Fastp software (version 0.20.0) to trim the 3′-end and 5′-end of reads, cut low-quality bases, and remove short reads and “N” records (17). The quality-filtered reads were then aligned to the Ovis aries reference genome using BWA v 0.7.1 to filter out the host DNA (18). The remaining reads were assembled using Multiple Megahit (version 1.1.2) (19), and contigs with lengths ≥300 bp were selected as the final assembling result for the prediction of open reading frames (ORF) using MetaGene v 0.3.38 (20). Non-redundant contigs were identified using CD-HIT with 95% sequence identity and 90% coverage (21). Original sequencing reads were mapped to predicted genes to estimate their abundance using SOAPAligner v. 2.21 (22). Subsequently, the non-redundant gene catalog was aligned to the NCBI non-redundant protein sequence database using BLASTP (version 2.2.28+) to obtain taxonomic annotations and species abundances (23). Taxonomic profiles were conducted at domain, phylum, genus and species levels, with relative abundances calculated. The PCoA based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrices at domain level was performed. Bacteria with a relative abundance >0.01% and archaea with a relative abundance >0.001% were analyzed. Finally, a BLAST search (version 2.2.28+) with an optimization criterion cutoff of 1e−5 was annotated against the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (24). Carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZyme) annotation was conducted using hmmscan1 against CAZy database version 5.02 with an e-value cutoff of 1e−5.

Rumen sample metabolite extraction was based on previously published procedures (16). The metabolome of the rumen content was analyzed by ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC; Shim-pack UFLC Shimadzu CBM30A; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS, QTRAP® 6,500+, SCIEX, Framingham, MA, United States) (25). After obtaining the liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry data of the samples, the extracted ion chromatographic peaks of all metabolites were integrated using MultiQuant software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States). The chromatographic peaks of the metabolites in different samples were corrected using integration (26). The relative concentrations of rumen metabolites were screened by fold change (FC) (FC ≥ 2 or FC ≤ 0.5) and variable importance in projection (VIP) (VIP ≥ 1) to identify the different metabolites. Identified metabolites were annotated using the KEGG compound database (27).

All data were checked for normality and outliers using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) before any statistical analyses were conducted. One-way ANOVA and LSD post-hoc test was used to analyze the data of growth performance as well as rumen epithelial and fermentation parameters. Spearman’s correlation test was used for correlation analyses. Statistical significance was set to p < 0.05. GraphPad Prism version 8.5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, United States) drew the statistical maps.

A summary of the growth performance data is presented in Table 1. The initial body weight (IBM) did not differ significantly among the three groups (p = 0.156). The DH and SH groups exhibited greater ADG than did the HH group (p = 0.008) but did not differ from each other. The final body weight (FBW) was greater in the DH and SH groups than in the HH group (p < 0.001). DMI was also greater in the DH and SH groups, resulting in a lower F/G value than that in the HH group (p = 0.013).

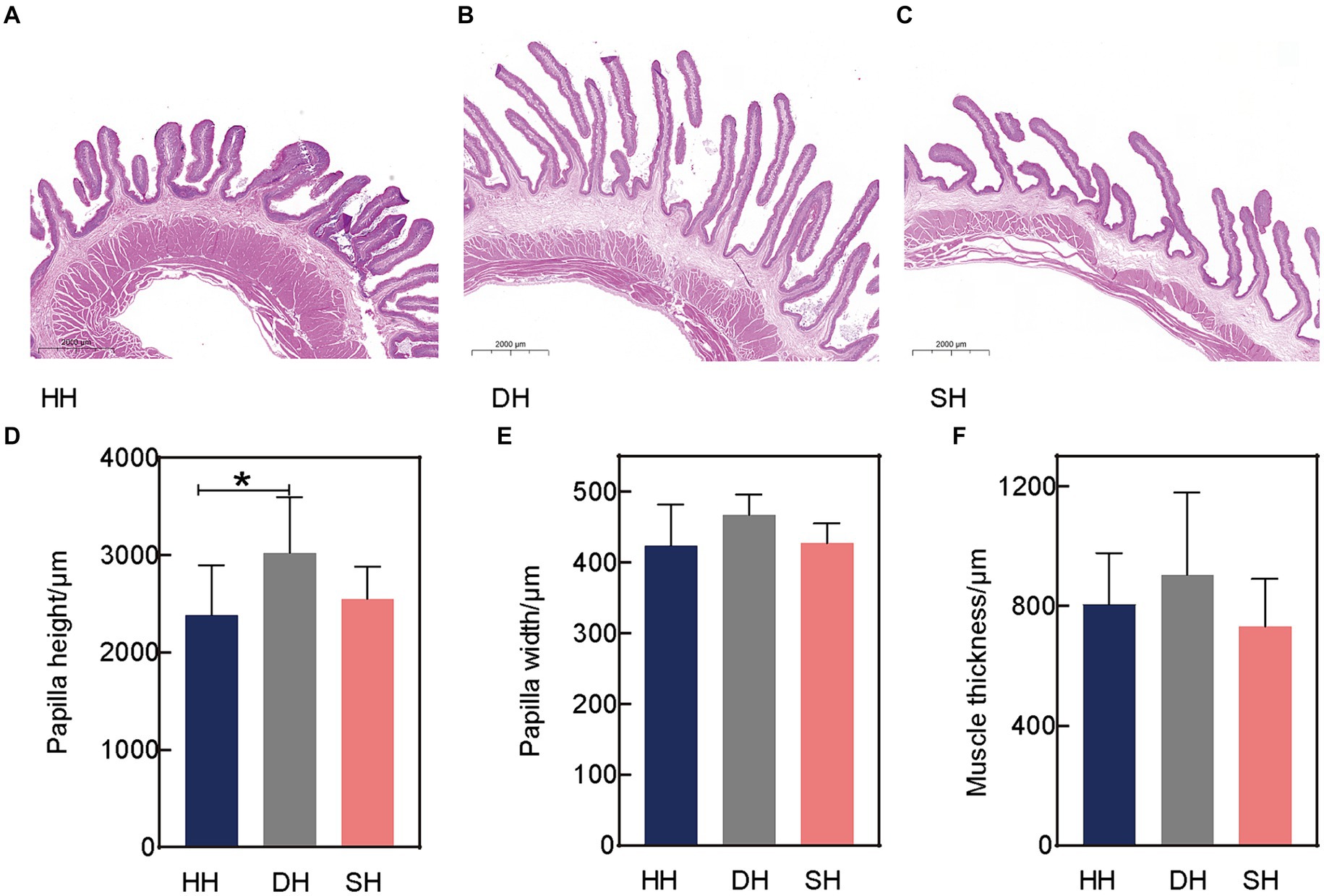

Three rumen epithelial development indices, including papilla height, papilla width, and muscle thickness, were measured using H&E staining (Figures 1A–C). Hybridization had no effect on rumen papilla width or muscle thickness (p > 0.128; Figures 1E,F). The largest difference was observed in papilla height, the DH group exhibited a greater height than the HH group (p = 0.046; Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Hybridization promoted rumen epithelial development in Hu sheep. (A) Rumen epithelium hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining in the HH group. (B) Rumen epithelium H&E staining in the DH group. (C) Rumen epithelium H&E staining in the SH group. (D) Rumen papilla height. (E) Rumen papilla width. (F) Muscle thickness. n = 7 individuals/group; * indicates p < 0.05.

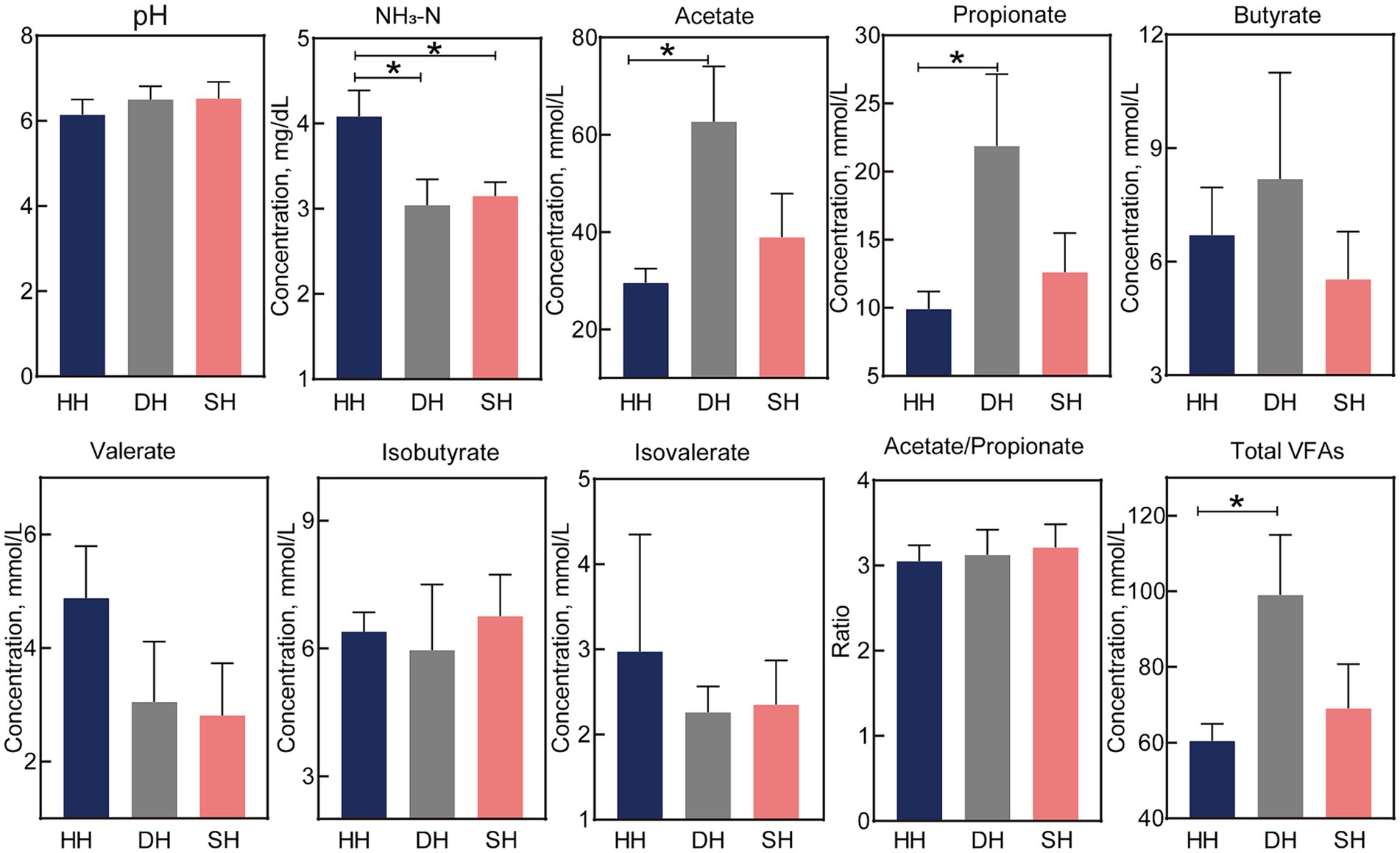

The NH3-N concentration was significantly lower in the SH and DH groups than in the HH group (p = 0.023; Figure 2). Acetate and propionate concentrations in the DH group were significantly higher than those in the HH group (p < 0.041), resulting in higher total VFAs (p = 0.048). The pH value as well as butyrate, valerate, isobutyrate, isovalerate, and acetate/propionate concentrations remained unchanged.

Figure 2. Hybridization altered rumen fermentation parameters in Hu sheep. n = 7 individuals/group; * indicates p < 0.05.

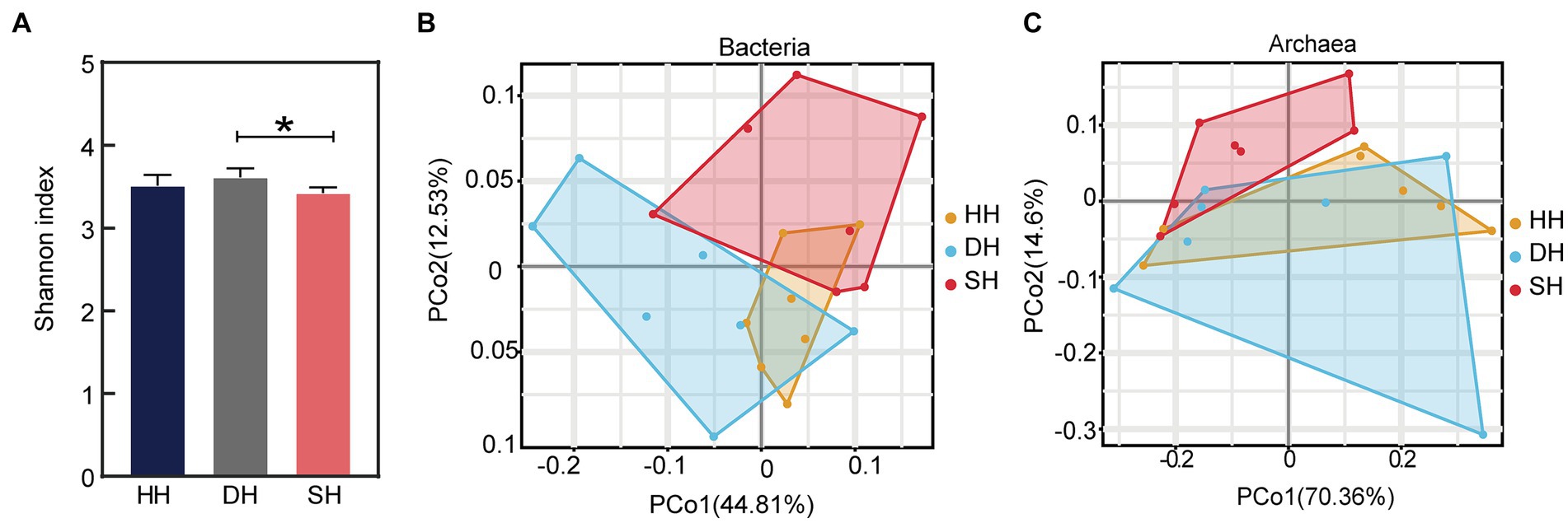

Metagenome sequencing generated a total of 1,443,800,424 raw reads, with an average of 68,752,401 ± 5,953,935 reads (mean ± SD) per sample. After quality control and removing host genes, a total of 1,284,320,034 reads were retained, or 61,158,097 ± 5,264,516 per sample. After assembly, a total of 19,962,258 contigs were generated (with an average N50 length of 825 ± 60), with 950,584 ± 91,196 per sample (Supplementary Table S2). The results indicated that the sequencing data were credible and could be used for subsequent bioinformatics investigations. The α-diversity analysis using Kruskal–Wallis Test revealed that the Shannon index was significantly increased in the DH group compared to that in the SH group (p = 0.016; Figure 3A), while the Ace and Simpson indices did not differ among the three groups (Supplementary Table S3). The rumen metagenome comprised 97.18% bacteria (591,631,456 sequences), 1.60% archaea (9,758,146 sequences), 0.43% eukaryotes (2,601,458 sequences), and 0.78% viruses (4,731,066 sequences). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) at the domain level revealed a separation between the HH and DH groups and HH and SH groups based on bacteria (Figure 3B), as well as between the SH and HH groups and SH and DH groups based on archaea (Figure 3C), no separation was observed based on eukaryotes or viruses (Supplementary Figure S1). Therefore, the comparative analysis of rumen microbial taxa among the three groups focused only on bacteria and archaea.

Figure 3. Alpha diversity index and microbial compositional profiles of rumen sample principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). (A) Alpha diversity as presented by the Shannon index. (B) PCoA based on bacterial domain. (C) PCoA based on archaeal domain. n = 7 individuals/group; * indicates p < 0.05.

The dominant bacterial phyla in the rumen were Bacteroidetes (HH: 44.39%; DH: 44.87%; SH: 45.53%) and Firmicutes (HH: 42.72%; DH: 40.33%; SH: 43.24%), followed by Spirochaetes (HH: 2.81%; DH: 4.64%; SH: 2.55%); however, no significant differences were found among the three groups (p > 0.05; Supplementary Figure S2A). A total of 5,413 genera were identified. Among them, unclassified o Bacteroidales (HH: 19.53%; DH: 14.50%; SH: 20.21%), Prevotella (HH: 14.31%; DH: 19.93%; SH: 14.87%), and unclassified c Clostridia (HH: 8.33%; DH: 7.03%; SH: 8.83%) were the predominant bacteria in the rumen samples (Supplementary Figure S2B). A total of 20,943 species were found, among which the dominant bacteria were the Bacteroidales bacterium (HH: 19.35%; DH: 14.42%; SH: 20.00%), Prevotella sp. (HH: 12.37%; DH: 16.29%; SH: 12.71%) and Clostridia bacterium (HH: 8.33%; DH: 7.03%; SH: 8.83%) (Supplementary Figure S2C).

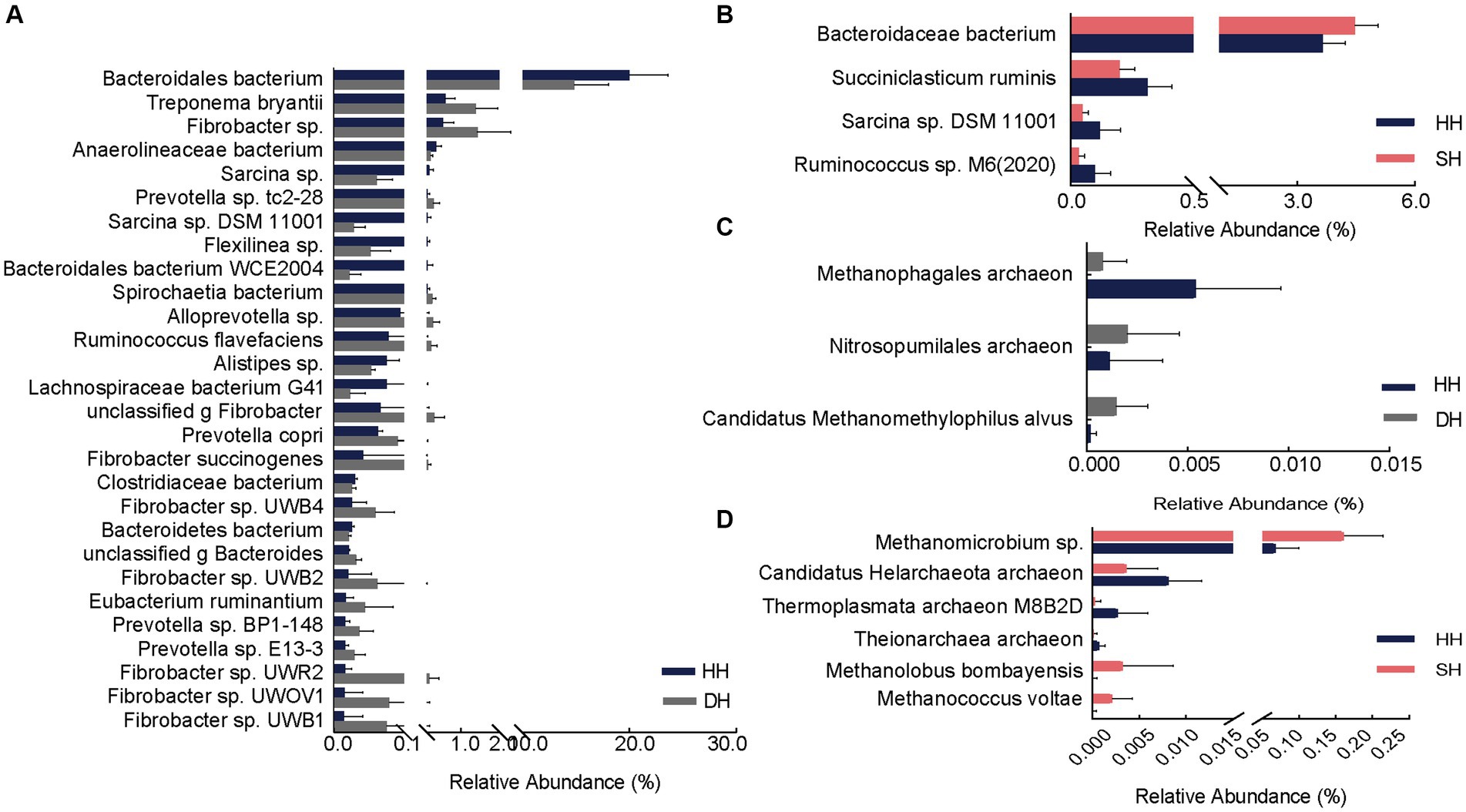

Differential analysis revealed a total of 28 significantly different bacterial species between the DH and HH groups. Among them, 18 exhibited significantly higher abundances in the DH group. The relative abundances of Treponema bryantii, Fibrobacter sp., Prevotella sp. tc2-28, Spirochaetia bacterium, and Alloprevotella sp. were the top five most significantly increased. Additionally, the relative abundances of Prevotella copri, Prevotella sp. BP1-148, Prevotella sp. E13-3, Fibrobacter succinogenes, Fibrobacter sp. UWB4, Fibrobacter sp. UWB2, Fibrobacter sp. UWR2, Fibrobacter sp. UWOV1, and Fibrobacter sp. UWB1 was also significantly increased in the DH group. Ten bacteria were significantly enriched in the HH group, mainly Bacteroidales bacterium, Anaerolineaceae bacterium, Sarcina sp., Sarcina sp. DSM 11001, and Flexilinea sp. (Figure 4A). Compared to levels in the HH group, only one bacterium (Bacteroidaceae bacterium) was significantly enriched in the SH group, whereas three (Succiniclasticum ruminis, Sarcina sp. DSM 11001, and Ruminococcus sp. M6(2020)) were significantly more abundant in the HH group (Figure 4B). When compared to levels in the DH group, 19 bacterial abundances were significantly different, including six (Bacteroidales bacterium, Pyramidobacter sp., Clostridiaceae bacterium, Bacteroidales bacterium WCE2004, Bacteroidetes bacterium, and unclassified p Firmicutes) with higher abundances in the SH group and 13 (Treponema sp., Acidaminococcaceae bacterium, Fibrobacter sp., Treponema bryantii, Schwartzia sp., Prevotella sp.tc2-28, Spirochaetia bacterium, Schwartzia succinivorans, Fibrobacter succinogenes, Fibrobacter sp. UWB2, Fibrobacter sp. UWB3, Eubacterium ruminantium, and Fibrobacter sp. UWB12) with higher abundances in the DH group (Supplementary Figure S3A).

Figure 4. Differential rumen bacterial and archaeal species. (A) Significantly different bacterial species between the HH and DH groups. (B) Significantly different bacterial species between the HH and SH groups. (C) Significantly different archaeal species between the HH and DH groups. (D) Significantly different archaeal species between the HH and SH groups. n = 7 individuals/group.

At the species level, the abundance of two archaeal species (Nitrosopumilales archaeon and Candidatus Methanomethylophilus alvus) was significantly enriched and one (Methanophagales archaeon) significantly decreased in the DH group compared to levels in the HH group (Figure 4C). The abundance of three archaea (Methanomicrobium sp., Methanolobus bombayensis, and Methanococcus voltae) was significantly enriched and three (Candidatus Helarchaeota archaeon, Thermoplasmata archaeon M8B2D, and Theionarchaea archaeon) decreased in the SH group compared to levels in the HH group (Figure 4D). When compared with levels in the DH group, the abundances of Methanocorpusculum sp. and Candidatus Altiarchaeales archaeon WOR SM1 86-2 were significantly higher, whereas the abundances of Candidatus Methanomethylophilaceae archaeon, Candidatus Methanomethylophilus sp., Methanomicrobium sp., Methanobacterium sp. ERen5, unclassified g Methanobacterium, and Methanolobus bombayensis were significantly lower than those in the SH group (Supplementary Figure S3B).

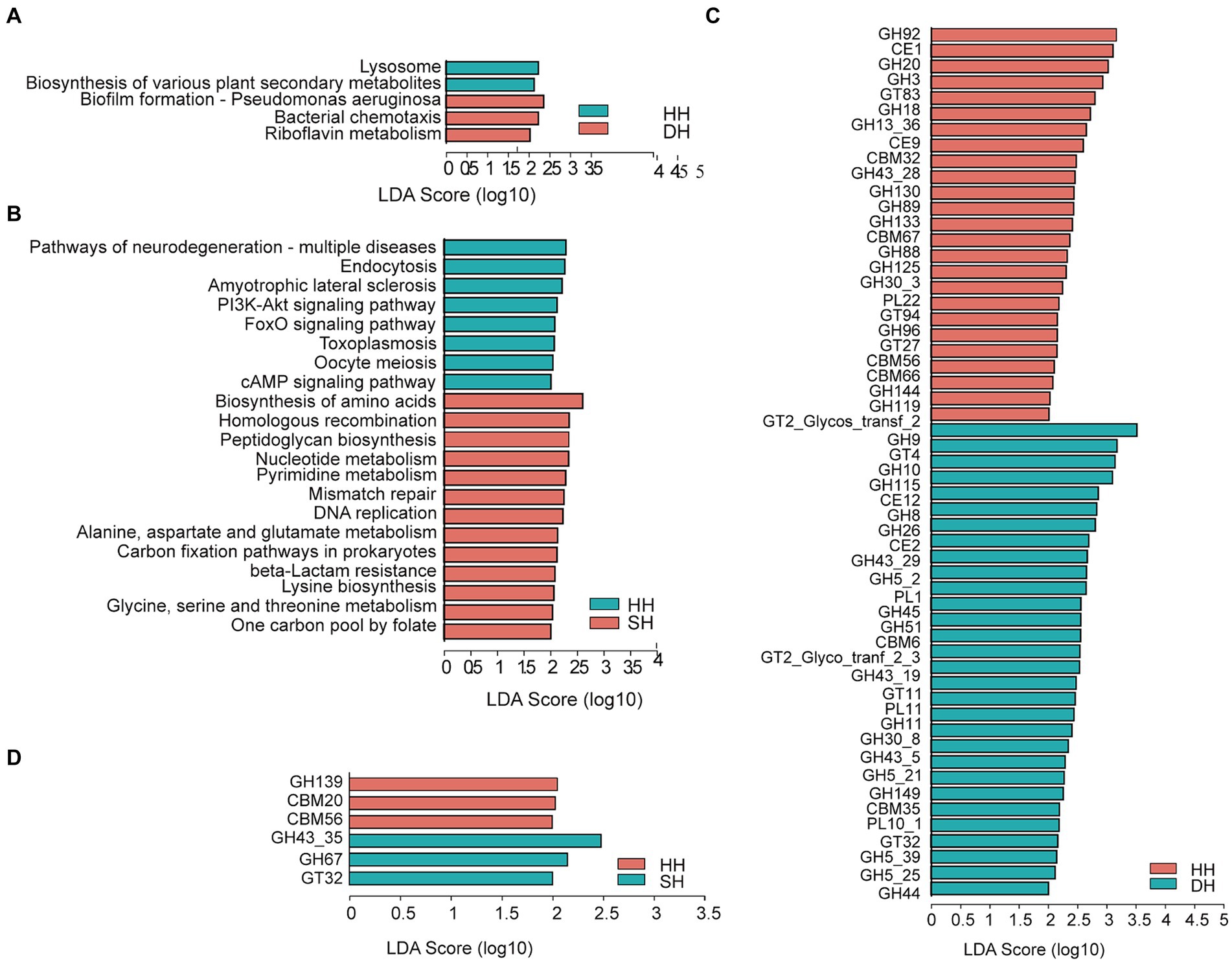

The functions of the rumen microbiome were determined using KEGG profiles and genes encoding CAZymes. For KEGG profiles, a total of six pathways were annotated at the first level among the three groups, including “metabolism” (HH: 49.78%; DH: 50.16%; SH: 50.85%), “genetic information processing” (HH: 16.78%; DH: 16.71%; SH: 17.05%), “environmental information processing” (HH: 12.92%; DH: 12.98%; SH: 12.77%), “cellular processes” (HH: 9.71%; DH: 9.68%; SH: 9.42%), “human diseases” (HH: 6.67%; DH: 6.47%; SH: 6.22%) and “organismal systems” (HH: 4.15%; DH: 4.00%; SH: 3.70%). At the second level, we obtained only one profile, “metabolism of cofactors and vitamins,” that was significantly enriched in the DH group compared to level in the HH groups (Supplementary Figure S4A). Nine KEGG profiles were significantly enriched in the SH group compared to levels in the HH group, among them, “replication and repair,” “nucleotide metabolism,” and “biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites” were the most dominant (Supplementary Figure S4B). Seven KEGG profiles were significantly different between the DH and SH groups. “glycan biosynthesis and metabolism” and “nucleotide metabolism” were the most enriched in the SH group, while “signal transduction” was enriched in the DH group (Supplementary Figure S4C). When comparing the identified KEGG pathways at the third level, “biofilm formation—pseudomonas aeruginosa,” “bacterial chemotaxis,” and “riboflavin metabolism” were significantly enriched in the DH group, while the “lysosome” and “biosynthesis of various plant secondary metabolites” pathways were significantly decreased compared to levels in the HH group (Figure 5A). A total of 21 differential pathways were identified in the HH and SH groups. Among them, 13 were significantly enriched in the SH group, mainly including “biosynthesis of amino acids,” “homologous recombination,” “peptidoglycan biosynthesis,” “nucleotide metabolism,” “pyrimidine metabolism,” “mismatch repair,” “DNA replication,” “alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism,” “carbon fixation pathways in prokaryotes,” “beta-lactam resistance,” “lysine biosynthesis,” “glycine, serine and threonine metabolism,” and “one carbon pool by folate”; whereas eight were significantly enriched in the HH group (Figure 5B). Twenty differential pathways were identified in the DH and SH groups. Among them, five were significantly enriched in the DH group and 15 in the SH group. “Carbon metabolism,” “aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis,” “nucleotide metabolism,” “pyrimidine metabolism,” and “other glycan degradation” were the top five pathways the most significantly enriched in the SH group (Supplementary Figure S5A).

Figure 5. Differential rumen microbiome functions. (A) Significantly differential KEGG functions at the third level between the HH and DH groups. (B) Significantly differential KEGG functions at the third level between the HH and SH groups. (C) Significantly differential CAZy functions at the family level between the HH and DH groups. (D) Significantly differential CAZy functions at the family level between the HH and SH groups. Significant differences were tested by linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis, with linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score > 2 and p < 0.05. n = 7 individuals/group.

For the CAZyme profiles, 55 differentially expressed genes encoding CAZymes were identified between the HH and DH groups at the family level (Figure 5C). Among them, 23 involved in the breakdown of carbohydrates (including cellulose, hemicellulose, starch, protein, and lignin) were enriched in the DH group (2 carbohydrate esterases [CEs], 18 glycoside hydrolases [GHs], and 3 polysaccharide lyases [PLs]), and 18 in the HH group (2 CEs, 15 GHs, and 1 PL). Five glycosyltransferases (GTs) involved in carbohydrate synthesis were enriched in the DH group, while three were enriched in the HH group. Several non-catalytic CAZymes were involved in the degradation of complex carbohydrates as parts of carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs), including two enriched in the DH group and four in the HH group. A total of six differentially expressed genes encoding CAZymes were observed between the HH and SH groups (Figure 5D). Among these, 2 GHs and 1 GT were enriched in the SH group, whereas 1 GH and 2 CBMs were enriched in the HH group. We obtained 41 differential genes encoding CAZymes between the DH and SH groups (Supplementary Figure S5B). Among those involved in carbohydrate breakdown, 21 were enriched in the SH group (2 CEs, 15 GHs, 2 GLs, and 2 PLs), whereas 12 were enriched in the DH group (2 CEs, 8 GHs, and 2 PLs). Additionally, 3 GTs were enriched in the DH group.

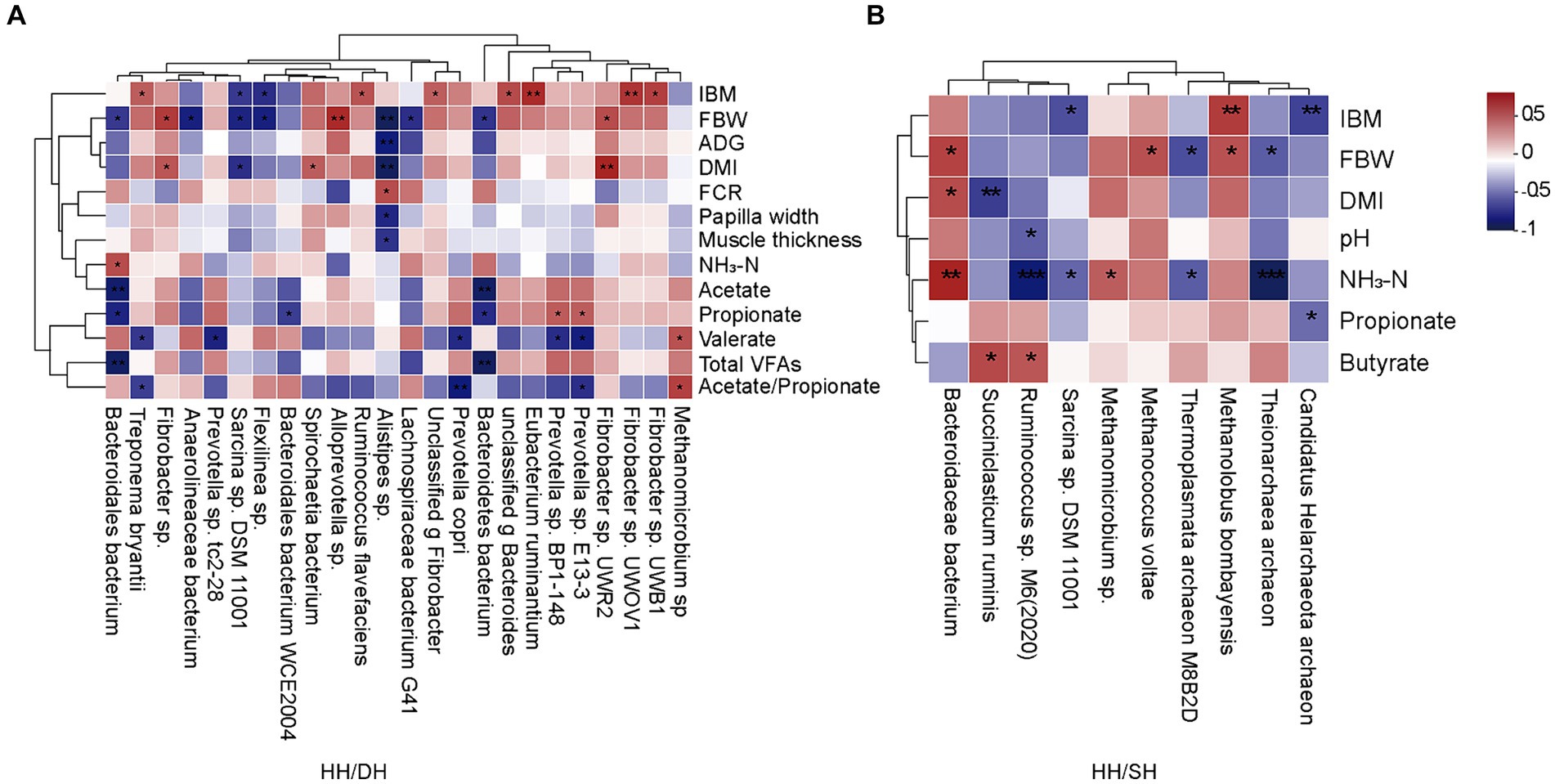

Spearman’s correlation coefficient analysis identified correlations between growth performance, rumen epithelial parameters, fermentation parameters, and significantly different microbiomes (|r| > 0.5; p < 0.05). When we compared the HH and DH groups, the relative abundance of Alloprevotella sp. was positively correlated with FBW, as well as the relative abundance of Fibrobacter sp. UWR2 and Fibrobacter sp. were positively correlated with DMI, and the relative abundance of Alistipes sp. was negatively correlated with FBW, ADG, and DMI (Figure 6A). When we compared the HH and SH groups, the relative abundance of Bacteroidaceae bacterium was positively correlated with FBW and DMI; however, the relative abundances of Ruminococcus sp. M6(2020) and Theionarchaea archaeon were negatively correlated with NH3-N concentration (Figure 6B). When we compared the DH and SH groups, we found that Pyramidobacter sp. was negatively correlated to acetate, propionate, and butyrate concentrations, the relative abundances of Candidatus Methanomethylophilus sp. and Candidatus Methanomethylophilaceae archaeon were negatively related to acetate, propionate, and total VFA concentrations (Supplementary Figure S6).

Figure 6. Correlation analysis between growth performance, rumen epithelial parameters, fermentation parameters, and significantly different microbiomes. (|r| > 0.5). (A) Between the HH and DH groups. (B) Between the HH and SH groups. n = 7 individuals/group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

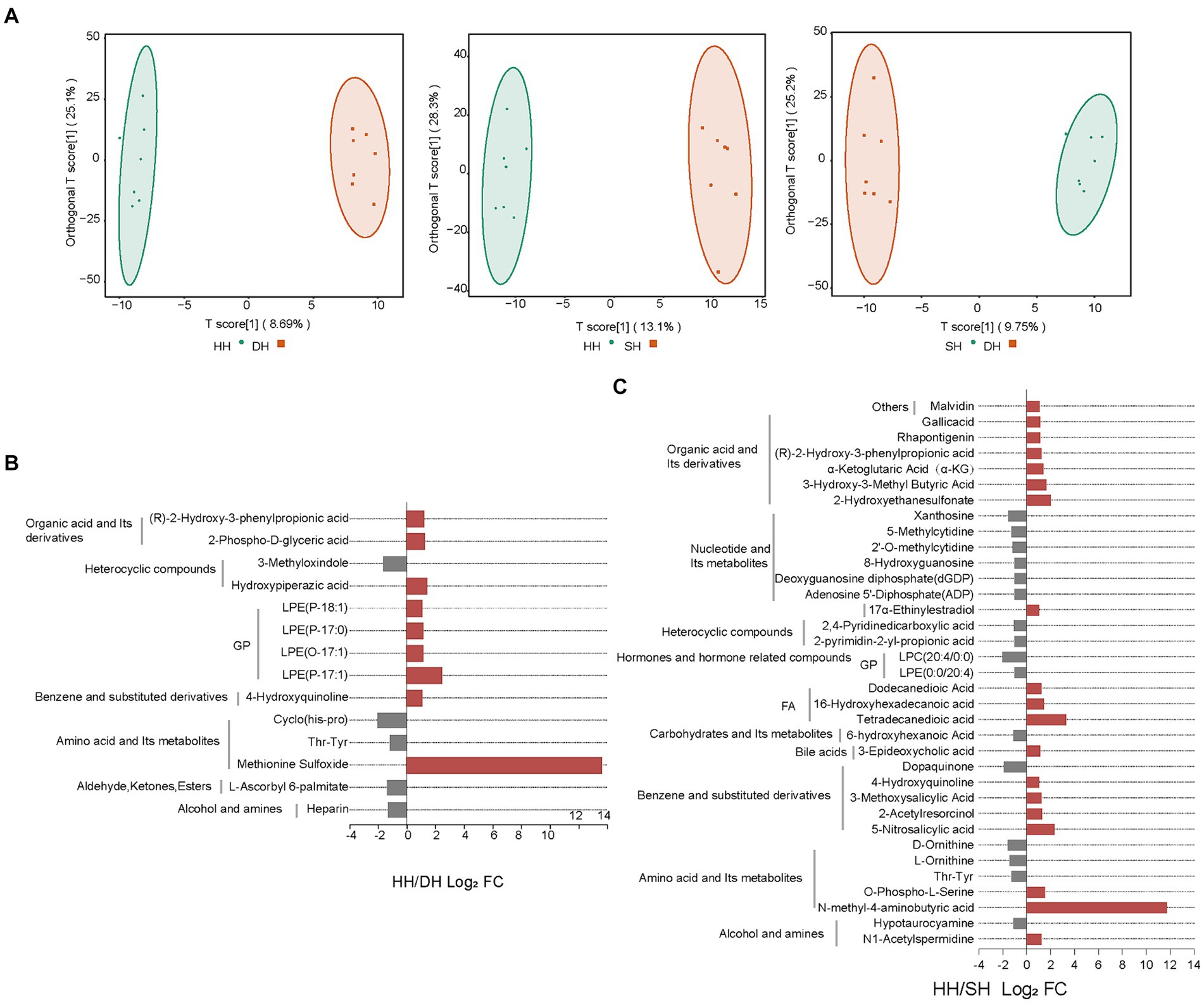

In total, 947 metabolites were identified in the 21 rumen samples. The orthogonal projections to latent structures-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) score plots showed good separation of metabolites between the HH and DH (R2X = 0.419, R2Y = 0.994, Q2 = 0.345), HH and SH (R2X = 0.495, R2Y = 0.992, Q2 = 0.580), and DH and SH (R2X = 0.451, R2Y = 0.991, Q2 = 0.315) groups (Figure 7A). After screening the relative concentrations of rumen metabolites by FC (FC ≥ 2 and FC ≤ 0.5) and VIP (VIP ≥ 1), we obtained 14 metabolites significantly differently enriched in the HH and DH groups, including nine upregulated and five downregulated metabolites (Figure 7B). Levels of lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE) (P-18:1), (P-17:0), (O-17:1), (P-17:1), and methionine sulfoxide were significantly increased in the DH group, while thr-tyr, cyclo (his-pro) and heparin was significantly decreased. Interestingly, methionine sulfoxide was only present in the DH group. A total of 35 metabolites were significantly differently enriched between the HH and SH groups, with19 upregulated and 16 downregulated (Figure 7C). Levels of 6 from organic acid and its derivatives, 3 from fatty acyls (FA), and 2 from amino acid and its derivatives were significantly increased in the SH group, while 6 from nucleotides and their metabolites, 2 from heterocyclic compounds, 3 from amino acids and its derivatives were significantly decreased. N-methyl-4-aminobutyric acid was identified only in the SH group. Between the DH and SH groups, 21 metabolites with significant differences were observed, including 3 upregulated and 18 downregulated. Levels of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl butyric acid, 7-ketocholesterol, and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) (14:0/0:0) were significantly increased, while 4 from nucleotides and their metabolites, 10 from glycerophospholipids (GP), 2 from alcohol and amines metabolites were significantly decreased (Supplementary Figure S7).

Figure 7. Change in rumen content metabolite levels. (A) OPLS-DA analysis. (B) Significantly differential metabolites between the HH and DH groups. (C) Significantly differential metabolites between the HH and SH groups. n = 7 individuals/group.

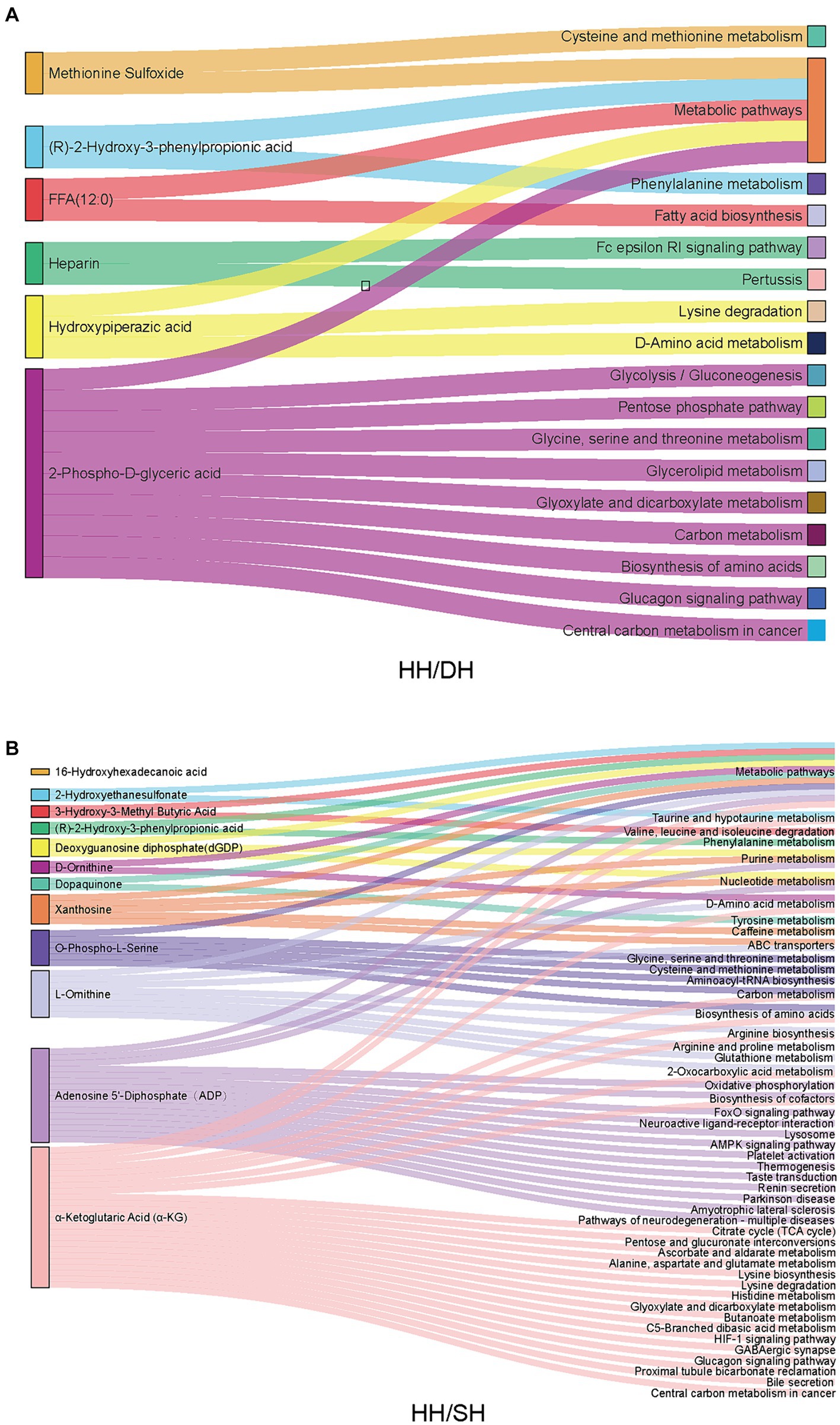

KEGG pathway analysis revealed that of these differential metabolites, six were annotated to 16 pathways between the HH and DH groups (Figure 8A). “Cysteine and methionine metabolism,” “phenylalanine metabolism,” “glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism,” “biosynthesis of amino acids,” “glycolysis/gluconeogenesis,” and “pentose phosphate pathway” were significantly enriched in the DH group, however, “Fc epsilon RI signaling pathway” was enriched in the HH group. Twelve metabolites were annotated in 48 pathways between the HH and SH groups (Figure 8B). Among them, relating to amino acid metabolism, bile acid metabolism and tricarboxylic acid cycle pathways were mainly enriched in the SH group, for example, “phenylalanine metabolism,” “histidine metabolism,” “glycine, serine and threonine metabolism,” “taurine and hypo taurine metabolism,” “bile secretion,” and “citrate cycle (TCA cycle).” The HH group enriched nucleotide metabolism and ABC transporters related to purine metabolism. Seven metabolites were annotated in 12 pathways between the DH and SH groups (Supplementary Figure S8). “Fat digestion and absorption,” “glycerolipid metabolism,” and “vitamin digestion and absorption” were mainly enriched in the DH group, while “valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation” and “choline metabolism in cancer” were mainly enriched in the SH group.

Figure 8. Metabolic pathway enrichment analysis. (A) Between the HH and DH groups. (B) Between the HH and SH groups. n = 7 individuals/group.

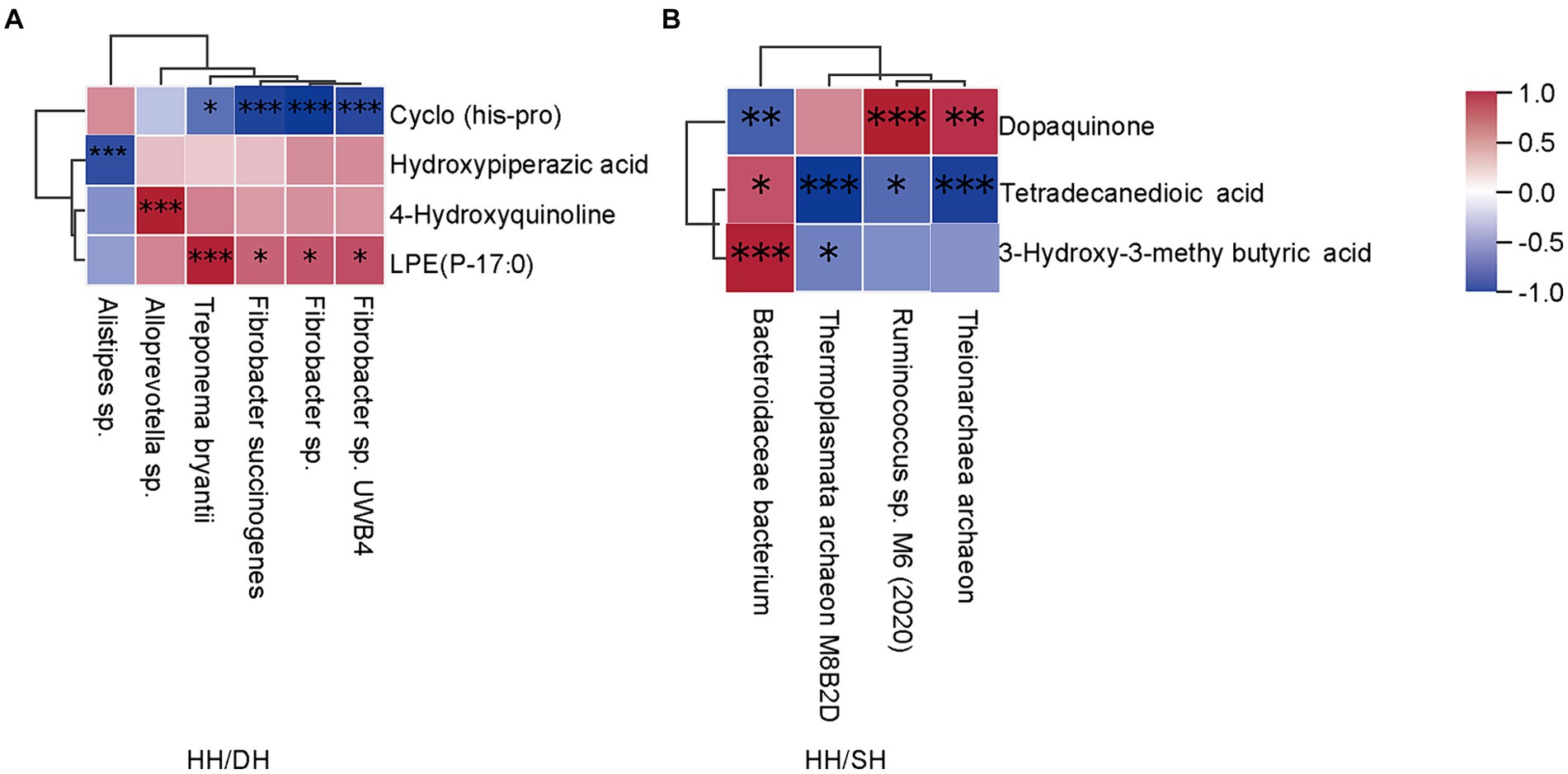

Spearman’s correlation coefficient analysis identified correlations between differential microbiomes and metabolites (|r| > 0.8; p < 0.05). Treponema bryantii, Fibrobacter succinogenes, Fibrobacter sp. UWB4 and Fibrobacter sp. levels were positively correlated with LPE (P-17:0); Alloprevotella sp.was positively correlated with 4-hydroxyquinoline; and Alistipes sp. was negatively correlated with hydroxypiperazic acid when we compared the HH and DH groups (Figure 9A). Bacteroidales bacterium and Ruminococcus sp. M6 (2020) were positively correlated with 3-hydroxy-3-methyl butyric acid and dopaquinone, respectively; whereas Theionarchaea archaeon and Thermoplasmata archaeon M8B2D were negatively correlated with tetradecanedioic acid in the HH and SH groups (Figure 9B). Candidatus Altiarchaeales archaeon WOR SM1 86-2 was positively correlated with LPE (16:0/0:0), LPE (0:0/16:0), LPE (O-18:2), phosphatidylcholine (PC) (O-1:0/O-16:0), lysophosphatidylserine (LPS) (20:0), lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) (22:6); 7-ketocholesterol was positively correlated with Candidatus Methanomethylophilaceae archaeon, Candidatus Methanomethylophilus sp., and Bacteroidales bacterium between the DH and SH groups (Supplementary Figure S8).

Figure 9. Correlation analysis between microbiome and metabolite profiles in rumen samples. (|r| > 0.8). (A) Between the HH and DH groups. (B) Between the HH and SH groups. n = 7 individuals/group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

From the perspective of genetics and breeding, introducing a favorable exogenous gene may be a better choice for improving the low to moderate heritability of traits (28). In this study, we screened Poll Dorset and Southdown sheep as sires to improve the growth performance of Hu sheep, focusing on how hybridization affects growth performance and investigating the regulation mechanism of the rumen microbiome and its metabolites.

Hybridization results in heterosis and improves animal growth. As expected, our data showed that hybridization increased DMI and ADG, resulting in higher FBW and lower F/G. Our previous study indicated that F1 hybrid offspring grew faster and became larger than did Hu sheep, particularly during the later periods (29). Another study on a three-way cross system between Angus, Qaidam, and yak indicated that the F2 offsprings were all significantly better than those of the yak and 1/2 yak (28). These results suggest the importance of hybridization for improving growth performance of animals.

Rumen microecology is closely associated with animal growth. In this study, hybridization significantly changed the rumen fermentation pattern in sheep, especially the NH3-N concentration. NH3-N is mainly derived from microbe-mediated amino acid deamination and non-protein nitrogen hydrolysis in the rumen (30). The rumen microbiome utilizes NH3-N to provide primary protein synthesis precursors for the host. NH3-N also has a feedback effect on rumen microbiota structure and epithelial function, affecting rumen fermentation and host health (31). The NH3-N concentration was significantly lower in the SH and DH groups than in the HH group, indicating that the hybrid offspring had a higher utilization efficiency of nitrogen sources to synthesize bacterial proteins. VFAs are the main energy source for ruminants, which ferment plant materials into VFAs that regulate a variety of physiological functions in the rumen (32). Acetate, propionate, and butyrate are the three major VFAs and provide approximately 70% of energy requirements. Acetate concentration is mainly affected by the microbial degradation of fibrous substances. Reports have shown that rumen acetate concentration increases when ruminants are fed a high-fiber diet (33) or when the rumen microbiota is dominated by Prevotella (34). Of the acetate in the rumen, 67% is used for oxidative energy, while the rest is used for body fat synthesis. Propionate contributes to energy supplementation via the gluconeogenic pathway to promote glucose synthesis (35). In this study, acetate and propionate levels in the DH group significantly increased, resulting in higher total VFAs, indicating a higher energy supply to the host and improved growth performance.

The rumen epithelium is an important indicator of rumen development and is responsible for the absorption and metabolism of nutrients and microbial byproducts. Evidence has shown that VFAs are absorbed through the rumen epithelium and that their absorption capacity is mainly related to the surface area and expression of VFA transporter vectors in the epithelium (36). The rumen epithelium is abundant in mitochondria, powering epithelial metabolism; a thicker epithelium indicates more efficient feed utilization in cattle (37). Additionally, butyrate stimulates epithelial cellular proliferation (38). Our results indicate that hybridization increased papilla height, while no change was observed in papilla width or muscle thickness, which suggests an increased nutrient contact surface area to completely crush the feed to promote digestion and feed efficiency (39). Moreover, these variations in rumen epithelial physical structures are considered to potentially influence the rumen microbiota.

Using PCoA, the present study found significant differences in the rumen microbiome between the F1 hybrid offspring and Hu sheep. Hybridization can produce new gene flow and different gene expression patterns in offspring. Sika and elk deer have different rumen microbiota than do their hybrid offspring; pure and hybrid mice have different microbial clustering characteristics suggesting a significant effect of host genetics on the rumen microbiome that may result from vertical transmission (40–42). Moreover, we found that Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes were the dominant bacteria at the phylum level, however, hybridization had no considerable effect on their relative abundances. Evidence has shown that Bacteroidetes have low heritability estimates, while Firmicutes have moderate heritability estimates, suggesting that they are largely affected by environmental factors, such as diet (15, 43). Concurrently, the different heritability estimates indicate that host effects are not equal for different rumen microbial phylotypes. At the species level, we observed that bacteria related to fiber degradation were more abundant in the DH group, Treponema bryantii, Prevotella copri, and Fibrobacter succinogenes were particularly abundant. Treponema bryantii, when present with cellulolytic species such as Bacteroides succinogenes, can promote the digestion of cellulosic materials to increase feed efficiency (44). A higher abundance of Treponema bryantii and Bacteroides sp. were found in the cecum of pigs with high feed efficiency (45). Prevotella are considered the most important bacteria for polysaccharide degradation and fermentation based on their genomic glycoside hydrolase profiles, gene expression, and abundance in the rumen (46). Prevotella copri might be the keystone bacterial species associated with host feed intake and fat metabolism, and evidence shows that its abundance increases in pigs with high average daily feed intake (47) and promotes fat accumulation in pigs fed formula diets (48). Studies in humans indicate that Prevotella copri largely increases the microbial potential for branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis (49), which is beneficial for milk protein yield in dairy cattle and animal growth (50, 51). Moreover, Prevotella copri is heritable (h2 > 0.15) in the cecum and feces of pigs (52). Fibrobacter succinogenes is regarded as the most highly cellulolytic bacterium in ruminal microbiomes and specializes in the production of succinate, acetate, and formate (53). An increase in the Fibrobacter succinogenes population in the rumen is attributed to an increase in dry matter degradability (54). In the present study, the relative abundances of Fibrobacter sp. UWR2 and Fibrobacter sp. were positively linked to DMI, suggesting their essential roles in DMI and dry matter degradability. In the SH group, the abundance of the Bacteroidaceae bacterium was higher than that of the HH group. Bacteroidaceae bacterium is also a rumen cellulolytic bacterium that can convert succinate to propionate as the sole energy source (55). Therefore, the higher abundance of polysaccharide-degrading bacteria in the rumen of hybrid sheep enhances the degradation of dietary carbohydrates, thus promoting digestive ability and growth performance. This may be attributed to host genetics because we excluded the effects of environmental factors. However, this speculation needs to be verified by monitoring the rumen microbiota of Poll Dorset and Southdown sheep. The DH group lacked archaea related to nutrient digestion and absorption, however, the abundance of methanogenic bacteria (Methanomicrobium sp., Methanolobus bombayensis, and Methanococcus voltae) increased in the SH group compared to levels in the HH group, and methane production is an energy-intensive process, resulting in low production performance. However, in this study, the abundance of these methanogenic bacteria was quite low. We also found that DMI and feed protein utilization efficiency in the SH group were higher than those in the HH group, which suggests that the contributions of DMI and feed protein utilization efficiency surpassed the methane production rate, which may be the reason for the FBW gain in the SH group. Moreover, Xue et al. found that some methanogenic bacteria with low abundance were enriched in the rumens of dairy cows with high milk protein yields (50); however, further studies are needed to validate our hypotheses.

KEGG functional taxonomic analysis revealed that amino acid biosynthesis and metabolism were enriched in the SH group. Metabolic products such as lysine, aspartate, glycine, alanine, glutamate, serine, and threonine are important contributors to rumen microbial protein synthesis, constituting 90% of the microbial proteins that arrive in the small intestine and provide a protein source for the host (56). Our previous study identified that the muscle protein content was higher in the SH group than in the HH group (29), which is in line with the results of the rumen microbiota. Genes encoding CAZymes involved in deconstructing carbohydrates (GHs, CEs, PLs, and CBMs) were enriched in the DH group, indicating that these sheep were more capable of degrading complex substrates to promote microbial fermentation, which is consistent with our VFA results.

In addition to affecting the composition and function of the rumen microbiome, hybridization alters rumen metabolites and metabolic pathways. First, LPEs are cell membrane components and are the second most abundant in vivo after LPCs (57, 58). LPEs reportedly induce the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling and exhibit anti-apoptotic effects in pheochromocytoma cells (59). LPE (P-18:1) has oleic acid as its acyl chain, stimulating neurite outgrowth and neuroprotective effects against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity (60). Additionally, LPEs are involved in lipid droplet formation by suppressing lipolysis and fatty acid biosynthesis, thereby promoting the absorption of lipid substances (61). This evidence indicates that LPEs enriched in the DH group benefited from fat deposition, resulting in FBW gain. Interestingly, methionine sulfoxide was only present in the DH group. The exposure of proteins to reactive oxygen species and hydrogen peroxide may lead to the oxidation of free methionine and methionine residues, forming methionine sulfoxide (62). Methionine sulfoxide levels are elevated during oxidative stress, aging, and inflammation. The results of this study imply that the sheep in the DH group had poor environmental adaptability. However, methionine sulfoxide can be diastereoselectively repaired by methionine sulfoxide reductase to produce methionine (63). Methionine augments the endogenous antioxidant capacity of rice proteins by stimulating methionine sulfoxide reductase expression and enhancing glutathione synthesis via the Nrf2-ARE pathway (64). The beneficial effects of methionine supplementation on the antioxidant activity of heat-stressed birds have been previously demonstrated (65). The present study shows that although sheep in the DH group were in a state of oxidative stress, this phenomenon can be improved by regulating the methionine sulfoxide reductase system, which will be our next research direction. N-methyl-4-aminobutyric acid was only present in the SH group. The metabolic product aminobutyric acid acts as a key inhibitory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system and functions via sedation, relieving fever and decreasing heat production (66). Aminobutyric acid reduces stress caused by various environmental conditions and improves productivity (67). For example, aminobutyric acid improves growth performance, meat quality, and feed intake by promoting the activation of characteristic enzymes and improving the absorption and immune function of the intestinal mucosa under heat-stress conditions (68, 69). The characteristic metabolites in both the DH and SH groups were related to oxidative stress, indicating that the environmental adaptability of the F1 generation sheep needs improvement, which we expect to occur in the F2 generation. α-Ketoglutaric acid is an intermediate metabolite of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and is generated from glucose and glutamine, providing substrates for the synthesis of carbohydrates, amino acids, fats, and other biomolecules (70). In this study, α-ketoglutarate was significantly increased in the SH group compared to levels in the HH group, further enhancing amino acid metabolism ability. Our results were consistent with a previous report by Kong (71), who confirmed the tricarboxylic acid cycle pathways were enhanced in the muscle of Southdown × Hu F1 generation sheep.

Four metabolites and six microbiomes showed regulatory relationships in growth performance between the DH and HH groups. Alloprevotella sp. can ferment carbohydrates to produce acetate and succinate as end-metabolites and is positively correlated with 4-hydroxyquinoline, which has antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects that maintain rumen health (72). Treponema bryantii, Fibrobacter succinogenes, Fibrobacter sp., and Fibrobacter sp.UWB4 are associated with fiber degradation and production of propionate, which are positively correlated with LPE (P-17:0). Propionate can promote glucose synthesis via the gluconeogenic pathway in the rumen, and glucose is a precursor for the form of glycerol and fatty acids, which further help format LPEs. LPEs originate in part from the lipids in the diet, but also from gut microbial synthesis. Phospholipid levels in the host cells of germ-free mice differ from those in the host cells of conventional mice, suggesting a relationship between gut microbes and glycerophospholipids (73). The relative abundance of Faecalibacterium and Prevotella is related to circulating lipids, particularly LEPs and phosphatidylglycerol (74); however, we found in the present study that Fibrobacter was also related to the levels of LPE (P-17:0). Bacteroidales bacterium was positively correlated with 3-hydroxy-3-methyl butyric acid between the SH and HH groups. 3-Hydroxy-3-methyl butyric acid is a leucine metabolite that stimulates the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor-1 axis (75). These results indicate that the rumen microbiota of sheep in the DH group were mainly involved in body fat deposition by increasing DMI and dry matter degradability, whereas that in the SH group mainly participated in amino acid metabolism to provide energy. However, the causal relationship between the microbiota and metabolites requires further research. In addition, the rumen microbiomes and metabolites data of Poll Dorset and Southdown sheep should be considered and further elucidated in future studies.

The results of this study support the feasibility of using crossbreeding programs to promote growth and increase feed efficiency by altering the rumen microbiota and metabolites in sheep. In the DH group, Treponema bryantii, Prevotella copri, and Fibrobacter succinogenes levels increased, and their functions were mainly enriched at the CAZyme level, contributing to higher acetate, propionate, total VFA, and LPE levels to further promote growth. Bacteroidaceae bacterium was enriched in the SH group and is involved in amino acid metabolism, fulfilling the demand for ruminal microbial proteins that are utilized by hosts to promote growth. Additionally, methionine sulfoxide and N-methyl-4-aminobutyric acid were characteristic metabolites in the DH and SH groups, respectively, indicating that the F1 generation crossbred sheep had poor environmental adaptability. Taken together, these findings provide new ideas and nutritional strategies for the cultivation of new sheep breeds.

The data presented in the study are deposited in the SRA repository, accession number PRJNA1111660.

The animal study was approved by Animal Administration and Ethics Committee of the Lanzhou Institute of Husbandry and Pharmaceutical Science of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

RZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. XA: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JL: Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. CN: Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. ZG: Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. TX: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BY: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. ZX: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YY: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Major Scientific Research Task of the Science and Technology Innovation Project of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ZDRW202106), the Central Public interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (1610322023014, 1610322024020), and the Science and Technology Program of Gansu Province (22ZD6NA037, 21ZD11NM001).

We are grateful to the Qinghuan Mutton Sheep Breeding Company for their work including the care and feeding of animals.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2024.1455029/full#supplementary-material

1. Bunning, H, Wall, E, Chagunda, M, Banos, G, and Simm, G. Heterosis in cattle crossbreeding schemes in tropical regions: meta-analysis of effects of breed combination, trait type, and climate on level of heterosis. J Anim Sci. (2019) 97:29–34. doi: 10.1093/jas/sky406

2. Liu, A, Chen, X, Liu, M, Zhang, L, Ma, X, and Tian, S. Differential expression and functional analysis of CircRNA in the ovaries of low and high fecundity Hanper sheep. Animals (Basel). (2021) 11:71863. doi: 10.3390/ani11071863

3. Yang, Y, Shen, L, Gao, H, Ran, J, Li, X, Jiang, H, et al. Comparison of cecal microbiota composition in hybrid pigs from two separate three-way crosses. Anim Biosci. (2021) 34:1202–9. doi: 10.5713/ab.20.0681

4. Christensen, OF, Legarra, A, Lund, MS, and Su, G. Genetic evaluation for three-way crossbreeding. Genet Sel Evol. (2015) 47:98. doi: 10.1186/s12711-015-0177-6

5. Quan, K, Li, J, Han, H, Wei, H, Zhao, J, Si, HA, et al. Review of Huang-Huai sheep, a new multiparous mutton sheep breed first identified in China. Trop Anim Health Prod. (2020) 53:35. doi: 10.1007/s11250-020-02453-w

6. Lu, Z, Yue, Y, Shi, H, Zhang, J, Liu, T, Liu, J, et al. Effects of sheep sires on muscle fiber characteristics, fatty acid composition and volatile flavor compounds in F1 crossbred lambs. Food Secur. (2022) 11:4076. doi: 10.3390/foods11244076

7. Zhao, L, Zhang, D, Li, X, Zhang, Y, Zhao, Y, Xu, D, et al. Comparative proteomics reveals genetic mechanisms of body weight in Hu sheep and Dorper sheep. J Proteome. (2022) 267:104699. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2022.104699

8. Quan, F, Zhang, Z, An, Z, Hua, S, Zhao, X, and Zhang, Y. Multiple factors affecting superovulation in poll Dorset in China. Reprod Domest Anim. (2011) 46:39–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2009.01551.x

9. Hall, SJG . Conserving and developing minority British breeds of sheep: the example of the Southdown. J Agric Sci. (1989) 112:39–45. doi: 10.1017/S0021859600084082

10. Dai, R, Zhou, H, Fang, Q, Zhou, P, Yang, Y, et al. Variation in ovine DGAT1 and its association with carcass muscle traits in Southdown sheep. Genes (Basel). (2022) 13:13. doi: 10.3390/genes13091670

11. Cheng, J, Zhang, X, Xu, D, Zhang, D, Zhang, Y, Song, Q, et al. Relationship between rumen microbial differences and traits among Hu sheep, Tan sheep, and Dorper sheep. J Anim Sci. (2022) 100:100. doi: 10.1093/jas/skac261

12. Firkins, JL, and Yu, Z. Ruminant nutrition symposium: how to use data on the rumen microbiome to improve our understanding of ruminant nutrition. J Anim Sci. (2015) 93:1450–70. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-8754

13. Li, F, Hitch, T, Chen, Y, Creevey, CJ, and Guan, LL. Comparative metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analyses reveal the breed effect on the rumen microbiome and its associations with feed efficiency in beef cattle. Microbiome. (2019) 7:6. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0618-5

14. Cersosimo, LM, Bainbridge, ML, Wright, AD, and Kraft, J. Breed and lactation stage alter the rumen protozoal fatty acid profiles and community structures in Primiparous dairy cattle. J Agric Food Chem. (2016) 64:2021–9. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b05310

15. Li, F, Li, C, Chen, Y, Liu, J, Zhang, C, Irving, B, et al. Host genetics influence the rumen microbiota and heritable rumen microbial features associate with feed efficiency in cattle. Microbiome. (2019) 7:92. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0699-1

16. Zhang, R, Wu, J, Lei, Y, Bai, Y, Jia, L, Li, Z, et al. Oregano essential oils promote rumen digestive ability by modulating epithelial development and microbiota composition in beef cattle. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:722557. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.722557

17. Chen, S, Zhou, Y, Chen, Y, and Gu, J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. (2018) 34:i884–90. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560

18. Li, H, and Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. (2009) 25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324

19. Li, D, Liu, CM, Luo, R, Sadakane, K, and Lam, TW. Megahit: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics. (2015) 31:1674–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv033

20. Noguchi, H, Park, J, and Takagi, T. MetaGene: prokaryotic gene finding from environmental genome shotgun sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. (2006) 34:5623–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl723

21. Fu, L, Niu, B, Zhu, Z, Wu, S, and Li, W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. (2012) 28:3150–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565

22. Li, R, Li, Y, Kristiansen, K, and Wang, J. SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics. (2008) 24:713–4. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn025

23. Altschul, SF, Madden, TL, Schaffer, AA, Zhang, J, Zhang, Z, Miller, W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. (1997) 25:3389–402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389

24. Altschul, SF, Gish, W, Miller, W, Myers, EW, and Lipman, DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. (1990) 215:403–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

25. Sun, HZ, Wang, DM, Wang, B, Wang, JK, Liu, HY, Guan, LL, et al. Metabolomics of four biofluids from dairy cows: potential biomarkers for milk production and quality. J Proteome Res. (2015) 14:1287–98. doi: 10.1021/pr501305g

26. De Almeida, R, Do, PR, Porto, C, Dos, SG, Huws, SA, and Pilau, EJ. Exploring the rumen fluid metabolome using liquid chromatography-high-resolution mass spectrometry and molecular networking. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:17971. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36196-4

27. Kanehisa, M, and Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. (2000) 28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27

28. Cao, XK, Cheng, J, Huang, YZ, Wang, XG, Ma, YL, Peng, SJ, et al. Growth performance and meat quality evaluations in three-way cross cattle developed for the Tibetan plateau and their molecular understanding by integrative omics analysis. J Agric Food Chem. (2019) 67:541–50. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b05477

29. Zhang, R, An, X, Li, J, Lu, Z, Niu, C, Xu, Z, et al. Comparative analysis of growth performance, meat productivity, and meat quality in Hu sheep and its hybrids. Acta Pratacul Sin. (2024) 33:186–97. doi: 10.11686/cyxb2023157

30. Schwab, CG, and Broderick, GA. A 100-year review: protein and amino acid nutrition in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. (2017) 100:10094–112. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13320

31. Shen, J, Zheng, W, Xu, Y, and Yu, Z. The inhibition of high ammonia to in vitro rumen fermentation is pH dependent. Front Vet Sci. (2023) 10:163021. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2023.1163021

32. Shen, H, Xu, Z, Shen, Z, and Lu, Z. The regulation of ruminal short-chain fatty acids on the functions of rumen barriers. Front Physiol. (2019) 10:1305. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01305

33. Li, QS, Wang, R, Ma, ZY, Zhang, XM, Jiao, JZ, Zhang, ZG, et al. Dietary selection of metabolically distinct microorganisms drives hydrogen metabolism in ruminants. ISME J. (2022) 16:2535–46. doi: 10.1038/s41396-022-01294-9

34. Wang, D, Tang, G, Wang, Y, Yu, J, Chen, L, Chen, J, et al. Rumen bacterial cluster identification and its influence on rumen metabolites and growth performance of young goats. Anim Nutr. (2023) 15:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2023.05.013

35. De Vadder, F, Kovatcheva-Datchary, P, Zitoun, C, Duchampt, A, Bäckhed, F, and Mithieux, G. Microbiota-produced succinate improves glucose homeostasis via intestinal gluconeogenesis. Cell Metab. (2016) 24:151–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.013

36. Chai, J, Lv, X, Diao, Q, Usdrowski, H, Zhuang, Y, Huang, W, et al. Solid diet manipulates rumen epithelial microbiota and its interactions with host transcriptomic in young ruminants. Environ Microbiol. (2021) 23:6557–68. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15757

37. Lam, S, Munro, JC, Zhou, M, Guan, LL, Schenkel, FS, Steele, MA, et al. Associations of rumen parameters with feed efficiency and sampling routine in beef cattle. Animal. (2018) 12:1442–50. doi: 10.1017/S1751731117002750

38. Zhang, K, Xu, Y, Yang, Y, Guo, M, Zhang, T, Zong, B, et al. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites contribute negatively to hindgut barrier function development at the early weaning goat model. Anim Nutr. (2022) 10:111–23. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2022.04.004

39. Liu, H, Hu, J, Mahfuz, S, and Piao, X. Effects of hydrolysable tannins as zinc oxide substitutes on antioxidant status, immune function, intestinal morphology, and digestive enzyme activities in weaned piglets. Animals. (2020) 10:757. doi: 10.3390/ani10050757

40. Li, Z, Wright, ADG, Si, H, Wang, X, Qian, W, Zhang, Z, et al. Changes in the rumen microbiome and metabolites reveal the effect of host genetics on hybrid crosses. Environ Microbiol Rep. (2016) 8:1016–23. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12482

41. Kreisinger, J, Ížková, D, Vohánka, J, and Piálek, J. Gastrointestinal microbiota of wild and inbred individuals of two house mouse subspecies assessed using high-throughput parallel pyrosequencing. Mol Ecol. (2014) 23:5048. doi: 10.1111/mec.12909

42. Wang, J, Kalyan, S, Steck, N, Turner, LM, Harr, B, Künzel, S, et al. Analysis of intestinal microbiota in hybrid house mice reveals evolutionary divergence in a vertebrate hologenome. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:6440. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7440

43. Goodrich, JK, Davenport, ER, Beaumont, M, Jackson, MA, Knight, R, Ober, C, et al. Genetic determinants of the gut microbiome in UK twins. Cell Host Microbe. (2016) 19:731–43. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.017

44. Kudo, H, Cheng, KJ, and Costerton, JW. Interactions between Treponema bryantii and cellulolytic bacteria in the in vitro degradation of straw cellulose. Can J Microbiol. (1987) 33:244–8. doi: 10.1139/m87-041

45. Quan, J, Wu, Z, Ye, Y, Peng, L, Wu, J, Ruan, D, et al. Metagenomic characterization of intestinal regions in pigs with contrasting feed efficiency. Front Microbiol. (2020) 11:32. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00032

46. Shinkai, T, Ikeyama, N, Kumagai, M, Ohmori, H, Sakamoto, M, Ohkuma, M, et al. Prevotella lacticifex sp. Nov., isolated from the rumen of cows. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. (2022) 72:5278. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.005278

47. Yang, H, Yang, M, Fang, S, Huang, X, He, M, Ke, S, et al. Evaluating the profound effect of gut microbiome on host appetite in pigs. BMC Microbiol. (2018) 18:215. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1364-8

48. Chen, C, Fang, S, Wei, H, He, M, Fu, H, Xiong, X, et al. Prevotella copri increases fat accumulation in pigs fed with formula diets. Microbiome. (2021) 9:175–5. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01110-0

49. Pedersen, HK, Gudmundsdottir, V, Nielsen, HB, Hyotylainen, T, Nielsen, T, Jensen, BAH, et al. Human gut microbes impact host serum metabolome and insulin sensitivity. Nature (London). (2016) 535:376–81. doi: 10.1038/nature18646

50. Xue, MY, Sun, HZ, Wu, XH, Liu, JX, and Guan, LL. Multi-omics reveals that the rumen microbiome and its metabolome together with the host metabolome contribute to individualized dairy cow performance. Microbiome. (2020) 8:64. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00819-8

51. Pezeshki, A . The role of gut microbiota on regulation of growth and metabolism by branched-chain amino acids. J Anim Sci. (2024) 102:199. doi: 10.1093/jas/skae102.222

52. Chen, C, Huang, X, Fang, S, Yang, H, He, M, Zhao, Y, et al. Contribution of host genetics to the variation of microbial composition of cecum lumen and feces in pigs. Front Microbiol. (2018) 9:2626. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02626

53. Suen, G, Weimer, PJ, Stevenson, DM, Aylward, FO, Boyum, J, Deneke, J, et al. The complete genome sequence of Fibrobacter succinogenes S85 reveals a cellulolytic and metabolic specialist. PLoS One. (2011) 6:e18814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018814

54. Astuti, WD, Ridwan, R, Fidriyanto, R, Rohmatussolihat, R, Sari, NF, Sarwono, KA, et al. Changes in rumen fermentation and bacterial profiles after administering Lactiplantibacillus plantarum as a probiotic. Vet World. (2022) 15:1969–74. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2022.1969-1974

55. Van Gylswyk, NO . Succiniclasticum ruminis gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a ruminal bacterium converting succinate to propionate as the sole energy-yielding mechanism. Int J Syst Bacteriol. (1995) 45:297–300. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-2-297

56. Li, Z, Shi, J, Lei, Y, Wu, J, Zhang, R, Zhang, X, et al. Castration alters the cecal microbiota and inhibits growth in Holstein cattle. J Anim Sci. (2022) 100:100. doi: 10.1093/jas/skac367

57. Koistinen, KM, Suoniemi, M, Simolin, H, and Ekroos, K. Quantitative lysophospholipidomics in human plasma and skin by LC–MS/MS. Anal Bioanal Chem. (2015) 407:5091–9. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8453-9

58. Ukanović, N, Obradović, S, Zdravković, M, Urašević, S, Stojković, M, Tosti, T, et al. Lipids and antiplatelet therapy: important considerations and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:3180. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063180

59. Inoue, N, Sakurai, T, Yamamoto, Y, Chiba, H, and Hui, SP. Profiling of lysophosphatidylethanolamine molecular species in human serum and in silico prediction of the binding site on albumin. Biofactors. (2022) 48:1076–88. doi: 10.1002/biof.1868

60. Hisano, K, Yoshida, H, Kawase, S, Mimura, T, Haniu, H, Tsukahara, T, et al. Abundant oleoyl-lysophosphatidylethanolamine in brain stimulates neurite outgrowth and protects against glutamate toxicity in cultured cortical neurons. J Biochem. (2021) 170:327–36. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvab046

61. Yamamoto, Y, Sakurai, T, Chen, Z, Inoue, N, Chiba, H, and Hui, S. Lysophosphatidylethanolamine affects lipid accumulation and metabolism in a human liver-derived cell line. Nutrients. (2022) 14:579. doi: 10.3390/nu14030579

62. Moskovitz, J, and Smith, A. Methionine sulfoxide and the methionine sulfoxide reductase system as modulators of signal transduction pathways: a review. Amino Acids. (2021) 53:1011–20. doi: 10.1007/s00726-021-03020-9

63. Sharov, VS, and Schoneich, C. Diastereoselective protein methionine oxidation by reactive oxygen species and diastereoselective repair by methionine sulfoxide reductase. Free Radic Biol Med. (2000) 29:986–94. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00400-7

64. Li, H, Cai, L, Liang, M, Wang, Z, Zhang, Y, Wu, Q, et al. Methionine augments endogenous antioxidant capacity of rice protein through stimulating MSR antioxidant system and activating Nrf2-are pathway in growing and adult rats. Eur Food Res Technol. (2020) 246:1051–63. doi: 10.1007/s00217-020-03464-5

65. De Freitas, DA, de Souza, KA, Alcalde, CR, Gasparino, E, and Feihrmann, AC. Supplementation with free methionine or methionine dipeptide improves meat quality in broilers exposed to heat stress. J Food Sci Technol. (2021) 58:205–15. doi: 10.1007/s13197-020-04530-2

66. Hu, H, Bai, X, Shah, AA, Wen, AY, Hua, JL, Che, CY, et al. Dietary supplementation with glutamine and γ-aminobutyric acid improves growth performance and serum parameters in 22- to 35-day-old broilers exposed to hot environment. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. (2016) 100:361–70. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12346

67. Park, K, Oh, M, Joo, Y, and Han, J. Effects of gamma aminobutyric acid on performance, blood cell of broiler subjected to multi-stress environments. Anim Biosci. (2023) 36:248–55. doi: 10.5713/ab.22.0031

68. Dai, SF, Gao, F, Zhang, WH, Song, SX, Xu, XL, and Zhou, GH. Effects of dietary glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid on performance, carcass characteristics and serum parameters in broilers under circular heat stress. Anim Feed Sci Technol. (2011) 168:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2011.03.005

69. Chen, Z, Xie, J, Wang, B, and Tang, J. Effect of gamma-aminobutyric acid on digestive enzymes, absorption function, and immune function of intestinal mucosa in heat-stressed chicken. Poult Sci. (2014) 93:2490–500. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03398

70. Inigo, M, Deja, SA, and Burgess, SC. Ins and outs of the TCA cycle: the central role of anaplerosis. Annu Rev Nutr. (2021) 41:19–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-120420-025558

71. Kong, L, Yue, Y, Li, J, Yang, B, Chen, B, Liu, J, et al. Transcriptomics and metabolomics reveal improved performance of Hu sheep on hybridization with Southdown sheep. Food Res Int. (2023) 173:113240. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.113240

72. Oien, NL, Brideau, RJ, Hopkins, TA, Wieber, JL, Knechtel, ML, Shelly, JA, et al. Broad-spectrum antiherpes activities of 4-Hydroxyquinoline carboxamides, a novel class of herpesvirus polymerase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2002) 46:724–30. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.724-730.2002

73. Schoeler, M, and Caesar, R. Dietary lipids, gut microbiota and lipid metabolism. Rev Endocr Metab Dis. (2019) 20:461–72. doi: 10.1007/s11154-019-09512-0

74. Brown, EM, Clardy, J, and Xavier, RJ. Gut microbiome lipid metabolism and its impact on host physiology. Cell Host Microbe. (2023) 31:173–86. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2023.01.009

Keywords: hybridization, rumen, metagenome, growth performance, sheep

Citation: Zhang R, Zhang L, An X, Li J, Niu C, Zhang J, Geng Z, Xu T, Yang B, Xu Z and Yue Y (2024) Hybridization promotes growth performance by altering rumen microbiota and metabolites in sheep. Front. Vet. Sci. 11:1455029. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1455029

Received: 26 June 2024; Accepted: 26 August 2024;

Published: 25 September 2024.

Edited by:

Qingbiao Xu, Huazhong Agricultural University, ChinaReviewed by:

Kaizhen Liu, Henan Agricultural University, ChinaCopyright © 2024 Zhang, Zhang, An, Li, Niu, Zhang, Geng, Xu, Yang, Xu and Yue. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhenfei Xu, MjM2eHV6aGVuZmVpQDE2My5jb20=; Yaojing Yue, eXVleWFvamluZ0BjYWFzLmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.