- 1Department of Public Health and Laboratory Medicine, Yiyang Medical College, Yiyang, China

- 2School of Basic Medical Sciences, Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, China

Introduction: Wild rodents are key hosts for Cryptosporidium transmission, yet there is a dearth of information regarding their infection status in the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region and Liaoning Province of China. Therefore, the present study was conducted to determine the prevalence and genetic characteristics of Cryptosporidium among wild rodents residing in these two provinces.

Methods: A total of 486 rodents were captured, and fresh feces were collected from each rodent’s intestine for DNA extraction. Species identification of rodents was performed through PCR amplification of the vertebrate cytochrome b (cytb) gene. To detect the presence of Cryptosporidium in all fecal samples, PCR analysis and sequencing of the partial small subunit of the ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene were performed.

Results: Four species of rodents were identified: Rattus norvegicus, Mus musculus, Apodemus agrarius, and Cricetulus barabensis. Positive results for Cryptosporidium were obtained for 9.2% (18/195), 6.6% (7/106), 5.6% (5/89), and 6.3% (6/96) of these rodents, respectively, with an average infection rate of 7.4% (36/486). The identification revealed the presence of five Cryptosporidium species, C. ubiquitum (n = 8), C. occultus (n = 5), C. muris (n = 2), C. viatorum (n = 1), and C. ratti (n = 1), along with two Cryptosporidium genotypes: Rat genotype III (n = 10) and Rat genotype IV (n = 9).

Discussion: Based on the molecular evidence presented, the wild rodents investigated were concurrently infected with zoonotic (C. muris, C. occultus, C. ubiquitum and C. viatorum) as well as rodent-adapted (C. ratti and Rat genotype III and IV) species/genotypes, actively participating in the transmission of cryptosporidiosis.

1 Introduction

Cryptosporidium, a parasitic apicomplexan organism, infiltrates the epithelial cells of the small intestine, leading to infections that are the second most prevalent cause of severe diarrhea among young children residing in regions with limited resources (1). Additionally, Cryptosporidium is a significant opportunistic pathogen among immunocompromised individuals, such as those living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), transplant recipients, cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, and those undergoing hemodialysis treatment (2). Moreover, water-borne and food-borne outbreaks of Cryptosporidium are common among the general population. Globally, more than 1,200 outbreaks have been attributed to the transmission of Cryptosporidium through waterborne sources (3). Additionally, over 8 million cases of cryptosporidiosis were reported annually due to foodborne outbreaks (4). Therefore, cryptosporidiosis holds immense significance in public health, necessitating proactive measures to prevent and control its occurrence.

By using genotyping technology, over 170 species and genotypes of Cryptosporidium have been identified, existing across a diverse range of hosts (5). Human cryptosporidiosis is primarily attributed to either the anthroponotic C. hominis or zoonotic C. parvum. Additionally, humans can become infected with another 20 species/genotypes of Cryptosporidium (6). Although these infections occur at a lower frequency, recently, there has been a noticeable increase in reports of human infections caused by species other than C. hominis and C. parvum, such as C. meleagridis, C. ubiquitum, C. cuniculus, C. andersoni and C. viatorum (5, 6). These species of Cryptosporidium possess the ability to infect a diverse array of animals, and the majority of human infections caused by them may occur through animals, either via direct contact or ingestion of feces-contaminated oocysts in water or food (6). To effectively contain the transmission of Cryptosporidium, it is crucial to embrace a “One Health” approach that recognizes the intricate interdependence between humans, animals, and the environment (7). Rodents, which are widely distributed globally with a vast array of activities, maintain close ties to humans, animals, and the environment. Consequently, they exert significant influence on their ecosphere, particularly due to their ability to transmit Cryptosporidium oocysts into the environment, thereby affecting both humans and animals (8).

Extensive research has been conducted on rodents infected with Cryptosporidium, revealing an average prevalence of 19.8% when molecular detection methods are employed (8). Molecular confirmation has identified more than 26 species and 59 genotypes of Cryptosporidium across more than 54 rodent species (5, 8). Although most species and genotypes are host-specific or exhibit a limited host range, virtually all known Cryptosporidium species and genotypes capable of infecting humans have been detected in rodents (5, 8). Consequently, rodents pose a significant public health risk as reservoirs of zoonotic Cryptosporidium species. To effectively evaluate the prevalence of Cryptosporidium in rodents and support the development of policies aimed at preventing its transmission to humans and other animals, continuous monitoring of Cryptosporidium in rodents, particularly wild rats, is imperative, especially in regions where no sampling conducted before.

In China, the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region and Liaoning Province are mainly dependent on agriculture and animal husbandry as their economic sources. Rodents are widely distributed in these regions and are active on farms and livestock farms. However, currently, the prevalence of Cryptosporidium in rodents, especially wild ones, in these two provinces is still unclear. Therefore, this study aimed to conduct a molecular diagnosis of Cryptosporidium in wild rodents in the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region and Liaoning Province of China, determine Cryptosporidium infection rates and evaluate the risk of zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium at the species level.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Ethical concerns

The protocols used in the present study underwent a meticulous review process and were ultimately approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Wenzhou Medical University (approval number SCILLSC-2021-01).

2.2 Sample collection

Between November 2023 and February 2024, a cumulative total of 486 wild rodents were collected, with 229 rodents originating from Harqin Banner in Inner Mongolia and 257 rodents originating from Jianping County in Liaoning Province, China (Figure 1 and Table 1). Rodents were captured by utilizing cage traps baited with a mixture of peanut and sunflower seeds. For each designated capture location, approximately 50 cage traps were methodically placed in a straight line, ensuring a uniform spacing of 5 meters between each trap and effectively establishing transects. At 4:00 PM, the transects were positioned and retrieved the following morning at 8:00 AM. Each rodent captured was euthanized humanely via CO2 asphyxiation and promptly transported to the laboratory within 48 h, ensuring its safety in sealed containers containing ice. A fecal sample weighing 0.5 grams was collected from the rectum of each rodent.

Figure 1. Map of the wild rodent sampling location in the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region and Liaoning Province, China.

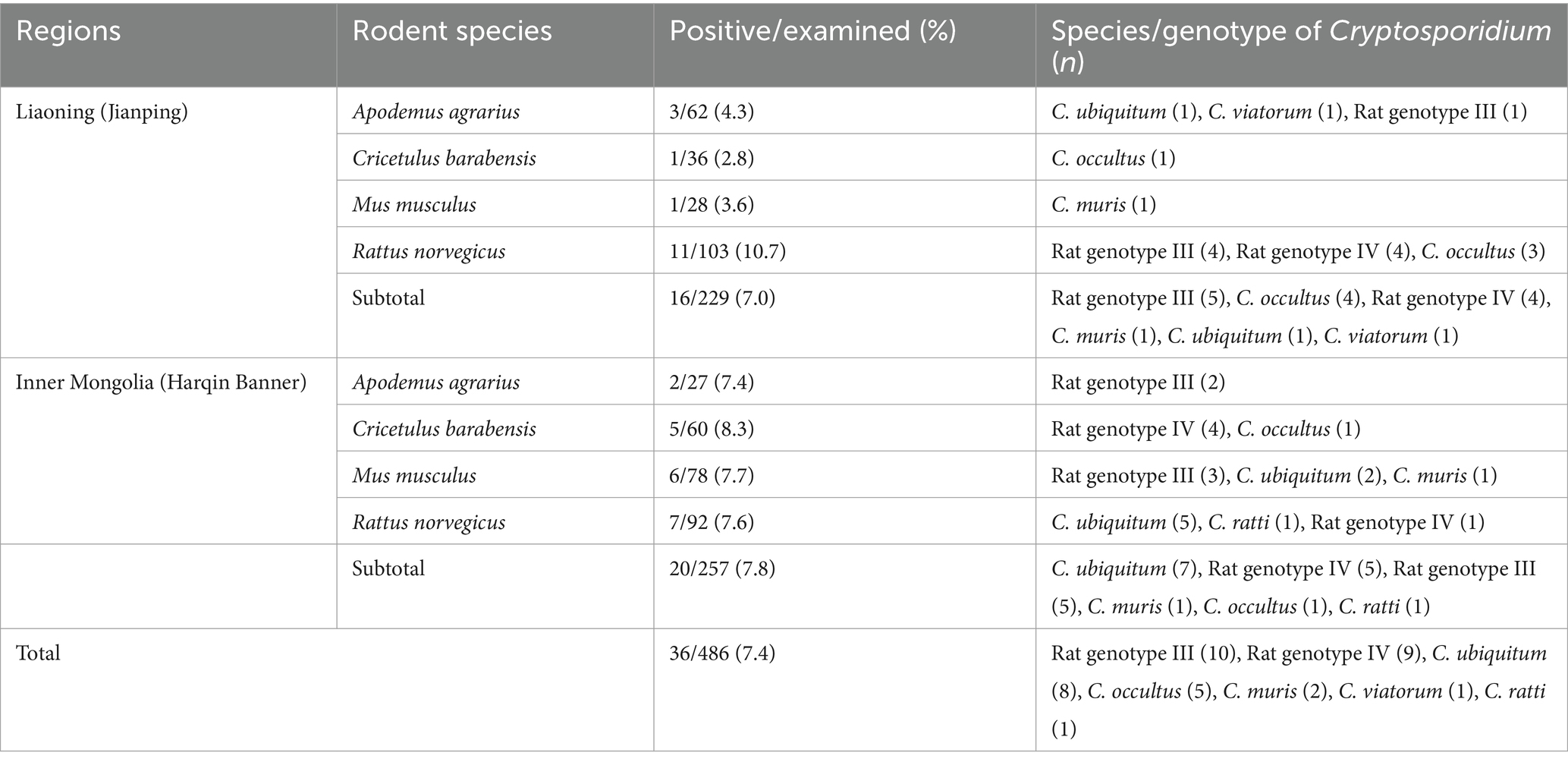

Table 1. Prevalence and distribution of Cryptosporidium species/genotypes in the investigated rodents from the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region and Liaoning Province of China.

2.3 DNA extraction

Exclusively designated for DNA extraction, 0.2 grams of each fecal sample was processed, while the remaining portion was preserved as a backup and stored at a chilled temperature of −80°C. Using the QIAamp DNA Mini Stool Kit (Qiagen, Germany), genomic DNA was extracted from each processed sample. During the extraction process, the lysis temperature was increased to 95°C, while all other steps were performed strictly according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Subsequently, the DNA was reconstituted in 200 μL of AE elution buffer, provided with the kit, and was subsequently stored at −20°C prior to PCR analysis.

2.4 Identification of rodent species

To identify the rodent species, the vertebrate cytochrome b (cytb) gene (421 bp) was amplified via PCR from the fecal DNA. The primer sequences were 5’-TACCATGAGGACAAATATCATTCTG-3′ and 5’-CCTCCTAGTTTGTTAGGGATTGATCG-3′, and PCR conditions were as follows: 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 51°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. Initial denaturation was performed at 94°C for 5 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. These conditions followed the previously described protocol by Verma and Singh (10).

2.5 Cryptosporidium genotyping

All DNA samples were subjected to nested PCR utilizing primers previously developed by Xiao et al. in 1999 to amplify an 830 bp fragment of the partial small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene of Cryptosporidium (9). The primers used for the primary PCR were 5’-TTCTAGAGCTAATACATGCG-3′ and 5’-CCCTAATCCTTCGAAACAGGA-3′, while the primers used for the secondary PCR were 5′-GGAAGGGTTGTATTTATTAGATAAAG-3′ and 5’-AAGGAGTAAGGAACAACCTCCA-3′. Both PCR amplification steps were conducted under identical conditions, commencing with initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min. This was followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, annealing at 55°C for 45 s, extension at 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. TaKaRa Taq DNA Polymerase was used for PCR amplification, with positive controls using DNA from chickens infected with C. baileyi and negative controls using deionized water without DNA templates. PCR products were analyzed via gel electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel in TAE buffer, with GelRed (Biotium Inc., Fremont, California, United States) serving as the staining agent.

2.6 Sequencing analysis

The PCR products of the expected size were purified using a DNA gel purification kit from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). These purified products were then sequenced using the Sanger sequencing method by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., on an ABI Prism 3,730 XL DNA analyzer. Sequencing was performed with the same primers used for the secondary PCR and was facilitated by a BigDyeTerminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, United States). To guarantee the precision of the nucleotide sequence, sequencing was carried out from both ends of the product, and further PCR products were sequenced whenever mutations were identified. After acquiring the sequences, they were carefully edited using DNASTAR Lasergene version 7.1.0 and aligned with reference sequences retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) using the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) and ClustalX 2.0 software (http://www.clustal.org/) to accurately identify the Cryptosporidium species.

2.7 Phylogenetic analyses

The SSU rRNA sequences of Cryptosporidium spp. obtained in this study were combined with reference sequences to construct a phylogenetic tree using Mega 7.0 software. The Tamura–Nei model-based Maximum Likelihood method was chosen to analyze the phylogenetic relationships. To ensure the reliability of the evolutionary tree, a bootstrap analysis was conducted with 1,000 replicates. The reference sequences necessary for tree construction were retrieved from GenBank and previous research studies.

2.8 Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed utilizing SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., United States). The chi-square test was utilized to determine the disparities in the occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. across diverse regions and rodent species. A p value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

2.9 Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The nucleotide sequences of Cryptosporidium obtained in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers PP527771 to PP527783.

3 Results

3.1 Rat species identification

In this study, PCR and sequencing analysis of the cytb gene revealed the presence of four rodent species: Apodemus agrarius (n = 89), Cricetulus barabensis (n = 96), Mus musculus (n = 106) and Rattus norvegicus (n = 195). No additional data were gathered for these wild rodents (Table 1).

3.2 Prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection

Nested PCR was performed on 486 fecal samples to assess the presence of Cryptosporidium species by analyzing the SSU rRNA gene. The results revealed that 36 samples were positive for this parasite, yielding an average infection rate of 7.4%, with 7.0% (16/229) in Liaoning (Jianping) and 7.8% (20/257) in Inner Mongolia (Harqin Banner) (Table 1). Statistical analysis did not indicate any significant differences in Cryptosporidium prevalence between the two regions (χ2 = 0.11, df = 1, p = 0.74). Regarding rodent species variation, the highest infection rate of Cryptosporidium was observed for R. norvegicus (9.2%; 18/195), followed by M. musculus (6.6%; 7/106), A. agrarius (5.6%; 5/89), and C. barabensis (6.3%; 6/96). The difference in the infection rate of Cryptosporidium among the rodent species groups was not statistically significant (χ2 = 1.65, df = 3, p = 0.65).

3.3 Distribution of Cryptosporidium species/genotypes

Five species of Cryptosporidium, namely, C. ubiquitum (n = 8), C. occultus (n = 5), C. muris (n = 2), C. viatorum (n = 1), and C. ratti (n = 1), as well as two genotypes—Cryptosporidium Rat genotype III (n = 10) and Cryptosporidium Rat genotype IV (n = 9)—have been identified through sequencing the PCR products of 36 Cryptosporidium-positive samples (Table 1).

In Liaoning, Cryptosporidium Rat genotype III emerged as the dominant species, accounted for 31.3% (5/16) of the positive samples, followed by C. occultus and Cryptosporidium Rat genotype IV each comprising 25.0% (4/16). The remaining three species, C. muris, C. ubiquitum, and C. viatorum, contributed equally with a share of 3.3% (1/16) each. On the other hand, in Inner Mongolia, C. ubiquitum emerged as the predominant species, accounting for 35.0% (7/20) of the positive samples. Cryptosporidium Rat genotype III and Cryptosporidium Rat genotype IV followed closely, each comprising 25.0% (5/20) of the positive samples. The remaining species, C. muris, C. occultus, and C. ratti, contributed 5.0% (1/20) each (Table 1).

Among the different rodent species, R. norvegicus carried a diverse range of species/genotypes of Cryptosporidium, including C. ubiquitum, C. ratti, C. occultus, Cryptosporidium Rat genotype III and Cryptosporidium Rat genotype IV. In contrast, C. barabensis was limited to carrying only C. occultus and Cryptosporidium Rat genotype IV. The remaining two rodent species each harbored three species/genotypes: C. ubiquitum, C. viatorum and Cryptosporidium Rat genotype III in A. agrarius and C. ubiquitum, C. muris and Cryptosporidium Rat genotype III in M. musculus (Table 1).

3.4 Genetic identification of Cryptosporidium species/genotypes

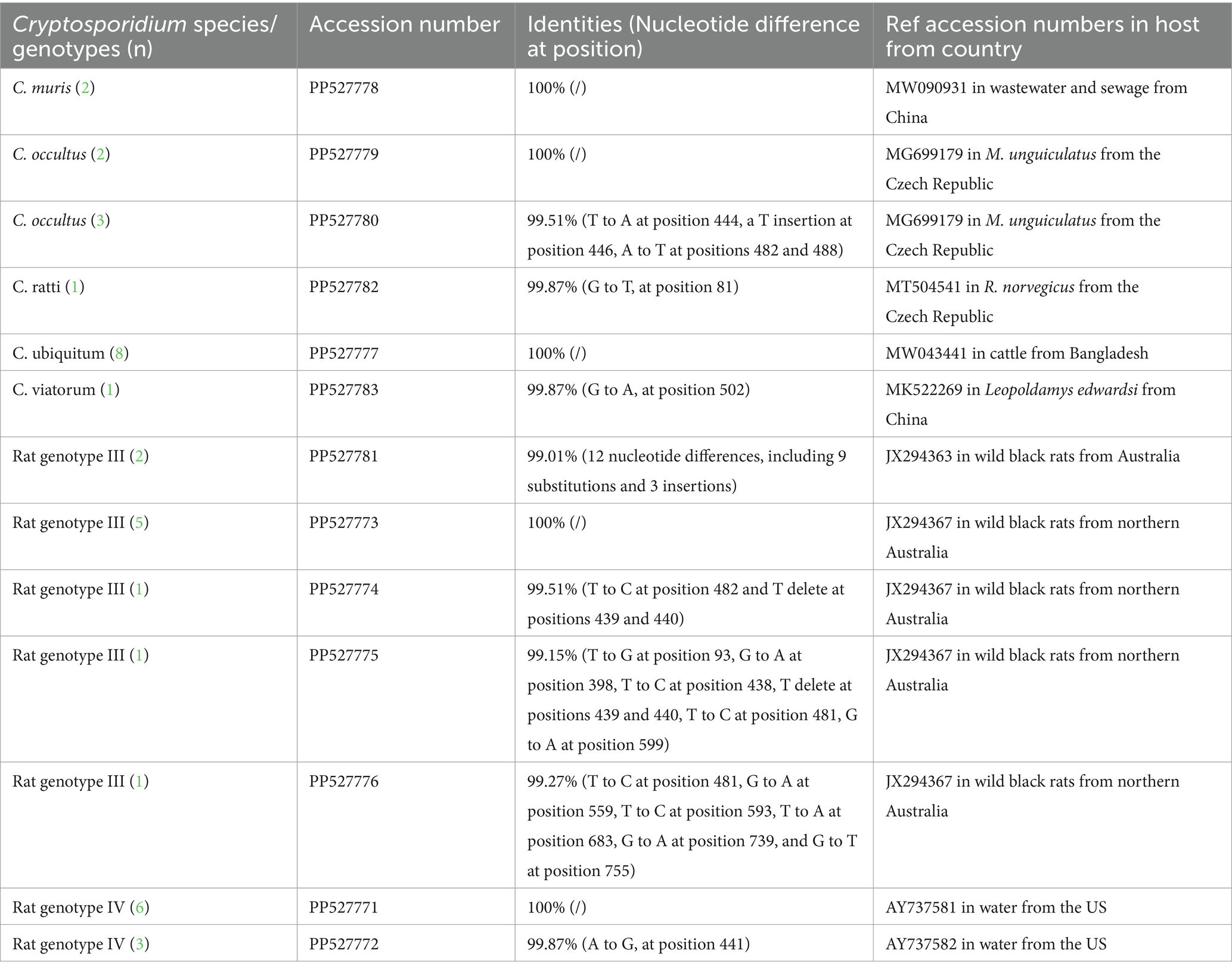

Among the nine SSU rRNA sequences belonging to Cryptosporidium Rat genotype IV, six sequences were found to be identical to each other, sharing perfect 100% similarity with the Cryptosporidium genotype W19 variant sequence (AY737581) previously isolated from water samples in the United States (US). The three remaining sequences of Cryptosporidium rat genotype IV were identical to each other and had not been previously described. They exhibited a remarkable similarity of 99.87% to the Cryptosporidium genotype W19 variant sequence (AY737582), which was also detected in US waters. The sole difference among them was a single nucleotide substitution, specifically from A to G, at position 441 (Table 2).

Table 2. Sequence similarity analysis of Cryptosporidium species/genotypes in this study with reference sequences from GenBank.

Ten SSU rRNA sequences of Cryptosporidium Rat genotype III revealed five types, with one type represented in five samples sharing an identical sequence (JX294367) with Cryptosporidium Rat genotype III from wild black rats in northern Australia. The second type represented two samples were novel, exhibiting 99.01% similarity (12 nucleotide differences, including 9 substitutions and 3 insertions) with JX294363, which was found in wild black rats from Australia. The remaining three types were each found in a single sample and were previously undescribed, differing from the Cryptosporidium Rat genotype III sequence (JX294367) of wild black rats from northern Australia by three (T to C at position 482 and T delete at positions 439 and 440), seven (T to G at position 93, G to A at position 398, T to C at position 438, T delete at positions 439 and 440, T to C at position 481, G to A at position 599), and six (T to C at position 481, G to A at position 559, T to C at position 593, T to A at position 683, G to A at position 739, and G to T at position 755) nucleotides (Table 2).

The present study identified eight sequences of C. ubiquitum that were consistent with each other and exhibited 100% similarity to the C. ubiquitum sequence (MW043441) isolated from cattle in Bangladesh. The two C. muris sequences were also identical and exhibited 100% similarity with MW090931, which was isolated from wastewater and sewage in Guangzhou, China (Table 2).

Among the five sequences of C. occultus obtained in this study, two exhibited 100% homology with MG699179, which was identified in Meriones unguiculatus from the Czech Republic. The remaining three sequences of C. occultus were homologous to each other and were novel, sharing 99.51% similarity with MG699179, differing by four nucleotides (Table 2).

The sequences of C. ratti and C. viatorum identified here were novel and differed by one nucleotide from MT504541 in R. norvegicus in the Czech Republic and from MK522269, which was found in Leopoldamys edwardsi from China (Table 2).

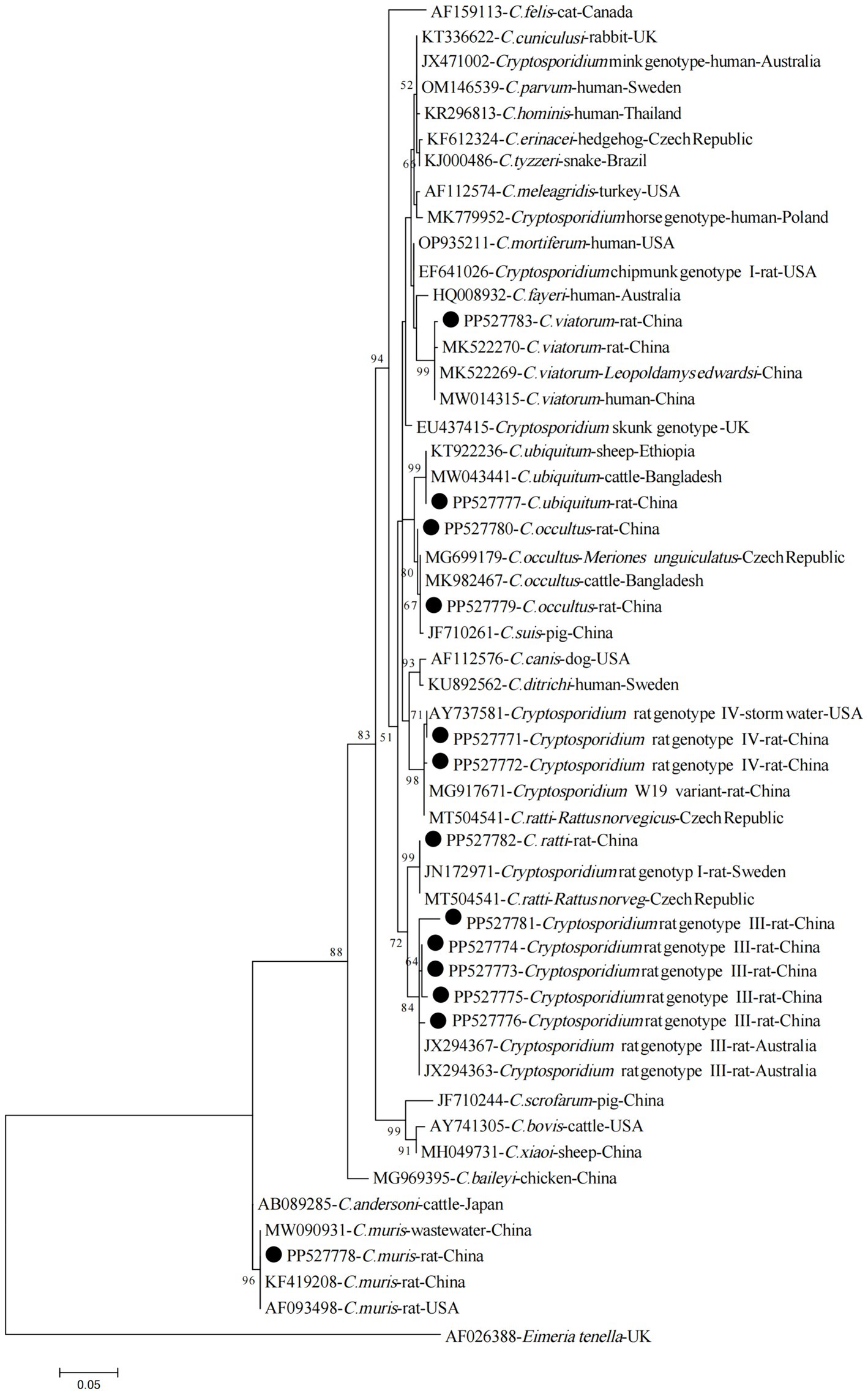

The phylogenetic analysis of the ssu rRNA sequences has confirmed that the sequences obtained in the present study, corresponding to C. viatorum, C. ubiquitum, C. occultus, Cryptosporidium Rat genotype IV, C. ratti, Cryptosporidium Rat genotype III, and C. muris, have clustered together with their respective reference sequences, forming distinct and clearly identifiable groups within the phylogenetic tree (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree of Cryptosporidium species based on partial SSU rRNA gene sequences (~800 bp). The tree was generated using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Tamura-Nei model. Bootstrap values (> 50%) derived from 1,000 replicates are displayed to the left of the nodes for reliability assessment. The sequences generated in the present study are indicated with solid circles.

4 Discussion

Cryptosporidium infections among rodents have been reported in 19 countries, with global prevalence rates ranging from 0.7 to 100%. The overall average infection rate for rodents is 19.8%, indicating a widespread distribution of this parasite in rodent populations worldwide (8, 11). The present study revealed an average positive rate of 7.4% (36/486) for Cryptosporidium among the surveyed wild rodents. Explaining the disparities in prevalence rates among studies is challenging due to the numerous influencing factors. Although the four wild rodent species (R. norvegicus, M. musculus, A. agrarius, and C. barabensis) investigated in this study did not show significant differences in infection rates, rodent species may still have an impact on Cryptosporidium infection rates. For instance, Zhang et al. recently summarized the occurrences of Cryptosporidium infections across 54 rodent species, encompassing wild, domestic pet, farm, and laboratory animals. Specifically, the prevalence rates among these rodent categories are as follows: 20.5% for wild animals, 27.0% for domestic pets, 14.5% for farm animals, and 2.7% for laboratory animals (8). Additionally, geographical location is another crucial factor, with overall infection rates varying across Asia, Europe, South America, North America, and Africa at 18.6, 28.0, 15.2, 7.3, and 2.2%, respectively (11). However, it is worth noting that these rates could be influenced by the limited number of studies conducted in each region. Specifically, Africa, South America, and North America have only one or two studies, thus limiting their representativeness (8, 11). Therefore, to gain a comprehensive understanding of the epidemiology of Cryptosporidium in rodents, it is imperative to conduct broader geographical surveys that encompass a more diverse range of species and individuals.

The present study identified five species and two genotypes of Cryptosporidium among the surveyed wild rodents. Among these, C. ratti and Cryptosporidium Rat genotypes III, and IV are predominantly found in rodents, exhibiting a narrow host range that is typically rodent-specific (5). Although sporadically reported in other animals, such as camels, goats, black bears and cats, these species and genotypes have not been documented in humans and are rarely encountered in other hosts, rendering their potential pathogenicity uncertain (5, 12–15). Nevertheless, their ability to be detected in streams in the US and in raw sewage water in various countries underscores the need for further investigations to delineate their actual host range and assess their impact on public health (16–19).

Cryptosporidium muris, a dominant parasite in rodents, has been identified in more than 20 rodent species as well as in pigs, pigeons, camels, black-boned goats, sheep, horses, and captive zoo animals (5, 6). Multiple reports exist of C. muris infections in humans, primarily in low-income countries and HIV+ patients, with limited reports in high-income nations (20). Although our study identified C. muris in only two specimens of Mus musculus, this finding not only confirms that Mus musculus is the primary host of C. muris but also suggests that C. muris infection may serve as a significant link in disease transmission to humans and other animals. Additionally, C. occultus primarily infects rats and has also been reported in ruminants such as cattle, water buffaloes, yaks, deer, alpacas and bactrian camels (5, 21). Limited human cases have also been reported (22). This study is the first to identify C. occultus in R. norvegicus and C. barabensis, further expanding its host range and indicating that these two rodent species play active roles in the transmission of this parasite.

Cryptosporidium ubiquitum and C. viatorum are two commonly encountered zoonotic species that infect humans (6). Among these, C. ubiquitum often occurs in rodent species, encompassing 21 distinct genotypes, exhibiting an exceptional capacity to infect a diverse array of hosts, such as primates, carnivores, and ruminants (5, 23). In the present study, C. ubiquitum was identified in R. norvegicus, A. agrarius, and M. musculus, with a preponderance in R. norvegicus from Inner Mongolia. This observation might suggest the potential for cross-species transmission of C. ubiquitum between rodents and goats/sheep, considering its widespread detection in these animals in Inner Mongolia (24). Although no human cases of C. ubiquitum infection have been documented in this region thus far, the known pathogenicity of this species toward humans cannot be discounted, given its numerous reported cases in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom (23). Therefore, individuals, particularly those residing in Inner Mongolia, should exercise caution and refrain from contact with brown rats and other wild rodents to mitigate the risk of cryptosporidiosis transmission from rodent sources. Moreover, it has been confirmed here that A. agrarius has been infected with C. viatorum, which initially identified in humans in 2012 (25). Cases of C. viatorum infection have been documented in 13 countries, including China (22). Currently, C. viatorum has only been described in rodent species such as R. rattus, R. lutreolus, Leopoldamys edwardsi, and Berylms bowersi (26–28). These findings suggest that rodents serve as the primary hosts for this parasite, further emphasizing their crucial role in its transmission.

5 Conclusion

This study revealed a 7.4% infection rate of wild rodents with Cryptosporidium spp. in the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region and Liaoning Province, China. Molecular analysis revealed the presence of nonhuman infectious C. ratti, Cryptosporidium rat genotypes III and IV, and zoonotic species such as C. ubiquitum, C. occultus, C. muris, and C. viatorum. These findings indicate that rodents may play a crucial role in maintaining and disseminating these infections, posing a potential risk to public health. Therefore, a comprehensive multidisciplinary “One Health” approach is imperative to gain a thorough understanding of rodent-related Cryptosporidium and potential transmission routes.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by the protocols of the present study underwent a rigorous review process and were ultimately approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Wenzhou Medical University, with the approval number SCILLSC-2021-01. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

LL: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Q-X: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Resources. AJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology. FZ: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. WZ: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Resources. FT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation Committee (2023JJ50363) and the Basic Scientific Research Project of Wenzhou (Y2023070).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. GBD Diarrhoeal Diseases Collaborators . Estimates of global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and eaetiologies of diarrhoeal diseases: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. (2017) 17:909–48. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30276-1

2. Pumipuntu, N, and Piratae, S. Cryptosporidiosis: a zoonotic disease concern. Vet World. (2018) 11:681–6. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2018.681-686

3. Bourli, P, Eslahi, AV, Tzoraki, O, and Karanis, P. Waterborne transmission of protozoan parasites: a review of worldwide outbreaks - an update 2017-2022. J Water Health. (2023) 21:1421–47. doi: 10.2166/wh.2023.094

4. Ryan, U, Hijjawi, N, and Xiao, L. Foodborne cryptosporidiosis. Int J Parasitol. (2018) 48:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2017.09.004

5. Egan, S, Barbosa, AD, Feng, Y, Xiao, L, and Ryan, U. Critters and contamination: zoonotic protozoans in urban rodents and water quality. Water Res. (2024) 251:121165. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2024.121165

6. Ryan, U, Zahedi, A, Feng, Y, and Xiao, L. An update on zoonotic Cryptosporidium species and genotypes in humans. Animals. (2021) 11:3307. doi: 10.3390/ani11113307

7. Innes, EA, Chalmers, RM, Wells, B, and Pawlowic, MC. A one health approach to tackle cryptosporidiosis. Trends Parasitol. (2020) 36:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2019.12.016

8. Zhang, K, Fu, Y, Li, J, and Zhang, L. Public health and ecological significance of rodents in Cryptosporidium infections. One Health. (2021) 14:100364. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100364

9. Xiao, L, Escalante, L, Yang, C, Sulaiman, I, Escalante, AA, Montali, RJ, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Cryptosporidium parasites based on the small-subunit rRNA gene locus. Appl Environ Microbiol. (1999) 65:1578–83. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.4.1578-1583.1999

10. Verma, SK, and Singh, L. Novel universal primers establish identity of an enormous number of animal species for forensic application. Mol Ecol. (2003) 3:28–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-8286.2003.00340.x

11. Hancke, D, and Suárez, OV. A review of the diversity of Cryptosporidium in Rattus norvegicus, R. Rattus and Mus musculus: what we know and challenges for the future. Acta Trop. (2022) 226:106244. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2021.106244

12. El-Alfy, ES, Abu-Elwafa, S, Abbas, I, Al-Araby, M, Al-Kappany, Y, Umeda, K, et al. Molecular screening approach to identify protozoan and trichostrongylid parasites infecting one-humped camels (Camelus dromedarius). Acta Trop. (2019) 197:105060. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.105060

13. Koinari, M, Lymbery, AJ, and Ryan, UM. Cryptosporidium species in sheep and goats from Papua New Guinea. Exp Parasitol. (2014) 141:134–7. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2014.03.021

14. Li, J, Dan, X, Zhu, K, Li, N, Guo, Y, Zheng, Z, et al. Genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis in dogs and cats in Guangdong, China. Parasit Vectors. (2019) 12:571. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3822-z

15. Wang, SN, Sun, Y, Zhou, HH, Lu, G, Qi, M, Liu, WS, et al. Prevalence and genotypic identification of Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in captive Asiatic black bears (Ursus thibetanus) in Heilongjiang and Fujian provinces of China. BMC Vet Res. (2020) 16:84. doi: 10.1186/s12917-020-02292-9

16. Dela Peña, LBRO, Vejano, MRA, and Rivera, WL. Molecular surveillance of Cryptosporidium spp. for microbial source tracking of fecal contamination in Laguna Lake, Philippines. J Water Health. (2021) 19:534–44. doi: 10.2166/wh.2021.059

17. Fan, Y, Wang, X, Yang, R, Zhao, W, Li, N, Guo, Y, et al. Molecular characterization of the waterborne pathogens Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Cyclospora cayetanensis and Eimeria spp. in wastewater and sewage in Guangzhou, China. Parasit Vectors. (2021) 14:66. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-04566-5

18. Chalmers, RM, Robinson, G, Elwin, K, Hadfield, SJ, Thomas, E, Watkins, J, et al. Detection of Cryptosporidium species and sources of contamination with Cryptosporidium hominis during a waterborne outbreak in north West Wales. J Water Health. (2010) 8:311–25. doi: 10.2166/wh.2009.185

19. Zahedi, A, Gofton, AW, Greay, T, Monis, P, Oskam, C, Ball, A, et al. Profiling the diversity of Cryptosporidium species and genotypes in wastewater treatment plants in Australia using next generation sequencing. Sci Total Environ. (2018) 644:635–48. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.024

20. Chappell, CL, Okhuysen, PC, Langer-Curry, RC, Lupo, PJ, Widmer, G, and Tzipori, S. Cryptosporidium muris: infectivity and illness in healthy adult volunteers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2015) 92:50–5. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0525

21. Kváč, M, Vlnatá, G, Ježková, J, Horčičková, M, Konečný, R, Hlásková, L, et al. Cryptosporidium occultus sp. n. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in rats. Eur J Protistol. (2018) 63:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2018.02.001

22. Xu, N, Liu, H, Jiang, Y, Yin, J, Yuan, Z, Shen, Y, et al. First report of Cryptosporidium viatorum and Cryptosporidium occultus in humans in China, and of the unique novel C. Viatorum subtype XVaA3h. BMC Infect Dis. (2020) 20:16. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4693-9

23. Li, N, Xiao, L, Alderisio, K, Elwin, K, Cebelinski, E, Chalmers, R, et al. Subtyping Cryptosporidium ubiquitum, a zoonotic pathogen emerging in humans. Emerg Infect Dis. (2014) 20:217–24. doi: 10.3201/eid2002.121797

24. Lang, J, Han, H, Dong, H, Qin, Z, Fu, Y, Qin, H, et al. Molecular characterization and prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. in sheep and goats in western Inner Mongolia, China. Parasitol Res. (2023) 122:537–45. doi: 10.1007/s00436-022-07756-5

25. Elwin, K, Hadfield, SJ, Robinson, G, Crouch, ND, and Chalmers, RM. Cryptosporidium viatorum n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) among travelers returning to Great Britain from the Indian subcontinent, 2007-2011. Int J Parasitol. (2012) 42:675–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.04.016

26. Koehler, AV, Wang, T, Haydon, SR, and Gasser, RB. Cryptosporidium viatorum from the native Australian swamp rat Rattus lutreolus - an emerging zoonotic pathogen? Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. (2018) 7:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2018.01.004

27. Ni, HB, Sun, YZ, Qin, SY, Wang, YC, Zhao, Q, Sun, ZY, et al. Sun HT, Molecular detection of Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi infection in wild rodents from six provinces in China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2021) 11:783508. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.783508

28. Zhao, W, Zhou, H, Huang, Y, Xu, L, Rao, L, Wang, S, et al. Cryptosporidium spp. in wild rats (Rattus spp.) from the Hainan Province, China: molecular detection, species/genotype identification and implications for public health. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. (2019) 9:317–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2019.03.017

Keywords: Cryptosporidium, prevalence, wild rodent, genotyping, public health, China

Citation: Liu L, Xu Q, Jiang A, Zeng F, Zhao W and Tan F (2024) Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium in wild rodents from the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region and Liaoning Province, China: assessing host specificity and the potential for zoonotic transmission. Front. Vet. Sci. 11:1406564. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1406564

Edited by:

Rodrigo Morchón García, University of Salamanca, SpainReviewed by:

Beatriz Cancino-Faure, Universidad Católica del Maule, ChileAlicia Rojas, University of Costa Rica, Costa Rica

Copyright © 2024 Liu, Xu, Jiang, Zeng, Zhao and Tan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Zhao, aGF5aWRhemhhb3dlaUAxNjMuY29t; Feng Tan, dGFuZmVuZ3NvbmdAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Li Liu1†

Li Liu1† Fansheng Zeng

Fansheng Zeng Wei Zhao

Wei Zhao Feng Tan

Feng Tan